The Politics of Green Buildings: Neoliberal Environmental Governance and LEED’s Uneven Geography in Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. On Green Building, Green Certification and Criticisms

2.1. A Brief Introduction to Green Building and Certification

2.2. Criticisms

3. Case Study Context

3.1. Data and Methodology

3.1.1. Data Sources

3.1.2. Data Processing and Classification

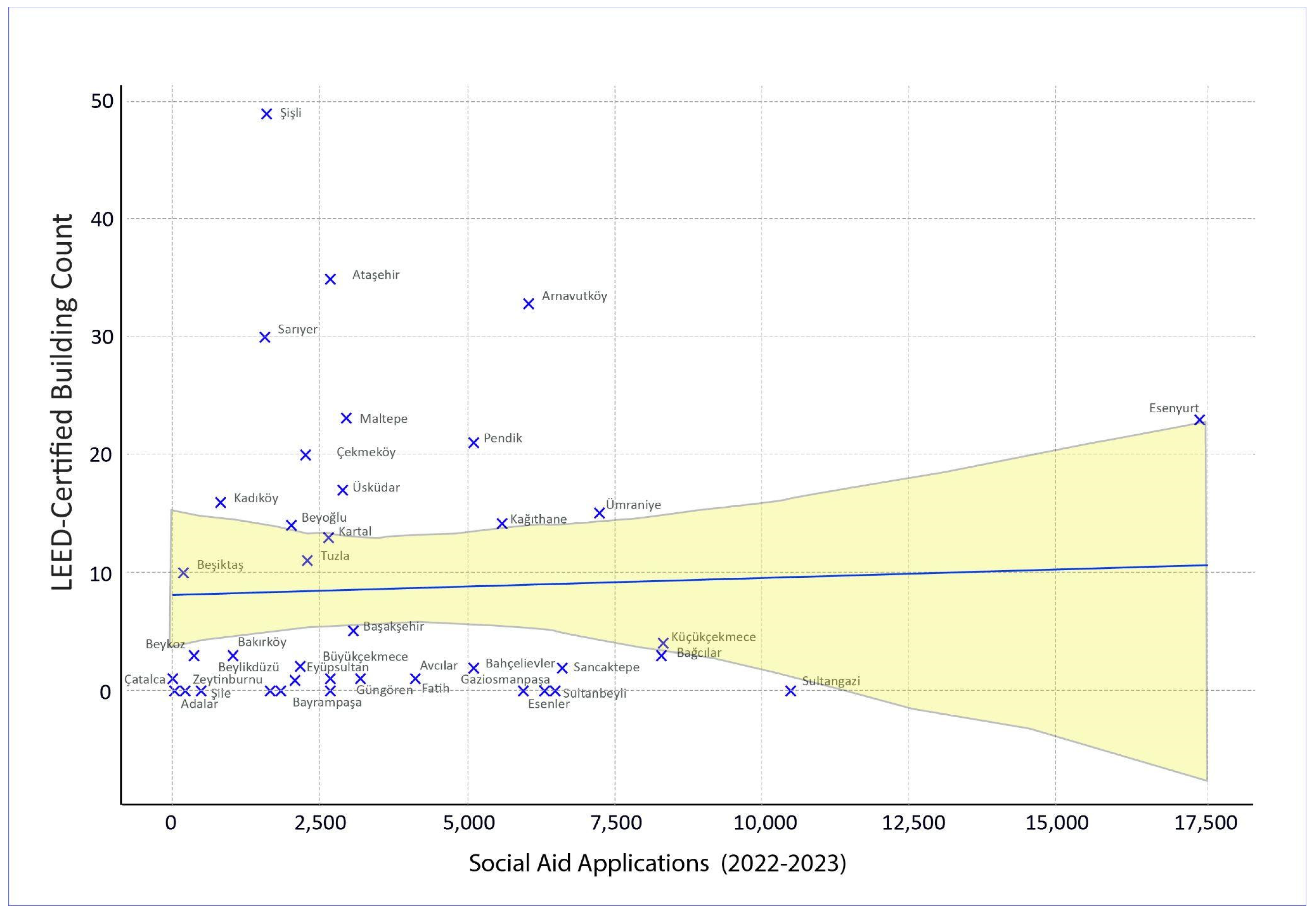

3.1.3. Exploratory Correlation Analysis: Green Building Density and Socio-Economic Vulnerability

3.1.4. Analytical Strategy

3.1.5. Methodological Scope and Limitations

4. Findings

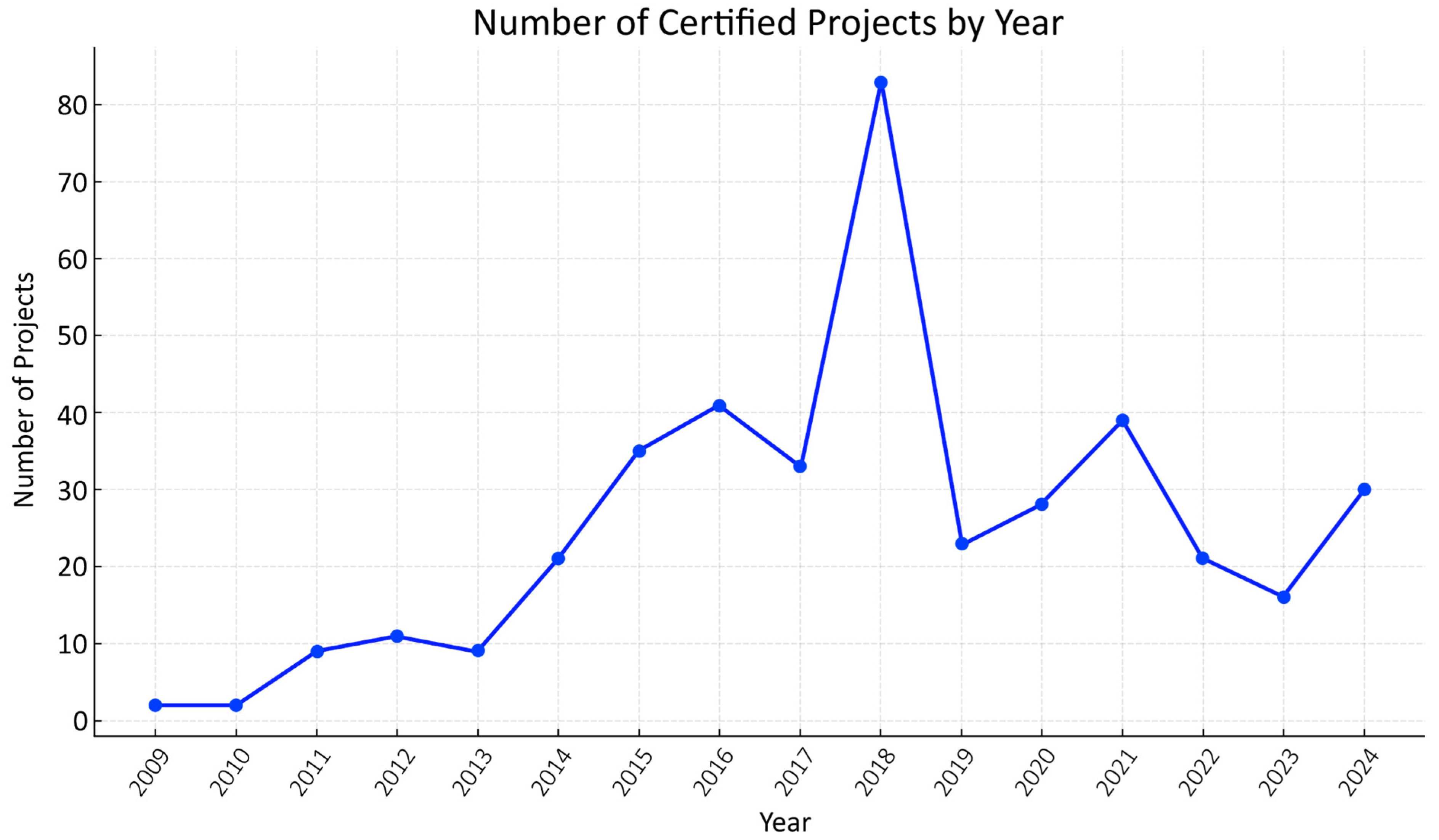

4.1. A Timeline of LEED Certification in Istanbul (2009–2024)

4.2. LEED Rating Levels Among Certified Projects in Istanbul

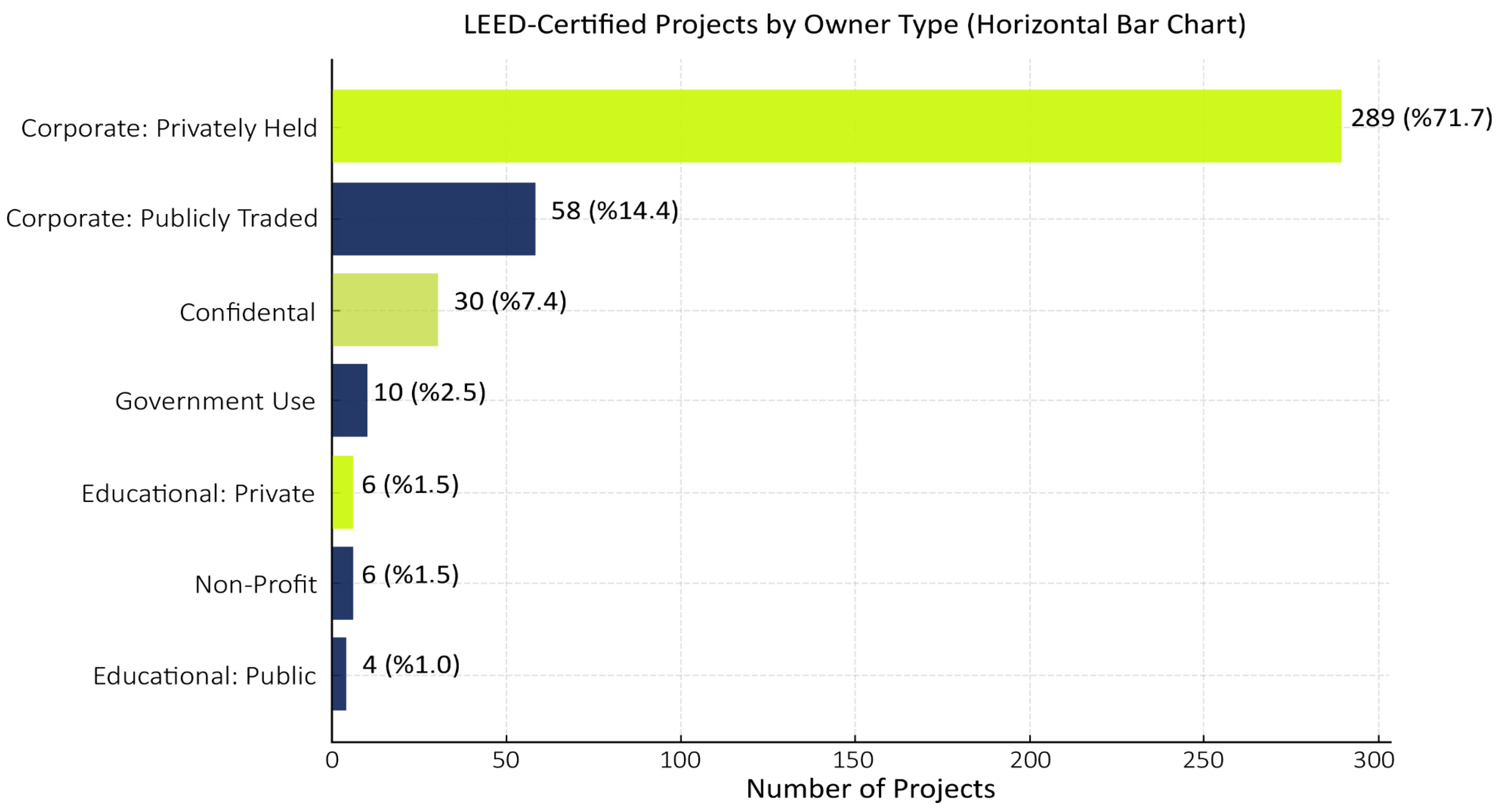

4.3. Type of Project Owner Organization

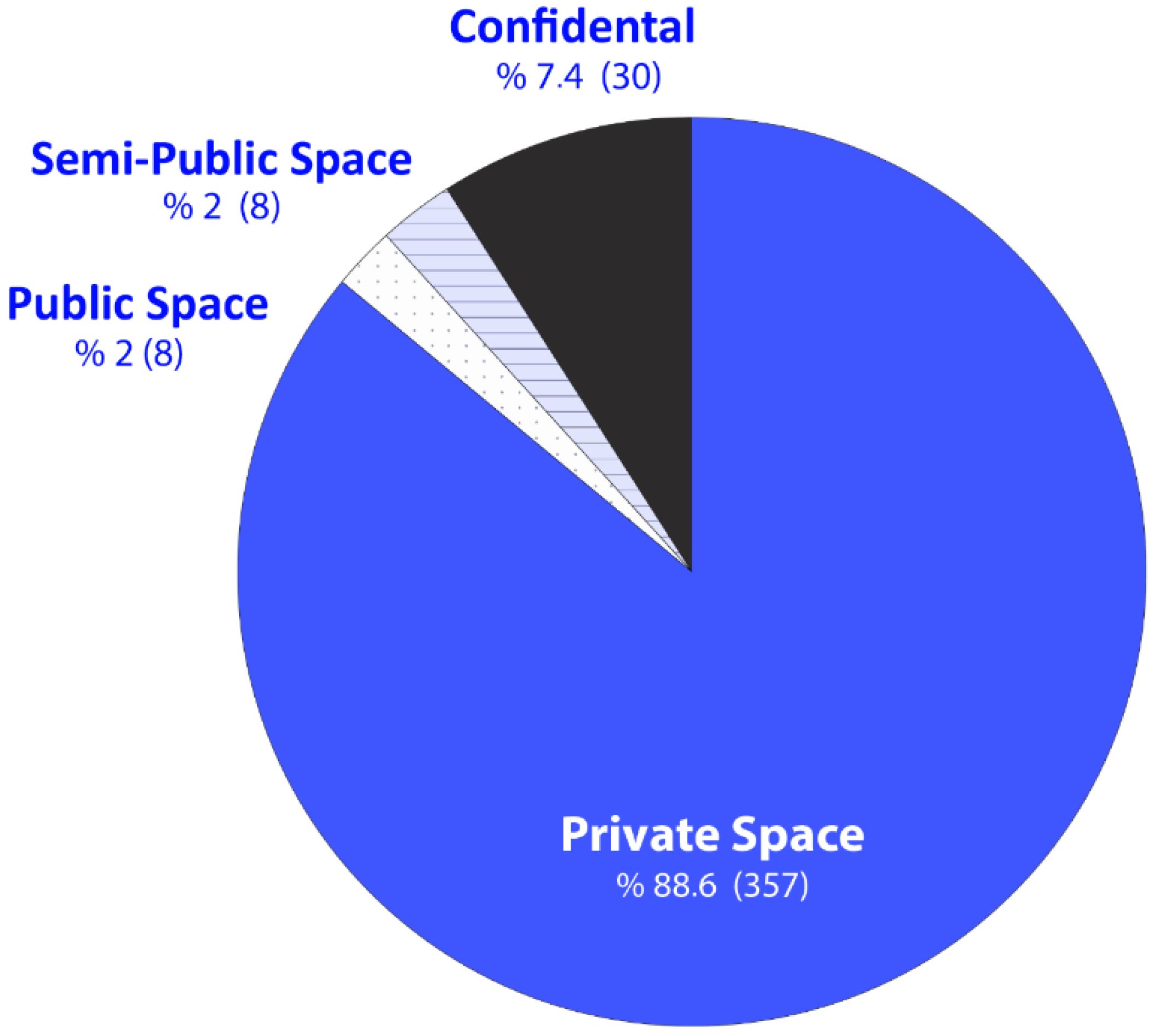

4.4. Distribution of LEED Projects by Access Type

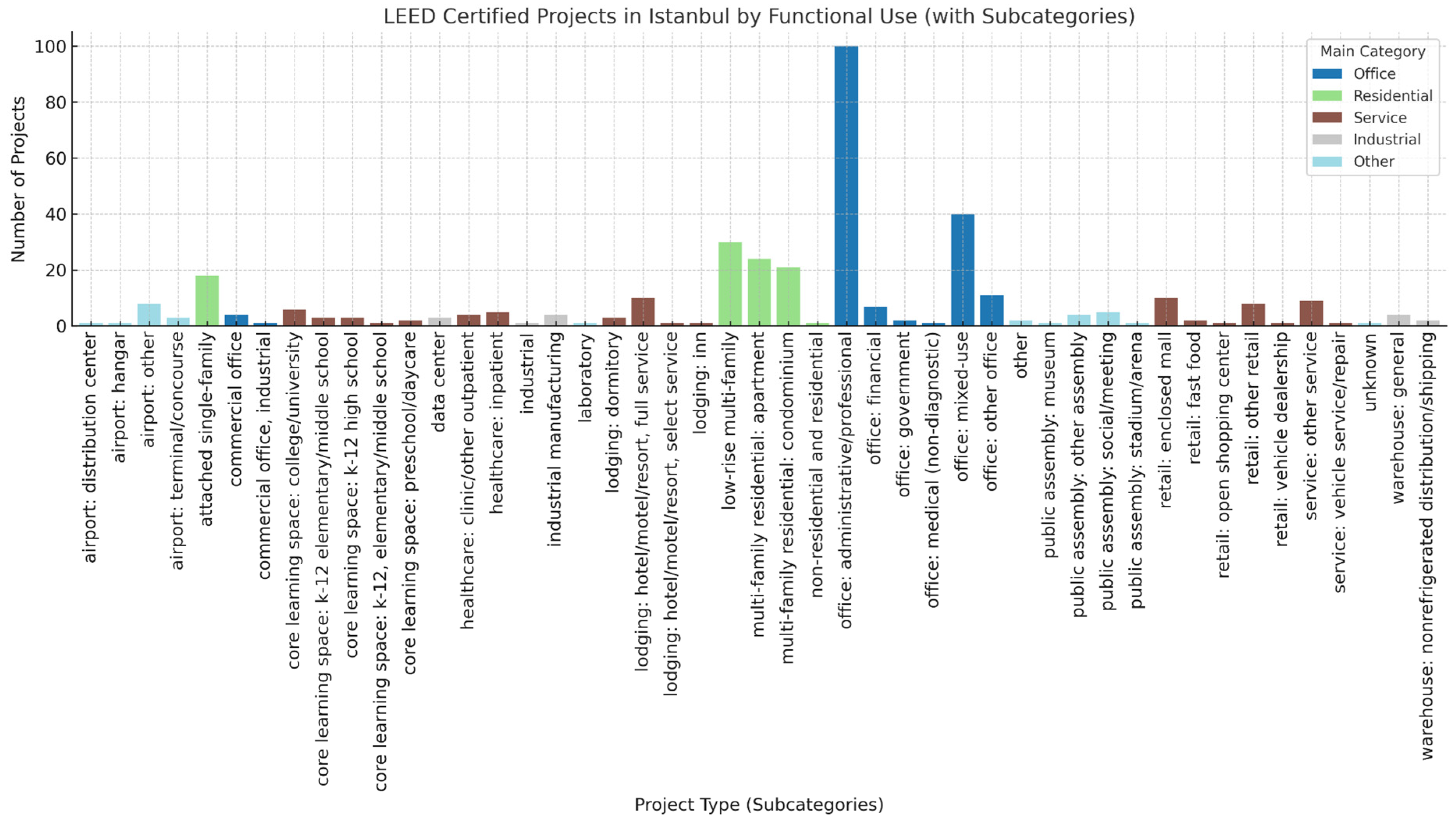

4.5. LEED Projects by Functional Use Type

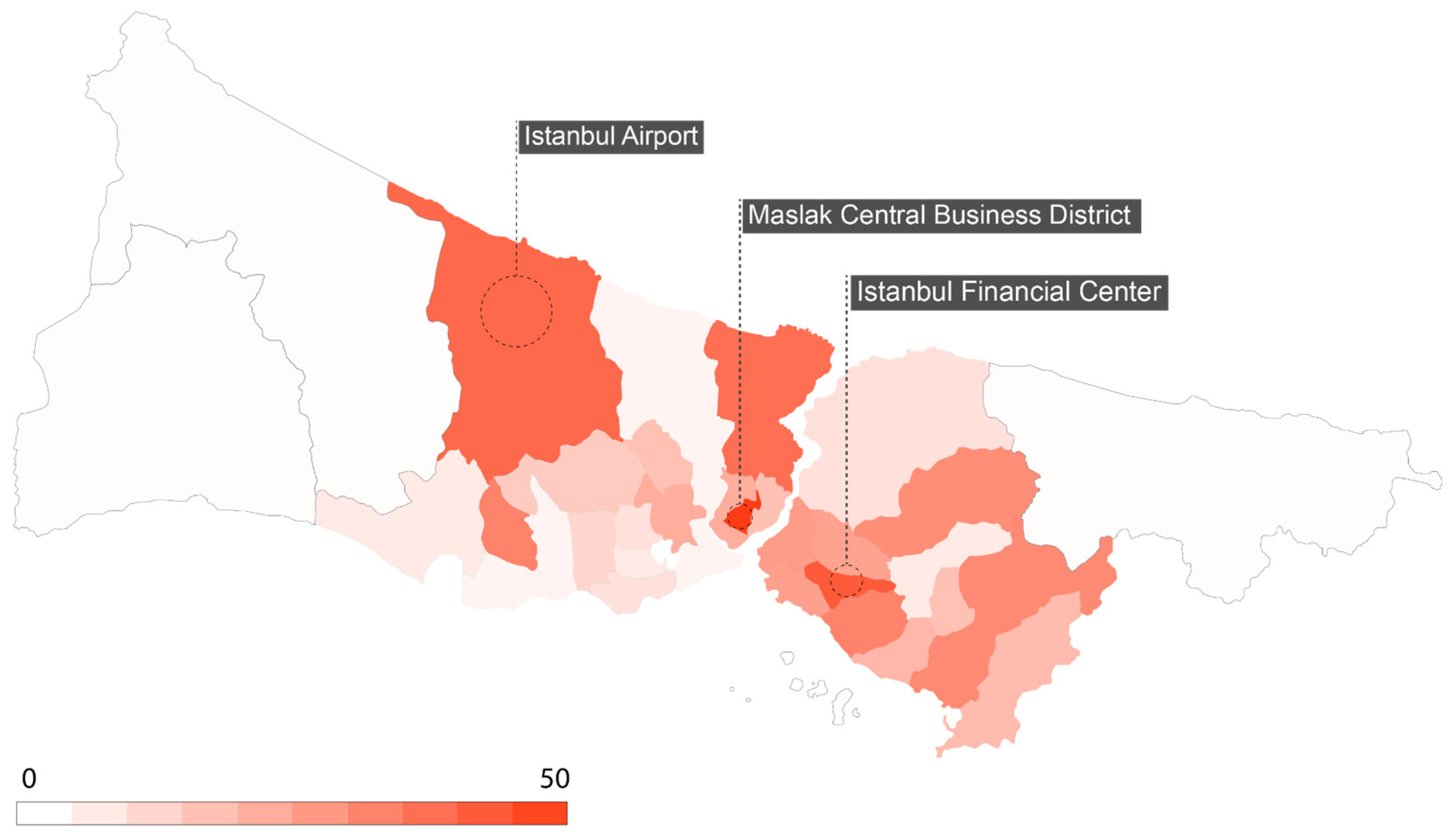

4.6. Exploratory Correlation Analysis: Green Building Density and Socio-Economic Vulnerability

5. Discussion

5.1. Market-Driven Sustainability: Temporal Trends of LEED Certification in Istanbul

5.2. The Dominance of Gold: LEED Certification as Strategic Branding in Istanbul

5.3. Green Privilege in the City: Who Benefits from LEED in Istanbul?

5.4. The Unequal Access to Green Buildings

5.5. Sustainability as Prestige and the Real Estate Logic of LEED in Istanbul

5.6. The Socio-Spatial Segregation of LEED-Certified Buildings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laclau, E.; Mouffe, C. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics; Verso: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Hope; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J. Neoliberalizing states: Thin policies/hard outcomes. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N.; Robbins, P. The neoliberalization of nature: Governance, privatization, enclosure and valuation. Cap. Nat. Soc. 2005, 16, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing space. In Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in Western Europe and North America; Brenner, N., Theodore, N., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.; Prudham, S. Neoliberal nature and the nature of neoliberalism. Geoforum 2004, 35, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B. Neoliberalism in the Oceans: “Rationalization,” Property Rights, and the Commons Question. Geoforum 2004, 35, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castree, N. Neoliberalising nature: Processes, effects, and evaluations. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, E.A.; Gautreau, P.; Oliveira, V.L. (Im)pertinences of a theoretical approach: The neoliberalization of nature. Soc. Nat. 2020, 32, 526–539. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Neoliberalizing nature? Market environmentalism in water supply in England and Wales. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.M. Neoliberal environmentalism, climate interventionism and the trade-climate nexus. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978; Senellart, M., Ed.; Burchell, G., Translator; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979; Senellart, M., Ed.; Burchell, G., Translator; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oels, A. Rendering climate change governable: From biopower to advanced liberal government. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2005, 7, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.; Cortese, C. Free market environmentalism and the neoliberal project: The case of the Climate Disclosure Standards Board. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciplet, D.; Roberts, J.T. Climate change and the transition to neoliberal environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 46, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Governmentality. In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality; Burchell, G., Gordon, C., Miller, P., Eds.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1991; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, D.J. The contested politics of climate change and the crisis of neo-liberalism. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2013, 12, 44–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yeeles, A.; Sosalla-Bahr, K.; Ninete, J.; Wittmann, M.; Jimenez, F.; Brittin, J. Social equity in sustainability certification systems for the built environment: Understanding concepts, value, and practice implications. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2023, 3, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, C. Global Justice and Neoliberal Environmental Governance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maltais, A.; McKinnon, C. (Eds.) The Ethics of Climate Governance; Rowman & Littlefield International: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Apocalypse forever? Theory Cult. Soc. 2010, 27, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeminne, G. Lost in translation: Climate denial and the return of the political. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, A. Post-politics contested: Why multiple voices on climate change do not equal politicization. EPC Politics Space 2019, 37, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepermans, Y.; Maeseele, P. The politicization of climate change: Problem or solution? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2016, 7, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, M.; Daloglu Cetinkaya, I.; Baykal Fide, E.; Haarstad, H. Diffusion of global climate policy: National depoliticization, local repoliticization in Turkey. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 81, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D. The climate of history: Four theses. Crit. Inq. 2009, 35, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methmann, C.P. “Climate protection” as empty signifier: A discourse-theoretical perspective on climate mainstreaming in world politics. Millennium 2010, 39, 345–372. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Gou, Z. Are Green Spaces More Available and Accessible to Green Building Users? A Comparative Study in Texas. Land 2023, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beder, S. Research note—Neoliberal think tanks and free market environmentalism. Environ. Politics 2001, 10, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareau, B.J. From Precaution to Profit: Contemporary Challenges to Environmental Protection in the Montreal Protocol; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M. Neoliberal urban environmentalism and the adaptive city: Towards a critical urban theory of climate change. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1348–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wu, J.; Zheng, S. Entrepreneurship, sustainability, and urban development. Small Bus. Econ. 2024, 62, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Paterson, M. A climate for business: Global warming, the state and capital. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 1998, 5, 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, L. Neoliberalism and the calculable world: The rise of carbon trading. In Upsetting the Offset: The Political Economy of Carbon Markets; Böhm, S., Ed.; Mayfly: London, UK, 2009; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Turhan, E.; Gündoğan, A.C. Price and prejudice: The politics of carbon market establishment in Turkey. Turk. Stud. 2019, 20, 512–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, A. Things are getting worse on our way to catastrophe: Neoliberal environmentalism, repressive desublimation, and the autonomous ecoconsumer. Crit. Sociol. 2020, 47, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremstad, A.; Paul, M. Neoliberalism and climate change: How the free-market myth has prevented climate action. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 197, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Peck, J.; Theodore, N. Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Glob. Netw. 2010, 10, 182–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudelson, J. Green Building A to Z: Understanding the Language of Green Building; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment in the construction sector: Rating systems and rated buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J. Green buildings: An overview of progress. Fl. St. Univ. J. Land Use Environ. Law 2018, 19, 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaosen, H.; Yu, A. Analytical review of green building development studies. J. Green Build. 2017, 12, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, N.; Vimpari, J.; Junnila, S. A review of the impact of green building certification on the cash flows and values of commercial properties. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.W.; Kuan, K.L. Implementing BEAM Plus for BIM-based sustainability analysis. Autom. Constr. 2014, 44, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K., Tignor, M.M.B., Miller, H.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; 996p; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar4/wg1/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Circo, C.J. Using mandates and incentives to promote sustainable construction and green building projects in the private sector: A call. Penn State Law Rev. 2007, 112, 731–782. [Google Scholar]

- Laustsen, J. Energy Efficiency Requirements in Building Codes: Energy Efficiency Policies for New Buildings; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Olabi, A.; Shehata, N.; Issa, U.; Mohamed, O.; Mahmoud, M.; Abdelkareem, M.; Abdelzaher, M. The role of green buildings in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 25, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olubunmi, O.A.; Xia, P.B.; Skitmore, M. Green building incentives: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, D.T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Naismith, N.; Zhang, T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Tookey, J. A critical comparison of green building rating systems. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Z.; Hossain, M.; Wang, L. The economic and cultural motives of green price premium. Br. Account. Rev. 2025, 57, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. The double-edged sword effect of green certification: Empirical evidence from an online travel platform. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 65, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, Y.; Davidson, B.G.J.; George, J.P.; Muttungal, P.V.E. Eco-conscious consumers’ green real estate decisions in India: The role of social commerce. Prop. Manag. 2025, 43, 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L.K. Green construction costs and benefits: Is national regulation warranted? Nat. Resour. Environ. 2009, 24, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- USGBC. Top 10 Countries for LEED National Profile: Turkey. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/top-10-countries-leed-national-profile-turkey (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Pushkar, S. Impact of “Optimize Energy Performance” Credit Achievement on the Compensation Strategy of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Existing Buildings Gold-Certified Office Space Projects in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain. Buildings 2023, 13, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, A.-K.; Jones, G. Private regulation, institutional entrepreneurship and climate change: A business history perspective. In Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 24-041; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Newsham, G.R.; Mancini, S.; Birt, B.J. Do LEED-certified buildings save energy? Yes, but…. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H. Do LEED-certified buildings save energy? Not really…. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, A. Greenwashing as an example of ecological marketing: A misleading practice. Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2009, 12, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Profits and Sustainability. A History of Green Entrepreneurship; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, B.; Boyd, N.; McGoun, E. Greenbacks, green banks, and greenwashing via LEED: Assessing banks’ performance in sustainable construction. Sustainability 2020, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurani, D.; Rivard, N. The limits of LEED. In Architecture and Sustainability: Critical Perspectives for Integrated Design—Generating Sustainability Concepts from Architectural Perspectives; Ahmed, Z.K., Allacker, K., Eds.; Acco Publishing: Leuven, Belgium, 2015; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski, A.J. LEEDigation: The risks, why we don’t see more, and practical guidance related to green building contracts. Real Estate Law J. 2010, 39, 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, B. Rough Guide to Sustainability, 3rd ed.; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman, W. Sustainable development: Is it a useful concept? Environ. Values 1994, 3, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J.; McKinnon, C. The ethics of climate-induced community displacement and resettlement. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2018, 9, e519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, L.V. Regenerative—The new sustainable? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.M.; López-Mejuto, U.; García Docampo, M.; Varela-García, F.A. Sustainability, spatial justice and social cohesion in city planning: What does a case study on urban renaturalisation teach us? Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A. Renaturing for urban wellbeing: A socioecological perspective on green space quality, accessibility, and inclusivity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.; Figari, H.; Krange, O.; Gundersen, V. Environmental justice in a very green city: Spatial inequality in exposure to urban nature, air pollution, and heat in Oslo, Norway. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Haase, A.; Heiland, S. Gentrification through green regeneration? Analyzing the interaction between inner-city green space development and neighborhood change in the context of regrowth: The case of Lene-Voigt-Park in Leipzig, Eastern Germany. Land 2020, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.; Brand, A.L. From landscapes of utopia to the margins of the green urban life: For whom is the new green city? City 2018, 22, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Newman, L. Sustainable development for some: Green urban development and affordability. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Lamarca, M.; Anguelovski, I.; Cole, H.V.S.; Connolly, J.; Argüelles, L.; Baró, F.; Loveless, S.; Pérez del Pulgar, C.; Shokry, G. Urban green boosterism and city affordability: For whom is the ‘branded’ green city? Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszkiewicz, E. Towards green gentrification? The interplay between residential change, the housing market, and park proximity. Hous. Stud. 2024, 39, 2280–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.A.; Lewis, T.L. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, H.V.; García-Lamarca, M.; Connolly, J.J.; Anguelovski, I. Are green cities healthy and equitable? Unpacking the relationship between health, green space, and gentrification. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Németh, J. Green gentrification or ‘just green enough’: Do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not? Urban Stud. 2019, 57, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Pearsall, H.; Shokry, G.; Checker, M.; Maantay, J.; Gould, K.; Lewis, T.; Marolo, A.; Roberts, J.T. Why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 26139–26143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Cole, H.; Garcia-Lamarca, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Baró, F.; Martin, N.; Conesa, D.; Shokry, G.; del Pulgar, C.P.; et al. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 31572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewartowska, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Oscilowicz, E.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Cole, H.; Shokry, G.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.; Connolly, J.J. Racial inequity in green infrastructure and gentrification: Challenging compounded environmental racisms in the green city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2024, 48, 294–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Stupar, A. The limits of growth: A case study of three mega-projects in Istanbul. Cities 2017, 60, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, J.; Turkmen, H. Bulldozer neo-liberalism in Istanbul: The state-led construction of property markets and the displacement of the urban poor. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enlil, Z.M. The neoliberal agenda and the changing urban form of Istanbul. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkün, A. Urban regeneration and hegemonic power relationships. Int. Plan. Stud. 2011, 16, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzey, Ö. The last round in restructuring the city: Urban regeneration becomes Turkey’s state policy of disaster prevention. Cities 2016, 50, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, S.; Atmiş, E.; Gormüş, S. The impact of economic growth oriented development policies on landscape changes in Istanbul Province in Turkey. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istil, S.A.; Górecki, J.; Diemer, A. Study on Certification Criteria of Building Energy and Environmental Performance in the Context of Achieving Climate Neutrality. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, O. The negative effects of the construction boom on urban planning and environment in Turkey: Unraveling the role of the public sector. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, Ö.N.; Acar, S. Assessing a greening tool through the lens of green gentrification: Socio-spatial change around the Nation’s Gardens of Istanbul. Cities 2024, 150, 105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyalı, A.; Baykan, A. An analysis of Validebağ Grove from the lens of urban political ecology. Manisa Celal Bayar Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 22, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamak, N.; Koçak, S.; Samut, S. Türkiye’de inşaat sektörünün kısa ve uzun dönem dinamikleri. J. Econ. Manag. Res. 2018, 7, 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Construction Turnover and Production Indices, 2004–2024. Available online: http://www.tuik.gov.tr (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- CM Mimarlık. (n.d.). Tekfen Hepİstanbul. Available online: https://cmmimarlik.com.tr/proje/tekfen-hepistanbul/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rui, J. Green disparities, happiness elusive: Decoding the spatial mismatch between green equity and happiness from vulnerable perspectives. Cities 2025, 163, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N.; McCarthy, J.; Prudham, W.S.; Robbins, P. (Eds.) Neoliberal Environments: False Promises and Unnatural Consequences; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- TMMOB. 3. Havalimanı Teknik Raporu; Türk Mühendis ve Mimar Odaları Birliği, İstanbul İl Koordinasyon Kurulu: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- TMMOB. Kanal İstanbul ve Yenişehir Rezerv Alanı Teknik İnceleme Raporu; Türk Mühendis ve Mimar Odaları Birliği, Çevre Mühendisleri Odası İstanbul Şubesi: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- İstanbul Planlama Ajansı (İPA). Kanal İstanbul Çalıştay Raporu (Canal Istanbul Workshop Report); iPA Yayınları: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2020; Available online: https://ipa.istanbul/yayinlarimiz/genel/kanal-istanbul-calistayi-raporu/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Giritlioglu, P.P. From mega-projects and environmental sustainability perspective: An artificial waterway project overview—Canal Istanbul Project. In Understanding Environmental Policy After COVID-19; Peter Lang: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aysev, E. Urbanization processes of Northern Istanbul in the 2000s: Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge and the Northern Marmara Highway. METU J. Fac. Archit. 2022, 39, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 2008, 53, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Demirtas, E.; Ayas Onol, T. The Politics of Green Buildings: Neoliberal Environmental Governance and LEED’s Uneven Geography in Istanbul. Buildings 2026, 16, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020363

Demirtas E, Ayas Onol T. The Politics of Green Buildings: Neoliberal Environmental Governance and LEED’s Uneven Geography in Istanbul. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020363

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemirtas, Emre, and Tugba Ayas Onol. 2026. "The Politics of Green Buildings: Neoliberal Environmental Governance and LEED’s Uneven Geography in Istanbul" Buildings 16, no. 2: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020363

APA StyleDemirtas, E., & Ayas Onol, T. (2026). The Politics of Green Buildings: Neoliberal Environmental Governance and LEED’s Uneven Geography in Istanbul. Buildings, 16(2), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020363