Service Accessibility and Wellbeing in Amman’s Neighborhoods: A Comparative Study of Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Background

2.1. Urban and Residential Services Provision

Services Provision in Amman

2.2. Urban Accessibility to Services Framework

2.3. Wellbeing and Urban Transformation

2.3.1. Urban Wellbeing and Governance

2.3.2. Residents’ Wellbeing and Social Networks

- Positive Emotions: Evaluating the ratio of positive to negative emotions.

- Social Relationships: Analyzing social ties, networks, support levels, and satisfaction with and contributions to support systems.

- Engagement in the Environment: Measuring deep psychological engagement, evidenced by intense focus, whether through work dedication or academic involvement.

- Meaning in Life: Assessing the individual’s life direction and goals.

- Sense of Accomplishment: Evaluating progress toward life goals.

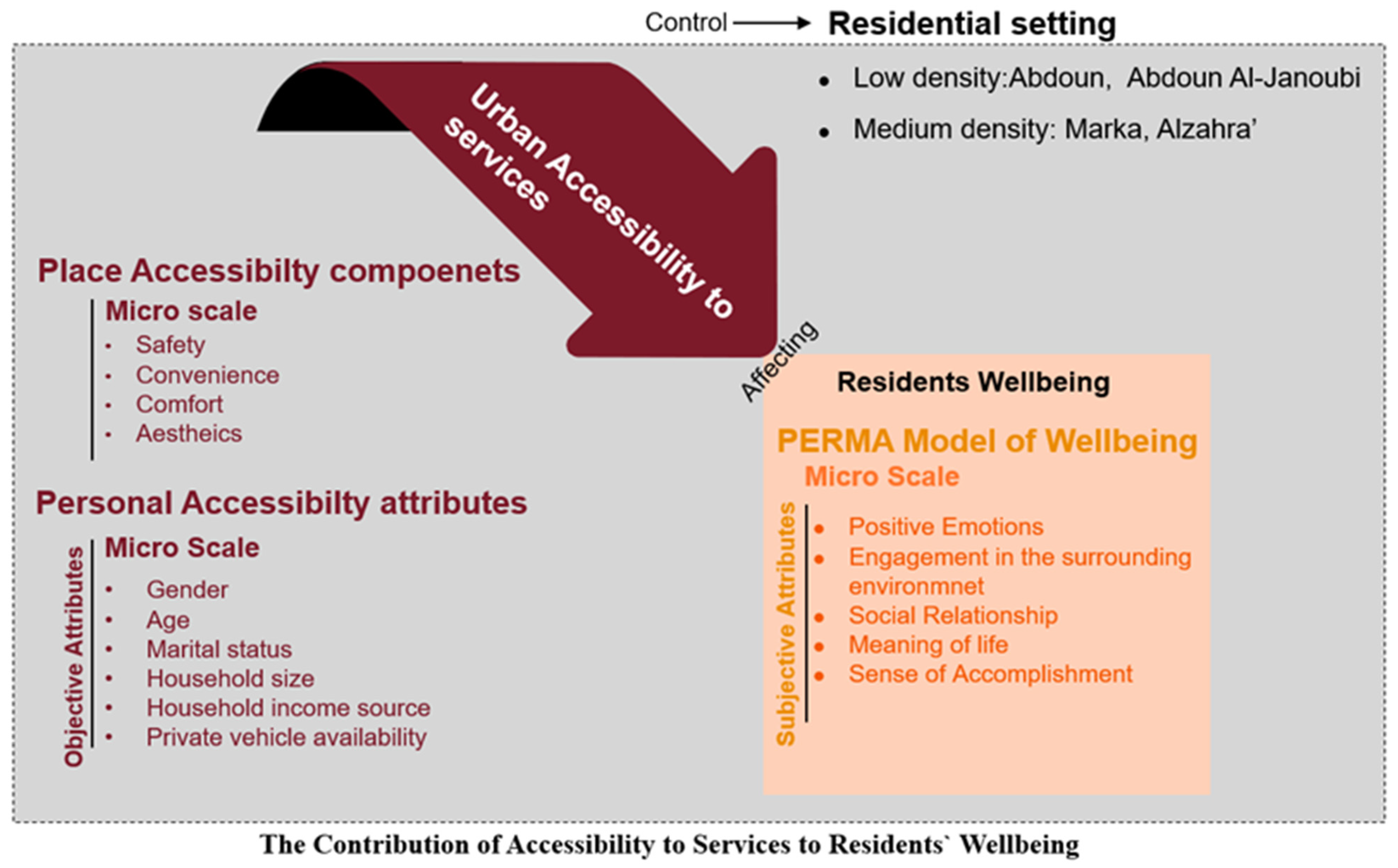

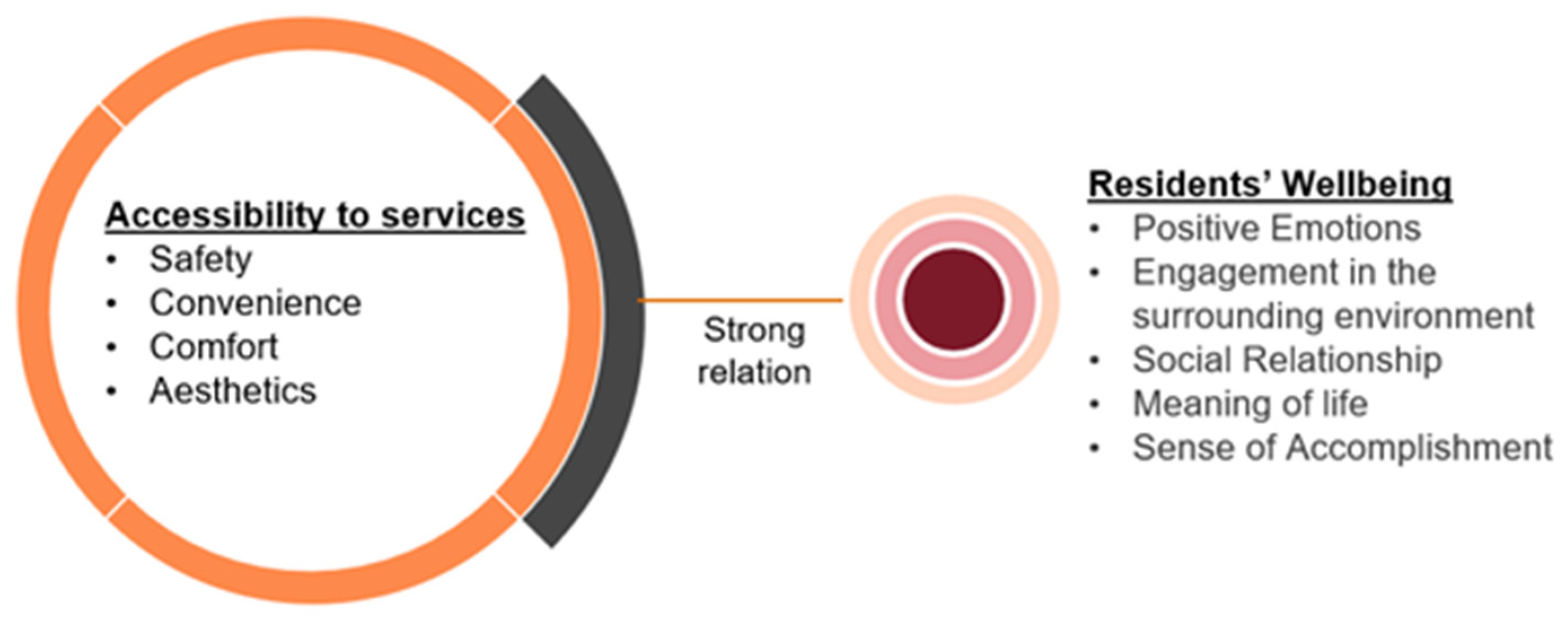

2.4. Conceptual Framework of the Study

3. Research Method

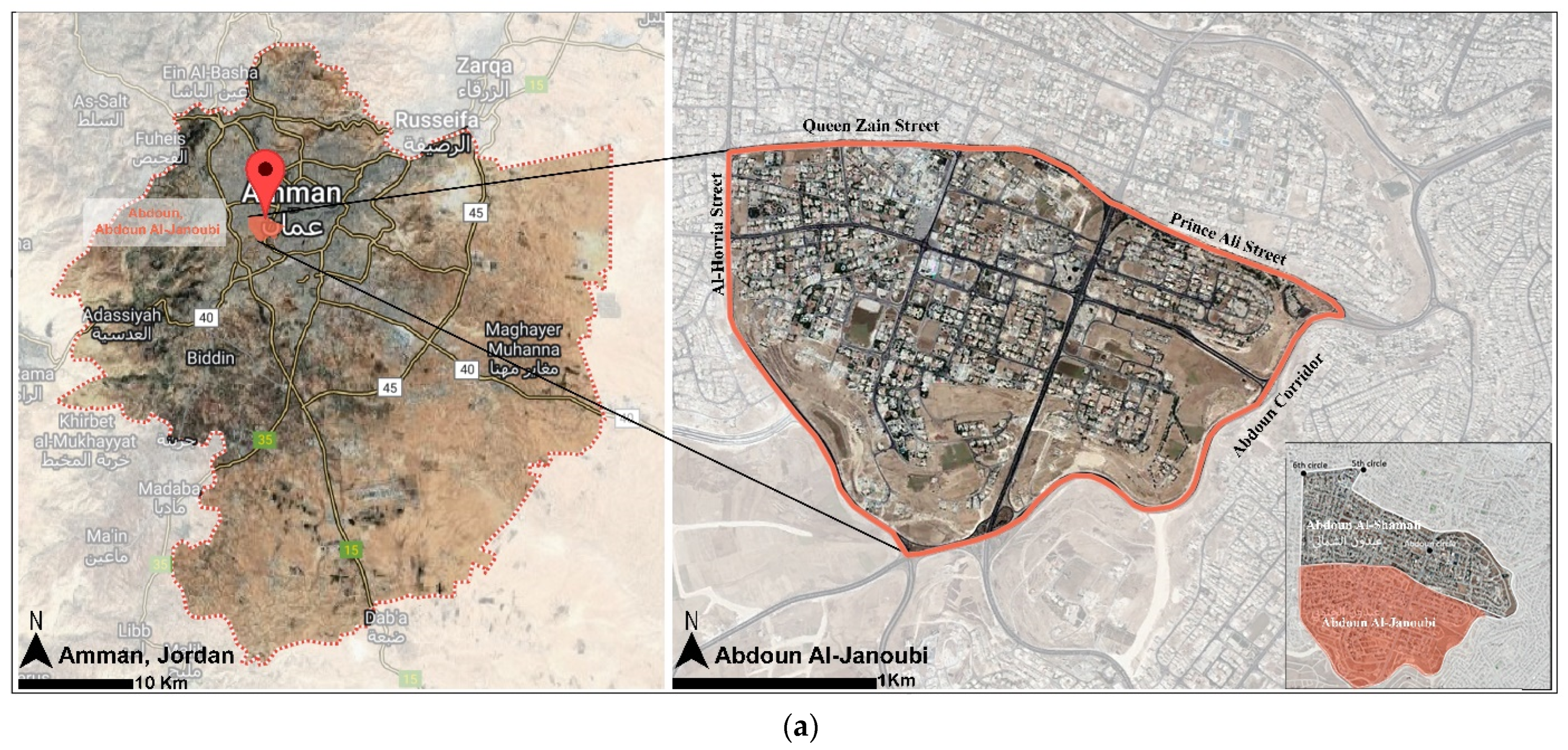

3.1. Research Settings

3.2. Population of Study and Sampling

3.3. Hypothesis of the Study

- Total accessibility to services in different residential urban settings in Amman affects total residents’ wellbeing.

- Total accessibility to services was defined by journey attributes at the micro- level, which were safety, convenience, comfort, and esthetics.

- Total residents’ wellbeing was defined by positive emotions, social relationships, engagement in the surrounding environment, meaning of life, and sense of accomplishment.

3.4. Variables of the Study

3.4.1. Independent Variable

- Safety: Safety was measured by the average sum of the statements of the following six attributes: street lighting provides safety, speed limit and stop signs provide safety, street width provides safety, sidewalks and pavement continuity provide safety, length of walk to services is safe, length of walk to services is safe; Q.8–Q.13.

- Convenience: Convenience was measured by the average sum of the statements the following four attributes: service location is convenient, travel time to service is convenient, parking is available, public transportation is available; Q.14–Q.17.

- Comfort: Comfort was measured by the average sum of the statements of the following four attributes: there are shades on walkways, there are shades for car parking, there are shades at bus stops, there are benches at bus stops; Q.18–Q.21.

- Esthetics: esthetics was measured by the average sum of the statements of the following two attributes: there is a scenery esthetic, available signage is esthetic; Q.22–Q.23.

3.4.2. Dependent Variable

- Positive emotions: these were defined by how high or low the positive emotions were compared to negative emotions. Positive emotions were measured by the average of the sum of three statements, Q.24–Q.26.

- Social Relationships: these were defined by the subject’s social ties, social network, received support, perceived support, satisfaction with support, and giving support to others. Relationships were measured by the average of the sum of three statements, Q.27–Q.29.

- Engagement in the surrounding environment: this was defined by measuring an extreme level of psychological engagement that was characterized by intense concentration and focus. Engagement in the surrounding environment was measured by the average of the sum of three statements, Q.30–Q.32.

- Meaning of life: this was defined by the subject’s life goals and direction in life. Meaning of life was measured by the average sum of three statements, Q.33–Q.35.

- Sense of Accomplishment: this was defined by the subject’s actions towards achieving life goals. Sense of accomplishment was measured by the average sum of three statements, Q.36–Q.38.

3.4.3. Confounding Variables: Socio-Economic Characteristics

3.5. Research Instrument

3.6. Data Collection Technique

4. Research Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Study Variables

4.1.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics

- Residential Setting Typology: Most household heads of the surveyed households were living in residence, making up 32.1% of the total sample. In the Abdoun Al-Janoubi neighborhood, residence A was the most dominant, making up 74.2% of the sample. In the Al-Zahra neighborhood, samples were almost equally distributed among residence C and light industries, as 51.6% of the sample were living in residence C, as shown in Table 1.

- Gender: Most of the surveyed household heads were almost equally distributed between males and females for the total sample. In Abdoun Al-Janoubi, most of the surveyed household heads were males, making 57.3% of the sample, while in Al-Zahra, females dominated the samples, forming 58.1% of the sample, as shown in Table 1.

- Age: Most of the household heads surveyed were distributed among the three age ranges of 18–<30 years, 30–<40 years, and 40–<50 years. The most frequent age range of the total sample was 30–<40 years. In Abdoun al-Janoubi the most frequent age range was equally distributed among the ranges of 30–<40 years and 40–<50 years, making 32.4% of the sample. In the Al-Zahra neighborhood, the most frequent age ranges were 18–<30 years, making up 30.8%, and 30–<40 years, making up 33.7% of the sample, as shown in Table 1.

- 4.

- Marital Status: Most of the household heads surveyed were married, representing 73.8% of the total sample. In the subsamples, married household heads dominated the samples, making up 74.6% in Abdoun Al-Janoubi and 73.1% in Al-Zahra, as shown in Table 2.

- 5.

- Household Size: The 3–<6 household size category dominated the total sample of the surveyed households (51.0%). The household size (3–<6) distributions for the Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra neighborhoods were very similar, making up 52.6% in Abdoun and 49.8% in Al-Zahra, as shown in Table 2.

- 6.

- Income Source: The income of most of the household heads interviewed came from permanent jobs, making up 40.7% of the total sample. Self-employed household heads were also dominant, making up 38.2%. Abdoun Al-Janoubi household heads were mostly self-employed, making up 52.1%. Al-Zahra household heads had mostly permanent jobs making up 44.1% of the sample, see Table 2.

- 7.

- Car Ownership: Most of the household heads surveyed responded positively to the car ownership, forming 65.4% of the total sample. In Abdoun Al-Janoubi, 94.4% owned a car, while in Al-Zahra neighborhood most household heads (56.6%) responded negatively to car ownership, as shown in Table 2.

4.1.2. Independent Variable—Accessibility to Services

4.1.3. Dependent Variable—Residents’ Wellbeing—PREMA Model

4.2. Hypothesis Testing and Discussion

4.2.1. Total Accessibility of Services Effect on Total Residents’ Wellbeing by Residential Setting

4.2.2. Total Accessibility of Service Components by Residential Setting

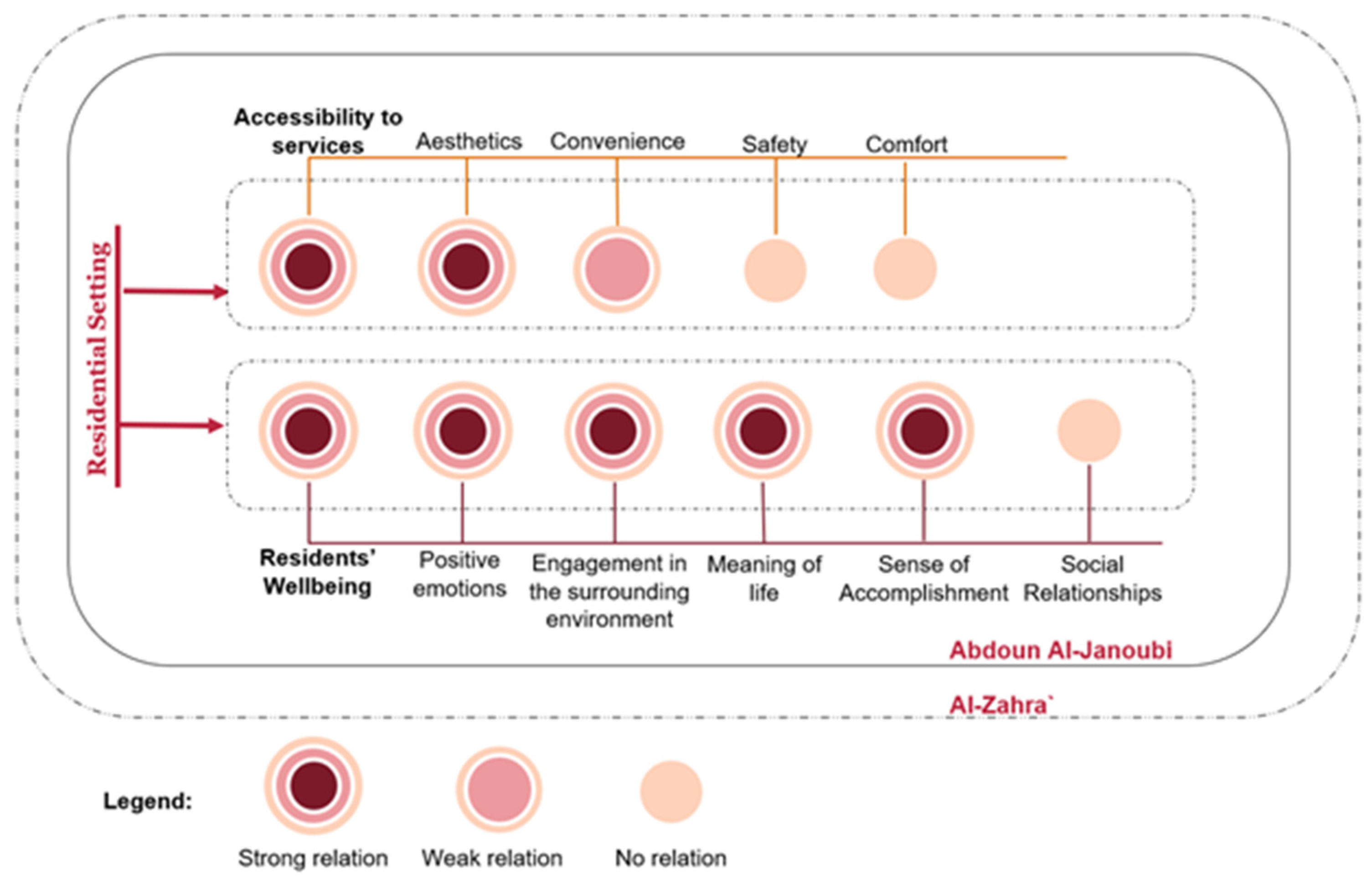

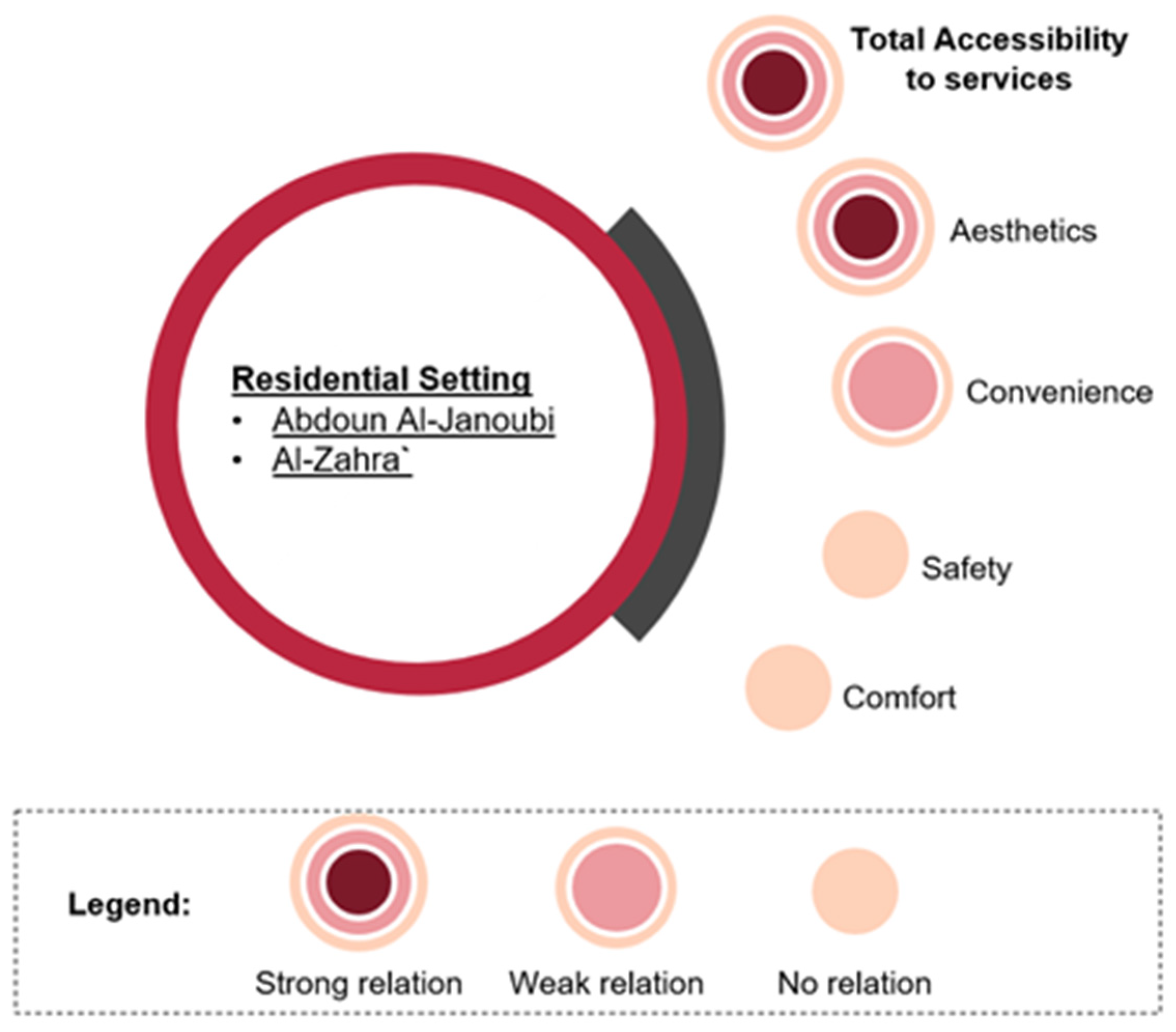

- Esthetics component of accessibility to services is affected by residential setting [F(490) = 20.33, p = 0.00]. Esthetics was significantly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 12.24, M = 4.25 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 3.08 for Al-Zahra). This finding agrees with [14,47], who explained that place accessibility is dependent on location and related to the spatial distribution of services in residential settings. Esthetics is a component of place accessibility (journey attributes).

- Total accessibility to services was also affected by residential settings [F(490) = 5.35, p = 0.02]. Total accessibility to services was slightly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than in the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 3.18, M = 3.38 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 3.23 for Al-Zahra). This finding agrees with [14,20,47], who believe that accessibility is affected by the wider economic context of a city and is more linked to high-income groups.

- The convenience component of accessibility to services was weakly affected by residential setting [F(490) = 3.39, p = 0.07]. Convenience was slightly higher in the Al-Zahra than the Abdoun Al-Janoubi neighborhood (t = 3.18, M = 3.61 for Al-Zahra, and M = 3.53 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi). This finding agrees with [14,47].

4.2.3. Total Residents’ Wellbeing Attributes by Residential Setting

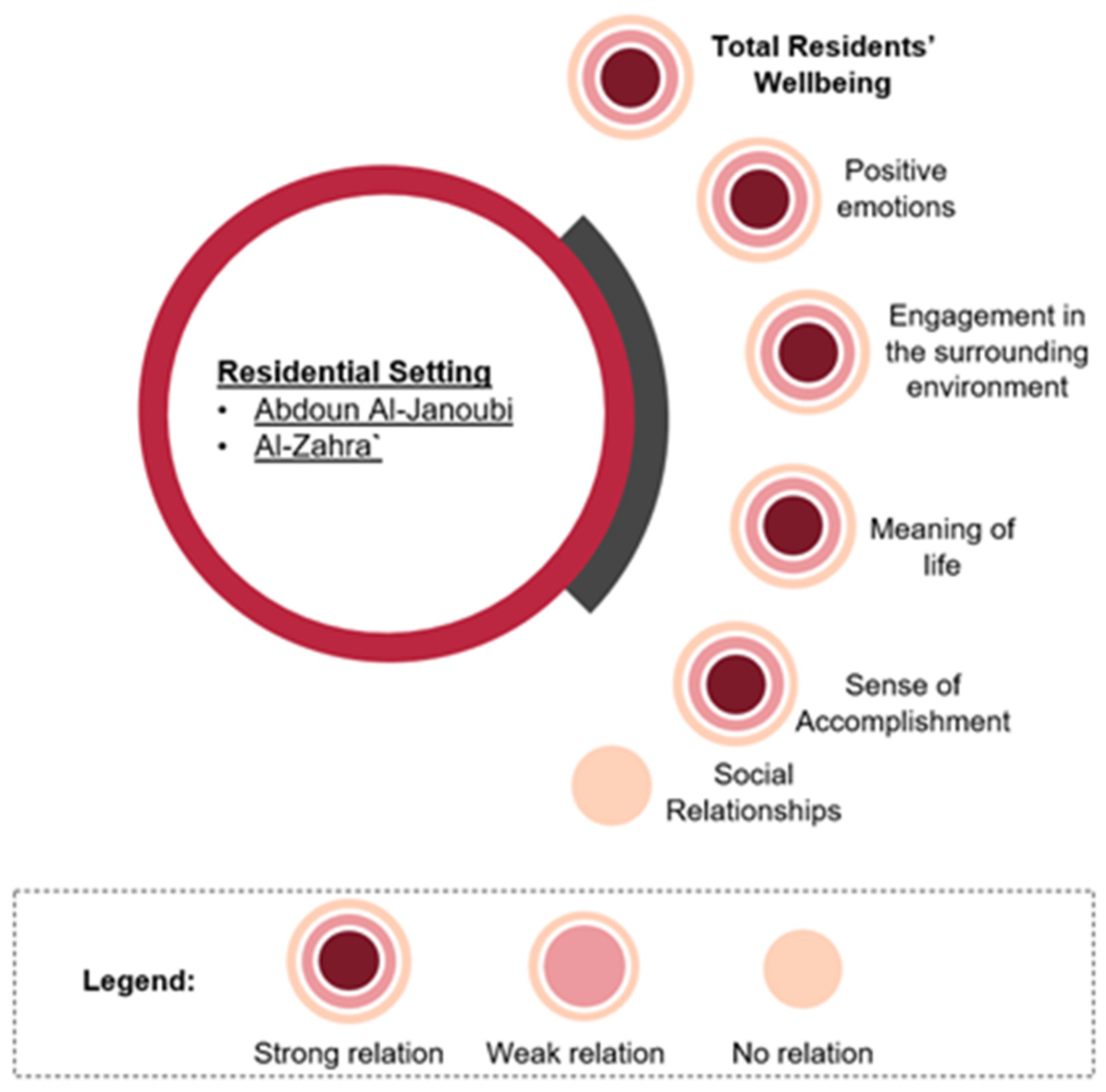

- The positive emotions attribute of residents’ wellbeing were affected by residential settings [F(490) = 31.70, p = 0.00]. Positive emotions were significantly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 8.87, M = 4.45 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 3.71 for Al-Zahra). This finding agrees with [17,52,66].

- Total residents’ wellbeing was also affected by residential setting [F(490) = 18.16, p = 0.00]. Total residents’ wellbeing was significantly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than in the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 8.80, M = 4.42 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 3.79 for Al-Zahra). This finding is likewise in agreement with [17,52,53], who clarified that wellbeing in cities can be achieved when cities and the inhabitants co-create a good living environment.

- The engagement in the surrounding environment attribute of residents’ wellbeing was further affected by residential setting [F(490) = 13.29, p= 0.00]. Engagement is slightly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 9.46, M = 4.68 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 4.14 for Al-Zahra). This finding is also in agreement with [17,52,66].

- The sense of accomplishment attribute of residents’ wellbeing was affected by residential setting [F(490) = 4.96, p = 0.03]. Sense of accomplishment was significantly slightly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 5.53, M = 4.40 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 4.04 for Al-Zahra). This finding is likewise in agreement with [17,52,66].

- The meaning of life attribute of residents’ wellbeing was weakly affected by residential setting [F(490) = 3.55, p = 0.06]. Meaning of life was significantly higher in the Abdoun Al-Janoubi than the Al-Zahra neighborhood (t = 7.48, M = 4.50 for Abdoun Al-Janoubi, and M = 3.93 for Al-Zahra). This finding is also in agreement with [17,52,66,70].

- However, the t-test results demonstrate that the social relationships attribute of residents’ wellbeing was not significant, which means that it was not affected by residential settings. Social relationships can be measured according to the subject’s social ties, social network, received support, perceived support, satisfaction with support, and giving support to others. This finding disagrees with [17,52,66].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusive Model Evaluation Insights

- Residential Setting Variation: The analysis reveals significant differences in socio-economic characteristics and accessibility to services between the two neighborhoods, Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra. A higher proportion of residents in Abdoun Al-Janoubi were in permanent employment and held more favorable socioeconomic attributes, such as car ownership and household size. This had an impact on their overall perception of accessibility to services, which was significantly higher compared to those in Al-Zahra.

- Gender Distribution: While the overall gender distribution among household heads was nearly equal, the neighborhood data indicate a divergence, with male predominance in Abdoun Al-Janoubi and female predominance in Al-Zahra. This suggests that gender roles or socio-economic dynamics may influence household structures differently across neighborhoods.

- Impact of Accessibility on Wellbeing: The significant correlation between accessibility to services and residents’ wellbeing supports the hypothesis that improved service access enhances wellbeing. Higher mean values of total accessibility to services in Abdoun Al-Janoubi align with residents reporting better wellbeing scores. This is consistent with previous research that emphasizes the influence of physical environmental attributes on quality of life.

- Components of Accessibility: The study identified that esthetics significantly influenced total accessibility to services, particularly in Abdoun Al-Janoubi, where higher scores were reported. This finding underscores the importance of the physical and esthetic quality of neighborhoods in enhancing overall accessibility experiences.

- Positive Emotions and Engagement: Abdoun Al-Janoubi residents reported significantly higher levels of positive emotions and engagement in their environment compared to those in Al-Zahra. This indicates that socio-economic factors and urban design may play critical roles in fostering psychological wellbeing, as residents in more affluent neighborhoods tend to have more positive emotional experiences tied to their living environments.

- Sense of Accomplishment: This attribute of wellbeing was also significantly higher in Abdoun Al-Janoubi. The socio-economic stability associated with the residential setting may contribute to a greater sense of achievement among the residents.

- Social Relationships: Interestingly, the analysis did not find significant differences in the social relationships attribute related to residential setting, contrary to what the previous literature suggested. This might indicate that social networks and relationships operate independently of the socioeconomic status of the neighborhoods, potentially offering insight into community dynamics.

- Comfort Issues: The findings indicate that although comfort measures were better rated in Al-Zahra, both neighborhoods faced challenges, which might be attributed to the limited public transportation options in Amman. This highlights the importance of addressing infrastructure to enhance accessibility and comfort across urban settings.

5.2. Outcomes of Accessibility and Wellbeing

- Total Accessibility and Wellbeing: The research empirically confirms that increased accessibility to services significantly correlates with higher resident wellbeing. Abdoun Al-Janoubi residents enjoy better accessibility and, consequently, report greater wellbeing than those in Al-Zahra, as shown in Figure 6.

- 2.

- Components of Accessibility: safety, esthetic appeal, and, to a lesser extent, convenience are important factors impacting wellbeing. However, ‘comfort’ shows no significant relationship with wellbeing. Abdoun Al-Janoubi ranks higher in esthetics and safety due to its environmental and infrastructural features, benefiting overall accessibility perception; see Figure 7.

- 3.

- Wellbeing Attributes: Analysis using the PERMA model revealed higher scores on wellbeing attributes such as positive emotions, engagement, meaning, and sense of accomplishment in Abdoun Al-Janoubi. Exceptionally, social relationships scored higher in Al-Zahra, suggesting distinct community dynamics and perhaps age-related influences that affect social ties; see Figure 8.

- 4.

- Influence of Urban Residential Setting: Residential settings strongly mediated both accessibility and the resulting wellbeing, as indicated by statistical tests. Despite greater convenience in public transport availability in Al-Zahra, logistic aspects such as private car reliance afford Abdoun Al-Janoubi an edge in overall convenience. Improvements in lighting and safer street designs offer further accessibility advantages.

- 5.

- Comparative Insights: The study reveals that although certain objective factors, like marital status and income, do not have a direct impact on wellbeing, the subjective perception of engagement and social cohesion does play a crucial role. This elevates Abdoun Al-Janoubi as a more favorable environment for a high quality of life (see Figure 9).

5.3. Strength of Model Attributes

5.4. Study Recommendations

- Enhance Physical Infrastructure: Improve path crossings and general street safety in high-density areas like Al-Zahra to match the levels seen in Abdoun Al-Janoubi. Investments in lighting, street width, and pedestrian paths could significantly improve accessibility and wellbeing.

- Promote Esthetic Upgrades: Encourage esthetic enhancements in neighborhoods to improve residents’ satisfaction and wellbeing. Planting trees, installing artistic features, and better maintaining public spaces could provide substantial benefits.

- Public Transport Accessibility: Improve public transportation to reduce congestion and reliance on private cars in areas like Abdoun Al-Janoubi to enhance convenience without compromising esthetics.

- Foster Social Engagement Programs: Develop community activities and engagement programs in both neighborhoods to strengthen social relationships, which were noted to be weakly connected to the residential setting and more influenced by other personal factors.

- Support Networks: Enhance social support networks in Al-Zahra by facilitating neighborhood meet-ups or community support groups where neighbors can share resources and offer help.

- Zoning and Regulatory Adjustments: Adjust zoning laws and embark on projects that balance residential density with the need for accessible services. This could involve creating mixed-use developments within or adjacent to existing residential areas to reduce travel distances.

- Amenities Improvement and Maintenance: Upgrade and maintain public amenities, such as parks and community centers, in both neighborhoods to ensure they meet the expected standards of comfort and safety. Public facilities must accommodate both the esthetic and practical needs of the residents.

- Participatory Initiatives: Engage in participatory urban planning to advocate for necessary changes in neighborhood infrastructure and services. Resident input should guide the prioritization of issues regarding comfort, safety, and the local environment.

- Awareness Campaigns: Organize awareness campaigns to promote the benefits of better urban planning and encourage community participation in maintaining neighborhood esthetics and safety.

- By focusing on these recommendations, stakeholders can improve the accessibility and overall wellbeing of residents in different urban settings in Amman. Implementing these changes holistically ensures that both the infrastructural and societal aspects of wellbeing are addressed effectively.

5.5. Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tal, R.; Tawil, M.; AlFuqaha, S.; Jibrini, H.; Ayyoub, A. The interpretation of land use change based on the interplay of place-specific complexity in Amman downtown. In Innovations for Land Management, Governance, and Land Rights for Sustainable Urban Transitions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, N.; Nagy, I. Urban environmental challenges and management facing Amman’s growing city. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2021, 11, 2991–3010. [Google Scholar]

- Dumper, M.; Stanley, B. (Eds.) Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel, R. Urban Development and the Role of the Service and Banking Sector in a “Rentier-State”; Hannoyer, J., Shami, S., Eds.; Presses de l’Ifpo: Amman, Jordan, 1996; pp. 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tal, R.; Al-Zubaydi, I. Trans-Placed Communities: The Impact of the Iraqi Community on the Spatial and Sociocultural Urban Structure of Amman. ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series, PLA2018-0108. Athens, Greece. 2018. Available online: https://www.atiner.gr/presentations/PLA2018-0108.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Ababsa, M. Atlas of Jordan; Institut français du Proche-Orient: Amman, Jordan, 2013; pp. 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifai, T. Amman City Centre: Typologies of Architecture and Urban Space; Hannoyer, J., Shami, S., Eds.; Presses de l’Ifpo: Amman, Jordan, 1996; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Lughod, L. Zones of theory in the anthropology of the Arab world. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1989, 18, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhamreh, Z.; Almanasyeha, N. Analyzing the state and pattern of urban growth and city planning in Amman using satellite images and GIS. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 24, 252–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kaw, J.K.; Park, H.; Edilbi, B. Future Amman Positioned at a Juncture: Three Strategies Toward Climate-Smart Spatial Transformation. ; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/41699 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Greater Amman Municipality (GAM). Voluntary Local Review: The City of Amman, Jordan. 2022. Available online: https://www.iges.or.jp/sites/default/files/inline-files/2022%20-%20Amman.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Nordregio. Amman: One of the Fastest-Growing Cities in the World Is Moving Towards Sustainable City Planning. Nordregio. 2021. Available online: https://nordregio.org/amman-one-of-the-fastest-grown-cities-in-the-world-is-moving-towards-sustainable-city-planning/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Bissonnette, L.; Wilson, K.; Bell, S.; Ikram, T. Neighborhoods and potential access to health care: The role of spatial and aspatial factors. Health Place 2012, 18, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.S. Analysing the role of accessibility in contemporary urban development. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2009: Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Taniar, D., Murgante, B., Laganà, A., Mun, Y., Gavrilova, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5592, pp. 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J. Working with Detained Populations in Greece and Libya: A Comparative Study of the Ethical Challenges Facing the International Rescue Committee. International Rescue Committee. 2019. Available online: https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/3932/ethicalchallengesofworkingwithpopulationsindetention-revisedjune2019.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Bekink, B. Municipal services and service delivery and the basic functional activities of municipal governments. In The Restructuring (Systemization) of Local Government Under the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa; Bekink, B., Ed.; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffaney, J. Thriving Cities: How to Define, Apply, and Measure Well-Being at Scale. University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. 2017. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/38757 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Jones, H.; Cummings, C.; Nixon, H. Services in the city: Governance and Political Economy in Urban Service Delivery. ODI Discussion Paper; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://gsdrc.org/document-library/services-in-the-city-governance-and-political-economy-in-urban-service-delivery/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Clark II, W.; Cooke, G. Smart green cities: Toward a carbon-neutral world. In Smart Green Cities: Toward a Carbon Neutral World; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 124–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, P.; Heeckt, C.; Huerta Melchor, O.; Flynn, R.; Liebenau, J. Better Access to Urban Opportunities: Accessibility Policy for Cities in the 2020s. Coalition for Urban Transitions. 2021. Available online: https://urbantransitions.global/publications (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Firrone, T.; Vitrano, R.M.; Fernandez, F.; Zagarella, F.; Garofalo, E. Environmental Design Principles for Urban Comfort: The Pilot Case Study of Naro Municipality. Buildings 2024, 14, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.; Xue, F.; Chen, H. Assessment of Health-Oriented Layout and Perceived Density in High-Density Public Residential Areas: A Case Study of Shenzhen. Buildings 2024, 14, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Tian, L.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Gao, Y.; Xia, J. Land-Use Planning Serves as a Critical Tool for Improving Resources and Environmental Carrying Capacity: A Review of Evaluation Methods and Application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amler, B.; Betke, D.; Eger, H.; Ehrich, C.; Kohler, A.; Kutter, A.; von Lossau, A.; Müller, U.; Seidemann, S.; Steurer, R.; et al. Land Use Planning: Methods, Strategies and Tools; Universum Verlagsanstalt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1999; pp. 12–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Ran, Q.; Ding, X.; Wang, H.; Ding, A. Predicting Land Use Changes under Shared Socioeconomic Pathway–Representative Concentration Pathway Scenarios to Support Sustainable Planning in High-Density Urban Areas: A Case Study of Hangzhou, Southeastern China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Deng, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Optimization of Spatial Pattern of Land Use: Progress, Frontiers, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, J.R.; Stanley, J.K.; Hansen, R. How great cities happen: Integrating people, land use, and transport. Edward Elgar Publishing. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 79, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. 2018, pp. 14–19. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Qin, Z.; Gan, W.; He, Z.; Li, X. Is the Children’s 15-Minute City an Effective Framework for Enhancing Children’s Health and Well-Being? An Empirical Analysis from Western China. Buildings 2025, 15, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development. Rio Earth Summit. 1992, pp. 279–281. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/outcomedocuments/agenda21 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Baer, W.C. Just what Is an Urban service, anyway? J. Politics 1985, 47, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Y. Enhancing Urban Living Convenience through Plot Patterns: A Quantitative Morphological Study. Buildings 2024, 14, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S. Urban expansion: Theory, evidence and practice. Build. Cities 2023, 4, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AECOM. Assessment Report: Urban Planning Regulatory Framework Study; Submitted to Ministry of Municipal Affairs; AECOM: Amman, Jordan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- AECOM. Regional and Local Development Project—Urban Planning Regulatory Framework: Model Planning and Zoning Standards; Submitted to Ministry of Municipal Affairs; AECOM: Amman, Jordan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics, Jordan. Jordan Population and Housing Census; Department of Statistics, Jordan: Amman, Jordan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Urban Planning & Infrastructure in Migration Contexts: AMMAN SPATIAL PROFILE, Jordan. Amman, Jordan. 2022. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/04/220411-final_amman_profile.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Abdeljawad, N.; Nagy, I. Evaluation of Urban Land Use-Related Policies to Reduce Urban Sprawl Environmental Consequences in Amman City, Jordan, Compared with Two Other Cities. Wseas Trans. Environ. Dev. 2023, 19, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins English Dictionary. Accessibility. In Collins Dictionary. 2023. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Nordquist, R. The Principle of Least Effort: Definition and Examples of Zipf’s Law. 2023. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/principle-of-least-effort-zipfs-law-1691104 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Meknaci, M.E.F.; Wang, X.; Biara, R.W.; Zerouati, W. Analysis of the Urban Form of Bechar through the Attributes of Space Syntax “for a More Sustainable City”. Buildings 2024, 4, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Safdar, M.; Zhong, M.; Hunt, J.D. Analyzing Spatial Location Preference of Urban Activities with Mode-Dependent Accessibility Using Integrated Land Use–Transport Models. Land 2022, 11, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.E.; Fotheringham, A.S. Gravity and Spatial Interaction Models; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wegener, M.; Fürst, F. Land-Use Transport Interaction: State of the Art; University of Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, A.; Silva, C.; Bertolini, L. Accessibility Instruments for Planning Practice in Europe; COST Office, European Cooperation in Science and Technology: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chen, N. A gravity Model Integrating Land-Use and Transportation Policies for Sustainable Development: Case Study of Fresno; Mineta Transportation Institute: San Jose, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, C.; Handy, S.; Kockelman, K.; Mahmassani, H.; Chen, Q.; Weston, L. Accessibility Measures: Formulation Considerations and Current Applications; Center for Transportation Research: Austin, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lättman, K.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M. A new approach to accessibility—Examining perceived accessibility in contrast to objectively measured accessibility in daily travel. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 69, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, P.; Kandt, J.; Baker, K. Access to the City: Transport, Urban form and Social Exclusion in São Paulo, Mumbai and Istanbul. LSE Cities Working Papers. LSE Cities. 2016. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/100142 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Naci, H.; Ioannidis, J.P. Evaluation of wellness determinants and interventions. JAMA 2015, 314, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House. 1961, pp. 29–112. Available online: https://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Ala-Mantila, S.; Heinonen, J.; Junnila, S.; Saarsalmi, P. Spatial nature of urban well-being. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.A.; Uttl, B.; Holder, M.D. Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: The effects are much smaller than previously reported. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, O. Creating Defensible Space; Center of Urban Policy Research: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; Institute for Community Design Analysis, Rutgers University: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Winer, S.L. The political economy of taxation: Power, structure, redistribution. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Choice: Volume 2, online ed.; Congleton, R.D., Grofman, B., Voigt, S., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, V.E.; Bickerton, I.J.; Abu Jaber, K.S. Jordan. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2024. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Jordan (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- McCarty, N.; Pontusson, J. The political economy of inequality and redistribution. In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, online ed.; Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Smeeding, T.M., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurtu, I.C.; Khetani, K.P.; Scheaua, F.D. In Search of Eudaimonia Towards Circular Economy in Buildings—From Large Overarching Theories to Detailed Engineering Calculations. Buildings 2024, 14, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comolet, E. Jordan: The Geopolitical Service Provider. Global Economy & Development Working Paper 70. 2014. Available online: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/wps/bi/0030378/f_0030378_24552.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Miller, T.; Kim, A.; Roberts, J. 2019 Index of Economic Freedom; The Heritage Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 77–84. Available online: https://www.heritage.org (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, J.; Christakis, N. Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, T.; Schotanus-Dijkstra, M.; Hassankhan, A.; Bohlmeijer, E.; de Jong, J. The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 357–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Tay, L. Subjective well-being and human welfare around the world as reflected in the gallup world poll. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.; Keyes, C. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; The Free Pres: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 14–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hendawi, M.; Alodat, A.; Al-Zoubi, S.; Bulut, S. A PERMA model approach to well-being: A psychometric properties study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.E.; Alder, J.; White, M.A. A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 10, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.T.P. Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2011, 52, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Residential Typology | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | Al-Zahra | Total Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Residence A | 158 | 74.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 158 | 32.1% |

| Residence B | 46 | 21.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 46 | 9.3% |

| Residence C | 0 | 0.0% | 144 | 51.6% | 144 | 29.3% |

| Residence D | 9 | 4.2% | 3 | 1.1% | 12 | 2.4% |

| Light Industries | 0 | 0.0% | 132 | 47.3% | 132 | 26.8% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 122 | 57.3% | 117 | 41.9% | 239 | 48.6% |

| Female | 91 | 42.7% | 162 | 58.1% | 253 | 51.4% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–<30 Years | 20 | 9.4% | 86 | 30.8% | 106 | 21.5% |

| 30–<40 Years | 69 | 32.4% | 94 | 33.7% | 163 | 33.1% |

| 40–<50 Years | 69 | 32.4% | 58 | 20.8% | 127 | 25.8% |

| >50 Years | 55 | 25.8% | 41 | 14.7% | 96 | 19.5% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Marital Status | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | Al-Zahra | Total Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Single | 28 | 13.1% | 52 | 18.6% | 80 | 16.3% |

| Married | 159 | 74.6% | 204 | 73.1% | 363 | 73.8% |

| Divorced | 14 | 6.6% | 7 | 2.5% | 21 | 4.3% |

| Widowed | 12 | 5.6% | 16 | 5.7% | 28 | 5.7% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Household size | ||||||

| 1–<3 | 76 | 35.7% | 62 | 22.2% | 138 | 28.0% |

| 3–<6 | 112 | 52.6% | 139 | 49.8% | 251 | 51.0% |

| 6–<10 | 25 | 11.7% | 68 | 24.4% | 93 | 18.9% |

| >10 | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 3.6% | 10 | 2.0% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Income source | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1 | 0.5% | 35 | 12.5% | 36 | 7.3% |

| Self-Employed | 111 | 52.1% | 77 | 27.6% | 188 | 38.2% |

| Permanent Job | 77 | 36.2% | 123 | 44.1% | 200 | 40.7% |

| Pensions | 24 | 11.3% | 44 | 15.8% | 68 | 13.8% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Car Ownership | ||||||

| No | 12 | 5.6% | 158 | 56.6% | 170 | 34.6% |

| Yes | 201 | 94.4% | 121 | 43.4% | 322 | 65.4% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 279 | 100% | 492 | 100% |

| Neighborhood | Total Accessibility to Services | Safety | Convenience | Comfort | Esthetics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdoun Al-Janoubi | Mean | 3.38 | 3.87 | 3.53 | 1.89 | 4.25 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.86 | |

| Variance | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.74 | |

| Minimum | 2.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum | 4.6 | 5 | 5 | 4.3 | 5 | |

| Al-Zahra | Mean | 3.23 | 3.83 | 3.61 | 2.39 | 3.08 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 1.17 | |

| Variance | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 1.38 | |

| Minimum | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum | 4.9 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Total Sample | Mean | 3.29 | 3.85 | 3.57 | 2.17 | 3.59 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 1.20 | |

| Variance | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 1.44 | |

| Minimum | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum | 4.9 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Neighborhood | Total Residents’ Wellbeing | Positive Emotions | Social Relationships | Engagement in Surrounding Environment | Meaning of Life | Sense of Accomplishment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdoun Al-Janoubi | Mean | 4.42 | 4.45 | 4.06 | 4.68 | 4.50 | 4.40 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.66 | |

| Variance | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.55 | 0.43 | |

| Minimum | 2.8 | 2 | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Al-Zahra | Mean | 3.97 | 3.71 | 4.01 | 4.14 | 3.93 | 4.04 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.63 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.77 | |

| Variance | 0.39 | 1.09 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.60 | |

| Minimum | 1.9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Total Sample | Mean | 4.16 | 4.03 | 4.03 | 4.37 | 4.18 | 4.19 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.61 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.75 | |

| Variance | 0.37 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.78 | 0.56 | |

| Minimum | 1.9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Model | −2 Log Likelihood | Chi-Square | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Only | 3489.88 | |||

| Final | 2951.46 | 538.42 | 186 | 0.00 |

| F | Sig. | T | Df | Equality of Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | |||||

| Total Accessibility to services | 5.35 | 0.02 | 3.18 | 490 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Safety | 2.49 | 0.12 | 0.69 | 490 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Convenience | 3.39 | 0.07 | −1.24 | 490 | −0.08 | 0.07 |

| Comfort | 0.45 | 0.50 | −6.87 | 490 | −0.50 | 0.07 |

| Esthetics | 20.33 | 0.00 | 12.24 | 490 | 1.17 | 0.10 |

| Neighborhood | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Accessibility to services | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 3.38 | 0.50 | 0.03 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.23 | 0.58 | 0.04 | |

| Safety | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 3.87 | 0.62 | 0.04 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.83 | 0.69 | 0.04 | |

| Convenience | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 3.53 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.61 | 0.69 | 0.04 | |

| Comfort | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 1.89 | 0.77 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 2.39 | 0.82 | 0.05 | |

| Esthetics | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.25 | 0.86 | 0.06 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.08 | 1.17 | 0.07 |

| F | Sig. | T | Df | Equality of Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | |||||

| Total residents’ wellbeing | 18.16 | 0.00 | 8.80 | 490 | 0.45 | 0.05 |

| Positive emotions | 31.70 | 0.00 | 8.87 | 490 | 0.74 | 0.08 |

| Social relationships | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 490 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Engagement in surrounding environment | 13.29 | 0.00 | 9.46 | 490 | 0.54 | 0.06 |

| Meaning of life | 3.55 | 0.06 | 7.48 | 490 | 0.57 | 0.08 |

| Sense of accomplishment | 4.96 | 0.03 | 5.53 | 490 | 0.36 | 0.07 |

| Neighborhood | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total residents’ wellbeing | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.42 | 0.47 | 0.03 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.97 | 0.63 | 0.04 | |

| Positive emotions | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.45 | 0.71 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.71 | 1.04 | 0.06 | |

| Social relationships | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.06 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 4.01 | 0.79 | 0.05 | |

| Engagement in surrounding environment | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.68 | 0.51 | 0.04 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 4.14 | 0.70 | 0.04 | |

| Meaning of life | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.50 | 0.74 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 3.93 | 0.91 | 0.05 | |

| Sense of accomplishment | Abdoun Al-Janoubi | 213 | 4.40 | 0.66 | 0.05 |

| Al-Zahra | 279 | 4.04 | 0.77 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Homoud, M.; Aldahody, R. Service Accessibility and Wellbeing in Amman’s Neighborhoods: A Comparative Study of Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra. Buildings 2025, 15, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030412

Al-Homoud M, Aldahody R. Service Accessibility and Wellbeing in Amman’s Neighborhoods: A Comparative Study of Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra. Buildings. 2025; 15(3):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030412

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Homoud, Majd, and Reema Aldahody. 2025. "Service Accessibility and Wellbeing in Amman’s Neighborhoods: A Comparative Study of Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra" Buildings 15, no. 3: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030412

APA StyleAl-Homoud, M., & Aldahody, R. (2025). Service Accessibility and Wellbeing in Amman’s Neighborhoods: A Comparative Study of Abdoun Al-Janoubi and Al-Zahra. Buildings, 15(3), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15030412