Unravelling Ostrom’s Design Principles Underpinning Sustainable Heritage Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

- The engagement of the local community in the conservation process.

- Sustainable use and preservation of heritage places through appropriate use, adaptation, maintenance, and strategic and financial planning.

- How well the project contributes to the environmental sustainability and resilience of the heritage place.

- How well the project contributes to the local community’s socio-economic well-being, cultural continuum, and development needs.

- How well the project fosters local knowledge and living heritage.

- How well the project contributes to enhancing the quality of the urban, rural, and natural settings and spaces.

- The influence of the project on conservation practice and policy locally, nationally, regionally, or internationally.

3. Results and Discussion

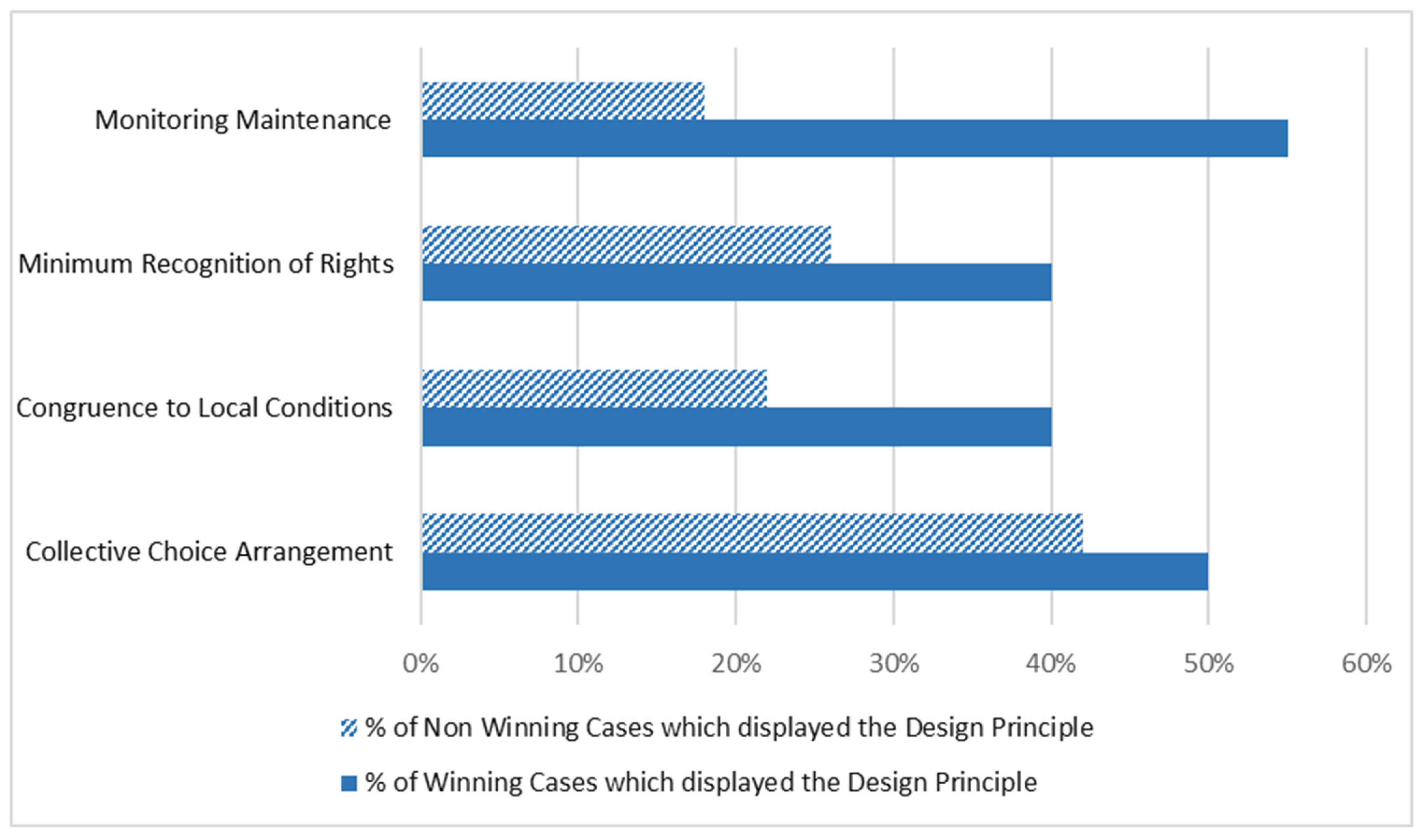

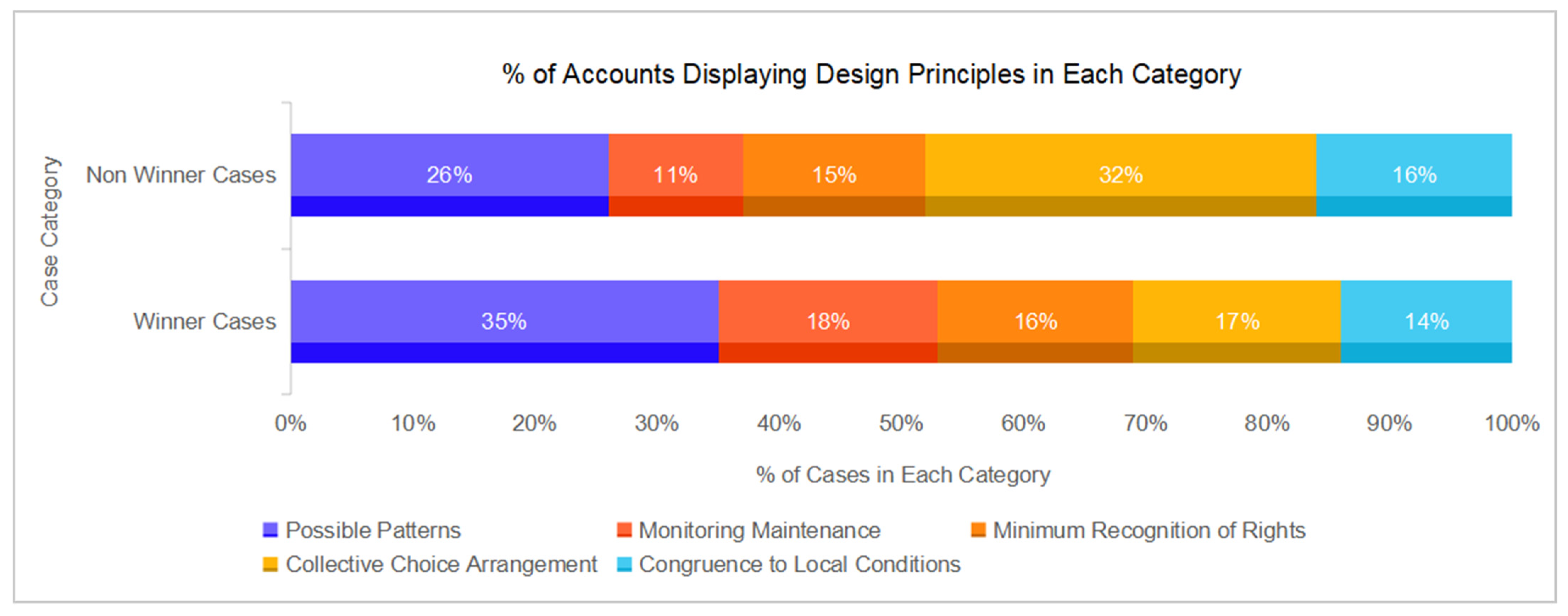

3.1. Overall Results

3.2. Congruence to Local Conditions

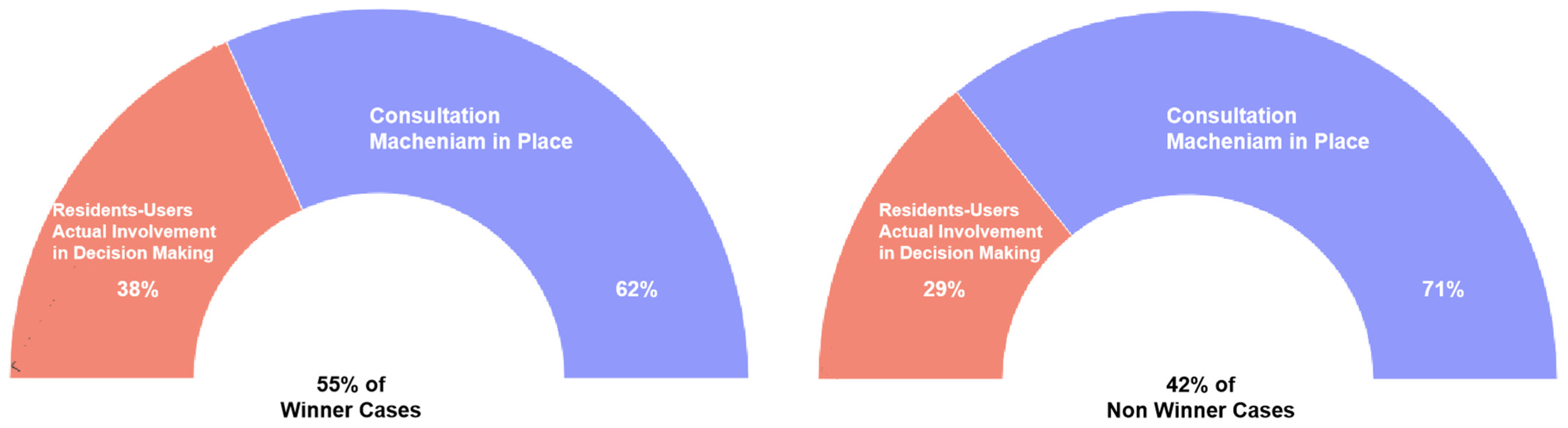

3.3. Collective Choice Arrangement

3.4. Monitoring System

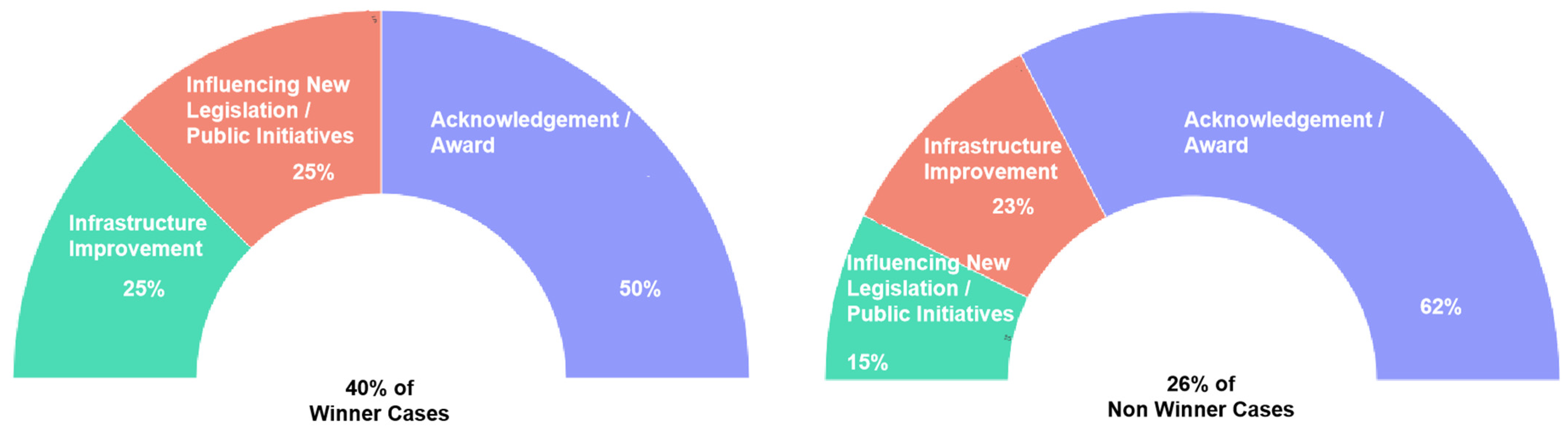

3.5. Minimum Recognition of Rights

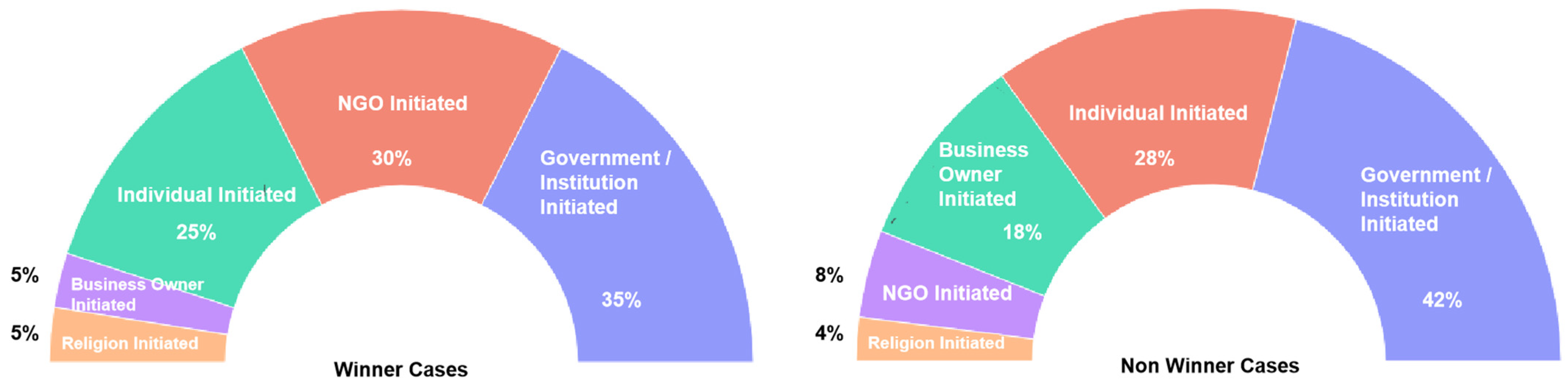

3.6. Nested Enterprise

4. Other Possible Patterns

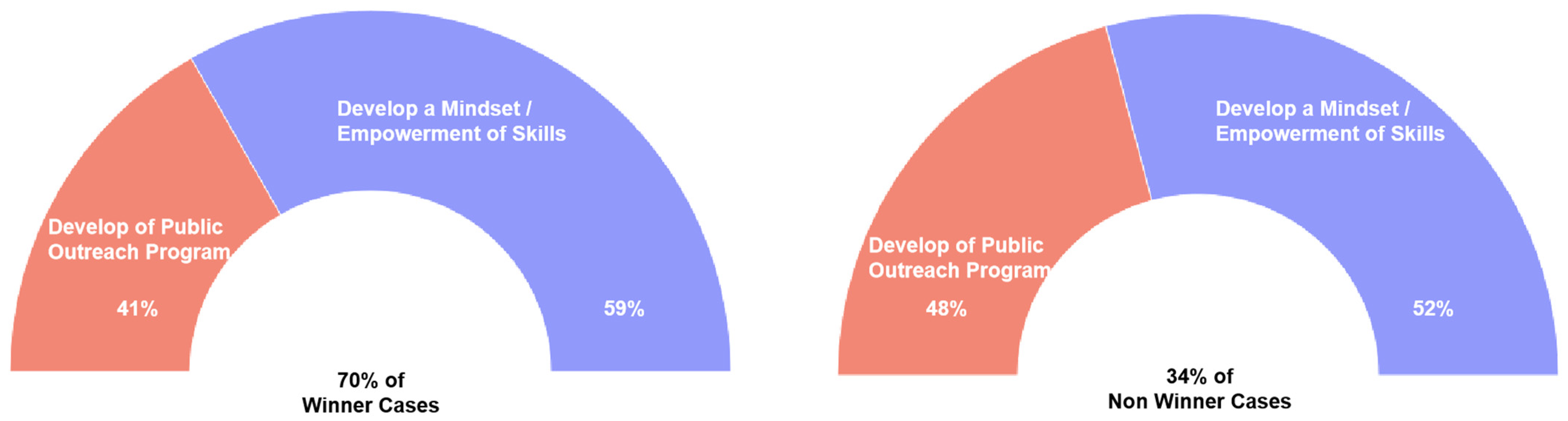

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chau, K.W.; Choy, L.H.T.; Lee, H.Y. Institutional arrangements for urban conservation. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.W. Transaction costs. In Encyclopedia of Law and Economics, Volume I: The History and Methodology of Law and Economics; Bouckaert, B., De Geest, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 893–926. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard, C.; Shirley, M.M. Advanced Introduction to New Institutional Economics; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, S.N.S. Economic organisation and transaction costs. In Allocation, Information and Markets; Eatwell, J., Milgate, M., Newman, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1989; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S.; Gould, P.G. Sustainable development: Heritage, community, economics. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.W. Adaptive reuse of traditional Chinese shophouses in government-led urban renewal projects in Hong Kong. Cities 2014, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.; Gould, P. Collective action dilemmas at cultural heritage sites: An application of the IAD-NAAS framework. Int. J. Commons 2021, 15, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holahan, R.; Lubell, M. Collective action theory. In Handbook on Theories of Governance: Second Edition; Ansell, C., Torfing, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Institutional rational choice: An assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. In Theories of the Policy Process; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 21–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, P.G. Considerations on governing heritage as a commons resource. In Collision or Collaboration: Archaeology Encounters Economic Development; Pyburn, K.A., Gould, P.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons: The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The “By-Product” and “Special Interest” Theories. In The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Second Printing with a New Preface and Appendix; Harvard University Press: Harvard, UK, 1971; pp. 132–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, M.D. The IAD framework in action: Understanding the source of the design principles in Elinor Ostrom’s governing the commons. In Elinor Ostrom and the Bloomington School of Political Economy, Volume 3: A Framework of Policy Analysis; Cole, D.H., McGinnis, M.D., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.; Arnold, G.; Villamayor Tomás, S. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, J.A.; Barnett, A.J.; Perez-Ibara, I.; Brady, U.; Ratajczyk, E.; Rollins, N.; Rubiños, C.; Shin, H.C.; Yu, D.J.; Aggarwal, R.; et al. Explaining success and failure in the commons. Int. J. Commons 2016, 10, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depari, C. Assessing indigenous forest management in Mount Merapi National Park Based on Ostrom’s Design Principles. For. Soc. Online 2023, 7, 380–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Angelo, J.; McCord, P.F.; Gower, D.; Carpenter, S.; Caylor, K.K.; Evans, T.P. Community water governance on Mount Kenya: An assessment based on Ostrom’s Design Principles of natural resource management. Mt. Res. Dev. 2016, 36, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryanto, T.; Van Zeben, J.; Purnhagen, K. Ostrom’s Design Principles as steering principles for contractual governance in “hotbeds”. For. Soc. Online 2022, 6, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, K.; Richards, G. An alternative policy evaluation of the British Columbia carbon tax: Broadening the application of Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for managing common-pool resources. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, D.; Jin, L. Different paths lead to the same success: Examining Design Principles in grassland collective governance in China. Land 2024, 13, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Ostrom in the city design principles and practices for the urban commons. In Routledge Handbook of the Study of the Commons; Hudson, B., Rosenbloom, J., Cole, D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuvela, A.; Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Partnerships in heritage governance and management: Review study of public–civil, public–private and public–private–community partnerships. Heritage 2023, 6, 6862–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, C. The public-private-people partnership (P4) for cultural heritage management purposes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitug, M.C. Avoiding the tragedy: Recommendations for an appropriation of Elinor Ostrom’s design principles in governing a commons within the context of built heritage conservation in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium “Heritage and Democracy”, New Delhi, India, 13–14 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Polko, A. Governing the urban commons: Lessons from Ostrom’s work and commoning practice in cities. Cities 2024, 155, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ling, G.H.; Wang, H.K. Sustainable collective action in high-rise gated communities: Evidence from Shanxi, China using Ostrom’s design principles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Bangkok. Overview: UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation. In Asia Conserved, Volume III: Lessons Learned from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Culture Heritage Conservation (2010–2014); Chapman, W., Ed.; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kongsasana, M.S.; Ayudhya, S.P.N. The lessons learned from the UNESCO Asia–Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation (2000–2013). Ph.D. Thesis, Silpakorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt, R. Overview: Twenty years of the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation (2000–2019). In Asia Conserved, Volume IV: Lessons Learned from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Culture Heritage Conservation (2015–2019); Chapman, W., Ed.; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Bangkok. 2012–2014: Jury recommendation for innovation. In Asia Conserved, Volume III: Lessons Learned from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Culture Heritage Conservation, 2010–2014; Chapman, W., Ed.; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; pp. 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Bangkok. Award Regulations: 2015–2016 UNESCO Award for New Design in Heritage Contexts. In Asia Conserved, Volume IV: Lessons Learned from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Culture Heritage Conservation (2015–2019); Chapman, W., Ed.; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020; pp. 406–407. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.E. Doing Research in the Real World; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E.R. The Practice of Social Research; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, G.J. The Organization of Industry; R.D. Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Araral, E. Reply to: Design principles in commons science: A response to “Ostrom, Hardin and the commons” (Araral). Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 61, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Bangkok. UNESCO Asia-Pacific Award for Cultural Heritage Conservation Winners Profiles. 2022. Available online: https://articles.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2023/06/2022-winners.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. The capacity of water governance to deal with the climate change adaptation challenge: Using fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis to distinguish between polycentric, fragmented and centralised regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.R.; Sousa, P.F.; Tereso, A. Stakeholder Management and Communication Management in Non-Governmental Organizations: A systematic literature review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 239, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. Carol Dweck revisits the growth mindset. Educ. Week 2015, 35, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

| Ostrom’s Design Principles | Design Principles Adapted to Heritage Projects | Guide Questions Used in Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Clearly defined boundaries | Determining the boundaries of the heritage site and who has the right to use it is important. | Is it clear who the project’s beneficiaries and supporters (as well as potential ones) are? Are the property boundaries of the site clear? (It is difficult to differentiate award recipients and non-recipients) |

| Congruence to local conditions and proportional equivalence between local benefits and costs | The benefits of conserving the heritage site should be proportional to the costs of conservation. The approach taken meets the needs of the local community. | Is the approach taken meeting the needs of the local community? Are the local workers engaged in the project? Are local materials being used? |

| Collective choice arrangements | People who use the heritage site should be involved in decision-making. As they shoulder the least cost in obtaining information about the site’s condition, they are in an advantageous position to adjust or update the operational rules. | Is there a mechanism for project stakeholders to have a say in projects’ operations to reflect the latest local conditions? |

| Monitoring | Regular monitoring of the heritage site and how it is used can help identify problems early on and prevent further damage. | Is there a monitoring or maintenance plan in place for the project? Are the people monitoring the condition and usage of the resource accountable to the users? |

| Graduated sanctions | Sanctions should be in place for those who violate the rules of the heritage site. These sanctions should be proportional to the severity of the violation and should be enforced consistently. | Are there means to check accountability among the stakeholders of the project? Are the sanctions for those who do not cooperate as promised reasonable? (Not possible to determine using this dataset) |

| Conflict resolution mechanisms | Do appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local mechanisms to resolve conflicts that arise between different stakeholders? This can help prevent disputes from escalating. | Does the project have a mechanism to resolve conflicts locally among different project stakeholders? (Not possible to determine using this dataset) |

| Recognition of rights | The rights of all stakeholders should be somehow recognised and not challenged by external governmental authorities. | Are stakeholders able to organise themselves without restrictions from the authorities? Is there minimum recognition from government authorities for the community project? |

| Nestled enterprises | Are various governance activities organised in multiple layers of nested enterprises? | Who are the leading actors? How do they interact with other layers of management on the site? (It is not possible to completely determine this principle using the dataset) |

| Patterns (in Order of Importance) | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Community Involvement and Empowerment | Projects that actively involve and empower the local community in the conservation process tend to receive higher awards. This includes training local artisans, engaging residents in decision-making, and ensuring that the project benefits the community socially and economically. |

| Technical Excellence and Authenticity | Projects that demonstrate high technical standards, meticulous research, and the use of traditional materials and techniques are highly valued. Authenticity in preserving the original character and fabric of the building is crucial. |

| Holistic and Comprehensive Approach | Projects that adopt a holistic approach, addressing not only the physical restoration but also the social, cultural, and economic aspects of the site, are highly regarded. This includes integrating modern amenities while preserving historical integrity. |

| Innovative Solutions and Adaptive Reuse | Projects that creatively adapt historic buildings for modern use while preserving their historical significance are recognised. Innovative solutions to technical challenges and the sensitive integration of new functions are important. |

| Principle Indicators | Modified Definition by Cox et al. [12] | Adapted Definition to Heritage Projects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Congruence to Local Conditions | ||

| 2.5 | Use of Local Materials | 2A Congruence with local conditions: Appropriation and provision rules are congruent with local social and environmental conditions. 2B Appropriation and provision: The benefits obtained by users from a common-pool resource (CPR), as determined by appropriation rules, are proportional to the amount of inputs required in the form of labour, material, or money, as determined by provision rules. | The project sources locally produced/available materials for construction |

| 2.6 | Use of Local Workers/Artisans | The project hires local workers/artisans in the construction team. | |

| 3 | Collective Choice Arrangement | ||

| 3.1 | Consultation Mechanism in Place | Collective choice arrangements: Most individuals affected by the operational rules can participate in modifying the operational rules. | The main project team consults/collects information from various stakeholder groups for their aspects of the project. |

| 3.4 | Residents-Users Involvement in Decision-Making | Residents/future users are involved in the project and are able to make decisions. | |

| 4 | Monitoring Maintenance | ||

| 4.1 | Clear Monitoring Guidelines | 4A Monitoring users: Monitors who are accountable to the users monitor the appropriation and provision levels of the users. 4B Monitoring the resource: Monitors who are accountable to the users monitor the condition of the resource. | Monitoring guidelines have been developed to outline responsibilities among different stakeholders. |

| 4.2 | Community Monitoring/Wide Range of Individuals Involved | Other than groups directly involved in the project, affiliated individuals are also attracted to contribute and monitor the project. | |

| 6 | Minimum Recognition of Rights | ||

| 6.1 | Acknowledge/Award | The rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities. | The project won other relevant local awards/recognitions. |

| Influencing New Legislation/Public Initiatives | The project’s experience contributes to new legislation/organisation development, benefitting other later heritage projects. | ||

| 6.2 | Infrastructure Improvement | The project influences regional infrastructure or living standard improvements. | |

| 8 | Nested Enterprise | ||

| 8.1 | Business Owner Initiated | Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organised in multiple layers of nested enterprises. | A business entity is the leading actor in the project. |

| 8.2 | Government Initiated | A government body is the leading actor in the project. | |

| 8.3 | Individual Initiated | Individuals/individual families are the leading actors in the project. | |

| 8.4 | NGO Initiated | An NGO is the leading actor in the project. | |

| 8.5 | Religious Group Initiated | A religious organisation is the leading actor in the project. | |

| 9 | Possible Patterns | ||

| 9.1 | Development of Public Outreach Programs | N/A | Public outreach programs are developed to share project experience and heritage values. |

| 9.4 | Develop a Mindset/Empowerment of Skills | The project provides opportunities for stakeholders to enhance their understanding/skills in line with conserving the heritage. | |

| Ranking of Principles—Winning Cases | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Possible Patterns—“People–Growth-oriented” |

| 1.1 | Develop a Mindset/Empowerment of Skills |

| 1.2 | Development of Public Outreach Program |

| 2 | Monitoring Maintenance |

| 2.1 | Community Monitoring/Wide Range of Individuals Involved |

| 2.2 | Clear Monitoring Guidelines |

| 3 | Collective Choice Arrangement |

| 3.2 | Consultation Mechanism in Place |

| 3.3 | Resident-User Involvement in decision-making |

| 4 | Minimum Recognition of Rights |

| 4.1 | Acknowledge/Award |

| 4.2 | Infrastructure Improvement |

| 4.3 | Influencing New Legislation/Public Initiatives |

| 5 | Congruence to Local Conditions |

| 5.1 | Adjusted to Local Needs/Conditions |

| 5.2 | Use of Local Workers/Artisans |

| 5.3 | Use of Local Materials |

| 6 | Preliminary Nested Enterprise (leading actors only) |

| 6.1 | NGO Initiated |

| 6.2 | Government Initiated |

| 6.3 | Individual Initiated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chua, M.H.; Yau, Y.; Jian, W. Unravelling Ostrom’s Design Principles Underpinning Sustainable Heritage Projects. Buildings 2025, 15, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071152

Chua MH, Yau Y, Jian W. Unravelling Ostrom’s Design Principles Underpinning Sustainable Heritage Projects. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071152

Chicago/Turabian StyleChua, Mark Hansley, Yung Yau, and Wanling Jian. 2025. "Unravelling Ostrom’s Design Principles Underpinning Sustainable Heritage Projects" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071152

APA StyleChua, M. H., Yau, Y., & Jian, W. (2025). Unravelling Ostrom’s Design Principles Underpinning Sustainable Heritage Projects. Buildings, 15(7), 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071152