A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What is Biophilic Design?

| Direct Experience of Nature | Indirect Experience of Nature | Experience of Space and Place |

|---|---|---|

| Light | Images of Nature | Prospect and refuge |

| Air | Natural materials | Organized complexity |

| Water | Natural colours | Integration of parts to wholes |

| Plants | Simulating natural light and air | Transitional spaces |

| Animals | Naturalistic shapes and forms | Mobility and wayfinding |

| Weather | Evoking nature | Cultural and ecological attachment to place |

| Natural landscapes and ecosystems | Information richness | - |

| Fire | Age, change and the patina of time | - |

| - | Natural geometries | - |

| - | Biomimicry | - |

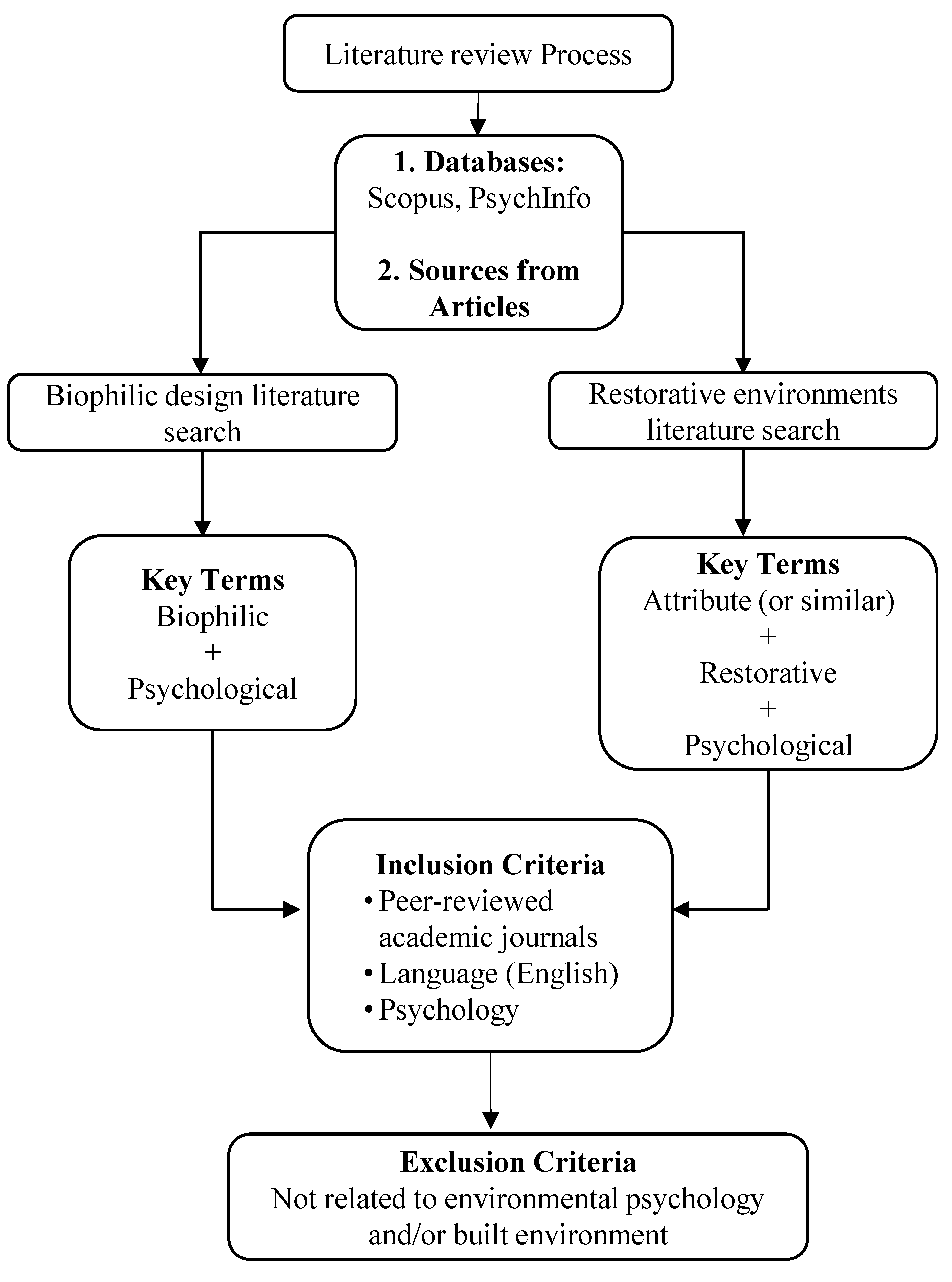

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Direct Experience of Nature

4.1.1. Natural Light

4.1.2. Water

4.1.3. Plants

4.1.4. Weather

4.1.5. Natural Landscapes and Ecosystems

4.2. Indirect Experience of Nature

4.2.1. Images of Nature

4.2.2. Natural Materials

4.2.3. Natural Geometries

4.3. Experience of Space and Place

4.3.1. Prospect and Refuge

4.3.2. Cultural and Ecological Attachment to Place

5. Individual Differences

6. Current Trends in Biophilic Design

7. Conclusions

7.1. Biophilic Design is not a One Size Fits all Approach

7.2. Suggested Areas for Further Research in Restorative Environments

7.3. Suggested Areas for Further Research on Biophilic Design

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kellert, S.R. Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MS, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Living Building ChallengeSM 3.0: A Visionary Path to a Regenerative Future. Available online: https://living-future.org/sites/default/files/reports/FINAL%20LBC%203_0_WebOptimized_low.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2015).

- WELL Building Standard Resources. Available online: http://www.wellcertified.com/standard (accessed on 5 August 2015).

- Terrapin Collaborates with Organizations to Challenge Assumptions and Develop Solutions that Lead to Improved Environmental and Financial Performance through Research, Planning, Guidelines, and Product Development. Available online: http://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2015).

- Humman Spaces. Available online: http://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com (accessed on 23 August 2015).

- Bowler, D.; Buying-Ali, L.; Knight, T.; Pullin, A. The Importance of Nature for Health: Is There a Specific Benefit of Contact with Green Space? Available online: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/SR40.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2015).

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, Y.; van den Berg, A.E. Restorative environments. In Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; Steg, L., van den Berg, A.E., de Groot, J.I.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R.; McGunn, L.J. Appraisals of built environments and approaches to building design that pomote well-benig and healthy behavior. In Environmental Psychology: An Introduction; Steg, L., van den Berg, A.E., de Groot, J.I.M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.O.; Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J.O.; Andrews, S.L.; Kallianpurkar, N.B. Emerging nature-based parameters for health and well-being in the built environment. Int. J. Archit. Res. 2014, 8, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, T.; Birrell, C. Are biophilic-designed site office buildings linked to health benefits and high performing occupants? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12204–12222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joye, Y. Architectural lessons from environmental psychology: The case of biophilic architecture Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design. Available online: http://humanspaces.com/2015/06/01/nature-by-design-the-practice-of-biophilic-design/ (accessed on 23 August 2015).

- Hartig, T.; Bringslimark, T.; Patil, G.G. Restorative Environmental Design: What, When, Where and for Whom? In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Kellert, S.R., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Küller, R.; Lindsten, C. Health and behavior of children in classrooms with and without windows. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beute, F.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Salutogenic effects of the environment: Review of health protective effects of nature and daylight. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beute, F.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Let the sun shine! Measuring explicit and implicit preference for environments differing in naturalness, weather type and brightness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, R.S.; Shepley, M.M.; Williams, G.; Chung, S.S.E. The impact of windows and daylight on acute-care nurses’ physiological, psychological, and behavioral health. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2014, 7, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarsson, J.J.; Wiens, S.; Nilsson, M.E. Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, S.; Stavridou, A. Influence of environmental preference and environment type congruence on judgments of restoration potential. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, S.; Kistemann, T. The impact of blue space on human health and well-being–Salutogenetic health effects of inland surface waters: A review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Adams, J.; Deal, B.; Kweon, B.S.; Tyler, E. Plants in the workplace: The effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.; Knight, C.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, S.A. The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: Three field experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2014, 20, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Sun, C.; Zhou, X.; Leng, H.; Lian, Z. The effect of indoor plants on human comfort. Indoor Build. Environ. 2014, 23, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Zhu, R. Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on cognitive task performances. Science 2009, 323, 1226–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R. View through a window may influence recovery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsten, G. Where to take a study break on the college campus: An attention restoration theory perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.V.; Gatersleben, B. Greenery on residential buildings: Does it affect preferences and perceptions of beauty. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Williams, K.J.H.; Sargent, L.D.; Williams, N.S.G.; Johnson, K.A. 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A comparison of the restorative effect of a natural environment with that of a simulated natural environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. Adaptation to windowlessness: Do office workers compensate for a lack of visual access to the outdoors? Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrud, A.Q.; Bringslimark, T.; Bysheim, K. Benefits from wood interior in a hospital room: A preference study. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2014, 57, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerhall, C.M.; Purcell, T.; Taylor, R. Fractal dimension of landscape silhouette outlines as a predictor of landscape preference. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamps, A.E. Some findings on prospect and refuge: I1. Percept. Mot. Skills 2008, 106, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamps, A.E. Some findings on prospect and refuge: II1. Percept. Mot. Skills 2008, 107, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, B.S.; Nasar, J.L. Fear of crime in relation to three exterior site features prospect, refuge, and escape. Environ. Behav. 1992, 24, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Andrews, M. When walking in nature is not restorative—The role of prospect and refuge. Health Place 2013, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, P.A.; Greene, T.C.; Fisher, J.D. Environmental Psychology; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H. Stability of self-reported favourite places and place attachment over a 10-month period. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Howes, Y. Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: A wind energy case study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, P.; Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The monastery as a restorative environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Heijne, M. Fear versus fascination: An exploration of emotional responses to natural threats. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, R.D.; Floyd, M.F. Nature is scary, disgusting, and uncomfortable. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, I.-C.; Sullivan, W.C.; Chang, C.-Y. Perceptual evaluation of natural landscapes the role of the individual connection to nature. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.-S.; Ulrich, R.S.; Walker, V.D.; Tassinary, L.G. Anger and stress: The role of landscape posters in an office setting. Environ. Behav. 2007, 40, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of an indoor plant on creative task performance and mood. J. Psychol. 2004, 45, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratcliffe, E.; Gatersleben, B.; Sowden, P.T. Bird sounds and their contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.S.; Browning, W.D. Transforming building practices through biophilic design. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Kellert, S.R., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzy, N.S. Biophilic qualities of historical architecture: In quest of the timeless terminologies of “life” in architectural expression. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 15, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Green Building Trends: Business Benefits Driving New and Retrofit Market Opportunities in over 60 Countries. Available online: http://www.worldgbc.org/files/8613/6295/6420/World_Green_Building_Trends_SmartMarket_Report_2013.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2015).

- International WELL Building Institude: News. Available online: http://www.wellcertified.com/news (accessed on 5 August 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillis, K.; Gatersleben, B. A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings 2015, 5, 948-963. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5030948

Gillis K, Gatersleben B. A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings. 2015; 5(3):948-963. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5030948

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillis, Kaitlyn, and Birgitta Gatersleben. 2015. "A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design" Buildings 5, no. 3: 948-963. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5030948

APA StyleGillis, K., & Gatersleben, B. (2015). A Review of Psychological Literature on the Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Biophilic Design. Buildings, 5(3), 948-963. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings5030948