1. Introduction

The informal city, also known as the clandestine city and usually associated with the phenomenon of urban self-organisation, appears as ‘the visible manifestation of poverty and inequality in cities’ [

1] and is a reality that cuts across all societies and occurs in the most diverse regions of the world.

In an article published in 2023, Kieran McConville [

2] posed the following question: Why do people live in slums? The answer points to the idea that living in a slum is a better alternative to a previous situation, usually one of extreme poverty and a lack of opportunities. Informal housing, which is often part of overcrowded, poorly served and unhealthy neighbourhoods, has proved to be the only affordable housing option for a significant part of the population in the Global South [

3]. This means that the informal city, the self-organised city, is proving to be the ideal city for a large number of people.

The informal city appears as an urban idealisation, a utopia, not as a premature truth imagined isolated in a ‘u-topos’ (no place), but as the spatialisation of an urban nature of its own, which, although it has many defects, opens up ‘possibilities’ for a new way of life. This urban idealisation emerges as a necessary and immediate response to the absence of public land policies, the failures of the housing market or situations arising from social and economic crises. In the image of utopian cities, these are territories emancipated from planning and public powers, territories that diverge from, but are concurrent with, the formal city, generated through organic processes that take place outside the system and on the fringes of institutional urban planning practice. For this reason, it is necessary, in order to improve the results of public city policies, to develop a broader understanding of the formations of informal settlements in order to find out to what extent this model of territorialisation corresponds to an urban organisational structure that occurs when it is up to society to provide its own habitat and urban environment? And in this case, what do we have to learn from this way of making a city, which some authors call entropic urbanism?

The need to understand the operating logic of urban entropy associated with the formation of informal urban settlements and to include it in the technical and theoretical field of urban planning and management is recognised by UN-Habitat [

4] as an instrumental element of city policies, considering that, ‘In many cities, informal settlements are so common and house such a large proportion of the population and labour force that they cannot be the exception, but the rule. If the laws and regulations in force in a country consider the homes and livelihoods of a large part of the city’s population to be illegal, then the adequacy of the law must be reviewed.’

On the other hand, regardless of the different geographical realities in which these human settlements are located or the different social and cultural values that identify their residents, it is possible to observe the existence of very similar solutions in their territorialisation processes, their spatialisation patterns and their urban morphology. Given this data, another question arises: Why do such different cultures, in such different geographies, adopt a common idea of an ‘informal city’ to live in?

The answer to these questions requires an in-depth study, which is beyond the scope of this article. The aim is simply to provide a framework for this urban phenomenon and to develop some reflections, based on technical and statistical information, and complementary to the theoretical notions set out and defended in multiple studies on the subject of informal settlements. Find possible answers to the questions posed and to explore the distinctive aspects of the informal city can help us understand the formation of its alternative urbanism, the aspects that define its socio-morphological identity, which I have referred as an urban idealisation.

Understanding the morphogenesis of the informal city, generally expressed by a complex fabric and a labyrinthine design, is possibly one of the greatest challenges facing urban planning theory and practice today. To Kamalipour and Iranmanesh, urban informality is a multifaceted, complex and multidimensional concept, which hardly lends itself to accurate and concise definitions, and informal urbanism is an open multiplicity working in relation to formality across different scales and contexts [

5]. Forms of informality incorporate a range of tactical activities including what Bayat [

6] calls ‘the quiet encroachment of the ordinary’.

Throughout the following pages, the reader is invited to debate and critically analyse the themes and issues presented. It starts from the idea that the ‘urban’ is constantly being redefined in a significant number of visions and scenarios of what the city of the future might look like, perhaps an ideal city.

2. The Global Scale of Informal Urbanisation

Informal settlements are growing all over the world. The projected growth by 2050 is that three billion people will be living in slums, which equates to 183,000 people every day [

5]. Between 2000 and 2020 there was a decrease in the relative number of people living in slums—in this paper, we have used the English term ‘slum’ because it is the word most commonly word used to describe informal urban settlements; the term was also adopted because it can include a number of other terms such as favela, barrio, musseque, etc., all of which designate the same urban phenomenon—from 31.2 per cent to 24.2 per cent of the urban population. However, in the same period there was an increase in the absolute number of slum dwellers—from 894.9 million to 1.06 billion people. Of these, 85% live in three regions: Sub-Saharan Africa, 230 million (50.2% of the urban population); Central and South Asia, 359 million (48.2% of the urban population); and East and Southeast Asia, 306 million (21.7% of the urban population) [

7].

In 2022, the UN Habitat ranked the following countries among those with the highest percentage of urban population living in slums—ranging from over 90% to over 60%: Afghanistan, Angola, Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan [

8] (p. 12). Of these, four are Portuguese-speaking African countries (PALOP).

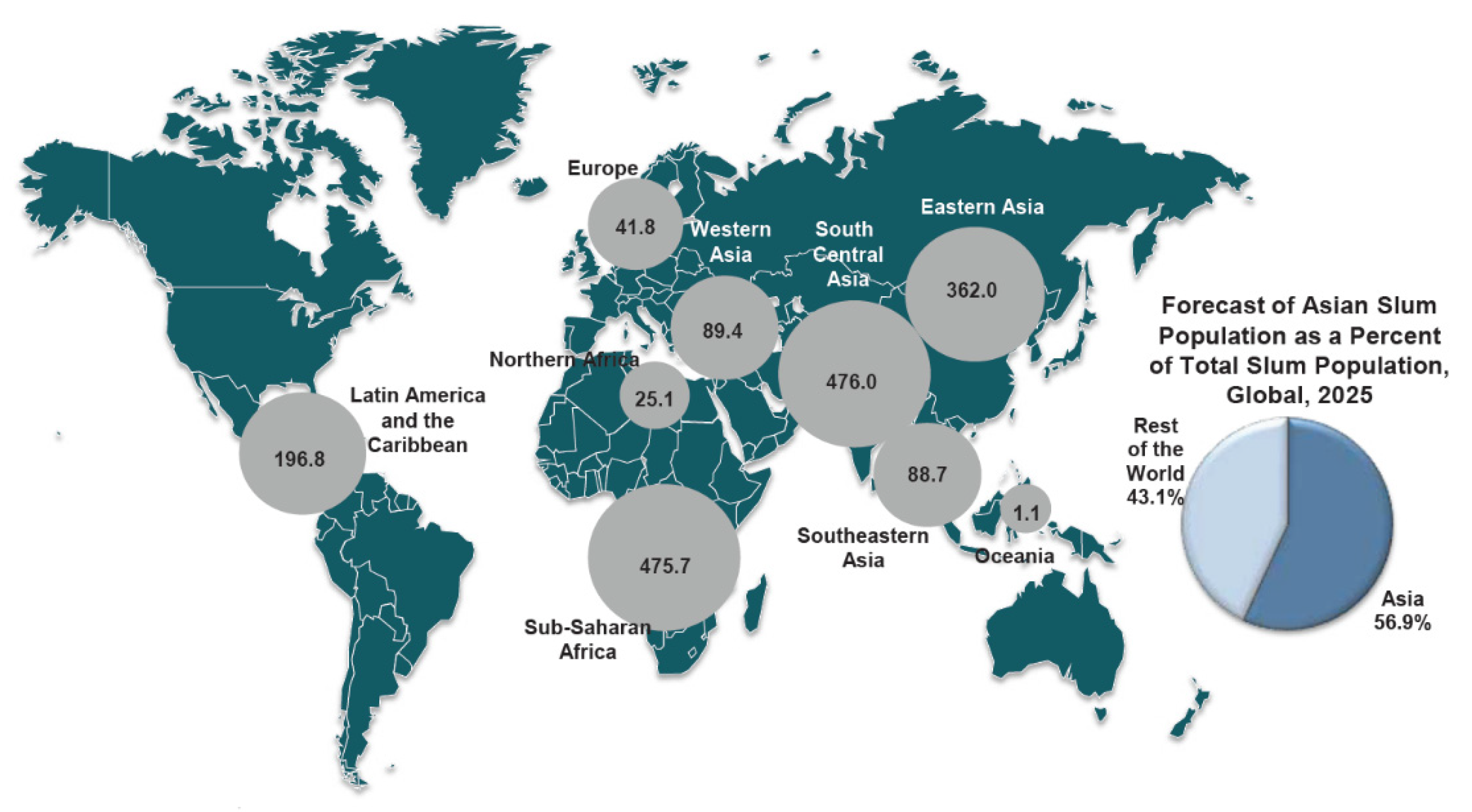

In the projection of the population living in slums in 2025 (

Figure 1), the vast majority is distributed across the countries of the Global South and Asia, which makes these regions the main focus of attention for policymakers and academic researchers. Little is known about what is happening in the countries of the so-called West, specifically in Europe, where it is estimated that 41.8 million people will be living in slums or ‘severe homelessness’ by 2025. (The rate of severe housing deprivation is defined as the percentage of the population living in a dwelling that is considered overcrowded and also has at least one of the following measures of housing deprivation: (i) leaking roof, (ii) no bath/shower and no indoor toilet and (iii) considered very dark. The data come from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).) Several reports and publications confirm the existence of slums and informal settlements in Europe (in the Portuguese case, the so-called Urban Areas of Illegal Genesis (AUGI)) and a growing body of evidence suggests their resurgence in the face of the housing crisis. However, “there is generally little attention in policy and scientific research on slums and informal settlements in European cities and how data and methodologies can fill this gap [

9].

The housing crisis is now present in all regions of the world and has become a global crisis. Although the housing shortage was previously seen as a problem faced by developing countries, the needs manifested are different, with many rich countries struggling with the urgency of ensuring that their citizens have access to adequate housing.

Data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that in recent years, housing costs have risen faster than incomes and inflation. In metropolitan areas, buying a house in the city centre is, on average, 30% more expensive than it is in the suburbs. Unable to afford affordable housing, families have no choice but to live in precarious homes with little access to sanitation services, electricity and drinking water [

10]. From the above, it is plausible to admit that—both because of its scale and because of what it represents—the informal city is emerging as the global city of poverty.

3. Definitions and Concepts of the Informal

Looking up the meaning of the term ‘informal’ (adj m+f) in the dictionary (Michaelis: Brazilian Dictionary of the Portuguese Language), it appears as something that ‘rejects defined forms’ or ‘is not formal, does not observe rules and formalities.’ However, when we talk about informal settlements, we need to avoid seeing such a complex phenomenon only as a two-dimensional relationship—formal or informal—where the terms are mutually exclusive. There are different understandings of the definition of ‘informal settlement’ and from the political-legislative and administrative point of view of urbanism

stricto sensu (Diogo Freitas do Amaral (1993). Urban Planning Law (Summaries), Lisbon), we are wandering in a ‘tierra incognita’ [

11] (p. 10).

Informal settlements have been the subject of various studies and projects, but a number of questions remain unanswered, although some definitions and concepts help us to understand the phenomenology behind them.

A study [

12] by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe states that ‘the multidimensional nature and the entire spectrum that forms between the notion of formality and informality must be taken into account’, identifying the following types of informal settlements:

(i) squatter settlements on public and private land, (ii) settlements/camps for refugees and vulnerable people and

(iii) illegal subdivisions of private or public land, often on the urban periphery and (iv) overcrowded, dilapidated housing without adequate facilities in urban centres or densely urbanised areas. Other types of informal settlements are also considered, such as

(i) Roma settlements and other itinerant groups, which can be either temporary or permanent, and

(ii) high-density informal occupations in large cities, linked to economic crises, unemployment, migration, etc. [

11] (p. 23).

The various types identified occur both in the more recently built peripheral and suburban areas and in the older stabilised areas of the urban fabric. In the 2030 Agenda, indicator 11.1.1 integrates the population living in slums, informal settlements and inadequate housing into the same sustainable development goal, with slums being in the common space where, in this system, their territories intersect. This understanding places informal settlements in the urban continuum where situations of deprivation or inadequate living conditions occur, even though slums are often not recognised and treated by the public authorities as an integral or equal part of the city.

The criteria that characterise a slum are usually related to absolute poverty, as opposed to relative poverty, which is more related to deprived areas and inadequate housing. UN-Habitat defined a slum in 2003 as ‘a contiguous settlement in which the inhabitants are characterised by inadequate housing and basic services’. It is an area that combines, in varying degrees, the following characteristics:

(i) a precarious residential situation; (ii) inadequate access to drinking water; (iii) inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure; (iv) poor structural quality of housing; and (v) overcrowding. [

8] (p. 11).

In the slums, households are operationally defined as those in which the residents lack one or more of the following indicators:

(i) drinking water supply; (ii) access to sanitation facilities; (iii) sufficient living space; (iv) lack of housing durability; and (v) security of tenure and/or permanence. The first four indicators are based on conventional definitions; the last indicator is the most difficult to assess and is not currently used in the evaluation of slums [

1].

From this perspective, inadequate housing conditions (substandard housing) and the use of non-permanent or non-residential areas for permanent housing continues to be the critical identifier for the persistence of poverty in the world, especially in large Asian, African and Ibero-American cities, but also in European cities or in the so-called Western world.

From the 1960s onwards, there was an explicit critique of the theory of social marginality associated with slums, which led to a dichotomous vision marked by the opposition between city and slum. Little by little, various factors contributed to calling into question this way of seeing the favela as a problem, and its removal in massive operations for new housing as a solution [

13] (p. 131). Contributing to this new view of informal settlements were authors who valued the street and the neighbourhood as a place for social ties and the practices of urban life, such as Christopher Alexander, Jane Jacobs and Herbert Gans, who were at the origin of an important current that opposed and criticised functionalist urbanism. This revolt against the errors of functionalist fundamentalism, of which TEAM X was the main protagonist, became a reason for many architects of the time, in an attitude of self-criticism, to try to revise their original models with a view to a more familiar design and ‘contextuality’ with a focus on history, vernacular traditions and the so-called spirit of the place.

In another conceptual universe, close to urban utopia, the Unitary Urbanism advocated by the Situationist International (SI) that was an international organisation of social revolutionaries made up of avant-garde artists, intellectuals and political theorists, prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution in 1972, supported overcoming functionalist urbanism proposing ‘to achieve, beyond the immediate utilitarian, a passionate functional environment’ [

14] (p. 52). Unitary urbanism opposes the fixation of cities in time, advocating their permanent transformation, promoting an accelerated reconstruction of the city in time and, if possible, also in space, a situation that is very similar to the transformative dynamics of informal urbanisation.

Willian Mangin (1967) and John Turner (1969), based on their research and fieldwork in these ‘marginal’ neighbourhoods (in Brazil and Peru), argued that, contrary to popular belief, they were a popular and effective response to the housing shortage in large metropolises undergoing rapid urbanisation, as well as contributing to the national economy, thanks to the investments made by residents in their homes and the small businesses that were established there [

13] (pp. 132–133). This view on both aspects—housing and the economy—is still very relevant today: In a recent interview, published 7 March 2025, in the newspaper EXPANSÃO, Ilídio Daio, a professor of architecture at the Faculty of Architecture, University Agostinho Neto of Angola, states, the

musseque (name given to the informal city and slums in Angola) should not be a problem, but part of the solution. It is a place where people insist on living, calling for the construction of infrastructure and public facilities. Another article, published in the

Folha de S. Paulo (Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, 4 November 2022.

https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/folha-social-mais/2022/11/potencial-de-consumo-em-favelas-chega-a-r-167-bilhoes-em-2022.shtml (accessed on 17 March 2025)), states that according to research carried out by Outdoor Social Inteligência (Outdoor Social Inteligência.

https://revistalivemarketing.com.br/outdoor-social-inteligencia-lanca-formato-de-pesquisas-brand-lift-para-campanhas-em-comunidades/ (accessed on 17 March 2025)), “the potential for consumption in favelas will reach BRL 167 billion in 2022”. Most of the money will be spent housing, with more than BRL 50 billion, followed by food within the home, which exceeds BRL 17 billion and, in third place, building materials, which correspond to more than BRL 6.6 billion.

The reality of Brazil’s

favelas (name given to the informal city and slums in Brazil) has changed a lot in the last 20 years, especially since the City Statute (Constitutional Provisions Law No. 10,257, 10 July 2001) came into force in 2001, with programmes for urban improvements and improvements, major sanitation works, the reurbanisation or construction of new housing units and some land regularisation programmes [

15] (pp. 89–90). Taken together, these factors progressively led to a new policy of public intervention, which included a more positive view of the favela, no longer pointing out the lack of suitability of these neighbourhoods when compared to neighbourhoods considered ‘normal’.

This political change is evident in the redefinition of the concept of

favela by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Since 1950, a favela was referred to as a ‘subnormal agglomeration’: a group of at least 51 housing units (shacks, houses, etc.) lacking, for the most part, essential public services, occupying or having occupied, until recently, land owned by others (public or private) and generally arranged in a disorderly and/or dense manner [

16]. In the results of the 2022 Demographic Census, ‘

Favelas and Urban Communities’ is the new nomenclature adopted by the IBGE to identify these territories in surveys and censuses. For the IBGE,

favelas become to be understood as popular territories that are the result of strategies created by the population itself to meet the needs of housing, commerce and services, among others, in the face of insufficient and inadequate public policies and private investment to guarantee the right to the city. This approach reflects the IBGE’s commitment to progressively improving its methodologies with a view to representing Brazil’s socio-spatial diversity in all its many aspects.

4. A Tendency Towards Urban Disorder and Entropy

Richard Sennett (1970) argues in The Uses of Disorder [

12] that our concern with disorder is fundamentally a concern about the loss of control in an increasingly urbanised world. Throughout the historical and evolutionary process of ‘urbanite’ (an expression used by Richard Sennett) societies, the practices of architecture and urbanology have sought to combat this loss of control, presenting forms and schemes for organising space based on compositional codes, building indices and parameters, legally instituted rules and regulations.

Steven Hawking says that ‘the increase in disorder or entropy over time is an example of what … distinguishes the past from the future, giving time its meaning.’ Drawing on the second law of thermodynamics (formulated by Sadi Carnot in 1824 and reformulated in 1860 by Rudolf Clausius and William Thomson), which states that the state of entropy of the entire universe, as an isolated system, will always increase with time, and that changes in entropy in the universe can never be negative, Hawking explains that it ‘results from there being more disordered states than ordered ones’ and that assuming a system that ‘starts from a small number of ordered states’, as time passes its state will change, and the system is likely to be in a disordered state, i.e., ‘disorder will tend to increase with time’ [

17] (pp. 169–170). Similar to Sennet and Hawking, many authors defend the idea that

disorder is a pattern, while order is temporary. Our quest for order, in this case, urban order, is a successive and difficult attempt to keep things simple, reduce entropy and facilitate the management of complexity. As James Gleick points out, ‘it seems that containing entropy is our quixotic purpose in the universe’ [

18].

Can the phenomenon of informal urbanisation be explained by entropy? The reason for this approach, typical of an experimental science like physics, has to do with the idea that it is very likely that the way cities grow and are built, as activities that take place in our Universe, does not escape the rules that govern the rest of the things that exist in it (Creative Commons License, ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

https://urbequity.com/en/urbanism-and-thermodynamics-an-alternative-approach/ (accessed on 10 January 2025)).

Assuming this hypothesis, it means that the formulation of ‘entropic urbanism’ as a new field of urban sciences can help to understand the processes, forces and phenomena operating the formation, creation and decline of cities, the logic of which needs to be integrated into urban planning. ‘Entropic urbanism’ tends to emerge in the discourse among urban planners who claim that less order could be the future for the development of successful urban communities, especially given that most urban planning is likely to involve the development of irregular areas in our complex urban environments.

Studies that seek to understand urban planning as a product of the city’s energy and material flows are not new. Urbanism has been studying the relationship between built space and the socio-economic forces that shape the city for some time. In Space Syntax, Bill Hillier [

19] (p. 120) calls the relationship between the structure of the urban network and the density of the movements that flow along its lines the ‘principle of natural movement’. Based on the

configurational modelling of space, he proposes to capture the complexities of urban form through the formal patterns that show places as the product of interactions between flows and, reciprocally, how the design of places influences the formation of social and economic flows. In 1965, Abel Wolman introduced the term ‘metabolism of cities’ with reference to the sum of the processes and transformation of material resources and energy, often measured through flows within an urban system, inspiring other methodologies to investigate the material metabolism of anthropogenic systems in a perception of the city as an ecosystem and a living organism. Castells generically calls urban spaces of exchange ‘space of flows’.

The ‘chaos theory’ was developed from the recognition of the need to study the degree of disorder or uncertainty and the irregular and unpredictable temporal evolution of many complex linear and non-linear systems. Chaos theory describes the qualities of the point at which stability moves to instability or order moves to disorder [

20]. This interdisciplinary area of scientific study argues that within the apparent randomness of chaotic complex systems, there are underlying patterns, interconnectedness, constant feedback loops, repetition, self-similarity, fractals and self-organisation (Fractal Foundation.

https://fractalfoundation.org/resources/what-is-chaos-theory/ (accessed 12 January 2025), all of which are elements that reveal connexions with theoretical and technical concepts of entropic urbanism.

In our complex urban environments, understanding the entropy that occurs in informal urban settlements can provide a ‘new paradigm’ for creating more liveable yet less ordered cities [

21]. It is, therefore, of interest to know the ‘idealised urban model’ of the informal city and how it can be a solution/option for public city policies, knowing the information it carries at the level of its spatial entropy + social entropy. The aim is not to control it, but to create strategies that allow urban planning to ‘flow’ in the language and imagery of informal construction.

5. The Construction of the Ideal City Based on Urban Utopias

Despite the dramatic human condition that characterizes slums and informal settlements, it is challenging to understand how these settlements can be adopted as a living space for so many and such diverse populations, admitting the interpretation that it is a utopia and an urban idealisation. As Andreas Brück and Kaitlyn Dietz (2014) [

22] state, ‘Cities are (and always will be) ‘making themselves’ so the imagined utopias will never be achieved. Only in retrospect will we know and understand what kinds of ‘urbanity’ we have been producing. However, it is valid and useful to discuss visions and scenarios today, as if they could produce tomorrow and reflect the hopes and fears of today’s societies, their predictions and their doubts’.

We have always dreamed of better societies. Philosophers, poets, reformers, architects and artists have imagined them in intricate detail, from Asia to the Americas, across Europe, Africa and the Arab world.

In the theoretical and conceptual universe of urbanism, the concept of the ideal city is normally associated with political-philosophical utopian constructions of a rational and geometrically formulated space, where a society that tends towards perfection dwells. In classical literature, these ideal cities are located on islands of distant ‘oceans’ isolated from the reality and time in which the authors who imagined them lived. This is what happens with the ring islands of Plato’s Atlantis (428–347 B.C.), a possession of Poseidon and his descendants, as well as Thomas More’s

Utopian Republic (1516) or Francis Bacon’s

New Atlantis (1627), both founded on legendary islands in the South Seas. Jean Andreae (1619) [

23] (p. 27) tells us of an ‘academic sea’ where, after an imaginary shipwreck, he was thrown to the island of ‘Caphar Salama’ on which the

Republic of Christianopolis was built. As Lewis Munford wrote, ‘They are enchanted islands, and to remain on them implies losing the ability to face things as they are’.

The aspiration to an ‘ideal form’ of city finds its most significant expression in the Renaissance. To Norberg-Schulz, the Renaissance city became an object of scientific study and ‘several architects published treatises that analysed the problems of the city and proposed to define ‘ideal plans’ (…) the ideal city no longer expresses a communal form of life, like the city of the Late Middle Ages, but constitutes the centre of a small autocratic state’ [

24] (p. 116). Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), in

L’Architettura, stated that ‘the city which has a circular plan will be the most capable of all’ [

25] (p. 155). Francis Ching emphasizes this idea of Alberti’s ideal plan by noting that ‘the design of Renaissance churches and the design of ideal cities are very similar, as if the prototype of the city were its temple’ [

26]. This programmatic and geometricised manifestation of urban space is parallel to the static tendency of utopias resulting from a conception of life, which is also static and fixed according to an order represented in the design of the city. It is a tradition that ascends in time to the ideal Greco-Roman city, based on the Hippodamian model on which these civilisations colonised and territorialised the entire Mediterranean and Middle Eastern world.

Other utopias are located in the middle of the countryside. It was there that Tommaso Campanella’s

Civitas Solis (1602) was implanted and much later, already in the face of the emergence of the industrial world, the ‘social utopians’ such as Robert Owen’s

New Harmony (1820) and James Buckingham’s

Victoria (1849), as a first response, albeit a reforming one, to the need for collective housing. To Marques Bessa, these utopian approaches consisted of the ‘reduction of the city to the level of the polymorphic village, on whose consistency will depend the redemption of global society (...) and whose intimate meaning is more related to the escape from the nascent industrial world than to an adhesion and commitment to the social construction of its time’ [

27] (p. 103).

Returning to the urban environment of the 19th-century industrial city, Charles Fourier’s Phalanstery is perhaps one of the first architectural structures of collective housing appropriate to house the community life of social groups he called ‘Falange’ (1822). This idea was indissolubly associated with the realisation of an analogous concept to the Familistery of Guise, by Jean Baptiste Godin (1854), intended to house about 1150 people, who could move between public and domestic spaces always under covered galleries, without worrying about weather conditions.

These political-philosophical constructions, characterised by the desire to create an order that is too inflexible and the imposition of a system of government that is too centralised and absolute, usually corresponds to a geographical configuration of the city that unifies and confers homogeneity to the empirical space. Despite its ideological and formal limitations, the utopia of an ideal city and an ideal society ‘designates either complete madness or absolute human hope’ [

23] (p. 9). Richard Sennett argues that our preoccupation with order is an attempt to restore the myth of a ‘purified community’ and an effort to keep unknown and disorderly events at bay, which explains, at least in part, the rise of urban utopias [

12].

6. The Informal City as Idealisation of an Urban Model

The urban phenomenon of informal settlements should be understood as a consequence of the interaction of a diverse set of factors that have been analysed in numerous technical, scientific and academic studies. We are interested in contrasting and testing the model of the informal city, as an urban idealisation, based on aspects that are close to the guiding principles of utopian cities. This approach allows us to identify some of the common elements as well as to understand some of the main differences between the informal city and the ideal city outlined by the utopians, i.e., idealised objectives in the utopian city present and/or absent in the informal city.

It was not considered as an appropriate methodology to take the formal city as a reference, since few similarities can be found for comparative analysis. On the other hand, the imaginary of the utopian city provides a much more challenging field of analysis to test the model of the informal city, sometimes no less utopian.

6.1. The Design of the City: Urban Self-Organisation

Urban self-organisation was one of the evolutionary principles of the pre-modern city. Its social function was interrupted when modern society introduced a new institutionalised model of urban planning—born with the need to manage the land regime, solve the health-sanitary problems of rapidly growing cities, rethink space according to mobility and structural efficiency or to the exponential demand for housing, which became the form of space control and government of cities [

28].

Informal settlements are clear examples of complex subsystems operating within the general urban system of which one of the distinctive elements, and an objective of study to be developed, is its process of self-organisation. In informal settlements, urban self-organisation corresponds to practices of the reappropriation (of space) that are often replacing the role of local policies and, in some cases, promoting illegal/informal actions in a context where institutions are losing financial capacity, as well as accountability [

29].

This model of community based on self-organising governance, often referred as a ‘Self Organising Collective’ (SOC), is particularly evident in its approach to the problem of the access to housing. The SOC teaches us about the contribution of civil society to public policy reform, with what we can designate an ‘architecture of survival’, sustained by a philosophy of poverty that Yona Friedman talks about and poses several simple but strong questions:

Who has the right to decide on architecture?

How can this right be ensured for the person to whom it belongs?

How can we do this in a world that is heading towards increasing poverty?

How can we act in the face of these prospects? [

30] (pp. 11–12)

Answers to these questions, at least partially, can be obtained from this self-organisation logic that give us critical elements for the development of exploratory analyses at the project level on its organisational concepts and its basic and practical notions of informal design (architectural/urban). In addition, it incorporates the people participation, being elaborated to respond to the opportunities and to the needs of the populations for whom the design is intended.

Utopian cities are designed for the society that must come to inhabit them. It is a pre-conceived city, planned, before it is occupied. The informal city of slums is also tailor-made for the people who will inhabit it, but it differs from the utopian city and the formal city by being built and inhabited simultaneously. It is not a preconceived city. Both the utopian city and the formal city configure environments that are the result of designed ideas, planned before being manufactured. The demands of mass production, says E. Larrabée, leads to order at the expense of variety [

31].

Christopher Alexander believed that the assumption of these concepts is wrong, namely, what concerns housing. In The Production of Houses he argues that it is possible to develop ‘an entirely different process of housing production, which allows the construction of houses in large quantities, but houses that are deeply rooted in the psychological and social nature of the environment, that are rooted in the personal character of the different people and different families that live there’ [

32] (p. 23). Despite its precarious construction, the ‘architecture of survival’ proposed by Yona Friedman, responds in some way to two fundamental needs for any society: the recognition of the fact that each family and each person is unique, and should be able to express this specificity; and the recognition of the fact that each family and each person is part of society, and requires spaces for association with other people [

32] (p. 24). In many cases, due to their shared origins, neighbourly relations, community engagement and intense use of common spaces, informal slums constitute a community able to provide identity and representation to its living spaces.

6.2. The Design of the City: The Informal City Is Not a Medieval City

As we mentioned earlier, the design of the ideal, utopian city is based on the concept of the ‘ideal form’ and the ‘ideal plan’, which corresponds to a rigorous, unifying and homogeneous geometry. In the case of the informal city, the idealisation of its urban design presents an apparently ‘disordered’ image, radically different from the rigorous and geometric image of utopian cities.

Several authors tend to understand the dynamics and complex diversity of the physical and morphological characteristics of informal settlements as being similar to the characteristics of the urban fabrics of historic European centres [

33]. This similarity is also attributed to the process of urban self-organisation that accompanied the evolution of pre-industrial cities.

Although the medieval city is presented as a model of entropic urban planning, the informal city is not a medieval city. Simply comparing their urban fabrics and urban self-organisation is not a sufficient argument to establish a correspondence between the two forms of land use and occupation. Several aspects distinguish them, of which we give some examples:

The long, secular time of formation and evolution of the medieval city, where the concept of ‘permanence’ is an urban constant, contrasts with the short time of the ‘instantaneous informal city’ whose structure is in almost daily mutation and transformation.

The spatial order of the medieval city is concomitant with the presence of various social classes: the nobility, the clergy and the people, all represented in their palaces, churches and houses [

34] that form a coherent and territorially integrated urban ensemble. Such social integration tends not to occur in the informal city, characterised by its homogeneous, low-income population, often living in a situation of urban exclusion (no go areas) and social marginalisation in relation to the formal city.

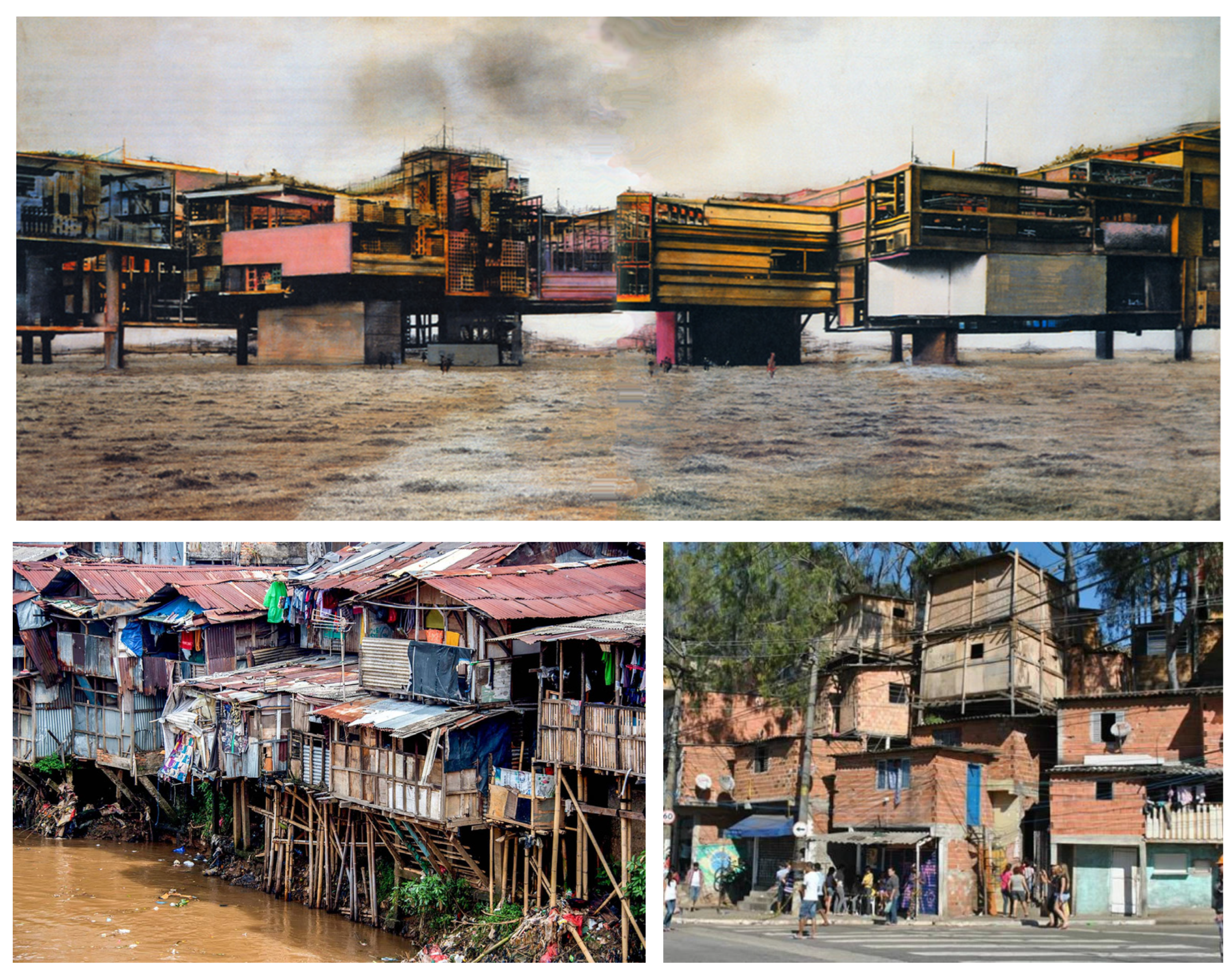

In the medieval city, public space (squares and streets) + sublime architecture (palaces, churches) + public art (fountains and sculptures) + anonymous architecture (houses and shops) forms a morphological unit that supports the heritage value of its culture and the symbolic system of its urban identity (

Figure 2). The sublime in architecture is supported by ‘anonymous architecture’, the ‘architecture of everyday life’ that serves as a background image and field of aesthetic contextualisation. This doesn’t seem to be the case in informal settlements, given the uniformity of their urban morphology, usually without architectural reference elements, although the constantly changing ‘anonymous architecture’ provides a continuous redesign of the complex landscape that characterises them.

6.3. The Emergence of a New Urban Image Aesthetic

In the various urban proposals of the utopians, the houses are two or three storeys high, with the highest buildings destined for palaces and temples. In

Cristianopolis, Jean Andreae (1619) refers that all the buildings have three floors, connected by common staircases [

35]. Likewise, the informal city is not verticalised—a situation that clearly distinguishes it from the formal city, where high-rise construction is a common denominator. Several factors affect high-rise construction in informal cities such as the precariousness of building materials, the transitory nature of the buildings, low financial resources, the rugged terrain or the geological inconsistency of the sites.

As we mentioned earlier, the geometrisation of space is a constant in utopian cities. Their houses adopt a predefined formal model of standardised typologies to be adopted by all the city’s residents. In contrast, the housing constructions in the informal city do not appear to follow any geometric pattern. Their fragmented image and complex composition reflect, above all, the same entropy that characterises the formation of urban space.

The type of housing is perhaps the factor that best explains the formation of this ‘new architecture’ and the correlation between the utopian ideal and the solution that the informal city seems to have found for its residents. The informal city is predominantly a city of single-family or multi-family houses, but not of collective housing buildings. In some proposals for the ideal utopian city, collective housing is proposed, but single-family housing is the predominant typology—the same is true in the informal city, even though it acquires various types of morphologies and the intertwining of spaces and modes of land occupation.

All these configurational aspects of the informal city have given rise to a new aesthetic of architecture and urban image. ‘Free from monolithic aesthetic ideas people project their personality onto their homes’ [

36].

We would venture to say that there is a simultaneously utopian and futuristic dimension to this aesthetic, something comparable to the concept of NEW BABYLON (1959–1974) designed by Constant Nieuwenhuys (

Figure 3), who described it as an ‘anti-capitalist city of infinite play’, an infinite spatial play associated with the flexible architecture of its buildings.

6.4. The Just City: The Right to Property and to Housing

Peter Marcuse [

37] argues that the ideal city must certainly be a just city, although this is not a sufficient definition: ‘Achieving justice is a step on the road to the ideal city, but not the final destination of that road.’

Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘everyone has the right to property, individually and collectively, and that no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property’. One of the most pressing issues facing informal city dwellers today is regularising access to property. This aspect is directly linked to the problem of the right to adequate housing. The question of property is a key issue when it comes to the informal city. The informal city is a project of private action and in this sense, property acquires critical importance for its own functioning and urban structuring.

The basic principle of the various urban utopias is the link between the idea of common property and the idea of justice, i.e., the proper distribution of rights and duties among citizens. In

Utopia (1516), Thomas More (1478-1535) defends the thesis of common property in an imaginary dialogue with Rafael Hitlodeu (Rafael Hitlodeu was born in Portugal and, driven by the desire to see and get to know the most distant regions of the world, he joined Vespucci (Born in Florence 1451) and visited America shortly after Christopher Columbus; Thomas More was inspired by the accounts of his travels to describe Utopia): ‘I am fully convinced that there can be no equitable and just distribution of wealth, nor perfect happiness among men, unless property is abolished’ [

38] (p. 57). He goes on to explain how this notion of co-ownership works: ‘Each house has two doors (...). These doors have no locks or padlocks (...). Anyone can enter, because there is nothing inside the houses that belongs to individuals (...). Every ten years, they change houses, picking the one that suits them’ [

38] (pp. 66–67).

Unlike the utopian city, property is not a given from the outset. Although revolutionary, the collectivisation of property is not a viable political option. Where it has occurred, such as in Mozambique, it has not helped to resolve the precarious occupation of informal settlements. However, access to property, and, therefore, access to housing, is a stepping stone to access to power and equality. Some strategies are being instrumental in transforming this critical reality. We highlight two of them, currently being implemented:

Community land trusts (World Economic Forum.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/community-land-trust-housing-access/ (accessed on 15 January 2025))—in a community land trust, the land is owned by a private, non-profit corporation, managed collectively by residents, community stakeholders and experts. The individual houses built on this land are owned by residents who, when they choose to leave, sell their house at an affordable price to the next buyer.

Urban Land Regularisation (REURB) (The Ministry of Cities, Law no. 13.465, 2017.

https://www.gov.br/cidades/pt-br/assuntos/publicacoes/arquivos/arquivos/cartilha_reurb.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025))—in 2017, the Brazilian government decided to implement a project of ‘legal, urban planning, environmental and social measures aimed at incorporating informal urban centres into urban land-use planning and titling their occupants’, with a view to recognising the rights of occupants to, among other things, remain with their building on the occupied site.

As these are territories that are illegally occupied, whether on public or private land, land re-regularisation is difficult to implement legally, which is accentuated by the complexity of the urban and architectural structure that characterises informal settlements.

On the other hand, urban property fulfils its social function when its use is compatible with the infrastructure, facilities and public services available, and simultaneously contributes to the well-being and development of the population as a whole. These aspects are crucial in the regularisation process in order to prevent the ‘taking of possession’ from ‘crystallising’ erroneous situations that hinder or prevent the future development of the city, which is seeking to move from an ‘informal’ to a ‘formal’ city.

6.5. Urban Infrastructure: Shortcomings and Adversities

For ideal cities, the theme of the quality of urban infrastructure and public spaces is a common denominator to which their creators pay the greatest attention.

In Plato’s Atlantis, good infrastructures, public services, collective facilities and various other monumental constructions were imagined for the circular city, because ‘on each of these ring islands they built several temples for different gods, and many areas for exercise, some for men and some for horses’ [

39] (p. 140). In More’s

Utopia, ‘the streets are attractive and have been conveniently laid out and orientated, both for transport needs and as protection from the wind’ [

38] (p. 66). In

Cristianopolis, ‘spring water and running water can be found in abundance, taken from natural wells or brought by pipelines. The exterior is pleasant, without extravagance, clean and without decay’ [

35].

In the urban idealisation created by informal settlements, the absence, insufficiency or precariousness of infrastructure and equipment represents the greatest weakness and threat to their urban sustainability. The low availability of drinking water supply and adequate sanitation, whether private or shared, for a reasonable number of users, is the most visible facet of this type of urbanisation. The informal city is not made for the car and other modern means of mobility. This creates enormous constraints for the movement of goods and people, access to work and the circulation of emergency vehicles.

Urban greenery is also not a characteristic of the informal city: ‘while upscale neighbourhoods have trees on the pavements, squares and parks, adding financial value to the neighbourhood, its houses and buildings, on the outskirts this is not the case. (...) In most cases, the scarcity of green areas is due to a lack of planning and not a lack of space’ [

40] (p. 28). However, in many cases, this occupies the agricultural and forestry land surrounding the formal city.

These shortcomings and adversities contrast with the ideal city model and are an urban phenomenon that can be understood as the consequence of a diverse set of factors that need to be analysed and probably resolved by identifying good practice experiences that can be adjusted to the respective social, cultural and territorial context of each place.

The infrastructural constraints and shortcomings explain the poor resilience of the informal city in the face of the impact of the climate crisis, which often proves fatal to the lives of its inhabitants. The precarious urban infrastructures that generally characterise informal settlements are perhaps one of the most difficult and complex technical and conceptual challenges facing the development of entropic urbanism.

6.6. The Formation of a Dual Society

In the logic of the urban utopia plan, an ideal city also corresponds to an ideal society that rejects or reformulates the social and governing codes of the traditional city. These are attempts to pose a social engineering problem in which society is reshaped to inhabit rural utopias outside of polluted and degraded urban centres.

Informal territories are essentially spaces of multiple existences that carry a strong image of their residents’ own vision of the notion of urban space. For this reason, their urban fabric has often been compared to other types of popular settlements. Perceived today as an urban phenomenon,

favelas were considered during the first half of the 20th century to be a veritable ‘rural world in the city’ [

13] (p. 22).

In the morphogenesis of the informal habitat, we find strong references to the rural habitat—which, due to its distinctive nature, provides a way of life that lies between the dichotomy conceived by Ferdinand Tönnies (1887) [

41] between the ‘Community’ (Ge-meinschaft) understood as a living organism and the ‘Society’ (Gesellschaft) as a mechanical aggregation, an artefact, which we normally associate with the way of life in the formal city. The distinction between these two cultural realities is more complex if we take into account that the inhabitants of the informal city maintain working and business relationships with the formal city, which we could identify, with the appropriate contextualisation, with another concept related to the transition from rural to urban societies, a dichotomy that in 1941, Robert Redfield called ‘The Folk-Urban Continuum’ [

42].

This ‘Folk-Urban Continuum’ concept seems to illustrate the society that inhabits informal settlements [

43]. Solidarity-based community protection networks characterise the lives of people living in informal settlements and show a significant proximity to interpersonal and community relations in small towns, certain types of neighbourhoods and workers’ villages and rural villages, where a stable link between social and territorial cohesion is often established.

7. Discussion

The development of a new interest in informal cities can not be explained only by their identification with ‘territories of violence’ that exist there, but it also occurs in formal cities [

15]. Theorising disorder can be seen as an outgrowth of the writings of the influential Chicago School sociologists of the mid-20th century. In Great American City, Robert J. Sampson presents the fruits of over a decade’s research in Chicago where the crime of ‘broken windows’ and other signs of disorder have been taken as symptomatic of city life [

44] (p. 121). ‘Social disorder is usually understood as public misbehaviour that is considered threatening, such as verbal attacks, overt solicitation of prostitution, public drug addiction, and boisterous groups of young men on the streets. The physical marks of disorder typically refer to ‘graffiti’ on buildings, abandoned cars, rubbish in the streets, and the proverbial broken windows’ [

44] (p. 121). Disorder can also be defined in terms of perceptions of decay (and) the poor are condemned to the sensate realm of decay, a consequence of being left behind, of being forgotten [

45].

Ever since informal settlements began to appear in cities, their existence has been the subject of intense debate, with the dilemma of whether to maintain and/or remove them. The issue is neither peaceful nor easy to resolve.

In Europe, both society and political decisionmakers tend to opt for their removal: ‘HOUSES YES SHANTIES NO’, was the slogan acclaimed in the post-revolutionary period of April 1974 by those demonstrating for access to adequate housing, as it was in Portugal with the Special Rehousing Programme (Decree-Law 163/93), the mission of which was eradicating the ‘shantytowns’.

In other regions of Asia, Africa and Latin America, the options have been different, usually focussed on transforming and upgrading informal settlements, since their metropolitan scale and the immense population living there make no other political decision or financially sustainable solution feasible. For them, informal settlements are not a problem, but rather a solution that must be ‘rescued’ and integrated into the life of the city.

The cultural and social specificities of the populations that inhabit information spaces and their correlation with a certain type of housing need to be better understood and studied by both urban sociology and urbanism. This is a reality that ‘materialises’ a certain urban utopia that has been touted as a solution for improving the quality of life in the context of the so-called ‘advanced capitalism’ that defines the socio-economic development model of contemporary society.

Faced with a housing crisis that is proving to be global, the issue of slums is once again at the centre of national and local governments’ attention.

Figure 1 shows the scale of this phenomenon and its upward trend.

It is, therefore, a challenge for researchers in the field of spatial science to study and analyse an urban model that is built on logics of occupation and land use that we know little about and that give rise to complex spatial, volumetric and chaotic morphologies and mutant interstitial urban structures of which we still have a very uncertain notion.

8. Conclusions

The objective of this paper is to explore the potential of the utopian imaginary, and to submit old and new utopian models and discourses to analysis and critics of the informal city that unleashes new progressive energies as it cuts the ‘functions’ of structural and ideological urbanology, reshapes historical realised communities and inspires social changes by utopian visions.

Alongside many other articles published on these themes, and based on the questions initially posed, this text is, above all, an appeal to the imaginary that is or may be at the root of the formation of informal settlements and, at the same time, a challenge or a way of provoking debate on the concept and form of inhabitation, once again, as a response by society to the inadequacies of the state as the holder of the right to manage and plan the territory.

The space of the informal polis is, above all, a space for the biological survival of people with basic needs. We all inhabit and finding a shelter is a crucial factor for this survival. The construction of the informal city responds overall to that need of survival and seems to be the result of a collective intelligence, which we could consider natural for all gregarious populations, perceived and imagined in the context of historical and political values that allow us to explain its emergence and permanence in time and space.

This paper is an intellectual approach, a starting point for further research into informal cities with the aim of understanding this urban phenomenon. It has also the purpose of understanding the phenomenon of formal suburban areas where ‘spatial order’ is not evident in face of their complex and often chaotic urban structure, by rethinking these regions not as peripheral extensions but as integral components of a sustainable urban fabric.