1. Introduction

The 20th century was marked by bringing about comprehensive transformations in architecture, driven by technological advancement, industrialization, and social change. As traditional architectural forms struggled to address the needs of rapidly modernizing societies, modernism emerged as a radical break from the past. Characterized by functionality, abstraction, and the rejection of ornament, modernism was not simply an aesthetic style but a reflection of broader cultural, ideological, and technological shifts. Yet, as modernist principles spread across the globe, they encountered resistance, reinterpretation, and adaptation.

As Mumford observed, the modern movement should not stand apart from its surroundings but grow out of them—he considered it fundamentally regional in nature [

1]. For Mumford, modern architecture was not incompatible with regional identity; rather, it offered an opportunity for synthesis—blending modern methods with the distinct environmental and cultural characteristics of place. In opposition to the standardizing tendencies of International Style architecture, post-1940s regionalism re-emerged as a design approach grounded in locality. In particular, architects often turned to Mediterranean vernacular traditions as a source of inspiration, using them to shape modern designs that felt grounded and responsive to local conditions.

In Cyprus, modern architecture reflected not only the influence of international modernism, but also the island’s specific socio-political circumstances and environmental conditions. The period between 1930 and 1974 was marked by the most turbulent political context among Cypriots, including colonisation, state-building, post-colonisation, intercommunal conflict, and political and territorial division at the end. To better understand how the concept of modernization was interpreted through regional and Mediterranean characteristics in Cypriot housing, this study explores the following research questions:

- (a)

How have socio-cultural and socio-political developments in Cyprus—including the colonial period, internal conflict, and the periods before and after World War II—influenced the emergence of modernism in Cyprus?

- (b)

How has Mediterraneanness been expressed in modern housing design, and how have spatial characteristics been shaped by it?

By engaging with these questions, the study aims to reveal how the ideals of modernism were adapted, challenged, or reinterpreted through the lens of Mediterranean regionalism in Cyprus. The selected case studies serve not only as architectural examples but as cultural and spatial texts that reflect the island’s complex negotiation with identity and modernity.

The analysis focuses on examples of modern housing built primarily by upper-middle- and upper-income families. Rather than representing the general housing stock of the period, these residences reflect the spatial preferences of the more affluent segment embracing modern living. Therefore, the study examines not the spread of modernism across the island, but rather how a select group embraced the modernist lifestyle.

The present research is not merely a summary of existing literature; it is an original study in which a total of 14 modern housing projects from the 1930–1974 period are selected, tabulated, and comparatively analyzed across four historical periods according to systematic criteria. This approach provides new assessments of the spatial, climatic, and regional characteristics of modern housing production in Cyprus.

The article is structured around four historical periods: 1930–1940, 1940–1950, 1950–1963, and 1963–1974. These periods are not only a chronological sequence but also based on structural turning points in which modern housing production in Cyprus diverged in terms of architectural generations, political ruptures, and planning dynamics.

2. Modernism in 20th Century Architecture: Concepts, Evolution and Diffusion

2.1. Defining the Terms: Modernity, Modernism, and Modern Architecture

To understand how architecture developed during the 20th century, it’s useful to separate three related terms: modernity, modernism, and modern architecture. Modernity refers to the far-reaching historical shifts that followed the Enlightenment shaped by industrialization, urban growth, and social change—which ultimately disrupted long-standing traditions [

2]. In response, modernism emerged as a broad cultural and intellectual movement, touching disciplines like art, literature, and design. It aimed to reflect and make sense of a world in flux [

3]. Within architecture, modernism was more than just a change in style—it was a conscious move away from revivalist aesthetics, emphasizing function, simplicity, and formal structure.

These ideas took physical shape in modern architecture, which adopted industrial materials, new building methods, and minimal, efficient forms tailored to contemporary life [

4]. Still, the development of modernism was far from uniform. Its expression varied greatly, depending on the specific cultural, political, and environmental conditions in which it emerged.

2.2. The Modern Movement and European Ideals

One of the most conceptually driven strands of modernist architecture was the Modern Movement, which emerged in Europe in the early 20th century. It arose as a response to the social and industrial upheavals of the time, with the goal of designing environments that were rational, functional, and equitable. Leading figures such as Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe promoted a design philosophy grounded in utility, material honesty, and formal simplicity. Their work reflected a strong humanistic vision and was closely aligned with the socialist ideals and avant-garde movements that shaped interwar Europe [

5].

2.3. From European Reform to Western Formalism

In the U.S., architectural modernism took on a more standardized and business-oriented tone. The earlier focus on social reform gave way to sleek design, technological precision, and expressions of corporate identity.

2.4. The International Style and Global Standardization

A defining moment in this transition occurred in 1932, when Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson introduced the International Style through an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This style distilled modernist architecture into a visually coherent vocabulary: flat surfaces, open plans, rectilinear forms, and the elimination of ornamentation [

6]. Unlike its European predecessor, the International Style emphasized aesthetic universality and was easily adapted to capitalist and institutional settings in post-WWII America [

7]. It soon became the dominant architectural language in North America, Latin America, and parts of Asia from the 1930s through the 1960s [

5].

2.5. Late Modernism and the Shift Toward Context

Following World War II, modernist architecture entered a phase known as late modernism. Though it continued the principles of functionalism and material honesty, it increasingly faced criticism for producing rigid, impersonal, and alienating environments [

5]. As modernism matured, its claims to universality were challenged by architects and critics who sought more contextually responsive approaches. As criticism of modernism’s universal approach gained momentum, it opened the door for the emergence of regional modernism—an architectural direction that aimed to bridge modernist ideals with the unique characteristics of specific places. Instead of following one-size-fits-all design models, regional modernism emphasized the use of local materials, climate responsiveness, cultural traditions, and social habits. Architects like Alvar Aalto in Finland, Tadao Ando in Japan, and Sedad Hakkı Eldem in Turkey showed how modernist ideas could be reinterpreted through local spatial traditions and environmental sensitivity [

8]. As modernism spread across diverse regions, its universal assumptions were increasingly challenged, especially in places where architectural identity was deeply tied to tradition and environmental conditions. This gave rise to regionalism, not as a rejection of modernism, but as a creative reworking grounded in place and culture. The next section looks more closely at how this regionalist turn took shape in the Mediterranean, both building on and questioning modernist ideals.

3. Contextualising Modernism: Regionalism, Mediterraneanism and Critical Adaptation

3.1. The Emergence of Regionalism in Architecture

Regionalism refers to the ideas, values, and aspirations that influence how a place is created, maintained, or reshaped over time. It captures the cultural, environmental, and social qualities that give a region its distinctive character. Regionalization, meanwhile, refers to the formation and consolidation of regions as a process, focusing on how regions take shape over time [

9]. Regionalism in architecture refers to the response to local geographic, climatic, and cultural conditions in design. It often arises in contrast to the universalizing tendencies of globalized or colonial architecture. Canizaro [

10] defines regionalism as an architectural approach shaped by the tensions between local traditions and the modernizing forces of industrial society. In economically constrained regions, local resources and vernacular practices often shape building strategies.

Critical regionalism, a concept with intellectual roots in the writings of Lewis Mumford, became prominent in architectural discourse during the late 20th century. Tracing the early roots of regionalist thinking, Lewis Mumford [

11] traced the origins of regionalism to 1854 and emphasized the need to approach it from multiple perspectives in order to fully grasp its cultural and architectural significance. Mumford notably argued that ‘the modern movement is essentially regional’, suggesting that modern design should be rooted in local traditions rather than divorced from them [

1]. For Mumford, modern architecture was not incompatible with regional identity; rather, it offered an opportunity for synthesis—blending modern methods with the distinct environmental and cultural characteristics of place. In architecture, regionalism became a means to mediate between the globalizing thrust of modernism and the desire for local continuity and cultural relevance.

In this context, there is an important semantic distinction between the concept of “regionalism” explored by Mumford and the “critical regionalism” developed by Frampton. Mumford’s regionalism offers a broader, historical framework for the preservation of local materials, climatic conditions, craft traditions, and cultural continuity within modern architecture. In contrast, Frampton’s “critical regionalism” constitutes a point of resistance against the universalist and abstractive tendencies of modernism, transforming contextual sensitivity into a conscious design strategy. According to Frampton, this approach involves not only the reuse of local elements but also the critical reinterpretation of modern architecture. This distinction further clarifies the place of the concept of “Mediterranean regionalism” used in this study within discussions of both historical and critical regionalism.

The concepts of “regionalism,” “critical regionalism,” and “Mediterranean identity,” used in this study, are interrelated but correspond to different theoretical horizons. Regionalism emphasizes the continuity established by architecture with local climate, materials, craft traditions, and cultural practices, while critical regionalism represents a selective and critical position that develops contextual sensitivity against the universalist approach of modernism. Mediterranean identity, on the other hand, is defined by environmental and cultural practices shared at the basin level, such as spatial permeability, a semi-open culture, shading and ventilation strategies, and the integration of everyday life with the outdoors. Clarifying the distinction between these three concepts allows for a clearer understanding of the concept of “Mediterranean regionalism” used in this study, both through historical-modernist debates and the unique spatial character of the Cypriot context.

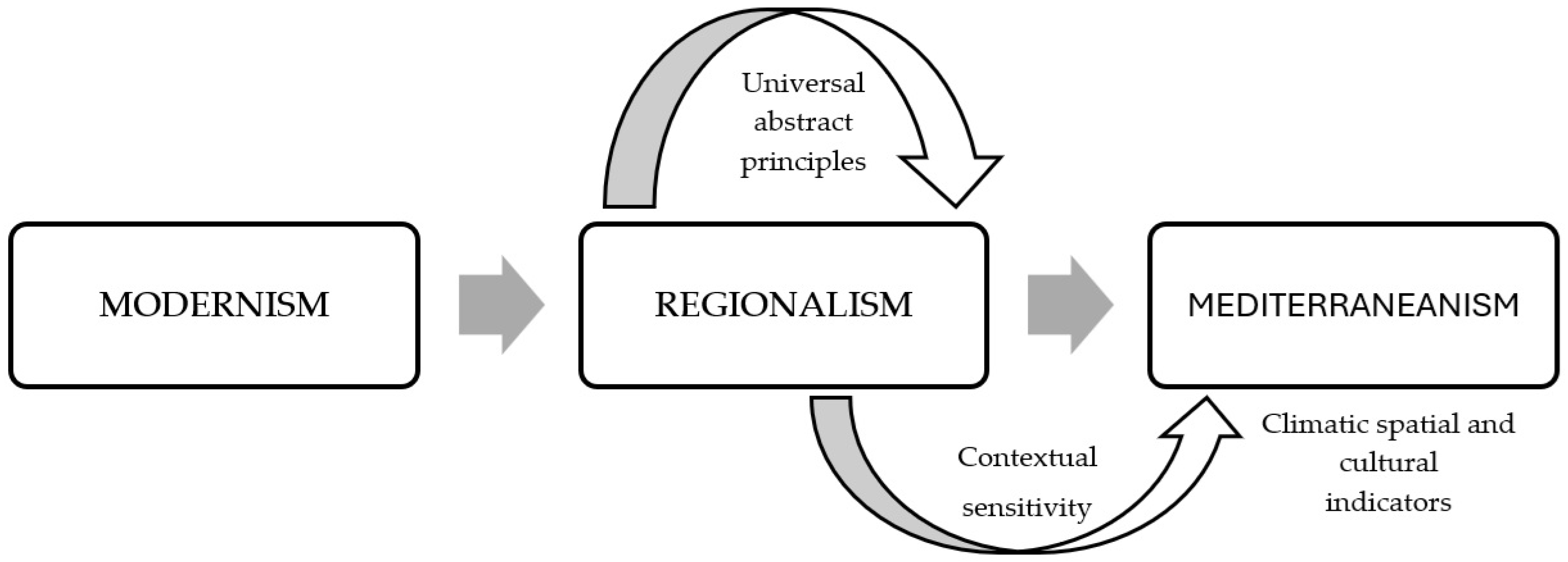

To visually support this theoretical discussion, a conceptual framework has been prepared that illustrates the historical and conceptual relationships established between modernism’s universalist principles and regionalism and Mediterraneanism. The diagram summarizes the theoretical connections extending from modernism’s ‘universal-abstract’ design approach to regionalism’s contextual sensitivity and, from there, to the climatic, spatial, and cultural indicators of Mediterranean identity. This visual framework more clearly reveals the theoretical positioning of the concepts used in the article and facilitates the reader’s tracing of trends in the literature within the context of periodicity and conceptual continuity (

Figure 1).

3.2. Mediterranean Regionalism: Local Adaptations of Modernist Ideals

In the 1930s, the Catalan group G.A.T.C.P.A.C. promoted modern architecture in Spain through a regionalist lens, blending minimalist modernism with vernacular traditions of northeastern Spain. Le Corbusier’s support further legitimized these efforts. Mediterranean architecture emphasized local materials, whitewashed surfaces, and forms suited to climate and lifestyle. Fernand Braudel famously described Mediterranean identity as shaped by a shared climate and cultural continuity across regional borders [

12].

Architect José Antonio Coderch continued this trajectory in the 1950s, integrating national and regional elements into modernist design. His works—including the Esteve House, Catasús House, and Rozes House—harmonized traditional Mediterranean forms with modern spatial concepts [

12]. Similarly, André Lurçat’s Hotel Nord-Sud (1931) and Le Corbusier’s Villa Le Mandrot used local materials and construction techniques to adapt modernism to specific Mediterranean contexts [

13,

14]. These projects did not merely apply modernist forms but reinterpreted them through the lens of climate, landscape, and community life. This approach linked architecture to broader socio-political changes, especially in regions like Cyprus, where post-colonial identity was expressed architecturally.

3.3. Theoretical Foundations of Regionalism and Critical Practice

While Mediterranean regionalism offers physical and aesthetic adaptations of modernism, critical regionalism encompasses a broader philosophical stance. It recognizes the expressive power of local traditions while resisting nostalgic revivalism. According to Frampton and Rogers, critical regionalism aims to reassert humanistic values by anchoring buildings in topographical and cultural specificity [

15,

16]. Concrete regionalism replicates specific regional features, while abstract regionalism integrates regional influence through symbolic or conceptual gestures [

17]. Both approaches resist architectural homogenization and promote spatial and cultural diversity.

As Meganck et al. [

18] note, the 1930s marked a shift in regionalist thinking. Economic and political instability led to a ‘closed’ form of regionalism, where communities turned inward. Nonetheless, the ideals of regionalism continued to inform architectural strategies that respected context while engaging in contemporary expression.

3.4. Regionalism as a Global Critique and Continuation

Regionalism ultimately emerged as both a critique of and a complement to modernism. It provided a framework to reinterpret modern architecture across different geographies without losing modernism’s core values of clarity, structural honesty, and functional expression [

17]. In diverse climates and cultures, this meant translating, selecting, and reinventing architectural principles rather than replicating them. As Lu [

19] emphasizes, non-Western architects did not merely imitate ‘high modernism’ from the West but actively adapted it to their cultural contexts. This process reflected the strength of modernism’s core logic while challenging its claim to universality. For theorists such as Jencks [

20], the issue was not modernism itself, but its abstraction and detachment from local meaning. Regionalism sought to restore that connection.

In doing so, regionalism reaffirmed architecture’s potential to embody both modern progress and cultural specificity. It transformed modernism from a singular vision into a pluralistic, context-sensitive, and critically engaged global discourse.

The theoretical and architectural evolution of regionalism—particularly in the Mediterranean—set the stage for diverse local interpretations of modernism across national and postcolonial contexts. Among these, Cyprus presents a unique case where the convergence of modernist ideals, regionalist adaptation, and Mediterranean sensibilities shaped a distinctive architectural identity. The following section examines how these intersecting frameworks influenced the development of modern housing in Cyprus, with a focus on how regionalism and Mediterraneanism informed spatial organization, material choices, and cultural expression

4. Modern Housing, Regionalism, and Mediterraneanism Context in Cyprus

4.1. Colonial Roots and the Beginnings of Modern Architecture in Cyprus

Since the Enlightenment, Mediterranean architecture has adapted to modern principles while preserving its local identity. It often deliberately reshaped itself to redefine dominant styles and discourses [

21]. Cyprus came under British control in 1878, leased from the Ottoman Empire due to its strategic location and potential economic and military value [

22]. Initially, architects showed little interest in stylistic grandeur; however, after Cyprus gained colonial status in 1925, the British administration supported urban development with new laws that promoted modernization. By the 1930s, modern architecture began to spread across the island as more architects trained abroad returned, and foreign architects—such as Jewish engineers Benjamin Gunzburg and Samuel Barkai from Tel Aviv, and Polys Michaelides from Athens—began practicing in Cyprus [

23]. Reinforced concrete began to be used for architectural elements like balcony slabs by 1914, gradually replacing traditional materials [

23]. George Theocharous noted that colonial architecture significantly impacted the built environment and attitudes of Cypriots, with early private buildings demonstrating a simple, environmentally sensitive approach [

24].

4.2. Public Architecture and the Nation-Building Project

In the 1950s, public buildings, particularly public housing units, became a major focus of state-led construction efforts. Though many of these projects were completed in stages, the rising population and modernization demands led to the rapid development of government housing and apartment complexes. These developments created new housing zones on the city peripheries, which eventually integrated into the island’s urban fabric.

Built in 1955, the House of Representatives in Nicosia later took on symbolic meaning as the site where the Republic of Cyprus was declared in 1960. Although it was completed before independence, the building came to embody the island’s move away from its colonial and nationalist past. The use of white plastered walls, instead of traditional yellow stone, signaled a thoughtful turn toward modern ideals and a visual alignment with Western design sensibilities. This shift from colonial to modernist architecture went beyond aesthetics—it echoed a broader ambition to foster civic engagement, attaching a hopeful society to the new nation [

25].

While institutional architecture often conveyed national ambitions and political ideals, domestic architecture reveals how modernization influenced daily routines, family structures, and social expectations. In these more personal settings, adaptation to local climate, materials, and cultural practices occurred with greater flexibility.

4.3. Mediterraneanism and Cultural Hybridity

Following the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960, modernism began to carry new symbolic weight. It offered architects a means to articulate regional character while also engaging with global architectural discourse. The design language of the era was rational and forward-looking, aligning with national aspirations yet responsive to the island’s layered cultural context. As Fereos and Phokaides [

26] note, many architects of this time blended the formal clarity of modernism with local materials and familiar forms. Similarly, Phokaides and Pyla [

27] emphasize that Cypriot architectural aesthetics were not developed in isolation but were part of broader international conversations. At the same time, the idea of cosmopolitanism underwent a transformation. Apart from ethnic minorities, together with the development of tourism, Cyprus became a hub of a multicultural society. As Ben-Yehoyada [

28] observes, cosmopolitanism was reabsorbed into a narrative of progress—shaping a design ethos that looked ahead while still acknowledging inherited cultural foundations.

4.4. Social Aspirations and the Rise of Modern Housing Architecture

In the aftermath of World War II, shifts in Cyprus’s housing patterns echoed broader improvements in income and quality of life [

29]. As economic conditions improved, a growing number of professionals—such as civil servants, doctors, and bureaucrats—began to pursue detached homes that signaled both social standing and a modern lifestyle. This rising demand spurred suburban expansion, particularly in areas like Nicosia’s Köşklüçiftlik neighborhood, where societal desires of modernity steered the architects to reworked modernist principles.

A key driver of architectural change during this period was the return of Cypriot architects educated abroad. They brought with them the principles of European modernism, which they adapted to fit the island’s specific cultural and environmental conditions. The detached houses that took shapesuch as those illustrated in

Figure 2 came to define the residential landscape of the time. Today, these buildings offer important insights into how Mediterranean and regional features were woven into the evolving language of modern architecture during this pivotal moment of transition.

During this period, residential architecture became not only a spatial production area but also a cultural tool reflecting the social positioning of the rising middle classes, their desire for modernization, and the transformation in public and private life practices. The more pronounced functional differentiation observed in the interior organization of residences, the positioning of the living room as a representative space, the influence of hospitality culture on the space, and the use of semi-open spaces as a means of socialization demonstrate how the social expectations of the period were reflected in architecture. Furthermore, the modernizing trends observed in material choices, furniture arrangements, and façade compositions became symbolic indicators that declared the residents’ social status. In this context, the residences of the 1950–1963 period can be considered architectural representations not only of modern lifestyles but also of the new social class dynamics emerging within Cypriot society.

4.5. Spatial and Lifestyle Transformations in Cypriot Housing

As the social and architectural shifts spread out, modern homes in Cyprus began to depart from traditional forms by embracing modernist values such as functionality, simplicity, and clearly defined spatial organization. Drawing on Western influences, these houses introduced distinct rooms, bedrooms, living areas, kitchens, and bathrooms—marking a new way of structuring domestic life [

30]. This architectural evolution also reflected bigger social changes. Families became increasingly nuclear, privacy became more central, and the spatial layout of homes began to support new roles within the household. For women in particular, these changes enabled greater engagement in both domestic and public spheres [

31].

In the 1950s and 1960s, housing design in Cyprus continued to reflect evolving social norms. Traditional courtyard houses were gradually replaced by more linear or compact layouts that emphasized order and separation through hallways and purpose-built rooms [

32]. Yet elements of tradition were not entirely lost. Architect Ahmet Behaeddin, for instance, reinterpreted the courtyard in his modern house designs, merging inherited spatial values with contemporary needs. Kitchens, once semi-open and externally located, were also relocated indoors and enclosed—reflecting new standards of hygiene and domestic organization [

33].

Interior life also changed noticeably. Features like large windows, open floor plans, modern furnishings, and standardized utilities began to replace older interior arrangements [

34,

35]. These updates were about more than comfort; they reflected broader changes in how space was lived in and what it meant. Modern architecture in Cyprus reshaped not just how buildings looked, but how people interacted, moved, and lived inside them.

While broader discussions of modern architecture on the island exist, few studies systematically examine how regionalism and Mediterraneanism shaped everyday housing. Most existing works tend to focus on individual architects or isolated case studies. Therefore, a broader comparative approach is needed to better understand how modernist principles were locally adapted across decades.

4.6. Related Work

Studies on modern housing in Cyprus prominently feature the works and designs of Ahmet Vural Behaeddin (1927–1993), the first Cypriot Turkish architect. According to Celik and Erturk [

36], few studies focus on local architects who deserve global recognition for their unique designs. Therefore, their research aims to systematically decipher the ‘Form Language’ of Ahmet Vural Behaeddin’s modern structures. The analysis focuses on a single residence designed by Behaeddin. Muhy Al-Din [

37], aims to understand modern architectural norms in twentieth-century Nicosia. His article analyzes residential buildings by Ahmet Vural Behaeddin, a renowned modernist architect of twentieth-century Northern Cyprus. Residential buildings in Milan, Rome, and Spain were also analyzed. The article highlights local elements in Nicosia’s modern architecture, focusing on facade materials and the Mediterranean modernist movement’s impact, as illustrated by two of Behaeddin’s buildings.

According to Amen [

38], modern architecture, founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius through the Bauhaus school, introduced entirely new principles and ideas to architectural theory. These principles included simplicity, angularity, abstraction, consistency, unity, organization, economy, delicacy, continuity, regularity, and sharpness. They influenced global architecture and were applied in various contexts. As an island near the movement’s origins, Cyprus was influenced by modern trends. The study analyzes Behaeddin’s residence to reveal Bauhaus’s influence in Cyprus. It compares Behaeddin’s designs with traditional houses, showing how Modernism transformed housing in Cyprus.

Charoula & Papasavvas [

39] note a trend of internationalization that homogenizes and marginalizes the concept of ‘place’ in architecture. The initial ‘intuitive’ observation indicates that contemporary architecture in Cypriot cities tends to imitate foreign architectural standards significantly, setting aside local expressions. The article emphasizes the distinct local features and lifestyle with which past buildings, including those that predominantly ‘served’ the principles of modernism in the 1950s and 1970s, had a Cypriot ‘touch.’ The article discusses 4–5 modern houses by various architects, highlighting local characteristics.

Tziirki [

40], highlights how architectural modernism in Cyprus created an ‘authentic’ local context, reacting to Western universality. The thesis discusses controversial modernist concepts like ‘decoration’ and ‘tradition’. It proposes modernism, emphasizing wall-mounted reliefs, developed through collaboration between Cypriot architects and artists. The thesis explores the categorization of art as ‘high’ or ‘low’ through the association and parallel degradation of decorative arts with femininity in the first half of the twentieth century. It focuses on 4–5 modern housing designs.

Yavuz [

41] dedicated part of his study on Abdullah Onar to residential designs, focusing on one residence to illustrate Cyprus’s post-colonial architectural context. The article broadly presents modern architecture and its subject matter. It highlights how post-World War II modernism aligns with Cyprus’s post-colonial period. Destebanoğlu’s [

42] Master’s Thesis in architectural theory explores modernism in North Cyprus during the British era from Abdullah Onar’s perspective. The study focuses on two specific examples.

While these studies offer valuable insights, few address regionalism or Mediterraneanism in a broader framework. This study responds to that gap by analyzing a wider sample of modern houses—three to four per decade from 1930 to 1974—to trace how regional elements evolved over time. The following section presents the methodology and criteria guiding this comparative analysis.

5. Materials and Methods

A literature review was conducted to identify the most appropriate methodology for this study by examining approaches used in similar research. In his doctoral thesis, A Multilayered Analysis Based on Fractal Dimension: Eldem and Doshi Architecture, Lionar [

43] selected five houses based on regional influences evident in the architects’ works and writings. These examples, shaped by traditional architecture, were analyzed through visual complexity and continuity using fractal dimension analysis. This part of the methodology focused on clarifying how architectural designs related to regional influences through a comparative lens. To go deeper, the study also looked at functionality, construction techniques, and the broader socio-political and cultural contexts that shaped the architects’ thinking and design choices.

A related doctoral study by Agarez [

44], titled Regionalism, Modernism, and Vernacular Tradition in the Architecture of Algarve, Portugal, 1925–1965, followed a dual qualitative approach: fieldwork and archival research. Agarez began by identifying buildings that visually reflected regional qualities. Throughout the project, 450 buildings and architectural ensembles were identified and recorded in Algarve, supported by fieldwork. Additionally, 750 files from the archives of architects, municipal planning offices, and regional government bodies were documented through reading. Interviews were conducted with three prominent architects working in Algarve, property owners, and individuals involved in key projects for the region in Lisbon.

The 14 houses analyzed in this study were selected through a multistage selection process based on specific criteria. First, a large pool of modern residences dating from the 1930–1974 period was established. Subsequently, to select three to five examples representing each decade, the buildings were evaluated for their architectural originality, their level of reflection of modernist principles, their Mediterranean and regionalist characteristics, their use of materials, and their documentability. In line with these criteria, care was taken to ensure a balanced representation of designs by both local and foreign architects. The comparative analysis method employed in the study relies on the systematic evaluation of the selected residences based on parameters such as façade elements, climatic approaches, spatial configurations, and material/structural properties. The tabulation process was used as a tool to organize the data and identify common regional elements, contributing to a clearer visualization of the analysis results (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). This methodological approach facilitated both the comparison of findings across historical periods and the interpretation of the evolution of Mediterranean-regionalist characteristics.

All photographs used in this study were taken as part of fieldwork conducted by the author in 2023. City information for the photographs is provided in all figure and table captions. Because the exact coordinates of the structures examined are not reliably available, coordinate information is not provided; however, the images were produced for original documentation purposes and all belong to the author’s own archive.

With the light shed by the related methodologies, for the Cypriot context, the research began with a detailed literature review, focusing on themes of Mediterraneanism and regionalism in Cypriot architecture. Key sources—including journals, academic articles, and graduate theses—were carefully reviewed to trace the development of modern architecture on the island. Alongside, on-site visits, observations, and document-based analysis supported the inquiry. Together, these methods form the basis for examining how modern structures and settlements reflect Mediterranean regionalism in Cyprus’s modern housing between 1930 and 1974.

Modernist architects, who engaged in modern housing design in Cyprus starting from the 1930s, were documented. Foreign architects, who came from abroad and initiated the first modern designs in the 1930s, were Joseph Claude Gaffiero, Benjamin Gunzburg, and Poly Michaelides. In the 1940s, Greek Cypriot architects Odysseas Tsangarides, Andreas Photiades, Neoptolemos Michaelides, Haris Feraios and Turkish Cypriots Abdullah Onar, Ahmet Vural Behaeddin, who had received education abroad and returned to the island, started to produce modern designs as well. Houses that showed a Mediterranean identity were documented. From this broader pool, a selection of houses was made through an elimination process based on specific time intervals. Each selected example was visited and photographed during fieldwork to ensure accurate documentation and to cross-reference with published or archival visual materials. The final analysis categorized the buildings under two main headings: (1) Regionalist and Mediterranean Characteristics, and (2) Architectural Features.

Although the creation of comparative tables was not the primary aim of the study, they proved instrumental in identifying recurring regionalist elements across the selected cases (

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). Findings were grouped under key thematic headings and further discussed in the results section. The analysis revealed consistent patterns among regionalist modernist designs, particularly in material usage, passive climate control strategies, sensitivity to local context, and façade articulation. These classifications support a deeper and more systematic understanding of Mediterranean regionalism as manifested in Cypriot modern housing.

5.1. Case Selection and Analytical Framework

The primary criterion for case selection was the architectural significance of the houses within the history of modernism in Cyprus. The fact that most of the selected examples belong to the educated, high-income, and professional classes of the period reflects the social stratification of modern housing production. Therefore, the study examines the architectural responses to modernism of more affluent segments, rather than the typologies of modern housing spread across all social segments. This is an inherent limitation of the sample selection, and the results should be evaluated within this framework. Key considerations included housing typology, building form, structural and construction techniques, technological applications, facade composition, and materials. This re-evaluation allowed for a nuanced assessment of how strongly each house expressed modernist architectural principles, both in general and in relation to regionalist and Mediterranean values.

To keep the analysis consistent with existing architectural historiography on Cyprus, the selected houses were arranged into four phases (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). The periodization follows architectural developments and historically significant turning points rather than stereotyped decade-based divisions. Academics and researchers working on Cyprus, including Fereos and Phokaides [

26], Phokaides and Pyla [

22], Gürdallı and Koldaş [

25]. Kiessel [

45], and Schaar [

24], show that shifts in domestic architecture correspond more closely to significant turning points such as wartime restrictions, post-war rebuilding, decolonization, and intercommunal conflict that changed material availability, construction technology, design approach, and the emergence of a locally active architectural profession. Hence, the four phases used took the political and historical circumstances as a frame but are shaped by the internal logic of the buildings themselves.

The first phase, 1930–1940 (Early Modern), marks the introduction of modern architectural ideas during a period of intensified British colonial administration after Cyprus became a British Crown Colony in 1925. The 1930s saw the earliest consistent use of reinforced concrete, planar masses, and simplified spatial layouts in Cypriot housing. As Phokaides [

27] notes, architectural modernism was introduced to Cyprus, the ideas and architectural practices, in the 1930s by foreign architects working under the British Public Works Department or through private commissions. Houses often continue colonial compositional habits, including symmetry and the use of yellow sandstone, while early reinforced-concrete construction appears in a tentative form. Along with the first modernist experiments of the 1930s, the emergence of Art Déco in Cyprus as a modernist variant was experienced between the 1930s–1940s. Kiessel [

45] characterizes it not as a strictly British import but as a form of ‘Mediterranean Art Déco’, combining streamlined modern features and rounded forms with influences drawn from France, England, and Athens that shaped the visual vocabulary of Cypriot domestic architecture in these years. This era also coincides with rising political tension. In 1931, Cypriot riots culminated in the burning of the British Governor’s residence, renewing the Presidential Palace seen by the British rulers a chance of showing respect toward Cyprus’s layered heritage. This was intentionally seen as a symbolic ‘olive branch’ offered to locals. The new Cypriot mélange that started with the design of government buildings was extended to all building typologies.

The second phase, 1940–1950 (Wartime Austerity & Transitional Modern), began with wartime shortages that produced a reduction in domestic construction. As building activity resumed only after the war, 1945 marks a new beginning, a gradual modernization in lifestyle. As post-war conditions stabilized, Greek Cypriot architects began establishing practices and contributing more consistently to domestic design. These architects, including Odysseas Tsangarides, Andreas Photiades, Neoptolemos Michaelides, and Haris Feraios, incorporated regionalist approaches into their designs. Their work can be seen as a response to the homogenizing effects of international modernism. Among the documented examples, houses such as the Osman Misirlizade House (1945) and the residence of Judge Zeka Bey (1948–1949) stand out. These demonstrate the blending of modernist design principles with regional characteristics—such as the use of yellow local stone—as material expressions of architectural synthesis. Fereos and Phokaides [

26] describe these years as a transitional phase: the architectural output remained modest compared to the consolidation that would follow in the 1950s.

The third phase, 1950–1963, corresponds to the political realignment of the late-colonial crisis as initial post-colonial thinking and the founding of the Republic of Cyprus between 1960–1963. From 1950 onward, domestic architecture in Cyprus displays a coherent and fully developed modernist vocabulary where architectural researchers identify these years as the clearest moment when international modernism became consolidated in Cypriot housing. Reinforced-concrete frames are clearly expressed, with white rendered façades, horizontal openings, sun-control elements, and clearer expression of structural frames became increasingly common. The decline in the use of yellow sandstone, highlighted by Gürdallı & Koldaş [

25] and Phokaides [

27], signals a conscious move away from ethnic or historicist references. Phokaides and Pyla [

22] identify this period as the consolidation of modernism at both professional and material levels. Greek Cypriot architects who matured professionally during the post-war years, and Turkish Cypriot architects returning from Europe and Türkiye, like Ahmet Vural Behaeddin, İzzet Ezel Reşat, Abdullah Onar, Ayer Kaşif, Ahmed Behzat Aziz-Beyli, and Hakkı Atun after the mid-1950s, as noted by Yavuz [

41], contributed to this phase. Despite differences in background, the designs of Turkish and Greek Cypriot architects form a unified architectural field. Although 1960 marks the end of British colonial rule and the beginning of the post-colonial Republic, the architectural vocabulary established in the 1950s continued without interruption; for this reason, this phase extends to 1963. Independence reinforced the shift started in this decade, producing a brief but distinctive period in which architectural ambition, climate-responsive design, and Mediterranean modernism aligned strongly.

The fourth phase is 1963–1974. The intercommunal conflicts of 1963 brought the republic period to a sharp end and while the Republic of Cyprus continued to function in the south of Cyprus, the northern part of the island lacked an official administrative structure after 1963. In this period, intercommunal conflict, population movements, and spatial segregation directly determined housing production. The production areas of Turkish and Greek architects were geographically separated, and the 1974 military intervention profoundly impacted architectural and socio-political structures. These conditions changed mobility, property use, and urban development, which in turn affected the design and construction processes of houses. Across both communities, displacement made the rapid and economical production of migrant housing a priority. After the intercommunal conflict of 1963, construction in the northern part of Cyprus was further constrained by embargoes that intensified after 1967 and remained in effect until 1974. These restrictions created material shortages and disrupted transport and communication networks [

46]. Interethnic tensions had already begun to affect architectural patronage before 1963: barbed-wire barriers marked the first signage of spatial separation in 1956, and the British ‘Mason–Dixon’ separation of 1958 established the early ‘Green Line’ [

47], which encouraged Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot elites to engage architects from within their own communities. Yet this shift did not produce stylistic divergence, since architects on both sides were educated in similar European institutions or in Turkish universities shaped by Bauhaus-derived pedagogies. Communal alignment in patronage that preceded 1963 did not change architectural language. Modernist ideas remained present but were implemented within increasingly uneven social and territorial circumstances.

5.2. Classification Criteria

By identifying and grouping the elements, specific architectural features shaped by the region’s climate, the study was able to highlight recurring regionalist patterns and design strategies. Beyond climatic features, socio-cultural, political, and identity factors were also considered. The classification began by defining the criteria and sub-qualities, guided by the works of Kütükçüoğlu [

12] and Arslan [

48], as listed below:

Spatial innovations are understood not only as physical arrangements but also as expressions of cultural belonging, everyday life, and political positioning. Rather than pursuing a universal modernist ideal, architecture thus becomes a means of reinforcing and preserving local identity. This topic will be further developed in the subheading The Socio-cultural and Political Context and examined in detail under The Home as a Medium of Cultural and Spatial Change.

This criterion addresses shifts in residential planning and spatial organization linked to changing lifestyles. Traditional Cypriot houses, shaped by privacy concerns, followed introverted layouts where daily life centered on enclosed courtyards, and verandas or balconies were largely absent. In modern housing, however, even when courtyards were retained, they were complemented by verandas, balconies, and semi-open spaces, reflecting a more extroverted spatial approach and greater engagement with outdoor living. The “new housing typology” thus refers to these spatial and functional transformations, which will be examined through case studies and further analyzed in the Spatial and Lifestyle Transformations in Cypriot Housing section.

This study also assessed the current state of preservation of the residences examined. It appears that a significant portion of the modern residences dating from the 1930–1974 period are not currently under official legal protection. However, some structures in Southern Cyprus—Kaniklides House, Demetrakis Alexandrou House, and Neoptolemos & Maria Michaelides House—have been included in DOCOMOMO Cyprus’s modern architectural heritage inventory and marked on the institution’s maps [

49]. While DOCOMOMO’s documentation highlights the architectural significance of these structures, inclusion on the list does not confer any legal protection status. Therefore, the study evaluated the structures by considering both their physical location within the marked map areas and their cultural value within the modern architectural heritage.

Table 1.

Modern houses (1930–1940) (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 2.

Modern houses (1940–1950) (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 3.

Modern houses (1950–1963) (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 4.

Modern houses (1963–1974) (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

5.3. Classification of Analyzed Elements

The effects of regionalism on the selected buildings have been analyzed through the following classifications, each reflecting key aspects of design adaptation:

Climate Context;

Facade Elements;

Material/Structure;

Sociocultural Context.

The identified Mediterranean elements were categorized and compiled into a comprehensive table covering all relevant aspects. The analysis of the selected houses is summarized in the accompanying table, which highlights the recurring use of Mediterranean elements across different time periods (

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). This study adapts and expands upon Lionar’s [

43] categorization of regionalism, originally developed for architectural comparisons. Drawing on fieldwork and photographic documentation, key Mediterranean features present on building façades were examined in detail. The findings indicate that, between 1950 and 1974, a number of modern houses emerged that integrated multiple Mediterranean elements, reflecting a clear influence of regionalist thinking in Cypriot housing architecture.

Table 5.

Mediterranean elements in modern houses of 1930–1940 (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 6.

Mediterranean elements in modern houses of 1940–1950 (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 7.

Mediterranean elements in modern houses of 1950–1963 (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

Table 8.

Mediterranean elements in modern houses of 1963–1974 (Source: Authors’ own work, 2023).

6. Results

This section systematically presents the data obtained within the scope of the study, explaining the key spatial, morphological, and climatic trends that emerged throughout the analysis. The findings are organized according to classification headings, with each category considered within its own internal consistency. The following discussion builds on the classifications presented earlier to interpret these patterns in detail.

6.1. Climate Context

Cyprus’s hot, dry summers and mild winters, typical of the Mediterranean climate, have shaped housing design through passive cooling solutions. Traditional houses addressed these needs with thick stone walls, small windows, courtyards, and shaded areas [

30]. Responding to the tradition of outdoor living, voids and transitions created shaded seating areas on ground floors (

Table 8).

A common feature of the studied houses is their climate-responsive design, which includes open and semi-open spaces, courtyards, and patios—key elements of Mediterranean living. In this climate, where outdoor life dominates much of the year, shaded intermediate spaces surround the settlements. Wide openings, cantilevers, and eaves help cool interiors by creating shadows (

Table 7). In specific examples, such as the top windows of the Theodotos Kanthos House (

Table 3) and the Desaini Aalotar-Ertoğrul Güven House (

Table 4), window designs extend across wide wall surfaces for climate control. Shutters, traditional in Mediterranean architecture, were reinterpreted through new materials and rolling mechanisms during this period. Additionally, wide balconies defining the house perimeters offer shade and promote natural ventilation.

Deep balconies and patios function as open-air rooms—an alternative form of Mediterranean intermediate space. As seen in

Table 4 (Neoptolemos and Maria Michaelides’ House; Desaini Aalotar-Ertoğrul Güven House) and

Table 3 (Theodotos Kanthos House), shaded transitional areas, inspired by traditional settlements, were designed at varying scales and linked to one another.

Shutters, pergolas, and blinds—typical of Mediterranean architecture—were resized to improve shading on climate-responsive facades (

Table 6 and

Table 7). These modern adaptations created semi-open shaded spaces in the analyzed houses.

6.2. Façade Elements

The facades of modern Cypriot houses reinterpret functional and aesthetic elements from traditional architecture. As shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8, wooden shutters were updated in aluminum or simplified wood, retaining their roles in climate control and privacy [

50]. Traditional materials, such as stone, appear alongside modern lines, illustrating the ‘mixing and reinventing’ approach [

51]. These facade strategies balance modern spatial needs while sustaining cultural identity and articulating regional Mediterranean character.

Most residential designs are two-storey, defined by clear, sharp lines and simplified forms. By the 1930s and 1940s, low-pitched roofs had been largely abandoned, and linear geometries began to shape architectural language. In the Mediterranean climate, eaves provided shade and reduced solar exposure, while shutters were preferred where eaves were absent. Detached plots replaced the traditional adjacent settlement pattern, introducing regulated spacing and multi-directional facades. This shift redefined window openings, entrances, and facade organization based on orientation, daylight, and climate (

Table 5 and

Table 6). Access was arranged through pathways, entrance halls, and covered terraces. Large glass surfaces stretched across facades, reducing solid wall areas and enhancing interior–exterior connection.

6.3. Material/Structure

While facade elements expressed the synthesis of modern and regional features, material and structural choices were equally central to this transformation. In the early period (1930s–1950s), traditional materials remained dominant. Local yellow stone, deeply rooted in the island’s vernacular and colonial-era architecture, was widely used in thick load-bearing masonry walls (

Table 5 and

Table 6). Its high thermal mass offered passive climate control, moderating indoor temperatures by absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night—essential in the Mediterranean climate. Over time, however, exposed stone surfaces gave way to plastered finishes. Walls were increasingly coated with gypsum, producing smooth white facades aligned with modernist aesthetics while still grounded in local construction traditions (

Table 6).

From the 1950s onward, reinforced concrete frames replaced stone as the primary structural system. This shift allowed for larger openings, flat roofs, and more flexible interior layouts. Architectural elements such as deep projections, open balconies, decorative concrete pergolas, and expansive glass surfaces began to characterize facades. To align these modern forms with regional traditions, architects incorporated stone cladding, wood detailing, and other local materials (

Table 7 and

Table 8). Wood retained practical and decorative importance in shading devices, ceiling treatments, and shutters.

6.4. Sociocultural and Local Context—Results Only

The table shows clear chronological patterns in housing typology, spatial arrangements, modernist language, and architectural authorship.

The table indicates that the 1930–1940 houses maintain earlier colonial detached typologies with compact forms and only limited spatial additions, such as small verandas or entry porches and shallow recesses. These elements, while modest, correspond to features commonly found in early Mediterranean domestic arrangements, including protected thresholds and transitional outdoor spaces. Modernist language is partially adopted, like flat roofs and façades coexisting with yellow sandstone surfaces, horizontally proportioned openings appear in limited form, and occasional Art Déco details can be observed. Several of these characteristics overlap with regional building practices around the Mediterranean, such as masonry-based façades and extensions (covered entries, small service extensions, etc.) projecting as additive elements. All examples in this period were designed by foreign architects.

In the 1940–1950 houses, the table presents modest typological adjustments, including slightly enlarged verandas, projecting balconies, and small semi-open additions. These features represent the early development of spatial elements that later become more typical of regional and Mediterranean domestic environments, such as balconies and shaded transition spaces. Spatial innovations become more frequent than in the previous decade, with early recessed elements and wider openings improving indoor–outdoor transition. The adoption of modernist language continues selectively as reinforced concrete appears more regularly, façades become simpler, openings develop horizontal emphasis, and ornamentation decreases without disappearing entirely. Such simplification aligns with wider mid-century trends across Mediterranean modernism without yet forming a complete stylistic shift. This period also introduces the first Cypriot architects in the dataset.

A shift is visible in the 1950–1963 houses. All examples apply new housing typologies, articulated volumes, and clearer functional zones. Spatial innovations are present, including verandas, balconies, recessed terraces, and cantilevered elements. More systematic indoor–outdoor continuity is supported by larger openings and integrated shading devices. Many of these elements are parallelly and widely observed in Mediterranean spatial practices, such as extended terraces, deep eaves, and semi-open living areas. Modernist language becomes dominant where the façades are presented as a visually continuous surface, uniform plastered finishes, horizontal window bands, and rectilinear geometric volumes enabled by reinforced-concrete structures. Planar façades rely on simple openings and structural articulation, with minimum ornamentation. Carved stone frames, profiled cornices and decorative ironwork are mostly not seen. The emphasis is on volume, proportion and light–shade effects. These formal characteristics reflect the maturing of regionally adapted modernism within the Mediterranean context. Most houses from this period were authored by Cypriot architects.

In the 1963–1974 examples, typological adaptations continue but vary across cases, reflecting different site conditions. Spatial innovations persist as verandas, balconies, recessed areas, and semi-open spaces remain in use. Such features continue to align with Mediterranean domestic configurations where outdoor transitional zones retain functional importance. Modernist vocabulary remains the primary formal language, again with planar façades, reinforced-concrete surfaces, minimal ornament, and geometric volume composition. The design of windows and doors becomes more uniform, more repetitive and less varied in proportion or articulation, reflecting a pragmatic approach. With all these elements, it can be said that the Mediterranean-oriented modernist expression is sustaining. All examples from this phase were designed by Cypriot architects.

The patterns mentioned here provide a foundation for interpreting how regional and Mediterranean characteristics were integrated and transformed across the four periods that will be further examined in the Discussion Section.

7. Discussion

This section interprets the findings presented in the previous section and interprets them within a broader cultural, environmental, and socio-political context. The discussion explores the relationship between the data and the literature, thereby explaining how modern housing production reproduces regional identity.

The incorporation of Mediterranean elements in houses designed between the 1930s and 1974, shaped by the cultural, socio-political, and historical dynamics of Cyprus’s colonial and post-colonial periods, reflects a distinct expression of regionalism. These elements demonstrate how modern housing remained strongly rooted in locality while engaging with broader processes of modernization. Their consistent use highlights regionalism’s influence, both within Cyprus and in relation to the global discourse on Mediterranean modern housing.

In the analyzed examples, courtyard-inspired spaces and semi-open terraces reflect regional Mediterranean architecture. Mediterranean regionalism thus combines continuity and change, shaped by the region’s settlement patterns. Semi-open spaces play a crucial role not only in terms of climatic performance but also in the production of cultural and symbolic meaning. In the Mediterranean context, shaded transitional spaces, verandas, and open-air living spaces function as cultural carriers that ensure the “inside-outside” continuity, contributing to the shaping of everyday sociality, privacy practices, and spatial habits. Castilla & Sánchez-Montañés [

52] emphasize that spatial forms are semiotic and communicative structures that acquire meaning through lifestyle, the relationship between openness and closure, and social identity. Similarly, Fernández-Galiano [

53], demonstrates that climatic adaptation in Mediterranean dwellings carries not only physical but also symbolic value integrated with cultural identity. In this context, the semi-open spaces examined in this study are considered both a means of environmental adaptation and meaningful architectural elements that spatially reflect the Mediterranean culture of living.

The selected houses also demonstrate effective use of structural materials, appropriately sized openings, and basic climate control strategies such as cross-ventilation. With Cyprus’s summer temperatures exceeding 40 °C, such features clearly reflect a regional Mediterranean approach to climate control. Overhanging eaves, semi-open areas, sunshades, and round columns became prominent features (

Table 1 and

Table 5). From 1960 to 1974, volumes became more prismatic with bold projections (

Table 4). Balconies, conceived as projecting or cantilevered volumes, extended living spaces outward and encouraged outdoor use, reflecting evolving lifestyles and integrating modern design approaches into regional architectural traditions (

Table 7 and

Table 8).

Through these facade elements, modernist principles and regional Mediterranean qualities were not only synthesized but also materially and visually expressed, positioning the facade as the primary medium through which Cyprus’s modern housing conveyed its evolving architectural identity. Thus, yellow stone supported both structural and climatic functions while reinforcing local material identity. These combinations reflected a deliberate integration of modern construction technologies with familiar surface languages, preserving continuity while advancing spatial and structural innovation. As Kazepides [

54] notes, such approaches demonstrated efforts to root modern architecture in place-specific material culture.

After 1950, local stone largely lost its structural role but remained significant as a decorative and symbolic element. It appeared as cladding on exterior and interior surfaces, particularly on ground floors, where it contributed to thermal comfort and evoked traditional textures (

Table 3,

Table 7 and

Table 8). Meanwhile, advances in concrete construction enabled simpler, exposed surfaces often combined with white and blue color schemes reflecting regional sensibilities (

Table 4,

Table 7 and

Table 8). Ultimately, the selection and adaptation of materials and structural systems in modern Cypriot housing reveal how global modernist ideals were negotiated within local climatic, cultural, and historical frameworks. Materiality thus became a critical medium through which Cyprus’s modern housing reinterpreted colonial legacies, reinforced regional belonging, and articulated a distinctive Mediterranean architectural identity.

7.1. The Home as a Medium of Cultural and Spatial Change

Although early modern housing in Cyprus reflected evolving architectural styles and shifting class dynamics, its cultural impact became most apparent within the home. It was there—in the layout of rooms, the structure of daily life, and the rhythms of family interaction—that the influence of modernism truly took hold, revealing how domestic space could act as both a carrier of tradition and a site of transformation.

The spread of modern housing in the 1950s and 1960s closely tracked broader changes in Cypriot society, including rapid urbanization and socio-political reform. Modernist homes began to appear more frequently in central neighborhoods and growing suburbs, especially in Nicosia. Their design emphasized practicality, spatial clarity, and alignment with emerging ideas of modern living [

55]. At the same time, these changes reflected the rise of a new professional middle class—educators, public servants, and other white-collar workers—who embraced modern architecture as part of their social identity [

31].

These homes were more than structures; they played an active role in reshaping cultural life. Interior layouts moved away from traditional, multi-generational living and toward nuclear family arrangements that prioritized privacy and autonomy. Social habits shifted, too. Dress codes, guest hosting, and everyday etiquette all began to reflect new, more formalized values [

56]. Kitchens became enclosed and more specialized, bedrooms more individualized, and household tools more efficient. These changes also altered gender roles. Modern appliances and organized layouts reduced the time needed for housework, giving women more room to participate in public life and community activities [

31].

For Turkish Cypriot women, these domestic changes overlapped with broader ideological currents from the Republic of Turkey. Influenced by Atatürk’s reforms, early Republican ideals promoted secularism, education, and gender equality as part of national progress. These ideas, carried through schools, media, and returning professionals, helped reshape expectations about women’s roles in both the home and society at large. Legal advancements and increased access to education redefined women’s roles in public and private life. These ideals, disseminated through Turkish-trained educators, bureaucrats, and media, shaped Turkish Cypriot society as well [

57]. Within this context, the architectural modernization of the home aligned with a wider discourse on women’s emancipation, where spatial transformation supported emerging expectations of autonomy, education, and civic engagement.

At the same time, traditional spatial values were selectively preserved. The courtyard, central to traditional Cypriot homes, was reinterpreted through design features such as semi-open verandas, inner gardens, L-shaped layouts, and terrace-linked living areas ([

58];

Table 7 and

Table 8). Even at the neighborhood scale, building orientation followed established street textures and preserved neighborly interaction [

50], blending new forms with local spatial customs.

7.2. Socio-Political Context

The architectural history of Cyprus has been shaped not only by aesthetic and technological shifts but by political ruptures, ethnic divisions, and socio-cultural transformations. In this context, modern housing emerged as a spatial projection of deeper dynamics—colonial control, national identity formation, and forced migration [

59]. Under British rule, housing was mobilized as a civilizing tool: Western typologies were promoted to transform local living practices and embed imperial ideologies in everyday space [

60]. Urban planning further entrenched ethnic divisions, especially in centers like Nicosia, where Turkish, Greek, and British neighborhoods were intentionally segregated.

Following independence in 1960, the Republic of Cyprus embraced modernism as a vehicle for national identity. During this phase, modern housing came to symbolize more than aesthetic modernity; it was used to express public modernization, class transformation, and state-led nation-building [

61]. However, this vision was quickly disrupted by the intercommunal violence of 1963–1964, which deepened spatial separation between Greek and Turkish communities. Housing design again became politicized, shaped by security concerns, territorial fragmentation, and questions of belonging [

62].

This politicization was especially evident in the houses of Turkish Cypriots after 1963. Amid rising tension and violence, homes in North Nicosia evolved into spaces of refuge and collective solidarity. They served as sites of both protection and informal political activity, reflecting a unique intersection of modernist ideals and the lived reality of conflict [

63]. These residences highlight how domestic architecture adapted to instability while retaining its symbolic and spatial modernity.

Following the 1963 inter-communal clashes, especially for Turkish Cypriot residents living in the northern neighborhoods of Nicosia, housing took on an additional socio-spatial role beyond the functions prescribed by daily life, shaped by insecurity and restricted mobility. While these houses were not directly designed for political purposes, the introverted layout, layered entrances, semi-open passageways that reduce visibility from the street, and recessed terraces seen in the examples examined in this study increased privacy, provided controlled access, and fostered a sense of security in daily life. For example, Abdullah Onar’s own house (1958) and the Ümit Süleyman Onan House (1961–63) feature recessed entrances and sheltered verandas that reduce direct visibility from the street. Similarly, the Desaini Aalotar–Ertoğrul Güven House (1961) offers deep passageways that buffer the public street from private life. In the tense atmosphere of the period, such spatial features allowed households and neighbors to come together for security and solidarity, enabling the residences to adapt to new social conditions while maintaining their modernist spatial structure. Thus, these houses demonstrate the flexible and socially relevant nature of architecture in the face of the period’s instability.

Meanwhile, global influences after World War II—through increased access to publications, architectural media, and educational mobility—accelerated Cyprus’s exposure to international modernism. Combined with the island’s internal political developments, these currents fueled the emergence of fully modern homes by the 1960s (

Table 3 and

Table 4). In this context, housing became a convergence point for international design, local identity, and political symbolism—revealing the complex cultural geography embedded in modern architecture.

The development of modern housing in Cyprus reflects more than a stylistic or technical shift; it embodies the layered intersection of colonial governance, urban modernization, cultural change, and political conflict. Initially a tool of imperial influence and later a marker of national identity, modern housing ultimately became a spatial response to displacement, division, and social transformation. As both a physical structure and a cultural symbol, it reveals how architecture mediates identity, power, and belonging in a society shaped by rupture and reinvention.

All of the buildings analyzed in this study, as presented in the tables, reveal a consistent integration of Mediterranean architectural characteristics, sensitivity to local context, and innovative combinations of modern design features. Together, these examples affirm that regionalism in Cyprus was not static, but dynamically interpreted by architects as a response to changing socio-cultural, political, and environmental conditions.

8. Conclusions

This study has explored how modern architecture in Cyprus, between 1930 and 1974, evolved through a dynamic negotiation between imported modernist ideals and deeply rooted local spatial traditions. It offers a broader conceptual framework for understanding regionalism as an adaptive and future-oriented strategy, rather than a nostalgic return to the past.

This analysis also positions regionalism not as a backward-looking embrace of tradition, but as an inventive approach to designing architecture that is both contemporary and rooted in place. By fusing recognizable local forms with modern materials and design strategies, Cypriot architects questioned the assumption that modernity demands uniformity. In doing so, architecture became a mediating force—linking international currents with the specific social, cultural, and environmental needs of the island. Cyprus offers a compelling illustration of how cultural continuity and architectural innovation can coexist. As an island shaped by successive periods of Lusignan, Venetian, Ottoman, and British rule, its built environment bears visible layers of influence—where structures have changed functions over time or blended stylistic and material elements from multiple eras. These architectural adaptations reflect a long-standing capacity for cultural negotiation and resilience.

In the 20th century, daily life was transformed by the changes in lifestyles imposed by modernism and the desire for modernity of the emerging Cypriot elite. The shift from extended to nuclear family living, the growing public presence of women, and evolving domestic routines mirrored broader societal changes. Yet rather than erasing tradition, modernism in Cyprus frequently reinterpreted it. Housing designs did not simply adopt international templates but absorbed familiar spatial arrangements, materials, and atmospheres—offering a modern vernacular rooted and open for innovation. This synthesis reveals both the conceptual flexibility of modernism and the creative agency of Cypriot architects in shaping a modernity rooted in context. However, the majority of the residences analyzed are modern homes designed to meet the demands of upper-income groups. Therefore, this study does not aim to be a complete representation of housing practices across the island; rather, it focuses on understanding the spatial preferences of an elite segment yearning for modernization.

Within this context, modern houses in Cyprus were more than shelters or design experiments. They embodied the layered experiences of colonialism, independence, and community transformation. Over time, they became traces of negotiation—between past and future, and between imported ideas and local realities. The study, founded on Mediterranean regionalism, challenges conventional interpretations of modern architecture as a unidirectional export of Western ideals. In Cyprus, modern housing did not merely copy outside models—it responded to them by peeling back layers of history, recreating something different. That dual capacity holding both memory and change is what gives Cypriot modernism its significance. It shows how architecture can embody both continuity and transformation within a single modernist language.

This study systematically explores the development of modern residential architecture in Cyprus between 1930 and 1974 from a Mediterranean regionalist perspective, providing a unique assessment of how local climatic strategies, spatial patterns, and façade elements were reinterpreted by modernism. The findings demonstrate that semi-open spaces, material choices, and climate-focused design strategies carry not only functional but also cultural and symbolic significance. Future research could enrich the typological and spatial analyses presented in this study with quantitative data (e.g., shading performance, climatic simulations) or broader geographical comparisons. Furthermore, studies on the relationship between modern housing and user experiences, evolving social practices, and conservation policies will contribute to the literature on Mediterranean modernism and regionalism.

These concluding observations also link the findings with a broader architectural and environmental discourse. The material presented in this paper, as the historical analysis of modern housing in Cyprus, offers an understanding of how regionally grounded design strategies produced an adaptive architectural language that is still relevant today. Climate-conscious spatial arrangements, semi-open transitional zones, and material choices show how environmental adaptation can be embedded in ordinary domestic designs and local cultural patterns. These historical patterns point to design strategies that could support today’s discussions on sustainable and climate-sensitive housing, particularly in Mediterranean climates where outdoor living remains central in hot areas. The blend of modernist form and local spatial habits, visible especially in the 1950–1963 houses, suggests a practical direction for renewed regionalist design. Hence, these historical insights offer a perspective that can enrich debate on resilience and context-responsive contemporary housing.

In addition to these thematic implications, the study’s innovative value lies in its systematic, table-based comparative method and its periodization grounded in architectural evidence and socio-historical turning points. By analysing fourteen houses through consistent criteria, spatial transformation, and modernist language, the research offers a structured and transparent framework. Sampling of the houses makes visible a sequence of architectural shifts that had not been mapped in this way. The evaluation shows how modernism was absorbed and adapted in Cyprus and allows the results to be read as a structured dataset rather than a narrative description, which is uncommon in studies of Cypriot modern housing. Integrating regionalism and Mediterraneanism into this empirical matrix further advances scholarly understanding of how local identity, climatic adaptation, and modernist design converged in Cyprus between 1930 and 1974. This combined methodological and analytical approach can be taken as a replicable model for studying modern residential architecture in other regional contexts.