Abstract

In the present study, the effects of trans-cinnamaldehyde (TCA) addition on selected properties of lime–cement plaster were investigated. The algicidal effect of TCA on natural biofilm isolated from lime–cement plaster was investigated in the first experiment. Concentrations of 200 mg/L or higher caused complete inhibition of algal growth. Two TCA solutions (0.02% and 1.5% w/w relative to binders) were then used for the preparation of plaster according to the results of biological testing and previous research. The results did not indicate any practically relevant statistically significant effect of TCA on compressive and bending strength, while the total porosity increased with higher aldehyde concentration in the matrix and the matrix and bulk density decreased. Samples with 1.5% TCA showed reduced moisture uptake, indicating improved moisture-related behavior under high-humidity conditions. The occurrence of micropores in the structure compared to the reference was revealed by scanning electron microscopy. The main conclusions of the study are that TCA can be considered for the improvement of algicidal formulations in the form of protective coatings and as an additive influencing the moisture-related behavior of plaster, with beneficial effects observed at a TCA content of 1.5% w/w.

1. Introduction

Essential oils are among the suitable natural substances that represent a possible replacement for synthetic biocides. Essential oils (EOs) have recently attracted considerable attention, mainly due to their biocompatible and relatively harmless origin. Another general benefit of essential oils is their complex biological activity [1]. They are used in cosmetic and medical applications, agriculture, cleaning products, food preservation, and even the restoration and conservation of movable cultural monuments [2,3]. The properties of EOs affect their chemical composition; they are concentrated hydrophobic mixtures of natural organic compounds such as terpenes, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, alcohols, aldehydes, and methoxy compounds [2,3].

One of the most widely used EOs is cinnamon essential oil. It is composed mainly of one substance, namely, trans-cinnamaldehyde (TCA), which constitutes approximately 90% of the EO, depending on the extraction method and the type of cinnamon tree [4,5]. Trans-cinnamaldehyde ((2E)-3-phenylprop-2-enal) is a yellow, viscous liquid with a molecular weight of 132.16 g/mol and a characteristic aroma [6]. Its formula is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Skeletal formula of trans-cinnamaldehyde.

TCA has found practical applications in many industries, including agriculture as a pesticide and healthcare as an antioxidant, antibacterial, and antidiabetic agent [6].

Some authors investigated TCA as a potential biocidal substance for the protection of wood and certain stone religious artefacts [7]. Their results confirmed algicidal and fungicidal effects of TCA on individual model species (Chlorella sp., Chroococcus sp., and Torula sp.). Previous studies have shown that cinnamaldehyde exhibits strong antifungal activities against wide variety of molds and wood-decay fungi [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Spada et al. [18] examined the effectiveness of trans-cinnamaldehyde in various mixtures of essential oils and their coating layers, claiming that their mixtures enhanced the biocidal effects without damaging the stone materials.

Trans-cinnamaldehyde occurs naturally only as a plant metabolite. It degrades to acetaldehyde, benzaldehyde, phenylacetaldehyde, acetophenone, 2-hydroxyphenyl acetone, cinnamaldehyde epoxide, benzoic acid, and cinnamic acid, and therefore its environmental half-life has not been determined. The degradation process can occur via oxidation or enzymatic cleavage, in which the aldehyde group is converted to a carboxyl group [19]. Organic acids are among the main factors leading to the biological corrosion of building materials. Many organic acids are produced and metabolized by bacteria or photosynthetic organisms such as plants or green or blue algae [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Organic acids then dissolve lime and enter into the pores of building materials. The following process is the production of cavities and carbonates [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

To our knowledge, the effects of TCA additions on the chemical, physical, mechanical, and anti-algal properties of bricks, concrete, or plasters have never been investigated. Therefore, the addition of TCA to mixing water for the preparation of lime–cement plaster was investigated in the present study. The mechanical, physical-chemical, structural, and antialgal properties of such prepared lime–cement plaster were identified.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Trans-cinnamaldehyde was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd. (Prague, Czech Republic). Deionized water was used as a solvent to prepare the BB culture medium (CCALA—Czech Academy of Sciences, Třeboň, Czech Republic) for preparation of biological tests.

Two binders were selected for the preparation of the plaster mixture. The primary binder was CL 90-S air lime from the Čertovy schody, Ltd., lime plant (Tmaň, Czech Republic). The secondary binder was CEM I 42.5 R cement from the Mokrá plant of Heidelberg Materials CZ, Ltd. (Mokrá, Czech Republic). To achieve optimal properties, silica sand from Filtrační písky, Ltd., (Chlum, Czech Republic) was selected. The bulk density of the dry aggregate was 1670 kg/m3. Three grain size fractions—PG1 (0–0.5 mm), PG2 (0.5–1 mm), and PG3 (1–2 mm)—were combined in a 1:1:1 ratio to prepare an aggregate with a particle size range of 0–2 mm.

Trans-cinnamaldehyde was added to the dry binders at concentrations of 0.105 g and 7.875 g. The dosages corresponded to 0.02% and 1.5% w/w relative to the total binder mass (lime + cement). Tap water was used as mixing water for preparation of the plaster.

2.2. Biofilm

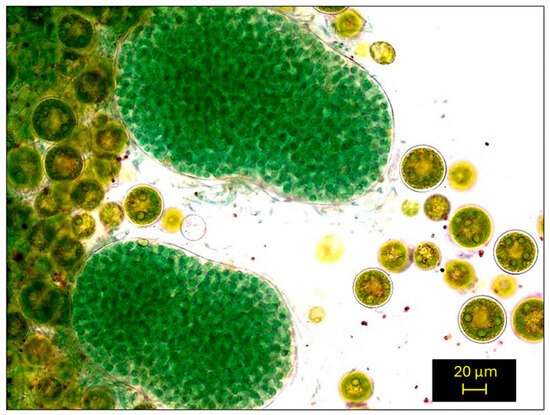

The biofilm was isolated from lime–cement plaster that had been stored in the courtyard of the Faculty of Civil Engineering of the Czech Technical University for several years. The biofilm was isolated by placing several pieces of plaster in a glass container with BB medium, which were left to cultivate at laboratory temperature and lighting for several weeks. The algal biofilm mainly consisted of green and blue algae—Hematococcus pluvialis and Nostoc sp., as suggested by optical microscopy (Figure 2). The bacterial and protozoan composition was not studied, as the study primarily addresses phototrophic organisms.

Figure 2.

Biofilm isolated from lime–cement plaster placed in the courtyard of CTU in Prague. The sample image was captured using an Olympus BX43 light microscope (Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a CMOS camera (Olympus Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification 1000×.

2.3. Bioassay

The bioassay was conducted in 30 mL glass tubes. Three replicates were prepared for the control medium and for each TCA concentration. The experiment was performed at concentrations of 0 mg/L (control), 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L, 200 mg/L, and 250 mg/L. The concentrations were prepared in 100 mL glass volumetric flasks. Appropriate volumes of aldehyde were pipetted into the flasks, followed by the addition of 100 µL of algae culture, and the flasks were filled to the mark with culture solution. The controls contained only algae and culture medium. From each flask, 30 mL of solution was transferred into tubes, which were then covered with transparent parafilm to reduce aldehyde evaporation. The controls and concentrations were incubated under 2000 lux light at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C. Biofilm growth was expressed as absorbance values. These values were measured using a Biochrom Libra S22 spectrophotometer (Biochrom, Ltd., Cambridge, UK) at a wavelength of 750 nm [30]. Absorbances of the controls and concentrations were measured at the start (0 h) and at the end (168 h) of the experiments, and the measured absorbance values were used to calculate algal growth inhibitions.

2.4. Calculations for Evaluating the Biological Data

The absorbance values used in the inhibition calculations were estimated for each tube (controls and tested concentrations) using the following equation:

Afinal = (Atime168h − Atime0h)

The inhibition of absorbances (I) was calculated by Equation (2):

I (%) = ((Acontrol − Aconcentration x)/Acontrol) × 100

Atime168h represents absorbance values measured at 168 h for the controls and tested TCA concentrations, while Atime0h represents absorbance values measure at 0 h for the controls and tested TCA concentrations.

2.5. Preparation of Plaster

The components were dry-mixed using laboratory mixer. Aldehyde was added to the dry mixture using a pipette, and the container holding the weighed aldehyde was rinsed with a portion of the mixing water to transfer the given amount of aldehyde into the mixture. Water was then added to the dry heterogeneous mixture, and the entire mixture was allowed to mix for approximately three minutes.

The finished mixture was placed in pre-prepared 40 × 40 × 160 mm beam molds and 25 × 25 × 25 mm cube molds. The beam molds were filled in two layers, each compacted with 25 rammer punctures and leveled with a metal spatula. The cube molds were compacted by tilting them by 30° and then tapping them on a flat surface, with the top layer similarly leveled using a metal spatula. The compacted samples were then covered with plastic foil to prevent evaporation of the mixing water. After two days, the samples were removed from the molds and stored in a room with constant moisture and temperature (55% RH and 22 °C). All samples were aged for 28 days before being used for the subsequent analysis. The composition of the lime–cement plasters is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of lime–cement samples.

2.6. Basic Physical Properties

The matrix density ρ [kg·m−3] was measured using a Pycnomatic ATC EVO helium pycnometer (Thermo Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic). The bulk density ρv [kg·m−3] was determined using vacuum absorption. Total porosity p [%] was calculated using the bulk density and the matrix density according to Equation (3) [31].

p = (1 − ρv/ρ) · 100%

Pore size distribution was measured using a Pascal 140 + 440 mercury intrusion porosimeter (Thermo Scientific).

2.7. Mechanical Properties

The bending and compressive strengths of samples were determined according to [32] using an FP 100 mechanical press (VEB Industriewerk Ravenstein, Schalkau, Germany). A three-point test was performed on dried samples to determine the bending strength. The compressive strength was measured on the halves of the specimen after the bending test. The strength values were reported as averages. Three replicates were used for measuring the bending strength and six for the compressive strength.

2.8. Determination of Hygroscopic Sorption Properties

To determine the moisture accumulation from the environment, the change in weight at different relative air humidities was measured. The relative humidities were maintained in desiccators using saturated solutions of inorganic salts: MgCl2.6H2O (33%), Mg(NO3)2.6H2O (54%), NaCl (76%), and K2SO4 (99%). Five replicates of each mixture were placed in each desiccator, which were kept in a thermostat at 20 °C. The samples were weighed at the beginning of the experiment and after 14 and 28 days. The mass moisture was calculated according to the following formula:

where m0 is the weight of the dried sample and mtime x is the weight of the sample at time x (14 and 28 days).

µ = (mtime x − m0)/m0

2.9. Microstructure

Microscopic images were obtained using a Phenom XL microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic) and a backscattered electron detector while under high vacuum (1 Pa). Prior to microscopical observations, samples were dried and coated with a thin layer of metal using an SC7620 sputter coater (Quorum). Chemical characterization of the observed phases was performed by energy-dispersive X-ray analysis using a Phenom XL microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism software (Version 3, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric analysis followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test was used for the comparison of basic and moisture-related properties. The algicidal effect was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance was evaluated at a significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Bioassay

The results of the algal test indicated that total inhibition of algal growth was observed at a concentration of 200 mg/L or higher (Table 2). Therefore, this concentration was selected for the preparation of the lime–cement mixture. The second concentration (1.5%) was based on the results of research in Bauerová et al. [33], where the authors indicated suitable moisture properties of the prepared lime plasters.

Table 2.

Absorbance values of the tested concentrations and control at 0 and 168 h. The values crossed out were excluded from the statistics. The data for exclusion of a statistic were selected on the basis of the most outlying values in units of orders of magnitude. The inhibition (I) was calculated according to Formulas No. 1 and 2. The relevant statistical data are given in Supplement File S2.

3.2. Basic Properties

Bulk density was similar because the proposed mixtures were the same for the control and for both matrices containing aldehyde (0.02% and 1.5%). The total porosity increased with higher aldehyde concentration in the matrix, while the matrix density decreased (Table 3). The statistical analysis showed significant differences between the control and 1.5% mixture in terms of matrix density and for both the TCA concentrations in bulk density and total porosity (see Supplement File S2).

Table 3.

Basic physical properties of the studied samples. Primary data are provided in Supplement File S1. The statistical Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric ANOVA) was used for statistical data evaluation at a significance level of 0.05. The appropriate statistical data are shown in Supplement File S2.

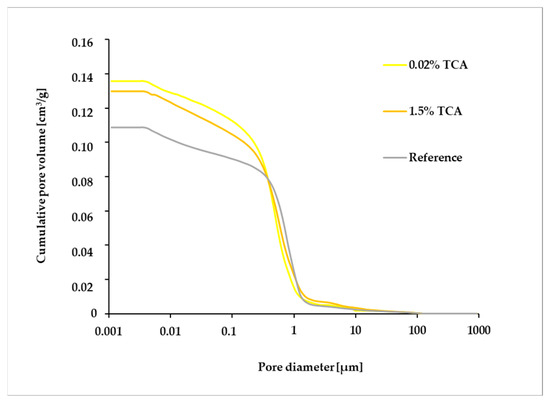

Cumulative pore volume was higher for samples containing TCA than for the reference sample and quite similar for concentrations of 0.02% and 1.5% until approximately 1 µm of pore diameter (Figure 3). All samples contained a considerable number of capillary pores of between 1 and 10 μm. The volume of the larger pores (>10 μm) was reduced generally, but the volume of the smaller ones (<1 μm) gradually increased.

Figure 3.

Pore size distribution cumulative curve of the studied plasters (reference, plaster containing 0.02% TCA, and plaster containing 1.5% TCA).

3.3. Mechanical Properties

The mean bending strength was slightly lower for the higher concentration (1.5% TCA) compared to the reference, but the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Supplement File S2). Compressive strength decreased in both aldehyde concentrations (Figure 4), and a statistically significant difference was found for the 0.02% level of TCA (Figure 4 and Supplement File S2).

Figure 4.

Bending strength (solid colors) and compressive strength (striped colors) of the samples after 28 days. Mean values and their standard deviations are in the figure, primary data are provided in Supplement File S1, and the relevant statistical analysis is provided in Supplement File S2. 2 stars mean that the result is statistically significant at the 1% level in comparison to control.

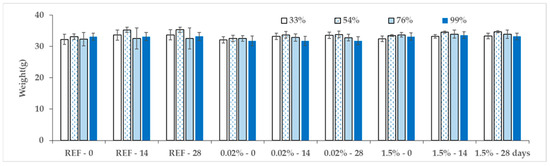

3.4. Hygroscopic Sorption Parameter

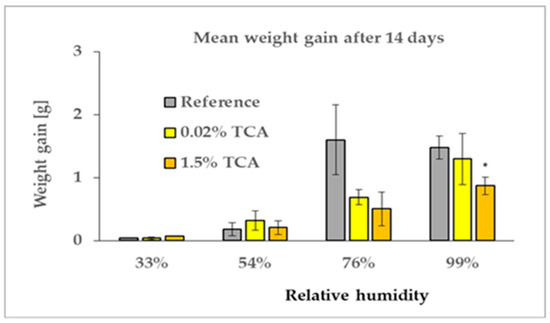

Figure 5 shows the mean weights of samples exposed to various humidities, demonstrating very consistent data; statistical analysis did not confirm significant variation (Supplement File S2). Figure 6 represents weight gains after 14 days of exposure, and Figure 7 after 28 days. The data indicate that at humidities of 33% and 56% (indoor environment), there were no differences between the reference and samples with either the lower or higher TCA concentration during both time periods. At 76% moisture (outdoor environment) a relatively clear difference was observed between the reference and the TCA-containing samples, which were less saturated than the reference. Additionally, at 99% moisture (simulating rain), a clear difference was also observed between samples with lower and higher TCA concentrations. Samples with 0.02% TCA did not differ from the reference, whereas samples with 1.5% TCA were less affected by moisture. However, these trends were mostly not statistically significant due to high data variability (see Supplement File S2).

Figure 5.

Sample mean weights with their standard deviations at 0, 14, and 28 days of exposure to humidities of 33%, 54%, 76%, and 99%. Primary data are provided in Supplement File S1.

Figure 6.

Weight gain of samples after 14 days of exposure to relative humidities of 33%, 54%, 76%, and 99%. One star mean that the result is statistically significant at the 5% level.

Figure 7.

Weight gain of samples after 28 days of exposure to relative humidities of 33%, 54%, 76%, and 99%.

3.5. Microstructure

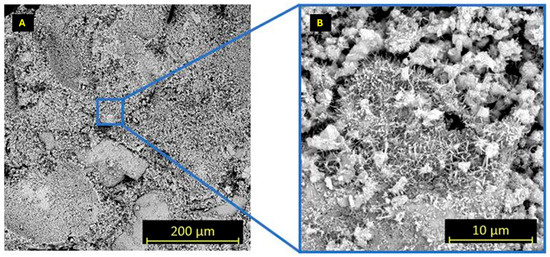

SEM imaging was conducted to assess the influence of TCA addition on the microstructural arrangement of the lime–cement plaster and to identify potential voids or morphological changes associated with different TCA concentrations.

The reference plaster exhibited a compact matrix with only minor shrinkage-related cracks (Figure 8). The sample with 0.02% TCA showed a microstructure comparable to the reference, without identifiable rounded voids associated with TCA droplets (Figure 9). Locally, the matrix appears slightly less cohesive and less uniformly interlinked, which may be attributed to the presence of a small amount of organic additive. In contrast, the plaster containing 1.5% TCA (Figure 10) displayed distinct spherical pores that may be associated with incomplete miscibility of TCA with water during mixing, consistent with the porosimetrical results indicating increased pore volume at higher aldehyde concentrations.

Figure 8.

SEM microstructure of the reference plaster ((A): 500× and (B): 9000×).

Figure 9.

SEM microstructure of the plaster containing 0.02% TCA ((A): 500× and (B): 9000×).

Figure 10.

SEM microstructure of the plaster containing 1.5% TCA, showing rounded voids formed by TCA droplets ((A): 500× and (B): 9000×). Green arrows indicate the circular pores.

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Effects

The antifungal or antimicrobial effects of TCA have been confirmed in many previous studies on building materials [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The results of the present study (Table 2) indicate that TCA has potential as a component of general biocide preparations for the protection of building materials. Its algicidal effect correlated with the effective concentrations at ug–mg levels, similar to what has been observed for other essential oils or substances studied previously [34,35,36,37]. Spada et al. [18] studied the effectiveness of cinnamaldehyde in combinations of mixtures of essential oils and carriers, claiming that their mixtures enhanced biocidal activity without damaging the stone substrate, enabling the use of low concentrations. However, the authors did not study the effect of TCA as a single substance. Therefore, we are not able compare our results with the conclusions of their study. Other papers focused on the effectiveness of TCA against algae have not yet been published. In the present study, concentrations of up to 0.025% were tested with algae, and the lowest 100% effective concentration (0.02%) was selected for the ensuing experiments. The highest concentration 1.5% was selected based on the study by Bauerová et al. [33] and their findings on the moisture behavior of lime plasters containing linseed oil. Theoretically, 100% inhibition of growth can be expected at the 1.5% concentration. The present study observed the algicidal effect of TCA in an aqueous solution, which does not fully correspond to the possibilities of the effect in the building material itself, where the effectiveness of TCA is influenced by many factors such as bioavailability to living organisms, the influence of the surrounding environment, and the sensitivity of algae in combination with other organisms in a natural biofilm.

TCA’s effects against lime–cement plaster biofilm were studied under laboratory conditions and through in situ experimentation. One author described some effects on algal biomass, comparing references and samples with TCA concentrations during in situ and laboratory experiments [38]. However, very fresh lime–cement samples were used in the experiments, and algae were not able to live in successful quantities for drawing conclusions on such samples thanks to their high alkalinity. In the future, some experiments with artificially or naturally aged samples should be performed for better verification of the antialgal potential of TCA.

In every case, TCA has the advantage of a mild and pleasant aroma during manual handling in the laboratory or when applied in plaster materials and during evaporation. Unlike substances such as thyme, which can produce a strong and irritating smell for sensitive individuals (own experience, unpublished), TCA is more tolerable, making its practical use feasible. TCA was intensely smelled from the higher-concentration samples both after 28 days, when most analyses began, as well as during the 12-month period after their production. There is a question of TCA’s fate in the samples—the incorporated TCA in the solid plaster could leach out or evaporate at sufficient concentrations to prevent surface biofilm growth over time. The protection of food, clothing, and other goods from pests is based on this principle of aromatic essential oils, which evaporate into the air in warehouses [39,40]. The permanent aroma of TCA from the produced samples during the time of the study leads to a suspicion that the substance is gradually moving from the samples into the air. However, quantifiably verifying the effectiveness of evaporating substances against the growth of organisms is very difficult in an open space; essentially, there are only qualitative tests with yes/no conclusions performed on closed agar plates with fungi, e.g., [41,42], and these studies qualitatively confirmed an effect of volatile substances against pests. Some authors tried to encapsulate TCA in a carrier or sealer to prolong its presence, as has been seen in some other studies involving essential oils [43]. This addition would enhance the practical relevance of the work for real-world applications.

4.2. Non-Biological Effects

For the lower concentration of 0.02% TCA, the changes in mechanical properties were minor, although a statistically significant decrease in compressive strength was observed. The higher concentration (1.5%) resulted in a slight decrease in bending strength as well as compressive strength (Figure 4). The results were also confirmed by statistical analysis (Supplement File S2). Similar results were reported by Bauerová et al. [33], where 1% or 1.5% linseed oil caused a reduction in compressive strength of approximately 2 MPa.

More interesting findings were revealed by other analyses. The pore size distribution cumulative curve (Figure 3) indicates a higher number of pores in the 0.1–1 µm range, with samples containing TCA showing more pores compared to the reference sample. A similar trend was observed for the 0.001–0.1 µm pore category. The pore size distribution correlated with total porosity (p increased with higher TCA concentration in the sample) and with bulk and matrix densities (both densities decreased with higher TCA concentration in the sample) (Table 2). These results are also supported by SEM analysis, which revealed pores primarily in samples containing 1.5% TCA (Figure 10). The pores were probably filled by TCA; this substance made them water-resistant, and the intensity of the hydrophobic behavior correlated with the amount of TCA in the pores. The reference and 0.02% TCA samples showed comparable microstructures. In a separate study by Fišer [38], much higher TCA dosages (10% and 20%) were tested: the 10% TCA mortar was highly porous and poorly compacted, and the 20% TCA sample was completely destroyed, preventing further analysis.

Such results indicate that TCA can be added into plaster, but at rather low levels (in the order of a few percent). Another question concerns the degradability of TCA into cinnamic acid [19] and the potential effect of this process on pore formation in lime–cement plaster. However, the applied analytical methods do not allow for the direct identification of TCA or its degradation products within the pore structure of the matrix.

Similar research by Nunes et al. [44] using metakaolin and linseed oil observed cavities in samples containing oil, with increased porosity and reduced sample integrity. Pahlavan et al. [45] described that food oils in lime mortars negatively affected mortar integrity and extended the time required for solidification. They also observed larger crystals in the microstructure, resulting in lower compressive strength. The formation of holes containing TCA also corresponds to the observed moisture of the tested samples (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

At higher TCA contents, the addition of aldehyde was associated with a reduction in hygroscopic behavior compared to the reference, resulting in lower equilibrium moisture uptake (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). It can be assumed that the addition of TCA influences the pore structure and connectivity, which may reduce moisture uptake. Those micropores might be partially closed or lined with organic residues, such that water cannot easily enter them. According to available studies, the addition of food-derived or essential oils at concentrations exceeding approximately 2% may adversely affect the microstructure building materials, leading to deterioration of their mechanical, moisture-related, and structural properties [38].

5. Conclusions

In this study, the addition of trans-cinnamaldehyde (TCA) was tested for the first time with respect to its influence on selected properties of lime–cement plaster. The results demonstrated that natural algal biofilm isolated from lime–cement plaster did not survive at concentrations of 200 mg/L or higher in the aquatic test. The addition of 0.02% TCA (corresponding to the inhibitor concentration determined in the biological test) to the binder of the prepared lime–cement plaster had only a minor effect on its properties. The addition of TCA caused changes in the microstructure compared to the reference sample, producing more pores in the under 1 µm range, which was associated with changes in moisture-related behavior of the plasters. However, the addition of amounts of TCA above 1.5% seems inappropriate because it can lead to the formation of a large number of pores, which may result in a reduction in mechanical properties and potential deterioration of the material structure. In the future, TCA should be investigated primarily as a biocidal or moisture-modifying additive in coating systems rather than bulk plaster formulations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings16020443/s1, File S1: Primary data; File S2: Statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and M.J.; methodology, K.K., M.J. and A.F.; validation, K.K., M.B. and M.J.; formal analysis, K.K.; investigation, K.K., A.F., M.B., J.V., M.J. and V.P.; resources, K.K.; data curation, K.K. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, K.K.; visualization, K.K.; supervision, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Czech Science Foundation, Project No. 24-10395S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article or in the Supplementary Materials. Some of the primary data and following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://dspace.cvut.cz/handle/10467/124441.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Korbelář, J.; Endris, Z. Naše Rostliny v Lékařství, 1st ed.; Avicenum: Prague, Czech Republic, 1981; p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- Tanasă, F.; Nechifor, M.; Teacă, C.-A. Essential Oils as Alternative Green Broad-Spectrum Biocides. Plants 2024, 13, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserand, R.; Young, R. Essential oil composition. In Essential Oil Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Long, F.; Lin, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, G.; Wang, T. Regulatory roles of phytochemicals on circular RNAs in cancer and other chronic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 174, 105936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.L.; Li, G.H.; Li, X.R.; Wu, X.Y.; Ren, D.M.; Lou, H.X.; Wang, X.N.; Shen, T. Lignan and flavonoid support the prevention of cinnamon against oxidative stress related diseases. Phytomedicine 2019, 53, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, C. Cinnamaldehyde in diabetes: A review of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and safety. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 122, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axinte, L.; Cuzman, O.A.; Feci, E.; Palanti, S.; Tiano, P. Cinnamaldehyde, a potential active agent for the conservation of wood and stone religious artefacts. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2011, 7, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Firmino, D.F.; Cavalcante, T.T.A.; Gomes, G.A.; Firmino, N.C.S.; Rosa, L.D.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Catunda, F.E.A. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of Cinnamomum Sp. essential oil and cinnamaldehyde: Antimicrobial activities. Sci. World J. 2018, 2018, 7405736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakakhel, M.A.; Wu, F.; Gu, J.D.; Feng, H.; Shah, K.; Wang, W. Controlling biodeterioration of cultural heritage objects with biocides: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 143, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Toro, R.; Jiménez, A.; Talens, P.; Chiralt, A. Effect of the incorporation of surfactants on the physical properties of corn starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Liu, Y.J.; Xiang, X.W.; Wu, R.M. Microcapsulation of Cinnamon Essential Oil and Its Application in Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables. Packag. Eng. 2016, 37, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Dhifi, W.; Bellili, S.; Jazi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Mnif, W. Essential oils’ chemical characterization and investigation of some biological activities: A critical review. Medicines 2016, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, P.F.; Chang, S.T. Antifungal activities of essential oils and their constituents from indigenous cinnamon (Cinnamomum osmophloeum) leaves against wood decay fungi. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittenden, C.; Singh, T. Antifungal activity of essential oils against wood degrading fungi and their applications as wood preservatives. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2011, 2, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusant, N.; Thévenon, M.-F.; Leménager, N.; Wozniak, E. Potential of antifungal and antitermitic activity of several essential oils. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the International Research Group on Wood Protection, Beijing, China, 24–28 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.A.; Malik, A.; Ahmad, I. Anti-candidal activity of essential oils alone and in combination with amphotericin B or f luconazole against multi-drug resistant isolates of Candida albicans. Med. Mycol. 2012, 50, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.S.; Liu, J.Y.; Chang, E.H.; Chang, S.T. Antifungal activity of cinnamaldehyde and eugenol congeners against wood-rot fungi. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5145–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, M.; Cuzman, O.A.; Tosini, I.; Galeotti, M.; Sorella, F. Essential oils mixtures as an eco-friendly biocidal solution for a marble statue restoration. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 163, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, Y.L.; Liang, M.; Dai, S.Y.; Ma, L.; Li, W.G.; Lai, F.; Liu, X.M. Characteristics and hazards of the cinnamaldehyde oxidation process. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19124–19133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, N.A.; Viles, H.A.; Ahmad, S.; McCabe, S.; Smith, B.J. Algal ‘greening’ and the conservation of stone heritage structures. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Parrow, M.W.; Sangdeh, P.K. Microalgae-integrated building enclosures: A nature-based solution for carbon sequestration. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1574582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariño, X.; Gomez-Bolea, A.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Lichens on ancient mortars. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1997, 40, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C. Influence of environment on microbial colonization of historic stone buildings with emphasis on cyanobacteria. Heritage 2020, 3, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylarde, C.C.; Morton, L.H.G. Deteriogenic biofilms on buildings and their control: A review. Biofouling 1999, 14, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiz, L.; Piñar, G.; Lubitz, W.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Monitoring the colonization of monuments by bacteria: Cultivation versus molecular methods. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.J.; Siebert, J.; Hirsch, P. Biomass and organic acids in sandstone of a weathering building: Production by bacterial and fungal isolates. Microbial. Ecol. 1991, 21, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, A.; Sarethy, I.P. Microbial biodeterioration of cultural heritage: Events, colonization, and analyses. Microb. Ecol. 2019, 78, 1014–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo Jimenez, B.A.; Awwad, F.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Cinnamaldehyde in Focus: Antimicrobial Properties, Biosynthetic Pathway, and Industrial Applications. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreaz, S.; Wani, W.A.; Behbehani, J.M.; Raja, V.; Irshad, M.D.; Karched, M.; Ali, I.; Siddiqi, W.A.; Hun, L.T. Cinnamaldehyde and its derivatives, a novel class of antifungal agents. Fitoterapia 2016, 112, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ČSN EN ISO 8692 (757740); Kvalita Vod—Zkouška Inhibice Růstu Sladkovodních Zelených Řas. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012.

- Stavební Hmoty. Available online: https://k123.fsv.cvut.cz/media/subjects/files/123SH01/kniha-stavebni-hmoty.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ČSN 1015-11 (2020); Zkušební Metody Malt Pro Zdivo—Část 11: Stanovení Pevnosti Zatvrdlých Malt v Tahu za Ohybu a v Tlaku. ÚNMZ: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020.

- Bauerová, P.; Reiterman, P.; Davidová, V.; Vejmelková, E.; Kracík-Štorkánová, M.; Keppert, M. Lime mortars with linseed oil: Engineering properties and durability. Rev. Romana Mater. 2021, 51, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rotolo, V.; De Caro, M.L.; Giordano, A.; Palla, F. Solunto archaeological park in Sicily: Life under mosaic tesserae. Flora Medit. 2018, 28, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano Candela, R.; Maggi, F.; Lazzara, G.; Rosselli, S.; Bruno, M. The essential oil of Thymbra capitata and its application as a biocide on stone and derived surfaces. Plants 2019, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchia, A.; Aureli, H.; Prestileo, F.; Ortenzi, F.; Sellathurai, S.; Docci, A.; Cerafogli, E.; Colasanti, I.A.; Ricca, M.; La Russa, M.F. In-Situ Comparative Study of Eucalyptus, Basil, Cloves, Thyme, Pine Tree, and Tea Tree Essential Oil Biocide Efficacy. Methods Protoc. 2022, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfendler, S.; Borderie, F.; Bousta, F.; Alaoui-Sosse, L.; Alaoui-Sosse, B.; Aleya, L. Comparison of biocides, allelopathic substances and UV-Cas treatments for biofilm proliferation on heritage monuments. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fišer, A. Effect of Cinnamaldehyde on Selected Properties of Lime-Cement Plaster. Bachelor’s Thesis, Czech Technical University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vidyarthi, A.K.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Biswas, A.K.; Talukdar, S.; Agrawal, R.K.; Chand, S. Impact of Essential Cinnamon Oils on the Qualitative Attributes of Chicken Eggs at Different Storage Temperatures. Int. J. Basic Sci. Med. 2025, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binduheva, U.; Negi, P. Efficacy of cinnamon oil to prolong the shelf-life of pasteurized, acidified, and ambient stored papaya pulp. Acta Aliment. 2014, 43, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobetičová, K.; Vrzáň, J.; Vidholdová, Z.; Fraňková, A. Comparison of three methodologies for evaluating the antifungal activity of cinnamaldehyde. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2911, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klouček, P.; Šmid, J.; Fraňková, A.; Kokoška, L.; Valterová, I.; Pavela, R. Fast screening method for assessment of antimicrobial activity of essential oils in vapor phase. Food Res. Int. 2012, 47, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, F.; Puente-Diaz, L.; Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Char, C. Encapsulation of Cinnamaldehyde and Vanillin as a Strategy to Increase Their Antimicrobial Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Slížková, Z.; Křivánková, D. Lime-based mortars with linseed oil: Sodium chloride resistance assessment and characterization of the degraded material. Period Miner. 2013, 82, 411–427. [Google Scholar]

- Pahlavan, P.; Manzi, S.; Rodrigues-Estrada, M.T.; Bignozzi, M.C. Valorization of spent cooking oils in hydrophobic waste-base lime mortars for restorative rendering applications. Constr. Build. Mat. 2017, 146, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.