Abstract

The rise of visual culture and the role of images in shaping contemporary thought and global society has been a constant since the end of the last century. Called “Iconic turn” in the field of philosophy of perception and image theory, this process has captured increasing attention in diverse academic fields, even in disciplines such as architecture where the role of images has not always been well considered. There is no doubt, however, that the visual nature of architecture makes the image essential in its conception, representation or perception. Within this relationship between architecture and image can be noted a recent change: a progressive attention toward realism as an alternative to an arbitrariness of form whose main consequence has been an uncritical use of images by architects and their consumption by society. The visual nature of some of the most influential works of the British architects Sergison Bates and Tony Fretton are exemplary for this purpose, aware of the importance of images in the shaping of everyday life and in the architectural narratives of the real. These works, in turn, allow us to explore the reciprocal strengthening that this realism as an attitude in being (architecture) and in looking (photography) has for an architectural practice that feeds on images and engenders them.

1. Introduction

Architectural works evoke an associative and emotional response that should not be ignored. Some of them transport us to times and places to which we cannot return, offer us emotionally charged experiences, or trigger memories from different layers of our memory. Sometimes, they even become monuments of the collective memory, or simply signs of a certain cultural value. Architectural works, as with other aesthetic expressions, set off an individual and collective imaginary (Bruno 2002, 2007).

The search for meanings for historical constructions has always prevailed in the approach of Art History to architectural works. Topics such as the visual experience of observers in their encounters with works do not receive the same degree of attention. However, we can appreciate a growing number of studies focusing on what cannot be rationalized, arguing that something in the materiality of works goes beyond the meanings ascribed to them. The re-evaluation of the relationship between the work and the observer is connected to the new materialism in humanities, to phenomenological discourse, and to various academic currents focusing on ways of seeing and on the active role of works in the production of subjectivities.

Renewed attention to the visual, to how artistic works or aesthetic objects capture our attention and, more generally, to the role of images in contemporary society has been called in theoretical terms “Iconic turn” in German academia, or “Pictorial turn” in Anglo-American one. Paying attention to something that cannot be read—that goes beyond a semiotic interpretation—reformulates the approaches that have prioritized the study of verbal language as the basis of knowledge.1 This “turn”, first used by W.J.T. Mitchell, formulates a diagnosis of the state of our culture; an environment of communication and thought increasingly based on images.2

The transition from a “culture of words” to a “culture of images” is due to their interest as sources of knowledge and as representations of our ways of thinking (García Varas 2015). Gottfried Boehm, another exponent of the “Iconic turn”, states that “the ‘image’ is not simply some new topic, but relates much more to a different mode of thinking, one that has shown itself capable of clarifying and availing itself of the long-neglected cognitive possibilities that lie in non-verbal representation”.3 Nicholas Mirzoeff, for his part, has insisted on the predominance of the visual in the configuration of our culture: “human experience is more visual and visualized ever before”. He adds that “the gap between the wealth of visual experience in postmodern culture and the ability to analyze that observation marks both the opportunity and the need for visual culture as a field of study”.4 “Iconic turn”, therefore, re-evaluates the meaning of the visual in contemporary culture.5

Other theorists linked to “Iconic turn” have demanded more attention to the performative status of the work of art or, in other words, to what it does rather than to what it produces: “you cannot read affects, you can only experience them” (O’Sullivan 2006, p. 43). Authors from the phenomenological tradition such as Michael Fried, Hubert Damisch, David Freedberg and Rosalind Krauss give precedence to the active role of visual objects compared to the reconstruction of their production conditions or their interpretation based on established models.

This debate around the “Iconic turn” has not had the same impact on architectural theory and criticism. Furthermore, the idea of image itself still retains negative connotations in certain areas of architectural discourse. This is connected to the widespread idea of thinking of an image as two dimensional and static in contrast to the spatial and temporal nature of architecture. The same could be said of iconic architecture, a notion usually associated with works containing little formal reflection or critical profundity, those based on gimmicky impact, or those conceived as simple analogies from other cultural areas.6 Nevertheless, the visual nature of architecture takes on an active and constitutive role in the very experience of observation. This concept invites us to think of architecture not as a system of symbols or as a language that can be read, but as a visual system that produces an associative and perceptual response.

One of the architects who has recently shown more attention to the visual nature of architecture and the role of images in his work is Peter Zumthor. At times, Zumthor’s architecture seems to propose an iconic logic based on a calm, analytical and experiential gaze. As Zumthor points out: “Memories…are the reservoirs of the architectural atmospheres and images that I explore in my work as an architect” (Zumthor 1999, p. 10).7 In many of his drawings, Zumthor tries to capture the atmosphere and those images that his work then tries to transmit, or in other words, to offer a spatial expression to the images that he has in his mind. We should mention, in this regard, the role of photography (think about the role of Hans Danuser’s photographs in the interpretation of Zumthor’s architecture), as it has promoted a visual construction of architecture based on the interpretation of its iconic logic.8

This article examines the role of images in architectural culture, specifically, in so far as their uses directly influence its conception and dissemination (Bergera 2017). Some works by Sergison Bates and Tony Fretton are examples for this objective, not only because they reflect the special interest of these architects in the role of images, but also because these works allow an analysis using the analytical tools that visual studies offer and that the Iconic turn has highlighted. Another remarkable aspect of these works is that show a conceptual and visual nature related to the experience of everyday life and a sensibility close to realism. After decades of indiscriminate use and abuse of images, a look more interested in the everyday and realism provides renewed interpretations to re-evaluating the visual nature of the built space (Vassallo 2019).

2. Image and Realism in Sergison Bates

“In our view, the experience of everyday life is highly influenced by personal and collective association relating to the images of buildings. By images, we can mean the aspect of an object that relates to appearance and character and which stimulates an architectural and emotional response. While it may be argued that most architectural acts produce images of things, we believe that only few architects consciously work with images”.(Sergison and Bates [1999] 2001, p. 47)

How does architecture capture the temporary appearance and the transitory feelings that constitute the perceptual experience? We can find a fruitful answer to this question—related to the debate on images—in the approach of realism to the everyday; it is based on the handling of the richness of the associations that our perception makes from its encounter with the world. In this respect, the historian James Elkins9 states that we must go beyond the images legitimated by high culture in order to analyze those that favour the analysis of reality. Therefore, in a world influenced by fiction and virtual reality and dominated by the commercialized image (Gadanho 2019), one of the responsibilities of the critical architect could be precisely defending the meaning of the real and the idea of experience in our social and cultural interactions (Vassallo 2016).

In this sense, the evolution of the discourse of film and photography has been essential in the development of realism regarding its focus on the everyday (Certeau 2000). The revision of the iconic, favouring a visual construction of the social sphere based on the real has stimulated a more open look at culture.10 It is worth re-examining the idea of aura by Walter Benjamin in terms of perception, understood as the moment when the collective and personal experience coincide, where an object triggers an involuntary memory in order to establish a specific web of space and time.11 This interpretation is relevant to assess the encounter with the architectural work and stimulate an experience of reality that fosters a more associative and emotional response.

The British architects Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates have followed this path opened by realism and have acknowledged the relevant role that images play in their architectural practice. Their approach to images represents an original look interested not only in the idea of the monument or in the symbolic content of a work, but also in the idea of the architectural moment. The iconic, in this sense, takes on a meaning that differs from that associated with works imbued with a strong visual impact. The research by Sergison Bates is not about the permanence and stability of the work, it is about presentation and transition, by constructing an affinity that is closer to everyday life than to the heroic act (Ursprung 2016, pp. 17–27).

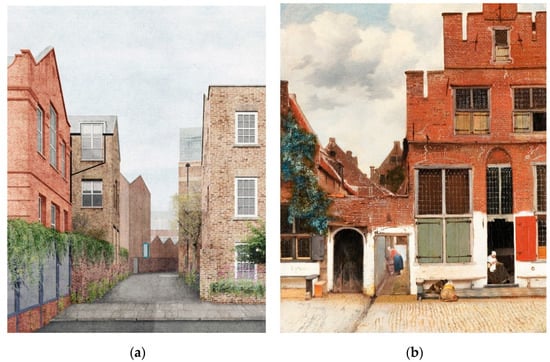

Some of the latest works by Sergison Bates, such as the Arts and Wellbeing Centre (London, 2018) and the Mansion Block (Hampstead, 2017) are related to the former Studio House (Bethnal Green, London, 2004) or End-of-terrace Housing (Hackney, London, 2002) concerning what we could call a “revision of the urban image”. The first project was an extension to the St. Margaret’s House charitable community to develop a new space including a theatre, studios for artists, spaces for social enterprises, start-ups and offices. They proposed grouping the entire programme within a sophisticated organized volume using a large ground-floor hall that opens and is directly connected to an external space that articulates the other buildings of the community and becomes the heart of the ensemble community life.

One of the main focuses of the proposal is the development of this external space for the community, which, as well as connecting the ensemble with the city, expresses the character of the proposal. The definition of this articulating space shows an interest in bordering spaces or transition areas, both linked to a basic concept of realism, namely the revealing of connections between different parts. Some 19th-century realism artists such as Gustave Courbet or Adolph Menzel were especially interested in pictorially representing the functioning and joints between things, as is the case with social realism and documentary photographers. The proposal also highlights other aspects of realism such as the everyday, history, theatricality and the peculiar chromatic spectrum of greyish browns that dominate the ensemble.

The image that Sergison Bates presented also links the proposal with realism and brings to mind the painting by Johannes Vermeer The Little Street, c. 1658 (Figure 1). The visual culture historian Martin Jay states that 17th- and 18th-century painting in the Netherlands should be more strongly connected to the empirical experience of observation and less to the Cartesian look, in other words, to a reproduction of the vision rather than to an expression of prior knowledge.12 In Vermeer’s painting, the point of view is one of many, a specific scene, far removed from a privileged point of view and without any centrality whatsoever. Neither the little street nor the hallway extends to any depth and the image appears to be more a reaction to something that has aroused our interest than the precise organization of a representation space. Sergison Bates’ way of seeing the image not only develops a specific urban concept, but it also triggers a very precise cultural association.

Figure 1.

(a) Arts and Wellbeing Centre, London, Sergison Bates, c. 2018. © Sergison Bates. (b) The Little Street, Johannes Vermeer, 1658. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NL. (Image in the public domain).

This principle of “no centrality” that is reminiscent of painters such as Witte or Saenredam can also be observed in the images developed for the housing project in Hampstead. The way in which the ensemble appears to be present and absent at the same time is striking; it seems to dissolve into the setting and yet it stays in the memory. It contains the common and the exceptional; it raises difficulties in being distinguished from its location while offering an alternative look that makes it possible to see it in a different way. The importance given to transition spaces (patios, stairways, thresholds, etc.) shows, once again, an interest in joints and transitory elements, in everyday life far removed from the heroic act (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mansion Block, Hampstead, Sergison Bates, 2017. © Sergison Bates.

Access to the dwellings is through a sequence of spaces conceived as a sum of scenarios that represent the moment of arriving home. The emphasis on this transition between the public and private sphere can be seen at the moment when the domination of the street ends and the home’s power is yet to begin. The idea of comfort conveyed by homes is related to this sum of layers; protective layers such as the sum of successive thresholds between the street and the dwelling—which are required in order to feel at home. Sometimes, the danger of comfort lies in an excessive isolation that leads to loss of feeling. To deal with this, Sergison Bates adds elements connected to the known in each transition area: “familiar” doors, windows and handles that trigger and heighten our visual associations. The idea of comfort, therefore, is not only based on a warm, safe setting, but also on the reproduction of the known and the familiar; a comfort that is neither purely physical nor totally psychological.

The idea of rooms and their grouping represents a reflection on the image of the domestic. Besides tries to not make evident the organization of the space and connect different spaces through the diverse openings and perspectives that allow fixing the inhabitant gaze and its presence. In this regard, Irina Davidovici describes the interest of Sergison Bates in architecture as a “backdrop to everyday life”; an architecture that implies “something two-dimensional, something against which the act of inhabitation is projected” (Davidovici 2001, p. 48). We can take this idea further and understand that the project has an air of neorealist film in the sense of arranging various scenarios, passages or images in sequence to reflect the acts of everyday life.

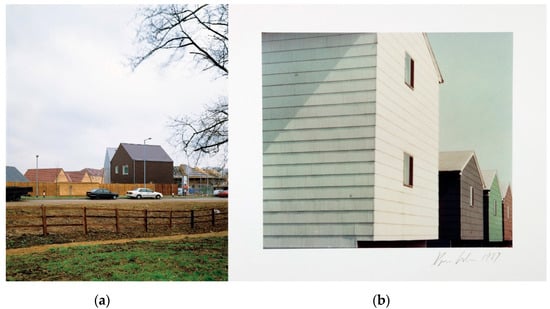

The Prototype for Suburban Housing (Stevenage, 2000) also exemplifies the search for an associative and emotional response closely connected to everyday life. With this model, Sergison Bates put the focus on a marginal phenomenon to return an image to the residential architecture genre. The aim was to leave behind the notion of suburban housing (the image of an isolated house) to construct an association: the image of two joined houses. The image is, therefore, halfway between urban density and urban sprawl; an image that combines in a unique way closeness and distance to the neighbourhood (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Suburban Housing, Stevenage, 2000, Sergison Bates. © Sergison Bates. (b) Homes for America, Dan Graham, 1966. © Dan Graham.

This revision of the image of the British suburb is in tune with the look presented by the American artist Dan Graham in his famous Homes for America. Graham photographed a series of dwellings in the suburbs of New Jersey on different dates emphasizing the sequenced and automated nature of this extensive urban planning (Moure 2009). The influence of realism is obvious, while Graham also shows a clear artistic intent. These images are closely connected to conceptual and minimalist art through the emphasis on sequenced repetitions, simplicity, the use of industrial materials in construction and the precise geometry of the forms. The reference to Sol LeWitt is accentuated in the design of dwellings as a series of cubes, as works that seem to come from one single mould and emphasize one single formal approach.13

The more recent suburban housing in Aldershot (2016) by Sergison Bates also leaves the image of an isolated dwelling behind to assert itself as a group of seven pairs of houses. The ensemble continues the picturesque rural image of the garden city and it is characterized by an internal communal area that articulates all dwellings. Again, the architects show their interest in articulating spaces for community life, linked to the sensibility of realism. The small variations, both in the style and orientation, provide a visual richness and reinforce the picturesque character of the ensemble.

In both projects, the definition of the architectural details revisits the collective suburban imaginary, as is the case with the openings and window frames, the gable roof and its finishes (gutters, drainpipes, etc.). Again, Sergison Bates talks about joints and transition elements, seduced by the communicative nature of social realism photography. The way they used everyday objects also shows an interest in pop art, an interpretation not too far away from what we can find in Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg and Richard Hamilton; a reflection on the visualization of these objects, their everyday appearance, and their nature when they are not subject to the economy of the spectacle. This is about overcoming the dichotomy between images and things, the division of reality and the alienation of ordinary objects.

The critical look of the architects in these projects is close to that shown by the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo in “The End of Modernity”, where he argues in favour of a “weak” or “fragile” architecture or, in our case, an architecture of weak images and structures. In contrast to seduction using a spectacular image and a vigorous articulation of the form, architecture with a weak image is more interested in associative and sensory interaction than in an idealized expression (Vattimo 1987). These works also echo the debate between the concepts of exteriority and interiority arising from the “Iconic turn”. The dialogue between these two aspects allows for a more intimate and emotional condition of the visual, by adding texture and complexity to our understanding of iconicity in architecture.

3. Image and Visual Thinking in Tony Fretton

“When designing I draw on things that already exist, that I have observed and experienced, in which I sense social, political and artistic qualities that will be recognized by other people”.(Fretton 2008, p. 7)

The role of images in the relationship between work and observer is another of the topics discussed in the context of “Iconic turn”. Some theoretical stances, as the notion of image by Henri Bergson in “Matter and Memory”, are of particular interest: “Matter is an aggregate of ‘images’. And by ‘image’ we mean a certain existence which is more than that which the idealist calls a representation, but less than that which the realist calls a thing; an existence placed half-way between the ‘thing’ and the ‘representation’”. Bergson does not reduce the image to a two-dimensional concept or to its function and meaning as a symbol. For him, images interact to take on an active role in our perception. We are always “in the presence of images, in the vaguest sense of the word, images perceived when my senses are opened to them, unperceived when they are closed. All these images act and react upon one another in all their elementary parts according to constant laws” (Bergson [1896] 2016, p. 50).

W.T.J. Mitchell in “What do Pictures Want?” (Mitchell 2006) also considers the active role of images and argues that their lives are only partially controlled by their authors. He opens the door to the interpretation of the time of images—since its condition as active agent (or agency) makes it possible to prolong it beyond their creation—and to the appreciation of the visual for its progressive and changing nature.14 Conceiving the image as an active element in the encounter with the observer, thus rejecting a passive representation, is essential in the evaluation of the image within the context of architecture, given its greater proximity to the formal and iconic logic of works. Therefore, interpretations that address the “effects of presence” (without rejecting the “effects of meaning”) are essential to go beyond representation systems that trade in the attributions of meaning and to achieve a less mediated experience with the works.

The contemporary British architect Tony Fretton has shown great interest in the active role of images in the configuration of visual thinking. In his designs, Fretton examines the relationships between the observer and the architectural work, in a context in which the experience of the known plays an essential role. In this case, the term “relationships” is based on an idea that differs from that of representation; it appeals to the memory and known things or to a collective imaginary of the everyday and what exists in the city, in order to then develop a specific architectural response. This process explains a certain common feeling when experiencing and observing Fretton’s architecture: a mixture of surprise and recognition.

One of his first internationally recognized works was Lisson Gallery (London, 1992). In his appraisal of the project, Fretton states: “The facts and events of London that would be framed in the windows of the galleries presented themselves to me with political, social and existential force, and the building seemed able to construct itself from meaningful fragments of other building to say something of its times. Then a natural relation with the past and a high degree of freedom in defining the present became possible” (Fretton 2008, pp. 141–42). Lisson Gallery was designed as a sum of spaces that show a certain random order aimed at transferring the spontaneous atmosphere of the neighbourhood to the experience of the observer. The windows take on an essential role in the presence of the work by mediating on the relationships between internal spaces, the observer and the city. Some of the relationships prompted by the windows are unexpected, as is the case with the large windows on the façade, which act as diaphragms when we see ourselves reflected in the act of observing the works of art inside. By making available some images to experience new ones through them, they encourage the perception of the city as a palimpsest.

The photography of the façade published in 1992 (Figure 4) is reminiscent of the act of walking along the street on a cold, clear morning. It underlines an aspect that is connected to the relationships that a building establishes with its surroundings and, above all, with the life that is played out both inside and outside and that influences our perception of the work. The photography shows the lower room, below street level, through a window that reflects the objects. As with the space on the upper floor, this is something public, exposed to view. The façade is limited to what is essential: two doors, one for the residence and one for the gallery, and sliding windows that can be opened to introduce larger works. “In essence, the facade is made up of the activities inside and the reflections of the surrounding trees, buildings and sky” (Fretton 2005, p. 20).

Figure 4.

Lisson Gallery, London, 1992, Tony Fretton. © Chris Steele-Perkins. Magnum photos.

By including the outside activities—what is happening in the street—the façade becomes connected to our everyday experience, giving a specific form to Fretton’s interest in what buildings can show. The reflections of the adjacent buildings make us more aware that the windows of the gallery are defined by lines based on the woodwork of the neighbouring 18th-century house. The articulation of the façade to stimulate our visual perception of the surroundings shows Fretton’s interest in the role of images in the relationship between work and observer. This work also exemplifies the relationship that interests Fretton between architecture and the city: an interest in the existing and the given, and not so much in urban planning based on the generic approach of posing problems and solutions. His architecture shows we can understand what already exists as a gift from the city; a sum of deposited layers of the city’s culture, the remains of its construction and existence. This relationship with the given however, does not take place in historical terms, because any architecture, irrespective of the age, returns as part of the present. Therefore, although certain buildings refer to a historical style from the past, its functions and effects talk to us about the present.

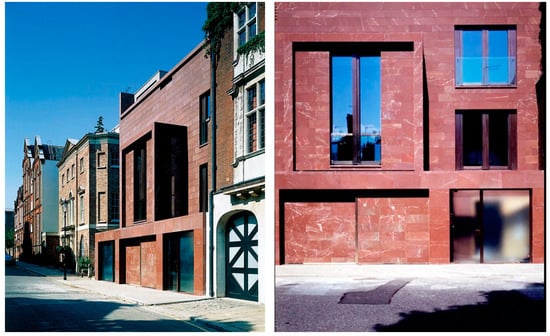

Another design that continues this reflection on the triggering of visual thinking is The Red House (London, 2000). Here, the windows, more than instruments of representation or composition, reveal an interest in the pictorial images of the surroundings and are again designed to look through them and into the inside, especially when they are illuminated. As Fretton says: “as in an Amsterdam townhouse on the canal or in a Venetian palace (…) parts of the ceiling can be seen from the streets, whereas one cannot see the residents” (Fretton 2005, p. 23). This is not an appropriation of the city by the inside, it is an appropriation of the inside by the street (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The Red House, Chelsea, London, 2000, Tony Fretton. © Hélène Binet.

What is true in the windows is also true in the rooms. The living room located on the piano nobile, with its high ceilings and large dimensions, acts as a kind of exhibition hall for the collection of paintings and sculptures, with no other purpose than for the observer to experience the works and their spatial context. This space is autonomous from the other rooms; it does not follow the same spatial logic that defines the rest of the inside or a functional logic, or a specific representation of the functions. At first sight, this autonomy produces a certain surprising effect, although, later, the elements (large windows, fireplace, etc.) take us back to the neighbouring Victorian properties.

Tony Fretton, in a reappraisal of the iconic, has referred to the different forms of abstraction that constitute the basis of his work. This is a process in which the features of the building are generalized to the point where they can be reproduced without the feeling of literality. Abstraction is critical for thought and consists of gradually dispensing with the qualities of an object that are not important to its very existence as such. In looking as a form of thinking, which Rudolf Arnheim has defined as visual thinking, abstraction is present from the start. “Seeing means grasping a number of striking features of an object”; “visual perception is visual thinking” (Arnheim 1954). Through these features, the object is shown as a model of visual forces, from where its iconic logic and expressive ability arise.

Lisson Gallery and The Red House are eminently urban in character. We are not surprised by their inventiveness, but by the way in which they push conventions, so that they become familiar and, at the same time, unfamiliar works. Although they are modern in their language or materiality, they provide continuity to many aspects of the surrounding buildings. This becomes a reciprocal process by encouraging the observation of old buildings with new eyes. As the sociologist Arnold Hauser states: “The new results from the old but the old changes continuously in the light of the new” (Hauser 1973, p. 103).

For Fretton, architecture’s communicative power lies precisely in bringing into play our experiences and our personal interpretations; “the facades of our buildings result from our interest in what buildings can say or do in relation to the world around them” (Fretton 2008). Ultimately, images are based on iconic logics, the foundation for our visual thinking and where the capacity for visual abstraction becomes decisive. The understanding of a work also lies in the forms, materials and colours functioning as symbols—although legible symbols—and keeping them legible is precisely the objective that Fretton pursues in his works: “What interests me as a designer is the way the objects, including buildings, are originated and gain meaning from the things that preceded them, how they are transformed in use and in people’s imagination and how they play a part in the world of ideas, experience and appearance in making sense of the times” (Fretton 2004, p. 74).

4. Conclusions

While in the past Art History generally accepted a philosophy based on a temporal progression, contemporary contributions have attempted to escape from this model, by insisting on other ways of understanding time and events. This is the case with phenomenological responses in their evaluation of the perceptual and the present moment, what comes to meet us instead of what we bring with us. Philosophers such as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari argue that human experience is determined by ontological multiplicity (events) that goes beyond any attempt to establish the self as a unified entity that underlies the reality to which humans respond. They therefore reject the ability of linguistic representation to offer a consistent account of that experience (Deleuze and Guattari 1991). From this perspective, the huge relevance of the analysis of the power of images and their social and cultural roles for “Iconic turn” is easy to understand. As W. J. T. Mitchell says: “Visual culture is the study of the social construction of the visual field, and the visual construction of the social field” (Mitchell 2003, p. 252). John Berger also states that what is important is not to see, but to understand how we see things. There is no doubt today that the ways of seeing images and visual objects depend on a cultural construction while ways of seeing shape this construction (Berger 1972).

The analyzed works by Sergison Bates and Tony Fretton show that architecture not only is an extension of our corporeal functions, it has the ability to coordinate our experiences by using its visual and iconic nature to endow them with specific meanings. The most firmly rooted architectural experiences have an impact on our minds as images understood as condensed forms of certain architectural qualities, and the most durable ones are based on poetic and corporeal images that have become an inseparable part of our lives (Pallasmaa 2013).15

These works question the conventions of the idea of representation and visualization of the work, trying to find new places of communication and where the “presence” of the work acquires a renewed value, linked with the idea of realism. Behind the notion of “presence” we can appreciate the desire of these architects for a less mediated relationship with the works, offering interpretative tools that delve deeper into the iconic logics of the observation. The notion of “presence” also refers to the dimension of time, by assuming that the work itself becomes a producer of its own. This notion contrasts with the interpretation of the work as a text, as something passive and inert, rather than as something whose visuality ultimately makes it inaccessible to textual understanding. If the time of the work is not to be limited to the horizon of its creation, the work could escape from any pre-established meaning to enter into its condition as an agent.16 This notion is related to the concept of “aura” developed by Walter Benjamin, or to the idea of “architecture of illusionist space” developed by Le Corbusier, where the focus is on the viewer’s response to the visual object and the role of images as agents in this encounter.17

These works also show that architecture has the ability to fictionalize reality through the transformation of human scenarios into images and metaphors of a regular order and life into architectural narratives of the real. They reveal that architecture plays a relevant role in the creation of images that trigger the awareness of the observer and free their imagination. In his book “The Imaginary: A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination”, Jean-Paul Sartre states that the image exists as “an act as much as a thing” (Sartre 2004, p. 20). In the same vein, regarding this reflection on the act of imagining related not only to the objects but to the act itself, observed works stimulate reflection on visual thinking and iconic logic and make us aware of the need to examine the ways of seeing operating in our culture.18

Images, we could say, not only are vehicles for the communication of ideas, they also act as beings with agency that play a relevant role in architectural culture. Their presence, which is connected to the act of observation imbued with realism, adds richness and texture to methodological traditions and reminds us that all of them will refuse to be restricted by interpretations forced upon them in the present. That is why images will persist in circulating throughout history, requiring radically different ways of understanding and generating captivating narratives on their way. In the field of architecture, this forces us to sharpen our sense of responsibility in the production of images and the need to undertake an educational task to achieve, without rejecting its own life, a balance between the real self of architecture and what its images convey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and J.d.E.; methodology, I.B. and J.d.E.; validation, I.B. and J.d.E.; formal analysis, I.B. and J.d.E.; investigation, I.B. and J.d.E.; resources, I.B. and J.d.E.; data curation, I.B. and J.d.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B. and J.d.E.; writing—review and editing, I.B. and J.d.E.; visualization, I.B. and J.d.E.; supervision, I.B. and J.d.E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is relevant to contrast the “Iconic or Pictorial turn” with the “Linguistic turn”, the latter understood as the conception of phenomena as texts that must be “read” as such (Rorty 1967). |

| 2 | Mitchell defines a theoretical framework around images with the intention of overcoming the prominence that semiotics had acquired throughout the eighties as a source of interpretation and knowledge. He defends a visual field composed of images that exceeds linguistics, advocating a dialogue between pictorial and verbal representations for an understanding of the functioning of our thought. He proposes to understand the field of the visual as a scope constituted from the dialectic between word and image (Mitchell 1994). |

| 3 | In German academia there has also been a fruitful debate on the role of images in contemporary culture. In the development of the Bildwissenschaft (science of the image), Gottfried Boehm’s essays show a renewed attention to the logics of images. In “Was ist ein Bild?” (What is an image?) he enquiries from a philosophical point of view the predominance of the linguistic as an essential form of the meaning of the visual. He maintains that images are part of the operations of language itself, since it makes use of visual metaphors to transfer meaning from one level of meaning to another. Picking up some theories of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Hans-Georg Gadamer or Max Imdahl, he delves into the logos of images, their own ways of shaping reality and their mechanisms for shaping meaning. (Boehm 2011, p. 58). |

| 4 | The text continues: “Visual culture is concerned with visual events in which information, meaning, or pleasure is sought by the consumer in an interface with visual technology. By visual technology, I mean any form of apparatus designed either to be looked at or to enhance natural vision, from oil painting to television and the Internet” (Mirzoeff 1999, pp. 1–3). Mirzoeff also points out: “Wester culture has consistently privileged the spoken word as the highest form of intellectual practice and seen visual representations as second-rate illustrations of ideas” (Mirzoeff 1998, p. 5). |

| 5 | The growing impact of Visual Culture in the academic field lies in its attention to the study of the production and reception of the visual. Visual culture becomes a contrast seen from the perspective of the more recent disciplinary paradigms: social history in Art History and cultural studies and identity politics in Visual Studies (Elkins 2003, p. 32). |

| 6 | It is worth to see the Beatriz Colomina’s interpretation about the ralation between architecture and mass media (in the age of Visual Culture) in “Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media”. In her book Colomina considers architectural discourse as the intersection of a number of systems of representation such as drawings, models, photographs, books, films, and advertisements. This does not mean abandoning the architectural object, the building, but rather looking at it in a different way. The building is understood here in the same way as all the media that frame it, as a mechanism of representation in its own right. With modernity, the site of architectural production literally moved from the street into photographs, films, publications, and exhibitions—a displacement that presupposes a new sense of space, one defined by images rather than walls (Colomina 1994). |

| 7 | The text continues: “When I design a building, I frequently find myself sinking into old, half-forgotten memories, and then I try to recollect what the remembered architectural situation was really like, what it had meant to me at the time, and I try to think how it could help me now to revive the vibrant atmosphere pervaded by the simple presence of things in which everything had its own specific place and form” (Zumthor 1999, p. 10). Also see (Zumthor 2006). |

| 8 | The meeting between Peter Zumthor and Hans Danuser is of interest in order to assess this process of re-evaluation of the iconic; an observation which, on the other hand, is reciprocal, since the way of seeing Zumthor’s architecture developed by Danuser also leads us to review his own photography. The way of seeing that Danuser develops in the photographs of Zumthor’s works does not seek to seduce the observer through a gimmicky visual composition, but rather to accentuate a more analytical gaze that transmits the experience of observing the work through a less conditioned encounter. This notion, which explores the possibilities of the encounter with the work and those of its presence, is effective in order to avoid what happens in most of the images that we can currently see in architectural magazines, the effect of surprise and dazzle. Danuser implies that falling into this complacency would lead to the very ways of seeing that could lead to a shift away from a more critical understanding of the role of images, which is the essential aim of the “Iconic turn” (Adam and Kossovskaja 2013). |

| 9 | James Elkins has redefined a field of art and visuality teaching. In “A Skeptical Introduction to Visual Culture” (Elkins 2003) he asks about “what there is to see” associating it with the time or place in which visual objects are inscribed, and “how we look” with the observer’s ways of looking in relation to the historical-cultural situation in which he finds himself. One of his concerns is how to face and study such a broad topic, for which he draws two lines of argument in his discourse: the multidisciplinary and the multicultural. As for the first, he proposes the overcoming of some methods of the History of Art such as chronological location and stylistic analysis, assuming approaches from various fields of knowledge (philosophy, social sciences, natural sciences, psychoanalysis, etc.). On the other hand, Elkins advocates an approach that prioritises the multicultural, accommodating cultural manifestations of all times and geographic and social spaces. |

| 10 | What is decisive for the iconic turn is not that we have a powerful explanation of the visual representation that dictates the concepts of the theory of culture, but that images form a peculiar point of friction and uneasiness in a whole wide field of intellectual research. From this perspective, it is easy to understand that the analysis of the power of the image and its social roles is one of the fundamental pillars of the visual culture research. |

| 11 | Just as the artist creates a substitute for the world by tracing his own presence, we marvel at the presence of the substitution of our perception, at the same time that we acknowledge the ingenuity that has made it a reality (Benjamin [1936] 2003). |

| 12 | Martin Jay even sees political relations in the Dutch model. While Cartesianism, with its rigid arrangement of space, refers the gaze to a privileged point, the one from where the scene described in all its fullness is observed, in the Dutch model it is an empirical point of view that can provide more or less visibility (Jay 1993). |

| 13 | It should be noted that Dan Graham’s work has been exhibited repeatedly at the Lisson Gallery in London. Especially successful was the exhibition “Dan Graham: Pavilion Sculptures & Photographs” between 9 November 1991 and 8 January 1992. Previously, in 1986, there had been a joint exhibition that includes the work of Dan Graham and Sol Lewitt. In 2001, practically coinciding with Stevenage’s project, the exhibition “Dan Graham: Sculptures/Pavilions” was held between 12 July and 14 September 2001. |

| 14 | W.J.T. Mitchell, on the other hand, does not restrict his analysis to those images of proven aesthetic value, but advocates expanding the field of study by considering that the power of the visual can be given or presented in very different ways. In this sense, he endorses Visual Studies that serve the various families that inhabit Visual Culture, in order to broaden the knowledge of reality and deepen from different perspectives on the changing nature of perception and visuality (Mitchell 2006, p. 105). |

| 15 | Art critic Jonathan Crary argues that visualisation forms, although they depend on a cultural construction, they also have the ability to shape it. He delves into the idea of observation as a corporeal gaze that is central to understanding the forms of perception since the beginning of modernity. Even from a more specific perspective, Crary conceives the body as a visual apparatus and as the basis of a subjective vision closely linked to the development of artistic and scientific language (Crary 1990). |

| 16 | Philosophers or Art Historians such as George Didi-Huberman has built an outstanding corpus around the theory of the image, giving continuity to theoretical models such as those developed by Martin Heidegger, Walter Benjamin or Maurice Merleau-Ponty. In various essays, Didi-Huberman has been critical of Art History’s desire to construct meanings by limiting a less mediated visualisation of the work. He considers that we should not ignore the idea of the encounter with works and images, since regardless of the period of their creation, it is the confirmation that they are still active (Didi-Huberman 2017). |

| 17 | In the 1930s, Walter Benjamin argued that architecture, seemingly of an unquestionable objectivity, was subject of crisis and more and more, architecture was known through photography, and photography construed architecture as image. In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Benjamin maintained that the very invention of photography transformed not only architecture but the “entire nature of art.” Regarding Le Corbusier’s idea of “architecture of illusionist space”, Daniel J. Naegele points out: “Le Corbusier served photography even as it served him. He enlarged it, made it into architecture, and brought its space—the space of representation—into dialogue with the space of reality. The resulting dialectic condition, though architectural, mirrored the condition of photography itself. The photograph is an ‘objective image’, both reality and representation. Its essence is illusion, and it was Le Corbusier’s inclination to recognize illusion as truth and to elevate this truth to an ideal. Illusion can be felt; it can be sensed as the distance between appearance and reality, between what is perceived and what is known” (Naegele 1998, p. 41). |

| 18 | The ways in which perception relates to changes in visuality (Mitchell); the particular natures that constitute the gaze (Elkins); the relationships between perception and the development of artistic and scientific artefacts that shape it (Crary); the paradigms of visuality that shape subjectivity (Boehm); the forms of life with which the images have been and continue to be animated (Belting); the analysis of the way in which human intelligence uses images instead of words in the construction of meaning (Bredekamp); or the understanding of a phenomenological art history determined to recognise the agency of the work of art (Didi-Huberman), show a suggestive theoretical corpus on the forms of the visual and the iconic logics, which represents a suggestive challenge for future research. |

References

- Adam, Hubertus, and Elena Kossovskaja. 2013. Bildbau. Schweizer Architektur im Fokus der Fotografie. Building Images. Photography Focusing on Swiss Architecture. Basel: Merian. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, Rudolf. 1954. Art and Visual Perception. A Psychology of the Creative Eye. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2003. La obra de arte en la Época de su Reproductibilidad Técnica. Colonia del Mar: Editorial Itaca. First published 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bergera, Iñaki. 2017. Photography and architecture. From technical vision to art and phenomenological (re)vision. In Vision Technologies. The Architectures of Sight. Edited by Graham Cairns. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, Henri. 2016. Materia y memoria. In Ursprung, Philip. Brechas y Conexiones. Ensayos Sobre Arquitectura, Arte y Economía. Barcelona: Puente Editors. First published 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, Gottfried. 2011. El giro icónico. Una carta. Correspondencia entre Gottfried Boehm y W. J. Thomas Mitchell. In Filosofía de la Imagen. Edited by Ana García Varas. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Giuliana. 2002. Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Giuliana. 2007. Public Intimacy: Architecture and the Visual Arts. Writing Architecture Series; Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Certeau, Michel. 2000. La invención de lo Cotidiano. México: Universidad Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, Beatriz. 1994. Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, Jonathan. 1990. Techniques of the Observer. On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovici, Irina. 2001. Orientation + Topography (A Conversation with Stephen Bates and Jonathan Sergison). In Papers. A Collection of Ilustrated Papers Written Between 1996 and 2001. London: Gavin Martin Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1991. What Is Philosophy? London and New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, George. 2017. The Surviving Image. Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms: Aby Warburg’s History of Art. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 2003. Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fretton, Tony. 2004. Architecture and Representation. Ornament. Decorative Traditions in Architecture, OASE 65. Available online: https://www.oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/65/ArchitectureAndRepresentation#064 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Fretton, Tony. 2005. Bauten und ihre Territorien. Werk, Bauen+Wohnen 12: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fretton, Tony. 2008. Tony Fretton Architects. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Gadanho, Pedro, ed. 2019. Fiction and Fabrication. Photography and Architecture after the Digital Turn. Munich: Hirmer. [Google Scholar]

- García Varas, Ana. 2015. Crítica actual de la imagen: Del análisis del poder al estudio del conocimiento. Revista Universitaria de Cultura 18: 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Andreas. 1973. Kunst und Gesellschft. Munich: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Martin. 1993. Downcast Eyes. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 1998. The Visual Culture Reader. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 1999. An Introduction to Visual Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 1994. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 2003. Responses to Mieke Bal’s ‘Visual Essentialism and the Object of Visual Culture’ (2003): The Obscure Object of Visual Culture. Journal of Visual Culture 2: 249–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 2006. Mitchell in “What Do Pictures Want?”. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moure, Gloria, ed. 2009. Dan Graham, Works and Collected Writings. Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa. [Google Scholar]

- Naegele, Daniel. 1998. Object, Image, Aura: Le Corbusier and the Architecture of Photography. Harvard Design Magazine 6: 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Simon. 2006. Art Encounters Deleuze and Guattari: Thought beyond Representation. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2013. La Imagen Corpórea. Imaginación e Imaginario en la Arquitectura. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, Richard. 1967. The Linguistic Turn. Chicago: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 2004. The Imaginary: A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sergison, Jonathan, and Stephen Bates. 2001. Working with Tolerance. In Papers. A Collection of Ilustrated Papers Written between 1996 and 2001. London: Gavin Martin Associates. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ursprung, Philip. 2016. La frágil superficie de lo cotidiano. Brechas y conexiones. In Ensayos Sobre Arquitectura, Arte y Economía. Barcelona: Puente Editors. [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo, Jesús. 2016. Seamless: Digital Collage and Dirty Realism in Contemporary Architecture. Zurich: Park Books. [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo, Jesús. 2019. Epics in the Everyday. Photography, Architecture and the Problem of Realism. Zurich: Park Books. [Google Scholar]

- Vattimo, Gianni. 1987. El Fin de la Modernidad. Madrid: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, Peter. 1999. Thinking Architecture. Basel and Boston: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, Peter. 2006. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments, Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).