Influence of High-Density Community Spaces on the Walking Activity of Older Adults: A Case Study of Macau Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

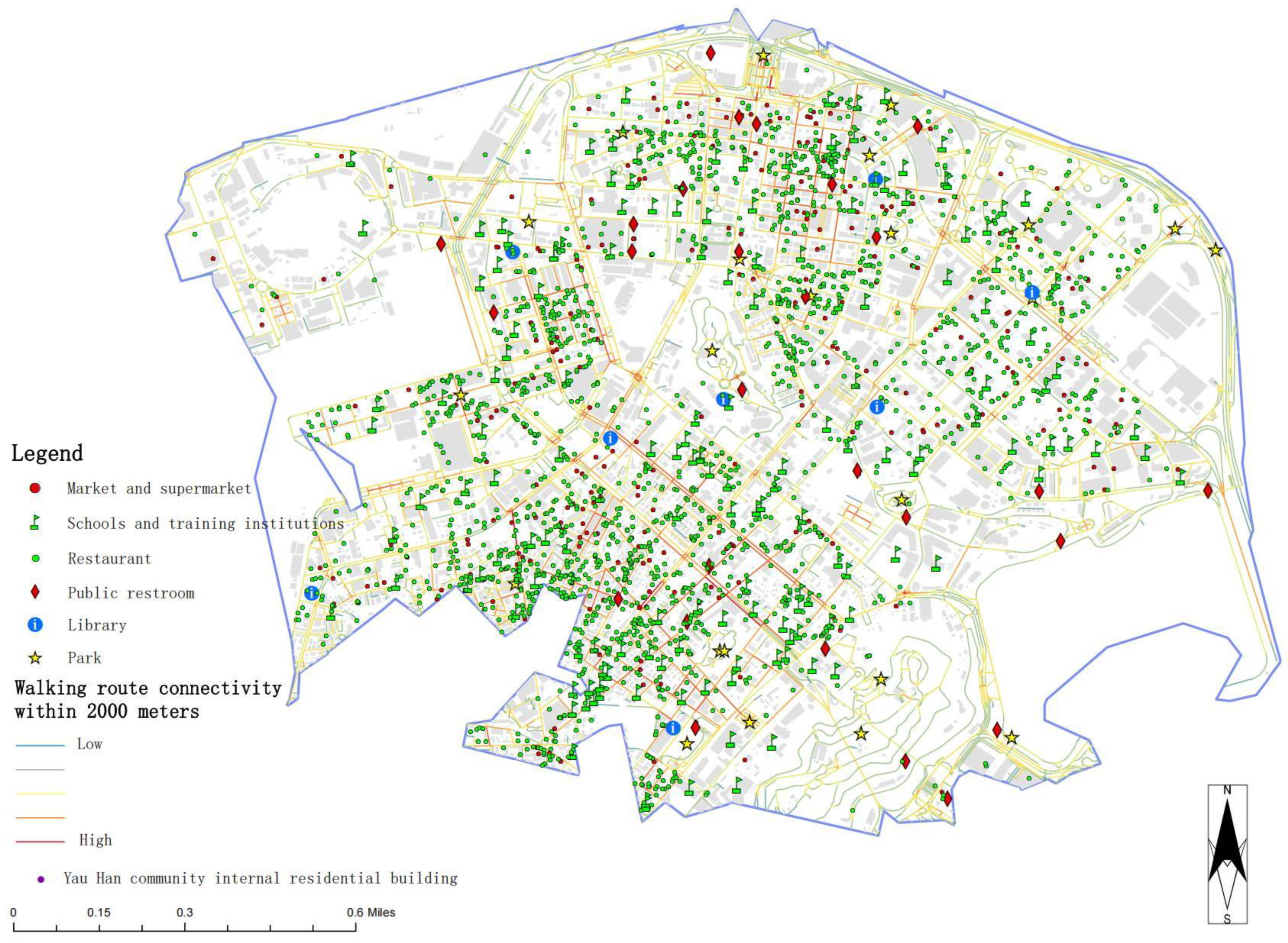

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Data Sources and Methods

- Macau-wide Point of Interest (POI) data (source: https://www.openstreetmap.org/, accessed on 6 November 2024).

- City-scale AutoCAD (2024) maps.

- Road network data extracted and processed from OpenStreetMap.

4. Results

4.1. Macau Peninsula Community Research and Analysis

4.1.1. Analysis of Outing Frequency and Walking Distance Patterns

4.1.2. Outing Activities and Preferences

- (1)

- Recreational Walking: Parks were the most frequently visited destination (25.3%), revealing their critical support for older adults’ ambulatory routines. This spatial preference underscores the significance of urban green spaces in supporting geriatric well-being.

- (2)

- Shopping Behavior: Supermarkets dominated as primary destinations (25.3%), reflecting older adults’ prioritization of daily necessities. This spatial concentration aligns with routine provisioning behaviors characteristic of compact urban environments.

- (3)

- Work-Related Mobility: Workplaces constituted a primary destination (23.55%), with a notable overlap in park and supermarket visits, suggesting integration of occupational and personal activities.

- (4)

- Dining Preferences: Restaurants were the predominant dining destination (24.86%), demonstrating their functional specificity in meal-related mobility. Additionally, these spaces serve as social hubs for older adults, where communal dining fosters interpersonal connections and community bonds.

- (5)

- Child Transportation: Schools served as the primary destination (22.78%) for child pick-up and drop-off activities, demonstrating the active role of older adults in family education.

- (6)

- Dog Walking: Parks and supermarkets maintained comparable visitation rates, indicating flexible mobility patterns among older adult dog owners.

- (7)

- Social Activities: Destination choices were relatively scattered, though the notably high library visitation rates may indicate specific event-driven gathering or group-oriented preferences.

- (1)

- The 60–69 Age Group: This cohort shows diverse activity patterns, frequently visiting parks, supermarkets, workplaces, and restaurants. Their high engagement in walking, shopping, working, and dining activities demonstrates an active and socially engaged lifestyle.

- (2)

- The 70–79 Age Group: Older adults frequently visit supermarkets and restaurants, but workplace attendance decreases, in line with retirement trends.

- (3)

- The 81–84 and 85+ Age Groups: These groups show a significant reduction in activity levels, with an increased reliance on basic facilities such as parks and supermarkets. However, their visit frequency is lower compared to younger groups. Members of the 85+ group rarely engage in physically demanding activities such as work or school runs and have minimal participation in dining out or social events.

4.1.3. Walking Space Pathway Factors and Activity Facilities That Influence Activity

4.2. Basic ArcGIS Database Construction and Analysis of the Status Quo Situation of Community Public Space

4.2.1. Analysis of Integration, Choice, and Connectivity of Public Space

4.2.2. Analysis of Facility Sites and Activity Facilities Within Different Walking Distances

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Survey Questionnaire

- 1. Your age: [Single-Choice Question] *

- ○60–69 years

- ○70–79 years

- ○80–84 years

- ○85+ years

- 2. Number of trips per week: 1–7 times [Fill in the blank] *

- _________________________________

- 3. You are about ______ [Single-choice question] *

- ○Less than 400 m (about 5 min)

- ○400–800 m (5–10 min)

- ○800–1200 m (10–15 min)

- ○1200–2000 m (15–25 min)

- ○2000–3000 m (25–40 min)

- ○3000–4000 m (40–50 min)

- ○Above 4000 m (50+ min)

- 4. An acceptable walking distance (one that is comfortable and not tiring) is ______ [Single-choice question] *

- ○Less than 400 m (about 5 min)

- ○400–800 m (5–10 min)

- ○800–1200 m (10–15 min)

- ○1200–2000 m (15–25 min)

- ○2000–3000 m (25–40 min)

- ○3000–4000 m (40–50 min)

- ○Above 4000 m (50+ min)

- 5. Tolerated walking distance (maximum acceptable walking distance) is ______ [Single-choice question] *

- ○Less than 400 m (about 5 min)

- ○400–800 m (5–10 min)

- ○800–1200 m (10–15 min)

- ○1200–2000 m (15–25 min)

- ○2000–3000 m (25–40 min)

- ○3000–4000 m (40–50 min)

- ○Above 4000 m (50+ min)

- 6. Activities you do when you go out [Multiple-choice 1uestion] *

- □Recreational Walking

- □Dog Walking

- □Child Transportation

- □Shopping

- □Dining

- □Participation in Events/Meetings

- □Work-Related Mobility

- □Other_________________

- 7. Where do you usually go when you go out? [Multiple-choice question] *

- □Park

- □Restaurant

- □Supermarket

- □School

- □Library

- □Workplace

- □Other _________________

- 8. Factors affecting the condition of the walking trail for the event [Multiple-choice question] *

- □Road width

- □Separate footpaths

- □Proportion of hard-surfaced roads

- □Roadside landscaping

- □Obstacles, such as parking, littering, and other encroachment factors on the trail

- □Overpasses and underpasses

- □Pedestrian flow

- □Other_________________

- 9. Please choose your favorite activity facility [Multiple-choice question] *

- □Fitness equipment, chess tables and chairs, courts, and other activity facilities

- □Shade and shelter from the sun and rain

- □Nighttime lighting facilities

- □Barrier-free design, e.g., ramps, blind corridors, stair railings, etc.

- □Trashcans

- □Rest facilities such as chairs

- □Other permanent landscaping such as flower beds, greenery, sculptures, etc.

- □Public toilets

- □Inspirational meeting

- □Other_________________

References

- Harper, S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science 2014, 346, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Macau Special Administrative Region. Macao Population Forecast (2022–2041); Documentation and Information Dissemination Centre of DSEC: Macau, China, 2023. Available online: https://www.dsec.gov.mo/getAttachment/54879f3c-21b7-4759-a35a-ba177765f28b/C_PPRM_PUB_2021_Y.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X. The relationship between walking ability, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly people after controlling demographic, health status, and lifestyle variables. Medicine 2023, 102, e34403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shi, R.; Niu, F. Optimization of furniture configuration for residential living room spaces in quality elderly care communities in Macao. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Code for Classification of Urban Land Use and Planning Standards of Development Land; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011; Available online: https://www.planning.org.cn/law/uploads/2013/1383993139.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Government of Macau Special Administrative Region. Draft Consultation Text of the Master Plan of the Macau Special Administrative Region (2020–2040); Land, Public Works and Transport Bureau: Macau, China, 2020; Available online: https://www.cnbayarea.org.cn/policy/policy%20release/policies/content/post_696729.html (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Wan, Y.K.P. The social, economic and environmental impacts of casino gaming in Macao: The community leader perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.T.; Chen, Y.S. The social, economic, and environmental impacts of casino gambling on the residents of Macau and Singapore. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, P.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y. Research on key factors of public green space environment in Macau community based on sustainable development. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2023, 18, 2170359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, D.W.; Barnett, A.; Nathan, A. Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautmans, I.; Lambert, M.; Mets, T. The six-minute walk test in community dwelling elderly: Influence of health status. BMC Geriatr. 2004, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, T.; Yu, Y. Associations between built environment characteristics and walking in older adults in a high-density city: A study from a Chinese megacity. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 577140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tao, Z.; Wu, W. Influence of urban park pathway features on the density and intensity of walking and running activities: A case study of Shanghai city. Land 2024, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Cros, H.; Kong, W.H. Congestion, popular world heritage tourist attractions and tourism stakeholder responses in Macao. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, J. Measuring residents’ perceptions of city streets to inform better street planning through deep learning and space syntax. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Maruyama, K.; Saito, I. Latent profile analysis approach to the relationship between daily ambulatory activity patterns and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Japanese individuals: The Toon Health Study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2023, 28, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F. Where can the elderly walk? A spatial multi-criteria method to increase urban pedestrian accessibility. Cities 2022, 127, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Soh, K.G.; Omar Dev, R.D. Effect of brisk walking on health-related physical fitness balance and life satisfaction among the elderly: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 829367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Social needs of the elderly and active aging in public open spaces in urban renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Donovan, R.J. Relative influences of individual, social environmental, and physical environmental correlates of walking. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonzo, M.A. To walk or not to walk? The hierarchy of walking needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banger, A.; Grigolon, A.; Brussel, M. Identifying the interrelations between subjective walkability factors and walking behaviour: A case study in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 24, 101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.S.; Wu, T.J. Environmental stressors and well-being on middle-aged and elderly people: The mediating role of outdoor leisure behaviour and place attachment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, H. The built environment’s nonlinear effects on the elderly’s propensity to walk. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, Y. Investigating the influence of age-friendly community infrastructure facilities on the health of the elderly in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zou, G.; Shin, J. Locating community-based comprehensive service facilities for older adults using the GIS-NEMA method in Harbin, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 05021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Z. Using space syntax in close interaction analysis between the elderly: Towards a healthier urban environment. Buildings 2023, 13, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hang, T. Integrating restorative perception into urban street planning: A framework using street view images, deep learning, and space syntax. Cities 2024, 147, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Richards, D.; Lu, Y. Measuring daily accessed street greenery: A human-scale approach for informing better urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lin, Z. Spatial Accessibility Analysis and Optimization Simulation of Urban Riverfront Space Based on Space Syntax and POIs: A Case Study of Songxi County, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosaki, M.; Ohira, T.; Kajiura, M. Effects of a laughter and exercise program on physiological and psychological health among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: Randomized controlled trial. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Chadha, T.; Park, K. Measuring pedestrian-level street greenery visibility through space syntax and crowdsourced imagery: A case study in London, UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 105, 128725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L. Explaining urban economic governance: The City of Macao. Cities 2017, 61, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Hu, L.; Li, M. Urban green space accessibility changes in a high-density city: A case study of Macau from 2010 to 2015. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 66, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Z. Public green space injustice in high-density post-colonial areas: A case study of the Macau Peninsula, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.B. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaya, V.; Chardon, M.; Klein, H. What do we know about the use of the walk-along method to identify the perceived neighborhood environment correlates of walking activity in healthy older adults: Methodological considerations related to data collection—A systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.P.; Alberto, K.C.; Mendes, L.L. Neighborhood environment walkability scale: A scoping review. J. Transp. Health 2021, 23, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Research on Evaluation and Planning Application of Public Outdoor Activity Fields in Communities on Aging Adaptability. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H. Analysis of the status quo of the Elderly’s demands of medical and elderly care combination in the underdeveloped regions of Western China and its influencing factors: A case study of Lanzhou. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.D.; Tong, Y. Spatial differentiation of traditional villages using ArcGIS and GeoDa: A case study of Southwest China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chai, Y. A context-based approach for neighbourhood life circle delineation and internal spatial utilization analysis based on GIS and GPS tracking data. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 1493–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ge, J.; Bai, M. Uncovering the factors influencing the vitality of traditional villages using POI (point of interest) data: A study of 148 villages in Lishui, China. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Depthmap 4: A researcher’s handbook. Bartlett School of Graduate Studies. University College London, UK. 2004. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/2651/1/2651.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Koohsari, M.J.; Sugiyama, T.; Mavoa, S. Street network measures and adults’ walking for transport: Application of space syntax. Health Place 2016, 38, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, Z.; Pantelić, S.; Trajković, N. Age-related decrease in physical activity and functional fitness among elderly men and women. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Lara, E.; Rubio-Valera, M. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: The role of social networ. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, İ.A.; True, E.M. The perception of public space of the elderly after social isolation and its effect on health. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, C.; Mu, W. Locating Senior-Friendly Restaurants in a Community: A Bi-Objective Optimization Approach for Enhanced Equality and Convenience. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Fu, Y.; Chang, Q. Life satisfaction among older adults in urban China: Does gender interact with pensions, social support and self-care ability? Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 2026–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Song, C.; Pei, T. Accessibility to urban parks for elderly residents: Perspectives from mobile phone data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enssle, F.; Kabisch, N. Urban green spaces for the social interaction, health and well-being of older people—An integrated view of urban ecosystem services and socio-environmental justice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Chen, M. A systematic review of measurement tools and senior engagement in urban nature: Health benefits and behavioral patterns analysis. Health Place 2025, 91, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torku, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Yung, E.H.K. Age-friendly cities and communities: A review and future directions. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 2242–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency/Distance | Age | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–69 Years | 70–79 Years | 80–84 Years | 85+ Years | |||

| Number of outings per week | 1 time | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 2 |

| 2 times | (14.286%) | 2 (28.571%) | 2 (28.571%) | 2 (28.571%) | 7 | |

| 3 times | 3 (17.647%) | 9 (52.941%) | 3 (17.647%) | 2 (11.765%) | 17 | |

| 4 times | 7 (38.889%) | 8 (44.444%) | 2 (11.111%) | 1 (5.556%) | 18 | |

| 5 times | 25 (64.103%) | 11 (28.205%) | 3 (7.692%) | 0 (0%) | 39 | |

| 6 times | 23 (63.889%) | 13 (36.111%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 36 | |

| 7 times | 6 (54.545%) | 5 (45.455%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 11 | |

| Total | 65 | 48 | 11 | 6 | 130 | |

| Walking distance per outing | 1200–2000 m (15–25 min) | 9 (47.368%) | 6 (31.579%) | 4 (21.053%) | 0 (0%) | 19 |

| 2000–3000 m (25–40 min) | 37 (52.857%) | 31 (44.286%) | 2 (2.857%) | 0 (0%) | 70 | |

| 3000–4000 m (40–50 min) | 15 (60%) | 9 (36%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 25 | |

| 400–800 m (5–10 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 4 | |

| Above 4000 m (50+ min) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 | |

| 800–1200 m (10–15 min) | 1 (14.286%) | 1 (14.286%) | 3 (42.857%) | 2 (28.571%) | 7 | |

| Less than 400 m (about 5 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 | |

| Total | 65 | 48 | 11 | 6 | 130 | |

| Acceptable walking distance | 1200–2000 m (15–25 min) | 7 (46.667%) | 4 (26.667%) | 4 (26.667%) | 0 (0%) | 15 |

| 2000–3000 m (25–40 min) | 22 (43.137%) | 27 (52.941%) | 2 (3.922%) | 0 (0%) | 51 | |

| 3000–4000 m (40–50 min) | 29 (63.043%) | 16 (34.783%) | 1 (2.174%) | 0 (0%) | 46 | |

| 400–800 m (5–10 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 4 | |

| Above 4000 m (50+ min) | 6 (85.714%) | 1 (14.286%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 | |

| 800–1200 m (10–15 min) | 1 (16.667%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33.333%) | 6 | |

| Less than 400 m (about 5 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 | |

| Total | 65 | 48 | 11 | 6 | 130 | |

| Tolerance of walking distance | 1200–2000 m (15–25 min) | 2 (28.571%) | 1 (14.286%) | 3 (42.857%) | 1 (14.286%) | 7 |

| 2000–3000 m (25–40 min) | 12 (33.333%) | 19 (52.778%) | 5 (13.889%) | 0 (0%) | 36 | |

| 3000–4000 m (40–50 min) | 35 (58.333%) | 23 (38.333%) | 2 (3.333%) | 0 (0%) | 60 | |

| 400–800 m (5–10 min) | 0 (0%) min | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 | |

| Above 4000 m (50+ min) | 16 (76.19%) | 5 (23.81%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 21 | |

| 800–1200 m (10–15 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | 4 | |

| Less than 400 m (about 5 min) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 1 | |

| Total | 65 | 48 | 11 | 6 | 130 | |

| Activity Type | Park | Supermarkets | Workplace | Restaurant | School | Library | Other | Totals | X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recreational Walking | 100 (25.253%) | 87 (21.97%) | 47 (11.869%) | 74 (18.687%) | 31 (7.828%) | 29 (7.323%) | 28 (7.071%) | 396 | 122.091 | 0.000 * |

| Shopping | 100 (23.641%) | 107 (25.296%) | 50 (11.82%) | 76 (17.967%) | 35 (8.274%) | 30 (7.092%) | 25 (5.91%) | 423 | ||

| Work-Related Mobility | 57 (22.008%) | 51 (19.691%) | 61 (23.552%) | 37 (14.286%) | 24 (9.266%) | 14 (5.405%) | 15 (5.792%) | 259 | ||

| Dining | 82 (23.699%) | 73 (21.098%) | 36 (10.405%) | 86 (24.855%) | 28 (8.092%) | 22 (6.358%) | 19 (5.491%) | 346 | ||

| Child Transportation | 38 (21.111%) | 34 (18.889%) | 23 (12.778%) | 28 (15.556%) | 41 (22.778%) | 7 (3.889%) | 9 (5%) | 180 | ||

| Dog Walking | 19 (22.093%) | 22 (25.581%) | 13 (15.116%) | 14 (16.279%) | 6 (6.977%) | 6 (6.977%) | 6 (6.977%) | 86 | ||

| Participation in events/meetings | 22 (22%) | 19 (19%) | 12 (12%) | 17 (17%) | 5 (5%) | 23 (23%) | 2 (2%) | 100 | ||

| Total | 418 | 393 | 242 | 332 | 170 | 131 | 104 | 1790 |

| Category | Park | Supermarkets | Workplace | Restaurant | School | Library | Others | Recreational Walking | Shopping | Work-Related Mobility | Dining | Child Transportation | Dog Walking | Participation in Events/Meetings | Total | X2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60–69 years | 58 (11.813%) | 52 (10.591%) | 47 (9.572%) | 38 (7.739%) | 26 (5.295%) | 12 (2.444%) | 15 (3.055%) | 53 (10.794%) | 52 (10.591%) | 47 (9.572%) | 38 (7.739%) | 26 (5.295%) | 15 (3.055%) | 12 (2.444%) | 491 | 69.711 | 0.002 * |

| 70–79 years | 47 (13.352%) | 45 (12.784%) | 13 (3.693%) | 42 (11.932%) | 14 (3.977%) | 18 (5.114%) | 12 (3.409%) | 37 (10.511%) | 45 (12.784%) | 14 (3.977%) | 39 (11.08%) | 13 (3.693%) | 6 (1.705%) | 7 (1.989%) | 352 | |||

| 80–84 years | 11 (16.923%) | 8 (12.308%) | 1 (1.538%) | 6 (9.231%) | 2 (3.077%) | 3 (4.615%) | 2 (3.077%) | 11 (16.923%) | 8 (12.308%) | 1 (1.538%) | 6 (9.231%) | 2 (3.077%) | 1 (1.538%) | 3 (4.615%) | 65 | |||

| 85+ years | 4 (15.385%) | 2 (7.692%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (11.538%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.846%) | 4 (15.385%) | 6 (23.077%) | 2 (7.692%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (11.538%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.846%) | 26 | |||

| Total | 120 | 107 | 61 | 89 | 42 | 34 | 33 | 107 | 107 | 62 | 86 | 41 | 22 | 23 | 934 | |||

| Multiple-Choice Question | N (counts) | Response Rate (%) | Penetration Rate (%) | X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness equipment, chess tables and chairs, courts, and other activity facilities | 79 | 5.792 | 60.769 | 115.977 | 0.000 *** |

| Shade and shelter from the sun and rain | 121 | 8.871 | 93.077 | ||

| Night-time lighting facilities | 86 | 6.305 | 66.154 | ||

| Barrier-free design, e.g., ramps, blind corridors, stair railings, etc. | 67 | 4.912 | 51.538 | ||

| Road width | 114 | 8.358 | 87.692 | ||

| Obstacles, such as parking, littering, and other encroachment factors on the trail | 99 | 7.258 | 76.154 | ||

| Separate footpaths | 93 | 6.818 | 71.538 | ||

| Proportion of hard-surfaced roads | 101 | 7.405 | 77.692 | ||

| Roadside landscaping | 80 | 5.865 | 61.538 | ||

| Overpasses and underpasses | 20 | 1.466 | 15.385 | ||

| Pedestrian flow | 95 | 6.965 | 73.077 | ||

| Trashcans | 68 | 4.985 | 52.308 | ||

| Rest facilities such as chairs | 102 | 7.478 | 78.462 | ||

| Other permanent landscaping such as flower beds, greenery, sculptures, etc. | 80 | 5.865 | 61.538 | ||

| Public toilet | 110 | 8.065 | 84.615 | ||

| Inspirational meeting | 49 | 3.592 | 37.692 | ||

| Total | 1364 | 100 | 1049.231 |

| X | → | Y | Unstandardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | → | Sites | 31.034 | 0.123 | 6.442 | 4.817 | 0.000 *** |

| Choice | → | Sites | 0 | 0.383 | 0 | 14.047 | 0.000 *** |

| Integration | → | Sites | −0.403 | −0.392 | 0.029 | −13.91 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Wang, N.; Tang, H. Influence of High-Density Community Spaces on the Walking Activity of Older Adults: A Case Study of Macau Peninsula. Buildings 2025, 15, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091505

Chen X, Wang N, Tang H. Influence of High-Density Community Spaces on the Walking Activity of Older Adults: A Case Study of Macau Peninsula. Buildings. 2025; 15(9):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091505

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiangyu, Ning Wang, and Hua Tang. 2025. "Influence of High-Density Community Spaces on the Walking Activity of Older Adults: A Case Study of Macau Peninsula" Buildings 15, no. 9: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091505

APA StyleChen, X., Wang, N., & Tang, H. (2025). Influence of High-Density Community Spaces on the Walking Activity of Older Adults: A Case Study of Macau Peninsula. Buildings, 15(9), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091505