1. Introduction

As one of the most principal construction materials, conventional concrete is a brittle material and is susceptible to cracking. To enhance the mechanical properties and durability of concrete, fiber-reinforced concrete was developed. The incorporation of fibers such as steel, glass, and polymer can effectively restrain the development of cracks at both micro- and macro-scales, thereby improving the toughness and strength [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, conventional fibers exhibit a limited ability to inhibit nano-scale crack initiation and propagation. The development of micro-cracks can lead to a reduction in concrete strength [

7]. To address this issue, the use of nanomaterials has been explored to improve the mechanical properties of concrete [

8].

As a typical nanomaterial, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) possess excellent mechanical properties [

9,

10,

11] and the advantage of low density. The incorporation of CNTs can control nano-scale micro-cracks within cement-based materials and thus exert a positive influence on the mechanical properties of cementitious composites [

7]. However, the full potential of CNTs is often hindered by their tendency to agglomerate due to strong van der Waals forces [

12]. Achieving uniform dispersion is therefore a critical challenge. Various techniques, such as pre-dispersion in water using surfactants or surface functionalization, have been developed to address this issue and improve the interaction between CNTs and the cement matrix [

13].

The impact of CNTs on concrete strength has been studied extensively. Kumar et al. [

14] investigated the effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) on the strength of Portland cement mortar and found that the compressive and split tensile strengths of the composite reached their peaks when the MWCNT mass fraction was 0.5%, while the strength decreased when the content exceeded this value. Chaipanich et al. [

15] revealed that a 0.5% CNT mass fraction optimized the flexural strength of mortar with silica fume. Syed et al. [

16] showed that a 0.05% addition of MWCNTs increased the split tensile strength by 20.58% and the flexural strength by 26.29%. Xu et al. [

17] found that 0.1% and 0.2% MWCNT contents increased the flexural strength of cement mortar by 30% and 40%, respectively. Wang [

18] confirmed that CNTs significantly enhanced the flexural toughness index of Portland cement mortar, and that MWCNT incorporation improved pore size uniformity and reduced porosity. The 28-day test data indicated that the maximum fracture energy of the mortar reached 312.16 N/m, and its toughness increased by 47.1% (reaching 2.56) at 0.1% MWCNT content.

Based on the aforementioned research findings, it can be concluded that the enhancement of concrete strength by CNT incorporation is significant, with the influencing factors identified as CNT dispersion, mass fraction, and type. However, most existing experimental studies have focused on a single factor, often neglecting the synergistic effects among these variables. This highlights the need for a systematic and integrated analysis of their combined impact.

Concrete is an inherently complex system composed of various components, such as cementitious materials, aggregates, fibers, and admixtures, which are randomly distributed [

19,

20,

21,

22]. This heterogeneity makes it challenging to accurately predict its mechanical properties, especially its compressive strength [

23,

24,

25]. While numerical simulations can predict concrete behavior, they are often hampered by the complexity, nonlinearity, and randomness of the interaction mechanisms between the components and the microstructure [

26,

27,

28]. The prediction becomes even more intricate for CNT-enhanced concrete, where additives like nanofibers and surfactants are introduced. Factors such as CNT content, surfactant type, surface functionalization, and dispersion methods all influence the compressive strength. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising alternative. Compared to traditional approaches, a distinct advantage of ML is that it can learn directly from data without being constrained by the underlying physical mechanisms and thus can provide more accurate predictions [

29,

30,

31].

In predicting the mechanical properties of CNT-reinforced cement composites, researchers have predominantly focused on the accuracy of ML models. Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF) algorithms were employed by Nazar et al. [

32] to estimate the compressive strength of nanomaterial-modified concrete, with the RF model showing superior performance and accuracy. Similarly, Jiao et al. [

33] compared mainstream models (e.g., DT, Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network, Supported Vector Machine (SVM)) with ensemble methods (e.g., Bagging, Boosting), revealing that ensemble models significantly outperform standalone algorithms in error reduction and predictive capability.

Beyond model performance, other studies have delved into the influence of material characteristics. Huang et al. [

34] noted that ML models exhibited stronger generalization for compressive strength prediction than traditional response surface methods. Their analysis identified CNT length as a key factor for compressive strength, while curing temperature had the most significant impact on flexural strength. Adel et al. [

35] concluded that XGBoost achieved the highest reliability in predicting compressive and flexural strength compared to RF and AdaBoost. Their analysis further revealed a positive correlation between curing age and compressive strength, whereas the water–cement ratio, CNT content, and CNT diameter showed significant negative correlations. Other research has confirmed the significant impact of specimen size on 28-day compressive strength [

36]. Yang et al. [

37] utilized Gene Expression Programming (GEP) and Random Forest Approximation models, where the GEP model excelled in deriving empirical equations. The SHAP analysis identified the curing time, cement type, and water–cement ratio as the most influential factors. Li et al. [

38] used SHAP to confirm that CNT content and diameter significantly affect compressive strength and identified the optimal parameters as a length of 20 μm, diameter of 25 nm, and content of up to 0.1%. However, it is noteworthy that the conclusions on key influencing factors are not consistent across these studies, which suggests potential systematic differences in their underlying datasets, feature selection, and modeling approaches.

Previous studies on ML models of the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced cementitious materials have significant discrepancies in feature selection, modeling algorithm adoption, and data volume. Basic parameters, including curing days and cement dosage, were selected by Jiao et al. [

33] with 282 data points. Similarly, features such as the curing time and water–cement ratio were focused on by Yang et al. [

37] with 282 data points. Huang [

34] incorporated microscopic features like CNT morphology (outer diameter, length) and functional groups with a dataset of 114 points. Li et al. [

39] used parameters, including curing time and cement content, based on 282 data points. Furthermore, Nazar et al. [

32] selected features such as fine aggregate and cement content with 255 data points, while Adel [

35] incorporated features like the water–cement ratio and CNT type based on 276 compressive and 261 tensile strength data points. Li et al. [

38] involved features related to CNT dispersion with 149 and 107 data points for cement mortar and concrete, respectively. Manna [

40] focused on parameters such as the cement dosage and water–cement ratio with 295 data points. Features related to the specimen size effect were considered by Yang et al. [

36] with 151 data points.

A synthesis of the aforementioned studies reveals that while ML offers an effective approach for predicting the performance of CNT-reinforced concrete, existing research suffers from significant limitations. (1) Limited dataset size and incomplete feature dimensions: The feature sets adopted in different studies vary significantly, and the sample sizes are generally limited, typically ranging from 100 to 300 data points. The datasets for most predictive models do not adequately cover key control parameters that influence CNT dispersion performance. Specifically, they often lack features reflecting the dispersion process (e.g., sonication duration, type of dispersant, or surfactant) and specific surface chemical treatments. For instance, some studies [

32,

33,

37] primarily focus on basic mix proportions and fundamental CNT parameters. Although other research incorporates some microscopic parameters [

34,

35], it still lacks consideration of specific dispersion process features. This deficiency makes it difficult for the models to accurately capture the complex influence of dispersion on strength. (2) Bias in model selection, with a tendency towards single model types or an insufficient number of comparative models: Current predictions predominantly rely on traditional ML algorithms and ensemble methods. However, there is a lack of comprehensive comparison and validation across these different model types, making it difficult to objectively evaluate the applicable scenarios and predictive value of each model.

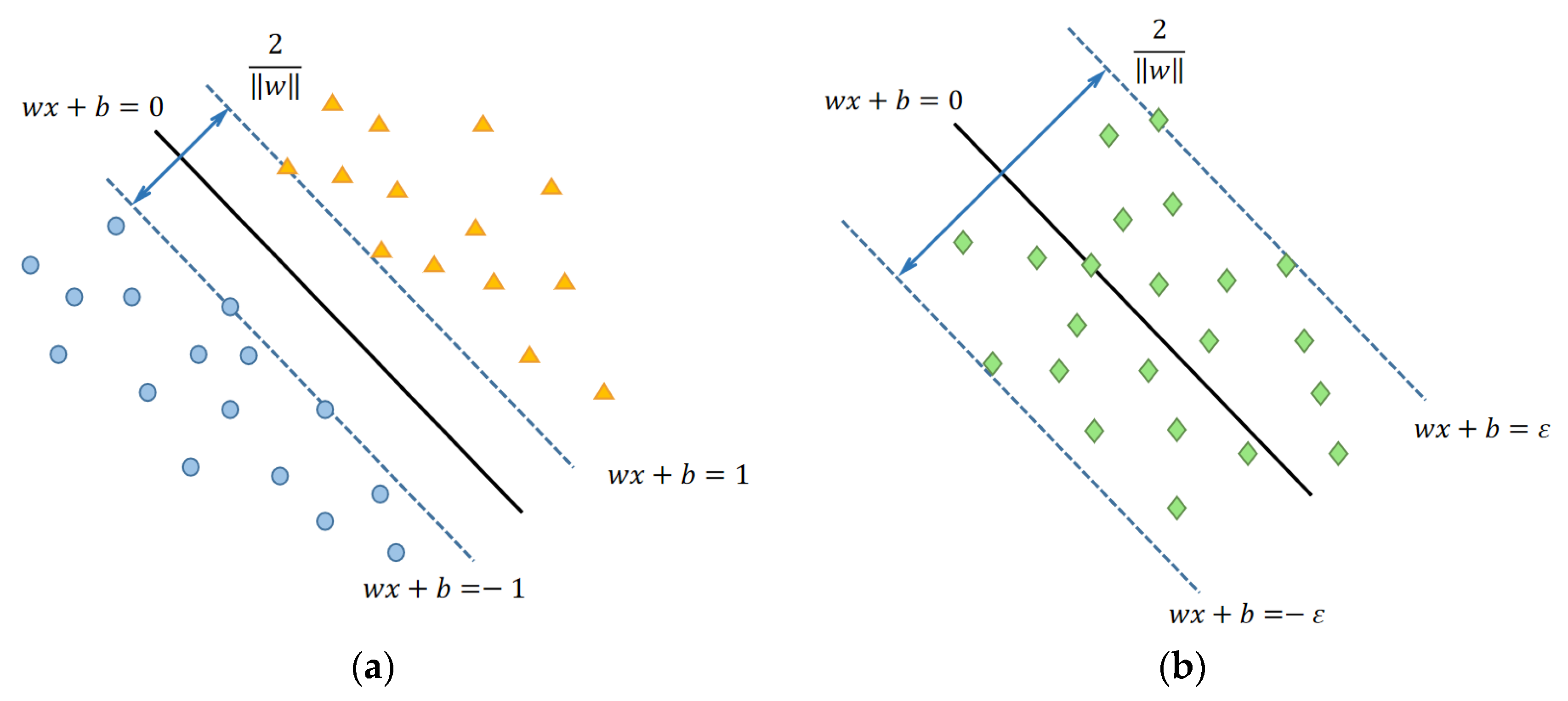

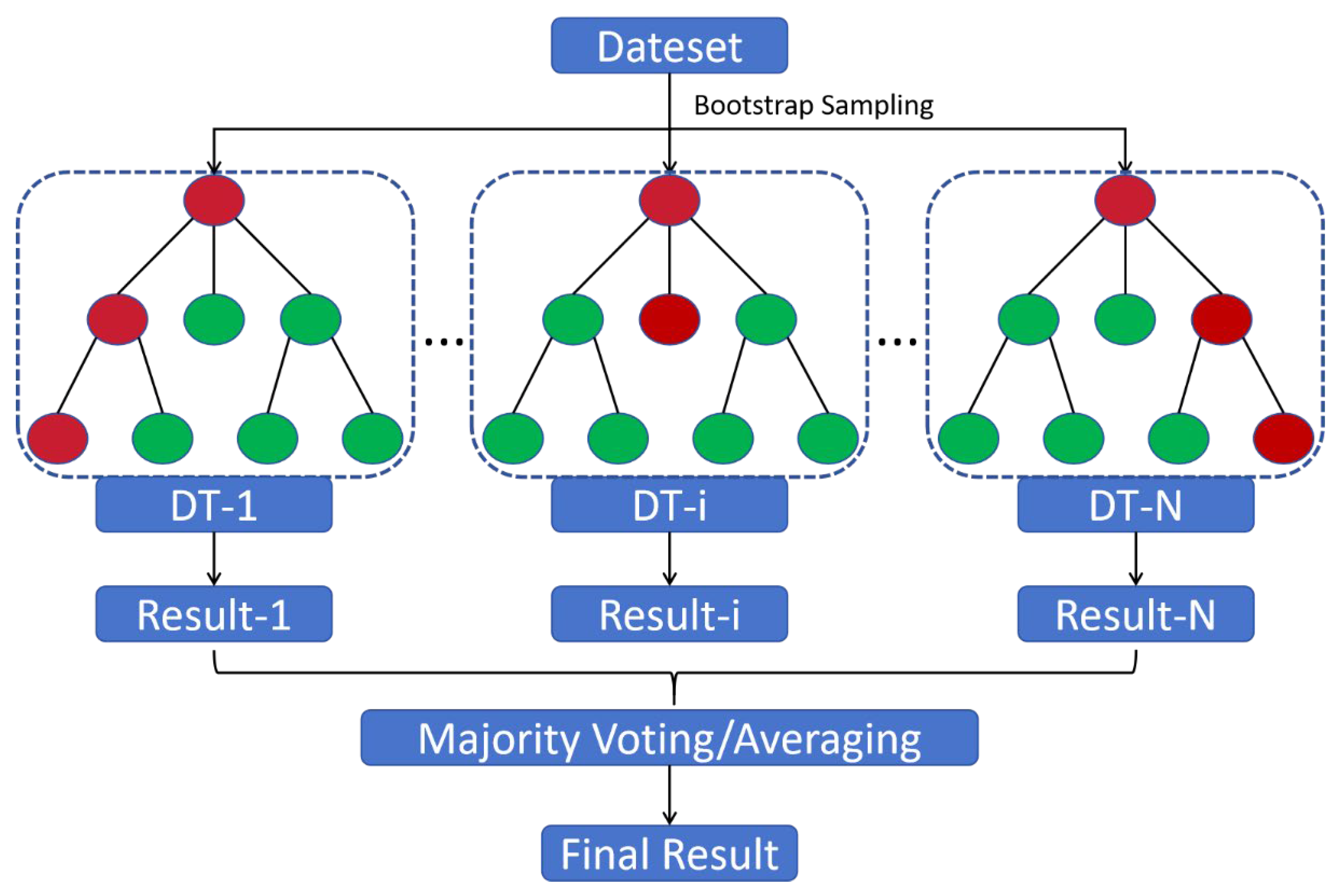

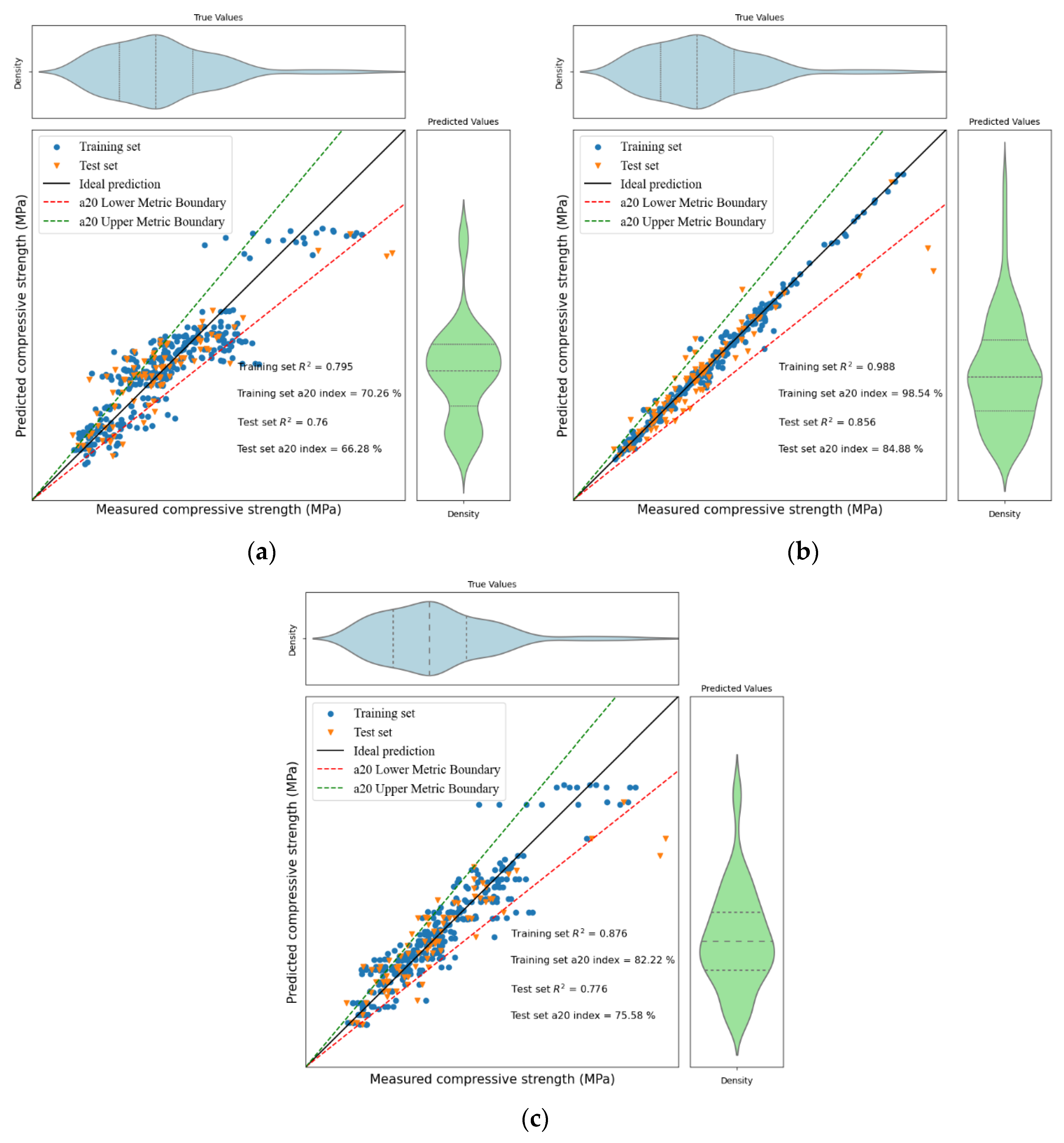

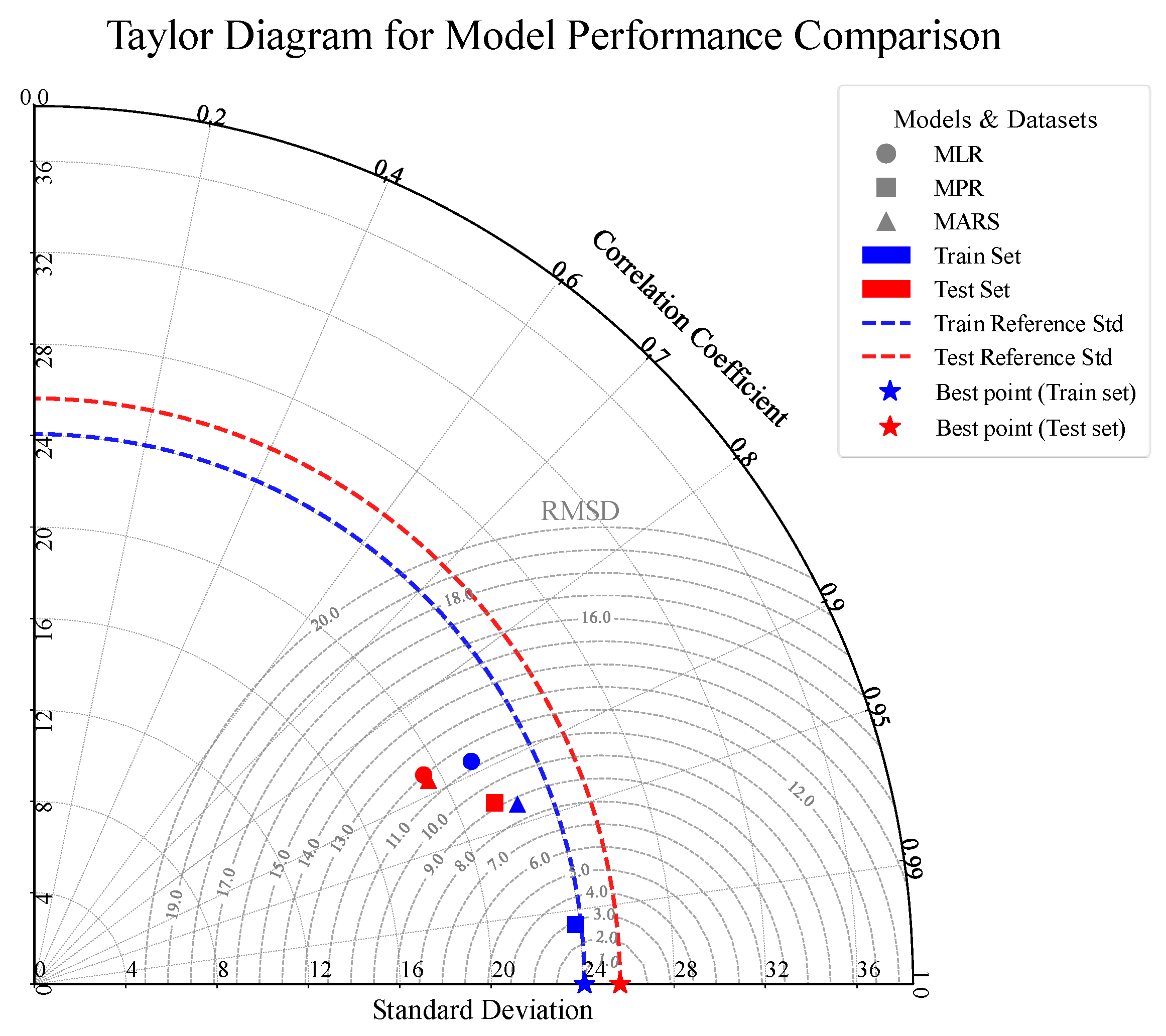

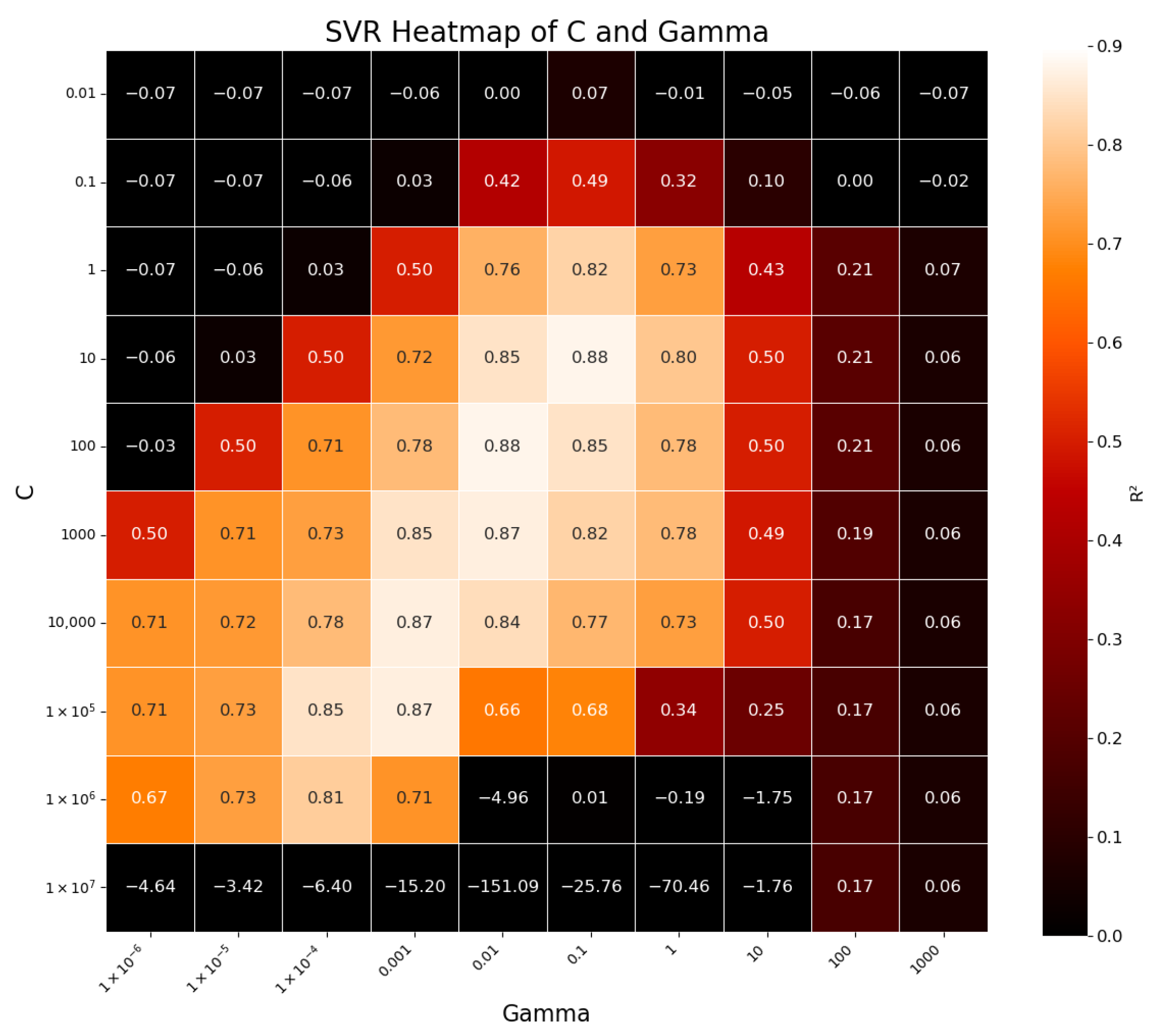

To address the aforementioned limitations, this study establishes a predictive framework for the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete based on a multi-dimensional database and multiple ML models. On the one hand, a comprehensive database was constructed with 429 experimental data points and with key CNT dispersion control parameters (e.g., sonication duration, surfactant type) and complete CNT morphological features (e.g., outer diameter, inner diameter, length). This multi-dimensional database covers 11 core influencing factors, including cementitious mix proportion parameters, CNT morphological features, dispersion process, interface modification, specimen geometry and size, and curing time. On the other hand, hyperparameter optimization and systematic validation of multiple ML models were implemented. Firstly, the performance of traditional regression models (Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Multiple Polynomial Regression (MPR), Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS)) was compared to identify the optimal model within this category. Secondly, Support Vector Regression (SVR), a mainstream classical model, was introduced as a reference to bridge traditional regression and ensemble models. Thirdly, ensemble learning models (Random Forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM)) optimized with two hyperparameter tuning methods—Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Bayesian Optimization (BO)—were compared to select the best-performing model in the ensemble category. Finally, a cross-type comparative validation was performed among the optimal traditional regression model, SVR, and the optimal ensemble learning model. This comprehensive evaluation assessed the predictive performance and applicable scenarios of different model types and identified the overall best prediction model. The methodological workflow of this study is summarized in

Figure 1.

3. Dataset Establishment

3.1. Data Collection

This study employed Systematic Search Flow [

76,

77] for literature search and data extraction. All the literature published between 2004 and 2024 was retrieved, and relevant papers with clearly described experimental conditions and detailed CNT material parameters were selected. The most commonly used cement type was Ordinary Portland cement. In some studies, supplementary cementitious materials such as fly ash or silica fume were also included, reflecting diverse mix designs. The CNTs were predominantly MWCNTs, with their key physical properties (diameter, length) included as features in our model. From these, 429 valid data samples were extracted.

3.2. Distribution of Data Samples

In this study, a feature system was systematically constructed from six dimensions: matrix mix proportions, CNT material parameters, CNT dispersion process, CNT interfacial modification, specimen geometry and size, and curing time. This approach aims to comprehensively cover the mechanisms influencing the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete.

Parameters of the cement matrix mix proportion (water–cement ratio, sand–cement ratio) were prioritized as feature variables, as they directly determine the cement hydration process and the aggregate interface structure, which are critical for the mechanical properties of concrete [

73]. CNT material parameters such as the mass percentage of CNT to cement, CNT outer diameter, CNT inner diameter, and CNT length were included as core features. These parameters not only quantify the physical state of the nano-reinforcement phase but also significantly influence its dispersion efficiency and stress transfer effectiveness in the cement matrix by modulating key indicators like specific surface area and aspect ratio [

7]. To accurately reflect the impact of the preparation process, parameters like sonication duration and surfactant type (see

Table 2) were introduced as feature variables. Such parameters directly affect the enhancement efficiency by altering the agglomeration state of CNTs. Simultaneously, as some CNT samples were chemically modified to introduce polar functional groups, treatments involving hydroxyl, carboxyl, and thiazole groups were included in the feature space. These chemical modifications fundamentally improve the macroscopic mechanical properties of the composite by enhancing the interfacial bonding strength between CNTs and the cement matrix. Furthermore, the specimen’s geometric shape (e.g., cube or prism) and dimensions (e.g., side length, height) were also included, as they directly influence the compressive strength test results. Curing age was introduced as a crucial time-dependent variable, because the strength of concrete develops continuously over time with the cement hydration reaction. Compressive strength was selected as the target variable.

The codes, units, and value ranges for all variables are shown in

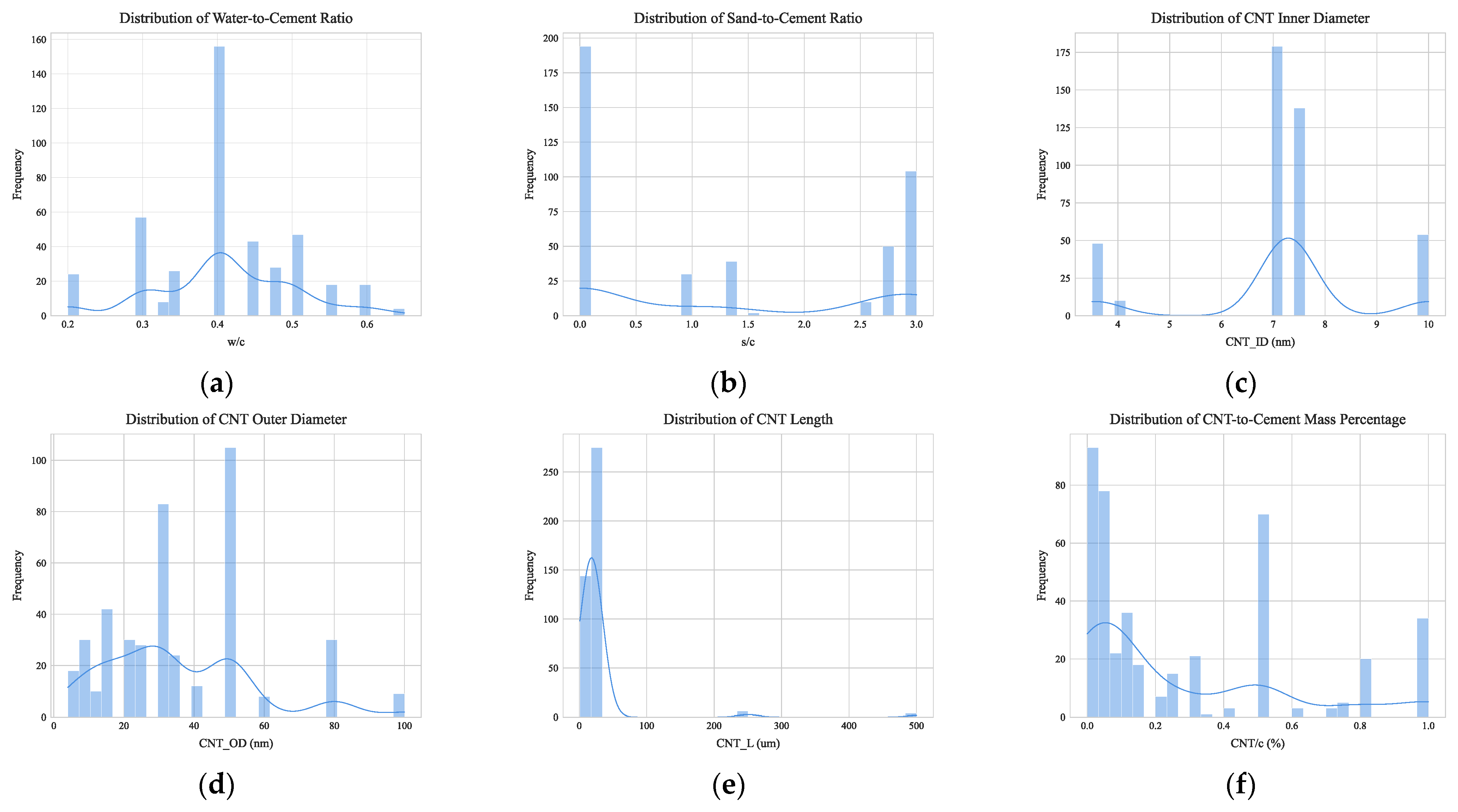

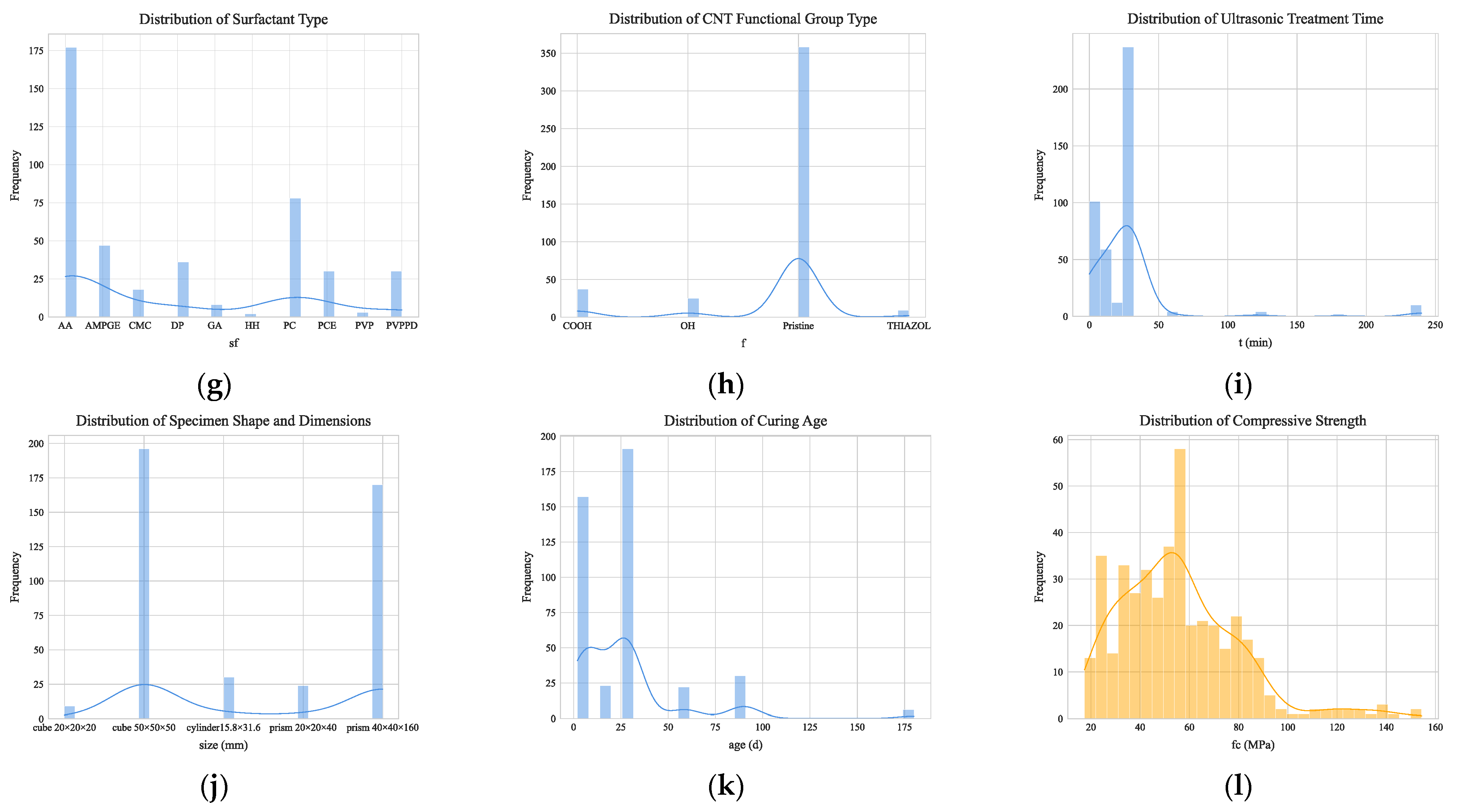

Table 3. The distribution characteristics of the 12 feature variables are analyzed in

Figure 6.

(1) Matrix mix proportions. The water–cement ratio shows a unimodal distribution centered at 0.4 (29.4%), with the 0.3–0.5 range covering 53.6% of the samples. Values of 0.2 (5.6%) and 0.6 (4.2%) provide data for the model to capture performance boundaries. The maximum sand–cement ratio is 3.0, corresponding to 103 samples. However, the majority of samples use a much smaller ratio, with values ranging from 0 to 0.2.

(2) CNT material parameters. Over 70% of CNT inner diameters are concentrated in the 7–7.5 nm range, with the remainder mainly at the extremes of 3.5 nm and 10 nm. In contrast, the distribution of CNT outer diameters is more uniform, with about 44% in the 30–50 nm range. For CNT length, 71.3% of samples use short lengths of 15–20 μm, while very few researchers use lengths over 200 μm. The mass percentage of CNT to cement varies from 0 to 1.0% with a wide range of values, which helps the model analyze the effect of different CNT dosages. The 0–0.3% dosage range and the 0.5% dosage are research hotspots.

(3) CNT dispersion process. Sonication time exhibits a unimodal distribution centered at 30 min (55.2%). Short-duration treatments of 0–20 min cover 39.2% of samples, with 5 min and 15 min as secondary concentration intervals. Long-duration treatments over 30 min account for only 4.7%, providing data to capture performance boundaries. Among surfactants, PC (28.6%) and AA (25.3%) are the most common, together covering 53.9% of samples. AMPGE (13.8%), PCE (11.2%), and DP (9.5%) follow, forming the mainstream selection. Types like PVP (1.8%) and HH (0.9%) have very low proportions.

(4) CNT interfacial modification. The choice of CNT functional groups shows a clear concentration trend. Pristine (no chemical treatment) is the most common, covering about 70% of samples. The COOH functional group accounts for about 15%, the OH group slightly less for about 12%, and the Thiazole group has the lowest proportion of about 3%.

(5) Specimen geometry and size. Cube 50 × 50 × 50 (cube, 50 × 50 × 50 mm) is the most common, covering about 50% of samples. Prism 40 × 40 × 160 (prism, 40 × 40 × 160 mm) is the next, at about 30%. Cylinder 15.8 × 31.6 (cylinder, 15.8 × 31.6 mm, diameter × height) accounts for about 10%. Cube 20 × 20 × 20 and prism 20 × 20 × 40 have the lowest proportions, each at about 5%.

(6) Curing time. The distribution of curing age shows a distinct concentration. The 28-day curing age is the most frequent, covering about 45% of samples. Medium-term ages of 7–14 days are next, totaling about 35%. Short-term ages of 3 days or less account for about 11%. Long-term ages of 58 days and above (including 58, 60, 90, and 180 days) have the lowest proportion, totaling about 16%.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

In the entire dataset, six features had missing data: w/c, CNT_ID, CNT_OD, CNT_L, sf, and t. The specific details of the missing values are shown in

Table 4.

Different strategies were adopted for different features with missing data. For the w/c, given its significant impact on the strength of cement-based materials and the small number of missing samples (only six), these samples were directly discarded. For the geometric dimensions of CNTs (CNT_ID, CNT_OD, CNT_L), the mean value of all samples was used to maintain data consistency and integrity. For samples with sonication duration missed, it was assumed that sonication was not used, as it is not explicitly stated in the original literature. Similarly, samples with a missing surfactant type were assumed to have “no surfactant used”.

The dataset contains three categorical features: specimen parameter (size), surfactant type (sf), and CNT functional group (f). The size feature was split into three new variables: shape type (cyl), side length or diameter (B), and height (H). The sf and f were processed using one-hot encoding to be converted into new variables. The one-hot encoding results for the functional group types are detailed in

Table 5.

To eliminate the influence of different scales and value ranges among variables, all data were normalized. This not only improves model accuracy but also accelerates the convergence speed when using optimization algorithms like gradient descent. Common normalization methods include Min-Max normalization and Z-score normalization. Given that Z-score normalization demonstrates better robustness against noise and outliers in the dataset, this method was chosen. The specific normalization formula is as follows:

where

is the normalized data,

is the original data,

is the mean of the data, and

is the standard deviation. After Z-score normalization, the data has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

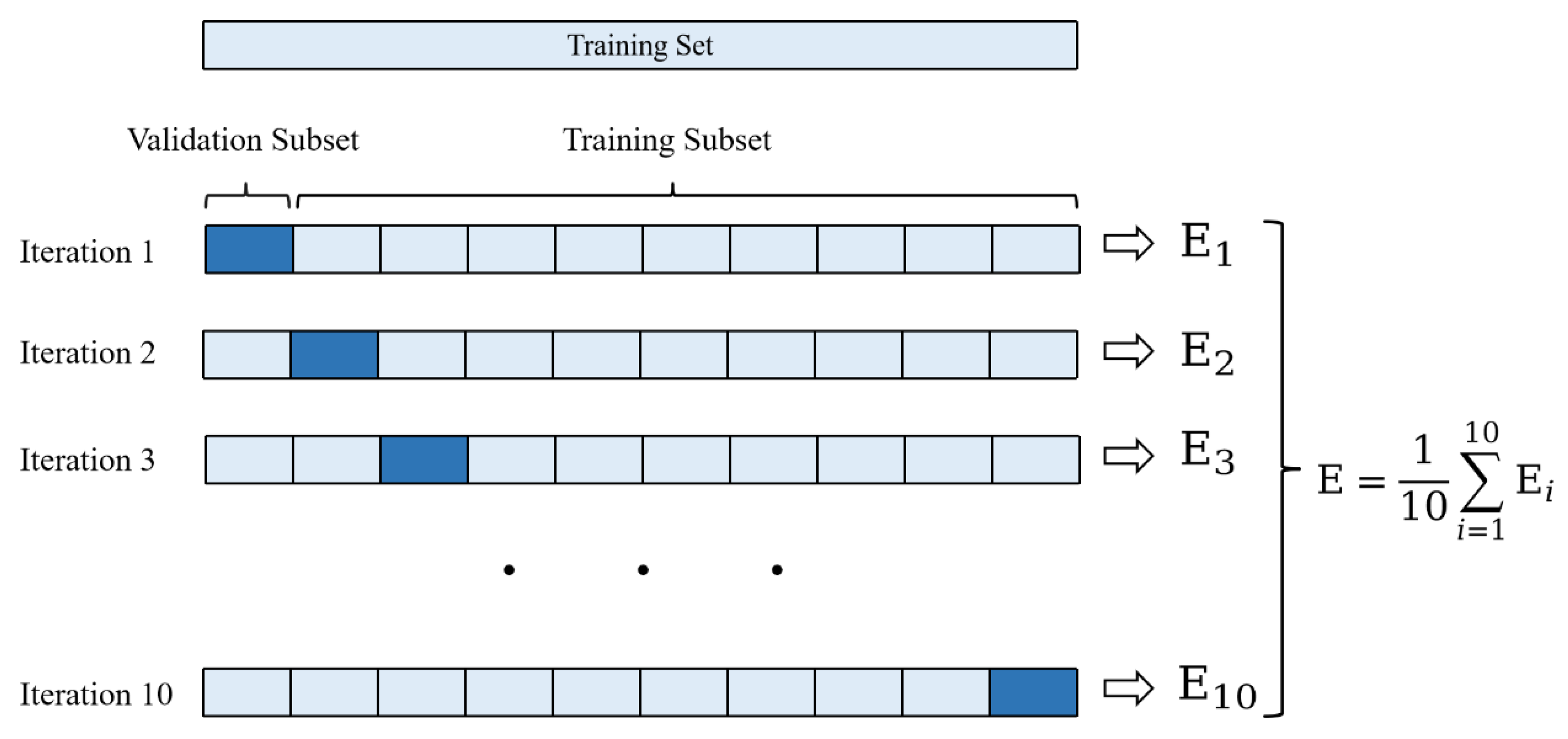

Finally, the dataset was randomly shuffled. It was then split into a training set (80%) to fit the model parameters and a test set (20%). To select an appropriate model and determine its hyperparameters, the training set was further subjected to ten-fold cross-validation, dividing it into training and validation subsets to prevent overfitting [

78].

3.4. Feature Correlation Analysis

The primary purpose of conducting a feature correlation analysis is to explore the interactions between different features and to identify those that have a significant impact on the target variable (the compressive strength of concrete in this study). First, identifying features highly correlated with the target variable can simplify the model and improve prediction accuracy. Concurrently, detecting strong correlations between features helps to avoid multicollinearity, preventing model instability and overfitting. Furthermore, analyzing the relationships between features allows for the identification of redundant and essential features, enabling efficient data preprocessing and providing a crucial theoretical basis for model construction and optimization.

In the feature correlation analysis, the color intensity represents the degree of correlation: red indicates a positive correlation, and blue indicates a negative correlation. The deeper the color, the stronger the correlation. The analysis results, as shown in

Figure 7, reveal that the sand–cement ratio and water–cement ratio exhibit the highest positive correlation, with a coefficient of 0.58. This is likely due to their interdependence in concrete preparation and performance. For instance, an increase in the water–cement ratio often requires a corresponding increase in the sand proportion to ensure uniform mixing. Conversely, the width or diameter of the specimen and the shape type show the highest negative correlation, with a coefficient of −0.65. This is mainly because the dimensions of cylindrical specimens in the dataset are limited to a single specification (“cylinder 15.8 × 31.6”), leading to an uneven sample distribution. Additionally, all samples using PCE-type surfactants have a CNT inner diameter of 3.5 nm. This skewed sample distribution results in a correlation coefficient of −0.60 between the CNT inner diameter and the surfactant PCE. The water–cement ratio is negatively correlated with compressive strength, with a coefficient of −0.59, which is consistent with findings from previous research [

79]. Apart from these feature pairs, most other pairs show low correlation coefficients, indicating weak relationships between them, although a few are elevated due to the uneven sample distribution in the dataset.

5. Model Interpretability Analysis

5.1. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) Plots

SHAP is a model explanation method rooted in cooperative game theory. It quantifies the contribution of each feature to a model’s prediction by assigning it a specific importance value, known as the SHAP value. For a given prediction sample

x, the SHAP value for feature

i, denoted as

, is mathematically defined as:

where

is the set of all features.

is any subset of features that does not include feature

.

is the model’s prediction using only the features in subset

.

is the total number of features.

This formula calculates the marginal contribution of feature by iterating through all possible feature subsets. It computes the change in the model’s output when feature is added to each subset and then calculates a weighted average of these contributions. The weighting ensures that the feature attributions satisfy desirable properties, such as symmetry and efficiency, which are grounded in axiomatic principles.

A key advantage of SHAP is its strong theoretical foundation, which guarantees consistency and local accuracy in feature attribution. This allows it to provide comprehensive insights into feature importance. SHAP is highly versatile, applicable not only to SVM, but also to tree-based ensemble models like RF, XGB, and LGBM. Furthermore, SHAP plots offer profound insights into a model’s decision-making process. They not only reveal the magnitude of a feature’s impact on a prediction but also visualize its direction (positive or negative), making the model’s logic more transparent.

5.2. Traditional Regression Models

The primary advantage of traditional regression models lies in their interpretability. Combined with the previous fitting analysis of the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete, the relationship between the target variable and the selected features is better suited to a multivariate polynomial form. The terms output by the MPR model are the products of feature variables (or their interaction combinations) and their corresponding polynomial coefficients. The sign of a coefficient indicates the direction of the effect, while its absolute value represents the magnitude.

By extracting the top ten terms with the largest polynomial coefficients from the MPR model’s output (see

Table 8), key influencing factors can be clearly identified. Age and the surfactant PC are the most critical determinants of compressive strength, followed by the water–cement ratio, mass percentage of CNT to cement, and dimensional parameters of CNT. Specifically, the term CNT_ID*CNT_L*CNT/c^2 shows a positive contribution to compressive strength, whereas sf_PC exhibits a negative effect. These patterns are quantified by the magnitude and sign of the coefficients. Although the MPR model intuitively represents the influence of feature variables on the target variable through a polynomial form, it is still difficult to directly determine the impact of a single feature variable on the target variable.

5.3. SVR

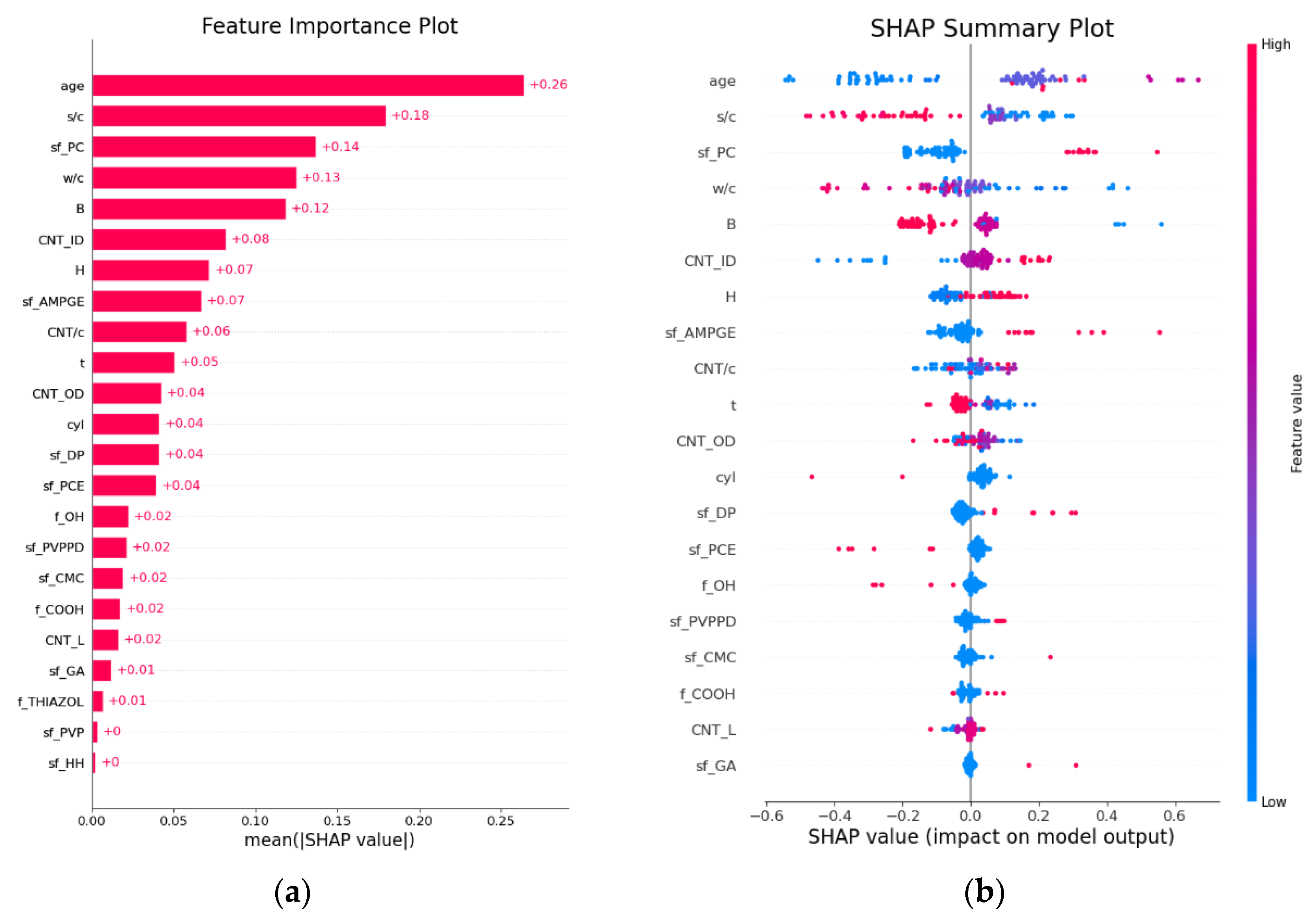

Since it is difficult to directly analyze the influence of features on the target variable from the results of an SVR model, this study introduces SHAP plots for model interpretability analysis.

Figure 20 presents the feature importance ranking and SHAP values for predictions by the SVR model. In terms of feature importance, the primary factor affecting the compressive strength is age, followed by the sand–cement ratio, surfactant PC, water–cement ratio, and specimen size. A lower curing age (blue dots) has a negative impact on compressive strength, while a higher age (red dots) has a positive impact, reflecting the trend that strength increases with age. The use of surfactant PC enhances compressive strength, whereas increasing the sand–cement ratio, water–cement ratio, or specimen side length or diameter reduces it. It is noteworthy that the CNT parameters (such as CNT inner diameter and CNT outer diameter) did not play a dominant role in influencing compressive strength, and the effects of CNT outer diameter and CNT length were even weaker. The positive effect of the surfactant PC is more prominent in the SVR model, which differs from the MPR model. It indirectly suggests that the SVR model places greater emphasis on the impact of CNT dispersion on compressive strength.

5.4. Ensemble Learning Models

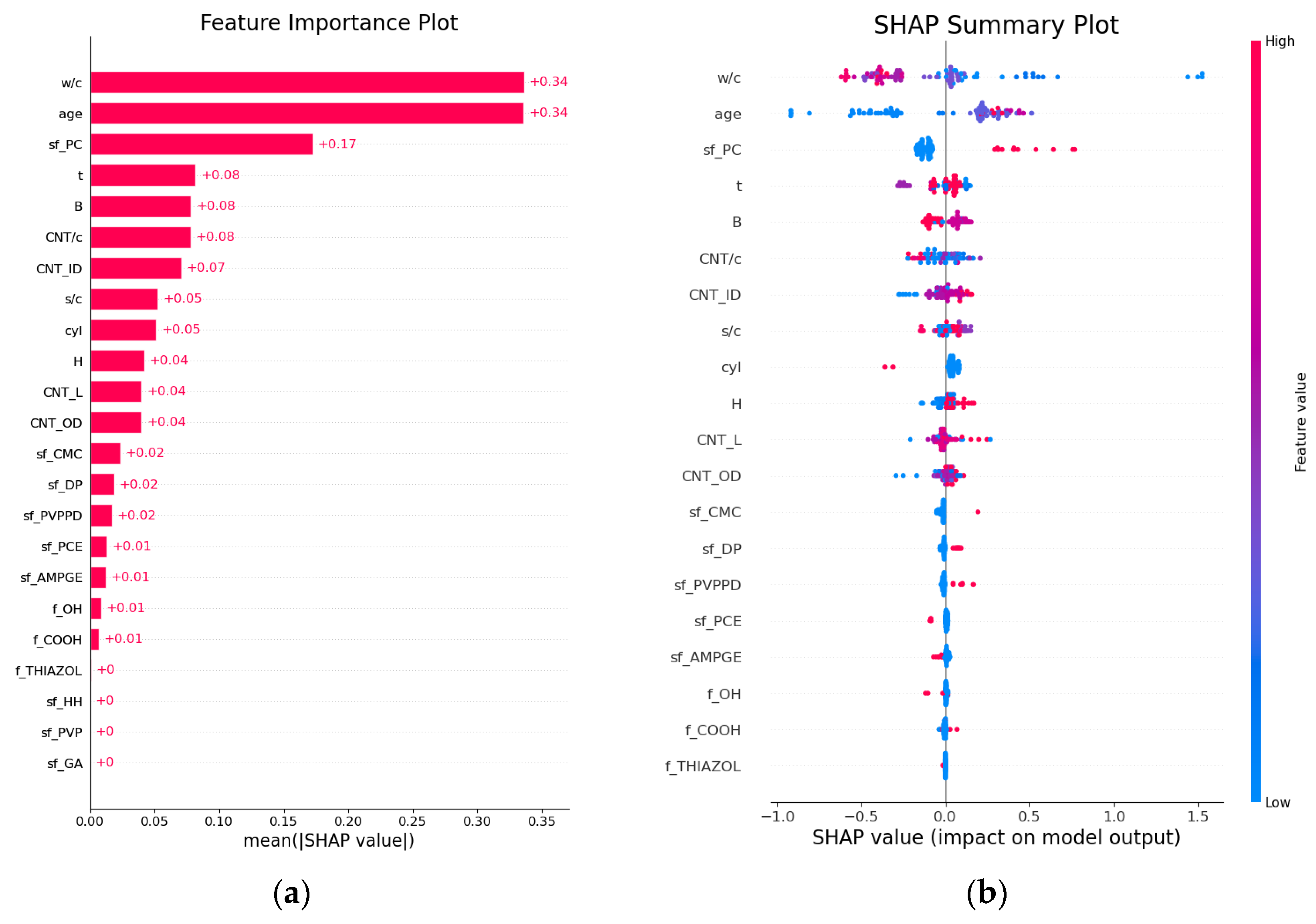

Given that the XGB model optimized by PSO performed the best, it was selected for SHAP analysis.

Figure 21 shows the feature importance ranking and SHAP values for the predictions by the PSO-optimized XGB model. In terms of feature importance, the primary factors affecting the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete are the water–cement ratio and age, followed by specimen size, surfactant PC, mass percentage of CNT to cement, and dimensions of CNTs. A lower water–cement ratio (blue dots) has a positive impact on compressive strength, while a higher ratio (red dots) has a negative impact, reflecting the trend that strength decreases as the water–cement ratio increases. The effect of curing age is the opposite. Using surfactant PC or increasing CNT inner diameter both enhance compressive strength. The relationships between mass percentage of CNT to cement, CNT outer diameter, CNT length, sonication duration, and compressive strength are not simple linear ones. For the mass percentage of CNT to cement, both excessively low and high values can lead to a decrease in concrete strength, indicating that there exists an optimal range for a mass percentage of CNT to cement to maximize strength. The specific boundaries of this range will be further analyzed in conjunction with SHAP dependence plots later.

5.5. Weighted Average Importance Analysis of Features

This study analyzed 23 feature variables related to the factors influencing the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete, categorized into six core dimensions: matrix mix proportions, CNT material parameters, dispersion process, interface modification, specimen geometry and size, and curing time. Due to the varying predictive performance of different models, a simple averaging of feature importance from each model would weaken the contribution of high-performance models and fail to accurately reflect the true influence patterns of the features. To more reasonably integrate the feature importance results from multiple models, this study quantifies the weight of each model based on its prediction performance metrics and calculates the weighted average importance of features using Equation (25).

where

is the score of the

i-th model.

,

,

,

, and

are the respective performance metrics for that model.

is the normalized score of the

i-th model.

is the importance of the

j-th feature in the

i-th model.

is the weighted average importance of the

j-th feature.

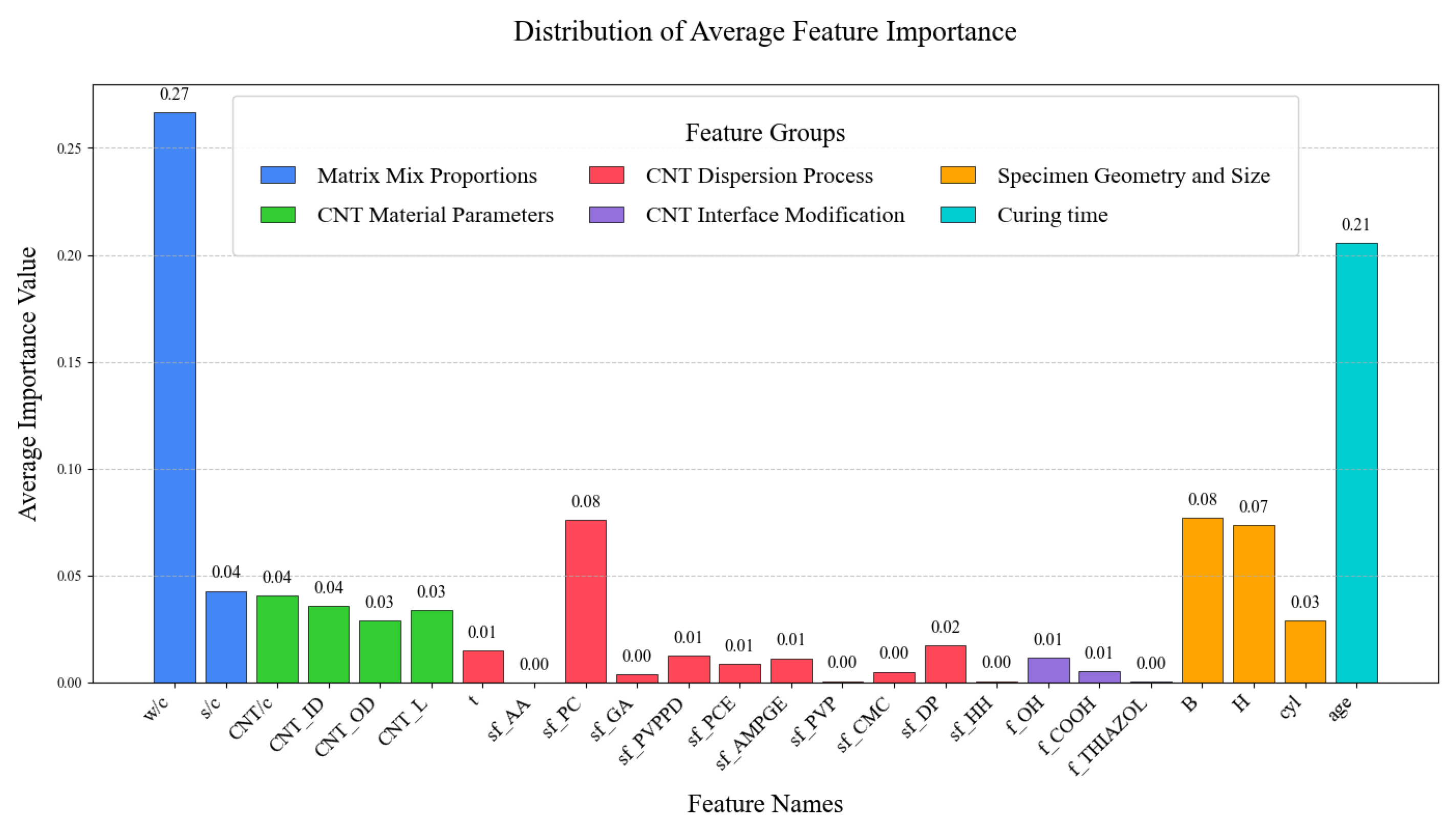

Figure 22 presents the distribution of the weighted average importance of all features across the different ML models. As shown in the figure, the feature importance for compressive strength in descending order is matrix mix proportions (weighted sum of 0.31), followed by curing time (0.21), then specimen geometry and size (0.18), CNT material parameters (0.14), CNT dispersion process (0.14), and, finally, CNT interface modification (0.02).

(1) Matrix mix proportions. Both the water–cement ratio and sand–cement ratio are key influencing factors, with the influence of w/c significantly greater than that of s/c.

(2) Curing time. Age is a major factor affecting the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete. Apart from the water–cement ratio, its proportion of importance is significantly higher than other features.

(3) Specimen geometry and size. The size and shape of the specimen have a significant impact on the compressive strength and are factors that cannot be ignored.

(4) CNT material parameters. Within this dimension, the mass percentage of CNT to cement and CNT inner diameter have the highest influence, followed by CNT length and CNT outer diameter. In contrast, studies by [

36,

40,

80] found that CNT length had a greater impact. This discrepancy might be because their data sample sizes were insufficient (less than 300), and they used fewer model algorithms. Additionally, references [

36,

80] did not deeply investigate the effects of the CNT inner diameter and outer diameter.

(5) CNT dispersion process. The effects of different treatment methods vary significantly. The effect of surfactant PC is the most prominent, followed by surfactant DP. The impacts of sonication duration, surfactant PVPPD, PCE, and AMPGE are minimal, while the effects of surfactant AA, GA, PVP, CMC, and HH are negligible.

(6) CNT interface modification. The effect of CNT functional group OH− is the most significant, followed by the functional group COOH− treatment. The impact of other modification methods is negligible.

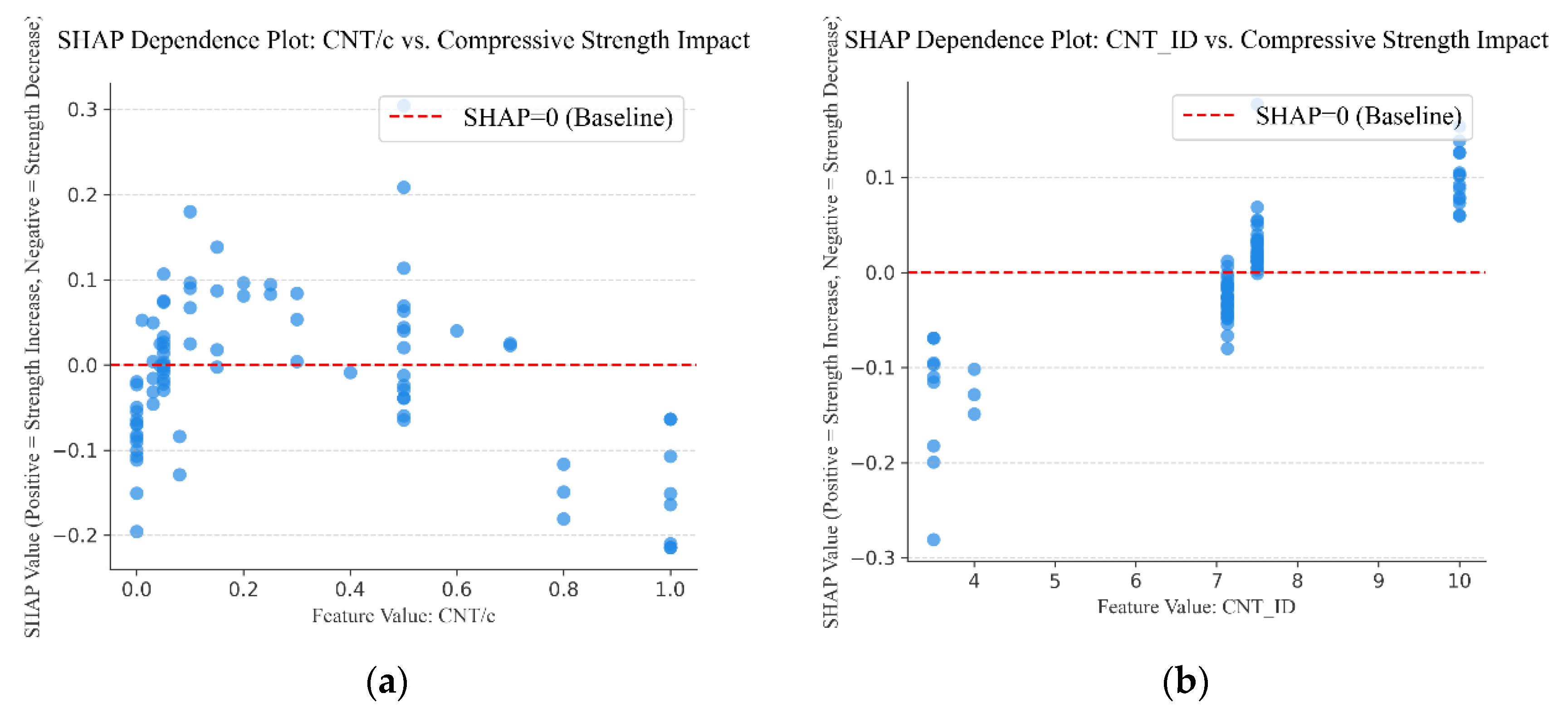

To specifically reveal the influence mechanism of CNT-related features on concrete compressive strength, key features such as the mass percentage of CNT to cement, CNT inner diameter, CNT outer diameter, CNT length, surfactant PC, and functional group OH

− were selected to create SHAP dependence plots, as shown in

Figure 23. In the plots, the red dashed line represents the baseline where the SHAP value is 0. SHAP values above and below the baseline indicate enhancing and reducing effects on concrete strength, respectively.

(1) The mass percentage of CNT to cement in the range of 0.1–0.3% can increase concrete compressive strength, whereas dosages that are too low or too high lead to a decrease in strength. However, Kumar et al. [

14] suggested that a mass percentage of CNT to cement up to 0.5% could enhance compressive strength. The SHAP dependence plot analysis shows that while some samples with CNT/c = 0.5% do exhibit a trend of increased strength, other samples experience a reduction in strength at the same dosage. Considering this variability, to reliably ensure a strength enhancement, this study conservatively suggests a mass percentage of CNT to cement within the 0.1–0.3% range.

(2) Compressive strength gradually increases with a larger CNT inner diameter, and the strength-enhancing effect is only observed when the inner diameter is no less than 7.132 nm. Strength tends to decrease as the CNT outer diameter increases. This is because, for a given mass, smaller-diameter CNTs possess a higher specific surface area, which provides a larger contact interface for bonding with the cement matrix and improves stress transfer [

81]. However, except for the extreme case of an 80 nm outer diameter, this feature generally has a positive effect on concrete strength, quantitatively capturing the trade-off between a high surface area and the practical challenges of dispersion [

82].

(3) For CNT length, the SHAP dependence plot shows that the commonly used length of around 25 μm actually reduces compressive strength, whereas the length within the 1–15 μm range consistently enhances strength. This is because while longer CNTs theoretically offer better crack-bridging, they are extremely difficult to disperse and tend to form strength-reducing agglomerates [

83]. These agglomerates act as defects in the cement matrix, causing a stress concentration that negates any potential reinforcement benefits.

(4) Surfactant PC can consistently enhance the compressive strength, whereas the OH

− functional group can significantly reduce the strength. This result is explained by the fact that PC acts as a highly effective superplasticizer, reducing the water–cement ratio and thus densifying the matrix [

84]. Conversely, the negative impact of the OH

− group, while seemingly counter-intuitive to the goal of improving dispersion, reveals a critical trade-off in practice. The aggressive chemical processes typically used to functionalize CNTs with OH

− groups (e.g., strong acid treatment) are known to cause significant structural damage to the nanotubes, creating defects that compromise their intrinsic mechanical properties [

85]. These damaged CNTs can then act as stress concentration points within the matrix. Therefore, our model’s findings suggest that, in many practical scenarios, the strength reduction caused by this structural damage may outweigh the potential benefits gained from the improved dispersion.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically compiled 429 sets of experimental data to construct a multi-dimensional database covering 11 core influencing factors, including matrix mix proportions, CNT material characteristics, CNT dispersion processes, CNT interface modifications, specimen geometry and size, and curing time. Based on this database, a systematic training, performance comparison, and evaluation of traditional statistical regression models (MLR, MPR, MARS), a mainstream classical model (SVR), and ensemble learning models (RF, XGB, LGBM) optimized with two hyperparameter tuning methods (PSO and BO) were conducted. The influence of key features on the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete was further analyzed. The conclusions are summarized as the following:

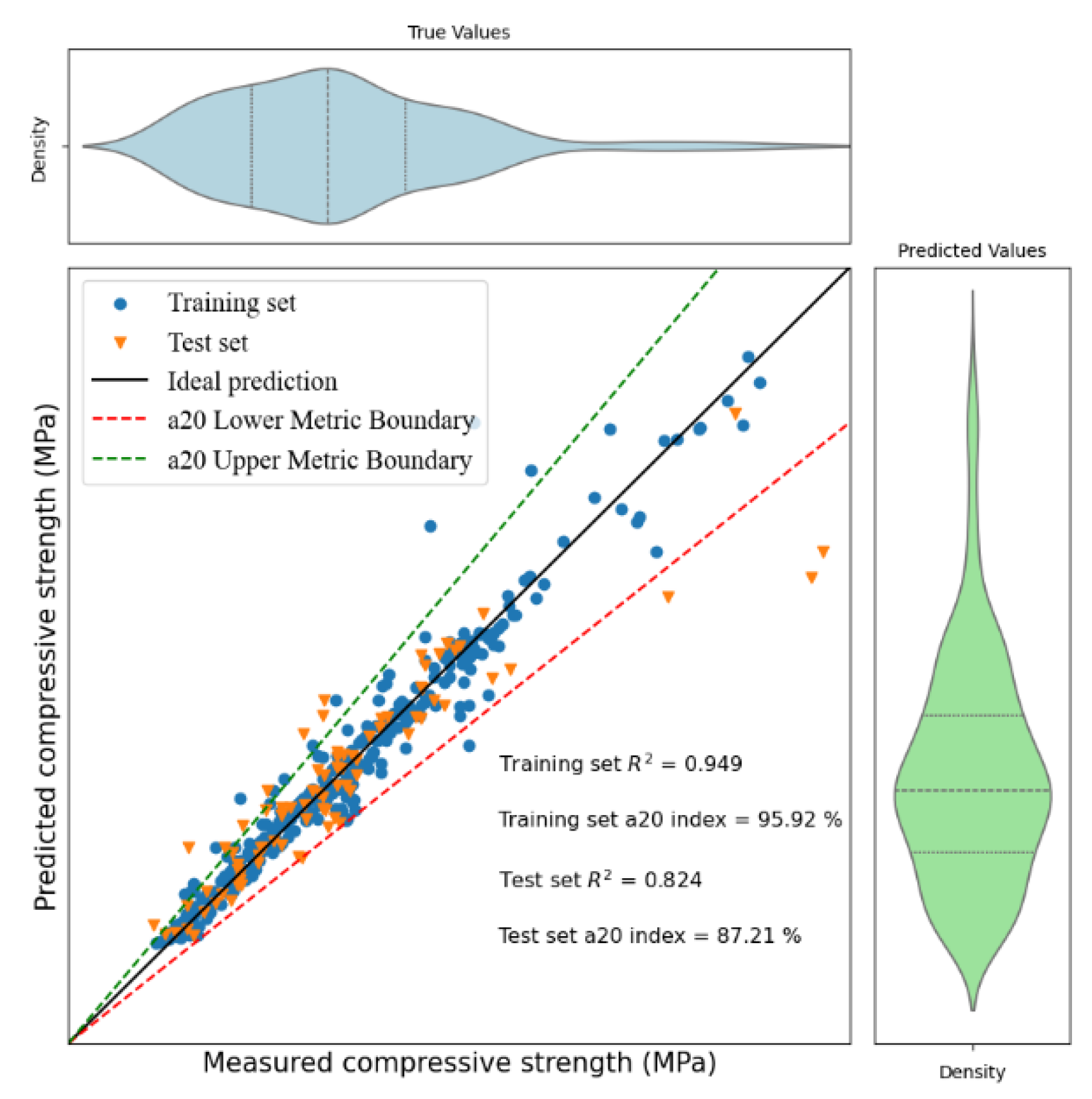

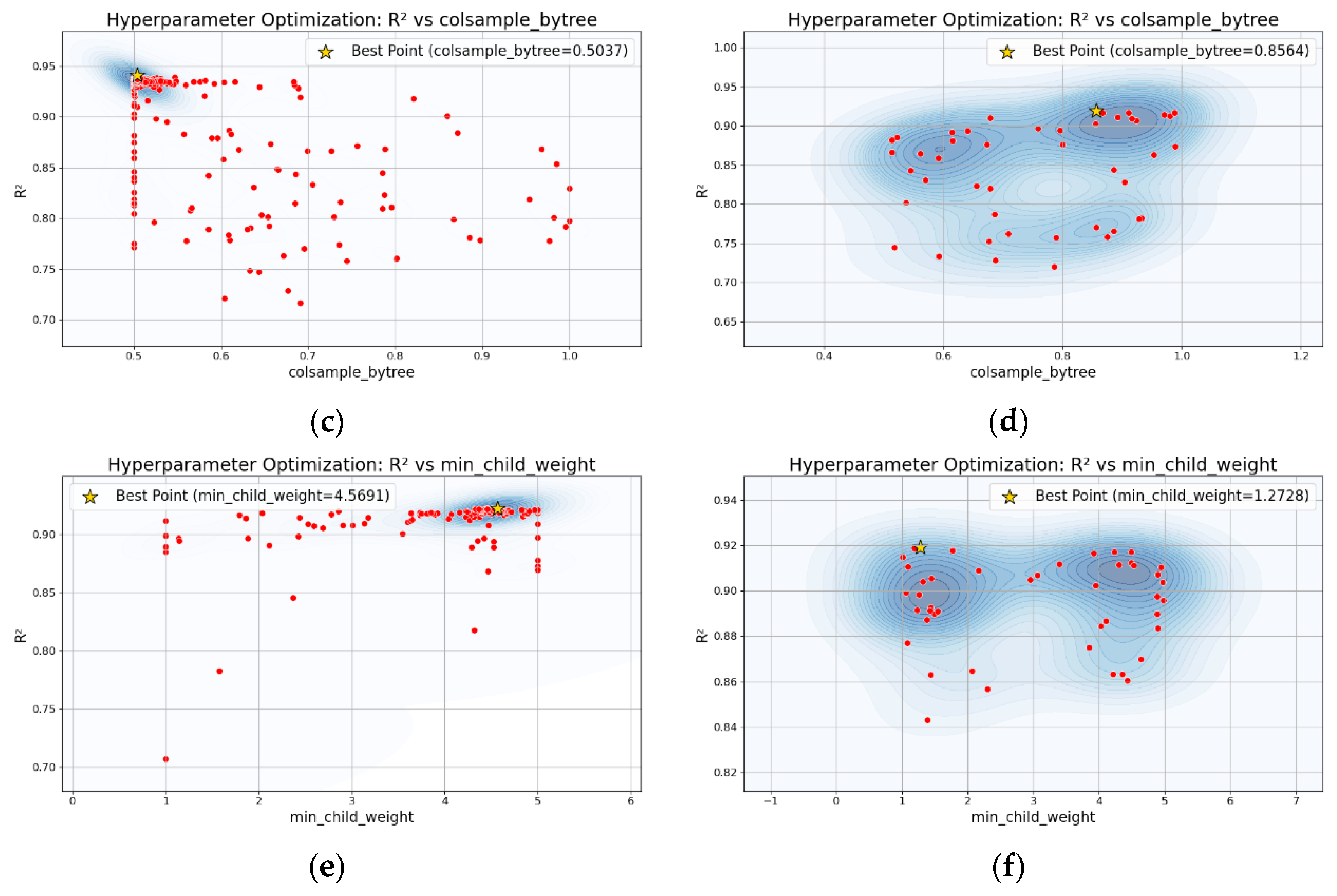

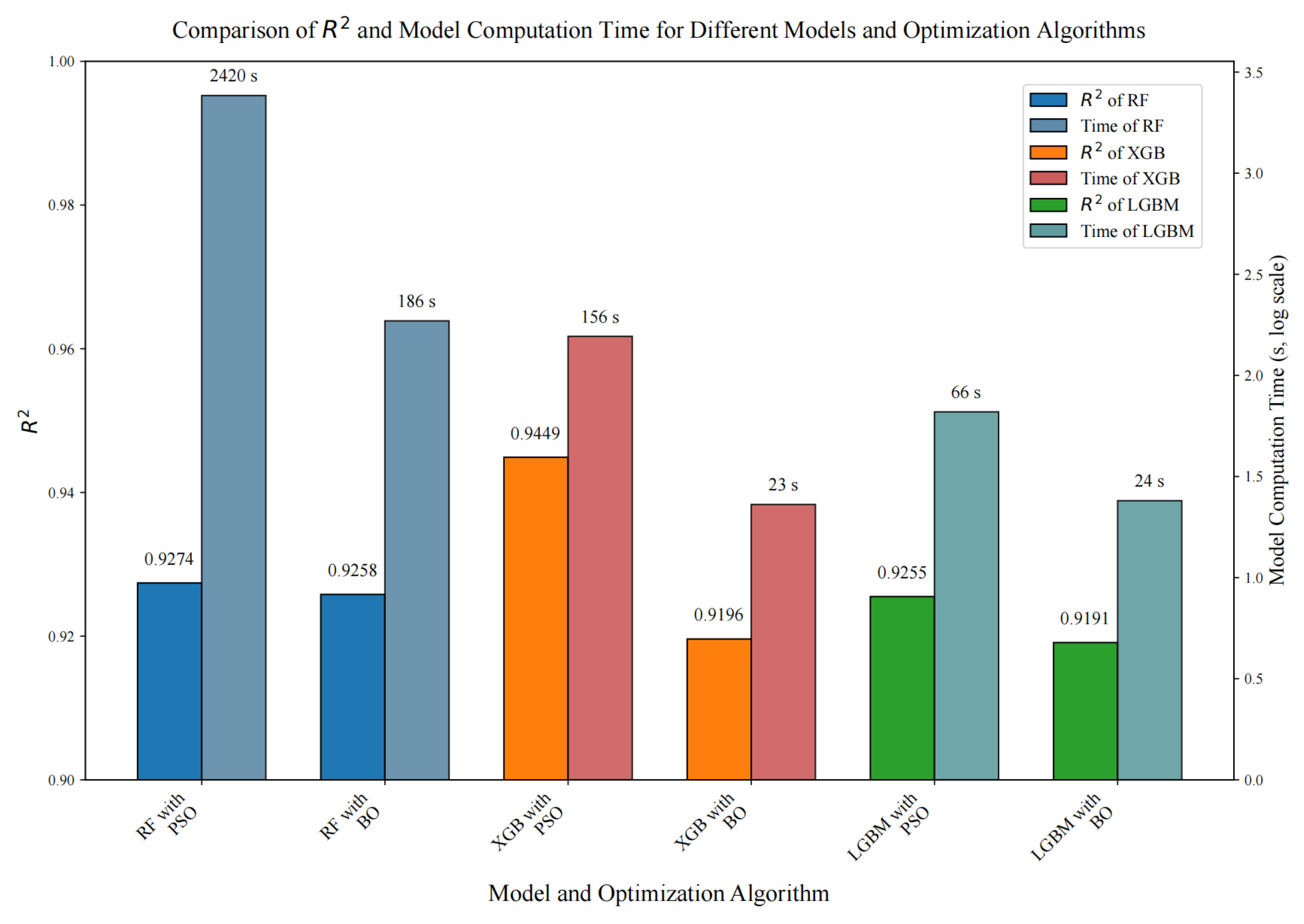

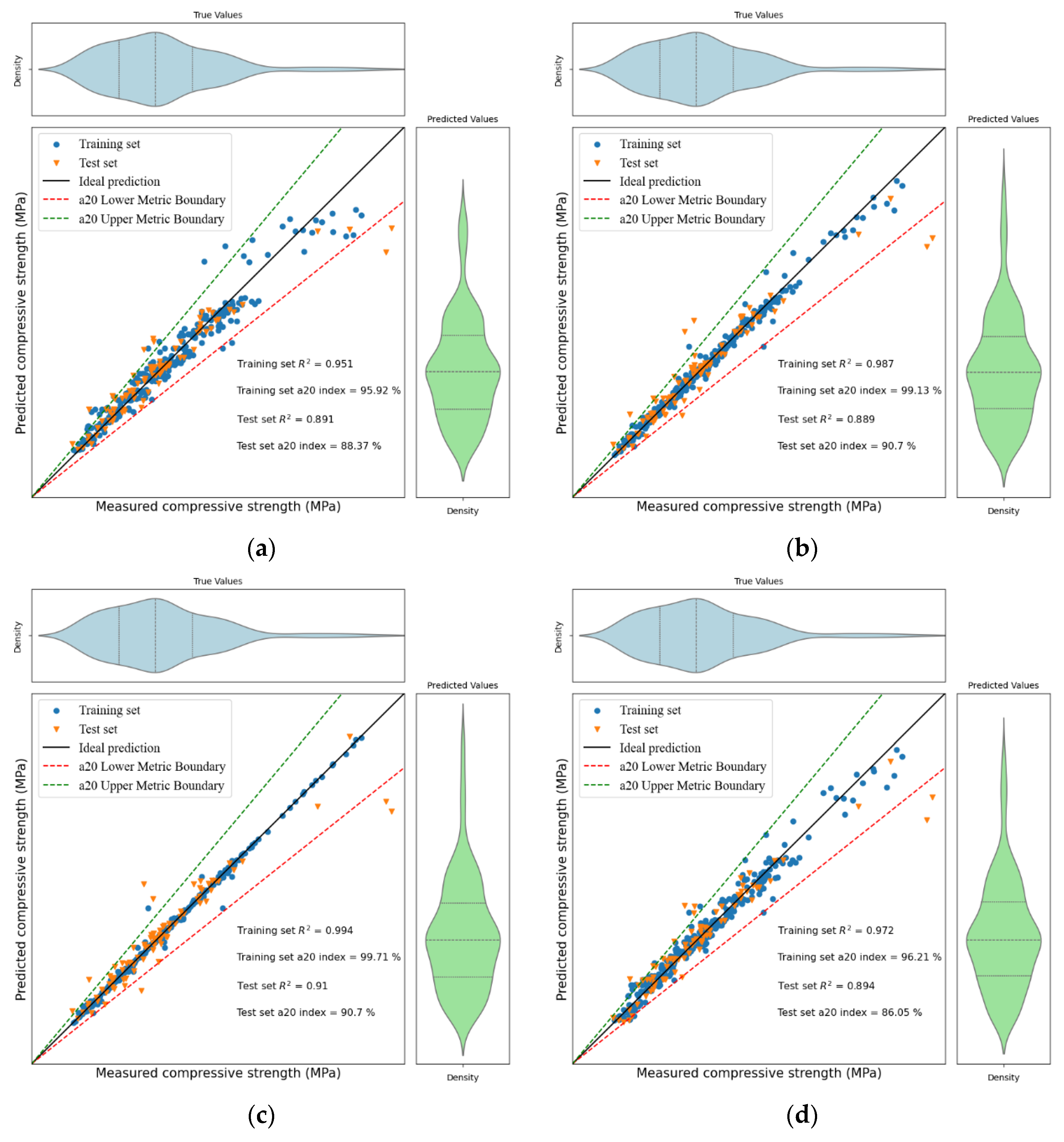

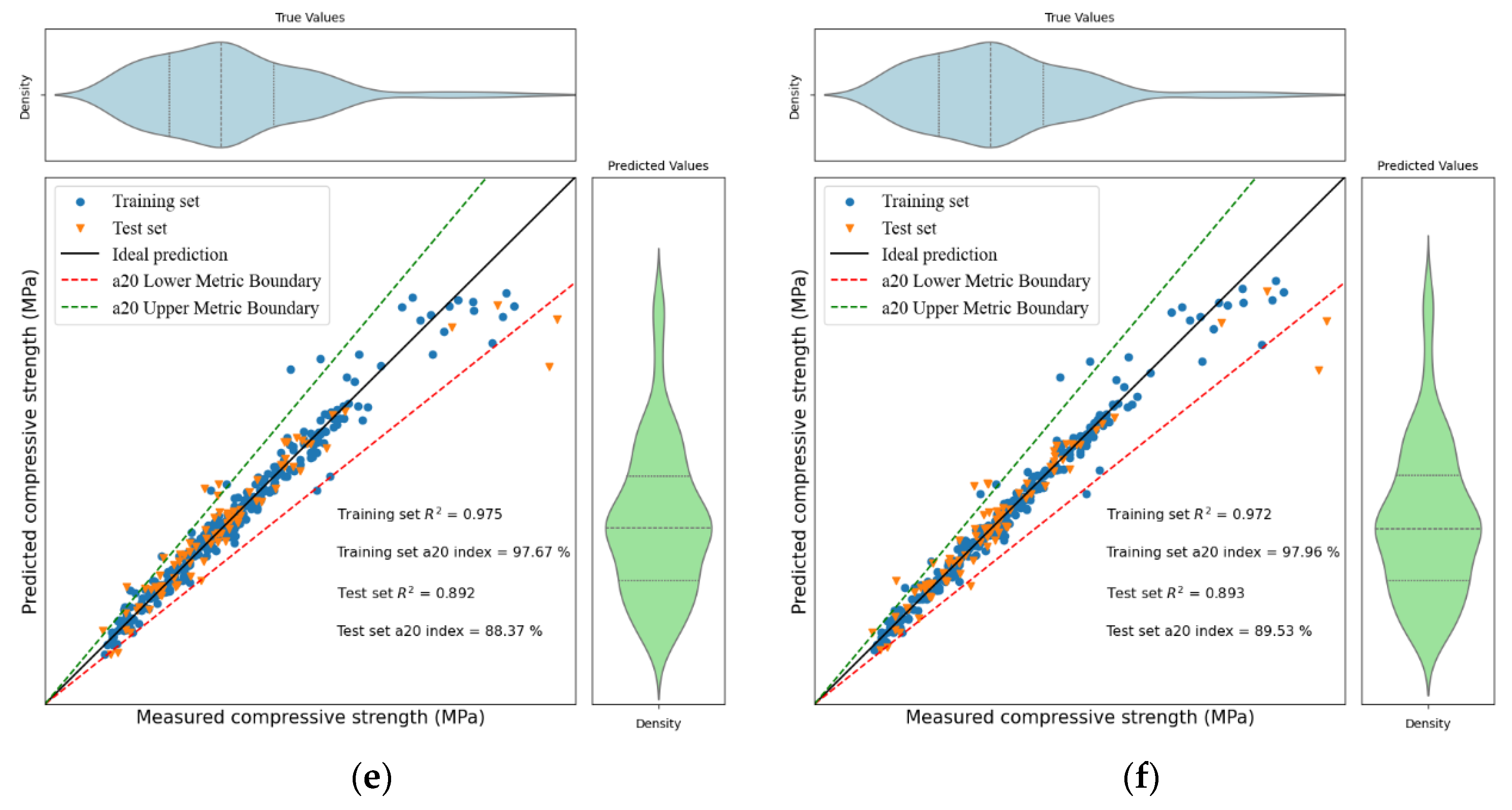

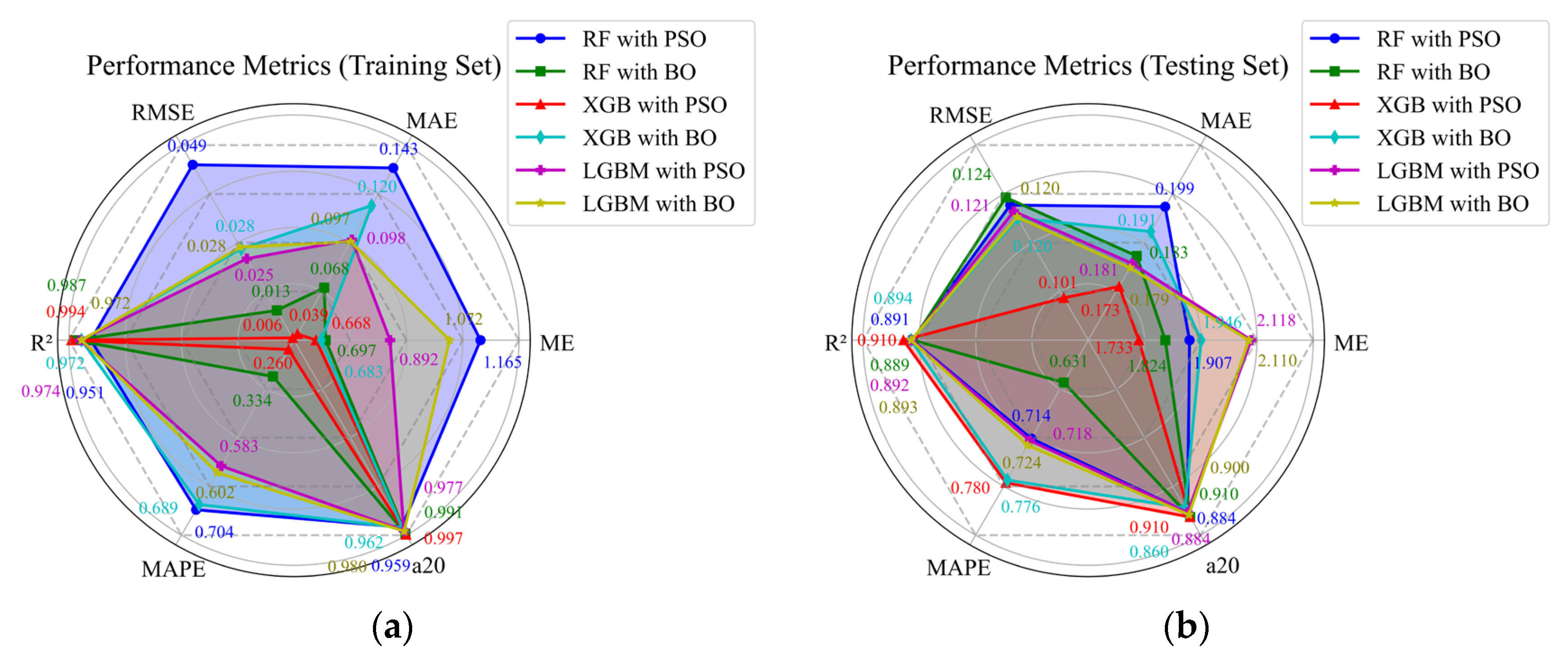

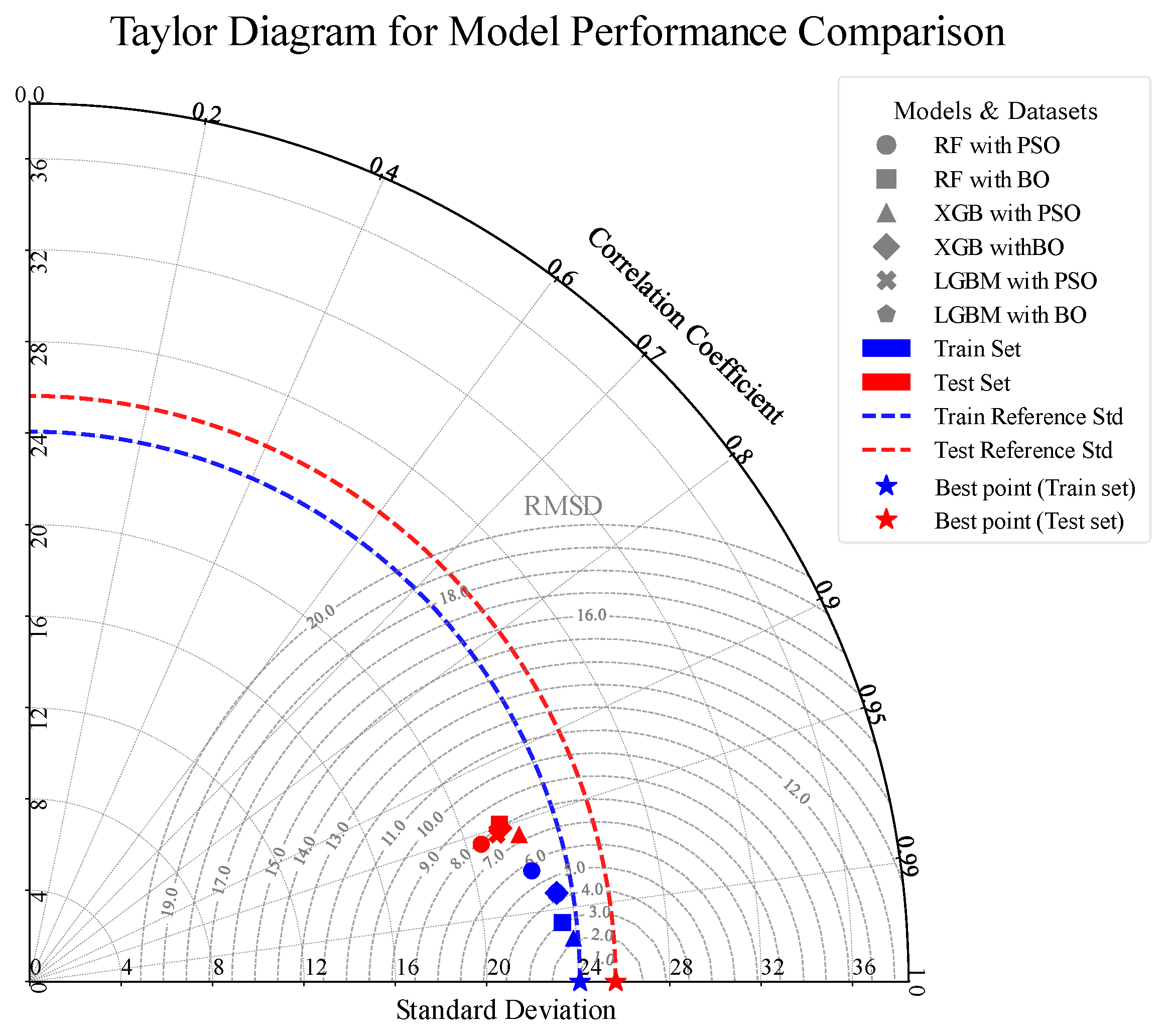

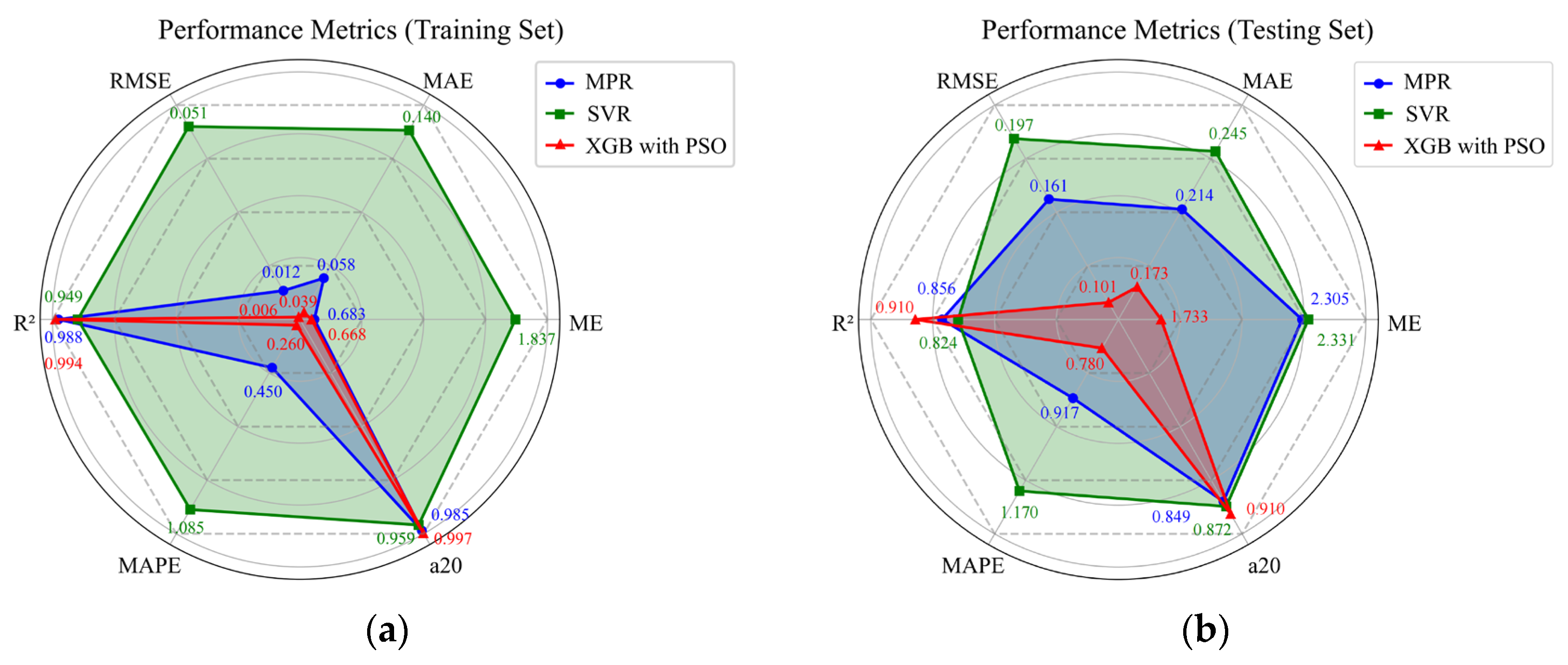

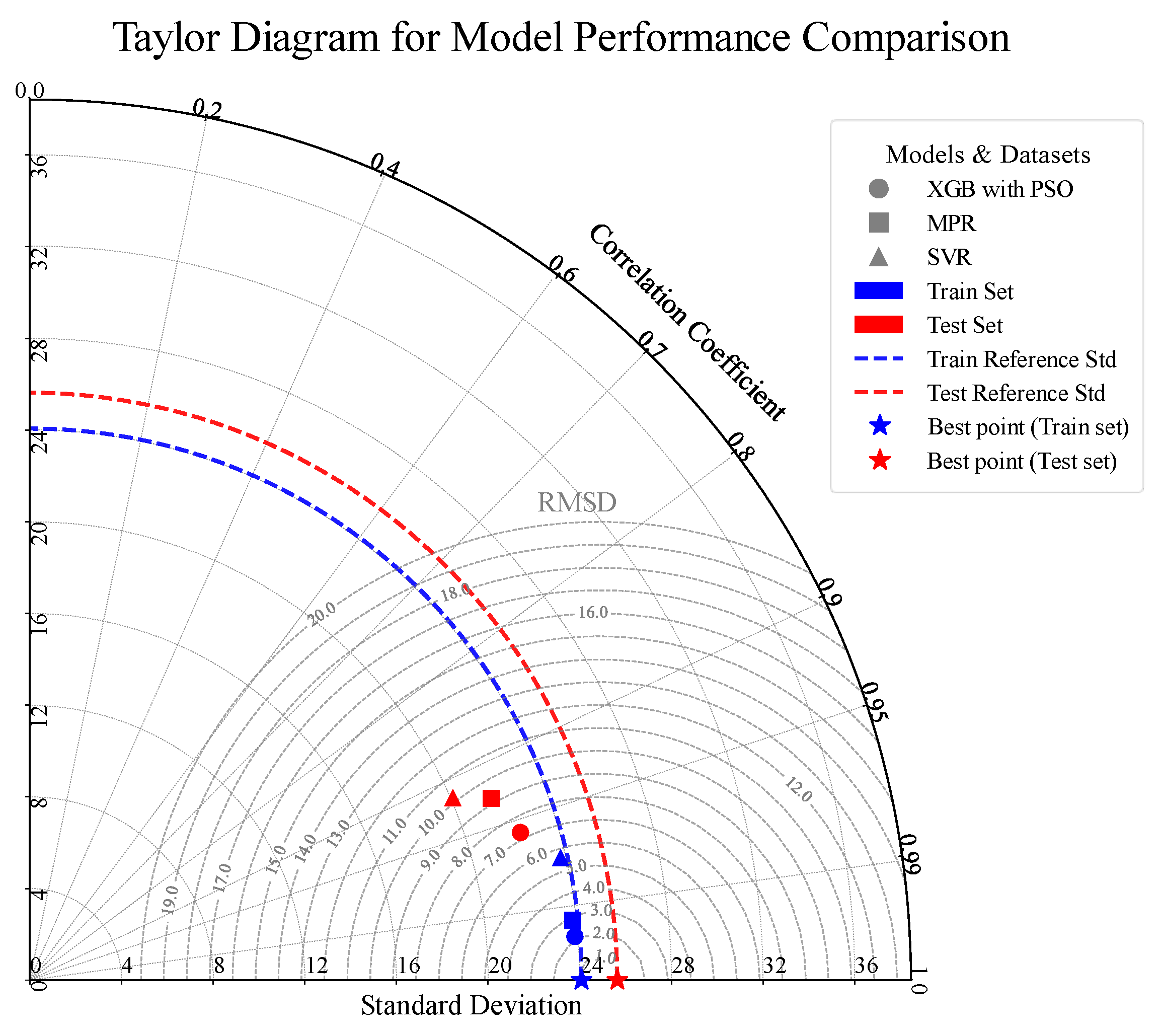

(1) This study successfully established a robust predictive framework for the compressive strength of CNT-reinforced concrete. The PSO-optimized XGB model demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy (test set R2 = 0.910). The investigation of hyperparameter optimization methods revealed that PSO achieves superior accuracy at a higher computational cost, while BO provides greater efficiency.

(2) While confirming the foundational impact of matrix mix proportions and curing age, this study’s primary contribution is the quantitative analysis of CNT-related parameters. Among these, CNT mass ratio and inner diameter were identified as the most critical factors influencing strength, with their importance surpassing that of CNT length and outer diameter. Furthermore, the dispersion process, particularly the use of PC surfactant, proved to be a more significant contributor than the CNT’s surface functional group.

(3) Guidelines for optimizing the use of CNTs in concrete are provided. To achieve strength enhancement, the results suggest an optimal CNT mass ratio of 0.1–0.3%, a length of 1–15 μm, and an inner diameter ≥ 7.132 nm. The use of PC surfactant is consistently beneficial, whereas OH− functionalization is shown to be detrimental to compressive strength.