Abstract

Urban design professionals are key actors in early design phases and have the possibility to influence urban development and direct it in a more sustainable direction. Therefore, gender differences in environmental perspectives among urban design professionals may have a marked effect on urban development and the environment. This study identified gender differences in environment-related attitudes among urban design professionals involved in the international architectural competition ‘A New City Centre for Kiruna’ in northern Sweden. Participants’ self-rated possibility to influence environmental aspects was higher for males than for females. Conversely, the importance placed on environmental aspects had higher ratings among females, although the differences regarding the rating of personal responsibility were small. The gap between the participants’ self-rated belief in their ability to influence and rated importance of environmental aspects was larger among female participants. Females placed great importance on environmental aspects even though they felt that their possibility to influence these was rather low. Conversely, male participants felt that they had the greatest possibility to influence, although some males rated the importance of environmental aspects thelowest. The gender differences identified are important from an equality and environmental perspective as they may influence pro-environmental behavior among urban design professionals and ultimately influence the environmental performance of the built environment.

1. Introduction

Buildings and infrastructure are responsible for a substantial proportion of the global use of natural resources, energy use and emissions to air, water and land [1]. Therefore, creating more sustainable designs for buildings and neighborhoods would be beneficial for human health and the environment [2] and could improve building quality without increasing costs [3]. The main barrier to more environmental and sustainable buildings and neighborhoods is neither technological nor economic issues, but rather social and psychological factors [4]. In particular, the attitudes towards environmental aspects among decision-makers in the planning and building sector, such as architects, landscape architects, urban planners and urban designers (here referred to as ‘urban design professionals’), or other actors involved in the building and property sector, such as property owners, developers and contractors, may play an important role in realizing the technological potential of a more sustainable built environment. Urban design professionals are often presented as key actors in the complex planning and design process [5,6]. In relation to other groups, they have a marked possibility to influence how the built environment is planned, designed and constructed and, consequently, they influence the environmental impact of the built environment. Thus, it is important to study their views regarding environmental aspects.

There are well-documented gender differences regarding environmental issues, opinions and preferences [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. However, the perspective and effect of gender have rarely been sufficiently addressed in research dealing with energy issues [20] or urban planning. Due to the great potential of sustainable design, there are few other contexts where these gender differences can leave such a marked effect on the environment as among urban design professionals. For example, females attribute more importance to environmental issues than males do [12]. Such values, which can be conceptualized as people’s desirable, transitional goals, serve as guiding principles in people’s lives and are a point of reference in decision-making [21]. These transitional goals are an example of an internal psychosocial determinant of pro-environmental behavior [22]. Thus, they may underpin the way that urban design professionals consider environmental issues in their professional decisions. Environment-related attitudes, behaviors and personal habits are typically studied in the context of leisure time, including environmental decisions and behavior regarding personal habits during unpaid working hours, such as the use of electric cars, transportation behavior, energy savings in households and waste management and recycling [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Significantly less is known about aspects that can affect pro-environmental behavior in the context of professional work, such as environment-related attitudes and values among urban design professionals. In this paper, pro-environmental behavior among urban design professionals is defined as pursuing environmental planning and design, which involves consciously designing buildings and neighborhoods in order to minimize their negative environmental impact.

The study of gender differences amongst architects and urban designers is further motivated by the substantial male dominance in the current building and construction sector. Despite females being the original builders in many early civilizations [32], there is a male dominance today, especially among construction workers. For example, females comprise only 1% of the construction union members in Sweden [33]. The male dominance in the urban and building design domain is less pronounced and decreasing as the number of female urban design professionals, who graduate from university, increases. Overall, the proportion of female architects is 39% among a total of 565,000 architects in Europe [34]. However, the proportion varies between countries, ranging from 15% (Estonia) to 58% (Greece and Latvia). In the 21st century, there has been opposing trends with a decline in the number of females in the profession in the UK [35]. Sweden is among the countries with the highest percentage of female architects. For example, females constitute 53% of the members of the Swedish Association of Architects (n = 12376), which encompasses architects (48% females of 8733 in total), landscape architects (73% females of 1853 in total) and urban planners (64% females of 807 in total) [36].

The aim of the present study was to measure environment-related attitudes among urban design professionals and to identify potential gender differences with regard to these attitudes. In order to achieve this, the architectural competition ‘A New City Centre for Kiruna’ [37] was used as a case study. This architectural competition concerned the relocation of the city center of Kiruna, a city with 18,000 inhabitants, which is situated in the arctic region of Sweden [38]. The relocation is due to the expansion of iron mining operations, which will undermine the city. The first part of the competition comprised an open international prequalification process where 54 teams applied. This prequalification process did not have any stated focus on gender equality aspects regarding the competitors. The competition program presented the present situation in Kiruna, which has a male dominated mining industry, Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara aktiebolag (LKAB), and a female domination in public care. Environmental concerns and energy aspects were also presented and the goal of a ‘sustainable model city’ was pushed forward. After this, the Kiruna municipality chose 10 teams of highly renowned architectural firms to compete (Supplemental data Appendix A) out of the 54 teams that had applied. They were given the same prerequisites for designing a competition entry: a competition program [37], maps and information, financial compensation and a four-month time limit. This architectural competition was suitable as a case study as it comprised a sample of many respondents working with the same design task, project, design phase and time period.

A previous study based on other questions in the survey administered to the urban design professionals reported on the use of environmental assessment tools and management systems in the competition [39]. In the present study, the analysis was extended to gender differences in urban design professionals’ self-rated views of attributed importance, feelings of responsibility and feelings of their possibility to influence (locus of control) a range of environmental aspects in their profession.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Setting

The study was conducted as an observational cross-sectional survey with a questionnaire administered to urban design professionals participating in the international architectural competition ‘A New City Centre for Kiruna’. This provided a diverse sample where all the design professionals were working with the same project. Having numerous design professionals working with the same project is exceptional. In typical building and/or urban planning projects, it is often one company and fewer persons involved in the early design phase. Therefore, it was possible to develop the questions to specifically relate to the Kiruna project. This possibility served to minimize heterogeneity related to variations in influence, responsibility and importance of environmental aspects in different architectural projects. Furthermore, the participants had a substantial opportunity to influence environmental issues, since the project specifically dealt with a relatively large urban development of approximately 40 hectares (400,000 m2) compared to other urban-development projects in Europe [40], including buildings and infrastructure, and one of the goals stated in the competition program was ‘a sustainable model city’ [37].

2.2. Statistics

Descriptive data were presented as frequencies, percentages, means and standard error of the means, while a 95% confidence interval was used. The Student t-test was used for comparisons of continuous variables. The magnitude of group differences (independent variable) for the dependent variables was calculated using a multivariate analysis of variance. Group differences were further determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. For statistical analyses, we used Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

2.3. Materials

A total of 58 of the 134 competitors in the 10 invited teams in the competition responded completely to the questionnaire (response rate of 43%). The final sample consisted of 39 males and 19 females. The mean age of the males was 39 years (± 8.76), and 39 years for the females (± 8.78) (t(56) = 0.08, p = 0.936). The majority of the participants were from Sweden and other northern European countries (Table 1) and the most common profession was architect (53%).

Table 1.

Individual and external characteristics of respondents (n = 58).

2.4. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire (Supplemental data Appendix B) was constructed and validated in three pilot tests where 6–8 professionals were used as test subjects each time. English was used in the e-mail survey and for the cover letter, which provided information on the aim of the study, data confidentiality, contact details to the researchers and an assurance that participation was voluntary.

The questions analyzed in this paper mainly concerned issues that could have connections to pro-environmental behavior, such as: the possibility to influence as well as the responsibility and importance of 18 environmental aspects. These environmental aspects were grouped into seven environmental categories: Energy, Transport, Material, Waste, Water, Local environment and Land Use & Ecology. The environmental aspects were chosen based on the content of the environmental assessment tools LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) for neighborhood development [41], BREEAM (BRE Environmental Assessment Method) Community [42] and CASBEE (Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency) for Urban Development [43]. In addition, the ecosystem services and toxic materials were included as they are important environmental aspects [44]. Questions regarding the knowledge and use of neighborhood and building environmental tools and environmental management systems and ecological world views were also included. The survey tool ‘SurveyMonkey’ [45] was used and the web questionnaire was e-mailed (including three reminders and phone contact) to all participants between June and October 2013.

3. Results

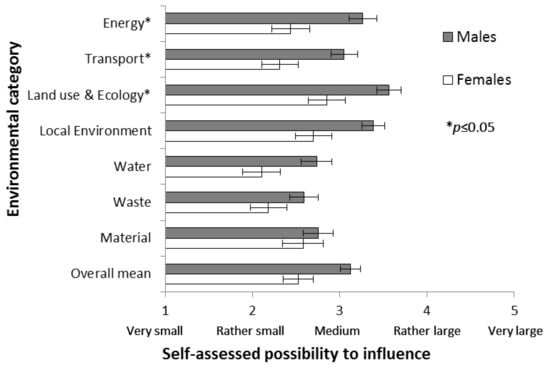

The self-rated possibility to influence environmental aspects was systematically higher for males than for females (Figure 1). This finding was supported by multivariate analysis of variance with the seven possibility-to-influence estimates (i.e., the seven environmental categories) as the dependent variables and participant gender as the independent variable (Wilks’s λ = 0.69, F(7, 49) = 3.10, p = 0.009). Item-specific analyses revealed gender differences in participants’ self-rated estimates of the possibility to influence transport (t(55) = 2.70, p = 0.009), energy (t(55) = 3.15, p = 0.003), land use and ecology (t(55) = 2.90, p = 0.005), the local environment (t(55) = 2.89, p = 0.005) and water issues (t(55) = 2.17, p = 0.035), although there were no gender differences in waste (t(55) = 1.51, p = 0.138) and material issues (t(55) = 0.60, p = 0.553).

Figure 1.

Mean values for self-assessed possibility to influence a range of environmental categories. Error bars represent the standard error of means.

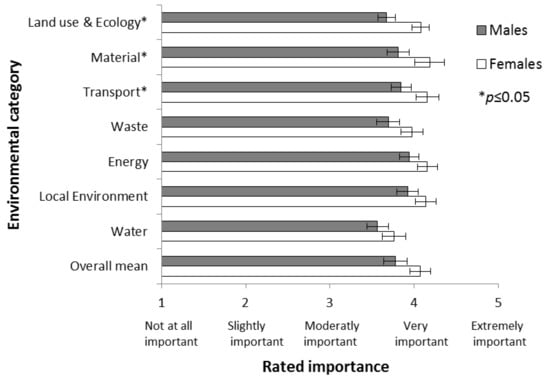

Conversely, the importance assigned to all these environmental categories received higher ratings among females than males (Figure 2), although this gender difference did not reach significance in the context of a multivariate analysis with all seven importance estimates being assigned as the dependent variables (Wilks’s λ = 0.91, F(7, 49) = 0.74, p = 0.636). More importantly, the gap between participants’ self-rated importance of these issues and their belief in their possibility to influence these issues was larger among female participants than among male participants. This was demonstrated in a 2(Gender: Females vs. Males) × 2(Judgmental dimension: Importance vs. Possibility to influence) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the overall means for the two judgmental dimensions used as the dependent variables separately. That analysis revealed a significant effect of judgmental dimension (F(1, 55) = 104.86, MSE = 0.29, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.66) and a significant interaction between gender and judgmental dimension (F(1, 55) = 17.12, MSE = 0.29, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.24). There was no main effect of gender on the overall means (F(1, 55) = 0.97, MSE = 0.59, p = 0.330, ηp2 = 0.02).

Figure 2.

Mean values for estimated importance across a range of environmental categories. Error bars represent the standard error of means.

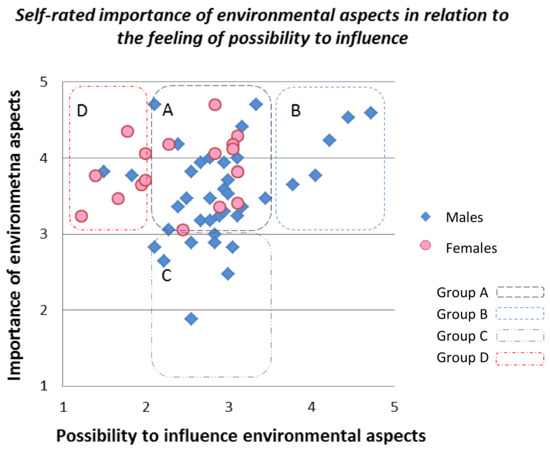

To further explore the data, the responses were plotted across the two variables of key interest: the professionals’ view of the importance of environmental aspects and their possibility to influence (Figure 3). Four different participant groups were distinguished on the basis of the proximity of the data points. The largest group (Group A) contained both males and females, who rated environmental impacts as important (>3) but rated their possibility to influence these issues as rather low (2.0–3.5). Group B contained only males, who self-rated both the importance of environmental impact and their possibility to influence as high (>3 and >3.5 respectively). In contrast, the members of Group D, which mainly comprised females, rated environmental impacts as important, but rated their possibility to influence as very low (≤2). Group C was another all-male group, which considered the environmental impacts to be least important compared to all the other participant ratings (≤3) and reported that they had rather low possibility to influence. In general, the females’ answers were not as widely distributed as those of the males.

Figure 3.

Self-rated mean values of the importance of environmental aspects in the Kiruna project and self-rated possibility to influence the competition proposals.

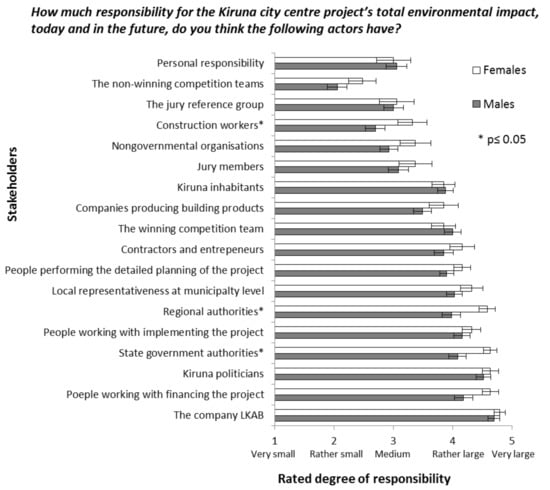

Males and females had similar mean ratings of 3.35 (±0.73) and 3.17 (±0.64), respectively, when rating their personal responsibility regarding the potential negative environmental impacts of the Kiruna project. Furthermore, there were no significant differences for any of the environmental categories with regard to personal responsibility. However, there were some systematic differences in male and female participants’ attribution of responsibility for the total environmental impact of the Kiruna city center project to different stakeholders in that project (Figure 4). There was no statistically significant gender difference in the context of a multivariate analysis with all stakeholder items included as dependent variables (Wilks’s λ = 0.65, F(18, 39) = 1.167, p = 0.333), but item-specific analysis revealed that females attributed significantly higher responsibility to “Regional authorities” (t(56) = 2.45, p = 0.017), “State government authorities” (t(56) = 2.43, p = 0.018) and “Construction workers” (t(56) = 2.15, p = 0.036). The only stakeholders that males ranked higher than females were “The winning competition team”, “Kiruna Inhabitants” and “Personal responsibility”. Both males and females ranked the mining company LKAB as the one stakeholder with the highest responsibility for environmental aspects in the Kiruna city center project.

Figure 4.

Mean values for the degree of responsibility for environmental impacts in the Kiruna project attributed by male and female participants to a range of different stakeholders. Error bars represent the standard error of means.

4. Discussion

There were several systematic gender differences among the urban design professionals surveyed in this study and these, individually or in combination, can influence pro-environmental behavior [22]. Specifically, males and females differed with regard to their self-rated view of (1) the possibility to influence environmental aspects, (2) the importance of environmental aspects and (3) their own and others’ responsibilities regarding environmental aspects.

4.1. Lower Possibility to Influence among Females

The largest gender difference was found regarding their perceived possibility to influence different environmental aspects in the Kiruna project. There are a number of possible explanations for this gender difference. One may be that females actually have less influence in the design process due to their age, role in the competing group, education, profession or a combination of these. However, the gender difference could scarcely be explained by age, since the two gender groups were highly similar in age. Moreover, a majority of the male and the female participants were architects. In turn, there was a relatively large difference between males and females (30% vs. 11%) with regard to whether they defined themselves as the “leader of the group”. This reflects the existing situation in the profession. Leading positions are less frequently occupied by females [46]. There is a male dominance among older architects [34], which may be connected to the male dominance in leading positions. A possible reason for the male dominance in leading positions could be that females take a larger responsibility for family life [46] and females tend to leave the architecture profession to a higher extent than males [47,48,49].

A more psychological explanation for the gender difference in perceived possibility to influence could be that females have as much possibility to influence as males, but perceive these possibilities as being lower. This possibility is consistent with instances of gender differences reported previously. For example, females are typically less confident in their abilities [50] and underestimate their knowledge [51] more than males. A study on gender aspects in Scandinavian climate policy-making showed that even though women were represented in equal numbers as men, this did not automatically result in women influencing the climate policy-making [52]. These authors emphasize that masculine norms can be deeply institutionalized [52] and equal representation in planning and decision-making processes is not a guarantee for achieving gender awareness [53].

It is possible that the feeling of low possibility to influence depends on a feeling of incompetence with regard to how to handle and design urban environments to minimize environmental impact. This is consistent with findings in our parallel study based on the same survey as the present study [39], which concluded that professionals’ knowledge regarding how to handle environmental impacts could be improved. The largest differences between males and females were found regarding the environmental aspects of Energy, Transport and Land use & Ecology. Dymén et al. [53] proposed the possibility for the differences in attitudes and behavior in relation to environmental aspects, such as climate change, to be gendered. Before suggesting that the differences found in this study can be caused by gender-dependent differences, further investigation and research is needed.

Another explanation of the gender difference in perceived possibility to influence could be that females would like to influence environmental aspects more than they can. Essentially, females have higher expectations of a sustainable environment than males and therefore feel that they do not have the possibility to influence to the extent that they would like.

4.2. High-Rated Importance of Environmental Aspects

The participants’ ranking of the importance of environmental aspects provides insights into their views on and attitudes toward environmental aspects. The results agree with other research findings that males care less for environmental issues than females do [12,51]. In the present study, female urban design professionals attributed more importance to environmental issues than male professionals did.

A possible explanation for the gender difference, with regard to how important they rate environmental issues, could be that if males believe that they can influence environmental aspects to a higher degree than females do, they are less concerned about the seriousness of environmental aspects and underrate the importance of these environmental challenges. In general, men tend to believe in technological solutions more often [54]. They may believe that they have the possibility and power to decrease environmental impacts and therefore, have a more positive view on how to manage environmental concerns.

Even if females generally view environmental issues as more important than males do, it may be interesting to consider the fact that some of the males who reported the highest rating of possibility to influence also reported high ratings for the importance of environmental aspects (Figure 3). One possible interpretation of this finding, which is connected to the role in the team, is that preferences, attitudes and valuation of different aspects may change for individuals in a leading position. For example, in an architectural project, individuals having a leading position may give other issues, such as economic aspects, higher value than environmental aspects and thus, lowering the relative importance of environmental aspects. However, the results did not support this theory, as the participants that gave a high ranking to possibility to influence also ranked the importance of environmental aspects rather high, while the males who rated the importance of environmental aspects lowest did not report a high possibility to influence.

4.3. Possibility to Influence in Relation to Perceived Importance

The combination of feeling unable to influence environmental issues and feeling that environmental issues are important is particularly interesting from a psychological viewpoint. Feelings of being unable to reach a desirable outcome, such as the desire to reduce the environmental impact of the built environment, can be a major source of stress [55]. The importance of this issue is further reinforced by the fact that males also reported slightly higher personal responsibility for environmental issues than females. Female urban design professionals seem to regard environmental impacts of the built environment as highly important to handle, but at the same time, they do not feel that they can influence them, which could make them feel that these environmental aspects are not within their professional responsibilities. This could add to a build-up of stress associated with being unable to control desirable outcomes. However, this possible connection between responsibility and possibility to influence was not found when analyzing the data. Instead, there was an association between a high perceived importance of environmental aspects and feeling a high degree of responsibility for the same environmental aspects. A target for future studies is to explore the potential role for this discrepancy in female urban design professionals’ work-related satisfaction and stress experiences.

The relationship between possibility to influence and feeling of importance among the individual respondents identified four different groups of respondents (A–D). The majority of the respondents (57%) were in group A and had a fairly high rating of importance and a medium rating of influence. Members of this group were concerned about environmental impacts, although they rated their possibility to influence as medium and they subsequently might rely on others to take the lead in dealing with environmental aspects. If the individuals in this group perceived a larger possibility to influence, it might increase their pro-environmental behavior, as they already rate the importance of environmental aspects as being high. On the other hand, giving them a larger possibility to influence by becoming a leader could change their view on the importance of environmental aspects in relation to other aspects. They might then drop to group C instead, with a possible negative influence on pro-environmental behavior.

The members of group D were mainly females, who rated the importance of environmental aspects high, but their possibility to influence low. A high feeling of importance and low possibility to influence (low locus of control) can result in people giving up on doing something about environmental problems. This situation could arguably lead to a greater prevalence of frustration among female urban design professionals, arising from the inconsistency between the importance of an environmental aspect and their inability to do something about it. This is further reinforced by the finding that females felt almost as much personal responsibility for environmental aspects as male participants did. The rating of their possibility to influence could be expected to have an association with the feeling of responsibility. Essentially, if the individual perceives that they have no possibility to influence, their responsibility could be influenced, but the results did not show any clear connection between the possibility to influence and individual responsibility.

The two groups consisted solely of males (group B and C). Group B was comprised of males, who expressed a high possibility to influence and placed high importance on environmental aspects. According to theories on pro-environmental behavior [22], these individuals are those who will probably work the most with pro-environmental actions when designing urban environments. They feel that the subject is important and they believe that they have the possibility to do something about it.

It was only males who rated low importance and low possibility to influence (group C). The members of this group are those least likely to work with environmental aspects and with pro-environmental behavior, as they do not feel that they have the possibility to influence or believe that environmental issues are important. These males must have rated several environmental aspects as “slightly important”, which is a rather low rating compared to the majority of respondents’ ratings and shows a low interest in environmental issues. This group of males probably lowered the total mean score for males regarding the perceived importance of environmental impacts. Thus, the males had a wider distribution of rated importance of environmental aspects than females.

It was also noted that the males diverged more in their views, while female participants’ views were more clustered together. The large variation among respondents also indicated that perceived high importance is not automatically connected to a high feeling of possibility to influence.

4.4. Participants and Other Stakeholders’ Responsibility

Interestingly, the overall rating of responsibility was rather high and there were no significant gender differences regarding the reported responsibility for different environmental aspects. Despite the challenge in planning, design, construction and management of urban environments with many different actors, stakeholders and interests involved, the urban design professionals considered themselves as having a rather large responsibility. There were some gender differences with regard to the allocation of responsibility to different stakeholders. Females attributed a higher degree of environmental responsibility to regional and state government authorities, construction workers, non-governmental organizations and people involved in financing the project. This may reflect the fact that the female urban design professionals felt less personally responsible for these same issues and felt that they had a lower possibility to influence.

4.5. Impact on Pro-Environmental Behavior, Urban Planning and the Environment

Possibility to influence, feeling of importance and responsibility are internal factors that are linked to pro-environmental behavior [56,57]. Therefore, gender differences found among these internal factors may lead to gender differences in pro-environmental behavior when designing urban environments that ultimately affect the built environment and its environmental impact. When these differences in internal factors vary depending on the environmental category, they may cause females and males to act differently when considering different environmental aspects in the planning and design processes. As a consequence, the outcome of the planning and design process, which is the planned urban environment, could be influenced and directed in different directions depending on the gender of the urban design professionals involved in the process. Thus, equality and equity in professional situations is an important aspect to consider in environmental, decision and gender studies. Dymén et al. discussed about gender-dependent differences in citizens’ attitudes and behavior in relation to environment [53]. Therefore, involving both men and women in urban design processes is of importance. According to Manusdottir and Kronsell [52], an equal distribution of representations can still result in changes to masculine norms, which can be institutionalized when it comes to climate policy. It could also possibly be relevant for urban planning decision-making. Other studies have identified equality and equity issues among urban design professionals in general and architects in particular [58,59] or have focused on the gender issues in urban planning from other perspectives, such as how the urban environment is planned and designed and to whom the physical environment is adapted [60] or the way female architects are portrayed [61]. The present study highlights gender differences for internal factors, which may influence the process and pro-environmental behavior.

4.6. Perspectives of the Study

Important gender differences were found and the possible reasons behind the differences were discussed. Larger surveys are welcomed in order to study pro-environmental aspects in detail and to confirm the findings to address external validity. However, finding a larger number of participants working at the same time with the same architectural project with a similarly large environmental impact as the Kiruna project is difficult as this was an extremely large project as it involved moving a whole city center. There is also a need to evaluate whether these viewpoints are desirable or should be altered. If gender differences can have negative and/or positive consequences on the environment, they should be considered. According to pro-environmental behavior theories, high rated locus of control, perceived importance and responsibility are vital to increase the predisposition to pro-environmental behavior. A future consideration when working with building and urban design should be to ensure that the distribution of males and females in design processes is more equal. The issues of equality among males and females in professional life [62], gender-focused and gender-aware planning and design [63,64] and the gender perspective on processes and products of built environment [65,66] have been raised by others from a gender perspective, but not from an environmental perspective as in this study. This study demonstrated gender differences among urban design professionals that might influence pro-environmental behavior and thus, environmental design. Further studies are needed to determine whether the differences in individual factors regarding their possibility to influence, importance and responsibility can influence pro-environmental behavior as a cause–effect relationship. As both importance and responsibility in general were rated to be rather high among the urban design professionals surveyed in the present study, these two internal indicators cannot be increased much more and thus, cannot affect architects’ environmental design much more. Instead, the feeling of their possibility to influence can be of higher importance. The reasons behind the gender differences for different environmental aspects also need to be further investigated. Male and female opinions, values or knowledge regarding different environmental aspects may vary and the reasons behind these differences need to be investigated. The results presented in this study call for increased gender awareness in the planning, design and building processes, in education and regulation and in environmental studies. Altering the situation by having workplace reforms in architectural firms to bring about full gender equality may be overly hopeful [59], although it may be easier in the urban planning situation, but other future methods probably need to be investigated. Furthermore, this study highlighted the importance of having female participants in research studies to increase generalizability and avoid gender bias.

It is claimed that the architectural profession is under-theorized from a gender perspective, despite its high profile and large influence [67]. This study showed that the urban design professionals display gender differences that are interesting from both a behavioral and an environmental perspective.

5. Conclusions

Varying degrees of gender differences regarding possibility to influence, perceived importance and feeling of responsibility were detected among urban design professionals for a number of environmental categories in this study linked to the architectural competition ‘A New City Centre for Kiruna’. The largest differences concerned their possibility to influence, to which the participants, especially females, gave rather low ratings. This implies that to increase environmental design in urban planning and design projects, professionals need to increase their actual and perceived possibility to influence environmental aspects, especially among females. Moreover, the gap between participants’ self-rated importance of these issues and their belief in their possibility to influence such issues varied and was larger among female urban design professionals than among males. A large gap between feeling of importance and perceived possibility to influence environmental aspects can potentially cause frustration. Overall, the ranking of responsibility was rather high among both males and females, even when their possibility to influence is rather low. However, other stakeholders were also considered to have high responsibility for the environmental impact of the project and females rated the responsibility of authorities higher in particular. These gender differences regarding internal factors may influence pro-environmental behavior in the planning and design process. Therefore, it is important to highlight and further study gender differences from both an architectural and urban design perspective and an environmental perspective.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/8/4/59/s1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge University of Gävle for funding this study and article.

Author Contributions

Marita Wallhagen conceived the study and designed it together with Ola Eriksson. Marita Wallhagen performed the survey; Marita Wallhagen and Patrik Sörqvist analyzed the data; Marita Wallhagen and Patrik Sörqvist wrote the paper with valuable input from Ola Eriksson.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khasreen, M.; Banfill, P.F.; Menzies, G. Life-Cycle Assessment and the Environmental Impact of Buildings: A Review. Sustainability 2009, 1, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.; Carlton, W.A.; Olsen, D.; Ahmad, I. Building information modeling for sustainable design and LEED® rating analysis. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kats, G.; Alevantis, L.; Berman, A.; Mills, E.; Perlman, J. The Costs and Financial Benefits of Green Buildings: A Report to California’s Sustainable Building Task Force; The Sustainable Building Task Force and Capital E: California, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Henn, R. Overcoming the social and psychological barriers to green building. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 390–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Pitts, A.; Ward, I. Paper 132: Sustainability related educational programmes for sustainable housing design. In Proceedings of the PLEA 2008–25th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Dublin, Ireland, 22–24 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elforgani, M.S.; Rahmat, I. An investigation of factors influencing design team attributes in green buildings. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 7, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocker, J.; Eckberg, D. Gender and Environmentalism: Results from the 1993 General Social Survey. Soc. Sci. Q. 1997, 78, 841–858. [Google Scholar]

- Blocker, J.; Eckberg, D. Environmental Issues as Women’s Issues: General Concerns and Local Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 1989, 70, 586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, I.; Penner, B.; Rendell, J. Who cares about ecology? Personality and sex differences in environmental concern. J. Personal. 1978, 46, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Freudenburg, W.R. Gender and environmental risk concerns: A review and analysis of available research. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 302–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Kalof, L.; Stern, P.C. Gender, values, and environmentalism. Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 1, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Thorsson, S.; Eliasson, I. Climate change: Concerns, beliefs and emotions in residents, experts, decision makers, tourists, and tourist industry. Am. J. Clim. Chang. 2013, 2, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Park, N.-K.; Han, J.H. Gender differences in environmental attitude and behaviors in adoption of energy-efficient lighting at home. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McStay, J.; Dunlap, R. Male-Female Differences in Concern for Environmental Quality. Int. J. Womens Stud. 1983, 6, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mohai, P. Men, Women, and the Environment: An Examination of the Gender Gap in Environmental Concern and Activism. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1992, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai, P. Gender Differences in the Perception of Most Important Environmental Problems. Race Gend. Class 1997, 5, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Kalof, L. Value orientations, gender, and environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1993, 25, 322–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teal, G.; Loomis, J. Effects of gender and parental status on the economic valuation of increasing wetlands, reducing wildlife contamination and increasing salmon populations. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenzny, L.C.; Chua, P.-P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfinsen, M.; Heidenreich, S. Energy & Gender—A Social Sciences and Humanities Crosscutting Theme Report; Shape Energy: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values. Theory and Empireal Tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Eriksson, O.; von Borgstede, C. The effects of environmental management systems on source separation in the work and home settings. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Factors influencing environmental attitudes and behaviors—A UK case study of household waste management. Environ. Behav. 2007, 4, 435–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N.J. A conceptual framework for understanding and analysing attitudes towards household-waste management. Environ. Plan. 2001, 11, 2025–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgerton, E.; McKechnie, J.; Dunleavy, K. Behavioral determinants of household participation in a home composting scheme. Environ. Behav. 2009, 2, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronsell, A.; Smidfelt Rosqvist, L.; Winslott Hiselius, L. Achieving climate objectives in transport policy by including women and challenging gender norms: The Swedish case. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2016, 10, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsson, J.; Lundqvist, L.J.; Sundström, A. Energy saving in Swedish households. The (relative) importance of environmental attitudes. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5182–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, X.; Luo, J. Determining socio-psychological drivers for rural household recycling behaviour in developing countries—A case study from Wugan, Hunan, China. Environ. Behav. 2011, 6, 848–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. An integrated model of waste management behavior—A test of household recycling and composting intention. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.I. Women in futures research toward a rediscovery of ‘feminine’ principles in architecture and planning. Womens Stud. Int. Q. 1981, 4, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkitekten. Självrannsakan Driver på Jämställdheten [Self-Examination is Driving Gender Equality]; Arkitekten: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza and Nacey Research. The Architectural Profession in Europe 2014—A Sector Study; The Architects Council of Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher, M. ‘Alarm’ as Number of Women Architects Falls for First Time in Nearly a Decade. Available online: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/home/alarm-as-number-of-women-architects-falls-for-first-time-in-nearly-a-decade/8607979.fullarticle (accessed on 16 April 2018).

- Liljebäck, J. (Swedish Association of Architects). Personal communication, 2015.

- Kiruna Kommun (Kiruna Municipality). Program för Arkitekttävling—Ny Stadskärna i Kiruna, [Architecture competition programme—A New City Centre for Kiruna]; Kiruna Kommun: Kiruna, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kiruna Kommun (Kiruna Municipality). Kommunfakta (Municiplity Facts). Available online: http://www.kiruna.se/Kommun/Kommun-politik/Kommunfakta/ (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Wallhagen, M.; Malmqvist, T.; Eriksson, O. Professionals’ knowledge and use of environmental assessment in an architectural competition. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 45, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Green Building Council. LEED v4 for Neighborhood Development—Current Version; United States Green Building Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- BRE. BREEAM Communities Technical Manual SD202 0.1.2012. Available online: http://www.breeam.com/bre_PrintOutput/BREEAM_Communities_0_1.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2016).

- Japan Sustainable Building Consortium (JSBC). CASBEE for Urban Development—Technical Manual, 2014 ed.; Institute for Building Environment and Energy Conservation (IBEC): Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wallhagen, M.; Glaumann, M.; Eriksson, O.; Westerberg, U. Framework for Detailed Comparison of Building Environmental Assessment Tools. Buildings 2013, 3, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey Inc. SurveyMonkey; SurveyMonkey Inc: Paolo Alto, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, B.; Wilson, F.M. Women Architects and Their Discontents. Archit. Theory Rev. 2012, 17, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caven, V. Constructing a career: Women architects at work. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Tancred, P. Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Graff-Johnson, A.; Manley, S.; Greed, C. Why Do Women Leave Architecture? RIBA; University of West of England Research Project: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lundeberg, M.A.; Fox, P.W.; Punccohar, J. Highly Confident but Wrong: Gender Differences and Similarities in Confidence Judgments. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 81, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M. The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusdottir, G.L.; Kronsell, A. The (In) Visibility of Gender in Scandinavian Climate Policy-Making. Int. Fem. J. Politics 2015, 17, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymén, C.; Andersson, M.; Langlais, R. Gendered dimensions of climate change response in Swedish municipalities. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, F. Klimatfrågans lösning kräver ett genusperspektiv [The answer to climate change needs a gender perspective]. Genusperspektiv 2008, 2, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, S. Will it hurt less if I can control it? A complex answer to a simple question. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 90, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, H. Genius, gender and architecture: The star system as exemplified in the Pritzker Prize. Archit. Theory Rev. 2012, 17, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewson, G. “Nothing Else Will Do”: The Call for Gender Equality in Architecture in Britain. Archit. Theory Rev. 2012, 17, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, I.; Penner, B.; Rendell, J. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell, S.; Allan, N. Limited Visibility: Portraits of Women Architects. Archit. Theory Rev. 2012, 17, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caven, V.; Astor, E.N. The potential for gender equality in architecture: An Anglo-Spanish comparison. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäcklund, A.-K. Fair Shared Cities—The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 2210–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, T.; Larsson, A. Steg Framåt. Strategier och Villkor för att Förverkliga Genusperspektivet i Översiktlig Planering; Department of Social and Economic Geography, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Roberts, M. Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2013; pp. 1–338. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, K.J.C.; Dainty, A.R.J.; Ison, S.G. Gender in the UK architectural profession: (re)producing and challenging hegemonic masculinity. Work Employ. Soc. 2014, 28, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).