Governing the Fab Lab Commons: An Ostrom-Inspired Framework for Sustainable University Shared Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Introduces the institutional analysis for sustainable commons of Elinor Ostrom, who was awarded the 2009 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for her analysis of institutional governance, especially the commons;

- Reviews significant studies on the commons in the university Fab Labs;

- Reconstructs Ostrom’s framework to accommodate higher education institutions;

- Analyzes the Fab Lab space and its policies using the proposed analysis framework (reconstructed framework);

- Reveals a sustainable paradigm for commons in the university space for responding to the rapidly changing educational environment.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

2.1. Review of Literature on the Commons

2.2. Review of Literature on the Fab Lab Commons

2.3. Restructuring Ostrom’s Framework for the University Context

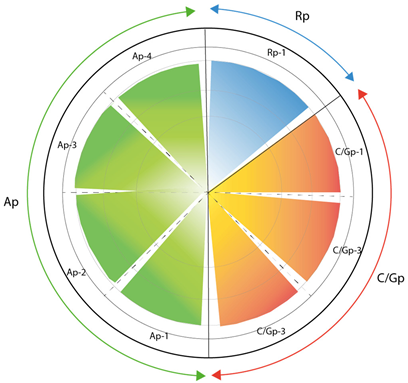

- Resource Policy (Rp): Aligns with the university’s “Facility Management” codes, addressing the physical boundaries of shared spaces.

- Actor Policy (Ap): Corresponds to Student Affairs regulations, transforming static user lists into dynamic ‘rules-in-use’ (e.g., monitoring and sanctions).

- Community/Governance Policy (C/Gp): Maps to the decision-making hierarchy, shifting from top-down control to polycentric self-governance.

3. Research Methodology and Research Studies

3.1. Research Design

3.1.1. Data Collection and Limitations

- Archival Analysis (Applied to Rp & C/Gp Indicators): We systematically reviewed internal institutional documents, specifically the SNU Facility Management Status Report [44]. These documents provided baseline data on the university’s historical space allocation. This analysis was crucial for evaluating ‘Resource Unit Mobility’ (Table A4) by highlighting the structural inability to share resources across departmental silos before the introduction of the new framework.

- Digital Infrastructure Analysis (Applied to Rp Indicators)—CAFM (Computer Aided Facility Management) logs: We analyzed the operational protocols of SNU’s official Integrated Space Management System (https://ist.snu.ac.kr/en/space-management/, accessed on 20 November 2025 [45]). This system manages information on university buildings, floors, and room details, while allowing users to reserve individual rooms through the Information Technology Services Department. We juxtaposed this centralized platform—which typically requires rigid login credentials and pre-authorization—with the Idea Factory’s autonomous booking platform. This comparison serves as empirical evidence for the university’s Resource Policy (Rp), validating how the institution technically overcame historical barriers to enable campus-wide space sharing.

- Fab Lab’s Digital Logging and Monitoring (Applied to Ap Indicators): Instead of relying on manual observation, we utilized the Idea Factory’s dedicated digital infrastructure, specifically its exclusive web-based Real-time Space Occupancy Dashboard and Equipment Reservation System logs. We analyzed six months of log data from this facility-specific platform to track actual usage patterns, peak-time congestion, and no-show rates. This quantitative data was directly used to assess the ‘Monitoring’ level (Table A3), verifying whether the surveillance mechanism operates via autonomous transparency (Level 1) or hierarchical control (Level 3).

3.1.2. Operational Context: From Exclusivity to Open Commons

- Universal Access via Education: Any university member, regardless of major, is granted access rights upon completing a mandatory environmental safety training session.

- Digital Self-Regulation: Due to the high volume of diverse users, manual management was deemed inefficient. Consequently, an internet-based reservation system (Figure 2) was implemented. This system allows for real-time traffic management and ensures fair distribution of resources without constant staff intervention.

- 24-Hour Autonomous Maintenance: The digital logging system enables the facility to operate on a 24 h basis through user autonomy, contrasting sharply with the rigid “9-to-6” operating hours of typical administrative offices.

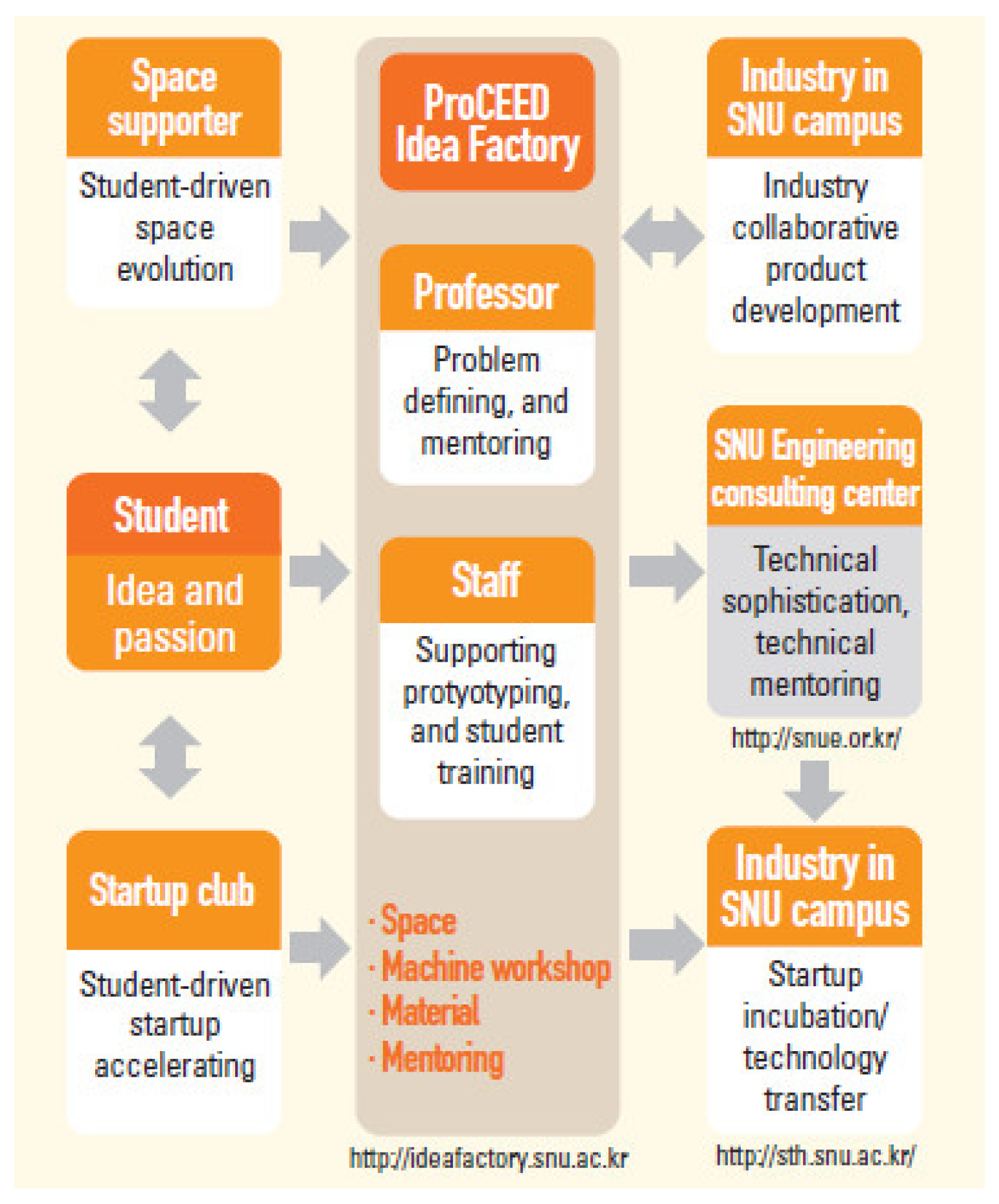

3.2. Fab Lab Space as the Strategy of Universities

3.3. Sharing Strategies Through Fab Labs (Idea Factory)

4. Results

4.1. Restructured Framework for Analyzing Sustainable Sharing Scheme in the Space Policy of Fab Labs

- A.

- Policy categories (Rp, Ap, C/Gp);

- B.

- Policy variables (applying Ostrom’s eight principles);

- C.

- Variable details;

- D.

- Policy for applied cases (Fab Lab policy).

| A. Policy Category Rp (Resource (Space) Policy) | B. Policy Variables (Ostrom’s 8 Principles for Managing a Commons) | C. Variables Details | D. Fab Labs policy (IDEA Factory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rp-1 | Boundaries of users and resources are clear. (Resources boundary) | Resource unit Mobility | Clear system of equipment room/other rooms |

| Distribution a_ temporal heterogeneity | Various and multiple deployments of each piece of equipment make it possible for bookers to choose from them | ||

| Distribution b_ spatial heterogeneity | Shared using efficient equipment via the timetable and deployment time. Available 24 h a day 365 days a year. | ||

| Rp-2 | Boundaries of users and resources are clear. (Users boundary) | Group size | All members can use the building even though it belongs to the engineering college. |

| Technology used | Fabrication technology—a certificate of completion of safety education is required for all members to enter. | ||

| Policy category Ap (Actor policy) | Policy variables (Ostrom’s 8 Principles for managing a commons) | Variables details | Fab Labs policy (IDEA Factory) |

| Ap-1 | Congruence between benefits and costs. | Location | It is included in the engineering college due to its location, so management and workforce distribution are carried out within the engineering college student and system. |

| Property-Rights regime | It belongs to a college, but all members use it regardless of time, in line with the fab lab’s basic purpose. | ||

| Provision | The status of facilities and spaces available on the website can be seen. | ||

| Appropriation | Members can schedule bookings through the website. | ||

| Ap-2 | Regular monitoring of users and resource conditions | Sanctioning | A user’s reservation status is monitored in the timetable |

| Monitoring | Equipment usage status can be monitored by equipment | ||

| Ap-3 | Nested enterprises. | Governance Rules | It is classified as a Basic educational facility, but has self-governing rule in use. |

| Ownership | The administrative office of a university | ||

| Network Structure | University offices and adjuncts | ||

| Ap-4 | Graduated sanctions. | History of Use | Restrictions on the use of “No show” more than three times |

| Policy category C/Gp (Community/Governance policy) | Policy variables (Ostrom’s 8 Principles for managing a commons) | Variables details | Fab Labs policy (IDEA Factory) |

| C/Gp-1 | Collective-choice arrangements | Operational rules | There is a separate policy from the space use regulations of this university or the Ministry of Education. |

| C/Gp-2 | Conflict resolution mechanisms | Conflict resolution | Arbitration through regulation |

| C/Gp-3 | Minimal recognition of rights by government | Collective-choice rules | Reflections of actual user’s opinion in the space planning stage with a student-led space cooperation team and the university’s space use regulations |

4.2. Analysis of Fab Lab Shared Scheme

4.2.1. Resource (Spaces and Facilities) Analysis

- Resource unit mobility: clear system of equipment room/other rooms;

- Distribution a_ temporal heterogeneity: various and multiple deployments of each piece of equipment make it possible for bookers to choose among these pieces;

- Distribution b_ spatial heterogeneity: efficient shared use of equipment via the timetable and deployment time; available 24 h a day, 365 days a year;

- Group size: open to all members although it belongs to the engineering college;

- Technology used: fabrication technology (all members must have a certificate of completion of safety education training to enter the space).

4.2.2. Actor (Rules for Users) Analysis

- Location: It is included in the engineering college owing to its location, and therefore, its management and workforce distribution are conducted within the engineering college student system.

- Property Rights Regime: It belongs to a college, but all members can use it, regardless of time, in line with the Fab Lab’s basic purpose.

- Provision: The status of facilities and spaces available are displayed on the website.

- Appropriation: Members can schedule bookings through the website.

- Sanctioning: User reservation status is monitored through a timetable.

- Monitoring: The usage status of each piece of equipment can be monitored.

- Governance Rules: It is classified as a Basic educational facility but has self-governing rule in use.

- Ownership: The administrative office of the university is the owner.

- Network Structure: The university offices and adjuncts are included in the network.

4.2.3. Community/Governance Analysis

- Operational rules: A policy separate from the space use regulations of the university or the Ministry of Education is used.

- Conflict resolution: Arbitration is conducted through regulations.

- Collective choice rules: The actual users’ opinions are reflected in the space planning stage with a student-led space cooperation team and the university’s space use regulations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Defining Institutional Sustainability

5.2. Comparative Analysis and Scalability

- MIT Media Lab (USA)—Market-driven Model: Characterized by high global network participation and open governance supported by substantial corporate sponsorship.

- Tsinghua University (China)—State-driven Model: Driven by national innovation strategies and large-scale expansion directives.

- SNU Idea Factory (Korea)—Commons-driven Model: Characterized by the recycling of idle internal resources and student self-governance within a hierarchical university system.

5.3. Institutional Tensions and Nested Enterprises

5.4. Implications for Future University Planning

- Securing Flexibility of Physical Boundaries (Rp): To convert non-common spaces into commons, a flexible classification system is required. Instead of rigid space programs based on complex arithmetic systems, universities should adopt simple classification standards that allow for rapid functional changes. This is particularly relevant given the macro-context of declining school-age populations; our Resource Policy (Rp) offers a method to identify and convert underutilized “dead spaces” resulting from departmental exclusivity into active shared commons.

- Establishing Collaborative User Policies (Ap): Abstract regulations fail in flexible environments. Rules must be specific and integrated into a “collaborative infrastructure” based on information sharing. Following Benkler’s concept of “peer production,” self-governing monitoring through transparent information systems is more effective than top-down “organized monitoring.” When information is shared and rules are clear, compliance increases, and dispute settlement becomes autonomous.

- Polycentric Governance Structures (C/Gp): To revitalize the knowledge community, the scope of stakeholders must expand to include users. Universities need to shift from “huge masterplans” to “mutual or partial coordination.” A horizontal organizational system should be created where spatial issues are resolved through stakeholder involvement rather than solely by headquarters. Furthermore, the relationship between participation procedures and rights must be clearly stated in policy, distinguishing between ownership rights and usage rights.

6. Conclusions

Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Analytical Variables and Assessment Indicators for University Shared Spaces

| Resource System (RS) | Resource Unit (RU) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | |||

| Boundary clarity | size | Equilibrium properties | Location | Resource Unit Mobility | Interaction | size | Distinctive marking | Distribution | |||

| Actors (A) | Action Situations (AS) | ||||||||||

| j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | |

| Group size | History of Use | Location | Leadership | Technology used | Monitoring | Sanctioning | Conflict resolution | Provision | appropriation | Policy making | |

| Governance System (GS) | |||||||||||

| u | v | w | |||||||||

| rules | Property-rights regime | Network Structure | |||||||||

| operational rules/collective-choice rules/constitutional rules | private/ public/ common/mixed | centrality/Modularity/Connectivity/Number of Level | |||||||||

| Setting Variable | Core Variable | Sub-components | |||||||||

| u | GS (Governance System) 1 rules | (1) Operational rules | |||||||||

| (2) Collective-choice rules | |||||||||||

| (3) Constitutional rules | |||||||||||

| v | GS (Governance System) 2 property-right regime | (1) Private | |||||||||

| (2) public | |||||||||||

| (3) common | |||||||||||

| (4) mixed | |||||||||||

| w | GS (Governance System) 3 Network structure | (1) centrality | |||||||||

| (2) modularity | |||||||||||

| (3) connectivity | |||||||||||

| (4) Number of levels | |||||||||||

| Assessment Criteria for Governance Policy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Category | C/Gp | Community/Governance Policy | |||

| Sub-category | C/G-2 | Conflict Resolution Mechanisms | |||

| Variable | v | Property-rights regime | |||

| Evaluation | |||||

| Evaluation Purpose | To evaluate the level of user participation in the committee and the distribution of rights to induce a knowledge community | ||||

| Assessment Method | Evaluation based on the allocation of spatial rights (Access, Lease, Exclusion, etc.). | ||||

| Scoring Criteria | Score = Weight × Points | ||||

| Grading | Cross-level indicators | Weight | |||

| Level 1 | Common | 1.0 | |||

| Level 2 | Mixed | 0.7 | |||

| Level 3 | Public | 0.4 | |||

| Level 4 | private | 0 | |||

| Data Source | |||||

| Data Source | Governance regulations, Space management by laws | ||||

| Rationale | |||||

| Rationale | Authority items are classified based on where decision-making power is primarily located: Public when authority is concentrated in the central administration, Private when it mainly resides in colleges, Common when shared among all stakeholders, and Mixed when authority is relatively evenly distributed between stakeholders and the central or college level. | ||||

| Space Authority | |||||

| a | Right to access | ||||

| b | Right to lease | ||||

| c | Right to receive revenue | ||||

| d | Right to occupy | ||||

| e | Right to generate revenue | ||||

| f | Right to exclusion | ||||

| g | Right to determine use | ||||

| h | Right to alienation | ||||

| Assessment Criteria for Actor Policy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Purpose | Ap | Actor Polic | ||

| Assessment Method | Ap-2 | Monitoring Activities | ||

| Scoring Criteria | o | Monitoring (Detailed Item) | ||

| Evaluation | ||||

| Evaluation Purpose | To assess whether monitoring is conducted via “autonomous information sharing” rather than “organized surveillance.” | |||

| Assessment Method | Evaluation based on the existence and transparency of the information sharing system | |||

| Scoring Criteria | Score = Weight × Points | |||

| Grading | Cross-level indicators | Weight | ||

| Level 1 | Environmental Monitoring exists (Digital dashboard transparency) | 1.0 | ||

| Level 2 | Environmental system exists, but combined with hierarchical surveillance. | 0.7 | ||

| Level 3 | No system; relies solely on hierarchical (social) surveillance | 0.4 | ||

| Level 4 | No monitoring system exists or rules are ignored | 0 | ||

| Data Source | ||||

| Data Source | Space information regulations, Log data from reservation systems | |||

| Rationale | ||||

| Rationale | 1. Environmental 2. Social It is evaluated based on the classification and degree of hierarchical oversight by the central administration. - Lower-level variables of the sub-category | |||

| Assessment Criteria for Resource Policy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Category | Rp | Space policy |

| Sub-category | Rp-1 | Clear Boundaries and Membership |

| Variable | e | Resource unit mobility |

| Evaluation | ||

| Evaluation Purpose | To assess the flexibility of boundaries across colleges, spatial units, and user groups | |

| Assessment Method | Count of boundary crossings (mobility instances) | |

| Scoring Criteria | Score = Mobility Count × Points: Mobility across college boundaries | |

| Grading | Indicators | Count of boundary crossings |

| Level 1 | Mobility across college boundaries | |

| Level 2 | Mobility across spatial hierarchy (Building/Room) | |

| Level 3 | Mobility across facility classification | |

| Level 4 | Mobility across user definitions | |

| Data Source | ||

| Data Source | - CAFM (Computer Aided Facility Management) logs, Changes in facility standards. | |

| Rationale | ||

| Rationale | Changes to CAFM (Computer-Aided Facility Management) and Ministry of Education Facility Standards | |

| Main Category | Rp | Ap | C/Gp |  | |||||

| Sub- category | Rp Clear Boundaries & Membership | Ap-1 Rules are adapted to student project cycles | Ap-2 Monitoring | Ap-3 Nested Enterprises | Ap-4 Graduated Sanctions | C/Gp-1 Collective-Choice Arrangements | C/Gp-2 Conflict Resolution | C/Gp-3 Minimal Recognition of Rights | |

| Achievement Level | Robust 1 | Robust 1 | Robust 1 | Robust 1 | Robust 1 | Clear Application 1+ | Robust 1 | Robust 1 | Achievement Level Chart |

Appendix B. Interview with the Manager of Idea Factory at Seoul National University

- Fabrication Zone: Equipped with 3D printers, laser cutters, and CNC machines.

- Open Studio: Large tables for team collaboration and prototyping.

- Meeting Rooms: Enclosed spaces for brainstorming sessions.

- Rest/Community Area: A lounge-like space for casual interaction and networking.

References

- Hamadi, M.; El-Den, J. A conceptual research framework for sustainable digital learning in higher education. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M. Pandemics and the Future of Urban Density; Harvard Graduate School of Design: Cambridge, MA, USA, 4 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. The effect of metacognition and self-directed learning readiness on learning performance of nursing students in online practice classes during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.; Baek, J. A Study on the Change of Spatial Structures of Shared Space at Urban Campuses. J. Archit. Inst. Korea Plan. Design. 2018, 34, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Walter-Herrmann, J. Fab Labs—A Global Social Movement. Fab Labs. of Machines, Makers and Inventors, Illustrated ed.; Transcript-Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H. Fab Lab and Fab City: Civil Maker Space; Korean Academic Information: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Galuppo, L.; Kajamaa, A.; Ivaldi, S.; Scaratti, G. Translating Sustainability into Action: A Management Challenge in Fab Labs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fab Charter. Available online: https://fab.cba.mit.edu/about/charter/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Oh, Y. Student Entrepreneurship at Cornell University: A Case Study; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Local School Applies for STEM Grant: University Fab Labs Inspires Need; Targeted News Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the ev Elinor Ostrom. Collective Action and the Evolution of Social Norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.A.M.; Llamas-Salguero, F.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.R.; del Campo, J.L.C. Digital Technologies at the Pre-University and University Levels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.-A.; Rosa-Napal, F.-C.; Romero-Tabeayo, I.; López-Calvo, S.; Fuentes-Abeledo, E.-J. Digital Tools and Personal Learning Environments: An Analysis in Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessen, J.; Nuvolari, A. Knowledge Sharing Among Inventors: Some Historical Perspectives. Microeconomics: Search, Learning, Information Costs & Specific Knowledge. 2011. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/89342/1/67144297X.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Gershenfeld, N. Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop-from Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, L.; Moultrie, J. Design for Social Sustainability: Using Digital Fabrication in the Humanitarian and Development Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Tragedy of the Ecological Commons. In Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 438–440. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A Diagnostic Approach for Going beyond Panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, G.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J. Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, M. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich, J. Creative spaces: Flexible environments for the 21st-century learner. Knowl. Quest 2014, 42, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Dellenbaugh, M.; Kip, M.; Bieniok, M.; Müller, A.; Schwegmann, M. Urban Commons: Moving Beyond State and Market; Bauverlag: Gütersloh, Germany; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-p. A Theoretical Review on the Reconstruction of the Commons: A Reinterpretation of Garrett Hardin’s ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ Model through the Theory of Space by Henry Lefebvre. MARXISM 21 2014, 11, 172–201. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.H.; Epstein, G.; Mcginnis, M.D. Digging deeper into Hardin’s pasture: The complex institutional structure of ‘the tragedy of the commons’. J. Institutional Econ. 2014, 10, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.R.; Davis, W.D. High-Performance Work Systems and Organizational Performance: The Mediating Role of Internal Social Structure. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, S.; Lakhani, K.R. Organizations in the Shadow of Communities. In Communities and Organizations; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; Volume 33, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fab Lab Network. Available online: https://fabfoundation.org/global-community/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Park, E.J. Strategy of Water Distribution for Sustainable Community: Who Owns Water in Divided Cyprus? Sustainability 2020, 12, 8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Y. The political economy of the commons. Upgrad. Eur. J. Inform. Prof. 2003, 4, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Primeri, E.; Reale, E. The Transformation of University Institutional and Organizational Boundaries [Electronic Resource]: Organizational Boundaries, 1st ed.; Higher Education Research in the 21st Century, The CHER Series; Brill Academic Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Unterfrauner, E.; Hofer, M.; Pelka, B.; Zirngiebl, M. A New Player for Tackling Inequalities? Framing the Social Value and Impact of the Maker Movement. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C.; Ostrom, E. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons—From Theory to Practice; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.C.; Iversen, O.S. Participatory design for sustainable social change. Des. Stud. 2018, 59, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, K.; Hielscher, S.; Merritt, T. Making things in Fab Labs: A case study on sustainability and co-creation. Digit. Creat. (Exeter) 2016, 27, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravilhas, S.; Martins, J. Strategic knowledge management in a digital environment: Tacit and explicit knowledge in Fab Labs. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, S.; Pólvora, A. Social sciences in the transdisciplinary making of sustainable artifacts. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2016, 55, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtala, C. Making “Making” Critical: How Sustainability is Constituted in Fab Lab Ideology. Des. J. 2017, 20, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, J.; Sorivelle, M.; Deljanin, S.; Unterfrauner, E.; Voigt, C. Is the Maker Movement Contributing to Sustainability? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.; Ban, S.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.; Choi, H. Future Strategies of Education for Cultivating Creative Talents in the 21st Century; RR 2011-01; Korean Educational Development Institute: Jincheon-gun, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul National University. Emergency Operations Plan; Seoul National University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Information Systems & Technology, Seoul National University. Integrated Space Management System. Available online: https://ist.snu.ac.kr/en/space-management/ (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Choi, J.-s. Rearrangement of Urban Residential Communities in the U.S.: Based on the Commons Theory. J. Korean Reg. Dev. Assoc. 1995, 7, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Cho, C. A Study on the Efficient Management of Space and Facilities in National Universities. Rev. Korean Inst. Educ. Facil. 2008, 15, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.R. Study on Development of Evaluation Indicators for Effective Utilization of University Facility Space; Ministry of Education and Science Technology (MEST): Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.-K.; Lim, H.-C. A Study on the Payment for the Space Charging System of University Facilities. J. Korea Facil. Manag. Assoc. 2012, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Idea Factory. Available online: http://snuecc.snu.ac.kr/ideafactory/ (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Benkler, Y. Sharing Nicely: On Shareable Goods and the Emergence of Sharing as a Modality of Economic Production. Yale Law J. 2004, 114, 273–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eunki, K. Study on Institutional Principles and Analysis Framework for Managing Campus Commons: Focused on the Case Studies of Seoul National University and Universities in Hong Kong. Doctoral Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

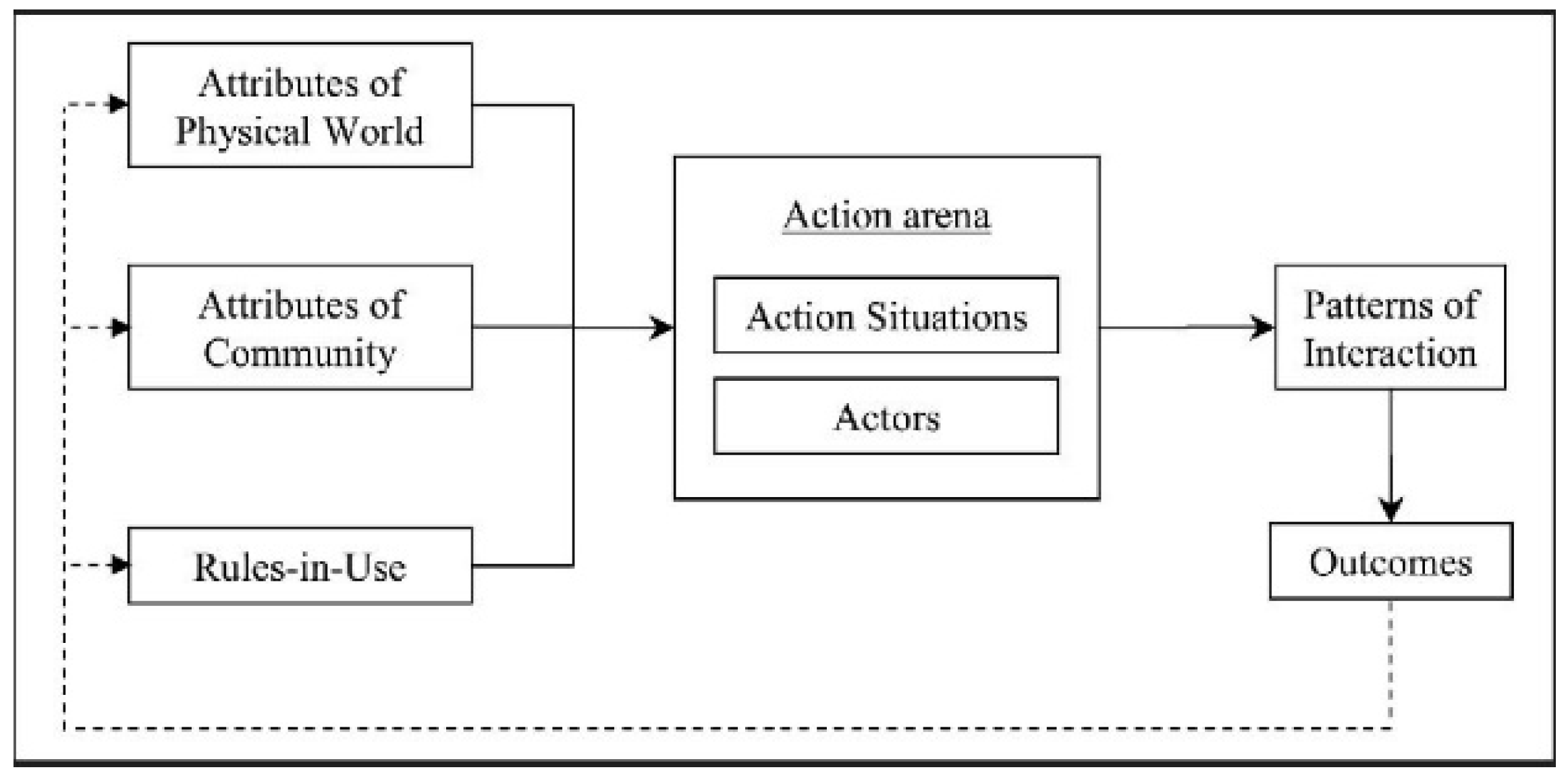

| Definition of Commons | IAD Framework | Three Factors of Commons | Conceptual Framework for University Shared Space |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common resources | Physical-world | Resources | (Rp) Space (facility) policy |

| Institutions (common practices) | Institution | Rule in use | (Ap) Actor policy |

| The communities (commoner) | Community | Communities | (C/Gp) Community/Governance policy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, E.; Shin, Y.-j. Governing the Fab Lab Commons: An Ostrom-Inspired Framework for Sustainable University Shared Spaces. Buildings 2026, 16, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010228

Kang E, Shin Y-j. Governing the Fab Lab Commons: An Ostrom-Inspired Framework for Sustainable University Shared Spaces. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010228

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Eunki, and Yoon-jeong Shin. 2026. "Governing the Fab Lab Commons: An Ostrom-Inspired Framework for Sustainable University Shared Spaces" Buildings 16, no. 1: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010228

APA StyleKang, E., & Shin, Y.-j. (2026). Governing the Fab Lab Commons: An Ostrom-Inspired Framework for Sustainable University Shared Spaces. Buildings, 16(1), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010228