1. Introduction

In recent years, environmental concerns have attracted significant global attention, influencing not only the quality of life but also the sustainable development of the global economy and human society. Excessive CO

2 emissions contribute to global warming, intensifying climate change and exerting profound effects on the environment, economy, and society [

1]. As global climate change intensifies and the energy crisis deepens, the construction industry, being a major source of energy consumption and carbon emissions, faces immense pressure to reduce emissions. In 2020, the Chinese government pledged to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, which is a goal requiring cross-sectoral support.

According to the IEA, building operations and construction account for about 40% of global energy consumption and approximately 30% of greenhouse gas emissions [

2]. In buildings, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) contribute the most to operational energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [

3]. International policy frameworks further emphasize the importance of building energy reduction and efficiency. The European Union’s revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) sets stringent targets for new buildings in Europe, requiring all new constructions to achieve zero-emission standards by 2030 with no on-site fossil fuel carbon emissions, providing a reference for China’s energy conservation and emissions reduction policies [

4]. With rapid industrialization and urbanization, domestic demand for heating and cooling has increased annually. In most regions, air conditioning systems paired with municipal heating networks (hereafter “traditional systems”) are the predominant mode. Although air conditioning is energy-efficient, municipal heating relies on coal-fired boilers for energy supply. The IEA reports that global energy-related CO

2 emissions reached 33.28 billion tons in 2019, with fossil fuels accounting for 86.3% of these emissions. Coal alone contributed 40.1%, and in China, coal accounted for 70.8% of CO

2 emissions [

5]. While coal combustion meets heating needs, its significant environmental impact and CO

2 emissions pose challenges to China’s carbon peak and neutrality goals.

Consequently, the development and promotion of energy-efficient, low-emission technologies in buildings are critical measures in combating climate change and pivotal for China’s achievement of its carbon goals. The potential for energy savings and emissions reduction in the building sector is substantial [

6]. Heat pumps, which harness primary energy from natural sources, play a crucial role in long-term carbon emissions reduction. Recognized for their efficiency, energy-saving capabilities, and eco-friendliness, heat pump technology has become an essential solution for reducing building energy consumption and emissions [

7]. Recent projections suggest that widespread deployment of heat pump technologies for heating and cooling electrification could reduce direct CO

2 emissions from Chinese buildings by 75% by 2050 [

8]. This marks a fundamental departure from the conventional coal-based district heating model, which, despite its effectiveness in satisfying thermal loads, remains a principal contributor to urban air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions in Northern China.

GSHPs are considered an attractive technology for utilizing shallow geothermal energy [

9,

10]. In contrast to air source heat pumps (ASHPs), which experience substantial efficiency degradation under severe winter conditions, leveraging stable underground temperatures throughout the year, GSHPs provide high efficiency in all seasons. Compared to standard household technologies, GSHPs deliver superior comfort, reduced noise, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and less electricity consumption [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, the environmental benefits of electrification are inextricably linked to the carbon intensity of the local power grid. In provinces such as Shandong, where the grid remains dominated by thermal power generation, the net carbon reduction potential of GSHPs compared to advanced coal-fired boilers requires rigorous empirical verification rather than assumption.

To accurately evaluate these impacts, life cycle assessment (LCA) provides the standard methodological framework [

16], quantifying environmental impacts from “cradle-to-grave” across a product’s or system’s entire life cycle [

17,

18]. By quantifying energy consumption, material usage, and waste management, LCA highlights differences in environmental impacts among various heating and cooling systems, offering scientific guidance for decision-makers [

19]. Moreover, applying LCA can also provide detailed quantitative insights into GSHP carbon emissions, facilitating the development of optimized energy strategies [

2].

While the literature on HVAC LCA is extensive, significant research gaps persist regarding GSHP applications in China’s rapid urbanization context. Critically, most existing LCA studies of GSHP systems have been conducted in European or North American contexts, where climate conditions, energy infrastructure, and building characteristics differ substantially from those in Northern China. Furthermore, many studies rely on simulated data or incomplete system inventories rather than comprehensive data from actual projects. The lack of region-specific, empirically grounded LCA studies limits our understanding of GSHP environmental performance in China’s unique context, where coal-intensive electricity generation and severe winter heating demands create distinct environmental challenges and opportunities.

To bridge this empirical gap, this study presents a comprehensive LCA of a residential GSHP system in Jinan, China, utilizing detailed bill-of-quantities data from an actual installation. By comparing this system against traditional HVAC configurations, this research aims to (1) quantify the cradle-to-grave carbon emissions of both systems using region-specific emissions factors for the Northern China Grid; (2) assess the sensitivity of environmental performance to future grid decarbonization scenarios; and (3) evaluate the economic viability of GSHP systems, thereby providing a reference framework for policy decisions in China’s cold climate zones.

2. Literature Review

The environmental benchmarking of HVAC systems has evolved from simple energy analysis to comprehensive life cycle impact assessment. Existing research has extensively quantified the energy performance of GSHP systems, consistently emphasizing their advantages over conventional technologies. For instance, in terms of energy consumption, Kim et al. [

20] found that GSHP could reduce energy consumption by 30% to 50% compared to traditional gas boilers and air conditioning systems. Bayer et al. [

14] also noted that GSHP under typical European climates achieved energy savings between 40% and 70%. Franzen et al. [

21] evaluated the environmental impact of three HVAC energy solutions in Sweden: traditional district heating and cooling, smart air conditioning systems, and geothermal energy. Their findings indicated a 61% reduction in energy consumption and a 12% cut in emissions for smart systems, and a 70% reduction in energy use with a 20% emissions reduction for geothermal solutions compared to traditional methods. Similarly, Blum et al. [

22] analyzed 1,105 GSHP systems in southwestern Germany and found emissions reductions between 35% and 72% depending on the energy mix, demonstrating the significant influence of regional electricity generation sources on GSHP environmental performance. From an economic perspective, Hanova et al. [

23] showed that GSHP energy consumption is only 25% to 30% compared to traditional systems, making them economically viable amid energy price fluctuations and climate challenges.

Several studies have applied LCA to compare GSHP systems with alternative heating and cooling technologies, revealing important insights into their relative environmental performance across different life cycle stages. Greening and Azapagic [

24] conducted a life cycle comparison of air source, ground source, water source heat pumps, and gas boilers in the UK, finding that air and water source heat pumps had the most significant environmental impact. Violante et al. [

25] used the SimaPro9.0 software to assess damage-oriented impacts across the life cycle of GSHPs and air-source heat pumps, finding that GSHP systems have greater impacts during production and installation, while air-source heat pumps have higher impacts during operation. The balance between initial investment and operational impacts highlights the critical importance of comprehensive life cycle assessment in evaluating environmental performance. Li et al. [

26], based on the TRNSYS simulation platform, conducted a comprehensive environmental impact assessment of absorption solar-assisted GSHPs and vapor compression GSHPs, demonstrating how hybrid systems can further enhance environmental benefits.

Research has identified several critical factors that influence the environmental performance of GSHP systems, particularly the electricity generation mix and the temporal dynamics of environmental impacts. Smith et al. [

27] assessed GSHP in New Jersey, USA to evaluate system effectiveness within the state’s energy mix. Their findings indicated that residential GSHP were suitable for deployment, and increased use of renewable energy would enhance efficiency and further cut emissions. Zhai et al. [

28], applying the Recipe 2016 method under the LCA framework, revealed that CO

2 emissions from electricity generation had the most significant impact on global warming and human health. GSHPs reduced energy use and carbon emissions by 40.53% and 35.23%, respectively, compared to coal-based systems. This finding is particularly relevant for China, where coal still dominates the electricity generation mix. Liang et al. [

29], through a dynamic LCA approach, found that electricity supply during the operational phase typically dominates environmental impacts, with improvements in electricity generation processes playing a critical role in mitigating most impact categories. This suggests that the environmental benefits of GSHP systems in China will increase substantially as the national electricity grid transitions toward renewable energy sources.

Despite the growing body of LCA research on GSHP systems, several important gaps remain, particularly in the Chinese context. Moreover, most regional studies rely on theoretical models or surveys with generalized inventories. Rigorous LCA studies based on actual bill-of-quantities data are lacking. For example, Huang and Mauerhofer [

30] conducted a life cycle sustainability assessment of GSHP systems based on questionnaire surveys of 20 cases in Shanghai, China. However, the inventory of the surveyed systems was unclear, hindering the assessment of result reliability. Regarding grid transition sensitivity, few studies have dynamically modeled how the rapid decarbonization of China’s power grid will alter the carbon reduction efficiency of GSHP systems.

Therefore, this study conducts an LCA investigation of GSHP systems based on project data to quantify the environmental impacts of carbon emissions from both GSHP and traditional systems in providing heating and cooling, and to explore approaches for further reducing GSHP system carbon emissions, thereby providing valuable support for achieving building energy conservation and emissions reduction goals through GSHP system utilization.

4. Case Study

Conducting a case study of an actual project allows for a clearer comparison of the application effectiveness and carbon emissions of ground source heat pump systems versus traditional systems in buildings. An illustrative case study is presented as follows:

The project analyzed in this study is located in Jinan, Shandong Province, and the building type is residential, with a total building area of 88,272.53 m2, including an underground area of 26,200.97 m2 and an above-ground area of 62,071.03 m2. Based on the heat load index of 35 W/m2 and the cooling load index of 55 W/m2 provided by the client, the total heat load for the system is approximately 2172 kW, and the total cooling load is 2200 kW. The GSHP system employs two screw-type heat pump units. Each unit has a cooling capacity of 880 kW and a heating capacity of 943 kW; COP is 5.8; EER is 4. The underground heat exchanger consists of 190 boreholes, each with a depth of 117 m. The traditional system uses cast iron radiators and 1.5 HP residential air conditioners with an EER of 3.1, and uses coal-fired heating rather than mixed-fuel heating.

The building envelope parameters are presented in

Table 5. Based on the equipment parameters provided by manufacturers and the local meteorological and geological conditions in Jinan, the subsurface temperature at the depth of the ground heat exchangers remains within the suitable operating range for the GSHP system in both winter and summer. The split air conditioners occasionally experience brief periods when ambient air temperature falls outside the optimal operating range in summer. Therefore, the COP and EER values mentioned above are reasonable.

4.1. Production Stage

The equipment and material data were sourced from client-provided information.

Table 6 details the specifications and carbon emissions of the equipment for both the ground source heat pump system and the traditional system.

4.2. Transportation Stage

The transportation of goods can involve four main modes: road, rail, air, and water transport. Each mode has a different energy consumption per unit of turnover, leading to varying emissions per unit of transport [

38]. In this study, construction equipment and associated components are assumed to be transported by road, with an average transport distance of 500 km (

Table 7). Both the ground source heat pump system and the traditional system are transported using 10-ton diesel trucks, with a carbon emissions factor of 0.162 kg CO

2/(t·km) [

36].

4.3. Construction Stage

Table 8 documents the vehicles used for drilling operations, the construction phase, grouting and filling boreholes with cement mortar, and excavating and backfilling trenches for the municipal heating network. Additionally, it records the diesel consumption of these vehicles during construction and the resulting carbon dioxide emissions.

4.4. Operation Stage

The carbon emissions generated during the operation of building cooling and heating systems are calculated using the carbon emissions factors for primary and secondary energy sources consumed by the system (

Table 9). The analysis for both systems takes into account the actual electricity mix, peak load durations [

25], design heating and cooling loads, and efficiency data.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Life Cycle Carbon Emissions

Overall, the life cycle analysis reveals that GSHP systems emit 185.30 kgCO

2e/m

2 compared to 380.47 kgCO

2e/m

2 for traditional systems over 20 years—a 51% reduction (

Table 10). While the traditional system relies on direct coal combustion (thermal efficiency < 100%) and standard air conditioners (EER ~3.1), the GSHP system leverages stable underground temperatures to achieve a COP of 5.8. This means that even with a coal-heavy electricity grid, the high energy efficiency ratio of GSHP effectively offsets the grid’s carbon intensity.

As shown in

Figure 3, the operational phase dominates total emissions (>85%) in both systems; traditional systems have higher production carbon emissions than GSHP systems, but account for a smaller proportion, reflecting that the steel-intensive radiator networks are overshadowed by the operational differences driven by coal combustion, making operational efficiency the primary determinant of environmental performance. These findings demonstrate that technology selection profoundly impacts building carbon footprints in coal-dependent energy grids.

Our findings of 51% to 88% carbon emissions reduction align well with European studies. Blum et al. [

22] reported GSHP carbon reduction potential ranging from 35% to 72%, while Saner et al. [

40] found that GSHP systems in Europe could achieve carbon savings of 31% to 88% compared to traditional heating systems. Smith et al.’s study [

27] in New Jersey, USA also evaluated the system effectiveness of GSHP within the local energy mix. Despite the different grid structures compared to this study, it similarly emphasized the synergistic relationship between GSHP and grid decarbonization. This cross-context consistency validates GSHP as a robust carbon mitigation strategy, even though China’s power grid is predominantly thermal-based. As China progresses toward its 2060 carbon neutrality target, ongoing grid decarbonization will further strengthen the advantages of GSHP systems.

China has implemented a carbon allowance trading mechanism to achieve emissions reduction targets. Projects with annual emissions below their quotas can sell surplus allowances at market prices, while those exceeding quotas must purchase additional allowances, thereby incentivizing energy conservation measures. In the building sector, this mechanism can promote the adoption of renewable energy technologies such as GSHP systems.

During the production phase, the primary sources of carbon emissions include equipment manufacturing and the extraction and processing of raw materials. The production of GSHP systems requires significant material processing, such as steel, copper, aluminum, and high-density polyethylene (HDPE), all of which produce notable carbon emissions. The HDPE pipes used for underground installation and the copper and steel components within the heat pump units demand substantial energy during extraction and processing, contributing to emissions. In contrast, while traditional systems have a simpler material composition, they still contain high levels of aluminum and carbon-intensive ABS plastic. Therefore, carbon emissions during the production phase for GSHP systems are somewhat higher due to their greater equipment complexity.

The transportation and construction phases account for a smaller portion of total life cycle carbon emissions for both systems, as these emissions are limited to short-term activities. In comparison, the production and operation phases involve prolonged energy consumption and higher emissions.

The operation phase is the dominant contributor to the total carbon emissions for both systems. For GSHP systems, these emissions arise from electricity usage for operating the heat pump unit, water pump, and fan coil units. The electricity grid in Shandong, where thermal power generation comprises 83.5% of the energy mix [

41], has a relatively high carbon emissions factor. If clean energy sources (e.g., wind or solar power) were used for electricity, emissions during this phase could be significantly reduced, approaching near-zero levels. As the grid increasingly incorporates renewable sources like wind and nuclear power, GSHP systems are expected to play a more prominent role in achieving building energy efficiency and carbon reduction goals. This will be discussed in the sensitivity analysis below. Advances in energy storage and smart grid technologies will further support efficient system operation.

Based on preliminary estimates, China’s annual exploitable shallow geothermal energy resources amount to 356 Mtce. After accounting for energy consumption during extraction processes, the net energy saving potential reaches 248 Mtce per year, corresponding to an annual CO2 emissions reduction of 647 Mt.

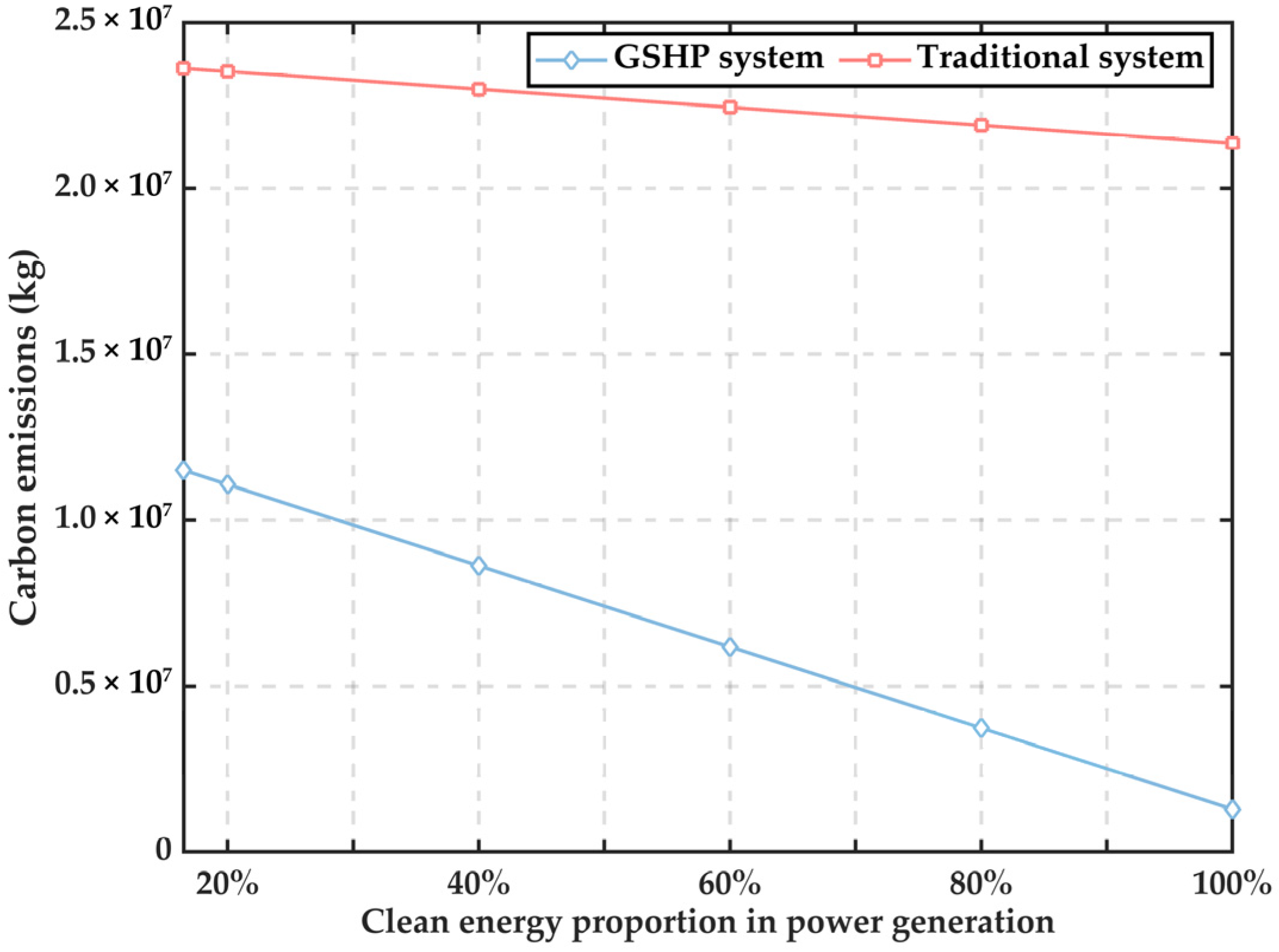

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis to Energy Structure

The energy structure of power generation is a critical factor influencing carbon emissions. In this study, the Northern China power grid is dominated by thermal power generation, resulting in a high carbon emissions factor. Increasing the proportion of clean energy in the generation mix can significantly reduce grid emission factors and alleviate environmental burdens. For instance, the Southwest China grid exhibits a carbon emissions factor approximately one-quarter that of Northern China, owing to its abundant hydropower resources.

Although Shandong Province lacks substantial hydropower potential, its extensive coastline offers significant offshore wind power capacity. Additionally, several coastal cities have operational or planned nuclear power plants. Based on changes in Shandong’s grid generation structure and national clean energy share targets, a sensitivity analysis was conducted on the variation in clean energy generation proportion (

Figure 4).

Figure 4 indicate that carbon emissions from both the GSHP system and the traditional system decrease linearly with increasing clean energy proportion, whereby GSHP systems demonstrate progressively steeper emission reduction curves compared to traditional systems This is primarily because the GSHP system consumes only electricity during the operation phase—which accounts for the largest share of carbon emissions—while the traditional system relies predominantly on coal combustion. Consequently, grid decarbonization yields greater emissions reduction benefits for the GSHP system. Quantitative analysis reveals that every 20% increase in clean energy proportion reduces carbon emissions by 39.4 kg/m

2 for the GSHP system and 8.7 kg/m

2 for the traditional system in a life cycle.

These findings underscore the importance of transitioning the power grid from thermal to clean energy generation.

5.3. Economic Analysis

The lifespan of both the GSHP system and the traditional system is set at 20 years, and a dynamic evaluation method is used for economic assessment. This section compares the economic benefits of the GSHP system with the traditional system, focusing on two key indicators: net present value (NPV) and dynamic payback period.

5.3.1. Net Present Value

NPV is a crucial indicator for assessing the economic value of a project, which is determined by discounting future cash flows to their present value using a specific rate and comparing them with the initial investment. The NPV calculation formula is as follows:

where

denotes the system’s service life in years,

represents annual revenue in CNY 10

4,

represents annual operating costs in CNY 10

4,

is the discount rate, and

is the initial investment in CNY 10

4.

5.3.2. Dynamic Payback Period

The dynamic payback period measures the time needed for accumulated project revenue to cover the initial investment, reflecting the time value of money [

42]:

where T

p represents the dynamic payback period in years. The payback is achieved when the NPV reaches zero.

5.3.3. Initial Investment

The initial investment for the GSHP system includes the purchase of equipment, transportation, installation, and drilling-related expenses. For the traditional system, it includes air conditioning units and the procurement of steel pipes and heat network construction, as detailed in

Table 11 and

Table 12 [

43]; although the GSHP system requires additional costs for drilling and grouting operations during the installation of ground heat exchangers, the equipment-intensive nature of the traditional system results in significantly higher upfront costs.

5.3.4. Operating Costs

The annual operating costs include energy consumption costs, equipment maintenance expenses, and staff management expenses. Both systems rely on electricity. Since local subsidy policies support renewable energy systems, the GSHP system qualifies for residential electricity rates. In Jinan, residential electricity pricing follows a tiered structure: for consumption up to 210 kWh, the rate is 0.5469 CNY/kWh; for usage between 210 and 400 kWh, the rate is 0.5969 CNY/kWh; and for consumption exceeding 400 kWh, the rate is 0.8469 CNY/kWh. Additionally, the average price of coal is 655 CNY/ton. Based on calculations, the estimated annual operating costs for the GSHP system and the traditional system amount to CNY 662,573.17 and CNY 5,122,755, respectively. The life cycle economic indicators of both systems are presented in

Table 13. It demonstrates that traditional systems use boilers with thermal efficiency below one for winter heating, requiring expensive coal procurement to meet heating loads, while inefficient split air conditioners in summer incur high electricity costs. In contrast, GSHP systems replace both with a single electrical system, and during winter, GSHP systems consume significantly less electricity to provide the same heat output, resulting in substantial operational cost differences.

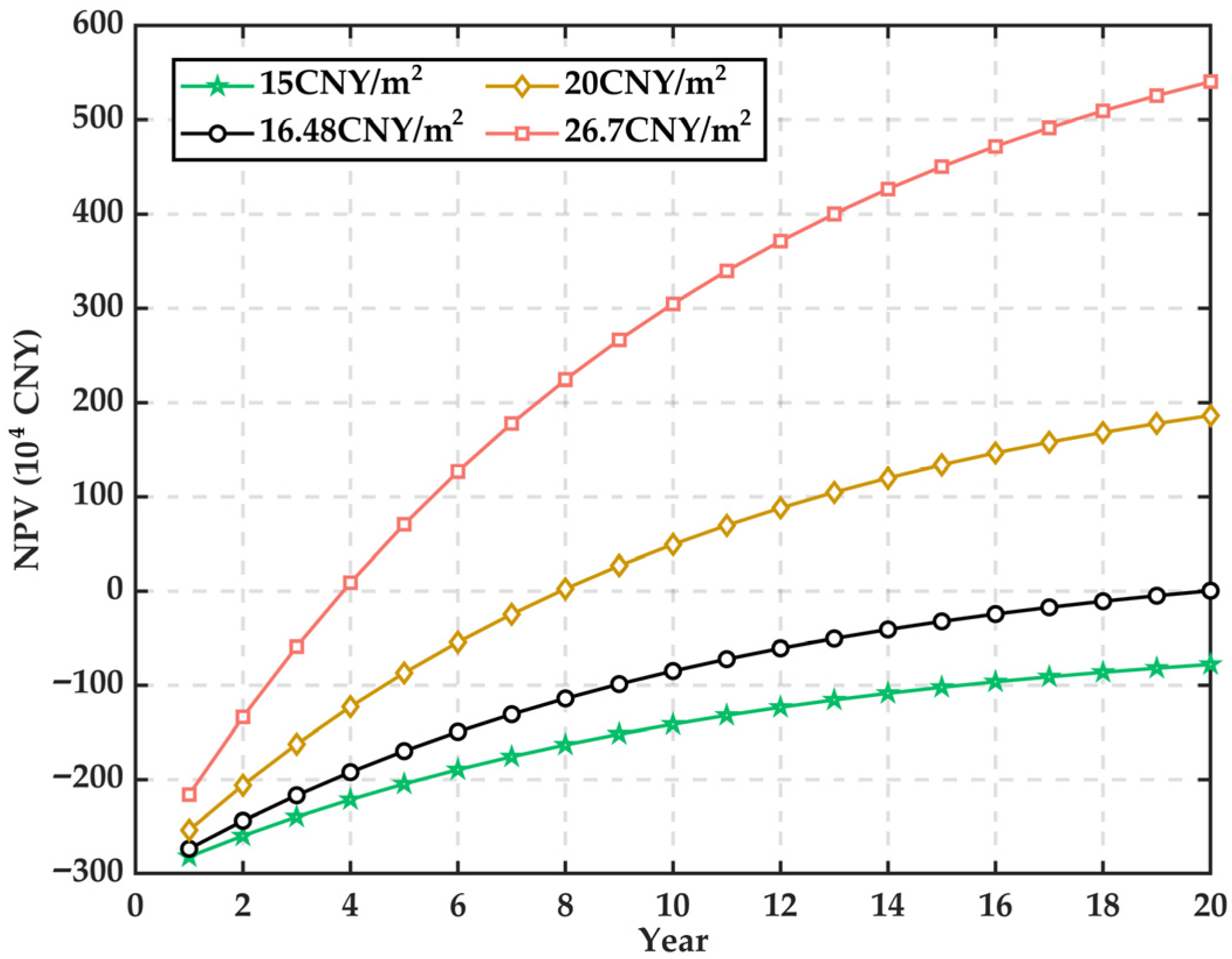

5.3.5. System Investment Recovery

The economic benefits of the project are key to evaluating system performance and serve as a prerequisite for assessing its feasibility. In addition to financial returns, environmental benefits must also be considered. As a renewable energy system, the GSHP system offers advantages primarily through fossil fuel savings and reduced environmental impact. From the perspective of society as a whole, the traditional system generates revenue by collecting centralized heating fees from residents and electricity fees for air conditioning use, with coal costs as expenditures. The GSHP system generates revenue through energy performance contracting by collecting heating and cooling fees, with electricity costs as expenditures. Given that the centralized heating price for Jinan residents is 26.7 CNY/m2, assuming the energy performance contracting model ranges from a lower limit of 15 CNY/m2 to an upper limit of 26.7 CNY/m2, an analysis of the NPV and payback period for both systems is conducted.

Research indicates that the financial discount rate for construction projects in China ranges from 10% to 12%, with lower rates in developed regions and higher rates in underdeveloped regions. As Shandong Province is classified as a developed region, we adopt a 10% discount rate and a 20-year life cycle to calculate the dynamic investment payback period [

42,

44]. Based on the calculations,

Figure 5 demonstrates that when the fee charged is above 16.48 CNY/m

2, the GSHP system yields yearly receipts of CNY 10,23,000, and can recover its costs and begin to generate profit within 20 years. When it reaches the centralized heating fee standard for residents, the cost can be recovered in 4 years, and a profit of CNY 5,404,900 can be achieved after 20 years. Due to the traditional system’s annual revenue being less than its operating costs, even when coal prices decline by 50%, its net present value still is negative, remaining in a loss-making state throughout its life cycle.

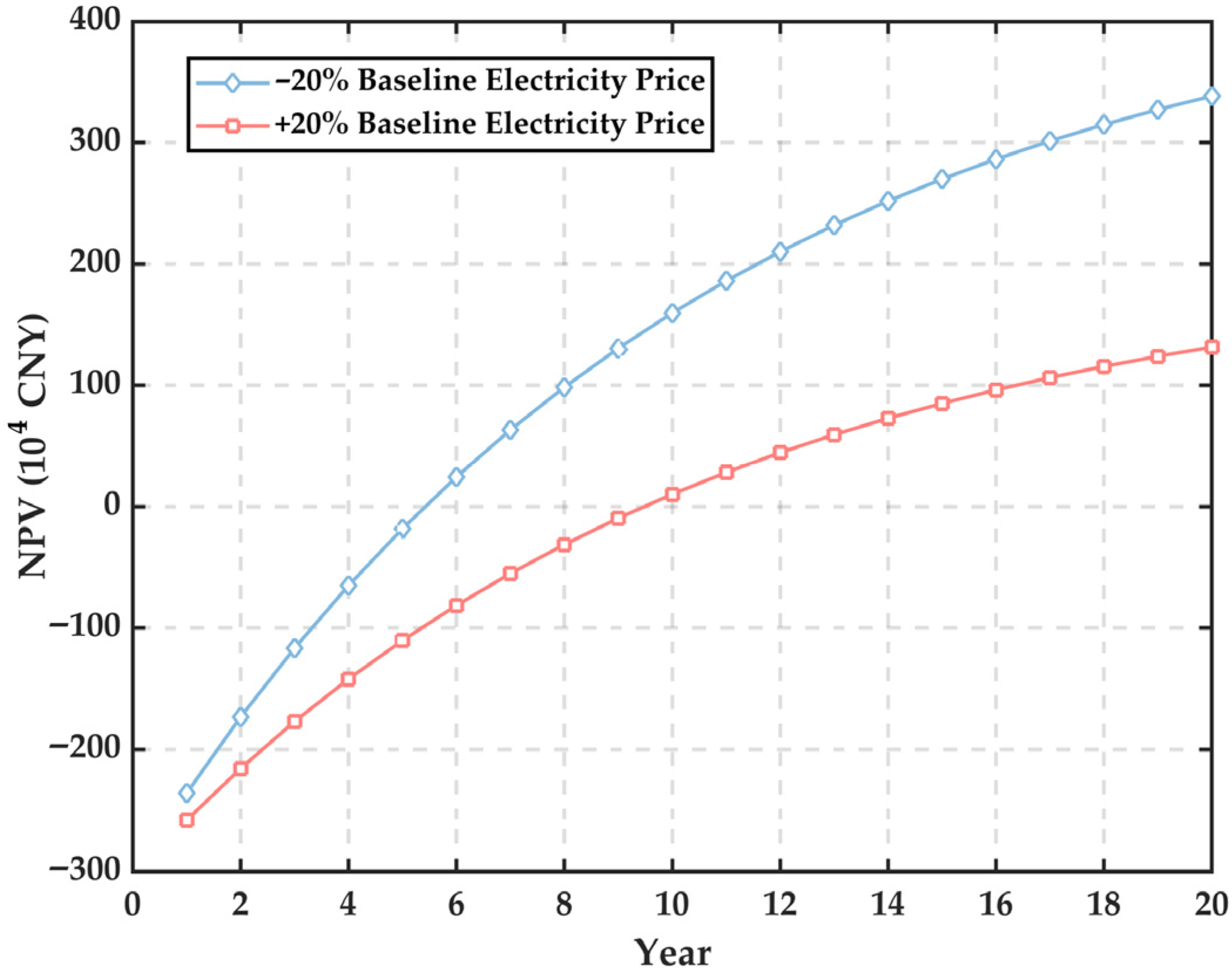

In energy performance contracting, service fee pricing is crucial for balancing user incentives and investor returns. Currently, the residential centralized heating price in Jinan is 26.7 CNY/m2. To make GSHP systems competitive, service fees typically need to be set below this benchmark to attract users. Therefore, this study assumes a service fee of 20 CNY/m2. This price point represents a win–win scenario: it offers residents approximately 25% cost savings compared to the municipal standard, while remaining above the system’s break-even point to ensure project profitability. Over the system’s life cycle, the cumulative NPV is projected to be approximately CNY 1,864,100.

The beneficial environmental impact of increasing clean energy share in the power generation structure is undeniable, but reducing carbon emissions does not necessarily equate to economic savings; therefore, electricity prices may fluctuate within a certain range. When the heating and cooling service price is 20 CNY/m

2, if electricity prices increase or decrease by 20%, the net present value of the GSHP system will change as shown in

Figure 6. When electricity prices decrease by 20%, the system will start generating profit 4 years earlier compared to when electricity prices increase by 20%. At the end of the 20-year period, the former will have earned CNY 2,068,800 more in profit than the latter.

6. Conclusions

This study quantifies the carbon emissions and economic performance of using a GSHP system compared to a traditional HVAC system for a residential building in Jinan via LCA and NPV payback period analysis methods. The LCA results demonstrate that the GSHP system outperforms the traditional system in both carbon emissions and economics.

To achieve current carbon peak and carbon neutrality targets, GSHP technology, as an efficient, energy-saving and environmentally friendly heating and cooling solution, has significant potential for widespread application in buildings. Life cycle carbon emissions analysis indicates that the carbon emissions of the GSHP system are only 48.7% of those of the traditional system, demonstrating excellent carbon reduction performance. Further reductions can be achieved by integrating renewable energy sources and optimizing the original energy generation process.

Shandong Province has excellent wind power generation conditions and nuclear power plants under construction or completed. This has established a new power generation structure in Shandong that is gradually shifting toward clean energy. China’s carbon allowance mechanism for achieving carbon neutrality encourages industries to adopt GSHP systems for HVAC applications. The stable geothermal source guarantees efficient operation, and ongoing grid decarbonization amplifies emissions reduction benefits. Through sensitivity analysis of the clean energy generation proportion, the carbon emission reduction in the ground source heat pump system can reach up to 88%.

Economically, under the condition of charging 20 CNY/m2 the GSHP system of the studied project yields an annual receipt of CNY 1,241,400, has a dynamic cost recovery period of 8 years, and achieves a cumulative NPV of CNY 1,884,100 over its life cycle.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the results are based on a single case study in Jinan and may not be directly applicable to other regions without adjustments, and generalizability to other building types and climatic regions requires further validation. Second, geological suitability varies significantly across regions. Differences in soil thermal properties and groundwater aquifer conditions, as well as available land area, constrain GSHP installation, while drilling costs vary with geological conditions, impacting economic feasibility. Finally, maintaining long-term seasonal thermal balance requires continuous monitoring, as excessive heat extraction or rejection may cause thermal imbalance in the subsurface, leading to the gradual degradation of soil thermal performance over the system’s operational lifespan. Future research should explore geological suitability conditions in Northern China, GSHP hybrid systems for addressing thermal imbalance issues, and comparative studies of multiple building types.

Nevertheless, the overall findings are positive. Beyond economic and environmental benefits, the application of GSHP technology in buildings significantly reduces energy consumption and carbon emissions while enhancing indoor comfort and overall sustainability. Therefore, further research and promotion of GSHP technology are of great practical significance for achieving energy conservation and emissions reduction targets in building sector.