4.1. Development of Ground Settlement over Time

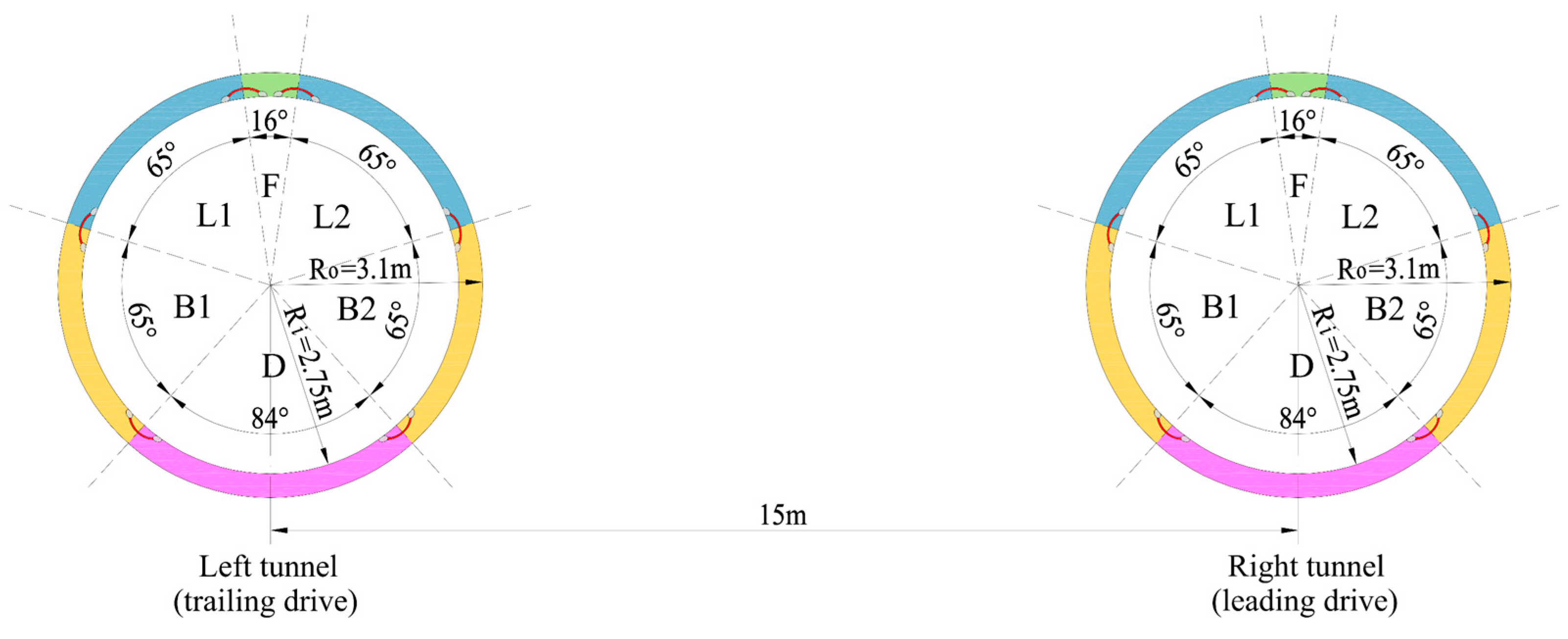

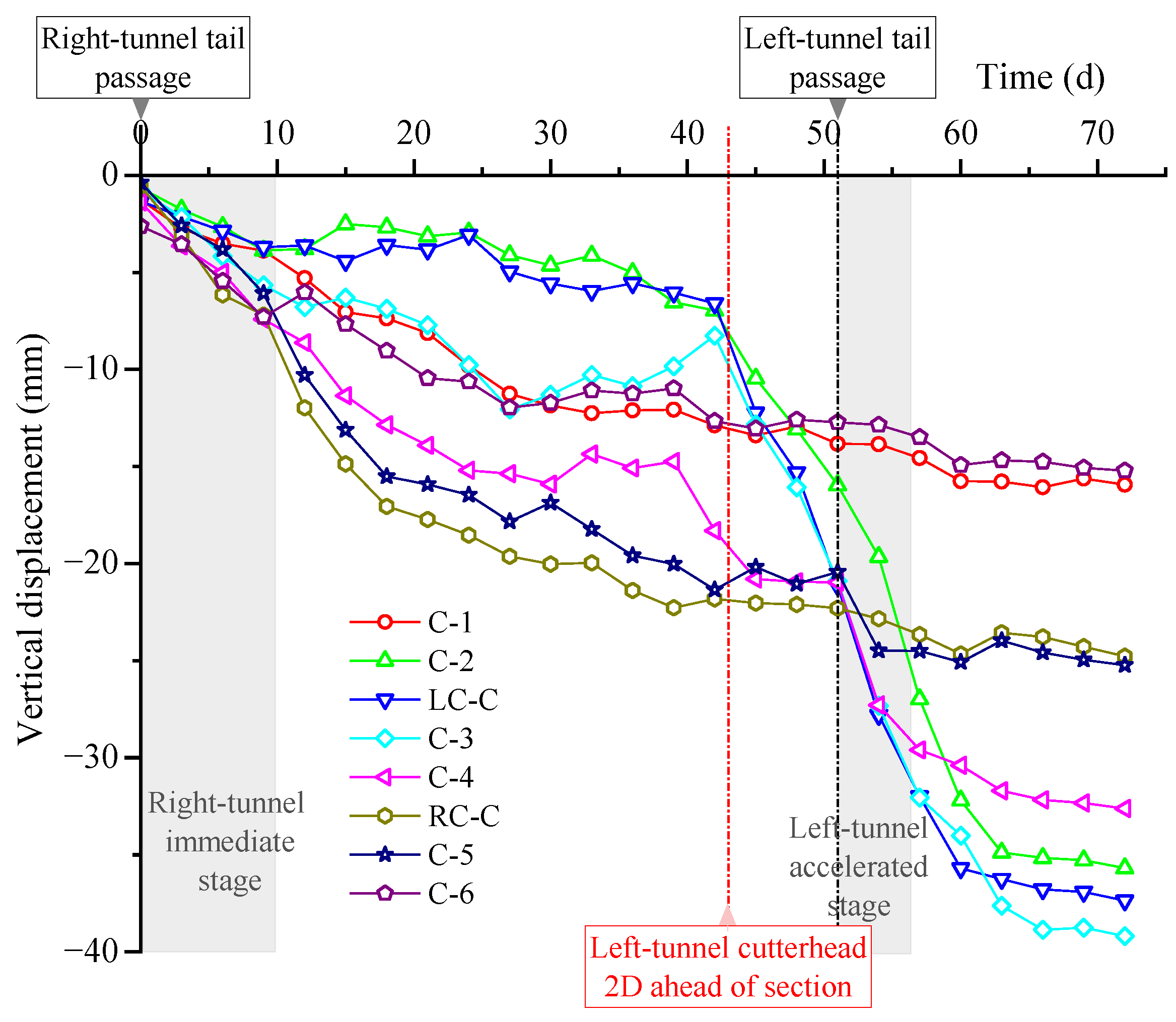

Figure 4,

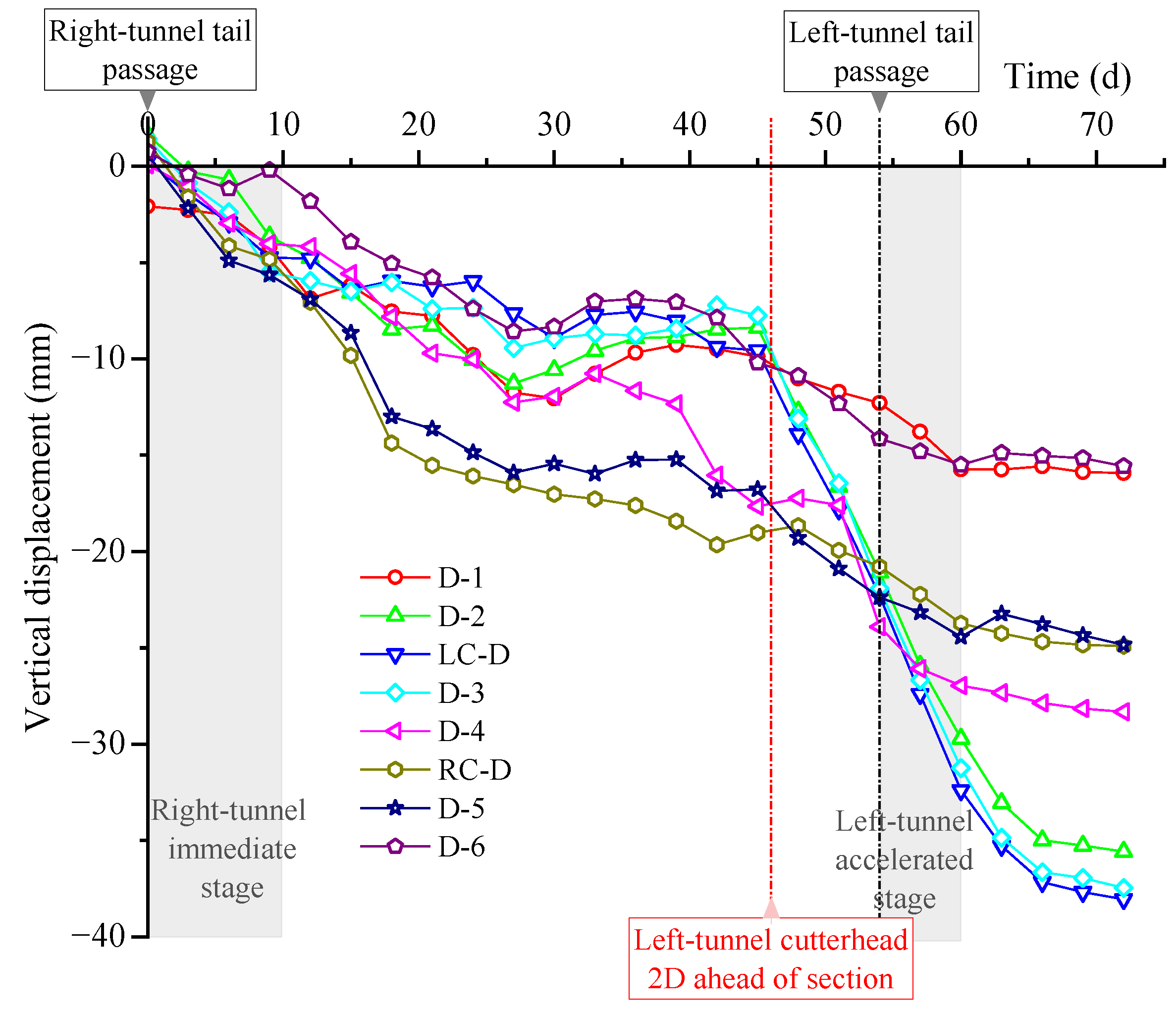

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the time-history curves of surface settlement at monitoring points in Sections A–D. Because the sections exhibit broadly similar patterns, Section A is discussed in detail as representative, with particular attention to how the time-dependent settlement process corresponds to variations in shield energy consumption and construction-phase efficiency.

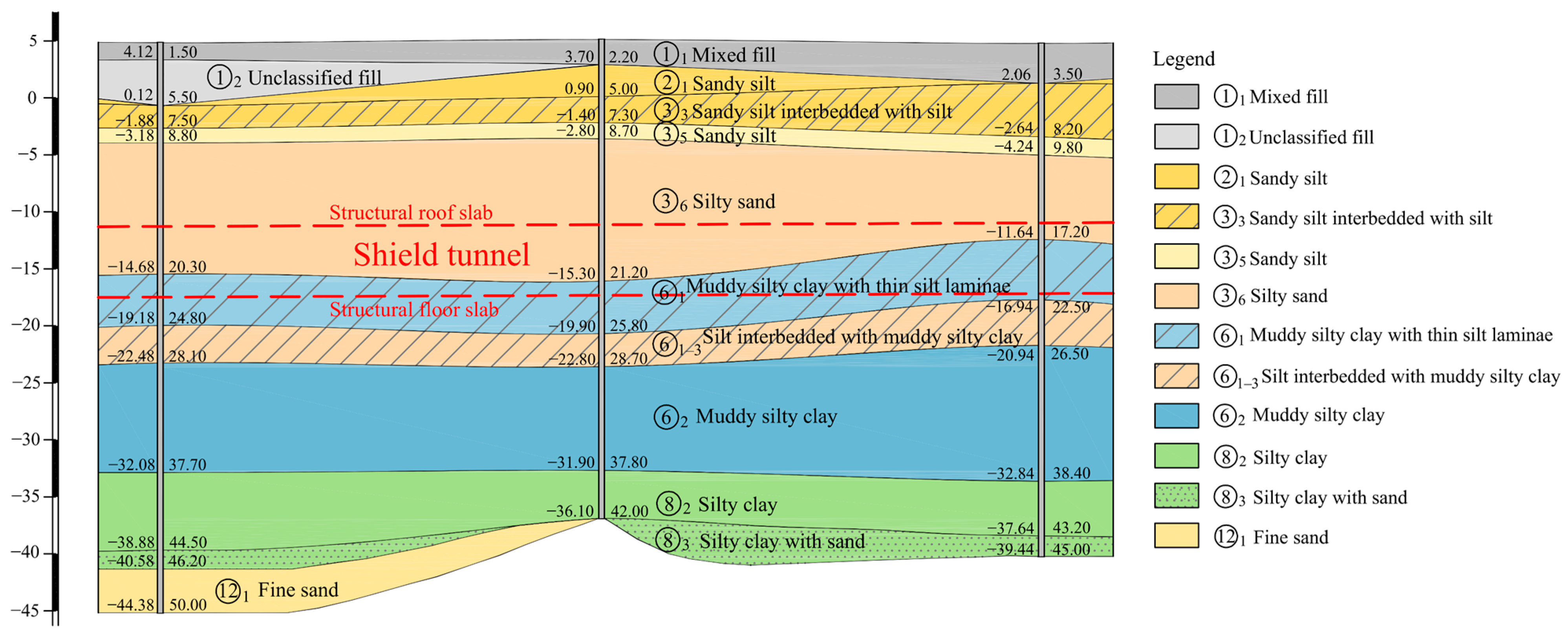

The time-dependent development of surface settlement at each monitoring point in Section A is shown in

Figure 4, capturing the characteristic response of soft clay under sequential twin-shield excavation. After the right shield advanced first, settlement at the tunnel centerline (RC-A) and adjacent points (A-4, A-5) increased rapidly; in contrast, points farther from the right tunnel centerline (A-1, A-2, LC-A, A-3) exhibited smaller magnitudes, with a few showing slight early heave (A-6). This contrast reflects the spatially non-uniform disturbance induced by the leading excavation and the formation of a pre-disturbed zone that governs the response to the trailing excavation.

For quantitative analysis of the spatial attenuation and post-construction development following the construction-induced immediate settlement, the moment when the right shield tail passed the section was defined as t = 0. Settlement readings at t = 10 d and t = 40 d were selected to calculate the incremental settlement Δt10d–40d, representing the consolidation-controlled settlement stage unaffected by the subsequent excavation of the left tunnel. Taking the right tunnel axis (yR) as the transverse reference coordinate, the zone within approximately one settlement-trough width on each side of the axis (W is typically ≈ 6–8 m) was defined as the primary disturbance zone. Within this zone, the mean incremental settlement was −14.37 mm, about 1.9 times the mean −7.44 mm outside the zone, indicating pronounced transverse attenuation of disturbance. Even after t > 10 d, settlement continued to develop slowly under consolidation and time-dependent effects. From an energy-efficiency perspective, the larger deformation magnitude near the tunnel axis implies higher shield energy input and material intensity, marking these zones as mechanically and environmentally critical.

Under soft-clay–EPB conditions, the settlement–time curve shows two segments: rapid early development followed by slow progression. Based on extensive field measurements from the Taipei Metro, Hwang and Moh [

31] employed logarithmic and hyperbolic models to extrapolate long-term settlement trends, dividing the process into an immediate settlement phase and a subsequent consolidation phase. Deng et al. [

32] reported, for a Suzhou Metro case, that most monitoring points stabilized at

t ≈ 10 d after tail passage and then entered a consolidation-dominated stage. Hence, this study adopts 8–10 days after shield passage as the empirical boundary between these phases, verified by the first inflection of the settlement-rate curve. From an energy and environmental perspective, this temporal evolution mirrors the changing intensity of shield operation and its carbon output. During the rapid-settlement phase, high thrust, torque, and grouting frequency drive deformation rates and electricity consumption, representing the most carbon-intensive portion of tunnelling. As the excavation face moves away and the system enters the consolidation-controlled stage, mechanical activity subsides and energy demand declines, marking a transition to a low-emission regime.

In terms of spatial configuration, the transverse settlement trough at

t = 10 d aligns well with the analytical profile proposed by Loganathan and Poulos [

33], indicating that settlement during this stage is primarily governed by tail-void closure, early-age shrinkage of the tail grouting, and local stress redistribution. These processes represent energy dissipation within the soil–structure interface. The extent and rate of consolidation therefore describe both deformation recovery and the progressive reduction in embodied energy as soil equilibrium is restored. Subsequently, surface settlement near the right tunnel axis continued to evolve slowly; by

t = 40 d, additional settlement was still recorded, suggesting ongoing soil consolidation and creep deformation consistent with the time-dependent behavior of soft clays described by Vardanega and Bolton [

34]. In contrast, monitoring points farther from the axis showed nearly stable behavior, further demonstrating that the influence of shield tunnelling disturbance decays significantly with distance. Meanwhile, the slow continuation of settlement implies a prolonged phase of residual energy dissipation within the ground and a gradual return toward energy-efficient equilibrium. This gradual decay in deformation rate corresponds to a sustained decline in construction-phase energy intensity.

The left shield cutterhead reached the monitoring section approximately 48 days after the right shield had passed. As shown in

Figure 4, when the cutterhead of the left shield was still about two excavation diameters from the section (approximately 12–15 m), settlements near the left tunnel centerline had already begun to develop noticeably. Within 2–3 days before arrival, additional settlements of about 6.3 mm, 5.9 mm, and 6.1 mm were recorded at LC-A, A-2, and A-3. Mair [

35] described the three-dimensional ground response induced by shield excavation, noting that ground movements can occur in advance of the cutter face within several excavation diameters

O(

D); detectable settlements typically appear within about 1–2

D (where

D is the excavation diameter). This so-called ahead-of-face settlement is influenced by soil permeability, face support pressure, grouting control, and volume loss. Likewise, the analytical solution of Loganathan and Poulos [

33] for surface settlement above circular tunnels in clay provides a theoretical basis for the observed spatial differentiation—most pronounced near the tunnel centerline and gradually diminishing with increasing transverse distance. The observed onset at approximately 2

D in this section is consistent with this range. The slightly earlier response at some points is attributed to pre-disturbance and structural weakening caused by the prior right-tunnel excavation, which reduced soil stiffness and increased sensitivity to subsequent loading. From a sustainability viewpoint, such premature deformation indicates localized zones of mechanical over-activation, where repeated pressurization and compensation grouting raise energy demand and carbon intensity without proportional gains in stability. Targeted control of these early-response zones can therefore improve both deformation control and energy efficiency.

Following the left-shield tail passage, the settlement rate at points near the left tunnel centerline increased markedly. Over the accelerated stage

t = 51–57 d, the additional settlements were approximately 9.5 mm and 10.0 mm at LC-A and A-3, respectively, while A-2 and A-4 exhibited increases of about 8.0 mm and 5.9 mm over the same period. LC-A, located directly above the left tunnel axis, is primarily governed by the disturbance induced by the left-line excavation, whereas A-3 lies in the core region between the two tunnels where the superimposed effects of sequential tunnelling are strongest. Consequently, both points show the largest settlement acceleration and cumulative deformation. As the shield moved away, rates at all points—except those close to the centerline—fell rapidly, then shifted to a slow, consolidation-dominated stage. This indicates that the primary disturbance zone is concentrated within roughly one settlement-trough width on either side of the centerline, consistent with the spatial distribution of the measurements. This significant and persistent additional settlement observed at LC-A and A-3 is consistent with the overlapping disturbance zone described by Chapman et al. [

6] and Chen et al. [

10], in which successive excavations subject the soil to two rounds of stress redistribution and a complex three-dimensional stress path, producing persistent, hard-to-stabilize deformation. Such zones can be regarded as construction-phase “carbon hotspots”, requiring repeated grouting and extended shield operation, and thus disproportionate energy and material input. Recognizing and controlling these zones is therefore critical for both risk mitigation and emission reduction.

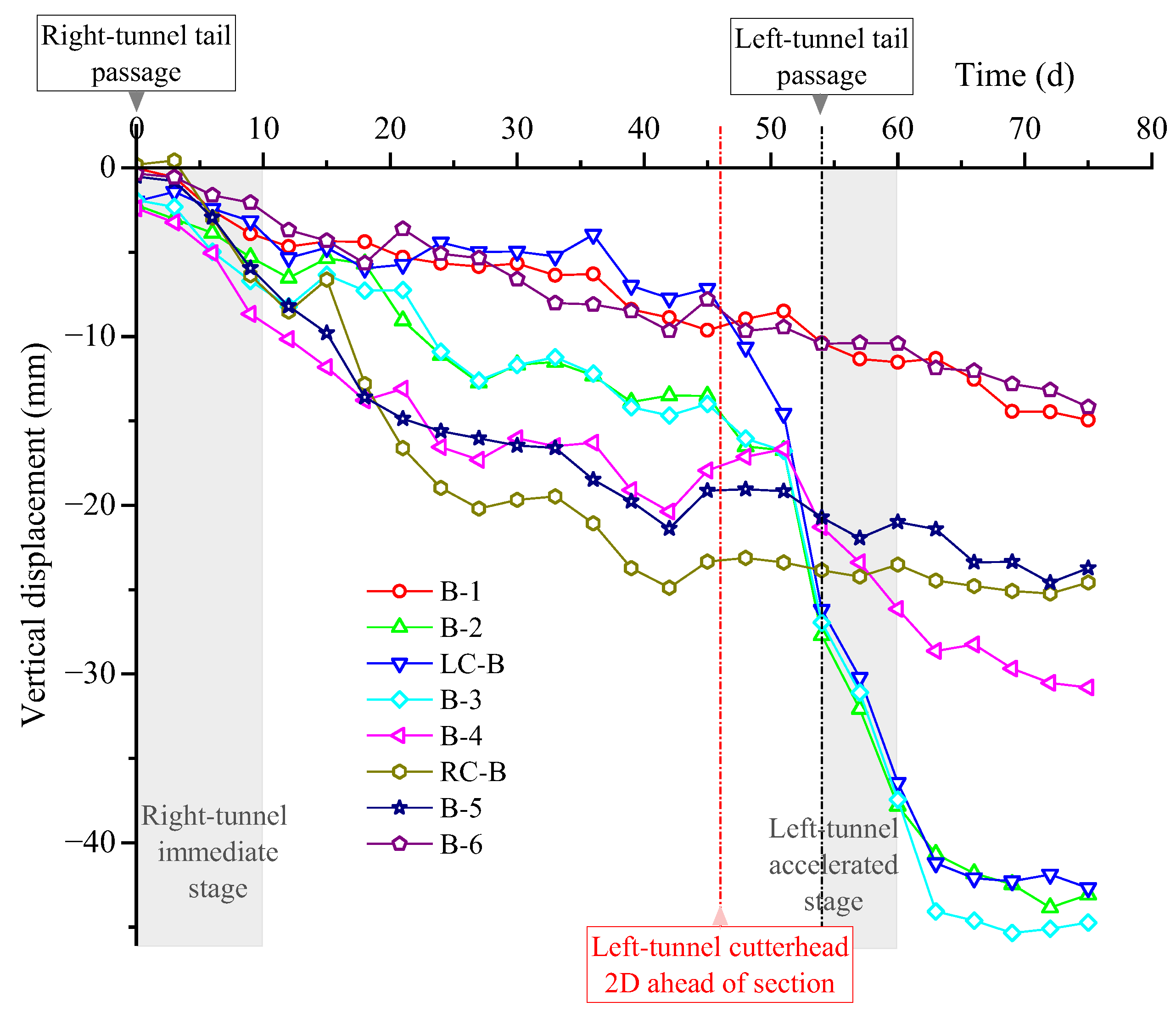

The time-dependent settlement behaviour at the Section B monitoring points is broadly consistent with Section A, as shown in

Figure 5. After the right shield passed, a short-term construction-induced disturbance produced 4–8 mm of settlement within eight days—slightly smaller than in Section A—and then quickly stabilized as the tail moved away. This indicates effective control through advance-parameter optimization, attitude adjustments, and timely synchronous grouting, which also minimized redundant energy input and material consumption at this stage. During the arrival and passage of the left shield, a secondary disturbance with localized accelerated settlement developed. In particular, points near the left tunnel centerline (LC-B, B-2, B-3) exhibited a distinct accelerated stage, with additional cumulative settlement of approximately 24–30 mm, confirming that the principal risk remains concentrated within the interaction zone near the left tunnel. As the excavation face moved away, settlement rates at all points declined quickly and tended toward stabilization; at a few points, a slight rebound/reconsolidation of <1 mm was observed.

The evolution patterns of the monitoring points in Sections C and D (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) are broadly similar during the sequential excavation of twin shields. After the right shield passed first, an immediate settlement phase developed at the centerline and on both sides within 8 days, with maximum values of 6.8 mm at RC-C and 7.9 mm at D-5. Thereafter, the response transitioned into a time-dependent additional settlement stage. Driven by tail-grout bleeding, hydration shrinkage, progressive tail-void closure, and excess pore-pressure dissipation in soft clay, points near the centerline maintained relatively high daily settlements during 8–20 days, and only after about 20 days did the curves gradually enter secondary consolidation. Jin et al. [

36] systematically validated this displacement staging of “immediate settlement–time-dependent settlement” through field monitoring and three-dimensional numerical comparisons. During this period, the energy demand of propulsion and pumping systems gradually decreased, mirroring the mechanical consolidation of the ground. In Section C, a short-term rebound of about 1–3 mm was observed at LC-C and C-2 during days 20–35 prior to the arrival of the left shield, indicating that the stabilizing effects of face-pressure adjustments and secondary grouting were slightly weaker than in Section D. Prior to the arrival of the left shield, the maximum cumulative settlements reached 17.6 mm (RC-C) and 20.3 mm (RC-D), representing increases of more than 150% relative to the values at day 8. Compared with Sections A and B, Sections C and D exhibited faster settlement development during this stage, with greater difficulty in stabilization and noticeably delayed convergence. When the left shield passed, additional settlement continued to accumulate on both sides of the left tunnel centerline and within the interaction zone. As the excavation face moved away, the slopes of the settlement–time curves dropped rapidly and tended toward a plateau. The final maximum settlements were 39.2 mm at C-3 and 38.1 mm at LC-D, approaching but within code limits, and thus remaining under control. Synchronized control of face pressure, shield attitude, and grouting efficiency is thus essential to ensure both stability and construction-phase energy efficiency.

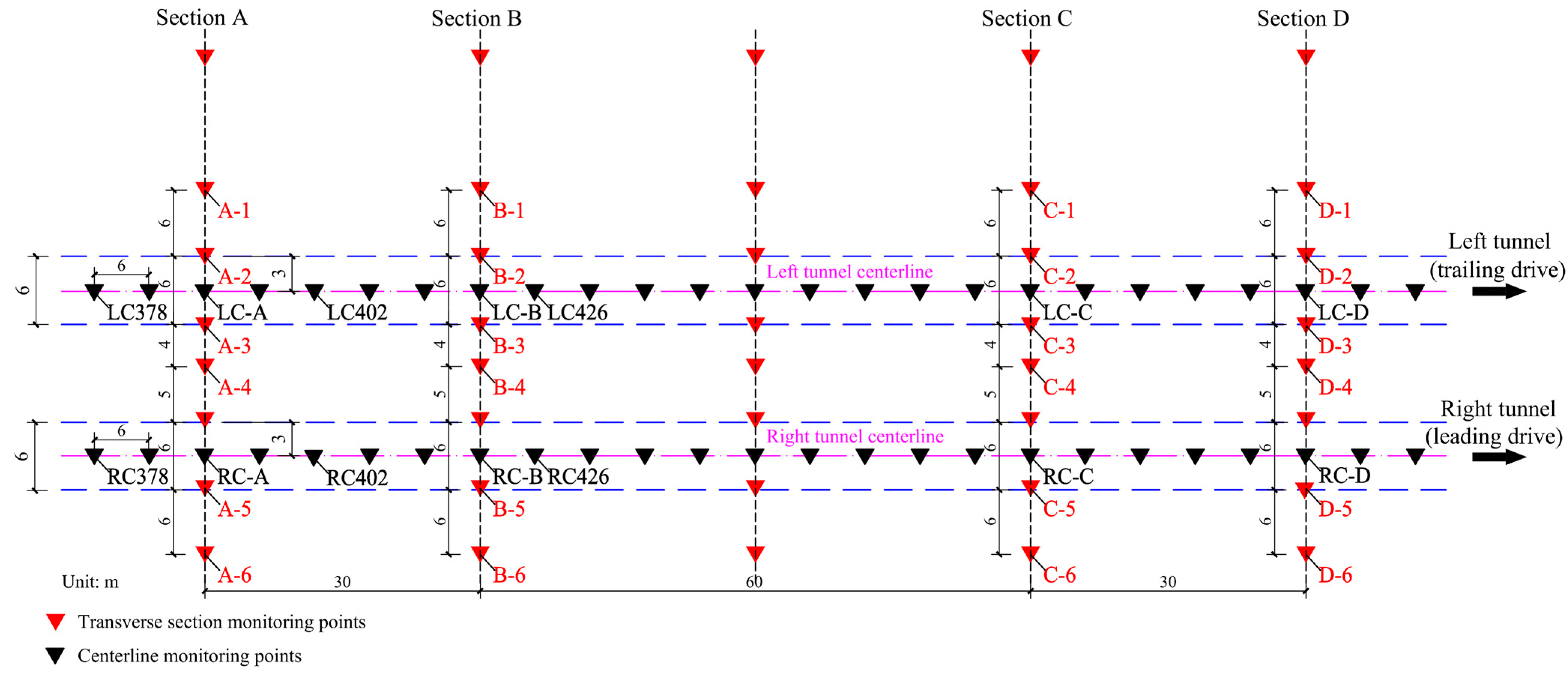

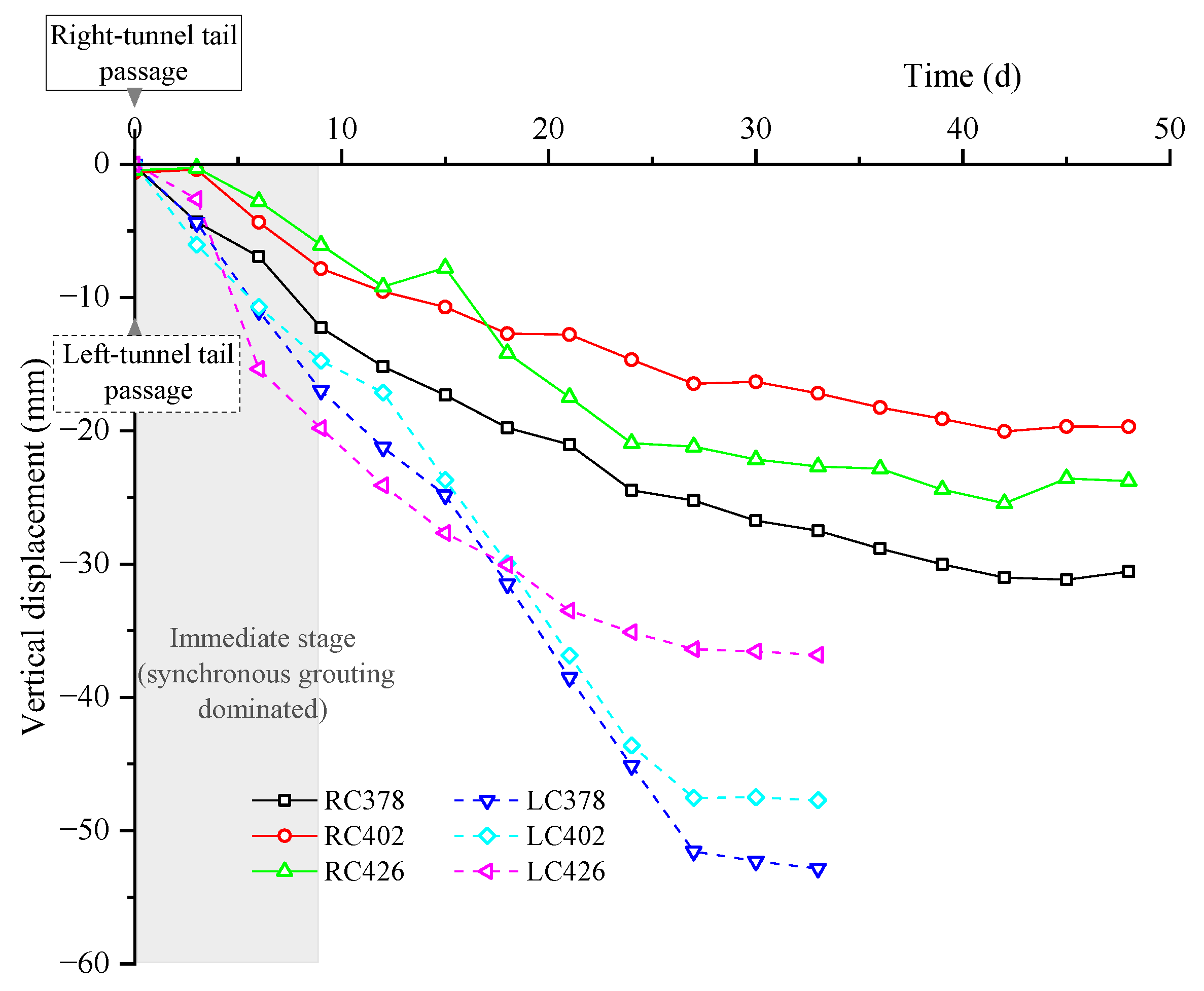

Figure 8 presents the time histories of surface settlement at the centerline monitoring points of the left and right tunnels at K2 + 378, K2 + 402, and K2 + 426. Along the right tunnel centerline, early settlement is characterized by an immediate settlement phase over the first 8–10 days, followed by time-dependent settlement at some points. Along the left tunnel centerline, the leading (right) drive induced only minor pre-settlement; settlement then accelerated markedly as the trailing (left) shield approached, with the principal increment occurring during the left-shield passage. From the observed settlement development, surface monitoring points began to register the influence of the trailing shield approximately 2 days before its arrival, corresponding to an ahead-of-face distance of about 2–3

D. To separate the effects of the two disturbances, the settlement value at

t = −2 d (relative to the left-shield passage) was set as the datum (zero), and subsequent centerline settlement was attributed primarily to the trailing shield.

Based on the monitoring results, settlements along the left tunnel centerline are generally greater than those along the right tunnel centerline, and after the shields passed the monitoring sections, the settlement rate at points along the left tunnel centerline remained noticeably higher than that at points along the right tunnel centerline. Taking the K2 + 402 section as an example, within 8 days after the passage of each shield, the settlement values at RC402 and LC402 reached 7.4 mm and 12.7 mm, respectively, with the latter being about 1.7 times greater. This indicates that LC402 was affected by two successive tunnelling disturbances, during which the soil structure was weakened and its density reduced, leading to larger surface settlement under the influence of the trailing shield. This agrees with Islam and Iskander [

26], who observed that settlement above the trailing tunnel tends to increase significantly in twin-tunnel construction. Mechanically, this intensified phase coincided with peak operational energy and higher short-term carbon intensity. As the face advanced beyond the section, both settlement rate and energy demand declined, indicating recovery of mechanical and energy equilibrium. From a long-term perspective, compared with RC402, the settlement at LC402 tended to stabilize more rapidly after the excavation face moved away, consistent with the two-stage “short-term rapid—long-term slow” response under soft-soil conditions reported by Jin et al. [

36] based on field and numerical evidence. The underlying mechanism can be attributed to the fact that during the excavation of the right tunnel, a disturbance zone and grout body had already formed near the tunnel axis. The second (left) drive advanced through a “disturbed and partially consolidated” stratum, resulting in a larger equivalent volume loss and greater peak settlement. Meanwhile, the shortened drainage path and faster closure of the tail void led to a quicker transition to the stabilization stage. In addition, the duration of time-dependent settlement is closely related to the soil characteristics: in zones dominated by silty sand, dissipation of pore water pressure occurs more rapidly and settlement convergence is achieved sooner; whereas in zones dominated by soft clay, slower pore-pressure dissipation causes prolonged consolidation and delayed convergence. Other monitoring points along the tunnel centerline exhibit similar patterns, further confirming that tunnelling of the trailing shield through already disturbed ground tends to induce greater surface settlement and transiently higher energy use.

4.2. Transverse Ground Settlement Analysis

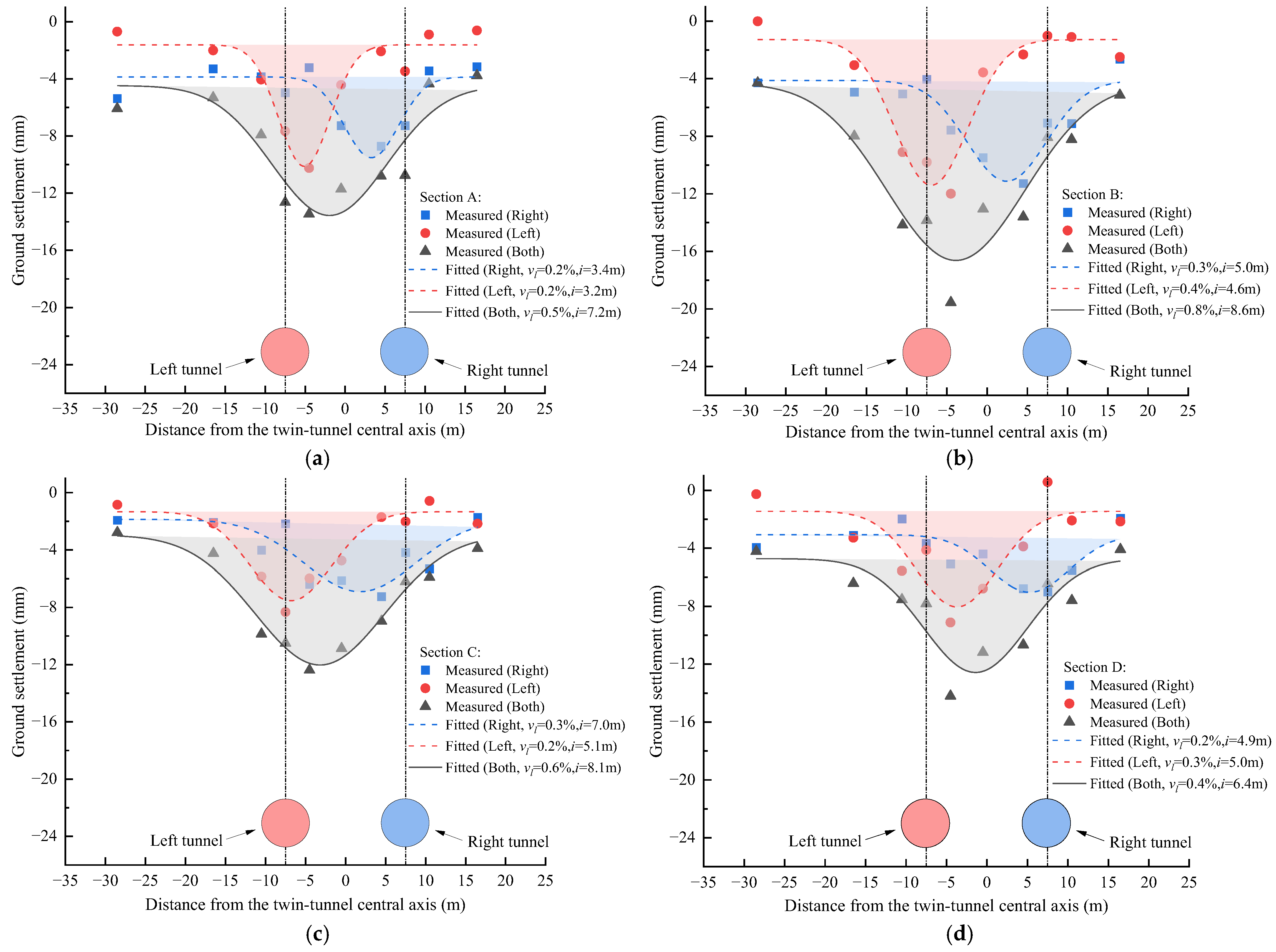

Figure 9 shows the transverse surface settlement curves at each monitoring section before and after the passage of the twin shields. Drawing on previous field observations [

31,

32] and the time-history analysis above, 8–10 days after shield passage is adopted as an empirical boundary at which construction-induced immediate settlement is essentially complete. Accordingly, the ground-monitoring data 10 days after the right-tunnel and left-tunnel passages, respectively, are taken to represent the post-passage transverse settlement state. This temporal boundary also marks the transition from a high-intensity tunnelling stage to a consolidation-dominated, lower-energy regime, aligning mechanical staging with construction-phase energy efficiency.

To obtain the settlement distribution induced solely by the disturbance from the trailing (left) drive, the net settlement increment at any transverse position

x along the section is defined as

where

t+10d is the 10th day after the cutterhead of the left shield passed the section;

t−2d is two days before its arrival; and

Sref is the cumulative settlement referenced to the time of the left-shield passage.

This differencing largely removes the pre-existing contribution of the leading (right) drive prior to the arrival of the left shield, leaving the incremental effect of the trailing drive. Consolidation-related, time-dependent settlement caused by the right shield will continue after the left-shield passage and cannot be completely removed. However, time-history analysis shows that this contribution decays rapidly; by approximately the 10th day after the left-shield passage, the observed increment is predominantly governed by the trailing drive. Based on this, we preprocess the records using Equation (1), construct the transverse settlement troughs Δ

Sref(

x) for each section, and fit them with the Gaussian function recommended by Peck [

37]. In energy terms, Equation (1) isolates the disturbance window in which operational energy input and grouting effort are primarily attributable to the trailing shield, providing a cleaner mapping between deformation increment and construction-phase energy demand.

Peck [

37] showed that tunnel-induced surface settlement can be represented by a Gaussian curve:

Equation (2) can be rewritten as

where

S is the surface settlement (mm);

Smax is the maximum settlement at the tunnel centerline (mm);

y is the transverse offset from the axis (m);

i is the distance from the centerline to the point of inflection of the settlement trough (m);

R is the tunnel excavation radius (m);

D is the shield excavation diameter (m); and

vl is the volume-loss ratio.

From

Figure 9, both the individual-tunnel curves and the superposed (twin-tunnel) curve are satisfactorily fitted by Peck’s Gaussian function. The model uses few physically interpretable parameters and captures the principal shape of the settlement troughs. Nevertheless, because it was developed for single tunnels, it has limitations for twin-tunnel superposition and local heterogeneity. Accordingly, we analyze the trough parameters for the right and left tunnels separately, and then for the superposed (twin-tunnel) response. In view of this framework,

Smax and

i serve as compact spatial indicators for targeting zones prone to concentrated effort and for supporting parameter optimization.

From the fitted curves, a consistent pattern emerges across all sections except Section D: the settlement trough induced by the trailing (left) drive is characterized by a smaller trough width

i than that of the leading (right) drive, while the maximum settlement

Smax is larger. This “deeper–narrower” trough form agrees with the observations of Chen et al. [

10] for Hangzhou Metro Line 2. Mechanistically, stress unloading and structural degradation caused by the leading shield do not fully recover in the short term; when the trailing shield advances within the same influence zone, the soft ground exhibits heightened disturbance sensitivity, producing faster settlement growth and more localized deformation, hence a smaller

i relative to the leading stage. A larger

Smax combined with a smaller

i implies higher instantaneous energy input and grouting intensity per unit width—an indicator of potential “carbon hotspots”. At Section D, by contrast, the trailing (left) drive yields a slightly wider trough than the leading (right) drive, yet still with a markedly larger

Smax. This is mainly attributed to higher backfill–reconsolidation stiffness in the inter-tunnel ground, resulting from tail-void grouting and the initial disturbance from the leading right tunnel. During the left-tunnel drive, grout can preferentially spread along pre-existing loosened paths and sandy interbeds, enlarging the outward diffusion radius and widening the effective influence zone, while the superposition of disturbances elevates the surface peak. From an engineering perspective, tracking

i(

t) and

Smax(

t) in real time can flag periods of excessive energy/material consumption and guide co-optimization of chamber pressure and primary/secondary grouting.

Inspection of the twin-tunnel superposed curves shows that the superposition-fitted settlement trough is, in general, not symmetric about the mid-point between the two tunnels; the extremum shifts toward the trailing (left) side, with the shift more pronounced at Sections B and C. This is consistent with the field-based analysis of Sun et al. [

38]. Before the cutterhead of the trailing shield actually crosses the section, it already generates an ahead-of-face disturbance that amplifies both the magnitude and the duration of deformation within the interaction zone, thereby displacing the maximum toward the trailing side and enhancing asymmetry. Mechanistically, the leading (right) drive creates an unloading/structural-weakening zone between the tunnels, while tail-void grout dewatering/shrinkage and consolidation dissipation are not fully recovered. When the trailing (left) drive advances within this domain, the effective volume loss increases and the peak settlement rises; the Gaussian superposition of the two troughs then causes the composite trough extremum to migrate to one side. Meanwhile, loosened pathways formed during the leading stage enlarge the lateral influence radius of the trailing drive, thickening the left-side “tail” and further breaking symmetry. Lu et al. [

9] also showed via centrifuge modeling that when the monitoring section is oblique to the tunnelling direction, the transverse settlement trough tends to become more asymmetric. For Sections A–C, the fitted volume-loss ratios for the superposed troughs,

vl (0.50%/0.82%/0.57%), are slightly higher than the sum of the left- and right-tunnel values (0.36%/0.62%/0.52%), indicating a cooperative amplification. By contrast, at Section D the superposed

vl (0.39%) is slightly lower than the left + right sum (0.41%), consistent with adequate compensation (face-pressure/grouting), a broader–shallower trough, and stronger rebound at the outer margins–together yielding a partial offset of superposition effects. Thus, sections with

vl (superposed) >

vl (left) +

vl (right) are likely to experience excess energy/material usage, whereas

vl deficit (as at Section D) signals better compensation control and improved construction-phase energy efficiency. When monitoring reveals trailing-side dominance and a clear shift in the composite trough, enhanced attention is required in the inter-tunnel ground and near the trailing axis, and shield attitude, face pressure, and primary/secondary grouting should be jointly optimized.

4.3. Superimposed Disturbance Effects

To quantitatively characterize the superposition of disturbances induced by sequential twin-tunnel construction, we propose a ratio-type index, defined herein as the Twin-Tunnel Interaction Ratio (TIR):

where Δ

SL is the incremental settlement (mm) within the construction acceleration window recorded when the left-line excavation face passes the monitoring section; Δ

SR is the incremental settlement (mm) within the same, consistently defined acceleration window recorded when the right-line excavation face passes the same section; and

TIR is a dimensionless ratio that represents the degree of settlement amplification of the trailing line relative to the leading line.

Building upon previous comparative or ratio-based approaches used to interpret twin-tunnel behaviour [

29,

30], we establish the TIR framework by employing field-measured incremental settlements within a unified acceleration window. This enables a consistent quantification of superposition intensity along both time and alignment and provides a more comparable, monitoring-based evaluation of interaction effects. Operationally, higher TIR values reflect more intense sequential disturbance and typically coincide with concentrated thrust, pressurization, and grouting effort during the acceleration window.

In addition, to account for the influence of short-term rebound during monitoring on the acceleration-window increment, a rebound-sensitivity evaluation is introduced, based on which two definitions of settlement increment are established:

where Δ

Snet is the net settlement increment (mm) excluding rebound; Δ

Senv is the total envelope settlement increment (mm) including rebound;

ηk is the settlement value (mm) recorded at the

k-th observation; and [

t1,

t2] denotes the time window (d) corresponding to the instantaneous construction-acceleration stage.

To minimize subjectivity and ensure comparability across monitoring sections, the acceleration window ω was defined using a fully objective two-parameter criterion. The settlement-rate threshold was set to λ = 0.30 mm/d, corresponding to the 95th-percentile upper bound of consolidation-stage rates and thus distinguishing genuine construction-induced acceleration from post-passage consolidation. To exclude transient fluctuations, the elevated-rate period was required to persist for at least τ = 1.0 day. The acceleration window ω was then taken as the longest continuous segment of the settlement–time curve satisfying both conditions. For all sections, the resulting ω ranged from 2.5 to 3.5 days, consistent with construction records of high-thrust advancement and synchronous grouting. This unified and reproducible definition provides the technical basis for computing ΔSnet and ΔSenv in Equations (5) and (6).

Accordingly, two sets of ratio indices are defined:

To further incorporate rebound sensitivity into the evaluation framework, the rebound ratio (

ρ) is defined as

Because no classification criteria for twin-tunnel interaction have been established in existing studies, empirical thresholds are adopted based on the statistical characteristics of the measured TIR values to meet practical engineering needs. These thresholds are used to classify the TIR into three levels:

If max (TIRnet, TIRenv) < 0.75, the condition is classified as a weak overlapping effect;

If 0.75 ≤ max (TIRnet, TIRenv) < 1.5, it is classified as a moderate overlapping effect;

If max (TIRnet, TIRenv) ≥ 1.5, it is classified as a strong overlapping effect.

To enhance the robustness of the classification, critical threshold bands [0.75 ± ε] and [1.50 ± ε] are defined, with a recommended ε = 0.05. If the TIR value at any monitoring point—under either increment definition—falls within the critical band and satisfies ρ > 0.15 or ΔTIR = TIRenv − TIRnet > δ (recommended δ = 0.20), it is also classified as a strong overlapping condition for pre-control purposes.

Thus, the tiered TIR classification serves not only as a risk trigger but also as a pragmatic proxy for targeting energy-efficient control actions (e.g., low-threshold alerts and focused supplementary grouting).

Building on Peck’s Gaussian trough formulation (Equations (2) and (3)), surface settlement can be characterised by volume loss ratio

vl and trough width

i. To analyse disturbance intensity during the construction acceleration window, we introduce the volumetric increment Δ

VL for this period, representing the corresponding ground loss. The incremental settlement during the acceleration phase can be expressed as

where Δ

VL is the volumetric increment (m

2),

i is the trough width (m), and

y is the transverse distance from the tunnel axis (m). Denoting the left and right tunnel parameters as (Δ

VLL,

iL), (Δ

VLR,

iR, respectively, the first-order approximation of TIR becomes

Equation (10) reveals three components governing TIR:

Volume ratio term (ΔVLL/ΔVLR): The dominant factor reflecting volumetric amplification when the second tunnel advances through pre-disturbed ground.

Trough convergence term (iR/iL): Amplifies TIR when iL < iR, capturing the deeper and narrower characteristics of the trailing tunnel response.

Spatial distribution term exp[–y

2/2(1/

iL2–1/

iR2)]: When

iL <

iR,

TIR(

y) reaches its maximum at the tunnel axis, decreases within approximately one trough width (|

y| ≈

i), exhibits a secondary rise near the trailing tunnel axis, and gradually diminishes in far-field region (|

y| ≥ 2

i). This trend aligns with field observations from EPB twin tunnelling in soft clay [

31] and corroborates the deeper, narrower, and offset pattern identified in the transverse settlement analysis.

In practice, the volume-ratio and trough-convergence terms jointly map to short-term operational intensity; sections with persistently high TIR during the acceleration window tend to require greater instantaneous power and grout delivery.

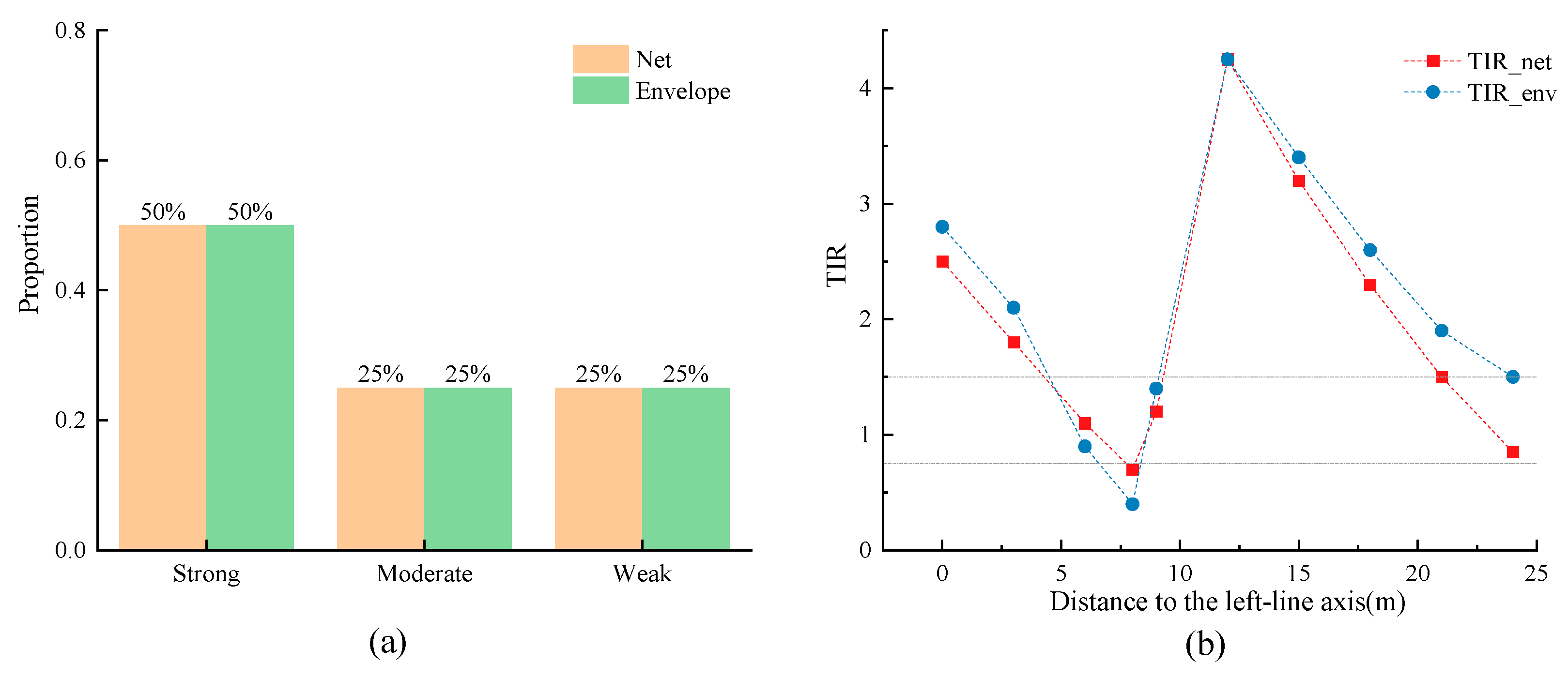

To examine the classification robustness against rebound definitions and reveal the spatial distribution of superposition effects, Section A is analysed as an example.

Figure 10 presents the proportions of strong, moderate, and weak TIR classifications under both Δ

Snet and Δ

Senv definitions, along with their variation with transverse distance from the left tunnel axis (including binned means and 95% confidence intervals). The overall classification proportions remain consistent between definitions (approximately 50%/25%/25% for strong/moderate/weak), indicating that the classification is insensitive to the choice of definition. Both TIR-

y curves exhibit similar peak-valley-peak patterns, with Δ

Senv values only slightly higher in far-field regions (≥ 20–25 m), suggesting that rebound effects primarily influence minor fluctuations at greater distances while having limited impact on near-axis classification.

The spatial zonation of TIR provides guidance for construction control strategies. Within the tunnel axis and trough width zone (|y| ≤ i), superposition effects are most pronounced, requiring designation as a high-sensitivity control zone. In the intermediate zone of 1–2 trough widths (i < |y| < 2i), TIR exhibits a secondary peak reflecting disturbance reconcentration, warranting optimised face pressure and grouting strategies. In far-field regions (|y| ≥ 2i), TIR decreases rapidly with distance, allowing standard monitoring frequencies, though the rebound ratio ρ should be evaluated to identify potential delayed rebound responses.

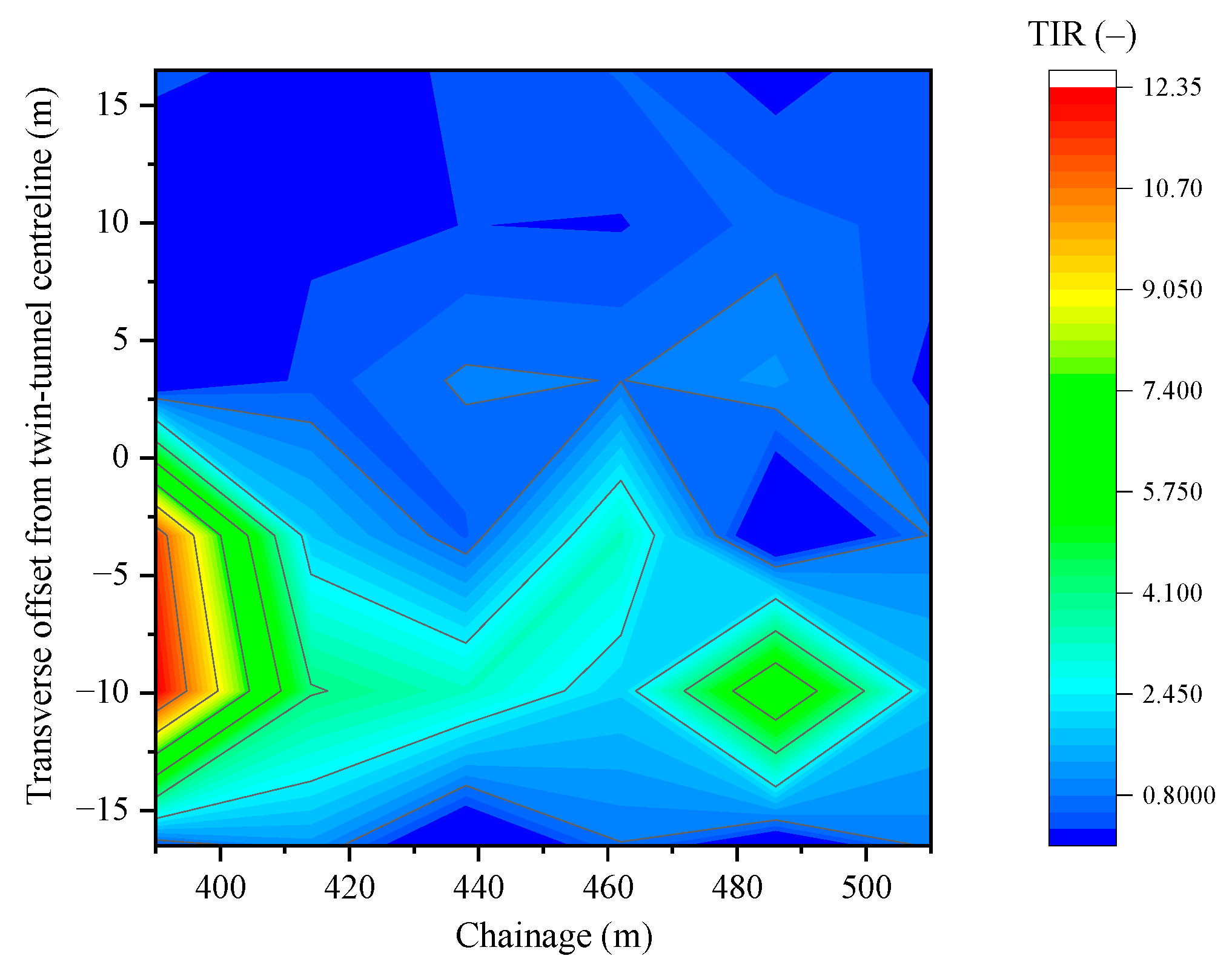

To complement the section-based TIR–

y interpretation, a contour map is further provided to visualise the spatial distribution of interaction along the alignment (

Figure 11). The map, constructed from monitoring-based max (

TIRnet,

TIRenv) values, highlights non-uniform “hotspots” of strong interaction between sections and confirms that elevated TIR is concentrated within the near-field band around the twin-tunnel centreline and decays rapidly with transverse distance. Beyond its mechanical meaning, TIR provides an operational proxy for construction input intensity; higher TIR generally implies greater electricity and grout use within overlapping disturbance zones.

Section 4.4 builds on this proxy and quantifies the environmental implications (energy and carbon) associated with the observed TIR levels.

4.4. Environmental Implications and Carbon Efficiency of Sequential Twin-Tunnel Excavation

4.4.1. Methodological Basis for the Environmental Evaluation

To establish a methodological basis for interpreting the environmental implications of sequential disturbance, the construction-phase carbon emissions are formulated following the activity–emission structure used in life-cycle assessment (LCA):

where

Ai denotes the intensity of construction activities (e.g., electricity use for TBM propulsion, grout consumption, corrective operations) and

fi is the corresponding emission factor. LCA studies consistently show that electricity demand for shield operation and the production of cementitious materials dominate construction-stage emissions [

24,

39], typically accounting for more than 70–85% of the life-cycle total [

40,

41]. Representative emission factors—approximately 0.6 kg CO

2/kWh for regional grid electricity and 0.8–0.9 kg CO

2/kg for ordinary Portland cement—indicate that variations in energy demand and grout usage constitute the most carbon-sensitive components of mechanised tunnelling.

These relationships justify constructing a process-based proxy directly from field-measured deformation behaviour, because the dominant carbon sources are governed by the operational responses triggered by ground disturbance. Accordingly, the subsequent analysis focuses on identifying the deformation characteristics that best represent these disturbance-driven activity intensities. Based on the measured settlement development, the tunnelling process is divided into three construction-phase emission stages consistent with the observed mechanical behaviour:

Immediate settlement stage: corresponding to active shield propulsion, slurry circulation, and synchronous grouting. This period represents the peak in both energy input and settlement rate, dominated by mechanical excavation and high-frequency control of face pressure and grouting volume.

Time-dependent settlement stage: characterized by grout hydration and shrinkage, pore-pressure dissipation, and time-dependent soil deformation. Energy consumption gradually decreases but remains significant due to secondary grouting, continuous operation of support systems, and equipment standby during consolidation.

Secondary consolidation stage: reflecting minimal mechanical activity after the cessation of tunnelling works, with emissions mainly arising from monitoring, maintenance, and auxiliary system operation.

In addition to its mechanical relevance, the three stages correspond to distinct energy-demand patterns that underpin the environmental dynamics of tunnelling. Mechanically, the transformation of shield thrust and torque into ground deformation defines the efficiency of energy transfer. In weakly disturbed soils, most of the input energy contributes directly to advance, while in highly disturbed zones, part of the energy is dissipated as redundant cyclic stress and pore-pressure fluctuation, reducing energy productivity per unit excavation. This physical inefficiency explains why periods of accelerated settlement coincide with peaks in energy use and embodied-carbon output.

These energy-demand patterns provide the physical basis for linking ground-deformation behaviour to construction activity intensity. In EPB tunnelling, two mechanisms primarily govern the activity terms Ai: (i) the representative peak settlement, Smax,avg, reflecting the intensity of compensation actions typically required; and (ii) the active-control duration, ts, representing the period during which settlement rates remain high enough to necessitate continuous intervention.

These two mechanisms can be mapped to measurable settlement characteristics:

Disturbance magnitude, which controls the extent of compensation grouting, face-pressure correction, and thrust adjustment;

Duration of non-steady excavation, during which elevated energy consumption and repeated corrective actions persist.

Assuming the frequency and magnitude of corrective operations scale monotonically with disturbance intensity and duration, the activity term can be approximated as: Ai ∝ Smax,avg ts.

To enable comparison among sections with different disturbance conditions, this activity-based term is normalised to a weak-interaction reference section (Section D), which serves as the baseline for defining the relative carbon-intensity index as

The proposed Ic serves as a process-based, LCA-consistent indicator that links deformation behaviour with construction-phase environmental performance. Derived directly from field-measured settlement characteristics rather than detailed activity inventories, the index enables transparent and reproducible comparison of relative carbon intensity among sections. By anchoring the proxy to the dominant carbon sources and the disturbance-driven control actions that influence them, the framework provides a direct bridge between empirical monitoring and sustainability assessment, allowing in situ evaluation of the embodied-carbon implications of sequential tunnelling.

4.4.2. Environmental Effects of Sequential Disturbance

The sequential nature of twin-tunnel excavation introduces additional embodied carbon compared with single drives. As the trailing shield advances within an already disturbed and partially consolidated zone, duplicated grouting and energy-intensive correction measures are often required to maintain stability [

42]. This cumulative disturbance—quantified by the TIR—can thus be regarded as a measure of “carbon inefficiency”. Sections exhibiting high TIR values correspond to zones of intensified ground–machine interaction and redundant energy input. From an environmental standpoint, these high-TIR areas can be interpreted as “carbon hotspots” where geotechnical and energy inefficiencies converge. Identifying such regions provides a practical pathway to link field monitoring with real-time sustainability management.

To quantitatively relate these interaction patterns to construction-phase carbon intensity, the deformation-derived index

Ic was evaluated for four representative sections and summarised in

Table 2.

Because the relative carbon-intensity index

Ic is directly proportional to the product

Smax,avg·

ts (Equation (12)), any increase in disturbance magnitude and the duration of non-steady excavation will be reflected as a higher

Ic. The

Ic–

TIR relationship summarised in

Table 2 therefore follows directly from the disturbance-driven amplification of energy and grout demand.

Sections A and C, already classified as strong-interaction zones (TIR ≥ 1.5), exhibit both larger settlements (≈35–40 mm) and prolonged high-activity periods (≈250–260 d). Their normalised indices are approximately 2.6 and 3.1 times that of Section D, respectively, implying that these locations required substantially more repeated compensation actions. In operational terms, this corresponds to higher shield-energy consumption (sustained face-pressure control, thrust corrections, extended operation under non-steady attitude) and greater cementitious-material usage in synchronous and secondary grouting—both dominant contributors to embodied carbon during EPB tunnelling. By contrast, Section D (classified as weak interaction, TIR < 0.75) shows smaller peak settlement (≈24 mm) and a much shorter active-control window (≈140 d); it was therefore used as the baseline (relative index = 1.0). The moderate-interaction Section B falls in between (≈1.5× baseline). This non-linear increase in Ic with TIR reflects diminishing environmental efficiency: beyond a critical disturbance level, each unit of settlement control requires disproportionately higher energy and material input, compounding the environmental burden.

From a systems perspective, the co-location of mechanical risk and carbon intensity reveals that the same physical processes responsible for settlement amplification also govern environmental inefficiency. Integrating settlement monitoring into carbon-management frameworks can thus identify both deformation-sensitive and carbon-intensive zones in real time. This coupling enables adaptive control strategies—optimising face pressure, thrust rate, and grout dosage—to achieve concurrent stability enhancement and emission reduction. Such integration of geotechnical response and environmental performance aligns with the life-cycle sustainability principles of underground infrastructure.

From an engineering-control standpoint, TIR is thus not only a deformation-management index but also a sustainability indicator. High TIR (≥1.5) flags zones where advance face-pressure optimization, early micro-adjustment of shield attitude, and low-clinker/high-filler grouting blends can deliver dual benefits: reduced peak settlement and lower construction-phase embodied carbon. Overall, the findings suggest that ground behaviour, energy consumption, and carbon intensity are mutually reinforcing phenomena driven by the same disturbance dynamics. The proposed framework quantitatively links mechanical efficiency and environmental performance, but also provides a basis for broader comparisons and extensions beyond the present EPB case.

To extend the contextual relevance of the findings beyond EPB tunnelling, it is useful to relate the observed sequential-interaction mechanisms to other staged-excavation methods. The New Austrian Tunnelling Method (NATM) provides a representative comparison: its multi-step excavation and stress-redistribution cycles can also generate overlapping influence zones between successive stages. Monitoring-based NATM studies [

43] report that the accumulation of stress redistribution across excavation steps can lead to asymmetric and difficult-to-stabilise ground responses, echoing the sequential interaction pattern associated with high TIR in this study. The main difference lies in disturbance distribution: NATM typically produces a broader but more diffuse influence zone due to greater stress release, whereas EPB tunnelling induces a more localised, deeper–narrower response governed by face-pressure confinement and synchronous grouting. This suggests that although the TIR framework is developed for mechanised EPB tunnelling, it represents a generic disturbance-superposition mechanism that could, with appropriate calibration, be adapted to other staged-excavation tunnelling methods.

Beyond the methodological comparison, the interaction mechanisms quantified in this study—such as ahead-of-face disturbance from the trailing excavation, cumulative ground response within overlapping influence zones, and the non-linear amplification reflected by high TIR—are governed primarily by soil–structure interaction and are therefore not exclusive to metro tunnels. Accordingly, similar effects may arise in highway tunnels when twin or closely spaced bores are excavated sequentially [

44]. This implies that amplification and asymmetry of settlement troughs should be incorporated into design envelopes, that refined control of face pressure and excavation attitude is required during the trailing drive within predicted interaction zones, and that optimization of bore spacing or excavation timing can reduce duplicated disturbance and associated grouting demand. Consequently, the sequential-interaction framework established here offers a transferable basis for improving both deformation control and environmental performance in highway tunnel construction.

In addition to the above engineering implications, the environmental performance of sequential tunnelling can also be improved through the adoption of green construction materials and low-carbon technologies. In high-interaction (high-TIR) zones, where repeated grouting and intensified face-pressure control typically increase embodied carbon, the use of low-clinker or supplementary-cementitious-material (SCM) grouts can substantially reduce cement-related emissions while maintaining the required rheological and mechanical performance, as demonstrated in recent evaluations of SCM-based backfilling grouts for shield tunnelling [

45]. Likewise, incorporating shield muck and other recycled constituents into backfilling mixtures offers a viable pathway to reduce the reliance on cementitious binders and enhance environmental sustainability without compromising engineering applicability [

46]. Furthermore, emerging carbon-neutral technologies—such as electric or hybrid shield drive systems, energy-recovery hydraulic units, and real-time parameter optimization supported by digital monitoring—provide additional means of mitigating the energy peaks associated with sequential excavation. Integrating these material- and technology-based measures with the interaction-based control framework developed in this study can therefore enhance both deformation management and construction-phase carbon efficiency.