1. Introduction

Urban heat islands (UHIs)—the phenomenon where urban areas experience significantly higher temperatures than surrounding rural regions—have become increasingly pronounced with accelerating urbanization and climate change [

1]. In megacities like New York, UHIs not only intensify energy demands but also elevate health risks [

2], strain infrastructure, and reduce urban livability [

3]. As a critical challenge to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals—especially those related to good health, sustainable cities, and climate action—mitigating the UHI effect is now central to urban sustainability agendas [

4]. Governments and planners are paying growing attention to identifying effective strategies to alleviate UHI impacts and enhance urban resilience [

5].

Early investigations into UHIs primarily examined physical-geographical variables, including temperature, humidity, vegetation indices, and the leaf area index [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Later studies expanded this scope to include socioeconomic and demographic factors such as population density and urban GDP [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Methodological evolution has also been notable: while early approaches relied on simple regression analysis [

15,

16], subsequent research incorporated principal component analysis and multiple linear regression [

17,

18], enhancing the capacity to capture spatial complexity in urban thermal patterns. In the context of New York City, historical heat events—such as the 2006 and 2011 heatwaves—have highlighted the severe public health risks and disproportionate impacts on vulnerable communities, prompting the development of targeted resilience initiatives like the “Cool Neighborhoods NYC” program and the NYC Green Infrastructure Plan [

19,

20]. These programs underscore the critical need for spatially explicit and interpretable UHI analysis to support urban cooling strategies [

21,

22].

More recently, the rise of machine learning has opened new avenues for modeling UHI dynamics with improved accuracy. Studies have employed models such as random forest and XGBOOST to capture nonlinear interactions among land surface, morphological, and climatic variables [

23,

24]. Furthermore, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques [

25]—such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), and Partial Dependence Plots (PDP)—has advanced model interpretability beyond basic feature importance, enabling more transparent and actionable insights into urban thermal drivers [

26,

27]. Alongside these technical developments, the increasing availability of crowdsourced geospatial data—e.g., from OpenStreetMap [

28], Overpass-turbo [

29], and NYC Open Data—has enabled high-resolution analyses of urban form and land cover. Prior studies have shown that in developed urban areas such as New York, the positional accuracy of OSM datasets is comparable to that of official data sources [

30]. Recent UHI literature has also increasingly focused on the roles of blue-green infrastructure—such as green roofs, urban forests, and water bodies—as well as urban morphology metrics (e.g., sky view factor, building height-to-width ratio) derived from multi-source remote sensing, which provide critical inputs for mitigating heat stress in dense urban settings [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Despite these advancements, many existing studies remain limited in two ways. First, they often adopt a generalized perspective on urban spatial form, overlooking the fine-grained built environment characteristics that shape UHI intensity [

25,

35]. Second, while machine learning models have been increasingly applied, few leverage interpretable frameworks that quantify the contributions of specific physical and socioeconomic drivers [

26]. This lack of interpretability reduces their utility for informing policy and targeted mitigation strategies. Moreover, models frequently omit optimization-based assessments of how urban variables could be adjusted to reduce UHI exposure—leading to a disconnect between analytical findings and actionable planning insights [

36].

To address these challenges, this study proposes a data-driven, interpretable machine learning framework for analyzing UHIs in the New York metropolitan region. Specifically, this study seeks to address the following three research questions:

Which physical and socioeconomic features most strongly influence spatial variation in urban heat across the New York metropolitan area?

To what extent can explainable machine learning models accurately predict land surface temperatures using multi-source urban datasets?

How can optimization simulations inform practical and targeted strategies for reducing heat exposure through changes in urban form and environmental design?

By leveraging Random Forest and XGBOOST models, we integrate vegetation indices, proximity to water, 3D urban morphology, and socioeconomic vulnerability indicators across more than 1800 census tracts. Our models achieve high predictive accuracy (mean R

2 ≈ 0.89), and feature importance analysis reveals that vegetation coverage and water proximity are the dominant cooling factors [

37,

38]. In contrast, socioeconomic indicators show weak correlations with temperature, indicating a relatively equitable thermal landscape [

39,

40]. Crucially, through simulation-based optimization, we identify threshold values—particularly for vegetation coverage—that can reduce surface temperatures by as much as 6.37 °C [

41]. These findings offer actionable guidance for green infrastructure design and adaptive urban planning, and demonstrate the value of explainable machine learning for tackling environmental challenges in complex urban systems.

The remainder of this paper is as follows: The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the datasets employed and outlines the methodology.

Section 3 reports the main results, highlighting both quantitative findings and key patterns.

Section 4 provides a detailed discussion of these results. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the contributions and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

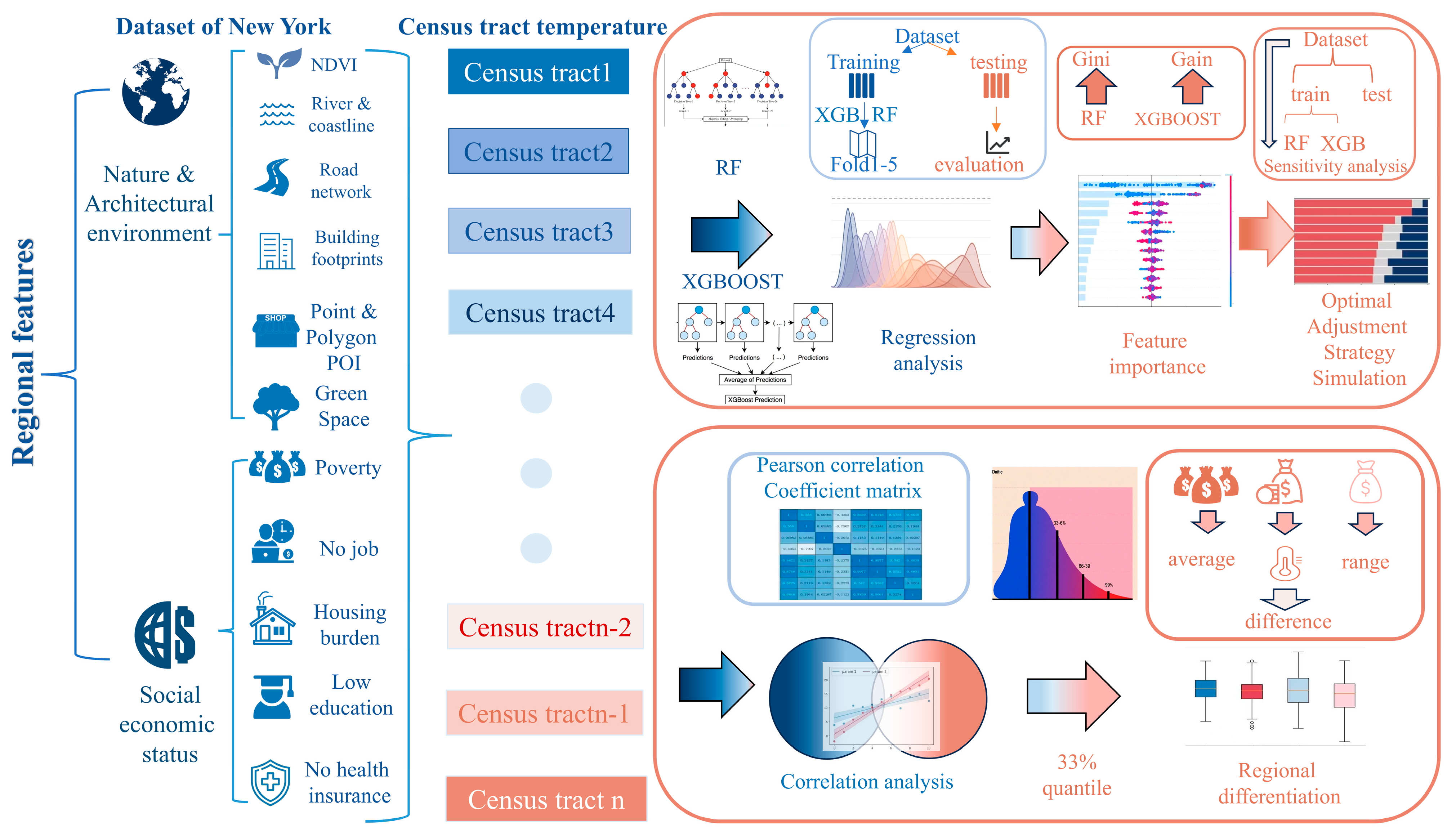

The main objective of this study is to use machine learning models to analyze urban heat islands and their drivers based on socioeconomic factors and the characteristics of the built environment. The analytic workflow of this study is shown as

Figure 1: The environmental and socioeconomic datasets were collected and integrated, On the left part of the figure, two categories of Regional features are detailed: Nature & Architectural environment, which encompasses indicators like NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), River & coastline, Road network, Building footprints, Green space and Point & Polygon POI (Points of Interest); and Social economic status, including metrics such as Poverty, No job, Housing burden, Low education, and No health insurance. These environmental and socioeconomic datasets were integrated with Census tract temperature data from multiple geographic units. after which Random Forest and XGBoost models were applied for regression analysis. The dataset was partitioned into training and testing subsets, with models trained and evaluated. Subsequent regression analysis was performed, and Feature importance was quantified via measures like Gini and Gain for RF and XGBOOST, paving the way for Sensitivity analysis and Optimal Adjustment Strategy Simulation. Then, correlation analysis was carried out, involving the construction of a Pearson correlation coefficient matrix and analysis at the 33% quantile, followed by an evaluation of regional differentiation in heat exposure—this evaluation considered dimensions such as average, difference, and range of socioeconomic indicators. Feature importance and sensitivity simulations were then conducted, followed by correlation analysis of socioeconomic indicators and evaluation of regional heat exposure differences.

2.1. Study Area and Collection of Data

This study focuses on the New York City metropolitan region, a dense urban environment characterized by significant spatial heterogeneity in land use, socioeconomic conditions, and built infrastructure [

42]. The region’s complex urban morphology and diverse population make it an ideal case for investigating the drivers and dynamics of urban heat islands (UHIs) [

43]. The analytical boundaries defined in this study are: 40.911327° N to 40.502397° N, and −74.247808° W to −73.700360° W. This range fully covers all five boroughs of New York City (New York County/Manhattan, Kings County/Brooklyn, Queens County/Queens, Bronx County/Bronx, and Richmond County/Staten Island), and includes parts of the western part of neighboring Nassau County, New York, and the eastern part of Hudson County, New Jersey. This study explicitly excludes most of Long Island; the Lower Hudson Valley, New York; most of Northern New Jersey; and southwestern Connecticut.

We collected a comprehensive set of geospatial and socio-environmental datasets for 2022 to analyze UHI patterns across more than 1800 census tracts, detailed in

Table 1. We selected the census tract as our fundamental spatial unit for several compelling reasons. A census tract is a relatively stable, small area specifically designed by the U.S. Census Bureau to approximate “neighborhoods”, typically housing 1200 to 8000 residents. This makes it an ideal scale for studying urban phenomena with intertwined social and environmental dimensions. The more than 1800 census tracts in our study range in area from approximately 0.07 km

2 to 15.63 km

2, reflecting the true heterogeneity of urban space. To ensure comparability, all input variables were standardized as proportions or densities within each tract’s total area.

While fixed grids (e.g., 1 km × 1 km) offer geometric regularity, they present significant disadvantages for this study. First, key socioeconomic vulnerability data from the CDC SVI is collected and published exclusively at the census tract level. Using a fixed grid would necessitate complex and uncertain spatial allocation of this data, introducing error and weakening the model’s explanatory power. Second, and crucially, urban planning, public health interventions, and resource allocation are typically implemented at the census tract or similar administrative level. Our findings can thus be directly mapped to these policy units, empowering decision-makers to identify specific communities for priority intervention and greatly enhancing the practical utility of our research.

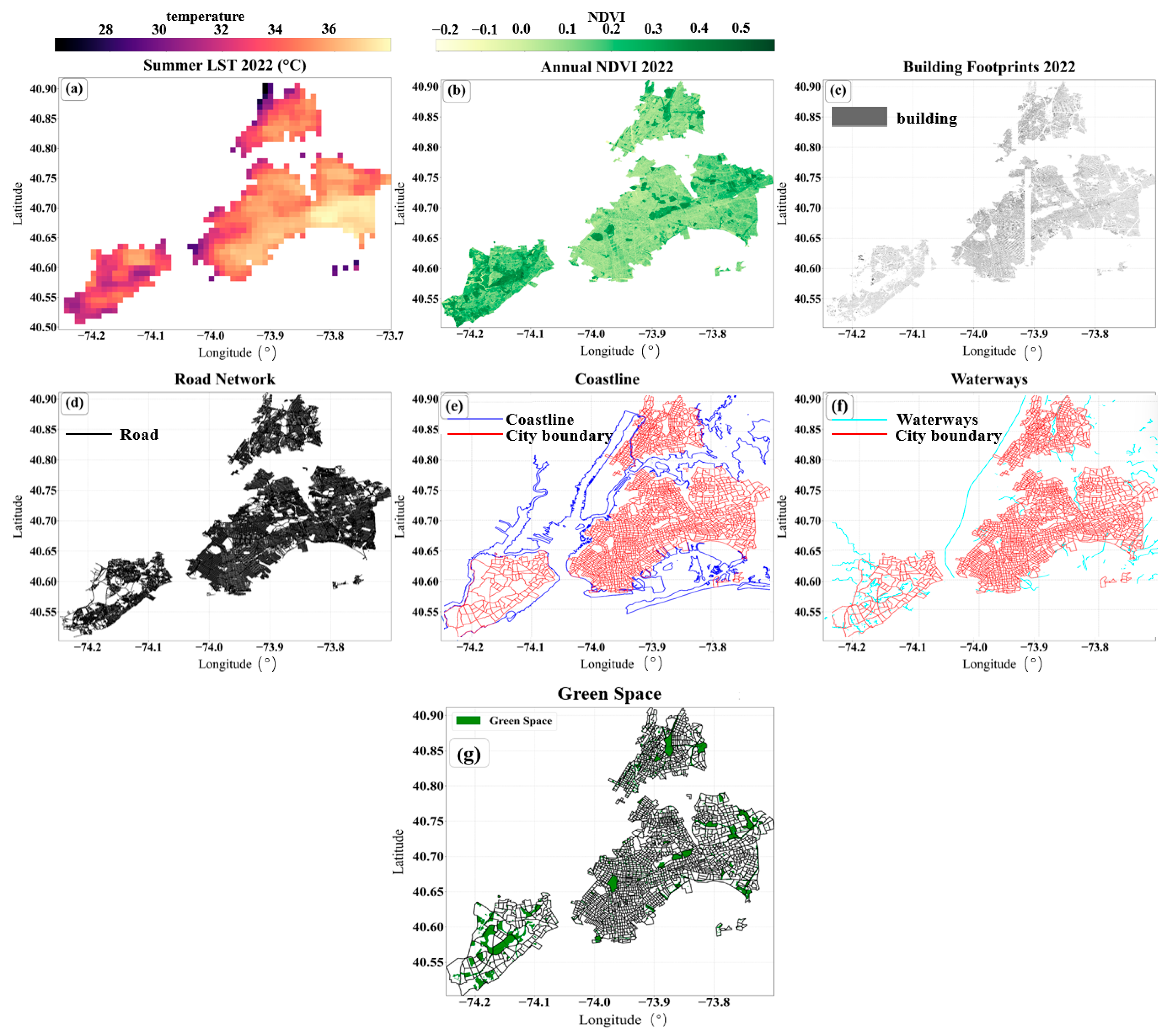

Land Surface Temperature (LST) data were derived from NASA’s Terra MODIS satellite (1 km resolution), focusing on summer daytime temperatures (June–August). The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was computed using ESA Sentinel-2 Level-2A imagery (10 m resolution). Green spaces were obtained from the NYC Open Data portal’s Parks Properties dataset. Urban morphology indicators—including building height, building coverage ratio, and POI densities—were extracted from the Global Building Footprints dataset, and OpenStreetMap using Python (version 3.12) scripts and the OSMnx library. Hydrological features such as water systems and coastline distances were retrieved from Geofabrik and Overpass-turbo, respectively. Socioeconomic variables—including poverty rate, unemployment, education level, and health insurance coverage—were obtained from the 2022 CDC Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), which aggregates American Community Survey data. Road network metrics were computed from OSM road geometry, while all vector boundaries (e.g., administrative units) were standardized using the WGS84 coordinate system. Raster data processing was conducted in Google Earth Engine; vector data were handled in Python with GeoPandas, and all outputs were exported in GeoTIFF or Shapefile formats. These datasets provide a multidimensional foundation for examining the environmental, morphological, and socioeconomic determinants of UHI intensity in the study area.

2.2. Machine Learning Models for Predicting the Heat Island Effect

This study frames the UHI intensity prediction as a regression problem. Given a set of spatial and socioeconomic features

, where each feature vector

, and the corresponding observed land surface temperature values

, we aim to learn a mapping function

that minimizes the prediction error across all census tracts:

where

denotes the predicted temperature for the

i-th, and D represents the number of input features (e.g., NDVI, distance to water, POI density, etc.).

In this study, two ensemble models are used to approximate the mapping function: (1) Random Forest (RF) and (2) Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBOOST). Both models construct multiple decision trees but differ in how trees are trained and aggregated. Random Forest builds trees independently on bootstrapped samples and averages their outputs, while XGBoost sequentially builds trees where each new tree aims to correct the residuals of previous trees. These models are well-suited for handling high-dimensional, nonlinear data and are considered interpretable due to their decision-tree architecture.

RF is an ensemble learning method that uses the bagging strategy (bootstrap aggregating). Each decision tree is trained on a random sample of the training set, and the final prediction is the average of all tree outputs:

where

is the output of the

j-th decision tree and M is the total number of trees. This method reduces variance and helps prevent overfitting, especially when the number of features is large.

XGBOOST, in contrast, uses a boosting strategy. It iteratively adds new trees to model the residuals of previous predictions. At each iteration mmm, a new tree

is learned to minimize a regularized loss function:

where

is the regularization term penalizing tree complexity (with

T nodes and

leaf weights). XGBOOST uses both the first- and second-order derivatives (i.e., gradients and Hessians) of the loss function to guide tree construction, which enhances convergence speed and model accuracy.

XGBOOST also implements advanced engineering optimizations such as parallelized tree construction and weighted quantile sketching for efficient handling of sparse or missing data. These innovations make XGBOOST particularly scalable and robust for large geospatial datasets.

The interpretability of both RF and XGBOOST is enabled through feature importance analysis. In RF, importance is assessed via Gini impurity reduction, while XGBOOST uses average gain—i.e., the improvement in model loss due to splits on a given feature. These importance scores reveal which urban, environmental, or socioeconomic factors most influence temperature variation, providing scientific insight for UHI mitigation planning.

2.3. Performance Evaluation

In order to explore the comprehensive impact of urban morphological characteristics (including NDVI, road network structure, distribution of functional facilities, adjacent water bodies, building attributes, etc.) on the local thermal environment (characterized by the temperature of the census area), an integrated machine learning algorithm based on decision tree was used for regression modeling. Such algorithms are good at capturing complex nonlinear relationships and interactions between high-dimensional features, which is crucial for understanding the urban temperature distribution under the combined influence of multiple factors. Specifically, two advanced integrated models, Random Forest (RF) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), are selected. RF reduces variance and improves generalization ability by constructing a large number of unrelated decision trees and averaging their predictions. XGBOOST builds decision trees sequentially, focusing on correcting the residuals of the previous tree, and optimizing the objective function through gradient descent to obtain strong predictive performance. The model input features include weighted average normalized vegetation index (NDVI), average road network length, point-of-interest (POI) density, shortest distance to the nearest water system, shortest distance to the coastline, building coverage ratio, and average building height. The target variable is the temperature observation of the corresponding census area. Model performance is quantitatively evaluated by mean squared error (MSE) and coefficient of determination (R

2).

represents the mean of the target variables, the denominator is the sum of the total squares, and the numerator is the sum of the residual squares

represents the actual observations of samples, represents the model prediction value of samples, and n represents the total number of samples.

2.4. Data Analysis and Software

The data processing, statistical analysis, and machine learning modeling presented in this study were conducted using the Python programming language (version 3.12). The analysis relied extensively on key scientific libraries including pandas for data manipulation, numpy for numerical computations, and scikit-learn for implementing the Random Forest and XGBoost algorithms. Visualizations were generated using the matplotlib and seaborn libraries. All scripts were developed and executed within the Visual Studio Code (version 3.12) integrated development environment.

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance in Predicting Urban Heat Exposure

One of our work’s focuses is to model the complex relationship between various built environmental features to the urban heat exposure. A snapshot of our various collected datasets in the study regions is displayed in

Figure 2. The maps in

Figure 2 use geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude in degrees) as their spatial reference.

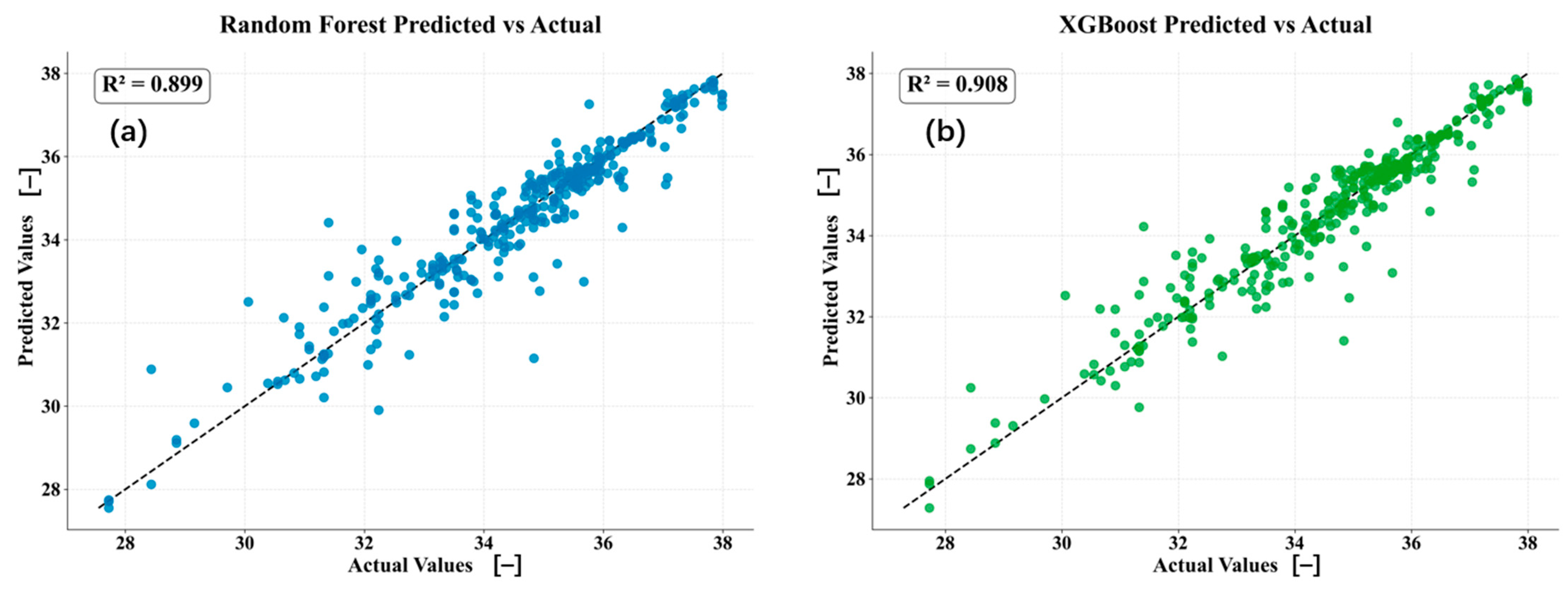

Both ensemble regression models show excellent prediction ability for the spatial distribution of temperature in the census area, as shown in

Figure 3. The results of the Random Forest (RF) model show a mean square error (MSE) of 0.3975 and a coefficient of determination (R

2) of 0.8994. The Extreme Gradient Boost (XGBOOST) model performed slightly better, with its MSE dropping to 0.3623 and R

2 increasing to 0.9083. These results show that both models successfully capture the complex relationship between the selected urban morphological features (NDVI, road network, POI, adjacent water bodies, building coverage and height) and local temperature, and can explain the variation of more than 89.9% (RF) and 90.8% (XGBOOST) in the temperature observations in the census tract.

Such result in

Table 2 confirms that the selected feature set has a strong comprehensive interpretive ability for depicting the spatial differentiation of urban thermal environment. The Random Forest (RF) model achieved an average R

2 of 0.8994 with an average MSE of 0.3975, while XGBoost yielded a slightly higher average R

2 of 0.9083 and a lower average MSE of 0.3623. Both models exhibited low standard deviations in performance metrics across folds (MSE SD: 0.0925 for RF, 0.0951 for XGBoost; R

2 SD: 0.034 for RF, 0.0308 for XGBoost), indicating consistent predictive performance. Classification metrics derived from temperature threshold analysis revealed high precision (RF: 0.9212, XGBoost: 0.9126) and recall (RF: 0.9168, XGBoost: 0.9148), with correspondingly low false negative rates (RF: 0.0832, XGBoost: 0.0852) and false positive rates (RF: 0.0773, XGBoost: 0.0873). This comprehensive evaluation demonstrates the models’ strong generalization capability and reliability for urban heat island prediction. This performance difference may stem from XGBOOST’s built-in regularization mechanisms, more efficient gradient optimization strategies, and enhanced learning capabilities for complex feature interactions, giving it a slight advantage in handling that particular dataset.

The high R2 values (both close to or above 0.9) and low MSE values of the two models together indicate that the model predictions are highly reliable and robust, and the relationship established is statistically significant.

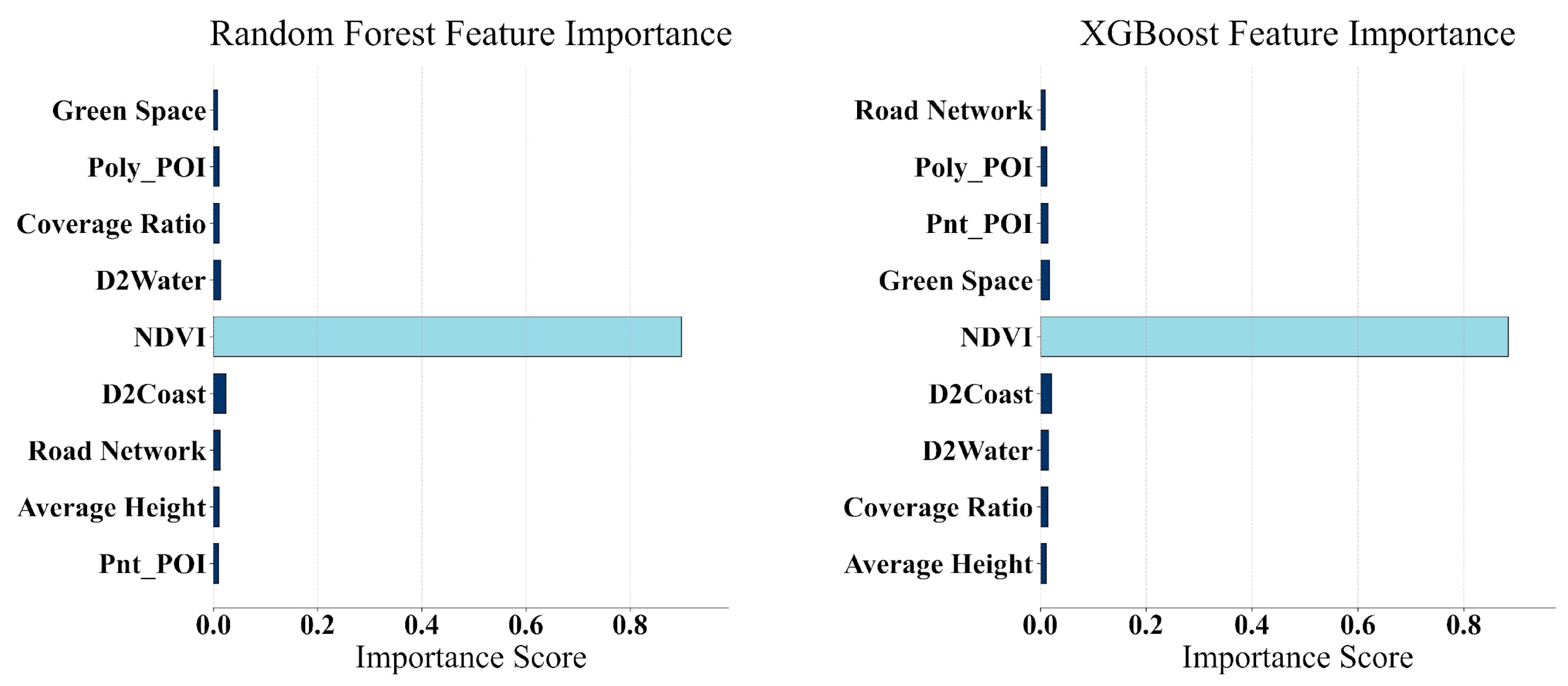

3.2. Dominant Role of Vegetation in Feature Importance Analysis

To explore the factors influencing the urban heat island effect across New York census tracts, we evaluated the relative importance of each feature using two models: Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB). For the RF model, feature importance was measured using Gini importance, while for the XGB model, the gain metric (average reduction in the loss function) was applied.

As shown in

Table 3, both models consistently identified NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) as the dominant predictor, with Gini importance of 0.8989 in RF and a gain importance of 0.8843 in XGBoost, both ranking first. This overwhelming contribution indicates that vegetation coverage exerts a far stronger effect on surface temperature than any other factor considered in the analysis. The next most influential variables were distance to coastline (D2Coast, second in both models) and distance to water bodies (D2Water, third in RF and fourth in XGBoost), though their importance values (RF: 0.0240 and 0.0139; XGBoost: 0.0213 and 0.0157) were much lower than NDVI. Such results suggest that while geographical proximity to natural cooling elements like water does matter, its role is secondary compared with vegetation. It is worth noting that Green space ranked ninth in RF but third in XGBoost, showing notable model-dependent variation. The remaining features—including POI density, average building height, building coverage ratio, and road network length—all had importance values predominantly below 0.014. Although their direct contributions to prediction accuracy were small, their consistent presence in both models indicates they still capture subtle variations in local thermal environments.

These patterns are further illustrated in

Figure 4, where NDVI stands out as the overwhelmingly dominant factor in both models, while all other features cluster near zero. The visual contrast reinforces the statistical results from the table, making it immediately clear that vegetation cover plays a decisive role in regulating urban surface temperature. At the same time, the compressed scale of the other variables highlights the sharp disparity between NDVI and the rest, suggesting that most urban forms and socioeconomic characteristics provide only marginal explanatory power on their own. This does not mean they are irrelevant; rather, their influence is overshadowed by NDVI but may emerge more clearly through interactions that are difficult to visualize directly from the importance scores. As shown in

Figure 5, SHAP analysis further validates these findings, with NDVI again exhibiting the highest mean |SHAP value| (approximately 1.2–1.4), substantially exceeding D2Coast (≈0.25) and D2Water (≈0.10). The remaining features—Coverage Ratio, Poly_POI, Average Height, Road Network, Pnt_POI, and Green Space—all show mean SHAP values below 0.05, reinforcing their relatively minor individual influence in the model.

The prominence of NDVI reflects the well-known cooling effects of vegetation through shading and evapotranspiration. Distances to coastlines and water bodies are also meaningful, as water moderates surface temperatures due to its high heat capacity and associated sea–land breeze circulation. The relatively low contributions of POI density, road networks, and building form may be explained by weaker or indirect physical links with surface temperature, as well as data limitations (e.g., POI static distributions, simplified building metrics). Nonetheless, these features may still enhance model performance by capturing nonlinear interactions with dominant variables like NDVI.

3.3. Socioeconomic Indicators and Their Weak Correlation with Temperature

In this study, the point–two–sequence correlation method was applied to examine the spatial relationship between land surface temperature and five socioeconomic vulnerability indicators: poverty (F_POV150), unemployment (F_UNEMP), housing burden (F_HBURD), education (F_NOHSDP), and health insurance (F_UNINSUR). Each indicator was coded as a binary variable, with “1” indicating that a census tract falls within the top 10% of vulnerability for that metric and “0” indicating a non-vulnerable area. As summarized in

Table 4, all five indicators produced

p-values greater than 0.05 (ranging from 0.685 to 0.920) and correlation coefficients near zero (|r| < 0.01). These results indicate no statistically significant correlation in this framework. The temperature differences between vulnerable and non-vulnerable areas were modest in scale, all less than 0.75 °C. Among the five metrics, four showed slightly cooler conditions in high-vulnerability areas, while only health insurance vulnerability corresponded to a small increase (+0.20 °C). Additionally, the age-related indicators (Age 65+ and Age < 17) also showed no significant correlation with temperature, with correlation coefficients near zero (Age 65+: r = −0.00669,

p = 0.773583; Age < 17: r = −0.00954,

p = 0.68158) and minimal temperature differences between vulnerable and non-vulnerable areas (Age 65+: −0.33 °C; Age < 17: +0.03 °C), consistent with the overall pattern of weak bivariate relationships.

However, the tercile stratification reveals a different pattern. Instead of focusing only on the most extreme 10% of vulnerable tracts, this method classified all census tracts into low, medium, and high vulnerability groups based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles of each indicator. This broader categorization allows for detecting gradient-like trends across the full distribution rather than only at the tail.

Figure 6 shows the temperature distribution of socioeconomic vulnerability categories based on ternary quartiles, with a total sample size of 1851 census districts. The specific sample sizes for each category are as follows: Poverty rate: Low (612), Medium (610), High (629); Unemployment rate: Low (615), Medium (611), High (625); Housing affordability: Low (612), Medium (611), High (628); Education level (no high school diploma): Low (612), Medium (610), High (629); Health insurance (uninsured rate): Low (614), Medium (609), High (628). For the age structure indicators: Proportion of Age 65+: Low (622), Medium (607), High (622); Proportion of Age < 17: Low (624), Medium (608), High (619). Each subplot is presented as a violin plot, with the

Y-axis representing surface temperature (°C) and the

X-axis representing the low, medium, and high vulnerability categories based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles. The width of the violin plot represents the probability density, and the inner box plots represent the quartiles and medians.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, mean summer daily temperatures increased consistently with rising levels of socioeconomic vulnerability. Specifically, temperatures ranged from 26 °C (low) to 34 °C (high) for poverty, 28 °C to 34 °C for unemployment, 26 °C to 32 °C for housing burden, and 26 °C to 38 °C for both low educational attainment and lack of insurance. A similar gradient is evident for the age structure indicators: temperatures increased from 26 °C (low) to 32 °C (high) for tracts with a high proportion of residents Age 65+, and from 26 °C to 32 °C for tracts with a high proportion of residents Age < 17. Across all indicators, the most disadvantaged tercile experienced substantially higher heat exposure than the least disadvantaged tercile, with differences of 6–12 °C.

Taken together, these findings suggest that while binary top-decile comparisons show negligible differences, the tercile stratification reveals systematic overlaps between socioeconomic disadvantage and elevated heat exposure. The discrepancy arises because the binary approach focuses only on the most extreme 10% of vulnerable tracts, which may mask broader gradients across the population, especially in cities where policy interventions and environmental buffers mitigate conditions for the very worst-off neighborhoods. In contrast, the tercile method captures vulnerability across the full distribution, offering a more sensitive and comprehensive view of inequality. Therefore, although both approaches provide useful perspectives, the stratified analysis better reflects the cumulative heat burden faced by disadvantaged groups. Overall, our results indicate that socioeconomic inequality and climate vulnerability are closely intertwined in the study area, reinforcing the need for adaptation strategies that address both environmental exposures and their underlying social determinants.

As shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5, to further determine the quantitative relationship, we employed correlation analysis and multiple regression to reanalyze the socioeconomic vulnerability index as a continuous variable. The results revealed a subtle relationship: while the bivariate correlation between individual socioeconomic vulnerability indices and surface temperature was negligible (all |r| < 0.01,

p > 0.68), multiple regression analysis identified two significant predictors. Areas with higher education levels (lower education levels: β = −0.569,

p < 0.001) had lower surface temperatures, potentially reflecting related green infrastructure investment. Conversely, areas with limited health insurance coverage (no health insurance: β = 0.415,

p < 0.001) had higher surface temperatures, indicating an overlap between environmental and social vulnerabilities. Poverty, unemployment, and housing burden did not show significant independent effects. Similarly, the age structure indicators (Age 65+ and Age < 17) were not significant in the multiple regression model (Age 65+: β = 0.006277,

p = 0.11087; Age < 17: β = −0.00634,

p = 0.104688), suggesting that age alone does not independently influence temperature patterns after accounting for other socioeconomic variables. These findings confirm that the previously reported weak relationship between socioeconomic status and temperature is not merely a result of categorical variable transformation, but rather demonstrates robustness to the analytical methods.

3.4. Sensitivity Simulations of Urban Morphological Features

Based on the random forest regression model, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on eight urban morphological features to evaluate their influence on land surface temperature. The random forest model, built with 100 decision trees, performed well on the test set (R2 = 0.898, MSE = 0.634 °C), with a baseline temperature of 34.63 °C across all samples.

The quantitative outcomes are summarized in

Table 6. Among all features, NDVI was by far the most influential: increasing NDVI to a coefficient of 0.75 led to a sharp temperature reduction of 6.37 °C, resulting in a predicted temperature of 28.26 °C. In contrast, distance-related factors such as D2coast (coefficient 0.05) and D2water (coefficient 0.05) produced much smaller effects, with reductions of 0.28 °C and 0.16 °C, respectively. Adjustments to the remaining features—road network, average building height, building coverage ratio, Pnt_POI, Poly_POI, and Green space—produced only marginal changes, all below 0.1 °C. Notably, green space at coefficient 0.05 showed a minimal reduction of only 0.01 °C. These results point to vegetation as the most effective single lever for reducing surface heat.

A broader view of the sensitivity experiments is shown in

Figure 7, which illustrates the response of each feature across the full range of adjustment coefficients. The figure clearly shows that NDVI achieves substantially greater temperature reduction across its adjustment range compared to all other features. While the general trend confirms NDVI’s dominance, some subtler patterns emerge. For instance, increasing average building height to coefficient 2.0 produced a 0.05 °C reduction, while Poly_POI at coefficient 1.6 showed a 0.02 °C reduction—weak but measurable cooling effects, possibly reflecting shading from taller buildings or the cooling contributions of specific land uses. Meanwhile, dramatic reductions in features like road network (coefficient 0.05) showed only 0.04 °C cooling, though such adjustments are clearly unrealistic in real-world planning scenarios.

Taken together, the sensitivity analysis suggests that the most practical and effective strategies for mitigating the urban heat island effect are those that enhance vegetation cover (NDVI). Proximity to coastal and water bodies provides secondary benefits, while the contributions of other urban form features are relatively limited. The minimal impact of green space as an individual factor suggests that simply increasing green space distribution without considering vegetation quality may have limited cooling effect. At the same time, secondary effects—such as shading from taller structures or diversified land uses—should not be ignored, and the combined influence of multiple urban form features needs to be considered when developing comprehensive heat-mitigation strategies.

5. Conclusions

Clarifying the role of different drivers in urban heat islands is crucial for emergency management of the heat island effect. This study proposes an interpretable machine learning model that can make effective adjustment strategies for reducing urban heat islands. In this study, the changes in the decision tree model and various eco-building economic characteristics were used to explore the state of urban heat islands. The models were trained and tested using data from select cities in New York State, and the results showed that the models were all very accurate. Further analysis of the feature importance determined that NDVI has an absolute advantage in influencing the temperature of the study area, and then simulated different adjustment coefficients for each index to find the most effective scheme of the link heat island effect. In order to ensure the comprehensiveness of the study, the temperature differences between regions with different socioeconomic conditions were also studied to highlight the need for locally specific measures and model training specifications.

The models and results of this study are significant in many aspects, firstly, these machine learning models are real-time and dynamic, providing a data-based and easy-to-implement tool to dynamically simulate specific indicators in different regions and provide a basis for relevant policies. Secondly, this study contributes to the research on the role of machine learning models in the urban heat island effect. Data-driven models have been proven to be able to effectively complement physical principles models, so as to balance efficiency and mechanism, so that heat island effect research can have the advantages of large-scale implementation prediction, multivariate data fusion, dynamic scenario adaptation, mechanism research and refined simulation, and reduce the possible obstacles caused by the computational and computational cost requirements of physics-based models.

Based on the model and results presented in this study, there are some valuable directions for future exploration that can address some of the limitations of this study. First, this study does not cover all regions, resulting in incomplete research results, and future studies can use methods such as natural networks (GNNs) to capture the spatial adjacencies of regions and the corresponding characteristics of each region, so as to obtain more comprehensive and balanced data for model training. Secondly, our selected data lacked granularity and precision; the inclusion of built environment characteristics was incomplete; and the design of socioeconomic factors was inadequate because the affluence/health level indicators were too general and did not play a significant role. Using MODIS data (1 km resolution) for fine-scale modeling in a complex urban environment like New York City may lead to scale mismatch issues. Furthermore, relying solely on 2022 data limits the model’s generalization ability. Future research will incorporate community-level data on gardens and green spaces, and economic data on children and the elderly, and will process data from multiple years for comparison, while placing greater emphasis on data accuracy. Finally, since my research mainly focuses on the rough study of each indicator, which may make the strategy formulation less detailed, with the expansion of the dataset, future research can focus on the detailed study of the functions of each indicator (such as studying the canopy 3D green amount of vegetation, root permeability index, etc.), so as to enhance the utility of the model in management and response, so as to provide more accurate information.