Linear Seismic Analysis and Structural Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using OpenSeesPy

Abstract

1. Introduction

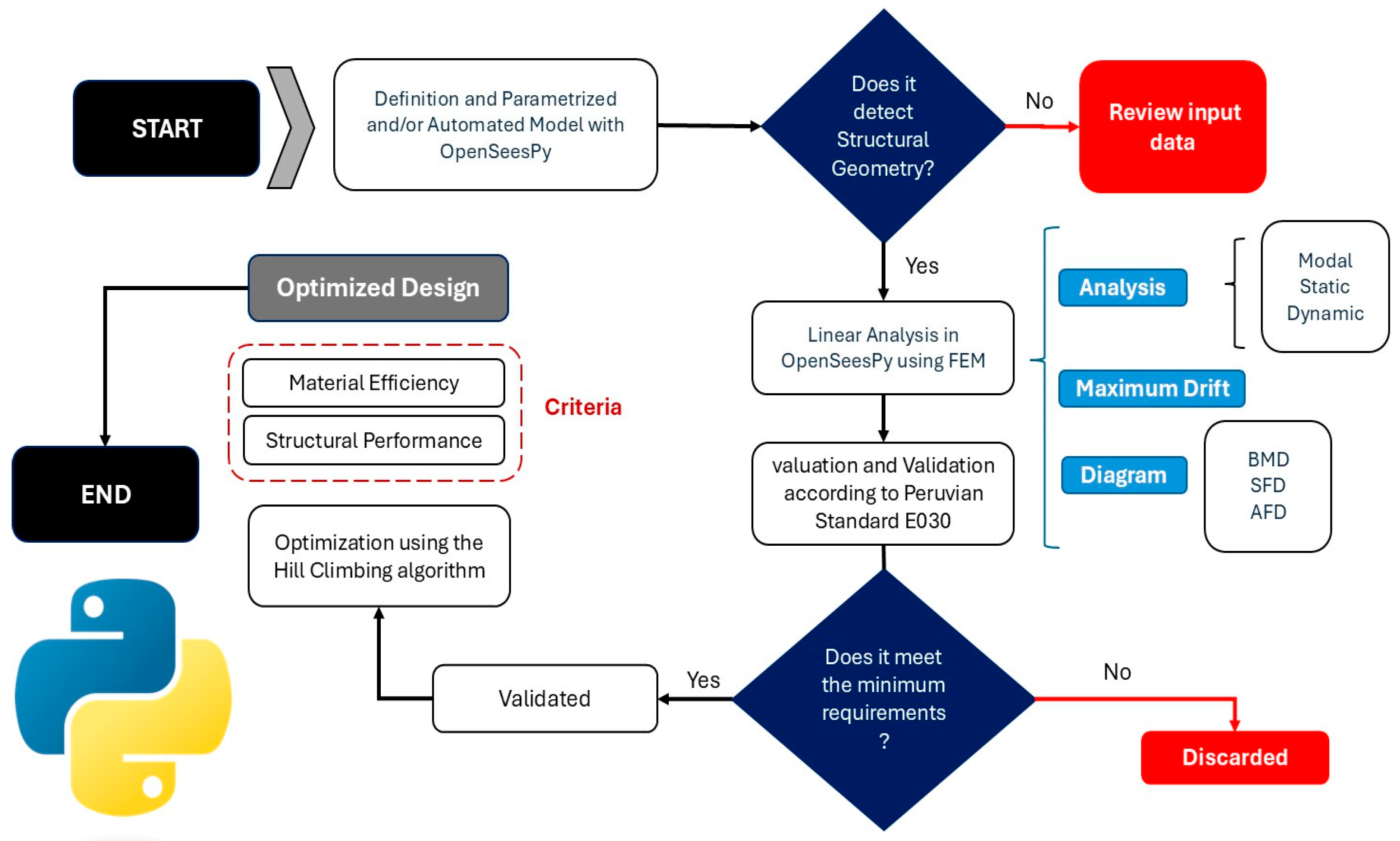

2. Methodology

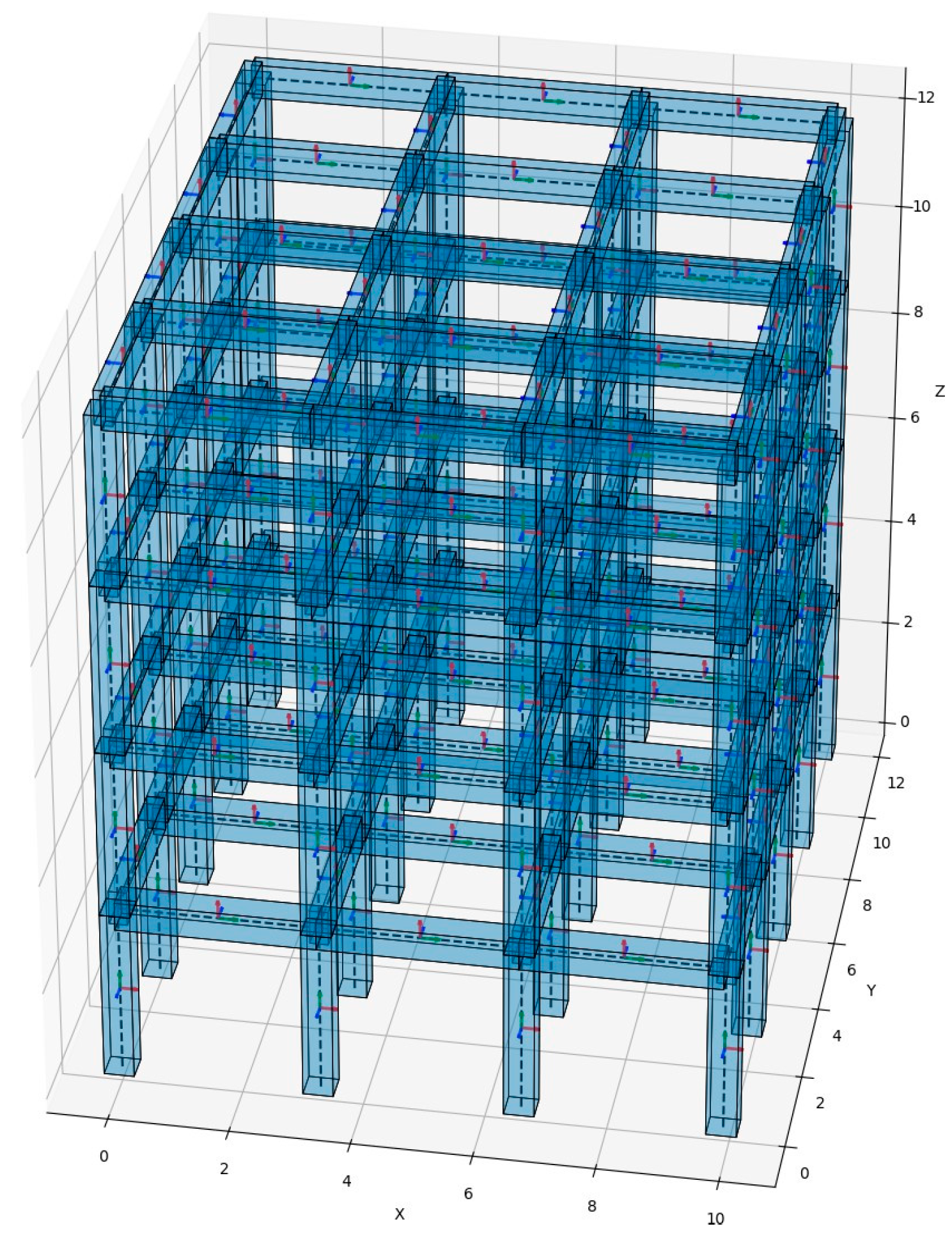

2.1. Geometric Definition and Structural Parameters

2.2. Material Properties

2.3. Load Definition

2.4. Seismic Parameters

2.5. Modeling and Boundary Conditions

2.6. Execution of Structural Analysis and Result Extraction

- Modal analysis: determination of the natural vibration periods and modal mass participation ratios.

- Linear static analysis: evaluation of displacements, internal forces, and the static base shear.

- Response spectrum analysis: calculation of the dynamic base shear and lateral displacements in accordance with the Peruvian Seismic Code E.030.

- Interstory drift verification: checking compliance with the maximum allowable drift specified by the code.

- Force diagrams: extraction of bending moment (BMD), shear force (SFD), and axial force (AFD) diagrams to assess structural behavior in detail.

2.7. Verification According to the Peruvian Seismic Code

- Interstory drift: verification against the maximum allowable limit of 7‰ of the story height.

- Modal mass participation: ensuring that the cumulative participation of the modes considered reaches at least 90%.

- Base shear scaling: checking whether the dynamic base shear requires scaling in order to satisfy the minimum base shear provision established by the code.

2.8. Parametric Optimization

- column side;

- beam width (m);

- = beam depth (m).

- The factor takes the value of 1.0 for = 210 kg/cm2 and 1.15 for = 280 kg/cm2.

- A solution is deemed infeasible (score = ∞) if any of the following constraints are not satisfied:

- ○

- Maximum interstory drift exceeds 7 ‰ (Peruvian Seismic Code E.030).

- ○

- Beam inertia ( = is greater than column inertia ( = (strong column–weak beam criterion).

- ○

- Beam depth-to-span ratio is outside admissible bounds.

- ○

- Minimum cross-sectional dimension of 0.25 m is not met.

3. Results

3.1. Modal Analysis and Mass Participation According to E.030

3.2. Modal Mass Participation

3.3. Static Analysis: Base Shear and Displacements

3.3.1. Static Analysis in the X Direction

3.3.2. Static Analysis in the Y-Direction

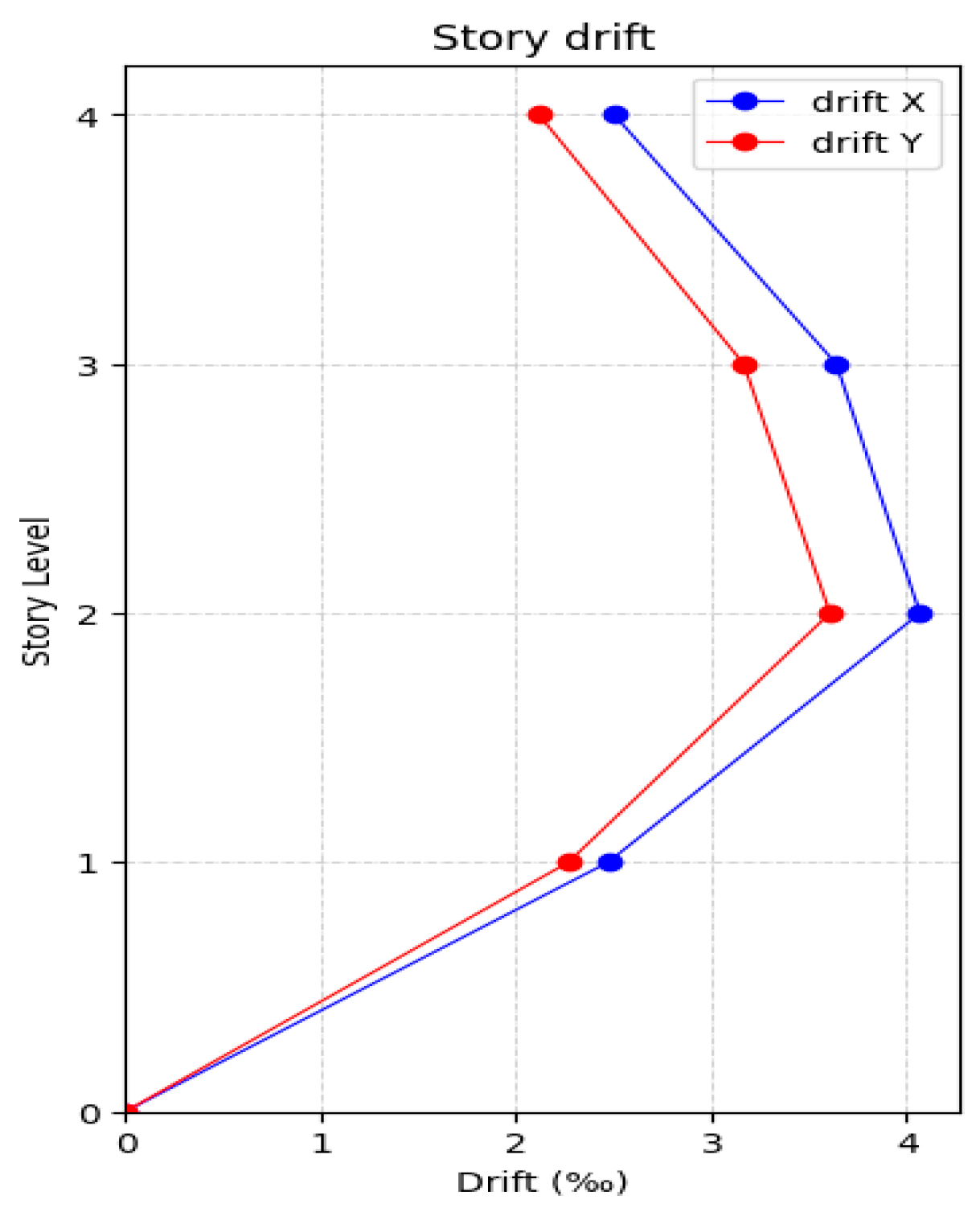

3.4. Dynamic Analysis: Ultimate Shear and Maximum Drifts

3.5. Extraction of Internal Force and Moment Diagrams

3.6. Optimization Using the Hill Climbing Algorithm

3.6.1. Dynamic Base Shear Forces

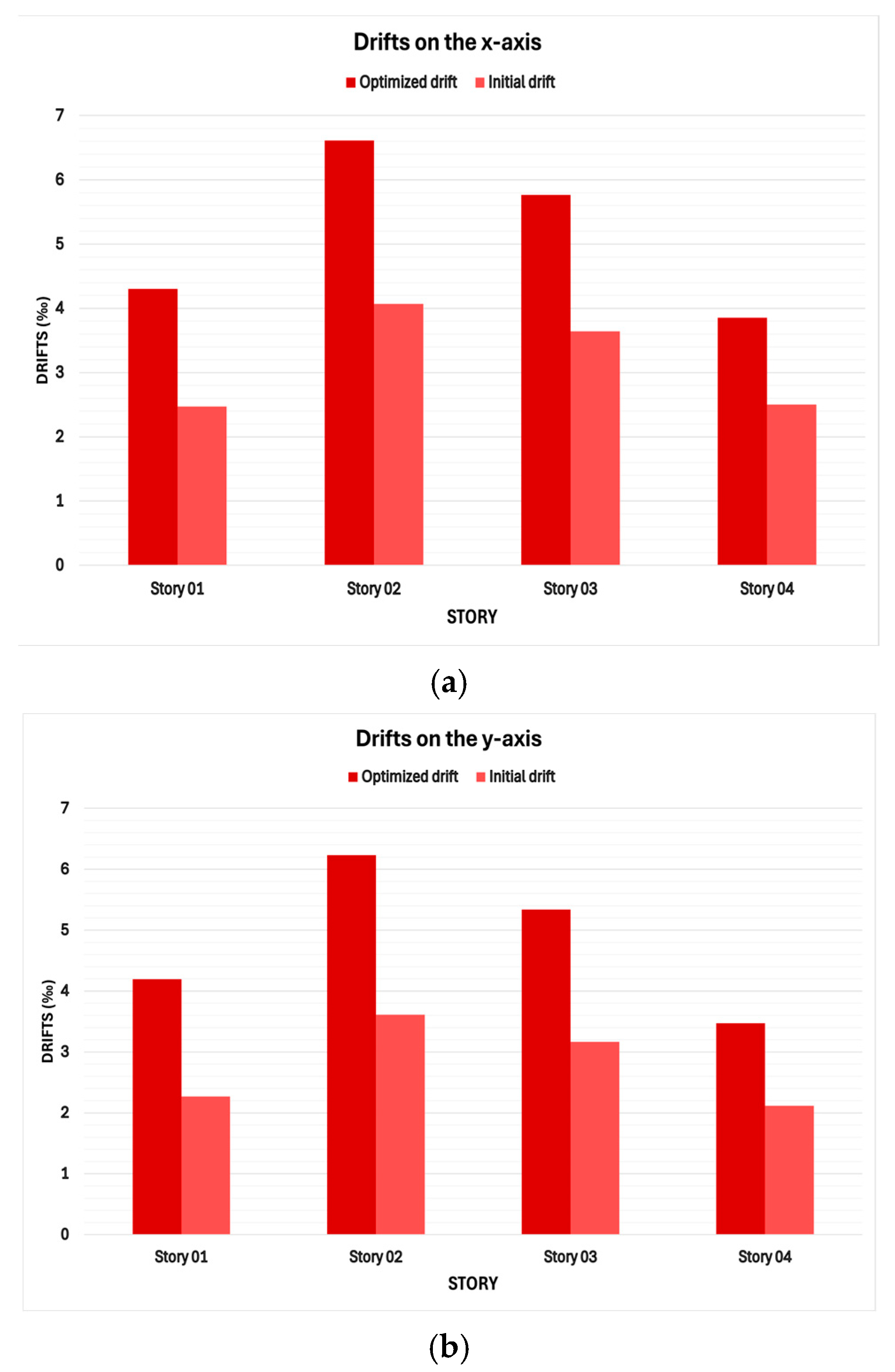

3.6.2. Story Drifts

4. Discussion of Results

4.1. Research Gaps and Contributions

4.2. Study Limitations

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mode No. | Period (s) | SumUx | SumUy | SumRz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode 1 | 0.37102 | 0.81114 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 |

| Mode 2 | 0.34850 | 0.81114 | 0.81735 | 0.00000 |

| Mode 3 | 0.29293 | 0.81114 | 0.81735 | 0.81998 |

| Mode 4 | 0.10797 | 0.93354 | 0.81735 | 0.81998 |

| Mode 5 | 0.10309 | 0.93354 | 0.93651 | 0.81998 |

| Mode 6 | 0.08742 | 0.93354 | 0.93651 | 0.93687 |

| Mode 7 | 0.05365 | 0.98338 | 0.93651 | 0.93687 |

| Mode 8 | 0.05245 | 0.98338 | 0.98432 | 0.93687 |

| Mode 9 | 0.04479 | 0.98338 | 0.98432 | 0.98434 |

| Mode 10 | 0.03482 | 1.00000 | 0.98432 | 0.98434 |

| Mode 11 | 0.03464 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 0.98434 |

| Mode 12 | 0.02960 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 |

References

- Sibenik, G.; Kovacic, I. Assessment of model-based data exchange between architectural design and structural analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kookalani, S.; Parn, E.; Brilakis, I.; Dirar, S.; Theofanous, M.; Faramarzi, A.; Mahdavipour, M.A.; Feng, Q.; O’rourke, L. Trajectory of building and structural design automation from generative design towards the integration of deep generative models and optimization: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärvegård, L.; Klasson, S.; Cusamano, L.; Rempling, R. Prerequisites for Using Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Structural Systems in the Conceptual Design Phase. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Mahmoodian, M.; Wang, S. Advancing Smart Construction Through BIM-Enabled Automation in Reinforced Concrete Slab Design. Buildings 2025, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.C.; Ullah, A.; Roy, B.; Chang, S.L. Finite element analysis and structure optimization of a gantry-type high-precision machine tool. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleymani, A.; Saffari, H. Seismic Improvement and Rehabilitation of Steel Concentric Braced Frames: A Framework-Based Review. J. Rehabil. Civ. Eng. 2023, 11, 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Duan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, J. A rcGAN-based surrogate model for nonlinear seismic response analysis and optimization of steel frames. Eng. Struct. 2025, 323, 119199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, B.; Benazouz, C.; Ahmed, M.; Abdelmounaim, M. Structural seismic design using hybrid machine learning and multi-objectives Particle swarm optimization algorithm: Case of Special moment frames in a high seismic zone. Structures 2025, 75, 108441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespino, E.; Adriaenssens, S.; Fraddosio, A.; Olivieri, C.; Piccioni, M.D. A multi-objective optimization approach for novel shell/frame systems under seismic load. Structures 2024, 65, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, O.; Feliciano, D.; Novoa, D.; Valcárcel, J. Opseestools: A Python library to streamline OpenSeesPy workflows. SoftwareX 2024, 27, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xie, Y. Opstool: A Python library for OpenSeesPy analysis automation, streamlined pre- and post-processing, and enhanced data visualization. SoftwareX 2025, 30, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Yarlagadda, T.; Zheng, Y.; Usmani, A. OPS-ITO: Development of Isogeometric Analysis and Topology Optimization in OpenSEES for Free-Form Structural Design. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2023, 160, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Hang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Liang, Q.Q.; Wang, Y. Development and implementation of shear wall finite element in OpenSees. Eng. Struct. 2024, 304, 117639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena-Garcia-Cruz, M.V.; Cattari, S.; Bento, R.; Morales-Esteban, A. Comparative study of alternative equivalent frame approaches for the seismic assessment of masonry buildings in OpenSees. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones: Norma E.020 Cargas; Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento: Lima, Peru, 2006.

- Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones: Norma E.030 Diseño Sismorresistente; Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento: Lima, Peru, 2019.

- Luke, S. Essentials of Metaheuristics, 2nd ed.; George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2013; Available online: http://cs.gmu.edu/~sean/book/metaheuristics/Essentials.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Di Trapani, F.; Sberna, A.P.; Marano, G.C. A genetic algorithm-based framework for seismic retrofitting cost and expected annual loss optimization of non-conforming reinforced concrete frame structures. Comput. Struct. 2022, 271, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyl, D.; Zhuang, B.; Rigby, S.; Bruun, E.P.G.; Bruun, E.; Jones, B.; Kastner, P.; Tien, I.; Gallet, A. OpenPyStruct: Open-Source Toolkit for Machine Learning-Driven Structural Optimization. Eng. Struct. 2025, 343, 120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ye, A.; Wang, X.; Guan, Z. OpenSeesPyView: Python programming-based visualization and post-processing tool for OpenSeesPy. SoftwareX 2023, 21, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of stories | 4 |

| Story height | 3.0 m |

| Total building height | 12.0 m |

| Number of bays (X direction) | 3 |

| Number of bays (Y direction) | 4 |

| Span length (X direction) | 3.3 m |

| Span length (Y direction) | 2.9 m |

| Beam section | 30 × 40 cm |

| Column section | 40 × 45 cm |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Compressive strength | |

| Elastic modulus | |

| Poisson’s ratio ν | 0.20 |

| Unit weight γ |

| Load Type | Value |

|---|---|

| Live load | |

| Slab self-weight | |

| Finishing load | |

| Partition walls load |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Seismic zone factor | |

| Short-period spectral period | |

| Long-period spectral period | |

| Response modification factor |

| Mode No. | Period (s) |

|---|---|

| Mode 1 | 0.371021 |

| Mode 2 | 0.348497 |

| Mode 3 | 0.292926 |

| Story | Vx (kN) | UxMax (cm) | UyMax (cm) | DriftX (‰) | DriftY (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | 380.0910 | 0.9660 | 0.0730 | 3.2199 | 0.2435 |

| Story 2 | 342.0819 | 2.5662 | 0.1893 | 5.3342 | 0.3875 |

| Story 3 | 266.0637 | 3.9779 | 0.2891 | 4.7054 | 0.3327 |

| Story 4 | 152.0364 | 4.9218 | 0.3536 | 3.1465 | 0.2150 |

| Story | Vy (kN) | UxMax (cm) | UyMax (cm) | DriftX (‰) | DriftY (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | 380.0910 | 1.0395 | 0.9391 | 3.4649 | 3.1305 |

| Story 2 | 342.0819 | 2.7567 | 2.4481 | 5.7242 | 5.0299 |

| Story 3 | 266.0637 | 4.2687 | 3.7556 | 5.0398 | 4.3583 |

| Story 4 | 152.0364 | 5.2774 | 4.6087 | 3.3623 | 2.8437 |

| Story | Vx (kN) | Vy (kN) | UxMax (cm) | UyMax (cm) | DriftX (‰) | DriftY (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Story 1 | 322.5558 | 324.4534 | 0.7418 | 0.6808 | 2.4726 | 2.2693 |

| Story 2 | 289.5358 | 290.5077 | 1.9618 | 1.7628 | 4.0692 | 3.6090 |

| Story 3 | 228.7108 | 229.1734 | 3.0082 | 2.6705 | 3.6414 | 3.1673 |

| Story 4 | 136.2960 | 135.6897 | 3.7353 | 3.2853 | 2.5037 | 2.1182 |

| Parameters | Beam (m) | Column (m) | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 0.30 × 0.40 | 0.45 × 0.45 | 0.3708 |

| Optimized | 0.25 × 0.35 | 0.40 × 0.40 | 0.2415 |

| Story | Initial Shear Force (kN) | Optimized Shear Force (kN) | Variation (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story 01 | 322.5558 | 240.3829 | 25.48 |

| Story 02 | 289.5358 | 212.0372 | 26.77 |

| Story 03 | 228.7108 | 168.7928 | 26.20 |

| Story 04 | 136.2960 | 103.218 | 24.27 |

| Story | Initial Shear Force (kN) | Optimized Shear Force (kN) | Variation (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story 01 | 324.4534 | 280.5651 | 21.25 |

| Story 02 | 290.5077 | 225.4505 | 22.39 |

| Story 03 | 229.1734 | 178.9891 | 21.90 |

| Story 04 | 135.6897 | 107.8655 | 20.51 |

| Story | Initial Drift (‰) | Optimized Drift (‰) | Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story 01 | 2.4726 | 4.3001 | 73.91 |

| Story 02 | 4.0692 | 6.6134 | 62.52 |

| Story 03 | 3.6414 | 5.7628 | 58.26 |

| Story 04 | 2.5037 | 3.8524 | 53.87 |

| Story | Initial Drift (‰) | Optimized Drift (‰) | Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story 01 | 2.2693 | 4.1947 | 84.85 |

| Story 02 | 3.609 | 6.2329 | 72.70 |

| Story 03 | 3.1673 | 5.3374 | 68.52 |

| Story 04 | 2.1182 | 3.4725 | 63.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llanos, D.; Delgadillo, R.M. Linear Seismic Analysis and Structural Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using OpenSeesPy. Buildings 2025, 15, 4388. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234388

Llanos D, Delgadillo RM. Linear Seismic Analysis and Structural Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using OpenSeesPy. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4388. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234388

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlanos, Diego, and Rick M. Delgadillo. 2025. "Linear Seismic Analysis and Structural Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using OpenSeesPy" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4388. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234388

APA StyleLlanos, D., & Delgadillo, R. M. (2025). Linear Seismic Analysis and Structural Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Frames Using OpenSeesPy. Buildings, 15(23), 4388. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234388