Revitalization of Traditional Villages Oriented to SDGs: Identification of Sustainable Livelihoods and Differentiated Management Strategies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

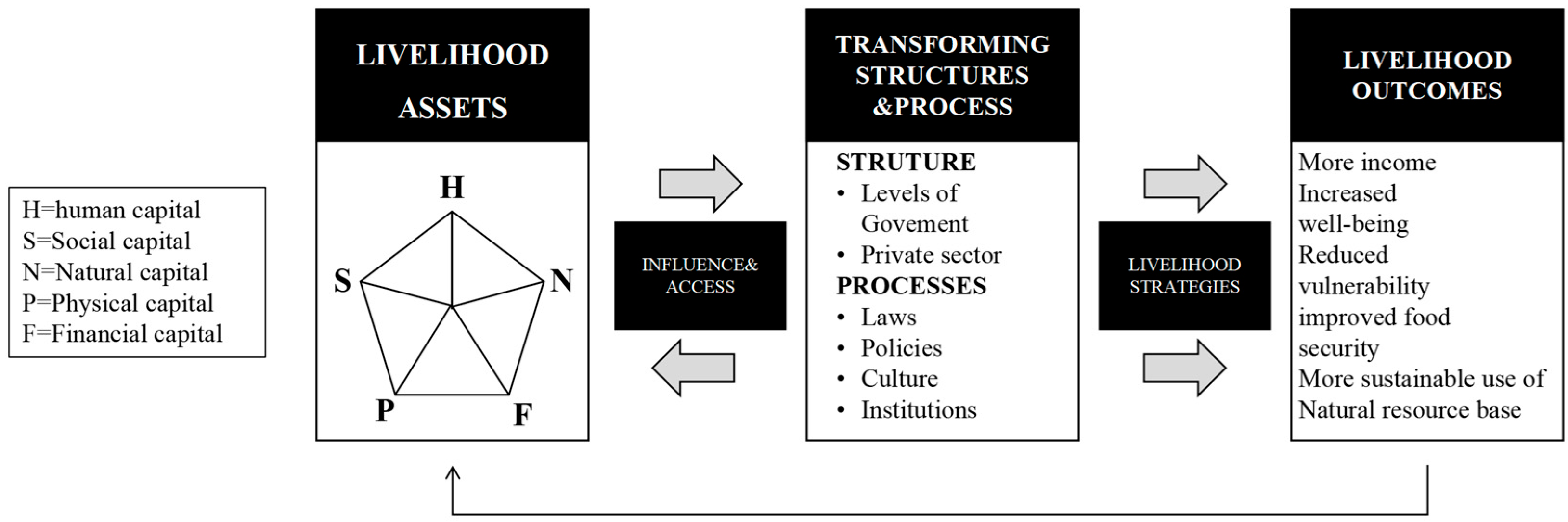

2.1. A Sustainable Livelihood Framework for Traditional Villages

2.2. Multiple Path of Traditional Village Livelihood Strategy

2.3. Decision-Making Tools Utilized in Rural Areas Studies

3. Materials and Methods

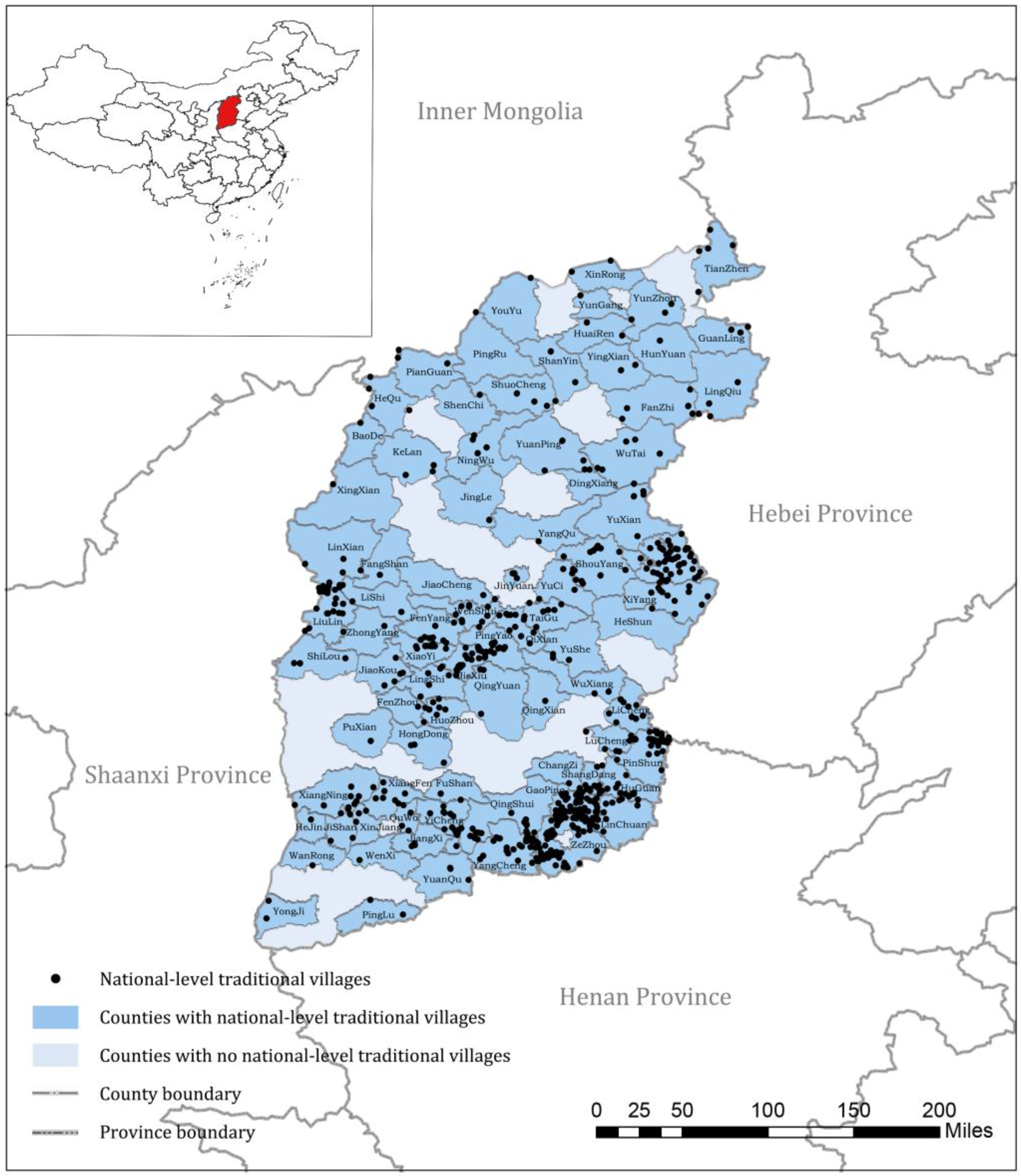

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Methods

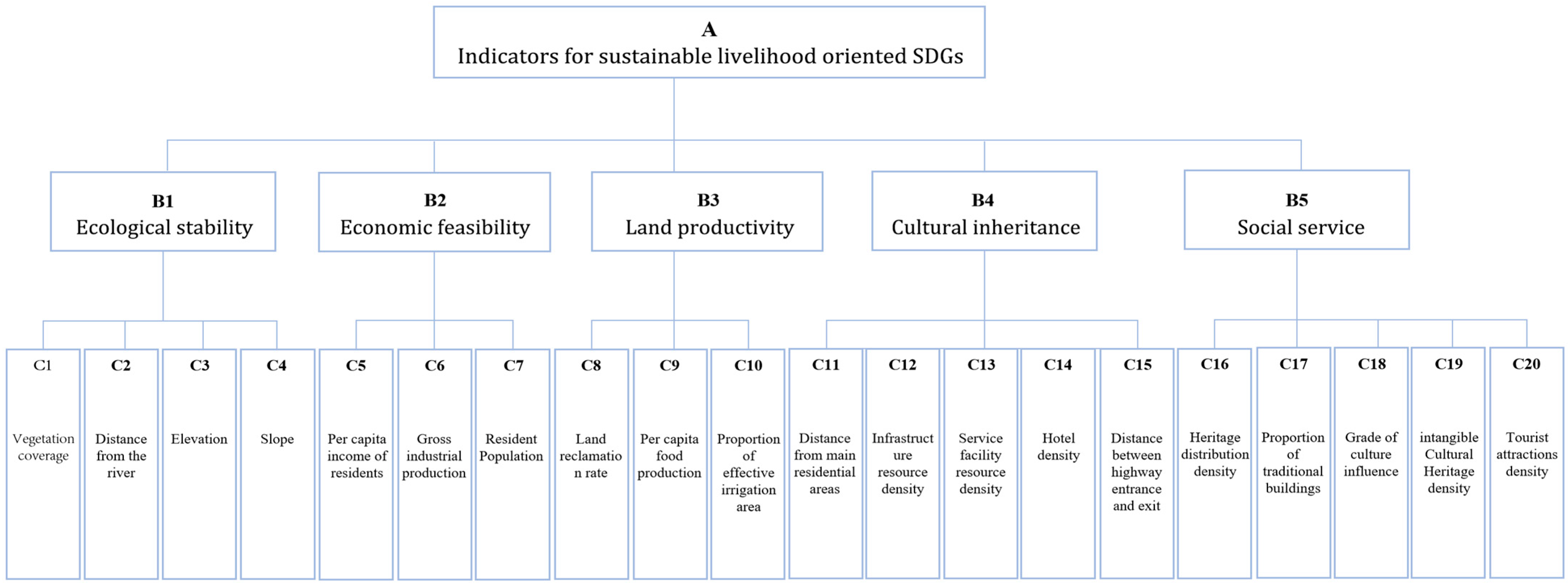

3.3.1. Indicators for Sustainable Livelihood Assessment Oriented to SDGs

3.3.2. The Correlation Test and Geographically Weighted Regression

3.3.3. The Self-Organizing Maps (SOMs)

4. Results

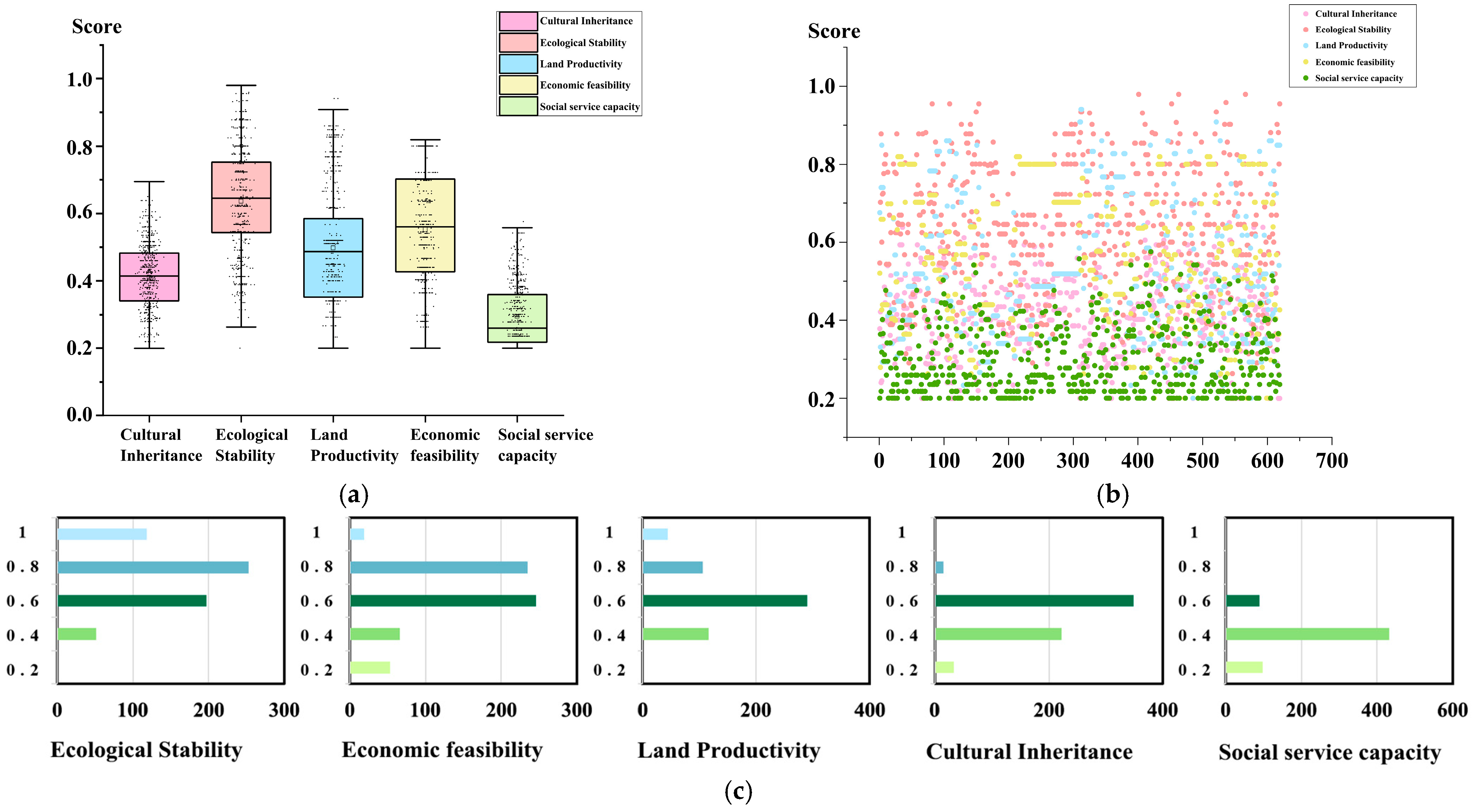

4.1. Statistical Results and Spatial Characterization

4.2. Trade-Offs and Synergies

4.3. Identification Results of Village Livelihood Types

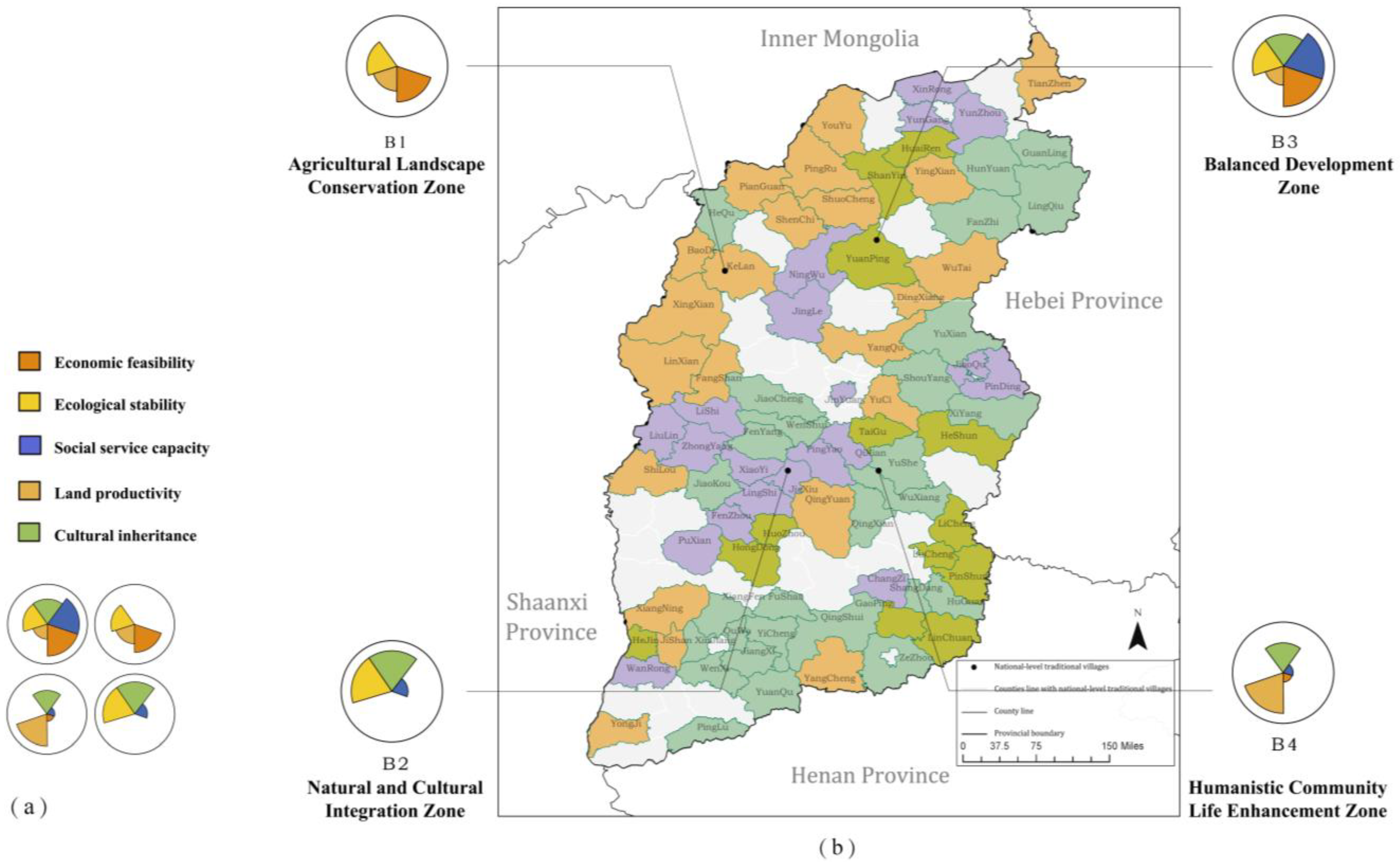

4.4. Revitalization Policy for “Multi-Livelihoods Zoning”

5. Discussion

5.1. Obstacles to Revitalizing Traditional Villages in Shanxi

5.2. Strengths of Livelihood Diversification in Rural Revitalization

5.3. Policy Suggestions

5.3.1. Enhancing Social Services

5.3.2. Value the Synergies Between Different Assets

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prabowo, B.; Salaj, A. Identifying Overtourism Impacts on the Informal Sector’s Livelihoods in Urban Heritage Area. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 738, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J. Evolutionary process and mechanism of population hollowing out in rural villages in the farming-pastoral ecotone of Northern China: A case study of Yanchi County, Ningxia. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-dimensional hollowing characteristics of traditional villages and its influence mechanism based on the micro-scale: A case study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Long, H.; Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal pattern of China’s rural development: A rurality index perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barberà-Mariné, M.-G.; Fabregat-Aibar, L.; Ferreira, V.; Terceño, A. One Step Away from 2030: An Assessment of the Progress of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the European Union. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2024, 36, 1372–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, R.; Dai, M.; Yanghong, O. The influence of culture on the sustainable livelihoods of households in rural tourism destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J. Rural geography I: Changing expectations and contradictions in the rural. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, J. Population Growth, Agricultural Intensification, Induced Innovation and Natural Resource Sustainability: An Application of Neoclassical Growth Theory. Agric. Econ. 1998, 19, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, R.; Pender, J. Rural diversity and heterogeneity in less-favoured areas: The quest for policy targeting. Food Policy 2004, 29, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, I.A. The structure and pattern of rurality in Nigeria. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Prioritising SDG targets: Assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z. Rural Tourism Competitiveness and Development Mode, a Case Study from Chinese Township Scale Using Integrated Multi-Source Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dfid. Overview of the Key Sheets for Sustainable Livelihoods—Key Sheets for Sustainable Livelihoods; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Solesbury, W. Sustainable Livelihoods: A Case Study of the Evolution of DFID Policy; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003; Volume 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.J. Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analysing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty in the Andes. World Dev. 1999, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding in the Context of Tourism: A Case Study of Lijiang, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Deakin University, Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scazzosi, L. Rural landscape as heritage: Reasons for and implications of principles concerning rural landscapes as heritage ICOMOS-IFLA 2017. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S. Study on the Protection and Development of Farming-Type Traditional Village Landscape Under the Concept of Sustainability–A Case Study of Western Henan. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Green Building, Civil Engineering and Smart City, Guilin, China, 8–10 April 2022; pp. 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, W.; Hu, B.; Guo, Z.; Huang, X. Evaluating the sustainability of land use integrating SDGs and its driving factors: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, China. Cities 2023, 143, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N.; Newsham, A.; Rigg, J.; Suhardiman, D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.L.; Ampt, P.R. Rapid rural appraisal: A participatory problem formulation method relevant to Australian agriculture. Agric. Syst. 1992, 38, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhifei, L.; Qianru, C.; Hualin, X. Comprehensive Evaluation of Farm Household Livelihood Assets in a Western Mountainous Area of China: A Case Study in Zunyi City. J. Resour. Ecol. 2018, 9, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Yu, H.; Chu, H.; Hu, M.; Xu, T.; Ju, L.; Hu, W.; Huang, H. Integrating land use functions and heavy metal contamination to classify village types. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Weinthal, E.; Bellemare, M.; Jeuland, M. Social capital, trust, and adaptation to climate change: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 36, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Güneralp, B.; Bailis, R.; Yohe, G.; Oliver, C. Evaluating the resilience of forest dependent communities in Central India by combining the sustainable livelihoods framework and the cross scale resilience analysis. Environ. Sci. Sociol. Curr. Sci. 2016, 110, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Pitaloka, A.; Abdurrahim, A. Sustainable Livelihoods Approach and Contemporary Research on Rural Social-Ecological Systems in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1275, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Liang, W. Evaluation system and influencing paths for the integration of culture and tourism in traditional villages. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 2489–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanan, L.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. How has rural tourism influenced the sustainable development of traditional villages? A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, M.; Lin, H. Deep Analysis of the Homogenization Phenomenon of the Ancient Water Towns in Jiangnan: A Dual Perspective on Landscape Patterns and Tourism Destination Images. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination—Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wu, X.; Tang, J.-J.; Zhang, J.-E.; Luo, S.-M.; Chen, X. Conservation of Traditional Rice Varieties in a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS): Rice-Fish Co-Culture. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, S.; Tang, J.; Chen, W. Design and research of digital twin platform for handicraft intangible cultural heritage -Yangxin Cloth Paste. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B. Towards a Participatory GIS: Evaluating Case Studies of Participatory Rural Appraisal and GIS in the Developing World. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2002, 29, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S.; Loë, R.; Kreutzwiser, R. Appropriate Public Involvement in Local Environmental Governance: A Framework and Case Study. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qubatee, W.; Ritzema, H.; Al-Weshali, A.; Steenbergen, F.; Hellegers, P. Participatory rural appraisal to assess groundwater resources in Al-Mujaylis, Tihama Coastal Plain, Yemen. In Groundwater; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Türk, E. Multi-criteria Decision-Making for Greenways: The Case of Trabzon, Turkey. Plan. Pract. Res. 2017, 33, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. Decision making—The Analytic Hierarchy and Network Processes (AHP/ANP). J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2004, 13, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z. Deep learning based identification and interpretability research of traditional village heritage value elements: A case study in Hubei Province. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, R. Spatial Distribution and Type Division of Traditional Villages in Zhejiang Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhong, Q.; Li, Z. Analysis of spatial characteristics and influence mechanism of human settlement suitability in traditional villages based on multi-scale geographically weighted regression model: A case study of Hunan province. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.; Jin, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, P. Evaluation and obstacle analysis of sustainable development in small towns based on multi-source big data: A case study of 782 top small towns in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J. Assessment of Sustainable Development Suitability in Linear Cultural Heritage—A Case of Beijing Great Wall Cultural Belt. Land 2023, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuraju, V.; Pradhan, P.; Haase, D.; Kropp, J.P.; Rybski, D. Relating SDG11 indicators and urban scaling—An exploratory study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H. A large-scale village classification model for tailored rural revitalization: A case study of Hubei province, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 2364–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitea, L.F. Typology of the romanian rural area based on the modernization and rural socio-economic development perspectives. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2022, 22, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Kong, Y.; Li, X. Analysis of types and changes of village-level economy in rural Gongyi city, Henan Province since 1990. 2008, 18, 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, X.; Sun, L.; Gong, Y. Spatial Evaluation of Villages and Towns Based on Multi-Source Data and Digital Technology: A Case Study of Suining County of Northern Jiangsu. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massini, G. Visualization and clustering of self-organizing maps. In Intelligent Data Mining in Law Enforcement Analytics: New Neural Networks Applied to Real Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kohonen, T. Essentials of the self-organizing map. Neural Netw. 2013, 37, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Yuan, S.; Prishchepov, A.V. Spatial-temporal heterogeneity of ecosystem service interactions and their social-ecological drivers: Implications for spatial planning and management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 189, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryhal, J.; Plavcová, E. On using self—Organizing maps and discretized Sammon maps to study links between atmospheric circulation and weather extremes. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 2678–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Luo, K.; Beggs, P.; Cheung, K.; Scorgie, Y. Insights into the implementation of synoptic weather-type classification using self-organizing maps: An Australian case study. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 35, 3471–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-S.; Dhakal, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Jang, G.-S. Examining village characteristics for forest management using self- and geographic self-organizing maps: A case from the Baekdudaegan mountain range network in Korea. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Mitchell, I.; Keelan, N. Maori Culture and Heritage Tourism in New Zealand. J. Cult. Geogr. 1992, 12, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Shannon, M. Exploring cultural heritage tourism in rural Newfoundland through the lens of the evolutionary economic geographer. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Lu, J.; Sun, D. Influence of Urban Agglomeration Expansion on Fragmentation of Green Space: A Case Study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Land 2022, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yurui, L.; Lu, Z.; Pan, W. What makes better village economic development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from 338 villages. Habitat Int. 2020, 106, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, P.; Lyu, D.; Zhao, Z. The role of small towns in rural villagers’ use of public services in China: Evidence from a national-level survey. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 100, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; van Wesemael, P.; Colenbrander, B.J. Youth participation in cultural heritage management: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 30, 56–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Mo, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, D. Evaluation of Community Resilience in Rural China—Taking Licheng Subdistrict, Guangzhou as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; He, X. Spatial Sifferentiation and Differentiated Development Paths of Traditional Villages in Yunnan Province. Land 2023, 12, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lee, I. Cognitive Recognition of Space and Social Connections of Traditional Villages in Shanxi Province: A Case Study of Ding, Shijiagou, and Yanjing Villages. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, L.; Tan, G. Identification and Hierarchy of Traditional Village Characteristics Based on Concentrated Contiguous Development—Taking 206 Traditional Villages in Hubei Province as an Example. Land 2023, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xi, M.; Wu, X. A social network analysis of tourism cooperation in the Yangtze River Delta: A supply and demand perspective. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, M.B. The Cittaslow philosophy in the context of sustainable tourism development; the case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, S. The potential of Cittaslow for sustainable tourism development: Enhancing local community’s empowerment. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 13, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Layer | Criteria | Indicators | Index Weight | SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable livelihood of traditional villages (A) | Cultural inheritance (B1) | Heritage distribution density (C1) | 0.0195 | SDG11.4 |

| Proportion of traditional buildings (C2) | 0.0446 | SDG11.4 | ||

| Grade of culture influence (C3) | 0.0616 | SDG11.4 | ||

| Intangible Cultural Heritage density (C4) | 0.0340 | SDG11.4 | ||

| Tourist attractions density (C5) | 0.0400 | SDG8.9 | ||

| Ecological stability (B2) | Vegetation coverage (C6) | 0.0775 | SDG15.2 | |

| Distance from the river (C7) | 0.0775 | SDG6.6 | ||

| Elevation (C8) | 0.0209 | SDG15.1 | ||

| Slope (C9) | 0.0242 | SDG15.1 | ||

| Land productivity (B3) | Land reclamation rate (C10) | 0.0595 | SDG2.1 | |

| Per capita food production (C11) | 0.1078 | SDG2.2 | ||

| Proportion of effective irrigation area (C12) | 0.0328 | SDG2.4 | ||

| Economic feasibility (B4) | Per capita income of residents (C13) | 0.0981 | SDG1.1/8.1/8.2 | |

| Gross industrial production (C14) | 0.0624 | SDG9.2 | ||

| Resident population density (C15) | 0.0395 | SDG11.1 | ||

| Social service capacity (B5) | Distance from airport and train station (C16) | 0.0177 | SDG11.a | |

| Infrastructure resource density (C17) | 0.0619 | SDG9.1 | ||

| Service facility resource density (C18) | 0.0574 | SDG6.2 | ||

| Hotel density (C19) | 0.0215 | SDG8.9 | ||

| Distance between highway entrance and exit (C20) | 0.0415 | SDG11.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, D.; Zhang, Y. Revitalization of Traditional Villages Oriented to SDGs: Identification of Sustainable Livelihoods and Differentiated Management Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071127

He D, Zhang Y. Revitalization of Traditional Villages Oriented to SDGs: Identification of Sustainable Livelihoods and Differentiated Management Strategies. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071127

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Ding, and Yameng Zhang. 2025. "Revitalization of Traditional Villages Oriented to SDGs: Identification of Sustainable Livelihoods and Differentiated Management Strategies" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071127

APA StyleHe, D., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Revitalization of Traditional Villages Oriented to SDGs: Identification of Sustainable Livelihoods and Differentiated Management Strategies. Buildings, 15(7), 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071127