1. Introduction

The structure of old Arabian cities and their physical layout reflect a strong emphasis on social cohesion and connection, with quarters, neighbourhoods, and communities collectively forming their urban fabric. These cities evolved organically, responding to unique historical events, such as wars, migrations, and economic transformations, contributing to their spatial flexibility and long-term resilience [

1]. Unlike modern planning paradigms that rigidly divide cities into arranged zones, old Arabian cities exhibited integrated and permeable urban layouts that encouraged interaction and inclusivity. Despite various studies on traditional Arabian urbanism and modern gated communities, a gap remains in linking historical spatial practices with contemporary urban forms [

2]. This study addresses this gap by examining how historical principles of privacy, security, and spatial hierarchy have been reinterpreted in modern gated communities.

Abed, et al. [

3] note that discussions on sustainability often focus on environmental and economic aspects, while social dimensions, such as community integration, livability, and accessibility, remain underexplored. Social sustainability ensures that urban development supports affordable housing, well-planned neighbourhoods, and inclusive social engagement [

4]. Bramley, et al. [

5] define social sustainability as enhancing well-being and reducing fear by reinforcing relationships in shared spaces [

6]. However, the spread of gated communities in the Middle East raises critical questions: Do they recreate the sociospatial cohesion of historic urban forms, or do they exacerbate segregation by restricting access and interaction?

Despite regional variations in urban patterns, Arabian cities share a common morphological and spatial identity due to their shared social, climatic, religious, and geographic factors [

7]. Settlement patterns were heavily influenced by the availability of natural resources, trade routes, and religious significance, with religion performing a central role in structuring urban life and spatial organisation. The influence of daily life extended beyond architectural styles to include shared cultural practices, such as community gatherings centred around daily prayers. These practices enhanced communal engagement and contributed to economic activity, as markets often surrounded mosques [

8]. To balance privacy and collective belonging, urban structures featured inward-facing houses, central courtyards, and narrow alleyways, elements which will be critically examined later in this study for their relevance to modern gated communities [

9]. Historically, enclosed neighbourhoods enhanced both security and social interaction within internal networks. For example, Basra, built in 660 AD, featured early gated architecture designed for protection and social organisation. Similar layouts influenced cities like Baghdad and Fustat, with traces of these structures persisting today [

10]. However, historical walled cities regulated access while maintaining urban permeability, whereas modern gated communities prioritise exclusivity over connectivity. This contrast raises essential questions about their social sustainability: Do they foster self-sufficient, cohesive environments or contribute to urban discontinuity and socioeconomic segregation?

This study conducts a historical inquiry into Arabian gated neighbourhoods to extract attributes related to social cohesion and integration. By analysing the evolution of enclosure, gating, and spatial separation, it assesses whether modern gated communities represent a continuation, reinterpretation, or departure from historical models [

11].

2. Literature Review

Historical Arabian cities were profoundly influenced by religious life and social institutions, which served as key nodes embedded in the urban fabric, shaping the spatial configuration and defining their architectural identity [

8]. Gates and walls historically demarcated the urban landscape in Arabian cities, similar to other cultures, such as in China, where spatial enclosures represent security, order, and governance [

12]. The prevalence of such gated urban forms in pre-modern cities was a universal phenomenon, symbolising security, order, and social hierarchy [

13]. The historical pattern suggests that enclosed urban settlements were not unique to Arabian cities but rather a widespread urban response to security and social arrangement. Li and Xie [

14] argue that early Chinese neighbourhoods were often enclosed by boundaries, suggesting a historical precedent for the gated community concept. Similarly, Huang [

15] highlights that modern gated communities in China could be seen as an evolution of these enclosed urban colonies, which are rooted in long-standing cultural and spatial traditions. These historical features have evolved into controlled residential environments that regulate access based on social and economic factors, raising questions about continuity and transformation in urban design.

The theory of urban morphology, as suggested by Kropf [

16], provides a framework for understanding how historical spatial forms persist or transform in contemporary developments. This theoretical perspective enables a comparative analysis of the organic street patterns of old Arabian cities and the rigid spatial segregation of modern gated communities. From a social sustainability perspective, examining historical urban enclosures helps understand whether these spatial patterns contribute to long-term community resilience or reinforce exclusionary practices in modern contexts. By tracing the evolution from traditional to contemporary urban forms, this study seeks to uncover the sociospatial implications of these transformations [

17].

2.1. Physical Characteristics

In Arabian cities, houses were historically protected by walls and gates that served as physical barriers for social regulation, establishing a structured transition between public and private spaces [

8]. This spatial configuration ensured a balance between security and accessibility, fostering both privacy and community interaction. Traditional enclosed settlements allowed for permeability through semi-private streets and shared spaces, fostering interaction among residents. For example, the narrow, winding streets of historic Cairo or the Fez exemplify how traditional urban design integrated public and private realms. However, modern gated communities adopt rigid spatial enclosures that strictly regulate access, reinforcing exclusivity. These physical transformations mark a transition from historical urban models, where enclosures were integral to organic city growth, to contemporary layouts dictated by private development interests. Gated communities often feature controlled entry points, private amenities, and internal governance systems that differentiate them from traditional neighbourhoods. Unlike the organically integrated fabric of historic Arabian cities, where commercial, residential, and religious spaces coexisted, modern gated developments create defined internal zones with minimal interaction with surrounding urban environments [

18].

2.2. Economic Aspect

Economic factors play a crucial role in influencing the development and expansion of gated communities. Historically, enclosed urban settlements evolved due to communal needs for protection and resource management rather than economic exclusivity [

19]. In contrast, contemporary gated communities are largely market-driven developments that cater to specific income groups, reinforcing socioeconomic stratification [

20]. For example, in the Gulf cities, the proliferation of gated communities is closely tied to real estate speculation and foreign investment, creating enclaves for high-income residents [

21].

Studies highlight how privatisation and real estate speculation influence the proliferation of gated communities, particularly in Middle Eastern cities [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Unlike historical enclosures, which facilitated organic social structures, modern gated developments operate as exclusive, commodified spaces that cater to high-income residents, often at the expense of broader urban accessibility [

26]. The financial models behind these communities prioritise return on investment, influencing the spatial and infrastructural layout of developments. This economic exclusivity challenges social sustainability by limiting affordability and inclusivity in urban housing markets. For instance, the emphasis on luxury amenities and security features in gated communities often excludes middle- and lower-income groups, exacerbating urban inequality [

27].

2.3. Social Aspects: Segregation vs. Integration

Gated communities have been widely debated for their impact on social sustainability. Some scholars argue that their enclosed nature fosters strong internal social bonds by bringing together residents of similar economic status and shared interests [

28,

29,

30]. Their physical designs, controlled access, shared amenities, and internal governance reinforce localised social cohesion, reflecting historical urban principles of community-centric planning. For example, residents of gated communities often report a sense of security and belonging, which can enhance their quality of life. Conversely, other scholars critique the exclusionary nature of gated communities, arguing that they reinforce sociospatial fragmentation by restricting access to public resources and limiting social interactions beyond their boundaries [

31,

32,

33]. Unlike historical Arabian cities, which integrated public, commercial, and residential spaces to foster inclusivity, modern gated communities prioritise exclusivity, often weakening urban connectivity and perpetuating socioeconomic segregation [

1,

18]. The separation of these developments from surrounding neighbourhoods creates physical and social barriers, limiting opportunities for broader urban integration.

Studies in Egypt [

22], Qatar [

23], and Bahrain [

24] examine how gated communities influence social interaction, livability, and public space accessibility. These studies suggest that modern gated developments in Arabian cities diverge from traditional enclosed quarters, as they emphasise exclusivity and privatisation rather than organic social cohesion. This transformation raises concerns about whether modern gating fosters inclusive urbanism or exacerbates segregation [

34,

35]. Sociospatial segregation theory further interprets how gated communities reinforce urban divisions by creating areas of economic homogeneity, limiting long-term urban integration [

36,

37]. Historically, Arabian cities managed social distinctions through organic urban growth, allowing different social and ethnic groups to live together while maintaining distinct quarters. However, gated communities introduced rigid spatial separations that encourage exclusivity rather than fostering social integration. Unceta, Hausleitner and Dąbrowski [

36] explain that traditional strategies for addressing urban segregation, such as land formalisation policies, often fail to mitigate sociospatial disparities. Instead, alternative urban planning solutions that acknowledge local spatial traditions may be more effective in balancing integration and exclusivity. This perspective challenges the reliance on Western planning models, which often disregard cultural urban forms [

7].

2.4. Cultural Aspect: Continuity and Transformation

Cultural traditions have historically influenced the spatial organisation of Arabian cities. Glasze [

18] identified two key reasons that contributed to social segregation in the Arab world: (a) the use of courtyards as an extension of private, sacred spaces, and (b) the defensive role of courtyards against intrusions, as explained by Abu-Lughod [

38]. Glasze [

18] further argues that contemporary gated communities in the Arab world, particularly in Saudi Arabia, represent a combination of traditional principles of privacy and sacredness with Western-inspired gated housing. However, Touman [

39] argues that gated communities in Saudi Arabia cannot be considered an urban solution, as they primarily cater to temporary elite residents and fail to address broader urban challenges. Similarly, Giddings, et al. [

40] argue that gated communities in the Gulf Corporation Council countries (GCC) are predominantly an imported concept from the United States, fundamentally contradicting regional housing traditions. Unlike traditional Arabian neighbourhoods, where communal spaces such as mosques and markets facilitated integration, modern gated communities often introduce artificial exclusivity by restricting access, reinforcing patterns of sociospatial division [

41]. This transformation from functional enclosures to market-driven and exclusive products raises critical questions about sociospatial continuity between historical and modern urban forms. While some elements of historical enclosure persist, the transformation from permeability to exclusivity advocates a departure from traditional urban inclusivity, potentially weakening communal bonds in the social fabric. Specifically, does the reinterpretation of traditional enclosed spaces within gated developments support cultural continuity, or does it undermine historical urban inclusivity?

Building on this discussion, Alkan Bala [

42] explored the similarities between gated communities and the traditional concept of cul-de-sac in Turkish urban culture. Using a comparative methodology and case studies, Bala examined the privatisation of public space and its implications for social fragmentation. The study highlights that traditional cul-de-sacs were extensions of communal life, whereas modern gated communities redefine them as a tool that exacerbates social segregation. However, while Bala’s study provides valuable insights into the spatial characteristics of gated communities, it does not explore the broader implications for community cohesion, social integration, and the impact of these design features on residents’ daily lives. This gap in the literature highlights the need for empirical research on how residents perceive and experience cultural continuity in gated communities, particularly in the Arabian context.

Urban morphology, as explored by Krier [

43], provides a critical examination of spatial evolution by recognising the historical heritage and past experiences of enclosed neighbourhoods. Tracing the transformation from historical Arabian quarters to modern gated communities allows for an in-depth understanding of urban continuity and discontinuity. Kropf [

16] further emphasises that historic mapping and spatial analysis are essential tools for understanding how past urban patterns influence contemporary city planning. By reconstructing abandoned heritage, urban designers can ensure continuity in urban identity while addressing contemporary sociospatial needs [

44]. This perspective is particularly relevant to the study of gated communities, as their spatial structures, access controls, and sociospatial hierarchies may reflect historical precedents or diverge due to social or economic factors.

While empirical data from resident interviews related to cultural identity in the Arab cities’ gated communities were not part of this study, existing theoretical and comparative studies offer valuable insights. For example, Elsheshtawy [

21] argues that rapid urbanisation in Gulf cities prioritises globalised architectural styles over local cultural heritage, weakening communal principles. This suggests that gated communities, while preserving privacy, often weaken cultural continuity by eroding the communal principles of traditional neighbourhoods. Similarly, Le Goix [

45] highlights that gated communities globally reinforce socioeconomic divisions, weakening social cohesion. In the Arabian context, the absence of communal spaces like mosques and markets limits social interaction related to traditional urban life [

21]. Furthermore, Bagaeen and Uduku [

46] emphasise that gated communities often cater to transnational elites, creating a disconnect from local cultural practices. While gated communities reinterpret traditional principles of privacy and enclosure, their emphasis on exclusivity often weakens the communal and inclusive nature of traditional urban spaces, weakening cultural continuity.

2.5. Conclusion and Gaps in the Literature

The evolution of residential enclosures in Middle Eastern cities, from traditional Arabian neighbourhoods to contemporary gated communities, raises fundamental questions about the influence of inherited spatial structures on privacy, accessibility, and social cohesion. Historically, Arabian neighbourhoods were structured around gradual transitions between public and private space, fostering both community interaction and controlled access. In contrast, modern gated communities introduce rigid physical boundaries that redefine the balance between privacy and communal life. This often results in new patterns of exclusion and urban fragmentation that contrast with historical urban inclusivity.

The historical analysis of gated neighbourhoods in old Arabian cities examines the relationship between culture and social life influenced by religious factors that influenced their organic patterns. The sociospatial fragmentation, associated with the notion of privacy and sacredness, is seen as the defining characteristic of these historical neighbourhoods, which aids in understanding their deep-rooted meanings. However, gaps exist in the literature on a deeper exploration of whether contemporary gated communities in the Middle East replicate or depart from these historical and social behaviours [

24]. While previous research has examined the sociospatial evolution of gated communities in the region [

18,

40], limited scholarly engagement exists in relation to the historical continuity between traditional Arabian neighbourhoods and modern enclosed communities. This study aims to address these gaps by exploring historical attributes, such as community cohesion, privacy, fragmentation, and organic fabric. Building on these diverse perspectives, this study seeks to assess how modern gated communities reinterpret or diverge from traditional urban principles.

3. Contextualising Historical Neighbourhoods

Historically, quarters have served as the core spatial unit of Arabian urbanism, functioning as self-contained residential zones influenced by sociocultural and religious values [

8,

47]. These quarters were typically inhabited by residents sharing similar ethnicities, professions, or social backgrounds, leading to cohesive yet spatially fragmented urban patterns [

48,

49]. Their organic development resulted in walled enclosures, narrow streets, and controlled access points, fostering strong internal social connections while limiting access to other parts of the city [

47]. In contrast to modern gated communities, which are explicitly designed for exclusivity, these traditional quarters evolved naturally as part of a broader, interconnected urban system.

This study examines historical urban patterns in cities such as Damascus, Aleppo, Tunis, Fes, Cairo, and Rabat, alongside modern gated communities like The Kingdom in Riyadh and Dar Al Salam in Qatar. By analysing the spatial characteristics of these historical and contemporary urban forms, the study highlights the sociospatial continuities and critical divergences between enclosed neighbourhoods of the past and present.

3.1. Historical Case Studies: Traditional Arabian Quarters

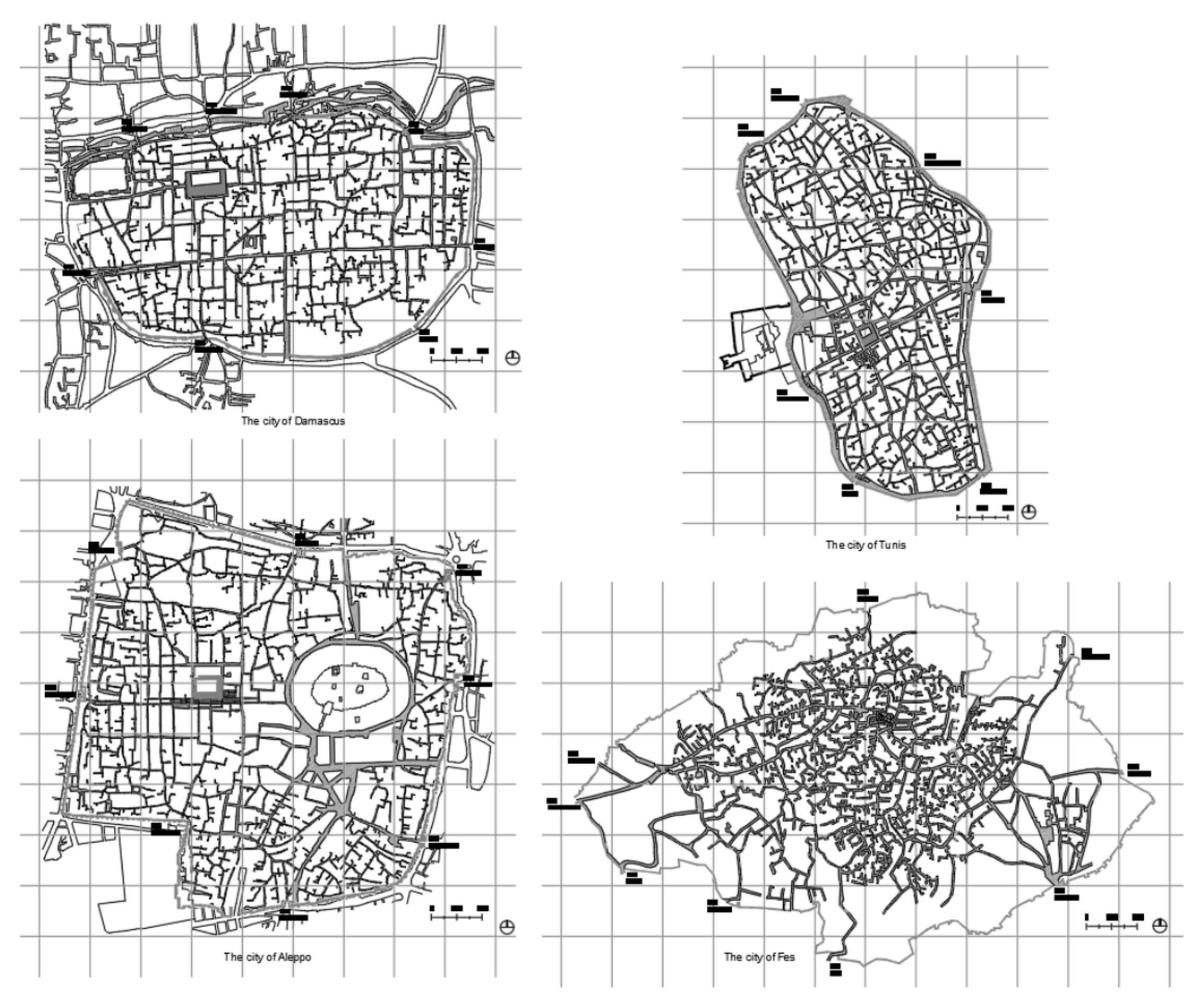

As shown in

Figure 1, maps of Damascus, Aleppo, Tunisia, and Fes illustrate irregular and organically developed street networks with varied spatial configurations based on topography, culture, and governance structures.

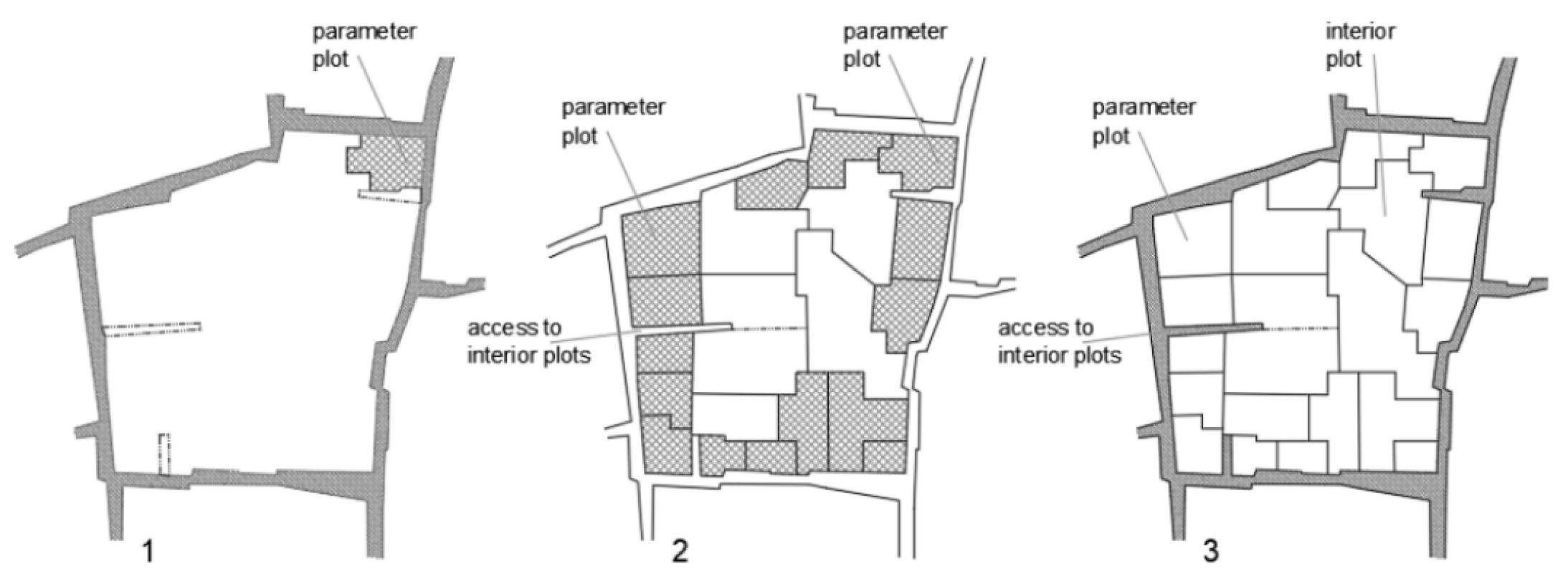

At the micro level, the concept of cul-de-sacs played a crucial role in structuring residential spaces, using dead-end streets to regulate access and define social interactions. These cul-de-sacs transitioned from public spaces into private areas, creating semi-private zones predominantly occupied by extended family members. This arrangement reinforced safety, privacy, and community cohesion, as illustrated in

Figure 2 [

42].

The hierarchal structure of traditional Arabian quarters offered several benefits, such as crime reduction, traffic control, and the formation of safe zones for children. While modern planning regulations may challenge such configurations, their effectiveness in enhancing community interaction supports the argument that certain historical urban principles remain relevant today. The transition from public to private zones through street hierarchies and cul-de-sacs supports the idea of modern gated communities by controlling public streets through gates to manage access and ensure security [

8,

50].

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the spatial integration of public spaces such as mosques and markets played a critical role in facilitating social engagement within historical quarters. This integration highlights the functional role of controlled access and cohesive spatial arrangements in enhancing safety and community interaction [

42,

47].

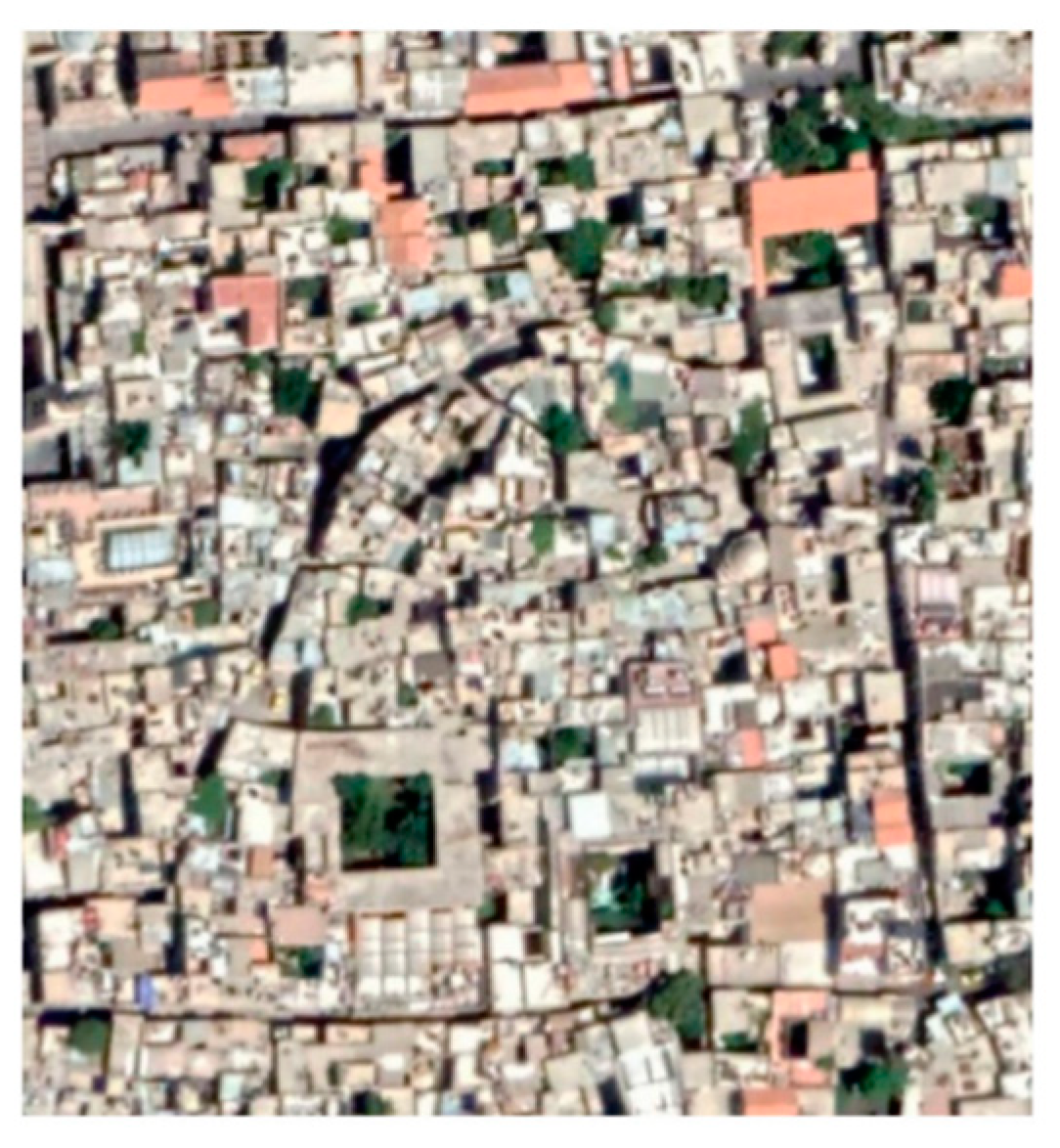

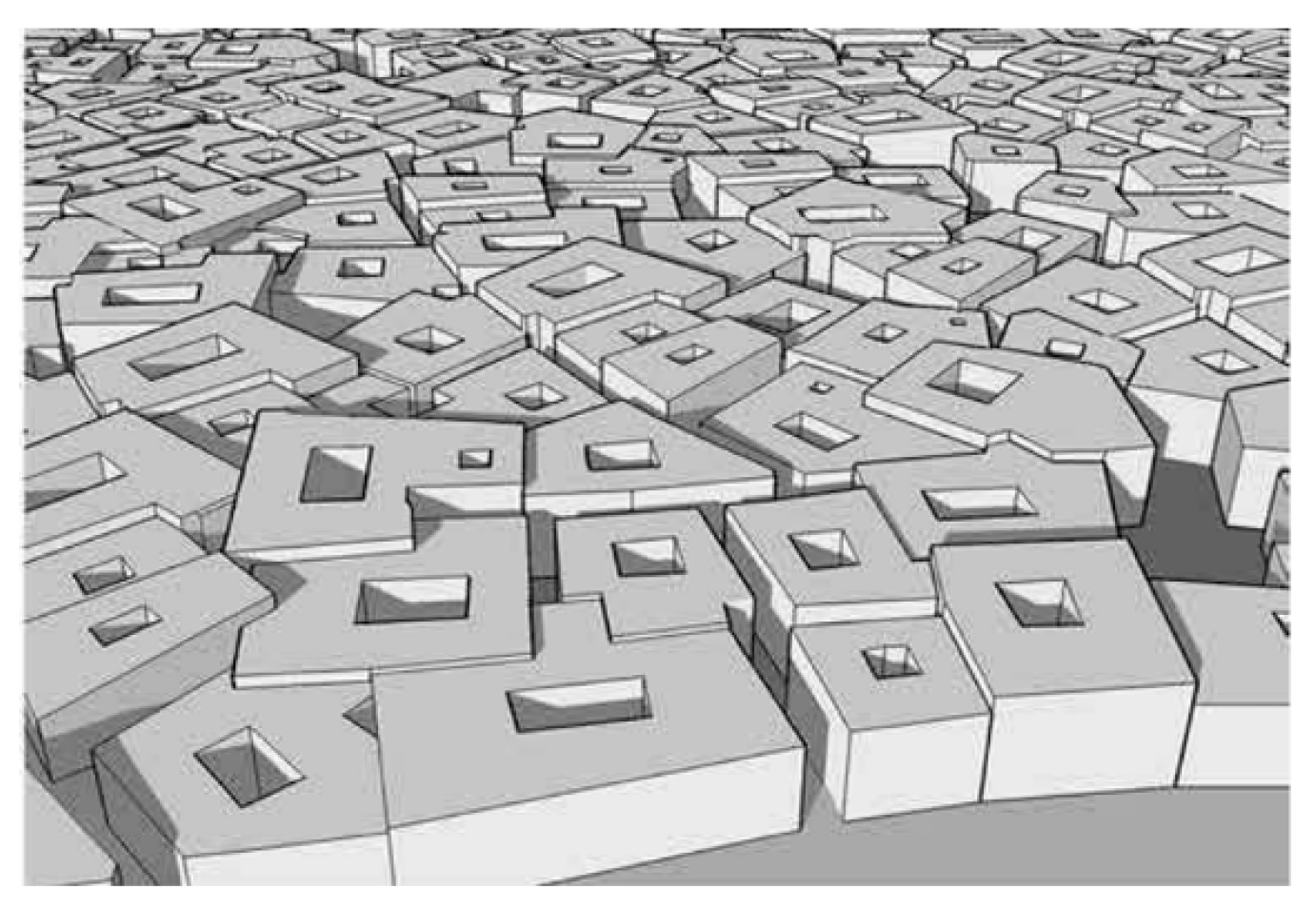

Furthermore, historical Arabian cities adapted to environmental, social, and religious factors by developing compact urban layouts [

51], walled perimeters, narrow streets, and shared courtyards. Their organic designs responded to climate conditions while prioritising human-scale interaction, privacy, and social functionality, as seen in Cairo, Rabat, and Damascus (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Tribal traditions and local governance further reinforced the self-sufficient nature of these neighbourhoods. As argued by Salama [

2], land use and spatial planning were often managed at the community level, with tribal leaders or local authorities regulating construction and public spaces. Unlike modern gated communities, where private developers or homeowner associations often dictate urban governance, traditional quarters allowed for transformative spatial growth while maintaining a balance between privacy and communal life. Moreover, historical Arabian urbanism maintained a balance between social integration and spatial cohesion, whereas gated communities often reinforced segregation through physical barriers and restricted access. As illustrated in

Figure 7, religious values influenced building heights, entrance orientations, and gender-based spatial arrangements. Such design principles prioritised privacy and maintained external connectivity, a feature that is often missing in contemporary gated communities.

Additionally, place identity, as described by Mohamed [

53], reflects the relationship between physical characteristics and social structures. While historic cities promoted integration through shared courtyards and interconnected street networks, modern gated communities exhibit deliberate spatial isolation. Architectural features such as courtyards, shaded streets, and compact building arrangements facilitated climate adaptation, privacy, and social engagement, as shown in

Figure 8. Conversely, the design of contemporary gated communities often prioritises private over shared spaces, reinforcing spatial discontinuity with the surrounding city.

3.2. Contemporary Case Studies: Modern Gated Communities

While historical Arabian quarters evolved as part of integrated urban systems, contemporary gated communities introduce deliberate physical separations and rigid access control. To better assess the spatial parallels and distinctions between historical quarters and contemporary gated communities,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate common urban patterns in selected modern gated communities [

1]. This study examines two prominent examples:

- (a)

The Kingdom, Riyadh (Saudi Arabia): A high-end gated development designed for expatriates and affluent residents, featuring enclosed perimeters, security-controlled entrances, and private recreational spaces.

- (b)

Dar Al Salam, Qatar: A luxury gated community with a controlled entrance and exclusive residential zoning, illustrating contemporary urban enclosure in the Gulf.

While both historical quarters and modern gated communities incorporate spatial separation, their fundamental urban logic differ significantly:

Traditional quarters evolved within broader urban structures, fostering internal cohesion while retaining integration with the city [

34]. In contrast, modern gated communities impose strict boundaries, often restricting connectivity through private governance models.

Arabian quarters featured shared public spaces, semi-private alleys, and communal courtyards that facilitated interaction. Modern gated communities, however, tend to prioritise private amenities, such as pools, golf courses, and exclusive parks, over shared public spaces, reinforcing exclusivity.

Traditional quarters are self-regulated through social ties, religious principles, and communal administration. By contrast, gated communities rely on surveillance, security personnel, and controlled access technologies to maintain exclusivity.

The transition from historical Arabian quarters to contemporary gated communities raises key questions about the sustainability of enclosed urbanism in the Middle East. While historical walled neighbourhoods evolved organically within larger cities, modern gated communities introduce rigid separations that often challenge broader urban connectivity.

By examining the spatial principles of old Arabian cities, this study identifies key historical attributes that could inform more inclusive and adaptive models for modern gated communities. Rather than reinforcing urban discontinuity, gated developments can be designed to incorporate elements of historical Arabian urbanism, such as open courtyards, semi-private zones, and shared public amenities, without isolating residents from the broader urban fabric. This section contextualises the study’s historical inquiry within broader sociospatial trends, laying the foundation for the analysis of gated communities in the Middle East. The following sections will examine how historical urban patterns compare with contemporary planning models, assessing whether modern gated communities are a continuation, reinterpretation, or departure from these historical precedents.

4. Materials and Methods

The article employs a historical inquiry method, particularly suited to exploring the longitudinal characteristics of old Arabian gated neighbourhoods, aiming to extract attributes that promote social cohesion and integration. The historical investigation contextualises findings derived from an interpretive constructivist approach, connecting past urban practices with contemporary gated community trends. By integrating urban morphology theory [

16] and sociospatial segregation theory [

36], the study examines the evolution of spatial patterns, street networks, and land-use transformations in old Arabian cities and their reinterpretation in modern gated communities. Additionally, it provides a structured approach to understanding how historical patterns of spatial organisation, social hierarchy, and access control persist or evolve in contemporary gated communities. This methodological framework also assesses whether modern gated communities contribute to or challenge social sustainability by fostering inclusivity or reinforcing urban fragmentation.

Historical inquiry serves as a methodological tool to investigate, organise, and explain past events, providing a foundation for constructing interpretations that address the research questions [

11]. As argued by Esterhuizen [

56], historical ignorance will allow mistakes that happened in the past to be repeated in the present.

The literature for this study was sourced through a structured search strategy, ensuring comprehensive coverage of academic and historical materials related to gated neighbourhoods. A systematic review of published scholarly articles, books, and historical maps was conducted using databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The selection criteria focused on peer-reviewed sources and authoritative texts that specifically discuss spatial organisation, privacy structures, and social interactions within both historical and modern urban forms [

57]. Additionally, archival records and historical manuscripts related to Arabian cities were included to ensure an in-depth comparative analysis [

53,

58,

59], whereas non-peer-reviewed sources were excluded to ensure reliability and academic rigour in historical interpretation. To ensure a rigorous and systematic approach, the study combines content analysis and historical inquiry, supported by a structured analytical framework.

4.1. Analytical Framework and Methodology

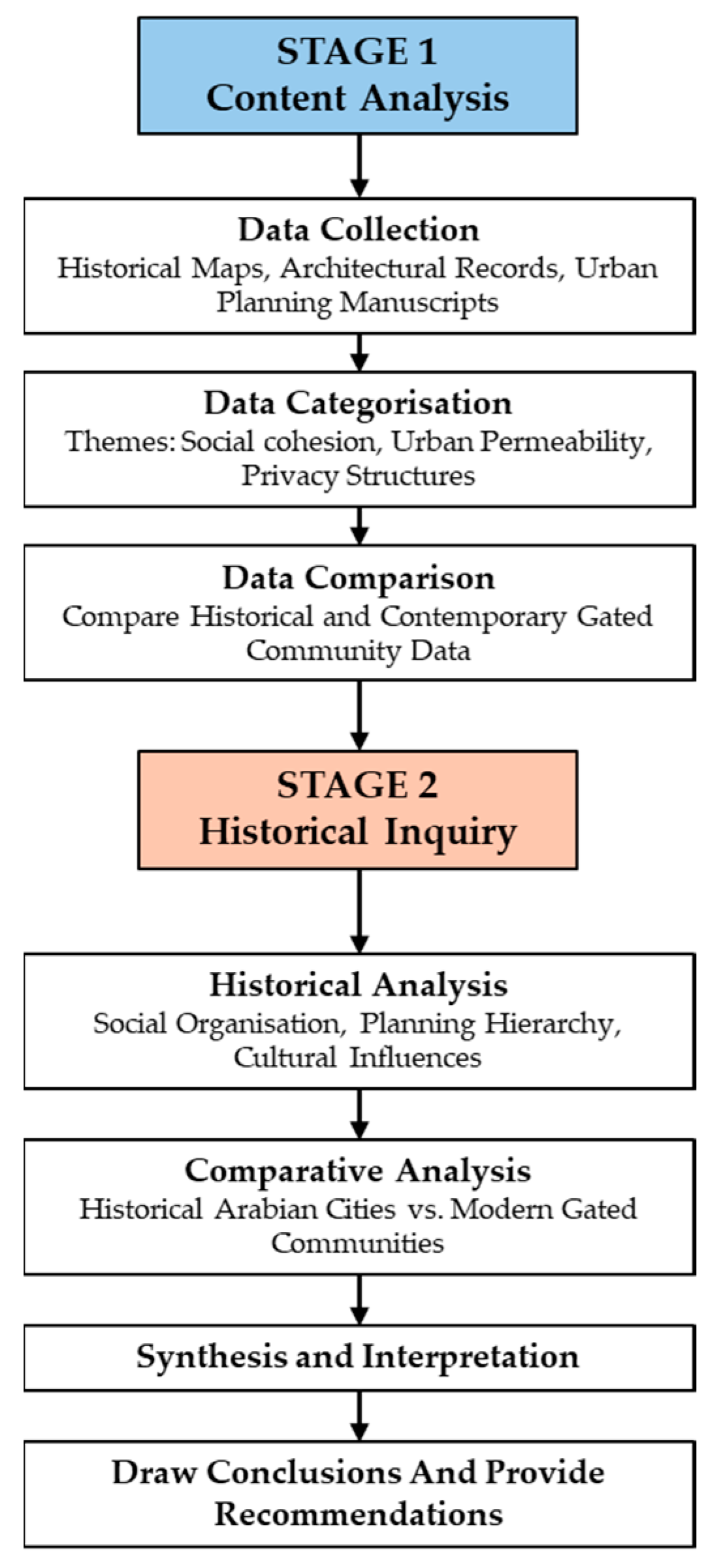

The study follows two stages of analytical methods; stage one will conduct a content analysis of the historical data related to gated neighbourhoods and confine the phenomena or events into defined categories to allow better interpretation [

60]. The second stage will involve a historical inquiry into the old Arabian gated neighbourhoods to extract attributes related to social cohesion and integration and assess their relevance to contemporary gated communities. A coding framework was applied to categorise historical records into thematic groups, allowing for comparative analysis with contemporary gated communities [

61].

Figure 11 provides a flowchart summarising the methodological process, illustrating how historical and contemporary data were analysed to address the research questions.

4.1.1. Stage 1: Content Analysis of Historical Data

Content analysis is employed to categorise and interpret historical data on gated neighbourhoods, focusing on themes including social inclusion, community integration, and urban morphology. This method reduces complex historical material into manageable categories, enhancing interpretation and relevance [

62]. For example, reviewing historical documents related to gated neighbourhoods and walled cities in Old Arabian cities and searching for themes such as privacy, social interaction, social cohesion, and community engagement. By comparing the past and present, the study evaluates whether historical spatial practices that promoted cohesion can offer insights into contemporary urban design, addressing issues of social fragmentation. The literature was evaluated based on thematic relevance, historical accuracy, and contextual applicability to the study’s objectives. The inclusion criteria ensured that sources provided detailed spatial representations and analyses of historical urban forms [

31,

63]. The data set includes historical maps, architectural records, and urban planning manuscripts of historical Arabian urbanism published by several authors, including [

8,

64,

65,

66].

To ensure the relevance and reliability of sources, the following criteria were applied:

Inclusion Criteria

- ○

Peer-reviewed scholarly articles related to spatial organisation, privacy structures, and social interactions in historical and modern urban forms.

- ○

Historical maps and manuscripts which provide detailed spatial representations of Arabian cities.

- ○

Sources explicitly addressing themes such as social cohesion, urban permeability, and privacy structures.

Exclusion Criteria

- ○

Sources lacking historical accuracy or contextual relevance to Arabian urbanism.

- ○

General urban planning literature not specifically addressing gated communities or historical walled cities.

The Content analysis involved:

Identifying Units of Analysis, which may include words or themes that are categorised into defined groups.

Systematically Reviewing Sources to identify recurring themes such as street networks, public-private space transitions, and sociospatial governance structures.

Comparing Historical Findings: this step aims to compare historical findings with the planning of modern gated communities and their sociospatial influence to assess adaptations or transformations.

Krippendorff [

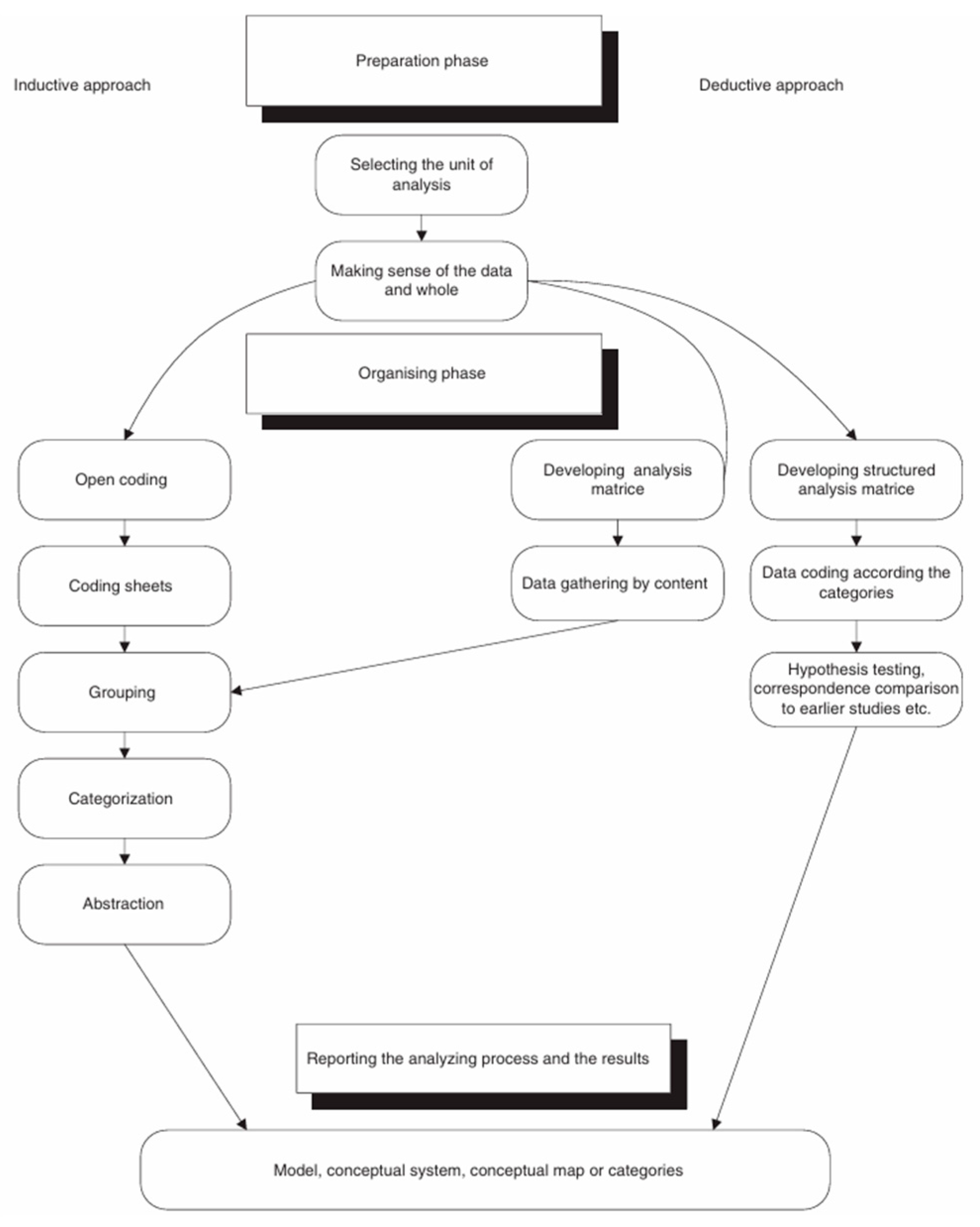

67] describes content analysis as an objective and systematic way to describe and quantify a phenomenon, analyse documents, and test theoretical challenges that can improve understanding of data. Interpretation of historical records may be influenced by the availability and perspective of documented sources, necessitating a critical approach to avoid retrospective bias. Preliminary analysis revealed recurring themes such as the strategic placement of public spaces to enhance social interactions, the adaptation of urban forms to climatic conditions, and the role of hierarchical street networks in fostering connectivity and community resilience. The primary purpose of content analysis is to provide knowledge and diverse insights by creating replicable interpretations from the data set, aiming to achieve an expansive description of the investigated phenomenon [

68]. The process involves selecting units of analysis, such as words or themes, to categorise historical evidence into defined groups. This enables a structured understanding of phenomena like privacy, social interaction, and community engagement, as illustrated in

Figure 12, which outlines the analytical framework for content analysis [

62,

68].

4.1.2. Stage 2: Historical Inquiry into Walled Cities

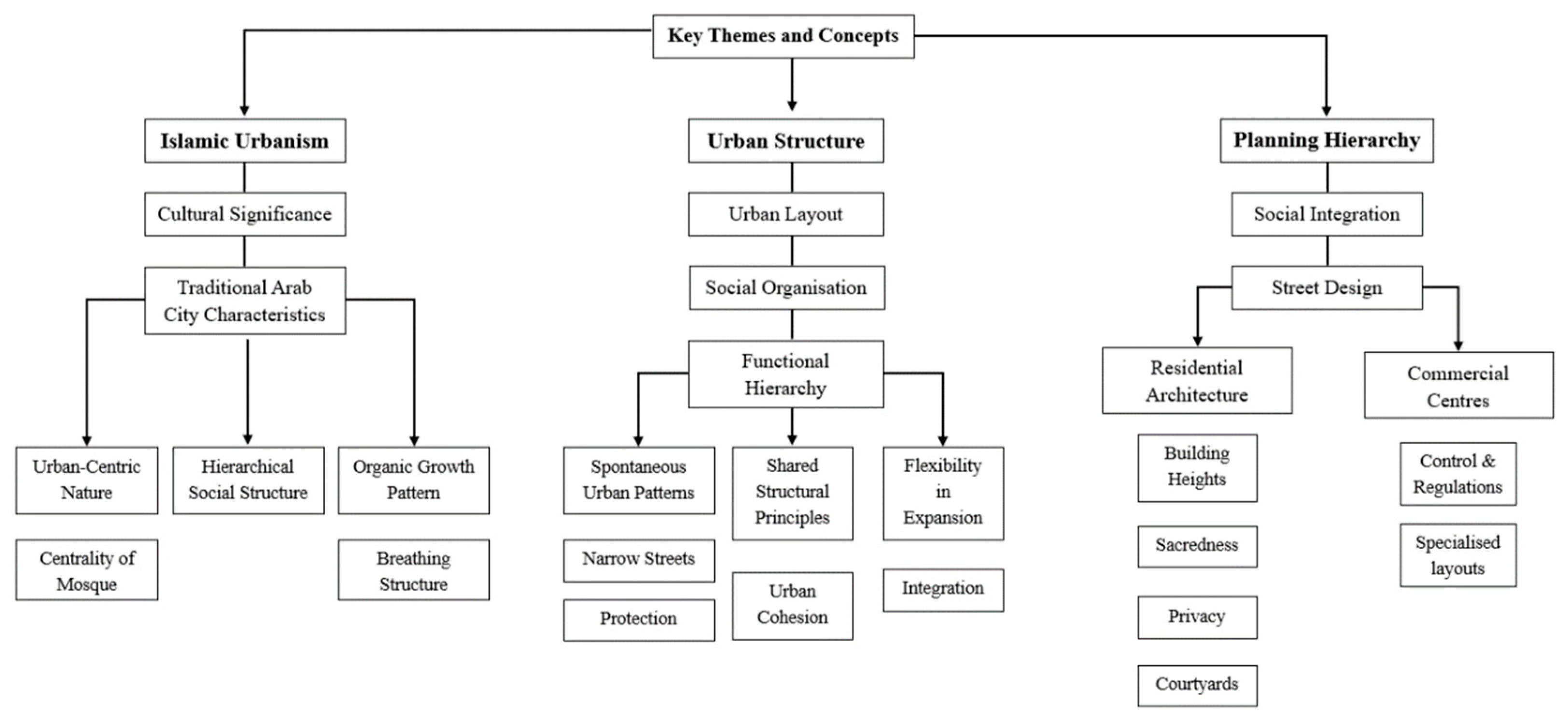

This stage involves a detailed historical inquiry into the urban structures of old Arabian cities, focusing on their gated neighbourhoods. The inquiry investigates elements such as social organisation, planning hierarchy, and cultural influences, as summarised in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 below:

The illustration in

Figure 13 highlights the centrality of mosques, hierarchical social structures, and organic growth patterns within traditional Arabian cities. It illustrates how functional hierarchy and planning principles contributed to urban cohesion and integration. For instance, the centrality of mosques in urban layouts reinforced social and cultural cohesion and also influenced the organic growth of surrounding neighbourhoods. Hierarchical structures ensured balanced growth while allowing flexibility in expansion, a principle that facilitated integration and community resilience.

Through historical inquiry, the study identifies patterns of social cohesion and spatial integration, comparing historical Arabian cities with modern gated communities. Key comparisons include:

- ○

Urban Permeability Against Restricted Access: Examining the accessibility of historical walled cities versus the exclusive nature of modern gated communities.

- ○

Social Cohesion and Fragmentation: Analysing how historical Arabian quarters promoted community resilience and whether modern gated communities enhance or diminish social interaction.

- ○

Privacy Structures: Assessing the evolution of privacy structures from courtyard housing in old Arabian cities to modern gated residences.

These findings highlight the importance of design principles such as centrality and integration, offering a framework for urban planners to address sociospatial segregation in contemporary gated communities by incorporating lessons from historical practices. As explained by Esterhuizen [

56], historical awareness elucidates behavioural patterns that influence contemporary urban practices, preventing the repetition of past mistakes. Similarly, Jacobs [

69] emphasises the value of inclusive, community-focused urban design, which can foster social cohesion and integration.

By combining historical inquiry with content analysis, this study examines how traditional spatial organisation fostered community engagement and whether modern gated communities sustain or disrupt social cohesion, inclusivity, and sustainable neighbourhood structures. Carmona [

70] and Gehl [

71] provide further support for the importance of human-centred design principles, such as centrality and integration, in creating more inclusive urban environments and suggesting lessons on how historical practices can foster social cohesion and integration. By clarifying the document-selection process, content analysis methodology, and evaluation framework, this study ensures a rigorous and systematic approach to investigating the spatial and social impact of gated communities within historical and contemporary contexts. This aligns with the work of Kropf [

16] in understanding how spatial patterns influence social cohesion and inclusivity and emphasising the importance of urban morphology and legibility in fostering cohesive, inclusive urban environments. However, the study acknowledges limitations, including the availability and reliability of historical records, which may influence the generalisability of findings. Despite these limitations, the methodological framework provides a robust basis for addressing the research questions and offering insights that aid in mitigating segregation and enhancing community integration.

5. Results

The historical content analysis, as outlined in the methods section of this study, synthesises the sociospatial and architectural characteristics of old Arabian cities. By applying urban morphology theory (Kropf, 2009) and sociospatial segregation theory [

36], this study systematically analyses how historical patterns of spatial organisation, social hierarchy, and access control have persisted or evolved in contemporary gated communities. These findings contribute to broader discussions on social sustainability by examining whether contemporary gated communities enhance or hinder social integration, accessibility, and community cohesion. The identified patterns in urban planning, such as hierarchical layouts, religious influences, and courtyards, reveal the complex relationship between cultural values and spatial planning, influencing both past and present urban configurations and impacting social sustainability. The historical content analysis establishes a foundation for understanding whether modern gated communities in the Middle East are a continuation, adaptation, or departure from historical principles. Furthermore, the analysis contextualises gated neighbourhoods as sociospatial phenomena within the historical fabric of old Arabian cities. Findings suggest that while traditional Arabian cities facilitated social integration through spatial transitions, modern gated communities enforce rigid enclosures, leading to social fragmentation. The analysis enables a deeper examination of historical principles of privacy, security, and communal interaction and their reflection in contemporary enclosed neighbourhoods.

(

Table 1) presents findings extracted from the historical content analysis, forming the basis for comparing the key features of old Arabian cities to modern gated communities in the Middle East. The thematic analysis focuses on urban characteristics such as spatial hierarchy, religious and cultural influences, architectural typologies, and sociospatial connectivity. The findings highlight that historical urban development is deeply rooted in religion and culture, shaping cities into flexible, hierarchical layouts that balance privacy and social integration. The central mosque emerges as the focal point of urban design, surrounded by markets and public buildings located along primary arteries. Residential patterns exhibit a strong emphasis on privacy, with inward-oriented units integrated seamlessly into streets and alleys. Functional and spatial organisation reflects a clear division between public and private spaces, influenced by social hierarchies, community interactions, and religious practices. Ethnic migrations have also contributed to the formation of town units that connect to urban cores. Notable features include multifunctional city structures, ecological integration, and organic growth patterns that balance public needs with residential privacy. These findings highlight how historical spatial organisation promoted social sustainability by fostering inclusivity, accessibility, and community interaction.

The idea of the content analysis is to extract and link findings from the urban characteristics of old Arabian cities with modern gated communities. Below are the major findings:

Organic Patterns in Spatial Layouts: Organic patterns and hierarchal structures were key features in traditional Arabian cities, influenced heavily by religious and cultural imperatives.

- ○

Finding: Traditional Arabian cities were characterised by organic urban layouts, where streets and pathways emerged naturally in response to social, economic, and cultural needs. This adaptability reflects a highly flexible, community-centred approach to urban development that prioritises inclusivity.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: Historical urban layouts facilitated social cohesion by ensuring interconnected spaces that accommodated diverse social interactions.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Modern gated communities often replicate the organic aesthetics of historical cities in their internal layouts, with features including winding streets and clusters. However, these layouts are pre-planned with fixed spatial configurations that prioritise exclusivity, lacking the functional adaptability and openness of traditional cities, thus reducing opportunities for social inclusion.

Social Hierarchy and Urban Development: The findings reveal that old Arabian cities were structured to reflect gradual social arrangements rather than imposed segregation, with spatial patterns that facilitated movement.

- ○

Finding: Social and religious priorities influenced the urban hierarchy, with central mosque and communal spaces serving as focal points. Residential areas were arranged to promote privacy while maintaining accessibility to shared spaces.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: The hierarchical structure of historical cities did not create rigid socioeconomic segregation but rather allowed for interaction between different social groups within shared communal spaces.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Modern gated communities reflect similar hierarchical structures in terms of exclusivity, catering to specific income groups or social classes. However, unlike traditional Arabian cities, they promote physical and social separation, isolating residents from the broader urban fabric.

Integration of Public and Private Spaces

- ○

Finding: Arabian cities balanced public and private spaces through a gradual transition system rather than strict barriers. Public areas such as markets encouraged interaction, while residential spaces ensured seclusion with marginal separation.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: This balance promoted a socially sustainable environment where privacy was respected without compromising connectivity and social engagement.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Gated communities enhance privacy by implementing physical barriers and restricted access, disrupting urban continuity. This contrasts with historical patterns, where the spatial layout maintained connectivity without exclusion.

Religious and Cultural Influences: The prominence of the central mosque as a focal point and the prioritisation of privacy in residential areas illustrate the influence of religious and cultural values on spatial arrangements.

- ○

Finding: The spatial hierarchy of Arabian cities was deeply influenced by religious and cultural norms, promoting inclusivity in public spaces and seclusion in private areas.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: Religious and cultural values reinforced social bonds by embedding collective gathering spaces that encouraged interaction while respecting social boundaries.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Some gated communities in the Middle East incorporate Islamic architectural themes for aesthetic purposes; however, their primary planning focus reflects Western market designs rather than the continuity of historical structures. This may imply that contemporary gated communities modify rather than inherit traditional Arabian urban principles.

Architectural Elements and Urban Layout: Traditional cities featured a multifunctional mix of public and private structures, integrating houses, markets, and religious buildings within the pedestrian network.

- ○

Finding: Urban connectivity was a defining feature of old Arabian cities, ensuring movement and social interaction.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: This integration facilitated social sustainability by promoting inclusive, walkable communities where everyday functions were embedded within residential spaces.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Gated communities disrupt urban connectivity by enforcing spatial exclusivity. Their reliance on enclosed perimeters and restricted access contradicts the historically interconnected urban structure.

Defensive Features of Walled Cities:

- ○

Finding: Arabian cities were fortified with walls, gates, and watchtowers for security. These defensive elements influenced urban compactness and controlled movement.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: Walled cities created a balance between security and community access, allowing controlled interactions within the city while maintaining protection from external threats.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: Modern gated communities replicate this controlled access model but prioritise exclusivity rather than collective security. Unlike historical walled cities that remained interconnected, gated communities restrict movement beyond their perimeters, creating isolated enclaves.

Colonial Influence on Urban Form:

- ○

Finding: Many Arabian cities underwent colonial interventions that altered their spatial organisation, introducing new infrastructure and hybrid architectural styles blending European and local designs.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: Colonial transformations disrupted traditional spatial patterns but also introduced modern urban planning concepts, some of which later influenced contemporary city layouts.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: The Western-style planning imposed during colonial periods influenced the enclosed, exclusive nature of modern gated communities, marking a shift from traditional integrated urban models.

Climatic Adaptation and Sustainable Techniques:

- ○

Finding: Arabian cities incorporated climatic-responsive techniques, including passive cooling systems (wind towers, courtyards, shading elements), narrow alleys for natural cooling, and water channels.

- ○

Link to Social Sustainability: These passive cooling strategies made urban living more sustainable and energy-efficient, enhancing comfort without relying on modern energy-intensive systems.

- ○

Link to Gated Communities: While some gated communities incorporate sustainability features, many lack the traditional adaptive techniques of Arabian cities, opting instead for high-energy consumption models dependent on artificial cooling.

The historical content analysis demonstrates the transition from integrated, community-driven layouts to the spatially segregated gated communities of today. While historical Arabian cities maintained a balance between privacy, accessibility, and social cohesion, modern gated communities often prioritise exclusivity and controlled access over connectivity and social integration [

38,

48,

72]. The defensive features of old walled cities ensured protection while maintaining internal social fluidity, whereas contemporary gated communities enforced physical and social isolation. Similarly, colonial planning interventions introduced spatial discontinuities that influenced the emergence of enclosed residential models, reinforcing the socioeconomic divide [

21,

24]. Additionally, historical Arabian cities integrated passive cooling techniques and climate-responsive designs that enhanced environmental sustainability [

7,

73]. In contrast, many modern gated communities rely on energy-intensive systems that overlook local climatic adaptations, further disconnecting them from the sustainable practices of historical urbanism [

37].

The urban transformation raises critical questions about how contemporary urban planning can incorporate the lessons of historical Arabian cities to enhance inclusivity while maintaining privacy. By examining the historical spatial organisation of privacy through gradual transition spaces rather than strict barriers, urban planners can explore alternative models for designing residential communities that do not reinforce social division. The findings reinforce the need for culturally grounded planning approaches that merge historical sociospatial principles with modern urban needs. This analysis emphasises the broader implications of gated communities on urban fragmentation, accessibility, sustainability, and community cohesion in the Middle East by implementing sociospatial traditions in creating cohesive urban structures.

6. Discussion

This section critically examines whether modern gated communities in the Middle East represent an evolution, reinterpretation, or departure from the sociospatial principles of historical Arabian cities. It contextualises these developments within broader urban trends, such as privatisation, security concerns, and socioeconomic stratification, to assess their long-term implications for urban cohesion. Building upon the findings in the results section, this discussion explores key urban patterns, such as spatial hierarchy, privacy, and integration, to assess how modern gated communities align with or diverge from historical urbanism. The evolution of Arabian cities was shaped by gradual transformations influenced by sociopolitical, religious, and environmental factors, as explained by Abu-Lughod [

38]. Unlike modern gated communities, which rely on pre-planned zoning and access restrictions, historical Arabian cities evolved organically, allowing for incremental spatial modifications that responded to social, economic, and environmental shifts. One major factor that contributed to urban transformation in Arabian cities was the influence of long periods of colonisation [

21,

24]. Colonial rule introduced new governance structures, imposed zoning laws, and altered urban layouts, which, in some cases, disrupted the organic development patterns of historical cities. These imposed planning regulations contrast with the adaptable and locally governed nature of traditional Arabian urbanism and are reflected in the rigid zoning of modern gated communities [

37]. While historical cities had spatial divisions based on ethnicity and social background, as seen in the separation of Christian and Jewish families into distinct neighbourhoods within Arabian cities, these divisions remained functionally connected, allowing for economic and social interdependence [

38]. In contrast, modern gated communities reinforce these distinctions through physical barriers and controlled access. Furthermore, property laws and regulations, such as the right of precedence and the right of vivification, established decentralised governance models that allowed for localised decision-making [

7]. This approach fostered self-regulated communities where residents played a central role in spatial organisation and governance, contrasting with contemporary gated communities, where external zoning laws and homeowners’ associations impose rigid spatial and social regulations. Unlike historical Arabian neighbourhoods, where spatial adaptability ensured an evolving socio-urban fabric, modern gated communities enforce rigid spatial arrangements that limit both physical and social flexibility [

48].

Additionally, historical Arabian cities integrated climatic considerations into their design, employing passive cooling techniques such as narrow alleyways, inward-facing courtyards, and shading elements to mitigate the impact of the hot climate. These sustainability-driven strategies align with the broader concept of bioclimatic urbanism, which emphasises the adaptation of built environments to local climatic conditions. For example, the use of wind catchers and shaded alleyways in cities like Yazd and Jeddah demonstrates how historical urbanism prioritised environmental responsiveness, ensuring thermal comfort and energy efficiency [

73]. In contrast, modern gated communities often prioritise aesthetic and luxury-driven design over environmental responsiveness, leading to increased energy dependency and reduced thermal comfort in outdoor spaces. However, it is worth noting that some contemporary developments have attempted to incorporate sustainability measures and certifications, though these efforts remain secondary to their exclusivity-driven design approach.

Key Considerations for Contemporary Planning

To develop socially cohesive and contextually responsive urban environments, it is essential to draw insights from historical Arabian cities, particularly in decentralising land-use authority and fostering organic spatial development. Although historical urban layouts reflected cultural and social distinctions, their adaptive governance models and communal integration provide critical lessons for contemporary planning. In an attempt to employ these principles, the design of modern gated communities can consider the following:

Ethnic and social diversity: Encouraging a diverse resident population and offering varied housing options for different socioeconomic backgrounds to reflect the social fabric of Arabian cities. This approach aligns with the historical concept of organic growth, which accommodated a mix of residents while fostering communal harmony.

Spatial organisation: Decentralising decision-making of gated community residents by empowering them to create common spaces and amenities. This can foster a sense of ownership and engagement, replicating the autonomous governance observed in historical Arabian neighbourhoods. This can be achieved by establishing a resident design committee that can be involved in design decisions.

Cultural sensitivity: Incorporating cultural principles of privacy and respect for diversity, as observed in historical Arabian cities. This can be achieved through culturally appropriate recreational facilities, such as gender-specific spaces, which enhance inclusivity while respecting traditional values. For instance, gender-segregated swimming pools or communal courtyards can cater to different cultural preferences. However, several contemporary developments in the Middle East claim to integrate traditional Islamic architectural elements, but they often lack the spatial adaptability and social connectivity embedded in traditional Arabian urbanism.

Community engagement: Facilitating collaboration and communication among residents by encouraging participation in town hall meetings or homeowners’ associations. This approach mirrors the communal ethos of historical neighbourhoods, where residents collectively addressed shared responsibilities, including defence and social support.

Adaptable designs: Creating spaces that can respond to changing demographics and community needs, such as flexible infrastructure, layouts, and amenities that serve multiple purposes. For example, a central court could function as a playground, a community garden, or a fitness area, depending on residents’ preferences. This adaptability is often absent in contemporary gated developments, where strict land-use regulations and controlled access limit such multifunctionality.

Findings indicate that historical Arabian cities maintained a vibrant balance between private and communal spaces, integrating commercial, religious, and residential functions within a cohesive urban fabric. In contrast, modern gated communities enforce spatial fragmentation through rigid physical barriers, limited accessibility, and exclusive residential zoning. The transition from ethnic-based spatial arrangements in historical cities to economically driven segregation in modern gated communities highlights the transformations in urban sociospatial logic. A key point of departure from historical models is the treatment of architecture as a purely aesthetic feature rather than a socially embedded and functionally driven element. Unlike historical Arabian cities, where architecture responded to environmental, social, and economic conditions, modern gated communities often use Westernised aesthetics and luxury-driven planning, distancing them from their historical sociospatial values. This trend mirrors urban transformations observed in other regions, where contemporary housing models struggle to integrate sociocultural identity and sustainability. For instance, Herrera, Pineda, Roa, Cordero and López-Escamilla [

73] examined sustainable social housing projects that attempted to balance private and communal spaces, drawing lessons that could be applicable in Middle Eastern contexts. Similarly, Núñez-Camarena, et al. [

74] explored the role of memory and identity in urban regeneration, highlighting how revitalisation efforts in historical neighbourhoods can enhance social cohesion and preserve cultural narratives. These studies provide relevant insights into how modern gated communities might better integrate heritage and sustainability principles into their designs.

While modern gated communities may use some elements from historical urbanism, such as privacy and hierarchical spatial organisation, they contradict key principles. For instance, traditional Arabian cities developed organically, allowing for gradual spatial and social adaptation to the needs of their residents. In contrast, contemporary gated communities are often pre-planned and rigidly zoned, restricting spontaneous social interactions and adaptability. For example, gated communities in Saudi Arabia are considered private residences with strict access and controlled limits, reinforcing segregation between different socioeconomic layers [

75]. Similarly, Bahrain’s gated communities create urban fragmentation, contrasting with the historical Arabian concept of communal living, where urban quarters facilitated shared social functions [

24]. Moreover, the adoption of Western architectural styles and planning models in many Middle Eastern gated communities further alienates them from traditional Arabian urbanism. The influence of global real estate markets and international investors has led to an emphasis on luxury, exclusivity, and Westernised aesthetics, distancing contemporary urban forms from the sociospatial values of historical cities [

21,

37].

Addressing the sociospatial challenges posed by modern gated communities requires a reconsideration of how historical Arabian urbanism can inform contemporary planning. While integrating historical urban principles, such as mixed-use zoning and permeable boundaries, could mitigate exclusionary effects, these solutions must account for modern governance constraints, economic pressures, and security concerns that drive gated community development today. By drawing inspiration from historical sociospatial practices, such as balancing public and private spaces, fostering inclusivity, and enabling resident autonomy, gated communities can create socially sustainable and culturally sensitive environments that resonate with the rich heritage of Arabian cities.

7. Conclusions

This study examines the sociospatial and architectural characteristics of historical Arabian cities and their influence on contemporary gated communities in the Middle East. It provides new insights into how historical spatial practices, such as hierarchical spatial organisation, communal integration, and controlled access, have been selectively adapted, reinterpreted, or abandoned in modern developments. While previous studies have explored the spatial evolution of gated communities, limited research has systematically examined the sociospatial connections between historical enclosed neighbourhoods and modern gated communities. The findings reveal a nuanced relationship between historical urban patterns and contemporary urban planning practices, highlighting both continuity and divergence. Traditional Arabian cities exhibited organic growth, cohesive spatial arrangements, and integrated social hierarchies deeply rooted in cultural and religious values. These historical configurations prioritised privacy, community engagement, and connectivity, balancing public and private spaces to foster strong social cohesion.

While modern gated communities adopt elements of historical urbanism, such as privacy-oriented layouts and controlled access, they differ significantly in their sociospatial principles. Instead of fostering organic community relationships, contemporary gated developments reinforce exclusivity and controlled access, creating spatial barriers that contribute to socioeconomic stratification. Unlike traditional Arabian cities, which evolved to accommodate diverse sociocultural needs, modern gated communities impose rigid spatial divisions, reinforcing exclusivity and reducing organic social interactions. This reflects broader global urban trends, where privatisation, security concerns, and market-driven developments shape residential enclaves that are disconnected from their surrounding urban fabric. The planned exclusivity and controlled access of gated communities often disrupt urban connectivity, posing challenges to social sustainability by limiting integration, reducing shared public spaces, and reinforcing urban fragmentation. For example, while historical cities integrated market areas and religious nods to facilitate social interaction, modern gated communities often restrict access to non-residents, creating urban islands separated from the surrounding city.

The findings emphasise the relevance of historical sociospatial principles in contemporary urban planning. However, integrating these insights into modern gated communities requires addressing critical challenges, including urban governance frameworks, economic constraints, and real estate market requirements. To enhance social sustainability and mitigate urban fragmentation, urban planners and policymakers may consider the following practical strategies:

Developing zoning regulations that encourage mixed-use developments, ensuring a balance of residential, commercial, and public spaces, as seen in traditional Arabian cities. This can be achieved by enforcing semi-public courtyards, shaded walkways, and communal spaces within gated developments to enhance social interaction and accessibility.

Introduce urban connectivity incentives requiring developers to create permeable boundaries, such as controlled pedestrian pathways or shared green spaces, in order to maintain interaction between gated communities and the surrounding areas. This can be attained by promoting gradual transition zones rather than rigid barriers, such as buffer zones with retail, cultural, or community spaces that serve both gated and non-gated residents.

Implement participatory planning approaches that involve residents in decision-making processes regarding shared facilities and accessibility policies. This requires inclusive design elements, such as public plazas, integrated mosques, and accessible markets, to reduce exclusivity while respecting cultural privacy needs.

Develop affordable housing integration programs within or adjacent to gated developments, ensuring diverse socioeconomic representation. This can be achieved by implementing land use strategies that incorporate both private and public functions to prevent spatial and economic segregation.

A crucial aspect of social sustainability is the sense of belonging, which was deeply embedded in the structure of historical Arabian cities. Unlike modern gated communities, where exclusivity is largely driven by economic segregation, traditional urban environments fostered strong communal ties through shared religious, commercial, and social spaces. The presence of mosques, market streets, and interconnected residential quarters facilitated daily interactions and collective responsibilities, reinforcing a shared identity among residents. In contrast, the controlled access and privatised nature of gated communities often result in social isolation and weaker community bonds, limiting organic interactions that once defined traditional urban life. This transition highlights a fundamental departure from the socially cohesive frameworks of historical Arabian cities, where urban planning was inherently tied to cultural and social values rather than market-driven exclusivity. Furthermore, planners may interpret historical principles of inclusivity and permeability with current urban demands without reinforcing sociospatial segregation. By reinterpreting gated communities as adaptive, inclusive, and community-oriented spaces, urban planners can mitigate their sociospatial influence and foster sustainable and socially inclusive urban environments.

Despite these insights, the study acknowledges certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. The breadth of the literature analysed, while extensive, may not fully capture all regional variations in historical and contemporary urban planning. The historical review is limited by its focus on select periods and case studies, potentially overlooking other significant sociospatial transformations. Additionally, the typologies of gated communities investigated were constrained to specific urban contexts, meaning that findings may not be fully generalisable to all Middle Eastern cities. Moreover, this research primarily relies on secondary sources, which, while valuable, limit the inclusion of firsthand perspectives from key stakeholders, such as residents, urban planners, and policymakers. Future studies could benefit from empirical research incorporating interviews and ethnographic studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the lived experiences within gated communities.

Lessons from historical Arabian cities offer valuable insights for developing urban models that enhance social sustainability and cultural continuity. By bridging urban morphological theories, sociospatial structuring, and community integration frameworks, this study contextualises the evolution of spatial segregation from historical necessity to contemporary exclusivity. It emphasises the need for planning strategies that incorporate historical urban principles to respond to the growing sociospatial fragmentation in gated communities. These findings contribute to a broader discussion on urban sustainability, providing a framework for future research on how enclosed residential developments can be designed to support social integration rather than reinforce segregation.