Fit for the Job: Proportion and the Portrayal of Cattle in Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Domestic Cattle and Their Role(s) in Ancient Egypt

2.1. The Origins and Domestication of Cattle in Ancient Egypt

2.2. The Role(s) of Domesticated Cattle in Egyptian Culture and Society

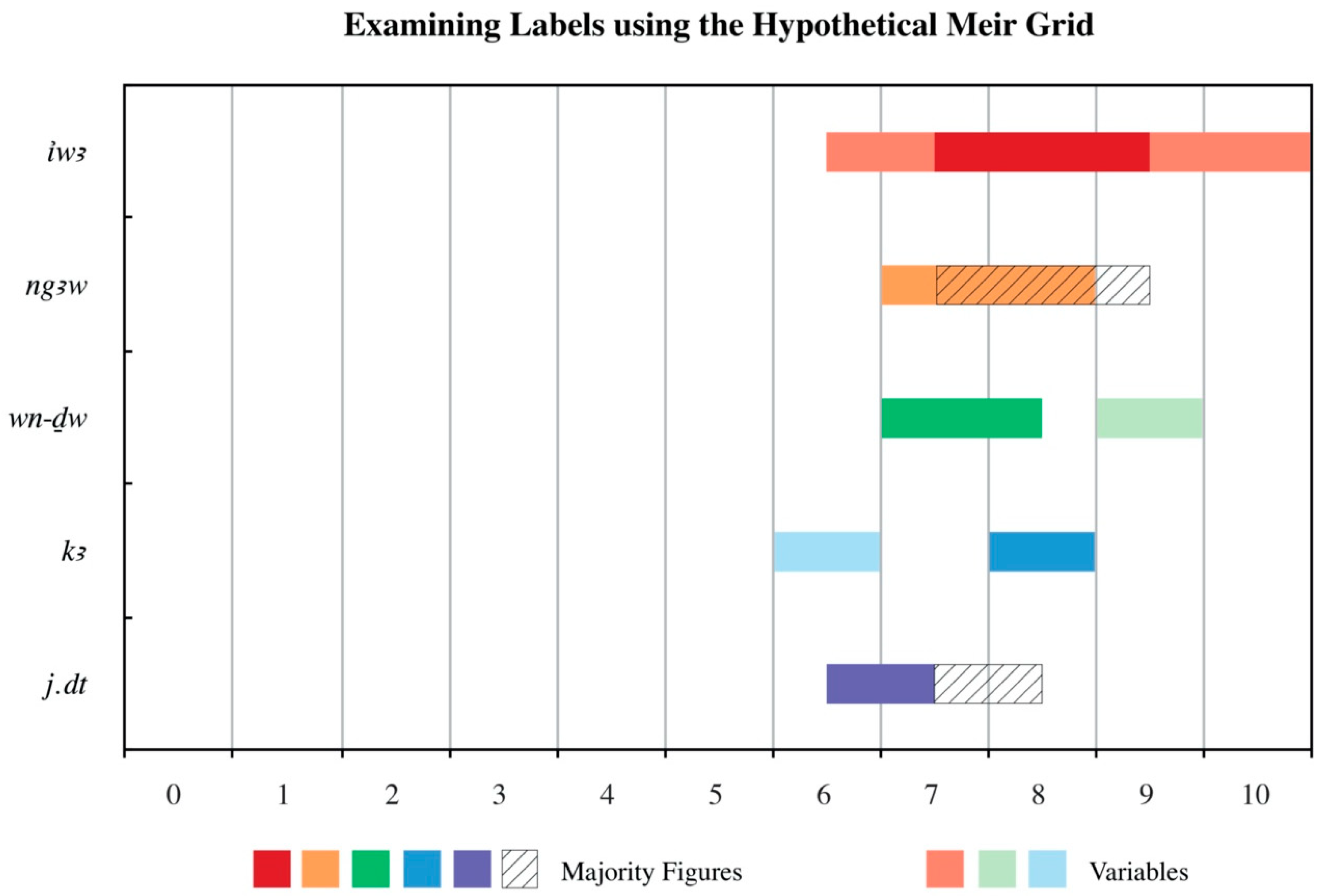

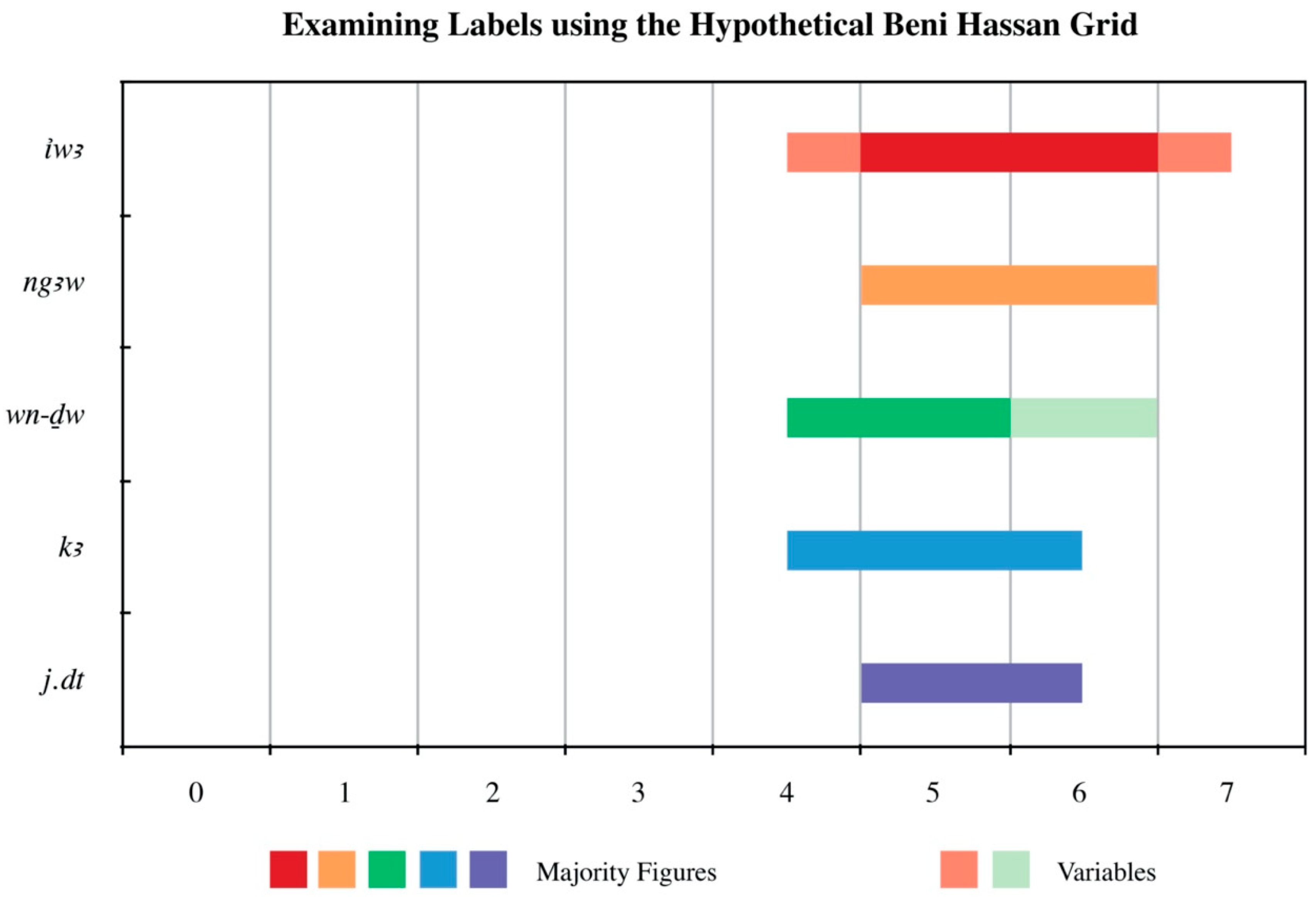

- iwA: the label commonly associated with stabled cattle or animals fattened for slaughter, especially large-stomached animals.12

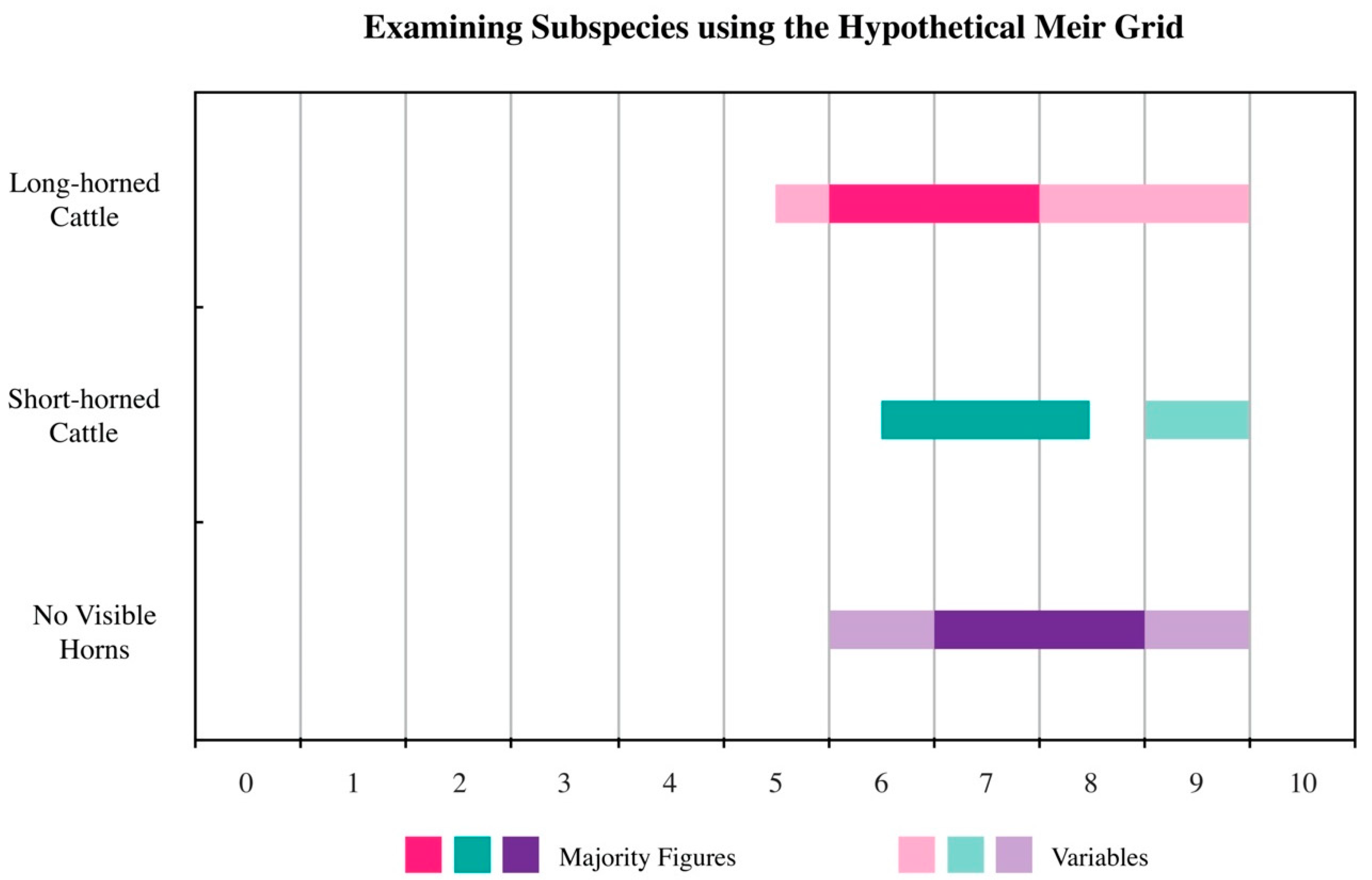

- ngAw: a variation of the term ng which is used to label wild bulls. It is believed that ngAw cattle were the working animal of choice, coming from long-horned stock derived from wild bovines (Ikram 1995, p. 15; Brewer 2001, p. 435).

- kA: the word for bull. As touched upon earlier, kA were generally not consumed by the Egyptians until they were no longer required namely as stud animals (Ikram 1995, p. 15).

- jd.t: the Egyptian term for cow, jd.t, could also relate to female genitalia (Evans 2017, p. 42).

- wn-Dw: generally reserved for short-horned or polled animals, though sources have suggested that this label may also be used for cows (Ikram 1995, p. 15; Brewer 2001, p. 435).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biological Factors

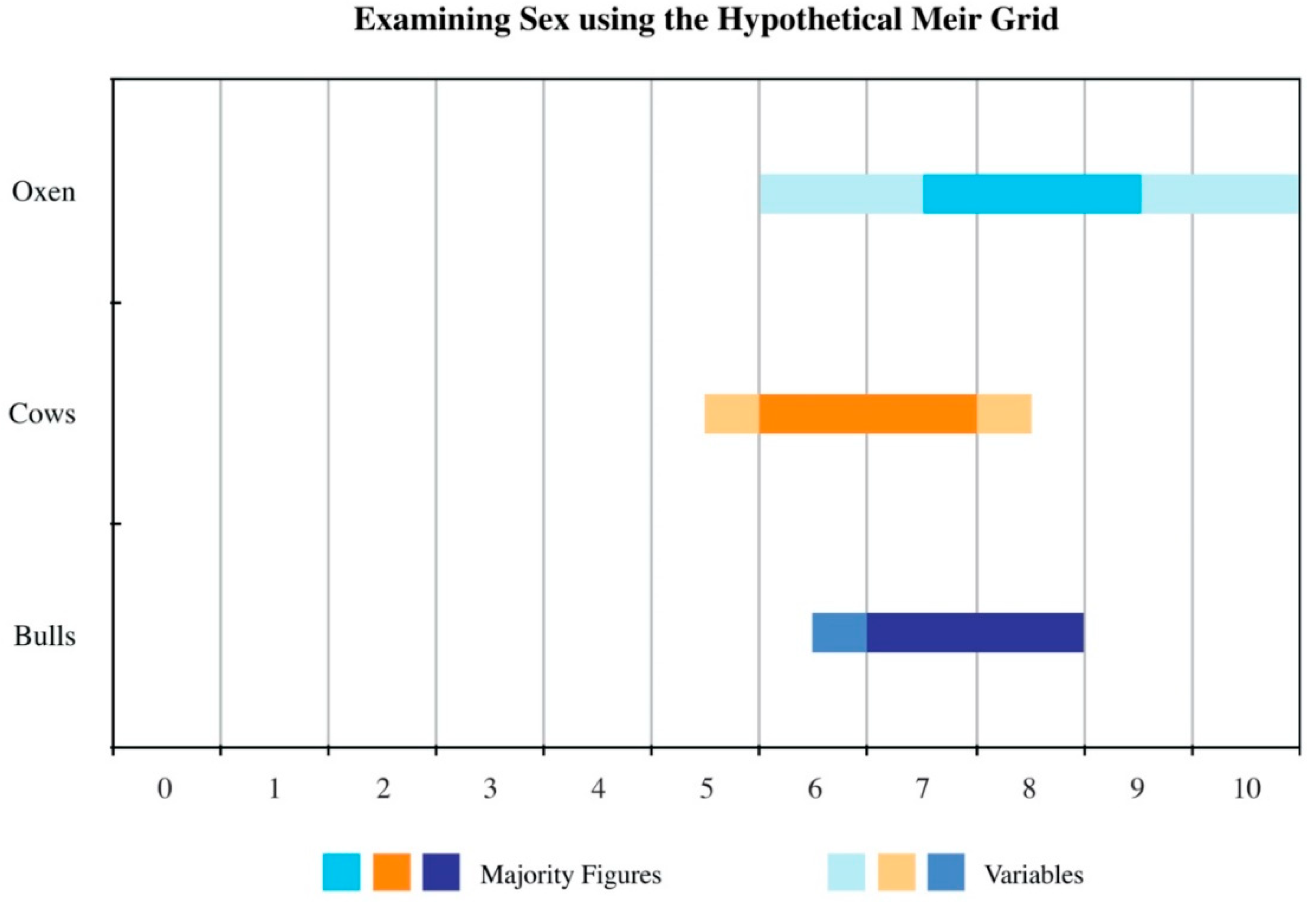

3.1.1. Sex

3.1.2. Subspecies of Cattle Based on Horn-Type

3.2. Contextual Factors

3.2.1. Egyptian Label

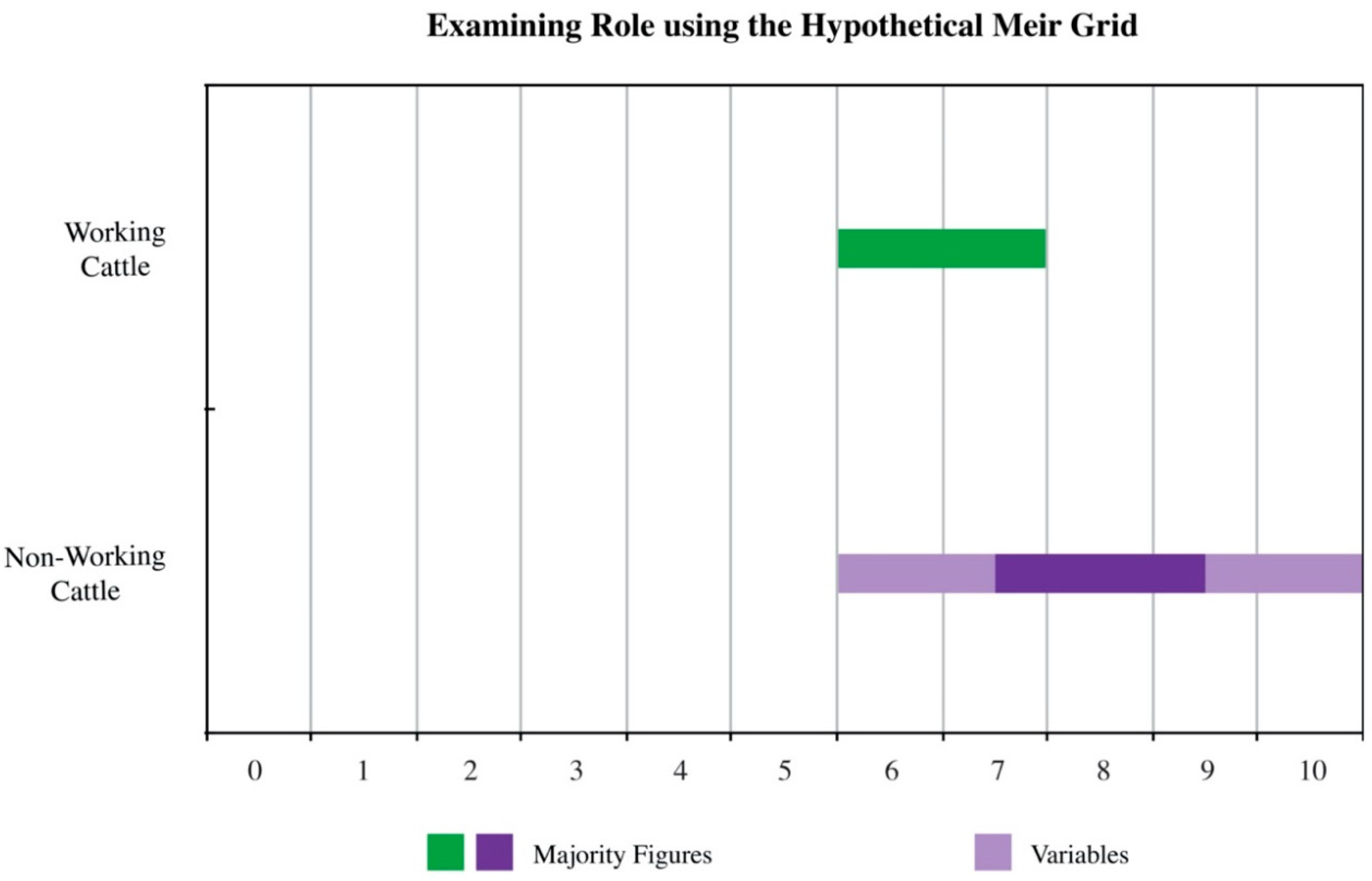

3.2.2. Activity or Role within a Scene

- Working cattle (Figure 3): defined here as bovines, shown in a specific, active role, i.e., those employed as a source of labour or for their physical strength. Working cattle in the current study all appear in the context of agricultural pursuits—i.e., they are either shown assisting farmers with ploughing fields or threshing grain.14 A total of 18 working cattle were examined, 12 of which were oxen and the remaining six being cows.

- Non-working cattle (Figure 4): figures that appear in offering scenes, procession scenes, cattle counts and in images of the tomb owner viewing livestock from their estate/town have been categorised as non-working cattle. The author does note that there may be some limitation with the terminology chosen, however all figures in this group are shown in passive poses and are not being used for physical labour within the scene. Non-working cattle were the larger of the two corpora, with 97 subjects tested. Oxen largely outnumbered the other two sexes at a total of 70 figures, followed by 24 cows and eight bulls.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achilli, Alessandro, Anna Olivieri, Marco Pellecchia, Cristina Uboldi, Licia Colli, Nadia Al-Zahery, Matteo Accetturo, Maria Pala, Baharak Hooshiar Kashani, Ugo A. Perego, and et al. 2008. Mitochondrial genomes of extinct aurochs survive in domestic cattle. Current Biology 18: R157–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmone-Marsan, Paolo, José Fernando Garcia, and Johannes A. Lenstra. 2010. On the Origin of Catlle: How Aurochs Became Cattle and Colonized the World. Evolutionary Anthropology 19: 148–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, John. 1902. The Zoology of Ancient Egypt: Mammalia. London: Hugh Rees. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2002. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Translated by Andrew Jenkins. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bailleul-LeSuer, Rozenn, ed. 2012. Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2015. What is Art? In A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. Edited by Melinda K. Hartwig. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfiglio, Silvia, Catarina Ginja, Anna De Gaetano, Alessandro Achilli, Anna Olivieri, Licia Colli, Kassahun Tesfaye, Saif Hassan Agha, Luis T. Gama, Federica Cattonaro, and et al. 2012. Origin and Spread of Bos taurus: New Clues from Mitochondrial Genomes Belonging to Halpogroup T1. PLoS ONE 76: e38601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Daniel G., David E. MacHugh, Patrick Cunningham, and Ronan T. Loftus. 1996. Mitochondrial diversity and the origins of African and European cattle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 5131–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, Michael. 2013. Revisiting a hoary chestnut: The nature of early cattle domestication in North-East Africa. Sahara (Segrate) 24: 65–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brass, Michael. 2018. Early North African Cattle Domestication and Its Ecological Setting: A Reassessment. Journal of World Prehistory 31: 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Douglas J. 2001. Hunting, Animal Husbandry and Diet in Ancient Egypt. In A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Billie Jean Collins. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Douglas J., Donald B. Redford, and Susan Redford. 1994. Domestic Plants and Animals: The Egyptian Origins. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Betsy M. 2009. Memory and Knowledge in Egypt Tomb Painting. In Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century. Edited by Elizabeth Cropper. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpion, Nadine. 1996. Egypt, Ancient, IX: 3.iii.b. Sculpture, Old Kingdom, Relief. In The Grove Dictionary of Art. Edited by Jane Turner. New York: Grove Dictionaries, vol. 2, pp. 871–72. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet. 1992. How the wild beasts were tamed. New Scientist 15: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock, Juliet. 2012. Animals as Domesticates. Michigan: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Whitney. 1989. The Canonical Tradition in Ancient Egyptian Art. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Hellmut. 1971. The Origin of the Domestic Animals of Africa. New York: Africana Publication Corporation, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2010. Animal Behaviour in Egyptian Art. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2017. La Vache: Symbole de la solicitude dans la vie quotidienna des anciens Égyptiens. Egypte, Afrique et Orient 86: 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, Rita E. 1984. Development of Middle Kingdom Egyptian Relief Sculptural Schools of Late Dynasty XI with an Appendix on the Trends of Early Dynasty XII (2040—1878 B.C.). Ph.D. thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, Achilles. 1980. Contributions to the archaeozoology of Egypt. In Prehistory of the Eastern Sahara. Edited by Fred Wendorf and Romuald Schild. London: Academic Press, pp. 345–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, Achilles. 1984. Archaeozoology of the Bir Kiseiba region, Eastern Sahara. In Cattle-Keepers of the Eastern Sahara: The Neolithic of Bir Kiseiba. Edited by Fred Wendorf, Romuald Schild and Angela E Close. Dallas: Department of Anthropology, Southern Methodist University, pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Germond, Philippe, and Jacques Livet. 2001. An Egyptian Bestiary: Animals in Life and Religion in the Land of the Pharaohs. New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford-Gonzalez, Diane. 2011. Domesticating Animals in Africa: Implications of Genetic and Archaeological Findings. Journal of World Prehistory 24: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigson, Caroline. 1991. An African origin for African cattle?—Some archaeological evidence. African Archaeological Review 9: 119–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, Yvonne. 1987. Decoration in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom: Studies in Orientation and Scene Content. London: KPI. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, Mary, Conni Lord, and Linda Evans. 2017. Animals in Ancient Egypt: Roles in life and death. In Death Is Only the Beginning: Egyptian Funerary Customs at the Macquarie Museum of Ancient Cultures. Edited by Yann Tristant and Ellen M. Ryan. Oxford: Aris and Phillips, pp. 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Robert. 1864a. Versuch einer systematischen Aufzählung der von den alten Aegyptern bildlich dargestellten Thiere (mit Rücksicht auf die heutige Fauna des Nilgebietes). Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 2: 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Robert. 1864b. Versuch einer systematischen Aufzählung der von den alten Aegyptern bildlich dargestellten Thiere (mit Rücksicht auf die heutige Fauna des Nilgebietes). Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 2: 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda K. 2004. Tomb Painting and Identity in Ancient Thebes, 1419-1372 BCE (Monumenta Aegyptiaca IX). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, Patrick F. 1986. The Birds of Ancient Egypt. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, Patrick F. 1996. Animal World of the Pharaohs. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima. 1995. Choice Cuts: Meat Production in Ancient Egypt. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, Salima, ed. 2005. Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Erik. 1955. Canon and Proportions in Egyptian Art, 1st ed. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Erik. 1975. Canon and Proportions in Egyptian Art, 2nd ed. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, Jochem. 2013. Proportionen und Stile in den assiutischen Nomarchengräben der Ersten Zwischenzeit und des Mittleren Reiches. In Decorum and Experience: Essays in Ancient Culture for John Baines. Edited by Elizabeth Frood and Angela McDonald. Oxford: Griffith Institute, pp. 141–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2001. The Tomb and Beyond: Burial Customs of Egyptian Officials. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib. 2011. Art and Gridlines: The copying of Old Kingdom scenes in later periods. In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Edited by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens and Jaromír Krejčí. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, vol. 2, pp. 483–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Linda Evans. 2014. Beni Hassan I: The Tomb of Khnumhotep II. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Linda Evans. 2016. Beni Hassan III: The Tomb of Amenemhat. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Linda Evans. 2017. The Cemetery of Meir IV—The Tombs of Senbi I and Wekh-Hotep I. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchell, Kenneth F. 2020. Seeing the Dog: Natural Canine Representations from Greek Art. Arts 9: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linseele, Veerle, Wim Van Neer, Sofie Thys, Rebecca Phillips, René Cappers, Willeke Wendrich, and Simon Holdaway. 2014. New Archaeozoological Data from the Fayum “Neolithic” with a Critical Assessment of the Evidence for Early Stock Keeping in Egypt. PLoS ONE 9: e108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, Nicolle. 2014. A Walk on the Wild Side: Animal Figures and the Canon of Proportion in Middle Kingdom Wall Scenes at Meir. 2 vols. Masters of Research thesis, Macquarie University, North Ryde, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, Nicolle. 2019. If the Grid Fits: Animal Figures and Proportional Guides in Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery. 2 vols. Ph.D. thesis, Macquarie University, North Ryde, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, Nicolle. Forthcoming. Digitising the Hypothetical Grid: A New Tool for Investigating Animal Figures and Ancient Egyptian Proportional Guides.

- Osborn, Dale J., and Jana Osbornová. 1998. The Mammals of Ancient Egypt. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1955. Meaning in the Visual Arts. New York: Doublebay Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, William H. 2015. The Ordering of the Figure. In A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. Edited by Melinda K. Hartwig. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 360–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pardal, Lucia, Luis J. Royo, Albano Beja-Pereira, Shanyuan Chen, Rudolfo Juan Carlos Cantet, Amadou Traoré, Ino Curik, Johann Sölkner, Ricardo Bozzi, Iván Fernández, and et al. 2010. Multiple paternal origins of domestic cattle revealed by Y-specific interspersed multilocus microsatellites. Heredity 105: 511–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcier, Stéphanie, Salima Ikram, and Stéphane Pasquali, eds. 2019. Creatures of Earth, Water and Sky: Essays on Animals in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden: Sidestone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riemer, Heiko. 2007. When hunters started herding: Pastro-foragers and the complexity of Holocene economic change in the Western Desert of Egypt. In Aridity, Change and Conflict in Africa, Proceedings of the International ACACIA Conference, Königswinter, Germany, 1–3 October 2003. Edited by Michael Bollig, Olaf Bubenzer, Ralf Vogelsang and Hans-Peter Wotzka. Köln: Heinrich Barth Institut, pp. 105–44. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, Gay. 1994. Proportion and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Heinrich. 2002. Principles of Egyptian Art, 4th ed. Translated by John Baines, Emma Brunner-Traut, and John Baines. Oxford: Griffith Institute Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Andrew B. 1986. Cattle domestication in North Africa. African Archaeological Review 4: 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Andrew B. 1992. Origins and spread of pastoralism in Africa. Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 125–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Andrew B. 2005. African Herders: Emergence of Pastoral Traditions. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, William S. 1978. A History of Egyptian Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, Kevin J., and David J. Mellor. 2005. The welfare significance of the castration of cattle: A review. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 53: 271–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, Frauke, and Diane Gifford-Gonzalez. 2013. Genetics and African Cattle Domestication. African Archaeological Review 30: 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, Sasha. 2014. Cultural Expression in the Old Kingdom Elite Tomb. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Wendorf, Fred, and Romuald Schild. 1994. Are the Early Holocene Cattle in the Eastern Sahara Domestic or Wild? Evolutionary Anthropology 3: 118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendorf, Fred, and Romuald Schild. 1998. Nabta Playa and Its Role in Northeastern African Prehistory. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 17: 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, Alexandra, and Nicolle Leary. 2017. ‘Art’, Aesthetics and the Functioning Image in Ancient Egyptian Elite Tombs. In Death is Only the Beginning: Egyptian Funerary Customs at the Museum of Ancient Cultures, Macquarie University. Edited by Yann Tristant and Ellen M. Ryan. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In periods of Egyptian history outside the focus of the current paper, elite tombs could also include further architectural divisions that primarily consisted of an additional level dedicated to the solar cult. See Hartwig (2004, p. 15 ff.). |

| 2 | The author uses the term ‘daily life’ with caution here as there is on-going dialogue surrounding the application of such a designation. As noted by Hartwig in her study of elite Theban tombs of the 18th Dynasty, the use of terms like ‘daily life scenes’ may reflect a modern bias in categorizing imagery that was not shared by the ancient Egyptians. For an extended discussion on the topic, see Hartwig (2004, pp. 49–50). |

| 3 | For an extended overview of existing research on the animal world in ancient Egyptian wall scenes, see Evans (2010, pp. 1–12). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | For examples, see: Ikram (1995, 2005); Houlihan (1996); Germond and Livet (2001); Bailleul-LeSuer (2012) and Hartley et al. (2017) and Porcier et al. (2019). |

| 6 | Human-orientated bias in art historical studies arguably stems from Platonism, which experienced a resurgence in the Renaissance period, where it was the enduring belief that ‘man is the measure of all things’ (Plat. Theaet. 152). It would appear that this mentality has continued to influence Western academia. In Egyptology, we see this idea prevail in texts such as Schäfer’s influence work, Principles of Egyptian Art, where he states that ‘the human form is the most important element in art’ (Schäfer 2002, p. 290). For an example of a parallel discussion in the study of Ancient Greek art, see (Kitchell 2020). |

| 7 | Robins (1994, p. 64). Although the Old Kingdom Achsenkreuz commonly measured six horizontal lines in height, Robins notes that that guideline systems may contain up to eight horizontal lines in their construction. |

| 8 | While the 12th Dynasty is usually noted as being the approximate starting point for the use of squared grids as proportional guides, Freed suggests that the new system was first used in Mentuhotep II’s mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahari, which dates to the earlier 11th Dynasty. Based on the historical and political context of the time, the author believes that the canon being used earlier in the Middle Kingdom (i.e., the 11th Dynasty) is both a plausible and convincing argument. For Freed’s commentary, see Freed (1984, pp. 83–84). For dating attributed to the later 12th Dynasty, see Robins (1994, p. 70). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | For a more detailed review of the on-going debate(s) surrounding cattle domestication in Africa, see: Brass (2018); Stock and Gifford-Gonzalez (2013). |

| 11 | For an extended list of common Egyptian labels used for cattle, see Ikram (1995, pp. 14–5). |

| 12 | Ikram (1995, p. 15); Brewer (2001, p. 436). It is important to note that while most animals used in food production were likely to be oxen, there appears to be no distinct word for ox except in circumstances where castration is specified to distinguish the animals from bulls in contexts where they appear together. See Ikram (1995, p. 15). |

| 13 | The Old Kingdom elite cemeteries included in the study were Giza, Saqqara, Deir el-Bersheh, Deir el-Gebrawi and El-Hawawish, while those dating to the Middle Kingdom were Asyut and Sheikh Abd el-Qurna. The final sites—Meir, Beni Hassan and Qubbet el-Hawa—had both Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom cemeteries, hence the overall total of 13. For a complete breakdown of the tombs examined and their dating, see Volume II of Leary (2019). |

| 14 | Although no examples of cattle in large herding or river crossing scenes are included in the corpus as a result of damage to the image or a key point of the body not being visible, it may be possible to extend the definition of working cattle to include these figures in future studies. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leary, N. Fit for the Job: Proportion and the Portrayal of Cattle in Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery. Arts 2021, 10, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010013

Leary N. Fit for the Job: Proportion and the Portrayal of Cattle in Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery. Arts. 2021; 10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeary, Nicolle. 2021. "Fit for the Job: Proportion and the Portrayal of Cattle in Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery" Arts 10, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010013

APA StyleLeary, N. (2021). Fit for the Job: Proportion and the Portrayal of Cattle in Egyptian Old and Middle Kingdom Elite Tomb Imagery. Arts, 10(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010013