Abstract

The environmental quality of conference and exhibition places in small- and medium-sized cities plays a crucial role in attracting exhibitors, fostering the growth of the conference and exhibition industry and enhancing the market competitiveness of these places. However, past decision makers have often adopted planning models from large cities, neglecting the interaction between conference and exhibition places in smaller cities and local lifestyles as well as urban environments. From an “environment-behavior” perspective, this study reveals the unique interaction mechanisms between exhibitors and the built environment within such venues. Moving beyond the limitations of traditional research that focused solely on physical indicators, we place particular emphasis on exhibitors’ behavioral adaptations and their overall exhibition experience in the convention environment. To address this gap, this study employs a mixed-method approach that integrates field surveys, interviews, and questionnaires to systematically collect data from 10 representative cases. First, a preliminary study was conducted to establish an evaluation index system for place environmental quality. Through regression analysis, six key indicators—such as promotional atmosphere, site accessibility, and surrounding urban development conditions—were identified as significant factors influencing place quality. Second, subjective evaluations were conducted based on users’ actual experiences and experts’ professional insights, leading to the development of an importance–performance analysis model to assess value expectations and place environmental performance. The results indicated that users had high expectations for elements such as parking availability, transportation facilities, and the surrounding commercial atmosphere. In contrast, experts emphasized the significance of proximity to urban transportation hubs, site accessibility, and the spatial orientation of public spaces in determining environmental quality. Moreover, differences in evaluations among experts from various fields revealed notable variations in focus and priority considerations. Finally, based on a statistical analysis of the survey results, this study proposes three design recommendations—“adaptation, attraction, and quality enhancement”—to optimize the environmental quality of conference and exhibition places in small- and medium-sized cities, offering both theoretical and practical guidance for future planning, design, and evaluation.

1. Introduction

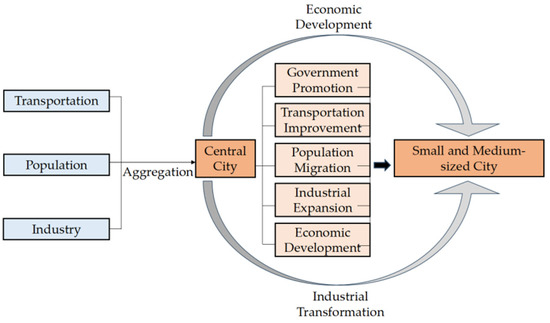

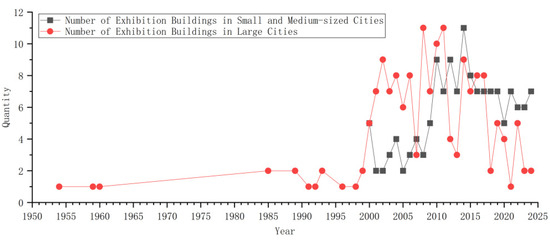

During the “14th Five-Year Plan” period, the Chinese government explicitly proposed accelerating the development of small- and medium-sized cities while optimizing their spatial layout—an essential strategy for achieving sustained, healthy, and high-quality economic growth. Under this policy guidance, these cities are increasingly assuming a greater role in industry transfer and labor division, evolving into specialized hubs for economic and industrial development [1] (Figure 1). At the same time, with continuous improvements in infrastructure and the rapid advancement of informatization, many of the bottlenecks that once constrained the conference and exhibition industry in small- and medium-sized cities are gradually being eliminated. This positive shift not only strengthens the role of the conference and exhibition service industry in supporting the economic development of small- and medium-sized cities but also fuels a growing demand for the construction of conference and exhibition facilities (Figure 2). Against this backdrop, many of these cities in China have high expectations for the conference and exhibition industry, particularly in sector-specific domains, aiming to stimulate economic growth and improve income levels through the rapid expansion of related industries and economic activities. Consequently, small- and medium-sized cities are witnessing a surge in the construction of conference and exhibition places.

Figure 1.

Interaction mechanism between central cities and small- and medium-sized cities.

Figure 2.

Comparison of exhibition facility construction between large cities and small- and medium-sized cities.

For a long time, the construction of conference and exhibition facilities in small- and medium-sized cities has often followed development models adopted from larger cities. This approach has resulted in insufficient recognition of the unique characteristics, opportunities, and challenges faced by these places, leading to relatively weak theoretical research in this area [2]. Existing studies mainly focus on the theory and engineering design of large conference and exhibition buildings, typically referencing the “MICE” concept, which stands for Meetings, Incentive Travel, Conferences, and Exhibitions. In 2000, Fred Lawson (UK) published Conference and Exhibition Facilities: Planning, Design, and Management, which systematically addressed issues related to the planning, design, construction, maintenance, and management of exhibition facilities. Kusch (2013) systematically elaborates on structural engineering solutions and spatial design methodologies for convention and exhibition buildings [3]. In addition, UFI published the World Map of Exhibition Site in 2011 and 2017, offering a detailed analysis of the global distribution, quantity, market share, and trends of indoor exhibition venues larger than 5000 square meters, categorized by country, region, and time. Notable design firm projects have also provided valuable references for the design of large conference and exhibition buildings. Examples include SOM’s ASEM Exhibition Center, GMP’s series of works such as Von Gerkan, Marg, and Partners: New Leipzig Fair and Von Gerkan, Marg and Partner (2003–2007), and Thomas Herzog’s Hall 26.

In recent years, academic research has increasingly recognized these venues as significant drivers of urban development, highlighting their deep integration with the urban spatial environment. As a vital component of urban development, conference and exhibition buildings not only stimulate the growth of the conference and exhibition industry and its related activities but also contribute to the enhancement of urban functions and the improvement of the city’s image [4,5]. Scholars such as Crouch and Geoffrey have highlighted that, to enhance the competitiveness of the conference and exhibition industry, places must thoroughly understand and address key factors in place selection decisions to succeed in an increasingly competitive market [6]. Fortin and Ritchie have suggested that placing sites far from city centers may weaken their interaction with urban life, emphasizing the need for planning that balances place environmental quality with local lifestyles to strengthen connections with the city [7]. Xu Maoyan et al. proposed that planning and environmental considerations are central to sustainable development, arguing that scientific planning can enhance both the competitiveness of places and their environmental quality, ultimately achieving coordinated growth between conference and exhibition buildings and the cities they serve [8]. Zhao Jianfeng’s research explored the relationship between conference and exhibition buildings and regional culture, examining the creative concepts and design principles of regionally inspired conference and exhibition places [9]. Ni Yang, using typological methods, analyzed and categorized conference and exhibition buildings from different periods in modern history, tracing their evolutionary trajectories and proposing a new conceptual design model tailored to China’s context. This model was developed based on the characteristics of the conference and exhibition industry and the urban development trends of the new era [4]. Hou Xiao introduced the “symbiosis theory” into exhibition complexes, proposing a symbiotic strategy system that integrates exhibition complexes with urban environments to promote their sustainable development [10].

For convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities, the focus should extend beyond their differences from those in large cities to emphasize their synergistic development with the urban spatial environment. These two types of cities exhibit fundamental distinctions across four key dimensions: functional positioning, spatial organization, operational models, and the site environment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities versus large cities.

Large-city convention centers are characterized by internationalization, comprehensiveness, and premium positioning, mainly serving global- or national-scale exhibitions. Their spatial configuration prioritizes operational efficiency and intensive land use, employs highly market-oriented management approaches, and strategically leverages central urban locations to create commercial hubs. In contrast, convention centers in small- and medium-sized cities focus on regional specialization, with functional orientations deeply embedded in local industrial ecosystems and community needs. Their architectural designs emphasize spatial adaptability for various events, operational frameworks depend on government support with strong industry collaboration, and site planning actively incorporates distinctive local resources to enhance contextual appeal.

Conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities follow distinct development patterns due to differences in economic development levels, industrial structures, and resource availability compared with large cities. Relying solely on large-scale, facility-focused construction models from major urban centers is not always suitable for smaller cities. Blindly replicating these models can lead to several issues: (1) low operational efficiency due to limited market capacity and demand, resulting in low venue utilization rates and reduced economic benefits [11,12]; (2) resource constraints, as smaller cities often have limited financial resources and industrial infrastructure, making it difficult to support the construction and operation of large conference and exhibition facilities [13,14,15]; and (3) market volatility, as the industrial structure and market demand in smaller cities are relatively unstable, increasing the risk of operational challenges [16,17,18,19].

Research on conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities should go beyond a limited focus on architectural design and functionality. It should address three key areas: (1) How can the visitor experience be improved through better spatial layout, enhanced service facilities, and optimized circulation flow to increase comfort, accessibility, and engagement? (2) What strategies can strengthen the integration of these buildings with local industries and urban planning by aligning with the surrounding commercial environment and transportation networks, thereby improving site accessibility and economic impact? (3) How can these buildings be designed to better align with urban lifestyles and the built environment by promoting flexibility in use over time and across functions while also supporting sustainable development?

In summary, research on conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities should place greater emphasis on place environmental quality as a core factor in their differentiated development. The place environment serves not only as a medium for interaction between these buildings and urban spaces, industries, and civic life but also as a decisive factor in their functional efficiency and long-term sustainability. A systematic analysis of the multidimensional relationships within place environmental quality can uncover the unique role of conference and exhibition buildings in regional economies and provide strategies for optimizing site selection, strengthening urban connections, and enhancing spatial flexibility. Furthermore, research should deepen the integration of these buildings with regional culture and ecological resources, exploring their potential to increase urban image and competitiveness, thereby fostering their coordinated development alongside urban economies, societies, and environments.

2. Research Design

2.1. Conceptual Definition

The built environment, as the physical foundation of human activities, refers to the urban spatial system shaped by artificial construction [20]. This concept mainly emphasizes the structural characteristics, functional roles, and social impacts of the built environment. The subjective evaluation of environmental quality refers to the personal perception and description of the objective attributes of the built environment, representing a collective cognitive image of its essential characteristics while maintaining a degree of objectivity [21]. This evaluation process involves individuals assessing the environment based on their perceptions of its condition, using these impressions to determine the quality of various elements and spatial attributes within the built environment. The evaluation factors should mainly focus on the material components of the built environment system, supplemented by socio-psychological aspects, to achieve a more objective representation of environmental quality [21]. Since the 1960s, subjective evaluation of the built environment has continuously evolved in the West, developing into a well-established theoretical framework, mainly through post-occupancy evaluation and predictive evaluation in architectural programming [22]. Various methods have been introduced, including Daniel and Boster’s standardization of evaluation values, Gifford and Buhyoff’s comparative evaluation approach based on environmental comparisons [23], and Ervinh and Briggs’s on-site and off-site evaluation methods [24]. In China, scholars have made significant contributions to the field of subjective environmental quality evaluation. Researchers such as Wu Shuoxian, Yu Guoliang, Wang Qinglan, and Yang Zhiliang have employed diverse evaluation methods and tools to assess environmental quality, focusing on spatial behavior data collection, feature analysis, and the application of multiple mathematical models and techniques. Scholars such as Zhuang Weimin, Lin Yulian, and Hu Zhengfan have mainly focused on the semantic differential (SD) method, examining spatial evaluation from the perspectives of evaluation factors and public perception elements [25,26,27,28]. Zhu Xiaolei, Yang Yang, Yang Gongxia, and Xu Leiqing have conducted subjective quality evaluations in various contexts, including bank halls, university campuses, urban residential environments, and public urban spaces [28,29,30]. Additionally, Dr. Yin Zhaohui applied this evaluation technique to the study of users’ explicit needs, with an emphasis on material elements [31].

This study focuses on the core concept of “Place Environment Quality”, which encompasses the environmental characteristics and overall quality of specific spatial locations. This research aims to develop an evaluation system for environmental quality applicable to various spaces, including urban public areas, outdoor plazas, and indoor venues, with the goal of enhancing their functionality, aesthetic value, comfort, and usability. “Place Environment Quality” refers to the systematic environmental characteristics and overall quality performance that emerge from the synergistic interaction between physical environmental elements and socio-cultural factors within specific spatial settings. This conceptual framework overcomes the limitations of traditional environmental quality assessments, which often overemphasize objective physical indicators and instead emphasize the holistic nature of the “human–environment” interaction. It encompasses key elements that directly influence the user experience of exhibitors and visitors in convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. These elements include functional efficiency (assessing the alignment between spatial organization and usage efficiency), aesthetic performance (evaluating the synergy between visual order and artistic appeal), physiological comfort (focusing on the adaptability of microclimate and ergonomic design), and social interaction (exploring how spatial form influences communicative behaviors). Together, these factors form the core determinants of user experience in convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities, offering a new analytical perspective for understanding these unique built environments that blend public accessibility with professional functionality.

This study makes significant breakthroughs in three main areas: First, by integrating the “Place Theory” from geography with the “Environment-Behavior Theory” from social psychology, it develops an environmental quality assessment framework specifically tailored for convention and exhibition buildings. Second, by shifting the research focus from large-scale convention centers to small- and medium-sized urban contexts, this study reveals the unique interaction mechanisms between exhibitors and the built environment. The most theoretically significant aspect is the introduction of “place identity” as a core concept within the analytical framework. This concept thoroughly explains the psychological mechanism through which the physical environmental quality influences users’ emotional attachment, thus achieving a cognitive shift from physical space to social space. This theoretical framework not only addresses the gap in existing research regarding users’ subjective experiences but, more importantly, offers a user-experience-centered value orientation for the environmental design of convention and exhibition buildings.

2.2. Research Methods

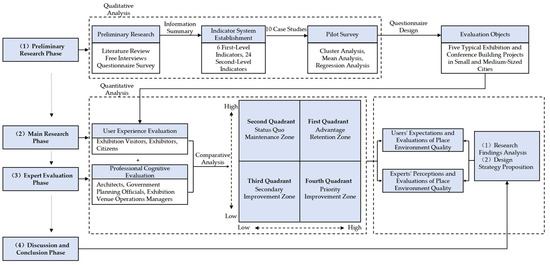

This study examines the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities, focusing on the integration of these places with the broader urban environment and the impact of exhibition activities on site conditions. A subjective evaluation of environmental quality is conducted through a dual-perspective approach: first, by analyzing users’ cognitive experiences, and second, by incorporating systematic assessments from professionals. By combining subjective user evaluations with expert analyses, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the built environment. User evaluations follow the psychophysical paradigm, emphasizing real-time experiences and perceptions of individuals within the actual environment. In contrast, expert evaluations are grounded in the expert paradigm and cognitive paradigm, focusing on a systematic and scientific analysis of place environmental quality from a broader, macro-perspective. Integrating these dual perspectives not only captures the actual needs of users but also compensates for the limitations of user perception through expert judgment, providing a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for evaluating and optimizing the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities (Figure 3). Additionally, this study incorporates the importance–performance analysis (IPA) method, which assesses users’ perceptions of the importance of specific attributes and their actual satisfaction levels, offering valuable insights for quality improvement.

Figure 3.

Research framework for assessing the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities.

2.3. Research Content

This research systematically evaluates the place environmental quality elements of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities (Figure 3). The study is structured into three key phases:

- (1)

- Preliminary research phase: This phase utilizes literature reviews, interviews, and open-ended questionnaire surveys to explore users’ cognitive characteristics and behavioral patterns related to place environmental quality. This section reviews relevant literature on the evaluation of the built environment in conference and exhibition buildings. Using qualitative research methods, this study gathers key insights into users’ functional needs, aesthetic preferences, and usage tendencies. These findings provide an empirical foundation for defining the focus of subsequent research.

- (2)

- Main research phase: This phase focuses on typical case studies to develop a quality evaluation model for place environmental quality from the user’s perspective. Centered on users’ phenomenological experiences throughout the entire exhibition activity cycle, this research constructs a dynamic assessment model that challenges the traditional, physical-environment-dominated evaluation approach. It advances a humanistic design paradigm grounded in participatory observation and embodied cognition theories. By establishing an IPA model, the study systematically identifies the strengths and areas for improvement in the place environments of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. According to the varying characteristics of different evaluation samples, targeted recommendations for environmental optimization are proposed.

- (3)

- Expert evaluation phase: A professional team was assembled to conduct a systematic assessment of the research samples. Utilizing techniques such as drone aerial photography, on-site surveys, and spatial analysis mapping, an IPA model of place environmental quality is developed from the expert perspective. By comparing and analyzing the evaluation results of both users and experts, this study provides scientific evidence for the continuous improvement of place environmental quality and offers professional guidance for relevant management decisions.

- (4)

- Discussion and conclusion phase: The comparative analysis of users’ experiential perceptions and experts’ professional evaluations highlights significant disparities between subjective user experiences (such as spatial preferences and behavioral comfort) and objective expert criteria (such as daylighting, ventilation standards, floor plan design, and parking specifications). This approach corrects the previous tendency in research to prioritize technical expertise at the expense of user-centered perspectives. It advances the application of human-centered design theory in small- to medium-sized cities and provides practical design strategies.

3. Preliminary Research

3.1. Literature Review and Free Interviews

This study adopts a combined approach of literature research and field investigation to construct an evaluation indicator system. First, a preliminary pool of candidate indicators was established through a systematic literature review. Subsequently, in-depth interviews were conducted during industry exhibitions to identify the core evaluation indicators prioritized by users. This pilot study provides a scientific basis for determining subsequent research directions.

By reviewing nearly 130 Chinese and international literature sources—including 50 master’s and doctoral theses, 60 journal articles, and 20 books—this research consolidates key findings on the built environment quality of conference and exhibition buildings from an architectural perspective. The literature spans various aspects, including planning and site selection [11,32,33,34,35,36], architectural space [37,38], traffic organization [6,8,34,39,40,41], landscape design [37,42], the physical environment [43,44,45,46], and place value [4,5].

During exhibition events, the authors conducted free interviews, walk-through evaluations, and selective interviews, allowing interviewees to share their perspectives on the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. In the survey on the built environment characteristics of these buildings, key comments highlighting place environmental quality included convenient parking (85.71%), accessible and comfortable transportation facilities to the place (64.29%), improved exhibition viewing efficiency and reduced crowding (76.19%), comprehensive commercial facilities surrounding the site (61.9%), well-organized spatial flow for exhibition activities (71.43%), the issue of elderly visitors experiencing fatigue during exhibitions, along with their need for convenient facilities (69.4%), and rest areas and amenities for parents with infants and elderly visitors (58.9%). A total of 18 factors received over 50% agreement, underscoring the strong connection between users and these environmental elements, which indirectly reflect user needs for conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. Additionally, areas identified for improvement included the availability of comprehensive commercial facilities around conference and exhibition buildings (61.9%), minimizing the impact of traffic control on urban traffic during large events (66.67%) and the lack of dedicated resting and recreation areas (52.5%). Nine factors received over 50% agreement, highlighting the gap between user experience and expectations. Respondents’ needs can be summarized into five key aspects: convenient transportation and accessibility, comfortable exhibition viewing, urban environment, event atmosphere, and participation.

3.2. Questionnaire Survey

This study employs a rigorous multi-stage selection process to identify representative convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities in China. The research methodology integrates both quantitative and qualitative approaches:

- (1)

- Initial screening framework:

We began by establishing selection criteria based on four key dimensions: functional typology (usage patterns and spatial layouts), architectural characteristics (building quality and surrounding spaces), urban context (location advantages and planning conditions), and resource endowment (exhibition resources and service facilities).

- (2)

- Comprehensive data collection:

Building on the systematic research from one author’s doctoral dissertation and multiple practical projects conducted by our team, we gathered detailed data on 148 convention and exhibition buildings across small- and medium-sized cities in China. From this collection, 74 projects were selected for thorough field verification.

- (3)

- Stratified sampling process:

Using a stratified sampling method, we initially selected 10 cases for preliminary study (Table 2), ensuring heterogeneity in scale, transportation access, and site planning, representative examples that demonstrate unique urban characteristics, and a balanced sample size for a manageable yet meaningful comparison.

Table 2.

Basic information of the evaluated conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities (the specific information of the research case can be found in Appendix A).

- (4)

- Final case determination:

Through iterative expert reviews and team discussions, we refined the selection to the five most representative cases based on regional balance (covering the developed regions of East, Central, and South China), city profile (GDP in the range of RMB 300–600 billion ), construction timeline (projects completed between 2010 and 2020), and functional completeness (integration of exhibition, conference, and support facilities).

3.2.1. Indicator Selection and Questionnaire Design

According to the research findings, the indicators were reviewed to assess their impact on place environmental quality, with redundant elements removed. The establishment of the indicator system forms the foundation of the entire evaluation process, directly influencing the objectivity and scientific validity of the results [47]. In recent years, our team has been involved in the design of seven exhibition buildings. According to preliminary research, we initially invited three experts from our team to review the quality and clarity of the questionnaire. Additionally, during the survey and interview phase, the authors conducted trial runs with the target population to refine any ambiguous wording.

This study refines and categorizes 24 relevant characteristic indicators (Table 3). These include 6 first-level indicators and 24 second-level indicators, measured using a five-point Likert scale: very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, neutral, somewhat dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied (assigned values of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, to convert responses into an ordinal measurement level for subjective evaluation [48]). Additionally, a five-level importance assessment was conducted for each indicator.

Table 3.

Summary of evaluation indicators for place environmental quality.

3.2.2. Data Analysis

A total of 460 questionnaires were distributed, with 447 collected, resulting in a response rate of 97.17%. After excluding incomplete, careless, or incorrectly filled questionnaires, 439 valid responses were obtained, yielding an effective rate of 98.21% (Table 4). The questionnaires were mainly distributed on-site. To ensure the accuracy of the survey data, a reliability analysis was conducted on the two key components: importance and satisfaction. A reliability test value greater than 0.65 meets the minimum acceptable threshold. The overall importance Alpha coefficient was 0.843, and the satisfaction Alpha coefficient was 0.776, indicating a high level of reliability for the data.

Table 4.

Overview of evaluators’ background information.

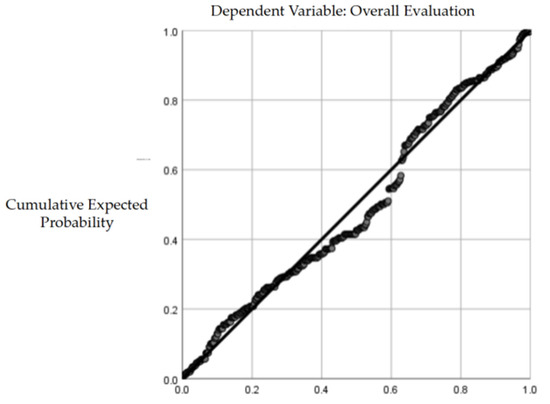

To determine the key factors influencing the overall evaluation of different place environmental qualities, a multiple stepwise regression analysis was performed on the questionnaire data to eliminate factors with insignificant impacts. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) table indicates that the p-values of the model are all less than 0.05, confirming a significant linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Additionally, the scatter plot of standardized predicted values versus standardized residuals shows that the points are evenly distributed above and below the horizontal line at zero on the vertical axis, validating the assumption of linearity (Figure 4). Using the evaluation factors as independent variables and the overall evaluation as the dependent variable, the regression equation between the independent and dependent variables was derived.

Figure 4.

Normalized residual plot of the regression model.

The regression equation identifies six key indicators that significantly impact the overall evaluation of the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities: (advertising and promotional atmosphere), (site accessibility), (outdoor greenery), (road accessibility), (surrounding urban construction status), and (walking distance to the entrance). The regression analysis further highlights five major factors that mainly influence place environmental quality:

Site perception and expectations: the promotion and design of exhibition activities play a crucial role in shaping users’ expectations and overall recognition.

Transportation convenience and accessibility: these factors are essential for ensuring a smooth and convenient experience for participants.

Walking distance and safety: the ease and security of reaching the place directly impact user comfort and satisfaction; it also includes the specific requirements of diverse user groups (with particular attention to vulnerable populations) regarding circulation pathways in exhibition spaces.

Comfort of the landscape environment: well-designed greenery and landscaping enhance aesthetics and improve participant satisfaction.

Urban development quality: a well-developed surrounding environment strengthens the site’s overall image and attractiveness.

4. User Evaluation of Place Environmental Quality in Five Case Studies

4.1. Questionnaire Data Analysis

To determine whether significant differences exist between the importance and satisfaction evaluations of place environmental quality indicators, a paired-sample t-test was conducted. The results indicate significant differences across all 24 indicators, highlighting a notable gap between users’ expectations and the current state of the environment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Importance–satisfaction scores of place environmental quality.

Regarding importance, the mean score for the four indicators was 4.15, all exceeding 3, indicating a general recognition of their significance. This reflects users’ strong emphasis on place environmental quality. Notably, indicators such as transportation convenience, exhibition flow, and atmosphere ranked highest, aligning with the key influencing factors identified in the regression equation and further validating users’ primary concerns.

Regarding satisfaction, scores ranged from 2.76 to 4.03, with certain indicators revealing significant deficiencies. Factors such as pavement maintenance, material selection, landscape design, surrounding commercial atmosphere, and urban development received lower scores, highlighting the negative impact of inadequate infrastructure and lagging development on the overall user experience.

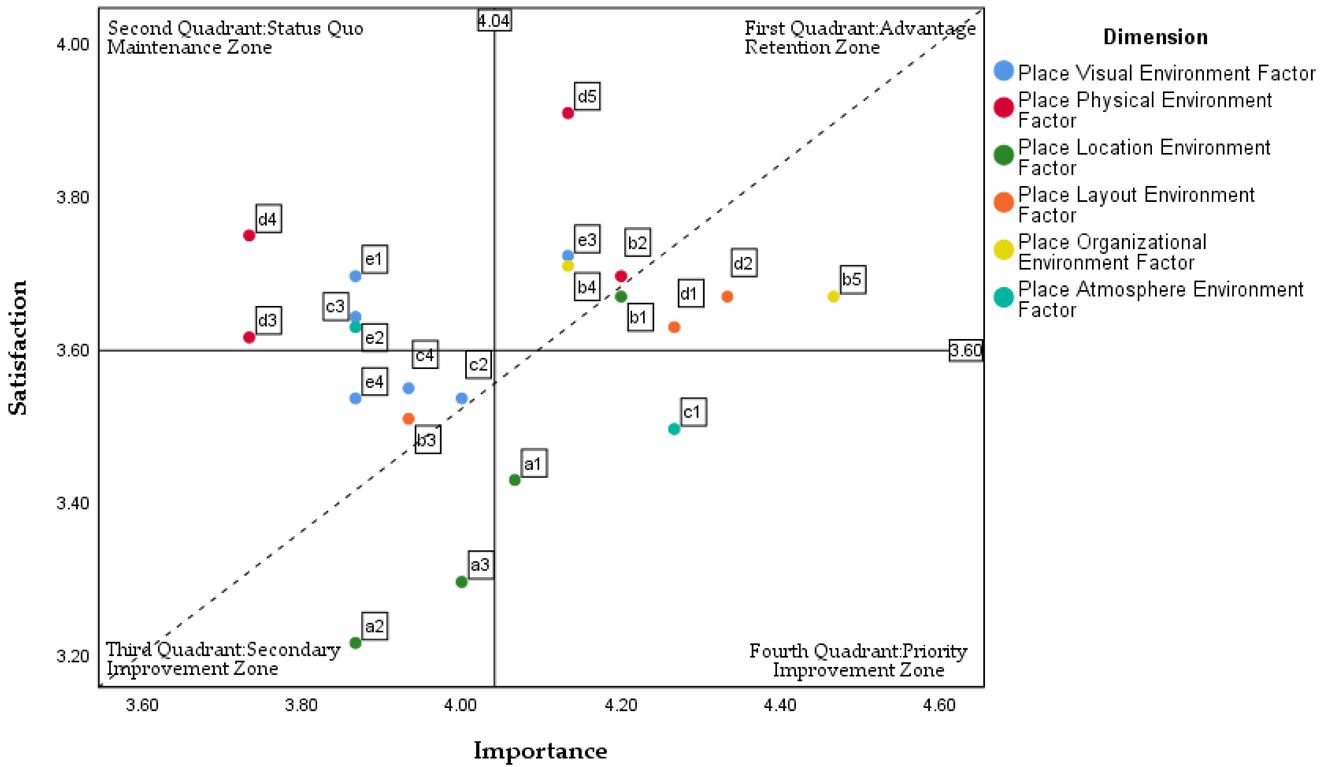

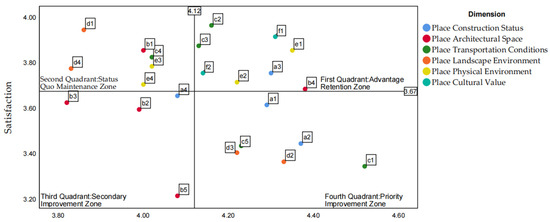

4.2. Construction and Analysis of the Overall IPA Model

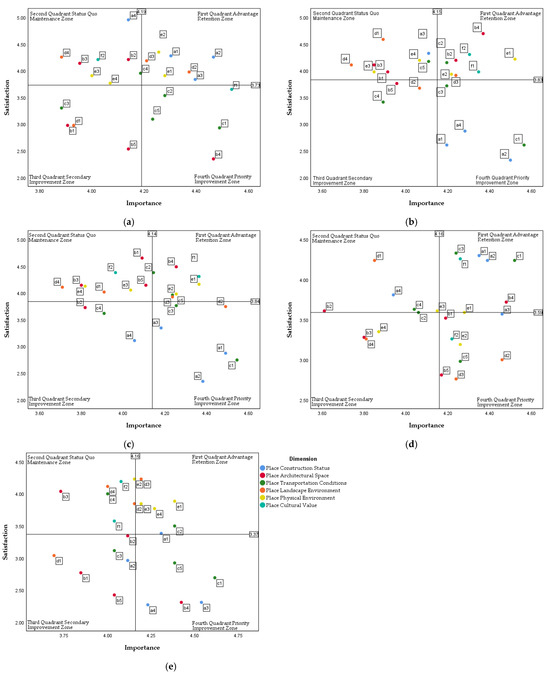

In the IPA model (Figure 5), user satisfaction scores serve as the vertical axis, while importance scores form the horizontal axis, creating a two-dimensional, four-quadrant coordinate system. The mean or median of both variables is typically used as the origin, dividing the quadrants, each representing different levels of improvement priority [49].

Figure 5.

Distribution diagram of the IPA model for place environmental quality.

The first quadrant (advantage retention zone) includes factors such as advertising and promotional atmosphere (f1) and distance to transportation hubs (a3), totaling seven elements. These factors have both high importance and high satisfaction, requiring continuous maintenance and enhancement to sustain their advantages.

The second quadrant (status quo maintenance zone) includes factors such as sense of orientation and signage system (b1) and drop-off space (c4), totaling six elements. These factors have high satisfaction but lower importance, meaning they require only routine maintenance to preserve their current effectiveness.

The third quadrant (secondary improvement zone) includes factors such as surrounding natural resources (a4) and the relationship between the building and topography (b3). These factors have both low satisfaction and low importance but may gain significance in the future due to evolving user demands.

The fourth quadrant (priority improvement zone) includes factors such as landscape features (d3) and parking space availability (c5), totaling six elements. These factors are highly important but have low satisfaction, requiring prioritized improvements to enhance the overall place’s environmental quality.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of IPA Models for Five Case Studies

The authors selected five conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities—RZ, ZMD, JJ, YW, and TZ—as comparative samples. These buildings, completed between 2010 and 2020, have been in operation for at least three years. A systematic analysis of the sample information (Table 1) and the IPA model highlights common characteristics and differences in construction quality, spatial organization, transportation conditions, and facility equipment among conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities (Figure 6). The analysis is as follows:

Figure 6.

(a) RZ-IPA model diagram; (b) ZMD-IPA model diagram; (c) JJ-IPA model diagram; (d) YW-IPA model diagram; (e) TZ-IPA model diagram.

- (1)

- Construction quality:

The IPA model reveals regional disparities in the construction quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. JJ and ZMD show lower user satisfaction due to shortcomings in surrounding urban development and commercial atmosphere, highlighting a mismatch between the overall urban development level and the operation of these buildings. In contrast, YW and RZ achieve higher user satisfaction, benefiting from more mature regional economies and commercial environments. These findings suggest that the development of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities should align with overall urban planning and regional economic growth, with an emphasis on improving functional facilities and enhancing commercial vitality.

- (2)

- Spatial organization:

The IPA model highlights both commonalities and differences in spatial organization across the projects, particularly in orientation, signage systems, and functional space layout. RZ and TZ fall short of user expectations regarding entrance location and functional connectivity, revealing weaknesses in spatial planning and circulation design. In contrast, JJ achieves higher user satisfaction due to its well-structured layout and clear signage. These findings suggest that conference and exhibition buildings should optimize circulation paths, improve signage systems, and enhance connectivity between functional areas to increase the overall spatial experience.

- (3)

- Transportation conditions:

Transportation is a critical factor influencing the user experience of conference and exhibition buildings. The IPA model indicates that, except for YW, most projects receive low user satisfaction scores for transportation accessibility and connectivity, highlighting deficiencies in infrastructure and road planning. Moreover, with the exception of ZMD, most places suffer from a shortage of parking spaces, limiting their capacity to accommodate visitors. RZ and YW are particularly criticized for long walking distances, which reduce user comfort. In contrast, ZMD and JJ demonstrate better transportation organization and connecting facilities, leading to higher user satisfaction.

- (4)

- Facility equipment:

Regarding facilities such as air conditioning, air quality, broadcasting, and lighting, the five sample cases receive consistently positive evaluations. This suggests that conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities have achieved a certain level of maturity and standardization in facility configuration and construction quality. While the basic quality of internal facilities is well ensured, future improvements should focus on enhancing the external environment and aligning with urban development to address shortcomings beyond the building itself.

Overall, while conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities have reached a relatively high level of maturity and standardization in facility configuration, shortcomings in transportation organization, spatial layout, and the surrounding commercial environment remain key factors affecting user satisfaction.

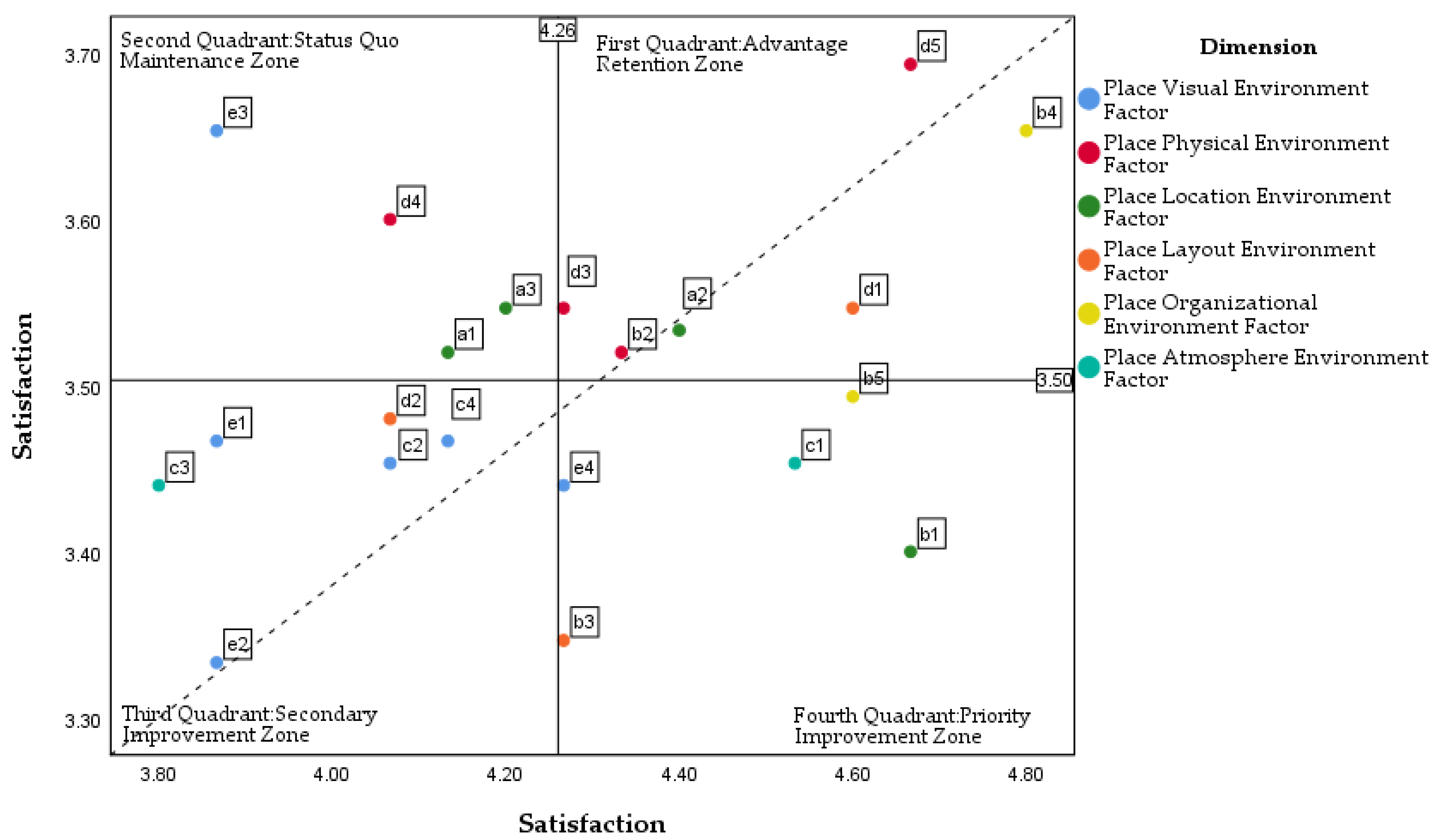

5. Experts’ Cognitive Evaluation of Place Environmental Quality in Five Case Studies

According to previous research, the evaluation indicators were optimized to guide experts in assessing place environment perception. The research questionnaire was divided into two parts.

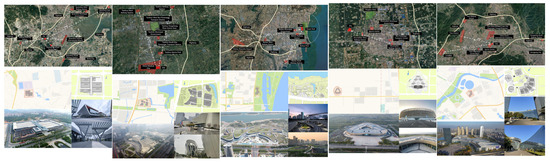

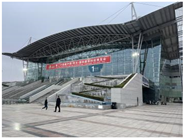

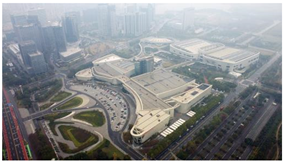

The first section provided image materials of the selected conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. These materials included urban planning layouts, locational context, aerial views, and place environment images collected through field surveys and data gathering to ensure the evaluators had a comprehensive understanding of each place (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Example images of evaluated samples.

The second section utilized a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 5, from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied”) to assess the importance of 21 indicators, ultimately identifying the 5 most critical factors.

This study invited 50 experts to evaluate aerial images and real-life photographs of five conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities. A total of 53 questionnaires were distributed, with 50 valid responses collected, resulting in a response rate of 94.3%.

The experts were categorized into three groups:

Government officials: 20 participants from planning and natural resources departments, all civil servants with national government appointments, including 17 staff members and 3 principal staff members.

Design professionals: 15 participants, all certified planners and professional engineers, comprising 5 junior engineers, 4 associate engineers, and 6 senior engineers.

Conference and exhibition operation managers: 15 participants, including company presidents, all key personnel in exhibition architecture operations, consisting of 4 operations supervisors, 8 vice presidents, and 3 presidents.

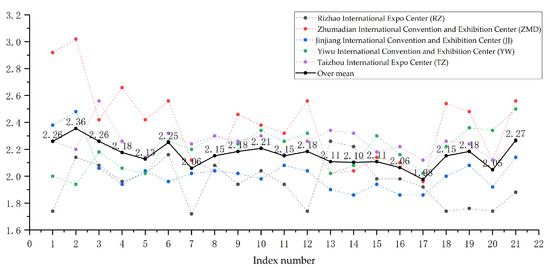

5.1. Questionnaire Data Analysis

- (1)

- Mean and Variance Analysis

The mean analysis of the expert questionnaires (Figure 8) indicates that the overall average scores for the cases range from 1.976 to 2.356, all falling within the “good” category on the Likert scale. Some evaluation indicators for different cases are either above or below the overall mean. Additionally, expert evaluations show significant differences at the 0.01 confidence level based on their roles (government officials, architects, and operations management leaders), suggesting that experts from different fields have distinct perceptions of place environmental quality (Table 6). Further research will be conducted to identify the specific focus areas of experts in different roles, providing insights for enhancing the overall quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities.

Figure 8.

Comparison of mean scores across different cases in expert questionnaires.

Table 6.

Mean analysis of expert questionnaire data.

- (2)

- Factor Analysis

To investigate the underlying psychological criteria and interrelationships among the indicators in expert evaluations, a factor analysis was conducted on the questionnaire data. The suitability test results showed Bartlett’s test of sphericity with a p-value of 0.000 and a KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) value of 0.942, confirming the appropriateness of factor analysis. Using principal component analysis, six characteristic factors were extracted, followed by orthogonal rotation using the varimax method to develop a factor model for place environmental quality evaluation (Table 7). The identified factors are named as follows:

Table 7.

Rotated factor loading matrix.

Place visual environment factor: encompasses visual elements such as building volume, form, and landscape (e1–e4, c2, and c4).

Place physical environment factor: evaluates the impact of building layout on lighting, evacuation, and ventilation (d2–d4).

Place location environment factor: focuses on surrounding urban development, urban environment, and building location conditions (a1–a3 and b1).

Place layout environment factor: examines how layout influences spatial efficiency and outdoor walking distances (d1, d2, and b3).

Place organizational environment factor: assesses the quality of spatial organization, including parking availability and drop-off spaces (b4 and b5).

Place atmosphere environment factor: reflects the spatial quality of the assembly plaza scale and the overall activity atmosphere (c1 and c3).

The analysis suggests that evaluating the place environmental quality of conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities should prioritize visual environmental effects. Additionally, the coordination between buildings and the regional environment, as well as circulation organization, plays a crucial role in achieving harmony with the urban spatial environment. At the same time, optimizing layout, organization, and atmospheric factors is essential for a comprehensive improvement in place environmental quality.

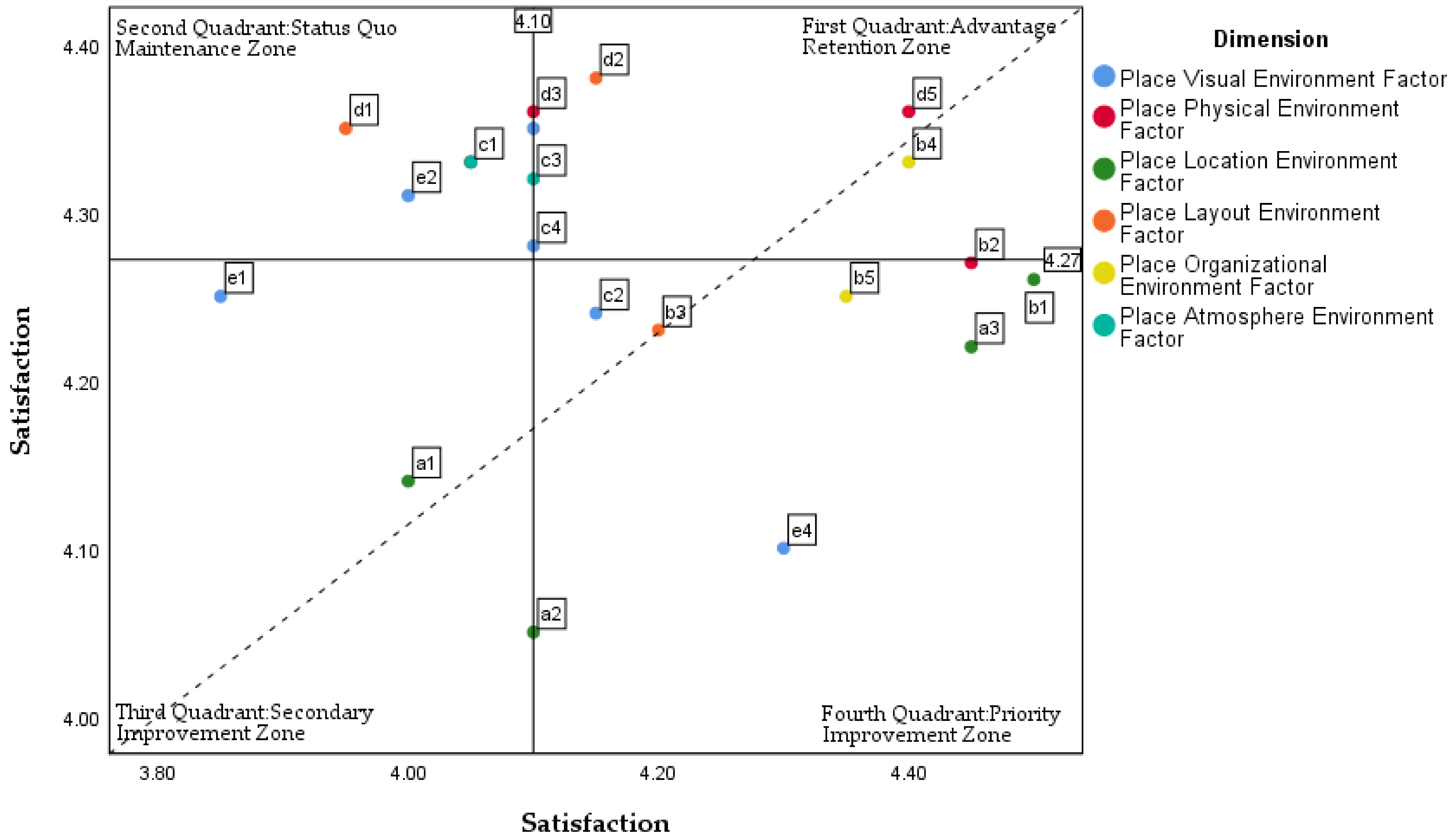

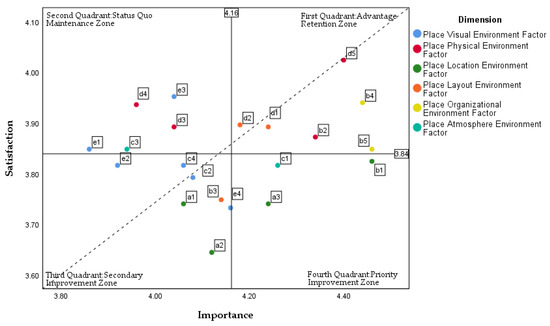

5.2. Construction and Analysis of the Overall IPA Model

Through the IPA model distribution diagram (Figure 9), expert evaluations of the importance and satisfaction of place environment quality indicators can be identified. The focus is on indicators with high importance but low satisfaction to determine key areas for improvement.

Figure 9.

IPA model distribution diagram of place environmental quality.

Quadrant I (advantage maintenance zone) includes six indicators, such as site road accessibility (b2), drop-off space for exhibition events (b4), and adequacy of parking spaces (b5). These indicators are rated highly in both importance and satisfaction but still require continuous optimization.

Quadrant II (status quo maintenance zone) includes five indicators, such as the scale of the gathering plaza (c3), natural ventilation effect (d3), and daylighting effect (d4). While these factors do not require immediate improvement, satisfaction can be further enhanced by exploring potential enhancements.

Quadrant III (secondary improvement zone) includes six indicators, such as surrounding urban development conditions (a1), surrounding commercial atmosphere (a2), and walking distance to the entrance (b3). These indicators score low in both importance and satisfaction, requiring moderate improvement.

Quadrant IV (key improvement zone) includes four indicators, such as distance to transportation hubs (a3), site accessibility (b1), and atmosphere of the public space (c1). These indicators are highly important but have low satisfaction, making them critical areas for enhancing the overall quality of the place environment.

The IPA model incorporates a 45-degree classification line (black dashed line) to differentiate priority levels. Indicators positioned below this line and closer to the X-axis—such as surrounding commercial atmosphere (a2), surrounding urban development (a1), site accessibility (b1), and distance to transportation hubs (a3)—require prioritized improvements.

In addition, although place organizational environment factors are located in Quadrant I, overall satisfaction remains below expectations, indicating a need for further enhancements. Specific areas requiring attention include walking distance to the entrance (b3) and the applicability of the building’s floor plan (d1) within place layout factors, the cultural significance of the architecture (e4) within place visual environment factors, and the atmosphere of the public space (c1) within place ambiance factors.

5.3. Analysis of Differences in Evaluations Among Experts

The previous variance analysis identified significant differences in evaluation indicators among experts (Table 8). Constructing IPA models for different expert groups allows for a comprehensive understanding of their distinct perspectives on exhibition building facilities. This approach provides targeted recommendations to improve user satisfaction and enhance facility quality.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of IPA models across different expert groups.

In summary, experts from different fields prioritize distinct aspects when evaluating the environmental quality of exhibition building places in small- and medium-sized cities. Architects focus on spatial design and urban development conditions, government officials emphasize proximity to transportation hubs and parking availability, and exhibition operations managers highlight site accessibility and circulation efficiency. These differences reflect the unique perspectives and priorities of each expert group in assessing the quality of architectural environments.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Through empirical case study research, this paper identifies shortcomings and areas for improvement in the environmental quality of various sample places. By integrating user and expert evaluations and constructing an IPA model, this study highlights key improvement areas while revealing both consistencies and differences in assessments. This enhances the understanding of place environmental characteristics and provides valuable recommendations for optimizing design and planning.

6.1. Analysis of Similarities and Differences in the Evaluation of Environmental Quality of Exhibition and Convention Buildings in Small- and Medium-Sized Cities by Users and Experts

In evaluating the environmental quality of exhibition and convention buildings in small- and medium-sized cities, there is some consensus between users and experts regarding the evaluation dimensions and basic judgments. However, significant differences emerge in their perspectives, standards, and areas of focus. Both groups agree that architectural layout, traffic conditions, facilities and equipment, and service support are core factors affecting environmental quality. They emphasize the comfort and functionality of spaces, the rational organization of exhibition areas, the convenience of traffic flow, and the adequacy of facilities and commercial services. Overall, both users and experts recognize the importance of coordinating exhibition and convention buildings with the surrounding urban environment to enhance environmental quality and user experience.

Despite this consensus, noticeable differences exist in evaluation standards and emphasis. Users’ evaluations are largely based on direct experience and subjective perception, with a focus on aspects such as traffic convenience, facility usability, and the atmosphere created by advertising and promotions. For example, regarding traffic conditions, users prioritize the availability of parking spaces, walking distances, and access to public transportation. In terms of facilities and equipment, users emphasize factors such as air conditioning temperature, lighting brightness, and the convenience of restroom locations to enhance comfort during both exhibiting and visiting. In contrast, experts’ evaluations are more systematic and professional, concentrating on the rationality of architectural planning, the scientific organization of traffic, and the standardized management of operations. For example, experts evaluating traffic conditions are more concerned with the organization of traffic flow, the placement of entrances and exits, and the integration with the urban transportation system. In terms of visual aesthetics, experts focus more on the appeal of the building design, its alignment with the urban cultural characteristics, and the integration of the exhibition and convention building with the surrounding terrain and natural landscape.

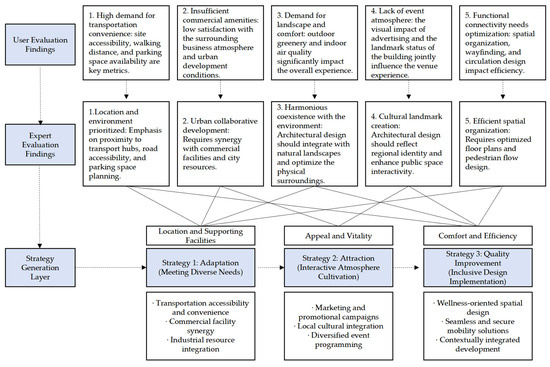

In general, while users and experts agree on basic elements and functional needs when evaluating the environmental quality of exhibition and convention buildings in small- and medium-sized cities, differences in evaluation standards and focal points emerge due to their differing perspectives and roles. By integrating users’ direct experiences with experts’ professional judgments, we established a logical chain to methodically derive the theoretical framework of the strategy generation layer (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Logical Framework for Design Strategy Generation.

6.2. Proposed Design Strategies for Enhancing the Environmental Quality of Exhibition and Convention Buildings in Small- and Medium-Sized Cities

Through a comparative analysis of convention and exhibition buildings in large versus small- and medium-sized cities, this study demonstrates that the development of such buildings in smaller urban areas should not merely replicate the internationalized, comprehensive, and high-end models typical of major metropolitan centers. The findings suggest that convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities must carve out their own sustainable development path by capitalizing on local distinctiveness and enhancing the quality of their spatial environments.

This differentiated development approach underscores the critical importance of environmental quality in small- and medium-sized city venues, which is reflected in three key aspects: First, well-designed environments better meet user needs, enhancing both the experiential quality and professional standards of events. Second, spaces that incorporate local characteristics strengthen the buildings’ visual identity and appeal, creating a unique competitive advantage. Third, high-quality environments promote flexible, multifunctional use and improve operational efficiency.

According to the environmental evaluation indicators established in previous sections, this study identifies several key considerations for planning and construction in small- and medium-sized cities: (1) the comprehensive integration of local industrial and cultural resources into environmental design; (2) the seamless connection between architecture and urban space, with optimized transportation access and supporting facilities; (3) the adoption of adaptable spatial configurations to accommodate diverse event requirements; (4) the establishment of sustainable operational mechanisms that combine government leadership with market participation.

These strategies will empower convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities to effectively foster local economic growth and contribute to a more diversified and thriving exhibition industry ecosystem in China. This place-specific, characteristic-driven development approach not only aligns with the unique conditions of smaller urban areas but also plays a key role in improving their competitiveness within the exhibition industry. Building on the insights from this study, several design strategies and recommendations are proposed to provide both theoretical foundations and practical guidance for the future planning, design, and evaluation of convention and exhibition spaces.

6.2.1. “Adaptation”: Selecting Ideal Locations Based on Diverse Needs

The quality enhancement of convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities must align with the national new urbanization strategy and regional coordinated development plan. Site selection plays a critical role in improving the attractiveness of these buildings and promoting urban development. It should adhere to the quality improvement and capacity expansion requirements outlined in the “14th Five-Year Plan” for service sector development. Additionally, the construction of convention and exhibition buildings should be integrated into the urban territorial spatial planning system to ensure alignment with overall urban planning and industrial development. A strategic site selection process should prioritize the integration of transportation accessibility and urban development by positioning these buildings near major transportation hubs, such as airports and high-speed rail stations, while leveraging well-developed urban transit networks to attract a wider range of exhibitors and visitors. Additionally, conference and exhibition buildings should be situated in areas with established urban infrastructure and a vibrant commercial atmosphere, taking advantage of nearby amenities such as accommodations, dining, and entertainment to enrich the exhibition experience and sustain the place’s long-term vitality. To enhance the site’s character, natural landscapes such as waterfront areas and park greenery should be integrated to create an ecological, green, and inviting environment, strengthening the building’s appeal and uniqueness. Additionally, incorporating the city’s historical and cultural resources into the design and operations can enrich the place’s identity. By hosting unique exhibitions and cultural activities, the city’s cultural influence can be increased, generating both economic and social benefits. A strategic approach to site selection and development not only enhances the attractiveness of conference and exhibition buildings but also injects new vitality into urban growth.

6.2.2. “Attraction”: Creating a Vibrant Urban Environment with an Interactive Atmosphere

As key hubs of urban public life, conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities can serve as catalysts for fostering vibrant urban environments. The concept of cultural governance should be deeply integrated into the creation of place environments. The environmental quality plays a crucial role in attracting visitors and shaping activities. First, the public space atmosphere should be a core focus, with an emphasis on creating open, interactive spaces and developing a diverse, multifunctional public space system. Second, in line with the Guidelines on Implementing the Project to Inherit and Promote the Finest Traditional Chinese Culture, convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities must emphasize the architectural cultural significance and serve as landmarks. These buildings should adopt an integrated “exhibition + tourism” functional model, acting as contemporary vessels for conveying urban cultural memory. The cultural and iconic value of the architecture should be enhanced by incorporating local cultural elements into the design and drawing inspiration from traditional architectural symbols and cultural motifs. This approach helps establish a distinctive regional identity, transforming these buildings into cultural landmarks within the city. Additionally, the organization of functional spaces and pedestrian flow should be optimized to prevent congestion, enhance comfort, and improve operational efficiency. Finally, conference and exhibition buildings should be transformed into dynamic urban hubs by hosting unique exhibitions, cultural festivals, and interactive events that attract both residents and tourists. This integration with urban life fosters greater social engagement while enhancing the buildings’ influence and overall benefits.

6.2.3. “Quality Improvement”: Creating Comfortable Public Environments with Inclusive Design

The preliminary research and user evaluation studies reveal that multiple factors—including walking distance to exhibition halls, convenience and safety of circulation routes, fatigue perception among elderly visitors, as well as special needs for accessible facilities among vulnerable groups (such as the elderly and parents with infants)—collectively underscore the necessity of considering diverse user groups in convention and exhibition building design. These findings are strongly corroborated by the authors’ field investigation results. It is particularly noteworthy that exhibition activities in China’s small- and medium-sized cities are predominantly composed of seasonal fairs and promotional exhibitions, which typically attract an aging demographic. Therefore, incorporating inclusive design principles to accommodate the needs of various user groups holds significant practical importance for convention and exhibition architecture in these urban contexts. Accessibility features such as barrier-free pathways, ramps, and signage should be integrated to ensure a user-friendly environment for all visitors, including individuals with disabilities. The spatial organization should prioritize seamless circulation, reducing walking distances, and enhancing connectivity between functional areas. Additionally, intelligent facility management and smart guidance systems can be introduced to improve navigation and operational efficiency. By implementing these inclusive design strategies, conference and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities can provide a more comfortable, accessible, and engaging public environment, ultimately enhancing user satisfaction and urban vitality. Furthermore, enhancing barrier-free facilities will ensure a seamless and comfortable experience for diverse user groups, reinforcing the principles of inclusive and human-centered design. To ensure harmonious integration between architecture and the environment, the building’s scale should be thoughtfully coordinated with surrounding structures and topography. Strategic design choices in scale, form, and landscape transitions can create a seamless connection between conference and exhibition buildings and their urban context. This approach enhances both aesthetic appeal and functional cohesion while providing residents and visitors with inviting spaces for leisure, entertainment, and cultural engagement. Ultimately, these efforts strengthen the public value of conference and exhibition buildings, positioning them as dynamic hubs of urban vitality.

6.3. Limitations of the Study

Limitations in research methodology: This study systematically constructs a place environment quality evaluation system for convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities using a structured subjective assessment approach. The indicator selection process is based on rigorous scientific reasoning and practical applicability. Although the adopted importance–performance analysis (IPA) model effectively visualizes user-perceived importance and actual performance within a two-dimensional matrix—offering decision makers valuable insights for prioritizing improvements—it presents three key limitations: First, the IPA results cannot accurately reflect the absolute numerical characteristics of the data. Second, the study does not yet incorporate quantitative evaluations of the objective physical environment. Third, while the evaluation indicators were derived from extensive preliminary research—including interviews and literature reviews—and were subsequently optimized, the current framework lacks a fully developed and systematic structure for indicator system construction. Specifically, there is a lack of quantitative measurement and analysis of key environmental factors such as spatial accessibility and thermal comfort. Future research should prioritize in-depth quantitative studies of core indicators, including but not limited to (1) user acceptance thresholds for accessibility via various transportation modes; (2) correlation analysis between physical environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, humidity, and wind speed) and user comfort levels; (3) integrated subjective and objective evaluations of lighting quality; and (4) the development of a comprehensive evaluation indicator system, with final weighting determined through structured methodologies such as the Delphi method and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

Limitations in case samples: Although the preliminary research was thorough, with careful consideration given to the typicality and representativeness of selected cases, there is still room for improvement in terms of sample size and geographical distribution. The current sample does not adequately capture regional climatic diversity, which is particularly important in studies focused on environmental comfort. Future research should expand the sample size, especially in investigations of thermal and outdoor environmental comfort, and give greater consideration to regional climatic differences.

Limitations in expert survey: The expert survey in this study mainly involved professionals encountered by the authors and their team through recent engineering projects, as well as individuals recognized for their specialized expertise. Although the respondents offer a certain level of representativeness, the overall sample size remains limited due to constraints such as the number of available experts, their areas of specialization, and varying perspectives. These factors may impact the generalizability and accuracy of the findings. Future research should aim to broaden the scope of survey distribution and increase both the number and diversity of expert participants to improve the representativeness, precision, and reliability of the results.

Limitations in disciplinary scope: This study presents certain limitations in terms of disciplinary perspective. While it is rooted in architectural theory and integrates relevant concepts from place theory, environmental psychology, and urban planning, our in-depth research reveals that the sustainable development of convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities extends beyond these domains. It encompasses multiple dimensions—such as decision-making mechanisms, policy support, and operational management—that require broader theoretical support from disciplines including decision science, management studies, and exhibition economics. The current reliance on a singular architectural perspective is insufficient to fully address the complex, systemic challenges involved, thereby limiting the practical applicability of the research findings to some extent. Future studies should prioritize interdisciplinary research by integrating theories and methodologies from various fields to establish a more comprehensive framework for sustainable development. This broadened approach aims to offer more systematic theoretical support and practical guidance for the whole-life-cycle management of convention and exhibition buildings in small- and medium-sized cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.L. and Y.X.; Methodology: J.L.; Software: Y.X.; Validation: P.D.; Formal Analysis: Y.X.; Investigation: J.L. and Y.X.; Resources: J.L. and P.D.; Data Curation: Y.X.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Y.X.; Writing—Review and Editing: Y.X. and J.L.; Visualization: Y.X.; Supervision: J.L. and P.D.; Project Administration: J.L. and P.D.; Funding Acquisition: J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the Architectural Design and Research Institute of SCUT for providing project drawings and data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Rizhao International Expo Center (RZ) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2019 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 239.086 | Floor Area | 399,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 449,500 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition, Hotel, Theater | Design Organization | China Architecture Design & Research Group (Beijing, China) | ||

| City | Rizhao, Shandong | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 3.8 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 3406 | Layout Characteristics | Decentralized layout with exhibition halls, theater, and hotel arranged separately. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 2390.86 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 20 m | Number of Halls | 6 | Meeting Area | 2000 m2 | A 2000 m2 Multi-function Hall. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 0 | Main Hall Area | 5500 m2 | Number of Booths | 438 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 1 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Shouguang International Convention and Exhibition Center (SG) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2000 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 102.87 | Floor Area | 70,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 150,000 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition | Design Organization | - | ||

| City | Shouguang, Shandong | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 1.35 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 1275 | Layout Characteristics | Decentralized layout with exhibition halls developed in multiple phases. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 70,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 10 m | Number of Halls | 8 | Meeting Area | 1000 m2 | Approximately 500 m2 for public space, about 50 m2, and a 35 m2 meeting room. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 15,000 m2 | Main Hall Area | 5500 m2 | Number of Booths | 1200 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 3 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Zhumadian International Convention and Exhibition Center (ZMD) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2019 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 309.72 | Floor Area | 167,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 333,000 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition, Theater | Design Organization | COSPACE DESIGN GROUP (Shanghai, China) | ||

| City | Zhumadian, Henan | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 2.0 | Urban Location | Suburban | Parking Spaces | 1093 | Layout Characteristics | Enclosed layout featuring exhibition halls, a conference center, and a performance center arranged around a central space. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 54,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 15.6 m | Number of Halls | 7 | Meeting Area | 19,200 m2 | A 3000 m2 multi-function hall, a 1600 m2 large meeting room, two 800 m2 medium-sized meeting rooms, eight VIP rooms, and a 22,300 m2 performing arts center. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 4000 | Main Hall Area | 8200 m2 | Number of Booths | 3000 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 4 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Xinyang Baihua Convention and Exhibition Center (XY) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2011 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 102.87 | Floor Area | 78,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 78,000 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition | Design Organization | - | ||

| City | Xinyang, Henan | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 0.7 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 660 | Layout Characteristics | Comb-shaped: exhibition halls are located on both sides of an indoor corridor. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 21,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 20 m | Number of Halls | 4 | Meeting Area | 1200 m2 | A 1200 m2 Conference Hall | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 30,000 m2 | Main Hall Area | 4100 m2 | Number of Booths | 824 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 1 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Jinjiang International Convention and Exhibition Center (YW) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2020 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 336.35 | Floor Area | 99,500 m2 | Total Land Area | 120,500 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition | Design Organization | Architectural Design & Research Institute of SCUT Co., Ltd.(Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) | ||

| City | Jinjiang, Fujian | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 0.98 | Urban Location | Suburban | Parking Spaces | 1246 | Layout Characteristics | Comb-shaped: exhibition halls are located on both sides of an outdoor corridor. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 48,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 12 m | Number of Halls | 4 | Meeting Area | 2412 m2 | A 722 m2 meeting room, a 1209 m2 banquet hall, a 481 m2 meeting room, and a first-floor meeting room that can be divided into four smaller rooms using movable partitions. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 5600 | Main Hall Area | 8100 m2 | Number of Booths | 2016 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 4 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Yiwu International Convention and Exhibition Center (YW) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2009 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 205.562 | Floor Area | 240,000 m | Total Land Area | 146,000 | Function | Convention, Exhibition, Hotel, Business | Design Organization | - | ||

| City | Yiwu, Zhejiang | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 1.8 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 700 | Layout Characteristics | Comb-shaped: exhibition halls are connected by corridors, each spanning two floors. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 100,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 11 m | Number of Halls | 14 | Meeting Area | 1000 m2 | A 7600 m2 hall, a 1000 m2 conference room, and multiple 27 m2 meeting rooms | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 0 | Main Hall Area | 7600 m2 | Number of Booths | 5300 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 4 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Putian Convention and Exhibition Center (PT) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2018 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 307.07 | Floor Area | 109,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 52,300 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition | Design Organization | Xiamen China Northeast Architectural Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd.(Xiamen, Fujian, China) | ||

| City | Putian, Fujian | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 0.9 | Urban Location | Suburban | Parking Spaces | 940 | Layout Characteristics | Independent: exhibition halls and conference rooms are distributed vertically across two floors. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area | 20,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 5 m | Number of Halls | 2 | Meeting Area | 9289 m2 | A 3480 m2 multi-function hall, a 3280 m2 banquet hall, five VIP rooms ranging from 64.74 m2 to 270.1 m2, three meeting rooms ranging from 159.3 m2 to 262.08 m2, a 616 m2 press center, four VIP lounges ranging from 66 m2 to 93 m2, and four negotiation rooms ranging from 76 m2 to 107 m2. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area | 8000 m2 | Main Hall Area | 5724 m2 | Number of Booths | 600 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 19 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Shengze International Convention and Exhibition Center (SZ) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2014 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 336.35 | Floor Area | 38,657 m2 | Total Land Area | 51,660 m2 | Function | Exhibition | Design Organization | Shandong Provincial Architectural Design & Research Institute Co., Ltd.(Jinan, Shandong, China) | ||

| City | Shengze, Jiangsu | Total Investment(Billion CNY) | 0.98 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 270 | Layout Characteristics | Independent: parking on the first floor, exhibition halls on the second floor. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 10,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 15 m | Number of Halls | 1 | Meeting Area | 2000 m2 | The venue includes a 1000 m2 meeting room, a 500 m2 meeting room, a 300 m2 meeting room, and a 200 m2 meeting room. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 0 | Main Hall Area (m2) | 10,000 m2 | Number of Booths | 300 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 4 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Dongying International Convention and Exhibition Center (DY) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2009 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 389.91 | Floor Area | 37,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 176,600 m2 | Function | Convention, Huatai groupon | Design Organization | Huatai group (Dongying, Shandong, China) | ||

| City | Dongying, Shandong | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 1.26 | Urban Location | Suburban | Parking Spaces | 2000 | Layout Characteristics | Independent: exhibition halls are connected in the center, with a public corridor on one side and a cargo entrance on the other. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 23,679 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 23 m | Number of Halls | 3 | Meeting Area | 5153 m2 | The venue includes a 1920 m2 meeting room, a 1300 m2 meeting room, a 530 m2 meeting room, a 700 m2 meeting room, a 289 m2 meeting room, and two 450 m2 meeting rooms. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 0 | Main Hall Area (m2) | 6000 m2 | Number of Booths | 836 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 16 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Taizhou International Expo Center (TZ) | |||||||||||||

| Year | 2010 | City GDP (2023) (Billion CNY) | 673.17 | Floor Area | 160,000 m2 | Total Land Area | 126,700 m2 | Function | Convention, Exhibition | Design Organization | Tus-Design Group Co., Ltd.(Suzhou, Jiangsu, China) | ||

| City | Taizhou, Jiangsu | Total Investment (Billion CNY) | 2.6 | Urban Location | City Center | Parking Spaces | 548 | Layout Characteristics | 42 meeting rooms, each approximately 100 m2, dozens of 30 m2 negotiation rooms, a 3000 m2 main conference hall, and a dining center featuring a 3000 m2 hall along with 8 private dining rooms. | ||||

| Exhibition Space Indicators | Meeting Space Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Indoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 60,000 m2 | Hall Clear Height | 16 m | Number of Halls | 8 | Meeting Area | 5565 m2 | 42 meeting rooms, each approximately 100 m2, dozens of 30 m2 negotiation rooms, a 3000 m2 main conference hall, and a dining center with a 3000 m2 hall and 8 private dining rooms. | |||||

| Outdoor Exhibition Area (m2) | 10,000 m2 | Main Hall Area (m2) | 11,880 m2 | Number of Booths | 2000 | Number of Meeting Rooms | 42 | ||||||

| Research Photos | Global Integration | Time Accessibility | |||||||||||

|  |  |  | ||||||||||

References

- Chenhao, F.; Zhao, M. China”s New Corresponding “Dual Circulation Economy”: Trend of Urban Development and Planning Strategies. Urban Plan. J. 2022, 1, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. Research on the Architectural Programming Elements of Conference and Exhibition Buildings in Small and Medium-Sized Cities; South China University of Technology: Guangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kusch, K. Conference and Exhibition Buildings Design and Construction Manual; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y. Introduction to the Types of Conference and Exhibition Buildings; South China University of Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F. Exploration and Practice of the Development of the Conference and Exhibition Industry in Small and Medium-Sized Cities; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Huazhong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Louviere, J.J. The Determinants of Convention Site Selection: A Logistic Choice Model from Experimental Data. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, P.-A.; Ritchie, J.-R.-R.; Arsenault, J. A Study of the Decision Process of North American Associations Concerning the Choice of a Convention Site; Quebec Planning and Development Council: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. The Mode of Site Selection and Facility Planning for Exhibition Centers in Germany. Urban Plan. 2003, 27, 32–39,48. [Google Scholar]