This article uses Lamelas’ work as a lens to examine two aspects of contemporary art and history in Flanders. Firstly, it foregrounds the complex, transnational heritage that Lamelas’ work presents. The article considers Lamelas’ works and exhibitions made in Belgium in the late 1960s and 70s, and again in the early 1990s, exploring his relations to the local artistic avant-garde. Secondly, the text frames Quand le ciel bas et lourd and America: Bride of the Sun within cultural and political developments in Flanders in the early 1990s. The work and show were realized within months of “Black Sunday”, the notorious 1991 federal election that marked the rise of the Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) and, with it, radical-right nationalism in Flanders. Together these sections illuminate how Lamelas’ work might challenge monolithic formations of Flemish art.

1. Lamelas, Antwerp–Brussels

It was 1:55 p.m. in the Belgian city of Brussels when Maria Gilissen, photographer and Marcel Broodthaers’ wife

2, took a black-and-white photograph of artist David Lamelas walking through a busy thoroughfare (

Figure 2). The details of the city can be seen in the cobblestone street, tram train tracks or backdrop of commercial buildings, such as Leonidas the enduring Belgian chocolate company or the no longer extant Banque de Bruxelles. This image is one of 10 taken by Gilissen for Lamelas’ work

Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) from 1969 (

Figure 3). The artwork was to photographically document individual figures in various locations in Brussels or Antwerp at specific times. In Brussels, Lamelas got a picture of art collector Herman Daled at 1:50 p.m., artist Marcel Broodthaers at 2:13 p.m. and Gilissen at 2:40 p.m. In Antwerp, gallerist Anny De Decker is photographed at 1:20 p.m. and her partner artist Bernd Lohaus

3 at 1:30 p.m., collector Isi Fiszman at 4:30 p.m., curator Kasper König at 3:30 p.m., his partner Ilka Schellenberg at 2:45 p.m. and artist Panamarenko at 3:50 p.m. Simply put, these individuals were friends and professional associates of Lamelas. A group of local figures emerging in the Belgian art world that the artist had come to know and work with regularly since moving to Europe in 1968, they constituted what De Decker called the “Belgium group”, which achieved an international reputation as an active “unconstituted, ephemeral and natural” circle in the contemporary art scene (

De Decker and Lohaus 1995, p. 32;

Buren 1995, p. 103). In hindsight they are significant for their key role in the development of post-war avant-garde art in Belgium and internationally. Therefore, it is interesting that Lamelas, an artist from Argentina who started studying at St. Martin’s School of Art in London in 1968, would include himself in this series of photographs.

This is especially so when we look at similar time pieces by Lamelas from 1969–1970, where his presence is conspicuously absent:

Time as activity (Dusseldorf) (1969),

Gente di Milano (1969) and

Film 18 Paris IV. 70 (also known as People + Time: Paris) (1970).

4 In each of these works Lamelas turns the camera towards the city in a documentary manner capturing its people and activity in fragments of time. However, as much as they were meditations on time, they were also profiles of a place. In his words, Lamelas claimed to “appropriate the social and spatial life of the city.” (

Lamelas [2016] 2017, p. 167)

Antwerp–Brussels is equally “site-specific”, a term used by Lamelas to describe the way it incorporated the physical and social conditions of a particular location as integral to the artwork. The cities of Antwerp and Brussels are not only determined by their geographic and urban structures, but also their social relations and, more specifically, artistic network. Lamelas’ insertion of himself into this configuration reveals the extent to which he identified with these locations and contexts, and even imagined himself as a component of them. The photographic series certainly attests to Lamelas being there and having a place within “Antwerp-Brussels” in the year 1969.

In the previous year Lamelas left Argentina for the 34th Venice Biennale to produce

Office of Information about the Vietnam War at Three Levels: Visual Image, Text and Audio (1968) for the Argentine Pavilion. The installation consisted of a glass enclosed office, complete with a teletype machine that transmitted up-to-date information about the Vietnam War from the Italian wire service (Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata), which was then read in several different languages by a live attendant sitting at the desk and documented with an audiotape recording over the course of the exhibition.

5 As Lamelas recalls, a casual conversation unfolded with Marcel Broodthaers who showed interest in the work. Their initial connection resulted in meeting Anny De Decker, Bernd Lohaus and Isi Fiszman, who were also present in Venice, and De Decker’s immediate invitation to present his work for her Antwerp-based gallery Wide White Space at Prospect 68 at the Städtische Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf.

6This first encounter precipitated a longstanding and dialectical relationship between Lamelas and conceptualism in Belgium that materialized in artistic collaborations, exhibitions and broad affiliations. From Venice, Lamelas moved to London to study at Saint Martin’s School of Art and ultimately stayed until 1974, but frequented the cities he had established connections with, primarily Brussels, Antwerp and Paris.

7 In Belgium, Lamelas became part of a roster of European and American conceptual artists represented by the pioneering avant-garde gallery Wide White Space. He exhibited repeatedly during the gallery’s lifetime between 1968 and 1976 at both the Antwerp and the short-lived Brussels’ location.

8 Additionally he was included in the gallery’s exhibitions at Prospect 68 and 69, with the installation

Analysis of the elements by which massive consumption of information takes place (1968) and film

Time as Activity (Düsseldorf) (1969). From January to February 1970, Lamelas was given a solo show which featured

Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) (1969),

Time as Activity (1969) and two other photographic series. Antwerp (1969) consisted of three color photographs of the cityscape and timestamps of 11:42 p.m., 1:48 p.m. and 4:30 p.m., respectively. Brussels (1969) similarly indexed the everyday activities of the city in three color photographs. In the absence of a central figure, Lamelas concentrates on the urban details: motor traffic, commercial stores, tree-lined boulevards, eclectic architecture, grey skies and anonymous pedestrians. These three works were recurrent in Lamelas’ exhibitions at the gallery. Wide White Space was also fundamental in the development of his work from the 1970s in the way De Decker and Lohaus supported the making and presentation of Lamelas’ films

Cumulative Script (1972),

To Pour Milk into a Glass (1972) and

Desert People (1975). Apart from his collaborations with Wide White Space, Lamelas exhibited at the gallery of M. Poirier dit Caulier, former owner of X-One Gallery in Antwerp, in 1974 and at the Palais des Beaux-Arts Brussels in 1976.

By the late 1960s Brussels and Antwerp were emerging as important artistic centers for avant-garde art supported by the very network of curators, gallerists and collectors photographed by Lamelas. In addition to Wide White Space’s opening in 1966, art spaces dedicated to conceptual art emerged over the course of the late 60s and early 70s, notably in Antwerp the gallery Kontakt opened in 1964, X-One Gallery and the experimental platform A 37 90 98 in 1969, then the public art center Internationaal Cultureel Centrum in 1970. In Brussels, MTL opened in 1969 and the second location for Wide White Space in 1973.

9 On a broader, international scale these two cities were coordinates within a changed geography of art following World War II. As many scholars have pointed out, a region known as the “artistic triangle” encompassing Antwerp and Brussels in Belgium, Amsterdam in the Netherlands, and Cologne and Düsseldorf in Germany proved to be an active, transnational space that facilitated the development of conceptual art in Europe and abroad (

Decan 2016).

10 De Decker and Lohaus in particular envisioned Wide White Space as an international gallery, which had a particular orientation towards contemporary artistic trends surfacing across Europe and the United States.

11In this sense, the ambitions of Wide White Space and Lamelas were similar as both cultivated a modality of cosmopolitanism. Curators, from Inés Katzenstein to Kristina Newhouse, have described Lamelas as a nomad and perpetual foreigner and this ultimately determined his work. For Katzenstein,

Antwerp–Brussels (People + Time) is evidence of Lamelas’ “true cosmopolitan” character, which she defines as “an orientation, a desire to mingle with the Other” as well as “a stance of aesthetic and intellectual openness vis à vis diverse cultural experience” and “a familiarization with different cultures.” (

Katzenstein 2006, p. 80)

12 The significance of the work to actualize modes of cosmopolitan and vernacular belonging had implications for Lamelas, particularly in terms of the evolution of his work, the development of important professional networks and a level of integration into the local artistic scene (that would later influence his return in the 1990s). In turn, Antwerp, Brussels and its artistic circles are equally rendered as open and transnational.

Marcel Broodthaers, like Wide White Space gallery, was intrinsic to Lamelas’ ties to Belgium’s artworld. A number of photographs from Broodthaers’ archives show the two artists side by side in a display of friendship that developed from their chance encounter in Venice in 1968. One of the last photographic records of them before Broodthaers’ death in 1976 is a series of three black-and-white images of the artists together in Berlin in 1975. They are pictured walking down an empty street, appearing closer to the camera with each subsequent shot. In the last photo, they are in the foreground as Lamelas glances at Broodthaers. The photographs, taken by Maria Gilissen, are preparatory images from an unfinished collaborative film project.

13 This piece can be read as an extension of Lamelas’ filmic and photographic studies that fused time, place and people. As much as Berlin was a main subject, there is also continuity with Lamelas’ interest in representing his friends, evinced in

Brussels–Antwerp (People + Time) and again in 1973 when he photographed his social circle for

London Friends (1973). The city’s topography was again both spatial and social, in the sense of artistic connections situated in urban space or in specific places where artistic collaborations emerged and concepts developed. Ultimately, Broodthaers and Lamelas’ unrealized work demonstrates the extent to which their friendship was a basis for artistic collaboration and influence that would shape their work over the years.

In similar terms Broodthaers would involve his social circle in the operation of his fictive institution

Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles in a series of open letters. Writing from the position of Museum Director, Broodthaers authored a number of statements as letters, often addressed to friends, yet distributed publicly. In one letter from 31 October 1969 the artist addressed “mon cher Lamelas” (my dear Lamelas) in what Benjamin Buchloch argued was the “most pointed critique of the conceptual movement to be articulated by one of [its] artists”, referring to Broodthaers’ position that the “reality of the text” was not synonymous with “the real text” (

Buchloch 1987, p. 97). Despite Broodthaers’ apparent critique, the artist mimics the numerated sequence of statements typical of conceptual artists’ work, such as Lawrence Weiner’s

Statement of Intent (1968) and Sol LeWitt’s

Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969), as well as the prevalent culture of exchange among conceptual artists and critics.

14 His letter to Lamelas echoes several mentions to the artist, including one open letter written from Antwerp on 11 October 1968 in which Broodthaers lists a series of “art recommendations”, including Lamelas, among 19th century French caricaturist J.J. Grandville, Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and 20th century Belgian Surrealist artist René Magritte—Ingres and Grandville being two artists that he represented in his

Musée d’Art Moderne (

Broodthaers 1968).

As many scholars have noted, Broodthaers was enchanted by 19th century French art and literature, best exemplified in the artist’s references to painters Ingres and Courbet in his

Musée d’Art Moderne and poets Stéphane Mallarmé and Charles Baudelaire in his exhibitions, films and books. His affinity to poetry is no surprise given that Broodthaers was a poet until he seemingly abandoned this form to make art in 1964. As Rachel Haidu has remarked, Broodthaers’ use of French literature verged on a complex relationship to history, contemporaneity, authorship, identity, quotation and aura (

Haidu 2010). In 1969–1970 Broodthaers would attend a seminar on Baudelaire in Brussels given by French Marxist philosopher Lucien Goldmann, which became a source for his book

Charles Baudelaire. Je hais le movement qui déplace les lignes (1973) and likely influenced several of Broodthaers’ films made in 1970 that use Baudelaire’s life and poetry as its subject.

Nearly 20 years later Lamelas would gesture towards Baudelaire in the making of

Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the sky is low and heavy) (1987–1992)—a public installation for the exhibition

America: Bride of the Sun—500 years of Latin America and the Low Countries at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA). Lamelas’ participation in the show marked his return to Belgium, after a period of distance and relative disengagement since moving to Los Angeles in 1976.

15 This time Lamelas moved to Belgium, living there intermittently from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, which coincided with a retrospective interest in the country’s post-war avant-garde.

16 During these years in Belgium, he formed a network with a new generation of curators and gallerists, which catalyzed a series of exhibitions of Lamelas’ work in the country. In 1991, for example, Lamelas had a solo exhibition at Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, a gallery run by Broodthaers’ only daughter, Marie-Puck. The show, titled

Lavandula,

Labiatae,

Lamiales, included different species of lavender shrubs planted across the gallery floor as well as works that reveal a sustained interest in nature, plant life and its effects when placed within or against spatial structures, like in the drawing and maquette of

Tree inside a glass house (1990) (

Figure 4). A later work,

Bridge between two trees (1996), made for an outdoor group exhibition in a small town in the province of Antwerp, Zoersel, linked two trees with a steel structure and is another instance of Lamelas’ visual language in the 90s.

Quand le ciel bas et lourd,

Lavandula..., and

Bridge between two trees exemplify Lamelas’ engagements with time, large-scale sculpture, site-specific installation, and organic environments in the early 1990s. As Dirk Snauwaert, curator of Lamelas’ 1997 retrospective

New Refutation of Time noted, Lamelas’ work since the 1980s demonstrated a revived “interest in the conventions of space and architecture through site-specific public works that centered on urban landscape and oppositions between nature and artifice.”(

Snauwaert 1997, n.p.) Moreover, the notions of environment, site, and historical context also inform Lamelas’ work on a more biographical and semantic level. After all, Lamelas admits that Broodthaers was influential in his decision to quote Baudelaire’s “Spleen IV” in

Les Fleurs du Mal (1861).

17 Lamelas evoked Baudelaire’s rather dour poetic representation of melancholy elicited in “the low and heavy sky” and its sense of spatial confinement, of enclosure, oppressive weight and darkness. This condition is mirrored in the work’s three rows of sycamore trees shielded by a large-scale trapezoidal structure of steel that over time would stymie their natural growth. Like Baudelaire’s poem, Lamelas’ work is the “lid/ over the mind tormented by disgust … where Hope,/ defeated, weeps, and the oppressor Dread/plants his black flag on my assenting skull.” (

Baudelaire 1968, p. 88). As the personification of hope is restricted, causing its slow demise and potential death, Lamelas’ trees undergo a similar process of immobility, deformation and sometimes death. While Baudelaire was referring to a depressed condition inherent of modern life, Lamelas draws a parallel to the so-called “discovery of America” thematized in KMSKA’s exhibition.

2. America: Bride of the Sun

In the context of the large-scale exhibition

America: Bride of the Sun, Lamelas’ public artwork operates as a poetic allegory of the European conquest of the Americas—a violent encounter that the exhibition explicitly sought to explore. The year 1992 was the quincentenary of the so-called “discovery” or “conquest” of the Americas by Columbus under the Spanish crown. Sponsored by Unesco, a series of events was initiated across European and American museums that meant to reflect upon this historical moment and the subsequent meeting and cross-fertilization of peoples and cultures.

18 The Flemish Community’s Department of External Affairs seized the opportunity to devise an exhibition and book project about the relation between Flanders and the Americas. The exhibition was set in Antwerp, a city that was a primary trading port with the Americas and home to the most prominent Flemish artists, whose work was exported to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries. More specifically, the organization used the KMSKA, an institution housed in a stately neoclassical building in the city’s Zuid district and administered by the Flemish Community since 1982.

19Central to the exhibition was the role of Flemish art in facilitating the imposition of cultural, political and economic values from Europe to the Americas. Since Flanders, or the South-Netherlands, fell under Spanish rule in the mid-16th century, one thesis of the exhibition was that Flemish paintings, engravings, drawings and sculptures depicting Catholic scenes and motifs were used by the conquista in the process of Christianization and colonization, guiding and in fact fostering cultural, political and economic suppression. In turn, the show demonstrated the cross-pollination of cultures in Latin American art, where indigenous motifs and materials were married to Western image traditions, and how art from Latin America had been imported to Europe. This dual thesis, developed by KMSKA curator Paul Vandenbroeck and Catherine de Zegher, then the director of the art center Kanaal in Courtrai, meant to identify the relation between Flandes y América as complex and multisided. Additionally, the exhibition set out to develop a cultural and geopolitical perspective on Flemish art’s iconography, materiality and form.

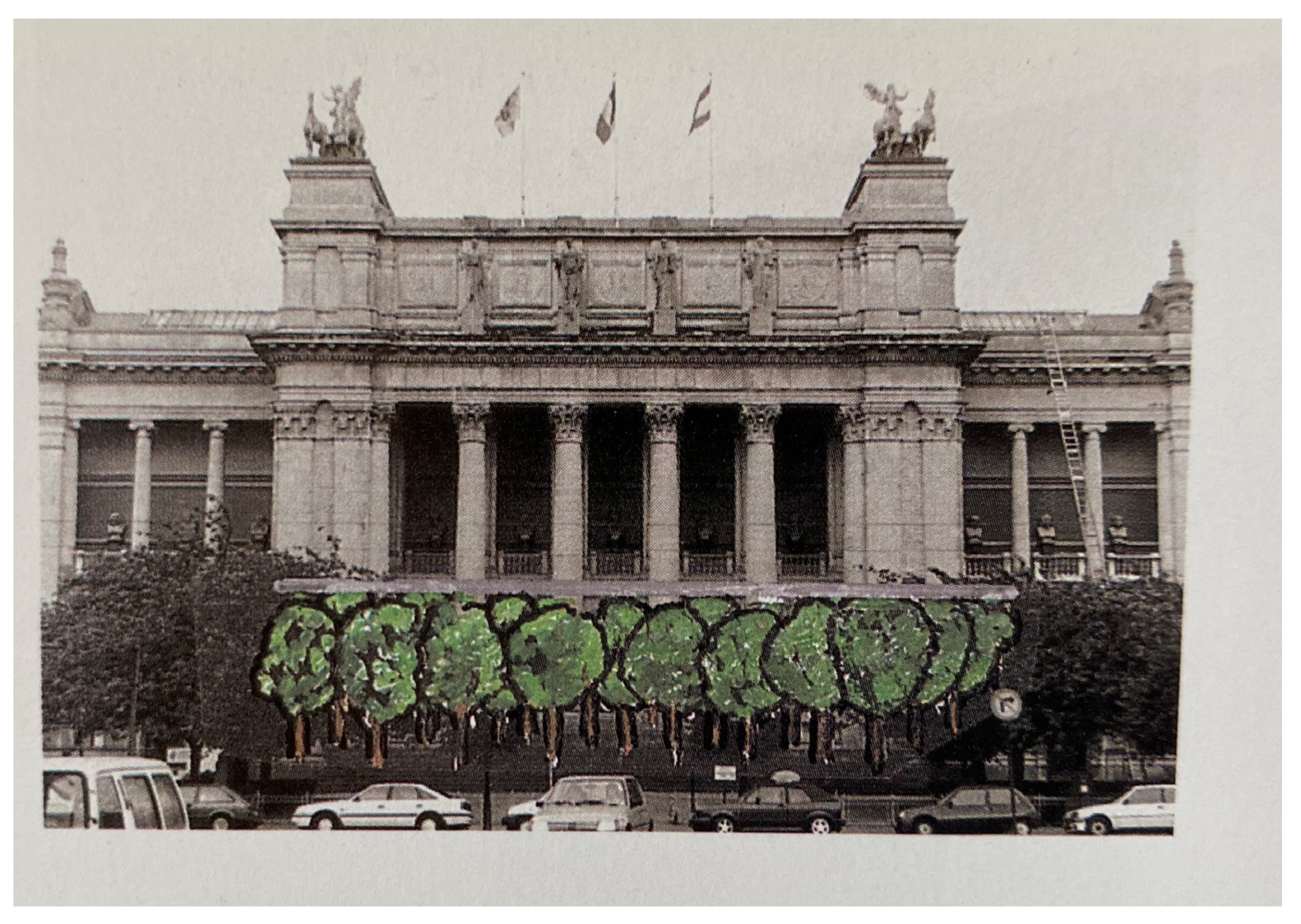

With some 400 works spread across 24-odd spaces on the museum’s ground floor,

America: Bride of the Sun was an ambitious endeavor (

Figure 5). The exhibition was structured in two segments. The first, “Europe’s Gaze,” included artworks and artifacts that allowed re-examining diverse levels—religious, scientific, economic, and sensorial—in the conquering of the “new” world. On display were nautical instruments, Columbus’ reports of his travels, atlases and maps, natural history books, paintings depicting Catholic missionaries and conversion processes, and an 18th-century still life showing imported goods (such as tobacco, tomatoes or chocolate). Here, the exhibition also focused on the pivotal role played by Flemish art in the production and dissemination of a “universal” Baroque across the Atlantic, mainly the excessive, counter-Reformative paintings resulting from the school of Rubens. The second segment, “Labyrinthus Americanus,” examined how Latin American art and culture responded to discovery and colonization, notably how European art and faith was acculturated and enmeshed with local beliefs and customs. This section addressed types of syncretism in paintings and documents showing indigenous men and women (as a representation of gender and role patterns); devotional art mixing Catholic themes with indigenous motifs and materials (suggestive of cultural cross-pollination); and images of fights between angels and devils (a genre associated with Latin American popular culture and an allegory of the battle with the colonizer). The anonymous oil painting

Virgen del cerro (The virgin of Mount Potosí, 18th century), for example, depicts the Virgin Mary as flanked by a sun and moon, symbols common to Inca and European art, and as a mountain evoking an Inca “earth mother” watching over a pre-colonial village at her feet. The image is also suggestive of economical exploitation, since the Potosí mountain was a natural source mined for silver. The painting, which was exemplary of the European interest in the Americas and the labyrinthine effect of their discovery, tellingly featured on the exhibition catalogue’s cover.

Scattered across these thematically structured rooms were contemporary artworks by Latin American artists. In charge was Catherine de Zegher, who in preparation of the exhibition had visited Mexico, Venezuela and Cuba in the aim of tracking modern and contemporary artworks echoing the theme of the exhibition. De Zegher included some 20 modern works and installations by 24 contemporary artists, some existing and others commissioned. These works meant to draw out the long-standing aftermath of America’s colonization, including the enduring entanglements of indigenous and Western influences in art and popular culture. Many of its artists, working across various mediums, are now recognizable figures in global histories of art, and more specifically art from Latin America. From Ana Mendieta to Cildo Meireles, de Zegher showcased key artists in the field of Latin American art working since the 1950s and 60s, which, by the 1990s, with the emergence of global discourses of art and multiculturalism, started to receive greater attention. Moreover, the inclusion of contemporary art meant to transport the exhibition’s historical themes into the present, speculating, for instance, on how Western capitalism and TV images work to bring about a contemporary form of imperialism.

As critics noted,

America: Bride of the Sun offered a nuanced, plural perspective upon colonization and its aftermath in contemporary Latin American art. In presenting Europe’s oppression of the Americas in conjunction with its impact on local art and culture, and in mixing fine art with contemporary works in thematic sections, the show was lauded for its avoidance of both Eurocentric perspectives and Western historiographical models based upon chronology. Art critic Jean Fisher wrote how the “convergences, recurrences, and ruptures” in

America: Bride of the Sun invited viewers “to face [their] own Latin American imaginary in its accumulation and cross-referencing of signs.”(

Fisher 1992, p. 99)

20 Fisher moreover noted how such ideas of decentering were absent from exhibitions such as “

Primitivism” in Twentieth Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (MoMA, New York, 1984) and

Magiciens de la terre (Centre Georges Pompidou & Musée de la Villette, Paris, 1989), which ignored “the context shaping the work and its meanings, not to speak of the sociopolitical and historical formations of the West’s relations with those others who have produced them.”(ibid.) Moreover, critics found

America: Bride of the Sun made explicit the contradictory position of the hegemonic, Western museum in hosting such discourse. The image, formulated by de Zegher in the catalogue and interviews, that installations by Latin American artists on the ground floor were “weighed down” by the exhibition of Flemish Masters and a “universal idiom of painting” exhibited on the floor above, demonstrated an awareness of how the 19th-century museum of the KMSKA was “exposed” as being itself a bearer of the hegemonic values that the exhibition sought to combat. Another facet of institutional criticism arose when de Zegher accused KMSKA director Lydia Schoonbaert of despotism, when the director had drastically altered three contemporary artworks on the grounds of their including organic materials, which could supposedly attract hazardous insects to the KMSKA’s collection.

21While some critics remarked upon the heavy-handedness of the exhibition and the role of artworks as pieces of “evidence” in its hypothesis, overall they valued how the curators, informed by postcolonial theory, spoke in a dialectical tongue about issues like the center and the periphery, the West and its Other.

22 On the other hand, critics failed to notice how this same decentering and promulgation of cultural exchange reverberated with then-current political and culture–political conditions in Flanders. After all,

America: Bride of the Sun opened but a few months following “Black Sunday,” the notorious federal election of 24 November 1991 that marked the historical rise of Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang), Flanders’ radical-right nationalist party.

Established in 1978 as a right-wing offshoot of the Volksunie, a socially democratic Flemish-nationalist party, Vlaams Blok had as its fundamental tenet the establishment of Flanders as an independent state. Only in the late 1980s, however, when the party hardened its campaign and began targeting North African and Turkish migrants, did it succeed electorally. Vlaams Blok saw a dramatic surge in voters in both the municipal elections of 1988 and the European elections of 1989, yet the biggest success came in the fall of 1991, when, in the voting district of Antwerp, more than 20 percent voted for Vlaams Blok and the party obtained 12 seats in the Belgian Senate. Thanks to the nativist slogan “Eigen Volk Eerst” (“Our own people first”) and a provocative campaign image—a giant boxing glove supposedly targeting the bickering and incompetent politicians (but widely understood as a call to arms against migrants)—“Black Sunday” is associated with the rise of far-right nationalism, racism, and nativism in Flanders alike. In June 1992, when Vlaams Blok published its 70-point plan for solving “the migrant problem,” the party openly confessed to its racial and discriminatory agenda.

23 As radio journalist Jos Bouveroux wrote, “priority is given, not to our own people—a feature of all nationalisms—but to a right-wing, totalitarian state.” (

Bouveroux 1999, p. 240).

24While it is important to stress that Flemish nationalism is neither xenophobic nor right-wing per se, it is also crucial to acknowledge their parallels. Both nationalism and xenophobia are premised upon the notion of a “natural” and essential distinction between different cultures and groups of people, between “one’s own” and Others, which makes nationalism attractive as a more publicly accepted form of social discrimination (

Reynebeau 1995, p. 265) Today, both Vlaams Belang and Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA), the conservative Flemish-nationalist party that arose from the vestiges of the Volksunie in 2001, speak of a Western

Leitkultur as the grounds for their disregard of multiculturalism and promotion of homogenous cultural entities.

25The decentering and syncretism presented in America: Bride of the Sun, even if indirectly or invariably, can be seen as responding to this upsurge of far-right nationalism and racism in Flanders. Three features substantiate this claim. Firstly, the show’s catalogue and press texts suggest that the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ “discovery” of America served to address contemporary political developments in Belgium and concurrent discussions about intercultural relationships. In the book’s introduction, for example, Vandenbroeck speaks of different cultures and the idea of the nation as a cultural and political whole in terms that resonate with the then-current political condition of Belgium and nationalism in Flanders:

How, then, to speak of a different culture, or even more difficult, of a patchwork of cultures within one geographical whole? Every approach and choice of subject will carry something random in it, something based upon desires that are difficult to pin down. Every attempt to grasp the “core” or “essence” of a particular culture turns out to be a pious wish: the observer selects a striking category, idea, or structure, which fits his conceptual framework. Additionally, what concerns the contact between “one’s own” and “foreign” culture: one quickly tends to overestimate the role of the former.

Further on, Vandenbroeck notes that along with the taxonomies of the natural sciences, the 16th century saw the rise of racist theories, according to which “other” cultures needed to be fought, destroyed, and, possibly, idealized. This raising of awareness for xenophobia and for the echoes between past and present in the show is also described by de Zegher in an unpublished press text issued by the Flemish Community:

Within the political constellation of Europe, faced with rising nationalism and growing racism, one might wonder if it is still—as if it ever was—possible to develop strategies of multicultural art world politics and to expect political consequences emerging from those exhibitions. We have tried to construct a decentered exhibition project, which does more than simply expand the territory of Western hegemony or art world investment. Additionally, this should be clear in the very structure of this exhibition and the display of the contemporary works (installations) among the old historical paintings and sculptures.

Secondly, the catalogue subtly attests to quarrels about the title between the curators and KMSKA’s director and senior staff. De Zegher initially proposed the Spanish–Dutch

Ver América, which means both “to see America” and “(culturally) far America.” Director Lydia Schoonbaert and senior curator Erik Vandamme, however, were opposed to this predominantly Spanish sounding title on the grounds of its being supposedly pretentious and potentially misunderstood by the public. In a blistering note entitled “Ver gezocht en ver van goed” (“Far-fetched and far from good”), Vandamme wrote that “the title’s subtleties, which generate intellectual pleasure for the in-crowd averse to clichés and striving for ingenuity, are completely lost on the average Joe.”(

Vandamme 1991)

28 As an alternative, Vandenbroeck proposed

inti-coya (Quechua for sun-moon, as an allegory for the contradiction Europe-America), or no title at all, but two strong images. The former was also rejected as sounding too “foreign” (

KMSKA 1991b).

29 These objections and with it the implied schism between an elitist team of curators and an uneducated Flemish public receive an uncanny echo when seen in the light of the far-right nationalism then on the rise. Indeed, the contrast between the curatorial ambitions and the title was so great that both Vandenbroeck and de Zegher stressed their dissatisfaction in the catalogue—the former in his introduction, the latter in “Ver América,” an interview between de Zegher and art critic–historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh.

Thirdly,

America: Bride of the Sun contrasted with the initial project “Flandes y América,” set up by the Flemish Community in collaboration with professor and historian Eddy Stols. This project proposed an exhibition spread across five chapters that would present “the Flemish influence in the development of America, notably the southern part starting from Mexico,” from “cultural and technical collaboration” to agriculture and industry (

Verstraeten 1989). The archives hold only outlines of the project, but these documents nevertheless paint a laudatory picture of Flemish colonial involvement, an all but nuanced story. In contrast, Vandenbroeck proposed a project in which the oppressive features of the “discovery” of the Americas and the Eurocentric viewpoint would be acknowledged (the first segment), and where this view would be divorced from a loose, multifarious exploration of the Latin-American “labyrinth” (the second segment). De Zegher backed this alternative, suggesting how “the influence of the Netherlands” is not a workable criterion for contemporary art, whose internationalism is fundamental (

KMSKA 1991c). That is, if the quincentenary offered the Flemish Community an opportunity to highlight the influence of Flemish art upon the New World, the exhibition eventually painted a historically and politically more nuanced picture. Tellingly, Stols from circa 1991 onwards was no longer included in the meetings yet claimed moral and intellectual property over the original project (thus adding to the aforementioned debates about the exhibition’s title) (

KMSKA 1991d).

David Lamelas’

Quand le ciel bas et lourd was to be the show’s signature work, given its place in the garden courtyard, centrally before the museum. Knowing his site-specific practice, Lamelas did not operate on the premise that art is autonomous and its relationship to its location is incidental. Rather Lamelas consistently forged a loose but conscious dialogue between the work and its site, art and the social, historical, and political context of its production. Curator Ines Katzenstein refers to this relationship as Lamelas’ “situated” practice, in which “the situation in which the piece exists—are the piece’s premise.”(

Katzenstein 2006, p. 78). In the process of developing

Quand le ciel bas et lourd, Lamelas’ early sketches drawn in Los Angeles from 1987, underwent subtle modifications that tailor the work to its location in front of the Antwerp museum’s main entrance. The work was first envisioned as trees supporting a hard minimal plate in a neutral setting. A later second drawing (

Figure 6) situates the work in its new space and specific context, pointing to the obvious association between the work and the museum’s exhibition, but also how its understanding is contingent on space (and time). However, its realization did not run smoothly. Questioning if the work “is appropriate as a face of the exhibition” and if it would not attract vandalism, KMSKA director Schoonbaert proposed moving the work away from the museum’s front (

KMSKA 1991e). Eventually, consent was given for the work to be erected on the east lawn of the museum’s classical garden; yet, the KMSKA stipulated that the trees should be removed after the show closes (

KMSKA 1991a).

The fraught relation between the museum and the work hardly changed after its realization. In fact,

Quand le ciel bas et lourd was classified as a “problem case” (similar to works by Ana Mendieta, Victor Grippo, Regina Vater, and others), due to a need for increased fencing to protect it from vandalism and eventual oxidation of the metal structure (

Schoonbaert 1992, p. 3). Schoonbaert proposed that the work would be donated to either the city of Antwerp or the Flemish community, and thereafter removed. “Should it rest in its place,” she noted, “the pure symmetry characteristic of the neoclassical, nineteenth-century museum building will be completely damaged. The neighborhood will have one more dog toilet—which is, in fact, now already the case.” (ibid., p. 4). At the same time, the second plan of the work and its eventual location affirms the link between the material configuration of the work and the conditions of the site. On the east side of KMSKA’s garden,

Quand le ciel bas et lourd resided close to Wide White Space Gallery’s original locations, evoking Lamelas’ connection to Belgium as of 1969, and of his being integral to the local conceptual art network—with connections to Broodthaers, the aforementioned gallery, and collectors Herman and Nicole Daled.

30 Quand le ciel bas et lourd’s Baudelairean title is just another echo of the intricate ties between Lamelas, Broodthaers and Belgium manifest in the work.