Strain Energy-Based Calculation of Cracking Loads in Reinforced Concrete Members

Abstract

1. Introduction

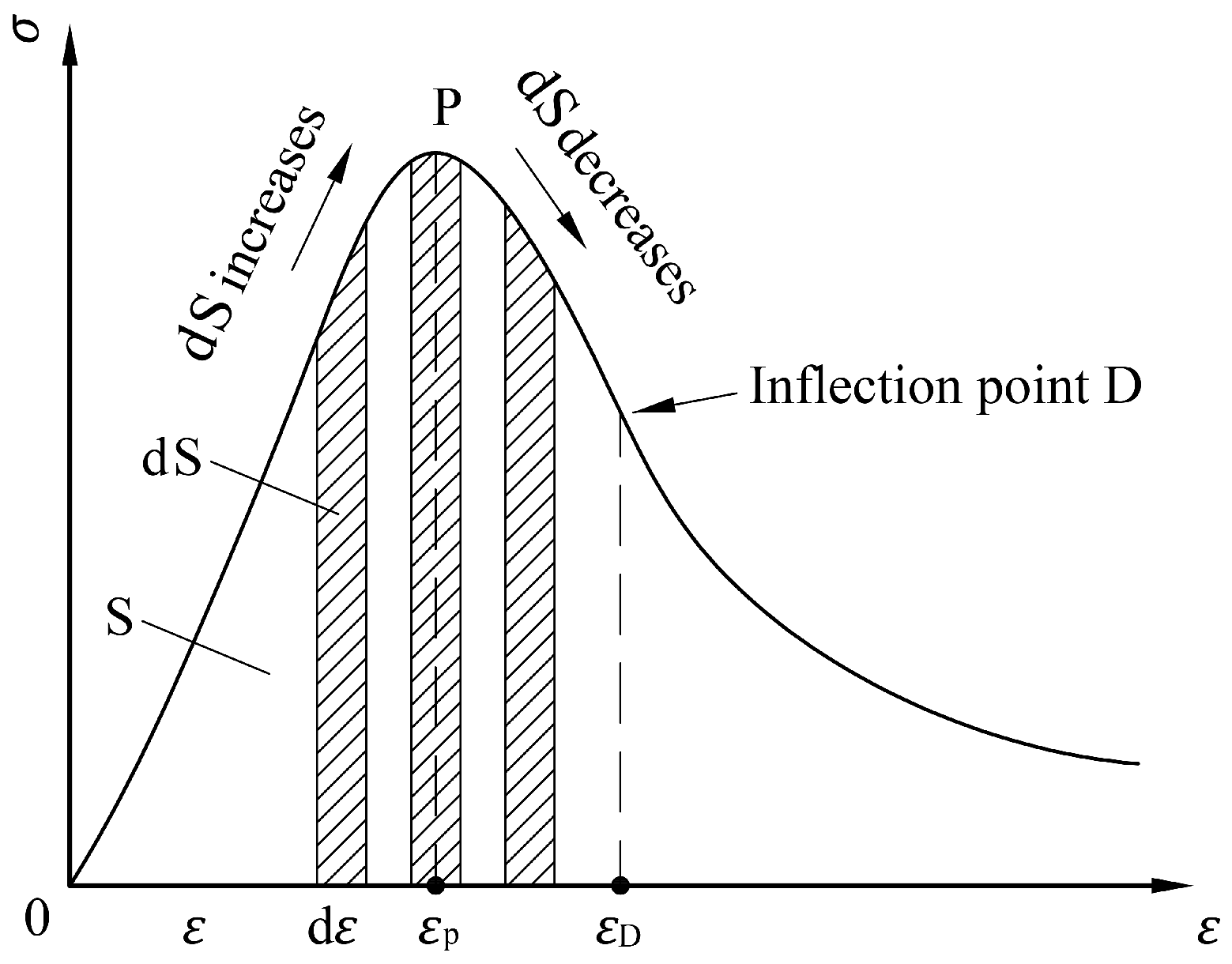

2. Characterizing Member Cracking Based on Strain Energy Increment

3. Cracking of Axially Tensioned Members of Steel-Reinforced Concrete

3.1. Case of Conventional Reinforcement Ratio

3.2. Case of High Reinforcement Ratio

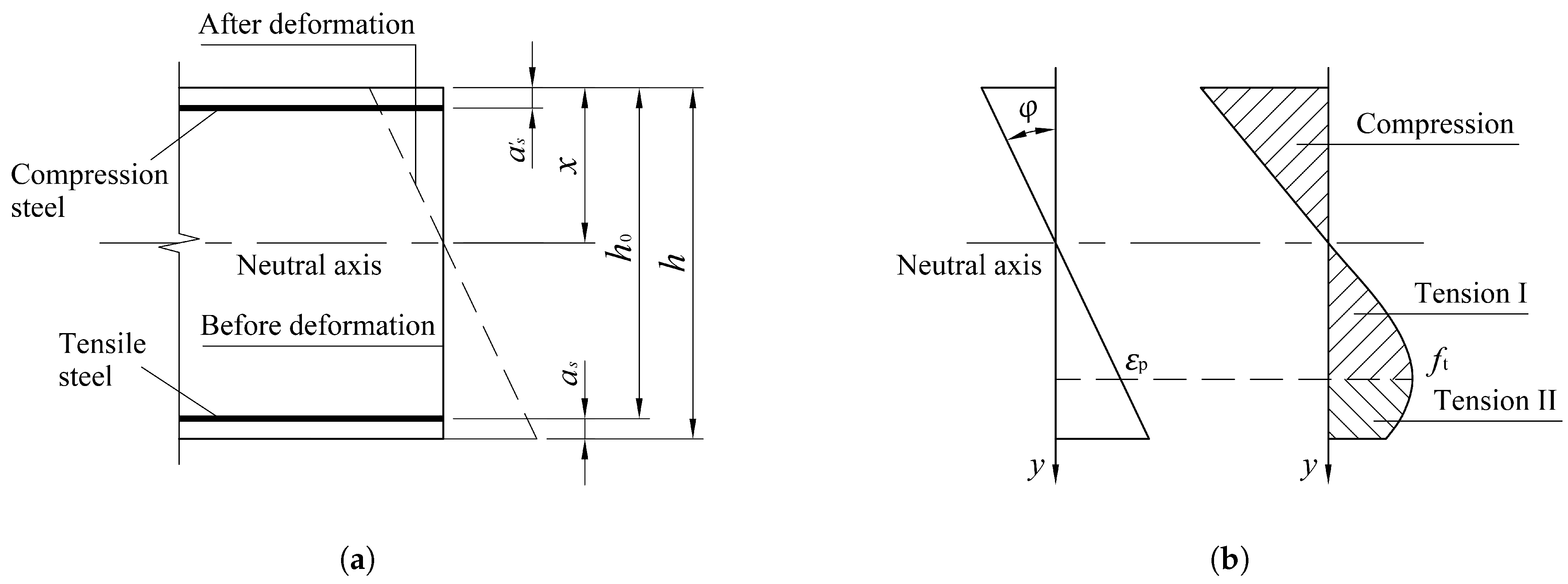

4. Cracking of Flexural Members of Steel- and FRP-Reinforced Concrete

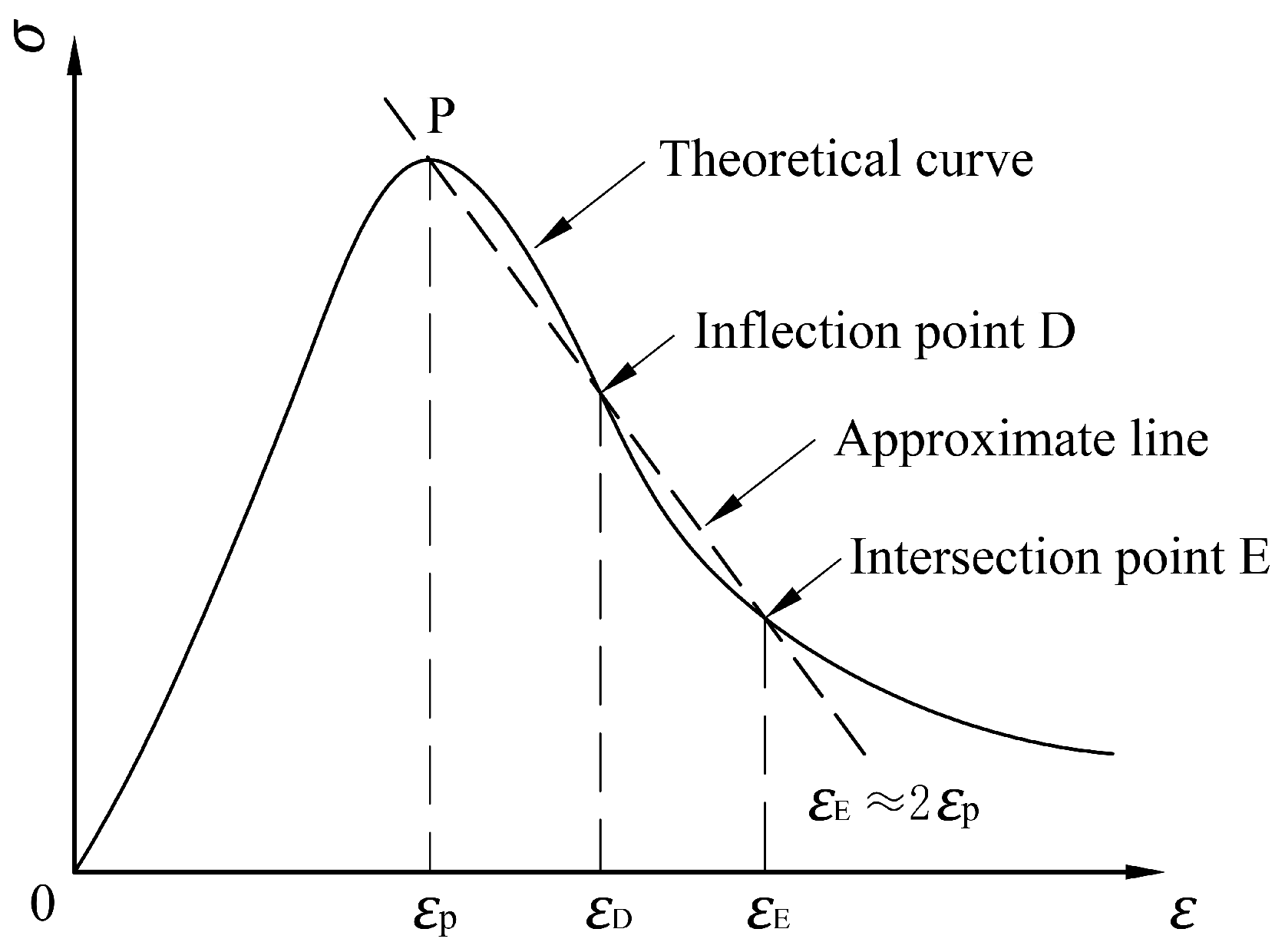

4.1. Energy-Based Criterion for Critical Cracking State

4.2. Model Validation with Experimental Results

4.2.1. Effect of Concrete Strength: Normal- to High-Strength

4.2.2. Effect of Concrete Strength: High-Strength

4.2.3. Effect of Reinforcement Ratio: Steel Reinforcement in High-Strength Concrete

4.2.4. Effect of Reinforcement Ratio: FRP Reinforcement in High-Strength Concrete

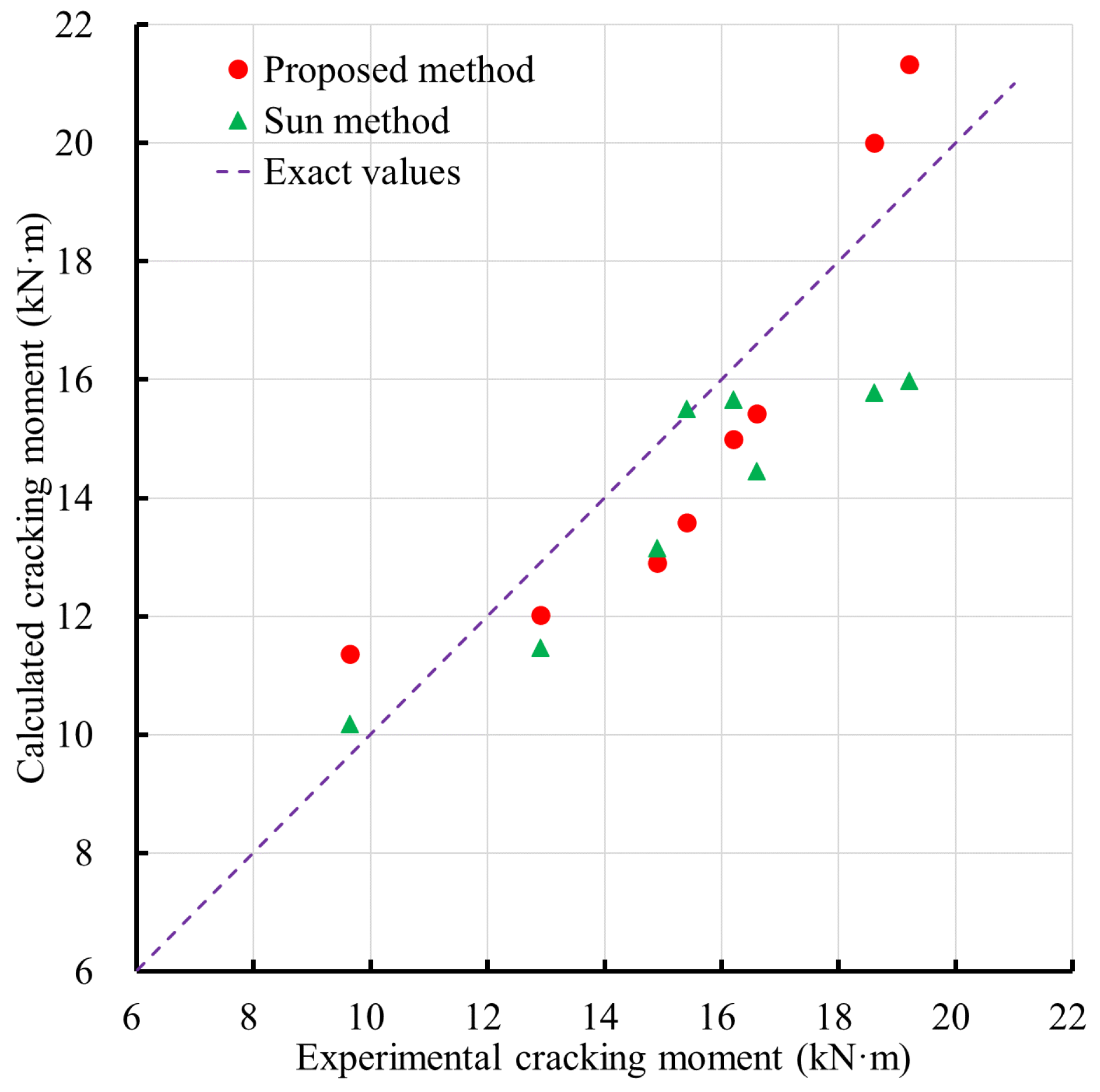

4.2.5. Discussion of Results

4.3. Model Assessment via Inelastic Deformation Analysis

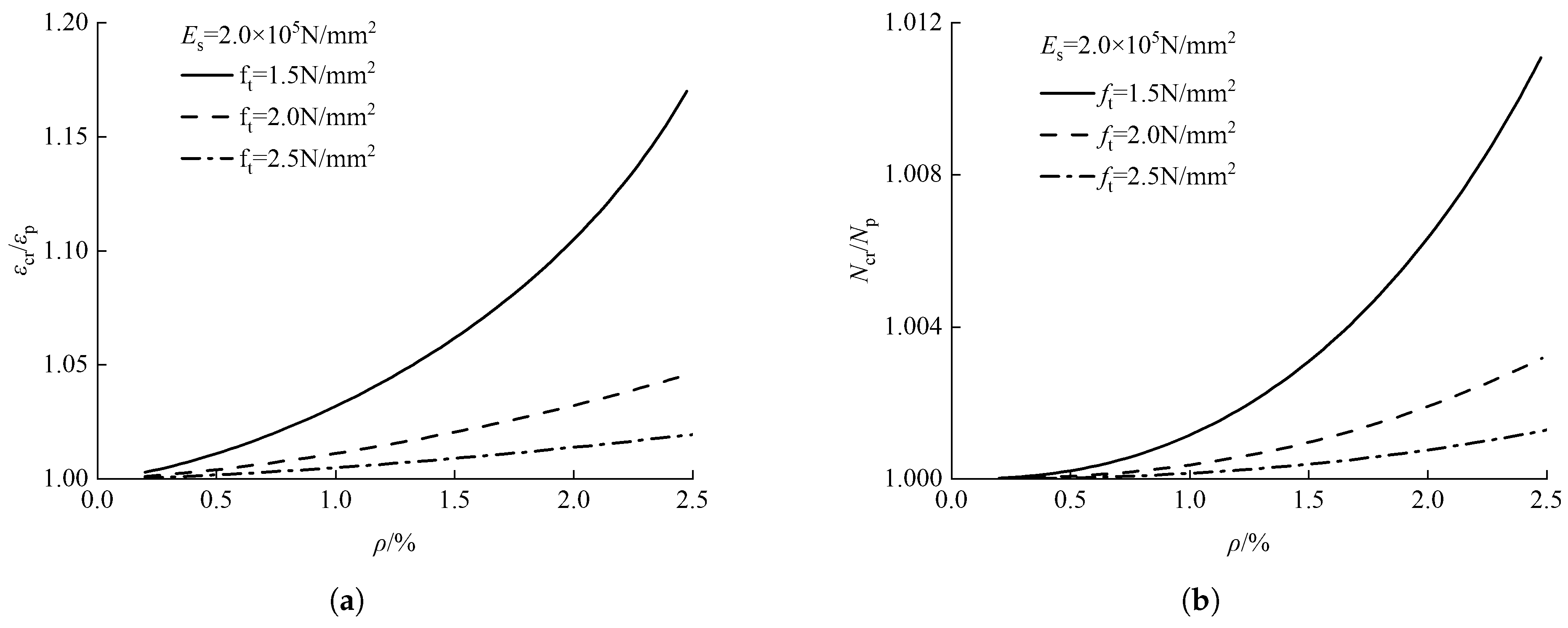

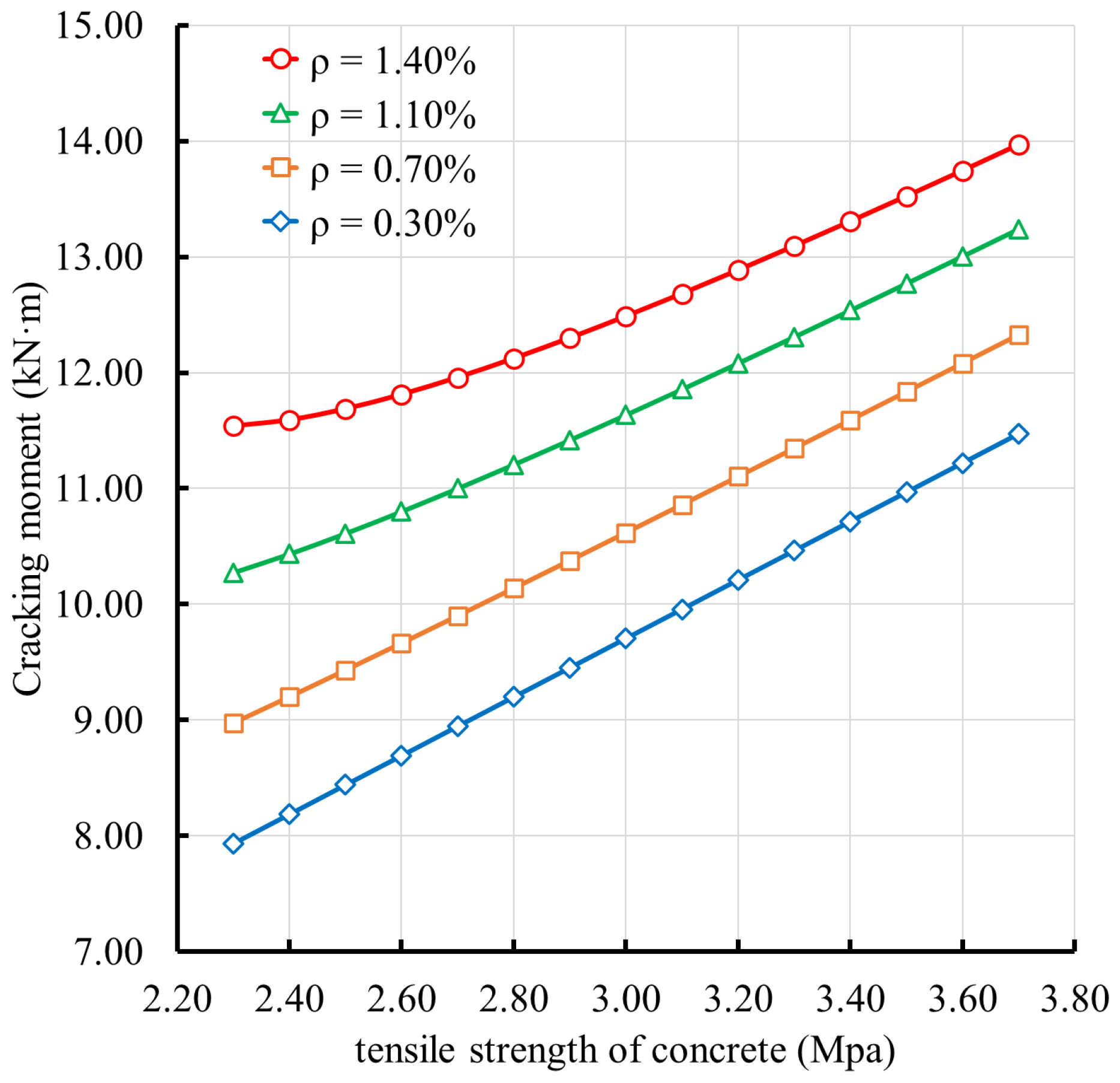

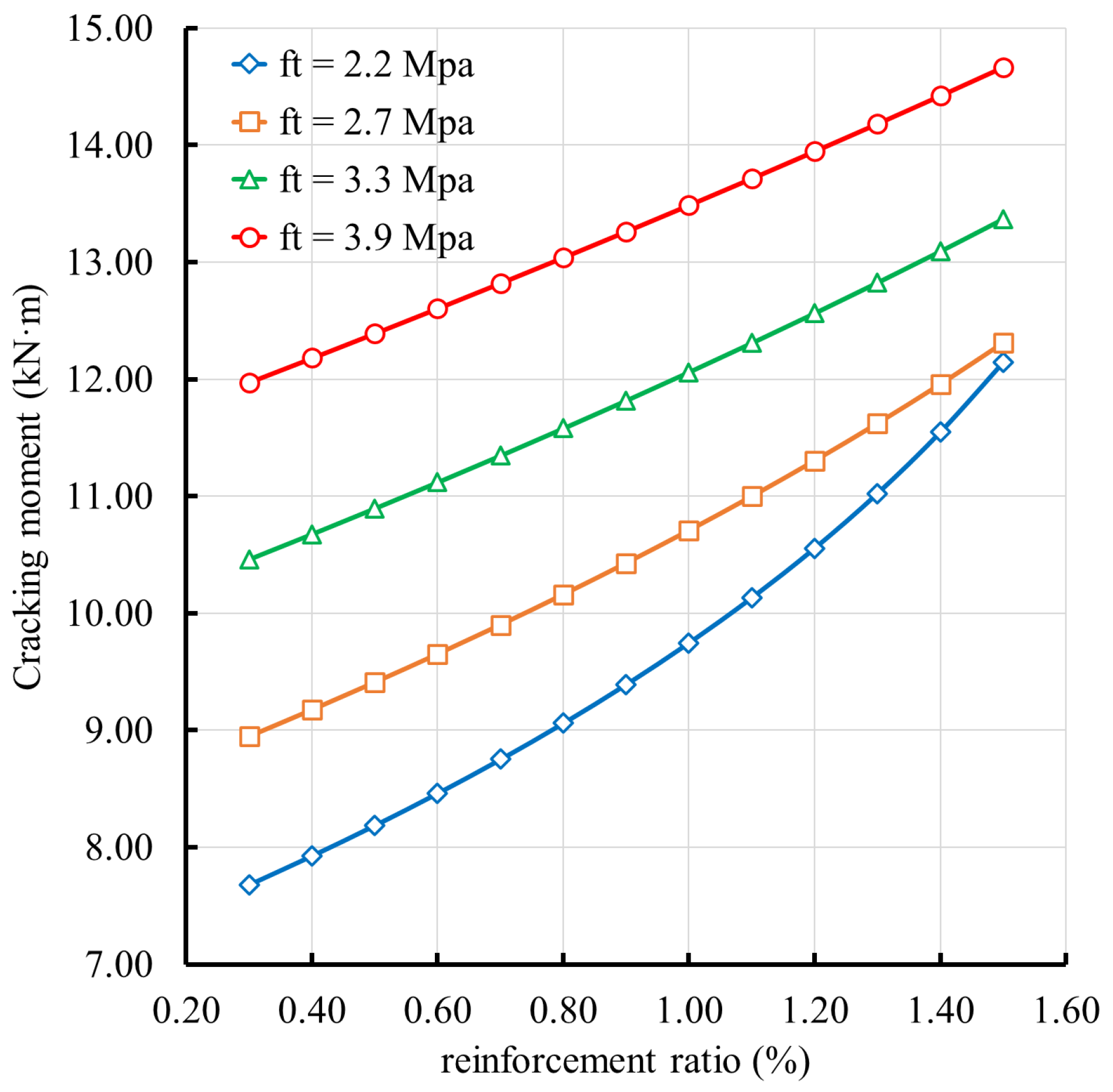

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Influencing Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, D.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q. Calculation method for crack resistance of steel fiber concrete deep beams with reinforcement. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2002, 33, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Du, C. Experimental study on cracking behavior of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams with BFRP bars under repeated loading. Compos. Struct. 2021, 267, 113878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Zhu, S.; Liu, S. Theoretical Study on Cracking Moment of Normal Section of Concrete Beams Reinforced with FRP Bars. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 5699–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z. Experimental analysis of recycled aggregate concrete beams and correction formulas for the crack resistance calculation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1466501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lu, S.; Li, L. Experimental research on mechanical performance of reactive powder concrete beams reinforced with GFRP bars. J. Build. Struct. 2011, 32, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Mechanical Behavior and Design Method for Reactive Powder Concrete Beams. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Zheng, W. Calculation method of normal section cracking resistance of GFRP reinforced reactive powder concrete beams. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2010, 42, 536–540. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Han, S.; Gang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Study on flexural capacity of recycled concrete beams with GFRP bars. Build. Struct. 2024, 54, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Saingam, P.; Chatveera, B.; Roopchalaem, J.; Hussain, Q.; Ejaz, A.; Khaliq, W.; Makul, N.; Chaimahawan, P.; Sua-iam, G. Influence of recycled electronic waste fiber on the mechanical and durability characteristics of eco-friendly self-consolidating mortar incorporating recycled glass aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, G. A double-K fracture criterion for crack propagation in concrete structures. China Civ. Eng. J. 1992, 25, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, Y. Analysis and criterion of fracture process for crack propagation in concrete. Eng. Mech. 2008, 25, 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, S.; Wu, Z. A dual-G criterion for crack propagation in concrete structures. China Civ. Eng. J. 2004, 37, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, X. The new GR crack extension resistance as a fracture criterion for complete crack propagation in concrete structures. China Civil Eng. J. 2006, 39, 19–28+41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G. A new method for calculating crack resistance of hydraulic reinforced concrete with few bars and concrete structures. J. Dalian Inst. Technol. 1959, 4, 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G. General calculation method for crack resistance of prestressed concrete, reinforced concrete and concrete members. J. Civ. Eng. 1964, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W. Experimental study on crack resistance, stiffness and crack width of reinforced concrete rectangular section eccentric tensile member. J. Nanjing Inst. Technol. 1981, 3, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G. Calculation method for crack resistance (crack initiation and propagation) of hydraulic reinforced concrete structures. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1960, 5, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- EN1992-1-1; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures. British Cement Association: London, UK, 1994.

- ACI 318M-2014; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2014.

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, X. Experimental study of the stress-deformation curve of tensile concrete. J. Build. Struct. 1988, 4, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Shi, X. Principles and Analysis of Reinforced Concrete; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, J.S.; Smith, G.M.; Young, L.E. Stress distribution affects ultimate tensile strength. J. Proc. 1958, 55, 679–684. [Google Scholar]

- CH10-57; Chinese Translation of Soviet Code for Design of Prestressed Reinforced Concrete Structures. Architectural Engineering Press: Beijing, China, 1957.

- Cai, S. Problem on the value of flexural and tensile cracking plasticity coefficient γs of concrete. Concr. Reinf. Concr. 1982, 4, 23–27+50. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; He, X. Preliminary analysis of volume (size) effect and anti-crack plastic coefficient γ value of concrete members. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 1986, 22, 364–368. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Fan, X.; Shi, X. Experimental study on flexural behavior of large-scale prestressed UHPC-T-shaped beam. China Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 51, 84–94+102. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Hu, S.; Du, R. A calculation method for cracking moment of prestressed reactive powder concrete box girder. China Civil Eng. J. 2015, 48, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Deng, J.; Gao, S. Study on the Applicable Calculation Method of the Cracking Moment of UHPC Beam. J. China Three Gorges Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 45, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Ji, B.; Xia, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhao, J. Crack resistance of prestressed RC-UHPC composite box girder. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2025, 47, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Talpur, S.; Thansirichaisree, P.; Poovarodom, N.; Mohamad, H.; Zhou, M.; Ejaz, A.; Hussain, Q.; Saingam, P. Machine learning approach to predict the strength of concrete confined with sustainable natural FRP composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 14, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.L.; Wang, W.H.; Hou, X.L.; Xie, C.X.; Lu, C.F. Prediction of the Shear Cracking Strength of RC Deep Beams Based on the Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. J. Xinjiang Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 40, 621–629. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.H.; Ying, Z.Q.; Liu, M.M.; Yang, S. Prediction Method for Reinforced Concrete Corrosion-induced Crack Based on Stacking Integrated Model Fusion. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2024, 44, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, G. Comparative analysis of different calculation methods of cracking bending moment of reinforced concrete beams. J. China Three Gorges Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 38, 54–58+69. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, P. An improved formula for cracking moment calculation of RC beams considering the development coefficient of plastic deformations. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2019, 36, 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Liang, S.; Chen, D.; Lu, J.; Jiang, N. Experimental study on the deformation properties of high-strength reinforced high-strength concrete flexural components. J. Build. Struct. 1998, 19, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. Experimental Research on Cracking Moment of Reactive Powder Concrete Beams with High Strength Steel Bars. Railw. Constr. 2021, 61, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50152-2012; Standard for Test Methods for Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Yuan, J.; Yu, Z. Design Principle of Concrete Structure; China Railway Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

( ) | () | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | |

| 2.0 | 1.32 | 2.95 | 5.14 | 7.81 | 10.87 |

| 2.1 | 1.26 | 2.82 | 4.91 | 7.46 | 10.40 |

() | () | () | () | () | () | () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 179 × 207 | 171 | 226 | 201.1 | 7.88 | 7.71 | 8.38 | 0.98 | 1.06 |

| 181 × 213 | 177 | 339 | 201.1 | 8.51 | 8.59 | 9.15 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

| 180 × 205 | 169 | 452 | 201.1 | 8.19 | 8.25 | 8.59 | 1.01 | 1.05 |

| 182 × 208 | 172 | 226 | 201.1 | 7.68 | 7.91 | 8.60 | 1.03 | 1.12 |

| 179 × 212 | 176 | 339 | 201.1 | 9.75 | 8.42 | 8.97 | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| 181 × 209 | 173 | 452 | 201.1 | 9.40 | 8.61 | 8.97 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| 181 × 209 | 173 | 226 | 201.1 | 8.51 | 7.94 | 8.64 | 0.93 | 1.02 |

| 181 × 214 | 178 | 339 | 201.1 | 9.04 | 8.67 | 9.23 | 0.96 | 1.02 |

| 179 × 207 | 171 | 452 | 201.1 | 8.59 | 8.37 | 8.71 | 0.97 | 1.01 |

| 180 × 208 | 172 | 226 | 199.1 | 8.49 | 7.82 | 8.51 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

| 179 × 211 | 175 | 452 | 199.1 | 8.70 | 8.67 | 9.05 | 1.00 | 1.04 |

() | () | () | () | () | () | () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150 × 280 | 249 | 226 | 47.6 | 24.00 | 24.12 | 22.91 | 1.00 | 0.95 |

| 150 × 280 | 230.5 | 452 | 47.6 | 24.00 | 24.30 | 23.85 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| 150 × 280 | 230.5 | 565 | 47.6 | 24.00 | 24.44 | 24.33 | 1.02 | 1.01 |

| 150 × 280 | 230.5 | 678 | 47.6 | 27.00 | 24.58 | 24.81 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| 150 × 280 | 228.5 | 769 | 50.0 | 27.00 | 24.70 | 25.22 | 0.91 | 0.93 |

| 150 × 280 | 228.5 | 923 | 50.0 | 27.00 | 24.89 | 25.89 | 0.92 | 0.96 |

| (C20∼C30) | (C30∼C50) | (C50∼C80) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.1 | |

| 1.40% | 8.82 | 4.96 | 3.62 | 3.24 | 2.95 | 2.73 | 2.55 | 2.40 | 2.28 | 2.17 | 2.08 | 2.00 | 1.94 | 1.88 | 1.78 | 1.69 | 1.63 |

| 1.13% | 4.95 | 3.60 | 2.93 | 2.71 | 2.53 | 2.39 | 2.27 | 2.16 | 2.08 | 2.00 | 1.93 | 1.87 | 1.82 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.62 | 1.57 |

| 0.89% | 3.59 | 2.92 | 2.53 | 2.38 | 2.26 | 2.16 | 2.07 | 2.00 | 1.93 | 1.87 | 1.82 | 1.77 | 1.73 | 1.69 | 1.62 | 1.57 | 1.52 |

| 0.50% | 2.55 | 2.28 | 2.09 | 2.01 | 1.94 | 1.88 | 1.83 | 1.78 | 1.74 | 1.70 | 1.66 | 1.63 | 1.60 | 1.57 | 1.53 | 1.48 | 1.45 |

| 0.35% | 2.31 | 2.11 | 1.96 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 1.71 | 1.68 | 1.64 | 1.61 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, T.; Wang, G.-Y. Strain Energy-Based Calculation of Cracking Loads in Reinforced Concrete Members. Buildings 2025, 15, 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234315

Zheng T, Wang G-Y. Strain Energy-Based Calculation of Cracking Loads in Reinforced Concrete Members. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234315

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Tao, and Gui-Yao Wang. 2025. "Strain Energy-Based Calculation of Cracking Loads in Reinforced Concrete Members" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234315

APA StyleZheng, T., & Wang, G.-Y. (2025). Strain Energy-Based Calculation of Cracking Loads in Reinforced Concrete Members. Buildings, 15(23), 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234315