Developing a Health-Oriented Assessment Framework for Office Interior Renovation: Addressing Gaps in Green Building Certification Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Process

2.2. Indicator Identification and Expert Consultation

2.3. Hierarchical Structuring and Weight Calculation

- (1)

- Level 1 represents the overall goal of health-oriented interior renovation assessment;

- (2)

- Level 2 includes four major dimensions (Environmental Quality, Safety Management, Functional Usability, and Resource Efficiency & Circularity);

- (3)

- Level 3 consists of 18 specific health-oriented indicators under the corresponding dimensions.

2.4. Fuzzy Delphi Method for Indicator Screening

2.5. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Weighting Analysis

- (1)

- the overall goal of health-oriented interior renovation assessment;

- (2)

- four major assessment dimensions;

- (3)

- the 18 finalized indicators obtained from the Fuzzy Delphi process.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Assessment Dimensions and Indicators

3.2. Weighting Results of Major Dimensions

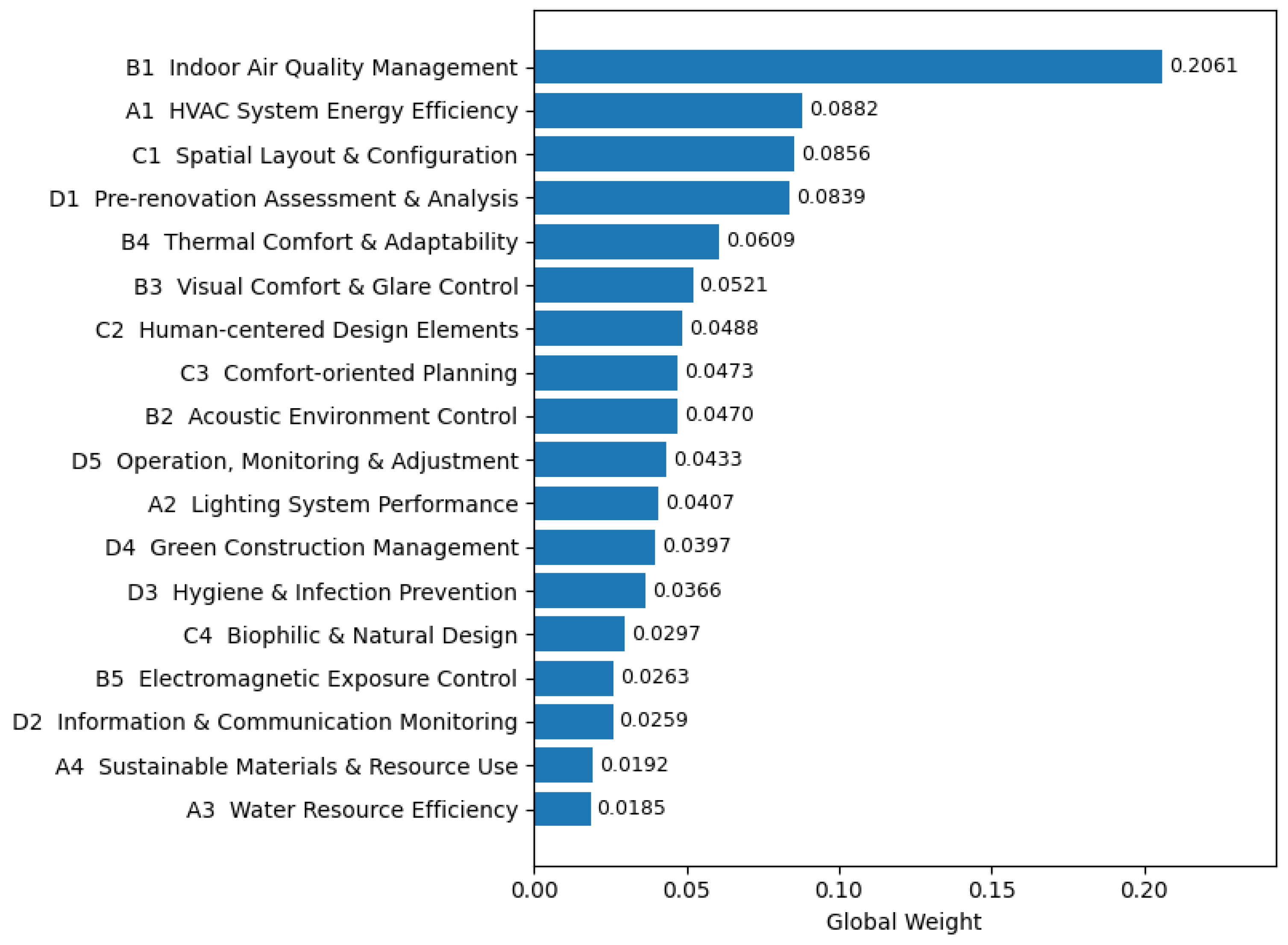

3.3. Ranking of Health-Oriented Interior Renovation Indicators

3.4. Robustness and Stability of the AHP Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Interior Renovation Practice

4.2. Comparison with Existing Certification Systems

4.3. Policy and Management Implications

4.4. Research Limitations and Future Research

4.5. Illustrative Application of the Framework

- (1)

- Defining renovation alternatives;

- (2)

- Scoring each alternative against the 18 indicators;

- (3)

- Calculating weighted composite scores;

- (4)

- Supporting trade-off decisions under budget and operational constraints.

4.6. Illustrative Application of the Proposed Framework

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pomponi, F.; Farr, E.R.P.; Piroozfar, P.; Gates, J.R. Façade refurbishment of existing office buildings: Do conventional energy-saving interventions always work? J. Build. Eng. 2015, 3, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuivjõgi, H.; Uutar, A.; Kuusk, K.; Thalfeldt, M.; Kurnitski, J. Market based renovation solutions in non-residential buildings–Why commercial buildings are not renovated to NZEB. Energy Build. 2021, 248, 111169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Ding, G.; Runeson, G.; Liu, Y. Sustainable Buildings’ Energy-Efficient Retrofitting: A Study of Large Office Buildings in Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Pizzol, M.; McLaren, S.J.; Vignes, M.; Dowdell, D. Refurbishment of office buildings in New Zealand: Identifying priorities for reducing environmental impacts. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. The changing nature of the workplace and the future of office space. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2015, 33, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.; Williams, B. Effective churn management for business. J. Corp. Real Estate 2005, 7, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, P.; Wilkinson, S. Measuring office fit-out changes to determine recurring embodied energy in building life cycle assessment. Facilities 2015, 33, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, P. Quantifying the recurring nature of fitout to assist LCA studies in office buildings. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2017, 35, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooymans, R.; Abbott, J. Developing an effective service life asset management and valuation model. J. Corp. Real Estate 2006, 8, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, N.; Gibson, V.; Murdoch, S. UK Commercial Property Lease Structures: Landlord and Tenant Mismatch. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1487–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, J. Accommodating change—Emerging real estate strategies. J. Corp. Real Estate 2001, 3, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, N.; Zuo, J.; Mao, R.; Gao, X.; Duan, H. Characterizing the generation and flows of building interior decoration and renovation waste: A case study in Shenzhen City. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Z. Green building for office interiors: Challenges and opportunities. Facilities 2016, 34, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nase, I.; Berry, J.; Adair, A. Real estate value and quality design in commercial office properties. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2013, 6, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasik, V.; Escott, E.; Bates, R.; Carlisle, S.; Faircloth, B.; Bilec, M.M. Comparative whole-building life cycle assessment of renovation and new construction. Build. Environ. 2019, 161, 106218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeel, W.S.E.; Alamoudy, F.O.; Sameh, R. How renovation activities may jeopardise indoor air quality: Accounting for short and long-term symptoms of sick building syndrome in educational buildings. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2023, 19, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, J.; Jung, C. Evaluating the Indoor Air Quality after Renovation at the Greens in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Buildings 2021, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeel, W.S.E.; Mohamed, A.G. Indoor air quality for sustainable building renovation: A decision-support assessment system using structural equation modelling. Build. Environ. 2022, 214, 108933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, W.; Mainka, A.; Brągoszewska, E. Impact of ventilation system retrofitting on indoor air quality in a single-family building. Build. Environ. 2024, 262, 111830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad Alomirah, H.; Moda, H.M. Assessment of Indoor Air Quality and Users Perception of a Renovated Office Building in Manchester. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, A.M.; Obeidat, A.M. Interior Design Strategies for Improving Quality of Life: How Can Residential Spaces Reflect a Healthy Lifestyle and Psychological Comfort. Int. J. Hous. Sci. Its Appl. 2024, 45, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Katafygiotou, M.; Mazroei, A.; Kaushik, A.; Elsarrag, E. Impact of indoor environmental quality on occupant well-being and comfort: A review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha-Hossein, M.M.; El-Jouzi, S.; Elmualim, A.A.; Ellis, J.; Williams, M. Post-occupancy studies of an office environment: Energy performance and occupants’ satisfaction. Build. Environ. 2013, 69, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, N.; Sztuka, I.M.; Pohlmann, K.; Sudimac, S.; Kühn, S. The Living Space: Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Response to Interiors Presented in Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candido, C.; Gocer, O.; Marzban, S.; Gocer, K.; Thomas, L.; Zhang, F.; Gou, Z.; Mackey, M.; Engelen, L.; Tjondronegoro, D. Occupants’ satisfaction and perceived productivity in open-plan offices designed to support activity-based working: Findings from different industry sectors. J. Corp. Real Estate 2021, 23, 106–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongisto, V.; Haapakangas, A.; Varjo, J.; Helenius, R.; Koskela, H. Refurbishment of an open-plan office–Environmental and job satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, J.J.; Jofeh, C.; Aguilar, A.-M. Improving Occupant Wellness in Commercial Office Buildings through Energy Conservation Retrofits. Buildings 2015, 5, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Remøy, H.; Van Den Dobbelsteen, A. User-focused office renovation: A review into user satisfaction and the potential for improvement. Prop. Manag. 2019, 37, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwisy, A.; BuHamdan, S.; Gül, M. Criteria-based ranking of green building design factors according to leading rating systems. Energy Build. 2018, 178, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.N.; Jensen, R.L.; Larsen, T.S.; Nissen, S.B. Early stage decision support for sustainable building renovation–A review. Build. Environ. 2016, 103, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lai, J. Performance assessment of residential building renovation: A scientometric analysis and qualitative review of literature. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 14, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibang Bi Obam Assoumou, S.S.; Zhu, L.; Khayeka-Wandabwa, C. Healthy building standards, their integration into green building practices and rating systems for one health. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, E. Built Environment and Wellbeing—Standards, Multi-Criteria Evaluation Methods, Certifications. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Wargocki, P.; Chan, Y.-H.; Chen, L.; Tham, K.-W. How does indoor environmental quality in green refurbished office buildings compare with the one in new certified buildings? Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A.; Wargocki, P.; Rismanchi, B. Ten questions concerning green buildings and indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 2017, 112, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouf, A.M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Framework to evaluate quality performance of green building delivery: Construction and operational stage. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.E. Evaluating design strategies, performance and occupant satisfaction: A low carbon office refurbishment. Build. Res. Inf. 2010, 38, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuman, N.; Marinič, M.; Kuhta, M. A Methodological Framework for Sustainable Office Building Renovation Using Green Building Rating Systems and Cost-Benefit Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Villegas, R.; Eriksson, O.; Olofsson, T. Assessment of renovation measures for a dwelling area–Impacts on energy efficiency and building certification. Build. Environ. 2016, 97, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashdan, W.; Ashour, A.F. Exploring Sustainability in Interior Design: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-G.; Wang, R.-J.; Lo, S.-C.; Yau, J.-T.; Wu, Y.-W. Construction Cost of Green Building Certified Residence: A Case Study in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, M.; Mahdiyar, A.; Haron, S.H. A Comprehensive Review of Deterrents to the Practice of Sustainable Interior Architecture and Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi Nia, E.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J. Analysis of Occupant Behaviours in Energy Efficiency Retrofitting Projects. Land 2022, 11, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-de-Guinoa, A.; Zambrana-Vasquez, D.; Fernández, V.; Bartolomé, C. Circular Economy in the European Construction Sector: A Review of Strategies for Implementation in Building Renovation. Energies 2022, 15, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Ren, R.; Li, L. Existing Building Renovation: A Review of Barriers to Economic and Environmental Benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-A.; Su, F.-I.; Sun, C.-Y. Cost and Incentive Analysis of Green Building Label Upgrades in Taiwan’s Residential Sector: A Case Study of Silver to Gold EEWH Certification. Buildings 2025, 15, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-T.; Huang, L.-C.; Lin, H.-J. The fuzzy Delphi method via fuzzy statistics and membership function fitting and an application to the human resources. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2000, 112, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Amagasa, M.; Shiga, T.; Tomizawa, G.; Tatsuta, R.; Mieno, H. The max-min Delphi method and fuzzy Delphi method via fuzzy integration. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1993, 55, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Application of fuzzy Delphi method (FDM) and fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP) to criteria weights for fashion design scheme evaluation. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2013, 25, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; Kamaruzzaman, S.N.; Baharum, M.R. Ranking the indicators of building performance and the users’ risk via Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP): Case of Malaysia. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, R.F.M.; Mourshed, M. Urban sustainability assessment framework development: The ranking and weighting of sustainability indicators using analytic hierarchy process. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Zakaria, R.; Ibrahim, O.; Majid, M.Z.A.; Mohamad Zin, R.; Chugtai, M.W.; Zainal Abidin, N.I.; Sahamir, S.R.; Aminu Yakubu, D. A knowledge-based expert system for assessing the performance level of green buildings. Knowl. Based Syst. 2015, 86, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelAzim, A.I.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Aboul-Zahab, E.M. Development of an energy efficiency rating system for existing buildings using Analytic Hierarchy Process–The case of Egypt. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorramshahgol, R.; Moustakis, V.S. Delphic hierarchy process (DHP): A methodology for priority setting derived from the Delphi method and analytical hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1988, 37, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kalantari, M.; Rajabifard, A. Identifying and prioritizing sustainability indicators for China’s assessing demolition waste management using modified Delphi–analytic hierarchy process method. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-W.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, J.C.; Shen, Z.-H. Developing indicators for sustainable campuses in Taiwan using fuzzy Delphi method and analytic hierarchy process. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.-C.; Chen, J.-W.; Dong, Y.-W.; Lu, C.-L.; Chiou, Y.-T. Developing Indicators for Healthy Building in Taiwan Using Fuzzy Delphi Method and Analytic Hierarchy Process. Buildings 2023, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, S.-L.; Sun, Y.; Gao, M.; Hu, X.; Meen, T.-H. Delphi and Analytical Hierarchy Process Fuzzy Model for Auxiliary Decision-making for Cross-field Learning in Landscape Design. Sens. Mater. 2022, 34, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Tan, H.P.; Gan, S.W. Constructing a student development model for undergraduate vocational universities in China using the Fuzzy Delphi Method and Analytic Hierarchy Process. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, L.-A.; Marle, F.; Bocquet, J.-C. Using a Delphi process and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the complexity of projects. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5388–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpeh, E.K.; Pillay, J.-P.G.; Ndihokubwayo, R.; Nalumu, D.J. Improving energy efficiency of HVAC systems in buildings: A review of best practices. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2022, 40, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Z.; Köse, A. Evaluation of WELL Certificate in terms of Energy Efficiency and Sustainability in Educational Buildings. Int. J. New Find. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025, 54–65. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ijonfest/article/1736647#article_cite (accessed on 26 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Persily, A.K.; Emmerich, S.J. Indoor air quality in sustainable, energy efficient buildings. Hvac R Res. 2012, 18, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R. A review of HVAC systems requirements in building energy regulations. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, O.; Monteiro, E.; Brito, P.; Romano, P. Measurement and classification of energy efficiency in HVAC systems. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, N.; Badiei, M.; Mohammad, M.; Razali, H.; Rajabi, A.; Chin Haw, L.; Jameelah Ghazali, M. Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X. Effectiveness of indoor environment quality in LEED-certified healthcare settings. Indoor Built Environ. 2016, 25, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Wargocki, P.; Chan, Y.H.; Chen, L.; Tham, K.W. Indoor environmental quality, occupant satisfaction, and acute building-related health symptoms in Green Mark-certified compared with non-certified office buildings. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, G.; Martirano, L.; Di Ponio, S. Energy performance of interior lighting systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2013, 49, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X. Study of indoor environmental quality and occupant overall comfort and productivity in LEED-and non-LEED–certified healthcare settings. Indoor Built Environ. 2018, 27, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimlyat, P.S. Indoor environmental quality performance and occupants’ satisfaction [IEQPOS] as assessment criteria for green healthcare building rating. Build. Environ. 2018, 144, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.A.; Newsham, G.R. Lighting quality and energy-efficiency effects on task performance, mood, health, satisfaction, and comfort. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 1998, 27, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Afonso, A.; Rodrigues, C. Water efficiency of products and buildings: The implementation of certification and labelling measures in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on CIB W062 Water Supply and Drainage for Buildings, Hong Kong, China, 8–10 September 2008; pp. 230–240. Available online: https://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB11776.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Wiengarten, F.; Humphreys, P.; Onofrei, G.; Fynes, B. The adoption of multiple certification standards: Perceived performance implications of quality, environmental and health & safety certifications. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Eldeeb, A.; Elantary, A. Examining Sustainable Materials: Enhancing Indoor Air Quality for Office Interiors. Emir. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 30, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Ramalho, O.; Mandin, C. Indoor air quality requirements in green building certifications. Build. Environ. 2015, 92, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Kuo, W.C.; Chiang, C.M.; Liu, K.S.; Nieh, C.K. A study on the impact of different application ratios of ultra-low emission green building materials on human health in indoor environments. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 271, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Indoor decorating and refurbishing materials and furniture volatile organic compounds emission labeling systems: A review. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 2533–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Abdelaziz Mahmoud, N.S.; Al Qassimi, N.; Elsamanoudy, G. Preliminary study on the emission dynamics of TVOC and formaldehyde in homes with eco-friendly materials: Beyond green building. Buildings 2023, 13, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S. From Efficiency to Sustainability: A Review of Low-Emission Glass. Adv. Stand. Appl. Sci. 2025, 3, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, G.; Yu, X.; Fang, L.; Wang, Q.; Tanaka, T.; Amano, K.; Yang, X. A review and comparison of the indoor air quality requirements in selected building standards and certifications. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Srinivasan, R. A systematic review of air quality sensors, guidelines, and measurement studies for indoor air quality management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, M.; Chau, C.K.; Lee, W.L. Assessing the benefit and cost for a voluntary indoor air quality certification scheme in Hong Kong. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 320, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.-T. Overview of green building material (GBM) policies and guidelines with relevance to indoor air quality management in Taiwan. Environments 2017, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffell, J.; Nehr, S. Improving indoor air quality through standardization. Standards 2023, 3, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licina, D.; Langer, S. Indoor air quality investigation before and after relocation to WELL-certified office buildings. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresin, S.; Aletta, F.; Babich, F.; Bourdeau, E.; Harvie-Clark, J.; Kang, J.; Lavia, L.; Radicchi, A.; Albatici, R. Acoustics for supportive and healthy buildings: Emerging themes on indoor soundscape research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.; Pitarma, R. A real-time noise monitoring system based on internet of things for enhanced acoustic comfort and occupational health. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 139741–139755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.B.; Himmel, C.N. Acoustical and noise control criteria and guidelines for building design and operations. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference for Enhanced Building Operations, Austin, TX, USA, 17–19 November 2009; Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/62965881-4f31-4c93-8274-47858a9c244f/content (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Yaman, M.; Ulukavak Harputlugil, G.; Kurtay, C. A holistic approach to different regulations for acoustic improvements in industrial facilities. Noise Vib. Worldw. 2024, 55, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, S.-K. Indoor environmental quality in LEED-certified buildings in the U.S. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2008, 7, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresin, S.; Albatici, R.; Aletta, F.; Babich, F.; Oberman, T.; Kang, J. Acoustic design criteria in naturally ventilated residential buildings: New research perspectives by applying the indoor soundscape approach. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurukose Cal, H.; Aletta, F.; Kang, J. Integration of soundscape assessment and design principles into international standards and guidelines for learning environment acoustics. Build. Acoust. 2025, 32, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.; Kim, J.T. Effects of indoor lighting on occupants’ visual comfort and eye health in a green building. Indoor Built Environ. 2011, 20, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, Q.J. Light level, visual comfort and lighting energy savings potential in a green-certified high-rise building. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S. Comparisons of Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Comfort Quality between Certification Levels of LEED-Certified Buildings in USA. Indoor Built Environ. 2011, 20, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomonte, S.; Schiavon, S.; Kent, M.G.; Brager, G. Indoor environmental quality and occupant satisfaction in green-certified buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2019, 47, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, H. Critical insights into thermal comfort optimization and heat resilience in indoor spaces. City Built Environ. 2024, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhao, S.; Gao, S.; Yan, H.; Sun, Z.; Lian, Z.; Duanmu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Comparative analysis of indoor thermal environment characteristics and occupants’ adaptability: Insights from ASHRAE RP-884 and the Chinese thermal comfort database. Energy Build. 2024, 309, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, S.; Bai, L.; de Dear, R.; Yang, L. Review of adaptive thermal comfort models in built environmental regulatory documents. Build. Environ. 2018, 137, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaripadath, D.; Mirzaei, P.A.; Attia, S. Multi-criteria thermal resilience certification scheme for indoor built environments during heat waves. Energy Built Environ. 2025, 6, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Y. Thermal history and adaptation: Does a long-term indoor thermal exposure impact human thermal adaptability? Appl. Energy 2016, 183, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatayneh, A.; Jaradat, M.; AlKhatib, M.B.; Abdallah, R.; Juaidi, A.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. The Significance of the Adaptive Thermal Comfort Practice over the Structure Retrofits to Sustain Indoor Thermal Comfort. Energies 2021, 14, 2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramello, E.; Bonato, M.; Fiocchi, S.; Tognola, G.; Parazzini, M.; Ravazzani, P.; Wiart, J. Radio Frequency Electromagnetic Fields Exposure Assessment in Indoor Environments: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Vazquez, R.; Escobar, I.; Thielens, A.; Arribas, E. Measurements and Analysis of Personal Exposure to Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields at Outdoor and Indoor School Buildings: A Case Study at a Spanish School. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195692–195702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.T.; Alrowais, R.; Lal, R.; Bashir, M.; Sikandar, M.A.; Zahid, N.; Khan, M.M.H.; Saad, S.; Abbas, M.I.; Khan, M.W.; et al. Synergizing Health and Technology in Green Buildings: A Critical Review of Indoor Air Quality Monitoring and Solutions. Indoor Air 2025, 2025, 1281155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. ICNIRP statement on EMF-emitting new technologies. Health Phys. 2008, 94, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftness, V.; Hakkinen, B.; Adan, O.; Nevalainen, A. Elements that contribute to healthy building design. Env. Health Perspect 2007, 115, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, H.; Lahtinen, M.; Lappalainen, S.; Nevala, N.; Knibbs, L.D.; Morawska, L.; Reijula, K. Design approaches for promoting beneficial indoor environments in healthcare facilities: A review. Intell. Build. Int. 2013, 5, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, J.D.; Chen, Q. Indoor air quality factors in designing a healthy building. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2000, 25, 567–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, H.; Lahtinen, M.; Lappalainen, S.; Nevala, N.; Knibbs, L.D.; Morawska, L.; Reijula, K. Physical characteristics of the indoor environment that affect health and wellbeing in healthcare facilities: A review. Intell. Build. Int. 2013, 5, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal, S.; Porter, P.; Clements, N.; Campanella, C.; Zhang, R.; Hovde, K.; Lam, C. Conducting Human-Centered Building Science at the Well Living Lab. Technol. Archit. Des. 2019, 3, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhati, K.; Gottschald, M. Enhancing Fiscal Outcomes through Human-Centered Design: The Economic Benefits of Salutogenic Architecture in Public Health Care Facilities. J. Salut. Archit. 2023, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, G.M.; Horst, R.L. A systems engineering perspective on the human-centered design of health information systems. J. Biomed. Inform. 2005, 38, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rek-Lipczyńska, A. Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Verderber, S. On the Planning and Design of Hospital Circulation Zones:A Review of the Evidence-Based Literature. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2017, 10, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Lee, J.-K. Indoor Walkability Index: BIM-enabled approach to Quantifying building circulation. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldermans, B.; Tenpierik, M.; Luscuere, P. Human Health and Well-Being in Relation to Circular and Flexible Infill Design: Assessment Criteria on the Operational Level. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langiano, E.; Ferrara, M.; Falese, L.; Lanni, L.; Diotaiuti, P.; Di Libero, T.; De Vito, E. Assessment of Indoor Air Quality in School Facilities: An Educational Experience of Pathways for Transversal Skills and Orientation (PCTO). Sustainability 2024, 16, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Paschoalino, M.; Silva, L. Health and Well-Being Benefits of Outdoor and Indoor Vertical Greening Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrč Obrecht, T.; Kunič, R.; Jordan, S.; Dovjak, M. Comparison of Health and Well-Being Aspects in Building Certification Schemes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, L.; Larsen, T.S.; Jensen, R.L.; Larsen, O.K. Framing holistic indoor environment: Definitions of comfort, health and well-being. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 1118–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Green indoor and outdoor environment as nature-based solution and its role in increasing customer/employee mental health, well-being, and loyalty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.G.; Parkinson, T.; Schiavon, S. Indoor environmental quality in WELL-certified and LEED-certified buildings. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.W.F.; Kim, J.T. Building Environmental Assessment Schemes for Rating of IAQ in Sustainable Buildings. Indoor Built Environ. 2011, 20, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tleuken, A.; Tokazhanov, G.; Guney, M.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Karaca, F. Readiness Assessment of Green Building Certification Systems for Residential Buildings during Pandemics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, M.M.; Salvalai, G. A review on Building Renovation Passport: Potentialities and barriers on current initiatives. Energy Build. 2018, 173, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, M.A.; Aljuhani, M.; Hamida, M.B.; Salaheldin, M.H. A Framework for Fire Safety Management in School Facilities. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.L.; Chow, W.-K. Fire safety in modern indoor and built environment. Indoor Built Environ. 2023, 32, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus Salim, N.A.; Salleh, N.M.; Jaafar, M.; Sulieman, M.Z.; Ulang, N.M.; Ebekozien, A. Fire safety management in public health-care buildings: Issues and possible solutions. J. Facil. Manag. 2021, 21, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D. Risk Management and Electrical Safety: Implementation of an Occupational Health and Safety Management System. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2015, 21, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad Salleh, N.; Agus Salim, N.A.; Jaafar, M.; Sulieman, M.Z.; Ebekozien, A. Fire safety management of public buildings: A systematic review of hospital buildings in Asia. Prop. Manag. 2020, 38, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Jang, H.; Yoon, G.; Choi, M.-i.; Kang, B.; Cho, K.; Lee, T.; Park, S. Smart Fire Safety Management System (SFSMS) Connected with Energy Management for Sustainable Service in Smart Building Infrastructures. Buildings 2023, 13, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Review of Communication Technology in Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System and Challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdhous, M.F.M.; Sudantha, B.H.; Karunaratne, P.M. IoT enabled proactive indoor air quality monitoring system for sustainable health management. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Computing and Communications Technologies (ICCCT), Chennai, India, 23–24 February 2017; pp. 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, G.; Pitarma, R. An Indoor Monitoring System for Ambient Assisted Living Based on Internet of Things Architecture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Zheng, X.; Villalba-Díez, J.; Ordieres-Meré, J. Indoor Air-Quality Data-Monitoring System: Long-Term Monitoring Benefits. Sensors 2019, 19, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivani Maddala, V.K. Green pest management practices for sustainable buildings: Critical review. Sci. Prog. 2019, 102, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; Hazard, K.; Moser, D.; Cox, D.; Rose, R.; Alkon, A. An Integrated Pest Management Intervention Improves Knowledge, Pest Control, and Practices in Family Child Care Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol, N.N.; Ramli, N.A.; Mohammad, I.S.; Sukereman, A.S.; Sulaiman, M.A. Assessing measurement model of green cleaning components for green buildings. J. Facil. Manag. 2023, 21, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Laurent, J.G.C.; Flanigan, S.S.; Eitland, E.S.; Spengler, J.D. Green Buildings and Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallawaarachchi, H.; De Silva, L.; Rameezdeen, R. Indoor environmental quality and occupants’ productivity: Suggestions to enhance national green certification criteria. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2016, 6, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukcinar, R.A.; Komurlu, R.; Arditi, D. Green-Certified Healthcare Facilities from a Global Perspective: Advanced and Developing Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, T.; Parkinson, A.; de Dear, R. Continuous IEQ monitoring system: Performance specifications and thermal comfort classification. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin Beigh, F.; Rasool Shah, S.; Ahmad, K. A Perspective on Indoor Air Quality Monitoring, Guidelines, and the Use of Various Sensors. Environ. Forensics 2025, 26, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitarma, R.; Marques, G.; Ferreira, B.R. Monitoring Indoor Air Quality for Enhanced Occupational Health. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 41, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Professional Background | Title | Experience (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Green building consultant | Company head | 25 |

| 2 | Society of IEQ | Chairman | 30 |

| 3 | Association of Interior Design | Chairman | 35 |

| 4 | Interior Design | Company head | 25 |

| 5 | Interior Design | Company head | 20 |

| 6 | Green building consultant | Director | 35 |

| 7 | Interior Design | Director | 35 |

| 8 | Green building consultant | Senior Manager | 25 |

| 9 | Green building consultant | CEO | 15 |

| 10 | Green building consultant | Company head | 15 |

| Professional Category | Areas of Expertise | Number of Experts | Key Qualifications/Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Building and Certification Experts | Smart and green building systems, IEQ, certification assessment | 4 | Senior roles in green building associations; experience in GD, IEQ, and healthy building assessment |

| Architects and Building Designers | Architectural design, interior renovation, LEED-accredited practice | 4 | Licensed architects and mechanical engineers; LEED AP and WELL AP credentials |

| Interior Renovation Professionals | Interior design, construction coordination, renovation project management | 4 | Senior managers and design leads in interior renovation firms |

| Property and Facility Management Professionals | Office building operation, asset management, facility management | 5 | Extensive experience in office property and facility management |

| Energy and Sustainability Consultants | Energy efficiency, carbon reduction, green retrofit consulting | 3 | Engineers and consultants specializing in energy-saving and carbon mitigation strategies |

| Total | 20 |

| Dimension | Code | Initial Indicator (Derived from Literature) | Consensus Result (1~9) | Retained for AHP | Key Literature Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Quality | A1 | Energy efficiency of Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems | 6.24 | Yes | [61,62,63,64,65,66] |

| A2 | Lighting system performance | 5.94 | Yes | [67,68,69,70,71,72] | |

| A3 | Water efficiency performance | 5.14 | Yes | [62,67,68,73,74] | |

| A4 | Use of green and low-emission materials | 5.92 | Yes | [75,76,77,78,79,80] | |

| IEQ | B1 | Indoor air quality management | 6.40 | Yes | [76,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| B2 | Acoustic environment control | 5.41 | Yes | [67,87,88,89,90,91,92,93] | |

| B3 | Visual comfort and lighting quality | 5.72 | Yes | [67,68,70,91,94,95,96,97] | |

| B4 | Thermal comfort and adaptability | 5.24 | Yes | [98,99,100,101,102,103] | |

| B5 | Electromagnetic environment control | 5.13 | Yes | [104,105,106,107] | |

| Functional Usability | C1 | Spatial layout and configuration | 5.81 | Yes | [67,70,91,108,109,110,111] |

| C2 | Human-centered design elements | 4.88 | Yes | [112,113,114,115] | |

| C3 | Circulation and movement planning | 5.45 | Yes | [116,117,118,119] | |

| C4 | Natural lighting and interior greening | 4.99 | Yes | [13,67,68,94,115,120] | |

| C * | Support for psychological well-being | 4.80 | No (Excluded) | [24,33,121,122,123,124] | |

| Safety Management | D1 | Preliminary assessment and renovation planning | 6.50 | Yes | [16,17,125,126,127] |

| D * | Electrical and fire safety management | 4.59 | No (Excluded) | [128,129,130,131,132,133] | |

| D2 | Information and communication system monitoring | 6.02 | Yes | [134,135,136,137] | |

| D3 | Maintenance, cleaning, and pest control | 5.21 | Yes | [108,138,139,140,141] | |

| D4 | Green construction management | 5.99 | Yes | [32,68,76,84,142,143] | |

| D5 | Operation monitoring and adjustment | 6.69 | Yes | [82,137,144,145,146] |

| Rank | Code | Indicator | Global Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B1 | Indoor air quality management | 0.2061 |

| 2 | A1 | Energy efficiency of HVAC systems | 0.0882 |

| 3 | C1 | Spatial layout and configuration | 0.0856 |

| 4 | D1 | Preliminary assessment and renovation planning | 0.0839 |

| 5 | B4 | Thermal comfort and adaptability | 0.0609 |

| 6 | B3 | Visual comfort and lighting quality | 0.0521 |

| 7 | C2 | Human-centered design elements | 0.0488 |

| 8 | C3 | Circulation and movement planning | 0.0473 |

| 9 | B2 | Acoustic environment control | 0.0470 |

| 10 | D5 | Operation monitoring and adjustment | 0.0433 |

| 11 | A2 | Lighting system performance | 0.0407 |

| 12 | D4 | Green construction management | 0.0397 |

| 13 | D3 | Maintenance, cleaning, and pest control | 0.0366 |

| 14 | C4 | Natural lighting and interior greening | 0.0297 |

| 15 | B5 | Electromagnetic environment control | 0.0263 |

| 16 | D2 | Information and communication system monitoring | 0.0259 |

| 17 | A4 | Use of green and low-emission materials | 0.0192 |

| 18 | A3 | Water efficiency performance | 0.0185 |

| Dimension (Weight) | Code | Indicator | Global Weight | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Efficiency & Circularity (16.67%) | A1 | Energy efficiency of HVAC systems | 0.0882 | 2 |

| A2 | Lighting system performance | 0.0407 | 11 | |

| A3 | Water efficiency performance | 0.0185 | 18 | |

| A4 | Use of green and low-emission materials | 0.0192 | 17 | |

| Environmental Quality (39.24%) | B1 | Indoor air quality management | 0.2061 | 1 |

| B2 | Acoustic environment control | 0.0470 | 9 | |

| B3 | Visual comfort and lighting quality | 0.0521 | 6 | |

| B4 | Thermal comfort and adaptability | 0.0609 | 5 | |

| B5 | Electromagnetic environment control | 0.0263 | 15 | |

| Functional Usability (21.14%) | C1 | Spatial layout and configuration | 0.0856 | 3 |

| C2 | Human-centered design elements | 0.0488 | 7 | |

| C3 | Circulation and movement planning | 0.0473 | 8 | |

| C4 | Natural lighting and interior greening | 0.0297 | 14 | |

| Safety Management (22.95%) | D1 | Preliminary assessment and renovation planning | 0.0839 | 4 |

| D2 | Information and communication system monitoring | 0.0259 | 16 | |

| D3 | Maintenance, cleaning, and pest control | 0.0366 | 13 | |

| D4 | Green construction management | 0.0397 | 12 | |

| D5 | Operation monitoring and adjustment | 0.0433 | 10 |

| Dimension (Level 1) | Weight (%) | Rank | Indicator Code | Health-Oriented Indicator | Global Weight | Overall Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Quality | 39.24 | 1 | B1 | Indoor Air Quality Management | 0.2061 | 1 |

| A1 | HVAC System Energy Efficiency | 0.0882 | 2 | |||

| C1 | Spatial Layout and Configuration | 0.0856 | 3 | |||

| D1 | Pre-renovation Assessment and Analysis | 0.0839 | 4 | |||

| B4 | Thermal Comfort and Adaptability | 0.0609 | 5 | |||

| Safety Management | 22.95 | 2 | B3 | Visual Comfort and Glare Control | 0.0521 | 6 |

| C2 | Human-Centered Design Elements | 0.0488 | 7 | |||

| C3 | Comfort-Oriented Planning | 0.0473 | 8 | |||

| B2 | Acoustic Environment Control | 0.0470 | 9 | |||

| D5 | Operation, Monitoring, and Adjustment | 0.0433 | 10 | |||

| Functional Usability | 21.14 | 3 | A2 | Lighting System Performance | 0.0407 | 11 |

| D4 | Green Construction Management | 0.0397 | 12 | |||

| D3 | Hygiene and Infection Prevention | 0.0366 | 13 | |||

| C4 | Biophilic and Natural Design | 0.0297 | 14 | |||

| Resource Efficiency | 16.67 | 4 | B5 | Electromagnetic Exposure Control | 0.0263 | 15 |

| D2 | Information and Communication Monitoring | 0.0259 | 16 | |||

| A4 | Sustainable Materials and Resource Use | 0.0192 | 17 | |||

| A3 | Water Resource Efficiency | 0.0185 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chu, H.-W.; Tsai, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-A.; Sun, C.-Y. Developing a Health-Oriented Assessment Framework for Office Interior Renovation: Addressing Gaps in Green Building Certification Systems. Buildings 2026, 16, 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030635

Chu H-W, Tsai H-C, Chen Y-A, Sun C-Y. Developing a Health-Oriented Assessment Framework for Office Interior Renovation: Addressing Gaps in Green Building Certification Systems. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):635. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030635

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Hung-Wen, Hsi-Chuan Tsai, Yen-An Chen, and Chen-Yi Sun. 2026. "Developing a Health-Oriented Assessment Framework for Office Interior Renovation: Addressing Gaps in Green Building Certification Systems" Buildings 16, no. 3: 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030635

APA StyleChu, H.-W., Tsai, H.-C., Chen, Y.-A., & Sun, C.-Y. (2026). Developing a Health-Oriented Assessment Framework for Office Interior Renovation: Addressing Gaps in Green Building Certification Systems. Buildings, 16(3), 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030635