1. Parasomnia: A Circuit of Seven Places

The article comprises nine sections: first a personal account of the seven Places of the performance is presented, then follows a brief exposition of sleep regarding social developments in a capitalised market; after that, it considers what senses may be awakened in each Place. Then, key concepts suggested by the performance experiencing are discussed, and finally it is advocated that sleep appears to be in contrast with productivity in contemporary societies. Performing arts emphasise the importance of being present and vulnerable, this is, being able to feel and to process our own thoughts and emotions. Experiencing time passing will give us a sense of our interiority in relation to Earth cycles and historicity. For that Parasomnia utilizes audio-visual media that lays on and shows a fantasmatic dimension, mirrored in these resources and resonating with our human subjectivity—both in relation to oneself and to alterity.

This piece incites our bodies to slow down the speed, to have a halt to a continuous consumption and therefore positing sleep as a political antidote to capitalist assault.

Parasomnia1 is a participatory, sensorial, site-specific performance, comprising themed scenes in different areas both inside but mainly outside of the building Mãe d’Água das Amoreiras Reservoir in Lisbon, Portugal, commissioned by Teatro do Bairro Alto. The Reservoir, classified as a National Monument, houses the Water Museum, and was concluded in 1834. Finished in a baroque and neoclassical styles, it has sober architectural lines that enhance its scenographic atmosphere. Its terrace comprises several corners and allows for a vast view over Lisbon

2.

Parasomnia is directed by Patrícia Portela (PT/BE), an interdisciplinary artist who associates the performing arts with several media, and it hybridizes performance, installation, theatre, storytelling, visual arts, gastronomy, and hygiene in seven moments of solitude and group situations. Below there is a personal account and description of my experience navigating though the performance.

(a)

Place of Waiting: In the entrance room of the Reservoir there is a projection of mixed paintings in very slow motion. Spectators are served a warm tea while contemplating the image, the sound ambience, and the room itself. Everything happens in a slow manner (refer to

Figure 1).

(b)

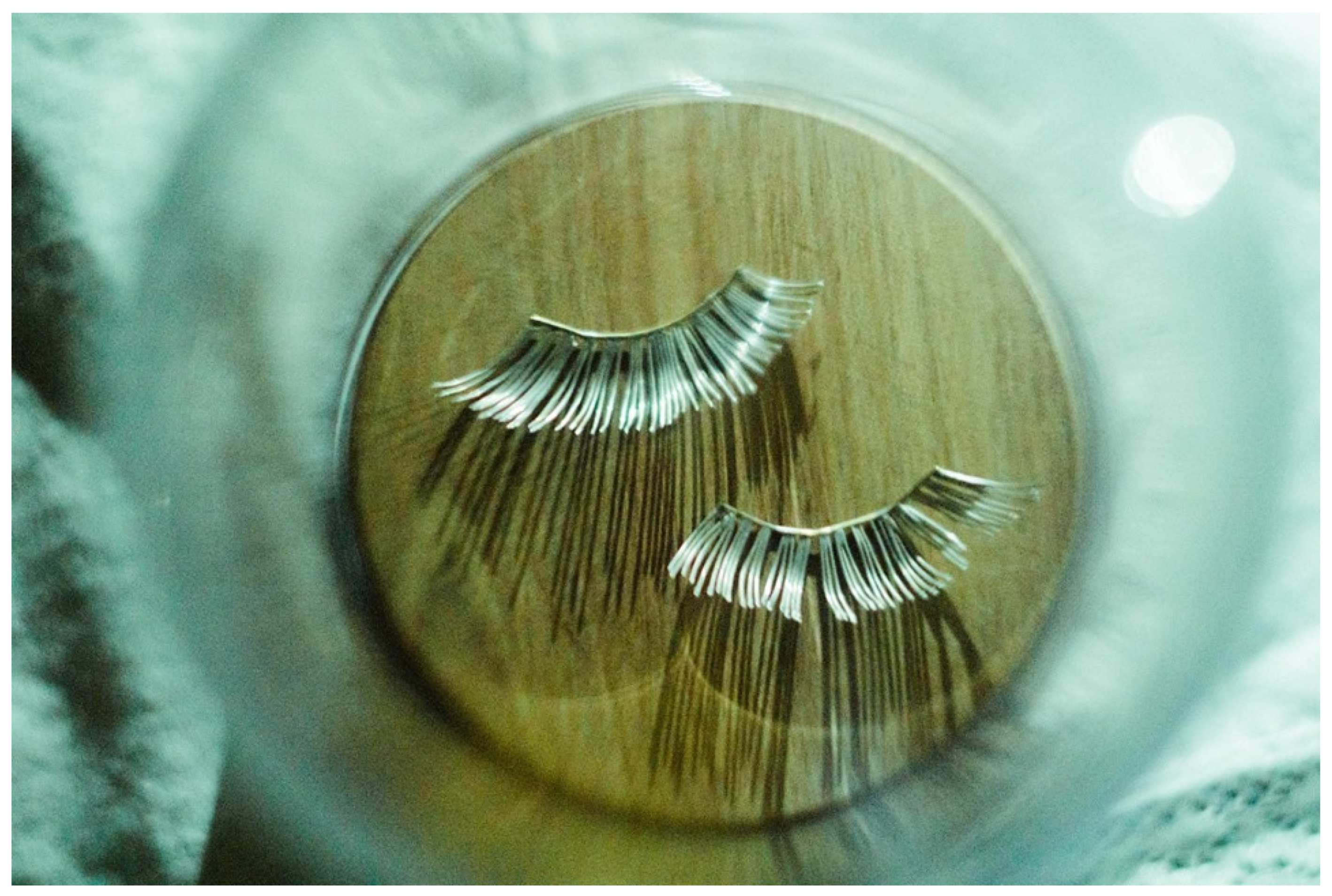

Place of Pleasures: After a flight of stairs there is a middle area before the outside garden where jewellery is shown: an intimate male brush, a female pleasure enhancer, and silver eyelashes for the insomniac. These are recreations of Acácio Nobre

3 objects used to give pleasure and induce sleepiness (refer to

Figure 2).

(c)

Place of Milky Way: A video projection created out of the painting

The Origin of the Milky Way4 depicts the mythological scene when Zeus tries to make his infant son, Hercules, immortal by being breastfed by the goddess Juno while she is asleep. Suddenly she wakes up, the milk spurs thus forming the Milky Way and Hercules does not achieve immortality. While the picture slowly moves, Portela, as a performer now, tells this narrative embedded in other stories; namely why the bottom missing part was cut out of the painting. Portela speculates that the painting was a wedding present from the Emperor Rudolph II to his wife. Hung by their bed, his wife could not sleep because the soil at the bottom of the painting was dropping on her, so that part was cut. That night she slept wonderfully but the two of them could never sleep in that bed again nor together (refer to

Figure 3).

(d)

Place of Sleep: The spectator can lay down in one of three hammocks with coupled speakers telling stories and side stories about two lovers, one of them dying. The narrator’s voice one hears is a Portuguese woman (refer to

Figure 4).

(e)

Place of Supper: Near the central square of the garden, sweet delicacies are served: a bonbon called ‘sleeping pill’ and a puree named ‘cherry sins’ (refer to

Figure 5).

(f)

Place of Bath: In the central square, a performer prepares a wooden bathtub, cleaning it and filling it with warm water. The audience is sitting in front and observes the action. Then the first performer (a caregiver) leads a second performer (the receiver) to the bathtub. The carer massages the receiver’s legs and feet with an unguent of oils and salts, and finally helps the cared one get out of the tub. Afterwards, the first performer asked the audience if anyone desired a bath, and I offered myself (refer to

Figure 6).

(g)

Place of Lulling: In a hidden area of the garden, there are carpets on the floor for the spectator to lay down, together with a wooden pillow and a speaker lulling a medley of calming songs sung by a Brazilian male voice (refer to

Figure 7).

Like a gift, each Place is an invitation to the spectator. In between these scenes, spectators can enjoy the cold of the air, the stars above, maybe have a little chat, although the ambience respects quiet. At the same time, the spectator can experience some sensation of being adrift, wondering what comes next or while waiting for turns at each Place. Every now and then, we can see the performers—all but the chef of the delicacies are women—wearing long garments, talking in a smooth, comforting manner, and guiding you through. When the performance ends the spectator is intensified and invigored, while at the same time peaceful.

Patrícia Portela, the artist behind the performance, divides her focus between several activities

5: literature, performance, visual arts, teaching, and curating, and she is also a columnist for newspapers and radio. Within the surprising universes conceived by the artist, the feature to expect is a is a wide-ranging geometry of practice comprising both works in her own name and as part of a collective—Prado.

Sleep is a form of resistance against capitalisation of lives. As a biological imperative, such a resistance comes from the body itself. Parasomnia shows how we can prepare a state of somnolence to enter new areas of the subjectivity.

In a state of vulnerability, the sleeping individual can experience the day cyclicity (suggesting as well different types of life cycles) and distinct temporalities (differentiating past, present, and future), and confronting oneself with a fantasmatic dimension, whose mediatic apparatuses in Parasomnia are enhanced.

Sleep consists of the loss of rationality and of productivity, meaning that the subject is not in its full consciousness, which allows forms of otherness to appear. Furthermore, sleep is goalless so that one does not have to achieve any target and in fact the productivity capitalist mechanisms do not apply, giving us permission for a halt.

2. Sleep as a Gesture of Resistance

This paper sets out to address the relation between arts and social change, one prompting another. Parasomnia, a medical term for sleep disorders, becomes part of an aesthetic fabrication. As such, sleep becomes a site of resistance against the contemporary 24/7 compulsion to always being on: connected to technologies, to social media, producing and buying, proactive, and chasing goals. In sum, sleep fosters a gesture of subversion in late capitalism before becoming colonized by neoliberal regimes. In fact, I make the assumption that we cannot hide from a continuum of tensions between daily life and aesthetic dimensions (

Rancière 2004) intertwined with performance in a political-cultural framing. The way we make art and the way we perform in ordinary contexts activate each other and produce meaning.

As for the contemporary questioning of sleep, we can place its inception in

Melbin (

1987), who addresses night as a frontier that is broken, broken in the expansion of the activity of being awake to the extent that the dark hours have been colonized by electrical devices and its subsequent lifestyles in contrast to preindustrial eras (

Ekirch 2005).

In fact, the advances in production and consumption, as well as a thoroughly mediatized environment, have transformed the labour-force into a new and dynamic social structure, where capital assumes elusive and changing forms. Therefore, up until the present, capitalism has evolved into becoming ‘cognitive capitalism’ (

Fumagalli et al. 2019). It is so called because it posits intellectual, cerebral labour, as well as cognitive and emotional qualities. This form of cerebral labour becomes itself the product formed by digital information networking (

Boutang 2011). Cognitive capitalism entails that the capital from which profit is extracted is now human immaterial capabilities and no longer physical strength and manual skills as before.

In the big picture (

De Boever and Neidich 2013;

Neidich 2014,

2017;

Fisher 2009), these new forms of invasion and settling, accumulate into a growing biopolitics, an imposition according to which feelings, attitudes, and biological states are an asset to manipulate, monitor, and control. It is a vicious cycle, like a fish that bites its own tail. It occurs in an emotional market where ‘emotional’ points to two aspects: (1) taking advantage of emotions—in order to buy and sell and (2) ‘emotional’ referring an unstable and always changing market, oriented to produce, profit, and capitalise from human cognitive experiences.

Sleep resides in an ambivalence. It is not only biological but also cultural. Therefore, it has the potential to be a ground for specific markets: pharmacological products, clinical treatments, self-help books, and so on. All these situations transform sleep and sleeping problems in a specific biocapital market. However, without these controlling mechanisms (being medicines, therapies or promising new lifestyles), sleep per se, at its base, exists outside tools of productivity and vigilance.

Let us contrast the Parasomnia performance program with the art critic and essayist, Jonathan Crary’s observations below:

Parasomnia spreads in various rooms promoting the stimulation of melatonin and the appropriate vapours of somnolence for the induction of sleep and the practice of lucid dreams. An invitation to the slowing down of our bodies during the daily rhythm of our working days.

Parasomnia Performance Program

“24/7 is a time of indifference, against which the fragility of human life is increasingly inadequate and within which sleep has no necessity and inevitability”.

24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep.

In brief the performance lauds unproductiveness and the state of somnolence, inviting the visitor to inhabit several spaces in order to create a relaxing mood as a way to embrace sleepiness and vulnerability.

3. Bodily Senses and Sensibilities

Having as departure point “the performative power of the senses” (

Banes and Lepecki 2007, p. 3), the body can enact a wide range of somaesthetics (

Shusterman 1999,

2012) where the body, the flesh, the perception, and the sensorium are key to grasp further possibilities.

One of the prime aspects Parasomnia teaches us is that the gates to sleep are opened in the body. Often despised to a second level, body and sensibility need to be stimulated in a certain way to reach somnolence and other capabilities.

In

Parasomnia, to stimulate means to learn how to listen and to offer oneself up to listening, to learn how to taste and be given to taste, to learn how to touch and be touched, to learn to see and be seen, in a back and forth of affections traversing performers, spectator-visitors, and scenes, uncovering other textures besides rational and material worlds. Senses are as such the first experiential and semiotic substances or as

Banes and Lepecki (

2007, p. 4) put it: the body is “an inexhaustible inventor of sensorial-perceptual potentials and becomings”.

However, that same experiential matter can also be found beyond, that is, towards an immateriality that relates to the concepts (and practices) addressed in this paper, i.e., vulnerability, temporality, fantasmatic, and subjectivity.

Sipping a tea in the Place of Waiting, we refine our taste and we train ourselves to extend time and to give ourselves over to the slow-motion projection that faces us. Before the entrance to the upper areas, before accessing greater things and wonders, one has to know how to wait, how to accept that moment: one has to stay—and, actually, to trust.

Awaiting also takes a part in the image projected, as it moves slowly, resembling the moment we wait for sleep to come, as a first stage of drowsiness. If we resist that drowsiness, this slow time, somnolence does not warm us; on the other hand, if we resist through the extended duration of the changing image, only then will we be able to take in this mutation.

In the Place of Pleasures, the imagination is awakened. Those objects are there to be seen, not used in that moment. Pleasure is beyond the physical and actual, it is postponed. It is a suggestion of joy; pleasure is detained.

Eventually, we enter the upper floor outside. An entrance, that we inherently know is also an exit, comes to mean a communication between being wake and being asleep, between the senses and the mind, between consciousness and the unconscious, if we may understand it in a psychological sense. In fact, in my experience as a spectator, given that there is not any specific order to when to visit each Place, I faced some uncertainty, dizziness. As in sleep, I was reaching a territory.

That territory starts with the Milky Way, projected onto the building and continuing to the skies. The visitor watches the small narrative of Hercules inside a bigger narrative that explains a piece of our place in the universe. By listening to Portela’s embedded stories our imagination is fired.

The hammocks in the Place of Sleep raise us above the ground: I am part of the air. Wrapped in a fabric and lightly waving, I am lulled by a crystalline voice. By contrast, in Place of Lulling I lay completely on the stiffness of the ground, and my body becomes earthly. From outside in, in Place of Supper, I experience combined flavours; my mouth and my body will assimilate a gift gesture.

The idea of losing oneself takes shape in the Place of Bath. Being taken care of is a present given to the audience. To me, individually. I am offered a ritual: after changing from everyday clothing, I am guided to the wooden tub. It gives the impression that time is suspended, that space and time move back to another temporality, not only historically but also in perception. I am taken care of because I am important, this is what the situation tells me. Like a prince/ss, like a child, a person is here to look after me, I am here to be pampered in a non-judgmental, but loving manner.

This immersion within senses comes from the body, preparing it to accommodate a state of vulnerability.

4. Vulnerability

Lying there in the bathtub is a state of vulnerability (

Brown 2012;

Clement 2014) as if I might either be killed or nursed. Accepting to be touched—a passive/receptive condition—is a forbidden behaviour. Often in everyday life we are not able to touch other people, or only with great caution. Often in the speed of the everyday, we do not have the time or presence to get into contact with other bodies, especially in a lasting, moving interaction, the opposite of handshaking or a light slap on somebody’s shoulder.

The immersion and participatory dimension in

Parasomnia means direct experience, and experiencing lends itself to vulnerability. Being vulnerable implies one can be invaded by what happens, instead of remaining in a fixed condition—both mentally and physically

6.

Capitalism’s focus on productivity means that we cannot be vulnerable, we must have control: of ourselves, of our belongings, of our tasks and affairs—we cannot move out of a regime of control. We are taught to think that we must be in control. But actually, we can only have a degree of control, because millions of things can happen differently from what we might have predicted or expected.

Vulnerability is not only an acceptance, a mechanism for being out of control. It is also a means to being able to stop; to pause, to allow ourselves to be interrupted, to just be. So it starts as a decision and it manifests out of a behaviour. It means to enjoy a sense of liberty over and above whatever an individual must accomplish, despite whatever is. In concrete terms, this performance teaches us, invites us to be fed, to be given a bath, to be told stories that may not make absolute material sense.

It means being stripped of a rationalizing and controlling mindset. At least for a moment, I am not in charge. I can be taken care of. And for that I can be very present here, and have no anxiety for what will be, no over-analysing past deeds (or at least to a lesser degree of intensity).

In Parasomnia, the video projections we watch and sound ambience we hear invite us to contemplate: not doing, not achieving, not producing, not accomplishing. Therefore, vulnerability unfolds into a capacity towards the self, but also towards the whole surroundings like an open antenna that pays heed to details and to distant universes. Surpassing the supposed passivity, vulnerability becomes an active listening, awakening sensorial processes, and mental and emotional connections. I am in myself and as such in time and place.

Susceptible to time and place, we can be weak, but that weakness becomes a capacity to transform (

Brown 2012), to act. As a condition to change, we can be hurt, nurtured, endured, or transformed. Or all at once. Hence, vulnerability turns out to be a strength: expanding one’s limits and worldviews while confronting fears and pre-established borders.

Similarly, sleep is a state of fragility. For that fragility it is necessary to fall asleep, to fall into the sleep—as Jean-Luc

Nancy (

2009, pp. 1–4) puts it. Because we need to slow down our state of alertness and allow ourselves to fall into the pleasure and the pain. Slowing down permits a different perception in time recentring our consciousness.

5. Temporality

The performers’ slow manner and the slow projections that the audience sees are a different exercise in time. The opposite to a fast-changing schedule of the everyday, or to navigating a digital environment, we are induced to slow down.

The contemporary speed of capitalism implies a continuous activation by stimuli. Individuals are always connected, always plugged in, always on: connected to devices, the internet, and into systems. In a way, humans become like forms of electricity.

The continuous continuity in an everlasting present

7 leads to an annihilation of Time: so the past is forgotten, and so are its social struggles and affirmations; so the future is on hold, and achievements that are to come are replaced by clicks and by endless presentness. By being present I do not mean the state of being in time and space, but the disintegration of time and space (

Virilio 1995;

Castells 2000). This kind of presentness implies only the pragmatic, the schedule, the achievement that is already forgotten and replaced by the next one. It is to only live in the immediate. Such presentness is well represented by our handheld devices that control and implode the timeline and, hence, temporality. As

Crary (

2013, p. 45) points out, the acceleration of new technological novelties leads to an erasure of “historical knowledge”.

Time seems to be in the process of disappearing towards an aimlessness (

Han 2016). Actually, we no longer see the hands moving in a watch, all becoming numerical and dematerialized. The obliteration of time makes void all (human) experience and history.

Parallel to the conquering of the space and distance

8 via communication systems, roads and transportation, videocall software and airplane traffic, the neoliberal regime is colonizing Time, and timelines tend to disappear. The erasure of time results in the ceasing of aging (

Baudrillard 1998). People will no longer get old, or so it seems. Playfully put, presentness is like eternal youth and therefore wrinkles disappear via Photoshop. It is as if being ‘human’ could only mean being young—with all its implications for not being capable of adapting to change. This is not arguing against a so-called ‘youth culture’ but arguing for a culture that includes all age groups, and therefore all temporalities.

It is precisely a timeline, a moving timeline, that we can see in the

Place of Waiting, in the form of a video projection. The screen shows a body: that was born, literally, in a bed, that lives and will die in a bed. Despite this, the effect of eternal present—more than a deferral of death (

Baudrillard 1998;

Sedlmayr 2017)—seems to abolish death, and life itself will vanish with death.

6. Cycles and Rhythms

Cycles of time (

Adam 2006;

Stross 1999;

Fabian 2003;

Madeira 2012), life, and death disintegrate. The experience and perception of time passing by become shattered. Life and experience never stop—the sciences and humanities, not to mention common sense, tell us this. A flux of interrelations criss-crosses other geometries of worldviews and ambivalences. That said the fundamental aporia here is that activity and productivity have interruptions, at least in relation to cycles. Actually, it could be argued that interruptions are the real enabling aspect of that renewed cyclicity.

Day and night, seasons, agriculture, childhood and adulthood, reproductive age and transitions, and a myriad of other phases represent rhythm while balancing polarities and allowing for the existence of species and sociabilities. Likewise, in written or oral form, a syllable has a cycle (onset, nucleus, and coda—cf.

Ladefoged 2001), and even Earth sedimentary layers have interruptions (

Selley et al. 2005). In simple terms, sleep is therefore the pause between a day and the next one. However, it encompasses another universe of its own. The pause not only provides a break as well as an invigoration, it also makes possible a transformation.

In Parasomnia, besides the slow-paced atmosphere that pervades from the entrance room, the spectator can sense a rhythmicity in both video projections and from one Place to another. In addition, s/he can admire a historicity discerned in the artifacts we can vaguely attribute to a mystical period somewhere between the XIX or beginning of XX centuries (Acácio Nobre collection, Place of Pleasures). One can observe an ancient historicity in the paintings used for the video projection (Ancient Greece is depicted alongside medieval motives of death and angelic figures); and even the Reservoir building imposes its history. Food also has a rhythm: when we have meals and when we do not, the time preparing it, the order and manner in which ingredients are mixed and cooked, and the time for digestion.

Lastly, in the projections, there are rhythms of historicity as eras pass by before our open eyes, confronting us with it in our present time, a dimension brought up as ‘transhistorical’ by

Arrais (

2017, p. 32) in his essay about Portela’s performative work.

Interruption, as a disruption from incessant production and consumption, results in spaces of division between leisure and work. Time never stops, but cycles can produce blocks of a different nature allowing the individual or groups to have recreational time, away from regular activity, procedures, and ways of connecting.

Sleep, rest, or restoration—not just a simple break—comprises its own sphere, if only we are allowed such an interruption, if frenetic continuity grants us free time.

7. Fantasmatic

A whole universe can emerge: unknow, frightening, potential, and itself singular. When we sleep, when we dream, eyes closed or open, the fantasmatic arises. Discontinuity opens up a gap. A gap initiated in our senses, with delicious bonbons and a relaxing bath by the moonlight, finetunes our modes of attention for increased perception. Such a gap becomes a single point of entrance, or an irruption, a state of inner availability that solicits the imaginary. So many images we have in our mind, so many possibilities that flash through our mind and senses. By being in contact, inside and outside, we create, and we carry lives and interests and evocations that consist of one’s imagination.

Fantasmatic, deepening the “return of the dead” (

Barthes 1993, p. 3) as a productive trope, denotes the imaginary, the immateriality as well as driving desire and in-betweenness.

9In this regard, Jonathan

Crary (

2013, p. 100) says, “one is obliged to construct fantasmatic compatibilities between human and a realm of choices that is fundamentally unlivable” (referring to the relations between biological nature and the “mechanosphere of global capitalism” (

ibidem)). The unique sphere, the inner voices and images that inhabit each one of us were gained, not by our fantasies and hopes but by colonizing imagery originated in advertisements, social media, and a continuous virtual stream of information.

Fighting fire with fire, Portela’s use of digitally edited images from paintings shows that virtuality may reengage us in a self-somnolence. These videos trigger the oneiric, impermanence, and the transitory. They are like the moving waters that

Nancy (

2009, p. 39) alludes to; these projections fade away into each one, into each one’s fantasmatics.

10In fact, by using digital imagery,

Parasomnia intends to win back that imaginary space, full of phantoms, urges, and identities recovering the need for a non-digital imaginary and, as such, for an inner time. In a first instance, the fantasmatic lies in the videos that, in a second instance, returns to where it has always been—ourselves.

11On this account, Julia

Kristeva (

1995, pp. 10–13), articulates that access to the fantasmatic problematizes inner experience while allowing for redemption. Similarly, the Butoh master Kazuo Ohno argues for the capacity to accommodate phantoms as a way to create spaces of existence. Elaborating on the “dance of the dead”, the author posits “We grow after the grace of the dead” (

Ohno 2016, pp. 131–32)

12 so that each individual gathers and contains several (absent) ones.

Fantasmatic relates to the ability to operate with the non-existent, and therefore with the imagination, associating one absence with another and thus fabulating

13. Contemporary daily life can steal our capacity to fiction. Leaving our mind to our imagination can be a countermeasure to nurture us. An inner storytelling, relating the self to images, undigested sentiments, and daily traces, makes out a personal narrative, a group frame, capturing experiences of time, space, and identities. Or as

Crary (

2013, p. 127) suggests, it is when we operate a “metabolization of what is ingested during the day”, whether alcohol or illuminated screens.

The fantasmatic, or the ghostly figure, taking advantage from spectrality studies (

Blanco and Peeren 2013), has the ability to reframe and recontextualize occurrences and episodes. Spectre, in its etymology related to vision (visibility and invisibility), conveys a possibility to look at something attentively (perhaps at the non-visible too), and by doing so there is the space to reinterpret the wound so it may be healed dynamically, both in the case of personal and historical traumas.

Whether decoded or not, a haunting force could release renewed forms of presenting and acknowledging subjectivity and alterity. The phantom troupe is in fact a powerful metaphor even for political theory fields. In Parasomnia, slow visualization of a person’s life as in the Place of Waiting, from birth to death, may inflate critical thinking of what occurs in between both, emphasizing action and will, paradoxically while the spectator just sits and contemplates.

Our fantasmatic, projected in the videos, can fabulate, like when we sleep, or when we are about to fall asleep. Stories interconnected with each other, the imaginary, the real, and the perceived, reminiscent of a personal Shahrazad, make up the smooth atmosphere when the spectator eventually leaves the Reservoir.

8. Subjectivity

The dimensions discussed above embrace the subjectivity that sleep can enable. On this matter, the philosopher and art theorist Alexei

Penzin (

2015) formulates that when I sleep, my rational subjectivity is somehow deactivated and, paradoxically, can be considered as a ground for subjectivation, and therefore a specific kind of “ontological ‘insomnia’” (

Penzin 2012, p. 11).

As I am absent from rules and from the real world, not only am I useless (to the State and to capital), reason and conscious also do not apply for that period. During the awaking day, the individual is saturated with capitalist forms of communication. While sleeping there is a loss of the rational order, a process of getting into a complete interiority, ‘absolute power’ in Hegelian terms, and where the subject is absent of late capitalism’s controlling mechanisms.

The power of potentiality as a place where we can rest, restore energy, and not keep going, consists of a pause for the self, in the self. A place where one can alleviate and interrupt bombardment of the everyday. This interval, while dreaming, while sleeping, sums up my several Is, so I can exercise my immense, unfathomable subjectivity. Deepening potentiality and creativity towards awareness, Penzin states:

“Sleep functions as a condition of suspension and inactivity, necessary for the production of work, or as a teleology of the revolutionary awakening of individuals and collectives” (

Penzin 2012, p. 12).

Curiously enough, sleeping is finding inside ourselves the other I that is made of pieces of my individuality and whatever fragments I may have collected or may have been offered or addressed to me. It is a process of alterity, a kind of otherness that I can find in myself but that is different from me: the dreaming I-other. Therefore, this first alterity has a paradigmatic importance: opening several spaces for otherness that are to come.

Jean-Luc

Nancy (

2009, p. 7) states, “more than anything, I myself become indistinct. I no longer properly distinguish myself from the world or from others, from my own body or from my mind, either”. The individual, then, becomes unmarked, amorphous with the world. Being asleep, in the first instance, is a deep dive into my subjectivity. It will actually emerge and put me in contact with and within the world.

In fact,

Nancy (

2009, pp. 14–15) associates the

I with the ideas of wakefulness, daytime, light, and vigilance, and the self with the power of potentiality. The

I loses itself in sleep, loses itself in the falling into sleep. As such, the

I then enters the self, the selfness indistinct from the rest, without a clear distinction between

I and you.

Sleep is thus both personal and impersonal, individual and collective. I sleep with, on, to, for, below, and above me. I do it on my own terms and rituals. However, every person and every animal sleeps. We do have that in common. When night comes, we can argue, even buildings and mountains fall into their own sleep. In fact, whether it is night or day, human or animal, the collapse, the abandonment has the same origin and goes towards the same destination.

Whatever the time (or the geography), there is a point when tiredness and boredom take control. “Nightfall inside the sleeper” (

Nancy 2009, p. 6) surrounds the individual, the group, the city, the countryside, the species, the monuments, the thoughts, to produce an aggregate, a whole and its parts. So it pertains only to me, as it is my sleep, my subjectivity, my vulnerability, but it aligns me with every being. This equal inscription, one can argue, has an ecological and ontological unity. “Sleep itself knows only equality, the measure common to all, which allows no differences or disparities” affirms

Nancy (

2009, p. 17). Sleep can be consequently an ethical exercise as

I melt into self, into the living, into the world.

9. Productivity

As we can see both sleep and wakefulness have cultural, social, philosophical, and political dimensions (

Penzin 2015). In a way, as contemporary individuals, we are 24/7 compelled to produce, consume, and continue the vicious cycle of productivity. Capitalist societies advocate that one must have goals and those are committed to outputs and efficiency in every moment and dimension of our lives, habits, and concerns, in a thoroughly and rather unconscious manner.

Even in leisure time, after gaining an honest wage, we follow the same routines. We may have different objectives, but such a scheme appears to be mandatory: to feed a presence with our own selves. Productivity is a loop into which capitalism pushes us where “time itself became monetized” (

Crary 2013, p. 71).

Even our own personal valorisation and self-fulfilment is dependent on consumerism and efficiency. Experience has been merchandised as a product (

Fisher 2009), whether in the form of vacations, yoga retreats, or a marathon against breast cancer. The “standardization of experience (…) on such a large scale entails a loss of subjective identity and singularity” elaborates

Crary (

2013, p. 49) leading to a deficit in creativity. Following that, there comes a compulsion to achieve, and to report, posting and retweeting.

Abandoning our capacity to predict behaviours, quality sleep might in fact be a beginning to undermine the whole colonization we have undergone as human beings. A beginning might be to create an artistic performance and our own performance of sleep in order to fabulate and awaken our senses.

10. Conclusive Remarks

Some days ago, while I was writing this paper late at night, my mother texted me saying, “we have to give sleep a rest”. In a single manner, these words reveal that we are exhausting sleep the same way we are exhausting bodies, sensibilities, and reason.

Parasomnia recalls activities such as caring, nurturing, feeding, bathing, contemplating as a way to remember slowing down, experiencing rhythms, realizing and seizing time and bodily senses, and—in a way—embracing death, and thus life. Human constitution that relates to this vulnerability means the capacity to transform, individually or collectively. Cycles are part both of nature and human culture and those are in reality the enabling factor that propels continuity and efficiency. Nevertheless, the perception of time passing, of different ages and eras impact on the historical knowledge, without annihilating Time itself.

Portela’s performance, by inviting the spectator-visitor to inhabit these Places and allowing time to be there, paves the way to an inner meditation for fabulation, an action, rather than passivity, that transforms itself into an agency towards the self in several dimensions. Such inner storytelling, recompiling the imaginary, anxieties, and their solution, is screened in the video projections so we can rescue an imagery dimension, in order to create our own fantasmatic cosmos. Inside myself I am able to expand and explore my subjectivity in the world. However, while I am asleep my rationality is disconnected and so I will not be productive and, simultaneously, I will be indistinct from others. That way, from my interiority, alterity will emerge. By doing so the director (and the visitor) activates the arts as a site for both being and recognition.

Art is, and so I believe, entangled with life and with its political meaning. Parasomnia ascribes to the power of art as the performance extols and commends sleep as a space of liberty and out of vigilance and commodification regimes. To perform an action as sleep, in an aesthetic form, pleads against the capitalisation of our lives. While accepting pauses and unproductiveness we render sleep key to our health, well-being, and even sociability.

Besides its cultural meaning, is there a more powerful act-up, a political confrontation towards the colonisation of time than a bodily manifestation? If we become conscious of that, a simple organic expression becomes a strong political statement, as the title of the article alludes.

In brief, Parasomnia permits the flow of human textures and its temporalities to be contaminated by affects. Waking imagination may well be a fine political gesture, similar to a refusal, or even a countermeasure, an antidote. Sleep may well be both a concrete act of empathy towards the world, and a resistance against biocapitalism. So let us have a moment and contemplate.