1. Introduction

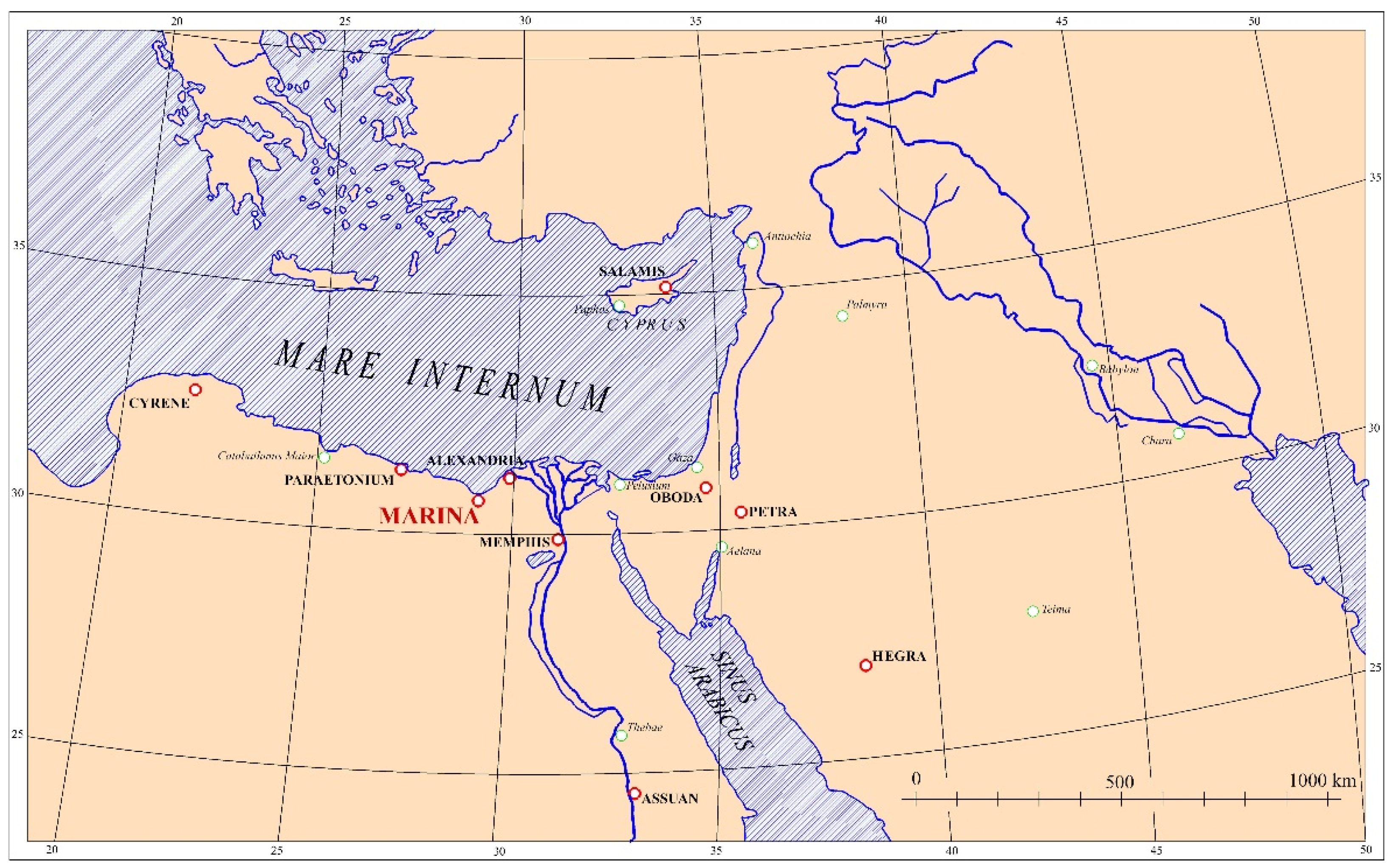

The houses of an ancient town discovered on the Mediterranean coast 96 km west of Alexandria at the site of what is today Marina el-Alamein represent rare, well-preserved remains of Egyptian residential buildings from the Graeco-Roman period (

Figure 1). During research conducted since 1986, the remains of buildings, including over 15 residential houses, belonging to an entire town were excavated along with adjacent necropolises (

Medeksza 1999, pp. 117–18, 121;

Daszewski 2011, p. 421). This constitutes a unique, representative group available for study.

Residential architecture from this period elsewhere in Egypt is relatively less well-preserved and known. However, some examples have been authenticated, including houses from Karanis (

Gazda 2004, pp. 19–23, 27–31), and some analogies can be offered by the funeral house from Tuna el-Gebel in Hermopolis-West with its rich remains of painting decorations (

Gabra 1941, pp. 39–50;

Drioton 1954;

Grimm 1975, pp. 229–31, Taf. 64b, 68–73). The modesty of the remains of residential houses is particularly noticeable regarding the capital city of Alexandria, where the most representative buildings featuring the most advanced technology should be located. In her monumental monograph of Alexandria architecture, Judith McKenzie devotes little space to residential buildings and only a few houses—one is Hellenistic while three from the Kom el-Dikka area are Roman (

McKenzie 2007, pp. 66, 179–83). However, Mieczysław Rodziewicz, Grzegorz Majcherek and recently Patrizio Pensabene wrote about the houses of Alexandria (

Rodziewicz 1984;

Majcherek 2007;

Pensabene 2020b, pp. 67–73;

Majcherek 2021), but they too only describe a few buildings. A famous example of well-researched and preserved houses is the so-called Villa of the Birds, studied and restored by Wojciech Kołątaj, Grzegorz Majcherk and Ewa Parandowska (

Kołątaj et al. 2007), and recently studied by Patrizio Pensabene as well (

Pensabene 2020a, pp. 13–14), although this is an exception rather than the rule. In this context, researchers analysing the architecture of Alexandrian houses refer to analogies, sometimes noting specific details, e.g., that the layouts of hypogea—underground tombs—such as Tomb I in the Mustafa Pasha necropolis from the middle of the 1st century BC, referred to Hellenistic residential houses unknown today (

Pensabene 2010, p. 208;

Pensabene and Gasparini 2019, pp. 177–78). It seemed more obvious to look for analogies in other contemporary places under the influence of the metropolis.

Ancient Alexandria was the main centre and not only the capital of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, and its influence also radiated far beyond the region. Here began the land and sea routes running east to Arabia and Jordan, north across the sea to Cyprus, west to Cyrenaica, then to Africa Proconsolaris and finally to Italy. Centres located along these routes were subject to various multidirectional influences, including and above all from Alexandria. A good exemplification of these influences is the architectural decoration of particular simplified forms, whose origin, as researchers have no doubts today, is Alexandrian, but which may be found in numerous other centres. The so-called blocked-out capitals and generally geometric decorations are authenticated by finds from Petra and Marina el-Alamein, where they prevail, as well as from Dendera, Coptos, Douch, Assuan and Cyprus (

Grawehr 2017, p. 104;

Czerner 2009;

Laroche-Traunecker 2000, pp. 207–12). On the other hand, typical Alexandrian, so-called a travicello (

Pensabene 1993, pp. 99–100, 131;

2010, p. 206) cornices with simplified flat grooved modillions and square hollow modillions are also present in Ptolemais in Cyrenaica, or even in representations of architecture in the 2nd style of Pompeian painting, e.g., in the large triclinium of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor in Boscoreale, or in room 4 of the House of the Griffins in Rome (

Lehmann 1953, pl. 20;

McKenzie 2007, p. 103). The situation is similar regarding the so-called baroque architecture, born in Hellenistic Alexandria and then widespread in the Graeco-Roman world (

Lyttelton 1974;

McKenzie 1996,

2007, pp. 92–4, 113–14).

Today, in the context of the poorly preserved remnants of the buildings that once stood in the ancient capital, centres once under its influence can, by analogy, provide valuable information for the study of a non-existent city (

Pensabene 2020b, p. 73). While it is true that some representative buildings of ancient Alexandria are well-known and have survived in numerous remains, such as the Roman public baths (

Kołątaj 1992), what was a university and its auditoria (

Majcherek 2010), the Serapis temple (

McKenzie 2007, pp. 53–6) and mainly the monumental necropolises (

Venit 2002;

McKenzie 2007, pp. 71–4, 192–94), many buildings are only modestly preserved and identified in research. These mainly include residential houses. For studies on this topic, related to Alexandria and Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt in general, the analogy of the nearby settlement of Marina el-Alamein, heavily influenced by the metropolis, offers some unique and valuable information, albeit on a reduced scale.

3. The Archaeological Site in Marina el-Alamein

The remains of an ancient port town located on the sea and land route running west from Alexandria, were discovered on the Egyptian coast of the Mediterranean Sea in 1985 and scientifically interpreted by Professor Wiktor A. Daszewski from the Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw (

Daszewski et al. 1990;

Daszewski 1990,

1991,

1993,

1995). Along with Egyptian archaeologists, he elected to excavate. Soon, work was undertaken by successive teams of conservators—from 1995, the Polish-Egyptian mission headed by Professor Stanisław Medeksza from the Wrocław University of Science and Technology along with the authors of this article (

Medeksza 1999, pp. 118–19;

Medeksza et al. 2015, p. 1739). He also conducted tandem research work. The discovered settlement is cautiously identified with the ancient town of Antiphrai and the port of Leukaspis, over time merged into one single organism, solely on the basis of descriptions of the coast made by ancient geographers. Among them, the most important are accounts by Strabo (Strabo 17.1.14) and Claudius Ptolemy (Ptol. Geog. 4.5.7).

The archaeological site covers an area measuring approximately 1000 × 550 m along the seashore, encompassing the entire ancient town and necropolises to the west and south. Based on the preserved remains, it can be concluded that the settlement developed between the 2nd century BC and the 6th century AD. The town was not organised on the basis of a regular urban network in the Greek or Roman sense (

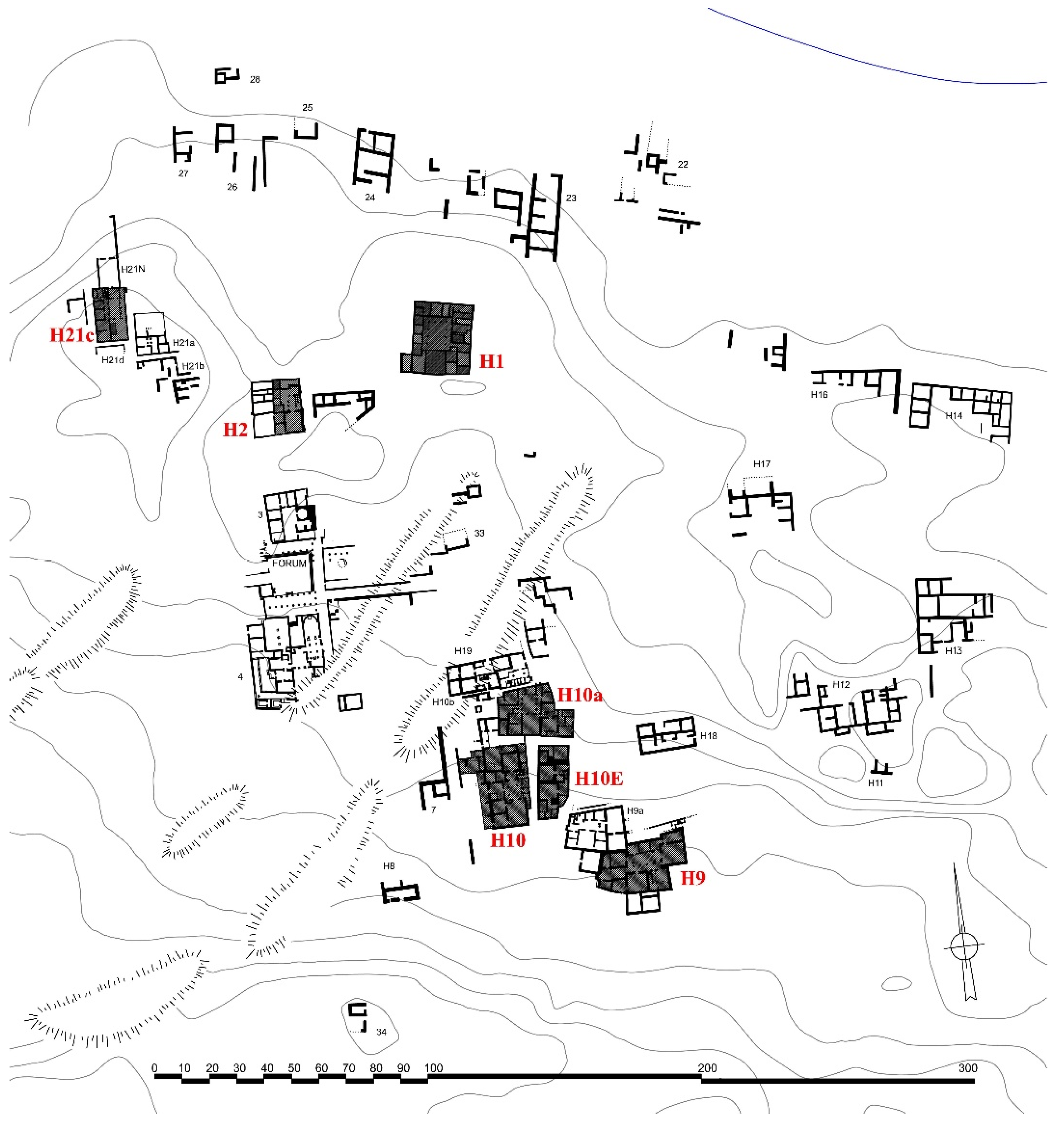

Pensabene 2010, p. 202), but the streets that separated residential buildings were predominantly orientated north–south (leading towards the port) and east–west (the main town arteries). Therefore, it may also be observed that houses tended to be oriented north–south or less frequently, east–west. Archaeological research conducted at the site revealed more than 50 ancient structures: monuments in necropolises, public town buildings, port buildings, squares, streets and vast residential areas. The remains, in particular, include several houses with developed layouts (

Figure 2), dated from the turn of the 1st century BC up to the third century (

Table 1).

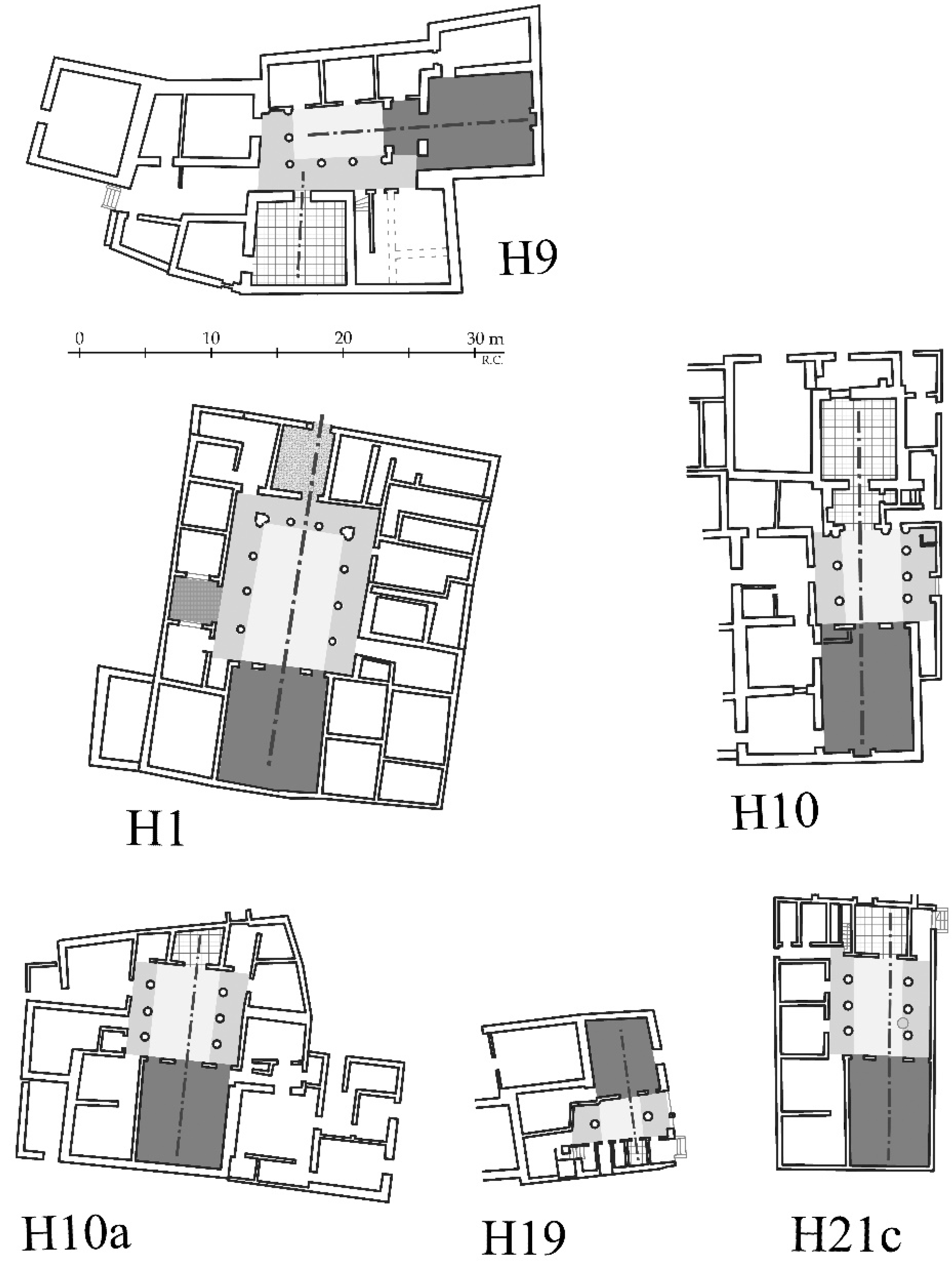

The most well-developed homes of the ancient town of today’s Marina el-Alamein are mainly one of the

oikos type (

Figure 3). Typologically, the few older ones, although chronologically belonging to Roman times, gravitated more strongly to the tradition of Greek houses with a layout of prostas with a vestibule preceding the main hall and pastas with a portico leading into a corridor to the other main rooms (e.g.,

Figure 3, H9). The newer ones were much closer to the tradition of Roman houses. However, in all the houses, the main zone was organised by a paved courtyard with porticoes situated along one axis, sometimes in an incomplete peristyle (

Figure 3, H1), sometimes with only one portico or with an asymmetric two-portico layout (

Figure 3, H9) opening into the main reception room—the

oikos. This room could be accompanied by smaller adjoining rooms.

These main interiors and courtyards were lavishly decorated. The columns and entablature with the cornices of the porticoes and the walls of the main rooms were covered with painted decorations. The wall painting was organised by geometric divisions, filled in various ways. The aediculae dedicated to religious worship and located centrally in the walls of the reception rooms were also polychrome. At least one known case leads to the obvious analogy that probably all aediculae featured figural painting. There are also preserved fragments of figural painting decorations from other contexts. A commemorative monument, located inside the reception hall of one of the houses, was also polychrome. On the basis of the preserved remains, the painted decorations of the houses of the ancient town of Marina el-Alamein may be reconstructed as rich and vibrantly colourful, similar to the Graeco-Roman styles known from other countries and regions, but differing in details.

So far, studies on the layout of houses in Marina and their architecture were mainly conducted by Stanisław Medeksza (

Medeksza 1999, pp. 122–32;

Medeksza et al. 2015, pp. 1742–47). The authors of this article have continued his work. Grażyna Bąkowska-Czerner dealt with polychrome in Marina (

Medeksza et al. 2015, pp. 1752–58;

Bąkowska-Czerner and Czerner 2020, pp. 81–4), while Rafał Czerner investigated decorations (

Czerner 2009, including polychrome pp. 38–9, Figs 64–75). Both these authors studied house décor (

Czerner 2000,

2005;

Bąkowska-Czerner and Czerner 2020, pp. 80–81;

Medeksza et al. 2015, pp. 1748–58). Technology and the conservation of painting decorations were undertaken by Marlena Koczorowska, Anna Selerowicz and Piotr Zambrzycki (

Koczorowska 2019;

Selerowicz and Zambrzycki 2019, pp. 105–9). Zsolt Kiss conducted studies on figural painting (

Kiss 2006,

2008).

During the research mainly carried out in the first years after the site’s discovery, excavated remains of over 15 houses were uncovered, including 10 with extensive layouts featuring portico courtyards. The houses were identified with consecutive numbers in accordance with their chronology of discovery. Various preserved colour elements—colour coatings on architectural decoration, decorated plaster, or indeed polychrome aediculae—come from houses H1 and H2 located north of the main town square identified with the agora or forum, houses H9, H10, H10a, H10E to the south-east of the centre and house H21c in the north-west port zone of the town (

Figure 2). The polychrome on the columns of the porticoes surrounding the main town square and the walls of some public rooms of the baths may be treated as analogous.

4. Elements of Houses with Colourful Decorations: Courtyards

In the portico courtyards, some elements of the architectural design were polychrome, i.e., the columns and cornices were decorated with dentils, modillions, or both. As the architraves of the porticoes were replaced by wooden beams, remnants of which have not survived, no remains of their possible colour decorations are known. Due to the dominance of a simplified, geometrical form of architectural decoration, in particular the use of so-called blocked-out pseudo-Ionian and pseudo-Corinthian capitals and so-called travicello (

Pensabene 1993, pp. 99–100ff, 131) cornices with flat modillions, it was assumed that the missing decorative elements that were not sculptured, e.g., the volutes, could have been painted. However, no arguments or material evidence to support this hypothesis have been found during the research conducted so far.

As the modestly preserved polychrome remains from houses H2, H9 and H10 indicate, the bases of the columns, which otherwise also featured simplified geometry in the form of a cone supported by a ring, were painted black. The shafts of the columns were white and sometimes grey. This colour has only been confirmed on the half columns and pilasters of the aedicula from the main reception hall of house H10. However, a similar niche from house H9 had red pilasters and probably also red half columns. Therefore, the colours of the architectural frames of the aediculae were non-standard and non-repetitive. The grey half columns of the aedicula from house H10 were covered with stucco flutes (

Figure 4). They were separated by narrow fillets but unusually convex. Similar stucco flutes, though lighter, indeed almost white, featured—albeit considered here as an analogy only—on the shafts of pseudo-Ionic columns from the southern portico of the town’s main square: the forum. No remains of similar portico column decoration in the courtyards of the houses have been found. The lack of carved or stucco flutes was not compensated by painting them. This was also not the case with the volute scrolls not carved on the simplified pseudo-Ionic capitals. A polychrome remains on a fragment of such a capital found in house H10E: the front of the volute is red with an edge outlined about 2 cm wide with a black or dark grey-green stripe and a stripe directly under the abacus (

Czerner 2009, pp. 38–39, Figs 70, 71) (

Figure 5). As an analogy, some volutes on capitals from the forum have preserved remains of red paint on the bolsters, and also higher on the abacus. The pseudo-Corinthian aediculae capitals from house H9 bear traces of red paint, following the shafts of the half columns and pilasters mentioned above.

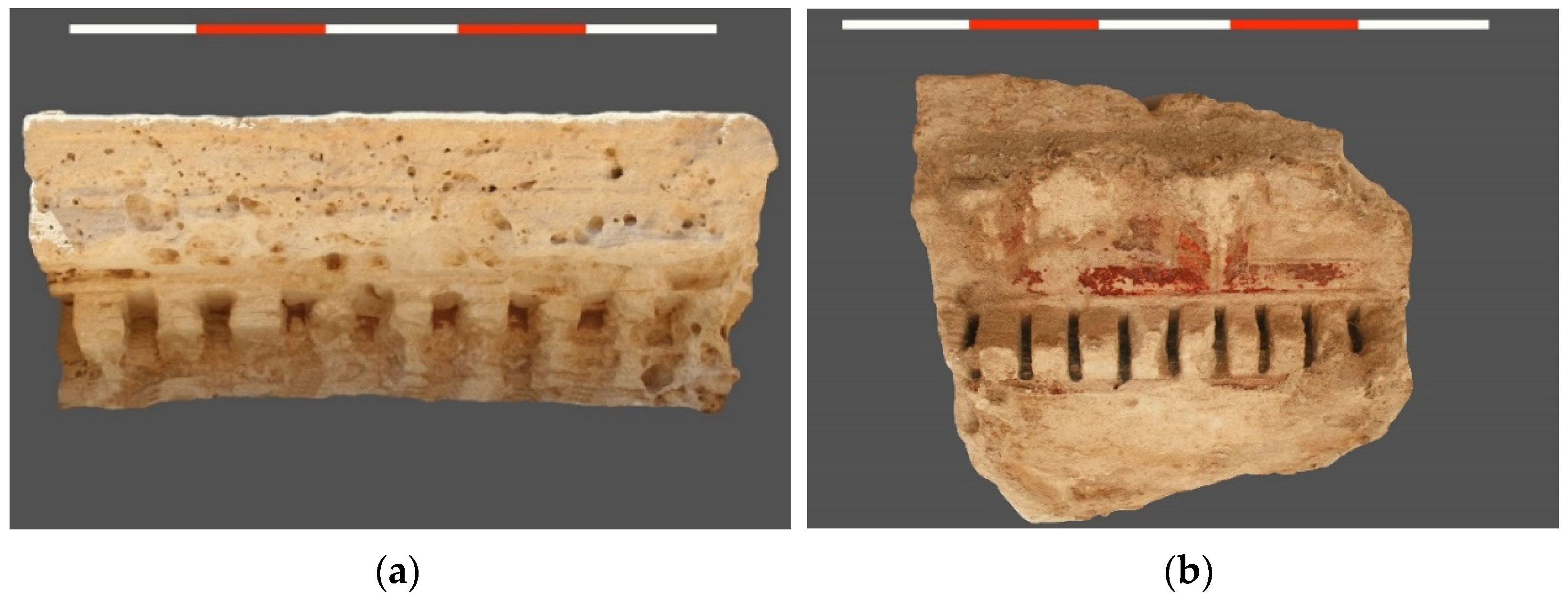

Polychrome traces are preserved on several stone elements of cornices from the porticoes of the courtyards belonging to houses H1 and H10. In the case of house H10, these are very modest remnants of red paint surviving in the spaces between the dentils supporting the geison (

Czerner 2009, p. 38, Figure 67) (

Figure 6a). The cornices of house H1 are more intricate. The geison was directly supported by simplified flat grooved and square hollow modillions. Dentils also ran under them. One of the few preserved elements of this kind of cornice features the preserved remains of polychrome: black spaces between the dentils and red modillions (

Czerner 2009, p. 38, Figure 65) (

Figure 6b). The spaces between the modillions were also red, and therefore all this part of the surface under the geison was red. The peristyle of house H1 was two-storey. The described cornice came from above the ground floor. The cornices of the second storey were less intricate, supported by modillions only. None of the few surviving elements have any preserved traces of polychrome. However, one might hazard a guess that the modillions and the underside of the geison were also painted red. The peristyle of house H1 had pseudo-Corinthian columns both in its lower and upper storey, and therefore capitals. None of the examples discovered bear any preserved traces of polychrome. However, theoretically, two colouristic solutions might have been applied: white heads, assuming that, similarly to houses H2 and H9 (but with pseudo-Ionic columns), the column bases were black and the shafts white; or red capitals, similar to those of the half columns of the aedicula from the

oikos of house H9, where it is worth noting that the dentils of the cornice have red remains, albeit on a smaller scale but similar to here. In both of the theoretically reconstructed cases above, it is assumed that the principle of continuation of the colour of the shafts and capitals is replicated. It should be remembered, however, that the aedicula from house H9 had its own architectural framing decoration, but it was an integral part of the wall decoration and played a role in its colourful décor. Therefore, it might have had a specific colour scheme.

Summarising what we know about the colour scheme of the courtyard porticoes, the columns can generally be said to have had black bases and white or light grey shafts. The pseudo-Ionic capitals had red bolsters and volute fronts with a narrow, two-centimetre-wide framing edge in black or dark grey. The abacuses were also red, inferred from the analogy of the forum portico, although we do not have data to reconstruct the colour of the echinus, supported by a geometrised ring featuring a fillet in place of the astragal. However, referring to Alexandrian analogies (

Tkaczow 2010, pp. 99–100;

Grawehr 2020, p. 38, Figure 6) and the principle of continuing the colour of the column shaft, one might assume that it was white. By referring to the same principle, one can only venture a guess that the pseudo-Corinthian capitals in those porticoes where such columns were installed were primarily all white, or exceptionally all red. However, as a rule, the cornices were supported by red dentils, if this was the only decoration, or by red modillions, which may or may not have been accompanied by black dentils in this case. The colour scheme of the architectural details of the porticoes were therefore not very diverse and featured a modest palette consisting of practically three colours: black, white and red. Of them, only the latter had any vibrancy.

5. Elements of Houses with Colourful Decorations: The Main Reception Halls

The walls of the main reception halls (oikos) were richly decorated. However, remains of painted coloured plaster in adjacent rooms are also preserved. There are also some modest remnants of coloured plaster on the walls of the porticoes in some of the houses. The polychrome on the walls was most often arranged in rectangular fields, filled in various ways, either with a smooth colour or, for example, with marbling, that is, with an imitation of a marble surface. The rectangles were separated by stripes—pilasters or frames—from which smaller fields could be additionally distinguished. Further, sometimes more elaborate decorations could appear in the basic, large fields. There are also some known examples of a figured representation with a grotesque motif appearing in a rectangular field.

In the reception halls of three houses (H2, H9, H10a), traces of polychrome have been maintained on the lower parts of the walls. These are the remains of black painted plinths. Examples can also be found in other rooms (e.g., in house H9), sometimes reaching a height of 0.48 m. However, traces of painting above the plinths are rarely preserved. In the

oikos of house H10a, a polychrome from the first phase of construction, probably around the turn of the 1st century BC to the first century AD, was found under a floor made of limestone slabs (

Medeksza 1999, pp. 126–27, Figure 9) (

Figure 7). The plan of the house from that period is unknown and it is not certain whether there had also previously been a reception hall in this place. Above the black plinth, a horizontal stripe is painted in an intense green, with two rectangular panels above and a black pilaster between them. On both sides there are the same green stripes as over the pedestal, running upwards. The vibrant hues of the panels contrast with them. On one side there is red, surrounded by a wide yellow border, and yellow with a red border on the other side. The preserved colours are saturated, vivid, and when combined, they create strong contrasts. However, it is not known what was above. The situation is even worse in the

oikos of house H2. There, only the remains of the polychrome are visible—a black plinth in the lower parts of the walls. More can be said about the decoration of the

oikos in house H9. The remnants of the polychrome on the southern wall (

Figure 8) enabled the reconstruction of the lower parts of the walls to the height of the aedicula (

Bąkowska-Czerner and Czerner 2020, pp. 81–82) (

Figure 9). Square fields have been separated over the black plinth, interspersed with pilasters. Unfortunately, the colours were poorly preserved. It seems that the pilasters were reddish, and the panels were alternately blueish green and scarlet, or almost purple. These squares were painted with circles of different hues. Plain yellow was applied on the blueish green background and intricate, colourful patterns on the red background. The inside of the yellow circle features tones of maroon, black and white.

The imagined patterns were supposed to imitate stone decoration. Examples of such imitations may be found in Egypt—for example, in Tuna el-Gebel (

Grimm 1975, pp. 229–33, Taf. 64b, 68–70), where they are dated to the 2nd or beginning of the 3rd century, in Alexandria (

Tkaczow 2014, pp. 424, 428)—as well as in Ptolemais (

Żelazowski 2012, pp. 202–13, Figs 35–52) and Pompeii, including the Casa della Caccia Antica

tablinum (

Strocka 1987, p. 37, Pl. IV, Figure 1). Unfortunately, in the

oikos in house H9, no traces of the polychromes painted higher have survived. There were numerous multicoloured and monochromatic plaster chips in the rubble layer, including traces of painted marbling (

Małachowicz 1995). There were also some multicoloured stripes of various thicknesses, or irregular patterns on a white or cream background (

Łużyniecka 1996). Green, black, yellow, red and shades of brown are the dominant colours and there was also some blue. It is not known exactly what rooms these fragments came from. They testify to the rich interior decoration of the house. Rooms outside the

oikos were also painted in intense, vibrant hues. In the rubble layer near the house, a small piece of plaster with a figural painting was found—probably an image of Dionysus (

Bąkowska-Czerner and Czerner 2020, pp. 82–83, Figure 12). This fragment could have been a decorative element of a wall or the interior of an aedicula.

A niche in the

oikos of house H10 was decorated with figural painting. No traces of polychrome have been found on the walls of this room; only white plaster has survived. On the other hand, in the adjacent room to the west on the western wall, coloured plasters are preserved up to a height of 0.87 m (

Czerner and Bąkowska-Czerner 2020, p. 325, Figure 8). A black plinth (0.21 m) was separated by an engraved line from the higher panels and pilasters. Red and black pilasters were framed by a vertical red frame. Between them there were panels alternating brown and black. There are traces of marbling on them. This time, dark hues were applied. This was an access room with three doors, one to the open space, and there was probably an opening in the roof through which light illuminated the interior. Perhaps the upper parts of the walls were painted in brighter, more cheerful colours. Single stone blocks feature a multicoloured red-black-cream decoration, and on one of them, it seems that there was a grapevine composition with a rosette or a head (

Małachowicz 1995). As in the other rooms described above, the preserved pieces of plaster do not provide any basis for recreating the appearance of the upper parts of the walls. The few traces of polychrome found in situ or fragments in the rubble can only suggest that above, there were also imitations of multicoloured stone slabs, and the decoration of the walls resembled the first Pompeian structural style (

Ling 1991, pp. 12–22). Nor is it known whether the entire walls were covered with polychrome, or whether there was a cornice at a certain height, and above it, only white plaster. Only a few fragments of stucco cornices were found in the houses, and many more in the Roman baths (

Bąkowska-Czerner and Czerner 2017, pp. 178, 182, Figure 11). This proves the popularity of such technology in public buildings, so perhaps they featured in homes too. Some walls were divided into rectangles with coloured stripes. A stone block from house H2 is decorated in this way. The designated fields could have been decorated with grapevines or as mentioned above, figural representations, for example, Satyr (

Figure 10). So far, relatively few plant motifs have been found. Usually, small vegetable elements appear or, as on the columns of a commemorative monument, grapevines (

Grzegorek 2019, p. 115, Figure 5) (

Figure 11).

Another example is a fairly simple painting on a wall made of dried bricks in a room in house H2 located just outside the courtyard entrance (

Medeksza et al. 2015, pp. 1754–755, Figure 10). A dark grey plinth is decorated with horizontal stripes, two thin white ones with a wider one in pink maroon. Above it, on a white background, the same thick pink-red stripe appears again, with a thinner red stripe above it. Higher up are what appear to be floating stems, pink in colour, from which flowers bloom (

Figure 12). Their large round heads, surrounded by tiny red petals, were alternately painted red, yellow and green. Three green leaves were placed between the flowers. This is not a painting with a complicated composition, the quality of its workmanship differing from the figural representations, relatively many examples of which have been discovered.

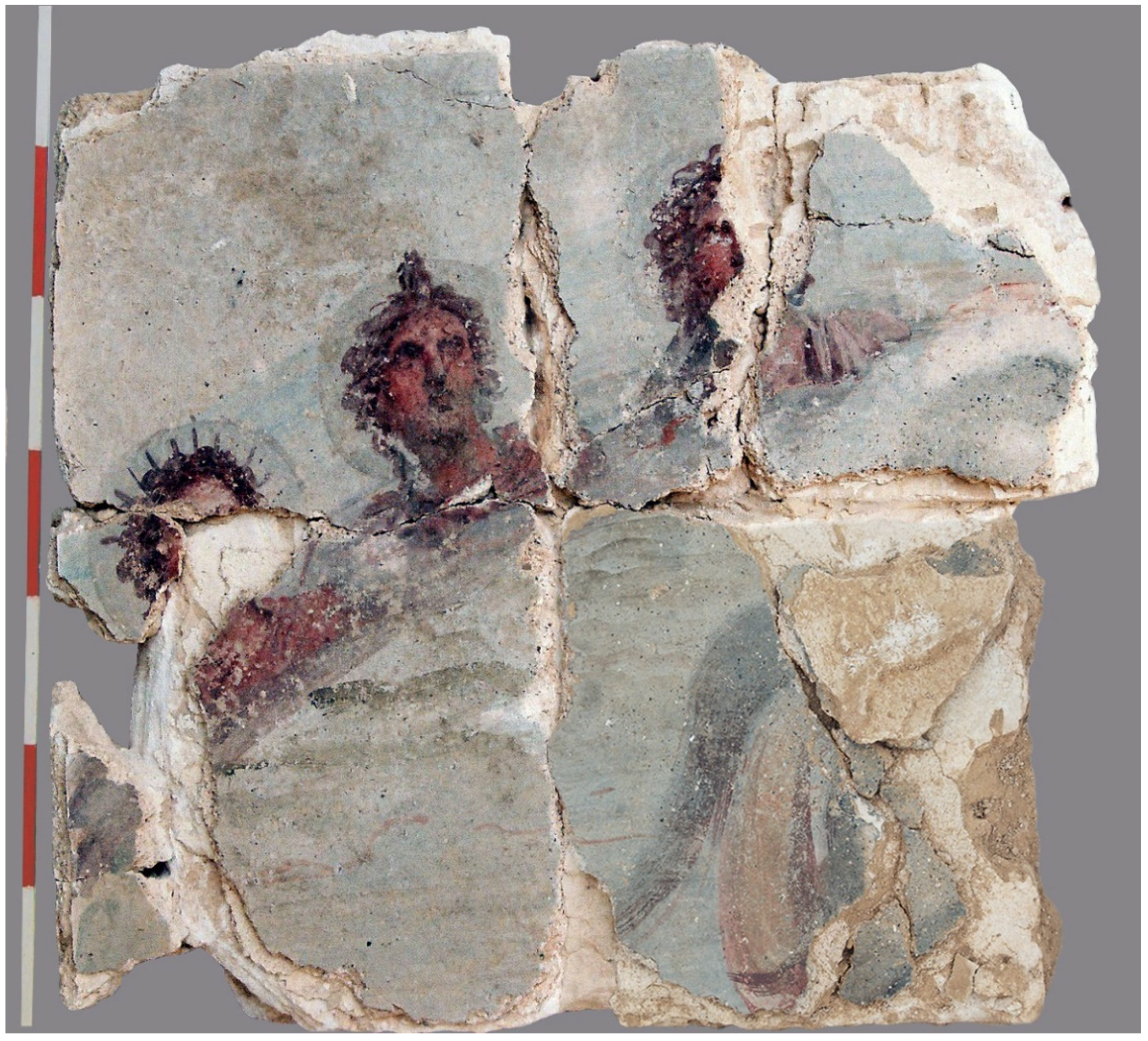

Unfortunately, none have been preserved in situ, but the sites of some have been identified. They mainly represent gods. Serapis, Harpocrates, Helios, and possibly Dionysus are featured, as well as Satyr and a woman in a nautical crown (

Kiss 2008, p. 83, Figure 4) (

Figure 13). Their images are small, their heads being about 10 centimetres in size. The high quality of these paintings is surprising. Unfortunately, only some fragments have survived. Some figures adorned the walls and other niches. An image of Satyr decorated the wall of a room in house H10a, and Heron was depicted in house H10. Serapis, Harpocrates and Helios are illustrated in a niche decorating the

oikos of house H10. It is not known where the woman depicted in the nautical crown, found near house H10E, was located, nor the image of a figure with a yellow halo that may represent Dionysus. It was noticed that the figural depictions were rendered in muted shades. The god of wine was painted brown on a dark brown background fading into black. Satyr was painted against a white background in various shades of maroon brown (

Medeksza et al. 2015, pp. 1757–758, Figure 12) (

Figure 10). Yellow and blue are used to represent garments and grapevine elements. An interesting background was chosen for the woman in the nautical crown: vertical, wide stripes of different colours. Pale red turns blueish, and this fades into light green, as if the figure was depicted against a rainbow. The woman is wearing a brown robe.

Most examples of figural painting were found in house H10 (

Figure 14). One of them was in a room located by the courtyard, near the

oikos, and can be identified with the sacrarium. Two figures were probably depicted on its southern wall, of which only one has survived: Heron (

Kiss 2006, pp. 167–69;

Figure 2 and Czerner and Bąkowska-Czerner 2020, pp. 328–31, Figure 10) (

Figure 15). He was presented against a white background, and dark brown stripes were painted around the entire scene, like a frame. Above the figure, there is a large, red garland tied with green, flowing ribbons. Green also appears at the bottom of the scene—plants painted as if slightly swayed by the wind. They suggest that the scene is set in a landscape. The figure of Heron and the altar in front of him are shown in shades of brown. There is also a fragment of a red robe. The nimbus and

chiton are painted in a strong, intense turquoise hue. The surface of the painting is damaged, but a similar range of colours may be noticed in the image of the cornucopia held by the god.

The most beautiful fragment of figural wall painting found so far comes from a niche in house H10 (

Kiss 2006, pp. 164–66, Figure 1;

Czerner and Bąkowska-Czerner 2020, pp. 325–28, Figure 9) (

Figure 16). These are three busts depicting Serapis, Harpocrates and Helios, painted in various shades of brown and maroon. The lips are highlighted in a subtle shade of red. The robes range in colour from pale pink to maroon. The heads of the gods, surrounded by blue nimbuses, are depicted against a blue background, which represents the sky. There is white above and a greenish hue below with delicately painted tones of green, grey and reddish sea waves. This colour scheme has been preserved, but the hues were probably slightly more saturated. The figurative painting shows expressive figures, as if pausing for a moment. This refers to the patterns of Hellenistic painting. Artists used subdued tones, chiaroscuro, and were able to convey movement and mood.

6. Elements of Houses with Colourful Decorations: Aediculae and a Commemorative Monument

The interior décor of the

oikos was not limited solely to polychrome plaster. As mentioned, the rule was to place a wall niche with rich architectural decorations in the centre of the room at the back, opposite the entrance. The dimensions of such an aedicula, location and colour scheme—best illustrated by the example from house H9—were integrated with the entire decoration of the wall and, therefore, the room (

Figure 9).

The layout and proportions of the architectural frame of the aedicula, regardless of whether it was larger or smaller, was generally repeated in several known examples. It was also special for this town, except that it implemented so-called baroque solutions and forms that originated in the Hellenistic architecture of Alexandria (

Lyttelton 1974;

McKenzie 1996,

2007, pp. 91–7;

Pensabene 2010, pp. 206–7). On a rather prominent parapet, supported by a cyma, pseudo-Corinthian half columns were located, protruding from the face of the wall on both sides of the niche. In the interior of the aedicula, on its side walls, flat pilasters with the same capitals and proportions stood adjacent to the half columns. Both supported an architrave and the lower cornice of a triangular or segmented pediment, whose upper cornice crowned the aedicula. The upper cornice of the pediment could, in accordance with the principles of Baroque architecture, slightly protrude at the ends and retrude at the middle. The lower cornice, which ran around the niche in a “U” shape, featured a much clearer indentation in the central part. Therefore, the pediment did not form a closed frontispiece with a tympanum (

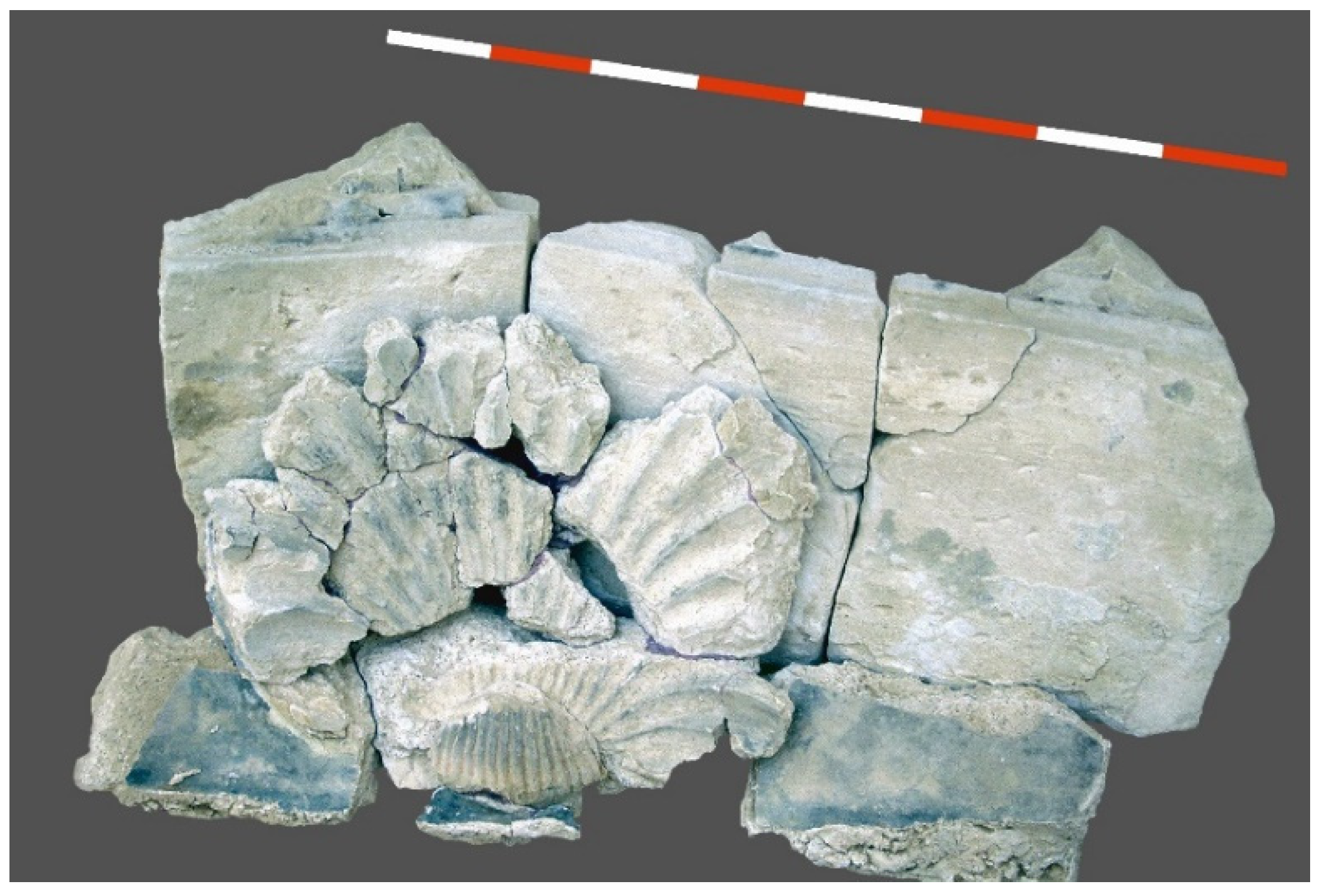

Pensabene 2010, p. 206), but revealed the underside of the panels covering the whole, where there was an additional decoration, which in at least three known cases was a shell motif. The described design was typical and special for Marina’s aediculae.

The aediculae thus described constituted an integral part of the entire interior décor and were therefore appropriately polychrome. The colours can be reconstructed from the modest remains preserved at the time of discovery. In the best-known case of polychrome from the

oikos at house H9, the entire columns and pilasters, i.e., the shafts as well as the capitals, were red, and one might also suspect that the parapet was too, although it has not survived (

Figure 17). This corresponded to the red stripes of the frames dividing off the fields of the wall decoration. Therefore, this differed from the colour scheme of the columns in the porticoes, where only the capitals were red, and only partially in the case of the pseudo-Ionic ones with white shafts and black bases. The colours of the cornices of the aedicula pediment, with black dentils and probably red modillions, were similar to those of the porticoes. Clearly, however, the colours of the architectural aedicula framings corresponded to the colours of the wall and did not follow the principle of colouring architectural elements that can be observed on a larger scale in the porticoes.

Indeed, the aedicula—best preserved in terms of elements and then reconstructed using the anastylosis method—of the

oikos of house H10 presented a different colour scheme. In this case, the plaster of the walls retained very faint traces of white. However, it seems that this was the colour of the interior. Against this background, the aedicula could be, and indeed was, very colourful (

Figure 18). Half columns and pilasters, as well as their bases and shafts, were grey. At the same time, the shafts of the half columns were covered with stucco flutes with a particular convex form. We do not know the colour of the badly damaged capitals. The upper cornice of the triangular pediment, supported by a series of flat grooved modillions, was all blue along with the underside featuring a stuccowork shell (

Figure 19). The lower cornice, supported alternately by the same modillions and wider square hollows, was also blue, but the modillions were red, and the empty spaces in the square ones were black (

Figure 20).

When the decoration of the aedicula was transformed in the second phase, the columns and pilasters were covered with new stucco flutes, this time classically concave, in parts recessed in black. The rest of the shaft decorations were white, and the new attic bases were grey (

Figure 21).

A special object related to the state cult is the commemorative monument of Commodus, numerous remains of which were discovered in the main hall of house H21c (

Czerner and Medeksza 2009). It was built by its western wall at a later stage, despite the aedicula that existed in the southern wall opposite the entrance. The base of the monument was a plinth measuring 4.25 × 1.98 m, 0.71 m high, made from vertically placed limestone slabs and covered with marble slabs. In the front part of this plinth stood four columns, 214.5 cm high, with pseudo-Corinthian capitals. In the background they were accompanied by two square wall pillars of the same form. The pillars and the part of the wall between them were crowned with architraves and a cornice with dentils. Three fragments of marble slabs have been found, on whose side edges a part of a Greek inscription has been preserved (

Łajtar 2001, pp. 59–65;

2003, p. 178). Adam Łajtar read the text as follows: year 23 of Imperator Caesar Marcus Antoninus Commodus (—(has laid or have laid)—) and the chequered work of stibades (—) for the good. Year 23 of Commodus corresponds to the period between 29 August 182 and 28 August 183 (

Łajtar 2003, p. 178). Therefore, the inscription dates the erection of the monument and offers an interpretation of its function (stibades) as a kind of a feast bed. The marble slabs were red, and the shafts of the columns, and probably the pillars, were covered with realistic polychrome motifs of grapevines against a reddish pink background (

Czerner 2009, p. 39, Figure 66) (

Figure 11).

7. Conclusions

The ancient houses at the Marina el-Alamein site provide a plethora of information about the appearance of their interior rooms from the turn of the eras up to the middle of the third century in Egypt. Vibrant colours were applied without fear of bold contrasts. Various shades of brown, red, green, black, white, as well as yellow and blue, predominate. Walls and architectural details were painted. The vast majority of the preserved fragments of polychromes indicate the tremendous craftsmanship of artists active in Egypt at that time. Figurative painting, especially in cult niches, provides information on private worship, indicates which gods were preferred among the inhabitants, and also stands as a testimony to the developing religious syncretism.

Usually, the outer walls of the houses in Marina el-Alamein were covered with white plaster. The courtyard, whose lower walls were decorated with a black plinth, featured white limestone tiled floors. Upon the stylobates stood black bases, from which the white shafts of the columns rose. The most important room, the oikos, also had a white floor and a contrasting black plinth. Above, the wall was filled with an array of colours. They imitated multicoloured stone slabs. The cult niche with its richly decorated and vibrantly painted architectural details would draw the eye. Its interior was decorated with figural paintings executed in subdued tones, representing the deities worshiped by the inhabitants of the house. This was a small provincial town, but one that developed under the influence of the “capital of the world”, cosmopolitan Alexandria.