1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Aim

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese government has continuously implemented rural development policies, laying the foundation for long-term rural revitalization. A notable shift emerged since 2010, as increasing numbers of individuals began returning to rural living, driven by improved infrastructure, policy incentives, and changing socioeconomic dynamics. This trend gained further momentum in 2018 with the introduction of national-level rural revitalization, which actively encouraged urban-to-rural migration. These policies have significantly improved living conditions, expanded rural economic opportunities through industrial diversification and investment, and provided targeted incentives such as financial subsidies and land-use reforms. As a result, rural return has evolved beyond an idyllic lifestyle preference into a strategic mechanism aligned with the government’s broader objectives for rural rejuvenation and space transformation.

This study aims to explore the impact of rural return on the evolution of rural spaces at the village level in China, with a particular focus on how urban-to-rural migration reshapes village spatial structures. The primary objective is to reveal the crucial role of migrants’ relocation needs in spatial adaptation, while also examining how their active participation in public life and community spaces serves as a key driver of spatial regeneration. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the critical role of rural return in the functional transformation of traditional dwellings and the spatial regeneration of existing villages. Through this research, the paper provides a novel perspective on understanding contemporary rural transformation in China, demonstrating that urban-to-rural migration not only reshapes village spatial configurations but also fosters social and functional revitalization, thereby offering valuable insights for future rural development strategies. Additionally, the study explores the post-settlement realities of these migrants, focusing on their use of village public spaces. In this context, the study critically examines the role of rural return in driving the transformation of rural spaces.

1.2. Literature Review

Interpreting rural return in China necessitates an in-depth understanding of the country’s long-standing and complex rural development and revitalization processes. Over the past 70 years since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, rural infrastructure construction and economic development have progressed steadily from an almost non-existent foundation, leading to substantial improvements [

1]. Throughout this extended trajectory, China’s rural areas have undergone multiple phases of transformation [

2]. Existing research has systematically reviewed the historical evolution of rural development in China since 1949, categorizing it into four distinct stages: the dual urban–rural structure under the People’s Commune system, the household responsibility system dominated by smallholder farming, the urban–rural coordinated development phase driven by urban support for rural areas, and the current phase of urban–rural integration and rural revitalization [

3]. The ongoing rural revitalization strategy represents a critical juncture in China’s rural development, aimed at addressing persistent challenges and facilitating a transition toward a more advanced developmental stage [

4]. The continuous reform and optimization of policies have been fundamental drivers of rural development in China, particularly following the transformative shifts initiated by the 1978 Reform and Opening-Up policy [

5,

6]. As rural development transitioned toward an urban–rural integration model, population mobility patterns began shifting, fostering increasing flows from cities back to rural areas. The interplay of population, land, industry, and rights has emerged as a crucial factor in restructuring urban–rural relations [

7]. Government-led planning and policy interventions have facilitated the redistribution of key resources—such as talent, land, and capital—toward agriculture and rural areas, thereby accelerating the trend of urban-to-rural migration [

8].

The phenomenon of rural return was first observed in the 1960s during the second wave of counter-urbanization in Europe and the United States [

9,

10]. Geographers and demographers have conceptualized this phenomenon using various terminologies, such as the turnaround of population flows and urban-to-rural migration [

11]. Existing studies have examined rural return from multiple perspectives. Some research has analyzed it within the broader trajectory of economic development trends [

12], while others have investigated its driving factors and long-term developmental patterns [

13]. Additionally, a substantial body of literature has explored the diverse forms of rural return [

14], as well as the value orientations and migration motivations of rural migrants, particularly among younger generations [

15,

16,

17].

Due to variations in social development models and stages across different regions of the world, the specific manifestations of rural return also differ. In Japanese studies, research on rural return has predominantly focused on population mobility and social governance, with some attention given to spatial perspectives, such as spatial awareness, landscape conservation, and spatial utilization [

18,

19,

20]. Regarding spatial studies of rural returns, research from the UK and the US has explored how in-migrants have driven changes in rural spaces, contributing to the emergence of “third spaces”—public spaces such as cafés, bookstores, and parks that are independent of the home (first space) and the workplace (second space) [

21]. These third spaces have fostered greater social interaction and participation within local communities [

22,

23]. Furthermore, some studies have highlighted how these spatial transformations reflect the interaction dynamics between local residents and in-migrants [

24,

25].

In the context of rural China, most research has concentrated on the return of rural migrant workers—individuals originally from rural areas who migrate to urban centers for employment—rather than on residents with urban household registrations [

26]. While some scholars have explored the activities of urban-to-rural migrants, their analyses predominantly emphasized policy and economic factors [

27,

28]. Additionally, some scholars have investigated the reasons and motivations behind rural return in China [

29]. Others have examined the role of returning talent, particularly young people, in rural development and governance [

30,

31,

32]. In terms of rural spatial restructuring, certain studies have focused on the impact of rural return on spatial dynamics and indigenous populations [

33,

34,

35]. However, the existing literature has yet to adequately address the role of rural return in transforming rural living spaces.

Based on the above background, this study aims to investigate the patterns of rural return within the context of China’s governance systems, with a particular focus on the spatial changes induced by urban-to-rural migration and their effects on rural spatial structures. The research explores how migrants integrate into rural communities and adapt traditional village spaces to accommodate new social and economic activities. Through a detailed analysis of three case studies in Zhejiang Province, the study examines the transformation of village spatial configurations, highlighting the role of migrants in reshaping both the physical and social fabric of rural spaces. The findings provide valuable insights into the evolving dynamics of rural settlements and offer recommendations for future rural development strategies.

2. Methods and Research Composition

This study selected villages in China’s Zhejiang Province, as research sites due to the province’s leadership in rural development, its notable population of returnees, and the transformative impact of sustained return migration on its rural areas. On-site surveys were conducted in two phases: from May to June 2019 and from November to December 2023. The first survey was broad in scope, collecting substantial foundational data on village studies [

36], while the second survey was more focused, conducting a detailed examination of the returnee migrant population and their residential housing.

The data were collected through structured interviews with both village officials and returnee migrants. The sampling approach involved selecting a diverse range of participants, ensuring representation from various age groups, gender, and migration experiences. Village officials were chosen for their roles in local governance and their knowledge of the policies and initiatives related to rural return. Returnee migrants were selected based on factors such as time since return, reasons for migration, and current living conditions. This combination of perspectives from both local authorities and returnees allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the rural return process and the socio-economic challenges faced by migrants upon their return. Additionally, the architectural layout and spatial characteristics of the villages were measured and documented, facilitating an analysis of how architecture introduced by migrants integrates with and impacts the existing village environment. The measurements specifically included the topographical characteristics of the village, the spatial layout of all buildings within the village, including those inhabited by migrants, as well as the footprint and dimensions of these structures. Qualitative analysis will be employed to analyze the information gathered from interviews, identifying key themes and patterns to understand the needs, challenges, and impacts of immigrants on the community. For the measurement data, spatial analysis will be conducted to visualize the location and spatial layout of buildings, examining how immigrant-introduced architecture integrates into the existing village environment and its influence on the spatial structure.

This study focuses on the migrant population who originally lived and worked in urban areas with urban household registration and relocated to villages for residence or work due to various purposes and forms. This group includes university graduates employed in rural areas, retirees, and entrepreneurs, among others. The demographic data of migrants in this study were primarily obtained through on-site statistical surveys and further verified through communication with village committees and field investigations.

Based on the aforementioned framework, this study is structured into four main components (

Figure 1) to explore the spatial dynamics of rural return in Zhejiang Province.

Section 3.1 provides an overview of the return migration phenomenon in Zhejiang, offering contextual insights into broader trends in rural migration.

Section 3.2 analyzes the spatial structure and migration patterns in three representative villages.

Section 3.3 examines the housing and workspaces selected by urban-to-rural migrants, focusing on the resulting spatial transformations and changes to village layouts resulting from these settlements.

Section 3.4 explores the use of public spaces by post-migration residents, analyzing the social integration of migrants and their interactions with established communities. By analyzing these distinct contexts and real dynamics, the study aims to offer a nuanced understanding of how rural return dynamics influence spatial and socio-economic transformations across Zhejiang Province.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Overview of Rural Development and Rural Return in Zhejiang Province

Zhejiang Province, located in the southeastern coastal region of China, is one of the country’s most economically advanced areas. Along with its capital, Hangzhou, and the cities of Shanghai and Nanjing, Zhejiang forms part of the Yangtze River Delta Economic Region [

37], a pivotal hub for China’s economic growth. Despite its high degree of urbanization, approximately 40% of Zhejiang’s population—around 65 million people—still resides in rural areas, which are distributed across nearly 50,000 natural villages. These villages are densely concentrated, particularly in plains and coastal regions, and typically have small populations, averaging around 500 residents per village [

38]. Between 2012 and 2023, a total of 728 villages in Zhejiang were selected in six batches to be included in the list of traditional villages in China [

39] (

Figure 2). These villages are recognized for their significant cultural and historical value, and due to their superior natural and cultural environments, have become important destinations for urban populations migrating to rural areas.

This study selects three representative villages—Shishe, Chenjiapu, and Kenggen—located in the northern, central, and southern regions of Zhejiang Province, respectively (

Figure 3). The selected villages must exhibit a distinct and sustained phenomenon of rural return, ensuring that the spatial transformations within the villages are both pronounced and diverse due to an adequate sample size and extended observation period. Traditional villages, with their cultural heritage, landscape features, and architectural character, hold strong appeal for urban residents, making them ideal subjects for studying rural return. The three traditional villages examined in this study were carefully chosen as representative cases from this broader category. Among these, Shishe Village was included in the first batch of traditional villages, while Chenjiapu and Kangen Village were added in the third batch. These geographically and culturally diverse cases provide valuable insights into rural return migration and its implications for spatial development.

According to the per capita disposable income statistics from the China Rural Statistical Yearbook (

Figure 4), Zhejiang Province stands out as one of the regions with the smallest urban–rural income gap in China, with relatively advanced rural infrastructure that facilitates rural migration. Following the 2005 policy shift towards the synergistic development of the economy and the environment [

40] in Zhejiang, the province has made continuous strides in rural development. Many of its villages have now become models for rural revitalization in China, attracting a significant number of urban residents to return to rural areas.

The evolution of villages in Zhejiang primarily follows two trajectories: the internal renewal of old villages and the construction of new villages [

41]. New village construction generally targets original rural inhabitants, whereas urban migrants typically prefer to settle in traditional villages to immerse themselves in the rural cultural environment. As a result, the three case studies selected for this research are categorized under the internal renewal of old villages.

In these villages, the Village Committee, as a grassroots self-governing organization, primarily undertakes responsibilities related to managing the village environment, supporting indigenous residents, and implementing top-down policy directives. However, the task of attracting urban residents back to rural areas to stimulate village development falls under the jurisdiction of township- and county-level government agencies responsible for rural development. The county and township governments play a pivotal role in return policy formulation and implementation, as well as urban talent attraction and coordination, ensuring that the process of urban-to-rural migration is supported by a robust institutional framework and a seamless residential transition for returning urbanites.

3.2. Spatial Characteristics of Villages and Migration Patterns

To understand the context and spatial dynamics of rural return in the selected villages, this section focuses on two key aspects: the spatial characteristics prior to migration and the types of migration. The analysis is based on the villages’ basic data, development records, and migration patterns to perform a typological classification.

3.2.1. Spatial Characteristics of Villages

Figure 5 summarizes key data on the population, geography, settlement patterns, and tourism of the three villages. The villages have populations ranging from 500 to 1000 people, areas of 30 to 60 square kilometers, and are located within 15 km of their respective county towns. These characteristics offer favorable conditions for settlement and rural return. The investigation revealed that the migrant populations in Shishe, Kenggen, and Chenjiapu were 16, 19, and 17 individuals, respectively, accounting for a migration ratio of 0.15 to 0.3 relative to the original inhabitants. Since rural return continues to unfold within the broader context of China’s late-stage urbanization, cases of U-turn migration—where individuals or their descendants return to their ancestral villages after obtaining urban household registration—are rare. In contrast, the migrants in the sample have no kinship ties to the villages they settle in. The observed migration pattern predominantly follows an I-turn model, characterized by a one-way flow from urban areas to villages. Several factors contribute to the attractiveness of these villages for urban residents, including convenient transportation, picturesque natural landscapes, and a balanced distribution of resources the supply of resources such as education, healthcare, transportation, and consumer goods. In addition to agriculture, tourism has emerged as a significant source of income, with a steady influx of visitors stimulating local economic development and providing migrants with stable income-generating opportunities.

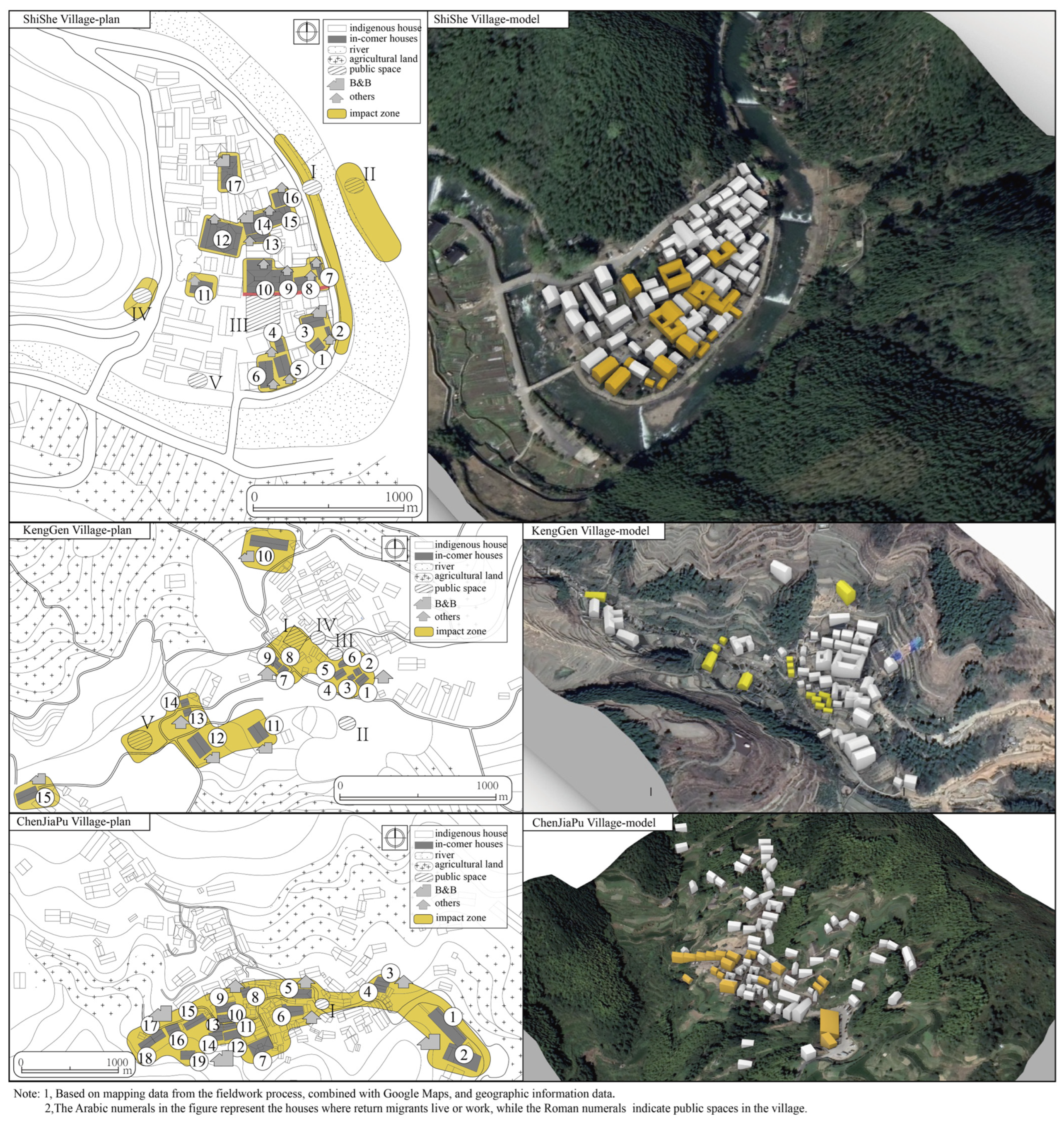

The spatial layout of each village is shaped by the local topography and landscape. Shishe Village follows a circular road system, with buildings arranged around the interior of the main roads. Kenggen Village employs a radial road pattern, while Chenjiapu Village’s buildings are arranged along several major branch roads. The distinct layout of each village not only defines its spatial organization and structural form but also influences the settlement choices of the migrants.

The residential choices of migrants have led to changes in the living environment of the villages. The existing buildings in all three villages feature a mix of renovated structures tailored to the migrants’ specific needs alongside traditional buildings. Migrants, primarily young people and the elderly, relocate to find work or start businesses, with a smaller number moving for a change in their living environment. Their dwellings are scattered throughout the village, and their activities influence the entire neighborhood, contributing to changes in the village’s spatial arrangement.

3.2.2. Mode and Types of Rural Return

In this study, interviews were conducted with migrants regarding their reasons for migration, previous place of residence, and duration of stay in the village. The findings from these interviews are typologically summarized in the figure below. The results indicate that the migrants in the three villages can be classified into four primary categories based on their migration purposes: pursuing a rural lifestyle, retiring to the countryside, seeking employment in rural areas, and starting their own businesses.

These migrants hold urban household registrations and do not change their residency status when relocating to rural areas. In China, household registration is closely tied to education, healthcare, and social security, ensuring that individuals with urban status can enjoy rural natural landscapes while maintaining access to urban resources. This prevents them from losing high-quality public services upon moving to the countryside. Another key distinction between rural and urban household registrations lies in land ownership. On the one hand, China enforces strict regulations on land transfer; on the other hand, continuous land reforms in recent years have facilitated transactions of land use rights. Against this backdrop, migrants participating in rural return movements in China generally opt to retain their urban household registration.

Regarding their prior place of residence, it is evident that not all urban migrants originated from neighboring cities; Many came from other provinces. Moreover, for many individuals, migrating to the countryside does not entail a complete disconnection from urban life. Several migrants maintain dual residency, spending time in both the city and the village, often residing in the village only during certain seasons or holidays. However, some residents have completely transitioned away from urban living and opted to live permanently in the countryside.

While the migrants primarily come from urban areas, the original inhabitants of the village, tourists, and some relationship population [

42], also play integral roles in the migration process. The interactions and roles of these various groups contribute to the formation of the new village community, illustrating the complex dynamics of rural return migration.

Figure 6 summarizes the migration types observed in the three villages, based on data collected through interviews with migrants. The classification integrates information about each migrant’s purpose, place of origin, and duration of stay in the village. The analysis identifies a total of ten distinct migration types (presented on the far right of

Figure 6), with an uneven distribution across categories. The most prevalent group consists of migrants who work in the villages and reside there only during their work cycles. Overall, the data reveal that migrants with dual residency—splitting time between urban and rural locations—outnumber those who have long-term settled in the villages. Furthermore, the findings reveal a significant number of migrants who relocate to the villages to start businesses or seek employment, reflecting the influence of policy-driven initiatives aimed at supporting rural economic revitalization and encouraging urban-to-rural migration.

3.3. Characteristics of Rural Spatial Structure Following Rural Return

In this section, the specific impacts of urban-to-rural migration on village spaces are examined by analyzing the spatial structure of the villages through three key elements: streets, houses, and spatial nodes. The houses occupied by migrants are numbered to distinguish the spatial distribution of original residents and migrants.

Figure 7, created from on-site measurements, illustrates this spatial information through both a general plan and a three-dimensional model, showcasing the reconfigured village space following rural return.

3.3.1. Features of the Migrants’ Settlements in the Villages

When observing the spatial transformation of villages under rural return, space should not be regarded merely as a static container, but as a dynamic area of continuous production and transformation. In this context, the spatial effects of rural migration directly reflect the multiple and complex processes occurring within village practices. Based on field surveys and interviews conducted in the villages,

Figure 8 documents the construction methods of the spaces utilized by migrants, their functional composition, the architectural structures, and the forms of spatial organization, providing an analysis of the characteristics of village spatial reconfigured after migration.

The table reveals that the identity characteristics of migrants vary according to the functional use of the houses they occupy. In some mixed-use commercial and residential properties, both the property owners and their employees reside, whereas others are inhabited by individuals with a single role. For instance, in Shishe Village, the occupants of houses (1, 2, 3), (4, 5), and 16 are (A, A1), (B, B1), and (L, L1), respectively, while house 6 is solely occupied by the property owner. Due to the preservation requirements of traditional villages, migrants primarily choose to renovate and make small-scale updates to existing buildings, striving to maintain the historical and cultural value of these traditional villages. Only a small number of newly constructed buildings are scattered within the villages, and these are also required to align with the architectural and aesthetic characteristics of traditional villages.

Furthermore, the impact of return migrants on village spaces is evident in the proliferation of third places, including cafés, restaurants, bars, and cultural and creative shops—public spaces that facilitate gathering, leisure, and social interaction. These spaces have become the social hubs of rural communities and serve as key attractions for visitors. Combined with the pastoral rural landscape, they offer a distinct third-place experience that differs from urban settings. More importantly, these spaces provide the foundation for the regeneration of rural society by serving as nodes for the flow and exchange of urban and rural resources. They create inclusive environments where individuals from diverse backgrounds and lifestyles can coexist, thereby fostering new patterns of modern public interaction within the rural social fabric.

3.3.2. The Evolution of Village Space in the Context of Rural Return

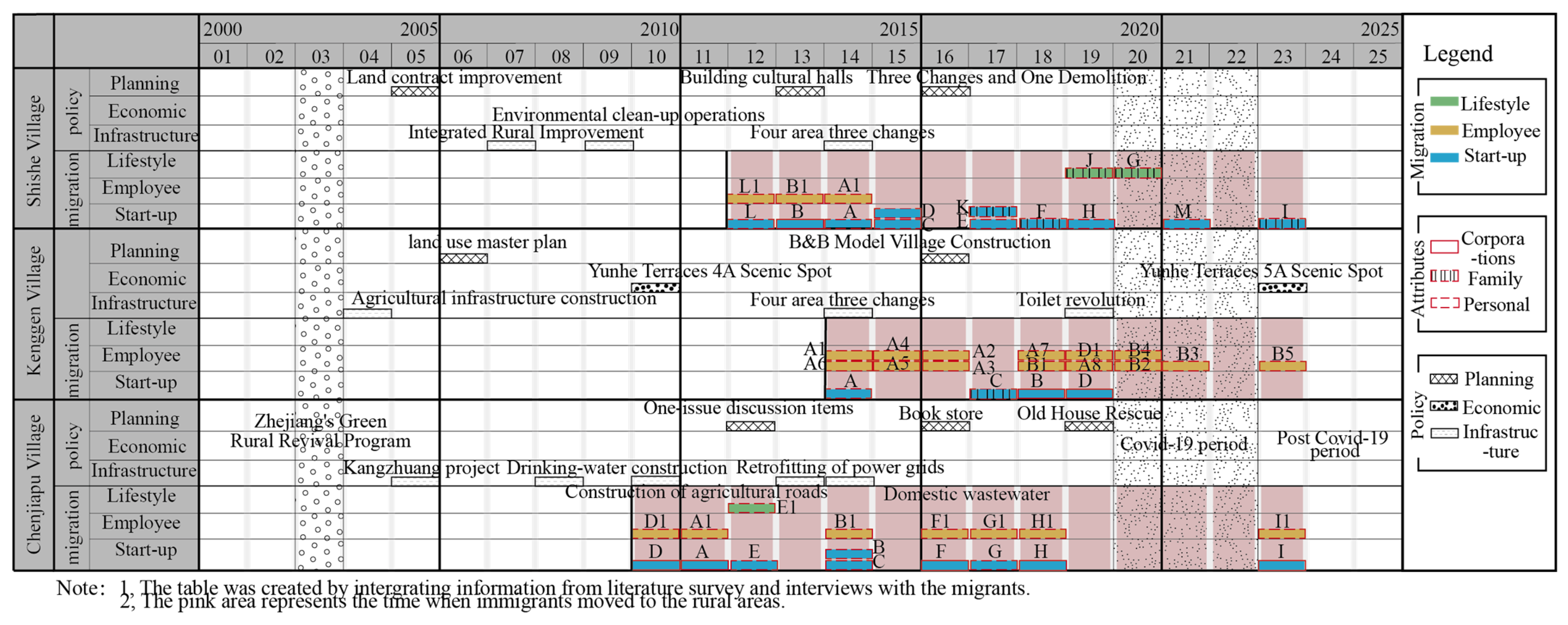

Rural return has become a long-term factor influencing the reconstruction of village space, contributing to the evolution of rural spatial dynamics alongside other factors.

Figure 9 outlines the key policies and migration events in the three villages over the years. The role of policies in village evolution includes overall planning, economic development, and infrastructure construction. As shown in the figure, there is a temporal gap between the implementation of policies and the occurrence of migration, indicating that rural areas require time to create an environment that meets the needs of urban migrants. This is particularly evident in infrastructure development, reflected in the continuous improvement of public facilities ensuring modern living standards, such as activity squares, landscape enhancement, sanitation management, and the supply of water, electricity, and internet.

Individuals, families, and businesses have all entered the villages through various channels to initiate new ventures, creating employment opportunities and attracting more people to the villages. In Shishe and Chenjiapu villages, migrants typically rent a single house in the village, while Kenggen Village has developed a more complex system. In Kenggen, migrants rent multiple houses within the village, each serving a distinct function, with a separate employee assigned to manage each one. Although many migrants establish business in the village, their decision to migrate is often based on multiple purposes. Those seeking employment in rural areas often share a common motivation: the pursuit of an idyllic rural lifestyle.

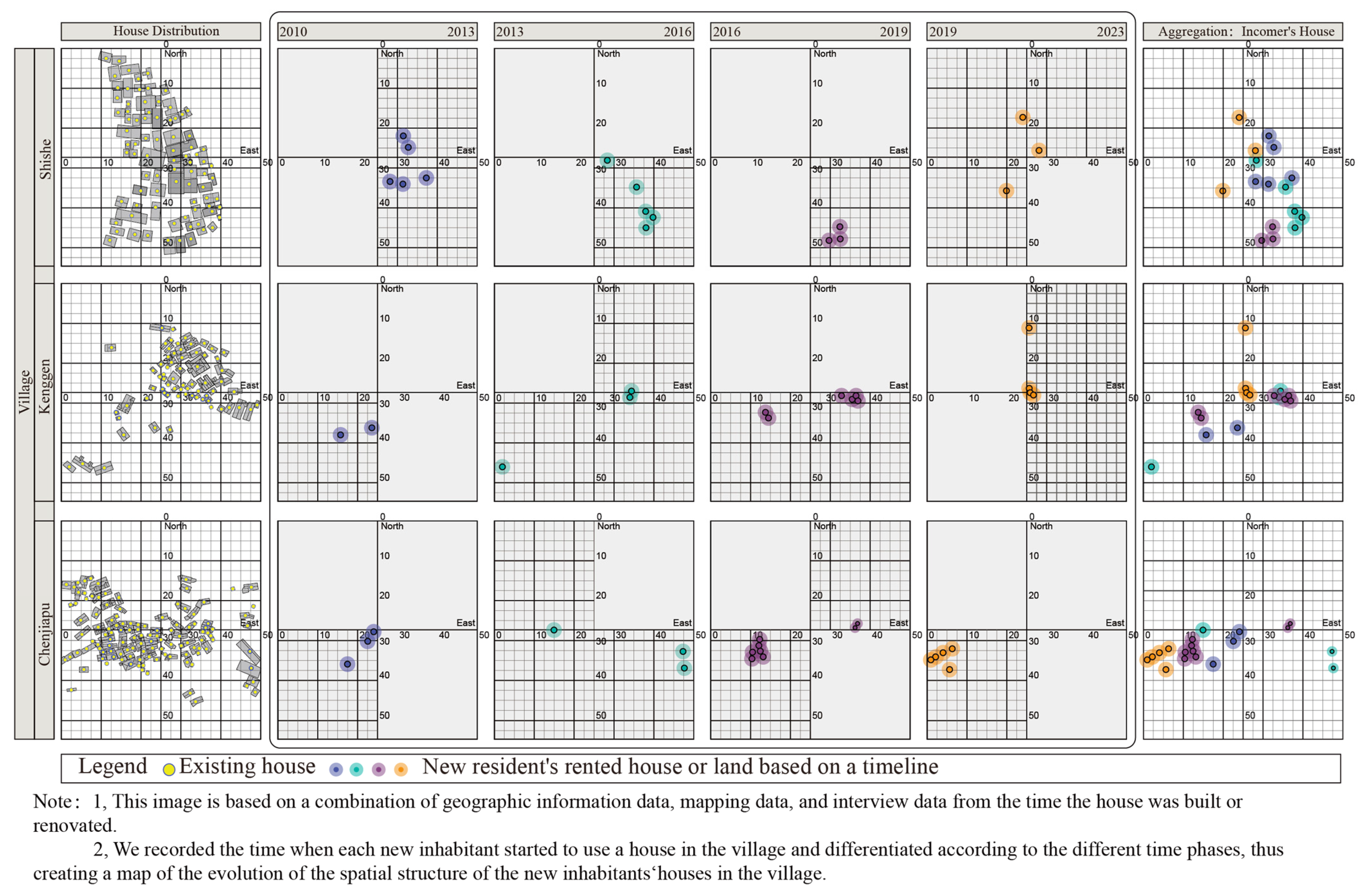

Rural return in the village is a gradual process, with new residents progressively occupying more areas of the village over time. Initially, they settle in one or two houses, but as the migration process continues, they expand to occupy dozens of houses, becoming a significant architectural presence within the village. Prior to migrating to the village, most individuals rent old houses or homesteads within the village. Based on interviews with them, we have gathered data on the specific timings of house reconstruction or new construction, which was used to create a spatial evolution diagram.

Figure 10 illustrates the changes in village space over time under the influence of the rural return wave. The process radiates outward from the core of the village, gradually creating a situation where the spaces occupied by both local inhabitants and migrants are integrated. As migration progresses, new types of spatial functions emerge, better aligned with contemporary needs.

The impact of incoming migrants on rural spaces is not always beneficial. The negative effects primarily manifest in two aspects: the excessive commercialization that disrupts the traditional rural landscape and the encroachment of migrants on the living spaces of original villagers. Although protective development regulations exist for traditional villages, modifications to historic buildings to accommodate commercial activities often compromise the architectural heritage and cultural identity of the village. Moreover, due to the spatial and resource limitations of rural settlements, the influx of urban migrants frequently displaces original villagers, forcing them to relocate to nearby towns or construct new homes elsewhere. This phenomenon poses challenges to the long-term sustainability of villages. Therefore, whether the impact of residential migration on the overall spatial layout of the village is destructive or a reasonable modification needs to be evaluated from a much more long-term perspective.

3.4. Migrants’ Utilization of Village Amenities and Public Spaces

In this section, to explore the lifestyle of incoming residents and their integration into village spaces, we conducted interviews with each migrant to gather insights into their daytime activities outside their houses. The section focuses on the use of public squares and communal buildings within the village. By documenting the nature and timing of public activities, we assess how migrants are assimilating into the village community.

Despite variations in individual migration motivations, urban migrants share a common driving force—the pursuit of rural natural and cultural environments. The transformation and expansion of rural public spaces provide migrants with venues to experience rural landscapes and lifestyles, making these spaces the most dynamic areas within the village where original residents, migrants, and tourists can directly interact. Unlike in urban settings, the third spaces created by migrants in rural villages exhibit greater openness, integrating certain characteristics of rural public spaces. Functioning as a “rural living room”, these spaces serve as vital hubs for social interactions between local villagers and incoming migrants, fostering deeper community engagement.

The varying levels of participation of new residents in the public life of the village correspond to their motivations for relocating, reflecting differences in their expectations and needs for rural living.

Figure 11, derived from temporal behavioral data collected through interviews, highlights the preferences of new residents regarding the use of public spaces within the village during the day, offering insights into their attitudes toward rural life. For instance, in Shishe Village, migrant H, who moved to the village in search of an idyllic rural lifestyle, currently operates a bar and restaurant. His engagement in village public life is high: in the mornings, he participates in recreational activities, after which he returns to his house to work. At noon, he enjoys a coffee at a local café, engaging in social interactions with both villagers and other migrants. In the evening, he returns to manage his bar, exemplifying the active involvement of new residents in village life. The frequency and enthusiasm of participation in rural public life vary among migrants, influenced by their original motivations for migration. The rural community’s interpersonal relationships and lifestyle appeal to different migrants in unique ways, shaping their level of engagement with village life.

The increased demand for village facilities by new residents stimulates the renewal and enhancement of these facilities, ultimately improving the overall service of public infrastructure in the village. Through their engagement with public spaces, both migrants and original inhabitants are able to better integrate, fostering a more cohesive village community. However, this interaction may disrupt the traditional lifestyles of the original residents, highlighting the need for ongoing observation and research on the dynamics of integration and interaction between these groups.

The relationship between migrants and original residents is inherently complex. Firstly, they share an economic relationship, as migrants often lease homesteads or houses from original residents, creating a competitive dynamic over spatial resources. Secondly, migrants serve as a bridge connecting the village to urban resources, while the presence of original residents fulfills migrants’ idealized vision of traditional rural life. Furthermore, both groups collectively drive the transformation of traditional villages into new community models, as the development of a better rural community aligns with their shared interests. Therefore, a continuous assessment of these dynamics is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the evolving relationships among return migrants and original rural residents.

4. Discussions

The observed rural return process in the selected villages highlights profound spatial and social transformations occurring in rural China. Although the proportion of incoming migrants remains relatively small, not exceeding 30% of the village population, the continuous return of migrants has gradually reshaped the spatial layout of these villages, fostering a new structure that integrates traditional elements with modern functional demands. Migrants often aim to preserve the historical and cultural significance of traditional rural architecture while incorporating contemporary functional needs. This dual approach has created a distinctive rural identity, gradually forming a more complex spatial pattern where local residents and urban-to-rural migrants coexist. These findings align with those of the aforementioned literature [

22] on “third spaces”, which suggests that migration often contributes to the formation of a “third space” in rural areas, facilitating new forms of social interaction and community engagement. This process holds significant value in revitalizing rural areas and promoting economic development.

The role of migration in reshaping rural space is further complicated by the dynamic interactions between new residents and local villagers. By categorizing migrants based on their purpose of relocation, place of origin, and duration of residence, this study identifies 10 distinct migration types. Notably, short-term rural residency is the most prevalent, indicating that many migrants do not completely sever ties with urban life but instead maintain dual urban–rural living arrangements, thereby facilitating the flow of resources between urban and rural areas. As the migrant population increases, so does the demand for public spaces and service facilities, driving improvements in infrastructure. This demand stems not only from migrants but also from broader developmental needs within the villages. While both migrants and local residents contribute to the revitalization of public spaces, differences in their expectations for rural life occasionally lead to tensions. Younger migrants, in particular, tend to introduce new lifestyles that challenge traditional customs, changes that may not always be well-received by local villagers. Although these shifts are often perceived as indicators of progress, careful attention must be paid to ensure that the interests and cultural practices of local residents are not marginalized.

While the most immediate impact of rural return is evident in the transformation of physical space, the social integration of migrants into village life is equally important and even more complex. Migrants seeking a rural lifestyle tend to integrate more deeply into the village’s social structure, actively participating in public activities and utilizing local resources. In contrast, those primarily focused on employment or business opportunities may prioritize professional development over social engagement. These differences in motivation reflect varying degrees of social participation, which in turn influence village cohesion. The spatial transformations observed in this study indicate that migration to rural areas enhances social cohesion and participation, albeit with characteristics shaped by China’s unique context. While migrants introduce modern functions into rural spaces, it remains to be seen whether these spatial changes represent a reasonable adaptation or a disruptive force, reflecting the inherent tension between modern needs and traditional ways of life.

Furthermore, previous studies [

24,

25] have explored ways to mitigate social tensions between incoming migrants and local residents. This study extends such discussions by situating these social interactions within the spatial transformations induced by rural return. The findings suggest that new residents, through their utilization of rural public facilities, facilitate the integration of different social groups and contribute to the upgrading of rural infrastructure. This indicates that beyond government policies, migrants themselves have become a crucial driving force in rural revitalization.

By examining how urban-to-rural migration reshapes both physical spaces and social relations, this study enriches discussions on rural return in the Chinese context. While the existing literature predominantly focuses on economic and policy dimensions of migration, this study underscores the spatial aspect, offering new insights into how migration drives spatial transformation. The findings suggest that rural return is not merely an individual response to a pastoral lifestyle but also a critical factor in the broader process of rural revitalization. However, further research is required to fully understand the long-term implications of these transformations. Given the limitations of the sample size and observation period, the generalizability of the current findings may be constrained. Future studies should expand the research scope, incorporating broader case studies and longitudinal data to better explore the multidimensional impacts of rural return on China’s rural physical and social landscapes.

5. Conclusions

This study examines the impact of urban-to-rural migration on the spatial structure of these villages in Zhejiang Province. Through an analysis of migration patterns, residential choices, and spatial transformations, the research explores how urban-to-rural migrants reshape overall village spatial configuration and integrate into rural communities.

From this research, it was found that:

We integrated economic and demographic data to map the landscape of rural development and the phenomenon of rural return in Zhejiang Province, while further examining the appeal of traditional villages’ living environments for incoming migrants. The selection of residential locations by migrants reflects their specific needs, with the conversion of single-family homes into mixed-use commercial and residential spaces being the most prevalent strategy. Migration patterns were categorized into ten primary types, with short-term workers representing the largest group. Dual residency, in which migrants split their time between urban and rural areas, emerged as the dominant migration trend.

Migrants primarily consist of individuals, families, and corporate entities. Their construction activities are predominantly characterized by repairs and minor renovations, with a limited number of newly constructed buildings scattered throughout the villages. The transformation of village spaces occurs incrementally, with migrant-occupied areas gradually integrating into the traditional village fabric, largely driven by the personal actions of the migrants. The vitality brought by return migration is primarily reflected in the extent to which migrants engage in public life, including their use of public spaces and facilities and their interactions with local residents. While motivations for engaging in public life vary, the presence of migrants plays a key role in shaping village dynamics and contributes to the ongoing improvement of rural living conditions.

When incoming migrants introduce urbanized lifestyles into rural areas, it inevitably exerts some negative impacts on the traditional village landscape. However, overall, such a migration has contributed to rural development, with limited and well-managed migration offering more benefits than drawbacks. Throughout the process of rural return, the resources and lifestyles brought from cities drive spatial transformations, shaping new characteristics in the rural landscape. This study is limited by insufficient manpower and methodological constraints, with a small sample size that restricts the ability to gather broader data and derive more objective patterns. To address this limitation, future research could explore new methodologies and establish a larger research team to expand the sample size, thus providing more robust data to support the identification of the richness and complexity of rural return phenomena. Furthermore, this study examined the spatial effects of rural return at the village scale, shedding light on its role in village evolution. Building upon this, the next phase of research should focus on a more micro and specific architectural scale, closely aligned with the daily work and life of migrants, to explore the adaptive transformations migrants make to rural architectural spaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.J. and N.S.; methodology, Z.J and Y.P.; software, Z.J.; validation, Z.J and N.S.; formal analysis, Z.J. and N.S.; investigation, Z.J., Y.P., and K.G.; resources, K.G.; data curation, Z.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.J.; writing—review and editing, Z.J. and N.S.; visualization, Z.J.; supervision, N.S. and K.G.; project administration, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the rural space research team at Southeast University, guided by Gongkai, for their valuable assistance during the investigation. We also extend our sincere thanks to Qi Yingtao of Xi’an Jiaotong University for his guidance throughout the investigation and the process of writing this paper. Meanwhile, we would also like to thank the staff of the three village committees for their support, as well as the migrants residing in the three villages for their cooperation during the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yifei Pei was employed by the company Jiangsu Institute of Urban & Rural Planning and Design Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Historic Achievements in Rural Development, A New Chapter in Rural Revitalization: The 18th Report in the Series on 75 Years of Economic and Social Development in New China. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/sjjd/202409/t20240923_1956627.html (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Wen, Q.; Zheng, D.; Shi, L. Themes Evolution of Rural Revitalization and its Research Prospect in China from 1949 to 2019. Prog. Geogr. 2019, 38, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Rural Transformation Development and New Countryside Construction in Eastern Coastal Area of China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2007, 62, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. The Process of Rural Development and Paths for Rural Revitalization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 1408–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Policy-oriented Rural Development in China and Its Potential Influence on Rural Development in Africa. Afr. Study Monogr. Suppl. Issue 2018, 57, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; de Vries, W.T. A Discourse Analysis of 40 Years Rural Development in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s Rural Revitalization and Development: Theory, Technology and Management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Coordinated Promotion of Plan Implementation. Implementation Report on the Rural Revitalization Strategy Plan (2018–2022); China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 35–48. ISBN 9787109300019. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, A.J. Counter urbanisation in Western Europe. Prog. Plan. 1982, 17, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuguitt, G.V.; Beale, C.L. Population Trends of Nonmetropolitan Cities and Villages in Subregions of the United States. Demography 1978, 15, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H.; Abrams, J. Amenity Migration: Diverse Conceptualizations of Drivers, Socioeconomic Dimensions, and Emerging Challenges. GeoJournal 2009, 76, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuno, H. The Increase of Migrants into Local Areas and Regional Correspondence: What does “Return to the Country” Mean for Local Areas? Ann. Assoc. Econ. Geograph. 2016, 62, 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Factors Affecting Urban-to-Rural Migration. Growth Change 1983, 14, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, N.Y. Return to the countryside: An Ethnographic Study of Young Urbanites in Japan’s Shrinking Regions. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 107, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kubota, H.; Shigeto, S.; Yoshida, T.; Yamagata, Y. Diverse Values of Urban-to-Rural Migration: A Case Study of Hokuto City, Japan. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 87, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, L. Towards Sustainable Rural Japan: A Case Study on Urban-Rural Migration Motives. Available online: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch/ (accessed on 30 June 2016).

- Haartsen, T.; Thissen, F. The Success–Failure Dichotomy Revisited: Young Adults’ Motives to Return to Their Rural Home Region. Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Oka, E. A Study on Conservation and Regeneration of Landscape of “Yikeyin” by Development Company and Immigrants. J. Archit. Plann. AIJ 2022, 87, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Tani, M. The Relationship Between the State of Vacant Houses in the Rural Return Phenomenon n and Increase in the Number of Migrants, A Dynamic analysis of Housing Use Over a Ten-year Period in Ogijima, Kagawa, prefecture, a Small Farming and Fishing Village in a Remote Island Suffering from Depopulation and Aging. J. Archit. Plann. AIJ 2023, 88, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, H.; Otsuki, T. A Study on Gradual Formation of Living Base Places on the Moving Process to the Villas Area in Hara Village, Nagano Prefecture. AIJ J. Technol. 2021, 27, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 55–73. ISBN 9781569246818. [Google Scholar]

- Cabras, I.; Mount, M.P. How Third Places Foster and Shape Community Cohesion, Economic Development. and Social Capital, The Case of Pubs in Rural Ireland. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 55, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhubart, D.; Kowalkowski, J.; Pillay, T. Third places in rural America: Prevalence and disparities in use and meaningful use. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 104, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutaro, T.; Masayuki, Y. The Importance of Daily Relationships in Mitigating Conflicts between Migrant Entrepreneurs and Local Residents in Depopulated Japan: Case Study of Minami-Izu, Shizuoka Prefecture. E-J. GEO 2024, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, M. Sociological Reconsideration of the Recent Phenomenon of Urban Population Movement into Underpopulated Rural Areas. Soshiroji 2000, 44, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; He, Q.; Long, H.; Zhan, Y.; Liao, L. Rural return migration in the post COVID-19 China: Incentives and barriers. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 107, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.; Pang, G.; Zeng, G. Entrepreneurial effect of rural return migrants: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1078199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Cheng, M. Return Migration and Economic Outcomes in Rural China. Sociol. Dev. 2023, 9, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Causes and Consequences of Return Migration: Recent Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xia, X.; Wang, J. Anti-Urbanization, Return of Local Worthies and Rural Revitalization. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 1, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. “Local Return”: The Logic and Realizaiton Mechanism of Returning Youth’s Participation in Chinese Agricultural and Rural Modernizaition. J. ZhongZhou Univ. 2024, 41, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lin, C. The Evolutionary Logic of Differences in the Effectiveness of Rural Governance with Capable Returnees—A Longitudinal Observation of Tenure with Capable Returnees as Village Cadres in S Town. J. Nanchang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 55, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y. Re-Conceptualization and Prospects of Rural Social Space Reconstruction Processes in China: Based on the Perspective of Counter-stream of Rural-Urban Migration. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Rural Settlement of Urban Dwellers in China: Community Integration and Spatial Restructuring. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P. Anti-Urbanization and Rural Development: Evidence from Return Migrants in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 103, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z. Continuous Operating Mechanism and Construction Strategy Research of Rural Community in China—Classic Cases of Rural Construction in Taiwan and Mainland China; Southeast University: Nanjing, China, 2020; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council. Outline of the Integrated Development Plan for the Yangtze River Delta Region. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/201912/01/content_WS5de3a5c0c6d0bcf8c4c181e2.html. (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Statistics (Zhejiang General Investigation Team). Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 210–255. ISBN 978-7-5230-0173-8. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Museum of Traditional Chinese Villages. Directory of Traditional Chinese Villages. Available online: https://www.dmctv.cn/directories.aspx (accessed on 28 April 2018).

- Research Center for Xi Jinping’s Ecological Civilization Thought. Firmly Establish the Concept That Lucid Waters and Lush Mountains Are Invaluable Assets. Available online: https://www.prcee.org/yjcg/zzwz_70/wenzhang/202306/t20230614_html (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Qi, Y.; Saio, N. Possibility of Maintaining Original Habitation from the Viewpoint of Relationships Between “Old Village ”and“New village”, Lingquan Village in Guangzhong Area of Shanghai Province. J. Archit. Plann. AIJ 2020, 85, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odagiri, T. The Theory of Relationship Population and Its Development. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001203324.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2017).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).