Abstract

In Ptolemaic Egypt (ca. 332–30 BC), numerous physical spaces served as loci of identity negotiation for elite individuals inhabiting a setting where imported Greek traditions interacted with local Egyptian ones. Such negotiations, or maneuverings, often took place through visual culture. This essay explores a sample of the Greek architectural elements and surface decorations used in wealthy Ptolemaic homes and what they communicate about the residents’ sense of identity. The decorative choices made for a home conveyed information about the social status and cultural allegiances of its owner(s). Some comparisons are possible between Ptolemaic homes in Alexandria, the Delta, and the Fayyum and those from other Hellenistic sites in the eastern Mediterranean such as Priene and Delos. Elites in Alexandria and the Egyptian chora incorporated Greek traditions into their homes and adapted them in increasingly novel ways, creating architecture and surface decoration that was uniquely Ptolemaic. These households were visually in dialogue both with broader Hellenistic trends and with their Egyptian context.

1. Introduction

This essay explores an under-investigated area of elite self-presentation in Egypt during the Ptolemaic period (ca. 332–30 BC): the domestic sphere.1 In Ptolemaic Egypt—where a Greco-Macedonian successor dynasty of Alexander the Great ruled the region, and imported Greek traditions interacted with local Egyptian ones—elites not only expressed their identity and allegiances through art in (semi-)public contexts like temples and tombs,2 they also made selections about their household architecture and ornamentation that reflected their own cultural preferences or what the dominant trends called for. Domestic spaces were both public and private, with certain rooms used for receiving guests and entertaining, and others reserved for private use. Household decoration, especially when applied to the more public areas of the home, allows insight into how members of a household wished to be perceived by visitors and the social practices in which they engaged.

In discussing Greco-Egyptian interactions in the visual culture of Ptolemaic Egypt, I have advocated elsewhere for a framework of hybridization to emphasize people and images as active agents in ongoing processes of exchange and meaning making, rather than using the static labels ‘hybrid’ or ‘hybridity’ (Cole 2019a). Hybridization must, of course, be divorced from a notion of ‘hybridity’ that assumes a preexisting condition of cultural purity.3 We can imagine all manner of hybridization taking place within the home, including in many ways that do not tangibly survive in the archaeological record, for instance through language(s) spoken, dress, and foodways. It is the architectural features and decoration of the physical household that provide the best opportunity to investigate the environments with which individuals and families chose to surround themselves and their visitors when at home. In addition to hybridization, Philipp Stockhammer’s notion of cultural entanglements can also be useful here. Cultural entanglements include a range of different types of interactions. Ptolemaic Egypt, however, does not neatly fit within either of Stockhammer’s two subcategories of cultural entanglement (see Stockhammer 2013). The first is “relational entanglement,” in which objects or images are appropriated by other groups and assigned new meaning, and the second is “material entanglement,” in which new forms are produced as a result of cross-cultural exchange.4 In Ptolemaic Egypt, both types of entanglement occurred, but so did others. Greeks brought their own traditions into a new geographic location and entirely new socio-cultural and political conditions. For some, those practices and images may have retained their original meaning (at least initially) and for others the new circumstances may have altered their meaning, whether they were being used by individual who identified as Greek or whether they were being adopted by the local population. A variety of new, hybridizing forms also developed and drew upon both Greek and Egyptian influences, as well as Ptolemaic dynastic ideology, and they could have different meanings for different members of the population.

Given their high status roles in the Ptolemaic court, administration, military, and priesthood, elites had a unique ability and need to move fluidly amongst different social and physical spaces, choosing particular modes of self-presentation in order to foreground different facets of their identities based on the setting. Visual culture was a powerful tool employed in these maneuverings. In the discussion of household decoration that follows, I raise questions of hybridization (what traditions are interacting in specific visual elements, and why?), entanglement (what meaning do these hybridizing forms have for those employing them?), and maneuvering (what aspects of their identities are people emphasizing, and why?).

This approach asks whether the Greek elements found in Ptolemaic homes during the first century or so of the dynasty’s reign maintained the same significances and functions as they had in their places of origin or whether they might have taken on new meanings, associations, and uses as a result of being located in a new context. Greek domestic architecture and surface decoration that was introduced into Egypt at this time included spaces like the andron (dining room) and the peristyle courtyard, which were often decorated with mosaics and wall paintings, and it is on these spaces and media that this essay will primarily focus. The archaeological and art historical material presented here is widely known and well published; the mosaics in particular, as well as surviving fragments of wall painting, have been thoroughly discussed by Anne-Marie Guimier-Sorbets, whose work is cited throughout. As a sample study that may lay the groundwork for approaches to identity in the Ptolemaic domestic sphere, this essay is not a comprehensive assessment of all available evidence, and I have noted potential avenues for further research. I also chose to adhere to this volume’s focus on surface decoration, only mentioning select examples of relevant textual evidence or objects found in domestic spaces. Additionally, the evolution of materials and techniques used in mosaic, stucco, and wall painting in Ptolemaic Egypt and throughout the Hellenistic world is beyond this essay’s scope and, indeed, this topic has been published on elsewhere.5 Rather than presenting an art historical or technical analysis, I seek to interrogate how architecture and related surface decoration in elite Ptolemaic homes expressed the multivalent and shifting identities of its patrons living in Egypt. Essentially, what meaning did these spaces and their decoration have for their patrons?

Although households remain an underrepresented area of research for cross-cultural exchange in Greco-Roman Egypt, even the narrow range of evidence presented here shows us that homes and other public buildings within the community were important places for identity negotiation and hybridization. Due to the relatively small quantity of material that comes from secure, documented archaeological contexts, many of the statements that can be made about elite Ptolemaic households are necessarily fragmentary or hypothetical. Evidence from northern Greece demonstrates the points of origin for these trends, while excavated domestic contexts from other roughly contemporaneous sites like Priene, Rhodes, and Delos can help flesh out the picture in Egypt, where Ptolemaic elites were consciously keeping pace with the fashions seen across the Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean.

Household archaeology in Egypt remains somewhat sparse for all periods, though this has been changing in recent years (see e.g., Meskell 2002, pp. 94–125; Müller 2015; Abdelwahed 2016; Moeller 2016), and this situation is particularly exacerbated for the Greco-Roman period. Most of the information available for Ptolemaic homes comes from Alexandria, the Delta, and the Fayyum Oasis. A cluster of third-century BC homes was found during a rescue dig at the former British Consulate in Alexandria (discussed below) (Empereur 1998a, pp. 60–61; Empereur 1998b, pp. 29, 33; Grimal 1998, pp. 545–46; McKenzie 2007, p. 67, figure 97, p. 69). A Polish mission at Athribis (north of Cairo) has uncovered parts of the Ptolemaic city, including baths, and the artifacts found include both Greek and Egyptian material (see, e.g., Bagnall 2001, p. 233; Myśliwiec 1995, 1996; Szymanska 1999). A cluster of Hellenistic buildings, including houses, has been found in Tebtunis in the Fayyum (see, e.g., Bagnall 2001, p. 234; Grimal 1998, pp. 522–34; Grimal 1999, pp. 491–97). Excavations in the Fayyum have also uncovered houses from urban environments at Philadelphia and Soknopaiou Nesos.6 These are cities that were intensively developed under the Ptolemies and that attracted a high number of Greek inhabitants who originally came to Egypt to serve in the Ptolemaic military or administration and were settled on land granted by the court. Over time, as these immigrants intermarried with the local population, blended Greco-Egyptian communities formed. By looking at their homes, we can see how members of such communities imported not only physical spaces and their decoration, but also the social functions with which they were associated. Over time, additional layers of meaning related to the Ptolemaic dynasty, and to the lives of elites living in Egypt under Ptolemaic rule, were added.

This essay begins with an overview of Egyptian domestic architecture in the period before the Ptolemies, as well as that of northern Greece. Moving to Alexandria, I overview the recent archaeological work undertaken there—particularly the underwater excavations in the city’s harbor—and how it has altered perceptions of the aesthetic of the capital during the Ptolemaic period. These excavations reveal that, at least at the monumental level, there was a greater blend of Egyptian and Greek traditions in the capital than was previously believed. From there, a group of fourth- to third-century BC homes and related mosaics, painted stucco, and architectural features excavated in the palace district of Alexandria serves as a launching point for a discussion of early Ptolemaic elite homes in which Greek features are prominent. I then look at how these traditions were carried from Alexandria into other regions of Egypt, and what the complex imagery chosen for certain mosaics may have communicated about their patrons outside the capital. I compare these examples with homes from the Hellenistic sites of Priene and Delos to show that trends in Ptolemaic Egypt paralleled those of the eastern Mediterranean, as Ptolemaic elites negotiated identity on a global and local scale. Their ongoing identity maneuvers involved maintaining ties to earlier Greek traditions, demonstrating their connection to an evolving Hellenistic elite koine, expressing allegiance to the Ptolemaic dynasty, and integrating themselves into Egypt as a physical place.

2. Egyptian and Greek Domestic Architecture before the Ptolemies

I will begin by briefly looking at the architecture of Late Period (ca. 664–332 BC) Egyptian houses to demonstrate that they do not belong to the same tradition as the Ptolemaic homes discussed below. Northern Greek predecessors and Hellenistic contemporaries are instead the sources for the architectural and decorative features of those homes.

While there are not many homes from Late Period Egypt that have been excavated and published, those that are known were developed from Egyptian household architecture of earlier phases, as described by Alexander Badawy:

Evidence about the Late Period can be found in the successive layers of houses around the temple at Medinet Habu. The typical plan consists of a tripartite arrangement, which persists well into the Saitic Period except for a period of decline (Dynasties XXII–XXIV). The simpler type is strongly reminiscent of the attached deep house in the preplanned villages at Amarna East and Deir el Medina. This type has a vestibule, a square hall with a dais, and two rear rooms from which rises a staircase. Most of the houses have more than one story. The larger ones are squarish and are fronted by a court containing an underground cellar; they also have a front lobby, a staircase, and two halls.7

A cluster of houses from the 22nd to the 25th Dynasties at Medinet Habu follow the same general conventions (Hölscher 1954, pp. 7–8 and figure 6). The Medinet Habu houses each have a columned main room with a dais, and in a couple of instances there are two small, closet-like chambers accessible from the main room. Houses at Medinet Habu are somewhat irregular, with side streets and entrances from different directions. A group of small homes from the 25th to 26th Dynasties show more regularity and are clustered together more tightly (Hölscher 1954, p. 14, figure 19). These homes had multiple stories. During the same period, a group of detached urban dwellings were built to the south and southwest of the temple (Hölscher 1954, pp. 14–16, figure 20). Each is made up of a sequence of square and rectangular chambers typically consisting of a court/vestibule area, two main rooms, and a series of smaller chambers. These houses also had multiple stories, and the entrances to the homes were not all from the same direction.

During the first millennium BC in Egypt, “tower houses” also became popular. These homes were built on mudbrick foundation platforms and had multiple stories and thick walls. Brian Muhs argues that the increased investment of money and labor needed to create these structures is linked to the rise of temples documenting property transfers more diligently, thus making homes a sounder financial investment (Muhs 2015). This type of house continued to be built through the Greco-Roman period. Homes from several settlements in the Fayyum, including Karanis, Soknopaiou Nesos, Medinet Ghoran, Philadelphia, and Theadelphia, as well as Karnak and Edfu (Apollinopolis Magna) in Upper Egypt, are Ptolemaic-period versions of the Egyptian tower house (see e.g., Nowicka 1969, pp. 105–29; Marouard 2012; Muhs 2015, p. 324, figure 14.2). These houses, though, do not appear to have belonged to the wealthy and there is no indication that they contained lavish interior decoration. For example, a Ptolemaic house from Medinet Ghoran, excavated by Pierre Jouguet, had a roughly tripartite division into a courtyard/vestibule area, a group of main chambers including a central room with a staircase, and a series of smaller chambers, including one that held a grain storage bin (Jouguet 1901; Nowicka 1969, p. 122 figure 75; Husson 1983, p. 31, figure 1, pp. 52–53). Ibrahim Noshy described this house as upper middle-class and noted its similarity to the “middle-class” houses of New Kingdom Amarna (Noshy 1937, p. 56).8 The continued use of Egyptian domestic architecture, even in regions like the Fayyum that experienced a high influx of Greek settlers, demonstrates that Greek architecture was not available to, or practical for, everyone. Rather, individuals made a conscious choice when incorporating Greek features into their homes, and these features likely signaled socio-economic status as well as cultural identity.

A central feature of Greek homes that was adopted in Ptolemaic Egypt was the peristyle—a central courtyard, typically colonnaded, with rooms along three or four of its sides. Peristyle houses generally share certain characteristics, including that the courtyard is the largest individual space in the home, and the rooms along one side are larger than those on the other sides. The side of the court chosen for emphasis was often the north, where the entrance to the andron was most frequently located.9 Another form of Greek architecture frequently found in Egypt are bath buildings, which could be for public/communal or private use.10 For these features, we should look to Greek predecessors and the contemporaneous Hellenistic world.

The most informative site for Greek domestic architecture is the city of Olynthos in the Chalcidice, and the house types found there developed into the domestic architectural forms that were used in Ptolemaic Alexandria. The houses excavated at Olynthos’ North Hill were arranged on a Hippodamian grid plan, which fit two rows of five houses each into one grid, with a drainage alley running between the two rows. Some of the peristyle houses built at Olynthos in the fifth and fourth centuries BC are quite similar to those found at Alexandria (see Robinson 1930, 1932, 1946; Robinson and Graham 1938; Nevett 1999, pp. 53–126; Cahill 2002). Many of these houses contained evidence of a second story (Robinson and Graham 1938, pp. 214–19, pp. 267–80; Graham 1954, pp. 320–23). The courtyard and the andron were the most heavily decorated rooms (Nevett 1999, p. 70). Houses like these provide the original basis from which urban Hellenistic domestic architecture evolved. Smaller peristyle Hellenistic homes exhibit less regularity than the larger homes and palaces of the period, and the urban homes in fact retain the character of Classical Greek peristyle houses (Kutbay 1998, p. 70; see also Graham 1966). Thus, the smaller (but still wealthy) homes found in Alexandria and other Hellenistic cities have a closer affinity to Classical Greek domestic architecture than to large-scale Hellenistic palaces and public buildings, which required ample land.11 The variations found in Classical homes like those at Olynthos were adaptable to urban neighborhoods with limited space.

The Macedonian capital city of Pella, inhabited during the time of Alexander the Great, has yielded examples of large, lavishly decorated buildings of the late-fourth century BC that were associated with the palace.12 These residences or public buildings included multiple peristyle courtyards and their floors were decorated with pebble mosaics (Figure 1). The pebble mosaic’s origins are visible in homes at Olynthos and some of the examples from Pella bear a close resemblance to those found in Alexandria (see below).13 The surface decoration of homes at Pella included not only pebbled floor mosaics, but also molded and painted stucco applied to walls in a zone style meant to imitate the appearance of a plinth supporting rows of expensive orthostats (stone slabs), much in the same manner as the later imitation of marble masonry in First Style Pompeiian wall painting (beginning in Italy around 200 BC). This type of decoration, too, originated in Greece and evidence for it has been found at Olynthos and other Greek sites;14 a more complete example survives from the andron of a peristyle house known as the “House of the Plasterworks” at Pella (Figure 2) (Akamatis 2011, p. 398). While the kinds of sprawling villas in the palace area at Pella were not possible in metropolitan centers like Alexandria, their surface decorations spread throughout the Mediterranean.

Figure 1.

Pebble mosaic floor from a large building at Pella, Macedonia. Fourth century BC. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20160518_307_pella.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Figure 2.

Zone style painting from the “House of the Plasterworks” at Pella, Macedonia. Pella Archaeological Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Macedonian_Museums-40-Arx_Pellas-177.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

The evidence from Olynthos and Pella suggests that the Greeks who settled in Alexandria and its environs brought with them elements of their traditional household architecture, like the peristyle court and the andron, and their interior decoration in the form of floor mosaics and painted wall stucco. How and why did these trends develop as they did in the unique context of Ptolemaic Egypt, and who had access to them?

3. Recent Archaeological Discoveries in Alexandria

Alexandria, the Ptolemaic capital founded by Alexander the Great when he arrived in Egypt in 332/1 BC, was long thought to be a Hellenistic polis with essentially no Egyptian characteristics (e.g., Fraser 1972). Following this assumption was the belief that the aesthetic of the city was fully Greek. This idea was born in part from a Classical bias that dominated the literature on Ptolemaic Egypt, and in part from the lack of archaeological evidence from the city itself. Scholars have also argued over whether there is a uniquely Alexandrian style or Alexandrian school of art that is both distinctive from the art of the rest of Egypt and from the rest of the Hellenistic world (e.g., Kozloff 1996; Stewart 1996; Hardiman 2013).

Archaeologists have had limited access to the remains of the Alexandria’s Greco-Roman period. Portions of the city along the harbor fell into the sea as the result of earthquakes in antiquity and rising sea levels, and the degree of modern development on top of the ancient city puts much of the material beneath out of reach. Today, very little of ancient Alexandria is visible. The two primary remains that visitors can see are the site of the Ptolemaic temple to Serapis (the Serapeum) (Rowe 1946; Kessler 2000; McKenzie et al. 2004; Sabottka 2008), and a Roman neighborhood known as Kom el-Dikka.15 The necropolises to the east and west of the city, which were less disrupted by modern construction, have as a result received more archaeological attention than the city itself. The form and decoration of the more elaborate of these tombs can provide clues about elite households in the city that may have had similar features.16

Views of Alexandria are changing substantially thanks to decades of underwater archaeology in the city’s harbor, which have revealed ancient material that was situated along the coastline, including sculpture and architectural remains from the Ptolemaic palace district (Empereur 1998a; Goddio et al. 1998; Venit 2002; Goddio and Bernand 2004; Goddio and Claus 2006). The excavations have uncovered ancient Egyptian monuments from the Middle and New Kingdoms, as well as the Late Period dynasties, which were transported to Alexandria from their original locations (most of the material coming from Heliopolis) and displayed there. They have also revealed Egyptian-style monuments commissioned by the Ptolemies. The city had a mixed artistic and architectural aesthetic, with Greek and Egyptian existing side by side.

The pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egyptian objects found in the Alexandrian harbor call for a reassessment of the aesthetic of the city in Greco-Roman times. Surrounding the Pharos lighthouse, Corinthian columns stood next to Egyptian sphinxes and obelisks, and statues of the Ptolemies as pharaohs and their queens as Isis welcomed visitors into the harbor. In the eastern harbor, a Hellenistic statue of Hermes stood alongside its Egyptian counterpart—an ibis representing the god Thoth. A sanctuary to the Greek god Poseidon stood near the likely location of a temple to the Egyptian goddess Isis, where a statue depicted an Egyptian priest carrying an image of Osiris-Canopus. These sculptures were related to the Ptolemaic image-building program, as the dynasty sought to integrate itself into the Egyptian pharaonic tradition while maintaining a Hellenic identity.

Underwater excavations have also been conducted at two sites to the east of Alexandria: Canopus and Herakleion-Thonis (Goddio 2007; von Bomhard 2008, 2012; Thiers 2009). Finds are consistent with the material from Alexandria and show that the coexistence of Egyptian and Greek artistic and architectural traditions in Ptolemaic Egypt was not exclusive to the capital. These coastal cities were significant locations for trade and religion in the Greco-Roman period. The Ptolemies built a temple to Sarapis at the site of Canopus, and Herakleion-Thonis had been an important trade center between Greece and Egypt even before Alexander the Great’s arrival (Pfeiffer 2010). The excavations uncovered finds that, as at the site of the Alexandrian harbor, include a mixture of pharaonic Egyptian, Ptolemaic Egyptian, and Greek material.

This presentation of monumental pharaonic material in Alexandria and nearby cities, and the Ptolemaic creation of a dynastic self-image that blended Egyptian and Macedonian traditions of kingship, surely had an impact on visual culture at the non-royal level. It is worth considering whether elites with ties to the court might also have practiced a similar maneuver on a smaller scale, perhaps in their homes.

4. Alexandrian Homes and Their Decoration

From 1995–1997, the Centre d’Études Alexandrines undertook salvage excavations in the Brucheion quarter in Alexandria, in the area to the southwest of the Ptolemaic palaces. A city block including a cluster of four early Ptolemaic homes was found in the area beneath the garden of the former British Consulate (Empereur 1998a, pp. 60–61; Empereur 1998b, pp. 29, 33; Grimal 1998, pp. 545–46; McKenzie 2007, p. 67, figure 97, p. 69). The excavations allowed for the complete reconstruction of the floor plans of two houses (House I and House II) and the partial reconstruction of two more (House III and House IV),17 and it is impossible to tell from the archaeological remains whether the homes contained a second story (Empereur 1998a, p. 60). The houses are directly adjacent and share dividing walls. They likely date to the end of the fourth century BC or the beginning of the third century BC. House III, which has also become known as the House of the Rosette,18 may have been designed with the rooms surrounding a central courtyard in the Greek manner. Other homes in this block have either a central courtyard (House I) or a central entrance corridor (House II). Although it is difficult to tell from Jean-Yves Empereur’s published plan, Roger Bagnall identifies the courtyards of this cluster of buildings as colonnaded, meaning that they incorporated this Greek feature into the central reception area of the home.19 Though courtyards were present in Egyptian domestic architecture, they were not colonnaded, and the introduction of this architectural feature—as well as the presence of significant rooms for social entertaining accessed directly off the courtyard—is taken from Greek households.

The House of the Rosette is so called for a surviving decorative element: a black and white pebble mosaic on the floor of the andron, bearing at its center a six-pointed white rosette on a circular black background, outlined in white, with a black and white diamond checkerboard pattern forming a doormat inside the room’s entrance (Figure 3) (Empereur 1998b, p. 29; Guimier-Sorbets 1998, pp. 227, 229 figure 5; McKenzie 2007, p. 67, figure 97, p. 69; Guimier-Sorbets 2019, pp. 20–22, 24–25, figures 3–7, 3.3, p. 215 cat. no. 1; Guimier-Sorbets 2020a). This is the oldest surviving mosaic so far excavated from Alexandria and it attests to the direct importation of the pebble mosaic tradition from northern Greece. Additionally, remains of plaster reveal that the lower area of the walls was painted in a zone style like that from Pella’s House of the Plasterworks (Figure 4).20

Figure 3.

Mosaic from the House of the Rosette, Alexandria, Egypt. 315–310 BC. 4.68 × 4.64 m. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

Figure 4.

Painted wall stucco from the House of the Rosette, Alexandria. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

The House of the Rosette’s andron is located on the northern side of the house with its entrance off of a central courtyard or corridor. This space was not available for full excavation, but it must have been the main entrance and reception area of the house and it too was decorated with wall paintings in zone style, and it had a pebbled floor (Guimier-Sorbets 2020a, pp. 187–88, figures 22–24, p. 190, figure 25). Painted stucco fragments from the adjacent house to the northeast bore similar decoration (Guimier-Sorbets 2020a, p. 189). The same salvage excavations also uncovered, in an area nearby, a fragmentary painted limestone cornice block showing a meander pattern painted in red, white, and Egyptian blue (Fragaki and Guimier-Sorbets 2013; Guimier-Sorbets 2020a, pp. 202–3, figures 34–37). The block dates to the late third or early second century BC. The fragment was found in a secondary context where it was used as filler but painted architectural decoration like this was likely also a component of the surface decoration in elite Alexandrian homes.

As in the houses at Olynthos, the andron was entered directly from a central space around which the home’s rooms were organized, due to its public, reception function. Their greater visibility to guests also explains why the andron and courtyard of Greek homes were often decorated with mosaic floors and stuccoed walls, while other rooms might remain undecorated or have simple, solid-color pebble floors. Long klinai (couches) would have been arranged around the perimeter of the House of the Rosette’s andron (their placement is indicated by a red band of terracotta tesserae), leaving the central decorative feature visible during dining parties. Guimier-Sorbets has suggested that seven couches fit into this space, making it a heptaklinos type of andron, common in the early Hellenistic period (Guimier-Sorbets 2020a, p. 179). The appearance of this combination of rooms and their decoration in an Alexandrian home suggests that it was not only the physical arrangement and adornment of these spaces that were brought into Egypt by the first generation of Greek immigrants under the Ptolemies, but also their social function of entertaining guests for Greek-style dining.

When the nearby Cricket Ground was excavated, the remains of third century BC houses were also found there. Amongst the ruins were small, ceramic decorative inlays in the shape of fish covered in gold leaf (Empereur 1998b, p. 33). Numerous such inlays, sometimes ceramic but sometimes made of ivory or glass, which would have been used in furniture or wooden boxes, have been found in Macedonian contexts, including in the so-called Tomb of Philip (father of Alexander the Great) at Vergina in Macedonia.21 We can imagine that the furniture used in dining parties in the House of the Rosette’s andron may have been inlaid with such decorative plaques.

The pebble mosaic floor is the earliest of several mosaics found in Alexandria. Mosaics are not attested in Egypt prior to the Ptolemaic period and the techniques, form, and subjects of Alexandrian pebble mosaics follow the Greek originals on which they are modeled. Figural pebble mosaics first appeared in fifth century BC Greece, and the largest number of fifth- and fourth-century BC pebble mosaics comes from Olynthos (Dunbabin 1999, pp. 5–10). These pebble mosaics were mainly restricted to private houses, were made up of a limited color palette of red, black, and white, and were most often found in the andron (dining room) (Dunbabin 1999, p. 6).

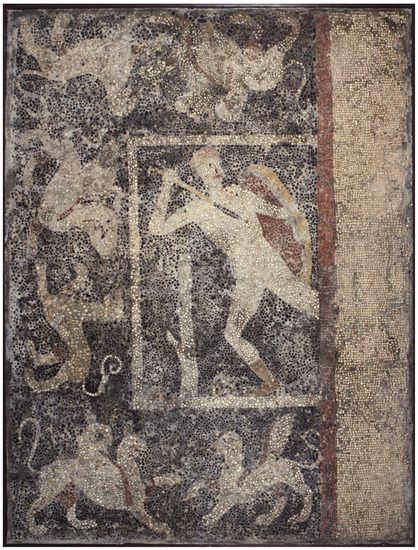

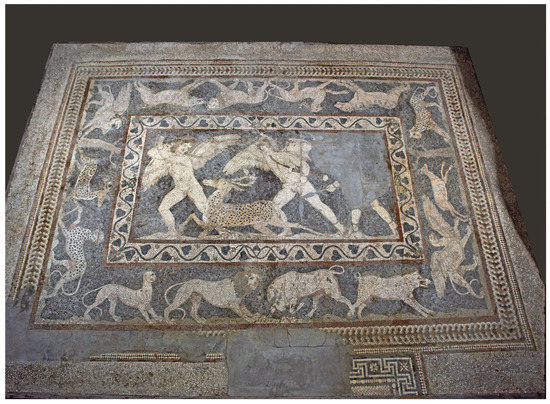

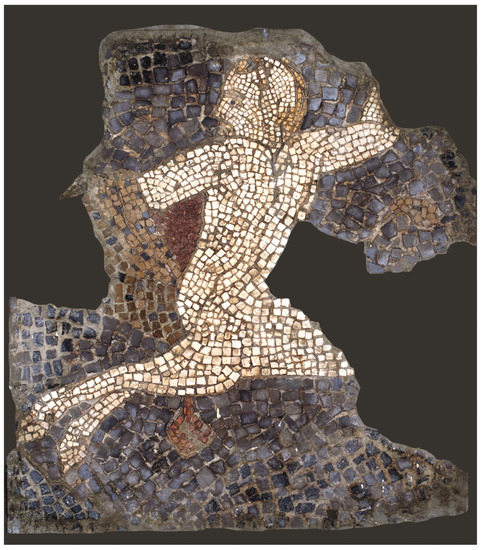

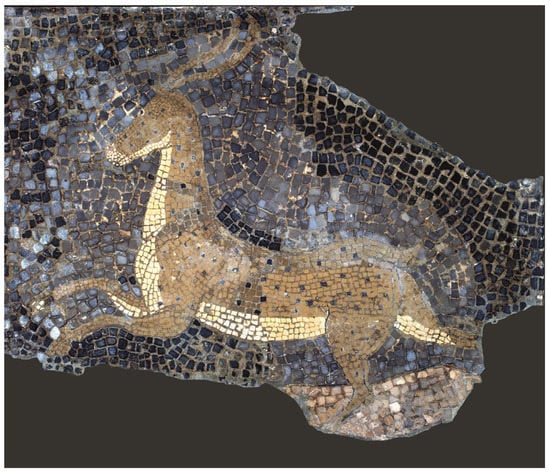

Later pebble mosaics that decorated buildings in the Ptolemaic palace area in Alexandria in the late fourth and early third centuries BC included a (partially preserved) mosaic showing a nude warrior or hunter with a shield and spear surrounded by a border of winged griffins (Figure 5),22 and another showing three winged Erotes hunting a stag, surrounded by a border of real and mythical animals, including two animals that signify an Egyptian setting—the gazelle and hyena (Figure 6).23 Mosaic fragments showing a centaur and a stag came from rooms near the British Consulate (Figure 7 and Figure 8).24 An evolution in technique is visible across these examples, starting with the basic form of the rosette pebble mosaic. The warrior/hunter mosaic uses the standard pebble mosaic palette of black, white, and red, but it is a figural scene in which some outlines are formed by lead strips. Rather than using only pebbles, the composition also incorporates squared tesserae in specific spots for greater precision of detail. This transition to a more refined technique was also occurring elsewhere in the Hellenistic world in the third century BC,25 and its later stages are seen in the other Alexandrian mosaics. The stag hunt mosaic uses the same color palette but is made up mostly of contoured tesserae that produce shading effects, though it still employs limited use of pebbles and lead strips; the fragmentary centaur scene, which also uses lead strips and tesserae of different sizes, reflects a contemporaneous stage of this technique (McKenzie 2007, p. 69). Across these mosaics a transition is taking place from pebble to shaped tessera (opus tessellatum) mosaics (Daszewski 1985, p. 102; McKenzie 2007, p. 69).

Figure 5.

Warrior or hunter mosaic from Alexandria, Egypt. Late fourth-early third century BC. 2.19 × 1.64 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 11125. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

Figure 6.

Erotes stag hunt mosaic from Alexandria, Egypt. First half of the third century BC. 5.25 × 3.95 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 21643. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

Figure 7.

Fragmentary centaur mosaic from Alexandria, Egypt. Mid- to late-third century BC. 0.68 × 0.54 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 25660. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

Figure 8.

Fragmentary stag mosaic from Alexandria, Egypt. Mid- to late-third century BC. 0.44 × 0.41 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 25659. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

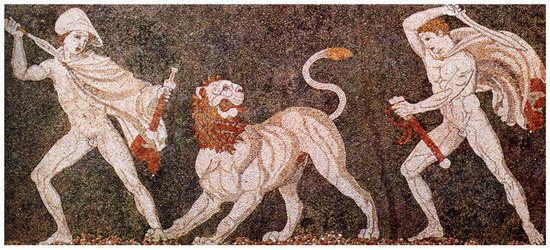

Themes of hunting and combat were closely tied to elite male identity in the Greco-Macedonian world and are prominent in mosaics from Pella as well as in tomb paintings from Macedonia and adjacent regions like Thessaly (see Cohen 2010; Miller 2014, pp. 185–97). Earlier versions of these Alexandrian mosaics can be seen at Pella. Still in situ, south of the columned courtyard of the building illustrated in Figure 1, a black and white lozenge pattern adorns the floor of one room (Petsas 1978, pp. 104–5). To the west of this room, a series of pebble mosaics were removed and taken to the Pella Archaeological Museum, including a lion-hunt scene with two nude male hunters (Figure 9) (Petsas 1964, pp. 5, 6, figure 2; Andronikos 1975, pp. 10–11, 20–23, figures 7–9; Petsas 1978, p. 20, figure 11, p. 28, pp. 53–52, figures 14–15, p. 54, p. 94, figure 8, p. 95, figure 9, pp. 95–97, pp. 108–10 figure 16–19; Dunbabin 1999, pp. 10–12, figure 9; Andreae 2003, pp. 19–22), and a pair of centaurs (Figure 10) (Petsas 1978, pp. 97–98, figure 10).

Figure 9.

Lion hunt mosaic from Pella, Macedonia. Fourth century BC. Pella Archaeological Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lion_hunt_mosaic_from_Pella.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Figure 10.

Centaur Mosaic from Pella, Macedonia. Fourth century BC. Pella Archaeological Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Detail_of_the_pebble_mosaic_floor_from_the_%22House_of_Dionysos%22_at_Pella,_a_male_and_a_female_centaur,_last_quarter_of_the_4th_century_BC,_Archaeological_Museum,_Pella_(6915296986).jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

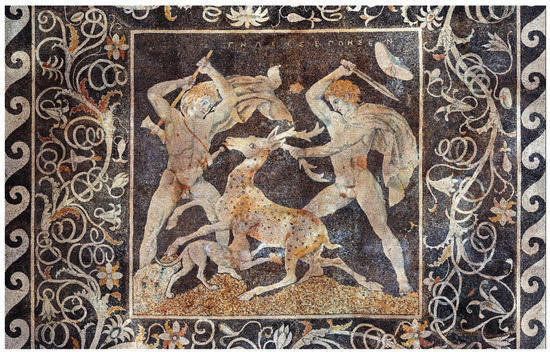

The Erotes stag hunt mosaic from Alexandria echoes Pella’s lion hunt scene—indeed, the figural stances of the hunters are nearly identical—but even more similar to the Alexandrian mosaic is a scene of a stag hunt from Pella (Figure 11) (Petsas 1964, pp. 5, 8, figure 5; Andronikos 1975, pp. 11, 16–17, figures 3–4; Petsas 1978, pp. 99–102, figures 12–14, p. 103, figure 15, p. 139, figure 2; Dunbabin 1999, pp. 12–15, figures 12 and 13; Andreae 2003, pp. 19, 23–24). In this mosaic, two nude youths wearing capes raise their weapons to kill a stag. This mosaic achieves a greater sense of motion and naturalism than the Alexandrian stag hunt—the use of light and shadow, and the rendering of the billowing capes and the hat flying off the head of the man on the right, convey a sense of the figures’ dramatic action. The mosaic is signed ΓΝΩΣΙΣ ΕΠOHΣΕΝ (“Gnosis made this”). Signatures on mosaics were rare in antiquity, and artists seem to have restricted the act of signing to true masterpieces. The Pella stag hunt scene is surrounded by a thick floral border and a thin wave pattern, while the Alexandrian stag hunt is surrounded by an ivy-garland, a larger frieze of animals, and a final geometric border. Like the Alexandrian stag hunt mosaic, the Pella mosaic has a geometric pattern set below and off-center of the main scene that indicates an andron’s doorway.

Figure 11.

Stag hunt mosaic from Pella, Macedonia. Fourth century BC. Pella Archaeological Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stag_hunt_mosaic,_Pella.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Many of the men who immigrated to Egypt during the early years of Ptolemaic rule came from Macedonia and regions in northern and East Greece, and they carried with them their native iconographic traditions and their associated meanings.26 In those places, such iconography often accompanied royal and elite contexts, and its appearance in the area of the Ptolemaic palace district is appropriate for proclaiming the status of the men who held positions at the Ptolemaic court. The houses discussed above would have been owned by a specific slice of the population of early Ptolemaic Alexandria: well-to-do men probably connected to the palace, who would have used their homes for holding large gatherings of important visitors and who wished to surround their guests with sumptuously decorated spaces in which to relax, drink and dine, and socialize.

Even these early to mid-Ptolemaic mosaics already contained images that referenced the Ptolemaic dynastic ideology. Guimier-Sorbets has highlighted the Dionysiac nature of the warrior/hunter and stag hunt mosaics, which are populated by motifs and figures drawn from Dionysus’ retinue, such as griffons, panthers, lions, Erotes, heroically nude figures, and the theme of subduing nature (Guimier-Sorbets 2019, pp. 27, 29–30). Dionysus was an important deity for the Ptolemaic dynasty, so these allusions are no coincidence. Ptolemy II identified himself with the god and may have done so specifically to appeal simultaneously to Greek and Egyptian audiences (see, e.g., Goyette 2010; also Koenen 1993). In the Ptolemaieia festival of around 280 BC, Ptolemy II staged a Grand Procession—a description of which comes down to us in Athenaus’ Deipnosophistae, based on a text by Callixenus of Rhodes—made up of individual processions for various gods, including his deified parents (Ptolemy I and Berenike I), and a spectacular procession for Dionysus, complete with a colossal statue, individuals dressed as Dionysus’ followers, and animals from the east.27 The themes of these Alexandrian mosaics could thus take on different meanings for different viewers, and could be interpreted as references to elite male Greek identity, a connection to the Ptolemaic court, Dionysus’ bridging of East and West, and the Dionysiac character of Ptolemaic divine rule.

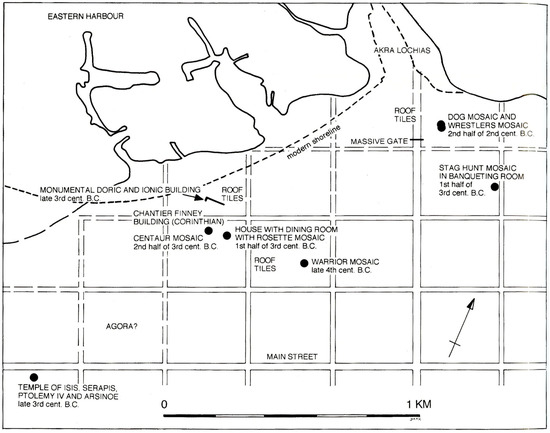

It is not certain to what kind of buildings all of these mosaics belonged, but it is a strong possibility that they decorated wealthy homes in the neighborhoods adjacent to the palace district (see their find spots on Figure 12). The warrior mosaic was found just one block over from the House of the Rosette,28 in one of a series of small rooms that the excavator Evaristo Breccia suggested could have been a private house (Breccia 1907, p. 105). A layer above the foundations of these rooms included architectural fragments of limestone blocks, marble columns, and capitals.29 The stag hunt mosaic was found along with two other contemporaneous simple mosaic floors that all appear to have belonged to a house.30 The stag hunt mosaic is certainly from an andron, as is indicated by the partially surviving offset panel—below and slightly to the right—that marks the position of the doorway. This panel uses a technique of cut stone inlay that is known from Egypt and the Near East in earlier periods;31 like the presence of the gazelle and hyena in the mosaic’s border, this detail hints at the Egyptian context of the mosaic and adds an element not found in similar compositions from Greece. The Dionysiac themes and use of Egyptian animals show the early stages of a development toward specifically Ptolemaic mosaic imagery that is also seen in the chora (countryside) in slightly later periods.

Figure 12.

Alexandria, palace area, plan with Ptolemaic remains found in situ (McKenzie 2007, p. 66, figure 95).

5. Alexandrian Architectural Decoration: Variations on the Corinthian Order

While the general floor plans of Alexandrian homes and the mosaics and wall paintings that decorated them are drawn from traditions originating in northern Greece, and while surviving architectural elements and evidence from Alexandrian tombs demonstrates that the Greek Doric and Ionic architectural orders were used in the capital city,32 there are particular architectural elements that were unique to Alexandria. Certain forms of Corinthian architecture developed in novel ways in the Ptolemaic capital, creating an Alexandrian style that would have characterized wealthy homes and public buildings (see McKenzie 2007, pp. 80–118).

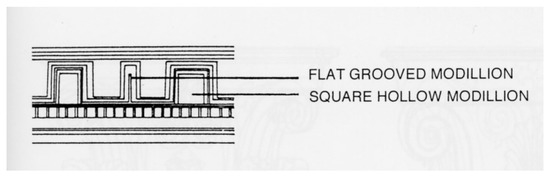

Konstantin Ronczewski surveyed the architectural fragments in the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria and established a series of four Alexandrian column capital types that are unique variations on the Corinthian order that was developing in the fourth- and third-century BC Greek world (Figure 13 and Figure 14).33 Many of these columns stood upon acanthus bases, which Judith McKenzie notes were “influenced by Egyptian architecture, in which the lower leaves of plants, such as the papyrus, were depicted around the lower part of the column” (McKenzie 2007, p. 87). The acanthus bases were supported by a type of base that had its origins in fifth century BC Ionic architecture in Athens (McKenzie 2007, p. 87). Two particular types of Corinthian cornice were unique to Alexandria, one made up of flat grooved modillions, and one that alternated these modillions with square ones (Figure 15). Also particular to Alexandria was the occasional combination of Corinthian capitals with a Doric frieze (McKenzie 2007, p. 89).

Figure 13.

Alexandrian capital types: Type I (a); Type II (b); Type III (c) (McKenzie 2007, p. 85, figure 125a–c).

Figure 14.

Alexandrian capital Type IV (McKenzie 2007, p. 85, figure 126).

Figure 15.

Alexandrian Corinthian order; underside of corona (McKenzie 2007, p. 83, figure 117).

These elements are represented among a group of Corinthian order fragments, now in the Graeco-Roman Museum, found in the Chantier Finney building in the palace district of Alexandria (Adriani 1940, pp. 45–53, figures 14–21, Plates 15–19). Most of the fragments are made of locally available limestone (marble, for which there was no local source, is more rarely used) and they may have belonged to a single building. Based on comparisons with the architecture of Alexandrian tombs, McKenzie dates these objects to the second century BC or slightly earlier (McKenzie [1990] 2005, p. 69; McKenzie 2007, p. 81). A nascent version of this architecture may very well have been used in the early third century BC, as it would not have appeared ex nihilo, fully formed. The building from which they came may have been associated with the palace but was in the same area as private dwellings—in fact, it was quite close to the House of the Rosette and the findspot of the centaur mosaic fragment—and wealthy homeowners may have used some of the same features in an effort to approximate royal structures. Alexandrian architecture took the Greek orders and combined them with Alexandrian base, capital, and cornice types inspired by earlier Egyptian forms to create an individual type of hybridizing architecture that was specific to this location. While the wealthy individuals living in Alexandria were in touch with pan-Mediterranean trends, they also responded to their environment in ways that deviated from the rest of the Hellenistic world and that drew inspiration from the Egyptian setting.

6. Greek Architecture and Surface Decoration in the Egyptian Chora

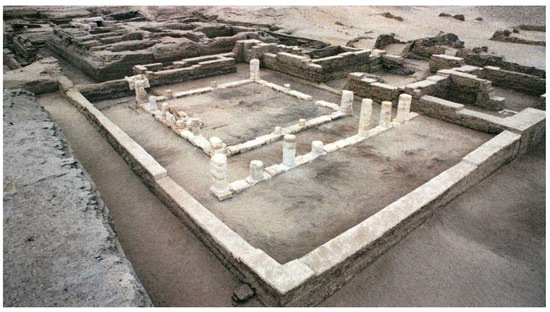

Greek architectural features and mosaics are also known from regions outside of Alexandria. A house of the later Ptolemaic period in Tebtunis in the southern Fayyum attests to the influence of Greek domestic architecture in the oasis. Carlo Anti, who excavated at Tebtunis in the 1930s, discovered a late first century BC home with a peristyle courtyard that overlooks the southwest side of the dromos (ceremonial passageway) leading to a temple to the crocodile god Soknebtunis (Figure 16).34 A staircase leads from the house to the dromos. The layout of the house differs somewhat from traditional Greek peristyle houses, in which the courtyard is the central space. In this case, the principal rooms are all located on one side of the courtyard (the north side) and one must pass through these rooms in order to reach the courtyard. The house also had three secondary entrances that link the building to the dromos and to the related structures of a pyrgos (tower) and a warehouse. It was once thought to be a cult building (Grimal 1995, pp. 590–91; Grimal 1996, pp. 526–34), but Gisèle Hadji-Minaglou suggests that it could have been the home of an individual with agricultural or trade associations that required large storage areas (Hadji-Minaglou 2012, p. 112). A shrine or kiosk, which may have held a statue, was located at the center of the southern wall of the peristyle on the inner side of the court. It is possible that such peristyle courtyards were used in homes in the Fayyum prior to the first century BC but have simply not survived in the archaeological record.

Figure 16.

Home with peristyle courtyard at Tebtunis, Egypt. Late first century BC. © Ifao.

The majority of Ptolemaic mosaics in Egypt have been discovered in Alexandria, where the market for such artworks was evidently robust among a particular clientele. Mosaic traditions were, to some extent, carried into other areas of Egypt, predominantly in the Delta and Fayyum regions, where mosaics have been found at sites like Canopus and Thmuis (on and near the Mediterranean coast, respectively) or are attested in the papyrological record (the Fayyum). Papyrological archives provide information about the creation of non-extant mosaics in Ptolemaic Egypt. In the mid-third century BC archive of Zenon, instructions are laid out for the creation of mosaics for the tholoi (circular buildings) of men’s and women’s baths associated with a building—perhaps a wealthy villa—35 in Philadelphia in the Fayyum.36 This papyrus offers a glimpse at the communication that took place between patrons and artists, and the degree of control the patron had over determining a mosaic’s final appearance. Detailed specifications are given for the measurements and design of the mosaics, each of which is to have a single flower at its center surrounded by borders of different kinds. A contractor is charged with ensuring that the mosaics adhere to these blueprints. A model for one of the mosaics is to be sent from Alexandria by royal courier, providing evidence for how this industry was controlled by the court and the ways in which artistic trends in Alexandria were carried into the Ptolemaic chora.37 Several wealthy Greeks who built homes in Philadephia are attested in surviving papyri, and it is possible that they too commissioned mosaics like the ones described in the Zenon papyri.38

As with mosaics, wall paintings in wealthy Ptolemaic homes could be based on types that originated in Alexandria and Alexandrian painters traveled to the chora on commission. Several fragmentary papyri from the Zenon archive discuss woodwork and painting for a large private home belonging to the hypodioketes (a financial official) Diotimos in Philadelphia in the Fayyum.39 Diotimos’ lavish home included multiple banqueting halls—larger versions of the smaller andron in the House of the Rosette. PCairZen 59445 mentions a painter named Theophilos who was hired by Zenon to come from Alexandria and execute paintings in four rooms. He was required to use a model for the painting approved by the homeowner. PCairZenon 59763 names two encaustic painters, Artemidoros and Demetrios, who painted woodwork for the house.

The surviving mosaics and wall paintings found outside the capital were likely also based on models that originated in Alexandrian workshops and were executed by artists based there (Daszewski 1985, pp. 11–12). Some mosaics may even have been physically created in Alexandria and transported to other locations. This type of surface decoration was not only used in the home. Several of the mosaics and at least one wall painting from the chora are known to have decorated Greek-style bath buildings, like the ones discussed in the Zenon archive.40 While these baths were not domestic spaces, they would have served as important centers of communal gathering for the inhabitants of these towns, who could come together for the Greek social ritual of bathing. While the larger tholos baths would have been accessible to all, a smaller type of bath also developed in Ptolemaic Egypt that was likely restricted to certain elite clientele.41

In some instances, mosaics made their way further afield than the Delta or Fayyum, including the mosaic floor in a tholos of a bath building in Karnak that dates to the late-third or early-second century BC (Guimier-Sorbets 2019, p. 16, figure 1.6, p. 19, figure 2.4, pp. 107–8, 123–26, figures 127–132, p. 228 cat. nos. 50–52). The mosaic shows a central rosette with a circular border, but unlike the simple rosette from the House of the Rosette, the flower depicted is a Nelumbo nucifera (Indian lotus), a pink bloom found in Egypt. This building included not only mosaic floors but also wall painting—the entrance vestibule was painted in an architectural zone style.42

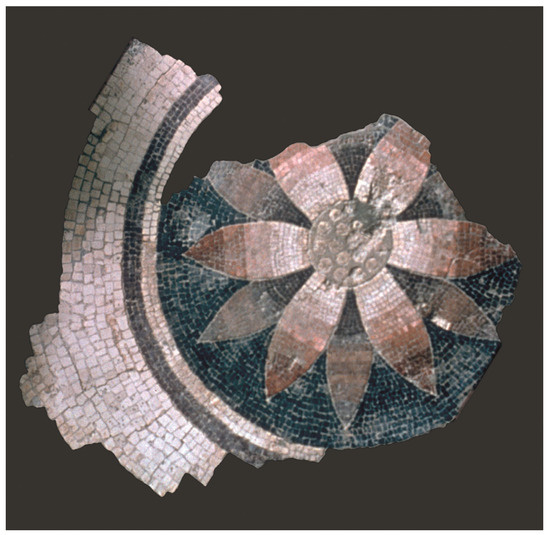

The Nelumbo nucifera also shows up as the central feature in other tholos mosaics in bath buildings, including an example in Diospolis Parva in Upper Egypt, dating to the second or first century BC (Guimier-Sorbets 2019, pp. 107–8, 123–24, figure 126, p. 228 cat. no. 49). Two mosaic fragments dating to the late second or early first century BC were found at Canopus by excavations of the Graeco-Roman Museum in 1916. They show a large rosette, again the Nelumbo nucifera flower (Figure 17) (Daszewski 1985, pp. 135–36 cat. no. 26, Plate 26a; Guimier-Sorbets 2019, pp. 108–09, figure 110, p. 226 cat. no. 43), and a portion of a wave-crest border.43 This rosette is rendered in greater detail than the others mentioned above, with delicate shading of color on each individual petal and a careful depiction of the flower core and stigmas. This mosaic, too, adorned the tholos of a bath.

Figure 17.

Rosette mosaic from Canopus, Egypt. Second century BC. 0.47 × 0.42 m. Alexandria, Greco-Roman Museum, 20860. Photo by R. Ginouvès, ©ArScAn.

Rosette designs in mosaic are found throughout the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, often as the central element of an otherwise simple floor, but their use for tholos floors appears to be unique to Egypt (Guimier-Sorbets and Redon 2017, p. 148). In Karnak, Diospolis Parva, and Canopus the artist went to the effort of carefully illustrating a bloom found in Egypt rather than using a generic rosette, and placed this motif in a setting where it was not typically used. It is very possible that the mosaics commissioned for tholoi in Philadelphia, which each had a flower at their center, also depicted the Nelumbo nucifera. The presence of Egyptian lotus flowers in a space where they would be submerged in water must have evoked a peaceful Nilotic setting for those enjoying the baths. Even a small change like adjusting the species of flower and locating it in a watery environment was a deliberate adjustment of this common motif to make it specifically Egyptian and create a new set of references. As with the use of the andron and associated forms of surface decoration, the presence of bath buildings and their mosaics and wall paintings speak not only to the importation of a Greek architectural form into Egypt but also to the continued practice of its associated social function—bathing—even as it was adapted to a new place. The patrons of such spaces wished to present themselves as having access to Hellenistic trends but also to acknowledge local flora in the buildings’ decoration to create a miniature Nilotic atmosphere. Later, and much more complex, Nilotic mosaic scenes found at Canopus, Thmuis, and (possibly) Middle Egypt show future developments of this theme in the Roman period;44 these scenes likely influenced the popularity of Nilotic scenes in Roman homes in Italy (see, e.g., Barrett 2019, pp. 104–13).

Floor mosaics were thus one major genre of Greek art that altered the visual culture of Egypt under the Ptolemies, as were the physical structures they decorated: dining rooms and baths based on Greek plans. As Alexandria kept pace with mosaic development in the rest of the Hellenistic world, evolving techniques, materials, and trends were carried from capital to chora in Egypt via models and mosaicists like those discussed in the Zenon archive. A similar process must have taken place in the domain of wall painting, but this medium is simply less likely to survive in the archaeological record and so we only see small samples of it.

While the mosaics used in bath buildings tended to rely on geometric or floral motifs, surviving mosaics from the site of Thmuis (Mendes; modern Tell Timai), located south of the Mediterranean coast in the eastern Nile Delta between the Tanitic and Mendesian branches of the river, bear complex figural imagery that convey significant religious and political meaning and may therefore have decorated important public spaces or the homes of elite individuals. Based on what we know from the Zenon archive regarding the communication between artists in Alexandria and patrons in other parts of Egypt, it is very possible that the images on the Thmuis mosaics originated in the capital.

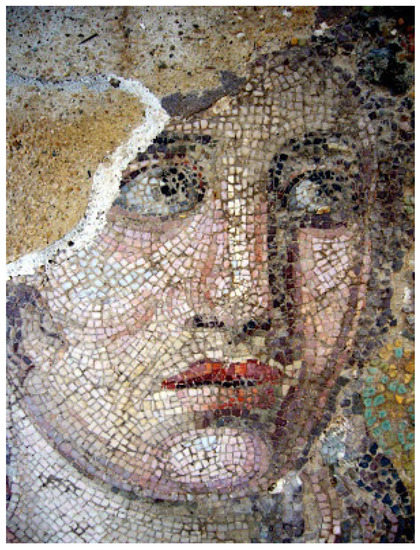

One mosaic from Thmuis in particular has attracted much attention for its enigmatic subject matter, which is not paralleled elsewhere, and for its almost painterly quality. This is often called the Berenike Mosaic of Thmuis. There are in fact two versions of the mosaic, one believed to be an earlier version signed by the artist Sophilos (an otherwise unattested mosaicist) (Figure 18 and Figure 19) and dating to the late third century BC,45 and a later version that is likely a copy of the first (Figure 20).46 The figural panel of the earlier mosaic, if it dates to the late third century BC, would be the first known mosaic executed in opus vermiculatum technique, in which rows of small tesserae follow the contours of each figure.47 Using a far more varied color palette than earlier known mosaics in Alexandria, and incorporating materials like glass and faience, it depicts a wide-eyed woman with a fleshy face who wears a headdress in the form of a ship’s prow. She is dressed in military garb with a round shield at her back and she holds a ship’s mast in the manner of a royal staff. From the staff flow two black and white striped streamers that move in the wind. A cloak is pinned at her right shoulder. In the upper left corner of the scene is the signature ΣOΦΙΛOΣ ΕΠOΙΕΙ (“Sophilos made it”). The scene is surrounded by multiple square border layers of crenellations, meander, and guilloche. The later copy is similar in its depiction of the woman and her costume, but it lacks any signature. Both mosaics are emblema—panels created independently and set into a frame (Guimier-Sorbets 2020b, pp. 59–60). The later mosaic may have been originally square as well but was reassembled as a circular composition, perhaps in antiquity,48 or perhaps when it entered the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria in 1924 (Guimier-Sorbets 2019, pp. 47–48; Guimier-Sorbets 2020b, pp. 58, 64). It is also executed less skillfully than the signed version and is therefore thought to be a copy by a less talented artist.

Figure 18.

Mosaic signed by Sophilos, from Thmuis, Egypt. Late third century BC. 2.77 × 2.61 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 21739. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

Figure 19.

Wider view of Figure 18, showing the geometric borders. Photo courtesy of Kyriakos Savvopoulos.

Figure 20.

Mosaic from Thmuis, Egypt. Late third—early second century BC. 1.44 × 1.44 m. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, 21736. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

The signed mosaic was discovered at Thmuis in 1918 as a chance find, and its precise place of origin is unknown. Although its original context remains unclear, it could very well have decorated the floor of a home or public building in the city. It has been suggested that the mosaic was based on a wall painting from the Ptolemaic court (Daszewski 1985, pp. 88–89, 155; Dunbabin 1999, p. 25; Guimier-Sorbets 2019, p. 45; Guimier-Sorbets 2020b, p. 58), and it is now generally agreed that its subject is a Ptolemaic queen. It was first thought to be a personification of Alexandria,49 but Wiktor Daszewski later argued for it as a portrait of queen Berenike II (ca. 270–221 BC) (Daszewski 1985, pp. 146–58), in which case her costume represented the naval prowess of the Ptolemies in the eastern Mediterranean during the third century BC. A more recent, and compelling, interpretation by Katherine Blouin identifies the figure as an earlier Ptolemaic queen, Arsinoe II (ca. 316–270 BC) (Blouin 2015).50 Arsinoe II had a specific connection to Thmuis, as it was the location of a stela erected in 264 BC, known as the Great Mendes Stela, that established the cult of the deceased Arsinoe II as a goddess in the Egyptian temples.51 The deified Arsinoe was attributed strong naval connections in her role as protector of the Ptolemaic dynasty and in her association with the Greek goddess Aphrodite.52 She stood as an embodiment of Ptolemaic naval power and was the first Ptolemaic queen to be given her own posthumous cult, making her a compelling candidate for this mosaic.53 A small iconographic detail of the woman’s headdress may also be a clue to her identity: the prow of her warship headdress is decorated with a series of icons in two rows, including, to the viewer’s right of the point of the prow in the lower row, what appears to be a double cornucopia (Figure 21).54 On her coinage and on faience vases used in her cult, Arsinoe was shown cradling a double cornucopia in her arms; Berenike, on the other hand, held a single cornucopia.

Figure 21.

Detail of Figure 18, showing the queen’s headdress and possible double cornucopia decorative device in the register at lower left. Photo by A. Pelle, © Archives CEAlex.

The naval costume of the figure would make sense for Arsinoe II, who was known as a protector of the seas. In two epigrams written by the third century BC Macedonian poet Posidippus (AB 36. VI, 10–17 and AB 37. VI, 18–25), he associates Arsinoe with Naukratis (and by extension with naval trade55) and describes her as holding a spear and a shield. Another epigram (AB 39. VI, 30–37) instructs sailors about to embark on sea voyages to pray to Arsinoe Euploia (Arsinoe of the Fair Voyage, one of her epithets) to ask for her protection. These epigrams present Arsinoe as a warrior defending her domain, and as a goddess of seafaring,56 both of which serve to reinforce Ptolemaic imperial ideology.57 Arsinoe II continued to be represented in Ptolemaic art associated with her cult after her death, so the identification of the figure in the mosaic as Arsinoe, who died around 270 BC, does not negate the generally supported date of the late third century BC for its creation.

Whether the mosaics depict Arsinoe II, Berenike II, or some other queen or goddess is impossible to say with absolute certainty. In any case, the images present a strong female figure as a protector at the helm of the empire and they reference the role of queens in the Ptolemaic ruler cult, where they were worshipped by Egyptians and Greeks alike and simultaneously associated with Greek and Egyptian deities. Indeed, the development of the ruler cult was key to the Ptolemies’ strategy of crossing the divide between Greeks and Egyptians and creating an overarching set of beliefs that could unite everyone under their rule. Why might an individual choose such a theme for the decoration of his home (or for a public building) outside of the capital, and why was this theme so popular as to prompt at least one copy—two copies, if we assume that the Sophilos mosaic was itself based on an earlier prototype that came from the Alexandrian court?

The surviving mentions of mosaics and painters in the Zenon papyri confirm that artists and models were sent from Alexandria into the chora to work for men who held high office in the Ptolemaic administration, and that these industries were tied to the court. Assuming that the imagery of these Thmuis mosaics did have its origins in the capital, as seems likely, the mosaics represent the transport of Ptolemaic royal ideology via visual culture into areas of Egypt outside Alexandria. An entirely new body of dynastic imagery was being created at the Ptolemaic court. Artists and patrons employed the media that had been imported from Greece—wall paintings and mosaics—but mobilized it to display images that were uniquely Ptolemaic and that were charged with political and religious meaning. The mosaics were a sort of royal propaganda, but they also served to demonstrate the loyalties of their patrons, who used a Greek medium and style to honor their deified queen. By placing such a mosaic in his home, a patron would declare in no uncertain terms his allegiance to the dynasty. Other high-ranking men whom he might entertain would share the cultural capital and courtly associations necessary to understand the imagery.

7. Comparanda from Priene and Delos

I provide here only two brief points of comparison from the Priene and Delos but there is much more to be explored regarding the Ptolemaic relationship to eastern Mediterranean practices in terms of domestic architecture and interior decoration. One site whose Hellenistic-period homes should be incorporated into future discussions is the island of Rhodes, specifically the city of Rhodos, which certainly played a role in the chain of development of the eastern Mediterranean koine, particularly during the height of its political power and international influence in the fourth to second centuries BC.58 As a major trade center, Rhodes was home to an aristocracy connected to international markets, and the wealthy homes of the island show the same evolution in the use of pebble and later tessellated mosaics, molded stucco, and wall painting. My goal here is to show that we can move beyond focusing only on the Greek origins of certain traditions, which are by now well established and accepted, and also look at how practices in Ptolemaic Egypt were in dialogue with ongoing developments elsewhere, as these forms took on new meanings in parts of the Hellenistic world where East and West were coming into contact more intensively than ever before.

Priene was a coastal Ionian city that was re-founded in the mid-fourth century BC (the city’s original location on Mount Mycale is unknown) and was fully developed after the conquests of Alexander the Great. Although Priene was not an especially large city, it enjoyed economic prosperity during the Hellenistic period and was home to high quality art and architecture.59 Hellenistic homes in Priene’s western and northwestern residential areas were apparently destroyed by fire in the late second century BC. In the northwestern residential area, one house in particular—House No. 33—is especially useful because two distinct building phases can be discerned, reflecting the growing wealth of the homeowner.

House No. 33 began, probably in the third century BC, as a large house centered on a small courtyard without a peristyle.60 At one end of the courtyard was a vestibule area with two columns in-antis. In the second phase of the house, it was joined with the house adjacent to the east and the courtyard was expanded and made into a peristyle. The floor of the courtyard was decorated with marble slabs, and the walls bore sculpted wall stucco decorated with paint. The house contained other fragmentary wall paintings as well. In the northwestern chamber of the second phase of the house, the bottom of the north wall on the western corner of the room contained the remnants of a red stripe with a white band above it, and above that a series of panels in various hues was each framed by red vertical bands (see Rumscheid 1998, pp. 140, 144, figure 127). The rooms in the home’s northeast corner contained fragments of architectural ornaments and the remains of multi-colored zone style painting with vegetal and meander borders (see, e.g., von Weigand and Schrader 1904, pp. 312–13, figures 342–346; Kutbay 1998, p. 87). Evidence for this kind of decoration also comes from other homes in Priene (see von Weigand and Schrader 1904, pp. 308–19). These paintings belong to the same tradition as the zone style paintings from Alexandrian homes.

The island of Delos, which was a major center of maritime trade in the Hellenistic period, contains well known examples of large, lavishly decorated elite peristyle houses—including, for example, the House of the Masks and the House of the Comedians—but also smaller homes closer in scale and layout to those found in Alexandria.61 The archaeological evidence from Delos dates primarily to ca. 130–88 BC (a period known as the Second Athenian Occupation) and is thus slightly later than the Ptolemaic evidence under discussion, but still serves as a useful parallel. As Stella Miller notes, “Delos itself was a major human melting pot where we have the unique advantage of a large body of material remains within a sizable urban footprint of commercial, religious, and entertainment centers supported by city blocks of private dwellings” (Miller 2014, p. 211). The island attracted a diverse population, but their houses adhered to a fairly consistent layout that emphasized rooms used for social entertaining, and a repertoire of zone style wall decoration and floor mosaics that formed a shared elite tradition. A trend that is visible in Delian houses is that, by this later phase of the Hellenistic period, mosaics and wall paintings were no longer restricted to a small selection of spaces and were appearing in other rooms in the home; by this period, such surface decorations were also becoming available to a wider swath of the population. The wealth of archaeological information from Delos, particularly its domestic quarters, provides a framework with which to understand what may have been taking place in Alexandrian homes of the same period, but for which we simply do not have surviving archaeological evidence.

Several houses in Delos demonstrate the modifications that could be made to peristyle homes to accommodate cramped urban environments in Hellenistic cities.62 Indeed, irregular ground plans (as opposed to square or rectangular houses) are common on Delos (Tang 2005, p. 33). House D in the Poseidoniast quarter is reminiscent of House I (from the same cluster as the House of the Rosette) in Alexandria (Chamonard 1924, pp. 439–42; Kutbay 1998, pp. 110, 174, figure 55). It consists of a peristyle courtyard with roughly rectangular rooms on two sides, including an andron entered directly from the courtyard’s east wall. The so-called House by the Lake on Delos is in an unusual quadrilateral shape that requires some of the rooms to deviate from the standard rectangular form, becoming triangles and trapezoids.63 Variations in urban Hellenistic homes were needed to fit the structures into the available space, but they generally followed the same basic principles.

Delos was also home to a large quantity of mosaics and a development parallel with that of Alexandria is visible on that island from the use of pebbles to tesserae for mosaic floors. The corpus from Delos includes some highly sophisticated examples of tessellated mosaics. Philippe Bruneau has pointed out that mosaic styles are consistent among the different groups of patrons found on Delos—communities of Athenians, Italians, and Syro-Phoenicians—and that this has implications for questions of workshops and patronage (Bruneau 1972, pp. 111–17). All of these groups may have commissioned Greek mosaics from a common source, perhaps a workshop outside of Delos. From a social perspective, the similarities in how people of different backgrounds chose to decorate their domestic spaces on Delos illuminates the extent to which certain styles and forms of decoration had likely shed specific cultural associations by this time and were instead recognized as a Mediterranean standard that communicated one’s status and belonging among an elite class.64

Comparisons are possible between the plethora of mosaics from Delos and the much smaller number that survive from Ptolemaic Egypt. The signed Thmuis mosaic can be compared to examples of opus vermiculatum mosaics from Delos. The geometric borders of the Thmuis mosaic—the chain pattern, meander, and crenellations—were all used as border layers in Delian mosaics (see Bruneau 1973, p. 8, figure 5). Indeed, these geometric patterns were common to mosaics throughout the Hellenistic world. The style of the woman’s face in the Thmuis mosaic bears a resemblance to that of Dionysos in a mosaic from the House of Dionysos on Delos that shows the god winged and riding a tiger (Figure 22 and Figure 23) (Bruneau 1972, pp. 289–93 no. 293, figures 247–253, Plate C,1-2; Bruneau 1973, pp. 34–37 no. 21, figures 37–41; Dunbabin 1999, pp. 32–33, figure 33). The two faces have similar wide eyes, broad noses, full lips, and fleshy jawlines. This particular mosaic is among the best examples of the opus vermiculatum technique found on Delos and, like the Thmuis mosaic, it incorporates glass and faience to enhance color variety and amplify shading effects. It is later than the Thmuis mosaic, dating to the end of the second or beginning of the first century BC, and shows a more advanced stage of the technique.

Figure 22.

Mosaic of Dionysos from the House of Dionysos, Delos. Ca. 130–88 BC. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaics_of_Delos#/media/File:Delos_Museum_Mosaik_Dionysos_05.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Figure 23.

Detail of Dionysos mosaic from the House of Dionysos, Delos. Ca. 130–88 BC. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaics_of_Delos#/media/File:Face_of_Dionysos_(detail),_mosaic_of_the_House_of_Dionysos,_Delos,_Greece,_2nd_century_BC.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Some mosaics from Delos combine techniques and use pebbles or large chips to create solid borders, while the figural or geometric decoration is made of much smaller tesserae. One example of this combined technique is a rosette carpet mosaic reminiscent of the one from Alexandria’s House of the Rosette but more elaborate, also from a private home (Figure 24).65 In this case, the mosaic’s outer borders are made up of coarse stone chips, while an interior geometric wave-crest border and multi-colored rosette are made in fine tessellated technique. A similar rosette mosaic surrounded by solid borders and a wave-crest pattern decorated the center of the peristyle courtyard in the aforementioned House by the Lake at Delos (see, e.g., Chamonard 1924, p. 420, figure 247), similar to the rosette and wave-crest border found at Canopus.

Figure 24.

Delos, rosette mosaic. House III N (Theatre Quarter). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosaics_of_Delos#/media/File:Delos_Theaterviertel_21.jpg (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Several examples of figural painted narrative come from Delian homes and, like the mosaics, these date to a later period (ca. 180–33 BC) than the third century BC Alexandrian examples discussed above, but they are related to the same traditions.66 Given the general lack of surviving paintings from domestic contexts in the Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean, the examples from Delos can serve as a model to understand painting trends that are now lost in other locations. Many of the figural paintings from Delos were incorporated into upper registers above architectural zone style paintings.67 A painted wall from the House of the Comedians, for instance, shows the incorporation of a figural frieze into a zone style painted wall (Bruneau et al. 1996, p. 73). Many of the painted figural scenes from Delos bear a close similarity to the paintings from Alexandrian tombs in terms of overall style, and both can be traced back to the common ancestor of Macedonian wall painting, which only survives in funerary contexts. Vincent Bruno has suggested (as Bruneau did with regard to mosaics) that the quality of Delian figural painting is so high as to indicate that the artists were brought in from a more central location with a major painter’s workshop, as such a high level of training might not have been available on Delos.68 This kind of mobility of artists would require a system of patronage not unlike that which we see in the Zenon papyri, in which most artists are operating out of a centralized location and are employed on a temporary basis by wealthy patrons. The examples from Alexandrian tombs and the households of Priene and Delos reflect the kind of painted decoration that may have been found in Alexandrian homes.69

As in the case of Alexandrian artists being sent out to the chora to execute mosaics, artists in other parts of the Hellenistic Mediterranean were highly mobile and were employed by wealthy patrons who wished to participate in the shared practices of other elites. This could sometimes result in inconsistent quality, depending on which artists an individual had access to at a given time. Nevertheless, the style was derived from Greek artistic traditions and underwent similar developments in different Hellenistic centers, leading the mosaics and paintings found in elite homes to all share similar characteristics.

8. Conclusions

The above examples of room types, architectural features, mosaics, and wall paintings, when considered together, hint at the overall appearance of the elite homes in Ptolemaic Alexandria and, to some extent, in the chora. Certain spaces characteristic of Greek domestic architecture were evidently considered particularly important, and it is no surprise that those were the rooms associated with receiving guests and entertaining. Because these were the most visited spaces of the house, they were also the most important for visually communicating the identity of the owner. Outside the home but related to communal practices were the Greek-style bath buildings found throughout Egypt, which also received the same types of surface decoration. We can visually track the different identities and allegiances that Ptolemaic elites expressed through the visual culture of their homes and the public spaces they used. There is fertile ground for future research on this subject.

The first generation of Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt were invested in retaining a connection to their places of origin, which were largely located in northern Greece, and perhaps brought Greek traditions with them primarily to project Greek identity and an affiliation with the new rulers. With time and increasing cross-cultural exchange and intermarriage, however, those traditions came to be more strongly representative of elite status in general, and they became somewhat disengaged from Greekness specifically. As the world grew ever larger in their view over the course of the Hellenistic period, which was characterized by greater mobility in every sense (economic, social, physical) and the growth of major cosmopolitan centers, Ptolemaic elites sought to engage with what was happening across the Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean. At the same time that they were part of this larger Hellenistic world, they inhabited a specific place with its own strong heritage, where Greek and Egyptian interacted and where a dynasty formed its own hybridizing identity. This situation required particular efforts at identity maneuvering. Ptolemaic elites made use of the same media, styles, and techniques seen elsewhere in the Hellenistic world but they increasingly employed them to convey meanings that were exclusive to their own experience living in Egypt under Ptolemaic rule.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper began, several years ago, as a chapter of my doctoral dissertation at Yale University, which explored visual culture and elite identity in Ptolemaic Egypt across various physical settings including temples, tombs, homes, and public spaces. I am grateful to the volume editors for providing me with an opportunity to revisit the subject of domestic spaces. The ideas I lay out in this essay are only a small starting point for research that might be done on elite identity and Greco-Egyptian hybridization in Ptolemaic households. I would like to thank Marie-Dominique Nenna, Director of the Centre d’Études Alexandrines, and Kyriakos Savvopoulos for providing illustrations. I would also like to thank the volume editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The only monograph dedicated to Ptolemaic homes is Nowicka (1969), but much archaeological material has come to light since its publication. For other studies on Ptolemaic and Roman households in Egypt, see the essays in (Ballet 2012). For Alexandria specifically, see also (McKenzie 2007, pp. 66–71). Abdelwahed (2016) discusses the architecture of Roman homes in Egypt and the various ritual and social activities that took place in the home. For Graeco-Roman architectural terminology in the papyrological record, see (Husson 1983). |

| 2 | On Greco-Egyptian hybridization in Ptolemaic tombs, see, e.g., (Cole 2019a). On elite self-presentation in Egyptian temples via the use of Hellenistic honorific statuary, see, e.g., (Cole 2019b). |

| 3 | On this issue and for a general critique of “hybridity,” see, e.g., (Silliman 2015). |

| 4 | Barrett (2019), for instance, deploys these concepts in her study of Nilotic scenes in Roman domestic gardens, but in that case the Romans’ act of appropriating imagery from another culture and place and giving it new meaning fits better into Stockhammer’s framework. |

| 5 | As a starting point, see, e.g., (Dunbabin 1999; Andreae 2003) on mosaics; and the essays in (Pollitt 2014) on wall paintings. For wall paintings and mosaics in Ptolemaic Egypt specifically, see the works by Guimier-Sorbets cited throughout this essay. |

| 6 | See the discussion in Nowicka (1969, pp. 105–29). |

| 7 | Badawy (1966, p. 28). For houses at Amarna, see (Kemp 1977; Spence 2015). |

| 8 | On the economic status of Amarna residents, see also (Tietze 1985, 1986). |