Interactions Between Objective and Subjective Built Environments in Promoting Leisure Physical Activities: A Case Study of Urban Regeneration Streets in Beijing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

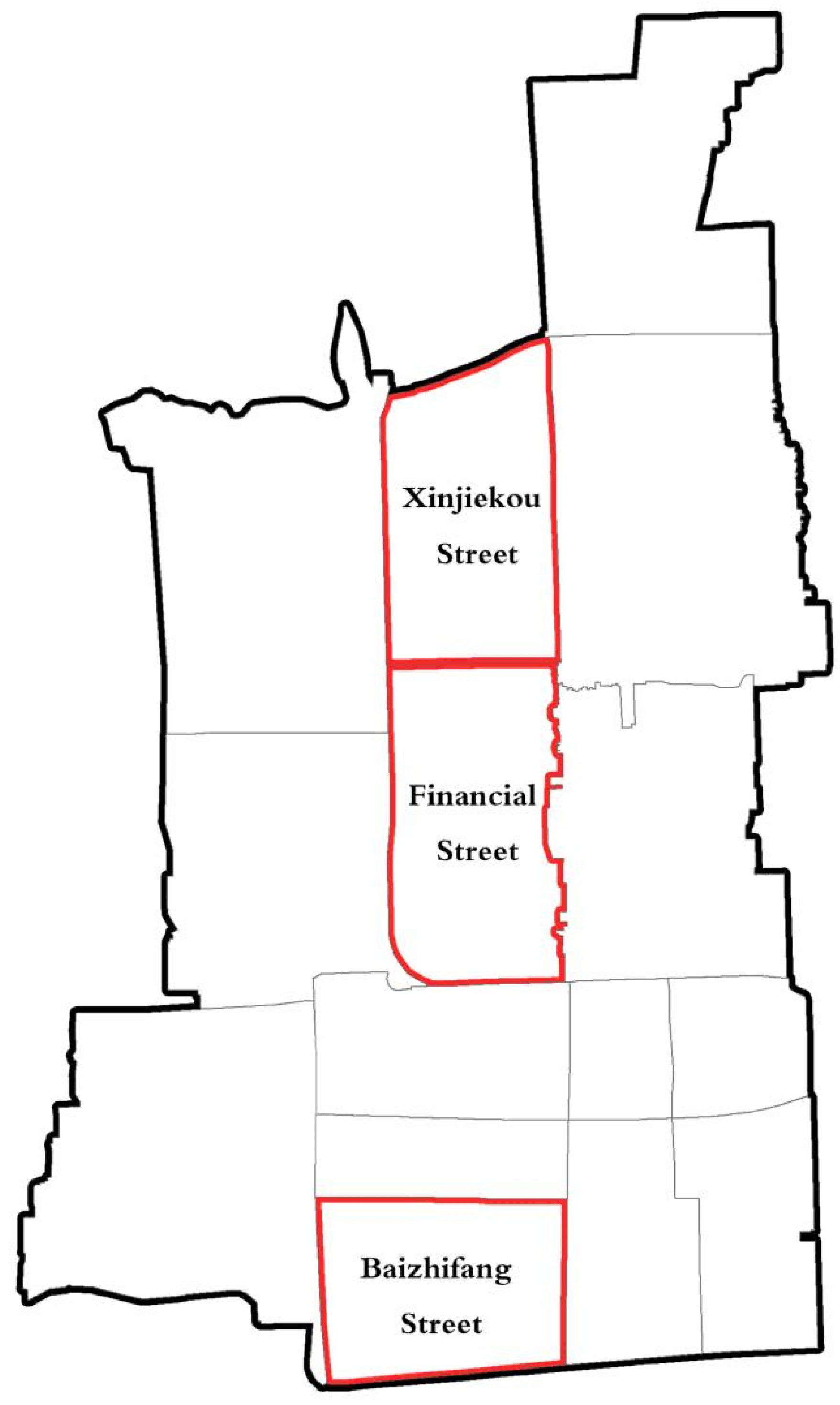

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Selection of Objective and Subjective Built Environment Variables

2.3. Data Collection

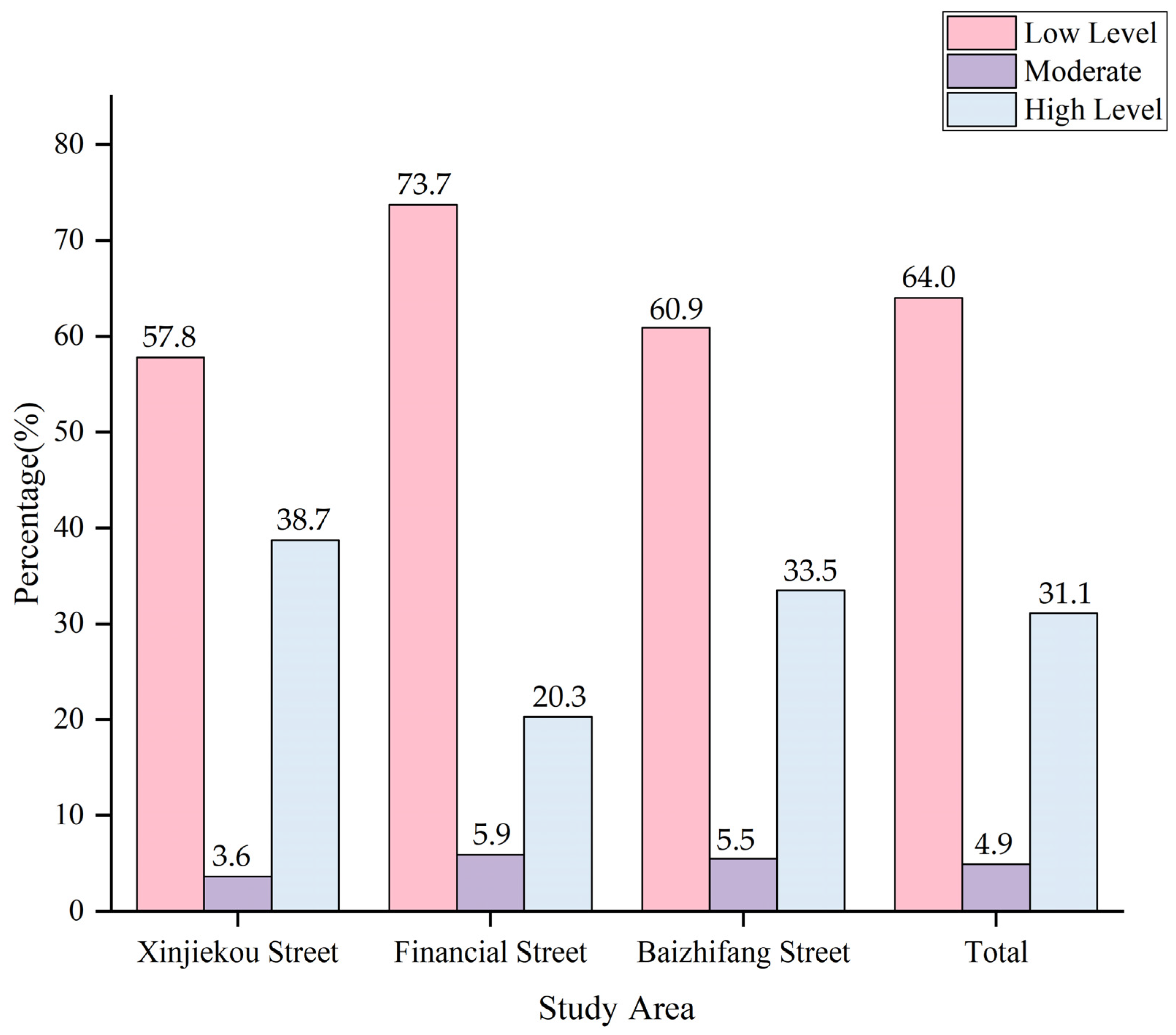

2.4. Leisure Physical Activity Data

2.5. Subjective Built Environment Data

2.6. Objective Built Environment Data—Facility Accessibility

Data Collection Method

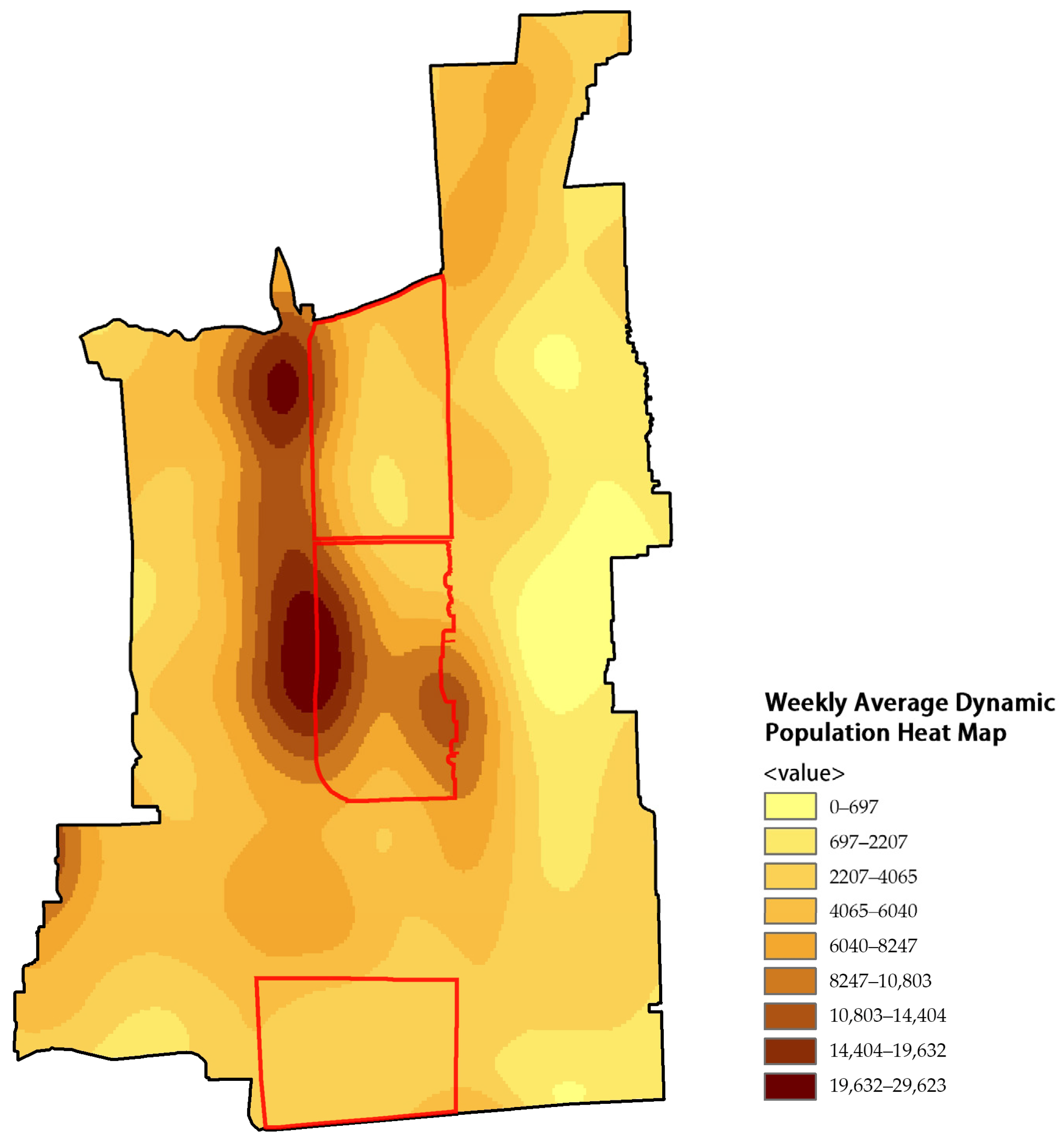

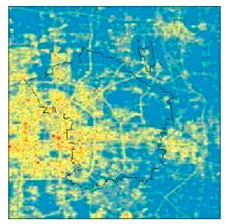

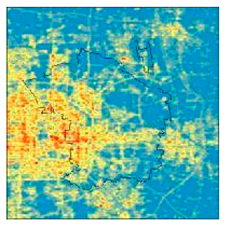

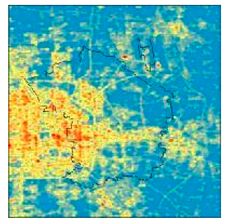

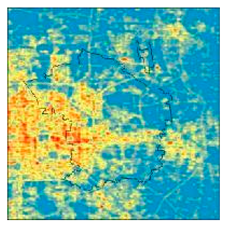

- Dynamic Population Density Data Collection;

- 2.

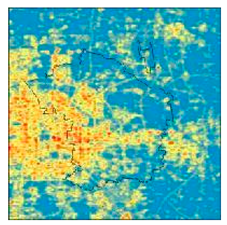

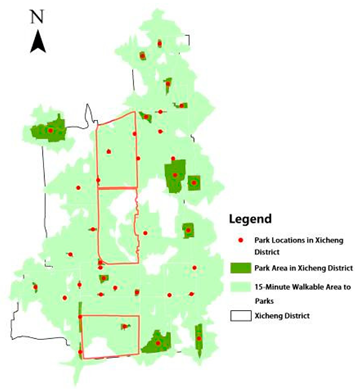

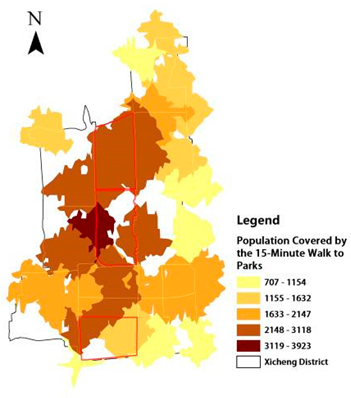

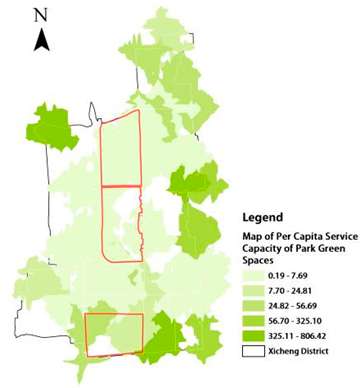

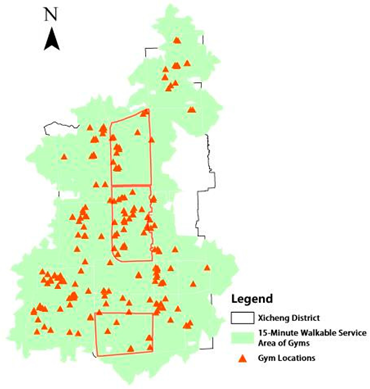

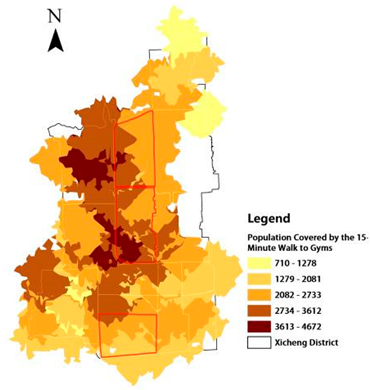

- Service Capacity of Leisure Facilities;

- 3.

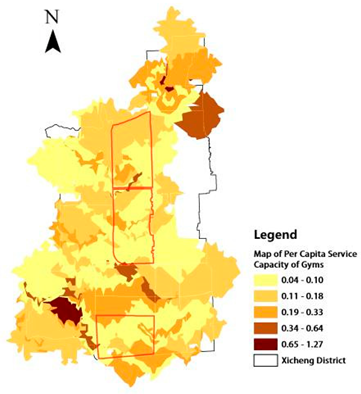

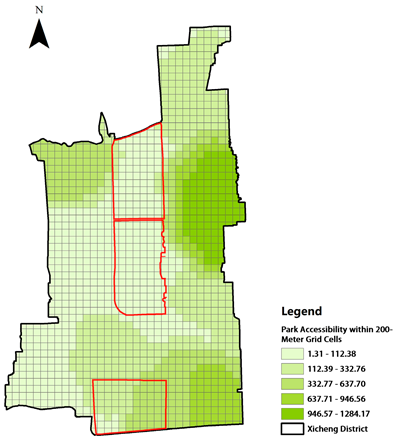

- Accessibility Calculation;

- The first step is to calculate the supply-demand ratio of facilities, that is, the service capacity of the facilities. This step has been explained in the previous section.

- The second step is to calculate the accessibility of each grid’s centroid. This calculation still requires network analysis. The study employs a point-based method, where the accessibility of a point is expressed by calculating the total per capita service capacity of leisure facilities within the range of the centroid. The calculation formula is shown in Equation (3):

- In the equation, represents the accessibility of leisure facilities at centroid . The larger the value of , the better the accessibility of leisure facilities at that point. represents the path distance between centroid i and facility , while represents the maximum walking distance threshold. Parks beyond this threshold do not influence the accessibility of the service point. is the Gaussian decay function, which models the decreasing service capacity of leisure facilities as the distance from the service point increases.

- The calculation method of the Gaussian function is shown in Equation (4):

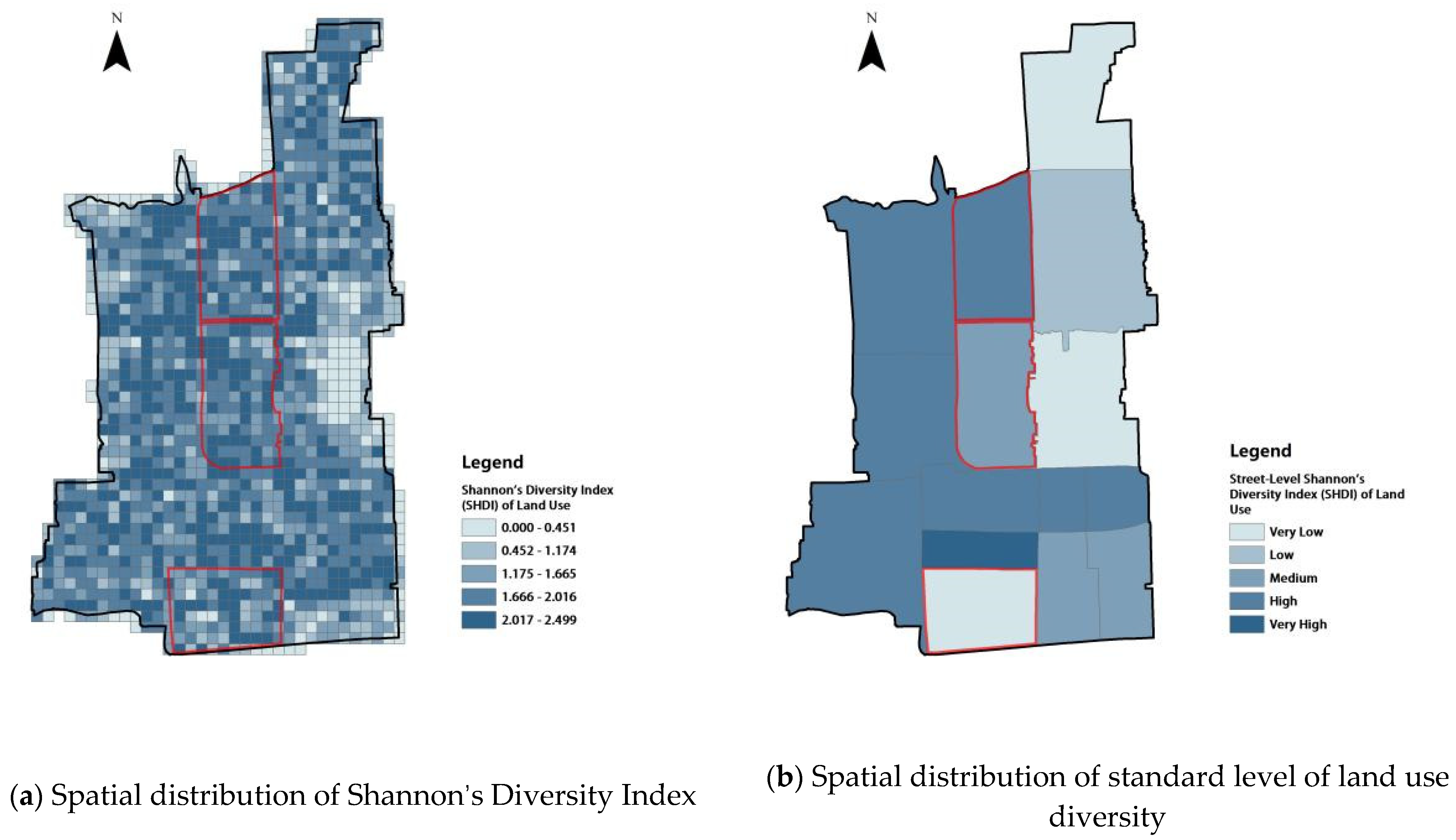

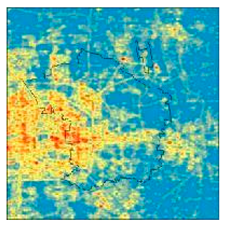

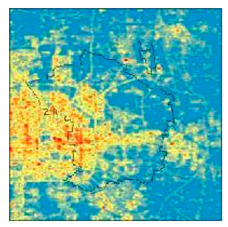

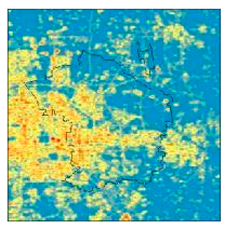

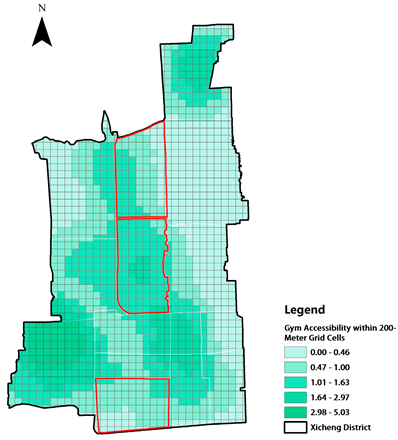

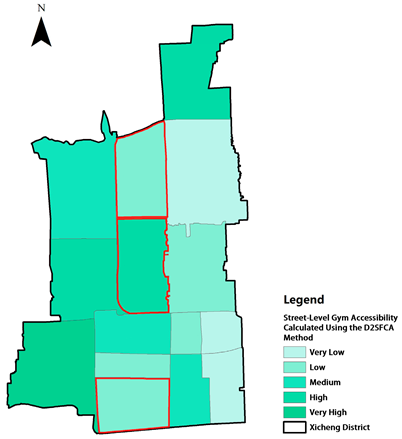

- Subsequently, the Jenks natural breaks classification method was applied to categorize the accessibility of each sampling point, thereby dividing the accessibility levels of public facilities across the study area into five classes. The accessibility values were visualized on a 200 m fishnet grid, where color gradients were used to represent different levels of accessibility.

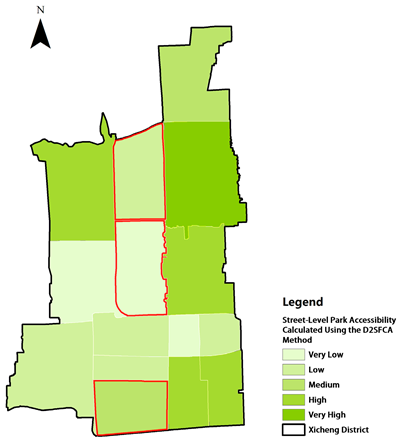

- To more intuitively illustrate spatial variations within the study area, the grid map was further processed using kernel density estimation (KDE) to generate a heatmap depicting the spatial distribution of accessibility. Based on administrative boundaries, the mean accessibility values derived from the kernel density map were then calculated for each sub-district. These mean values were classified into five categories—very low, low, moderate, high, and very high—using the natural breaks method. This approach minimizes the influence of differences in population size or land area between the two types of recreational facilities, ensuring that the results are comparable across the study area.

- As shown in Table 10, the results reveal that within the study area, Baizhifang Sub-district demonstrates the highest level of accessibility to parks and open spaces, whereas Financial Street Sub-district exhibits the lowest. In contrast, the accessibility to gyms shows an almost opposite pattern, indicating a complementary spatial relationship in the demand for these two types of recreational facilities.

- The computed accessibility results correspond well with the actual conditions of the three sub-districts, particularly regarding the number of parks, green spaces, and gyms, as well as their per capita service capacity. This consistency suggests that the accessibility evaluation framework effectively reflects the real-world distribution and utilization of recreational resources within the urban area.

2.7. Objective Built Environment Data—Development Intensity

2.7.1. Method of Land Use Mix Analysis

2.7.2. Other Indicators of Development Intensity

3. Results

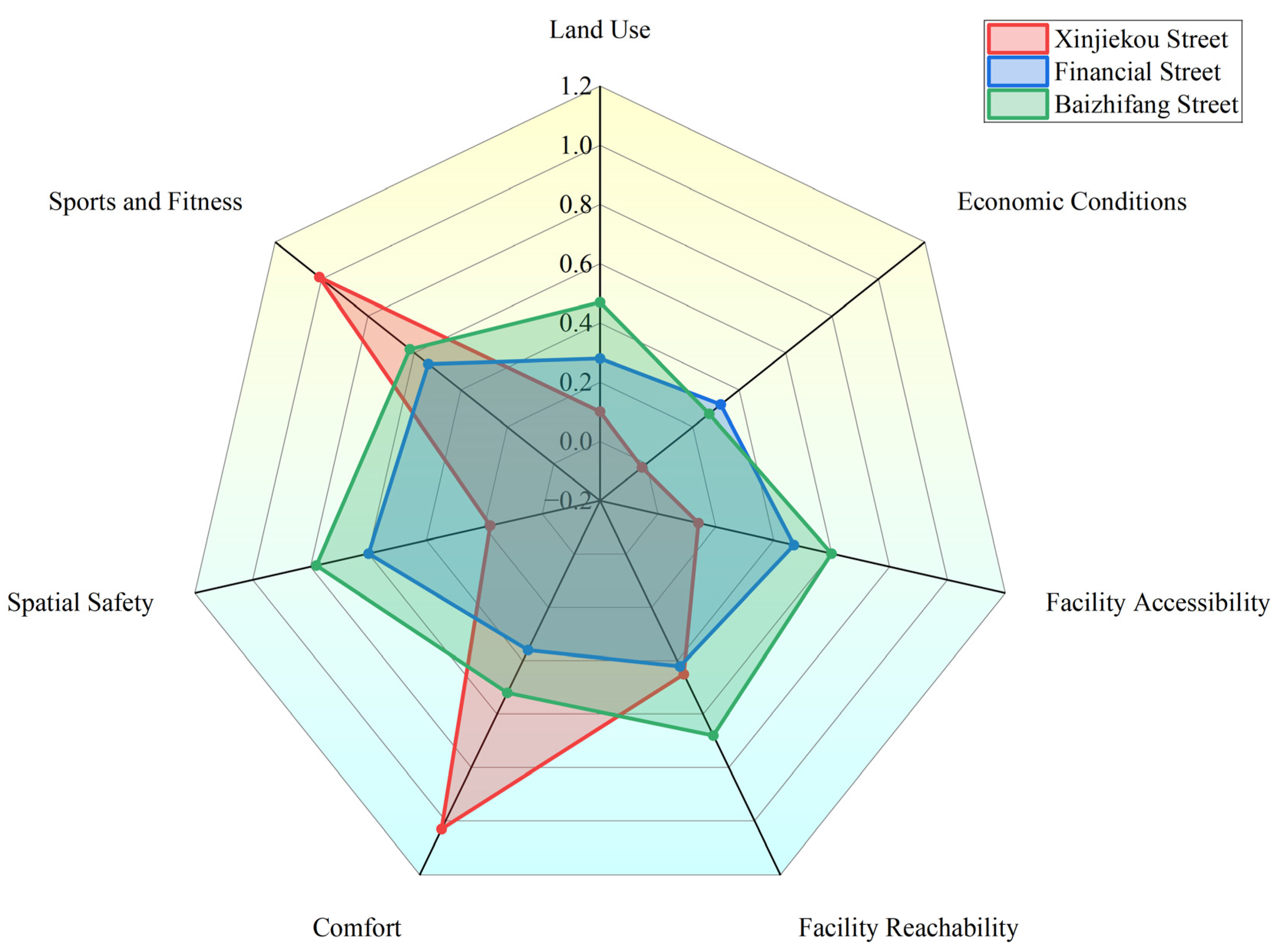

3.1. Correlation Between Subjective Built Environment and Leisure Physical Activity

3.2. Correlation Between Objective Built Environment and Leisure Physical Activity

3.2.1. Accessibility of Leisure Facilities

3.2.2. Development Intensity

3.2.3. Public Transportation

3.2.4. Integrated Analysis of Objective Built Environment Variables

3.3. Correlation Between Socioeconomic Attributes and Leisure Physical Activity

3.3.1. Education Level

3.3.2. Income Level

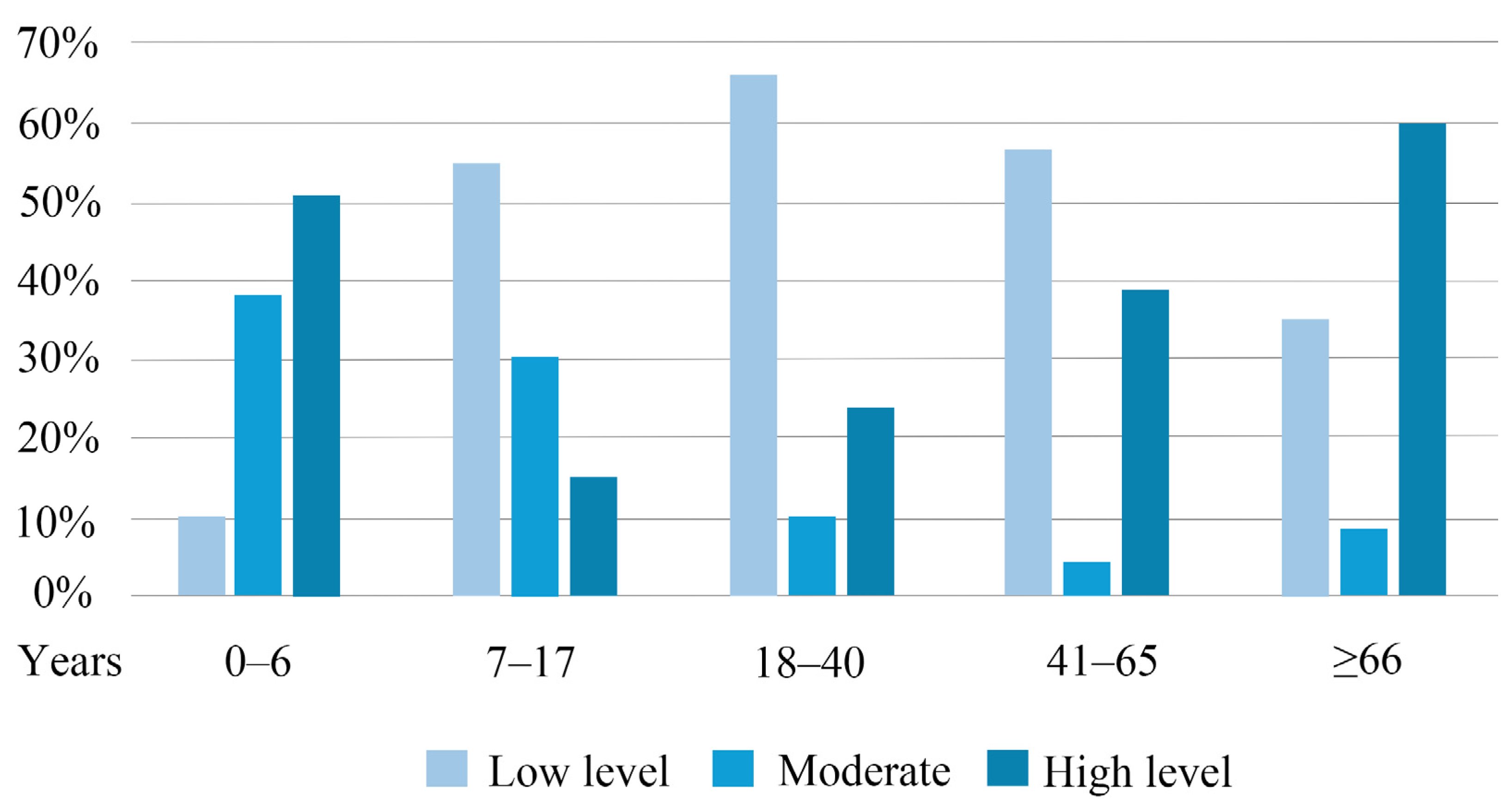

3.3.3. Age

4. Discussion

- Residents’ subjective perception of the environment modifies their responses to spontaneous physical activity through cognitive evaluation. Satisfaction with the perceived built environment significantly influences willingness to engage in physical activity and can reinforce the facilitating effect of the objective environment. Key dimensions include safety (e.g., nighttime lighting, public security), accessibility (e.g., whether a park is reachable within a 15 min walk), and attractiveness (e.g., quality of greenery, street cleanliness). Among these factors, improvement in satisfaction with attractiveness exerts the most direct effect on promoting exercise. Residents’ subjective perceptions serve as a key mediating factor in the development of healthy cities. Safety and attractiveness enhance psychological comfort, thereby encouraging spontaneous physical activity. These findings suggest that street-level physical environment improvements should be implemented in tandem with perception optimization.

- The objective environment shapes opportunities for basic physical activity. Accessibility to open spaces, land use mix, and the number of bus stops—all components of the objective built environment—positively facilitate leisure physical activity. However, excessively high urban density (e.g., areas with dense high-rise residential buildings) may inhibit residents’ motivation to go outdoors due to feelings of spatial compression and reduced sense of safety. Among these factors, the positive effect of accessibility to recreational facilities is the most pronounced, indicating that residents are more likely to engage in exercise using conveniently located facilities along their daily activity routes.

- Socioeconomic characteristics play a fundamental role in shaping residents’ physical activity. Indicators such as income, age, and educational level predominantly influence behavioral choices. High-income individuals can indirectly increase their activity frequency by selecting higher-quality communities. Older adults exhibit the highest willingness to engage in physical activity due to health needs, whereas middle-aged individuals show the lowest willingness, largely due to time constraints.

- The promotion of physical activity among residents in urban neighborhoods exhibits a three-dimensional driving pattern: “constraints imposed by the objective environment—modifications by subjective perception—determination by socioeconomic resources.” The study further indicates that, after controlling for subjective environmental variables, the effects of the objective built environment are largely more pronounced. Both factors show partial correlation yet independently influence leisure physical activity. From Model 1 to Model 2, the inclusion of objective built environment variables increases the relative explanatory power for leisure physical activity by (0.735 − 0.695)/0.695= 5.8%. From Model 2 to Model 3, the addition of subjective built environment variables increases the relative explanatory power by (0.748 − 0.735)/0.735=1.8%. The slight change in Nagelkerke R2 indicates that, compared to the subjective built environment, the objective built environment more directly affects opportunities for activity (1.8% < 5.8%). In summary, residents’ socioeconomic attributes determine the baseline of their leisure physical activity habits; the objective environment can directly influence the level of their activity, whereas the subjective built environment serves to modify the effects of objective variables.

- Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference regarding environment-behavior relationships. Second, while the spatial grid sampling approach ensured geographic coverage, the recruitment of respondents at leisure activity locations—with priority given to residents currently engaging in or having just completed physical activities—may have introduced selection bias toward more physically active individuals. This recruitment strategy was necessary to ensure respondents had direct experience with neighborhood physical activity environments, but may limit generalizability to less active population segments. Third, although the IPAQ is a well-validated instrument and the subjective built environment items were adapted from established scales, this study did not conduct a formal pilot study or reliability assessment (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) for the current sample. Future research should consider longitudinal designs, probability-based sampling methods, and comprehensive psychometric testing to strengthen the robustness of findings.

4.1. Parallels Between Objective and Subjective Indicators Across Neighborhoods

4.2. Implications for Context-Sensitive Urban Regeneration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Integrating Health in Urban and Territorial Planning: A Sourcebook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003170 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. “Healthy China 2030” Planning Outline. (2016-10). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on Issuing the Implementation Plan of the “Year of Weight Management” Activity (Guo Wei Yi Ji Fa [2024] No. 21). (2024-06). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202406/content_6959543.htm (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Dang, X.; Hong, Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. China’s Heritage Governance Blueprint: Revisiting Evolutionary Trajectories, Reframing Institutional Priorities and Mapping the National Registry. Habitat Int. 2025, 165, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Fan, Y. Exploring the Influences of Density on Travel Behavior Using Propensity Score Matching. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2012, 39, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qiu, X. Research and Enlightenment of the U.S. National Physical Activity Plan. Sports Cult. Guide 2016, 27–30+41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Glass, T.A.; Curriero, F.C.; Stewart, W.F.; Schwartz, B.S. The Built Environment and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence. Health Place 2010, 16, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yue, J.; Liu, W. Characteristics, Effects, and Implications of the Irish “National Physical Activity Plan”. Sports Cult. Guide 2019, 40–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Song, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, L. The Influence of Urban Built Environment on Elderly Health: Model Verification with Physical Activity as Mediator. China Sport Sci. 2019, 55, 41–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Huang, X.; Tang, S. Mechanisms of Objective and Subjective Built Environment Influences on Different Physical Activities of Older Adults: A Case Study in Nanjing. Shanghai Urban Plan. 2017, 17–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; He, X. Influence of the Built Environment on Transport-Related Physical Activity: A Research Progress Overview. Sports Sci. 2014, 35, 41–45+40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Municipal Government. Capital Functional Core Area Regulatory Detailed Plan (Block Level) (2018–2035). (2020-08). Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/202008/t20200828_1992592.html (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census of Beijing. (2021-05). Available online: https://tjj.beijing.gov.cn/tjsj_31433/sjjd_31444/202105/t20210519_2392526.html (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Xu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, T.; Wang, Z.; Fang, Y.; Huang, X. Exploring the Impact of Objective Features and Subjective Perceptions of Street Environment on Cycling Preferences. Cities 2026, 168, 106434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Zhai, G. Influence of Built Environment on Residents’ Physical Activity in Small Cities: A Case Study in Ganyu, Jiangsu. Urban Reg. Plan. Res. 2020, 12, 155–171. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Yang, J. Review of the Relationship Between Built Environment and Public Health in North American Metropolitan Areas and Its Implications. Planner 2015, 31, 12–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Moudon, A.V. Physical Activity and Environment Research in the Health Field: Implications for Urban and Transportation Planning Practice and Research. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 19, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, E.; Dong, Y.; Yan, L.; Lin, A. Perceived Safety in the Neighborhood: Exploring the Role of Built Environment, Social Factors, Physical Activity and Multiple Pathways of Influence. Buildings 2023, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehner, C.M.; Brennan Ramirez, L.K.; Elliott, M.B.; Handy, S.L.; Brownson, R.C. Perceived and Objective Environmental Measures and Physical Activity Among Urban Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Jin, C.; Liu, C. The Impact of Built Environment in Shanghai Neighborhoods on the Physical and Mental Health of Elderly Residents: Validation of a Chain Mediation Model Using Deep Learning and Big Data Methods. Buildings 2024, 14, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Donovan, R.J. The Relative Influence of Individual, Social and Physical Environment Determinants of Physical Activity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 1793–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownson, R.C.; Hoehner, C.M.; Day, K.; Forsyth, A.; Sallis, J.F. Measuring the Built Environment for Physical Activity: State of the Science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S99–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.D.; Schmid, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B.E. Linking Objectively Measured Physical Activity with Objectively Measured Urban Form: Findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Xinjiekou Street | Financial Street | Baizhifang Street | |

|---|---|---|---|

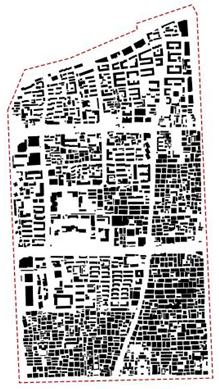

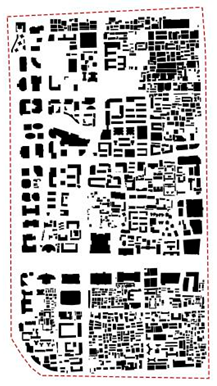

| Positioning [5] | Historical Type | Administrative Type | Residential Type |

| Spatial Form |  |  |  |

| Economic Data [12] | 34.92 billion CNY | 464.09 billion CNY | 0.17 billion CNY |

| Variable Selection | Variable Explanation | Basis for Indicator Selection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Built Environment | Urban Function within the Area (Facility Accessibility) | Leisure Facility Accessibility | Accessibility of Parks, Green Spaces, Plazas, and Open Spaces within the Three Different Streets | [15,20] |

| Accessibility of Gyms within the Three Different Streets | ||||

| Basic Attributes within the Area (Development Intensity) | Urban Density | Urban Density of Each Street | [17,24] | |

| Floor Area Ratio | Floor Area Ratio of Each Street | [10,17] | ||

| Land Use Mix | Land Use Mix of Each Street | [15,24] | ||

| Transportation within the Area (Public Transportation) | Connectivity with Public Transportation | Number of Bus Stops within Each Street | [10,16,18] | |

| Subjective Built Environment | Accessibility Satisfaction | Is it convenient for you to access facilities (parks, plazas, sports venues) from your residence? | [20,21] | |

| Safety Satisfaction | Do you feel safe walking around your neighborhood? | [22] | ||

| Attractiveness Satisfaction | Do you find the surrounding environment pleasant? | [23] | ||

| Indicator Population | Children (Under 7 Years) | Adolescents (7–18 Years) | Adults |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ≥6 days/week | ≥5 days/week | ≥5 days/week |

| Intensity | Encourage free movement for children under 1 year; engage in at least 180 min of varied physical activity daily | It is recommended to accumulate at least 60 min of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity daily, both inside and outside school. | Start at moderate intensity and gradually increase to higher intensity |

| Time/Recommended Amount | 30 min/day, totaling 150 min/week; gradually increase to 60 min/day or at least 250–300 min/week |

| Attribute | Grouping | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xinjiekou Street | Financial Street | Baizhifang Street | ||

| Gender | Male | 46.4 | 46.2 | 57.8 |

| Female | 53.6 | 53.7 | 42.1 | |

| Residential Status | Living Alone | 16.1 | 11.8 | 12.3 |

| Living with Children | 41.2 | 43.1 | 39.0 | |

| Co-renting with Others | 18.2 | 24.6 | 13.8 | |

| School or Work Accommodation | 16.6 | 17.8 | 30.1 | |

| Other | 7.6 | 2.4 | 4.6 | |

| Health Status | Very Poor | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Poor | 8.4 | 10.5 | 4.0 | |

| Average | 32.5 | 26.8 | 43.6 | |

| Good | 32.0 | 37.4 | 32.6 | |

| Healthy | 24.6 | 23.7 | 18.7 | |

| Monthly Income | ≤3000 RMB | 23.8 | 12.1 | 36.0 |

| 3001–6000 RMB | 19.7 | 23.5 | 20.6 | |

| 6001–9000 RMB | 26.9 | 29.2 | 28.6 | |

| 9001–12,000 RMB | 17.6 | 23.1 | 8.9 | |

| ≥12,001 RMB | 11.7 | 11.8 | 5.8 | |

| Age | 0–6 years | 2.8 | 0.2 | 5.3 |

| 7–17 years | 12.8 | 8.8 | 10.2 | |

| 18–40 years | 51.0 | 50.8 | 47.5 | |

| 41–65 years | 24.6 | 27.7 | 20.9 | |

| 66 years and above | 8.7 | 12.3 | 16.0 | |

| Days of Moderate-or-Above Intensity Physical Activity in the Past 7 Days | 0 days | 18.2 | 16.9 | 33.0 |

| 1 day | 20.2 | 57.4 | 12.7 | |

| 2–3 days | 19.2 | 24.4 | 21.8 | |

| 4–5 days | 20.0 | 0.6 | 7.2 | |

| 6–7 days | 22.3 | 0.4 | 25.0 | |

| Average Daily Duration of Moderate-or-Above Intensity Physical Activity | 0–10 min | 31.0 | 28.8 | 36.9 |

| 11–60 min | 21.5 | 42.5 | 26.4 | |

| 61–120 min | 14.1 | 18.0 | 13.5 | |

| 121–180 min | 14.6 | 6.6 | 9.2 | |

| ≥181 min | 18.7 | 3.9 | 13.8 | |

| Attribute | Grouping | Score |

|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with the land use in your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the mixed land use in your neighborhood? | The options “Very Dissatisfied, Dissatisfied, Neutral, Satisfied, Very Satisfied” correspond to the values (−2, −1, 0, 1, 2), respectively. Respondents were instructed to evaluate each attribute based on the extent to which the environmental condition facilitates or hinders their willingness to engage in outdoor physical activities. |

| How satisfied are you with the floor area ratio (FAR) of buildings in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the building density in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the green space area in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the road length in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of intersections in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the economic conditions of your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the housing prices in your neighborhood? | |

| How satisfied are you with the age of buildings in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the fitness costs at gyms in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the diversity of facility types in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of commercial facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of educational facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of medical facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the accessibility of facilities in your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the number of fitness facilities in your neighborhood? | |

| How satisfied are you with the number of public fitness facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of commercial fitness facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of fitness advertising facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the reachability of facilities in your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the number of bus stops in your neighborhood? | |

| How satisfied are you with the number of subway stations in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the walkability to the nearest fitness facility from your residence? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the comfort of your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the sunlight exposure in your neighborhood? | |

| How satisfied are you with the wind environment in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the thermal (temperature) environment in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the noise environment in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the greenery coverage in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the pavement quality in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the architectural design of buildings in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the spatial safety of your neighborhood? | How satisfied are you with the number of lighting facilities in your neighborhood? | |

| How satisfied are you with the number of surveillance facilities in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the number of police kiosks in your neighborhood? | ||

| How satisfied are you with the situation of vehicles occupying road space in your neighborhood? | ||

| Overall, how satisfied are you with engaging in sports and fitness activities in your neighborhood? | ||

| Attribute | Grouping | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xinjiekou Street | Financial Street | Baizhifang Street | ||

| Satisfaction with Land Use in the Neighborhood | −2 | 2.8 | 6.8 | 1.8 |

| −1 | 17.1 | 14.0 | 6.4 | |

| 0 | 44.1 | 35.6 | 42.4 | |

| 1 | 26.9 | 31.7 | 35.3 | |

| 2 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 13.8 | |

| Satisfaction with Economic Conditions of the Neighborhood | −2 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| −1 | 25.3 | 17.4 | 10.4 | |

| 0 | 43.3 | 39.4 | 54.1 | |

| 1 | 20.7 | 28.6 | 23.0 | |

| 2 | 5.6 | 12.3 | 9.8 | |

| Satisfaction with Accessibility of Facilities in the Neighborhood | −2 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| −1 | 22.3 | 14.9 | 3.6 | |

| 0 | 43.3 | 34.5 | 43.0 | |

| 1 | 22.5 | 35.0 | 36.0 | |

| 2 | 9.2 | 14.3 | 15.6 | |

| Satisfaction with Reachability of Facilities in the Neighborhood | −2 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| −1 | 14.6 | 9.4 | 5.5 | |

| 0 | 37.6 | 37.6 | 33.5 | |

| 1 | 31.7 | 35.2 | 43.3 | |

| 2 | 14.8 | 15.1 | 16.3 | |

| Satisfaction with Comfort of the Neighborhood | −2 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| −1 | 10.7 | 8.8 | 5.8 | |

| 0 | 9.2 | 46.4 | 41.8 | |

| 1 | 39.2 | 30.3 | 38.1 | |

| 2 | 39.2 | 10.5 | 12.3 | |

| Satisfaction with Spatial Safety of the Neighborhood | −2 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.5 |

| −1 | 23.3 | 10.5 | 5.8 | |

| 0 | 36.9 | 30.8 | 27.3 | |

| 1 | 30.5 | 34.5 | 43.3 | |

| 2 | 6.9 | 20.9 | 21.8 | |

| Overall Satisfaction with Engaging in Sports and Fitness Activities in the Neighborhood | −2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.6 |

| −1 | 7.4 | 12.1 | 4.6 | |

| 0 | 12.3 | 32.8 | 41.2 | |

| 1 | 47.4 | 32.3 | 38.7 | |

| 2 | 31.7 | 19.6 | 14.7 | |

| Evaluation Dimension Street | Xinjiekou Street | Financial Street | Baizhifang Street | Best Performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Use | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.47 | Baizhifang Street |

| Economic Conditions | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.27 | Financial Street |

| Facility Accessibility | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.60 | Baizhifang Street |

| Facility Reachability | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.68 | Baizhifang Street |

| Comfort | 1.03 | 0.36 | 0.52 | Xinjiekou Street |

| Spatial Safety | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.78 | Baizhifang Street |

| Sports and Fitness | 1.01 | 0.54 | 0.62 | Xinjiekou Street |

| Overall Average Score | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.56 | Baizhifang Street |

|  |  |  |

| 4 August, 07:00 | 4 August, 09:00 | 4 August, 11:00 | 4 August, 13:00 |

|  |  |  |

| 4 August, 15:00 | 4 August, 17:00 | 4 August, 19:00 | 4 August, 21:00 |

| Elements Legend | Facility Service Area Map (15 min Walking Radius) | Facility Coverage Population Map | Per Capita Facility Service Capacity Map |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parks, Green Spaces, and Open Spaces |  |  |  |

| Gyms |  |  |  |

| Element Legend | Facility Accessibility Represented on 200 m Fishnet Grid | Street Accessibility Calculated Using the D2SFCA Method |

|---|---|---|

| Parks, Green Spaces, and Open Spaces |  |  |

| Gyms |  |  |

| Data Item Sub-District | Xinjiekou Street | Financial Street | Baizhifang Street |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Density | 36.1% | 31.4% | 26.6% |

| Floor Area Ratio (FAR) | 1.23 | 1.89 | 1.44 |

| Number of Bus Stops (POI Map) |  | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Exp(β) | B | Exp(β) | B | Exp(β) | |||

| Independent Variables | Socioeconomic Attributes | Socioeconomic Attributes + Objective Built Environment | Socioeconomic Attributes + Objective Built Environment + Subjective Built Environment | |||||

| Socioeconomic Attributes | Gender (Reference = Female) | −0.147 | 0.863 | −0.166 | 0.847 | −0.193 | 0.825 | |

| Living with Children (Reference = Co-residing) | −0.044 | 0.957 | −1.868 | 0.154 | −2.112 | 0.121 | ||

| Education Level | 0.505 ** | 1.657 | 0.16 | 1.173 | 0.034 | 1.035 | ||

| Health Status (Reference = Healthy) | −0.481 ** | 0.618 | −0.380 ** | 0.683 | −0.201 | 0.818 | ||

| Monthly Income (Reference = ≤3000 RMB) | ||||||||

| 12,001 RMB | 2.44 *** | 11.574 | 1.74 *** | 5.706 | 1.412 ** | 4.104 | ||

| 9001–12,000 RMB | −3.014 *** | 0.049 | −3.64 *** | 0.026 | −3.342 *** | 0.035 | ||

| 6001–9000 RMB | 0.137 * | 1.147 | 0.713 | 2.04 | 0.745 | 2.106 | ||

| 3001–6000 RMB | −0.287 | 0.751 | −0.896 | 0.408 | −1.165 | 0.312 | ||

| Age (Reference = ≤6 years) | ||||||||

| ≥66 years | 3.163 *** | 23.547 | 4.116 *** | 61.377 | 3.809 *** | 45.138 | ||

| 41–65 years | −2.251 *** | 0.105 | −1.647 *** | 0.193 | −2.55 *** | 0.078 | ||

| 18–40 years | 0.464 | 1.591 | 1.574 ** | 4.825 | 1.573 ** | 4.819 | ||

| 7–17 years | 0.671 | 1.956 | 1.173 | 3.231 | 0.586 | 1.796 | ||

| Objective Built Environment | Accessibility of Leisure Facilities | Accessibility of Parks, Green Spaces, Plazas, and Open Spaces | 1.163 ** | 3.2 | 2.896 *** | 18.102 | ||

| Accessibility of Gyms | 2.312 * | 10.093 | 1.447 ** | 4.253 | ||||

| Public Transportation Convenience | Number of Bus Stops | 0.454 *** | 1.575 | 0.449 *** | 1.567 | |||

| Development Intensity | Land Use Mix | 0.820 ** | 2.27 | 1.078 ** | 2.939 | |||

| Urban Density | −11.435 ** | 0.001 | −16.918 *** | 0.001 | ||||

| Floor Area Ratio | 0.525 | 1.689 | −0.035 | 0.966 | ||||

| Subjective Built Environment | Accessibility Satisfaction | 0.801 ** | 2.229 | |||||

| Safety Satisfaction | 0.602 ** | 1.826 | ||||||

| Attractiveness Satisfaction | 0.962 ** | 2.617 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.695 | 0.735 | 0.748 | |||||

| Sample Size | 1072 | 1072 | 1072 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Liu, P.; Xu, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z. Interactions Between Objective and Subjective Built Environments in Promoting Leisure Physical Activities: A Case Study of Urban Regeneration Streets in Beijing. Buildings 2026, 16, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010194

Liu Y, Song H, Liu P, Xu Y, Hu J, Li Y, Yang Z. Interactions Between Objective and Subjective Built Environments in Promoting Leisure Physical Activities: A Case Study of Urban Regeneration Streets in Beijing. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010194

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yang, Haoen Song, Pinghao Liu, Yanni Xu, Jie Hu, Yu Li, and Zhen Yang. 2026. "Interactions Between Objective and Subjective Built Environments in Promoting Leisure Physical Activities: A Case Study of Urban Regeneration Streets in Beijing" Buildings 16, no. 1: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010194

APA StyleLiu, Y., Song, H., Liu, P., Xu, Y., Hu, J., Li, Y., & Yang, Z. (2026). Interactions Between Objective and Subjective Built Environments in Promoting Leisure Physical Activities: A Case Study of Urban Regeneration Streets in Beijing. Buildings, 16(1), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010194