Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

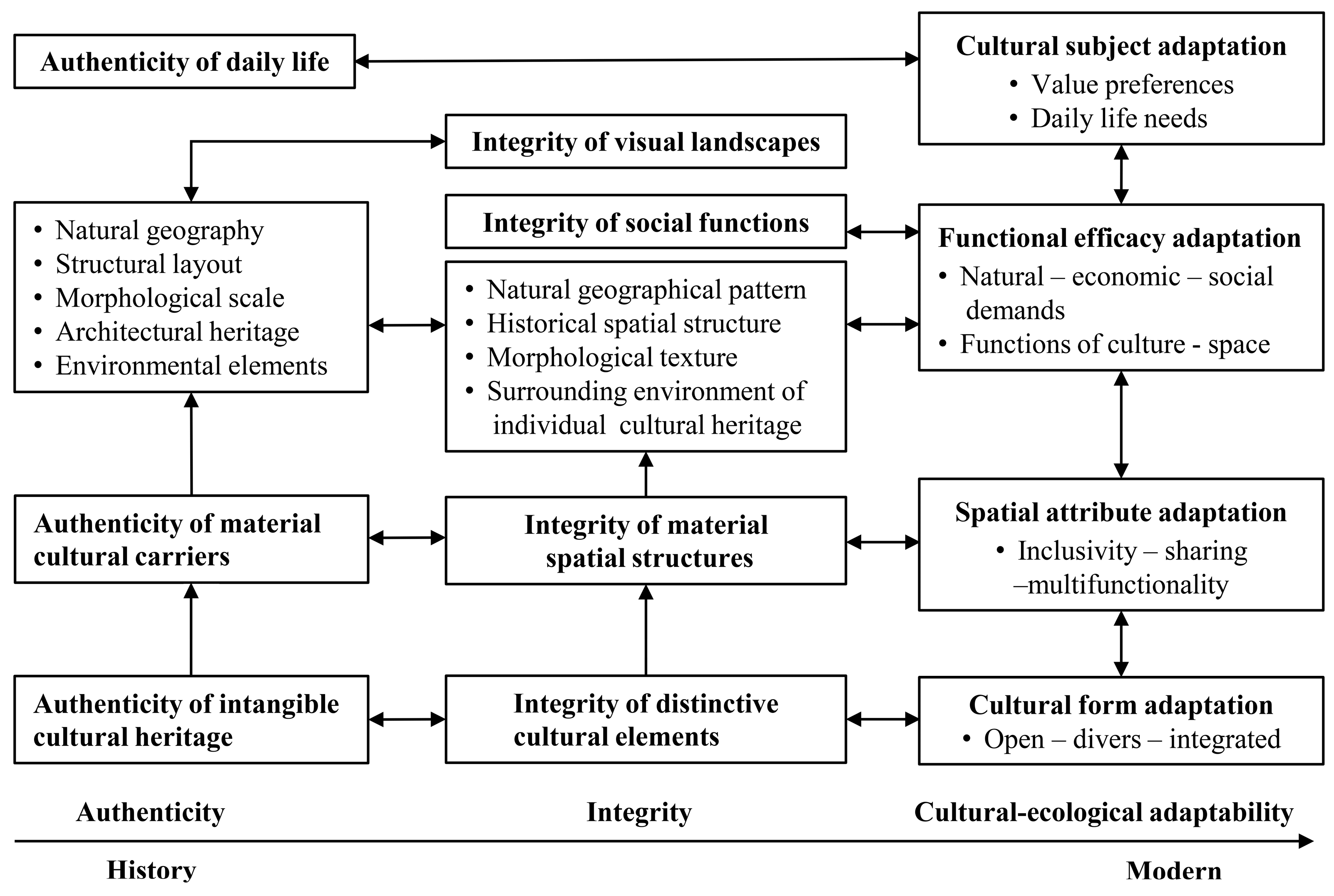

2. Theoretical Framework Construction

2.1. Authenticity

2.2. Integrity

2.3. Cultural–Ecological Adaptability

3. Materials and Methods

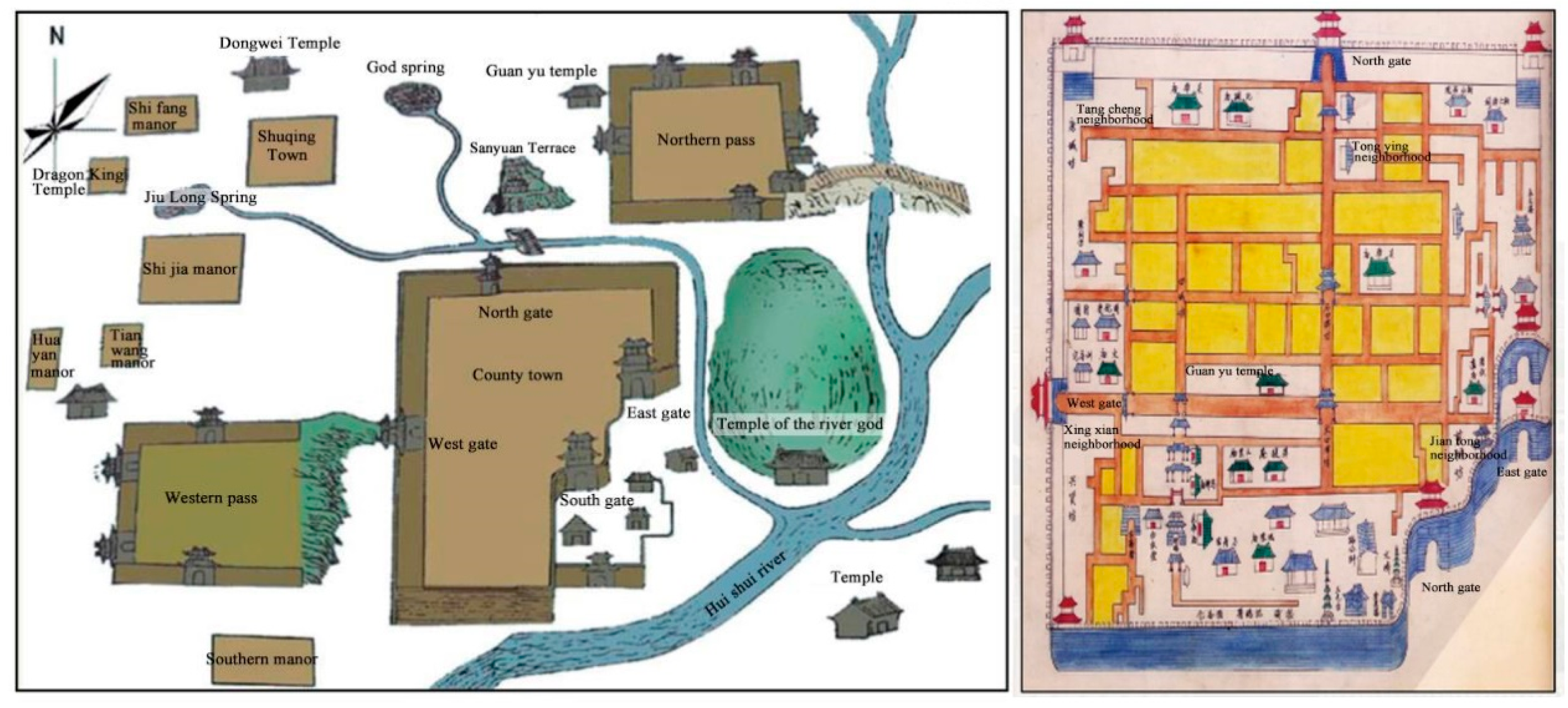

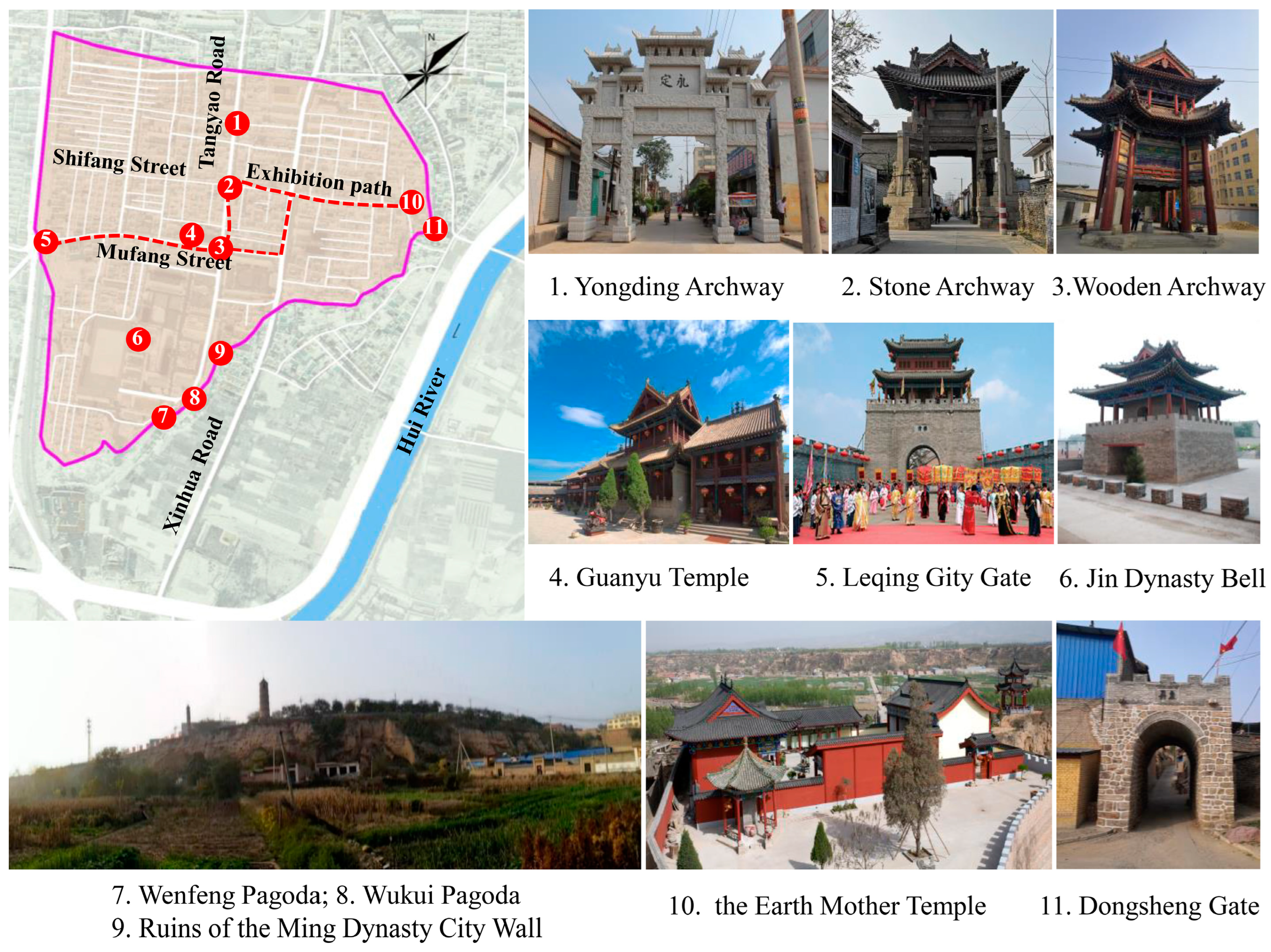

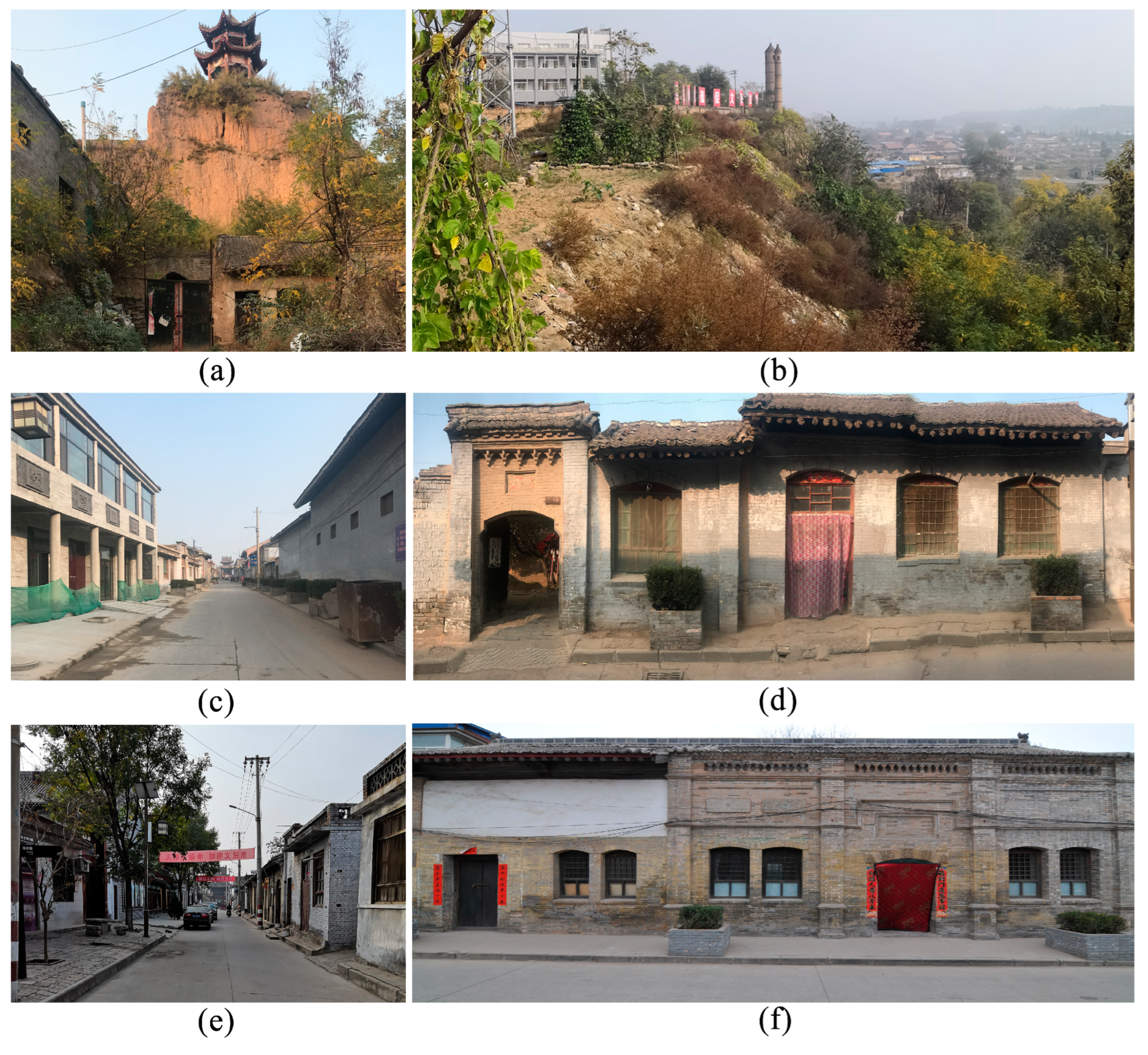

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Acquisition

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Thematic Clustering and Identification of Authenticity and Integrity Elements

3.3.2. Analysis of Real Needs for Cultural–Ecological Adaptation

- (1)

- What are the priority issues that need to be addressed in the development and construction of Yicheng Ancient City?

- (2)

- Which public service facilities need to be supplemented or improved in Yicheng Ancient City?

- (3)

- What are the urgent problems to be resolved in environmental rectification?

3.3.3. Element Comparison and Assessment of Intrinsic Connections

- (1)

- Relatively Independent Direct Conservation: Elements that are functionally clear, with minimal changes, low compatibility, and no significant interactions with other elements.

- (2)

- Mutually Inclusive Integrated Convergence: Elements that are flexible and open, with moderate changes and strong compatibility.

- (3)

- Differentiated Adaptation for Potential Conflicts: Elements that show significant changes, involving demolition and renovation, requiring targeted strategies to resolve potential conflicts.

4. Results

4.1. Distinctive Cultural Elements

4.2. Historical Evolution of Social Functions

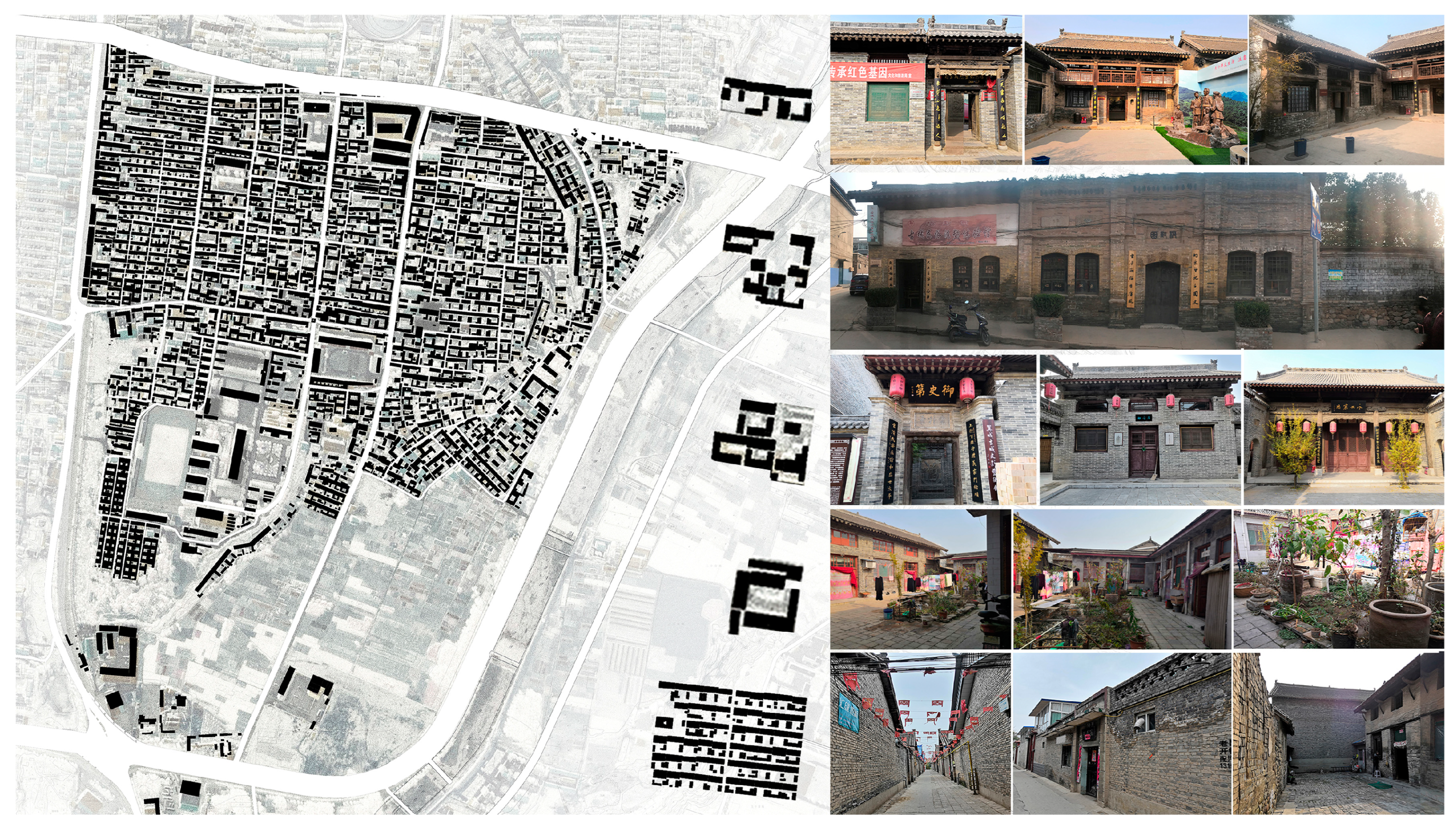

4.3. Material Cultural Carriers and Spatial Structure

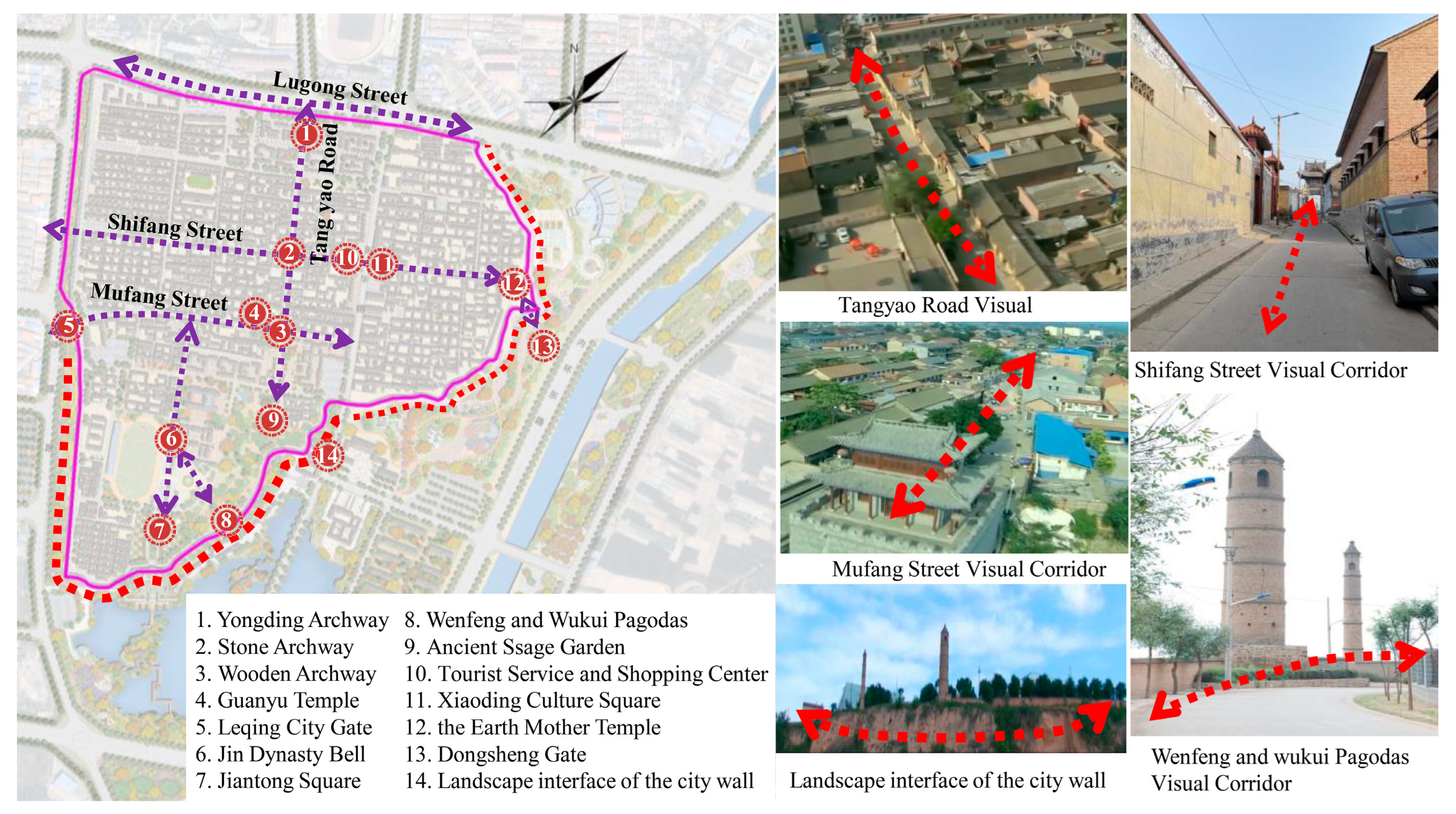

4.4. Visual Landscapes and Their Integrity

4.5. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Its Exhibition

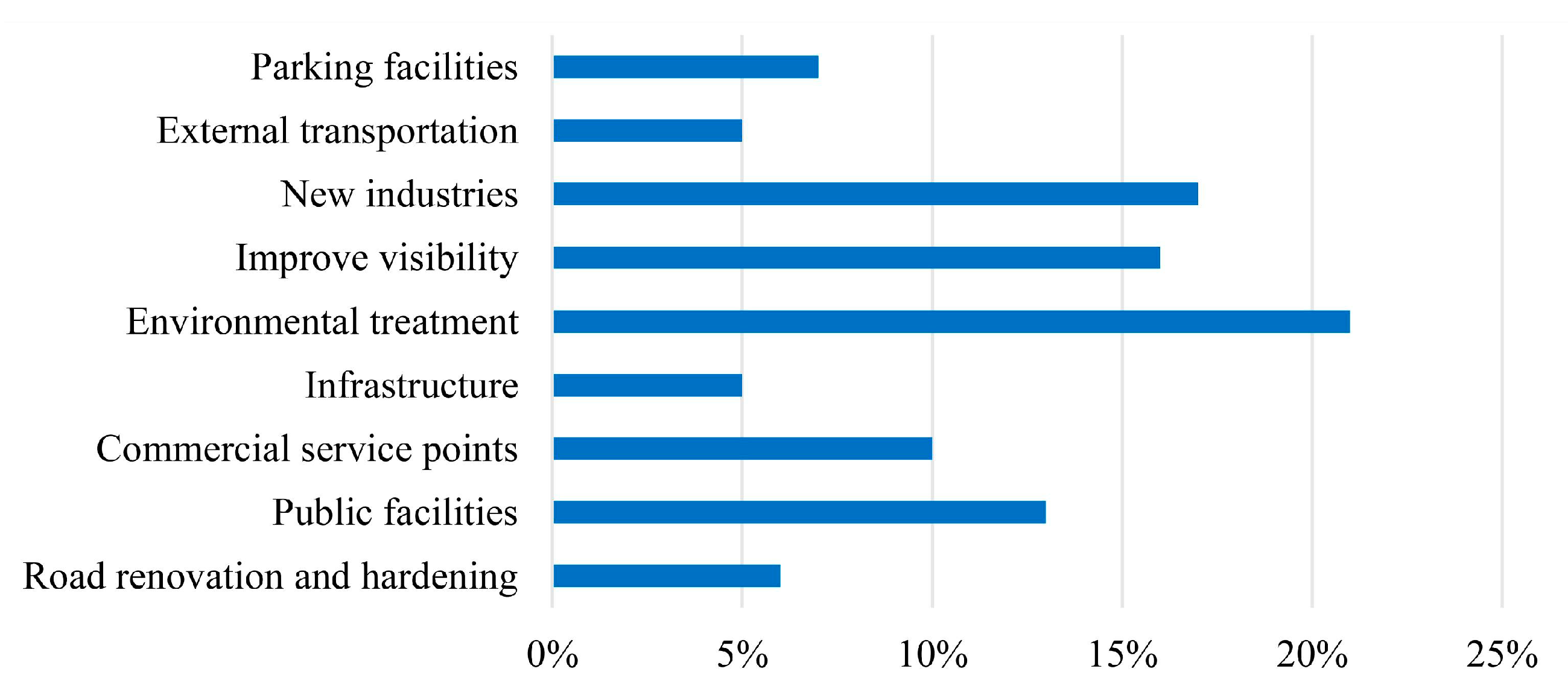

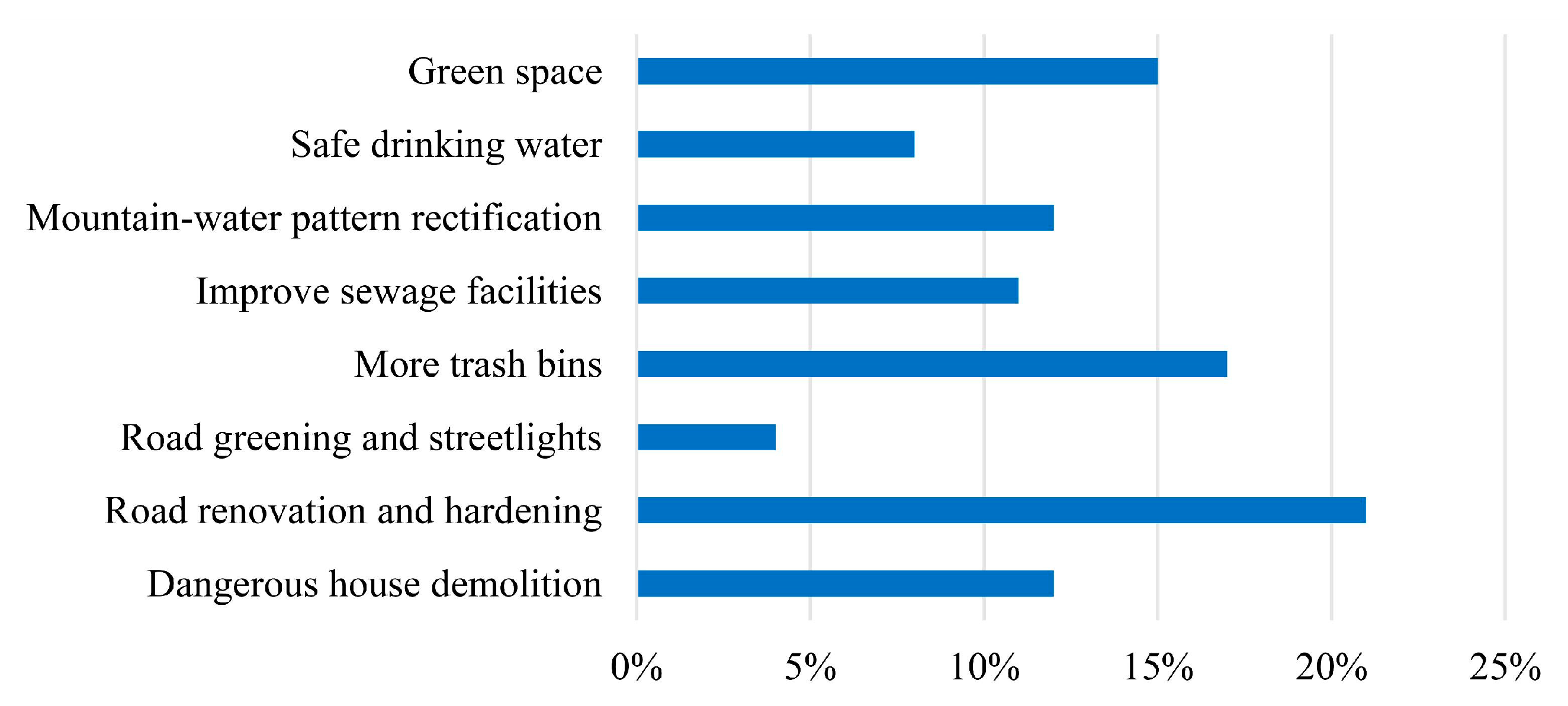

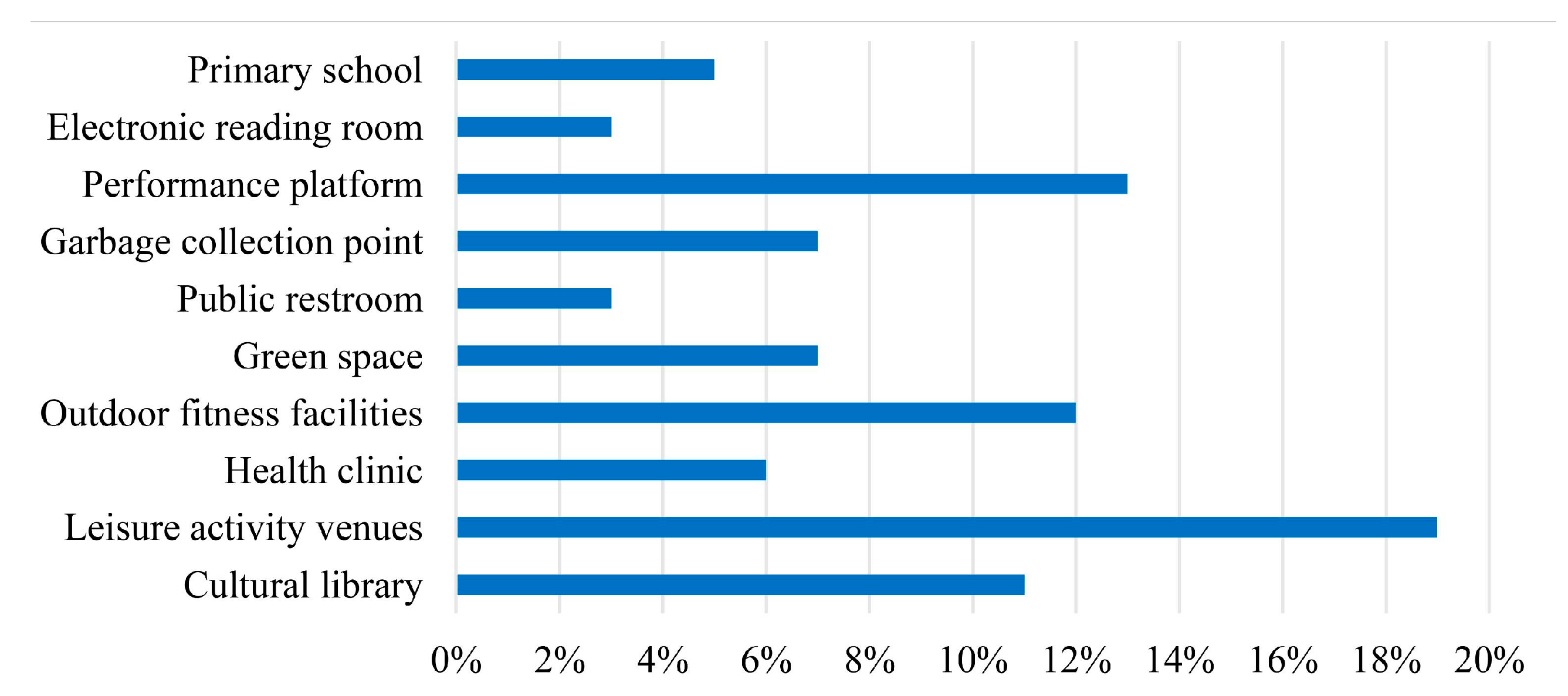

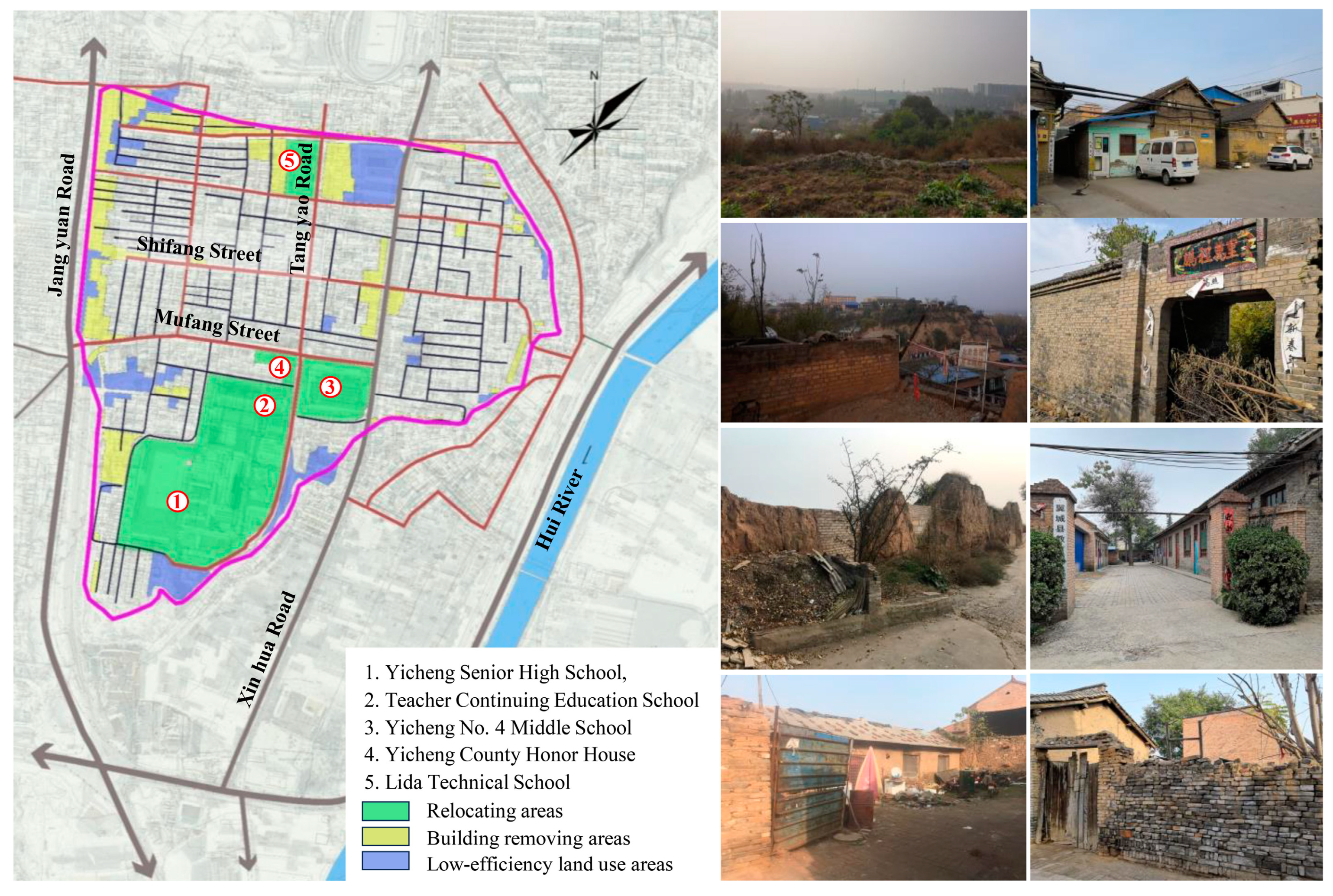

4.6. New Needs of Local Development

- Environmental treatment

- New industries

- Improve visibility

- Public facilities

- Commercial facilities and service points

- Parking facilities

- Road renovation and hardening

- More trash bins

- Green spaces

- Dangerous house demolition

- Leisure activity venues

- A performance platform

- Outdoor fitness facilities

- A cultural library

- A middle-aged resident commented: “Yicheng No. 4 Middle School and Yicheng Senior High School are located next to each other. During dismissal times, the areas near the Wooden Archway and Mufang Street become extremely congested—electric bikes can barely get through, let alone cars. Most of the alleys are too narrow for vehicles to enter, and even if they could, there’s nowhere to park. Many people have to park their cars outside the ancient city…”

- A young resident stated: “While there are some small shops in the village, they mainly sell basic school supplies and daily necessities. The tourism development initially envisioned for the village hasn’t materialized as hoped. We want the planning efforts to genuinely drive tourism here…”

- An elderly resident exercising at Guanyu Temple Square noted: “This is the only public square in the village. Everyone usually exercises and holds activities here, but it’s too small, especially during the annual Ancient City Cultural Festival when it’s overcrowded…”

- A parent renting housing to accompany their child’s studies shared: “Aside from caring for my child, there are few suitable job opportunities here. Earning extra income is difficult. We’d welcome more employment options…”

- Emphasize the commercial, entertainment, and tourism service functions of the ancient city of Yicheng.

- Planning to relocate Yicheng No. 4 Middle School, Yicheng Senior High School, the Teacher Continuing Education School, and Lida Technical School in the future.

- Planning to relocate Yicheng Honor House, with the original site designated for green space in the future.

- Protecting all historical structures within Yicheng Ancient City while integrating its historical and cultural information—rooted in the Tao Tang and Jin State period—into urban development strategies.

- Avoiding large-scale underground development until the status of underground cultural relics is thoroughly assessed.

4.7. Intrinsic Connections and Type Division

5. Discussion

5.1. Generating New Spaces and Land Resources for Returning to the Lifeworld

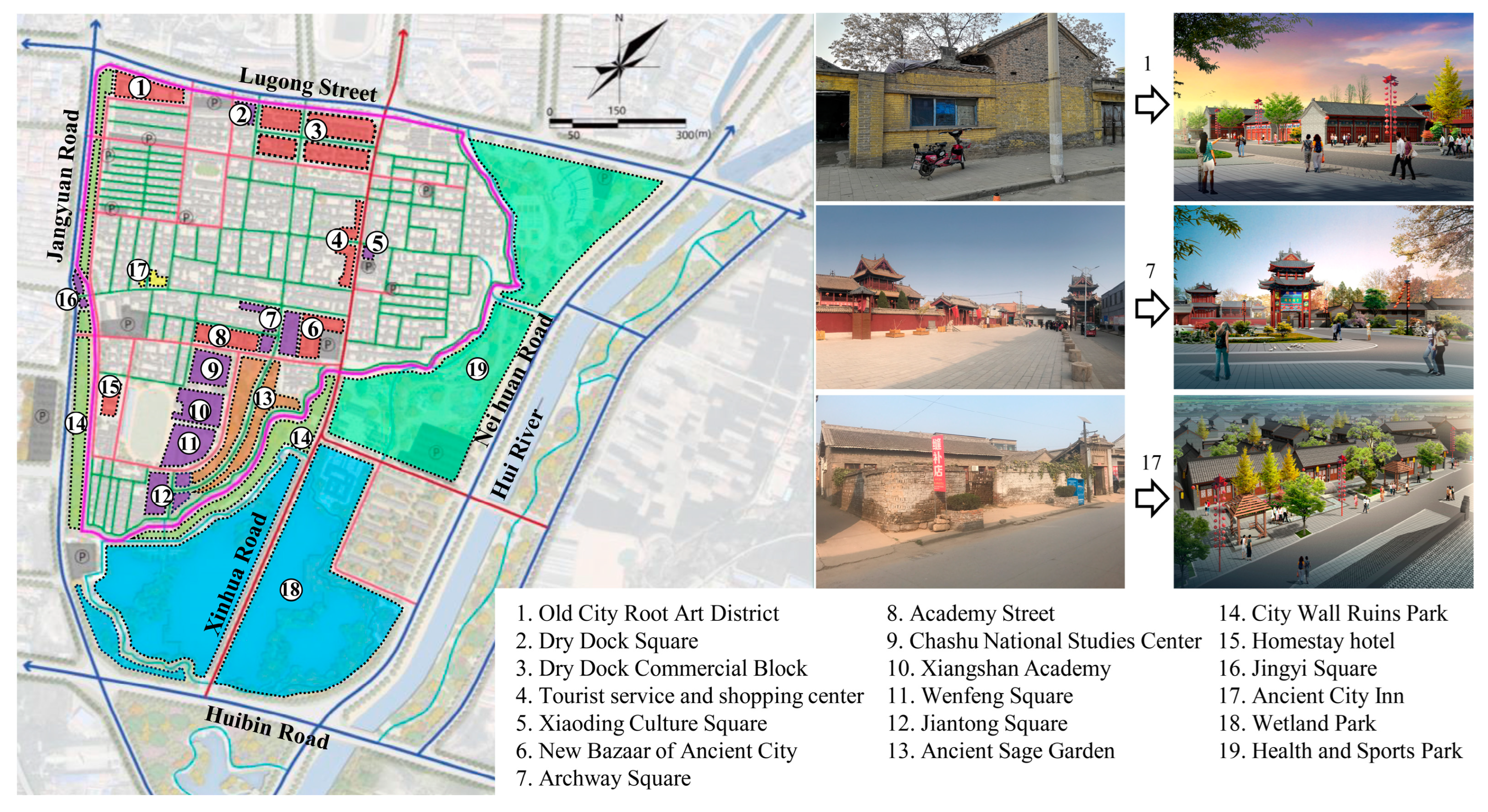

5.2. Cultural Resource Integration and Project Planning for Social Function Enhancement

5.2.1. Series on History and Landscape

5.2.2. Series on Academies and Celebrities

5.2.3. Series on Business and Services

5.2.4. Series on Folklore and Cultural Life

5.3. Authenticity and Integrity of the City Site Pattern and Spatial Structure

- Safeguarding historical boundaries by removing harmful attached structures and reinforcing the structure, slope, and escarpment.

- Integrating the gully area between the city walls and the Hui River into the protection zone to preserve the historical pattern.

- Preserving the urban spatial structure by using key historical elements—such as Tangyao Road, Mufang Street, Shifang Street, Guanyu Temple, the Wooden Archway, Stone Archway, Wenfeng Pagoda, Wukui Pagoda, Earth Mother Temple, and the recently reconstructed Leqing City Gate and West City Wall—as the foundational framework to ensure authenticity and integrity.

5.4. Authenticity and Integrity of Immovable Cultural Relics, Architectural Heritage, and Alleys

- Street dimensions: Maintain direction, width, and proportion.

- Road surface: Pave with bluestone slabs and restrict motor vehicle access.

- Advertisements and signs: Regulate form, size, color, and placement.

- Utility lines: Convert overhead cables to underground installations.

- Building facades: Preserve walls, doorways, windows, and traditional patterns.

5.5. Integrity of Visual Landscapes

5.6. Preserving and Expanding the Spatial Venues for Intangible Cultural Heritage

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Tan, L. Tourism in historic urban areas: Construction of cultural heritage corridor based on minimum cumulative resistance and gravity model—A case study of Tianjin, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.Q.; Yu, M.M. Protection and renewal about historical towns in cultural ecology view. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm, N.; Käyhkö, N.; Ndumbaro, F.; Khamis, M. Community stakeholders’ knowledge in landscape assessments—Mapping indicators for landscape services. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O.; Hyde, T.; Christie, M.; Fazey, I. The importance of deliberation in valuing ecosystem services in developing countries—Evidence from the Solomon Islands. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, E. Conservation and Planning: Changing Values in Policy and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Safarov, B.; Yi, L.; Buzrukova, M.; Janzakov, B. The adaptive evolution of cultural ecosystems along the Silk Road and cultural tourism heritage: A case study of 22 cultural sites on the Chinese section of the Silk Road World Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choay, F. The Invention of the Historic Monument; O’Connell, L.M., Translator; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Authentication: Hot and cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, S. Authenticity in world heritage cultural landscapes: Continuity and change. In New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas; Morales, F.J.L., Ed.; UNESCO Digital Library: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.F. Semantics of authenticity and cultural ecology model of heritage. City Plan. Rev. 2022, 46, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, W.X. On the essence and fundamental value of “authenticity” of traditional settlements: The comparison between two cases of Dayan ancient city and Shuhe ancient town. Architect 2010, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Cannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culler, J. Semiotics of tourism. Am. J. Semiot. 1981, 1, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudrillard, J. Simulations; Foss, P.; Patton, P.; Beitchman, P., Translators; Semiotext(e): New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Nara Document on Authenticity. In Proceedings of the Experts Meeting on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention, Nara, Japan, 1–6 November 1994; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Nara, Japan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, P.; Larcher, F. Integrity in UNESCO World Heritage Sites: A comparative study for rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y. A summary of heritage authenticity and integrity studies at home and abroad. Southeast Cult. 2010, 4, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T. Nara+20: On heritage practices, cultural values, and the concepts of authenticity. World Archit. 2014, 12, 108–109. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel, H. An overview of emerging authenticity and integrity requirements for world heritage nominations. In New Views on Authenticity and Integrity in the World Heritage of the Americas; Morales, F.J.L., Ed.; UNESCO Digital Library: Paris, France, 2005; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 2008. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide08-en.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments. International Charter on the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter); International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS): Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Nairobi Recommendation on the Conservation of Cultural Property; UNESCO: Nairobi, Kenya, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas; ICOMOS: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Xi’an Declaration on the Conservation of the Setting of Heritage Structures, Sites and Areas; ICOMOS: Xi’an, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). International Symposium on the Concepts and Practices of Conservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings in East Asia; ICOMOS: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas; ICOMOS: Valletta, Malta, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. A framework for sustainable heritage management: A study of UK industrial heritage sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. What Is OUV? Defining the Outstanding Universal Value of Cultural World Heritage Properties; Bäßler Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rössler, M. Applying authenticity to cultural landscapes. APT Bull. 2008, 39, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.G.; Wang, M. The cultural ecological adaptation and the social-cultural evolution of human being: Analysis of the theory of cultural change of the anthropologist J. H. Steward. J. Huai Hua Univ. 2012, 31, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.Y.; Qiu, G.F.; Zeng, Z.J.; Xiao, M.X. Hakka culture tourism development basing on the cultural ecology. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 32, 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.L.; Wu, H.X. Cultural adaptation and consciousness: A case study of Dong people in Huanggang village. Anthropologist 2015, 22, 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Contemporary demands of scenes in urban historic conservation areas: A case study of subjective evaluations from Foshan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Q. Protection of urban and rural cultural heritage based on cultural ecology and complex system. City Plan. Rev. 2016, 40, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.T. Ecological integrity evaluation of organically evolved cultural landscape. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 9554359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Y.P.; Li, W.; Zeng, C.; Li, C. The evaluation of cultural ecological adaptability of traditional villages and its influencing factors. J. Chin. Ecotour. 2022, 12, 504–518. [Google Scholar]

- Amro, D.K.; Sukkar, A.; Yahia, M.W.; Abukeshek, M.K. Evaluating the cultural sustainability of the adaptive reuse of Al-Nabulsi traditional house into a cultural center in Irbid, Jordan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi, S.M.R.; Lak, A. Cultural landscapes in climate change: A framework for resilience in developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, L.; McArdle, K.; Fatoric, S. Minority community resilience and cultural heritage preservation: A case study of the Gullah Geechee community. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, L.D. Cultural heritage: A hybrid framework for ranking adaptive reuse strategies. Buildings 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W. The dynamic conservation and restoration of historical and cultural districts based on value and authenticity: Taking Xiaoxi Street in Huzhou as an example. China Anc. City 2023, 37, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.B. Returning to life-world: A study on the living authenticity of the historic blocks. Urban Plan. Forum 2008, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L. The social theoretical basis of lifestyle research—Re interpretation of Marx’s historical materialist social theory system. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2006, 9, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50357-2018; Standard of Conservation Planning for Historic City. Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Fedeico, L. Intangible cultural heritage: The living culture of peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 2011, 1, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. Authenticity & aura: A Benjaminian approach to tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; ICOMOS; ICCROM; IUCN. Guidance and Toolkit for Impact Assessments in a World Heritage Context; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.Q.; Xi, H.; Han, W.X. The construction, protection and development about space of historical towns with the changes of cultural ecology. Urban Dev. Stud. 2020, 27, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.F. Toward a smart sustainable development of port cities/Areas: The role of the “historic urban landscape” approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J. Traditional-modern transformation of cultural relics—From “bisection” to “quartering”. J. Northwest Min Zu Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2020, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.D.; Sheng, J. The in-depth analysis and correction path of China’ contemporary cultural consumerism. Stud. Ideol. Educ. 2022, 11, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.W.; Tan, Y.M.; Shen, Y.; Guan, M. Space-behavior interaction theory: Basic thinking of general construction. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar]

| Document | Source Text |

|---|---|

| The Venice Charter (1964) [22] | 6. The conservation of a monument implies preserving a setting which is not out of scale. Wherever the traditional setting exists, it must be kept. 11. The valid contributions of all periods to the building of a monument must be respected, since unity of style is not the aim of a restoration. 14. The sites of monuments must be the object of special care in order to safeguard their integrity and ensure that they are cleared and presented in a seemly manner. |

| The Nairobi Recommendation (1976) [23] | 3. Every historic area and its surroundings should be considered in their totality as a coherent whole whose balance and specific nature depend on the fusion of the parts of which it is composed and which include human activities as much as the buildings, the spatial organization and the surroundings. 4. Architects and town-planners should be careful to ensure that views from and to monuments and historic areas are not spoilt and that historic areas are integrated harmoniously into contemporary life. 31. Member States and groups concerned should protect historic areas and their surroundings against the increasingly serious environmental damage caused by certain technological developments… 33. Protection and restoration should be accompanied by revitalization activities… These functions should answer the social, cultural and economic needs of the inhabitants… |

| The Washington Charter (1987) [24] | Qualities to be preserved include the historic character of the town or urban area and all those material and spiritual elements that express this character, especially: (a) Urban patterns as defined by lots and streets; (b) Relationships between buildings and green and open spaces; (c) The formal appearance, interior and exterior, of buildings as defined by scale, size, style, construction, materials, colour and decoration; (d) The relationship between the town or urban area and its surrounding setting, both natural and man-made; and (e) The various functions that the town or urban area has acquired over time. Any threat to these qualities would compromise the authenticity of the historic town or urban area. |

| Operational Guidelines (2005) [25] | 88. Integrity is a measure of the wholeness and intactness of the natural and/or cultural heritage and its attributes. Examining the conditions of integrity, therefore requires assessing the extent to which the property: includes all elements necessary to express its Outstanding Universal Value; is of adequate size to ensure the complete representation of the features and processes which convey the property’s significance; suffers from adverse effects of development and/or neglect. |

| The Xi’an Declaration (2005) [26] | Principles and objectives: The setting of a heritage structure, site or area is defined as the immediate and extended environment that is part of, or contributes to, its significance and distinctive character. Beyond the physical and visual aspects, the setting includes interaction with the natural environment; past or present social or spiritual practices, customs, traditional knowledge, use or activities and other forms of intangible cultural heritage aspects that created and form the space as well as the current and dynamic cultural, social and economic context. Methods and instruments: The conservation plan should be supported by the residents of the historic area. |

| The Valletta Principles (2011) [28] | Definitions: … Historical or traditional areas form part of daily human life… Elements to be preserved: 1. The authenticity and integrity of historic towns, whose essential character is expressed by the nature and coherence of all their tangible and intangible elements, notably: (a) Urban patterns as defined by the street grid… (b) The form and appearance, interior and exterior of buildings… (c) The relationship between the town or urban area and its surrounding setting, both natural and manmade; (d) The various functions that the town or urban area has acquired over time; (e) Cultural traditions, traditional techniques, spirit of place and everything that contributes to the identity of a place. 2. The relationships between the site in its totality, its constituent parts, the context of the site, and the parts that make up this context. 3. Social fabric, cultural diversity. 4. Non-renewable resources, minimizing their consumption and encouraging their reuse and recycling. |

| Type | Content |

|---|---|

| Natural geographical | Natural geographical environment related to the site selection, construction, and site changes |

| Structural layout | Spatial structure and spatial order |

| Morphological scale | Style texture and spatial scale |

| Architectural heritage | Form and design, materials and texture, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, etc. |

| Environmental elements | Wells, walls, stone steps, pavements, riverbanks, etc. |

| Type | Content |

|---|---|

| Cultural expressions | (i) Traditional oral literature and its languages. (ii) Traditional visual arts, calligraphy, music, dance, drama, quyi, and acrobatics. (iii) Traditional craftsmanship, medicine, and calendars. (iv) Traditional etiquette, festivals, and other folk customs. (v) Traditional sports and games. (vi) Others |

| Related physical objects | (i) Tools, utensils, costumes, musical instruments, musical scores, etc., related to traditional visual arts, calligraphy, music, dance, drama, quyi, and acrobatics. (ii) Tools, utensils, and props related to traditional sports and games |

| Cultural spaces | (i) Spaces related to traditional cultural expressions. (ii) Venues that regularly host traditional cultural activities or centralized showcasing of traditional cultural expressions |

| Group | Element | |

|---|---|---|

| Formed by enfeoffment | Enduring historical culture | Legendary tale of urban origin and thousand-year history of county governance |

| Built according to the terrain | Harmonious landscape relationships | Built with deep moats and high plateaus, nestled against mountains, and encircled by water, with its city walls winding along the land’s contours |

| Blessed by Feng Shui | Located by the Hui River on an ox-shaped plateau; legend says a glance here creates scholars and a sip of its water yields beauties | |

| Marked by landmarks | Immovable cultural relics and architectural heritage | |

| Enriched by culture | Well-developed traditional education | Home to thriving academies, schools, and many temples |

| Prospered by commerce | Prosperous market trade | Bustling with merchants and thriving shops, with the north gate area once earning the title of “dry dock” in Yicheng county |

| Vitality with folk customs | Vibrant local life customs | Two national and one provincial intangible heritage, a folk worship event, and lively traditions |

| Type | Main Content | Characteristic | Change–Compatibility | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directly conservation | Immovable cultural relics, city gates, and archways | Relatively independent, well-preserved, and functional clarity | Weak–Low | Maintaining original states and enhancing surroundings |

| Integrated convergence | Architectural heritages | Good material base, strong flexibility, and certain public and openness nature | Moderate–Strong | Optimizing environmental elements and implementing a modern functional system |

| Natural geographical, intangible cultural heritage, city wall ruins, and alleys | ||||

| Differentiated adaptation | Public facilities, commercial facilities and service points, parking facilities, green spaces, leisure activity venues, a performance platform, outdoor fitness facilities, and a cultural library | Demolition and renovation, changing the current spatial layout | Significant–Moderate | Resource reallocation, spatial optimization, cultural linkage, and style coordination |

| New industries and facility relocation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Gao, W.; Yang, F. Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081304

Liu R, Gao W, Yang F. Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081304

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ruiqiang, Wanfei Gao, and Fan Yang. 2025. "Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081304

APA StyleLiu, R., Gao, W., & Yang, F. (2025). Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China. Buildings, 15(8), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081304