Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Space and Planning Base on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Theory: A Case Study in Zhuma Township, Zhejiang Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Study Subjects: Zhuma Township

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Origin and Development of “Social-Spatial” Relationship Theory

2.2. Rural Public Cultural Space in “Social-Spatial” Relationship Theory

2.3. Connection Between Local Culture and Rural Cultural Space

2.4. Research Gaps and Purpose

3. Research Methods and Theoretical Analysis Framework Construction

3.1. Research Methods

3.1.1. Qualitative Research Methodology

3.1.2. Cross-Disciplinary Analysis

3.1.3. Field Research Method

3.1.4. Case Study

3.2. Theoretical Framework Construction

4. Analysis Results: Interpretation of the Zhuma Township Case Phenomenon

4.1. Transformation of Camellia Culture in Zhuma Township

4.2. Reshaping of the Public Cultural Space of Zhuma Township

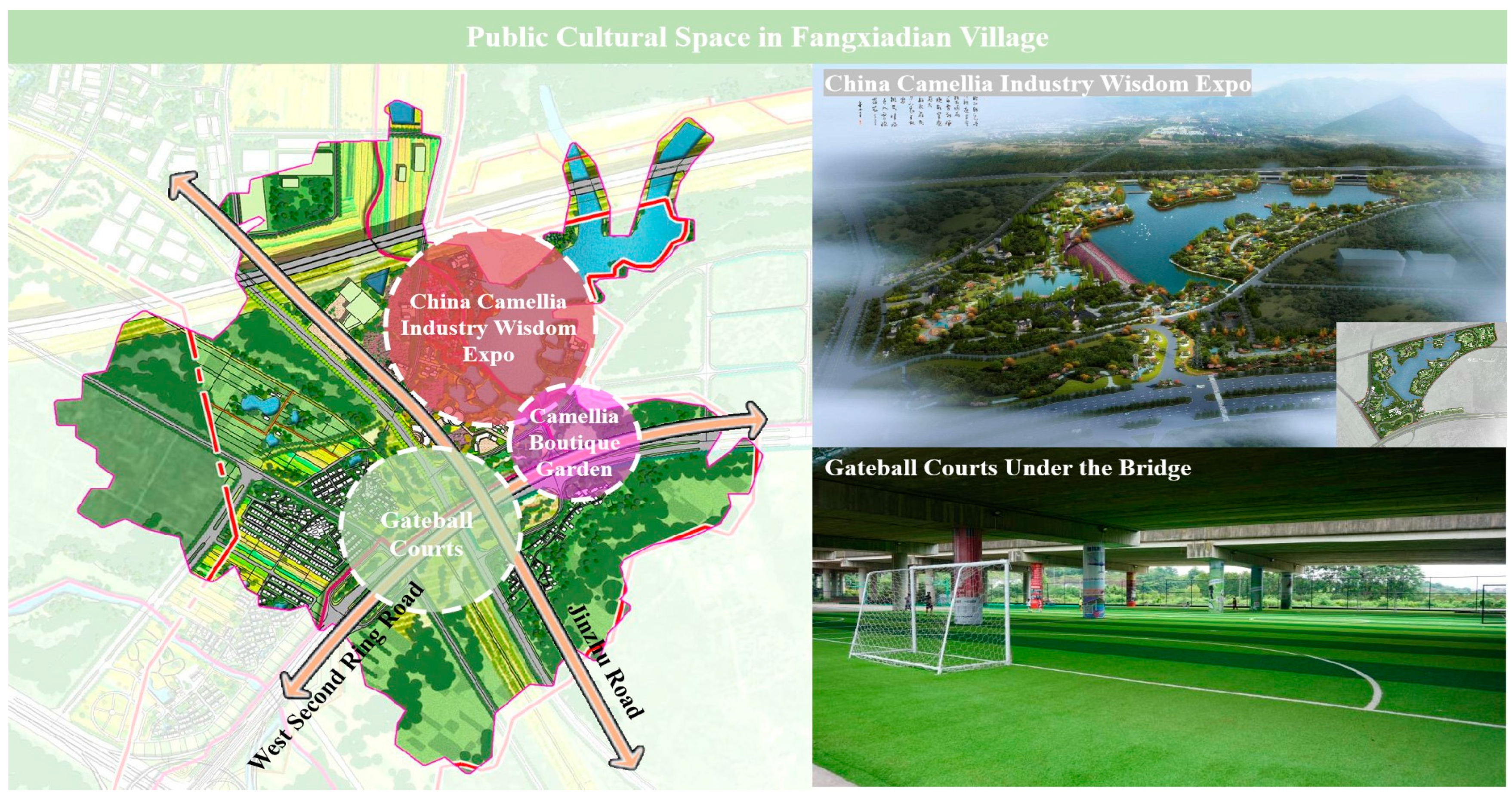

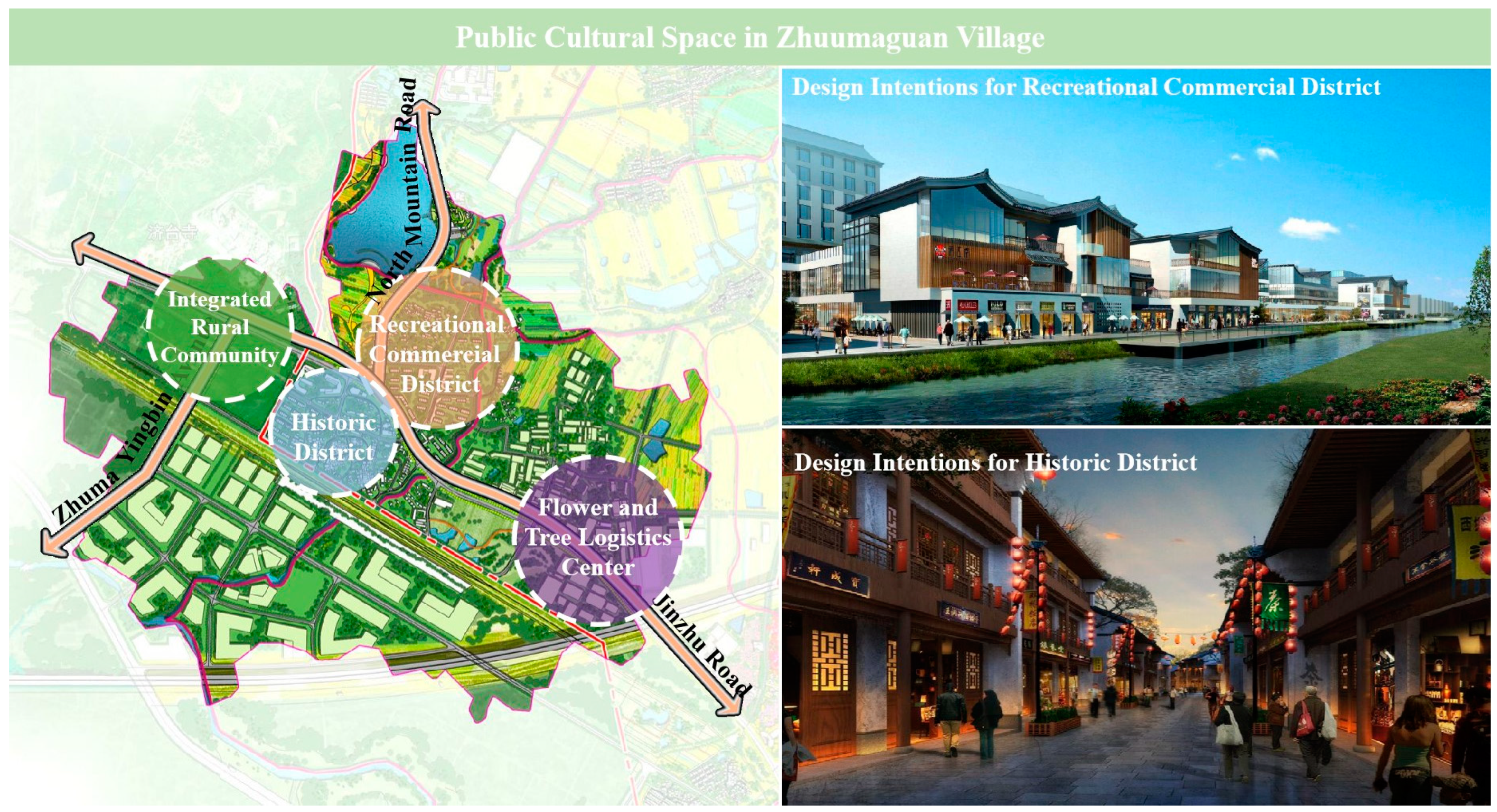

5. Discussion: Mechanism Argumentation and Sustainable Planning

5.1. Rural Public Cultural Space Production

5.2. Representation of Rural Public Cultural Space

5.3. Space of Representation in Rural Public Culture

5.4. Design Strategies for Reconstructing Rural Public Cultural Spaces

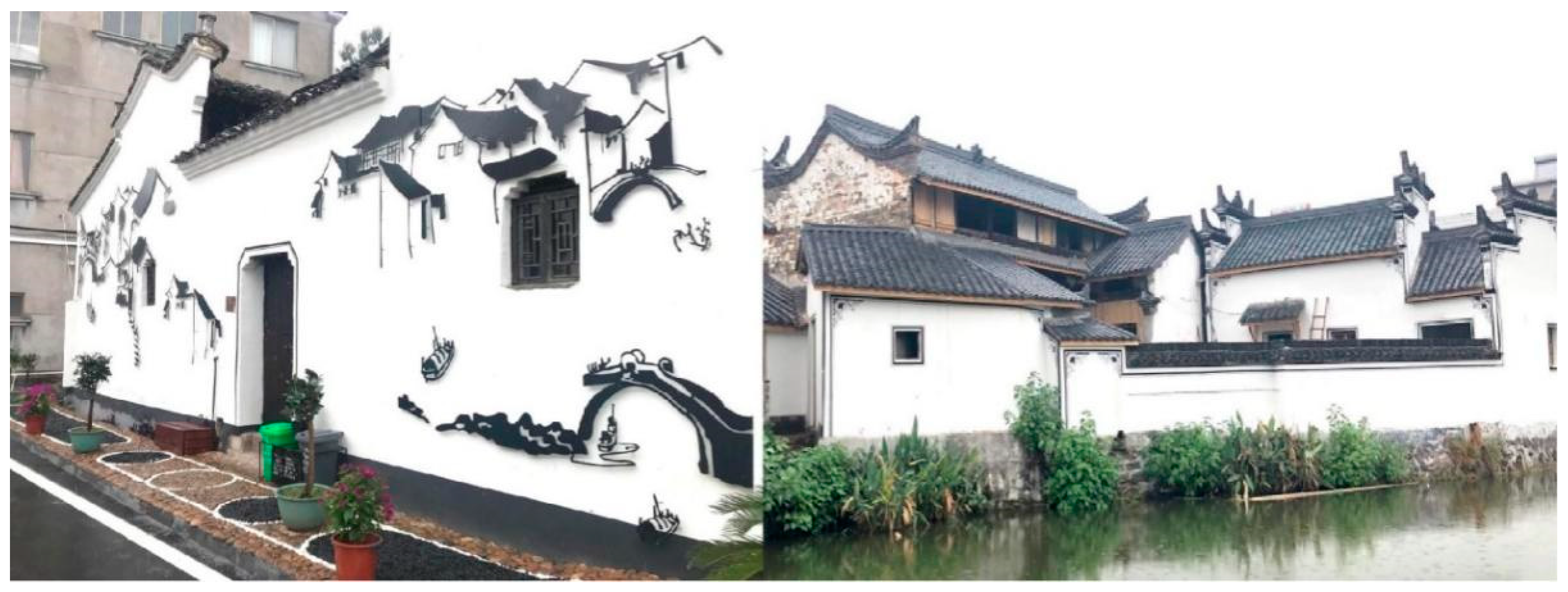

5.4.1. Inheritance of Style and Regeneration of Functions

5.4.2. Connotation Reshaping and Cultural Value Addition

5.4.3. Role Reversal and Collaboration

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Month | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | Yearly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical highest temperature (°C) | 24.3 | 27.4 | 32.6 | 32.9 | 36.4 | 37.5 | 40.5 | 39.3 | 39.6 | 35.3 | 31.3 | 23.8 | 40.5 |

| Average high temperature (°C) | 9.1 | 10.9 | 14.8 | 21.7 | 26.5 | 29.2 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 28.5 | 23.6 | 17.9 | 12.3 | 21.8 |

| Average daily temperature (°C) | 5.2 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 17.1 | 21.8 | 25.1 | 29.0 | 28.6 | 24.1 | 18.9 | 13.2 | 7.4 | 17.3 |

| Average low temperature (°C) | 2.2 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 13.3 | 18.2 | 21.9 | 25.3 | 24.9 | 20.8 | 15.3 | 9.4 | 3.8 | 13.8 |

| Historical lowest temperature (°C) | −9.6 | −8.9 | −1.6 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 13.3 | 18.8 | 18.6 | 13.1 | 2.4 | −2.7 | −6.8 | −9.6 |

| Average rainfall (mm) | 71.5 | 91.6 | 160.1 | 168.9 | 186.6 | 258.5 | 129.5 | 109.1 | 103.1 | 68.9 | 55.9 | 47.9 | 1451.6 |

| Average number of precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13.4 | 14.5 | 18.5 | 17.1 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 12.4 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 9.6 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 158.0 |

References

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable Development Levels and Influence Factors in Rural China Based on Rural Revitalization Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Rural innovation system: Revitalize the countryside for sustainable development. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wennersten, R.; Mulder, K. Challenges for Sustainable Development in China; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Long, H. Transformation of rural China. In The Geographical Transformation of China; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 118–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, S.Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, T.Z.; Huang, L.S. The Construction Mechanism and Practice of Characteristic Industrial Villages from the Perspective of the “Society-Space” Relationship, Taking Zhuma Township, Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province, as an Example. Buildings 2023, 13, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Qian, Z.; Wang, Z. Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Leisurely and Experiential Rural Habitat Environment under the Perspective of “Spatial Production” Theory. Archit. Cult. 2020, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maycroft, N. Understanding Henri Lefebvre: Theory and the Possible. Cap. Cl. 2005, 29, 170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Interpretation of spatial theory: Based on the perspective of human geography. Hum. Geogr. 2011, 26, 15–18+139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; The Commerical Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, K. Trial by space for a ‘radical rural’: Introducing alternative localities, representations and lives. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture (3 Volumes); Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.P. Transnational Urbanism: Locating Globalization; Blackwell Publishers: Malden, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. Spatial Data Analysis with GIS: An Introduction to Application in the Social Sciences; UC Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X. Research on rural cultural space reconstruction based on the theory of space production. E3S Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2020, 189, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. World Heritage listing and the globalization of the endangerment sensibility. In Endangerment, Biodiversity and Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y. Exploration of rural development paths under the perspective of cultural space theory: Taking Zhujiayu Village in Zhangqiu City, Shandong Province as an example. Urban Dev. Res. 2016, 23, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Extraordinary landmark in the protection of intangible cultural heritage of China. Queen Mary J. Intellect. Prop. 2011, 1, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M. Basic Principles of Sustainable Development; Working Paper 00-04; Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University: Medford, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pradinie, K.; Navastara, A.M.; Martha, K. Who’s Own the Public Space?: The Adaptation of Limited Space in Arabic Kampong. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D. The ‘publicness’ of suburban gathering places: The example of Podkowa Lena (Warsaw urban region, Poland). Cities 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markeyvch, I.; Smith, M.P.; Jochner, S. Neighbourhood and physical activity in German adolescents: GIN plus and LISA plus. Environ. Res. 2016, 147, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shores, A.; West, S.T. Rural and urban park visits and park-based physical activity. Prev. Med. Int. J. Devoted Pract. Theory 2010, 50, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yansui, L.; Yuheng, L. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Jaszczak, A.; Ukovskis, J.; Antolak, M. The Role of Rural Renewal Program in Planning of the Village Public Spaces: Systematic Approach. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2017, 39, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. Contesting the Irish Countryside: Rural Sentiment, Public Space, and Identity. Nat. Cult. 2009, 4, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Weakening of public cultural space: The “weakness” of rural cultural revitalization. People’s Forum 2018, 21, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Liu, Q.; Huang, N. Path Model and Countermeasures of China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2020, 70, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, G.; Cao, Y. Does land tenure fragmentation aggravate farmland abandonment? Evidence from big survey data in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Ye, J. China’s Peasant Agriculture and Rural Society: Changing Paradigms of Farming; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xuefeng, H. New rural construction and the Chinese path. Chin. Sociol. Anthropol. 2007, 39, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. The significance and realization of rebuilding rural public cultural space. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2011, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Xu, Y.; Hong, B. Inheritance and reconstruction of rural public cultural space under the integration of new media. Mod. Urban Res. 2021, 40–47+55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. The Shaping of Rural Cultural Space and Its Development Policy Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Urban Design, Space and Society; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.-P. The Dilemma and Countermeasures of Rural Culture Construction under the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. South. J. 2021, 10, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Song, Q. Research on public cultural space planning in modern rural communities—Taking Yu Jiabian Village in Jurong City, Jiangsu Province as an example. J. Chin. Urban For. 2016, 14, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Chen, C. White tea industry-driven rural reconstruction and planning revelation--an empirical study based on Xilong Township, Zhejiang Province. Mod. Urban Res. 2019, 07, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Chen, C. Characteristic Mechanism and Policy Implications of Local Industry-Driven Rural Development--The Case of Shanxiahu Town, Zhejiang Province. South. Archit. 2022, 05, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. Research on the Design of Rural Public Space Creation Under the Perspective of Vernacular Culture. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang College of Arts, Urumqi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-C.; Mei, J.-H.; Qin, S.; Zhou, Z.-J. Review of research on cultural inheritance of traditional villages. J. Nat. Sci. Hum. Norm. Univ. 2023, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P. The practical logic and governance of rural public culture. Res. Social. Chin. Charact. 2018, 03, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Research progress and prospects on the reconstruction of rural cultural space from the perspective of rural revitalization. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 38, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, G. The logic of rural space creation—An analysis based on the theoretical perspective of culture and social space. City Plan. Rev. 2018, 42, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, C. Preparatory updates for the Jinhua Conference of the International Camellia Association. Flower Plant Penjing 2002, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Famous camellias gathered to show their beauty—The 16th International Camellia Conference and International Camellia Festival was held in Jinhua. Flower Plant Penjing 2003, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Carry forward the “Camellia Spirit” and successfully host the International Camellia Conference. China Flowers Hortic. 2003, 05, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Where Camellia Blooms—China Jinhua International Camellia Conference and International Camellia Festival were held grandly in Jinhua. Zhejiang For. 2003, 3, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, X. Reproduction of Chinese Rural Culture—Rethinking Based on a Concept of Cultural Transformation. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 17, 119–127+148. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Xie, H. Study on the Spatial Evolution of Rural Culture Driven by Tourism-Based on Spatial Production Theory. J. Hubei Univ. Natl. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 40, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Capital, Power and Place: Research on the Production of Cultural Space in Chengdu. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, S.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, L. Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Space and Planning Base on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Theory: A Case Study in Zhuma Township, Zhejiang Province. Buildings 2025, 15, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050671

Lou S, Chen Y, Feng J, Zhang L. Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Space and Planning Base on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Theory: A Case Study in Zhuma Township, Zhejiang Province. Buildings. 2025; 15(5):671. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050671

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Senyu, Yile Chen, Jingzhao Feng, and Lei Zhang. 2025. "Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Space and Planning Base on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Theory: A Case Study in Zhuma Township, Zhejiang Province" Buildings 15, no. 5: 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050671

APA StyleLou, S., Chen, Y., Feng, J., & Zhang, L. (2025). Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Space and Planning Base on the Perspective of “Social-Spatial” Theory: A Case Study in Zhuma Township, Zhejiang Province. Buildings, 15(5), 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050671