Abstract

Using archival records of the Sagrario Metropolitano and material analysis of extant prints, the paper presents the life and work of the only known woman printmaker in viceregal New Spain, María Augustina Meza. It traces Meza and her work through two marriages to fellow engravers and a 50-year career as owner of an independent print publishing shop in Mexico City. In doing so, the paper places Meza’s print publishing business and its practices within the context of artists’ shops run by women in the mid- to late-eighteenth century. The article simultaneously extends the recognized role of women in printing and broadens our understanding of women within the business of both printmaking and painting in late colonial Mexico City. It furthermore joins the scholarship demonstrating with new empirical research that the lived realities of women in viceregal New Spain were more complex than traditional, stereotypical visions of women’s lives have previously allowed.

1. Introduction

Complying with his annual duty to count the parishioners of Mexico City’s Sagrario Metropolitano, Father Joseph Félix Colorado walked the streets of the capital city’s central district in the spring of 1770. At each address—business, residence, or both—he collected a cédula from the adult occupants. This printed slip proved annual participation in the sacraments of confession and communion and allowed the Church to tally its parishioners.1 In the corresponding padrón registry book, he listed the address, the type of structure, the nature of any business transacted inside, and the occupants, usually beginning with the male head of household followed by his wife and children and ending with apprentices and servants. On calle de Tacuba, as on other streets, Colorado visited casas de vecindad and casas altas filled with multiple families, casas grandes housing the large households of the city’s elite, and the rustic covachas of the parish’s most impoverished. He also visited a variety of small businesses, from candle shops to pharmacies, some serving as both residences and places of business, noting at unoccupied shops, “No one sleeps here.” The largest of these firms occupied the entire building while others, known as accesorias, took up just a room or two open to the street on the ground floor of a residential building. These rooms served as workshops, residences, or both.

Stopping outside a casa de vecindad on the north side of Tacuba near the corner with calle de Manrique, Colorado entered one of these small shops. Both occupants produced their cédulas and the priest continued on his way. When he returned to the parish, Colorado wrote of the location in his padrón book: “Accesoria Printing Press, [calle de Tacuba] number 52, Don Francisco Gutiérrez, María Augustina Meza.”2

The existence of engraver Francisco Gutiérrez’s printmaking workshop on Tacuba has been known for years. In fact, he inscribed the location of his shop on five of his 15 known prints. Based on these inscriptions, historian Manuel Romero de Terreros first identified the workshop in his 1949 seminal study of viceregal printmaking.3 Nor is it news that Gutiérrez not only engraved plates at that location but printed them on his own press. An Inquisition document published in 2000 listed Gutiérrez’s as one of the eight imprentas de láminas or independent print publishing presses operating in Mexico City in 1768.4 Like his print publishing colleagues, Gutiérrez had at least one tórculo or intaglio roller press upon which he pulled prints; some may have also had a letter press for printing small typographic jobs with movable type, although these were generally handled by the city’s typographic presses.5

The new information provided by the record of the priest’s 1770 padrón visit is that Gutiérrez worked with María Augustina Meza, the only known woman engraver from the viceregal era.6 Prior to the discovery of the padrón record, a single signed print was the only evidence of Meza’s printmaking activities and she was not mentioned in Romero de Terreros’s study of colonial printmakers. The 1770 padrón reveals, however, that Meza was not just an interested amateur responsible for a single plate but was instead a print publisher.

The present article examines the invaluable record that the annual padrón visits represent, in concert with other church documents and surviving prints, to trace Meza’s long career in the printmaking business. In the process, the analysis reveals a network of independent print publishers and engravers in late eighteenth-century Mexico City.7 Just as significantly, examining Meza’s career through the padrón records uncovers the heretofore under-recognized presence of women in the viceregal capital’s art world. This includes not just Meza, but also other women involved in the print publishing business. Moreover, deploying the same method that reveals Meza’s leadership of her print publishing shop, the article uncovers a group of previously unknown women who operated painting shops in the viceregal capital in the last decades of the colonial era. Together, the discussion of Meza’s press and the women-run painting shops expands our understanding of women in Mexico City’s art businesses at the end of the colonial era. It furthermore offers a first introduction of New Spain into the scholarship on women in the early modern art market.

2. Locating Augustina Meza

The exact nature of the relationship between Meza and Gutiérrez is not clarified by the 1770 padrón. Father Colorado provided no details and conventions for padrón record listings allowed her to be either his employee or his wife.8 Other parish records, however, shed additional light. On 3 November 1765, don Francisco Gutiérrez y Orta and doña María Augustina de Meza married at a friend’s home.9 Their union soon bore fruit. María Rosa Ramona Gutiérrez, daughter of Francisco and Augustina, was baptized at the parish in 1766.10 Maria Loreto Gutiérrez followed in 1768.11

It was around this point that the Gutiérrez/Meza print publishing shop opened. The 1768 padrón lists an unoccupied imprenta or press on Tacuba that likely belonged to the couple; this date corresponds to the earliest works signed by Gutiérrez.12 The shop was located a few doors down from the imprenta de estampas or printmaking press belonging to the prolific engraver José Mariano Navarro. Their location choice is unsurprising since Tacuba was located in the heart of Mexico City’s religious and commercial center. The shop was also within striking distance of the city’s typographic printers who routinely called upon engravers to illustrate their broadsheets, pamphlets, and books; the press belonging to María de Rivera and her heirs was around the corner on Empedradillo. By opening a print publishing press at this location, Gutiérrez and Meza set themselves up to benefit from the foot traffic of pious Mexicans visiting the cathedral and nearby churches. It also put them in a prime position to secure commissions from the capital’s intellectual and bureaucratic elite who lived and worked near the main square. These diverse customers sought prints ranging from small images of generic devotional themes to unique portraits, maps, views, scientific illustrations, and heraldry up to folio sized.

By 1768, Mexico City was home to several shops making and publishing prints. In addition to the Gutiérrez/Meza and Navarro shops on Tacuba, six other printmaking presses operated in the area.13 The closest to Tacuba belonged to Cayetano de Sigüenza, an architect who purchased an imprenta de láminas (engraving press) on Escalerillas from engraver Francisco Sylverio in 1763, but left operations to his employees (Castro Morales 1990, p. 138). The rest of the printmaking presses were run by engravers who, like Gutiérrez and Navarro, printed plates on their own tórculos or intaglio presses: Manuel de Villavicencio on calle de Polilla, José Benito Ortuño by the church of San Hipólito, his brother Juan de San Pedro Ortuño on calle de Manrique,14 Salvador Hernández y Zapata on calle de Hospicio, and Juan del Prado on calle de San Juan. Engravers who did not own shops worked nearby, either at their own homes or as journeyman assistants at the presses listed here.15 Some of these artists engraved plates to augment earnings from jobs in such diverse fields as altarscreen design, silversmithing, and the viceregal bureaucracy. These contractors and part-time printmakers, as we would call them today, are known thanks to their signatures inscribed at the foot of their images to which the press owners sometimes added their street address. At the same time, an immense number of prints produced in this era were unsigned, complicating attribution.

The industry Gutiérrez and Meza joined when they opened their printmaking press was largely unregulated; raising capital and building inventory were likely their greatest obstacles. The new press owners faced no formal restrictions regarding their work with the public because printmakers and print publishers had no guild. The industry had only developed to the point of having multiple, competing practitioners dedicated full-time to making prints in the mid-eighteenth century, when guilds were on the wane.16 Thus neither Gutiérrez nor Meza needed to be an accredited master before opening their own shop, as was required for guild-regulated painters; all they needed was equipment, inventory, and a physical location.

Along with their fellow printmakers and print publishers, however, Gutiérrez and Meza did engage informally in guild-like activities as the field copied age-old practices to form and pursue the profession.17 This included directly or indirectly denying the participation of mixed-race, Indian, and Black artists, following the model of the painters’ guild, at least in its ordinances if not its practices. Analysis of padrón and other church records reveals that Gutiérrez, Meza, Navarro, and all other documented printmakers and print publishers in this era were identified as Spaniards, either locally born criollos or immigrants from Spain.18 This racial affinity was undoubtedly supported through the selection of apprentices and journeyman employees. As one of the mechanical arts requiring intellectual effort, not just physical exertion, printmaking and print publishing required apprenticeship according to Sonia Pérez Toledo’s study of labor in colonial Mexico reveals (Pérez Toledo 2005, p. 52). Young engravers needed training in drawing, plate preparation, burin handling, inking, and press operation. Unsurprisingly, padrón records place several apprentices in printmaking shops for this reason. The two leading print publishers make this clear. New research reveals that Spanish immigrant engraver Baltasar Troncoso y Sotomayor trained printmaker Salvador Hernández y Zapata at his shop on calle de Hospicio in the 1740s; Zapata, identified as Spanish, would eventually take over the business.19 Likewise, the city’s most prolific engraver and independent print publisher at mid-century, Francisco Sylverio, had at least three Spanish apprentices at his shop on calle de las Escalerillas before he sold it to Sigüenza.20 As revealed below, the padrón records place two apprentices at the Gutiérrez/Meza firm over the years; both were Spaniards.

Gutiérrez, listed as a Spaniard in all documents, clearly benefited from this privilege and presumably trained with either Troncoso or Sylverio before opening his press.21 There he learned both the art and craft of engraving and printing as well as the practices and norms of the print publishing business. Meza, on the other hand, was likely just 15 years old when the couple married and may have learned from her husband. As Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru notes of working women in colonial Mexico City, it was common among artisans of all types that “the wife would be incorporated into the shop’s workforce.” (Gonzalbo Aizpuru 2016, position 3478). This was also true of children. Francisco Sylverio’s son, for example, worked his entire career as an intaglio press operator in his father’s printmaking shop.22 Meza may similarly have learned from her father. An engraver named Ignacio Meza had a workshop on Puente del Espíritu Santo in the 1760s, although no documents have emerged linking Augustina Meza to this artist.23

Whatever Gutiérrez’s and Meza’s training may have looked like, it certainly included developing a healthy respect for the Holy Office of the Inquisition and a keen desire to steer clear of its investigations. The Mexican Inquisition was, after all, charged with maintaining religious decorum and orthodoxy, including in art. Engravers were thus well-advised to learn acceptable Christian iconographies. Nevertheless, within months of opening their shop, Gutiérrez and Meza were subjected to one of the rare occasions of inquisitorial intrusion in print publishing.

On 28 July 1768, Inquisition notary José de Overso Rábago was charged with notifying each of the city’s printers that they were legally required to submit all imprints for inquisitorial review before publication. The impetus for this reminder of Spanish law and the clarification that it included estampas, not just books and pamphlets, was the 1767 publication of a sermon, Hermosura de la iglesia. Typographic printer Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontíveros had recently published the text without prior approval. Henceforth, printers were to submit one copy of any “paper, book, or print” to the Holy Office before distribution or risk a fine of 50 pesos and excommunication.24 To ensure compliance, Overso Rábago visited all the city’s typographic and print publishing presses. On 29 July 1768, he entered the “imprenta de estampas of don Francisco Gutiérrez” on calle de Tacuba. He read the decree to its owner, who pledged compliance and signed his name.25 There is no record, however, that Gutiérrez—or any other print publisher working in Mexico City, for that matter—ever complied.

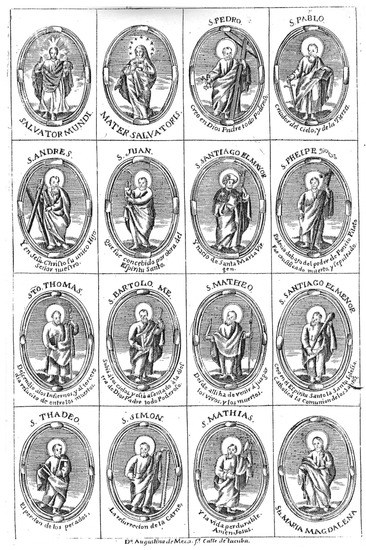

While the Gutiérrez/Meza shop presumably produced enough prints to remain in business, only 20 engravings signed by Gutiérrez and one by Meza are known today; the rest were likely printed anonymously. This small number of signed works nevertheless provides glimpses into the shop and its operations. It was possibly during this period following the opening of the press in 1768 that Meza created the only known engraving to bear her full name. The engraving of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Apostles held in the archive of the Holy Office of the Inquisition (Figure 1) at the Archivo General de la Nación, includes the signature “D[oñ]a Augustina de Meza f[eci]t. Calle de Tacuba.”26 The image features 16 figures within oval frames. All are accompanied by their name and a portion of the Apostles’ Creed. The small engraving reveals a careful and competent artist adept at rendering the human figure and spaces with convincing illusionism. As it is clearly not the work of a novice but instead of a practiced hand, we may assume that this was not Meza’s first print.

Figure 1.

Augustina Meza, Christ, Mary, and the Apostles, ca. 1770. Engraving. Photograph by the author.

The print ended up in Inquisition hands after it had traveled to the Philippine Islands in 1776 in a box of religious items. A friar in Manila sent the print back across the Pacific to the Inquisition in Mexico City to determine its orthodoxy and whether it violated rules of decorum for religious images. His concern was that parts of the Apostles’ Creed were inscribed below each apostle such that “creator of Heaven and Earth” appeared below Saint Paul.27 Following a short review, the Mexican inquisitors determined that the print did not violate Church doctrine. They said nothing about its artist or her gender. It would seem that the inquisitors saw no problem with its female authorship, a point taken up later in this article.

Yet her status and gender were clearly significant to Meza as she prepared the image. She added the honorific title doña to her name, something unheard of among known Mexican colonial engravers at the time. Only engraver José Joaquín Fabregat added don before his name when he arrived from Spain in 1788 to staff the Royal Academy of the Three Noble Arts of San Carlos.28 Nor, it should be noted, was the title don common among painters’ signatures in this era. Instead, Meza may have been inspired by Spanish printmaker María Eugenia de Beer, who invariably signed her plates with her full name and the honorific title during the seventeenth century.29 Moreover, by writing fecit or “made it” following her name instead of the more common sculpsit (“engraved it”) like her husband, Meza staked her claim to the image’s entire creation: design, engraving, and printing.

Meza also emphasized the location of her shop in the inscription. This was a practice common to both book publishers and printmaking presses in eighteenth-century Mexico City. Her business partner and husband did likewise, as did their competitors Navarro, Sylverio, and Villavicencio. Like them, Meza and Gutiérrez expected prospective customers who saw their prints circulating in New Spain to seek them out on Tacuba to satisfy their printed image needs.

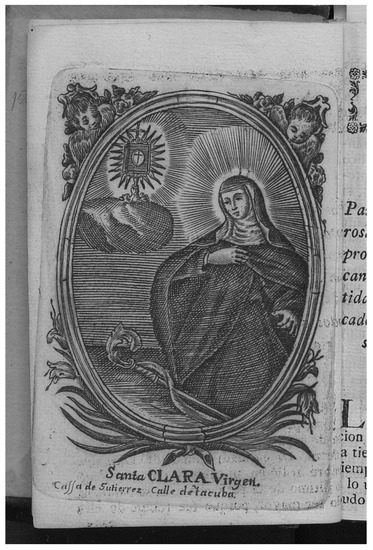

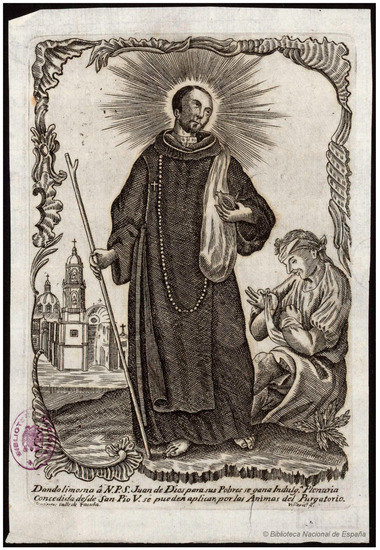

Like the inscription on the print of Christ and the Apostles, signatures added to plates from the Gutiérrez/Meza press reveal that the shop counted on the participation of other engravers for its output during this era. Two engravings reproduced by Manuel Romero de Terreros—an image of the Veronica Veil and a likeness of Saint Teresa of Ávila—as well as a newly-attributed image of Santa Clara (Figure 2) bear the inscription “Casa de Gutiérrez. calle de Tacuba.”30 Using casa de (or chez as it was commonly used in French printmaking in this era) identified the shop’s owner to distinguish him both from the engraver who cut the plate and from other publishers located on the same street, such as Paris’s famed rue Saint-Jacques. Casa de was not, however, commonly used on prints made in Spain or the Americas. This unusual label opens up the possibility that Gutiérrez was not the prints’ engraver even though the images were printed on his press and available at his shop. The anonymous engraver working for the Casa de Gutiérrez may have been Augustina Meza, who opted to sign with her husband’s business name. Yet the press also printed works engraved by other Mexican printmakers. An image of Saint John of God standing in front of the church of his order in Mexico City (Figure 3), for example, bears the signature “Gutiérrez. calle de Tacuba. Villavicencio sc[ulpsit].” Since Villavicencio had his own shop on calle de Polilla, Gutiérrez either contracted him to engrave the image or acquired an existing plate from Villavicencio or his patron, a common practice among the city’s print publishers. Upon acquiring the plate, Gutiérrez added his own name and address to its inscription.

Figure 2.

Augustina Meza, attributed, Santa Clara, ca. 1770. Engraving. Photograph used with permission of the Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Texas A&M University.

Figure 3.

Manuel de Villavicencio, San Juan de Dios, ca. 1770. Engraving. Photograph used with permission of the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

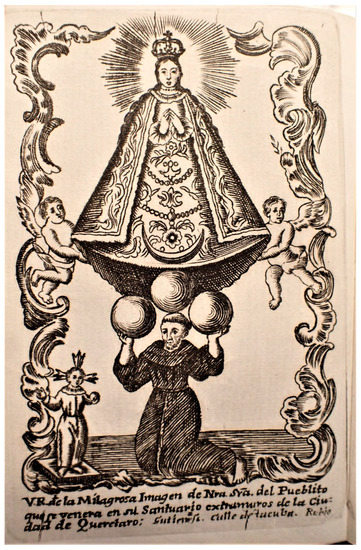

The inscriptions on prints from the Gutiérrez/Meza shop in this era also demonstrate that the couple counted on the assistance of a journeyman engraver. The complete signature on the Veronica Veil engraving reproduced by Romero de Terreros states, “Casa de Gutiérrez, calle de Tacuba, Rubio sc[ulpsit],” with the second name added in a distinct hand.31 This reveals that an engraver named Rubio worked on the plate after its original state and edition, adding his name to the signature to credit his efforts. Similarly, at the lower margin of an undated engraving of Nuestra Señora del Pueblito (Figure 4), Gutiérrez’s familiar signature appears: “Gutiérrez sc[ulpsit]. calle de Tacuba.” Alongside it again is the name “Rubio.” As with the Veronica Veil, according to signing conventions of Mexican colonial prints, this image was originally engraved by Gutiérrez but reworked by Rubio as a new state for printing. More significantly for the purposes of the present study, the signature placed Rubio in the Gutiérrez/Meza shop for a second time, which would soon help Meza immensely.

Figure 4.

Francisco Gutiérrez and Augustín Rubio, Nuestra Señora del Pueblito, ca. 1770. Engraving. Photography by the author.

Despite its auspicious beginning, tragedy soon struck the family when engraver Francisco Gutiérrez died on 27 October 1770. His death notice in the parish archive confirms his Spanish identity, his marriage to “Doña Augustina Meza,” his residence on calle de Tacuba, and his burial at the family’s parish church, the Sagrario Metropolitano.32 Just two days later, the couple’s third child, María Francisca Cenovia Gutiérrez, was born. Her baptismal record entry from 30 October 1770 notes that she was the child of Meza and the deceased Francisco Gutiérrez.33 Meza was now a teenaged widow with three children under five years old, including a newborn.

Yet, Meza’s situation may not have been as bleak as that description sounds. This is because the newborn’s godfather and witness to her baptism was the architect and altarscreen designer Cayetano de Sigüenza (1714/15–1778). Meza may have known Sigüenza from the parish, as he and his family were also Sagrario parishioners. As such, they undoubtedly coincided with Gutiérrez and Meza at the Sagrario’s many services, festivals, and processions throughout each year. More likely, however, is that Meza and Sigüenza knew each other through the network of independent print publishers. Seven years earlier, in 1763, Sigüenza had purchased Francisco Sylverio’s print publishing shop on calle de las Escalerillas and installed his family in an apartment in the adjoining building.34 Although Sigüenza left the press’s daily operations to his staff while he worked on architectural projects, he was surely aware of Gutiérrez’s and Meza’s competing press when it opened in 1768 just one block away.35 The community of print publishers was, after all, rather small. By the time Gutiérrez died and the baby was born in 1770, the competition between the presses was, as with guild-regulated arts and crafts in viceregal New Spain, undoubtedly collegial and the relationship between their owners familiar enough to lead to the compadrazgo or god-parentage.

Meza’s selection of Sigüenza as godfather for her child was particularly crucial considering Gutiérrez’s death. The linking of families via compadrazgo for social or economic advantage was a long-established practice in the colonial world. It was, of course, a means to ensure that the child would be cared for should anything happen to the parents. Yet it was also a method of establishing a social, professional, and economic network. Sometimes this was horizontal between people of equal status, including family members. In other cases, it was vertical, and parents improved their station by selecting godparents of greater means. Members of the social elite, in turn, accepted the role and the patronage it entailed to increase their wealth and social standing.36

This may well have been the case in Meza’s choice of the well-connected Sigüenza. He designed buildings and altarscreens for the city’s elite and had substantial personal wealth. Moreover, his deceased wife, María Vicenta Cabrera, was the niece of Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero, the prolific scholar and author of the well-known book, Escudo de Armas de México.37 Meza’s child would thus be tied to one of the viceregal capital’s most respected families.38

The padrón records reveal that Meza’s selection of Sigüenza may have paid off. Bolstered by Sigüenza’s social and perhaps even financial support—in the form of a loan—Meza reestablished the print publishing shop on calle de Tacuba but at a new address.39 “Doña Augustina Meza Viuda” appears at Tacuba 49 in the 1771 padrón and the 1772 count lists the “Imprenta de María de Mesa” at the same address.40 In other words, Meza had reopened the shop three doors down from the previous location at Tacuba 52. Furthermore, she had done so on her own, as Meza was listed on both padrones as the only adult occupying the accesoria. Evidence presented below, however, reveals that Rubio stayed on to assist even if he did not reside at the business in the early 1770s and was therefore not counted at her address on the padrón.

It comes as little surprise that Meza would continue her deceased husband’s print publishing business, as this was her legal right (Beltrán Cabrera 2014, p. 18). Spanish law gave 20% of Gutiérrez’s estate to Meza and the rest to his daughters, but the business was fully hers (Flint 2013, p. 7; Whittaker 1998, pp. 6–7). As Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru has determined, women-run households and businesses were common in eighteenth-century Mexico City; in 1777, 31% of the city’s households and 17% of its businesses were led by women. Meza qualifies as one of Gonzalbo’s “exceptional women” who maneuvered through the male-dominated world of labor and commerce.41 Although we lack a description of the shop she took over to do so, evidence suggests that it was a modest operation. Meza likely inherited an intaglio press and a small stock of engraved plates kept to satisfy demand for popular devotional themes.42

Putting the print publishing press to work as a widow, Meza acted much like the women who inherited and operated typographic presses in viceregal Mexico City. Luz del Carmen Beltrán Cabrera notes that even Mexico City’s earliest press—Juan Cromberger’s firm founded by Juan Pablos in 1539—almost immediately fell under the control of Cromberger’s wife when her husband died in 1540.43 Pablos’s wife similarly left the press to her daughter, María de Figueroa, although it was run by Figueroa’s husband, Pedro Ocharte (Poot-Herrera 2008, p. 302). Ocharte, in turn, then left the press he inherited to his second wife, María Sansoric, who, like other widows, worked in the shop. Over the next 250 years, Mexican typographic presses, like those throughout the western world, passed into and through women’s hands; Beltrán has identified at least fourteen women book and pamphlet printers active in Mexico City.44 In fact, Marina Garone Gravier argues that Mexican colonial printing “would have been interrupted at a very early date” without women-owned typographic firms, as male printers routinely left their presses to female heirs (Garone Gravier 2020). Among the most prolific were Paula Benavides in the seventeenth century, María de Rivera in the eighteenth, and María Fernández de Jáuregui in the first decades of the nineteenth. Throughout the colonial era, printing presses were therefore most definitely family businesses in which the entire family—even wives and daughters—participated.45

As a widow in charge of a printmaking press, Augustina Meza, like the women owners of typographic presses, became what Garone Gravier identifies as a woman who officially inhabited the “external” world. Her domain extended beyond the home and she entered the world of commerce and self-sufficiency.46 For the widows who inherited typographic presses, this meant bearing the responsibility for all operations that, depending upon the size and type of the firm, included purchasing supplies, overseeing operations or running the press themselves, developing printing projects with authors, proofing texts, soliciting sales, and negotiating legal and financial matters with colonial bureaucracies, from the Inquisition to the viceregal government. The widows managed labor as well, directing specialist compositors, correctors, press operators, and printmakers, when these worked at the firm.

On the other hand, presses dedicated to producing printed images, like Meza’s, operated on a smaller scale, with less staff, and, as noted above, fewer entanglements with ecclesiastical authorities. Meza and her assistant engraved plates and operated the intaglio roller press to print them. They likewise attended to customers who brought plates for printing or commissioned new images, including authors and book publishers seeking illustrations for their texts.47 She also created work of her own initiative on speculation, purchased plates from other printmakers, and, along with her own work and the stock inherited from Gutiérrez, sold prints pulled from these plates to the public. Interestingly, Meza eschewed the practice common to typographic presses that identified women printers on title pages as the “widow of” her deceased husband.

But Meza did not work alone. Not long after reopening in the early 1770s, circumstances again changed at the press on calle de Tacuba. An entry in the Sagrario Metropolitano’s book of weddings records the marriage on 18 March 1776 of “Doña María Augustina Meza, española, vecina de esta ciudad, viuda de Don Francisco Gutiérrez” and “Don Augustín Rubio, español natural y vecino de esta ciudad.”48 Meza married the shop’s journeyman engraver and with this marriage she permanently added a second artist to her press.

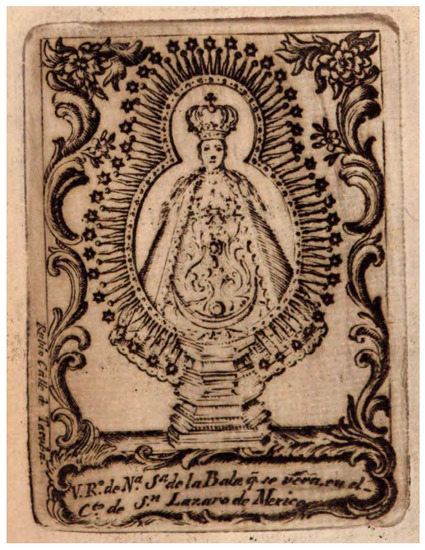

Only ten other prints by Rubio are known, five identified by Romero de Terreros and five new, signed attributions. All, like a small engraving of Nuestra Señora de la Bala (Figure 5), represent religious themes and display competent burin work and the ornate style of the Mexican mid-eighteenth century. Yet this burin work may not have always been Rubio’s. The unusual location of the artist’s signature along the vertical border suggests that the plate may have been engraved by another artist and signed later by Rubio. An engraving of the Trinity (Figure 6) printed in an 1804 edition of Siestas dogmáticas confirms that Rubio reworked and reprinted plates by other artists. To the left of the signature “Rubio sc[ulpsit] Calle de Tacuba” appears the partially effaced inscription “Mex[ico] 1767.” To the right, only the top of the original engraver’s name remains visible. It appears to identify the plate as the work of engraver Joseph Eligio Morales (1729–1776). Interestingly, Morales had apparently reworked a plate originally engraved by Francisco Sylverio, as analysis of the two prints reveals them to be from the same plate.49 Thus, the Rubio edition was from the plate’s third state.

Figure 5.

Augustín Rubio, Nuestra Señora de la Bala, ca. 1780. Engraving. Photograph used with permission of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid courtesy of HathiTrust.

Figure 6.

Augustín Rubio, Santísima Trinidad, ca. 1780. Engraving. Photograph used with permission of the Santa Bárbara Mission Archive Library.

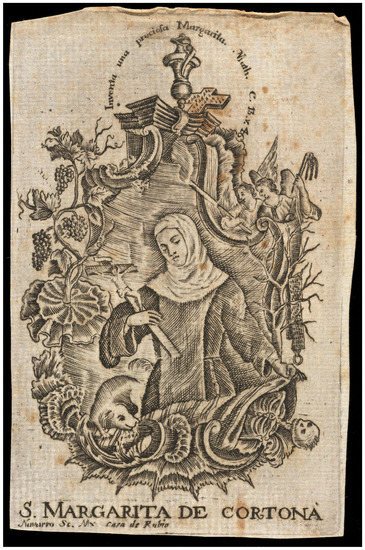

Similarly, an image of Saint Margaret of Cortona (Figure 7) is signed “Navarro sc[ulpsit] Mex[ico].” The identifier “Casa de Rubio” appears alongside and in a different hand. The plate was therefore engraved by Navarro—who had once had a shop on Tacuba but had since moved away—and printed at the press belonging to Meza and Rubio. In this case, as with the plate engraved by Villavicencio several years earlier, the press maintained the original artist’s signature rather than erasing it. This of course begs the question of why Morales’ name would be effaced but not Villavicencio’s or Navarro’s. More importantly for the present article, we are also left to wonder why the shop was identified as “House of Rubio” rather than “House of Meza.” After all, Meza owned the shop and its inventory. Yet unlike typographic firms, where widows’ names were sufficient to guarantee the continuity of output for authors and book buyers, print publishers had no corollary practice. The preponderance of visual evidence therefore makes it clear that with the exception of the print she inscribed with her full name and address earlier in her career, Meza decided that the firm’s reputation was better tied to Gutiérrez and Rubio than to herself. She would not be the only woman print publisher to reach the same conclusion.

Figure 7.

José Mariano Navarro, Santa Margarita de Cortona, ca. 1780. Engraving. Photograph used with permission of Alamy.

Subsequent padrones agree that Rubio had established himself as the face of the press. The 1777 entry on calle de Tacuba reads, “Imprenta Augustín Ruvio, casado con Augustina Mesa, esp[añole]s.” It continues on to list as hijos párvulos Meza’s daughters and a son, Antonio, presumably from the new union.50 Later padrones likewise reveal that the press and the marriage endured. The 1786 padrón lists the “Imprenta de láminas de Augustín Rubio casado con D[oñ]a María Augustina de Mesa.” Meza’s daughters who were by then in their late teens remained at the press; Antonio did not, having either died or left for his own apprenticeship around age 12. A new addition was “José Ignacio el aprendiz” who lived with the family in rooms in the casa de vecindad next door.51 José Ignacio’s apprenticeship was apparently over by the time Meza and Rubio were counted again in the 1789 padrón. On this occasion, the “Imprenta de láminas de Augustín Rubio” on calle de Tacuba counted the couple and Meza’s three adult daughters and two additional, unnamed members of the family, presumably infants.52

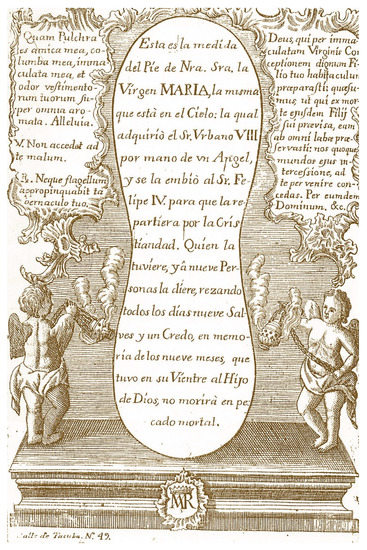

The Meza/Rubio print shop operated on Tacuba without incident for the next few years. There, it regularly created engravings to accompany books and pamphlets published by the typographic firm belonging to Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontíveros located two blocks away on Puente del Espíritu Santo. Rubio engraved a Christ of Esquipulas for Zúñiga’s press in 1784 and a Crucifixion in 1787. The shop was also responsible for a circa 1784 engraving purported to represent the Virgin Mary’s footprint (Figure 8) that ended up in the Inquisition archive.53 The image, bearing only the address calle de Tacuba 49, interestingly garnered no attention from the Inquisitors despite promising a death cleansed of mortal sin to anyone who sent the footprint to nine others and daily prayed nine Salve Reginas and one Credo, an eighteenth-century version of the modern chain letter.

Figure 8.

Anonymous, Medida del pie de Nuestra Señora, ca. 1780. Engraving. Photograph by the author.

At the beginning of the new decade, however, Meza’s circumstances changed again. Augustín Rubio died on 19 September 1790, and was buried in the Sagrario Metropolitano.54 Yet the press continued, now under Meza’s control alone. Significantly, the padrón census three years later counted the widow Augustina and her adult daughters at the accesoria along with a Spanish apprentice named Vicente Naxera, aged 13.55 Thus we can assume that Meza continued to make, print, and sell engravings at the shop with the assistance of her daughters, the apprentice, and, possibly, an unnamed assistant who did not live at the press. More importantly, Meza’s esteem as an engraver and print publisher was sufficient to draw a male apprentice to her press. Her gender apparently did not discourage Naxera’s family from placing their son under her tutelage.

Moreover, the household had grown to now included a 25-year-old parda servant and Meza’s two widowed sisters: Ignacia Meza, 40, and Rosalia Meza, 36. In other words, Meza led one of the “domestic cohabitation groups” that Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru identifies as related or unrelated women sharing living quarters for security and pooled resources.56 As a business owner prosperous enough to live outside her workplace, Meza may have taken in her sisters. Whatever the case, one of the women in Meza’s household placed an amusing notice in an October 1797 issue of the Gazeta de México. Located in the classified section, the announcement asked that “Whoever had seen a pocket watch with two rings made of diamonds, one above and one below, with two [diamonds] missing from the latter, with a large clasp, lost between Tacubaya and Mexico City, please come to the imprenta de estampas on calle de Tacuba, where you will receive your reward and any transportation costs you may have incurred.”57

By 1801, however, circumstances had changed again, and Meza’s apprentice and sisters were gone. The padrón for this year listed the accesoria occupied by the widow Augustina Meza, her three daughters, and an indigenous doncella María Rodríguez; whether they lived there or retained the apartment above cannot be determined.58 Yet the press continued to operate and in 1803, Meza, her daughters, and a mestiza maid named María Simona occupied the imprenta on Tacuba, according to the padrón.59 Meza appeared in the padrón for the last time in 1811. This time her only companions in the accesoria on Tacuba were daughter María Francisca and an indigenous servant María Manuela.60 Her second-oldest daughter, María Loreto, had married and left the family home in 1807, although she lived nearby on calle de Tacuba until her death six years later;61 the fate of daughter Maria Rosas Ramona is unknown. On 27 January 1819, María Augustina Meza died. She was buried the next day at the Church of San Lázaro, just east of Mexico City’s main square, even though both of her husbands were buried at the Sagrario.62 The fate of the print publishing press on calle de Tacuba is unknown.

3. Women in Print Publishing and Painting Businesses in Late Colonial Mexico City

Meza’s career raises important questions. First, was she the only woman operating a print publishing press in Mexico City? The archival record reveals quite incontrovertibly that she was not.63 As he prepared his will in 1778, Cayetano de Sigüenza, the godfather of Meza’s daughter and architect who purchased Sylverio’s printmaking press in 1763, designated María Petra González to run the business after his death. Sigüenza described his “great satisfaction with how she assists me in her honorable practices, and the good accounts she has displayed in the management of said printing press,” justifying his confidence in her skill to lead the business.64 We may therefore conclude that González ran the shop while Sigüenza lived. Even after he died, however, González would not identify herself on the plates the shop printed or have herself identified by the engravers she employed; the prints continued to be disseminated in Sylverio’s name alone.65 Nor did Francisca Castro, a widow who ran a press on calle de la Profesa in 1801 or Micaela Zamora, who operated a tórculo on calle de las Damas after her husband died in 1810 leaving her with a newborn.66 Both women are described in padrón records as residing alone in printmaking presses. Lacking signed prints, it cannot be determined whether they engraved and printed plates or solely managed the businesses, printing images engraved by others. Neither, however, signed the work.

That the labor of Meza, González, Zamora, and Castro within the printmaking and print publishing profession is largely hidden from our historical distance begs the second question: were there women leading businesses dedicated to other visual arts, specifically painting? Tracing Meza’s career through the annual census of the parishioners of the Sagrario Metropolitano reveals that the city had several painting shops that were run by women in similar situations, just as it revealed other women-run print publishing presses. And although evidence has not emerged demonstrating that these women were painters in the way that Meza was also an engraver, the padrón confirms at the very least that they operated painting businesses.

The conventions of the padrón record reveal women at the helm of some of Mexico City’s painters’ shop in the same way that they showed Meza leading the print publishing press. The cleric collecting cédulas was required to note each location’s occupants, usually, though not always, starting with the head of the household followed by spouse, children, resident employees, apprentices, and servants. When accesorias were occupied by colleagues with no families, the business’s owner or overseer presumably appeared first.

Furthermore, just as the clerics who visited Meza’s printmaking press generally noted it as an imprenta, imprenta de estampas, or imprenta de láminas, so, too, did they note painters’ shops with several labels, which they applied to businesses owned and operated by some of Mexico City’s most famous artists. In 1763, for example, the home and shop belonging to painter Juan Gil Patricio Morlete Ruiz and his wife Josefa Careaga was listed simply as “Pintor.”67 The priest performing the 1777 padrón used “Obrador de Pintor” to describe the workshop of Santiago Sandoval, while other clerics chose “accesoria de pintor” to identify shops belonging to Luis de Mena in 1752 and Antonio Pérez Aguilar in 1764.68

The term “pintorería” came into use in the second half of the eighteenth century.69 In his 1964 article that sampled four years of padrón records, historian Salvador Cruz defined a pintorería as a location selling paintings but not necessarily making them on site.70 Further analysis reveals that it was a broad, catchall phrase for workshops that produced or sold paintings of a wide variety. For example, period newspaper advertisements used pintorería for shops that painted carriages, furniture, and textiles.71 While these types of workshops have historically fallen outside the scope of art historical inquiry, this distinction postdates the padrones, which treated all simply as painters. The padrones listed pintorerías of known guild painters, mostly those who Manuel Toussaint labeled as popular or secondary artists.72 These included Eusebio Carrillo in 1754,73 Juan Gallardo in 1756,74 painter and gilder Sylvestre Reynoso in 1762,75 Gabriel Canales in 1762,76 Miguel de Herrera in 1770,77 Antonio Delgado in 1778,78 and Mariano Guerrero in 1805.79 Padrón records also place multiple painters who have yet to emerge from the archival record in pintorerías. These undoubtedly included painters of fabrics and furnishings, exvotos, and perhaps even house painters as well as the indigenous artists the guild permitted to paint “landscapes, flowers, fruits, animals and birds, and grotesques” without oversight.80

Establishing this vocabulary associated with male painters and their shops permits seeing painting shops run by women, which were described in the same terms. In most cases, conventions for padrón documentation reveal these women as widows accompanied by their children.81 Although not explicitly outlined in the Mexican painters’ guild ordinances, many trades allowed widows to maintain their husbands’ workshops, at least for a while (González Angulo Aguirre 1983, p. 41). In fact, Guadalupe Ramos de Castro writes in the context of artistic production in Spain, “widowhood seems to be the ideal state for women to exercise professional functions related to art, at least with full freedom.” (Ramos de Castro 1997, p. 170). Therefore, it may have been the case that widows of Mexican painters of all types did likewise.

And there were many of them. In 1733, on the street running in front of the Church of the Santísima Trinidad, Doña María Gertrudis Osorio appears as head of household under the padrón heading “Pintor” with her children Isabel Maria de Suazo, Juan Manuel Suazo, and José Domingo Suazo, and a servant or apprentice named Teodora Rosalia.82 In 1754, a pintorería was listed on calle del Espiritu Santo occupied and operated by Michaela Gonzalez with María Roldán and Manuel Roldán, presumably her children, as fellow occupants.83 A 1756 entry on calle de Monterilla lists another pintorería occupied by Gertrudis García with two unnamed family members, meaning children too young for the padrón.84 Five years later, an “accesoria de pintor” run by Josepha Maldonado and six unnamed family members operated on the same street.85 “Accesoria de pintor” was also used to describe the shop on calle de Balbanera run by Margarita García in 1757 and the business Antonia Agustín ran with her four children on calle Amor de Dios in 1761.86 That these women were likely widows running painting businesses established by their husbands is confirmed by a 1764 padrón entry that identifies the “Accesoria Pintor” near the corner of Arsinas and San Sebastián as belonging to “viuda Doña Magdalena Pardo” accompanied by four unnamed family members.87

A 1757 entry on the callejón de la Rinconada on Mexico City’s southeast side introduces a different type of household and shop. Here, under the heading “Accesoria Pintores” the parish priest listed Juana Montes de Oca with three unnamed children. She was accompanied at the shop by Doña Josefa de la Barrera, also with three family members, likewise presumably children.88 Like Augustina Meza and her sisters, these women apparently merged households to pool resources as examples of the domestic cohabitation groups studied by Gonzalbo. Similarly, two unrelated women—Josefa Herrera and Mariana Marín—shared an “Accesoria Pintor” on calle Amor de Dios in 1758.89 Like all the others listed here, no known works have been attributed to them in colonial art historiography.

It is, of course, inappropriate to assert that the women at the helm of pintorerías and accesorias de pintor were artists who toiled anonymously and accounted for some of the vast array of anonymous paintings—easel paintings, frescoes, ex-votos, decorative arts, and textiles—made in the eighteenth century.90 Isolated references in the padrón do not sufficiently support this hypothesis even when well-known male painters were listed in exactly the same way. But the padrones raise the possibility that some were, as perhaps demonstrated by a 1768 entry from Mexico City’s Veracruz parish that lists a residence belonging to “unas pintoras” on calle de San Juan.91 If they were fine art easel painters, these unnamed women may have worked outside the guild system. Guadalupe Ramos de Castro has determined that women artisans working in Spain were routinely excluded from guild rosters if their husbands were members.92 This would also include the widows of non-guild, Amerindian artists. This may be how Efigenia Hidalgo could appear under the rubric “pintor” in the 1743 padrón.93 Records from the Sagrario parish reveal that she was the widow of Felix del Espíritu Santo Zacarías, an indigenous man who she married at Ixtacalco in 1737.94 The couple produced children Joachín and Félix Zacarías, who were counted in her household in the 1743 padrón. Other women-run painting shops may have avoided guild restrictions by not producing easel paintings of religious themes. Or they may even have operated some of the illegal painting workshops about which a cadre of painters and printmakers complained to the viceroy in 1753.95

It is unfortunately difficult to even imagine these women as painters since a history of women artists in viceregal Mexico City has yet to be written. The earliest woman painter may have been Isabel de Ibía, the wife of painter Baltasar de Echave Orio and daughter of painter Francisco Zumaya. At the end of the viceregal era, noblewoman María Guadalupe Moncada y Berrio painted at the Royal Academy of the Three Noble Arts of San Carlos, which named her honorary academician. Throughout the colonial period, nuns anonymously drew and painted manuscript illustrations and mural paintings for their convents, just as they embroidered sacred ornaments.96 Nonetheless, there were certainly others, as there were in Spain during the early modern period: aristocratic amateurs like Catalina de Mendoza and the Marquesa de Villafranca, Tomasa Palafox; and daughters of artists like Isabel Sánchez Coello, Luisa Roldán, and Ana María Mengs.97 The Mexican padrón records are at the very least sufficient to demonstrate that Meza was not alone in her engagement with commissioning, manufacturing, and selling works of art as a woman in late colonial Mexico City; whether others additionally made art as Meza did remains to be seen.98

Perhaps, then, this explains why the Inquisition paid no attention to Meza’s emphatic declaration of her gender on the engraving of Christ and the Apostles. In a city with plenty of women-run art businesses, Meza’s gender was not an issue. Whatever the case, tracing padrón records for these women as we did for Augustina Meza’s history with her print publishing shop cracks the door into the world of women in the painting profession. It certainly supports that at the very least the women listed in the padrones at painting workshops managed the shops and were, therefore, like Augustina Meza and intimately involved in the business of art in viceregal Mexico City.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks Alena Robin and Lauren Beck for their invitation to submit to this special issue. She also thanks the anonymous reviewers who offered insightful and constructive feedback on the manuscript. All images used in this article are in the public domain, with sources of the photographs acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Archive General de la Nación, México.- Inquisición, vol. 1079, exp. 1

- Inquisición, vol. 1180, exp. 9

- Inquisición, vol. 1208, exp. 28

- Inquisición, vol. 1521, exp. 9

- Padrones, vol. 52

Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano, México. Available at familysearch.org.- Bautismos de españoles 1764–1769

- Bautismos de españoles 1769–1774

- Bautismos de españoles 1809–1813

- Censos 1733–1739

- Censos 1743–1752

- Censos 1752–1755

- Censos 1756–1760

- Censos 1761–1765

- Censos 1768–1769

- Censos 1772–1776

- Censos 1777

- Censos 1778–1780

- Censos 1785–1787

- Censos 1788–1792

- Censos 1793

- Censos 1797

- Censos 1797, 1801

- Censos 1802–1805

- Censos 1806–1813

- Defunciones de españoles 1767–1779

- Defunciones de españoles 1789–1797

- Defunciones de españoles 1809–1815

- Matrimonios de castas 1715–1745

- Matrimonios de españoles 1765–1766

- Matrimonios de españoles 1803–1815

El Aviso (La Havana). 23/7/1809, no. 88, page 3; El Aviso (La Havana). 10/10/1809, no. 122.Diario de México 27/1/1806, vol. 2, no. 119.Gazeta de México, vol. 8, number 3, Oct. 28, 1797.Santa Veracruz, México. Available at familysearch.org.- Bautismos de españoles 1754–1772

- Padrones 1768

Secondary Sources

- Alcalá, Luisa Elena. 2014. Painting in Latin America 1550–1820: A Historical and Theoretical Framework. In Painting in Latin America. Edited by Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathon Brown. London: Yale University Press, pp. 15–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bargellini, Clara. 2006. Consideraciones acerca de las firmas de pintores novohispanos. In El Proceso Creativo. Edited by Alberto Dallal. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, pp. 203–22. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Cabrera, Luz del Carmen. 2014. Mujeres impresoras del siglo XVIII novohispano en México. Fuentes Humanísticas 27: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Stephanie. 1974. Patrons, Clients, and Kin in Seventeenth-Century Caracas: A Methodological Essay in Colonial Spanish American Social History. The Hispanic American Historical Review 54: 260–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, Magali. 2003. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Painting. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Morales, Efraín. 1990. Cayetano de Sigüenza: Un arquitecto novohispano del siglo XVIII. In Santa Prisca Restaurada. Edited by René Taylor and Javier Wimmer. Mexico: Instituto Guerrerense de Cultura, pp. 127–49. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, Paul. 1991. The Implications of Godparental Ties between Indians and Spaniards in Colonial Lima. The Americas 47: 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Salvador. 1964. Algunos pintores y escultores de la ciudad en el siglo XVIII (Según padrones del Sagrario Metropolitano. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 9: 103–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. 2000. Prints and Printmakers in Viceregal Mexico City, 1600–1800. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. 2006. Publishing Prints in Eighteenth-Century Mexico City. Print Quarterly 23: 134–54. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Forthcoming. La red profesional de imprentas de estampas y grabadores mexicanos entre los siglos XVIII y principios del siglo XIX. In Actas del Simposio de Historia y Cultura Visual del Congreso Internacional Virtual 21. México: Ediciones Ariadna.

- Flint, Shirley. 2013. No Mere Shadows: Faces of Widowhood in Early Colonial Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garone Gravier, Marina. 2020. Herederas de la letra: Mujeres y tipografía en la Nueva España. In UnosTiposDuros. Available online: https://www.unostiposduros.com/herederas-de-la-letra-mujeres-y-tipografia-en-la-nueva-espana/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Garone Gravier, Marina, and Albert Corbeto López. 2011. Huellas invisibles sobre el papel: Las impresoras antiguas en España y México (siglos XVI al XIX). Locus: Revista de Historia 17: 103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de Zamora Sanz, Alba. 2018. Mujeres y talleres de arte en la España del Siglo de Oro. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar. 2016. Los Muros Invisibles: Las Mujeres Novohispanas y la Imposible Igualdad, Ebook ed. Mexico City: Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- González Angulo Aguirre, Jorge. 1983. Artesanado y Ciudad a Finales del Siglo XVIII. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Halcón, Fátima. 2001. El artista en la sociedad novohispana del barroco. In Actas del III Congreso Internacional del Barroco Iberoamericano. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide, pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Katzew, Ilona. 2014. Valian Styles: New Spanish Painting, 1700-85. In Painted in Latin America. Edited by Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathan Brown. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 149–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lavín González, Daniel. 2018. Mujeres artistas en España en la Edad Moderna: Un mapa a través de la historiografía española. Anales de Historia del Arte 28: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Serrano, Matilde. 1976. Presencia Femenina en las Artes del Libro Español. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española. [Google Scholar]

- Mazín, Oscar, and Esteban Sánchez de Tagle, eds. 2009. Los “Padrones” de Confesión y Comunión de la Parroquia del Sagrario Metropolitano de la Ciudad de México. Mexico City: Colegio de México/Red Columnaria. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz López, Pilar. 2016. Artistas precursoras en el arte español: De la edad media al siglo XVIII. In Mujeres de Letras: Pioneras en el Arte, el Ensayismo y la Educación. Edited by María Gloria Ríos Guardiola, María Belén Hernández González and Encarna Esteban Bernabé. Murcia: Región de Murcia, Consejería de Educación y Universidades. Available online: http://www.carm.es/edu/pub/20_2016/index.html (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Penyak, Lee. 2015. The Inquisition and prohibited sexual artwork in late colonial Mexico. Colonial Latin American Review 24: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Toledo, Sonia. 2005. Los Hijos del Trabajo: Los Artesanos de la Ciudad de México, 1780–1853. Mexico City: Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Poot-Herrera, Sara. 2008. El siglo de las viudas. Impresoras y mercadoras de libros en el XVII novohispano. Destiempos 3: 300–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Leyva, Edelmira. 1992. La censura inquisitorial novohispana sobre imágenes y objetos. In Arte y Coerción: Primer Coloquio del Comité Mexicano de Historia del Arte. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 149–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Montes, Mina. 2001. En defensa de la pintura. Ciudad de México, 1753. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 23: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramos de Castro, Guadalupe. 1997. La presencia de la mujer en los oficios artísticos. In VIII Jornadas de Arte. La Mujer en el aRte Español. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Históricos, pp. 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Romero de Terreros, Manuel. 1949. Grabados y Grabadores en la Nueva España. Mexico City: Arte Mexicano. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Javier. 2013. El grupo familiar de Juan Gil Patricio Morlete Ruiz, pintor novohispano. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 35: 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber de la Mora, Guillermo. 2019. Los conventos de la Nueva España del siglo XVII como espacios de desarrollo femenino: El caso del Convento de San Jerónimo de México. Sincronía 76. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/5138/513859856021/html/index.html (accessed on 2 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Manuel. 1990. Pintura Colonial en México, 3rd ed. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Murcia, Liliana. 2012. Del Pincel al Papel: Fuentes Para el Estudio de la Pintura en el Nuevo Reino de Granada (1552–1813). Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Susan Verdi. 2017. Lettered Artists and the Languages of Empire. Painters and the Profession in Early Colonial Quito. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, Martha. 1998. Jesuit Printing in Bourbon Mexico City: The Press of the Colegio de San Ildefonso, 1748–1767. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Third Provincial Council held in Mexico City in 1585 charged parish churches with completing an annual padrón or census of parishioners who had confessed. Upon confession, the parishioner was given the slip of paper and handed it over when the priest came calling each spring. These censuses were only required to count adults, although some priests counted children as well. The records are invaluable for the study of eighteenth-century Mexico City but should be approached critically. There are missing and mislabeled volumes in parish archives, priests sometimes skipped or misrepresented homes and businesses, and each cleric used a distinct approach to recording information. On the padrones of the Sagrario Metropolitano in Mexico City, including a CD with surviving documents, see (Mazín and de Tagle 2009). Padrón records also form part of the massive collection of documents photographed and made public by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at familysearch.org. |

| 2 | “Padrón del cumplimiento de Nuestra Madre Iglesia,” 1748 book 36, DVD in Los “Padrones” de Confesión y Comunión. This record appears in the DVD as 1748. The microfilm images at familysearch.org lists this padrón as 1806. “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-5B9Z-L1?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-N38%3A122580201%2C132131201: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1806–1813 > image 129 of 1240; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). Neither date is correct. The listed “cura interín” Colorado who collected the padrón was only in that position in the Spring of 1770 according to “De los Señores Curas del Sagrario Metropolitano de México,” Memorias y revista de la Sociedad Cientica “Antonio Alzate” 7 (1890): 313. Therefore, this padrón is 1770, not 1748 or 1806. All translations here of secondary sources and period newspapers are mine unless otherwise noted. Translations of extended passages from archival records are similarly mine. Signatures on plates and entries in archival records are left in the original Spanish or Latin. |

| 3 | (Romero de Terreros 1949, p. 490). I have found an additional five engravings signed by Gutiérrez, bringing his known oeuvre to twenty. |

| 4 | (Donahue-Wallace 2000, pp. 169–72; 2006, pp. 134–54). |

| 5 | This paper uses printmaking press and print publishing press interchangeably to refer to presses that exclusively or principally published printed images. This distinguishes them from typographic printers who also published prints but principally printed texts as well as from engravers who did not own presses. |

| 6 | Augustina Meza’s existence as a printmaker working in Mexico City was first published in Donahue-Wallace, “Prints and Printmakers,” 89. She does not appear in Romero de Terreros’s list of engravers, which mentions only an engraver named Meza who inscribed his plates with an address on Puente del Espíritu Santo. See Romero de Terreros, Grabados y grabadores, 499. My research reveals that this was Ignacio Meza, who was active in the 1760s. |

| 7 | For a fuller accounting of the print publishers in the padrón records, see (Donahue-Wallace, forthcoming). |

| 8 | Each priest interpreted the padrón process differently. Some noted spouses, others did not. In general, the first two names listed at a location are the husband and wife, followed by children (if named), and, finally, apprentices and servants. |

| 9 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-5LHL-M?cc=1615259&wc=3P62-L2S%3A122580201%2C141438601: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Matrimonios de españoles 1765–1766 > image 82 of 887; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). Neither of the couple’s ages is provided in the document. Later in life, Augustina Meza provided an age that would put her birthdate in 1758. This was likely an error since she would have been just seven years old at her wedding. It is likely that she was the more common marriage age of 15, making her birthdate somewhere around 1751. |

| 10 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-616P-DV?cc=1615259&wc=3PXD-GP8%3A122580201%2C128296901: 20 July 2015), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Bautismos de españoles 1764–1769 > image 590 of 1028; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 11 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6RQ9-TD9?cc=1615259&wc=3PX4-DP8%3A122580201%2C128387602: 20 July 2015), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Bautismos de españoles 1769–1774 > image 348 of 1072; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 12 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R39D-9Y?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-16D%3A122580201%2C131827401: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1768-1769 > image 817 of 2253; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). Earlier padrones do not include any other presses on the block, suggesting that the Gutiérrez/Meza shop opened sometime just before or in early 1768. |

| 13 | On these presses, see Donahue-Wallace, “Publishing Prints.” |

| 14 | This new information comes from a baptismal record. See “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-X919-NNX?cc=1615259&wc=3PX6-BZ9%3A122652201%2C124949001: 20 July 2015), Santa Veracruz (Guerrero Sureste) > Bautismos de españoles 1754-1772 > image 220 of 1010; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 15 | Juan Joseph Naxera is an example. In 1768, he testified before the Inquisition that he worked at the print publishing shop belonging to Joseph Mariano Navarro. See Donahue-Wallace, “Prints and Printmakers,” pp. 163–64. |

| 16 | See Donahue-Wallace, “Publishing Prints,” for a description of the industry in the mid- to late-eighteenth century. Prior to the 1740s, single artists monopolized the profession including Samuel Stradanus in the early seventeenth century and Antonio de Castro in the late seventeenth century. |

| 17 | Susan Verdi Webster’s study of painting in Quito serves as a case in point. Although quiteño painters lacked a guild, they nevertheless followed informal, self-regulated practices, including “leadership of family or community workshops,” that resulted in professional hierarchies, designation as master, and collaborations amongst the artists themselves. This appears to be the case among Mexico City’s printmakers and print publishers as well, and the trade operated without governmental oversight. Webster also suggests that the low cost of Quito’s paintings kept the profession from oversight by the city’s cabildo. If true, the same would certainly apply to Mexican printmaking. See (Webster 2017, pp. 77, 79). |

| 18 | On the use of the label Spanish within New Spain’s caste system, see (Carrera 2003). Racial categories were more flexible than the caste system hierarchy suggests. When engraver Juan Joseph Naxera married his wife in 1765, he was listed as a mestizo. See “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939D-8Y99-9J?cc=1615259&wc=3P83-7M3%3A122652201%2C132499901: 20 May 2014), Santa Veracruz (Guerrero Sureste) > Matrimonios de castas 1729-1777 > image 619 of 978; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). By the time he testified before the Inquisition in 1768, however, his calidad had changed to Spanish, likely due to his improved wealth rather than a change in race. See Archivo General de la Nación (hereafter AGN), Inquisición, vol. 1521, exp. 9, fol. 268. |

| 19 | “Padrón del cumplimiento de Nuestra Madre Iglesia,” 1721, libro 18 in CD accompanying (Mazín and de Tagle 2009). The date of this book is incorrect. The priest who collected the data, Joseph Ramírez, did not arrive at the Sagrario until 1732. This and other evidence derived from the parishioners listed leads me to conclude that the padrón is from 1747. On Troncoso and Zapata, see Donahue-Wallace, “La red profesional de imprentas de estampas,” n.p. |

| 20 | The 1746 padrón identified Francisco Sylverio, his wife, two daughters, and apprentice, Augustín Saenz. “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-RM97-YH?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-T38%3A122580201%2C131669001: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1743-1752 > image 102 of 935; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). Six years later, Sylverio’s household included a different apprentice, Mariano Moreno. “Padrón del cumplimiento de Nuestra Madre Iglesia,” 1752, libro 42 in CD accompanying (Mazín and de Tagle 2009). Similarly, the 1753 census demonstrates that engraver and “impresor” Antonio Moreno had an apprentice at his home, although this young man may have apprenticed for instruction in silversmithing rather than printmaking. See AGN Padrones, vol. 52, fol. 50v. The Royal Mint similarly employed apprentices to train in its Oficina del grabado in preparation for careers engraving coins and medals. |

| 21 | These were the two major print publishing shops during Gutiérrez’s youth. Based on his habit of adding a long swash to the left side of the letter T, Gutiérrez most likely trained with Baltasar Troncoso y Sotomayor, who frequently used the same idiosyncratic flourish at his shop on calle del Hospicio. |

| 22 | See Donahue-Wallace, “Prints and Printmakers,” p. 159. |

| 23 | Father-to-daughter training was not unheard of in the eighteenth-century Spanish empire. In fact, royal engraver Tomás Francisco Prieto trained his daughter María de Loreto Prieto to engrave. She, like Meza, married an engraver: Pedro González de Sepulveda, who also trained with her father. See (López Serrano 1976, p. 28). |

| 24 | AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1079, exp. 1, fols. 1–11. This Inquisition investigation and notification is discussed in Donahue-Wallace, “Prints and Printmakers,” pp. 169–73. On the Mexican Inquisition and its investigations of works of art, see (Ramírez Leyva 1992, pp. 149–62; Penyak 2015, pp. 421–36). |

| 25 | AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1079, exp. 1, fol. 4-4v. |

| 26 | AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1180, exp. 9, fols. 211–229. |

| 27 | AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1180, exp. 9, fol. 228. |

| 28 | The academy’s founder, the engraver Jerónimo Antonio Gil, did not use “don” on his plates but did in his correspondence. Even after Fabregat arrived, his students only rarely placed “don” before their names. |

| 29 | See López Serrano, Presencia, p. 25. |

| 30 | Romero de Terreros, Grabados y grabadores, p. 490. |

| 31 | The image was published by Manuel Romero de Terreros in 1949 but its current location is unknown. While Romero de Terreros, Grabados y grabadores, p. 529 identifies an engraver named Francisco Antonio Rubio in his study of colonial printmaking, parish records reveal that the engraver responsible for these two works was Augustín Rubio. |

| 32 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R8TC-V?cc=1615259&wc=3P6R-T38%3A122580201%2C133112301: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Defunciones de españoles 1767–1779 > image 254 of 953; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 33 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-6RQ9-TD9?cc=1615259&wc=3PX4-DP8%3A122580201%2C128387602: 20 July 2015), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Bautismos de españoles 1769–1774 > image 348 of 1072; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 34 | Castro Morales, “Cayetano de Sigüenza,” p. 138. The family residence is found in “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R9W9-Z?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-BZS%3A122580201%2C131752901: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1761–1765 > image 784 of 1204; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 35 | In 1768, when the Inquisition notary made his notification to the city’s presses and stopped at the “imprenta de estampas de Cayetano Sigüenza” on the same day he visited Gutiérrez, it was José Aduna, “the person who runs it,” who signed the record. AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1079, exp. 1, fol. 4v. |

| 36 | On compadrazgo, see (Blank 1974; Charney 1991). As Blank, “Patrons,” 262, writes, “through compadrazgo, members of the second and third estate could gain access to this concentration of wealth and power.” |

| 37 | Castro Morales, “Sigüenza,” 133. Cabrera y Quintero’s text described in the 1737 plague that ravaged Mexico City and led to the Virgin of Guadalupe’s selection as patroness of Mexico City. |

| 38 | This strategic padrinazgo relationship was short-lived, however, as Cayetano Sigüenza died in 1778. |

| 39 | Since the colonial system of compadrazgo sometimes included loans between the parties, it is possible that Sigüenza helped to finance Meza’s new shop. |

| 40 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-RS97-6?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-16D%3A122580201%2C131827401: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1768–1769 > image 2168 of 2253; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal) and “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R4F3-T?cc=1615259&wc=3P6P-N38%3A122580201%2C131909301: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1772–1776 > image 138 of 1077; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 41 | Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Los muros invisibles, locations 1768 and 3580. |

| 42 | To get a sense of the demand for prints, Martha Whittaker’s study of the press at the Jesuit Colegio de San Ildefonso, which had one tórculo for engraved images, reveals that in its last nine months of operation before the 1767 expulsion, the press printed 8152 printed images. These included 5017 for lay customers and 3135 for Jesuit clergy. See Whittaker, “Jesuit Printing,” p. 109. Although without an inventory of the estate we cannot know precisely what Gutiérrez’s estate included, the record of Sigüenza’s 1763 purchase of Sylverio’s print publishing business—although this was likely much larger than Meza’s—provides a point of reference. The retiring engraver sold Sigüenza 541 engraved plates, ranging in size from folio to sextodecimo. It also included three tórculos or intaglio presses and three common presses. See Castro Morales, “Cayetano Sigüenza,” p. 138. |

| 43 | Beltrán Cabrera, “Mujeres impresoras,” pp. 16–17. |

| 44 | Beltrán Cabrera, “Mujeres impresoras,” p. 19. |

| 45 | The same was true for Spain. On women printers in Spain and New Spain, see (Garone Gravier and López 2011). |

| 46 | Garone Gravier, “Herederas de la letra,” np. |

| 47 | Residents of cities without such robust printmaking communities used intermediaries to commission prints in Mexico City. |

| 48 | Augustín Rubio’s birth record at the parish of the Church of the Veracruz in Mexico City reveals that he was 24 years old at the time of the marriage. The groom identified himself as the son of Francisco Rubio, perhaps proving Romero de Terreros’s identification of Francisco as an engraver. His son likely trained at his side. That Meza married an engraver similarly points to the guild-like behaviors of the industry. The ordinances of several Mexican guilds demanded that in order for a widow to continue operating the shop she inherited from her husband, she must hire or marry a guild official or master. |

| 49 | The reworking and exchange of plates between print publishing firms has yet to be studied. Current research reveals, however, that plates were regularly refreshed for new states. Likewise, engraved plates frequently moved between engravers and presses, including examples like this one that was worked on by at least three separate engravers. See Donahue-Wallace, “La red profesional de imprentas de estampas,” n.p. |

| 50 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R78F-2?cc=1615259&wc=3P6P-923%3A122580201%2C122894201: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1777 > image 337 of 588; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 51 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-RMQB-T?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-L29%3A122580201%2C132011501: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1785–1787 > image 591 of 1024; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 52 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-51NT-Z?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-VZ3%3A122580201%2C132040101: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1788–1792 > image 362 of 727; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 53 | AGN, Inquisición, vol. 1208, exp. 28, fol. 344. The print was included in an investigation of prohibited books but appears not to have been discussed by the Inquisitors. |

| 54 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-R6CC-9?cc=1615259&wc=3P6Y-6TG%3A122580201%2C133141501: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Defunciones de españoles 1789–1797 > image 87 of 760; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 55 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-55J7-1?cc=1615259&wc=3P62-16D%3A122580201%2C132056601: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1793 > image 271 of 725; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 56 | Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Muros invisibles, location 2192. |

| 57 | Gazeta de México, vol. 8, number 3, Oct. 28, 1797, p. 356. |

| 58 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-55N3-B?cc=1615259&wc=3P62-168%3A122580201%2C132073801: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1797, 1801 > image 755 of 1001; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). Indians were not supposed to live in the central core of the city, but this was quickly abandoned and the padrones of the mid- to late-eighteenth century routinely counted native residents. |

| 59 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-RHQX-4?cc=1615259&wc=3P6P-16F%3A122580201%2C132101401: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1802–1805 > image 478 of 1160; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |

| 60 | “México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos, 1514–1970,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-513M?cc=1615259&wc=3P6L-N38%3A122580201%2C132131201: 20 May 2014), Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) > Censos 1806–1813 > image 680 of 1240; parroquias Católicas, Distrito Federal (Catholic Church parishes, Distrito Federal). |