How to Prevent Construction Safety Accidents? Exploring Critical Factors with Systems Thinking and Bayesian Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Focusing on fall from height, structural collapse, lifting injuries, and other construction safety accidents, the study constructs a Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model across six dimensions. 11The model establishes six hierarchical levels and twenty-three interrelated factors to represent the multi-level nature of accident causation.

- (2)

- It develops a BN-based quantitative framework that transforms the qualitative CACS structure into a probabilistic reasoning model. This enables diagnostic inference, sensitivity analysis, and the quantitative identification of key accident pathways based on 331 official construction accident reports.

- (3)

- It validates the proposed approach through real-world collapse case studies, demonstrating both its theoretical contribution to understanding causal mechanisms and its practical value for data-informed decision-making in construction safety management.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Construction Accident Causation

2.2. Critical Influencing Factors of Construction Safety

2.3. Safety Management and Monitoring Tools in Construction

3. Research Methodology

- Establishment of the CACS and AcciMap model. The Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model was developed using a systems-thinking approach, which regards construction safety accidents and their causal factors as an integrated system that can be decomposed into multiple hierarchical levels and interacting factors [41]. To construct this model, a comprehensive literature review was first conducted, identifying 23 key causal factors, which were categorized into six levels: Organizational and Behavioral (OB), Technical Management (TM), Resource Guarantee (RG), Contract Management (CM), Safety Training (ST), and Environmental Management (EM). These levels were adapted from Rasmussen’s risk management framework, tailored to the characteristics of the construction industry to comprehensively capture accident causation. To clearly depict the causal relationships among these factors, the study further developed an AcciMap model, graphically representing dynamic interactions within and across levels. Additionally, a team of 16 experts was assembled, and through multiple rounds of collaborative discussions, the causal relationships were validated and refined. The resulting AcciMap provides a qualitative systemic framework for understanding accident causation, laying a solid foundation for subsequent quantitative analysis using BN.

- Establishment of the BN model and BN analysis. The BN model builds upon the qualitative analysis of AcciMap, quantifying the relationships between causal factors within a probabilistic framework by converting the factors and their interactions described in AcciMap into nodes and arcs [40]. Following frequency statistics of construction accident investigation reports and expert discussions, two low-frequency factors were excluded, resulting in the construction of a network comprising 22 nodes (21 CACS factors plus one accident node). The expert-validated causal relationships from AcciMap were integrated, and the network structure was further refined using the Greedy Thick Thinning algorithm and empirical data-driven adjustments in GeNIe 2.3 (BayesFusion, LLC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) software, ensuring alignment with both expert knowledge and real-world data characteristics. Next, the Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm was employed to generate Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs) from the accident report data, precisely capturing probabilistic dependencies between nodes. BN analysis was conducted in two parts: diagnostic reasoning to trace critical pathways leading to accidents, and sensitivity analysis to identify key influencing factors. This approach not only enhances the model’s inferential capabilities but also reduces reliance on subjective judgment by grounding the analysis in empirical data, thereby improving objectivity and credibility.

- Case study of a collapse accident. Case studies are an effective method for validating research findings [42]. To assess the practical utility of the CACS model and the key factors identified by the BN approach, this study selected the Hengshui City construction hoist cage collapse accident as a case study. By analyzing the accident process and official investigation findings, the causes were extracted and compared with the research results, validating the BN model’s applicability and demonstrating its ability to derive critical insights for improving construction safety management.

4. Establishment of the CACS and AcciMap Model

4.1. Structure of the CACS Model

4.2. Correlations Among Causal Factors and AcciMap Model

5. Network Model of Construction Safety Accidents

5.1. Data Collection

5.2. Establishment of Bayesian Network Model

- (1)

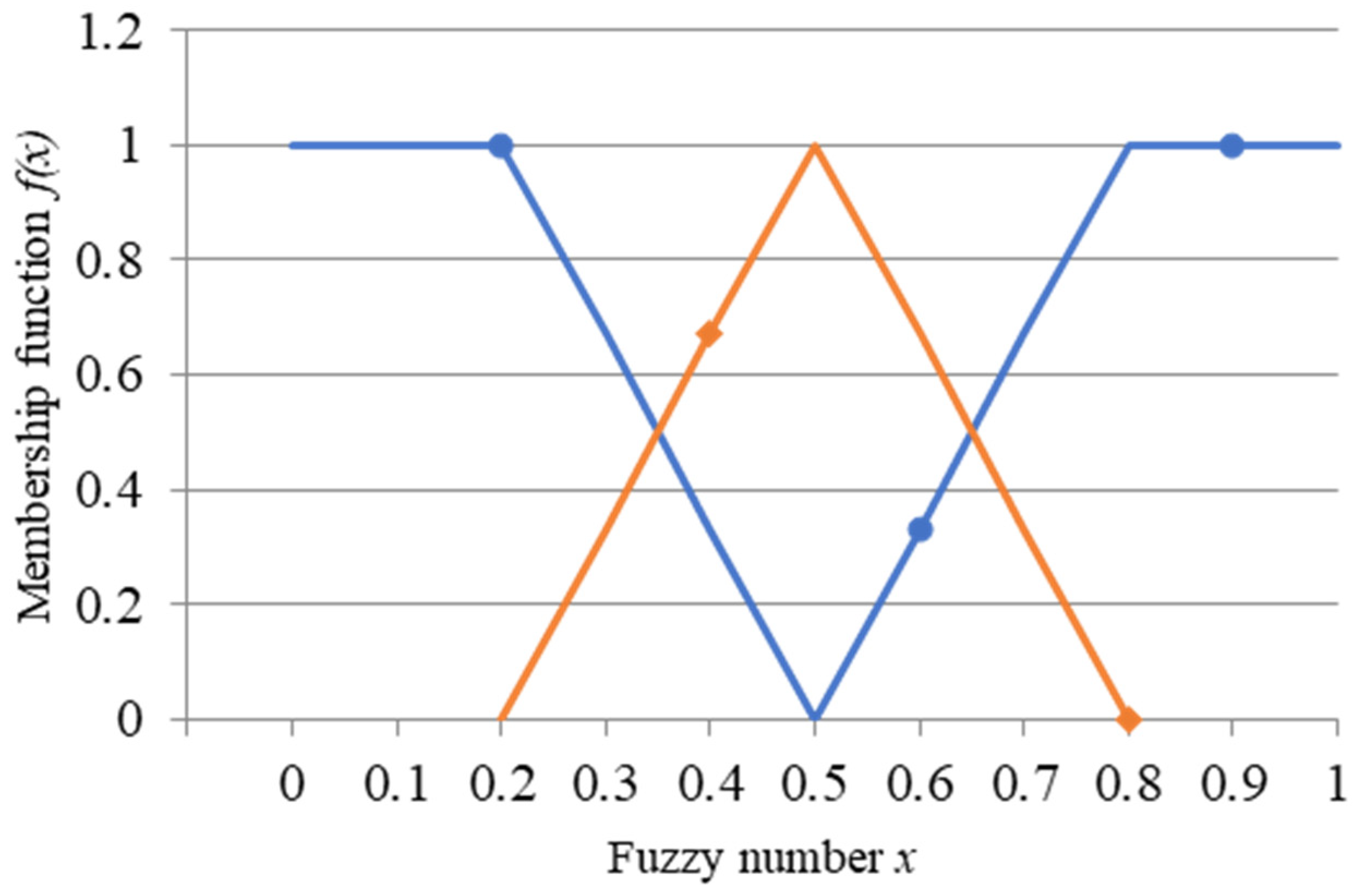

- Suppose that Xmis is a variable with a missing value in an incomplete dataset D. Let Xmis = xmis, such that we can obtain a complete dataset by adding xmis to D. During the process, Xmis may have more assignments; that is, the EM algorithm assigns a weight Wxmis for each possible result. The weighted sample is then given by the following:where . The weight ranges from 0 to 1. During the process of data supplement, each incomplete sample is replaced by a complete weighted sample.

- (2)

- For the complete sample obtained in step (1), the maximum likelihood is calculated by estimating θt + 1 using Equation (2).

5.3. Diagnostic Reasoning

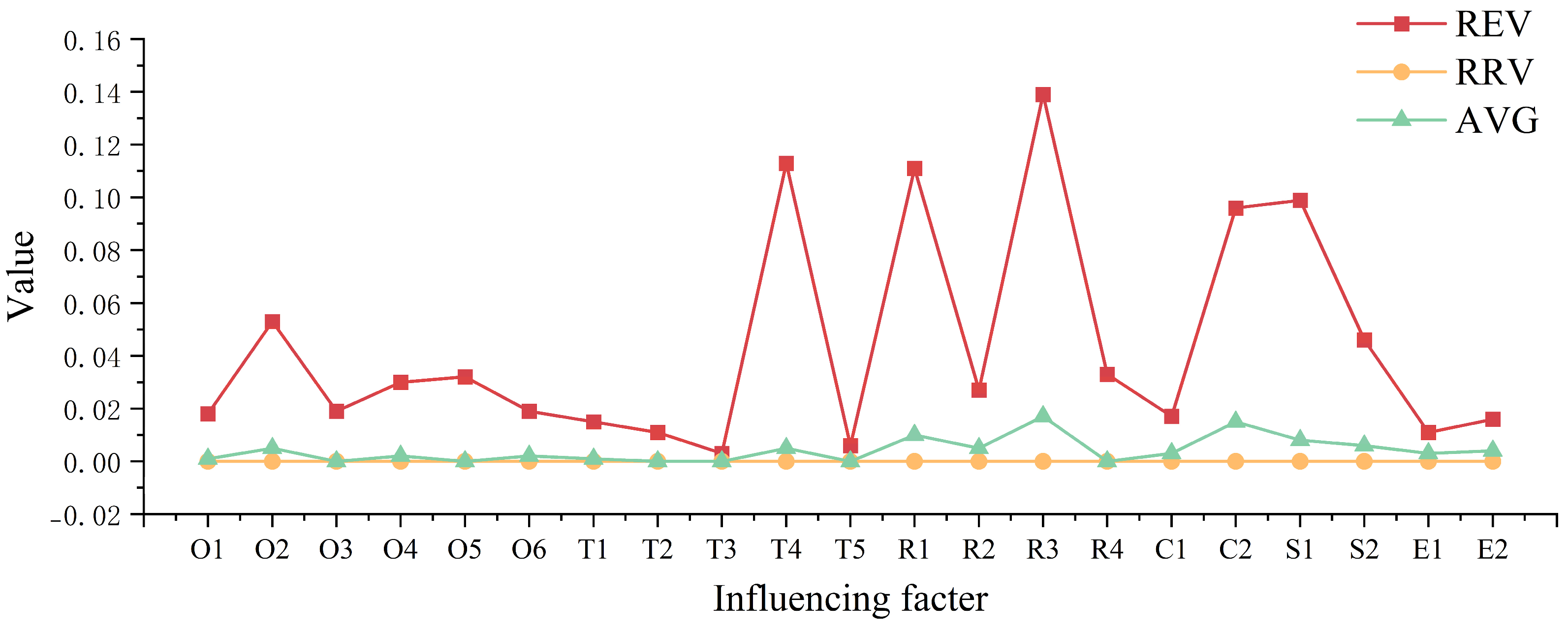

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis

5.5. Major Results

- (1)

- Factor analysis

- Critical factors. According to the diagnostic reasoning, the factors on the most probable path include C2, O2, S2, S1, O3, R3, and O5. Therefore, the seven critical factors of construction safety accidents are identified as: O2 (Incomplete safety management system), O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work), O5 (Workers’ wrong actions), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge), and S2 (Inadequate safety training). These factors should be given priority in safety management practice.

- Sensitivity factors. Through sensitivity analysis, three sensitive factors are determined as R1 (Failure of mechanical equipment), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), and C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor). Among them, C2 and R3 are not only critical factors but also sensitive factors. These factors should also be highly valued and strictly controlled.

- General factors. In addition to the critical factors and sensitive factors, the other 13 factors are called general factors. The control effect of these factors is better and should be maintained.

- (2)

- Path analysis.

6. Case Study

6.1. Accident Occurrence and Investigation Process

- Poor quality of steel pipes and couplers: Third-party on-site sampling and testing confirmed that the steel pipes and couplers used in the high formwork system did not meet national standards. This serious non-compliance severely weakened the formwork support’s load-bearing capacity and reduced its overall rigidity, jeopardizing its stability.

- Corrosion and structural damage to steel pipes and couplers: The site inspection revealed significant corrosion, cracks, and visible dents in the steel pipes, as well as old cracks in the couplers, as shown in Figure 11b,c.

- Improper scaffolding installation. The high formwork system on the constraint platform had completely collapsed, and the scaffolding on the first, second, and third levels had deformed and was missing, as shown in Figure 11d. The horizontal braces were not installed as per regulations, and the wall ties were missing.

- Non-compliant concrete pouring sequence and method: The construction unit used an incorrect, layer-by-layer pouring method from west to east for the concrete on axes ② and ④. This practice deviated from the prescribed method of symmetrical pouring from the center of the span to the ends, resulting in uneven load distribution on the large formwork system. The inspection revealed that while the cantilever beam at axis ④ had been poured to the top elevation, there were pouring marks at the east end of the cantilever beam at axis ②, with minimal concrete poured at the beam root over the 5–6 m section, as shown in Figure 11e.

6.2. Identification of Accident Causes

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- A Construction Accident Causation System (CACS) model was established based on systems thinking. Construction safety accident causes were considered as a social and technological system comprising six layers: organization and behavior, technology management, resource guarantee, contract management, safety training, and environmental management. These layers were further decomposed into 23 factors related to safety management.

- (2)

- A sample of 331 construction safety accidents was collected, and their investigation reports were analyzed. The basic mechanism of construction safety accidents was identified, including the accident types and severity levels. More importantly, the correlations among the 23 factors were identified, and an AcciMap for construction safety accidents was established, which provided a basis for the BN analyses.

- (3)

- A BN diagram was obtained from the AcciMap. The most probable path and the critical factors were determined based on diagnostic reasoning, including O2 (Incomplete safety management system), O3 (Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work), O5 (Workers’ wrong actions), R3 (Inadequate distribution and use of PPE), C2 (Unqualified or incompetent contractor), S1 (Lacking safety awareness and knowledge), and S2 (Inadequate safety training). These results can provide a robust basis for safety management and accident prevention.

- (4)

- A typical construction accident was selected to conduct a case study. Based on the analysis of the accident occurrence process and official investigation results, the accident causes and corresponding distribution were identified using the CACS model. The results showed strong consistency with the BN analysis of 331 accidents, showing that the CACS model and factor classification are reasonable and practical.

- (5)

- Finally, it is recommended that all relevant participants and practitioners enhance their safety awareness and knowledge levels, regulate their behavior at work, and attempt to discover and eliminate on-site hazards to create a stable working environment, reduce safety risk, and finally prevent the occurrence of construction safety accidents.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Case Verification

Appendix A.1. “5·6” Major Hoisting Injury Accident at Plot N1–01, Yangpu Riverside, Shanghai

| Level | Accident Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Critical | Incomplete safety management system (O2) | The tower crane installation/dismantling unit lacked safety systems, failed to clarify on-site supervision responsibilities of deputy team leaders and assistants, and had no regulations for safety belt supervision in high-altitude operations or bolt removal sequence control. |

| Workers’ wrong actions (O5) | Workers operated in violation of rules: removed balance arm bolts before finishing counterweight removal; three high-altitude workers failed to fasten safety belts, causing falling casualties. | |

| Unqualified or incompetent contractor (C2) | The unit conducted unlicensed hoisting commands with chaotic work assignments; the project manager failed to identify hazards, such as illegal dismantling and unfastened safety belts. | |

| Lacking safety awareness and knowledge (S1) | Workers had weak safety awareness, lacked knowledge of balance arm structural risks, and ignored safety belt fastening requirements for high-altitude operations. | |

| Inadequate safety training (S2) | The unit did not conduct special safety training or pre-job briefing, leading to workers’ lack of standardized operation awareness. | |

| Sensitive | Inadequate distribution and use of PPE (R3) | Though safety belts were available on-site, their proper use was unsupervised; PPE failed to function, resulting in fatal falls. |

| General | Inadequate safety supervision (O6) | The general contractor’s safety officer did not supervise the entire tower crane dismantling process or stop violations, leaving on-site supervision absent. |

| Unqualified or unskillful workers (O4) | Unlicensed personnel commanded hoisting; some installers/dismantlers were unskilled, causing structural instability via violations. |

Appendix A.2. “11·11” General High-Altitude Fall Accident at a Self-Built Housing Site, Wenchang, Hainan

| Level | Accident Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Critical | Incomplete safety management system (O2) | The self-built housing construction company did not establish a complete high-altitude operation safety management system, with no clear regulations on the configuration of on-site fall protection facilities and the supervision of PPE use. |

| Workers’ wrong actions (O5) | The worker Liu did not fasten his safety belt when working on the fifth floor. He acted carelessly during the operation and accidentally fell from a high place, which was the direct cause of the accident. | |

| Lacking safety awareness and knowledge (S1) | The on-site construction workers had weak safety awareness, did not recognize the serious consequences of high-altitude operations without wearing safety belts, and lacked basic risk prevention awareness in construction operations. | |

| Inadequate safety training (S2) | The construction company did not organize targeted safety training for high-altitude operation personnel. It failed to conduct pre-job safety disclosure on fall protection knowledge and standard operating procedures, resulting in the workers’ lack of necessary safety operation knowledge. | |

| Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work (O3) | The construction company did not arrange full-time and qualified safety engineers to be on-site. No one supervised the workers’ operation process, and violations such as not wearing safety belts were not stopped in time. | |

| Sensitive | Inadequate distribution and use of PPE (R3) | The construction company did not urge workers to standardize the use of safety belts. The workers did not use the necessary personal protective equipment during high-altitude operations, which directly led to the death of the worker after falling. |

| General | Inadequate on-site safety protection (R4) | The construction site did not install anti-fall nets as required for high-altitude operations. The temporary safety protection facilities were missing, which failed to form a secondary protection for workers in high-altitude operations. |

| Inadequate safety supervision (O6) | The relevant regulatory departments did not conduct strict supervision and inspection on the safety of self-built housing construction. They failed to find and urge the rectification of problems such as the lack of protective facilities and inadequate training at the construction site in a timely manner. |

References

- Perttula, P.; Korhonen, P.; Lehtelä, J.; Rasa, P.-L.; Kitinoja, J.-P.; Mäkimattila, S.; Leskinen, T. Improving the Safety and Efficiency of Materials Transfer at a Construction Site by Using an Elevator. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2006, 132, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Nunes, I.L.; Ribeiro, R.A. Occupational Risk Assessment in Construction Industry—Overview and Reflection. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Zou, P.X.W. Political Skill for Developing Construction Safety Climate. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China. The Situation of National Production Safety and Natural Disasters in the First Three Quarters of 2024. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/xwfbh/2024n10y22xwfbh/?menuid=104 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of China. Bulletin on the Safety Accidents of Housing Municipal Engineering. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hubei Provincial Emergency Management Department. Accident and Disaster Statistics for January-December 2024. Available online: https://yjt.hubei.gov.cn/fbjd/xxgkml/sjfb/aqscsgkb/202502/t20250207_5532438.shtml (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Mitropoulos, P.; Abdelhamid, T.S.; Howell, G.A. Systems Model of Construction Accident Causation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Tang, J. Tower Crane Safety on Construction Sites: A Complex Sociotechnical System Perspective. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, V.; Burkova, I.; Barkhi, R.; Berlinov, M. Qualitative Risk Assessments in Project Management in Construction Industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 251, 06027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Wei, J.; Ting, H.-I.; Lo, T.-P.; Long, D.; Chang, L.-M. Dynamic Analysis of Construction Safety Risk and Visual Tracking of Key Factors Based on Behavior-Based Safety and Building Information Modeling. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4155–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, K.A.; Gambatese, J.A.; Tymvios, N. Risk Perception Comparison among Construction Safety Professionals: Delphi Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlolu, M.; Haupt, T.C.; Edwards, D.J.; Simpeh, F. A Bibliometric Review of the Status and Emerging Research Trends in Construction Safety Management Technologies. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2699–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; Bapat, H.; Patel, D.; van der Walt, J.D. Identification of Critical Success Factors (CSFs) of BIM Software Selection: A Combined Approach of FCM and Fuzzy DEMATEL. Buildings 2021, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Khan, F.; Abbassi, R.; Rusli, R. Improved DEMATEL Methodology for Effective Safety Management Decision-Making. Saf. Sci. 2020, 127, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Li, M.; Jin, Z.; Huang, J. Unveiling Construction Accident Causation: A Scientometric Analysis and Qualitative Review of Research Trends. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1602297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaa, E.; Shirzadi Javid, A.A.; Malekitabar, H. Evolution of Risk Analysis Approaches in Construction Disasters: A Systematic Review of Construction Accidents from 2010 to 2025. Buildings 2025, 15, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedung, I.; Rasmussen, J. Graphic Representation of Accidentscenarios: Mapping System Structure and the Causation of Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2002, 40, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.H.; Sun, C.; Xia, B.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Way, K.A.; Wu, P.P.-Y. Applications of Bayesian Approaches in Construction Management Research: A Systematic Review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 2153–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.M.; Lenné, M.G. Miles Away or Just around the Corner? Systems Thinking in Road Safety Research and Practice. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 74, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk Management in a Dynamic Society: A Modelling Problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, R.; Ward, N.J. A Systems Analysis of the Ladbroke Grove Rail Crash. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005, 37, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A New Accident Model for Engineering Safer Systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Pardo-Ferreira, M.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Gibb, A.; Calero-Castro, S. Using Functional Resonance Analysis Method to Understand Construction Activities for Concrete Structures. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R.L.; Mugi, S.R.; Saleh, J.H. Accident Investigation and Lessons Not Learned: AcciMap Analysis of Successive Tailings Dam Collapses in Brazil. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 236, 109308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjia, Y.; Alias, A.H.; Haron, N.A.; Abu Bakar, N. Identification and Analysis of Hoisting Safety Risk Factors for IBS Construction Based on the AcciMap and Cases study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, J.; Pedersen, C.; Fredley, J. Identifying Root Causes of Construction Injuries. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1998, 124, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, R.M.; Fang, D. Why Operatives Engage in Unsafe Work Behavior: Investigating Factors on Construction Sites. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoła, B.; Szóstak, M. An Occupational Profile of People Injured in Accidents at Work in the Polish Construction Industry. Procedia Eng. 2017, 208, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J. Impact of Construction Safety Culture and Construction Safety Climate on Safety Behavior and Safety Motivation. Safety 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, E.; Usmen, M.A. Worker Safety and Injury Severity Analysis of Earthmoving Equipment Accidents. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 65, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanni-Anibire, M.O.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Salami, B.A. A Risk Assessment Approach for Enhancing Construction Safety Performance. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, M.; Nielsen, K. Promoting and Impeding Safety—A Qualitative Study into Direct and Indirect Safety Leadership Practices of Constructions Site Managers. Saf. Sci. 2019, 114, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A. Construction Safety Culture & Climate: The Relative Importance of Contributing Factors. Prof. Saf. 2022, 67, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Larsman, P.; Ulfdotter Samuelsson, A.; Räisänen, C.; Rapp Ricciardi, M.; Grill, M. Role Modeling of Safety-Leadership Behaviors in the Construction Industry: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study. Work 2024, 77, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Mora-Serrano, J.; Oñate, E. Factors Influencing Safety on Construction Projects (fSCPs): Types and Categories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yin, L.; Deng, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, C. Using Cased Based Reasoning for Automated Safety Risk Management in Construction Industry. Saf. Sci. 2023, 163, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skład, A. Assessing the Impact of Processes on the Occupational Safety and Health Management System’s Effectiveness Using the Fuzzy Cognitive Maps Approach. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S.M.; Tamošaitienė, J. An Integrated Fuzzy DEMATEL-Fuzzy ANP Model for Evaluating Construction Projects by Considering Interrelationships among Risk Factors. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 25, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.E.; Rivas, T.; Matías, J.M.; Taboada, J.; Argüelles, A. A Bayesian Network Analysis of Workplace Accidents Caused by Falls from a Height. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Chen, C. Fuzzy Comprehensive Bayesian Network-Based Safety Risk Assessment for Metro Construction Projects. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 70, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X.; Zhao, T. Reliability Model and Critical Factors Identification of Construction Safety Management Based on System Thinking. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2019, 25, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Han, S. Analyses of Systems Theory for Construction Accident Prevention with Specific Reference to OSHA Accident Reports. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.-W.; Lin, K.-Y.; Hsieh, S.-H. Using Ontology-Based Text Classification to Assist Job Hazard Analysis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2014, 28, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaosheng, Y.; Xiuyun, L. Importance Evaluation of Construction Collapse Influencing Factors Based on Grey Correlation Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering, Sanya, China, 20–21 October 2012; Volume 3, pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.H.W.; Yiu, T.W.; González, V.A. Predicting Safety Behavior in the Construction Industry: Development and Test of an Integrative Model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Fung, I.W.H. Tower Crane Safety in the Construction Industry: A Hong Kong Study. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Pei, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y. Analysis for Yangmingtan Bridge Collapse. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 56, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.J. Factors That Affect Safety of Tower Crane Installation/Dismantling in Construction Industry. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Qian, Y. Analysis of Factors That Influence Hazardous Material Transportation Accidents Based on Bayesian Networks: A Case Study in China. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisz, I. Project Risk Assessment Using Fuzzy Inference System. Logist. Transp. 2011, 2, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R.R.; Cardoso, I.M.G.; Barbosa, J.L.V.; da Costa, C.A.; Prado, M.P. An Intelligent Model for Logistics Management Based on Geofencing Algorithms and RFID Technology. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 6082–6097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Goerlandt, F.; Banda, O.A.V.; Kujala, P. Developing Fuzzy Logic Strength of Evidence Index and Application in Bayesian Networks for System Risk Management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 192, 116374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Hwang, C.-L. Fuzzy Multiple Attribute Decision Making Methods. In Fuzzy Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; Volume 375, pp. 289–486. ISBN 978-3-540-54998-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Impact of Owners’ Safety Management Behavior on Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior. Saf. Sci. 2023, 158, 105944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; He, Y.; Li, Z. Study on Influencing Factors of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior Based on Text Mining. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 886390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Ye, G.; Liu, Y.; Miang Goh, Y.; Wang, D.; He, T. Cognitive Mechanism of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior: A Systematic Review. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, J.; Xiang, Y.; Li, C.; Hu, F. Safety Risk Management in China’s Power Engineering Construction: Insights and Countermeasures from the 14th Five-Year Plan. Processes 2025, 13, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, N.; Ji, M.; Wang, X. Digital Twin in Construction Safety Management: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions from 4M1E Perspective. Saf. Sci. 2025, 192, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Ma, S. Data-Driven Dynamic Bayesian Network Model for Safety Resilience Evaluation of Prefabricated Building Construction. Buildings 2024, 14, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Data Used | Model Construction Method | Accident Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martín et al. [39] | Falls-from-height accident data | BN with researcher-defined structure | Workplace falls from height | Modeled causal links in fall accidents and identified influential factors. |

| Wang and Chen [40] | Metro construction safety data | Fuzzy evaluation + BN | Metro construction risk | Enabled uncertainty-based risk assessment for metro projects. |

| Skład [37] | OSH process data + expert input | Fuzzy Cognitive Maps | OSH management system | Mapped interactions among management processes affecting OSH performance. |

| Hatefi and Tamošaitienė [38] | Expert judgments + project data | Fuzzy DEMATEL + ANP | Construction project risk | Identified and prioritized interrelated project risk factors. |

| Svedung and Rasmussen [17] | Accident reports + system descriptions | System-theoretic hierarchical mapping | Complex socio-technical accidents | Represented multi-level system causes using AcciMap. |

| This study | 331 official investigation reports | CACS/AcciMap-informed BN with EM | Building and municipal construction accidents | Integrates system causation modeling with probabilistic BN reasoning. |

| Layer | Accident Causing Subfactors |

|---|---|

| Organization and behavior (OB) | O1 Unreasonable safety management organization |

| O2 Incomplete safety management system | |

| O3 Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work | |

| O4 Unqualified or unskillful workers | |

| O5 Workers’ wrong actions | |

| O6 Inadequate safety supervision | |

| Technology management (TM) | T1 Incomplete construction plan |

| T2 Inadequate safety technical disclosure | |

| T3 Inadequate safety inspection | |

| T4 Improper installation of temporary facilities | |

| T5 Delayed hazard elimination | |

| T6 Lack of pre-shift safety meetings | |

| Resource Guarantee (RG) | R1 Failure of mechanical equipment |

| R2 Low-quality construction materials | |

| R3 Inadequate distribution and use of PPE | |

| R4 Inadequate on-site safety protection | |

| R5 Insufficient safety warning signs | |

| Contract management (CM) | C1 Schedule pressure |

| C2 Unqualified or incompetent contractor | |

| Safety Training (ST) | S1 Lacking safety awareness and knowledge |

| S2 Inadequate safety training | |

| Environmental management (EM) | E1 Rigorous climate condition |

| E2 Complex geological condition |

| Category | Type of Work Unit | Job Title | Work Experience (n) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | University | 3 | Senior | 5 | 5 < n < 10 | 3 |

| Construction company | 11 | Deputy senior | 7 | 10 < n < 20 | 6 | |

| Safety supervision station | 2 | Intermediate | 4 | n > 20 | 7 | |

| Node | Judgement Standard | States |

|---|---|---|

| O1; O2; O3; O4; O5; O6; T1; T2; T3; T4; T5; R1; R2; R3; R4; C1; C2; S1; S2; E1; E2 | The degree of each causal factor contributing to construction accidents | “Low” means a causal factor does not exist or has little influence on an accident; “Medium” means a causal factor has an actual but not strong influence on an accident; “High” means a causal factor has a strong or critical impact on an accident |

| Accident | The main types of construction safety accidents | Fall from height; Collapse; Lifting injury; Other accidents |

| Analysis Process | Factors or Path | |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic reasoning | Critical factors | C2, O2, S2, S1, O3, R3, O5 |

| Sensitivity analysis | Sensitive factors | R1, R3, C2 |

| The most probable path |

| |

| Level | Accident Cause | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Critical | Incomplete safety management system (O2) | The construction unit failed to establish comprehensive safety regulations, including a hazard identification system, a safety responsibility system, a safety education and training system, and an emergency rescue plan for accidents. |

| Inadequate safety engineers or inefficient work (O3) | The construction unit failed to assign qualified safety engineers and supervisors and did not provide dedicated on-site safety management during scaffolding installation. | |

| Workers’ wrong actions (O5) | Workers relied on experience, performed non-standard operations, and failed to follow proper scaffolding and concrete pouring procedures. | |

| Unqualified or incompetent contractor (C2) | The construction unit illegally initiated construction without the project owner obtaining the necessary construction permit. | |

| Lacking safety awareness and knowledge (S1) | Workers lacked essential safety training and awareness, did not receive pre-task briefings, and were not provided with necessary safety education. | |

| Inadequate safety training (S2) | The project owner failed to establish a safety education and training system, did not organize necessary safety training for workers, and neglected to provide pre-task safety briefings. | |

| Sensitive | Unqualified or incompetent contractor (C2) | The construction unit illegally initiated construction without the project owner obtaining the necessary construction permit. |

| General | Unreasonable safety management organization (O1) | The construction unit did not establish a proper safety management organization, with the legal representative acting as a part-time safety officer and often being absent. |

| Unqualified or unskillful workers (O4) | Workers without valid certificates for special operations were assigned tasks like scaffolding. | |

| Incomplete construction plan (T1) | The construction unit used unapproved construction drawings and failed to prepare and approve a specific scaffolding plan. The project owner did not provide valid construction drawings, and the equipment supplier, lacking design qualifications, supplied drawings without detailed engineering surveys. | |

| Inadequate safety technical disclosure (T2) | The construction unit failed to provide workers with the necessary technical instructions before operations. | |

| Inadequate safety inspection (T3) | The construction unit failed to conduct required regular and specialized safety inspections. The project owner did not assign personnel to inspect the worksite and address unsafe practices. | |

| Improper installation of temporary facilities (T4) | The construction unit violated regulations during scaffolding installation by not installing horizontal braces as required. The U-shaped supports had eccentric loading, and the formwork support lacked rigidity, leading to structural deformation and collapse. | |

| Low-quality construction materials (R2) | The construction unit used construction materials such as steel pipes, couplers, and U-shaped supports that did not meet required standards, resulting in insufficient rigidity of the formwork support and an inability to meet the load-bearing capacity requirements. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Xue, N.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, T. How to Prevent Construction Safety Accidents? Exploring Critical Factors with Systems Thinking and Bayesian Networks. Buildings 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010039

Zhang W, Xue N, Cao Y, Zhao T. How to Prevent Construction Safety Accidents? Exploring Critical Factors with Systems Thinking and Bayesian Networks. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wei, Nannan Xue, Yidan Cao, and Tingsheng Zhao. 2026. "How to Prevent Construction Safety Accidents? Exploring Critical Factors with Systems Thinking and Bayesian Networks" Buildings 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010039

APA StyleZhang, W., Xue, N., Cao, Y., & Zhao, T. (2026). How to Prevent Construction Safety Accidents? Exploring Critical Factors with Systems Thinking and Bayesian Networks. Buildings, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010039