1. Introduction

As global urbanization continues to accelerate, well-being has increasingly been recognized within the international academic community as a key indicator of urban development quality, gaining prominence in discussions of social sustainability and health-oriented urban planning [

1]. Against this international research backdrop, growing scholarly attention has been directed toward the emotional, psychological, and social values of urban public spaces. Research on sports venues, in particular, has begun to shift from traditional functional perspectives toward more holistic examinations of human–environment interactions [

2]. Within this emerging discourse, nature-based sports venues—which incorporate natural elements into spaces for physical activity—are viewed as potential environments for supporting psychological restoration and enhancing residents’ well-being [

3]. Nevertheless, empirical research in this area remains limited and is still at an early developmental stage.

A substantial body of international scholarship has demonstrated that exposure to natural environments can reduce psychological stress, stabilize emotions, restore cognitive resources, and enhance subjective well-being [

4]. In high-density urban settings, the visibility and accessibility of nature serve as critical restorative resources and have been shown to significantly improve residents’ satisfaction with urban life [

5,

6]. However, existing research has largely concentrated on urban green spaces, parks, and neighborhood landscapes [

7,

8], while comparatively little attention has been devoted to sports venues that integrate both functional and natural attributes. At the same time, studies in sports architecture predominantly emphasize physical and technical dimensions—such as energy efficiency, structural performance, and green certification [

9]. These approaches seldom address the psychological benefits, emotional value, or contributions of natural design to residents’ well-being.This gap in the international research landscape underscores the need to systematically examine the psychological mechanisms and pathways through which nature-based sports venues may enhance urban well-being.

At the psychological level, Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA) are widely recognized as key emotional pathways through which natural experiences shape well-being. Connectedness to Nature (CN) describes the cognitive and affective bond individuals perceive between themselves and the natural environment [

10]. Higher levels of Connectedness to Nature (CN) have been consistently associated with stronger positive emotions, greater life satisfaction, and a heightened tendency toward pro-environmental behavior [

11]. Likewise, Place Attachment (PA) represents an individual’s sense of belonging, identification, and functional dependence on a particular space, serving as an essential psychological construct that links people to their environments [

12]. Research has shown that Place Attachment (PA) not only strengthens residents’ sense of social cohesion and overall life satisfaction but also helps maintain psychological stability when individuals encounter environmental stressors [

13]. Recent studies further suggest that Connectedness to Nature (CN) may enhance individuals’ well-being indirectly by strengthening Place Attachment (PA) [

14]. Existing research has also applied these two psychological constructs jointly to examine how natural environments promote happiness. According to prior research This serial mechanism provides a novel interpretive framework for understanding the relationship between natural environments and urban happiness [

15] showed that stronger Connectedness to Nature (CN) predicts higher place attachment (PA), which subsequently enhances life satisfaction. Likewise, and reported that individuals’ Connectedness to Nature (CN) facilitates emotional bonding with places, indirectly contributing to subjective well-being [

16]. These studies reinforce the validity of using Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA) together to understand the relationship between natural environments and urban happiness.This serial mechanism provides a novel interpretive framework for understanding the relationship between natural environments and urban happiness.

Building on this international body of research, the present study draws on environmental psychology, place attachment theory, and principles of biophilic design to propose a dual-mediation model. The model examines how the natural design features of nature-based sports venues—specifically Natural Visibility (NV), Spatial Integration (SI), and Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI)—influence residents’ Urban Well-being (UWB) through the combined mediating roles of Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA). To empirically test these mechanisms, data were collected from ten representative nature-integrated sports venues in China, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the hypothesized pathways. Through this investigation, the study aims to address a gap in international scholarship concerning the psychological processes linking natural environments to urban well-being and to offer theoretical insights for the planning of nature-oriented sports venues and the development of health-promoting urban spaces.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Nature-Based Sports Venues and Urban Well-Being

In high-density urban contexts, residents’ well-being is influenced not only by economic and social factors but also by the environmental characteristics of urban public spaces [

17]. Among these spaces, sports venues—combining functions of social interaction and health promotion—are increasingly recognized as important settings for enhancing residents’ subjective well-being [

18]. Among these spaces, sports venues—which combine functions of social interaction and health promotion—are increasingly recognized as important settings for enhancing residents’ subjective well-being [

19]. However, conventional sports facilities often emphasize functional efficiency and architectural performance while neglecting the influence of natural environments on users’ psychological experiences.

With the growing prevalence of the biophilic design concept, nature-based sports venues have emerged as a new direction for sustainable urban development [

20]. These venues incorporate natural elements such as water, vegetation, natural lighting, and ventilation to strengthen human–nature interactions. This integration not only improves the microclimate and landscape quality but may also enhance urban well-being through psychological restoration and emotional identification with the environment [

21].

Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to natural landscapes can effectively reduce psychological stress, restore attention, and promote emotional stability [

22,

23]. Moreover, higher accessibility and visibility of natural elements in urban environments are associated with greater levels of happiness among residents. Nevertheless, research specifically examining how nature-based sports venues promote well-being through psychological mechanisms remains limited. Most existing studies have focused on parks or urban green spaces [

7], overlooking the emotional benefits of sports environments that integrate both functional and natural attributes.

Therefore, this study takes nature-based sports venues as the research focus and explores how their natural design features influence residents’ urban well-being, with particular attention to the emotional mediation pathways underlying this relationship.

2.2. Natural Design Features and Place Attachment

Natural design features refer to the perceivable elements within architectural or spatial environments that embody the relationship between humans and nature. These features generally encompass three dimensions: natural visibility, spatial integration, and human–nature interactivity [

3]. Together, they reflect the degree to which a space integrates with its surrounding natural environment in visual, structural, and behavioral aspects.

Previous studies have indicated that visually accessible natural elements—such as water, vegetation, and the sky—can evoke feelings of pleasure, relaxation, and belonging, thereby fostering a stronger sense of spatial attachment. Extensive empirical evidence shows that visual exposure to nature enhances emotional restoration and promotes positive affect [

5,

7]. More recent work has further demonstrated that even brief or indirect visual contact with natural scenes can elevate well-being and strengthen individuals’ emotional connection to the surrounding environment [

8,

23]. These findings collectively highlight the importance of natural visibility as a key factor shaping spatial attachment [

24]. Spatial integration emphasizes the continuity and harmony between natural elements and built environments, where a higher degree of integration enhances perceived environmental quality and place identity [

25]. Meanwhile, human–nature interactivity represents a shift from passive perception to active engagement; such participatory experiences reinforce users’ sense of involvement and emotional connection with the environment [

26]. Empirical evidence suggests that greater levels of natural integration and interactivity lead to stronger emotional investment and functional dependence on a place, ultimately fostering higher place attachment [

27]. Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a. Natural Visibility has a positive effect on Place Attachment.

H1b. Spatial Integration has a positive effect on Place Attachment.

H1c. Human–Nature Interactivity has a positive effect on Place Attachment.

2.3. Natural Design Features and Connectedness to Nature

Connectedness to nature reflects individuals’ sense of emotional affinity, cognitive awareness, and experiential involvement with the natural environment [

10] and is therefore considered a key psychological indicator of how people internalize nature-based experiences. Rather than merely describing a general bond with nature, Connectedness to nature captures the depth of one’s identification and engagement, shaping how natural settings influence emotional responses and behavioral tendencies. Higher levels of Connectedness to nature have been consistently associated with enhanced positive emotions, increased well-being, and stronger pro-environmental behavioral intentions [

11]. Research in architecture and landscape design suggests that the visibility and engagement of natural elements are essential conditions for fostering Connectedness to nature [

28].

Within the context of sports venues, natural design features—including natural visibility, spatial integration, and human–nature interactivity—facilitate individuals’ perception of the presence and intimacy of nature through visual exposure, spatial continuity, and embodied experience [

29]. For instance, visible elements such as water bodies, natural lighting, and green layouts can directly evoke psychological participation in nature, while walkable and touchable ecological spaces help sustain this emotional connection over time. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1d. Natural Visibility has a positive effect on Connectedness to Nature.

H1e. Spatial Integration has a positive effect on Connectedness to Nature.

H1f. Human–Nature Interactivity has a positive effect on Connectedness to Nature.

2.4. Connectedness to Nature, Place Attachment, and Urban Well-Being

In environmental psychology, connectedness to nature and place attachment are both regarded as emotional bond variables, although their psychological pathways differ slightly. Connectedness to nature emphasizes the cognitive and affective dimensions of the human–nature relationship, whereas place attachment focuses on the sense of belonging and dependence within the human–place relationship [

10]. Previous research has demonstrated a significant positive association between the two: individuals who perceive a stronger connection with nature are more likely to develop emotional attachment and identification with their surrounding places [

30].

A substantial body of empirical evidence also indicates that place attachment not only enhances residents’ life satisfaction but also significantly contributes to their well-being and mental health [

31,

32]. Within urban public spaces, place attachment strengthens happiness experiences through mechanisms of social interaction, belonging, and meaning-making [

33]. Accordingly, this study posits that connectedness to nature can directly improve well-being and may also exert an indirect effect by promoting place attachment. Based on these theoretical arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2. Connectedness to Nature has a positive effect on Place Attachment.

H3. Place Attachment has a positive effect on Urban Well-Being.

H4. Connectedness to nature has a positive effect on Urban Well-Being.

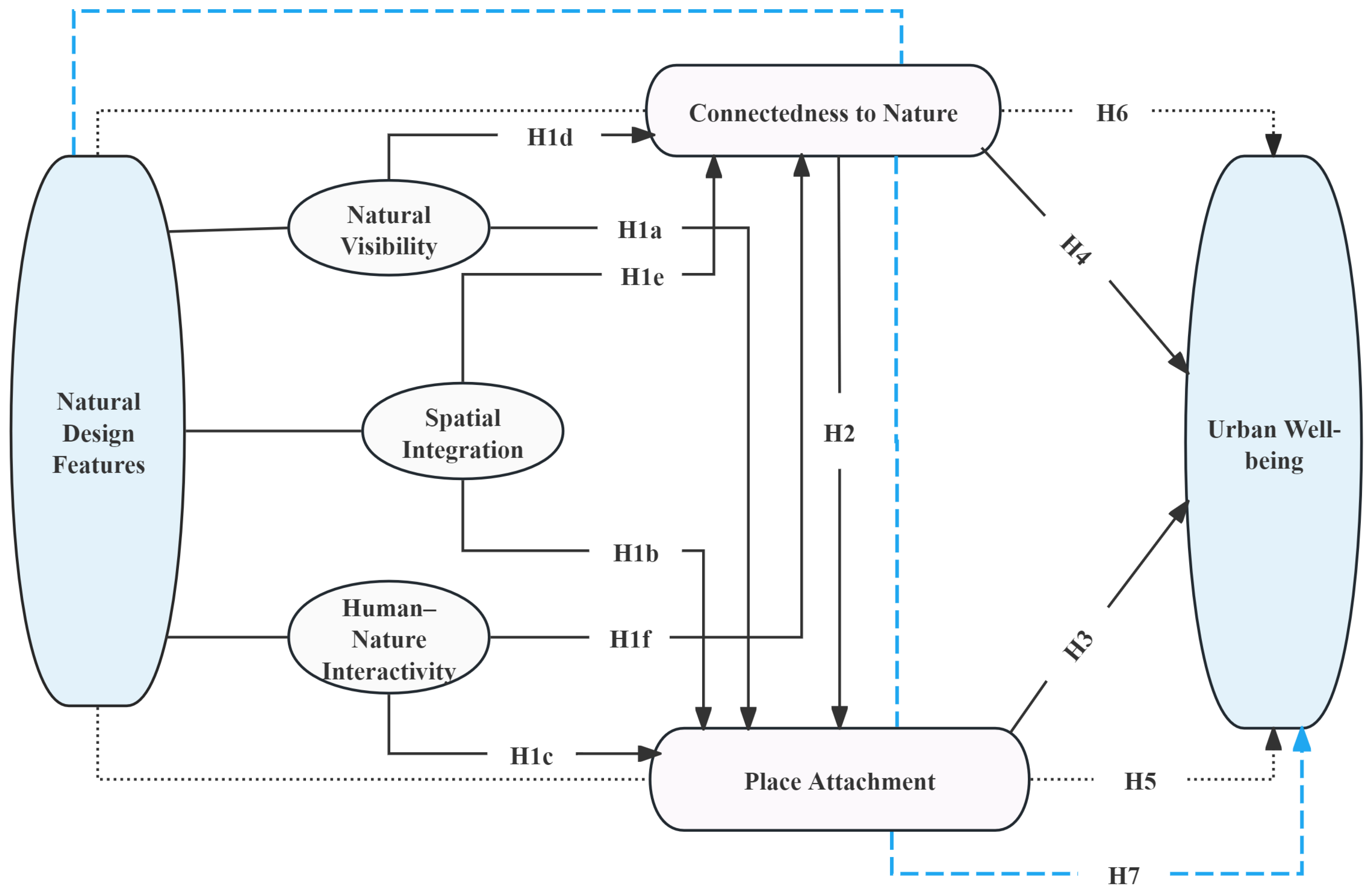

2.5. Parallel and Serial Mediation Model

A dual-mediation model refers to a theoretical framework in which two mediating variables simultaneously transmit the effects of an independent variable onto an outcome variable, either in parallel or in a sequential (serial) manner. This approach is widely used in psychological and environmental behavior research to uncover multilayered cognitive and emotional mechanisms underlying human–environment interactions [

34].

A dual-mediation model is suitable for the present study because natural design features are theorized to influence urban well-being through two distinct but interrelated psychological processes—cognitive appraisal of nature (connectedness to nature) and emotional bonding to place (place attachment). These constructs not only operate independently but may also form a sequential pathway in which cognitive identification with nature enhances emotional dependence on place, thereby jointly shaping individuals’ well-being outcomes [

11,

16]. Given this theoretical structure, employing a dual-mediation model provides a comprehensive framework to evaluate both the parallel and serial psychological mechanisms through which natural design features affect urban well-being. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed (the proposed model diagram is shown in

Figure 1):

H5. Place Attachment mediates the relationship between Natural Design Features and Urban Well-Being.

H6. Connectedness to Nature mediates the relationship between Natural Design Features and Urban Well-Being.

H7. Natural Design Features indirectly affect Urban Well-Being through the serial pathway from Connectedness to Nature to Place Attachment.

Figure 1.

Structural model illustrating the parallel and sequential mediation of Connectedness to Nature and Place Attachment between natural design features and urban well-being.

Figure 1.

Structural model illustrating the parallel and sequential mediation of Connectedness to Nature and Place Attachment between natural design features and urban well-being.

3. Research Design

3.1. Recipients and Questionnaire Distribution

This study adopted a multi-stage stratified sampling method to conduct questionnaire surveys among regular users of ten representative nature-based sports venues in China. The sample selection comprehensively considered geographical distribution (eastern, central, and coastal regions), city scale, level of economic development, and the typicality of natural design features, in order to ensure both representativeness and diversity of the sample.

The survey participants were urban residents aged 18–65 years who had visited the target venues at least once per month and participated in physical or leisure activities, ensuring that respondents had genuine experiences with the venues’ natural design features. Professional athletes, coaches, and on-duty venue staff were excluded, with the study focusing on general public users. The selection criteria for the research venues included the following three aspects:

The architectural design explicitly incorporated biophilic or nature-oriented elements, such as large-scale natural lighting, vertical greenery, ecological materials, water landscapes, or rain gardens. The venue had received municipal-level or higher awards or certifications related to green building, ecological landscape, or healthy architecture. The venue was evaluated on-site by an expert panel in architecture and environmental psychology and confirmed as having significant nature-integration characteristics.

The study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ludong university (Approval No.: IRBLDU20250616, approval date: 16 June 2025). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. The questionnaire survey was conducted from June to August 2025 by eight professionally trained investigators.

Data collection was carried out using an on-site random interception method, balanced across weekdays and weekends, as well as different time periods (morning, afternoon, and evening), to minimize temporal and population bias. A total of 930 questionnaires were distributed, and 894 were returned. After logical consistency checks and manual verification, 856 valid responses were obtained, resulting in an effective response rate of 95.7%.

To reduce potential sampling bias, the study also controlled for the proportion of users with different usage frequencies, activity types, and spatial zones (indoor areas, outdoor trails, and nature-interactive zones), thereby ensuring data balance and authenticity. The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Variable Measurement

All variables in this study were measured using internationally recognized and well-validated scales, which were adapted to align with the cultural and contextual characteristics of nature-based sports venues. A five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was employed to capture respondents’ evaluations of each item.

To ensure semantic accuracy and cross-cultural appropriateness, a forward–backward translation procedure was conducted, followed by expert review from three specialists in architectural psychology and sports behavior. In addition, a focus group comprising 12 frequent users of nature-based sports venues was organized to assess the clarity, relevance, and contextual fit of the questionnaire items. These procedures collectively helped establish the reliability and validity of the measurement instruments used in this study.

The measurement of Natural Visibility (NV) was grounded in Ulrich’s [

4] theory of visual access to nature and adapted from Zhang et al. [

35], with semantic modifications tailored to the characteristics of nature-based sports venues. Considering the typical features of nature-based sports venues—such as greenery, water elements, and sky views—the items were refined to more accurately capture visual perceptions of natural elements in these settings. This dimension assesses the extent to which individuals perceive surrounding natural features through visual channels. The revised items effectively represent respondents’ subjective experiences of nature visibility, and reliability testing indicated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.896 and corrected item–total correlations (CITC) all exceeding 0.74.

The measurement of Spatial Integration (SI) was informed by the biophilic design principles proposed by Kellert and Calabrese [

20], To reflect the architectural characteristics of sports venues, the original items were contextually adapted to evaluate the coherence and continuity between built spaces and their surrounding natural environments. The refined items capture respondents’ perceptions of the natural transition between indoor and outdoor areas, the degree to which building materials align with natural features, and the overall sense of balance embodied in the spatial layout. Reliability analysis demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.889 and all corrected item–total correlations (CITC) exceeding 0.80, indicating a highly stable factor structure.

The measurement of Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI). The scale for Human–Nature Interactivity was developed by integrating Kaplan’s [

22] Nature Interaction Scale and the Outdoor Activity Frequency Questionnaire by Ryan et al. [

36], To align with the context of sports venue use, the construct was redefined to emphasize the frequency and depth of individuals’ direct engagement with natural elements during physical activity. The revised items address opportunities for nature contact, the richness of nature-based experiential engagement, and the extent to which venue design facilitates human–nature interaction. Reliability testing indicated solid internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.879 and CITC values ranging from 0.72 to 0.79.

The measurement of Connectedness to Nature (CN) was adapted from the simplified version of the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) developed by Mayer and Frantz [

10], with additional semantic refinements informed by Tam [

37] to fit the context of nature-based sports venues. This construct captures the extent to which individuals develop cognitive and affective ties with nature while engaging in venue activities, including feelings of being surrounded by natural elements, emotional affinity toward nature, and endorsement of nature–human coexistence. Reliability testing demonstrated stable performance, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.867 and all corrected item–total correlations (CITC) exceeding 0.67.

The measurement of Place Attachment (PA) was informed by foundational work from Scannell and Gifford [

12] and Raymond et al. [

30], with modifications made to reflect the environmental characteristics of nature-based sports venues. This dimension assesses emotional bonding, sense of belonging, and psychological identification with the venue, encompassing affective dependence on its atmosphere, the role of the venue in constructing personal meaning, and emotional responses to potential changes in the setting. The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.886 and CITC values ranging from 0.71 to 0.75.

The measurement of Urban Well-being (UWB) was adapted from the classic studies of van den Berg et al. [

7] and White et al. [

5] on the relationship between natural environments and subjective well-being, with cultural adjustments made to reflect the lived experiences of residents in Chinese cities. This construct assesses the positive emotional experiences individuals derive from nature-based sports venues, the extent to which such environments enhance satisfaction with urban life, and their contribution to fostering a stronger sense of belonging to the city. The scale demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s

of 0.871 and CITC values ranging from 0.68 to 0.71, indicating a stable and robust measurement structure.

The results of the reliability analysis showed that all dimensions had Cronbach coefficients

coefficients above 0.85, which were significantly higher than the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 [

38]. This indicates that the measurement instruments used in this study demonstrated high internal consistency and structural stability, thus providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). For clarity of presentation, a comprehensive list of variable abbreviations used throughout this study is provided in

Table 2.

3.3. Research Procedure

The data analysis in this study followed standard procedures for empirical research using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), drawing upon established methodological literature to ensure analytical rigor. The process began with preliminary assessments of reliability and validity for all measurement items, including internal consistency (Cronbach’s

), the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Together, these tests confirmed that the data were appropriate for factor analysis [

38,

39,

40].

Subsequently, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component extraction and the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1) to identify the underlying dimensional structure [

41]. The EFA served to examine item convergence and discriminability, providing the foundational structure for subsequent model testing [

42].

Once the latent structure was established, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed to evaluate the fit of the measurement model. Parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood (ML), and model adequacy was assessed through widely used fit indices, including CMIN/DF, GFI, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA [

40,

43]. This step ensured that the latent constructs demonstrated satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity.

Following validation of the measurement model, SEM was applied to test the theoretical hypotheses. SEM is particularly suited for models involving multiple predictors and complex mediation structures [

44], as in the present study, which includes three predictors (NV, SI, HNI), two mediators (CN, PA), and one outcome variable (UWB).

Finally, the significance of the mediation effects was examined using a bias-corrected bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples to obtain robust confidence intervals [

45]. This approach allows simultaneous testing of both parallel and serial mediation effects and is well suited for evaluating the psychological pathways proposed in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Validity Analysis

To verify the structural validity of the measurement data, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted using SPSS 30.0. As shown in

Table 3, the KMO value of the scale was 0.929, which is well above the recommended threshold of 0.80, indicating that the sample size was adequate and the data were suitable for factor analysis. Meanwhile, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded an approximate chi-square value of 13,854.183 (

= 351,

p < 0.001), reaching a significant level and suggesting strong correlations among the variables. Taken together, these results indicate that the dataset was appropriate for factor analysis, providing solid statistical support for subsequent exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses.

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To further verify the structural rationality of the scale, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was conducted as the method of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA).

Based on Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalues greater than 1), six common factors were extracted, with a cumulative variance explanation rate of 70.871%. This indicates that the extracted factors effectively captured the overall structure of the scale and demonstrated strong explanatory power.

As shown in

Table 4, the variance contributions of the six rotated factors were 12.778%, 12.373%, 11.941%, 11.524%, 11.280%, and 10.974%, respectively. The distribution of factor loadings was balanced and clearly structured, with no substantial cross-loadings observed, suggesting stable item-factor associations and good construct validity of the measurement scale.

Therefore, subsequent Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were conducted based on this established factor structure.

As shown in the rotated component matrix (

Table 5), all measurement items exhibited factor loadings greater than 0.70 and communalities above 0.60, indicating strong correlations between the observed items and their corresponding latent variables, as well as stable and reliable structural properties. After Varimax rotation, the loadings of all items were well-clustered under their respective factors without significant cross-loadings, further confirming the structural validity of the scale.

These results demonstrate a high level of consistency between the measurement dimensions and the theoretical constructs, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis, CFA

As shown in

Table 6, the value of CMIN/DF was 2.481, while the indices GFI, AGFI, NFI, TLI, IFI, and CFI all exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.90. The RMSEA value was 0.042, which is below the acceptable limit of 0.08. Since most of the model fit indices met the general standards of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), it can be concluded that the measurement model demonstrated a satisfactory goodness of fit.

As shown in

Table 7, all standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.50 and were statistically significant, indicating that each item was strongly associated with its corresponding latent construct. The Composite Reliability (CR) values were all greater than 0.70, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were all above 0.50, meeting the criteria for convergent validity. These results demonstrate that the measurement model possesses satisfactory reliability and convergent validity.

To examine the discriminant validity of the model, the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (

) for each latent variable and the Pearson correlation coefficients among the variables were calculated, as shown in

Table 8. The results indicate that the

values on the diagonal (ranging from 0.757 to 0.827) were all higher than the corresponding inter-construct correlation coefficients (the highest correlation being 0.571). This demonstrates good discriminant validity among the constructs. Although significant correlations exist among the variables, no issue of multicollinearity was observed. Therefore, the model meets the Fornell and Larcker [

46] criterion for discriminant validity.

4.4. Common Method Bias Test

To control for potential common method bias, both Harman’s single-factor test and model verification approaches were employed in this study. First, the results of the exploratory factor analysis revealed that six factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor explaining only 12.78% of the total variance—well below the critical threshold of 40%, indicating the absence of significant single-factor bias.

Furthermore, during the confirmatory factor analysis stage, a method factor model was introduced for robustness testing. The results demonstrated a good model fit:

CMIN/DF = 2.481 (<3), GFI = 0.941, AGFI = 0.928, NFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.962, IFI = 0.967, CFI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.042 (<0.08), SRMR = 0.027 (<0.05). Most indices met or exceeded the recommended criteria, suggesting satisfactory overall model fit.

In summary, the findings indicate that no significant common method bias was detected, confirming that the measurement results were reliable and minimally affected by single-source error.

4.5. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of the Variables

As shown in

Table 9, natural visibility had a significant positive effect on connectedness to nature (

= 0.185,

p < 0.001), spatial integration also had a significant positive effect on connectedness to nature (

= 0.267,

p < 0.001), and human–nature interactivity showed a significant positive effect as well (

= 0.427,

p < 0.001). The model explained 46.1% of the variance in connectedness to nature.

Natural visibility had a significant positive effect on place attachment ( = 0.166, p < 0.001), spatial integration had a significant positive effect ( = 0.245, p < 0.001), human–nature interactivity had a significant positive effect ( = 0.218, p < 0.001), and connectedness to nature also had a significant positive effect on place attachment ( = 0.225, p < 0.001). The model explained 42.2% of the variance in place attachment.

Furthermore, natural visibility ( = 0.084, p < 0.05), spatial integration ( = 0.103, p < 0.01), and human–nature interactivity ( = 0.103, p < 0.01) all had significant positive effects on urban well-being. In addition, connectedness to nature ( = 0.336, p < 0.001) and place attachment ( = 0.315, p < 0.001) were also found to significantly enhance urban well-being. The model explained 56.1% of the variance in urban well-being.

4.6. Mediation Analysis

To test the mediation effects, this study employed the BOOTSTRAP method in AMOS, using the Bias-Corrected approach with 5000 resamples. The results are presented in

Table 10.

As shown in

Table 10, the direct effect of natural visibility (NV) on urban well-being (UWB) was 0.084 (95% CI [0.011, 0.155]), which was significant as the confidence interval did not include zero. The indirect effect through connectedness to nature (CN) was 0.062 (95% CI [0.036, 0.096]), and through place attachment (PA) was 0.052 (95% CI [0.029, 0.083]); both effects were significant. The sequential mediation through connectedness to nature and place attachment was 0.013 (95% CI [0.007, 0.023]), also significant.

The total indirect effect was 0.128, accounting for 60.4% of the total effect. These findings indicate that connectedness to nature and place attachment played significant parallel and sequential mediating roles in the relationship between natural visibility and urban well-being.

As shown in

Table 11, the direct effect of spatial integration (SI) on urban well-being (UWB) was 0.103 (95% CI [0.029, 0.174]), which was significant since the confidence interval did not include zero. The indirect effect through connectedness to nature (CN) was 0.090 (95% CI [0.059, 0.126]), and through place attachment (PA) was 0.077 (95% CI [0.051, 0.110]); both effects were significant. The sequential mediation through connectedness to nature and place attachment was 0.019 (95% CI [0.011, 0.031]), also significant.

The total indirect effect was 0.186, accounting for 64.4% of the total effect. These results indicate that connectedness to nature and place attachment exerted significant parallel and sequential mediating effects in the relationship between spatial integration and urban well-being.

As shown in

Table 12, the direct effect of human–nature interactivity (HNI) on urban well-being (UWB) was 0.103 (95% CI [0.027, 0.182]), which was significant as the confidence interval did not include zero. The indirect effect through connectedness to nature (CN) was 0.144 (95% CI [0.103, 0.191]), and through place attachment (PA) was 0.069 (95% CI [0.039, 0.104]); both were significant. The sequential mediation through connectedness to nature and place attachment was 0.030 (95% CI [0.018, 0.047]), also significant.

The total indirect effect was 0.242, accounting for 70.1% of the total effect. These findings indicate that connectedness to nature and place attachment exerted significant parallel and sequential mediating effects in the relationship between human–nature interactivity and urban well-being. The validated structural model is shown in

Figure 2.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution and Mechanism Deepening

This study deepens the understanding of how natural design features in nature-based sports venues contribute to urban well-being, advancing theoretical discussions at the intersection of environmental psychology and sports architecture. The results show that Natural Visibility (NV), Spatial Integration (SI), and Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI) shape urban well-being through two psychological pathways—Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA). These findings affirm that both cognitive and affective processes jointly underpin the psychological benefits derived from nature-oriented design, offering empirical support for the dual-path mechanism frequently referenced in built-environment research.

The study highlights how cognitive and affective systems operate in parallel during human–environment interaction. Within nature-based sports venues, individuals simultaneously engage in cognitive appraisal—such as evaluating spatial coherence and the integration of natural elements—and experience immediate emotional responses elicited by light, vegetation, and water. These intertwined processes collectively shape individuals’ attachment to the venue and their sense of well-being.

The findings also introduce a temporal perspective to dual-process explanations. Nature-based sports venues, as high-frequency activity spaces, provide repeated exposure that gradually strengthens individuals’ cognitive links with nature. Meanwhile, affective responses remain relatively stable over time, exerting continuous influence on emotional tendencies and place identity. This pattern reflects a dynamic interplay in which cognitive connections accumulate while emotional responses maintain consistency, offering new insight into how environmental features influence well-being across time.

Furthermore, the study identifies Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI) as a distinct component of natural experience, expanding beyond prior research that primarily emphasized visual perception. Active engagement with natural elements facilitates reciprocal reinforcement between cognitive and emotional systems, enhancing both Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA) and ultimately improving well-being. This contribution broadens existing theoretical frameworks in environmental psychology and underscores the need for future research to further explore behavioral interaction as a key dimension of nature experience.

5.2. Dialogue and Expansion with Existing Studies

The findings of this study extend current international research on natural environments, spatial quality, and subjective well-being by offering deeper theoretical dialogue. Prior studies have consistently shown that natural visibility, landscape openness, and spatial coherence play important roles in enhancing psychological health, largely by improving natural exposure and spatial continuity [

5]. Within the context of nature-based sports venues, the present study confirms this relationship and demonstrates that Natural Visibility (NV), Spatial Integration (SI), and Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI) jointly form an integrated set of natural design features that influence Urban Well-being (UWB) through multiple perceptual channels.

For example, previous research has shown that natural visibility and spatial integration can enhance emotional connection, which subsequently promotes well-being [

47]. A similar mechanism is evident in the present study: natural design features do not directly influence Urban Well-Being (UWB) but exert their effects indirectly by shaping Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA). This highlights the central role of users’ subjective perceptions of naturalized spaces in determining well-being outcomes.

Additionally, the findings extend the perspective provided in [

2], which demonstrated that landscape openness, environmental coherence, and recreational experience jointly shape residents’ perceptions of waterfront environments. In the context of sports venues, the present study shows that Spatial Integration (SI) and Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI) not only enhance perceived environmental vitality but also significantly strengthen CN and reinforce PA, jointly contributing to higher UWB. These results suggest that perceptual pathways—such as natural visibility, spatial continuity, and interaction with natural elements—may have a more direct influence on CN and PA than physical design attributes alone. Given that nature-based sports venues are high-frequency daily activity spaces, their natural design provides not only functional benefits but also sustained emotional attachment through repeated psychological engagement.

With respect to mediation mechanisms, the results support the proposition that CN functions as a cognitive–affective bridge between natural environments and well-being [

10]. In this study, CN operates both as an independent mediator and as the initial link in a serial pathway through PA, forming a continuous psychological chain from cognitive identification to emotional bonding and ultimately to enhanced UWB.

Notably, the findings diverge from evidence reported in [

35], which suggested that perceived natural connection did not significantly predict user satisfaction in wood-structured sports venues. By incorporating HNI into the analytical model, the present study shows that interactive engagement with natural elements can substantially reinforce the linkage between cognitive and affective systems, thereby influencing well-being outcomes. This underscores the importance of interaction-based experiences as a critical—yet often overlooked—dimension that may explain inconsistencies across previous studies.

Overall, this study not only advances theoretical understanding of how natural environments relate to psychological well-being but also demonstrates the unique value of nature-based sports venues in strengthening CN, enhancing PA, and promoting UWB.

5.3. Practical Implications and Management Insights

The findings of this study provide clear implications for sports venue design and urban space management. Users’ subjective perceptions of natural features—including Natural Visibility (NV), Spatial Integration (SI), and Human–Nature Interactivity (HNI)—were found to be central contributors to Urban Well-Being (UWB). This aligns with previous evidence showing the importance of natural exposure for psychological restoration [

5,

21]. The mediating roles of Connectedness to Nature (CN) and Place Attachment (PA) further support theoretical perspectives on how natural environments shape emotional and cognitive responses [

2,

10].

In practical terms, the study highlights three design strategies: enhancing NV through clear visual corridors and layered natural views; improving SI by integrating semi-open interfaces, material gradients, and smooth landscape transitions; and strengthening HNI through diverse opportunities for direct nature engagement across activity zones. These perceptual qualities may influence users’ evaluations as strongly as physical environmental attributes, resonating with insights from previous research results [

35].

6. Shortcomings and Prospects

Although this study achieved meaningful results in revealing the mechanism by which natural design features of nature-based sports venues influence urban well-being, several limitations should be acknowledged.

The sample was primarily drawn from China’s coastal regions, without including inland areas or venues from different climatic zones. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings remains limited. Future studies should conduct comparative analyses across diverse geographic environments to enhance the external validity and universality of the model.

The study adopted a cross-sectional design, which cannot capture the dynamic process underlying the formation of well-being. Subsequent research may employ longitudinal tracking or experimental designs to explore how the cognitive and affective pathways evolve over time.

The measurements relied mainly on self-reported data and did not differentiate between specific design elements. Future research could integrate methods such as virtual reality (VR) simulation, physiological feedback, or behavioral observation to examine the psychological effects of distinct natural design features more precisely. Moreover, this study did not fully consider the moderating effects of cultural and social factors. Future research could adopt cross-cultural comparative approaches or socio-ecological perspectives to investigate how cultural contexts shape the relationship between natural experience and well-being.

Overall, future research should expand in terms of sample diversity, methodological design, and cultural scope, thereby refining and enriching the theoretical framework connecting nature-oriented design and urban well-being.

7. Conclusions

This study focused on nature-based sports venues and, grounded in environmental psychology and place attachment theory, developed a dual-mediation model incorporating connectedness to nature and place attachment to systematically reveal the mechanism by which natural design features influence urban well-being. The results showed that natural visibility, spatial integration, and human–nature interactivity all exerted significant positive effects on urban well-being. Meanwhile, connectedness to nature and place attachment demonstrated significant parallel and sequential mediating effects across all three paths, indicating that natural design enhances individual well-being through both rational cognitive processes and affective attachment mechanisms that evoke positive psychological experiences.

These findings further validate the applicability of the cognition–emotion dual-path mechanism within the context of nature-based sports venues. The results highlight that rational evaluation and emotional experience play equally important roles in shaping well-being, jointly contributing to positive psychological responses in human–environment interactions. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on visual perception or spatial integration, this study, for the first time, incorporated human–nature interactivity into a quantitative framework of natural design, revealing the crucial role of the behavioral dimension of natural experience in promoting well-being. This extension not only compensates for the lack of behavioral participation perspectives in traditional natural design research but also provides new empirical evidence for integrative modeling of psychological mechanisms in natural environments.

At the theoretical level, this study deepens the conceptual understanding of the relationship between nature-oriented design and urban well-being, offering a new perspective for exploring psychological mechanisms within the built environment. At the practical level, the results emphasize that nature-based design should be a central principle in the development of sports venues and urban public spaces. By optimizing natural visibility, enhancing spatial integration, and enriching human–nature interactive experiences, designers and planners can effectively foster emotional connection and psychological restoration, thereby improving residents’ overall well-being.

In summary, this study provides a systematic theoretical framework for understanding the psychological benefits of nature-based sports venues, while also offering practical insights for the health-oriented and human-centered transformation of urban sports architecture. Future research may further explore the long-term effects and dynamic mechanisms of natural experiences on well-being across different cultural contexts, social interactions, and temporal dimensions.

For transparency, the authors note that AI-based tools were used solely to assist with language editing after the completion of the study; all content was reviewed by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and W.L.; Methodology, Z.Z. and W.L.; Software development, Z.Z. and L.D.; Validation, Z.Z. and L.D.; Formal analysis, W.L.; Investigation and field work, Z.Z. and L.D.; Resources provision, W.L. and J.Q.; Data curation, W.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z. and W.L.; Visualization and figure preparation, L.D.; Supervision and project guidance, W.L. and J.Q.; Project administration, W.L. and J.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ludong university (Approval No.: IRBLDU20250616, approval date: 16 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the Z.Z.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for the purposes of language editing and improving readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Veenhoven, R.; Chiperi, F.; Kang, X.; Burger, M. Happiness and consumption: A research synthesis using an online finding archive. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 2158244020986239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, Y. How Do Ecological and Recreational Features of Waterfront Space Affect Its Vitality? Developing Coupling Coordination and Enhancing Waterfront Vitality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahart, I.; Darcy, P.; Gidlow, C.; Calogiuri, G. The effects of green exercise on physical and mental wellbeing: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green Space as a Buffer Between Stressful Life Events and Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; van den Berg, P.E.W.; Ossokina, I.V.; Arentze, T.A. How do urban parks, neighborhood open spaces, and private gardens relate to individuals’ subjective well-being: Results of a structural equation model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105094. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.-H.; Guo, S.-T.; Feng, X.-W.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Nor, M.N.M.; Abidin, N.E.Z. Sustainable development between sports facilities and ecological environment based on the dual carbon background. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22692. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Happiness: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernández, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, W.; Kang, N.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Xia, Y. Serial Mediation of Environmental Preference and Place Attachment in the Relationship Between Perceived Street Walkability and Mood of the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusli, N.A.N.M.; Roslan, S.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ghiami, Z.; Ahmad, N. Role of restorativeness in improving the psychological well-being of university students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. World Database of Happiness: A ‘Findings Archive’. In Global Handbook of Quality of Life; Glatzer, W., Camfield, L., Møller, V., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 287–314. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Coastal Proximity, Health and Well-Being: Results from a Longitudinal Panel Survey. Health Place 2013, 23, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Hallmann, K.; Breuer, C. Micro and macro level determinants of sport participation. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 2, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.; Calabrese, E. The Practice of Biophilic Design; Terrapin Bright Green: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Sullivan, W.C. Impact of Views to School Landscapes on Recovery from Stress and Mental Fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 148, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L.; van der Wulp, N.Y. Environmental preference and restoration: (How) are they related? J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. Measuring the public realm: A preliminary assessment of the link between public space and sense of community. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2000, 344–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Personal, Community, and Environmental Connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Butler, C.W. Nature connectedness and biophilic design. Build. Res. Inf. 2022, 50, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Kyttä, M.; Stedman, R. Sense of Place, Fast and Slow: The Potential Contributions of Affordance Theory to Sense of Place. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Hidalgo, M.C.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Du, L.; Ding, L. Enhancing place attachment through natural design in sports venues: The roles of nature connectedness and biophilia. Buildings 2025, 15, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Weinstein, N.; Bernstein, J.; Brown, K.W.; Mistretta, L.; Gagné, M. Vitalizing Effects of Being Outdoors and in Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. Concepts and measures related to connection to nature: Similarities and differences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K.V.; Kent, J.T.; Taylor, C.C. Multivariate Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Fan, L.; Huang, L.; Gao, J. Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behaviour in National Parks: The Development of a Conceptual Framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).