LoopRAG: A Closed-Loop Multi-Agent RAG Framework for Interactive Semantic Question Answering in Smart Buildings

Abstract

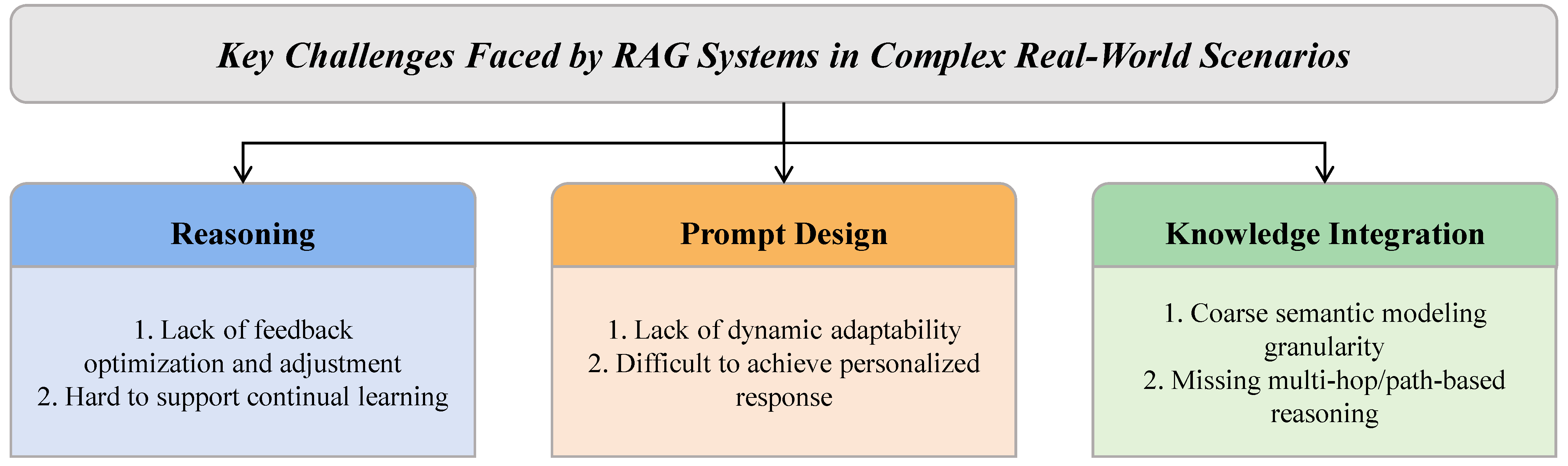

1. Introduction

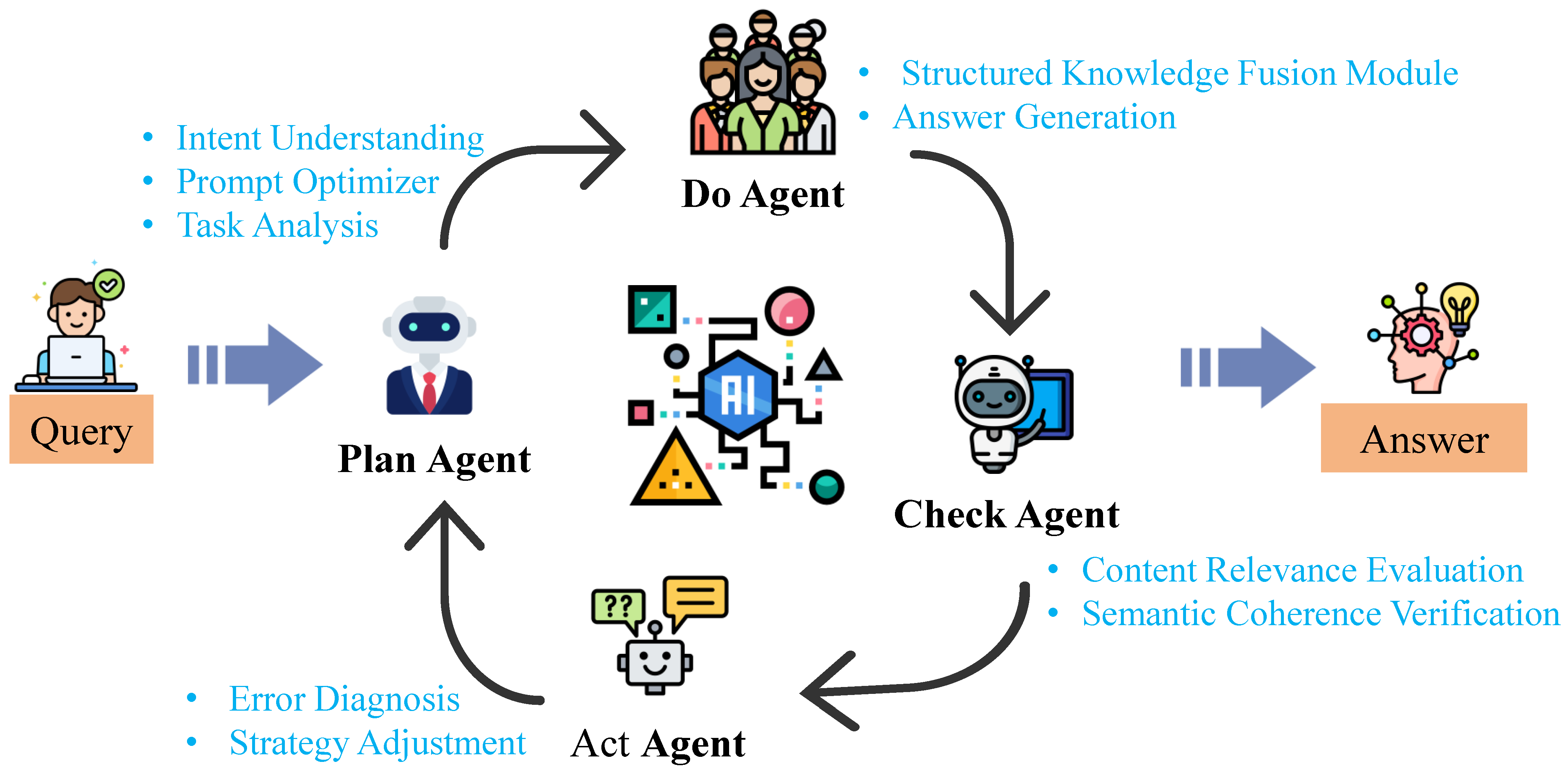

- We present a PDCA-inspired multi-agent RAG architecture that introduces quality-control principles into semantic QA, endowing the system with self-perception, self-evaluation, and self-correction, thus maintaining stability and controllability under multi-turn dialogue and dynamic scenarios.

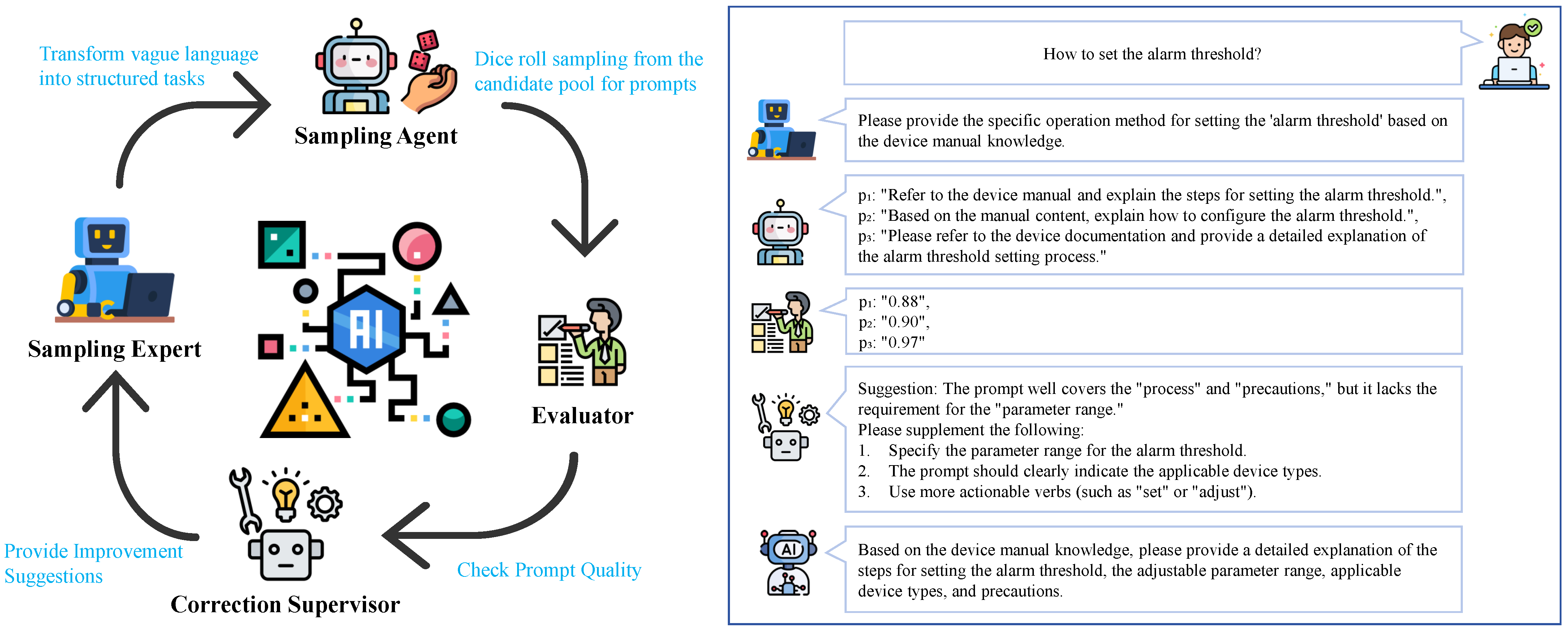

- We develop a dynamic prompt reconfiguration algorithm that combines semantics-driven guidance with Monte Carlo sampling; by steering prompt reconstruction using task goals and user intent, it alleviates semantic drift induced by fixed templates.

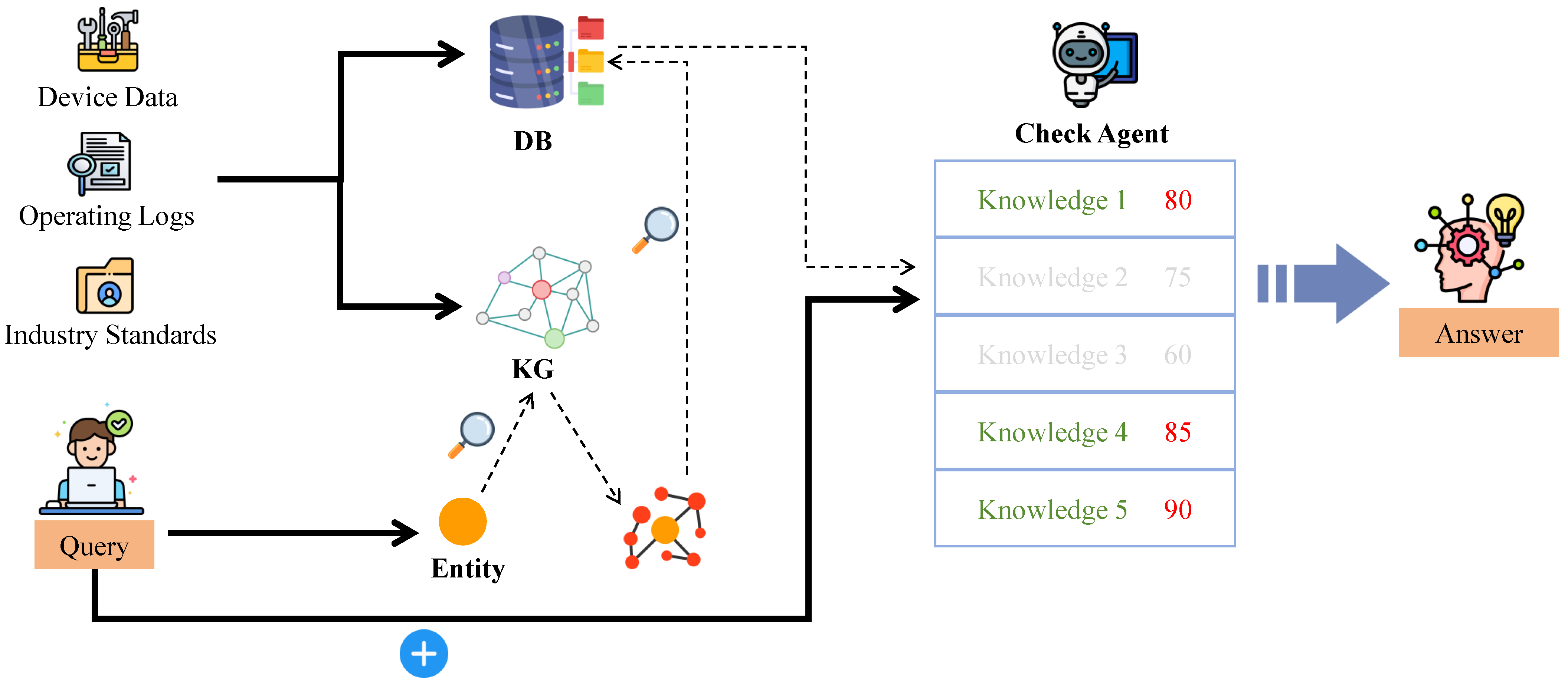

- We design a heterogeneous knowledge fusion module that integrates knowledge-graph reasoning, semantic vector enhancement, and context compression to achieve unified semantic modeling of structured and unstructured knowledge, thereby improving information coverage, content consistency, and reasoning depth.

2. Related Work

2.1. Domain Characteristics and System Requirements of Smart Building Semantic Question Answering

- (1)

- Knowledge heterogeneity and incoAfter checking, the bold formatting has been removed, and the following text has also been revised accordingly.nsistent granularity: structured BIM/ontology/device graphs coexist with unstructured manuals, logs, and standards, making retrieval and semantic alignment difficult [5,17,18];

- (2)

- (3)

2.2. Application Potential and Boundaries of LLM in Smart Building Question Answering

2.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Paradigm for Smart Buildings

2.4. Multi-Stage Reasoning, Reflective Error Correction, and In-Task Closed-Loop RAG

2.5. Multi-Agent Collaborative RAG and Building Task Control

2.6. Prompt Adaptivity and Dynamic Construction Mechanisms

2.7. Research Gap and Positioning of This Paper

3. Methodology

- (1)

- Adaptive prompt optimization, which treats prompts as evolvable structures and improves alignment between generation instructions and task requirements via semantic decomposition and evaluation-driven refinement;

- (2)

- Heterogeneous knowledge fusion, which integrates textual vector semantics with structured building knowledge so that retrieved evidence is both more relevant and more useful for reasoning.

3.1. Theoretical Foundation: Semantic Closed-Loop Model

3.2. PDCA Multi-Agent Collaborative Architecture

3.2.1. Plan Agent: Intent Modeling and Structured Task Planning

3.2.2. Do Agent: Evidence Retrieval, Integration, and Initial Generation

3.2.3. Check Agent: Evaluation of Retrieval and Answer Quality

3.2.4. Act Agent: Attribution Analysis and Optimization Feedback

3.3. Adaptive Prompt Optimization Mechanism Based on Monte Carlo Methods

3.3.1. Semantic Modeling Perspective of Prompt Optimization

3.3.2. Monte Carlo-Based Semantic Neighborhood Exploration

- Semantic preservation: perturbations operate on surface form while keeping core meaning unchanged;

- Structural diversity: different operators yield prompts with varied structures, allowing the Plan Agent to explore improved task formulations.

3.3.3. Prompt Quality Function and Selection Criteria

3.3.4. Module Role and Closed-Loop Consistency

- Non-loop component: participates only in the Plan stage and does not alter the PDCA convergence path;

- No semantic feedback: uses neither Check’s deviation signal nor Act’s update mechanism;

- One-shot optimization: Monte Carlo sampling is executed once, without forming a multi-round loop;

- Stabilized initialization: it improves the initialization quality of .

3.4. Heterogeneous Knowledge Expansion and Fusion Mechanism for Smart Buildings

3.4.1. Necessity and Design Principles of Unified Representation

- (1)

- Semantic preservation: descriptive text should retain key entities, states, and operational meanings;

- (2)

- Structural dependence: BIM-graph nodes should retain functional relations among devices and spatial containment relations;

- (3)

- Comparability: all sources must ultimately be scoreable and selectable within the same vector space.

3.4.2. Knowledge Graph-Based Related-Entity Expansion

3.4.3. Multi-Dimensional Knowledge Scoring and Fusion Strategy

- (1)

- Semantic relevance measures content matching between a candidate and the user query, using text embeddings to assess whether relevant devices, states, or concepts are mentioned.

- (2)

- Structural consistency assesses whether a candidate is topologically close and functionally dependent on the core task entities; candidates far along the device chain or with weak functional ties receive lower scores. This avoids evidence that is semantically similar yet physically/functionally invalid, which can induce structure-level hallucinations.

- (3)

- Task alignment checks whether a candidate supports the Plan Agent’s task structure—for example, whether it provides needed parameters, enables causal explanation, or can serve as an evidence snippet.

3.4.4. Role in the PDCA Closed Loop and Contribution to Stability

3.5. System Integration and Overall Workflow

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

- RQ1:

- Under an identical knowledge base and dataset configuration, does LoopRAG outperform mainstream RAG variants overall?

- RQ2:

- Does the PDCA closed-loop feedback mechanism substantially enhance system stability and task completion?

- RQ3:

- To what extent does the Monte Carlo Prompt Optimization (MCPO) mechanism improve semantic alignment and answer quality?

- RQ4:

- Compared with purely vector-based retrieval, does the smart building H-KEFM yield clear gains in retrieval quality and answer trustworthiness?

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets and Task Types

- Factual QA tasks: target clearly defined low-carbon energy knowledge, e.g., “What is the principle of solar photovoltaic power generation?” and “Is wind energy renewable?”, where answers are deterministic facts.

- Explanatory QA tasks: require causal reasoning and deeper explanation of concepts or technologies, e.g., “Why is nuclear energy important in low-carbon energy?” and “What are the key technologies for bioethanol production?”

- Comparative QA tasks: probe analytical capability through multi-dimensional comparisons of technologies or policy options, e.g., “How do solar and wind power differ in generation efficiency?” and “What are the pros and cons of nuclear energy versus hydropower?”

- Predictive QA tasks: involve forecasting and judgment of future trends, e.g., “What is the outlook for hydrogen energy in transportation over the next decade?” and “How will the cost of solar power generation evolve?”

4.1.2. Knowledge Base and Heterogeneous Data

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Context Recall: whether answers sufficiently leverage retrieved key context.

- Relevance: semantic alignment between system output and reference answers.

- Faithfulness/Factual consistency: whether generated content is supported by correct semantics, mitigating hallucinations.

- Avg Retrieved Tokens: the amount of retrieved context consumed, reflecting dependence on external evidence.

- Accuracy: whether the final output matches the gold answer.

4.1.4. Experimental Environment and Implementation Details

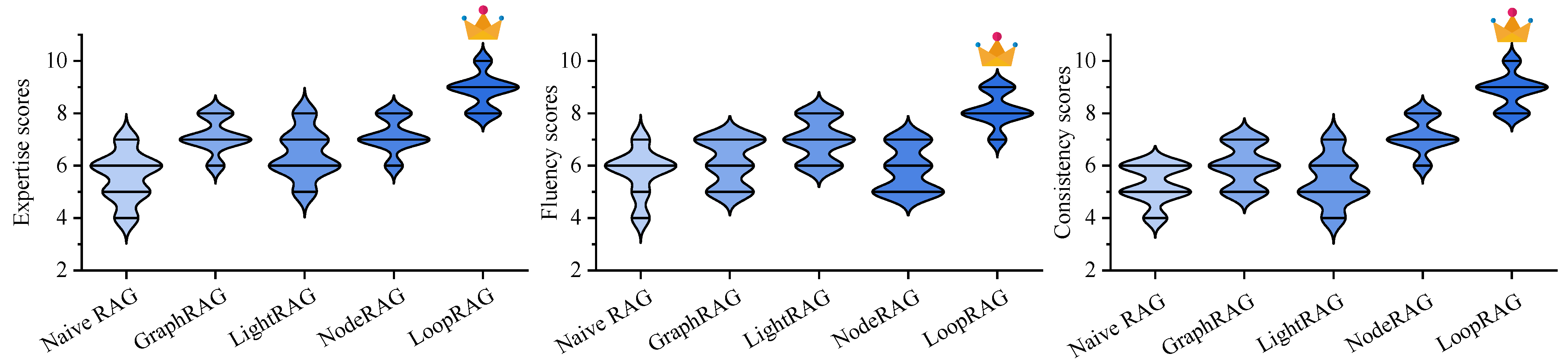

4.2. Overall Performance Comparison

4.3. Impact of the PDCA Closed-Loop Mechanism

4.4. Impact of the Dynamic Prompt Optimization Module (MCPO)

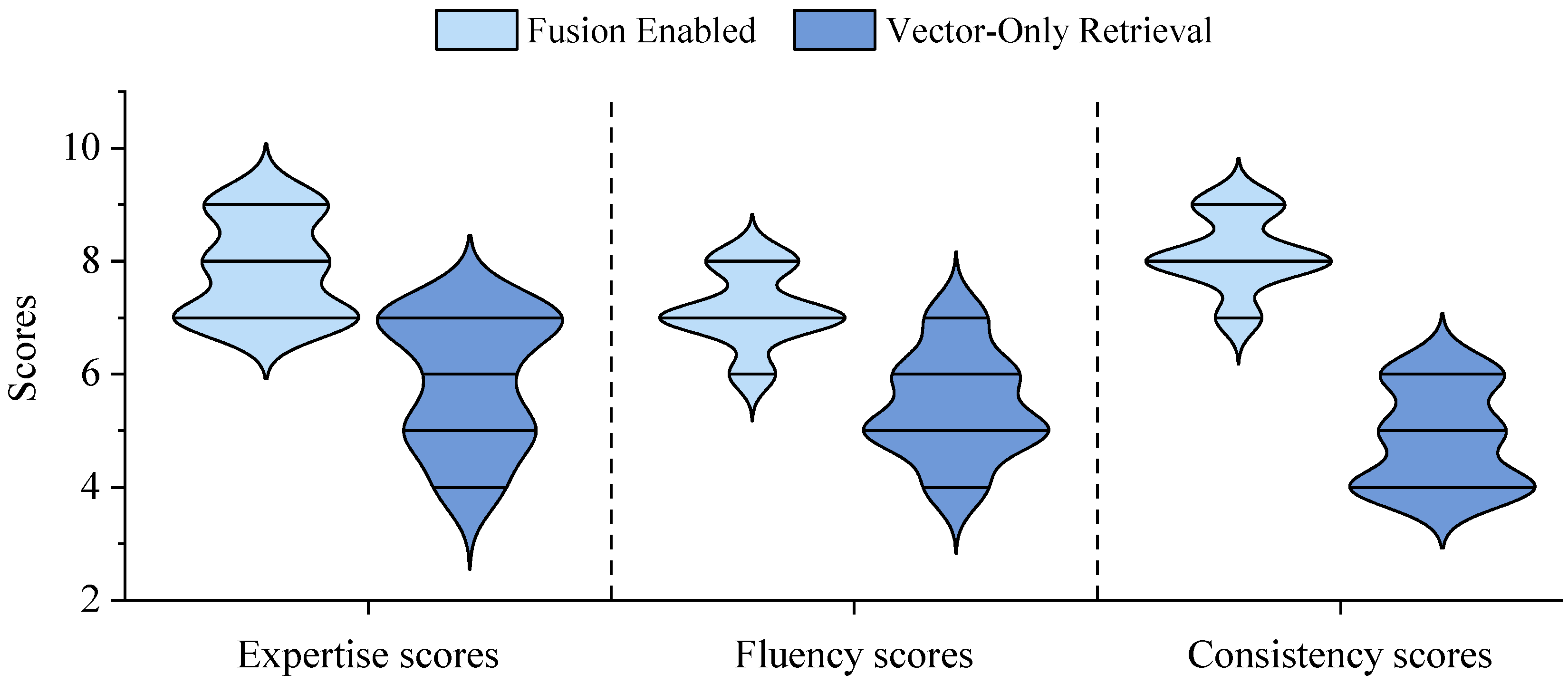

4.5. Impact of the Heterogeneous Knowledge Fusion Mechanism

4.6. Summary and Discussion

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| QA | Question Answering |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| PDCA | Plan–Do–Check–Act |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| LLaMA | Large Language Model Meta AI |

| KG | Knowledge Graph |

| MCPO | Monte Carlo Prompt Optimization |

| H-KEFM | Heterogeneous Knowledge Expansion and Fusion Mechanism |

| Symbol | Description |

| t | Index of interaction or closed-loop iteration step |

| User input at iteration t | |

| Generated answer at iteration t | |

| Internal semantic state of the system at iteration t | |

| User intent representation (task type, entities, constraints) | |

| Retrieved knowledge/evidence state at iteration t | |

| Prompt and generation strategy configuration | |

| Global heterogeneous knowledge base | |

| Generation and reasoning function parameterized by | |

| Quality evaluation mapping function | |

| State update function in the semantic closed loop | |

| Evaluation feedback signal at iteration t | |

| Composite deviation loss at iteration t | |

| Parameter sete set of the closed-loop reasoning system | |

| Planning function (Plan Agent) | |

| Execution and retrieval function (Do Agent) | |

| Quality checking function (Check Agent) | |

| Policy update and correction function (Act Agent) | |

| Structured task plan generated by the Plan Agent | |

| Weights for semantic alignment, faithfulness, and constraint losses | |

| Step size for state adjustment at iteration t | |

| Semantic embedding function | |

| Cosine similarity between embeddings | |

| Indicator of whether retrieved evidence i supports the answer | |

| K | Number of retrieved evidence items (Top-K retrieval) |

| Constraint satisfaction function for generated output | |

| Prompt space | |

| Semantic neighborhood of prompts around input | |

| Prompt perturbation or rewriting operator | |

| k-th sampled prompt candidate | |

| Prompt quality evaluation function | |

| Weights of prompt quality components |

References

- Duarte, C.; Carrilho, J.; Vale, Z. Natural language interfaces for smart buildings: A systematic review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107312. [Google Scholar]

- Es, S.; James, J.; Espinosa-Anke, L.; Schockaert, S. RAGAs: Automated evaluation of retrieval augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations (EACL 2024), St. Julian’s, Malta, 17–22 March 2024; pp. 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.-A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LlaMA: Open and efficient foundation language models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2023), Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; Li, H. Natural-language-driven BIM information retrieval for construction and facility management. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 48, 101276. [Google Scholar]

- Gemini Team. Gemini: A family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cui, B. Retrieval-augmented generation for AI-generated content: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.-T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, S.; Anagnostopoulos, A.V.; Bello, S.M.; Blumberg, K.; Cameron, R.; Carmody, L.; Diehl, A.D.; Dooley, D.M.; Duncan, W.D.; Fey, P.; et al. Dynamic retrieval augmented generation of ontologies using artificial intelligence (DRAGON-AI). J. Biomed. Semant. 2024, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakka, C.; Shad, R.; Chaurasia, A.; Dalal, A.R.; Kim, J.L.; Moor, M.; Fong, R.; Phillips, C.; Alexander, K.L.; Ashley, E.A.; et al. Almanac—Retrieval-augmented language models for clinical medicine. NEJM AI 2024, 1, AIoa2300068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Lu, L.; Liu, M.; Song, C.; Wu, L. Nanjing Yunjin intelligent question-answering system based on knowledge graphs and retrieval augmented generation technology. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Tang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q. A ReAct-based intelligent agent framework for ambient control in smart buildings. Sensors 2024, 24, 2517. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2021), Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 3045–3059. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (ACL-IJCNLP 2021), Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 4582–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, J.; Singh, P.; Litombe, N.; Larson, J.; Trinh, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mueller, A.; Psallidas, F.; Curino, C. Optimizing open-domain question answering with graph-based retrieval augmented generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.02922. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, W.; Xue, F.; Webster, C. BIM-based question answering for facility management: A review and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104319. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Zhong, B.; Ding, L. Ontology-driven semantic question answering for smart buildings: A review. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109184. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Hong, T.; Jeong, K.; Lee, M. Conversational interfaces for HVAC control using deep NLP: A multi-zone case study. Energy Build. 2021, 250, 111294. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, A.; Forcada, N.; Serrat, C. Natural language processing–enabled interactions in IoT-based smart buildings: A framework and case study. Autom. Constr. 2023, 149, 104799. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, M.; Ren, H.; Bosselut, A.; Liang, P.; Leskovec, J. QA-GNN: Reasoning with language models and knowledge graphs for question answering. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL 2021), Online, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Chen, X.; Dong, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, G.; Yu, L.; Yu, Y. Multi-hop knowledge graph question answering method based on query graph optimization. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–16 February 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Basart, S.; Zou, A.; Mazeika, M.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Press, O.; Zhang, M.; Min, S.; Schmidt, L.; Smith, N.A.; Lewis, M. Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 5687–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpukhin, V.; Oguz, B.; Min, S.; Lewis, P.; Wu, L.; Edunov, S.; Chen, D.; Yih, W. Dense passage retrieval for open-domain question answering. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2020), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 6769–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izacard, G.; Grave, E. Leveraging passage retrieval with generative models for open domain question answering. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume (EACL 2021), Online, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, F.; Gao, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Active retrieval augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2023), Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 7969–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shen, Y.; Huang, M.; Duan, N.; Chen, W. Enhancing retrieval-augmented large language models with iterative retrieval-generation synergy. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 9248–9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, J.; Tomczak, J.M. Knowledge graph-extended retrieval augmented generation for question answering. Appl. Intell. 2025, 55, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Schärli, N.; Hou, L.; Wei, J.; Scales, N.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Cui, C.; Bousquet, O.; Le, Q.; et al. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khot, T.; Trivedi, H.; Finlayson, M.; Fu, Y.; Richardson, K.; Clark, P.; Sabharwal, A. Decomposed prompting for multi-hop reasoning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Asai, A.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sil, A.; Hajishirzi, H. SELF-RAG: Learning to retrieve, generate, and critique through self-reflection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y. CRITIC: Large language models can self-correct with tool-interactive critique. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, A.; Tandon, N.; Gupta, P.; Hallinan, S.; Gao, L.; Wiegreffe, S.; Alon, U.; Dziri, N.; Prabhumoye, S.; Yang, Y.; et al. Self-Refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023), Conference Proceedings, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, N.; Cassano, F.; Berman, E.; Gopinath, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Yao, S. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Zhuge, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yau, S.K.S.; Lin, Z.; et al. MetaGPT: Meta programming for a multi-agent collaborative framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.S.; O’Brien, J.C.; Cai, C.J.; Morris, M.R.; Liang, P.; Bernstein, M.S. Generative agents: Interactive simulacra of human behavior. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST ’23), San Francisco, CA, USA, 29 October–1 November 2023; pp. 2:1–2:22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. AutoGen: Enabling next-gen LLM applications via multi-agent conversation. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2024 Workshop on LLM Agents, Vienna, Austria, 11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Ji, K.; Fu, Y.; Tam, W.L.; Du, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. P-Tuning: Prompt tuning can be comparable to fine-tuning universally across scales and tasks. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Razeghi, Y.; Logan, R.L., IV; Wallace, E.; Singh, S. AutoPrompt: Eliciting knowledge from language models with automatically generated prompts. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2020), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 4222–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Nie, S.; Wang, S.; Feng, F.; Huang, L.; Quan, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. APrompt: Attention prompt tuning for efficient adaptation of pre-trained language models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2023), Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 9147–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.; Torr, P.H.S.; Bibi, A. When Do Prompting and Prefix-Tuning Work? A Theory of Capabilities and Limitations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, G.; Nakayiza, H.; Jjingo, D.; Nakatumba-Nabende, J. Prompt engineering in large language models. In Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics; Jacob, I.J., Piramuthu, S., Falkowski-Gilski, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 387–402. ISBN 978-981-99-7962-2. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Type | Usage Description |

|---|---|---|

| HotpotQA | Multi-hop QA | Assess multi-paragraph semantic composition. |

| MuSiQue | Synthetic multi-hop tasks | Test adaptability to structured complex tasks. |

| MultiHop-RAG | Multi-document reasoning | Evaluate cross-document retrieval and semantic aggregation. |

| RAG-QAArena | Multi-turn conversational QA | Measure context retention and historical coherence. |

| Building QA | Multi-type QA tasks | validating generalization and controllability in practical settings. |

| Model | Context Recall | Response Relevance | Faithfulness | Avg Retrieved Tokens | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive RAG | 75% | 58% | 50% | 1096 | 64% |

| GraphRAG | 34% | 54% | 45% | 694 | 69% |

| LightRAG | 81% | 62% | 87% | 978 | 61% |

| NodeRAG | 85% | 61% | 74% | 1004 | 66% |

| LoopRAG | 90% | 72% | 87% | 3046 | 88% |

| Metric | With Feedback Loop | Without Feedback | Relative Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Recall | 90% | 86% | ↓ 4% |

| Response Relevance | 72% | 67% | |

| Faithfulness | 87% | 89% | |

| Avg Retrieved Tokens | 3046 | 2325 | |

| Accuracy | 88% | 71% |

| Metric | With Prompt Optimization | Without MCPO | Relative Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Recall | 90% | 85% | ↓ 5% |

| Response Relevance | 72% | 63% | |

| Faithfulness | 87% | 86% | |

| Avg Retrieved Tokens | 3046 | 1132 | |

| Accuracy | 88% | 68% |

| Metric | Fusion Enabled | Vector-Only Retrieval | Relative Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Recall | 90% | 75% | ↓ 15% |

| Response Relevance | 72% | 58% | |

| Faithfulness | 87% | 50% | |

| Avg Retrieved Tokens | 3046 | 1096 | |

| Accuracy | 88% | 64% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, J.; Ning, D.; You, Y.; Chen, J. LoopRAG: A Closed-Loop Multi-Agent RAG Framework for Interactive Semantic Question Answering in Smart Buildings. Buildings 2026, 16, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010196

Bai J, Ning D, You Y, Chen J. LoopRAG: A Closed-Loop Multi-Agent RAG Framework for Interactive Semantic Question Answering in Smart Buildings. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010196

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Junqi, Dejun Ning, Yuxuan You, and Jiyan Chen. 2026. "LoopRAG: A Closed-Loop Multi-Agent RAG Framework for Interactive Semantic Question Answering in Smart Buildings" Buildings 16, no. 1: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010196

APA StyleBai, J., Ning, D., You, Y., & Chen, J. (2026). LoopRAG: A Closed-Loop Multi-Agent RAG Framework for Interactive Semantic Question Answering in Smart Buildings. Buildings, 16(1), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010196