Impact of Transformational Leadership on New-Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Transformational Leadership

2.2. New Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior

2.3. The Relationship Between the Above Two Concepts

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Transformational Leadership Scale

3.1.2. Safety Behavior Scale

3.2. Procedure and Sample

3.2.1. Research Objects and Procedures

3.2.2. Sample Characteristics

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

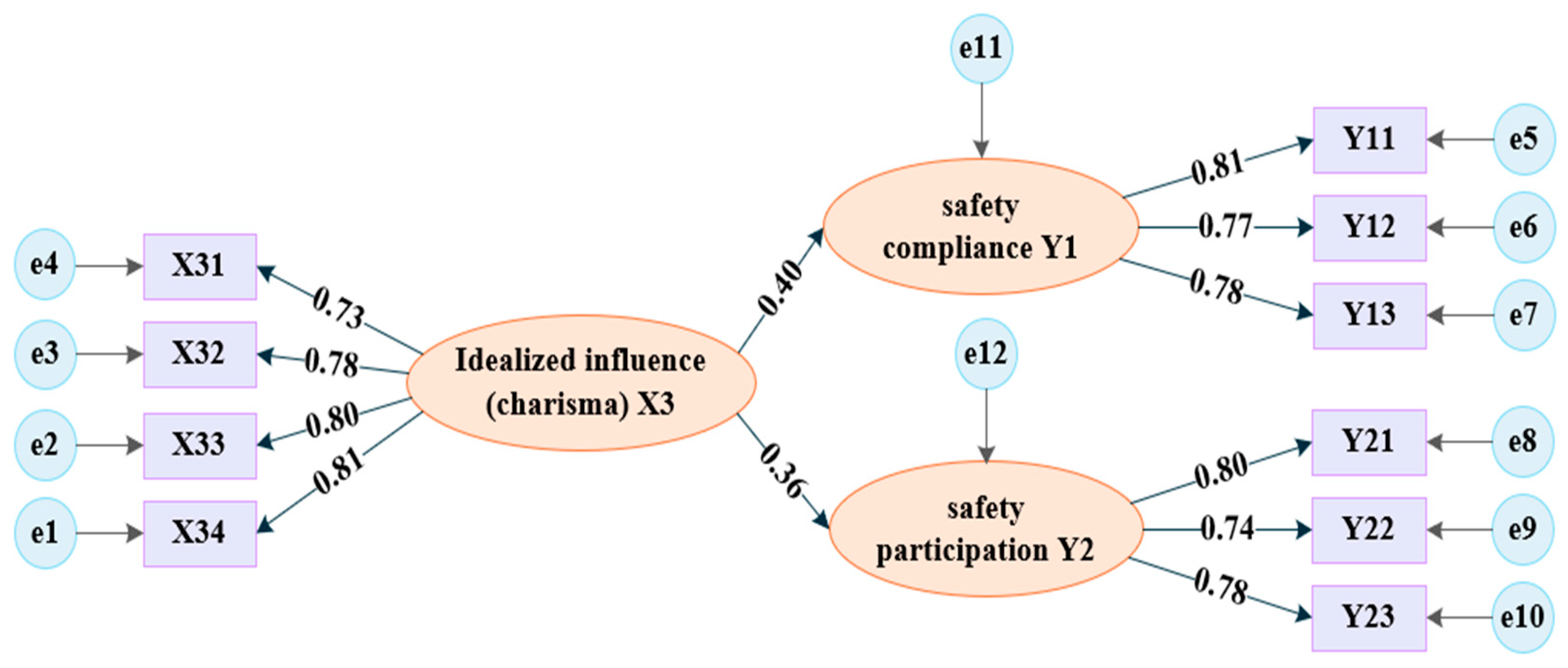

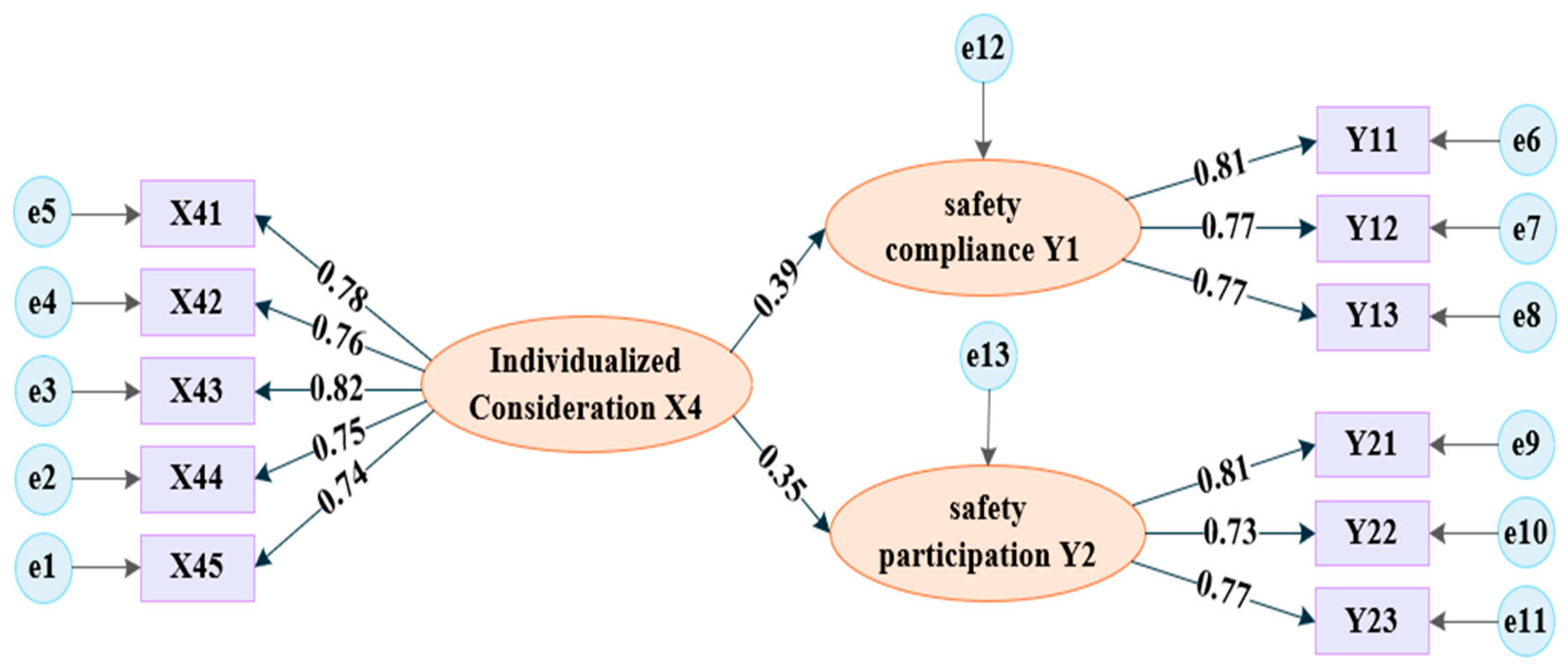

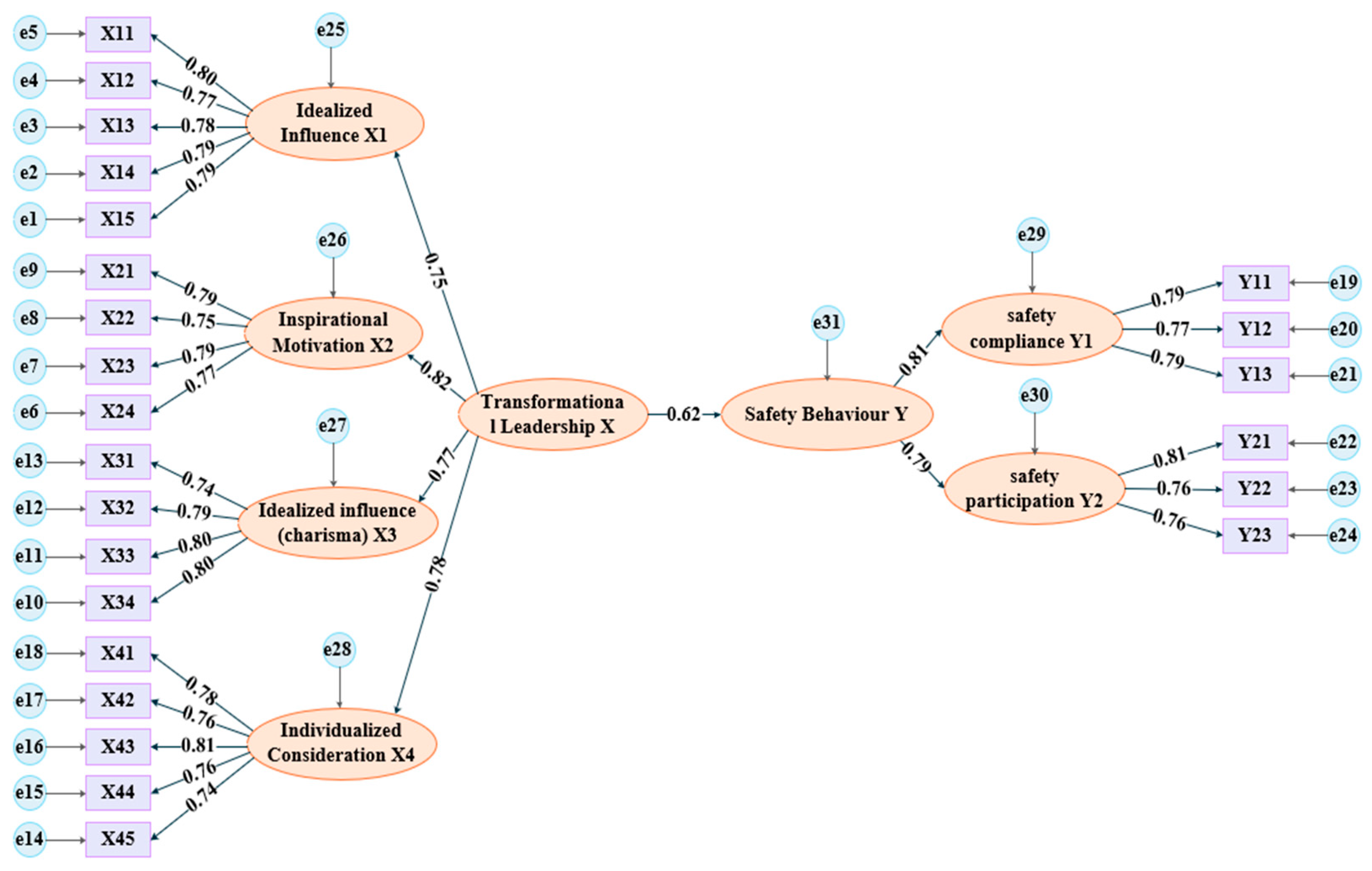

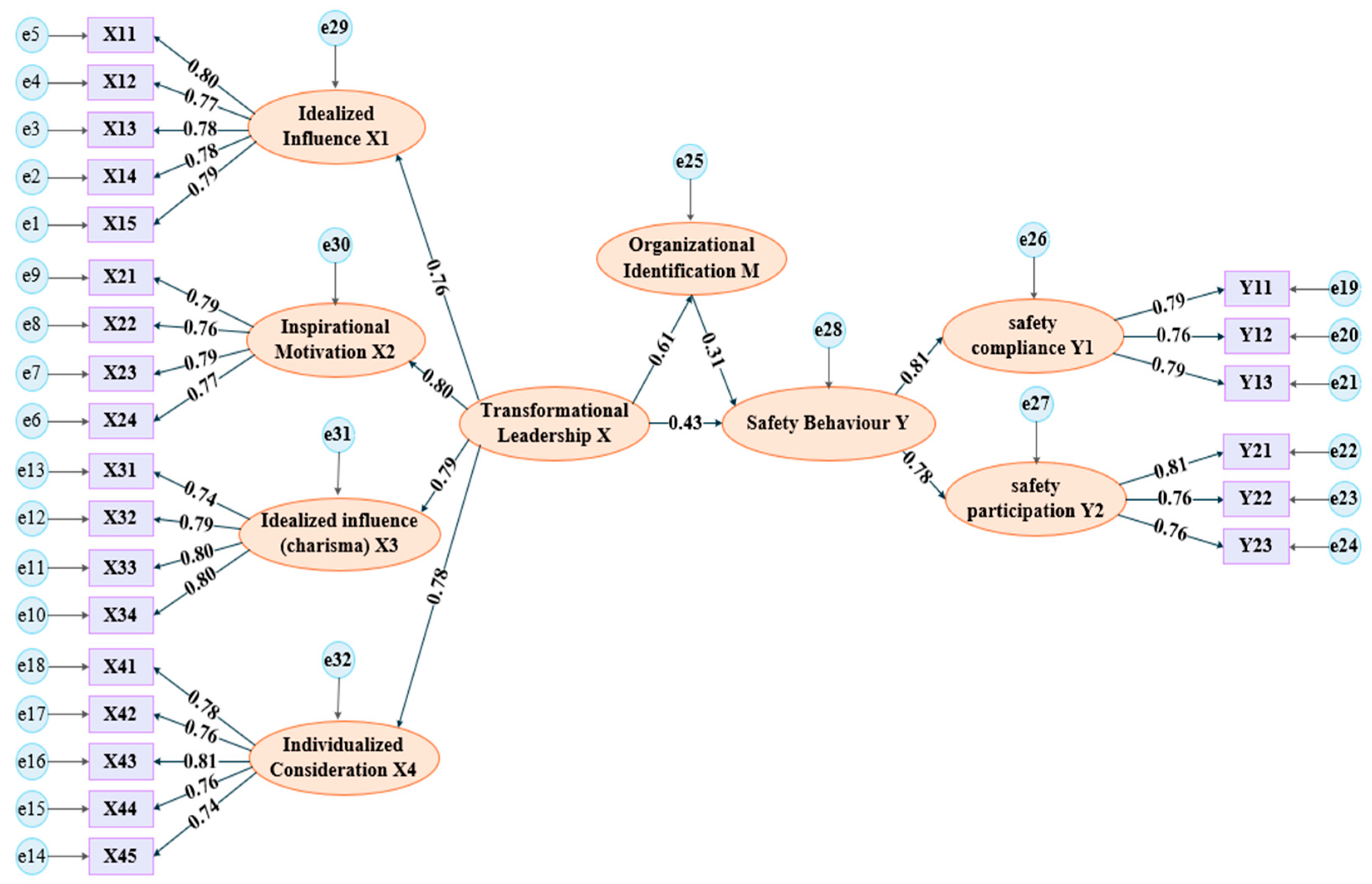

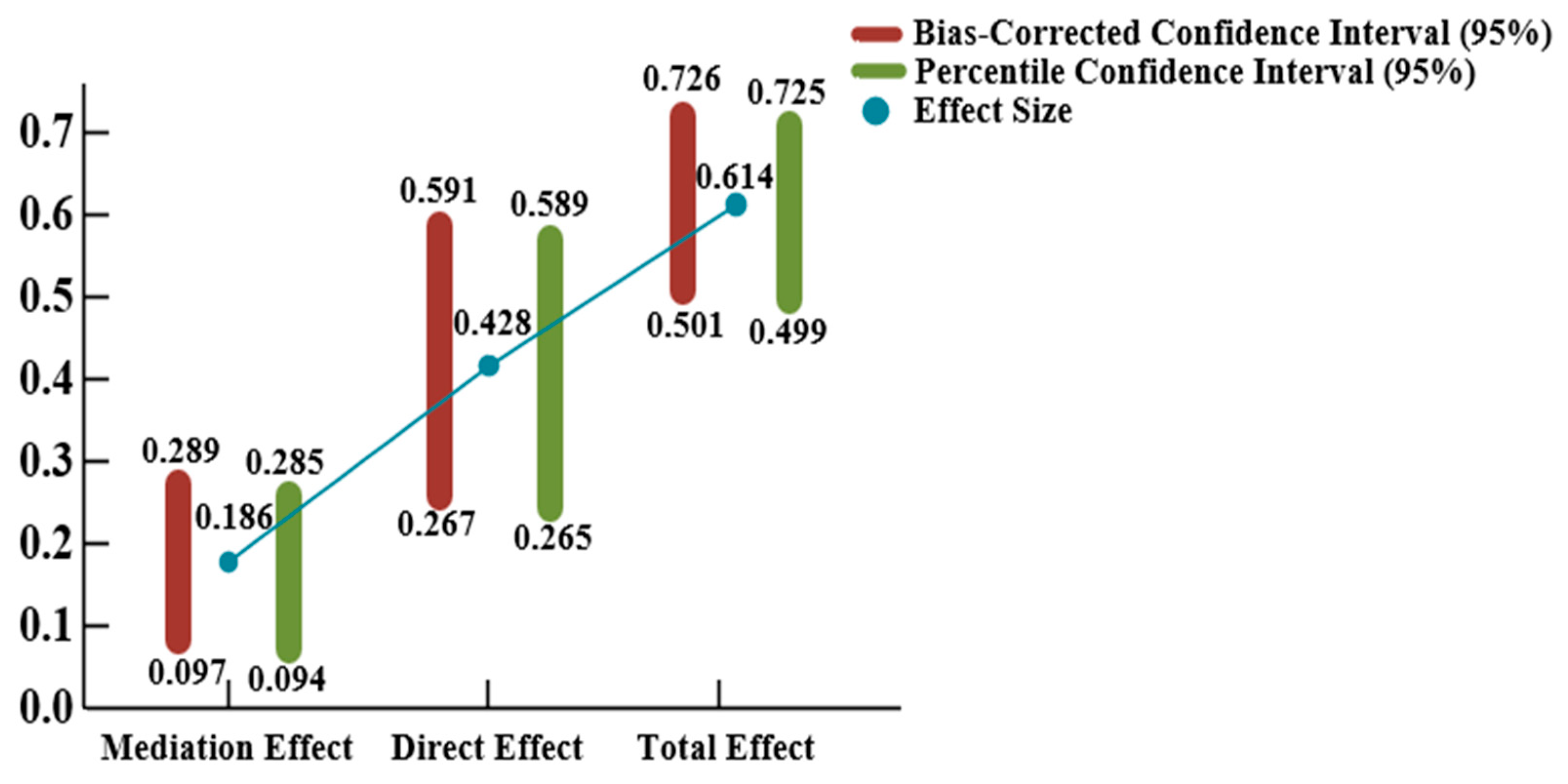

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.3. Comparative Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Research Constraints and Future Prospects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Demographic Information

Appendix A.2. Main Survey

Appendix A.2.1. Transformational Leadership

| Item | Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | My leader is selfless and serves the public interest, not personal gain. | |||||

| 2 | My leader is the first to bear hardships and the last to enjoy comforts. | |||||

| 3 | My leader devotes himself/herself to the job without personal calculation. | |||||

| 4 | My leader is willing to sacrifice personal interests for the benefit of the unit/department. | |||||

| 5 | My leader prioritizes collective and others’ interests above his/her own. | |||||

| 6 | My leader never claims credit for others’ work or achievements. | |||||

| 7 | My leader shares the hardships and joys with subordinates. | |||||

| 8 | My leader treats subordinates fairly. | |||||

| 9 | My leader helps subordinates understand the department’s future vision. | |||||

| 10 | My leader ensures subordinates understand the department’s philosophy and goals. | |||||

| 11 | My leader explains the long-term significance of our work. | |||||

| 12 | My leader paints a compelling vision of the future for us. | |||||

| 13 | My leader provides subordinates with clear objectives and direction. | |||||

| 14 | My leader often explains how our work contributes to the organization’s overall goals. | |||||

| 15 | My leader considers subordinates’ personal circumstances when interacting with them. | |||||

| 16 | My leader is willing to help subordinates solve personal or family difficulties. | |||||

| 17 | My leader frequently communicates with us to understand our work, life, and family situation. | |||||

| 18 | My leader patiently instructs subordinates and answers our questions. | |||||

| 19 | My leader shows concern for subordinates’ work, well-being, and growth, and offers career advice. | |||||

| 20 | My leader fosters an environment that allows us to utilize our strengths. | |||||

| 21 | My leader possesses strong professional expertise. | |||||

| 22 | My leader is open-minded and has a strong sense of innovation. | |||||

| 23 | My leader is passionate about work and has a strong sense of commitment and initiative. | |||||

| 24 | My leader is highly dedicated to the job and always maintains a high level of enthusiasm. | |||||

| 25 | My leader continuously engages in learning to enhance his/her capabilities. |

Appendix A.2.2. Safety Behavior

| Item | Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I use all necessary safety equipment to perform my job. | |||||

| 2 | I correct safety procedures while working. | |||||

| 3 | I ensure the highest level of safety in my work. | |||||

| 4 | I promote safety programs within the organization. | |||||

| 5 | I put extra effort into improving workplace safety. | |||||

| 6 | I voluntarily carry out tasks or activities that help improve workplace safety. |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Demographic Information

Appendix B.2. Main Survey

Appendix B.2.1. Transformational Leadership

| Item | Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | My leader is selfless and serves the public interest, not personal gain. | |||||

| 2 | My leader devotes himself/herself to the job without personal calculation. | |||||

| 3 | My leader is willing to sacrifice personal interests for the benefit of the unit/department. | |||||

| 4 | My leader shares the hardships and joys with subordinates. | |||||

| 5 | My leader treats subordinates fairly. | |||||

| 6 | My leader helps subordinates understand the department’s future vision. | |||||

| 7 | My leader ensures subordinates understand the department’s philosophy and goals. | |||||

| 8 | My leader explains the long-term significance of our work. | |||||

| 9 | My leader paints a compelling vision of the future for us. | |||||

| 10 | My leader considers subordinates’ personal circumstances when interacting with them. | |||||

| 11 | My leader is willing to help subordinates solve personal or family difficulties. | |||||

| 12 | My leader frequently communicates with us to understand our work, life, and family situation. | |||||

| 13 | My leader shows concern for subordinates’ work, well-being, and growth, and offers career advice. | |||||

| 14 | My leader possesses strong professional expertise. | |||||

| 15 | My leader is open-minded and has a strong sense of innovation. | |||||

| 16 | My leader is highly dedicated to the job and always maintains a high level of enthusiasm. | |||||

| 17 | My leader continuously engages in learning to enhance his/her capabilities. | |||||

| 18 | My leader tackles problems courageously and is adept at handling challenging issues. |

Appendix B.2.2. Safety Behavior

| Item | Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I use all necessary safety equipment to perform my job. | |||||

| 2 | I correct safety procedures while working. | |||||

| 3 | I ensure the highest level of safety in my work. | |||||

| 4 | I promote safety programs within the organization. | |||||

| 5 | I put extra effort into improving workplace safety. | |||||

| 6 | I voluntarily carry out tasks or activities that help improve workplace safety. |

References

- Zeng, R.; Chini, A.; Ries, R. Innovative Design for Sustainability. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 28, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Khan, R. Trend Analysis of Construction Industrial Accidents in Korea from 2011 to 2015. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Siddiqui, S.; Suk, S.J.; Chi, S.; Kim, C. Trends of Fall Accidents in the U.S. Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C.K.; Li, R.Y.M. How Does Social Exchange Theory, Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange Affect Construction Practitioners’ Perception on Construction Safety? An Asymmetric Information Approach. In Construction Safety: Economics and Informatics Perspectives; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Wu, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H. Mechanisms of Safety-Transformational Leadership Influence on Construction Workers’ Safety Voice: A Dual-Mediation Model of Psychological Contract and Safety Motivation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estudillo, B.; Carretero-Gómez, J.M.; Forteza, F.J. The Impact of Occupational Accidents on Economic Performance: Evidence from the Construction. Saf. Sci. 2024, 177, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Peng, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. How Job Satisfaction Affects Professionalization Behavior of New-Generation Construction Workers: A Model Based on Theory of Planned Behavior. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 2672–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.; Schriesheim, C.A.; Murphy, C.J.; Stogdill, R.M. Toward a Contingency Theory of Leadership Based upon the Consideration and Initiating Structure Literature. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1974, 12, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Mo, J. How Does Supportive Leadership Impact the Safety Behaviors of the New Generation of Construction Workers? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septriani, S. Transformational Leadership Style and Innovative Behavior with Self-Efficacy as a Mediator. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 1, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp, E.A. The Influence of Supervisor Leadership Practices and Perceived Group Safety Climate on Employee Safety Performance. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, X.; Ni, J. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Employee Sustainable Performance: The Mediating Role of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Iqbal, J.; Iqbal, S.M.J.; Imran, M. Sustainable Leadership and Employee Innovative Behavior: Discussing the Mediating Role of Creative Self-efficacy. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huang, R.; Qiao, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Li, K.; Zhao, L. How Perceived Leader–Member Exchange Differentiation Affects Construction Workers’ Safety Citizenship Behavior: Organizational Identity and Felt Safety Responsibility as Mediators. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S. Research on the Relationship Between Self-Identity and Organizational Citizenship Behavior of the New Generation Knowledge Workers—The Mediating Effects of Organizational Identification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 14–17 December 2020; pp. 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings 2025, 15, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Ro: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780060105884. [Google Scholar]

- Longshore, J.M.; Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Stogdill, R.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications; Free Press: New York City, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 9780029015001. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Weber, T.J. Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammarino, F.J.; Dubinsky, A.J. Transformational Leadership Theory: Using Levels of Analysis to Determine Boundary Conditions. Pers. Psychol. 1994, 47, 787–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780803952362. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Two Decades of Research and Development in Transformational Leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, S.D.; Yammarino, F.J.; Atwater, L.E.; Spangler, W.D. Transformational Leadership and Team Performance. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2004, 17, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjing, L.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Ahmed Bhutto, N. Unlocking Employees’ Green Creativity: The Effects of Green Transformational Leadership, Green Intrinsic, and Extrinsic Motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Zafar, Z.; Fan, M.; Sánchez Limón, M.L.; Khaskheli, M.B. Employee Performance under Transformational Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Mediated Model. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriesheim, C.A.; Castro, S.L.; Zhou, X.T.; DeChurch, L.A. An Investigation of Path-Goal and Transformational Leadership Theory Predictions at the Individual Level of Analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. PsycTests Dataset 2011, 47, 787–811. [Google Scholar]

- Bycio, P.; Hackett, R.D.; Allen, J.S. Further Assessments of Bass’s (1985) Conceptualization of Transactional and Transformational Leadership. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the Components of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Using the Multifactor Leadership. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, H.W. Industrial Accident Prevention. A Scientific Approach; McGraw-Hill Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.; Hart, P. The Impact of Organizational Climate on Safety Climate and Individual Behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadfam, I.; Ghasemi, F.; Kalatpour, O.; Moghimbeigi, A. Constructing a Bayesian Network Model for Improving Safety Behavior of Employees at Workplaces. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Safety Helmet Monitoring on Construction Sites Using YOLOv10 and Advanced Transformer Architectures with Surveillance and Body-Worn Cameras. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Automated Non-PPE Detection on Construction Sites Using YOLOv10 and Transformer Architectures for Surveillance and Body Worn Cameras with Benchmark Datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. Impact of the Supervisor on Worker Safety Behavior in Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.-Y.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of Job Stressors and Stress on the Safety Behavior and Accidents of Construction Workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; McCabe, B.; Jia, G. Effect of Leader-Member Exchange on Construction Worker Safety Behavior: Safety Climate and Psychological Capital as the Mediators. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, D. How Leaders and Coworkers Affect Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Integrative Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Suwaidi, M.S.; Jabeen, F.; Al Nahyan, M.T.; Farouk, S.; Hussain, M. Impact of Authentic Leadership on Employee Safety Performance: Role of Knowledge Hoarding, Support, and Passion. Saf. Sci. 2025, 192, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slil, E.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Impact of Safety Leadership and Employee Morale on Safety Performance: The Moderating Role of Harmonious Safety Passion. Buildings 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, K.; Gibbons, A.M.; Johnson, S.K.; Cigularov, K.P.; Chen, P.Y.; Rosecrance, J.C. The Differential Effects of Transformational Leadership Facets on Employee Safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; Teed, M. Employer Safety Obligations, Transformational Leadership and Their Interactive Effects on Employee Safety Performance. Saf. Sci. 2017, 91, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. The Role of Safety Leadership and Working Conditions in Safety Performance in Process Industries. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2017, 50, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Shahzad, K.; Khan, A.K. Role of Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership in Fostering Extra-Role Behaviors through Psychological Contract Fulfillment among Frontline Workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 30, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, K. The Structure and Measurement of Transformational Leadership in China. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 37, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zeng, H.; Tang, J. A Study of Safety Behavior of the New Generation of Construction Workers Based on the Structural Equation Model. J. Wuyi Univ. 2025, 39, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Golabchi, H.; Pereira, E.; Lefsrud, L.; Mohamed, Y. Proposal of a Safety Maturity Framework in Construction: Implementing Leading Indicators for Proactive Safety Management. J. Saf. Sustain. 2025, 2, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammad, S.; Mostafa, S.; Stewart, R.A. Development of a Safety Oriented Framework for Fall Prevention in Construction Projects Using Smart PLS-SEM Analysis. J. Saf. Sustain. 2025, 2, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Distribution | Male | 347 | 86.5 |

| Female | 54 | 13.5 | |

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | |

| Age Range | ≤24 years old | 62 | 15.5 |

| 25–34 years old | 217 | 54.1 | |

| 35–44 years old | 122 | 30.4 | |

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | |

| Years of Service | <1 year | 54 | 13.5 |

| 1–5 years | 178 | 44.4 | |

| 6–10 years | 139 | 34.7 | |

| >10 years | 30 | 7.5 | |

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | |

| Tenure with Leader | <1 year | 178 | 44.4 |

| 1–5 years | 154 | 38.4 | |

| 6–10 years | 58 | 14.5 | |

| >10 years | 11 | 2.7 | |

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 281 | 70.1 |

| Unmarried | 120 | 29.9 | |

| Total | 401 | 100.0 | |

| Statistical Measurement | Indicator Name | Fit Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Fit Statistics | χ2/df | 1~5, Model Acceptable |

| RMSEA | <0.08, The Smaller the Better | |

| GFI | >0.90, Model Acceptable | |

| AGFI | >0.90, Model Acceptable | |

| Relative Fit Statistics | IFI | >0.90, Model Acceptable |

| CFI | >0.90, Model Acceptable | |

| NFI | >0.90, Model Acceptable |

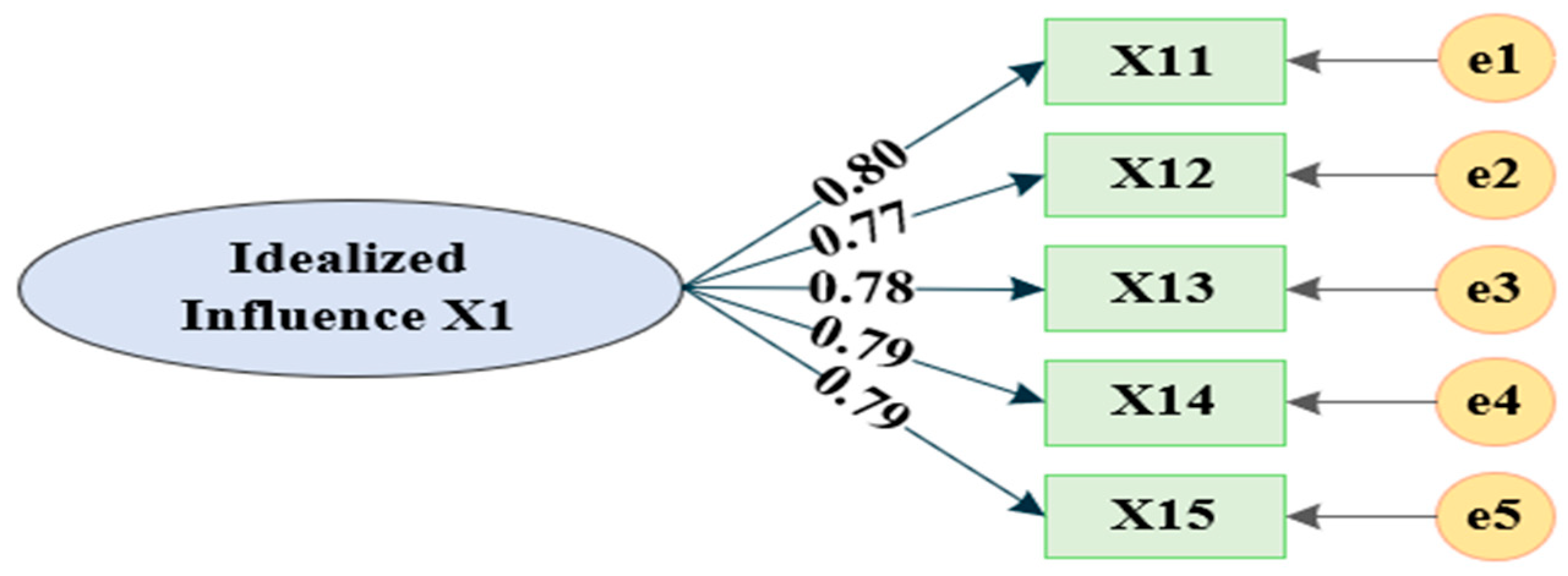

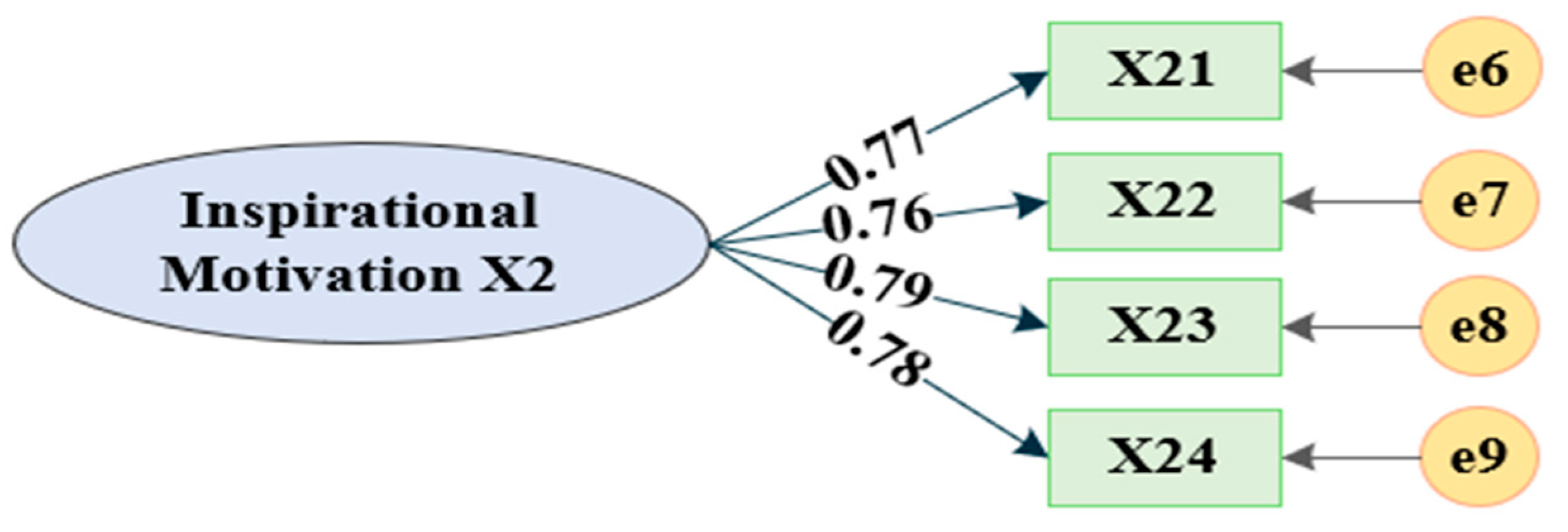

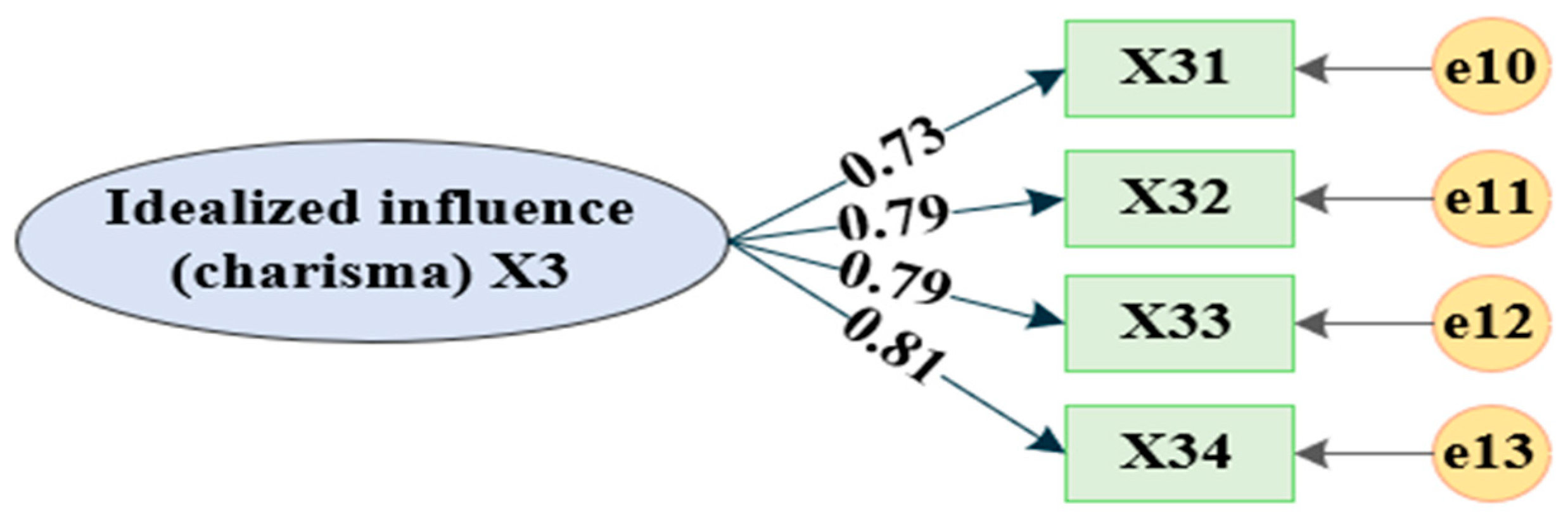

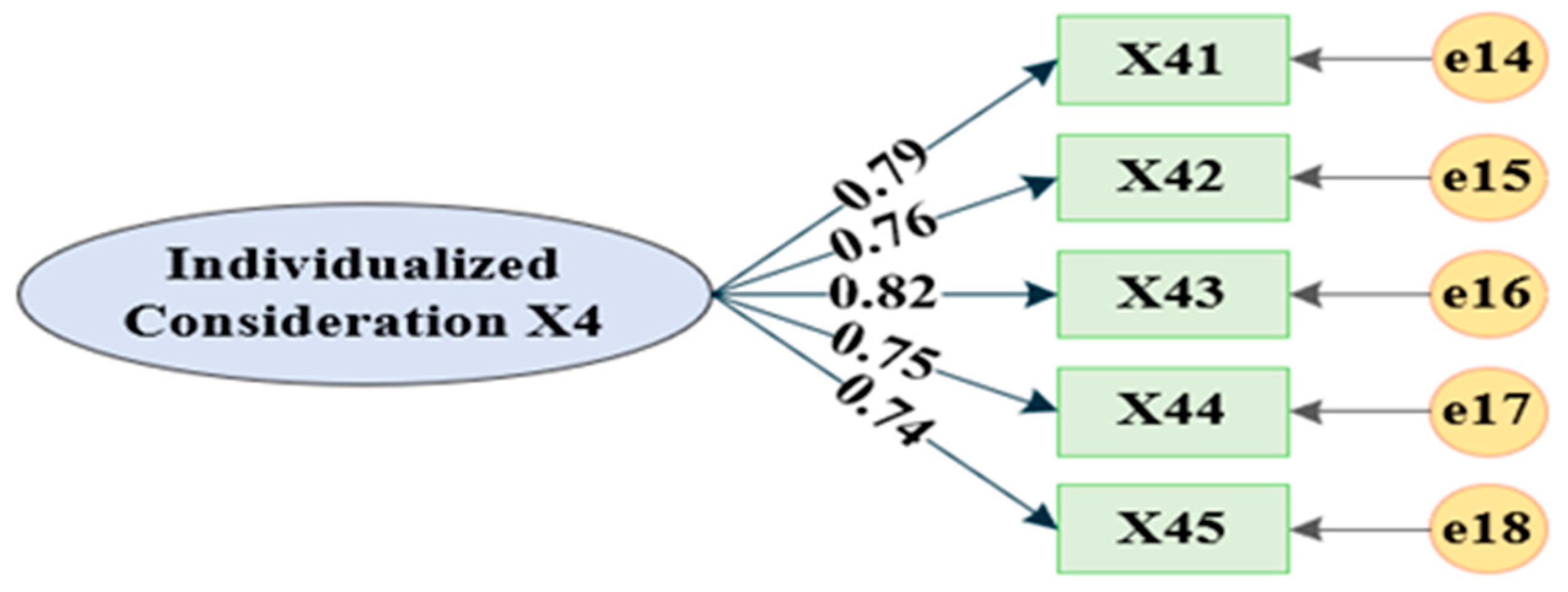

| Variable | Indicator | Standardized Factor Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

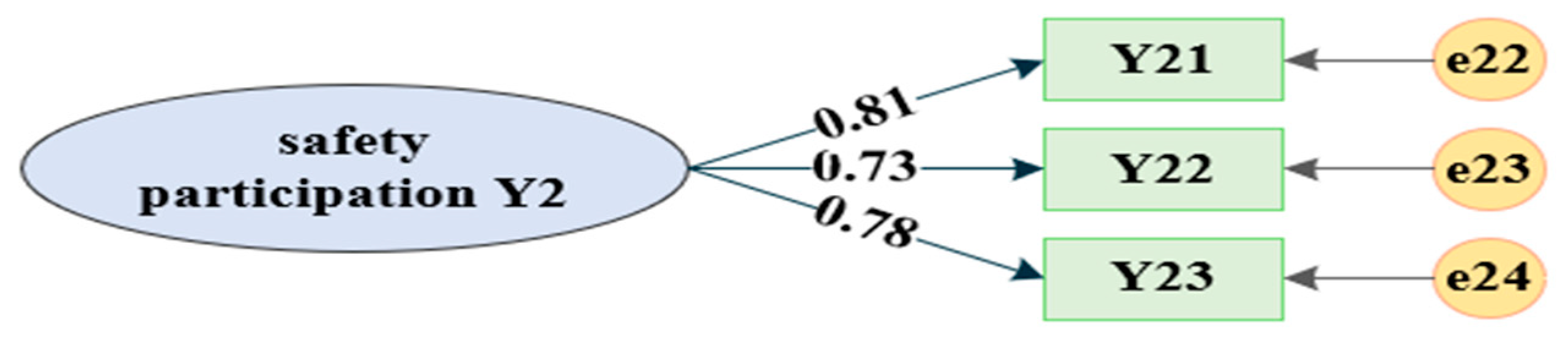

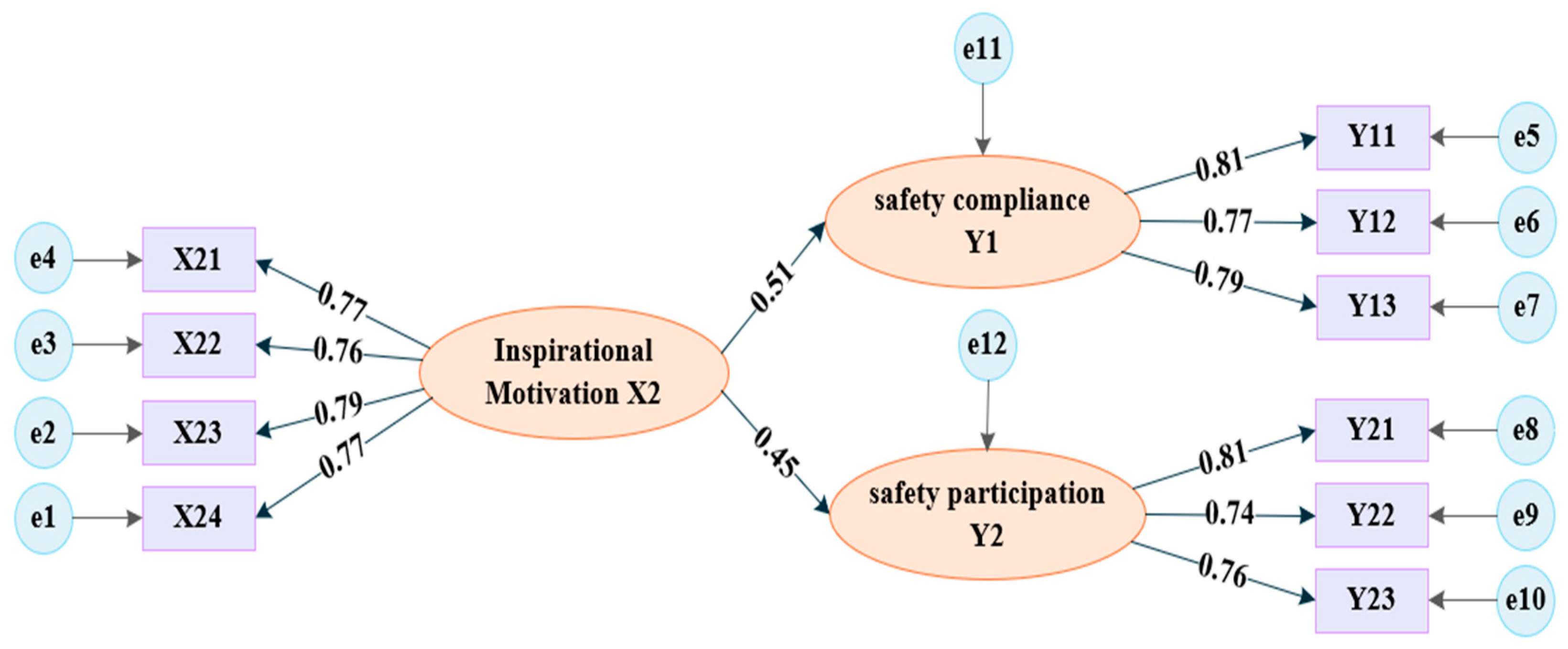

| Idealized Influence | X11 | 0.80 | 0.890 | 0.618 |

| X12 | 0.77 | |||

| X13 | 0.78 | |||

| X14 | 0.79 | |||

| X15 | 0.79 | |||

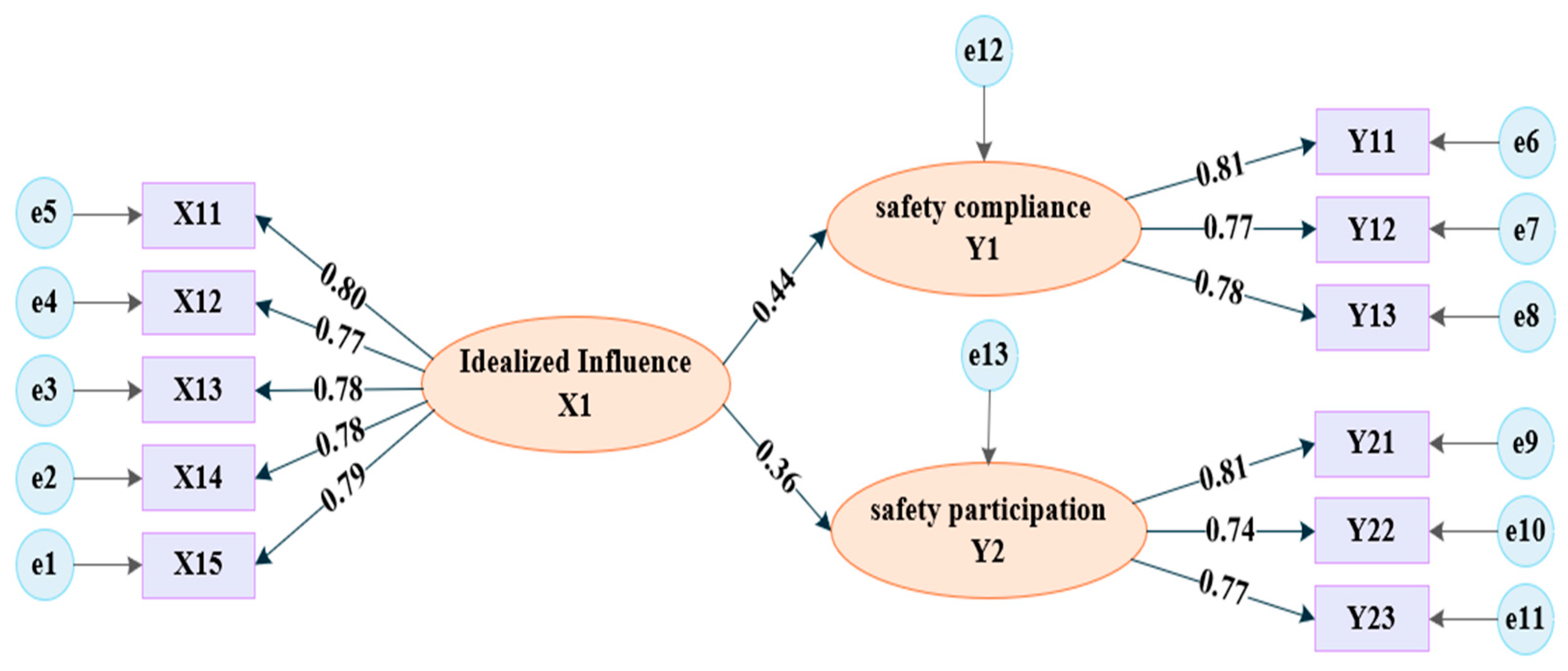

| Inspirational Motivation | X21 | 0.77 | 0.858 | 0.601 |

| X22 | 0.76 | |||

| X23 | 0.79 | |||

| X24 | 0.78 | |||

| Idealized Influence (charisma) | X31 | 0.73 | 0.862 | 0.609 |

| X32 | 0.79 | |||

| X33 | 0.79 | |||

| X34 | 0.81 | |||

| Individualized Consideration | X41 | 0.79 | 0.881 | 0.597 |

| X42 | 0.76 | |||

| X43 | 0.82 | |||

| X44 | 0.75 | |||

| X45 | 0.74 | |||

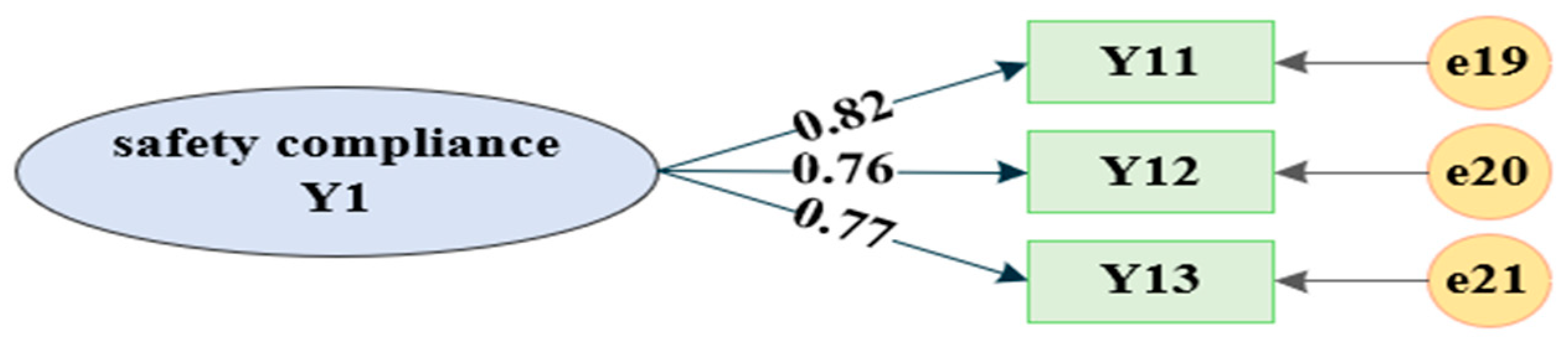

| Safety Compliance | Y11 | 0.82 | 0.827 | 0.614 |

| Y12 | 0.76 | |||

| Y13 | 0.77 | |||

| Safety Participation | Y21 | 0.81 | 0.817 | 0.599 |

| Y22 | 0.73 | |||

| Y23 | 0.78 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized Influence | 1.000 | |||||

| Inspirational Motivation | 0.533 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| Idealized Influence (charisma) | 0.524 ** | 0.530 ** | 1.000 | |||

| Individualized Consideration | 0.512 ** | 0.559 ** | 0.547 ** | 1.000 | ||

| Safety Compliance | 0.361 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.315 ** | 1.000 | |

| Safety Participation | 0.290 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.526 ** | 1.000 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized Influence | 0.618 | |||||

| Inspirational Motivation | 0.284 | 0.601 | ||||

| Idealized Influence (charisma) | 0.275 | 0.281 | 0.609 | |||

| Individualized Consideration | 0.262 | 0.312 | 0.299 | 0.597 | ||

| Safety Compliance | 0.130 | 0.164 | 0.104 | 0.099 | 0.614 | |

| Safety Participation | 0.084 | 0.118 | 0.077 | 0.079 | 0.277 | 0.599 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 3.074 | 3.629 | 4.058 | 3.653 | 1.054 |

| RMSEA | 0.072 | 0.075 | 0.078 | 0.074 | 0.012 |

| GFI | 0.949 | 0.947 | 0.943 | 0.940 | 0.949 |

| AGFI | 0.920 | 0.912 | 0.906 | 0.905 | 0.937 |

| IFI | 0.958 | 0.951 | 0.943 | 0.945 | 0.997 |

| CFI | 0.958 | 0.951 | 0.942 | 0.944 | 0.997 |

| NFI | 0.939 | 0.934 | 0.926 | 0.925 | 0.951 |

| Path | β | Standard Error | Critical Ratio | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized Influence → Safety Compliance Behavior | 0.438 | 0.062 | 7.445 | <0.001 |

| Idealized Influence → Safety Participation Behavior | 0.364 | 0.060 | 6.158 | <0.001 |

| Inspirational Motivation → Safety Compliance Behavior | 0.509 | 0.067 | 8.403 | <0.001 |

| Inspirational Motivation → Safety Participation Behavior | 0.446 | 0.064 | 7.345 | <0.001 |

| Idealized Influence (charisma) → Safety Compliance Behavior | 0.404 | 0.061 | 6.809 | <0.001 |

| Idealized Influence (charisma) → Safety Participation Behavior | 0.360 | 0.059 | 6.016 | <0.001 |

| Individualized Consideration → Safety Compliance Behavior | 0.389 | 0.069 | 6.526 | <0.001 |

| Individualized Consideration → Safety Participation Behavior | 0.351 | 0.067 | 5.855 | <0.001 |

| Transformational Leadership → Safety Behavior | 0.617 | 0.079 | 8.428 | <0.001 |

| Transformational Leadership Dimensions | Safety Compliance Behavior (β) | Safety Participation Behavior (β) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized Influence | 0.438 | 0.364 | +0.074 |

| Inspirational Motivation | 0.509 | 0.446 | +0.063 |

| Idealized Influence (charisma) | 0.404 | 0.360 | +0.044 |

| Individualized Consideration | 0.389 | 0.351 | +0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zeng, H.; Jiang, X.; Liang, Q.; Li, M.; Tian, Y. Impact of Transformational Leadership on New-Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Buildings 2026, 16, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020354

Zeng H, Jiang X, Liang Q, Li M, Tian Y. Impact of Transformational Leadership on New-Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020354

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Hui, Xianglong Jiang, Qiaoxin Liang, Minwei Li, and Yuanyuan Tian. 2026. "Impact of Transformational Leadership on New-Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach" Buildings 16, no. 2: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020354

APA StyleZeng, H., Jiang, X., Liang, Q., Li, M., & Tian, Y. (2026). Impact of Transformational Leadership on New-Generation Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Buildings, 16(2), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020354