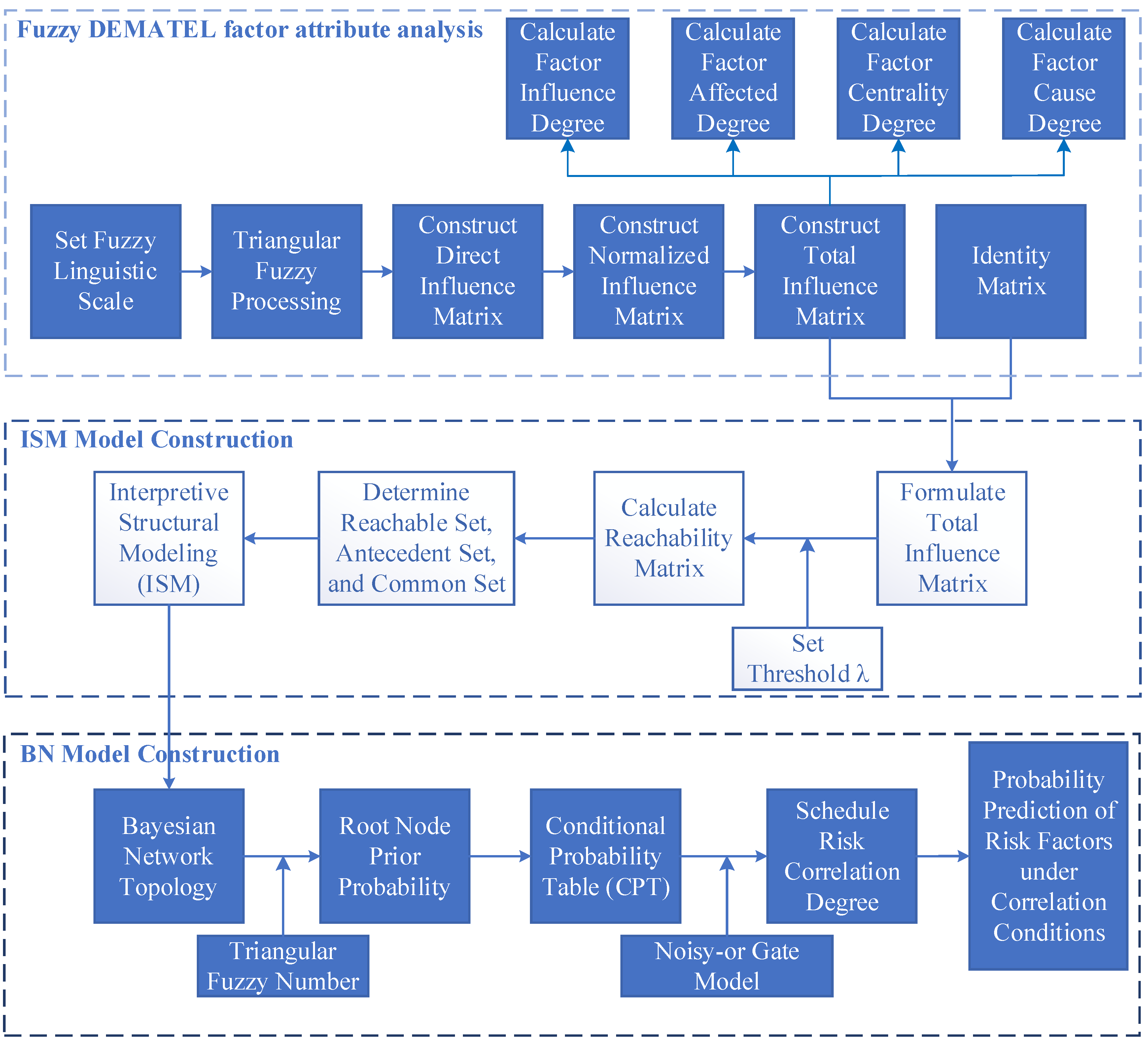

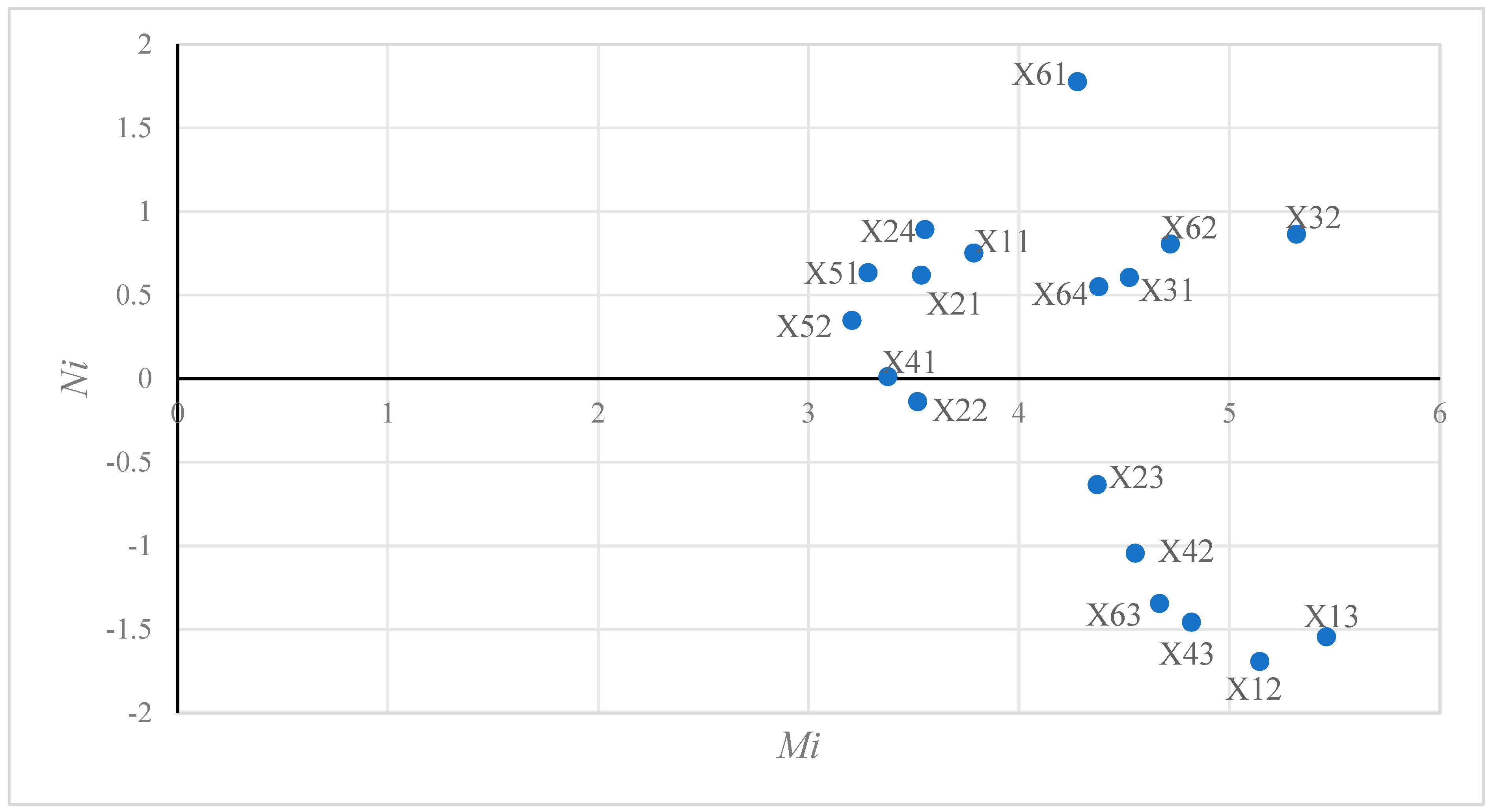

The primary concept of the fuzzy DEMATEL-ISM-BN model is as follows: First, based on the established risk factor system, the fuzzy DEMATEL method is adopted to address the inherent ambiguity in expert judgment. Experts’ assessments of the direct influence relationships among risk factors are quantified using triangular fuzzy numbers, and the Converting Fuzzy data into Crisp Scores (CFCS) defuzzification algorithm is subsequently applied to transform the fuzzy evaluations into a crisp direct influence matrix. Subsequently, the comprehensive influence matrix D is calculated, from which the influence degree (ei), affectedness degree (fi), centrality (Mi), and causality degree (Ni) of each risk factor are derived. This process enables the identification of key risk factors and their causal characteristics within the system.

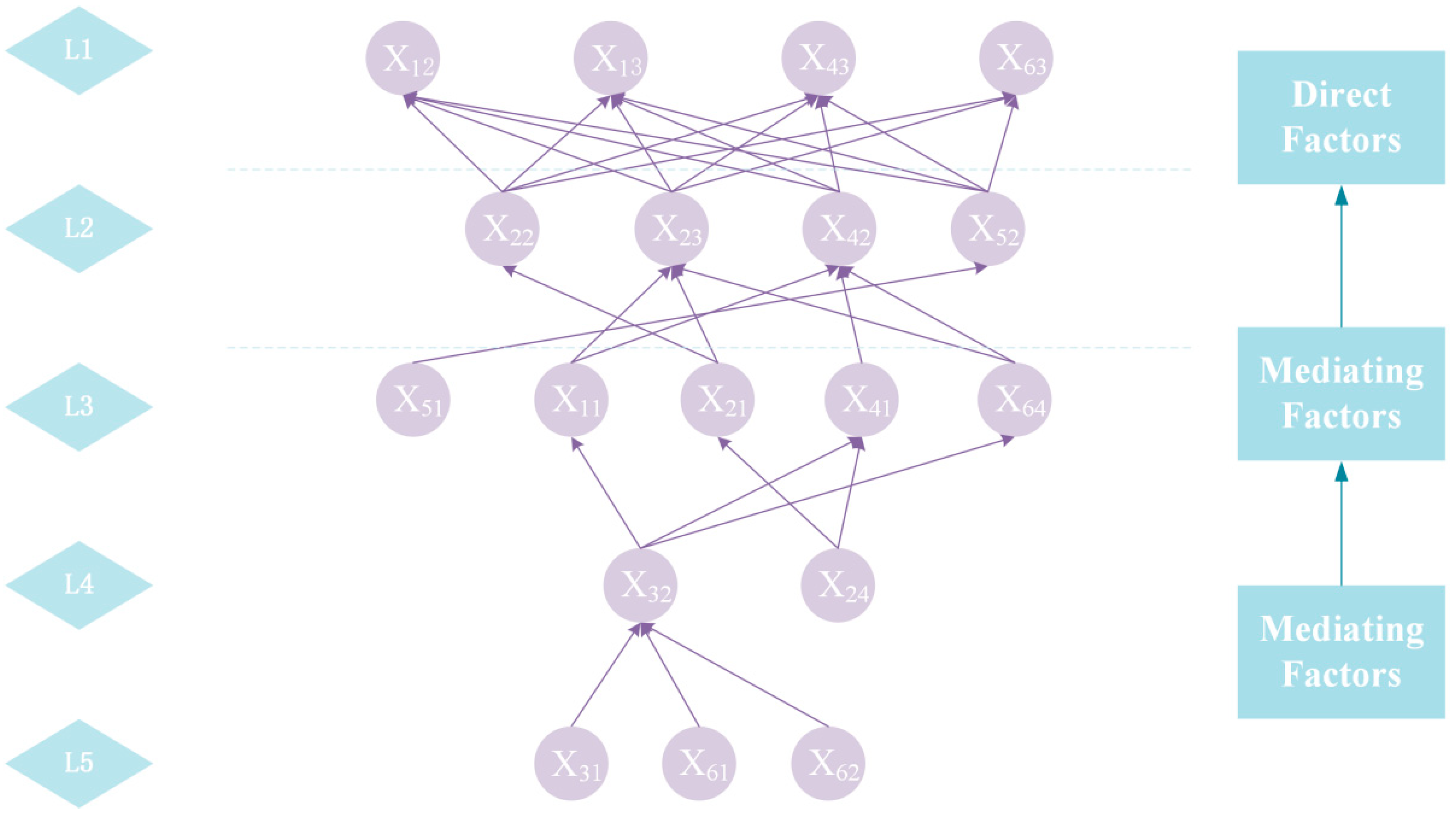

Second, by integrating DEMATEL and ISM, the comprehensive influence matrix is transformed into an accessibility matrix through appropriate threshold setting, thereby capturing the transmission relationships among risk factors. By iteratively analyzing the reachability and antecedent sets, the complex risk system is decomposed into distinct hierarchical levels, ultimately yielding a multi-level hierarchical explanatory structure of schedule risk factors. This structure intuitively reveals the interaction pathways and hierarchical relationships among risks and provides a structural foundation for subsequent Bayesian network construction.

2.3.1. Fuzzy DEMATEL Factor Attribute Analysis

Based on the theory of triangular fuzzy numbers, natural language variables are used to provide fuzzy evaluations for each factor, thereby determining their importance and interrelationships. Building on relevant research [

22], five levels of influence degree were established. As the score increased, the strength of the influence between factors grew, and conversely, it weakened when the score decreased. The influence of each factor on itself was defined as “NO.” The triangular fuzzy numbers corresponding to each level, along with their descriptions, are presented in

Table 3.

A total of n experts are invited to rate the mutual influence of each risk factor at the time of occurrence according to the above five influence degree levels, and then the scoring results are converted into the form of triangular fuzzy numbers in sequence. Let represent the scoring result of the k-th expert on the influence degree of the i-th factor on the j-th factor in the factor set, where . The CFCS method is applied to defuzzify the fuzzy numbers of expert scores. The processing steps are shown in Equations (1)–(7).

(1) To accommodate the structural characteristics of triangular fuzzy numbers, the normalization process is defined as shown in Equations (1)–(3).

(2) As shown in Equations (4)–(6), the normalized triangular fuzzy number is transformed into a left standard value

and a right standard value

, based on which the overall standard value

is calculated.

(3) Defuzzification. Equation (7) illustrates the calculation and conversion of the

k-th expert’s score result on the degree of effect of the

i-th factor on the

j-th factor to the clear value

:

Equation (8) is used to determine the average score of the

i-th factor on the

j-th factor after all experts’ fuzzy scores on the effect of the

i-th factor on the

j-th factor are transformed into unambiguous scoring values, as indicated in Equation (8):

(4) Establishment of a direct influence matrix. According to the influence of horizontal column factors on vertical column factors, Equation (9) illustrates how the direct influence matrix

B is created by filling up the matrix with the previously defuzzified impact values between factors.

(5) Calculation of the normalized influence matrix. The row sum maximum normalization method is used to normalize the matrix

B, and the normalization directly affects the matrix

G, as shown in Equation (10).

(6) Establishment of a comprehensive impact matrix. The direct and indirect influence relationships between all elements are depicted in the comprehensive influence matrix. The comprehensive influence matrix

D can be obtained by continuously multiplying the normalized direct influence matrix

G, as shown in Equation (11).

where the identity matrix is denoted by

I.

(7) Each factor’s impact degree, affectedness degree, centrality, and causality may be computed using the complete influence matrix

D. The total effect of a particular factor on all other risk factors in the system is represented by the influence degree

ei; a larger value indicates a stronger ability of the factor to exert influence on the system. The calculation formula is given as follows:

The affectedness degree

fi. represents the total impact that a given risk factor receives from all other risk factors in the system. A higher value of

fi. indicates that the factor is more susceptible to influences from other factors. The calculation formula is given as follows:

The degree of the center

Mi stands for an individual factor’s total significance inside the complicated system as a whole. It is calculated as the total of its impacted and influence degrees. A higher value of

Mi means that the factor has a bigger influence on the system’s overall changes. The following is the expression for the calculation formula:

The causality degree

Ni reflects the tendency of an individual factor with respect to its influencing role within the system. It is calculated as the difference between the influence degree and the affectedness degree of the factor. A higher value of

Ni suggests that the factor is more likely to act as a catalyst for system change. Factor I is categorized as a cause factor when

Ni > 0; otherwise, it is recognized as an effect factor. The following is the expression for the calculation formula:

The outputs of this section include the centrality and causal attributes of each risk factor, which serve as the basis for defining the risk stratification criteria in the subsequent ISM modeling.

2.3.2. ISM Construction Based on Fuzzy DEMATEL

Although the fuzzy DEMATEL method can quantify the strength of influence and causal attributes among risk factors, its results are primarily presented in matrix form, which makes it difficult to intuitively represent the hierarchical transmission relationships among risks. To further elucidate the hierarchical structure and transmission pathways within the risk system, the ISM method is introduced to structurally reorganize the DEMATEL outputs.

(1) Generate the reachability matrix. Equation (16) addresses a limitation of the fuzzy DEMATEL method—namely, its inability to capture the self-influence of variables—by integrating the comprehensive influence matrix with the identity matrix

I to construct the overall influence matrix

O. Considering that the influence among certain factors may be relatively weak, a threshold value

λ is introduced to optimize matrix

O. Using Equation (17), the elements of the matrix are then converted into binary values (0 or 1), thereby yielding the reachability matrix

K.

(2) Divide factor hierarchy. The reachability set

L(ki) is the set of factors corresponding to the column with a value of 1 in the

i-th row of the reachability matrix

K. The antecedent set

Q(ki) is the set of factors corresponding to the row with a value of 1 in the

i-th column of the reachability matrix

K. First, determine the highest-level factor.

hi is the highest-level factor if there is a factor hi that satisfies Formula (18). Next, simplify the attainable matrix

K by eliminating the rows and columns that correspond to

hi from the matrix. Repeatedly perform the above operations until all factors are hierarchized and the final hierarchical structure is constructed.

(3) The factor correlation structure is constructed using the reachability matrix, in which the rows and columns correspond to individual risk factors and the matrix elements represent the causal relationships among them. When the element in the i-th row and j-th column equals 1, a directed relationship from factor i to factor j is indicated. Based on the results of factor stratification, directed edges are drawn from lower-level factors to higher-level factors.

To enhance the parsimony and interpretability of the model, transitive reduction is applied to eliminate redundant cross-level transmission paths. Specifically, when indirect transmission paths between two risk factors already exist, the corresponding direct links are removed. This procedure highlights the principal structural relationships within the system and facilitates clearer visualization of the associative connections among risk factors.

The hierarchical risk structure obtained in this section not only reveals the transmission pathways of schedule risks but also provides direct structural evidence for defining node dependencies in the Bayesian network, thereby establishing the topological foundation for subsequent Bayesian network construction.

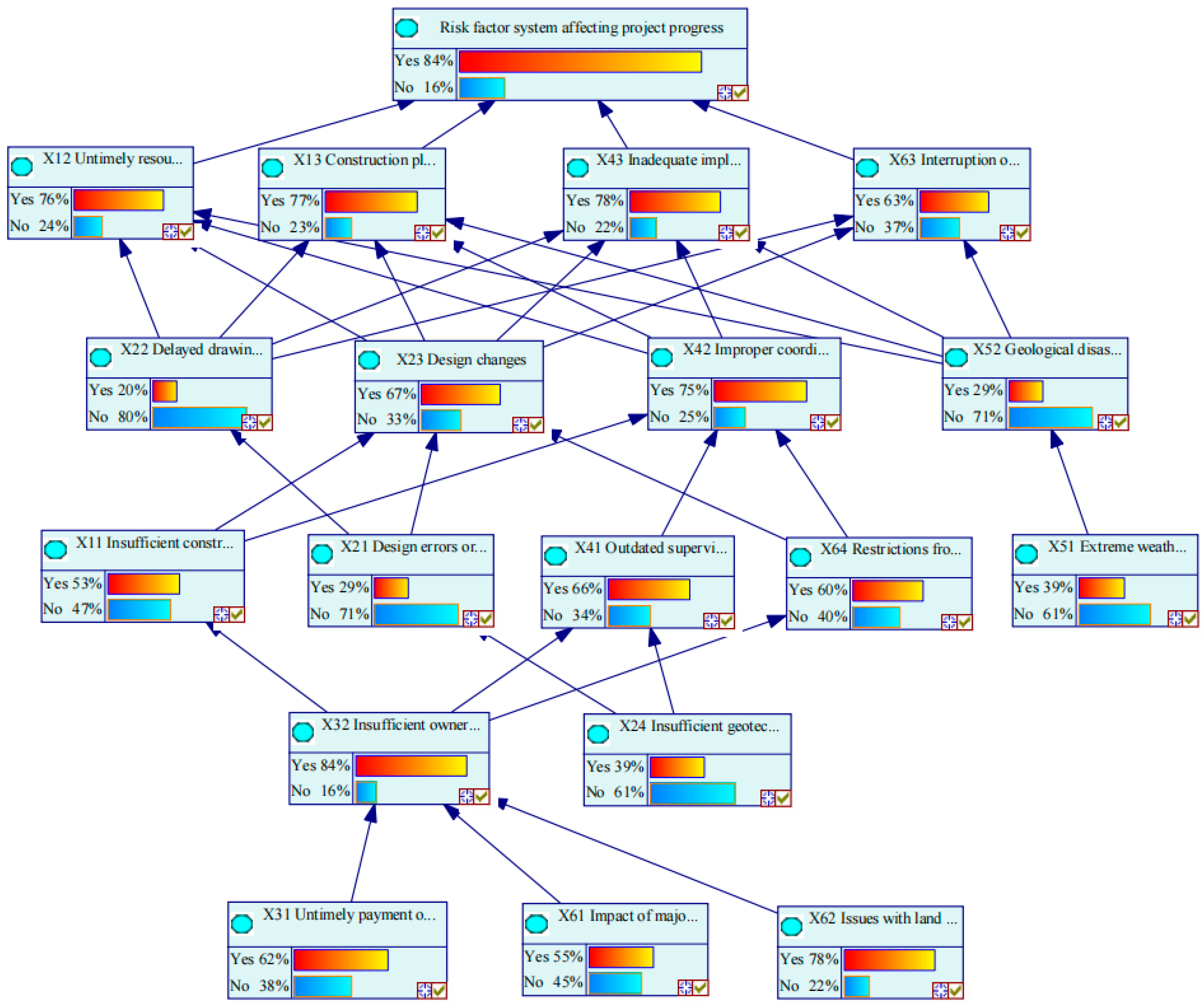

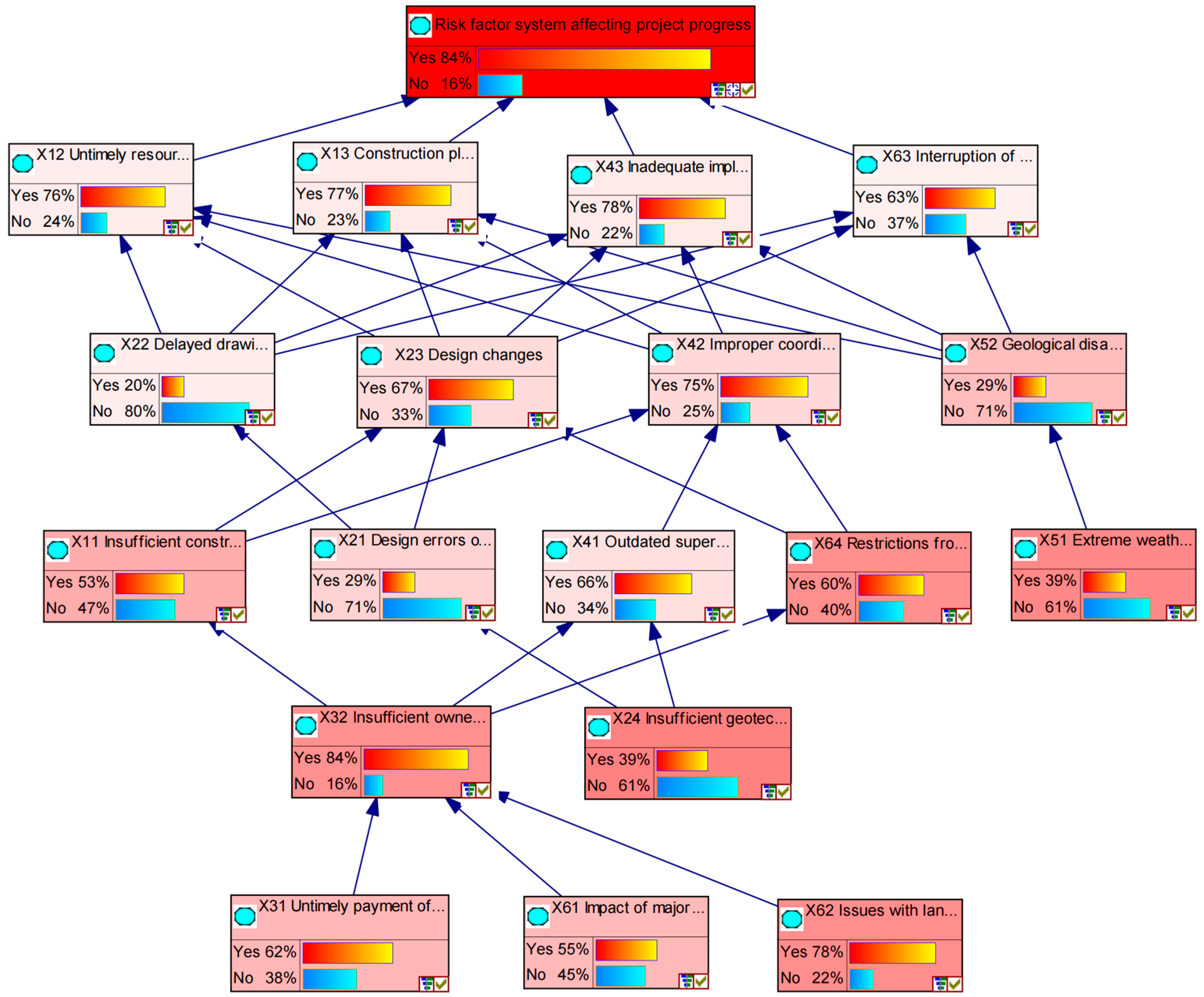

2.3.3. Prediction of Occurrence Probability of Risk Factors Under Risk Correlation Conditions

The fuzzy DEMATEL-ISM model effectively clarifies the connections and hierarchical structures between factors and constructs a correlation framework. However, the analytical results are limited to the structural level and do not quantify the extent of risk correlation under uncertain conditions. Given the inherent uncertainty and probabilistic characteristics of project schedule risks, this study maps the hierarchical structure derived from ISM into a Bayesian network (BN) topology. Triangular fuzzy numbers and the Noisy-OR gate model are employed to estimate the associated probability parameters. By leveraging the inference capability of the BN, the relationships among risk factors are quantified using probabilistic distributions [

23]. This approach enables probabilistic inference of risk interdependencies while preserving the consistency of the underlying causal logic.

(1) Structure mapping

Both the ISM and Bayesian network (BN) models use directed relationships to represent interactions among variables, making their topological structures well suited for integration. In line with the principles of quantifiability, logical rigor, scientific rationality, and systematic completeness, nodes at different hierarchical levels in the ISM are mapped to root, intermediate, and leaf nodes within the BN topology.

(2) Parameter calculation

Once the BN topology is established, the methods used to estimate node parameters directly influence the validity and accuracy of model evaluation. Given the inherent uncertainty and fuzziness of engineering problems, this study adopts a hybrid approach that combines case statistics and expert judgment, integrates fuzzy set theory with the Noisy-OR gate model, and refines the probability estimation process. Consequently, the proposed model enables more scientifically grounded and rational inference and analysis.

(1) Prior probability calculation

Utilizing the concept of triangular fuzzy numbers, in conjunction with expert evaluation results, the grade standard for the root node’s prior probability is defined, with its linguistic value represented by triangular fuzzy numbers. The evaluation levels of “extremely high,” “high,” “medium,” “low,” and “very low” are used to assess the likelihood of each risk factor, with the corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers defined as follows: (0.7, 0.9, 1.0), (0.5, 0.7, 0.9), (0.3, 0.5, 0.7), (0.1, 0.3, 0.5), and (0.0, 0.1, 0.3). Here, is used to represent the k-th expert’s rating result of the probability of occurrence of the i-th factor in the factor set, where . In the same way, the CFCS method of Equations (1)–(7) is used to defuzzify the expert rating fuzzy numbers to obtain the prior probability of each root node.

(2) Determination of conditional probability

The Noisy-OR Gate model can solve the conditional probability of non-root nodes with less workload and optimize the calculation process under the condition of determining the Bayesian network topology and expert scoring. The Noisy-OR model assumes that each parent node can independently affect the state change of the child node. Let

C be a set of parent nodes. The nodes in the set are independent of each other.

Y is the only child node corresponding to the set

C. First, it is necessary to determine the probability of the occurrence of a child node in the state of a single parent node, as shown in Equation (19):

In the formula,

Ci represents the occurrence of node events,

represents the non-occurrence of node events, and

Pi represents the probability that

Y occurs if and only if

Ci occurs. The other terms in the conditional probability table of node

Y can be determined by using Equation (20):

When any parent node occurs, the conditional probability of the child node can be calculated according to Equation (21):

(3) Calculation of correlation degree

In Bayesian networks, the degree of correlation between nodes can be quantified using the Euclidean distance based on conditional probability distribution information [

24]. Specifically, the Euclidean distance is calculated by measuring variations in the posterior probability distributions of child nodes resulting from changes in the state of a parent node, in accordance with the characteristics of the network’s conditional probability structure. The detailed procedure is as follows:

(1) Probability Distribution Extraction: For the target node and its parent, extract the conditional probability distribution of the child nodes in different states of the parent node;

(2) Distance calculation: Calculate the distance value

D* according to the Euclidean formula for the probability distribution vector of the child node before and after the parent node state changes, as shown in Equation (22):

In the formula, pi and qi represent the probabilities of each state of the child node under two different parent node conditions. A larger Euclidean distance D* indicates that changes in the parent node’s state result in greater perturbations of the child node’s probability distribution, reflecting a stronger correlation between the parent and child nodes.

(4) Occurrence probability prediction

Using the forward inference function, the causal paths from parent to child nodes are followed. By inputting the prior probabilities of root nodes and the conditional probabilities of non-root nodes, the posterior probabilities of the risk factors can be calculated using the Bayesian inference formula. Specifically, this yields the probability Pc of each risk factor resulting from causal propagation.

The probability of risk occurrence obtained through Bayesian network inference is used as a key input parameter for calculating the risk impact coefficient in subsequent buffer zone analysis.