From Traditional Settlements to Arrival Cities: A Study on Contemporary Residential Patterns in Chinese Siheyuan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

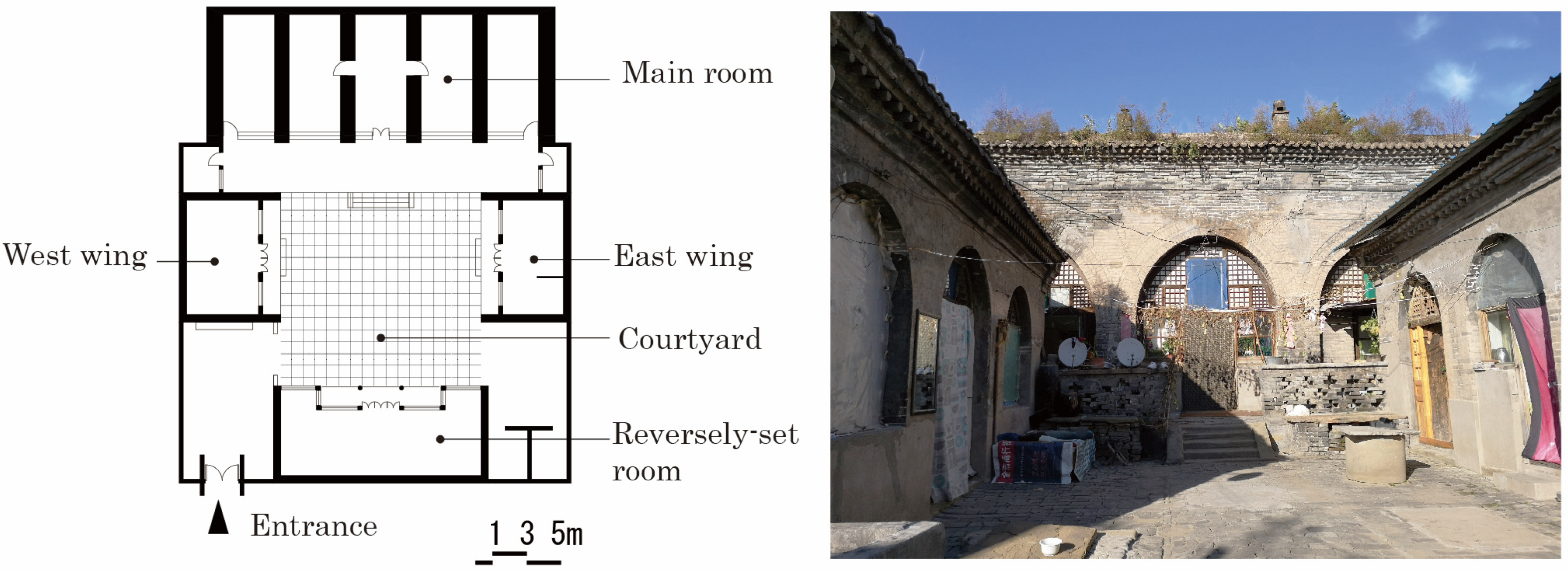

2.1. Current Spatial Usage of Siheyuan

2.2. Arrival Cities and the Informal Housing Market

2.3. Preservation and Gentrification of Historic Districts

2.4. Study Gap

3. Research Area and Methods

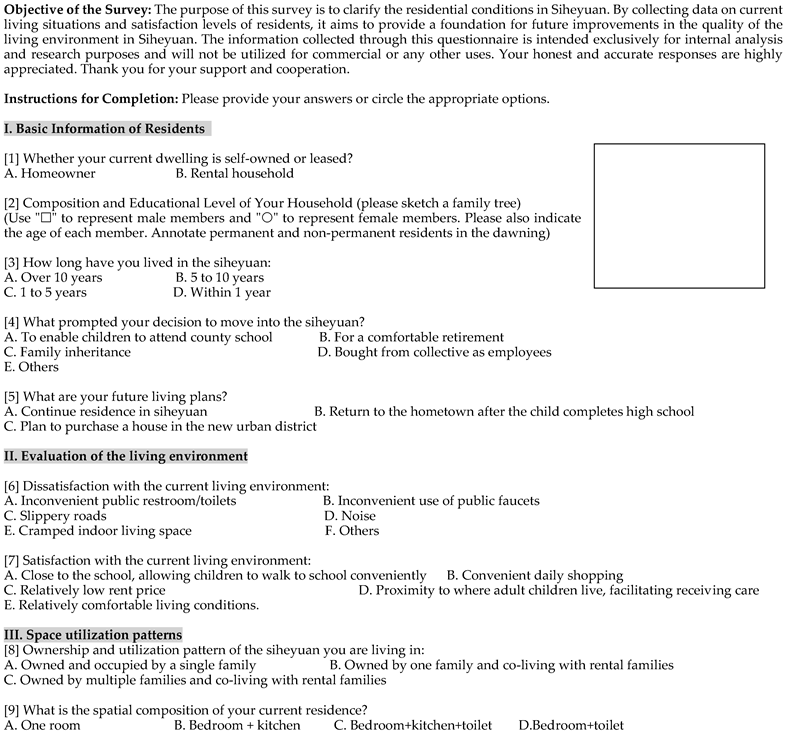

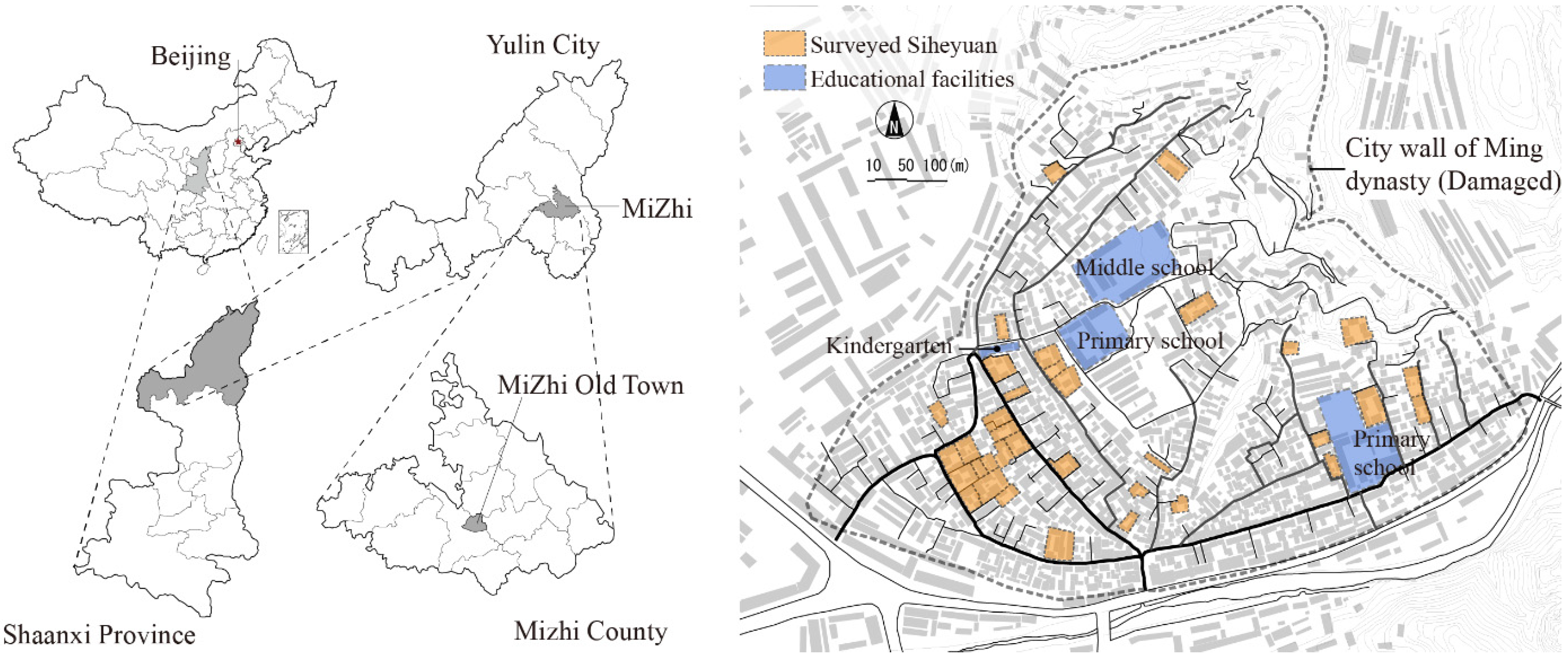

3.1. Research Area

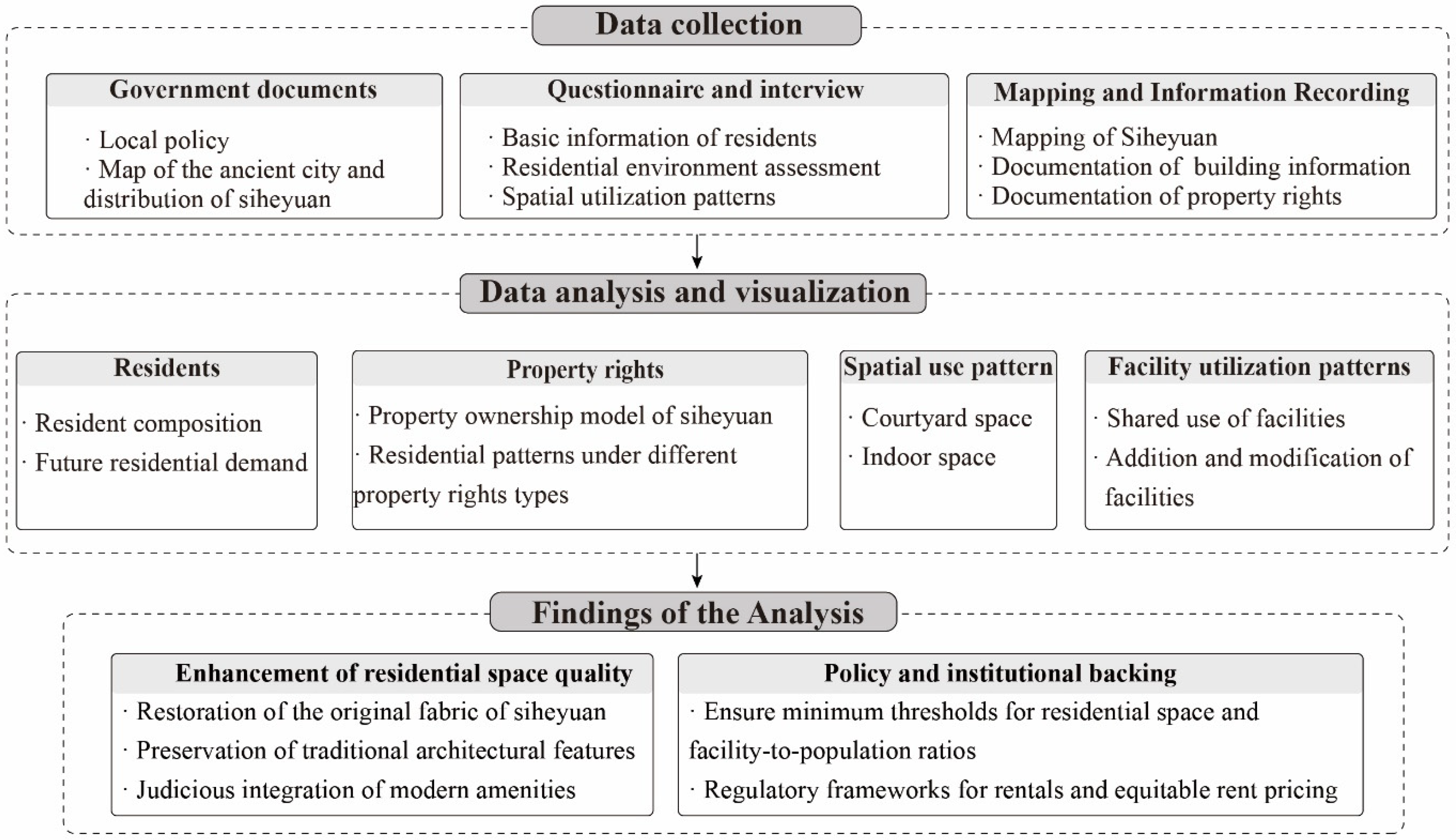

3.2. Research Method

4. Result

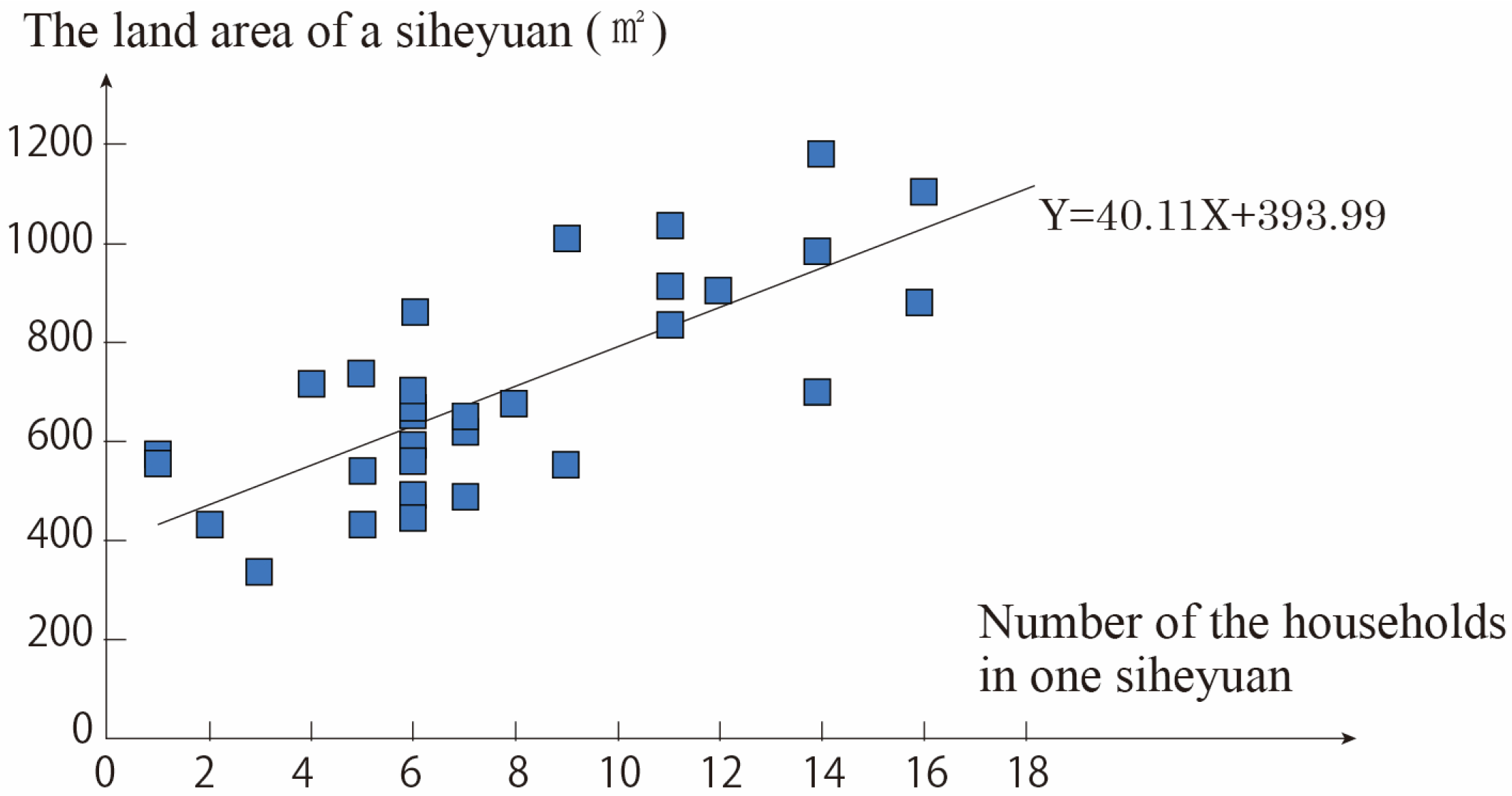

4.1. Overview of Siheyuan Residents

4.2. Ownership Model of Siheyuan

4.2.1. Current Property Ownership Situation

4.2.2. Division of Siheyuan and Alteration of Property Rights

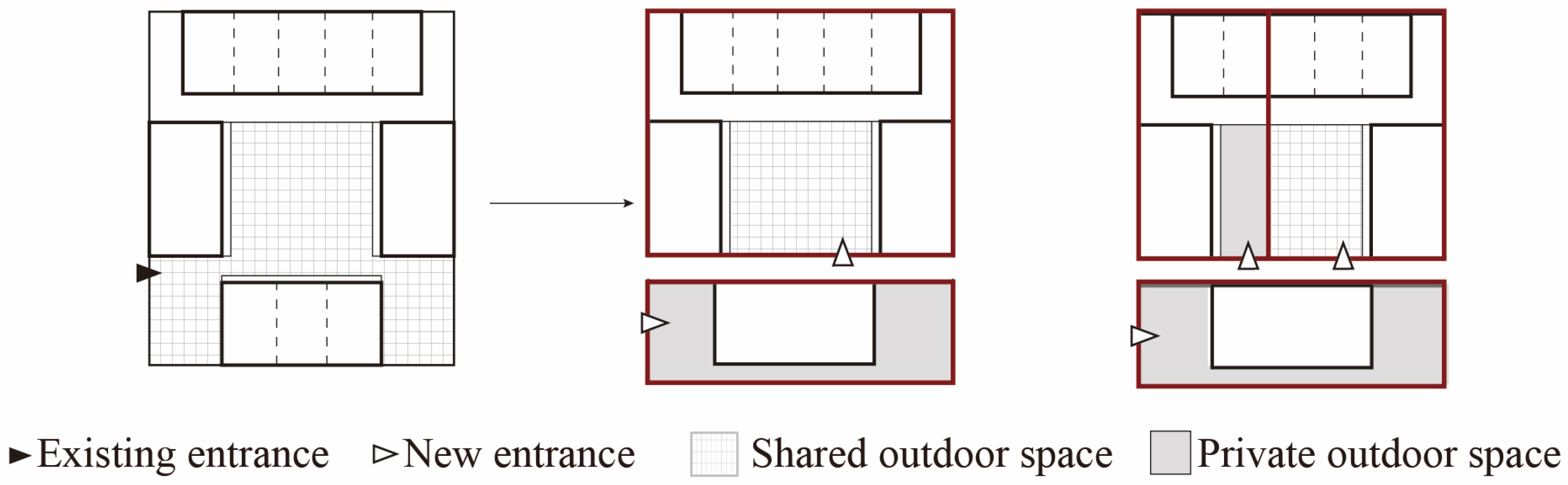

4.3. Space Utilization Patterns of Siheyuan

4.4. Utilization of Facilities and Renovations

4.4.1. Current Utilization of Facilities

4.4.2. Renovations of Siheyuan

4.5. Case Study

5. Discussion

5.1. Resident Profiles and Living Conditions

5.2. Renewal Strategies for Siheyuan

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

| Household population | 1 | 7 (17.95) | 10 (8.26) | 17 (10.63) | 19.357 | 0.001 ** |

| 2 | 17 (43.59) | 20 (16.53) | 37 (23.13) | |||

| 3 | 9 (23.08) | 43 (35.54) | 52 (32.50) | |||

| 4 | 5 (12.82) | 46 (38.02) | 51 (31.87) | |||

| 5 | 1 (2.56) | 2 (1.65) | 3 (1.88) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Age of parents | 20–29 | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.65) | 2 (1.25) | 43.374 | 0.000 ** |

| 30–39 | 2 (5.13) | 44 (36.36) | 46 (28.75) | |||

| 40–49 | 3 (7.69) | 33 (27.27) | 36 (22.50) | |||

| 50–59 | 9 (23.08) | 17 (14.05) | 26 (16.25) | |||

| 60–69 | 8 (20.51) | 7 (5.79) | 15 (9.38) | |||

| 70–79 | 8 (20.51) | 15 (12.40) | 23 (14.37) | |||

| 80–89 | 6 (15.38) | 3 (2.48) | 9 (5.63) | |||

| 90–99 | 3 (7.69) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (1.88) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

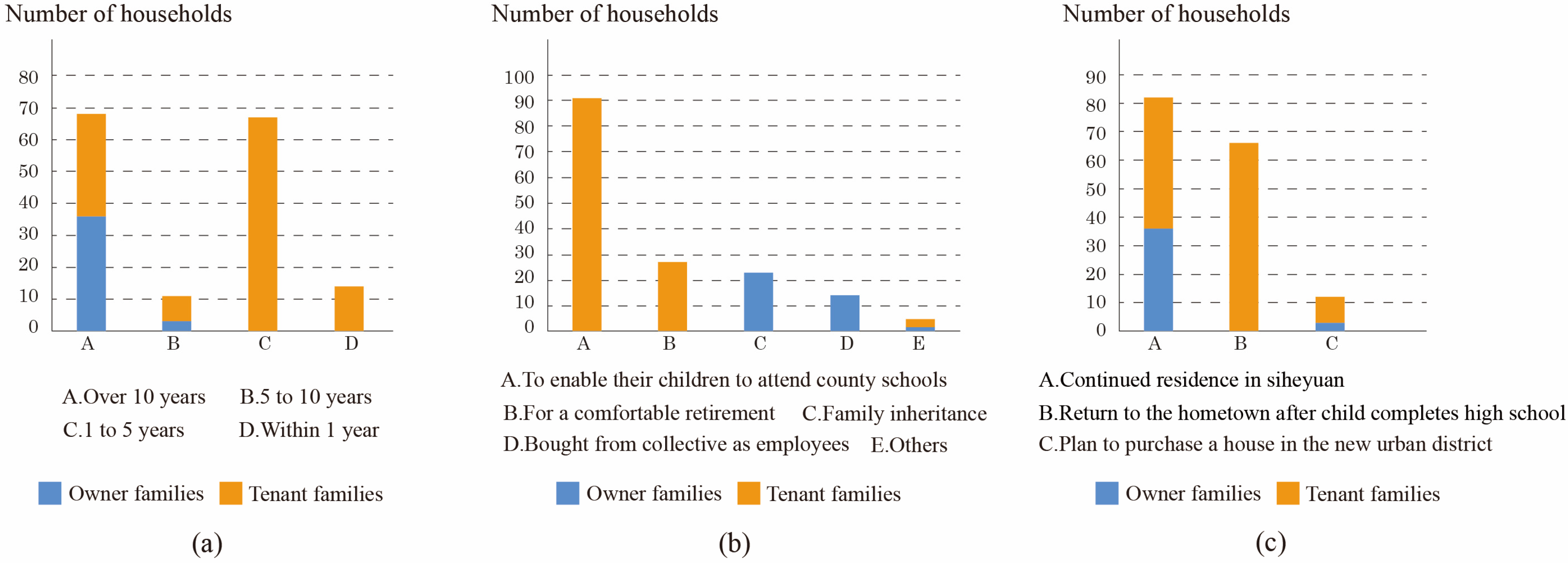

| Duration of residence | A | 36 (92.31) | 32 (26.45) | 68 (42.50) | 56.260 | 0.000 ** |

| B | 3 (7.69) | 8 (6.61) | 11 (6.88) | |||

| C | 0 (0.00) | 67 (55.37) | 67 (41.88) | |||

| D | 0 (0.00) | 14 (11.57) | 14 (8.75) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

| Settlement motivation | A | 0 (0.00) | 91 (75.21) | 91 (56.88) | 153.490 | 0.000 ** |

| B | 0 (0.00) | 27 (22.31) | 27 (16.88) | |||

| C | 23 (58.97) | 0 (0.00) | 23 (14.37) | |||

| D | 14 (35.90) | 0 (0.00) | 14 (8.75) | |||

| E | 2 (5.13) | 3 (2.48) | 5 (3.13) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

| Future housing plans | A | 36 (92.31) | 46 (38.02) | 82 (51.25) | 38.238 | 0.000 ** |

| B | 0 (0.00) | 66 (54.55) | 66 (41.25) | |||

| C | 3 (7.69) | 9 (7.44) | 12 (7.50) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

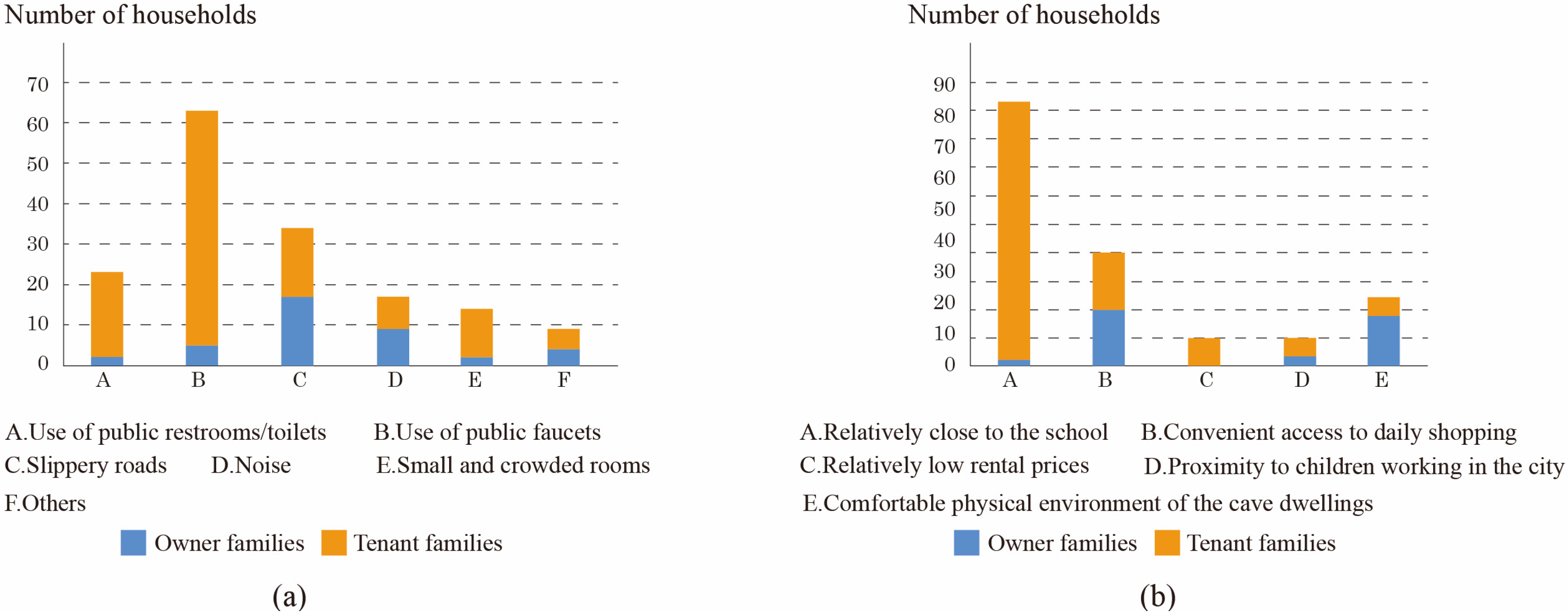

| Dissatisfaction | A | 2 (5.13) | 21 (17.36) | 23 (14.37) | 34.680 | 0.000 ** |

| B | 5 (12.82) | 58 (47.93) | 63 (39.38) | |||

| C | 17 (43.59) | 17 (14.05) | 34 (21.25) | |||

| D | 9 (23.08) | 8 (6.61) | 17 (10.63) | |||

| E | 2 (5.13) | 12 (9.92) | 14 (8.75) | |||

| F | 4 (10.26) | 5 (4.31) | 9 (5.63) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

| Satisfaction | A | 2 (5.13) | 82 (67.77) | 84 (52.50) | 66.063 | 0.000 ** |

| B | 18 (46.15) | 18 (14.88) | 36 (22.50) | |||

| C | 0 (0.00) | 9 (7.44) | 9 (5.63) | |||

| D | 3 (7.69) | 6 (4.96) | 9 (5.63) | |||

| E | 16 (41.03) | 6 (4.96) | 22 (13.75) | |||

| Total | 39 | 121 | 160 | |||

References

- Rong, W.; Bahauddin, A. Heritage and Rehabilitation Strategies for Confucian Courtyard Architecture: A Case Study in Liaocheng, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Diao, J.; Lu, S.; Tao, C.; Krauth, J. Exploring a Sustainable Approach to Vernacular Dwelling Spaces with a Multiple Evidence Base Method: A Case Study of the Bai People’s Courtyard Houses in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, G.; Li, A. Renovation and enhancement of Yuer Hutong courtyard: Design considerations based on the renovation of courtyards in the Nanluoguxiang area. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2021, 5, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. Courtyard in conflict: The transformation of Beijing’s Siheyuan during revolution and gentrification. J. Archit. 2017, 22, 1337–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, W.; Jia, K. Spatial experiment from traditional courtyard to modern courtyard: A discussion on the renovation design of historic buildings in historical districts from the perspective of stock-based urban renewal. China Eng. Consult. 2017, 05, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. The Architectural Typology Analysis of Han Traditional Courtyard in Northeast China. Int. J. Struct. Civ. Eng. Res. 2021, 10, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhai, H. Research on the micro society form of the courtyard-A case of No.5 courtyard in Fuxiang Hutong, Nanluogu Lane, Beijing. Urban. Archit. 2020, 17, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, C.; Fang, C. A theoretical framework and empirical study on the integrated conservation of traditional settlements from the perspective of society-space coconstruction. Urban Plan. Forum 2023, 4, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Fu, N.; Geertman, S.; van Oort, F. Towards inclusive and sustainable transformation in Shenzhen: Urban redevelopment, displacement patterns of migrants and policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chiou, S.; Li, W. Study on Courtyard Residence and Cultural Sustainability: Reading Chinese Traditional Siheyuan through Space Syntax. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, Q. Triple understanding of Guanzhong Narrow Courtyard and its house space. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Huang, X. Flowing sense of place: Perceptions of host city impacting on city attachment of rural-urban migrants in China. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2022, 88, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinh, N.; Kamalipour, H. The morphogenesis of villages-in-the-city: Mapping incremental urbanism in Hanoi city. Habitat Int. 2022, 130, 102706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Understanding the complexity of property rights in the protection of historic and cultural districts. Urban Plan. Forum 2018, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Siozinyte, E.; Antucheviciene, J.; Kutut, V. Upgrading the Old Vernacular Building to Contemporary Norms: Multiple Criteria Approach. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2014, 20, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H. “Old bottles and new galleries”: Renewal of Beijing’s old city courtyard from the perspective of human settlements. Huazhong Archit. 2022, 40, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Spatial landscape transformation of Beijing compounds under residents’ willingness. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, X.; Tan, Z. Miniature Beijing the renovation of No. 28 Dayuan Hutong. Archit. J. 2018, 7, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Design intuition from a perspective of spatial justice. Archit. J. 2020, 10, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D. Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History Is Reshaping Our World; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, H.F. Arrival cities and the mobility of concepts. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 3459–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Taubenböck, H.; Kraff, N.J.; Wurm, M. The morphology of the Arrival City—A global categorization based on literature surveys and remotely sensed data. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 92, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, T. ‘Jeppe’—Where Low-End Globalisation, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism and the Arrival City Meet. Urban Forum 2015, 26, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chen, M. Understanding the role of housing in rural migrants’ intention to settle in cities: Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Zhao, C.; Funo, S.; Kawai, M. Considerations on house types and their variants in the area of Zhonghuamen menxidiqu (Nanjing). J. Archit. Plan. (Trans. AIJ) 2016, 81, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, W.; Ye, C.; Liu, W. From the arrival cities to affordable cities in China: Seeing through the practices of rural migrants’ participation in Guangzhou’s urban village regeneration. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, H. As immigrant in metropolis: The analysis on housing condition of the floating population in Beijing and Shanghai. Soc. Stud. 2002, 17, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanie, L. The experience of precarity: Low-paid economic migrants’ housing in Manchester. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, L. Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Governing urban redevelopment: A case study of Yongqingfang in Guangzhou, China. Cities 2022, 120, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Shen, G.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. An optimization model for managing stakeholder conflicts in urban redevelopment projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, Y. From the replacement to the rebirth: The protection of the living authenticity of the residential historic blocks. Urban Dev. Stud. 2010, 17, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J. The protection and regeneration of historic and cultural districts from the perspective of micro-urban renewal: The urban design of Pingjiang historic and cultural district in Suzhou. Urban Plan. Forum 2017, 06, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, J. The public participation in the urban historical block’s renaissance: Beijing case. Planners 2013, 29, 197–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, C. Micro-regeneration of a historic and cultural district. Archit. J. 2017, 04, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhuang, Q.; Li, Z.; Dong, H. Exploration from compound courtyard to co-living courtyard in the old city of Beijing. Urban. Archit. 2021, 18, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, P.; Gu, Z. Based on the historical and cultural blocks from the perspective of public protection and remediation: Historical and cultural city of Zhengding as an example. Urban Dev. Stud. 2014, 21, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester, J.; Hartmann, T. Unraveling the self-made city: The spatial impact of informal real estate markets in informal settlements. Cities 2021, 108, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostrum, M. Access, density and mix of informal settlement: Comparing urban villages in China and India. Cities 2021, 117, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; González Martínez, P. Heritage, values and gentrification: The redevelopment of historic areas in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 28, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Recreational Business District boundary identifying and spatial structure influence in historic area development: A case study of Qianmen area, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Wang, F.; Xiang, S.; Lin, B.; Gao, C.; Li, J. Inheritance or variation? Spatial regeneration and acculturation via implantation of cultural and creative industries in Beijing’s traditional compounds. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, W. Life Satisfaction of Rural-To-Urban Migrants: Exploring the Influence of Socio-Demographic and Urbanisation Features in China. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The County Annal Compilation Committee of Mizhi Prefecture. Annals of Mizhi County; Shannxi People’s Publishing House: Xi’an, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission. Issuing the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Being. Available online: https://www.pkulaw.com/en_law/d94e9e56ed4fc8fcbdfb.html?keyword=%E6%B6%89%E5%8F%8A%E4%BA%BA%E7%9A%84%E7%94%9F%E5%91%BD%E7%A7%91%E5%AD%A6%E5%92%8C%E5%8C%BB%E5%AD%A6%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%E4%BC%A6%E7%90%86%E5%AE%A1%E6%9F%A5%E5%8A%9E%E6%B3%95 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Pan, Y.; Cobbinah, P.B. Embedding place attachment: Residents’ lived experiences of urban regeneration in Zhuanghe, China. Habitat Int. 2023, 135, 102796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegn, H.; Kawai, M.; Jimenez, J.; Funo, S.; Hirota, N. Considerations on improvement of living environment of Peng-hu-qu in Xuanxibei District (Outer castle of Beijing). J. Archit. Plan. (Trans. AIJ) 2020, 85, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. State Council Policy Interpretation on Healthcare Reform. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-01/12/content_10582.htm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Nasreen, Z.; Ruming, K.J. Informality, the marginalised and regulatory inadequacies: A case study of tenants’ experiences of shared room housing in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2020, 21, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S. A housing sociology study on the housing patterns of the floating population in Beijing. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 23, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. Destigmatizing urban villages by examining their attractiveness: Quantification evidence from Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. Proposals of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Formulating the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Term Goals for 2035. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-11/03/content_5556991.htm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yuan, Q. The redevelopment of peri-urban villages in the context of path-dependent land institution change and its impact on Chinese inclusive urbanization: The case of Nanhai, China. Cities 2017, 60, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, S.; Li, J. The dawn of vulnerable groups: The inclusive reconstruction mode and strategies for urban villages in China. Habitat Int. 2021, 110, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y. Beyond neoliberal urbanism: Assembling fluid gentrification through informal housing upgrading programs in Shenzhen, China. Cities 2021, 112, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, S. How housing rent affect migrants’ consumption and social integration?—Evidence from China Migrants Dynamic Survey. China Econ. Q. Int. 2022, 2, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xie, J.; Tian, C. Housing wealth change and disparity of indigenous villagers during urban village redevelopment: A comparative analysis of two resettled residential neighborhoods in Wuhan. Habitat Int. 2020, 99, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstenbach, C.; Musterd, S. A regional geography of gentrification, displacement, and the suburbanisation of poverty: Towards an extended research agenda. Area 2021, 53, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Urban conservation and revalorization of dilapidated historic quarters: The case of Nanluoguxiang in Beijing. Cities 2010, 27, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Maalsen, S.; Shrestha, P. Is ‘informal’ housing an affordability solution for expensive cities? Evidence from Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2020, 22, 10–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ho, P. Formalizing informal homes, a bad idea: The credibility thesis applied to China’s “extra-legal” housing. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family Type (%) | Total (%) | X2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Tenant | |||||

| Housing patterns | One-room | 8 (14.04) | 169 (92.35) | 177 (73.75) | 143.669 | 0.000 ** |

| Bedroom + kitchen | 20 (35.09) | 11 (6.01) | 31 (12.92) | |||

| Bedroom + kitchen + bathroom | 28 (49.12) | 3 (1.64) | 31 (12.92) | |||

| Bedroom + bathroom | 1 (1.75) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.42) | |||

| Total | 57 | 183 | 240 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Xu, X.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, D. From Traditional Settlements to Arrival Cities: A Study on Contemporary Residential Patterns in Chinese Siheyuan. Buildings 2025, 15, 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081216

Wang M, Xu X, Qi Y, Zhang D. From Traditional Settlements to Arrival Cities: A Study on Contemporary Residential Patterns in Chinese Siheyuan. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081216

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Mengying, Xin Xu, Yingtao Qi, and Dingqing Zhang. 2025. "From Traditional Settlements to Arrival Cities: A Study on Contemporary Residential Patterns in Chinese Siheyuan" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081216

APA StyleWang, M., Xu, X., Qi, Y., & Zhang, D. (2025). From Traditional Settlements to Arrival Cities: A Study on Contemporary Residential Patterns in Chinese Siheyuan. Buildings, 15(8), 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081216