Research on Performance Optimization and Vulnerability Assessment of Tension Isolation Bearings for Bridges in Near-Fault Zones: A State-of-the-Art Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Excitations in Near-Fault Earthquakes and Their Impact on Structural Failure

2.1. Pulse Excitation

2.2. High-Amplitude Vertical Earthquake

3. Dynamics and Influences of Separation and Collision Between Main Girder and Pier

3.1. Pier- and Girder-Separation Conditions

3.2. Calculation of Pile Cap–Beam Collision Forces

3.3. Effect of Separation–Collision on Bearing and Pier Damage

4. Research and Technological Advances in the Development of Tensile Bearing

4.1. Material Properties of Seismic Isolation Bearing

4.1.1. Traditional Seismic Isolation Bearing

4.1.2. Application of Novel Materials

4.2. Tensile Bearings

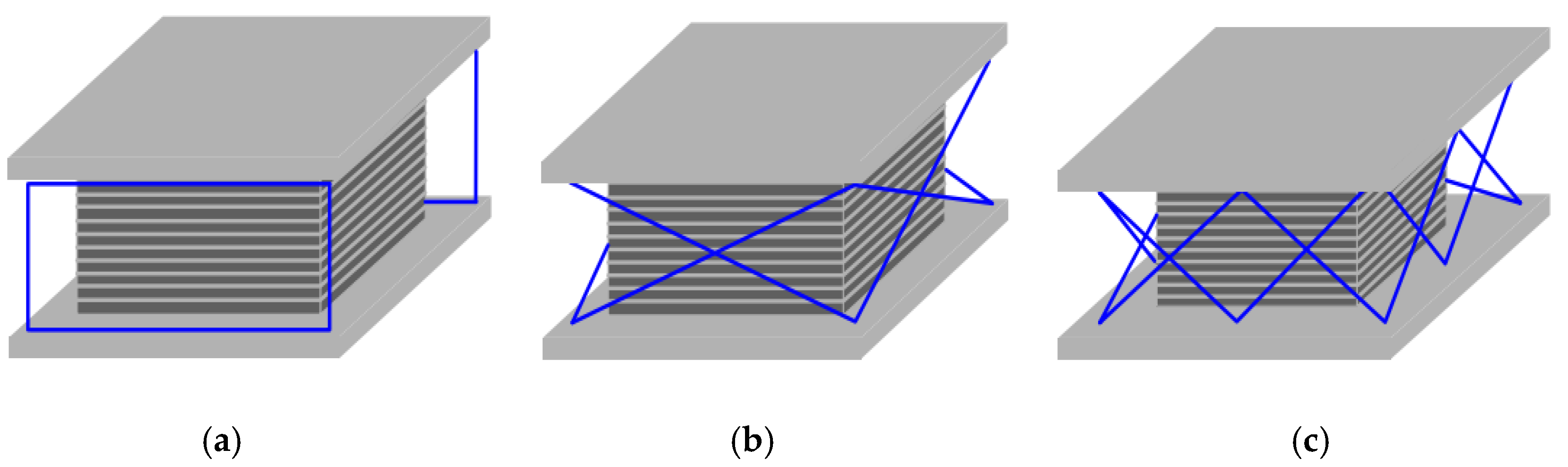

4.2.1. Tensile Laminated Rubber Bearing

4.2.2. Suspension Tensile Bearing

4.2.3. Rail-Type Tensile Bearing

4.2.4. Comparison of Different Tensioning Bearing Technologies

4.3. Design of a Novel Tensile Bearing

4.4. Key Issues and Improvement Directions

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

5.1. Research Summary

5.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bozorgnia, Y.; Eeri, M.; Niazi, M. Characteristics of free-field vertical ground motion during the Northridge earthquale. Earthq. Spectra 1995, 11, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyed, A.M.; Afshin, K. Computing the Effects of Vertical Ground Motion Component on Performance Indices of Bridge Sliding-Rubber Bearings. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2019, 45, 1197–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.-J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W.-Z.; Shen, H.-J.; Li, A.-Q. Parameter Optimization of Lead Rubber Bearings of an Isolated Curved Girder Bridge. Eng. Mech. 2019, 36, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakidis, I.V.; Constantinou, M.C.; Whittaker, A.S. Modeling strength degradation in lead-rubber bearings under earthquake shaking. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 39, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, Y.; Gui, S.; Lu, C. Displacement-based seismic design of SMA cable-restrained sliding lead rubber bearing for isolated continuous girder bridges. Eng. Struct. 2024, 300, 117179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayun, X. Earthquake Resistant Engineering and Retrofitting. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2005, 27, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.-H.; Liu, C. Utilization of FVDs for Seismic Strengthening of Bridge Bearings. Bridge Constr. 2021, 51, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, G.; Angelucci, G.; Mollaioli, F. Near-fault earthquakes with pulse-like horizontal and vertical seismic ground motion components: Analysis and effects on elastomeric bearings. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 160, 107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Simulating the near-field pulse-like ground motions of the Imperial Valley, California, earthquake. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 138, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, A.J.; Elnashai, A.S. Analytical and field evidence of the damaging effect of vertical earthquake ground motion. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1996, 25, 1109–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, J.; Tian, J.; Liu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, W.-W.; Fu, H.; Wang, R. Multi-scale performance of underwater-castable ultra-high-volume fly-ash eco-friendly engineered cementitious composites: Microstructural characterization, workability, mechanical properties and environmental effects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2026, 506, 144870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnashai, A.S.; Papazoglou, A.J. Procedure and spectra for analysis of RC structures subjected to strong vertical earthquake loads. J. Earthq. Eng. 1997, 1, 121–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Han, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Fu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Wu, Z. Bidirectional mapping modeling of pipeline vertical deformation and axial strain based on multi-source monitoring data and machine learning. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2026, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeidis, G.P.; Papageorgiou, A.S. A mathematical representation of near-fault ground motions. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2003, 93, 1099–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Han, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wei, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, X.; Wu, Z. Advanced prediction of pipeline vertical deformation and axial strain via multi-source data fusion and multi-task deep learning. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 14759217251385078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.K. Response of building to near-field pulse-like ground motions. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1999, 28, 1309–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEER. Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Beer, M. Seismic damage analysis due to near-fault multipulse ground motion. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 5099–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Beer, M. Response to discussion of “Seismic damage analysis due to near-fault multipulse ground motion”. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 53, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Peng, Y. Probability density evolution method based stochastic simulation of near-fault pulse-like ground motions. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2024, 76, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Han, Q.; Bi, K.; Zhang, C.; Du, X. Ductility Demand Spectra of the Self-Centering Structure Subjected to Near-Fault Pulse-like Ground Motions. J. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 25, 3142–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgnia, Y.; Niazi, M. Distance scaling of vertical and horizontal response spectra of the Loma Prieta earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1993, 22, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, N.; Chang, S.P. Response of damped oscillators to cycloid pulses. J. Eng. Mech. 2000, 126, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Han, Q.; Bi, K.; Zhang, C.; Du, X. Degradation behavior sand damage model of the interface between ECC and concrete under sulfate wet-dry cycling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 476, 141283. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, B.; Krawinkler, H. Behavior of moment-resisting frame structures subjected to near-fault ground motions. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2004, 33, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Z.; Deng, K.L.; Wang, Y.C.; Yan, G.H.; Zhao, C.H. Field investigation and numerical analysis of damage to a high-pier long-span continuous rigid frame bridge in the 2008 wenchuan earthquake. J. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.W. Quantitative classification of near-fault ground motions using wavelet analysis. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2007, 97, 1486–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.W. Identification of near-fault velocity pulses and prediction of resulting response spectra. In Proceedings of the Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics IV, Sacramento, CA, USA, 18–22 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongxian, L.; Haiping, Z.; Yunbiao, L. Influence of vertical component of ground motion on seismic isolating performance of friction pendulum bearings isolated viaduct. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Dyn. 2018, 38, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eroz, M.; DesRoches, R. Bridge seismic response as a function of the Friction Pendulum System (FPS) modeling assumptions. Eng. Struct. 2008, 30, 3204–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Lueqin, X.; Shuimeng, P. Effect of Vertical Earthquakes on Sliding Performance of Laminated Rubber Bearings. Struct. Eng. 2020, 36, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Warn, G.P.; Whittaker, A.S. Vertical Earthquake Loads on Seismic Isolation Systems in Bridges. J. Struct. Eng. 2008, 134, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, M.R.; Cronin, C.J.; Mayes, R.L. Effect of Vertical Motions on Seismic Response of Highway Bridges. J. Struct. Eng. 2002, 128, 1551–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand-Tabar, S.; Barghian, M. Seismic assessment of a cable-stayed arch bridge under three-component orthotropic earthquake excitation. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2020, 24, 136943322094875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C. Experimental study on seismic responses of a curved bridge considering the effect of pulse and pulse duration. Structures 2023, 58, 105494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xu, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Improved endurance time analysis for seismic responses of concrete dam under near-fault pulse-like ground motions. Eng. Struct. 2022, 270, 114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaohui, L.; Lizhong, J.; Wangbao, Z.; Jian, Y.; Yulin, F.; Zhenbin, R. Influence of velocity pulse effect on earthquake-induced track irregularities of high-speed railway track-bridge system under near-fault ground motions. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.R.B. Optimum Values of Mechanical Properties for Lead Core Rubber Bearing (LCRB) Under Variable Pulse-like Ground Motions. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2023, 23, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, T.; Yadin, S.; Dipendra, G. Seismic fragility analysis of RC bridges in high seismic regions under horizontal and simultaneous horizontal and vertical excitations. Structures 2022, 37, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Tian, J.; Chin, C.-L.; Liu, H.; Yuan, J.; Tang, S.; Mai, R.; Wu, X. Axial compression behavior of GFRP-steel composite tube confined seawater sea-sand concrete intermediate long columns. Eng. Struct. 2025, 333, 120157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Tian, J.; Chen, S.; Chin, C.-L.; Ma, C.-K. Axial compressive performance of CFRP-steel composite tube confined seawater sea-sand concrete intermediate slender columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ouyang, X.; Tian, J.; Zheng, Y.; Fu, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, W.-W.; Zuo, Y. Experimental study on mechanical and self-sensing properties of intelligence-function cement-based composite beams under marine erosion environment. Structures 2025, 76, 108950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y.; Irikura, K.; Uetake, T. Characteristics of observed peak amplitude for strong ground motion from the 1995 Hyogoken Nanbu (Kobe) earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2000, 90, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, M.; Chen, K.; Hwang, R.; Chang, W. Aspects of characteristics of near-fault ground motions of the 1999 Chi-Chi(Taiwan) Earthquake. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2002, 25, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Chin, C.-L.; Ma, C.-K. Nonlinear analysis of axial-compressed corroded circular steel pipes reinforced by FRP-casing grouting. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 201, 107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qi, X.; Ke, J.; Shui, Z. Enhancing the toughness of ultra-high performance concrete through improved fiber-matrix interface bonding. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, L.; Jinggang, L.; Dun, W. Analysis of Statistic Characteristics of Peak Ratios in Vertical and Horizontal Ground Motion Acceleration. J. Seismol. Res. 2010, 33, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Xilin, L. Experimental research on mechanical properties of anti-tension isolation bearing. J. Build. Struct. 2015, 36, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ambraseys, N.N.; Douglas, J. Near-field horizontal and vertical earthquake ground motions. Soli Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2003, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, R.K.; Silva, W.J.; Kenneally, R. New seismic design spectra for nuclear power plants. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 203, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, T. Study on characteristics of vertical ground motion. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2003, 23, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W. Characteristics of Vertical Ground Motions for Applications to Engineering Design; National Center for Earthquake Engineering Research: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Holub, C.J.; Elnashai, A.S. Analytical Assessment of the Effect of Vertical Earthquake Motion on RC Bridge Piers. J. Struct. Eng. 2011, 137, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, N.; Litehiser, J. Attenuation of vertical peak acceleration. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1989, 79, 549–580. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Tao, X. The ratios of vertical to horizontal acceleration response spectra. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2005, 24, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Guo, K.; Wu, Z.; Mai, R.; Chin, C.-L.; Ma, C.-K. Experimental Investigation of a Novel CFRP-Steel Composite Tube-Confined Seawater-Sea Sand Concrete Intermediate Long Column. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2024, 16, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. JTG/T 2231-01—2020; Specifications for Seismic Design of Highway Bridges. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. JTG/T B02-01—2008; Guidelines for Seismic Design of Highway Bridges. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Collier, C.; Elnashai, A. A procedure for combining vertical and horizontal seismic action effects. J. Earthq. Eng. 2001, 5, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; Wen, R.; Lu, D.; Huang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Cu, J. Strong motion observations and recordings from the great Wenchuan Earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2008, 7, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Hong, H.; Chouw, N. Required separation distance between decks and at abutments of a bridge crossing a canyon site to avoid seismic pounding. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 39, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, R.W. Detail of Punching Failure; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989; NISEE-PEER. [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura, S.; Sato, T.; Umeda, T.; Mimura, K.; Yoshikawa, O. A note on dynamic fracture of the bridge bearing due to the great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2002, 27, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Xiaochun, Y. Calculations of Multiple Pounding Forces Between Girder and Pier of Bridges Under Vertical Earthquakes. Eng. Mech. 2010, 27, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, X.; Xiaochun, Y. Transient wave response analysis of a bridge under vertical earthquakes. J. Vib. Shock 2012, 31, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Hao, H.; Bi, K. Theoretical Investigation of Bridge Seismic Responses with Pounding under Near-Fault Vertical Ground Motions. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2015, 11, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yin, X. Transient responses of girder bridges with vertical poundings under near-fault vertical earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2015, 44, 2637–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaddon, S.; Hosseinim, M.; Vasseghi, A. Effect of Non-Uniform Vertical Excitations on Vertical Pounding Phenomenon in Continuous-Deck Curved Box Girder RC Bridges Subjected to Near-Source Earthquakes. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 5360–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, C.; Pu, X.; Guo, W.; Tong, L. Analytical modeling for nonlinear seismic metasurfaces of saturated porous media. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 303, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Yang, Y.; Luo, D. Seismic response analysis of long-span continuous girder bridge considering fluctuating friction of bearing. Structures 2023, 43, 2162–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Song, G. Transient Response of Bridge Piers to Structure Separation under Near-Fault Vertical Earthquake. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Song, G.; Chen, S. Near-Fault Seismic Response Analysis of Bridges Considering Girder Impact and Pier Size. Mathematics 2021, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Zhou, P.; Wang, P.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, H. Analysis of dynamic interaction and response in multispan girder bridges subjected to near-fault earthquakes. Structures 2023, 58, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutong, C.; Kassem, M.M.; Jalilluddin, A.M.; Nazri, F.M.; Wenjun, A. The effect of bridge girder-bearing separation on shear key pounding under vertical earthquake action-A state-of-the-art review. Structures 2023, 55, 2445–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhao, H.; Pan, Z.; Wu, Z.; Chin, C.-L.; Ma, C.-K. Behaviour of corroded circular steel tube strengthened with external FRP tube grouting under eccentric loading:Numerical study. Structures 2023, 56, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Zhou, L.; Fang, T.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q. Collision Analysis of Transverse Stops Considering the Vertical Separation of the Main Beam and Bent Cap. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W. Study on SMA-Sliding Lead Rubber Bearing System for seismic Response Control of Concrete Continuous Bridges. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, C.W.; Stanton, J.F.; Feller, T. Low-temperature performance of elastomeric bearings. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 1990, 4, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakut, A.; Yura, J.A. Evaluation of elastomeric bearing performance at low temperatures. J. Struct. Eng. 2002, 128, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Mander, J.B.; Chen, S.S. Temperature and strain rate effects on the seismic performance of elastomeric and lead-rubber bearings. Spec. Publ. 1996, 164, 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Yakut, A.; Yura, J.A. Parameters influencing performance of elastomeric bearings at low temperatures. J. Struct. Eng. 2002, 128, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Akira, I.; Dang, J.; Hamada, Y.; Himeno, T. A multi-layer thermo-mechanical coupling hysteretic model for high damping rubber bearings at low temperature. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 53, 1028–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, G.; Li, Y.; Zheng, N. Influence of freeze–thaw cycles and aging on the horizontal mechanical properties of high damping rubber bearings. J. Rubber Res. 2022, 25, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhuang, J.S.; Zang, X.Q. Experimental study of mechanical parameters of lead-rubber bearing for nonlinear dynamic analysis. Eng. Mech. 2004, 21, 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, A.; Koo, M.-S.; Do, T.D.; Jeong, J.-H. Effect of lead rubber bearing characteristics on the response of seismic-isolated bridges. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 12, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhong, T.Y.; Gu, Z.W. Study on optimal design of lead-rubber bearings for railway continuous beam bridges. J. China Railw. Soc. 2012, 34, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayati Dezfuli, F.; Alam, M.S. Smart lead rubber bearings equipped with ferrous shape memory alloy wires for seismically isolating highway bridges. J. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 22, 1042–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Hu, S.; Yang, M.; Hu, R.; He, X. Experimental evaluation of the seismic isolation effectiveness of friction pendulum bearings in bridges considering transverse poundings. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 170, 107926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenz, D.M.; Constantinou, M.C. Behaviour of the double concave friction pendulum bearing. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D. 2006, 35, 1403–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Hu, S.; Yang, M.; Hu, R.; He, X. Energy-based prediction of the displacement of DCFP bearings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biao, W.; Tianhan, Y.; Lizhong, J. Effects of friction-based fixed bearings on the seismic vulnerability of a high-speed railway continuous bridge. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2017, 21, 136943321772689. [Google Scholar]

- Jangid, R.S. Stochastic response of bridges seismically isolated by friction pendulum system. J. Bridge Eng. 2008, 13, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graesser, E.J.; Cozzarelli, F.A. Shape-memory alloys as new materials for aseismic isolation. J. Eng. Mech. 1991, 117, 2590–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, M.; Boroschek, R.; Farias, G. Shaking table test of a reduced-scale structure with copper-based SMA energy dissipation devices. In Proceedings of the 8th U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–22 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayati Dezfuli, F.; Alam, M.S. Shape memory alloy wire-based smart natural rubber bearing. Smart Mater. Struct. 2013, 22, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Gur, S.; Roy, K.; Chakraborty, S. Response of bridges isolated by shape memory-alloy rubber bearing. J. Bridge Eng. 2016, 21, 04015071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, D.; Dolce, M.; Ponzo, F.C. The behaviour of SMA isolation systems based on a full-scale release test. J. Earthq. Eng. 2006, 10, 815–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mou, S.; Liu, H. The Performance Contrast Research between SMA Wire and SMA Strands laminate Rubber Bearing. J. Seismol. Res. 2017, 40, 70–74+167. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.-Q.; Alam, M.S. Multi-criteria optimal design and seismic assessment of SMA RC piers and SMA cable restrainers for mitigating seismic damage of simply-supported highway bridges. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; E Ozbulut, O.; Shi, F.; Deng, J. Experimental and numerical investigations on hysteretic response of a multi-level SMA/lead rubber bearing seismic isolation system. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 035024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.-X.; Wang, H.; Li, A.-Q.; Wu, J.-R. Design and experimental verification of a new multi-functional bridge seismic isolation bearing. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2012, 13, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.-X.; Wang, H.; Li, A.-Q.; Wu, J.-R. Explicit finite element analysis and experimental verification of a sliding lead rubber bearing. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2017, 18, 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuru, U.; Takao, N. Study on stiffness, deformation and ulrimate characteristics of base-isolated rubber bearings:horizontalandvertical characteristics under shear deformation. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. 1996, 479, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yang, G.; Zhu, F. Theoretical and experimental researches on nonlinear elastic tension property of rubber isolators. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2004, 24, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, Y.; Xiu-Li, D.; Qiang, H.A. Analysis of Seismic Performance of a Unseating-prevention Laminated Rubber Bearing. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2014, 40, 857–864. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.M.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Chen, S.; Ren, X. Modeling and analyzing of tensile stiffness for seismic isolated rubber bearings. Eng. Mech. 2014, 31, 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Jia-Jia, M.; Yun, C.; Liang, Y. Simulation study on mechanical properties of a new type of three—Dimensional isolation bearing. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2025, 47, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ya, X.; Zhu, Y. Experimental study on high-rise structure with three-dimensional base isolation and overturn resistance devices. J. Build. Struct. 2009, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Ying, Z.; Lu, L. Experimental research on mechanical performance of tension-resistant device for rubber bearings. J. Build. Struct. 2017, 38, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.M.; Marsico, M.R. Tension buckling in rubber bearings affected by cavitation. Eng. Struct. 2013, 56, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, P.; Qu, G. A mechanical tension-resistant device for lead rubber bearings. Eng. Struct. 2017, 152, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, S. Investigation of the seismic response of high-rise buildings supported on tension-resistant elastomeric isolation bearings. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2016, 45, 2207–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Guo, J.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Z.; Dang, X.; Deng, X. Numerical study on seismic performance of a novel multi-level aseismic highway bridge. Eng. Struct. 2023, 275, 115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wang, H.; Fang, S.; Fang, Z.; Wenliuhan, H.; Qu, C.; Zhang, C. Seismic isolation effect and parametric analysis of simply supported beam bridges with multi-level sliding friction adaptive isolation bearing. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 188, 109000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, M.; Kurata, M.; Yamazaki, S.; Kawamata, Y.; Matsuo, S. Test and sensitivity analysis of base-isolated steel frame with low-friction spherical sliding bearings. Earthq. Engng Struct Dyn. 2025, 54, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, B. Study on the Vibration Isolation Performance of Sliding–Rolling Friction Composite Vibration Isolation Bearing. Buildings 2024, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, L.; Wu, J. Finite element analysis method for the sliding cable analysis: The sliding variable method. Structures 2024, 69, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Yuan, W. Experiment Based Seismic Behavior Investigation of a Sliding Controlled Isolation System. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2017, 31, 04016106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Han, Z.; Pang, Y.; Yuan, W. Seismic performance assessment of bridges isolated by a new restorable cable-sliding bearing. Eng. Struct. 2025, 327, 119578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Wang, B. Numerical Model and Seismic Performance of Cable-sliding Friction Aseismic Bearing. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2011, 39, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.-G.; Zhao, Y.-C. Study of Transverse Seismic Performance of Rigid-Frame Bridge Using Cable Sliding Friction Aseismic Bearings. Bridge Constr. 2014, 44, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Hu, J. Seismic Analysis of Cable-stayed Bridges with Cable-sliding Friction Aseismic Bearing. J. Water Resour. Archit. Eng. 2019, 17, 224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-M.; Liu, J.-X.; Zhao, G.-H. Parametric design of unseating prevention devices for highway bridges. J. Vib. Shock 2011, 30, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sarlis, A.A.; Constantinou, M.C. A model of triple friction pendulum bearing for general geometric and frictional parameters. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2016, 45, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Cao, X.; Cheung, P.C.; Wang, B.; Rong, Z. Development and experimental study on cable-sliding friction aseismic bearing. J. Habin Eng. Univ. 2010, 31, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Zhong, T.; Wen, P. Mechanical properties of rail-type anti-tensile rubber bearings. J. Vib. Shock 2018, 37, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Lan, X.; Wu, K.; Yu, W. Tests and Seismic Response Analysis of Guided-Rail-Type Anti-Tensile Rubber Bearing. Buildings 2024, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.S.; Tian, J.; Liu, Y.D.; Liang, S. Experimental study on tension property of V-shaped cable tensile isolation device. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2019, 41, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.-X. Research and Development of the New Seismic Spherical Bearing for Urban Rail Transit. Highway 2018, 4, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

| Event, Station, and Record | Site Condition | Epic.Dist (km) | PGA (g) | PGV (m/s) | PGD (m) | (s) | () | Duration (s) | Intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 EI Centro, ELC#9, H-180 | Medium | 7.0 | 12.99 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 40.00 | 10.64 | 0.26 |

| 1940 EI Centro, ELC#9, H-270 | Medium | 7.0 | 12.99 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 40.00 | 7.46 | 0.13 |

| 1966 Parkfield, Chol.#2, C02065 | Medium | 6.1 | 31.04 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 43.69 | 11.13 | 0.17 |

| 1971 San Fernando, LA-WH, PCD164 | Medium | 6.6 | 11.86 | 0.21 | 1.19 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 28.00 | 4.06 | 0.16 |

| 1978 Tabas, Tabas, TAB-LN | Medium | 7.4 | 55.24 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 32.84 | 8.49 | 0.13 |

| 1978 Tabas, Tabas, TAB-TR | Medium | 7.4 | 55.24 | 0.85 | 1.22 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 32.84 | 8.48 | 0.11 |

| 1979 Imperial Valley, H-AEP045 | Medium | 6.5 | 2.47 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 11.15 | 7.15 | 0.35 |

| 1979 Imperial Valley, H-E06230 | Medium | 6.5 | 27.47 | 0.44 | 1.10 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 39.04 | 3.31 | 0.08 |

| 1981 Westmorland, WSM-090 | Medium | 5.8 | 7.02 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 40.00 | 10.96 | 0.14 |

| 1989 Loma Prieta, LGP000 | Rock | 6.9 | 18.46 | 0.56 | 0.95 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 24.97 | 49.12 | 0.17 |

| 1992 Erzincan, ERZ-NS | Medium | 6.9 | 8.97 | 0.52 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 21.31 | 9.42 | 0.19 |

| 1992 Landers, LCN-275 | Rock | 7.3 | 44.02 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 48.13 | 43.46 | 0.16 |

| 1992 Landers, JOS-090 | Stiff | 7.3 | 13.67 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 44.00 | 13.67 | 0.17 |

| 1992 Cape Mendocino, CPM000 | Rock | 7.1 | 10.36 | 1.50 | 1.27 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 30.00 | 27.19 | 0.16 |

| 1994 Northridge, Rinaldi, RRS228 | Medium | 6.7 | 10.91 | 0.84 | 1.66 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 14.95 | 46.03 | 0.31 |

| 1994 Northridge, Sylmar, SCS052 | Medium | 6.7 | 13.11 | 0.61 | 1.17 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 40.00 | 36.42 | 0.21 |

| 1995 Kobe, Takatori-000 | Soft | 6.9 | 13.12 | 0.61 | 1.27 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 40.96 | 54.31 | 0.17 |

| 1995 Kobe, Takatori-090 | Soft | 6.9 | 13.12 | 0.62 | 1.21 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 40.96 | 7.13 | 0.20 |

| 1995 Kobe, KJM-000 | Stiff | 6.9 | 18.27 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 48.00 | 7.24 | 0.21 |

| 1995 Kobe, KJM-090 | Stiff | 6.9 | 18.27 | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 48.00 | 5.83 | 0.21 |

| 1999 Kocaeli, YPT060 | Medium | 7.4 | 19.30 | 0.27 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 35.00 | 1.36 | 0.06 |

| 1999 Chichi, TCU068-N | Medium | 7.6 | 47.86 | 0.46 | 2.63 | 4.30 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 90.00 | 20.06 | 0.02 |

| 1999 Chichi, TCU068-W | Medium | 7.6 | 47.86 | 0.57 | 1.77 | 3.24 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 90.00 | 20.62 | 0.02 |

| 1999 Chichi, ALS-E | Stiff | 7.6 | 37.83 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 59.00 | 6.00 | 0.12 |

| 1999 Chichi, TCU078W | Medium | 7.6 | 4.96 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 90.00 | 36.15 | 0.07 |

| 1999 Chichi, TCU089W | Stiff | 7.6 | 7.04 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 79.00 | 9.64 | 0.07 |

| 1999 Duze, DZC180 | Medium | 7.1 | 1.61 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 25.89 | 16.83 | 0.09 |

| Type of Support | Research Content | Research Methods | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMA + FPB | The Influence of Mechanical Properties on Shape Memory Alloy Composite Friction Dampers | experimental + numerical simulation | [96,97] |

| SMA + HDRB | Mechanical Properties of SMA Composite High-Damping Rubber Bearings | experimental + numerical simulation | [98,99] |

| SAM + LRB | SMA cables enhance the seismic isolation performance of traditional lead-core rubber bearings | experimental + numerical simulation | [100,101] |

| MFBSIB | Develop a multi-functional seismic isolation and support system and determine its mechanical properties | experimental + numerical simulation | [102] |

| Technical Name | Core Tensile Resistance/Functional Mechanism | Main Advantages | Major Limitations/Shortcomings | Key Performance Parameters | Typical Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional elastomeric bearings (GBZ, LNR, HDR) | Rubber materials exhibit intrinsic shear deformation accompanied by low inherent damping | Low cost, simple construction, and mature technology | Very low tensile strength, prone to aging (service life approximately 15 years), vulnerable in high-intensity zones, and poor cooperative load-bearing capacity. | Compressive elastic modulus (E), shape factor (S), shear modulus (G) | Bridges of small to medium span in non-seismic regions or areas of low seismic intensity/u |

| Tie/Cable Reset Bearing | Provide a restoring force via shear bolts (post-fracture) or frictional sliding combined with steel cables/springs | Provide a reset function to limit excessive displacement and protect the primary structure. | Relatively complex in structural configuration; sensitive to cable parameters (initial gap, stiffness); may increase internal forces at the pier base | Initial free travel of the cable, cable stiffness, friction coefficient | Medium-span continuous girder bridges that require control of residual displacement and prevention of girder collapse. |

| Tension-Reinforcement Device (Rail-Mounted RTD) | Adding independent tensile members to conventional rubber bearings | Significantly improves tensile capacity while having minimal effect on the original bearing’s horizontal shear performance (<4%) | Increased structural complexity and upfront costs; the tensile reinforcement device itself must be reliable | Tensile stiffness, yield force, bilinear model parameters | Tall/high-pier buildings or bridges with large aspect ratios, scenarios in which bearings may be subjected to tensile forces |

| Frictional composite bearing | Lead-core rubber bearings + multi-stage friction dampers, providing additional energy dissipation and uplift resistance/u | High energy dissipation capacity with a full hysteresis loop; capable of reducing tensile stresses in bearings and controlling displacement of the isolation layer. | A large number of design parameters (such as slip force and the number of dampers) necessitate precise and meticulous tuning. | Equivalent damping ratio, sliding force of friction damper | Buildings or bridges for which the displacement of the isolation layer and the tensile stress on bearings are subject to strict control requirements. |

| XY-FP Friction Pendulum Bearing | Curved-surface sliding friction with bidirectionally independent periodicity, theoretically capable of resisting tensile forces | Can effectively reduce near-field seismic displacements and redirect seismic forces; insensitive to variations in the coefficient of friction | High precision is required for curved-surface machining; theoretical research predominates over large-scale engineering applications | Radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, bidirectional periodicity | Irregular, long-span, or potentially tension-generating base-isolated bridges |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Ning, X.; Xia, H.; An, W.; Chin, C.-L.; Ma, C.-K. Research on Performance Optimization and Vulnerability Assessment of Tension Isolation Bearings for Bridges in Near-Fault Zones: A State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings 2026, 16, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030516

Wen Y, Zhou P, Liu Y, Ning X, Xia H, An W, Chin C-L, Ma C-K. Research on Performance Optimization and Vulnerability Assessment of Tension Isolation Bearings for Bridges in Near-Fault Zones: A State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030516

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Yuwen, Ping Zhou, Yang Liu, Xiaojuan Ning, Houzheng Xia, Wenjun An, Chee-Loong Chin, and Chau-Khun Ma. 2026. "Research on Performance Optimization and Vulnerability Assessment of Tension Isolation Bearings for Bridges in Near-Fault Zones: A State-of-the-Art Review" Buildings 16, no. 3: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030516

APA StyleWen, Y., Zhou, P., Liu, Y., Ning, X., Xia, H., An, W., Chin, C.-L., & Ma, C.-K. (2026). Research on Performance Optimization and Vulnerability Assessment of Tension Isolation Bearings for Bridges in Near-Fault Zones: A State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings, 16(3), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030516