Abstract

It has been said that the ancient Egyptians were raised to tolerate all kinds of toil and hardship; they nevertheless also liked to amuse themselves with comic relief in their everyday life. For example, ancient Egyptian drawing can be quite accurate and at times even spirited. What scholars have described as caricatures are as informative and artistic as supposed serious works of art. Ancient Egyptians have left countless images representing religious, political, economic, and/or social aspects of their life. Scenes in Egyptian tombs could be imitated on ostraca (potsherds) that portray animals as characters performing what would normally be human roles, behaviors, or occupations. These scenes reveal the artists’ sense of comedy and humor and demonstrate their freedom of thought and expression to reproduce such lighthearted imitations of religious or funeral scenes. This paper will focus on a selection of drawings on ostraca as well as three papyri that show animals—often dressed in human garb and posing with human gestures—performing parodies of human pursuits (such as scribes, servants, musicians, dancers, leaders, and herdsmen).

1. Introduction

Depictions of animals in scenes of daily life are commonly found in ancient Egyptian tombs, mainly the Old Kingdom mastabas and the rock cut tombs of the New Kingdom (Evans 2000, p. 73; Germond and Livet 2001, p. 7). Egyptians carefully studied animals, understood their physical characteristics, and admired their nature. Animals that were dangerous or had powers human beings lacked were especially respected. To be sure, many deities of the Egyptian pantheon we represented fully or partially as animals—often with an animal’s head (te Velde 1980, pp. 76–82). In addition, Egyptians represented animal genera accurately in their hieroglyphic signs (McDonald 2009, p. 361; Germond and Livet 2001, p. 107). Modern scholars have divided Egyptian hieroglyphs into some 25 categories, ranging from depictions of people, animals, and plants to those of common objects. Among about 700 hieroglyphs, about 170 take their inspiration from the animal kingdom (Germond and Livet 2001, p. 110). Animals were sacrificed, hunted, tamed, and raised, but also venerated and mummified. They served as a source of nourishment, a means of transportation, a source of medical remedies, companions, and objects of worship (Betz 2015, p. 22). One example of animal representation is imagery of animals performing human professions found in New Kingdom papyri and ostraca.1 These animals are clearly depicted to have unusually human mannerisms. They are also portrayed in ways that are not true to their own nature. This type of representation therefore anthropomorphizes animals (Babcock 2014, pp. 120–21). When compared to the more familiar formal representations on monuments of the majority of Egyptian “high” art, scholars have until very recently considered such scenes on ostraca and papyri of little artistic merit and academic interest—if they consider them at all.2

What these images could have meant to the ancient Egyptians is impossible to determine without written sources to elucidate their thoughts. This paper aims to shed light on the depiction of animals performing human professions on ostraca and papyri during the New Kingdom, focusing on a selection of drawings that show animals parodying human professions (such as scribes, servants, musicians, dancers, leaders, and herdsmen). These scenes often portray animals dressed in human clothes, posing with human gestures, and engaging in human pursuits. I will differentiate “humor,” “satire,” and “parody” to provide a better understanding of the comic intent of the artists. I will discuss why these scenes were drawn without any texts. Additionally, I will address the question of whether these drawings were indeed meant to mock elite society.

Understanding the exact meaning of these scenes is challenging due to the lack of supporting archaeological or textual evidence. These images are not quite understood because of the lack of knowledge of the cultural habits of the ancient Egyptians; such knowledge would have shed light on what these anthropomorphized animal behaviors mean. Another problem is that the exact findspot (called “provenance” or “provenience” in specialist circles) of the ostraca and papyri is often unknown—a problem more generally facing Egyptian artefacts dispersed to various institutional and private collections in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Had the findspot been known for all the drawings in question, it would have been possible to relate them to one another (Babcock 2014, p. 1).

2. The Artists of Deir el-Medina

During the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1078/77 bce), Egyptian artists living in a village near the Valley of Kings drew sketches based on existing monuments. This village, called “The Place of Truth” (S.t Ma῾at) at the time, is now commonly known by the Arabic name Deir el-Medina (“Monastery of the Town”), and is located on the Western Bank of the Nile across from Thebes (present-day Karnak and Luxor).3 Enlarged in the Ramesside Period (19th and 20th Dynasties), the village was inhabited by successive generations of workmen and their families until the beginning of the so-called Third Intermediate Period (Wilkinson 2005, p. 63). Workmen of different talents living in the village at the time normally numbered between forty and seventy (Redford 2001, vol. 1, p. 368). Among those workmen were carpenters, stonecutters, relief sculptors, and painters, who painted the royal tombs as well as their own tombs (Redford 2001, vol. 3, p. 8). They were, in other words, skilled craftsmen and often would work their entire lives on a single royal tomb. The workmen spent eight days of the Egyptian week camped near their work site in the Valley of the Kings (Yurco 1999, p. 247). On their days off and on holidays, they returned to the village, where their families resided (Yurco 1999, p. 248). Many of the inhabitants were literate, certainly the scribes. In addition to their everyday records, they left writings ranging from humorous satirical notes and sketches to pious religious inscriptions (Reeves and Wilkinson 1996, p. 20).

Serious themes were illustrated in Theban tombs that were copied at times on ostraca or papyri in a more light-hearted and less formal manner. In Egyptian fables, animals could appear as characters performing human roles, behaviors, or occupations. Ostraca scenes in particular provide a large number of these imitations of well-known themes found on tomb walls in which animals likewise replace human figures. The light-hearted drawings appear to parody or satirize human behavior. These scenes can be understood as a reflection of the humorous, comic spirit of the artists. They reveal the freedom of thought and expression to reproduce such comical works that imitate religious or funeral scenes. Drawings of this sort on ostraca or papyri are found in every sizable Egyptian collection (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 234). On average, ostraca are about the size of a human hand, though some papyri specimens are more than a meter in length (Houlihan 1996, p. 211). Artists used them for drafts in the planning of large murals and for sketches made while talking, or for taking notes. Pupils could use ostraca for painting exercises following models supplied by the tutors (Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 7). Because they were cheap (in fact, worthless), potsherds and limestone flakes were used in this manner from the beginnings of history until recent times and are found all along the Nile Valley (Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 1). Due to the dry conditions of the site, ostraca and flakes have been unearthed in great quantities, particularly at Deir el-Medina, and offer invaluable evidence of everyday life of the workmen and their families (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 234; Houlihan 1996, p. 211).

Apparently, some artists felt the desire to express themselves in a lighthearted manner. So, instead of using ostraca to jot down a note or figure an account, as did the scribes working in the area, they used them to draw images at their leisure to entertain themselves and their families (Scott 1962, pp. 152–53). Egyptian papyri contain images of satirical fables as well. To reiterate, the artists or artisans drawing these humorous scenes were the same workmen who built and decorated the tombs of the New Kingdom pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings, as well as the burial places of members of the royal family in the Valley of the Queens (Janssen and Janssen 1996, p. 8). Egyptian artisans thus display a freedom of imagination that is rarely seen in their official compositions in which their artistic talents were controlled by strict conventions of representation (Houlihan 1996, pp. 211–12). Free from these formal regulations, the artisans were not hampered by the inflexible instruments in their hands or the sturdy material in which official scenes were rendered (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 237). On the contrary, sherds, flakes, or papyri are easy to draw on and the brush is smooth. These conditions were adapted to sketching humorous or ludicrous episodes of daily life. The scenes they depicted appear unrelated to the formal images of Egyptian art (Malek 1993, p. 114). Their sketches are free of the conventions of “high” art in which professional gravity, propriety, and reputation were at stake (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 235). The satire expressed in the scene in question was eminently suited to the brush of the Egyptian artist, whose ability is particularly admirable in the portrayal of animals (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 236).

3. Defining Humorous Scenes

An important question to address is the purpose of the humorous or comical illustrations in question. They have been referred to as “caricature,” “comedy,” “humor,” “parody,” “satire,” and so forth. It might therefore be useful to clarify the difference between some of these terms.4 “Humor” is the ability of particular experiences to provoke laughter and provide amusement. Humor in jokes can thus be comic, absurd, incongruous, ludicrous, or otherwise funny. In ancient Egypt, humor was considered an element of common sense or even part of the kind of wisdom that places things in their correct or appropriate perspective (Luck 2000, p. 266). Humor has the capacity to undermine the normal decorum of society (Shaw and Nicholson 1997, p. 134).

From the ancient Greek song of revel, “comedy” now refers to visual or literary depictions of generally light and humorous characters engaged in amusing actions typically resulting in a happy ending. The word “caricature,” derived from the Italian caricatura, meaning to exaggerate a person’s characteristics, traits, and features, refers to drawings intended to poke fun at an individual. Although in origin designating humorous portraits of existing historical figures, by extension caricature may denote a comical, silly, derisive, grotesque, insulting, jokingly distorted, or critical depiction or description of a broader social phenomenon.

Although originating from the Latin word for “sated” (with food)—rather than the Greek satyr—“satire” can be defined as a form of criticizing, exposing, or ridiculing someone or something by means of humor, irony, or exaggeration to reveal the stupidity, immorality, or vices of the person, idea, or situation, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and public debates (Brunner-Traut 1984, p. 489). A “parody” can be described as a work of literary or visual art intentionally imitating another serious work of art, performance, situation, or genre, often with a deliberate exaggeration for comic effect. It may involve humor, burlesque, satire, or irony. In other words, a parody falls short of the real thing, and can thus be considered a travesty.

It should be clear, therefore, that most of these terms shade into each other, as their definitions are mostly circular. Still, satire should be seen as a serious artistic or symbolic expression of criticism through which individual, societal, or political faults and vices (shortcomings, stupidities, follies, weaknesses, abuses, or cruelties) are held up to censure by means of ridicule, derision, burlesque, grotesque, irony, or other methods, with an intent to bring about improvement; it does not always involve humor or comedy (Brunner-Traut 1984, p. 489; Rose 1993, pp. 80–81). In other words, satire contains an ethical, philosophical, or political purpose to educate, improve, and/or correct a societal ill. Its ultimate goal is to censure, criticize, or ridicule contemporary people, issues, and/or situations. Satire uses every resource, from laughter to indignation. In current usage, parody is a work created to mock, comment on, or make fun of an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satirical, or ironic imitation. In other words, parody is not necessarily critical and nearer to humor than satire (Brunner-Traut 1984, p. 489).

As Jennifer Babcock has recently pointed out, anthropomorphized animals have long been understood as examples of social satire, in which the lower class ridicules the social elite. Babcock, however, argues that these images should be understood as parodies—rather than satire—of elite iconography; and that the artists drawing these parodies considered themselves to be a part of the elite class. Indeed, they were represented in their own tombs at Deir el-Medina as members of the elite. Even if their wealth did not match that of the officials who are evidently part of the socio-economic elite class, the cultural sophistication of the Deir el-Medina artists sets them apart from the lower classes. Babcock rightly emphasizes that the artists drawing the anthropomorphized animals were clearly familiar with the numerous motifs found in elite and royal contexts that they parodied. They thus felt an intimate connection with elite culture (Babcock 2014, pp. 136–37). She is also correct that scenes of anthropomorphized animals cannot all be understood as expressions of social satire. Not all drawings reflect a reversal of the natural or social order, and much of the imagery may simply have been intended humorously.

David O’Conner likewise suggests that the Turin papyrus can best be designated as parody, mainly intended to provoke laughter at subjects that were understood by a sophisticated audience. According to O’Conner, the drawings are derived from topics on temple walls or paintings in tomb chapels, whereas the human section may have been inspired by certain “love-songs” (O’Connor 2011, pp. 362, 378–80). He thus refutes the interpretation of the drawings as satirical, stating that they do not ridicule individuals or aspects of classes or society and that it would be inappropriate to mock deities or disrespect kings (O’Connor 2011, pp. 362, 376–77).

Earlier, German Egyptologist Emma Brunner-Traut studied the images in question in great depth and understood them as illustrations of animal fables (Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 15). If that were true, though, one would expect text accompanying such scenes, at least in papyri. Yet, the hundreds of drawings bear no accompanying text. For his part, Christopher Eyre proposes that the figured ostraca and the Turin, Cairo, and British Museum papyri may have been used as storytelling aids for children (Eyre 2011, p. 177). His proposal explains why the drawings are not accompanied by texts, as children appreciate a visual image better than text. According to Patrick Houlihan, the illustrations on the three papyri mentioned above were likely drawn by artisans belonging to the group of at least forty percent of the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina that were literate, thus confirming their elite social status (Houlihan 2001, p. 62).

A set of stock characters and motifs seems to appear in these images of animals engaged in human activities (Babcock 2013, pp. 52–55). The aforementioned Brunner-Traut noted that the repetition of various figures, such as noble mice and servant cats, implies that they refer to now-lost stories or indeed fables (Brunner-Traut 1979, pp. 15–16). Perhaps these stories are not so much lost as that they were passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition, and were therefore never preserved in the literary evidence.5 Seen in this light, the interpretations of Brunner-Traut and Eyre would actually complement each other, in that the images represent stories passed down to children through storytelling.

Still, it should be emphasized that one of the main characteristics of Egyptian art is the combination of figures and inscriptions in the same scene, often leaving little empty space. Captions are added to give the names and titles of the tomb owner and his family members, or to indicate the activities he is observing or performing. Short phrases are also inscribed in front of the workmen, indicating the dialogues that took place between them at work. These inscriptions form an integral part of a scene and are essential for its understanding. They also tell us a great deal about the various steps of any task and about the language, the humor, and the different classes and professions.

Examining the images of animals on ostraca and papyri in their cultural context will offer a better understanding of their function and significance, and may provide clues about their meaning. The central question that remains despite generations of scholarly interest is why animals were depicted as humans, and for what purpose (Germond and Livet 2001, p. 210).

It might be beneficial for the reader to bear out the historical background in which these sketches were drawn. After the political and religious crisis of the 18th Dynasty under Akhenaten (r. ca. 1352–1335 bce) and Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1334–1325 bce), Egypt witnessed an age of prosperity and stability during the 19th Dynasty, founded by Ramesses I (r. ca. 1295/0 bce). It reached the height of its power during the long reign of Ramesses II (1279–1213 bce), when building programs were particularly active. The last powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom is generally considered to be Ramesses III (r. 1186–1155 bce), at the beginning of the 20th Dynasty. However, invasions from the west and north(-east) by land and sea, the volcanic eruption of Hekla on Iceland causing decades of poor air quality (ca. 1159–1140 bce), economic hardship recorded in Deir el-Medina by a workers’ strike, and corruption of sections of the administration, led to a general decline of central power. Respect for royal authority waned as the Theban tombs were robbed.

Against this backdrop, it is not difficult to understand drawings of animals ridiculing elite activities as expressions of bitter sarcasm toward the corrupt ruling elite unable to retain firm control over the beautiful Nile Valley. It is not impossible that they reflect contemporary economic, social, and political disorder. Is it not wiser to simply take these drawings at face value? Are they just amusing works of minor artistic worth, or are they biting satirical expressions of the dire conditions of the time at the dusk of the New Kingdom?

4. Selected Figures of Animals on Ostraca and Papyri

The preserved corpus of scenes depicting animals in human roles comprises drawings on 81 ostraca and three papyri held in private or institutional collections (Babcock 2014, p. 3). The preserved, though fragmentary, illustrated papyri form the core of this paper; they are held by museum collections in Cairo, London, and Turin. These fragments have come to be known as “satirical papyri,” for they all contain a series of drawings thought to illustrate fables or fairy tales featuring wild and domestic animals engaged in human behavior.

The themes are varied on the ostraca and papyri scenes depicting animals posing, dressed and acting as humans in ancient Egyptian art (Houlihan 1996, p. 212; Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 11). Still, Babcock notes that there are recurring motifs in the imagery, such as animals playing games, musicians at banquets, noble mice before an offering table, and pastoral scenes (Babcock 2014, p. 66). Although not necessarily the main theme, sometimes there was a kind of role reversal in the vignettes (Babcock 2014, pp. 5–6). For the present paper, the selected animals comprise cats, mice, lions, baboons, dogs and foxes, and donkeys. Birds are excluded here, as they require separate study. The majority of the figured ostraca in this study do not have a definite findspot. Some of them can be attributed to Thebes generally, or Deir el-Medina specifically.

Cats. The earliest evidence of a relationship between people and cats in Egypt dates back to Neolithic times (Germond and Livet 2001, p. 75). Cats appear in many ostraca scenes, especially together with mice. Cats seem to have been domesticated during the Middle Kingdom. They were both pets and symbols of feline deities, such as the goddesses Sekhmet and Bastet. The ancient Egyptian onomatopoeic word for cat is miw (𓏇𓇋𓅱𓃠). Jaromir Malek points out that scenes on the ostraca combine two main subjects (Malek 1993, pp. 115–16). The first is a refreshingly mocking view of the real world of the workers and the Theban tomb art. The other comprises the depictions of various animal characters, in particular cats, as seen in the paintings of the tombs of Deir el-Medina. As Raouf Habib comments, cats were the favorite animals of the Egyptian caricaturists, as they are by nature comical—indeed their haughtily independent character endows them with a sense of humor (Habib 1980, p. 2).

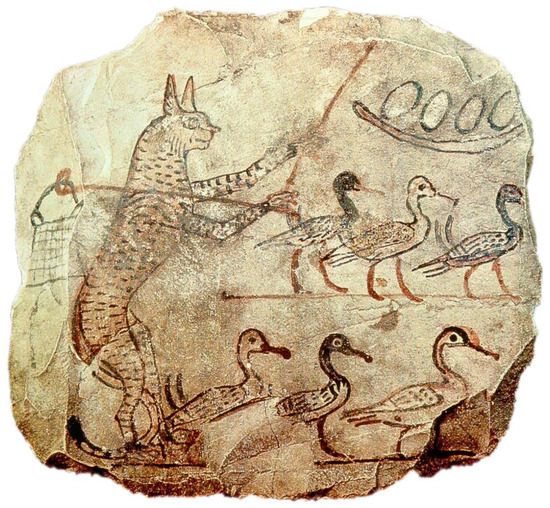

Perhaps the most famous and often-published ostracon depicting a cat shows an Egyptian tabby herding geese (Figure 1) (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, cat. no. 2266, pl. 39; Atiya 2005, p. 195; El-Shahawy 2005, p. 266, fig. 179). The scene is drawn in black, yellow, and red on a limestone flake from Deir el-Medina dating to the Ramesside period, and is now housed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The cat is standing on its hind legs, acting as a herdsman and protector of a gaggle of six geese, arranged in two registers. Above the geese is a nest filled with eggs. The tabby carries a small bag of provisions suspended from the end of a long crook, which it carries over its shoulder (Peck 1978, p. 56; Houlihan 2001, p. 82; Malek 1993, pp. 113–15; Houlihan 1996, p. 212; Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, pp. 54–55). The scene is a recurring pastoral motif, perhaps a cheerful episode from an Egyptian folktale or fable. In the episode not only does an animal perform a human activity here, but the roles of the natural world are also humorously reversed. It is possible that such a reversal scene, in which predator herds prey, also had a political satirical intent.

Figure 1.

Cat herding a flock of geese (EMC inv. no. JE 63801), limestone flake, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Image courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

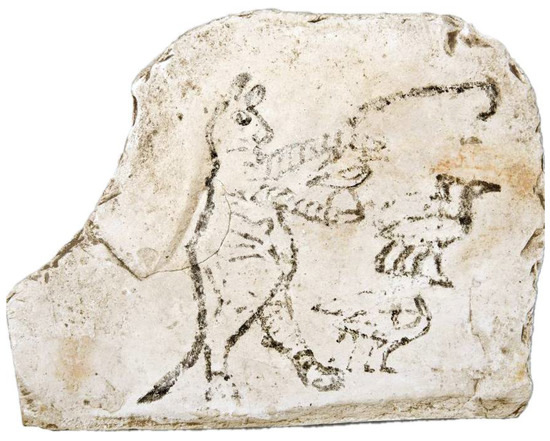

A similar sketch, now in the Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, is also drawn on a limestone flake in black (Figure 2; cf. Figure 14, right) (Atiya 2005, p. 195). To the (viewer’s) left of the scene is a striped cat, walking towards the right on its hind legs. In one paw, it holds a short, curved stick to goad a gaggle, and in the other, the tabby cradles a gosling to heighten the irony of the scene (Peck 1978, p. 144; Malek 1993, p. 120; Rogers 1948, p. 156; James 1985, p. 61; Houlihan 2001, pp. 65–66; Hambly 1954, pp. 267–68; Habib 1980, p. 3; Beauregard 1894, p. 205). To the right of the cat are four geese. Presenting animals performing human activities might have been a relatively safe means to censure and denounce the ruling elite at a time when the political order was weakened. That is to say, such reversal scenes may reflect a general loss of confidence towards the pharaoh and the country’s administration among the workers and artists, who might have felt that their world was turning upside down (cf. Figure 16, bottom left) (Atiya 2005, p. 195).

Figure 2.

Cat herding geese (MM inv. no. 14051), limestone flame, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Image courtesy of the Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm).

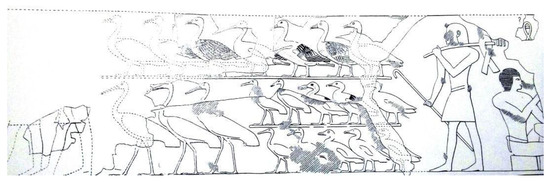

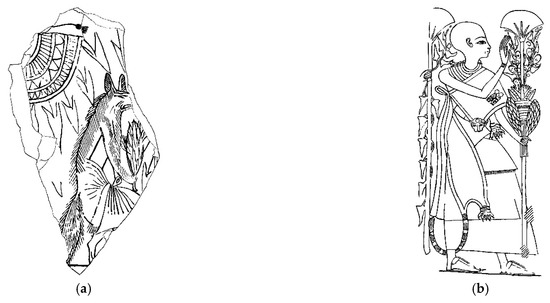

These ostraca sketches offer a parody of formal art depictions of human beings engaged in similar occupations. A pastoral scene in the tomb of Puyemra (Pwj m R‛), the Second Prophet of Amun (Theban Tomb no. 39), for example, shows a man leading large birds, including cranes, geese, and ducks (Figure 3).6 Here, the man on the right holds a shepherd’s crook in one hand and another stick over his shoulder. The various fowl are arranged in registers, similar to the ostraca scenes.

Figure 3.

Man leading large birds from the tomb of Puyemra (TT39), El-Khokha (Western Thebes), 18th Dynasty (Image taken from Davies and de Garis 1922, pl. 12).

An even more common imagery involving cats in anthropomorphized situations involves another theme of reversal, namely, the motif of a seated elite mouse being waited on by a servant cat.7 This motif appears on ostraca as well as the Cairo and British Museum papyri, and parodies countless funerary scenes of tomb owners being waited on by servants. A beautiful example, on a limestone ostracon of unknown findspot (now in Brooklyn), shows an anthropomorphized mouse seated on a folding stool to the right of the scene (Figure 4) (Babcock 2014, pl. 16). The mouse has drooping breasts and a round belly, wears a long dress, and has a lotus flower on her forehead; she holds a dish or cup in one paw, and fish bones or a flower as well as a piece of linen cloth in the other paw.8 Before her (to the viewer’s left), a tabby standing on its hind legs and tail pressed anxiously between its paws, holding a similar piece of cloth, waves a fan and offers a plucked and roasted duck or goose to the mouse.

Figure 4.

Cat serving seated mouse (Brooklyn Museum acc. no. 37.51E), limestone flake, findspot unknown (Egypt), Ramesside period (Photography by Gavin Ashworth, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, New York).

In this motif, the humorous element of animals imitating human behavior revolves, first of all, around the parody of banquet scenes frequently depicted in the Theban tombs. In those tomb scenes, the deceased is served his lavish banquet meal by female servants. The comic effect of animals acting out such banquet scenes is enhanced by reversing the natural animal order in which the predator serves the prey. Additionally, the mouse is generally understood as female and the cat as male, although admittedly the mouse may also portray an obese elderly official with drooping breasts and the cat’s gender is indeterminable.9 Still, another humorous level may then involve a reversal of gender roles, as the lady mouse is being served by a tom cat, instead of servant girls waiting on an elite man. Interpretations of these parodies of the funerary banquet scenes range from illustrations of a folk tale or fable, caricatures of the ruling elite, or actual satire of the royal family. If, as Babcock notes, the artists drawing these scenes felt an affinity with elite culture, it is difficult to see the imagery as biting satire of that same elite (Babcock 2014, pp. 21–22). Still, the comically topsy-turvy element of role reversal may well be a reflection of the uncertain times of the late New Kingdom—and thus voice ridicule at the failure of the ruling class to maintain justice and order (ma῾at).

A papyrus held in the collection of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, consisting of two painted vignettes, shows a comparable scene of mice being pampered by cats.10 Here, on the left are four cats serving a lady mouse at her toilet. Although she is not anthropomorphized to the extent of the preceding image, she is dressed in an ankle-length robe and sits on a tall, wicker stool with her feet on a footrest; she is sipping from a goblet handed over by a cat in front of her. Behind her, one of her servant cats is caring for her large wig. The cat even has its own small wig, held up with a hairpin. The next cat farther to the (viewer’s) right is gently carrying a baby mouse in a sling, just like a human nurse. The last of the four cats carries a jar of liquid and fans a large sunshade to wave cool air.

Mice. Ancient Egyptians called the mouse pnw (𓊪𓈖𓏌𓅱𓄛). Perhaps the largest group of comical scenes of animals imitating human behavior depicts mice. Apart from the scenes discussed above involving servant cats, mice are shown in toiletry scenes and military scenes (Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 11). In the former category, mice may be fanning a lady mouse, coiffing their own hair, or caring for their young carried in breast-shawls. In the military category, mice may be riding chariots, combatting enemies, or beating captives. A figured limestone ostracon sketched in red, black, and white depicts a mouse facing backwards riding a chariot drawn by two horses (Figure 5) (Brunner-Traut 1984, fig. 28; Houlihan 2001, pp. 84–85; Babcock 2014, p. 68–69, pl. 26). Wearing a pleated kilt decorated with a row of dots, the mouse holds the reins with one paw. In ancient Egypt, chariots were employed by kings and noblemen in war and races, and such scenes of mice imitating combat scenes must have been intended as witty parody (Brunner-Traut 1984, p. 489). The question remains whether such a parody also evokes an element of political satire in which the victorious king is paradoxically replaced by the small and weak mouse.

Figure 5.

Mouse riding chariot (MM inv. no. 14049), limestone flame, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Image courtesy of the Medelhavsmuseet, Stockholm).

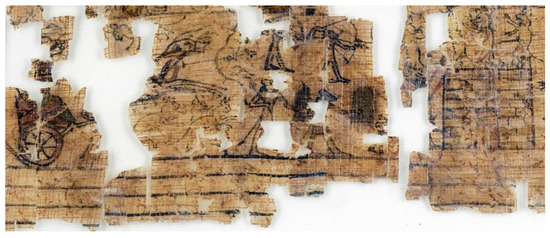

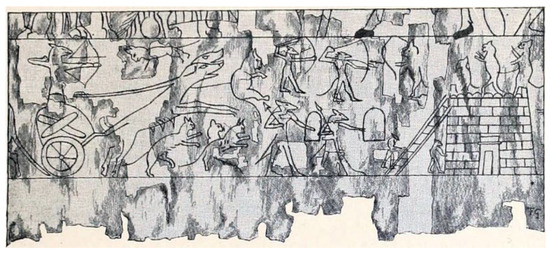

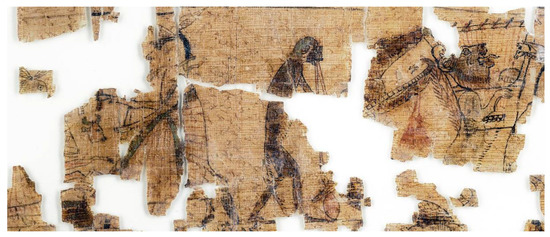

Other anthropomorphized combat scenes again involve cats and mice, now engaged in battle—often referred to as “The War of Mice and Cats” (Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 15). Stories about battles between cats and mice are known especially from the Near East (Brunner-Traut 1968, pp. 44–46), not to mention the Batrachomyomachia or “Battle of the Frogs and Mice,” from Classical Greek literature.11 A popular drawing of the cat-and-mouse war is found on the animal section of a large but highly fragmentary papyrus in Turin (Figure 6 and Figure 7; cf. Figure 16, bottom center).12 From the left of the scene a gigantic mouse charges on a chariot drawn by two dogs that trample a group of cats. Other mice are besieging a fortress, some with bow and arrows, others scaling the wall with a ladder defended by cats, who appear to be begging for mercy.13 The imagery is usually understood as an imitation or parody of monumental battle scenes such as those at Medinet Habu and the Ramesseum (Beauregard 1894, pp. 171–72; Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 72; Flores 2004, p. 235; Babcock 2014, pl. 11).

Figure 6.

War of Mice and Cats (detail of CME inv. no. c.2031, CGT no. 55001), papyrus, Deir el-Medina, 20th Dynasty (Image courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Turin).

Figure 7.

Reconstruction of the animal battle scene of Turin Papyrus 55001 (CME inv. no. C.2031) (Taken from Gaston Maspero, The Struggle of the Nations (London: S.P.C.K., 1896), p. 453).

Lions. The lion was called mAi or rw in ancient Egyptian (𓌳𓄿𓃬 or 𓃭𓏤). Although there were relatively few lions in Pharaonic Egypt, they played a significant role in royal ideology and religious symbolism, signifying strength, power, and majesty. Bold and magnificent, fierce and mighty, cruel and unpredictable, the lion was also uncharacteristically portrayed in human situations (Raven 2000, p. 71). On one of the humorous vignettes of a colorfully illustrated papyrus excavated at Deir el-Medina, a lion and gazelle are shown playing the board game called senet (lit. “passing”; Figure 8).14 The scene here is not a direct reversal or topsy-turvy situation, nor should the vignette be understood as an illustration of a folk tale; the humor lies in the pairing of predator and prey playing games as if they are friends rather than natural enemies.

Figure 8.

Lion and gazelle playing a board game (detail of BM reg. no. EA10016), illustrated papyrus, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Image courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London).

Depictions of humans engaged in a game of senet appear frequently in ancient Egyptian monuments. The details of the table and chairs, as well as the game pieces themselves, contribute to the charm of the parody. Some scholars—such as Raouf Habib and Jaromir Malek—have felt a hint of disrespect towards the nobility or the royal house (Habib 1980, p. 2; Malek 1993, p. 122; cf. Babcock 2014, pl. 25). For the parody recalls scenes such as the beautiful tomb painting of Queen Nefertari, the principal consort of Ramesses II, playing a game of senet against an invisible opponent (QV66), or Ramesses III playing the game with his court ladies in the temple at Medinet Habu. Even more so than the ostraca drawings, this masterful papyrus demonstrates that the artist painting these humorous vignettes belonged to the literary and cultured elite. With Babcock, we should note that the motif is not part of the standard royal funerary iconography, but rather belongs to elite funerary imagery (Babcock 2014, p. 67). The depiction of animals playing games should therefore best be understood as a witty parody of the stock scene of a man and wife playing senet, instead of sensing some socio-political critique (Peck 1978, pp. 144–46).

Baboons. In ancient Egyptian, the baboon was called ian (spelled variously  , vel sim.). They were popular as family pets, and indeed, many tomb scenes show baboons led on a leash, or playing with the children of the household. Baboons were also admired for their intelligence. They were trained to dance, sing, and play instruments for human entertainment; some were trained to pick figs (Houlihan 1996, pp. 106–7). Due to their anthropomorph appearance, and their cheerfulness and playfulness, artists were naturally inspired to place them in human situations (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 73). Monkeys appear in major and minor works of art playing various musical instruments together with other animals (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, pp. 57–58). They are also shown involved in other types of human activities (Redford 2001, vol. 2, p. 429). As baboons are represented dancing and playing instruments in religious scenes on the walls of major temples, such motifs cannot be understood as satirical (Houlihan 2001, p. 109, fig. 120; Babcock 2014, p. 116, pl. 56). Images of baboons and cats are related to the myth of Tefnut, and were likewise not intended as parodies (Brunner-Traut 1968, p. 34; Flores 2004, pp. 250–51; Babcock 2014, pp. 11, 108, and 112–14, pls. 46–50).

, vel sim.). They were popular as family pets, and indeed, many tomb scenes show baboons led on a leash, or playing with the children of the household. Baboons were also admired for their intelligence. They were trained to dance, sing, and play instruments for human entertainment; some were trained to pick figs (Houlihan 1996, pp. 106–7). Due to their anthropomorph appearance, and their cheerfulness and playfulness, artists were naturally inspired to place them in human situations (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 73). Monkeys appear in major and minor works of art playing various musical instruments together with other animals (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, pp. 57–58). They are also shown involved in other types of human activities (Redford 2001, vol. 2, p. 429). As baboons are represented dancing and playing instruments in religious scenes on the walls of major temples, such motifs cannot be understood as satirical (Houlihan 2001, p. 109, fig. 120; Babcock 2014, p. 116, pl. 56). Images of baboons and cats are related to the myth of Tefnut, and were likewise not intended as parodies (Brunner-Traut 1968, p. 34; Flores 2004, pp. 250–51; Babcock 2014, pp. 11, 108, and 112–14, pls. 46–50).

, vel sim.). They were popular as family pets, and indeed, many tomb scenes show baboons led on a leash, or playing with the children of the household. Baboons were also admired for their intelligence. They were trained to dance, sing, and play instruments for human entertainment; some were trained to pick figs (Houlihan 1996, pp. 106–7). Due to their anthropomorph appearance, and their cheerfulness and playfulness, artists were naturally inspired to place them in human situations (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 73). Monkeys appear in major and minor works of art playing various musical instruments together with other animals (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, pp. 57–58). They are also shown involved in other types of human activities (Redford 2001, vol. 2, p. 429). As baboons are represented dancing and playing instruments in religious scenes on the walls of major temples, such motifs cannot be understood as satirical (Houlihan 2001, p. 109, fig. 120; Babcock 2014, p. 116, pl. 56). Images of baboons and cats are related to the myth of Tefnut, and were likewise not intended as parodies (Brunner-Traut 1968, p. 34; Flores 2004, pp. 250–51; Babcock 2014, pp. 11, 108, and 112–14, pls. 46–50).

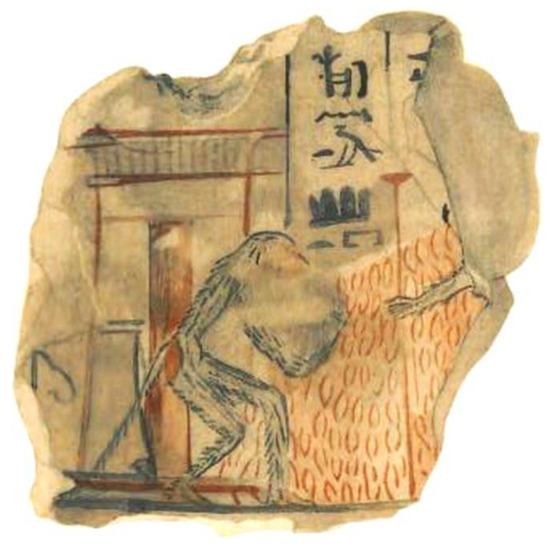

, vel sim.). They were popular as family pets, and indeed, many tomb scenes show baboons led on a leash, or playing with the children of the household. Baboons were also admired for their intelligence. They were trained to dance, sing, and play instruments for human entertainment; some were trained to pick figs (Houlihan 1996, pp. 106–7). Due to their anthropomorph appearance, and their cheerfulness and playfulness, artists were naturally inspired to place them in human situations (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 73). Monkeys appear in major and minor works of art playing various musical instruments together with other animals (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, pp. 57–58). They are also shown involved in other types of human activities (Redford 2001, vol. 2, p. 429). As baboons are represented dancing and playing instruments in religious scenes on the walls of major temples, such motifs cannot be understood as satirical (Houlihan 2001, p. 109, fig. 120; Babcock 2014, p. 116, pl. 56). Images of baboons and cats are related to the myth of Tefnut, and were likewise not intended as parodies (Brunner-Traut 1968, p. 34; Flores 2004, pp. 250–51; Babcock 2014, pp. 11, 108, and 112–14, pls. 46–50).A limestone fragment now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, depicts a baboon standing by a granary drawn in red and black (Figure 9) (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, cat. no. 2283, pl. 40). The monkey, on its hind legs, facing right, is eating from a mound of grain gathered beside the building. He has even made an inventory of a large pile of grain in front of him. Could the drawing be a depiction of Thoth, the god of writing, who was variously portrayed in the form of a baboon or an ibis (Germond and Livet 2001, p. 87)? To the (viewer’s) right of the partial scene, the forearm of another baboon is still visible, perhaps the master or overseer, holding a wadj-scepter (𓇅). Between the two monkeys are two vertical columns of hieroglyphic script (only the left is legible), reading sS n tA Snwty, “The Scribe of the Granary” (  ). The title suggests that the artist intended to express criticism of human nature in an amusing manner (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 58). For scenes of overseers inspecting the fields and storehouses while scribes inventory the produce are fairly common in tomb scenes of all periods, especially the New Kingdom. For instance, compare this ostracon to a scene from the tomb of Menna (TT69), where four men are depicted with containers scooping up grain, while six scribes record the event (Hodel-Hoenes 2000, p. 91; Hartwig 2013, p. 31). Three of the scribes are standing on the left, one is perched on a pile of grain, and two more are seated to the right. The joke on the ostracon, however, is not only that the scene parodies human occupations or scribes and overseers, but also that it adds the poignant observation of the baboon eating from the grain he has inventoried. The drawing may thus represent a commentary on human greed and corruption.

). The title suggests that the artist intended to express criticism of human nature in an amusing manner (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 58). For scenes of overseers inspecting the fields and storehouses while scribes inventory the produce are fairly common in tomb scenes of all periods, especially the New Kingdom. For instance, compare this ostracon to a scene from the tomb of Menna (TT69), where four men are depicted with containers scooping up grain, while six scribes record the event (Hodel-Hoenes 2000, p. 91; Hartwig 2013, p. 31). Three of the scribes are standing on the left, one is perched on a pile of grain, and two more are seated to the right. The joke on the ostracon, however, is not only that the scene parodies human occupations or scribes and overseers, but also that it adds the poignant observation of the baboon eating from the grain he has inventoried. The drawing may thus represent a commentary on human greed and corruption.

). The title suggests that the artist intended to express criticism of human nature in an amusing manner (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 58). For scenes of overseers inspecting the fields and storehouses while scribes inventory the produce are fairly common in tomb scenes of all periods, especially the New Kingdom. For instance, compare this ostracon to a scene from the tomb of Menna (TT69), where four men are depicted with containers scooping up grain, while six scribes record the event (Hodel-Hoenes 2000, p. 91; Hartwig 2013, p. 31). Three of the scribes are standing on the left, one is perched on a pile of grain, and two more are seated to the right. The joke on the ostracon, however, is not only that the scene parodies human occupations or scribes and overseers, but also that it adds the poignant observation of the baboon eating from the grain he has inventoried. The drawing may thus represent a commentary on human greed and corruption.

). The title suggests that the artist intended to express criticism of human nature in an amusing manner (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 58). For scenes of overseers inspecting the fields and storehouses while scribes inventory the produce are fairly common in tomb scenes of all periods, especially the New Kingdom. For instance, compare this ostracon to a scene from the tomb of Menna (TT69), where four men are depicted with containers scooping up grain, while six scribes record the event (Hodel-Hoenes 2000, p. 91; Hartwig 2013, p. 31). Three of the scribes are standing on the left, one is perched on a pile of grain, and two more are seated to the right. The joke on the ostracon, however, is not only that the scene parodies human occupations or scribes and overseers, but also that it adds the poignant observation of the baboon eating from the grain he has inventoried. The drawing may thus represent a commentary on human greed and corruption.

Figure 9.

Baboon feeding from heap of grain (EMC inv. no. JE 63799), limestone flake, Deir el-Medina, 19th Dynasty (Illustration taken from Vandier d’Abbadie (1937), pl. 40, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

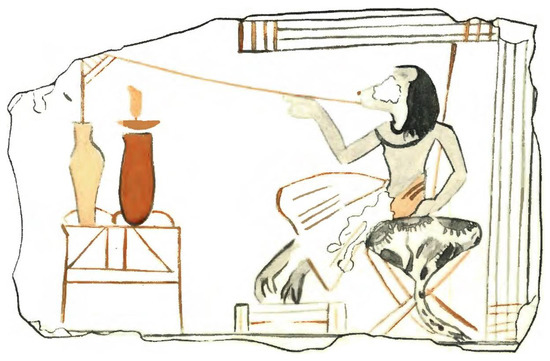

On a Deir el-Medina ostracon, drawn in black, dark red, pink, and green, another primate is portrayed as a nobleman (Figure 10); its species is indeterminable due to damage on its head (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 65, cat. no. 2315, pl. 48; Houlihan 2001, p. 75). He wears a rich dress and is sitting on a folding stool covered with cow hide, under the shade of a tent, with his feet on a footrest. The comedy here derives from the manner in which the figure is drinking from an amphora by means of a long tube. The scene might have been intended to ridicule the luxury and laziness of the nobility.

Figure 10.

Seated primate drinking from a tube (IFAO inv. no. 3263), limestone flake, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Line drawing taken from Vandier d’Abbadie (1937), pl. 48, courtesy of the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Cairo).

Dogs. Ancient Egyptians onomatopoeically called the dog iwiw, or iw for short (variously spelled 𓃛𓅱𓃡, vel sim.). Dogs were kept as pets and were given individual names, of which about eighty are known. They were often buried, embalmed, and mummified together with their masters and were portrayed in wall paintings (Evans 2000, p. 73). Dogs were appreciated as being trustworthy and loyal, good guards, and helpful trackers and hunters, and thus played meaningful roles in the lives of the ancient Egyptians. The funerary god Anubis was moreover worshiped in canine form (Germond and Livet 2001, p. 72).

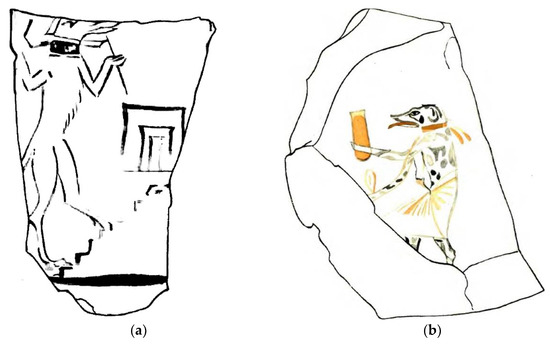

Two figured ostraca, both from Deir el-Medina and, like the previous, held in the collection of the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Cairo, depict dogs with an elegant sash tied around their neck (Figure 11) (Vandier d’Abbadie 1937, p. 65, cat. nos. 2316–17, pl. 48; Scott 1962, pp. 152–53; Malek 1993, p. 114; Houlihan 2001, p. 99). On one ostracon, drawn only in black, the dog climbs up a staircase on its hind legs, holding a kind of stick in one paw. To elucidate the scene, there is a small temple drawn in the back. The other limestone ostracon, drawn in black and dark red, depicts a similarly standing dog with a speckled coat, wearing a loincloth, and holding a vase or jug in one paw and a link or kerchief in the other. It is likely climbing steps to a temple, bearing offerings like its counterpart on the other scene. With Babcock it is important to note that the dogs are not engaged in sacrilegious behavior (Babcock 2014, p. 23). Still, depicting pious priests as dogs might express a sentiment of disrespect, perhaps revealing the hypocrisy of the priesthood.

Figure 11.

Dogs visiting a temple (IFAO inv. no. 3666 and no. 3508), limestone flakes, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Line drawing taken from Vandier d’Abbadie (1937), pl. 48, courtesy of the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Cairo) (a,b).

For comparison, consider an ostracon (now in Berlin) portraying a canine, perhaps a dog, wolf, or fox, drawn in black ink (Figure 12) (Davies and de Garis 1917, pp. 237–38, pl. 50). The animal, standing on its hind legs, is dressed in a lector’s shoulder sash and short skirt, but with the furry tail still very much in evidence. It has a growling or mournful demeanor and carries a branch of a thick plant in one paw, and probably a papyrus wreathed with bindweed or morning glory, like the details seen on the upper left corner of the fragment. As Nina and Norman de Garis Davies noted over a century ago, this ostracon scene bears a close resemblance to a ritual performed by a priest on a wall painting of the Tomb of Userhat, dating to the reign of the 19th Dynasty pharaoh Seti I (Figure 13). We may agree with the authors that the ostracon is a parody of the priestly funerary rite. More difficult to assess, however, is whether the humorous scene meant to satirize and thus criticize priests in general or caricaturize an individual priest or rite in particular.

Figure 12.

Canine (fox?) engaged in priestly activity (left, whereabouts unknown), ostracon, findspot unknown (said to be from Thebes), Ramesside period. A priest engaged in a similar ritual (right, TT 51), wall painting, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna (Theban necropolis), reign of Seti I (ca. 1290–1279) (Drawings taken from Davies and de Garis 1917, pl. 50) (a,b).

Figure 13.

Canines leading caprids (detail of BM reg. no. EA10016), illustrated papyrus, Deir el-Medina, Ramesside period (Image courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, London).

The aforementioned British Museum papyrus also includes a vignette of canines leading caprids (Figure 13).15 The identity of the animals is not entirely certain. Perhaps the canines are dogs, wolves, hyenas, or foxes; the caprids might be goats and/or gazelles. Behind an upright tabby cat driving geese and cradling a gosling exactly like the above ostracon (Figure 2), the first canine with a striped pelt—perhaps to be identified as a hyena—walks on hind legs leaning on a cane, while a pole slung over its shoulder carries a bag. Behind the herd of caprids with different coats and horns (to the viewer’s left) walks another canine—often identified as a fox—playing the common double flute, or pipes, while evidently also holding a short stick and carrying a basket on a pole across its shoulder (Manniche 1991, p. 23; Hambly 1954, pp. 267–68; Peck 1978, pp. 144–46; Malek 1993, p. 120; Brunner-Traut 1974, p. 124). As in the case of the cat herding geese, the comical effect revolves around the reversal of the natural order, in that predators here protect and care for their prey. As this vignette is part of a larger figured papyrus, it would seem safe to assume that the whole is intended to be read as a socio-political satire criticizing the breakdown of the natural, political, and perhaps even cosmic order.

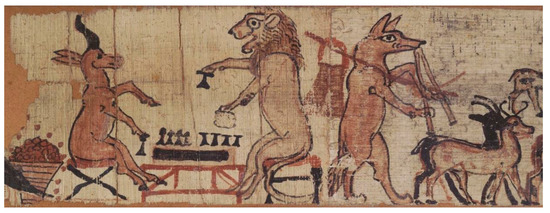

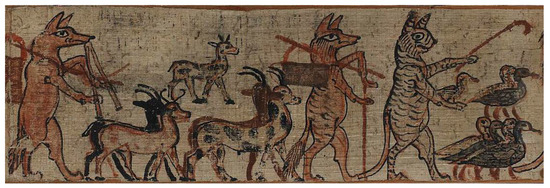

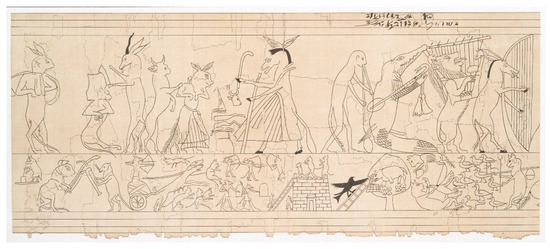

Donkeys. Called onomatopoeically aA (spelled variously  , or 𓃘 vel sim.), the donkey was used as a beast of burden, and was considered lustful—illustrated most famously in Roman times by Apuleius’ Metamorphosis, or the Golden Ass (ca. 150–170 ce).16 Consequently, it was not a symbol of high status and did not play an important role in ancient Egyptian art—appearing occasionally in agricultural scenes. A central vignette in the upper register of the Turin papyrus mentioned above shows an upright donkey dressed in the pleated linen costume of a dignitary (Figure 14 and Figure 15).17 The beast holds a staff and crook like a high and mighty judge passing verdict over other creatures. Immediately before him is a pile of offerings, including a bull’s head and various other animal parts. On the other side of the offering pile (to the viewer’s left) stand two animals on hind legs that—due to the fragmentary preservation of the papyrus—are difficult to identify. Perhaps a bovine is leading a canine to the donkey. Likely still part of the vignette is an upright caprid with a tall curving horn (farther to the left) that appears to execute a bound animal. The next scene (farther still to the left) may be understood as another horned caprid leading two more bound animals to the execution. If we read this motif correctly as the donkey passing his verdict and the goat executing it, would thus offer a parody of the noble judges. As such, the vignette would express a stinging commentary of the wanton corruption of the noble lords officiating as judges.

, or 𓃘 vel sim.), the donkey was used as a beast of burden, and was considered lustful—illustrated most famously in Roman times by Apuleius’ Metamorphosis, or the Golden Ass (ca. 150–170 ce).16 Consequently, it was not a symbol of high status and did not play an important role in ancient Egyptian art—appearing occasionally in agricultural scenes. A central vignette in the upper register of the Turin papyrus mentioned above shows an upright donkey dressed in the pleated linen costume of a dignitary (Figure 14 and Figure 15).17 The beast holds a staff and crook like a high and mighty judge passing verdict over other creatures. Immediately before him is a pile of offerings, including a bull’s head and various other animal parts. On the other side of the offering pile (to the viewer’s left) stand two animals on hind legs that—due to the fragmentary preservation of the papyrus—are difficult to identify. Perhaps a bovine is leading a canine to the donkey. Likely still part of the vignette is an upright caprid with a tall curving horn (farther to the left) that appears to execute a bound animal. The next scene (farther still to the left) may be understood as another horned caprid leading two more bound animals to the execution. If we read this motif correctly as the donkey passing his verdict and the goat executing it, would thus offer a parody of the noble judges. As such, the vignette would express a stinging commentary of the wanton corruption of the noble lords officiating as judges.

, or 𓃘 vel sim.), the donkey was used as a beast of burden, and was considered lustful—illustrated most famously in Roman times by Apuleius’ Metamorphosis, or the Golden Ass (ca. 150–170 ce).16 Consequently, it was not a symbol of high status and did not play an important role in ancient Egyptian art—appearing occasionally in agricultural scenes. A central vignette in the upper register of the Turin papyrus mentioned above shows an upright donkey dressed in the pleated linen costume of a dignitary (Figure 14 and Figure 15).17 The beast holds a staff and crook like a high and mighty judge passing verdict over other creatures. Immediately before him is a pile of offerings, including a bull’s head and various other animal parts. On the other side of the offering pile (to the viewer’s left) stand two animals on hind legs that—due to the fragmentary preservation of the papyrus—are difficult to identify. Perhaps a bovine is leading a canine to the donkey. Likely still part of the vignette is an upright caprid with a tall curving horn (farther to the left) that appears to execute a bound animal. The next scene (farther still to the left) may be understood as another horned caprid leading two more bound animals to the execution. If we read this motif correctly as the donkey passing his verdict and the goat executing it, would thus offer a parody of the noble judges. As such, the vignette would express a stinging commentary of the wanton corruption of the noble lords officiating as judges.

, or 𓃘 vel sim.), the donkey was used as a beast of burden, and was considered lustful—illustrated most famously in Roman times by Apuleius’ Metamorphosis, or the Golden Ass (ca. 150–170 ce).16 Consequently, it was not a symbol of high status and did not play an important role in ancient Egyptian art—appearing occasionally in agricultural scenes. A central vignette in the upper register of the Turin papyrus mentioned above shows an upright donkey dressed in the pleated linen costume of a dignitary (Figure 14 and Figure 15).17 The beast holds a staff and crook like a high and mighty judge passing verdict over other creatures. Immediately before him is a pile of offerings, including a bull’s head and various other animal parts. On the other side of the offering pile (to the viewer’s left) stand two animals on hind legs that—due to the fragmentary preservation of the papyrus—are difficult to identify. Perhaps a bovine is leading a canine to the donkey. Likely still part of the vignette is an upright caprid with a tall curving horn (farther to the left) that appears to execute a bound animal. The next scene (farther still to the left) may be understood as another horned caprid leading two more bound animals to the execution. If we read this motif correctly as the donkey passing his verdict and the goat executing it, would thus offer a parody of the noble judges. As such, the vignette would express a stinging commentary of the wanton corruption of the noble lords officiating as judges.

Figure 14.

Donkey standing before offerings (left) and a musical ensemble (detail of CME inv. no. c.2031, CGT no. 55001), papyrus, Deir el-Medina, 20th Dynasty (Image courtesy of the Egyptian Museum, Turin).

Figure 15.

Reconstruction of part of the animal section of the Turin Papyrus 55001 (CME inv. no. c.2031) (Taken from Émile Prisse d’Avennes, Histoire de l’art égyptien (Paris: Bertrand, 1878), pl. 78; image courtesy of the New York Public Library).

Of further interest is that another vignette (to the viewer’s right) portrays another donkey among a musical quartet (Figure 15, upper right) (Rogers 1948, pp. 154–60; Brunner-Traut 1974, pp. 125, 127; Habib 1980, pp. 1–2; Allam 1990, p. 75). While the donkey plays a large upright harp, a lion sings lead vocals and accompanies himself on a lyre, a crocodile plays a lute, and a blue monkey plays the double pipes. The motif is evidently a parody of the elegant female ensembles entertaining at luxurious feasts. Indeed, on the (viewer’s) farthest right—in a much-damaged detail—there appears to be a cat blending drinks with three syphoning tubes, possible for a now-lost banqueting scene. If considered as a whole, the animal section of the Turin papyrus—which further includes another scene of cat leading geese, a hippopotamus in a fruit tree, and the war of cats and mice, among other poorly legible motifs—it become evident that the animals not only parody human behavior. The vignettes voice criticism at certain aspects of human behavior, such as the wanton luxury of the nobility and royal house, the corruptibility of dignitaries and the capriciousness of lords and judges, and the failure of the ruling class to uphold the natural order. The topsy-turvy world of these anthropomorphized animal vignettes can therefore be understood as humorous satire with a bite and a sting.

5. Conclusions

The preceding paragraphs surveyed only a small sample of ancient Egyptian drawings of animals engaged in human behavior. Artistically, the ostracon sketches are of mediocre draftsmanship, whereas the few surviving papyri with similar motifs range from average to exceptional quality. From the rendering of details, it is evident that the artists observed animals firsthand, even if the individual species or, at times, the actual genera cannot be determined. Many of the themes of the ostraca recur on the larger papyri, but it remains impossible to discern whether the individual vignettes illustrate a larger narrative. If so, that narrative is either now lost or was never committed in writing (Babcock 2014, pp. 109–11).

Scholarly assessments of such scenes from ostraca and papyri—when provenanced, from Deir el-Medina and dating to the Ramesside period—have ranged widely: illustrations of myth or fables, comical inversions of the natural order, humorous parodies of human behavior, witty caricatures of the elite or biting satire of the ruling classes. We mentioned scenes from the Return of the Distant Goddess or the so-called War of Mice and Cats, of predators guarding or serving their prey, not to mention portrayals of greedy scribes recording inventories, wanton judges passing their verdict and hypocritical priests performing rites, musicians entertaining at feasts, and leisurely banquet and drinking revelries, as well as couples playing board games. It bears reiterating that in the absence of accompanying texts it remains difficult to determine the intention of these anthropomorphized animal motifs.

Evidently the artists of these scenes were familiar with royal and noble funerary iconography. Indeed, it must have been the same artists who were employed in the decoration of the Ramesside tomb and temple walls in the Theban region who drew the figured ostraca and papyri portraying animals in similar human activities. With Jennifer Babcock we may observe that these artisans were part of the educated, literary, cultured elite (Babcock (2013, 2014)). Indeed, the other side of the satirical animal section of the Turin papyrus (CGT no. 55001) portrays outright pornographic scenes of commoners, peasants or workers, performing various acrobatic sexual positions with elegant noblewomen. The artist thus derided the lustful lower class for their erotic fantasies, and with that disdain placed himself higher in class.

Nonetheless, wishing to participate in elite culture and expressing a disdain towards the lower class did not place the artisans in the highest echelons of society. They were literally and figuratively caught in the middle between the lower and the ruling classes. They may not have been seen as commoners by their superiors, but they still needed to work to make a living. Even if they could afford the relatively expensive papyri to draw the images in question, we cannot know how or why they acquired the material. Moreover, although they may have been educated, literate, and cultured, they had no power even over their own lives, and certainly did not have the leisure to engage in the luxurious lifestyle of the ruling classes—the very lifestyle some of the imagery ridicules.

Satire is said to be the weapon of the weak—a means to communicate resentment towards one’s superiors through veiled humor. Although generally, ancient Egyptians may have viewed their superiors with respect, that does not negate that some people also saw the mortal weaknesses of the elite. The animal scenes in comical situations parodying monumental funerary and religious art reveal a level of freedom of thought and artistic expression unrestrained by decorum, convention, or tradition. In the preceding, I argued that at least some of the drawings that parodied scenes from human life by means of anthropomorphized animals may well have voiced social and/or political critique. It cannot be discerned whether some of the imagery intentionally caricaturized individual lords, priests, or kings. Against the historical background of the decline of the New Kingdom during the 20th Dynasty, satirical criticism may well be understandable. Some of the scenes at least do appear to express resentment towards the corruptibility of the nobility, the hypocrisy of the priesthood, and the failure of the royal house to maintain order—to uphold the social and political, natural, and cosmic order of justice and truth (ma῾at).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexandre, Arsene. 1892. L’Art du Rire et de la Caricature. Paris: Ancienne Maison Quantin Librairies-Imprimeries Reunies. [Google Scholar]

- Allam, Schafik. 1990. Some Pages from Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt. Giza: Foreign Cultural Information Department. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Robert. 1976. Catalogue of Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum III, Musical Instruments. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- André, Jean-Marie, ed. 1991. Jouer dans l’Antiquité. Marseille: Musées de Marseille. [Google Scholar]

- Atiya, Farid. 2005. Ancient Egypt. Giza: Farid Atiya Press. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, Jennifer. 2013. Understanding the Images of Anthropomorphized Animals in New Kingdom Ostraca and Papyri. Bulletin of the American Research Center in Egypt 203: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, Jennifer. 2014. Anthropomorphized Animal Imagery on New Kingdom Ostraca and Papyri: Their Artistic and Social Significance. Ph.D. thesis, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard, Ollivier. 1894. La Caricature Egyptienne: Historique, Politique, et Morale. Paris: Thorin. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, Raymond. 2015. Animals and Pharaohs, The Animal Kingdom in Ancient Egypt. Ancient Egypt Magazine 88: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1963. Altägyptische Märchen. Düsseldorf and Köln: Eugen Diederichs Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1968. Altägyptische Tiergeschichte und Fabel: Gestalt und Strahlkraft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1974. Die Alten Ägypter Verborgenes Leben unter Pharaonen. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1979. Egyptian Artists’ Sketches: Figured Ostraka from the Gayer-Anderson Collection in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Leiden: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1984. Satire. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Edited by Wolfgang Helck and Eberhard Otto. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, vol. 5, p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, Peter. 1994. Chronicle of the Pharaohs, The Reign-By Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina, and Normand de Garis. 1917. Egyptian Drawings on Limestone Flakes. JEA 4: 234–40. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina, and Normand de Garis. 1922. The Tomb of Puyemre at Thebes. The Hall of Memories. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shahawy, Abeer. 2005. The Funerary Art of Ancient Egypt: A Bridge to the Realm of the Hereafter. Cairo: Farid Atiya Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erman, Adolf. 1971. Life in Ancient Egypt. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2000. Animals in the Domestic Environment. In Egyptian Art: Principles and Themes in wall Scenes. Series 6; Edited by Leonie Donovan and Kim McCorquodale. Giza: Foreign Cultural Information Department. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre, Christopher. 2011. Children and Literature in Pharaonic Egypt. In Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen. Edited by Mark Collier and Steven Snape. Bolton: Rutherford Press, pp. 177–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Henry G. 1978. Notes on Sticks and Staves in Ancient Egypt. Metropolitan Museum Journal 13: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Diane. 2004. The Topsy-Turvy World. In Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World: Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Antoine Hirsch. Leiden: Brill, pp. 233–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Alan H., and Arthur E. Weigall. 1913. A Topographical Catalogue of the Private Tombs of Thebes. London: Bernard Quaritch. [Google Scholar]

- Germond, Philippe, and Jacque Livet. 2001. An Egyptian Bestiary: Animals in Life and Religion in the Land of the Pharaohs. New Yok: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, Raouf (Raʿūf Ḥabīb). 1980. Ancient Egypt Caricatures until Islamic Era. Cairo: Mahabba. [Google Scholar]

- Hambly, Wilfrid D. 1954. A Walt Disney in Ancient Egypt. The Scientific Monthly 79: 267–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda K. 2013. The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69): The Art, Culture and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodel-Hoenes, Sigrid-Eike. 2000. Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes. Translated by David Warburton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, Patrick F. 1996. The Animal World of the Pharaohs. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, Patrick F. 2001. Wit and Humor in Ancient Egypt. London: Rubicon. [Google Scholar]

- James, Thomas G. 1985. Egyptian Painting and Drawing in the British Museum. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, Rosalind, and Jac J. Janssen. 1996. Getting Old in Ancient Egypt. London: Rubicon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loth, Marc. 2006. Sehr, sehr schön ist diese Statue: Zur Schönheit in der altägyptischen Kunst und Architektur. Kemet 15/1: 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, Georg. 2000. Ancient Pathways and Hidden Pursuits: Religion, Morals, and Magic in the Ancient World. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lythgoe, Albert M. 1923. The Tomb of Puyemrê at Thebes. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 18: 186–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, Jaromir. 1993. The Cat in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manniche, Lise. 1991. Music and Musicians in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Angela. 2009. The curiosity of the cat in hieroglyphs, In Sitting beside Lepsius: Studies in Honour of Jaromir Malek at the Griffith Institute. Series: Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 185; Edited by Diana Magee, Janine Bourriau and Stephen Quirke. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 361–80. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, David. 2011. Satire or Parody? The Interaction of the Pictorial and the Literary in Turin Papyrus 55001. In Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen. Edited by Mark Collier and Steven Snape. Bolton: Rutherford Press, pp. 361–80. [Google Scholar]

- Omlin, Joseph A. 1973. Der Papyrus 55001 und Seine Satirisch-Erotischen Zeichnungen und Inschriften. Turin: Pozzo. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, William H. 1978. Drawings from Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen, and Jeffrey Spencer. 1992. The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, Maarten J. 2000. Prisse d’Avennes, Atlas of Egyptian Art. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redford, Donald B. 2001. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, Nicholas, and Richard H. Wilkinson. 1996. The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt’s Greatest Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Elizabeth A. 1948. An Egyptian Wine Bowl of the XIX Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art 6: 154–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Margaret A. 1993. Parody: Ancient, Modern, and Post-Modern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Nora E. 1962. A Stela and an Ostracon: Two Acquisitions from Deir el Medīneh. Metropolitan Museum of Art 21: 149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaw, Ian, and Paul Nicholson. 1997. British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- A. E. Stallings, trans. 2019, The Battle between the Frogs and the Mice: A Tiny Homeric Epic. Philadelphia: Paul Dry Books.

- Taylor, John H. 2010. Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey through the Afterlife. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- te Velde, Herman. 1980. A Few Remarks upon the Religious Significance of Animals in Ancient Egypt. Numen 27: 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tilg, Stefan. 2014. Apuleius’ Metamorphoses: A Study in Roman Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vandier d’Abbadie, Jacques. 1937. Catalogue des Ostraca Figurés de Deir el Médineh. N° 2256–2722 (DFIFAO 2.2). Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Vycichl, Werner. 1983. Histoires de Chats et de Souris, Un Problème de la Littérature Egyptienne. BSEG de Geneve 8: 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Toby. 2005. Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Hilary. 1997. People of the Pharaohs from Peasant to Courtier. London: Brockhampton. [Google Scholar]

- Yurco, Frank J. 1999. Deir el Medina. In Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Kathryn A. Bard. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 247–50. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Ostracon (plural: ostraca) is the Classical Greek term for “potsherd”; the term is used in Egyptological studies both for sherds of pottery and flat limestone flakes. In ancient Egyptian, the word used is nDr, nD (“splinter, break, sherd”); the literal meaning is thus “fragment,” but ostraca are whole works of art (Davies and de Garis 1917, p. 234; Brunner-Traut 1979, p. 1). |

| 2 | Scholars such as Nina and Norman de Garis Davies, Patrick Houlihan, Emma Brunner-Traut, and William Peck state that the figured ostraca are examples of popular art or “non-elite” art. |

| 3 | Situated in the desert on the West Bank of the Nile at Thebes, in a bay in the cliffs north of the Valley of the Queens; for which, see (Yurco 1999, p. 247; Janssen and Janssen 1996, p. 9; Malek 1993, p. 112). |

| 4 | For definitions of these terms, see CED sub voc. (available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org) and MWD sub voc. (available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com) [both accessed on 4 December 2020]. |

| 5 | See also Brunner-Traut (1963, p. 44). |

| 6 | For TT 39, see (Lythgoe 1923, pp. 186–88; Gardiner and Weigall 1913, p. 18); for the pastoral scene, see (Davies and de Garis 1922, pl. 12; Fischer 1978, p. 8, fig. 7). |

| 7 | For interpretations of this banquet parody, see Alexandre (1892, p. 6); Vandier d’Abbadie (1937, pp. 69–70); Peck (1978, p. 147); Wilson (1997, p. 64); Babcock (2014, pp. 21–22). |

| 8 | For interpretations of the details of this banquet scene, see Beauregard (1894, p. 222); Peck (1978, p. 147); Malek (1993, pp. 113–14). |

| 9 | I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for this observation. |

| 10 | For Cairo papyrus no. JE 31199, see James (1985, p. 60); Houlihan (2001, p. 67); Babcock (2014, pl. 5). |

| 11 | For the Batrachomyomachia, now see Stallings (2019). |

| 12 | For the animal section of Turin Papyrus no. 55001 (CME inv. no. C.2031), see Omlin (1973, pls. 13, 18); Malek (1993, p. 113); Babcock (2014, pls. 4, 10). |

| 13 | For interpretations of the details of this combat scene, see Beauregard (1894, pp. 169–75); Erman (1971, p. 520); Brunner-Traut (1974, pp. 125, 127); Habib (1980, pp. 2–3); Vycichl (1983, pp. 105, 107); Malek (1993, pp. 114, 118–19); Houlihan (1996, p. 216); Clayton (1994, p. 150); Houlihan (2001, pp. 62–63); Loth (2006, p. 49); O’Connor (2011) and Babcock (2014, pp. 26–28). |

| 14 | For Papyrus BM EA10061, see Alexandre (1892, p. 6); Beauregard (1894, p. 204); Peck (1978, pp. 144–46); Allam (1990, p. 83); André (1991, cat. no. 253, pp. 153, 199, fig. 138); Quirke and Spencer (1992, pp. 130–31); Shaw and Nicholson (1997, p. 107); Houlihan (2001, p. 65) and Taylor (2010, no. 73). |

| 15 | For Papyrus BM EA10061, supra n. 14; Anderson (1976, p. 5) and Babcock (2014, p. 73). |

| 16 | For the Golden Ass, see Tilg (2014). |

| 17 | For Turin Papyrus no. 55001, supra n. 12; for the interpretation of the donkey vignette, see (Beauregard 1894, p. 151; Houlihan 2001, p. 71; Babcock 2014, p. 78). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).