Factors and Pathways to Enhance Resident Satisfaction in Old Residential Neighbourhood Renovation: A Configuration Analysis of Cases in Central Nanchang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Logic

2.1. Literature Review

| No | Souces | Methodology | Research Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nuo Chen, Dewei Fang [18] | Gradient Boosting Decision Trees and Impact Asymmetry Analysis Methods | Current social environment factors, including uncivilised behaviour, space occupation, and hygiene and cleanliness, exert a greater impact on the overall satisfaction. |

| 2 | Peng, WJ; Huang, YY; Li, CQ; Wang, YL [30] | Multiple linear regression analysis, factor analysis, and correlation analysis | It was found that resident satisfaction with building conditions, infrastructure, internal road traffic, and public environment significantly impacted their agreement with the renovation in the old neighbourhood. |

| 3 | Buchecker, M; Frick, J [31] | Standardised Cross-sectional Questionnaires, A structural equation model SEM | The degree of urbanisation of the setting had a direct negative influence on place attachment, while place attachment appeared to be a key moderator of, and a main driver for, place-satisfaction, civic participation, and proximity behaviour. |

| 4 | Zhen Feng, Qin Xiao, Jiang Yupei, Chen Hui [34] | Mixed Linear Regression Model | Zhen Feng’s study surveyed 40 neighbourhoods in Nanjing, China, and used mixed linear regression modelling to determine the relationship between community ICT use and community satisfaction. |

| 5 | Liu Ning, Han Qingyan, Liu Yachen [35] | Structural equation model | The renovation of community plumbing, building bodies, and landscaping had a significant positive impact on resident satisfaction; the renovation of community power lines and road traffic had a non-significant level of impact on resident satisfaction. |

| 6 | Wang Xiuli, Chen Li, Yuan Beifei [37] | Fuzzy Hierarchical Analysis (FAHP) and Machine Learning | The factors affecting residents’ satisfaction with the renovation of old neighbourhoods are living environment, supporting facilities, property management, construction environment, and community emotion. |

| 7 | Mizzo Kwon, Andrew C. Pickett, & Yunsoo Lee, SeungJong Lee [40] | Structural Equation Modelling | Community planners could use several practical neighbourhood improvement renovations to improve the overall health, happiness, and life satisfaction of their residents. |

| 8 | Moon,, Jae Heung; Jin, Kim Jong [41] | Multiple Regression Analysis. | Public participation and a sense of community had the greatest effect on residential satisfaction, followed by management satisfaction, facility satisfaction, and accessibility satisfaction. |

| 9 | Sun, GS; Tang, XR; Wan, SP; Feng, J [42] | An Extended Fuzzy-DEMATEL System | The paper, a fuzzy decision-making and trial evaluation laboratory (fuzzy-DEMATEL) technique, is extended, and a more suitable system is developed for the selection of social capital using the existing group decision-making theory. |

| 10 | Yang, XE; Liu, SL; Ji, WJ; etc. [43] | Questionnaires | The results showed that residents were willing to accept basic renovation measures but had low willingness to accept the quality improvement and renewable energy measures. |

| 11 | Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. [44] | MIP DEA–DA Model | The imbalance of interests among participants is a long-standing contradiction since the renovation process of old neighbourhoods involves participants from different levels and industries, and their interests vary, creating an imbalance of interests. |

| 12 | K. Lovejoy [45] | Factor analysis and logit modelling | Neighbourhood safety and the appearance of settlements are important, while vitality and diversity are important for downtown residents. |

| 13 | Roshanak Mehdipanah etc. [46] | CM, a mixed-methods methodology, | The scholars used CM, a mixed-methods methodology, to develop a conceptual map of perceptions of residents affected by recent physical, social, and economic changes that had occurred within their neighbourhoods. |

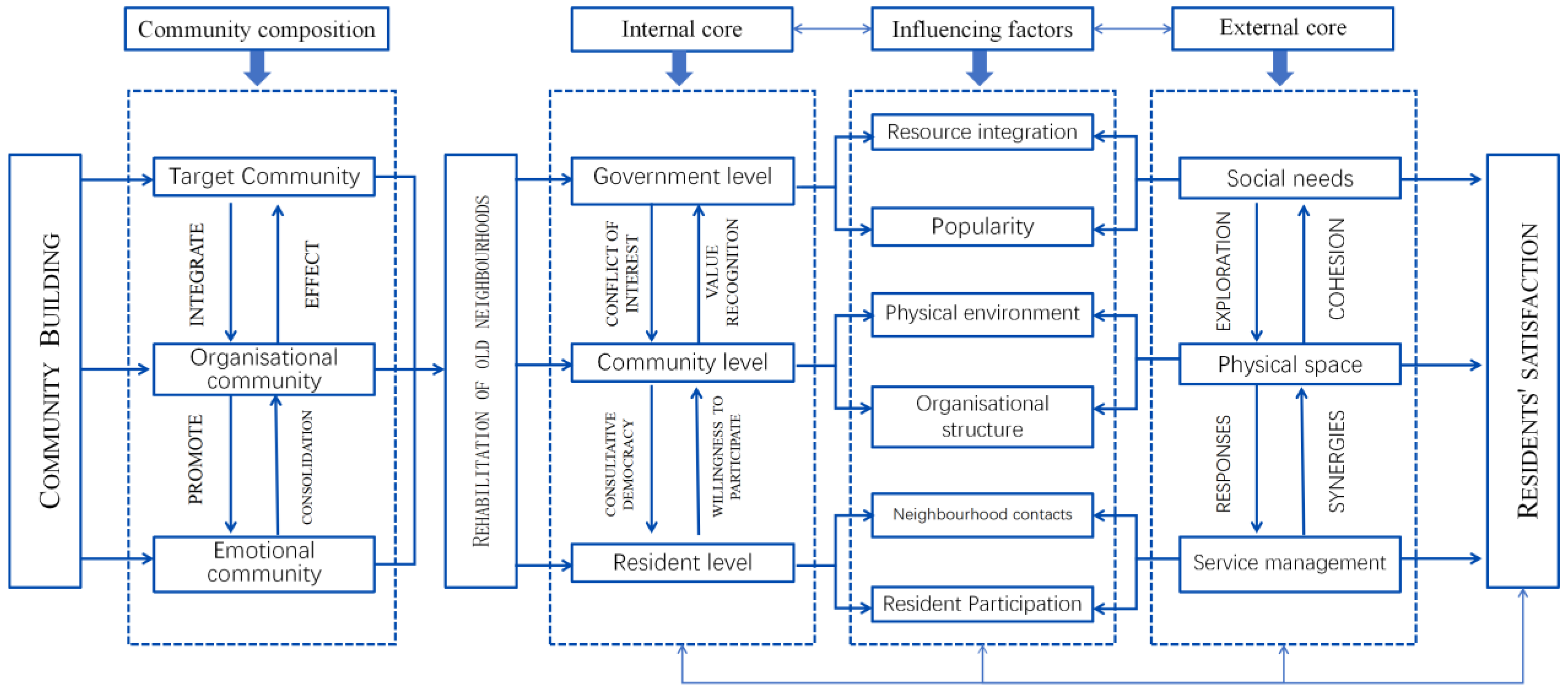

2.2. Research Logic

3. Materials and Methods

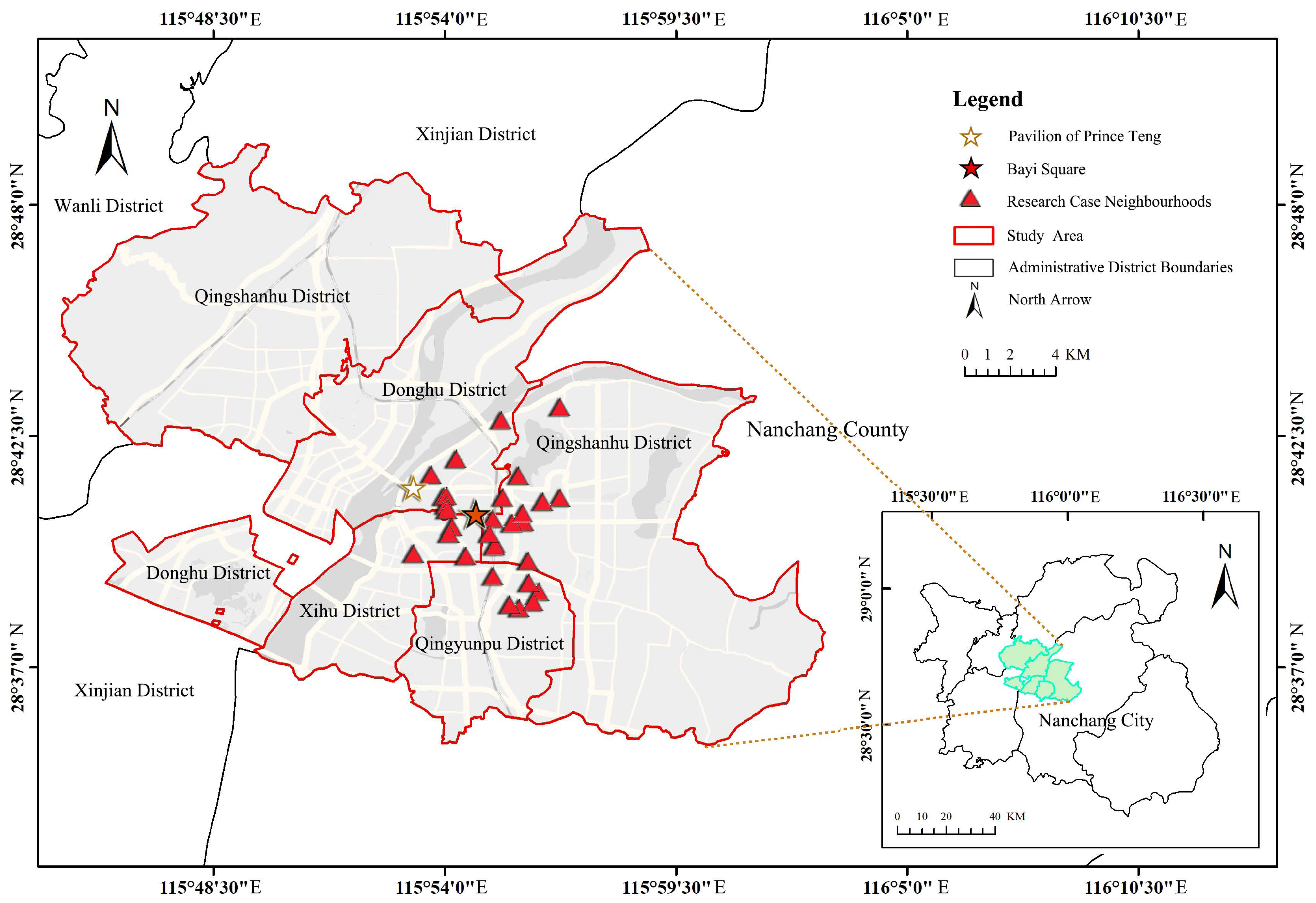

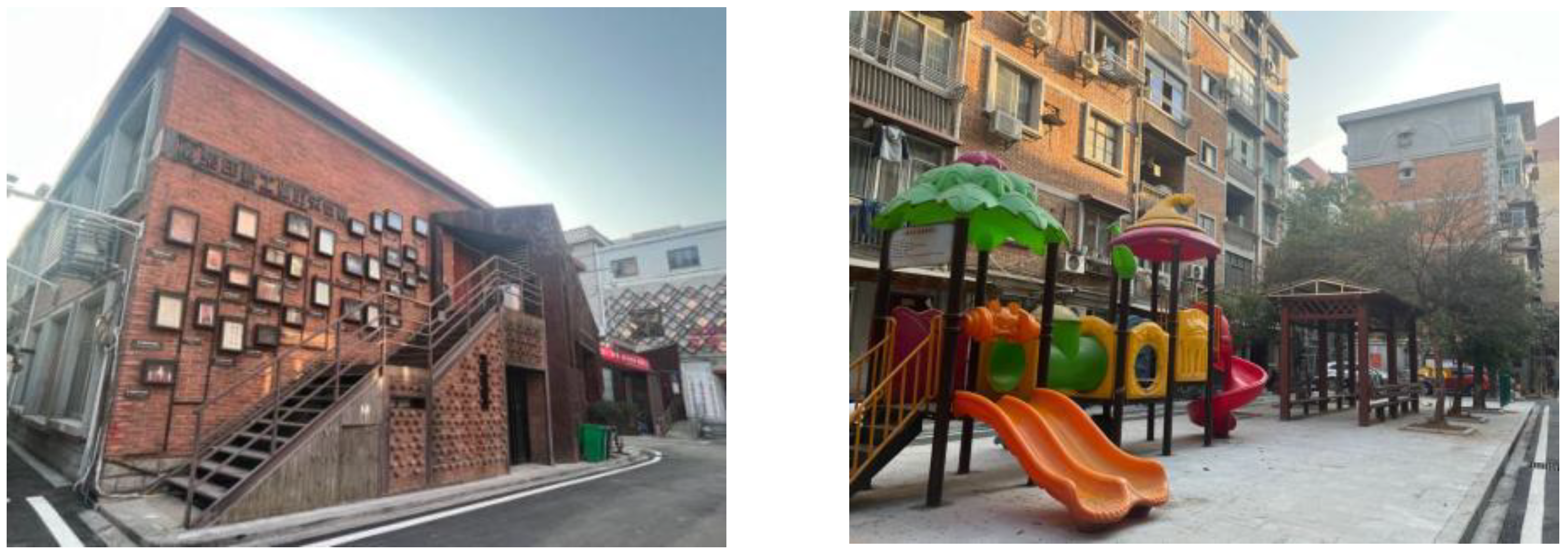

3.1. Study Area and Study Data

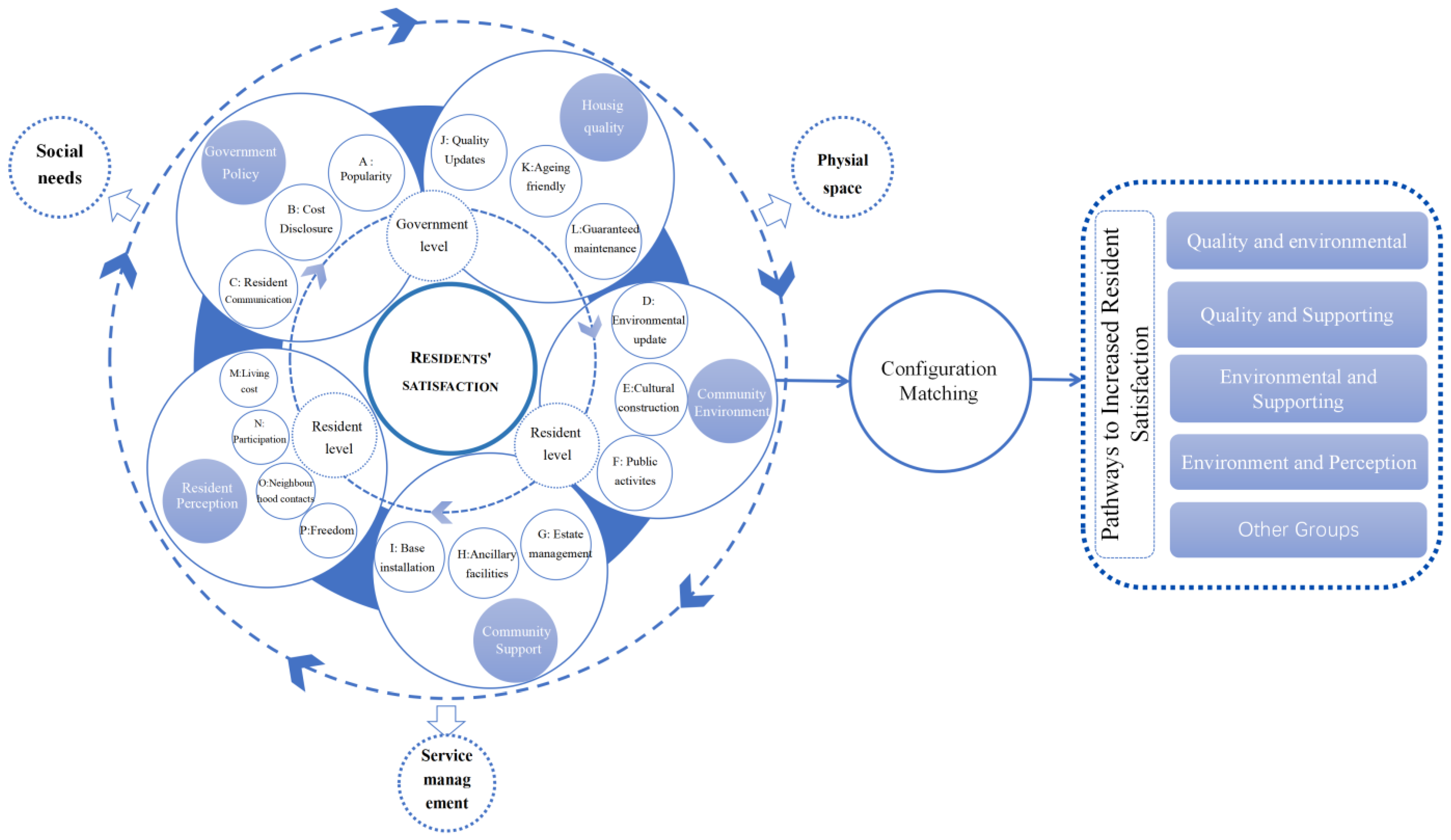

3.2. Research Methods, Model Construction, and Variable Selection

3.2.1. Research Methods

3.2.1.1. FsQCA Method

3.2.1.2. Reliability Analysis

3.2.1.3. Validity Analysis

3.2.2. Model Construction

- (1)

- Outcome l Variable

- (2)

- Conditional Variable

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Survey Results

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

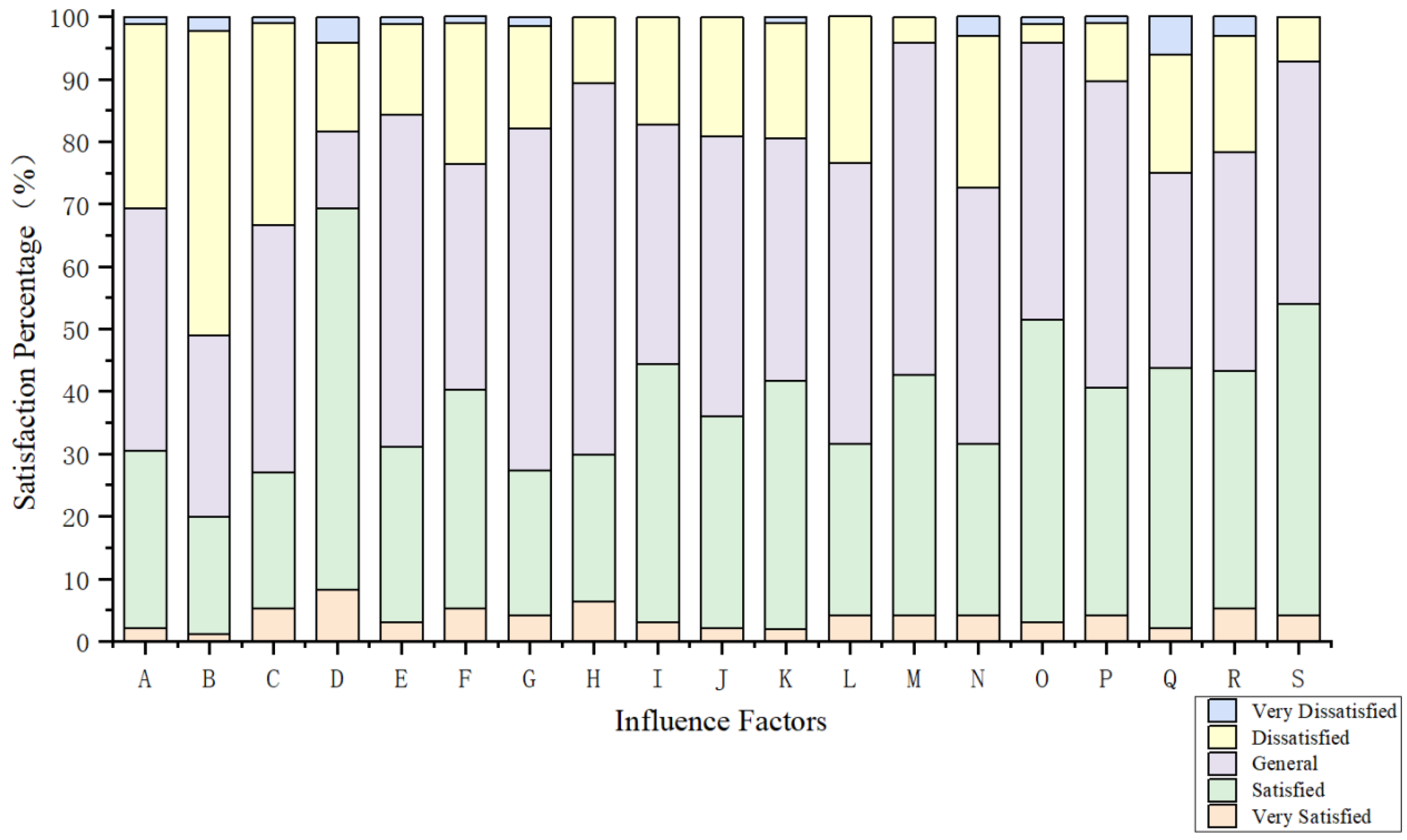

4.1.2. Satisfaction Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Fuzzy Sets

4.2.1. Calibration and Necessity Analysis

4.2.2. Conditional Grouping Sufficiency Analysis

4.2.3. Grouping Analysis

4.2.4. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Residents’ satisfaction with the renovation programme varied significantly: satisfaction with community human settlement renovation was the highest (69.4%), while satisfaction with the government’s cost disclosure was the lowest (20%).

- (2)

- Resident satisfaction is influenced by multiple factors, and no single factor alone can ensure high satisfaction. The analysis showed that no single condition variable (e.g., government policies, community environment, community support, housing quality, or residents’ perception) was sufficient to achieve high satisfaction, as the consistency of all variables was below 0.9. Instead, the interaction of these factors must be considered, as individual variables have limited explanatory power.

- (3)

- To achieve high resident satisfaction, four configurations are possible: housing quality enhancement, quality and support improvement, community environment improvement, and environment–quality linkage. Government policies and housing quality appear in three of these paths, highlighting their significant role in old neighbourhood renovation. However, policies must be combined with other factors (e.g., community environment or resident perceptions) to effectively enhance satisfaction, as they cannot achieve this alone.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

5.3. Shortcomings and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balsas, C.J. Historical and conceptual perspectives on urban regeneration: A prolog to a special issue. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2022, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Y.; Wang, C.; Lin, L. Organic Regeneration-Oriented Renovation of old Residential Areas: A Study on the Compilation of Technical Guide for the Renovation of Old Residential Areas in Jiangsu. City Plan. Rev. 2022, 46, 108–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Comprehensively Promoting the Renovation of Old Urban Neighbourhoods; National Defense Office [2020] No.23; The State Council The People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2020/content_5532614.htm (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and Other Departments Issue Circular on Solidly Promoting the Rehabilitation of Old Urban Neighbourhoods by 2023; Department of Urban Construction: Jeonju, The Republic of Korea, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202307/content_6892957.htm (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Gong, Q. Influencing Factors of Residents’ Satisfaction in Old neighbourhood Renovation Based on ACSI Model—Taking Xi’an City as an Example. Econ. Res. Guide 2023, 150, 68–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J. Impact of Perceived Value and Community Attachment on Smart Renovation Participation Willingness for Sustainable Development of Old Urban Communities in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Yao, X.; Wen, F. The Urban Regeneration Engine Model: An analytical framework and case study of the renewal of old communities. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105571. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wei, W.; Ferreira, F. How to Make Urban Renewal Sustainable? Pathway Analysis Based On Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis(fsQCA). Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2023, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Erfani, G.; Roe, M. Institutional stakeholder participation in urban redevelopment in Tehran: An evaluation of decisions and actions. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104367. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Chang, J. Imitation, Reference, and Exploration-Development Path to Urban Renewal in China (1985–2017). J. Urban Hist. 2020, 46, 728–746. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, B. Green transformation of old urban neighbourhoods-A new way to increase China’s effective investment. Urban Dev. Res. 2016, 23, 150–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nematchoua, M.K.; Orosa, J.A.; Reiter, S. Life cycle assessment of two sustainable and old neighbourhoods affected by climate change in one city in Belgium: A review. Elsevier Bv. 2019, 78, 106282. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R. Influencing Factors of Residents’ Satisfaction in Urban Village Rehabilitation. Urban Probl. 2017, 7, 35–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, L. Performance Measurement System for Assessing Transportation Sustainability and Community Livability. Trasp. Res. Record 2015, 2531, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, D. “Micro-transformation”: The Renewal Method of Old Urban Community. Urban Dev. Stud. 2017, 24, 29–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S. The Path of Transforming Older neighbourhoods from a Community Community Perspective. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2020, 17, 4–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Li, J. Research on the modern governance system of resilient communities promoted by “linkage of five social organisations” from the perspective of the community. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 30, 286–300. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Fang, D. Exploring Public Space Satisfaction in Old Residential Areas Based on Impact-Asymmetry Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, J. Assessment of Environmental Demands of Age-Friendly Communities from Perspectives of Different Residential Groups: A Case of Wuhan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Sonvisen, S.; Casado-Mansilla, D.; Mikalsen, M.; Cimmino, A.; Drosou, A.; Hussain, S. Towards smart, digitalised rural regions and communities-Policies, best practices and case studies. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Guan, Y. Construction of Old Community Transformation and Improvement and Evaluation Indicator System under the Concept of Future Community Chinese Journal of Gerontology. Urban Dev. Stud. 2024, 31, 134–140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, J.; Gao, S.; Liu, X. Exploring the Renovation Status and Flexible Strategies of Urban Housing in China Based on Two Surveys of Residents and Architects. Buildings 2022, 12, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Y.J. Study on the Relationship Between Community Sense of Belonging and Environmental Satisfaction of the Elderly. Urban. Archit. 2019, 16, 67–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, X. Assessing the adaptability of old community for renovation based on health sustainability. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. -Eng. Sustain. 2023, 176, 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Turcu, C. Local experiences of urban sustainability: Researching Housing Market Renewal interventions in three English neighbourhoods. Prog. Plan 2012, 78, 101–150. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Lin, W. Residential satisfaction level and influencing factors of declining old town residents in Suzhou. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 159–170. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Conway, T.L.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F. The Relation of Perceived and Objective Environment Attributes to Neighborhood Satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2017, 4, 36–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, F.; Ding, M.; Sun, P. Resident Satisfaction-based Updating Strategies of Old Communities: A Case Study of Harbin Demonstration Communities. Areal Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 75–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hur, M.; Nasar, J.L.; Chun, B. Neighborhood Satisfaction, Physical and Perceived Naturalness and Openness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Y. Exploration of Resident Satisfaction and Willingness in the Renovation of a Typical Old Neighborhood. Buildings 2025, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchecker, M.; Frick, J. The Implications of Urbanization for Inhabitants’ Relationship to Their Residential Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannscott, L. Individual and contextual socioeconomic status and community satisfaction. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 727–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Luan, J. Influencing factors and multiple realization paths of farmers’ satisfaction with the improvement of rural living environment: Based on FSQCA method. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2022, 43, 231–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, F.; Qin, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, H. Effects of Community ICT Usage on Community Satisfaction: Case Study in Nanjing, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 834–847. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Han, Q.; Liu, Y. Research on Influencing Factors of Resident’s Satisfaction Based on Transformation of Old Residential Areas: Taking Gujiazi Community in Shenyang as an example. J. Shenyang Jianzhu Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 25, 38–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, T.; Lou, Y.Q. Configuration paths of community cafe to enhance residents’ well -being: FSQCA analysis of 20 cases in Shanghai, China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1147126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Yuan, B. Research on the Evaluation of Residents’ Satisfaction in the Renovation of Old Community—Analysis based on FAHP and machine learning. Price Theory Pract. 2023, 02, 71–74+201. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, B. Evaluation of Aging-Friendly Public Spaces in Old Urban Communities Based on IPA Method—A Case Study of Shouyi Community in Wuhan. Buildings 2024, 14, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jin, J.; Zhao, X. A Case Study of Renovation of Old Community in Hangzhou Based on Residents’ Satisfaction. Archit. Cult. 2020, 5, 119–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.; Pickett, A.C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S. Neighborhood physical environments, recreational wellbeing, and psychological health. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Jin, K. A Study on Residential Satisfaction in the Urban Regeneration Region of middle Sized Cities-Focused on Jeon-ju Urban Regeneration Test Bed. J. Resid. Environ. Inst. Korea 2018, 16, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Tang, X.; Wan, S.; Feng, J. An Extended Fuzzy-DEMATEL System for Factor Analyses on Social Capital Selection in the Renovation of Old Residential Communities. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 134, 1041–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Q.; Mahroo, E.; Shen, Y.; Yang, L.; Han, X. Issues and challenges of implementing comprehensive renovation at aged communities: A case study of residents’ survey. Energy Build. 2021, 249, 111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, S. Decision-making conflict measurement of old neighbourhoods renovation based on Mixed Integer Programming DEA-Discriminant Analysis (MIP DEA–DA) Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, K.; Handy, S.; MokhtaRian, P. Neighborhood Satisfaction in Suburban versus Traditional Environments: An Evaluation of Contributing Characteristics in Eight California neighbourhoods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Malmusi, D.; Muntaner, C. An evaluation of an urban renewal program and its effects on neighborhood resident’s overall wellbeing using concept mapping. Health Place 2013, 23, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinand, T. Community and Society: Basic Concepts in Pure Sociology; Zhang, W., Translator; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2020; ISBN 978-7-100-18089-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Study on the Historical Formotation of Marx’s Community Thought. Ph.D. Thesis, (In Chinese). University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J. Holding High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Unitedly Striving for the Comprehensive Construction of a Modern Socialist Country: Report at the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. People’s Daily. Available online: https://www.ylq.gov.cn/info/content.jsp?info_id=111145&tm_id=96 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Jiang, L. Acceleration of Transformation of Old Residential Areas in Cities and Towns: Co-construction and Co-governance to Promote People-oriented Urbanization. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 34, 8–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Zheng, L. Socio-spatial differentiation and its evolution in Nanchang, 2000–2010. China Mark. 2015, 16, 160–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Announcement on Soliciting Suggestions for Nanchang Territorial Spatial Master Plan (2021–2035) (Public Draft); Nanchang Natural Resources and Planning Bureau: Nanchang, China, 17 November 2022. Available online: http://bnr.nc.gov.cn/ncszrzyj/xwdt/202210/b44f4e9e86ac4a0695a091b8e6fd5a20.shtml (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Du, Y.; Jia, L. Group Perspective and Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): A New Path for Management Research. J. Manag. World 2017, 06, 155–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, S.; Tavares, P.; Queiró, R. Perceived service quality and customer satisfaction: A fuzzy set QCA approach in the railway sector. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, J.M.; Korjani, M.M. Theoretical aspects of Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). Inf. Sci. 2013, 237, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yu, G. Study on the Influencing Factors of Residents’ Satisfaction in the Old Urban Renewal Based on Pearson Correlation Degree. J. Beijing Univ. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2020, 36, 18–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wen, B.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, Y. Study on the Influencing Factors of Community Residents’ Participation in the Reconstruction of Old Community: Based on the Empirical Observation of the Reconstruction of the Old Community. Urban Dev. Stud. 2021, 28, 29–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District–Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Van Dijk, H.M.; Nieboer, A.P. The Importance of neighbourhood Social Cohesion and Social Capital for the Well Being of Older Adults in the Community. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B: Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yang, W.; Cai, W.G. Study on Constraints of Urban Renewal in Old Industrial Areas Based on Explanatory Structural Modeling—Taking Chongqing Municipality as an Example. Product. Res. 2019, 09, 87–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, R.; Kearns, A. Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castro, R.; Francoeur, C. When more is not better: Complementarities, Costs and Contingencies in Stakeholder Management. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 37, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. SAGE Publ. 2009, 15, 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, P.; Joshi, A.; Misangyi, V.F. Gender-Inclusive Gatekeeping: How (mostly male) Predecessors Influence the Success of Female CEOs. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Fiss, P.C.; Sawy, O.A. Theorizing the multiplicity of digital phenomena: The ecology of configurations, causal recipes, and guidelines for applying QCA. Mis Q. 2020, 44, 1493–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Kim, P.H. One size does not fit all: Strategy configurations, complex environments, and new venture performance in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Greckhamer, T.; Gur, F.A. Disentangling combinations and contingencies of generic strategies: A set theoretic configurational approach. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 101951. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Crilly, D.; Greckhamer, T. Stakeholder engagement strategies, national institutions, and firm performance: A configurational perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 1869–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Greckhamer, T. CEO compensation in relation to worker compensation across countries: The configurational impact of country-level institutions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 793–815. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Community | NO | Construction | Nature of Housing | Type of Modification | Retrofitting Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qingshan Lake district | Castle Peak Lake Neighborhood | S1 | 1986 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2022 | |

| Nankai residential area | S2 | 1958–2000 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Riyuemei Subdivision | S3 | 1996 | commercial property | Upgrading Renovation | 2021 | ||

| East Fork Road Neighbourhood | S4 | 1970s | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2020 | ||

| Commercial Court Neighbourhood- Transport Design Institute Quarters | S5 | 1982 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Railway Village 6 | S6 | 1990s | housing reform | Improvement Renovation | 2022 | ||

| Glass Factory Dormitory Subdivision | S7 | 1985–1998 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Jiangfang 7th District | S8 | 1958 | housing reform | Upgrading Renovation | 2022 | ||

| Donghu district | Fire Temple Neighbourhood | S9 | 1992 | housing reform/commercial property | Improvement Renovation | 2021 | |

| Zhuangyuanqiao Neighbourhood | S10 | 1991 | housing reform/commercial property | Improvement Renovation | 2020 | ||

| Park Neighbourhood Area | S11 | 1985 | housing reform/commercial property | Basic Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Qiujia factory Neighbourhood | S12 | 1990s | housing reform/commercial property | Improvement Renovation | 2021 | ||

| River Slim Metropolis Subdivision | S13 | 1993 | housing reform | Enhancements | 2019 | ||

| Zhujiahu Neighbourhood | S14 | 2002 | commercial property | Upgrading Renovation | 2023 | ||

| Zigu Road Neighbourhood | S15 | Prior to 2000 | housing reform, commercial property | Upgrading Renovation | 2022 | ||

| West lake district | Railway Second Village | S16 | 1985 | housing reform | Upgrading Renovation | 2020 | |

| Xingchai Beiyuan Neighbourhood | S17 | 1980 | Converted public housing blocks | Basic Renovation | 2017 | ||

| Fukuda Neighbourhood | S18 | 1998 | dormitory | Improvement Renovation | 2020 | ||

| Zhu Zi Xiang District | S19 | 1991 | commercial property | Improvement Renovation | 2018 | ||

| Dongshuyuan Neighbourhood | S20 | 1980 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2019 | ||

| Taoyuan Neighbourhood Area 2 | S21 | 1993 | commercial property | Improvement Renovation | 2018 | ||

| Brewery Dormitory | S22 | 1985 | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2022 | ||

| Jinxiancang District | S23 | 1998 | housing reform | Upgrading Renovation | 2022 | ||

| Qingyunpu district | Hongdu Living Quarter | Hongyuan Neighbourhood | S24 | 1950s | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2019 |

| Hongke Neighbourhood | S25 | 1950s | housing reform | Basic Renovation | 2020 | ||

| Hong Dong Neighbourhood | S26 | Prior to 1996 | housing reform | Upgrading Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Hong Xiang Neighbourhood | S27 | Prior to 2000 | housing reform, dormitory | Upgrading Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Hongcheng Road Neighbourhood | S28 | 1993 | housing reform | Improvement Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Aurora Neighbourhood | S29 | 1995 | housing reform | Improvement Renovation | 2020 | ||

| Kam Luen Neighbourhood | S30 | 1990s | housing reform | Improvement Renovation | 2021 | ||

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Title Description | Cited Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional variable | Government Policy | A: Satisfaction with the popularity of the policy implementation approach | Li Qin et al. [56] |

| B: Degree of satisfaction with the disclosure of details of government remodelling costs | Gao Hui et al. [39] | ||

| C: Degree of satisfaction with the Government’s timely communication with residents on issues throughout the transformation process | Zhang Jiali et al. [57] | ||

| Community Environment | D: Degree of satisfaction with neighbourhood human settlements renewal, e.g., increased greening, improved sanitation | Li Qin et al. [56] | |

| E: Degree of satisfaction with the community’s efforts to build a culture of self-governance, e.g., activities to honour the elderly, New Year’s Day activities, etc. | Esther Hiu Kwan Yung et al. [58] | ||

| F: Degree of satisfaction with the increase or improvement of public activity spaces in the community, e.g., chess rooms, elderly activity centres, etc. | Jiang ling et al. [50] | ||

| Community Support | G: Satisfaction with changes in property management, e.g., changes in property rates, smart property applications | Lv fei et al. [28] | |

| H: Satisfaction with changes in community amenities, e.g., increased community commerce, community healthcare, etc. | Lv fei et al. [28] | ||

| I: Satisfaction with changes in community infrastructure, e.g., grading of roads, planning of car parks, etc. | Zhang Jiali et al. [57] | ||

| Housing Quality | J: Degree of satisfaction with the updating of housing functions and quality, such as the updating of facades along the street and other aspects, and measures such as plumbing repairs in kitchens and bathrooms | Li Qin et al. [56] | |

| K: Degree of satisfaction with the suitability of adapted housing for the elderly | Cramm, J. M. et al. [59] | ||

| L: Satisfaction with guaranteeing the quality of the construction of the remodelling part of the work and carrying out the subsequent repairs in a timely manner | Gao Hui et al. [39] | ||

| Resident Perception | M: Satisfaction with change in cost of living after modification | Feng jian et al. [26] | |

| N: Satisfaction level of residents’ participation in the selection of updated content | Esther Hiu Kwan Yung et al. [58] | ||

| O: Satisfaction with changes in neighbourhood interactions and exchanges | Bramley, Glen [60] | ||

| P: Satisfaction with changes in freedom of living before and after remodelling | Lv fei et al. [28] | ||

| Outcome variable | Residents’ Satisfaction | Q: Overall satisfaction with the impact of the construction process on daily life | Zhang Jiali et al. [57] |

| R: Whether the transformation meets residents’ expectations | Zhou tao et al. [61] | ||

| S: Overall satisfaction with changes in sense of belonging to the community after transformation | Forrest R et al. [62] |

| KMO Sample Suitability Quantity | 0.796 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate chi-square | 852.413 |

| Degrees of freedom | 190 | |

| Significance | 0.000 | |

| Conditional Variable | Residents’ Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Degree of Coverage | |

| Government Policy | 0.783 | 0.739 |

| ~Government Policy | 0.302 | 0.327 |

| Community Environment | 0.701 | 0.705 |

| ~Community Environment | 0.388 | 0.392 |

| Community Complementary | 0.715 | 0.649 |

| ~Community Complementary | 0.370 | 0.418 |

| Housing Quality | 0.823 | 0.757 |

| ~Housing Quality | 0.258 | 0.287 |

| Resident Perception | 0.690 | 0.738 |

| ~Resident Perception | 0.412 | 0.392 |

| Variable Name | The Full Affiliation Point | The Intersection Point | The Completely Unaffiliated Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residents’ satisfaction | 3.000 | 2.670 | 2.165 |

| Government policy | 3.670 | 3.000 | 2.330 |

| Community Environment | 3.000 | 2.667 | 2.000 |

| community support | 3.000 | 2.333 | 2.000 |

| Housing quality | 3.333 | 2.667 | 2.333 |

| Resident perception | 3.000 | 2.750 | 2.250 |

| Conditional Variable | High Level of Resident Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |

| Government Policy | ||||

| Community Environment | ||||

| Community Complementary | ||||

| Housing Quality | ||||

| Resident Perception | ||||

| Consistency | 0.8683 | 0.8661 | 0.8279 | 0.841 |

| Original Coverage | 0.5203 | 0.1297 | 0.3652 | 0.1178 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.1048 | 0.0066 | 0.0174 | 0.0501 |

| Overall Consistency | 0.8357 | |||

| Overall coverage | 0.5953 | |||

| Conditional Variable | Residents’ Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| Government Policy | |||

| Community Environment | |||

| Community Complementary | |||

| Housing Quality | |||

| Resident Perception | |||

| Consistency | 0.8683 | 0.8279 | 0.8413 |

| Original Coverage | 0.5203 | 0.3652 | 0.1178 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.1725 | 0.0174 | 0.0511 |

| Overall Consistency | 0.8419 | ||

| Overall coverage | 0.5887 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, H.; Wang, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, P.; Zheng, K. Factors and Pathways to Enhance Resident Satisfaction in Old Residential Neighbourhood Renovation: A Configuration Analysis of Cases in Central Nanchang, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071125

He H, Wang H, Zheng L, Zhao T, Zhang P, Zheng K. Factors and Pathways to Enhance Resident Satisfaction in Old Residential Neighbourhood Renovation: A Configuration Analysis of Cases in Central Nanchang, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071125

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Haifang, Hongrui Wang, Lin Zheng, Tengfei Zhao, Puwei Zhang, and Kan Zheng. 2025. "Factors and Pathways to Enhance Resident Satisfaction in Old Residential Neighbourhood Renovation: A Configuration Analysis of Cases in Central Nanchang, China" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071125

APA StyleHe, H., Wang, H., Zheng, L., Zhao, T., Zhang, P., & Zheng, K. (2025). Factors and Pathways to Enhance Resident Satisfaction in Old Residential Neighbourhood Renovation: A Configuration Analysis of Cases in Central Nanchang, China. Buildings, 15(7), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071125