A Value-Based Risk Assessment of Water-Related Hazards: The Archaeological Site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Climatic Indexes of the Region

1.2. The Sanctuary of Asklepios

Past and Present-Day Condition

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exposure Estimation and Vulnerability Analysis

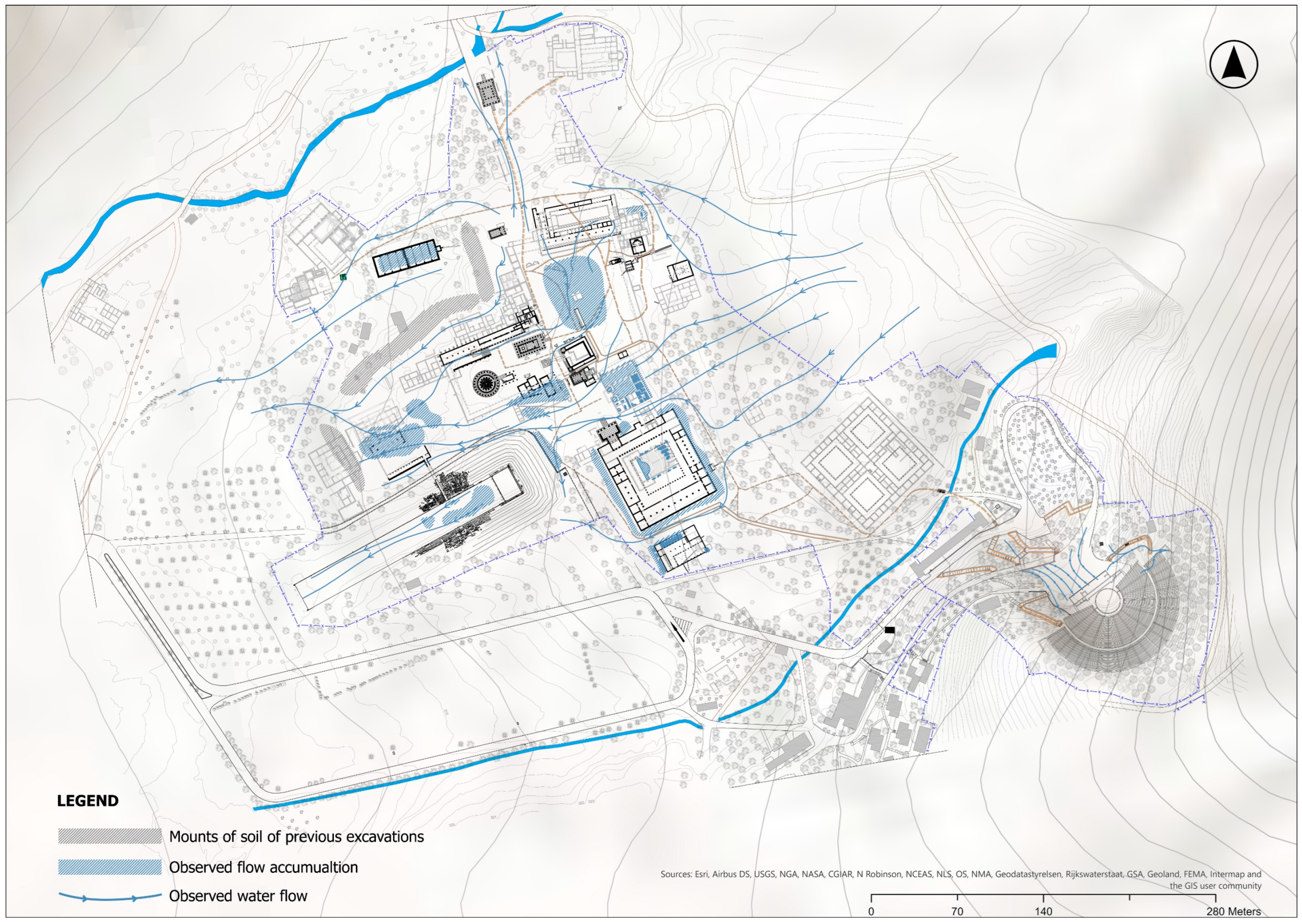

2.2. Fieldwork

2.3. The ABC Method Through a Value-Based Approach

3. Results

3.1. HAND Analysis

3.2. Findings of the Fieldwork

3.3. Vulnerability Assessment and Future Impacts

3.4. Case Analysis, Value Identification and Risk Statements

3.4.1. Theatre

3.4.2. Roman Odeion

3.4.3. Part of the Archaeological Site

3.5. Towards a Risk Assessment—The ABC Method

Evaluation of ABC Parameters

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCA | Climate Change Adaptation |

| DRM | Disaster Risk Management |

| DRR | Disaster Risk Reduction |

| HAND | Height Above Nearest Drainage |

| ICCROM | International Center for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| RPCCP | Regional Plan for Climate Change for Peloponnese |

| UNDRR | United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction |

| UNESCO | The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UNISDR | United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (International Strategy for Disaster Reduction) |

| WA | Water Accumulation |

References

- Ali, E.; Cramer, W.; Carnicer, J.; Georgopoulou, E.; Hilmi, N.J.M.; Le Cozannet, G.; Lionello, P. Cross-Chapter Paper 4: Mediterranean Region. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2233–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C. Conservation and heritage as future-making. In ICOMOS University Forum; ICOMOS International: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.T. Series of Lectures on Cultural Heritage in the 21st Century—Opportunities and Challenges; Institute Heritage Studies: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lafrenz Samuels, K.; Platts, E.J. Global Climate Change and UNESCO World Heritage. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2022, 29, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P. (Ed.) The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. xxi–xxiii. ISBN 9780124160422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS Climate Action Working Group. The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Heritage and the Climate Emergency; ICOMOS Resolution 20GA 2023/03; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sesana, E.; Gagnon, A.S.; Ciantelli, C.; Bonazza, A.; Sabbioni, C. Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: A literature review. WIREs Clim. Change 2021, 12, e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, L.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Brown, S.; Hinkel, J.; Tol, R.S.J. Mediterranean UNESCO World Heritage at risk from coastal flooding and erosion due to sea-level rise. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjurjo-Sánchez, J.; Blanco-Chao, R. Building stone weathering under Mediterranean and Eastern European climate conditions: A comparative study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Falzon, C. Climate Change Adaptation for Natural World Heritage Sites: A Practical Guide; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Greece-UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/gr (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- News247.gr. Φωτιά στις Μυκήνες: Οι φθορές και το “λίγο καμένο που θα βλέπει ο επισκέπτης”. Available online: https://www.news247.gr/ellada/fotia-stis-mikines-oi-fthores-kai-to-ligo-kameno-pou-tha-vlepei-o-episkeptis/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Ethnos.gr. Φωτιά Αρχαία Ολυμπία: «Ασπίδα» για να σωθεί ο αρχαιολογικός χώρος–Συγκλονίζουν οι εικόνες. Available online: https://www.ethnos.gr/greece/article/169068/fotiaarxaiaolympiaaspidagianasotheioarxaiologikosxorossygklonizoynoieikones (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Αρχαιολογία Online. Ο ναός του Eπικούριου Aπόλλωνα: Ο ανθρώπινος παράγων αιτία καταστροφής του μνημείου. Available online: https://www.archaiologia.gr/blog/issue/ο-ναός-του-eπικούριου-aπόλλωνα-ο-ανθρώπ/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Spathari, E. Brochure-Epidavros; Ministry of Culture: Athens, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Athens & Epidaurus Festival. History. Available online: https://aefestival.gr/history/?lang=en (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Varti-Matarangas, M.; Matarangas, D. Microfacies analysis and endogenic decay causes of carbonate building stones at the Asklepieion Epidaurus monuments of Peloponnessos, Greece. J. Cult. Herit. 2000, 1, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climascape. Ερευνητικό πρόγραμμα. Available online: http://climascape.prd.uth.gr/en/home-english/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Academy of Athens. Regional Plan for Climate Change for Peloponnese; Academy of Athens: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Climascape. Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. Available online: http://climascape.prd.uth.gr/en/sanctuary-of-asklepios-at-epidaurus (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Moragoda, N.; Kumar, M.; Cohen, S. Representing the role of soil moisture on erosion resistance in sediment models: Challenges and opportunities. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 229, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearing, M.A.; Pruski, F.F.; O’Neal, M.R. Expected climate change impacts on soil erosion rates: A review. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2004, 59, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argolikos Archival Library of History and Culture. Peloponnesus—The Ark of Hellenic Civilization. 2011. Available online: https://argolikivivliothiki.gr/2011/05/07/%CF%80%CE%B5%CE%BB%CE%BF%CF%80%CF%8C%CE%BD%CE%BD%CE%B7%CF%83%CE%BF%CF%82-%CE%B7-%CE%BA%CE%B9%CE%B2%CF%89%CF%84%CF%8C%CF%82-%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%85-%CE%B5%CE%BB%CE%BB%CE%B7%CE%BD%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%BF%CF%8D/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Argolis Culture-List of Monuments. Available online: https://www.argolisculture.gr/el/lista-mnimeion/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Lambrinoudakis, V. Το Ασκληπιείο της Επιδαύρου. Η έδρα του θεού γιατρού της αρχαιότητας. Η συντήρηση των μνημείων του; Περιφέρεια Πελοποννήσου: Athens, Greece, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, M. Οι αφίσες του ΕΟΤ τη δεκαετία του 1980. 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/38881104/%CE%9F%CE%B9_%CE%B1%CF%86%CE%AF%CF%83%CE%B5%CF%82_%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%85_%CE%95%CE%9F%CE%A4_%CF%84%CE%B7_%CE%B4%CE%B5%CE%BA%CE%B1%CE%B5%CF%84%CE%AF%CE%B1_%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%85_1980 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/491/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Presidential Decree 18.11.1983. In Government Gazette: Δ 83/1984. Available online: https://search.et.gr/el/fek/?fekId=706003 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ministerial Decision in Government Gazette: 220/AAP/15-6-2012. 2012. Available online: https://search.et.gr/el/fek/?fekId=457801 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Law No. 3028/2002. On the Protection of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in General; Article 7. Government Gazette 153/A/28-6-2002, 2002. Available online: https://search.et.gr/el/fek/?fekId=246815 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Council of Europe. Greece-Herein System. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/herein-system/greece (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Council of Europe. Greece-1. Organisations-Herein System. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/herein-system/-/greece-1-greece (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Maurommatidis, I. The ionian portico of the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, the so-called avato; National Technical University of Athens: Athens, Greece, 2021; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Periodic Reporting Cycle 2 (Section II); PR-C2-S2-491; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Periodic Reporting Cycle 3 (Section II); PR-C3-S2-4364; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, S.; Pedersoli, J. The ABC Method: A Risk Management Approach to the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Canadian Conservation Institute and ICCROM: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-0-660-04134-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. Are cultural heritage and resources threatened by climate change? A systematic literature review. Clim. Change 2017, 142, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Munasinghe, D.; Eyelade, D.; Cohen, S. An intesgrated evaluation of the National Water Model (NWM)–Height Above Nearest Drainage (HAND) flood mapping methodology. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2405–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizabal, F.; Salas, F.; Petrochenkov, G.; Grout, T.; Avant, B.; Bates, B.; Spies, R.; Chadwick, N.; Wills, Z.; Judge, J. Extending Height Above Nearest Drainage to model multiple fluvial sources in flood inundation mapping applications for the U.S. Natl. Water Model. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A.D.; Cuartas, L.A.; Momo, M.R.; Severo, D.L.; Pinheiro, A.; Nobre, C.A. HAND contour: A new proxy predictor of inundation extent. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Balen, K. The Nara grid: An evaluation scheme based on the Nara document on authenticity. APT Bull. 2008, 39, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Siedel, H. Historic building stones and flooding: Changes of physical properties due to water saturation. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2010, 24, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassoglou, N.; Tsadilas, C.; Kosmas, C. The Soils of Greece; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 9, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadat, F.M.; Taimeh, A.Y. Effect of rainfall intensity, slope, land use and antecedent soil moisture on soil erosion in an arid environment. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 24, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bank of Greece. The environmental, economic and social impacts of climate change on Greece. Natl. Bank Greece 2011, 127–315. Available online: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the-bank/social-responsibility/sustainability-and-climate-change/ccisc/research (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Maurommatidis, I. Οι δομικοί λίθοι του Ασκληπιείου της Επιδαύρου [The Building Stones of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus]; OESME, Ministry of Culture: Athens, Greece, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cavvadias, P. Fouilles d’Épidaure; S. C. Vlastos: Athens, Greece, 1891; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gogos, S. Das Theater Von Epidauros; Universitat Peloponnes: Wien, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boletis, K. Ιστορικό των νεότερων επεμβάσεων στο θέατρο του Ασκληπιείου Επιδαύρου και στον ευρύτερο χώρο του έως το 1989. Αρχαιολογικό Δελτίο, Ανάτυπο, Μέρος Α΄: Μελέτες, Τόμος 2002, 57, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanidis, K. The Roman Odeion at Epidaurus. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2003, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazolias, E. Προγραμμα Αποκαταστασης Ρωμαϊκου Ωδειου Ασκληπιειου Επιδαυρου [Restoration Program of the Roman Odeion of the Asklepieion of Epidaurus]; ESME, Ministry of Culture: Athens, Greece, 2009; p. 4. Available online: https://diazoma.gr/site-assets/2009-ΠΡΟΓΡΑΜΜΑ-ΑΠΟΚΑΤΑΣΤΑΣΗΣ-ΩΔΕΙΟ-ΕΠΙΔΑΥΡΟΥ.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Kyriaki, B. Το Γυμνάσιο-Τελετουργικό Εστιατόριο, κτίριο Χ,χ στο Ασκληπιείο της Επιδαύρου. Ph.D. Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulos, C. Το Υστερορωμαϊκό “τείχος”. Περίβολος τεμένους και περιμετρική στοά στο Ασκληπιείο της Επιδαύρου; OESME, Ministry of Culture: Athens, Greece, 2000; ISBN 9789608664500/978-960-86645-0-0. [Google Scholar]

- Peppa-Papaioannou, R. New Archaeological Evidence for the Water Supply and Drainage System of the Asklepieion at Epidauros. In Akten des 13; Internationalen Kongresses für Klassische Archäologie: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti, S.; Ridolfi, E.; Russo, F.; Napolitano, F. Intensity–duration–frequency curves in a data-rich era: A review. Water 2022, 14, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Annex I: Glossary. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Matthews, J.B.R., Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, H.-O., Pörtner, D., Roberts, J., Skea, P.R., Shukla, A., Pirani, W., Moufouma-Okia, C., Péan, R., et al., Eds.; An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theatre | Artistic | Historic | Social | Scientific |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form and Design | The restored and preserved parts of the ancient Theatre are a testimony to the theatrical architecture of the Hellenistic period. | An almost complete picture of its original form because of the excellent preservation of the Koilon and the orchestra. It preserves its original architectural form until the end of its function and was never transformed into a roman one. | The building typology nodes to the past social and artistic use of the space. After all, it was an integral part of the healing process of the sick and a recreational spectacle for other visitors. | It possesses such qualities and state of preservation that splendid example of Theatre architecture. |

| Materials and Substance | The great selection of stone microfacies during anastylosis ensures visual and aesthetic continuity. | The original drainage pipes of the orchestra are still in use. | Extensive research on materiality of the artefacts can contribute to the thorough understanding of the building and its missing parts. | |

| Use and Function | The Theatre is still notorious for hosting spectacular acts and Theatre plays. | The revival of the original use has boosted exponentially both the integrity and the authenticity of the site. | The Epidaurus festival is organised in the premises of the Theatre and brings together visitors and the local community. | |

| Tradition, techniques and workmanship | Rich decorative elements (stonecaps of the retaining walls and engravings of the Koilon seating) add to the design complexity. | The Theatre is closely related to the history of the development of Greek tragedy or Theatre and to Theatre architecture overall. | It is listed and protected by Diazoma—an NGO that caters for ancient Theatres throughout Greece to promote their interests by attracting sponsors. | “The complex design, planning and construction programme of the Theatre highlight the sophisticated knowledge of the workmen and the architects. |

| Location and Setting | Carved into the natural rock it feels as if it emerges out of it. The acoustics are of outstanding quality. | The Theatre has always been in the forefront of artistic innovation and is still a sought-after performance stage. | Offers unobstructed view of the sanctuary with the imposing remains visible from parts of it, even though parts of them are not in sight by vegetation. | |

| Spirit and Feeling | The original use keeps the spirit of the place alive. | The visitor attending a performance or just visiting the Theatre can still feel both its archaeological importance and its value as a landmark for artistic innovation. | Groups of visitors occupying the space sometimes have a mini lecture, while being seated at the Koilon, to invoke the qualities of the Theatre. | The combination of superb acoustics and architecture of monumental scale interest researchers who try to decipher the science behind the ethereal experience. |

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| RM_W_TH | Even though the management of the water masses affecting the Theatre during intense rainfall is adequate, the changing climatic conditions can affect its efficacy in the future, leading to more risks. |

| RM_FR_TH | A snowstorm event, even though decreasing, could lead to the generation of ice particles within the pores and the micro cracks of the weakened material and lead to major cracking. |

| Roman Odeion | Artistic | Historic | Social | Scientific |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form and Design | It is an example of a divergent Roman Odeion. The orchestra is situated lower than the side entrances featuring a floor mosaic. The access to the auditorium was made possible via the use of three staircases. | The Odeion is situated on the northern part of the complex’s courtyard incorporating its walls the columns of the interior colonnade as well as other architectural elements of the former building. | The Odeon should be dated in the end of the 2nd or early 3rd century AD. Several construction phases can be distinguished on the building, which can provide valuable insight for the comparative dating of on-site structures. | |

| Materials and Substance | The walls are made up of semi processed stones, bricks in opus mixtum and reused building stones from the original building. The bonding agent used throughout the structure are several types of mortars. | The structure typology of the Odeion during the Roman times lends itself to the need of a fast and economic construction. The interiors in raw brick and the few embellishments could also attest to this. | The analysis and cataloguing of the structural material are useful practices in tracing original material in other parts of the sanctuary. | |

| Use and Function | A comprehensive conservation and restoration plan could highlight its great reuse potential. | |||

| Tradition, Techniques, and workmanship | Example of the craftsmens’ mastery to build upon remains and selecting proper existing material to be reused to ensure structural homogeneity. Deviations to the form of the Odeion could be attributed to this -among other factors. | This building was erect to house “mystical drama” rituals which were previously held in the open space within the Gymnasium. | Tradition, techniques and workmanship | Exemplary typology deviating from the Roman Odeia of the 2nd c. A.D. |

| Location and Setting | The remains of the Odeion are an indispensable part of the palimpsest of the Gymnasium building and the Sanctuary itself. | These roman remains inform considerable parts of the historic interpretation of the sanctuary and the overall comparative study of Roman monuments. | Set in this intricate archaeological site, it could assist in the interpretation of findings of ongoing research. | |

| Spirit and Feeling | The original form of the building can still be distinguished easily by the visitor. | The preserved remains can still inspire a mental reconstruction of how a concert could have been experienced. | Visitors are drawn by the imposing complex of Gymnasium and they try to obtain a glimpse of the Koilon of the Odeion. |

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| RM_W_RO | The remains of the interior of the Roman Odeion that used to be sheltered from rain are now exposed. Stagnant water is, thus, accumulated and could lead to further material deterioration and loss of value. |

| RM_FR_RO | The already severely damaged archaeological remains are vulnerable to ice formation, which could further deteriorate the already compromised material. |

| Site | Artistic | Historic | Social | Scientific |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form and Design | One of the most perfect examples of healing sanctuaries of antiquity exhibiting integrity of the inscribed values, authenticity and sane restoration works. | Exhibits all the various consecutive phases and latter transformations to accommodate the needs of each consecutive era. | Research conducted on key monuments has been published, providing didactic content all types of publics—from laypeople to fellow researchers. | The layout and the remains within the site provide insight in various temporal and spatial scales. |

| Materials and Substance | The site has witnessed various conservation and restoration works which add to the multilayered reading of the site. | The site is rich in artefacts that are yet to be excavated. | ||

| Use and Function | The remains of the buildings still retain the basic spatial planning principles of the latest phase of the sanctuary. | The sanctuary’s addition to the MOREA network proves the potential of the sanctuary to influence cultural routes and to promote the interests of the surrounding communities. | ||

| Tradition, techniques and workmanship | Exemplary restoration works complement the existing remains and ensure their longevity. | The most renowned healing sanctuary of the whole Hellenic and Roman world. | Healing practices resembling modern medicine were applied there. Many deem this place to be the foundation of western medicine. | |

| Location and Setting | According to Hippocrates, the site exhibits the qualities that a sanctuary should possess pure water rising from springs and a rich landscape. | Anastylosis restored the third dimension and established the height necessary for the proper understanding of the site. | The strategic position of the sanctuary in the Argolid Peninsula, the revival and enhancement of the archaeological site provide business opportunities to the local community. | The key position of the Sanctuary of Asklepios could inform new research relevant to the development of the surrounding region and NE Peloponnese. |

| Spirit and Feeling | The artefacts’ positions within the site and the richness of the landscape enhance the narrative of the sanctuary as a place of healing. | The site was devoted to Gods with healing properties since prehistory. Specific remains still attest to this. | Visitors are still intrigued by the expansiveness of the site. The various routes within the sanctuary invite the visitors to wander around and explore. | There is the initiative of enhancing the site to gradually become an archaeological park in the long-term. Few of the incentives are the restoration of key monuments and the reinstitution of the proper entrance to the sanctuary—as it was during its heyday. |

| ID | Description |

|---|---|

| RM_W_SI | Water reels and channels are formed during intense rainfall originating from NE of the site and accumulating to the W. The constant change between flow and accumulation can lead to mass deposition, accelerate erosion processes and affect buried artefacts on the western part. As a result, major potential for systematic research will be lost. |

| RM_FR_SI | The compromised archaeological remains scattered in the western part of the site already exhibit heavy damage and they are at the point of losing value. Future frost damage can lead to complete loss of value. |

| Group | Group as % of Asset | Value subgroup (NARA Dimensions) | Number of Items in Value Subgroup | Subgroup as % of Group (NARA Aspects Out of 6) | Subgroup as % of Asset | Item as % of Asset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 30 | TH—Artistic | 6 | 28.58 | 8.574 | 1.429 |

| Theatre | 30 | TH—Historic | 6 | 28.58 | 8.574 | 1.429 |

| Theatre | 30 | TH—Social | 5 | 23.8 | 7.14 | 1.428 |

| Theatre | 30 | TH—Scientific | 4 | 19.04 | 5.712 | 1.428 |

| Roman Odeion | 20 | RO—Artistic | 5 | 31.25 | 6.25 | 1.25 |

| Roman Odeion | 20 | RO—Historic | 5 | 31.25 | 6.25 | 1.25 |

| Roman Odeion | 20 | RO—Social | 1 | 6.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Roman Odeion | 20 | RO—Scientific | 5 | 31.25 | 6.25 | 1.25 |

| Site | 50 | SI—Artistic | 4 | 21.05 | 10.52 | 2.63 |

| Site | 50 | SI—Historic | 6 | 31.57 | 15.785 | 2.63 |

| Site | 50 | SI—Social | 4 | 21.06 | 10.52 | 2.63 |

| Site | 50 | SI—Scientific | 5 | 26.32 | 13.16 | 2.63 |

| Affected Items Water Modes | Item as % of Asset | Number of Items Affected by This Risk | Fraction of Asset Value Affected | C Score on ½-Step Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH—Artistic | 1.429 | 3 | 4.287 | 3½ |

| TH—Historic | 1.429 | 1 | 1.429 | 3 |

| TH—Social | 1.428 | 2 | 2.858 | 3½ |

| TH—Scientific | 1.428 | 2 | 2.858 | 3½ |

| ΣTH: | 11.432 | 4 | ||

| RO—Artistic | 1.25 | 3 | 3.75 | 3½ |

| RO—Historic | 1.25 | 2 | 2.5 | 3½ |

| RO—Social | 1.25 | _ | _ | _ |

| RO—Scientific | 1.25 | 3 | 3.75 | 3½ |

| ΣRO: | 10 | 4 | ||

| SI—Artistic | 2.63 | 2 | 5.26 | 3½ |

| SI—Historic | 2.63 | 3 | 7.89 | 4 |

| SI—Social | 2.63 | 1 | 2.63 | 3½ |

| SI—Scientific | 2.63 | 2 | 5.26 | 3½ |

| ΣSI: | 21.04 | 4½ |

| Affected Items Ice | Item as % of Asset | Number of Items Affected by This Risk | Fraction of Asset Value Affected | C score on ½-Step Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TH—Artistic | 1.429 | 1 | 1.429 | 3½ |

| TH—Historic | 1.429 | _ | _ | 3 |

| TH—Social | 1.428 | 1 | 1.429 | 3½ |

| TH—Scientific | 1.428 | _ | _ | 3½ |

| ΣTH: | 2.858 | 3 | ||

| RO—Artistic | 1.25 | 2 | 2.5 | 3½ |

| RO—Historic | 1.25 | 2 | 2.5 | 3½ |

| RO—Social | 1.25 | _ | _ | _ |

| RO—Scientific | 1.25 | 1 | 1.25 | 3½ |

| ΣRO: | 6.25 | 4 | ||

| SI—Artistic | 2.63 | 1 | 2.63 | 3½ |

| SI—Historic | 2.63 | 1 | 2.63 | 4 |

| SI—Social | 2.63 | _ | _ | 3½ |

| SI—Scientific | 2.63 | _ | _ | 3½ |

| ΣSI: | 5.26 | 3½ |

| Water Damage | Score | Number of Damaged Items Equivalent to One Total Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 2 | ~500 |

| Roman Odeion | 3½ | ~30 |

| Site | 4 | ~8 |

| Frost Damage | Score | Number of Damaged Items Equivalent to One Total Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 2½ | ~300 |

| Roman Odeion | 4½ | ~7 |

| Site | 4 | ~10 |

| Water Damage | Score | Number of Damaged Items Equivalent to One Total Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 2½ | ~200 |

| Roman Odeion | 4 | ~10 |

| Site | 4½ | ~5 |

| Frost Damage | Score | Number of Damaged Items Equivalent to One Total Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Theatre | 2 | ~400 |

| Roman Odeion | 3 | ~50 |

| Site | 3½ | ~25 |

| Risk Types for the 2065 Timeframe | Risk Magnitudes |

|---|---|

| Risks related to water damage | RM_W_TH = A × B × C = 3 × 2 × 4 = 24 |

| RM_W_RO = A × B × C = 3 × 3½ × 4 = 42 | |

| RM_W_SI = A × B × C = 3 × 4 × 4½ = 54 | |

| Risks related to frost damage | RM_FR_TH = A × B × C = 3 × 2½ × 3 = 22.5 |

| RM_FR_RO = A × B × C = 3 × 4½ × 4 = 54 | |

| RM_FR_SI = A × B × C = 3 × 4 × 3½ = 42 |

| Risk Types for the 2100 Timeframe | Risk Magnitudes |

|---|---|

| Risks related to water damage | RM_W_TH = A × B × C = 3½ × 2½ × 4 = 35 |

| RM_W_RO = A × B × C = 3½ × 4 × 4 = 56 | |

| RM_W_SI = A × B × C = 3½ × 4½ × 4½ = 70.875 | |

| Risks related to frost damage | RM_FR_TH = A × B × C = 3½ × 2 × 3 = 21 |

| RM_FR_RO = A × B × C = 3½ × 3 × 4 = 42 | |

| RM_FR_SI = A × B × C = 3½ × 3½ × 3½ = 42.875 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balatsoukas, A.; Miltiadou-Fezans, A.; Van Balen, K.; Kazolias, E. A Value-Based Risk Assessment of Water-Related Hazards: The Archaeological Site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. Buildings 2025, 15, 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244573

Balatsoukas A, Miltiadou-Fezans A, Van Balen K, Kazolias E. A Value-Based Risk Assessment of Water-Related Hazards: The Archaeological Site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244573

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalatsoukas, Argyrios, Androniki Miltiadou-Fezans, Koenraad Van Balen, and Evagelos Kazolias. 2025. "A Value-Based Risk Assessment of Water-Related Hazards: The Archaeological Site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244573

APA StyleBalatsoukas, A., Miltiadou-Fezans, A., Van Balen, K., & Kazolias, E. (2025). A Value-Based Risk Assessment of Water-Related Hazards: The Archaeological Site of the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus. Buildings, 15(24), 4573. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244573