The Impact of Composite Alkali Activator on the Mechanical Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms in Aeolian Sand Powder–Aeolian Sand Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

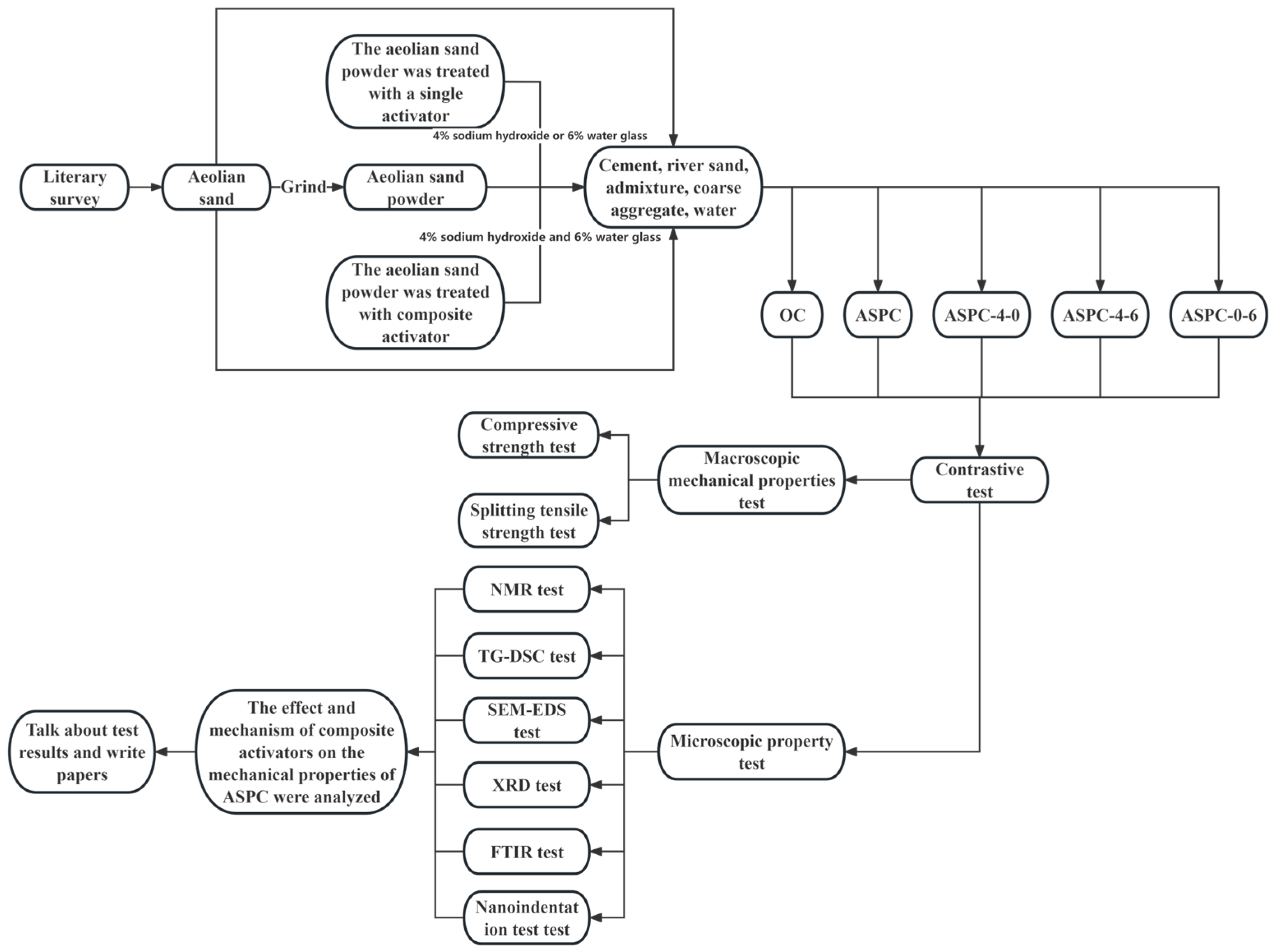

2. Materials and Methods

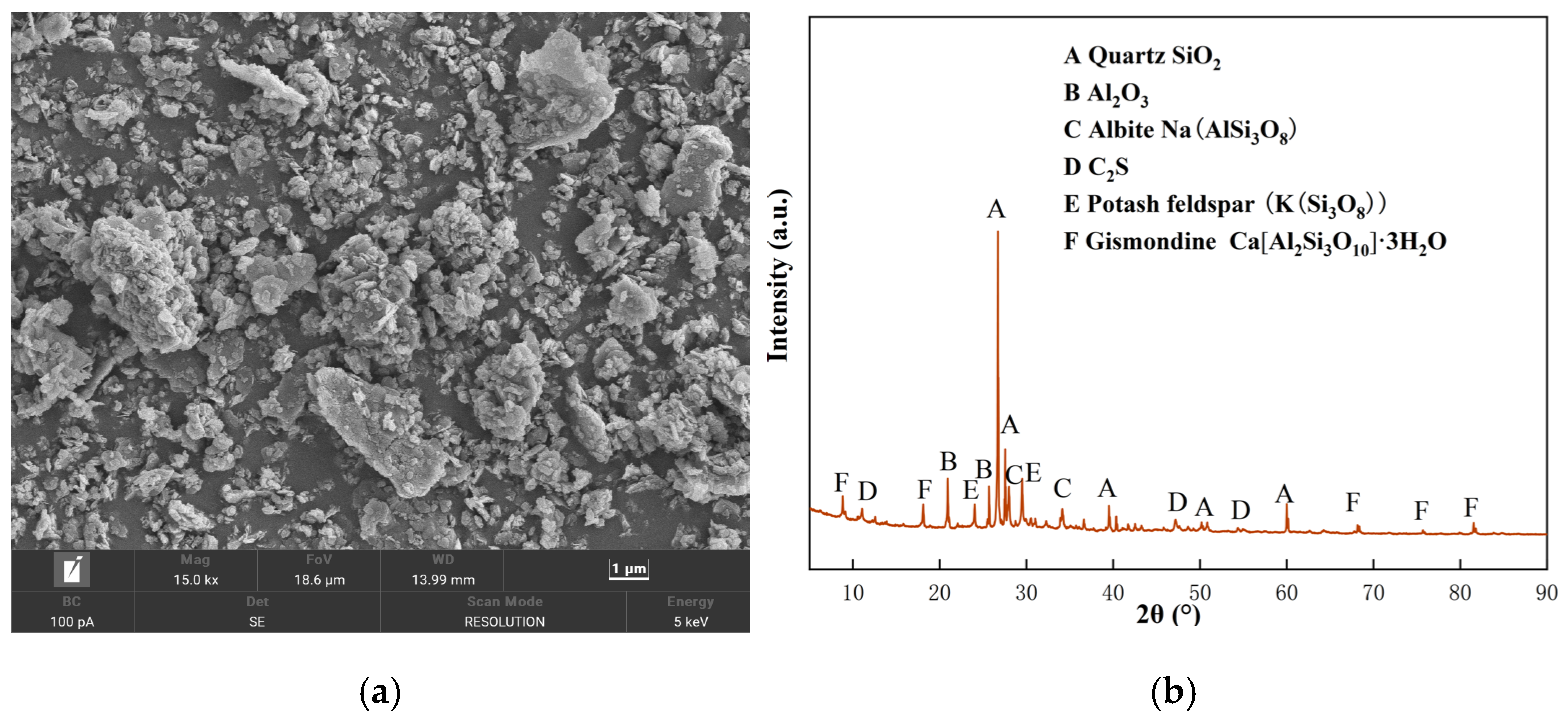

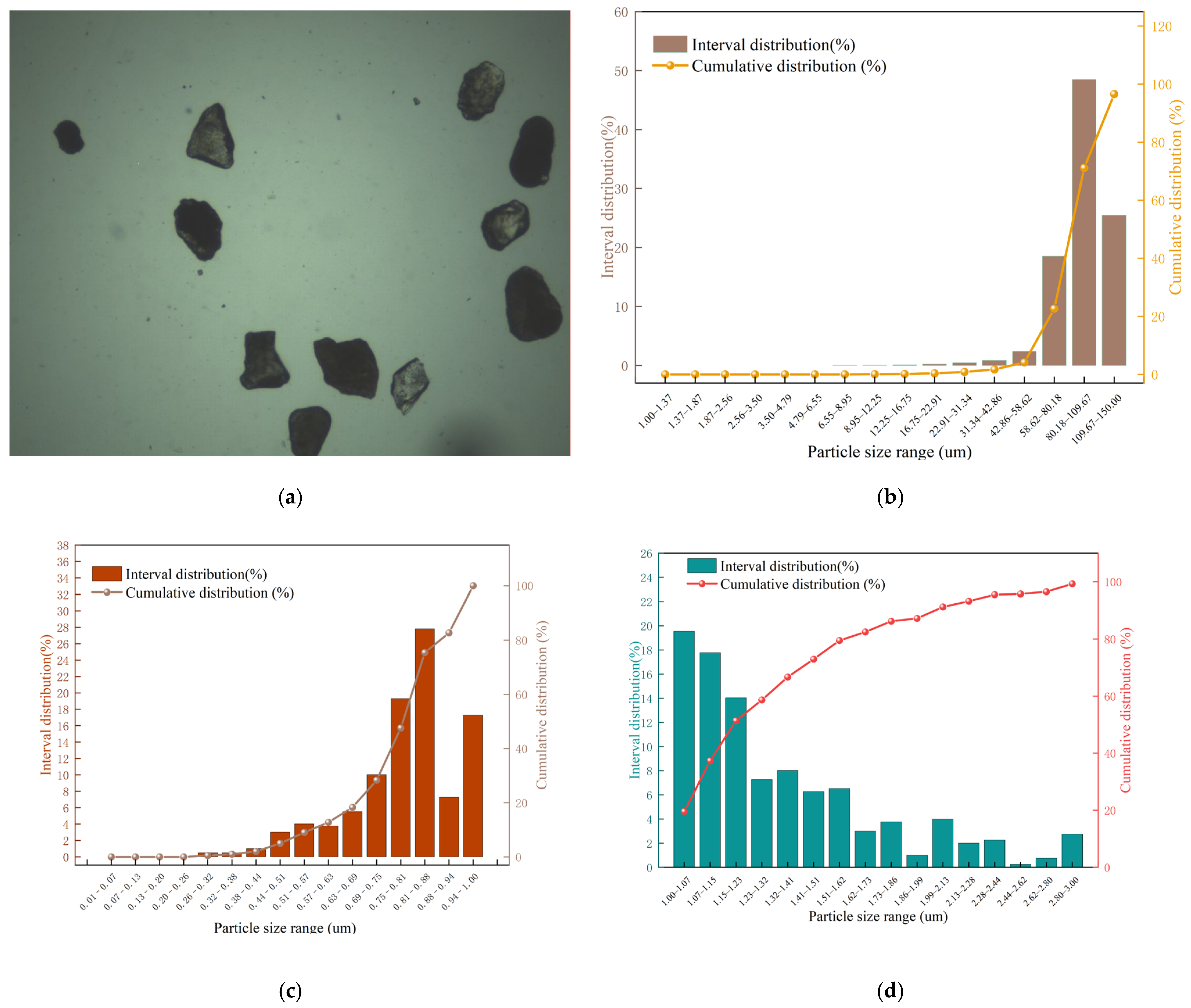

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Ratio Design

2.3. Evaluation of the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of ASPC

2.3.1. Mechanical Properties of ASPC

2.3.2. Microstructural Characterization of ASPC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Complex Activator on the Mechanical Properties of ASPC

3.1.1. SEM–EDS Analysis

3.1.2. TG-DSC

3.1.3. XRD and FTIR Phase Analysis

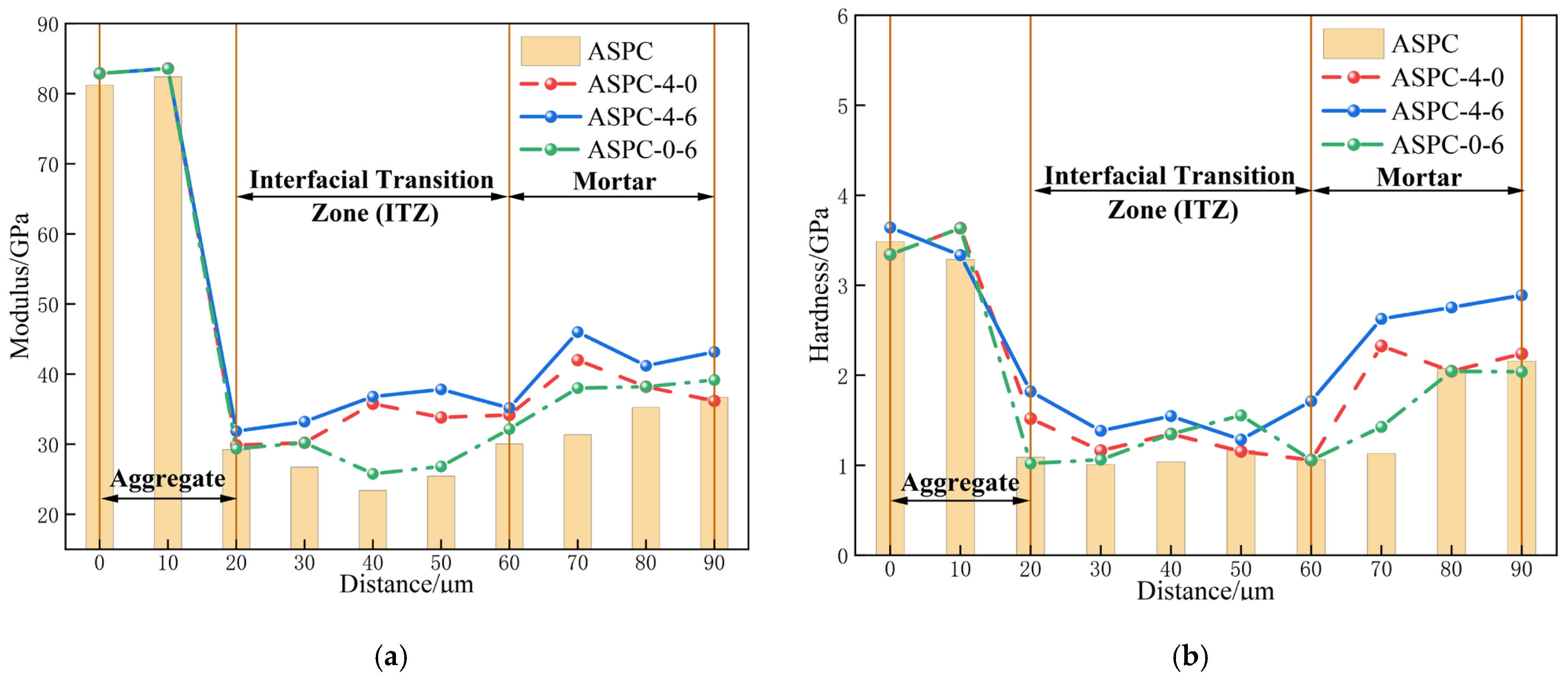

3.1.4. Analysis of Micromechanical Properties at the ITZ

3.1.5. NMR Spectroscopy Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The composite activator achieved the optimal enhancement of ASPC’s mechanical properties: the compressive strength of ASPC-4-6 (4% NaOH + 6% Na2SiO3) at 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d increased by 20.2%, 23.1%, 16.3%, and 11.2%, respectively, compared to ASPC, while its splitting tensile strength increased by 15.1%, 15.9%, 17.6%, and 12.1%, respectively. Among all the groups, ASPC-4-6 exhibited mechanical properties closest to those of ordinary concrete (OC).

- (2)

- The SEM analysis revealed that ASPC-4-0 and ASPC-0-6 had reduced internal un-hydrated particles compared to ASPC, but both had significant crack and pore characterization. In contrast, the microscopic pores inside ASPC-4-6 showed significant filling, along with distinctive elongated prismatic hydration products that were not present in the other groups. EDS analysis showed that these prismatic hydration products consisted mainly of Ca, Si, Al, Na, K, O, and trace amounts of Mg.

- (3)

- The optimal alkali activator group (ASPC-4-6) produces more stable hydration products internally; ASPC-4-6 produced the greatest weight loss at 25~220 °C and 220~600 °C compared to a single activator, and it produced a 1.039% increase in weight loss at 25~220 °C compared to the ASPC group. The weight loss produced in the temperature range of 220~600 °C increased by 2.224%, according to TG-DSC characterization methods, and XRD and FTIR analyses indicated that compound NaOH with Na2SiO3 can improve the mechanical properties of ASPC. This is mainly due to the fact that the complex activators resulted in more highly polymerized stable hydration products and well-filled potassium A-type zeolite crystals in ASPC-4-6. At the same time, the complex stimulant also reduces the generation of amorphous N-A-S-H gels, which are prone to swelling when absorbing water, in the concrete system.

- (4)

- Upon adding NaOH and Na2SiO3, the micromechanical properties, i.e., indentation modulus and hardness, of ASC improved considerably. When complex activator was added, the average indentation modulus and hardness at the ITZ of ASPC increased by 15.5% and 24.4%, respectively. Moreover, the ITZ exhibited significant indentation, and its thickness decreased by ~10 μm.

- (5)

- The NMR analysis revealed a considerable decrease in the T2 spectral area for ASPC-4-6 compared with ASPC, ASPC-4-0, and ASPC-0-6. Furthermore, ASPC-4-6 exhibits a noticeable leftward shift in the T2 spectrum. Simultaneously, the overall porosity ratio of ASPC-4-6 decreased markedly compared with that of ASPC, with a reduction of 0.43% in the proportion of large pores and an increase of 0.21% in the proportion of small pores. This optimization of the pore structure contributes to the overall improvement in the mechanical properties of ASPC.

- (6)

- The comprehensive mechanical properties test and micro-mechanism test show that wind-accumulated sand powder and cement compared to its interior contain a large amount of SiO2 and Al2O3, potassium feldspar, montmorillonite, sodium feldspar and other substances. When NaOH is compounded with Na2SiO3, it will react with the substances in the aeolian sand powder due to OH− to generate beneficial gels such as C-A-S-H gel with a high degree of polymerization and potassium A-type zeolite crystals with filler effect, which will lead to a rise in the mechanical properties of concrete.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Shen, X.; Wei, L.; Dong, R.; Xue, H. Grey model research based on the pore structure fractal and strength of NMR aeolian sand lightweight aggregate concrete. JOM 2020, 72, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elipe, M.G.M.; Lopez-Querol, S. Aeolian sands: Characterization, options of improvement and possible employment in construction—The state-of-the-art. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Zhang, H.M.; Liu, G.X.; Hu, D.W.; Ma, X.R. Basic mechanical properties and influence mechanisms of aeolian sand concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2020, 23, 1212–1221. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Shen, X.D.; Dong, R.X.; Wei, L.S.; Xue, H.J. Grey entropy analysis of influence of pore structure on compressive strength of aeolian sand concrete. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 108–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Seif, E.S.S.A. Assessing the engineering properties of concrete made with fine dune sands: An experimental study. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Zheng, X. A laboratory test of the electrification phenomenon in wind-blown sand flux. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, L.; Guo, H.; Ma, K.; Yun, Z. Effect of aeolian sand powder on the micromechanical properties of aeolian sand concrete and analysis of its enhancement mechanism. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1, 1–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.S.; Sun, D.D.; Wu, K. Research progress on the microstructure of the concrete interfacial transition zone and its numerical simulation methods. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 44, 678–685. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Golewski, G.L. An assessment of microcracks in the interfacial transition zone of durable concrete composites with fly ash additives. Compos. Struct. 2018, 200, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.Z. Modification mechanism of nanosilica on the concrete interfacial transition zone and its multiscale model. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 46, 1053–1058. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.H.; Zhao, Q.X.; Zhang, J.R.; Tong, J.N. Influence of interfacial transition zone on the creep behavior of concrete. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 49, 347–356. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.F.; Shen, X.D.; Zou, Y.X.; Gao, B. Analysis of the improvement of concrete frost resistance with aeolian sand powder based on microstructural characteristics. Trans. CSAE 2018, 34, 109–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanzadeh, S.; Chamack, M.; Mohammadi, A.M.; Zoghi, N. Evaluation of the performance of concrete by adding silica nanoparticles and zeolite: A method deviation tolerance study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 413, 134962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.K.; Nadir, Y.; Girija, K. Effect of source materials, additives on the mechanical properties and durability of fly ash and fly ash-slag geopolymer mortar: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 280, 122443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grutzeck, A.P.W. Alkali-activated fly ashes: A cement for the future. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.G.; Sun, D.S.; Hu, P.H.; Ren, X.M. Experimental study on the preparation of soil geopolymer cement using alkali-activated metakaolin. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. 2008, 31, 617–621. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bondar, D.; Lynsdale, C.J.; Milestone, N.B.; Hassani, N.; Ramezanianpour, A.A. Effect of type, form, and dosage of activators on strength of alkali-activated natural pozzolans. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthi, P.; Poongodi, K.; Saravanan, R.; Gobinath, R. Effect of ratio between Na2SiO3 and NaOH solutions and curing temperature on the early age properties of geopolymer mortar. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 981, 032060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahhal, M.F.; Hamdan, A.; Hajimohammadi, A.; Castel, A.; Kim, T. Hydrothermal synthesis of sodium silicate from rice husk ash: Effect of synthesis on silicate structure and transport properties of alkali-activated concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 178, 107461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surehali, S.; Han, T.; Huang, J.; Kumar, A.; Neithalath, N. On the use of machine learning and data-transformation methods to predict hydration kinetics and strength of alkali-activated mine tailings-based binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Gu, Q.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Ruan, Z.; Huang, J. Effect of basalt fibers and silica fume on the mechanical properties, stress-strain behavior, and durability of alkali-activated slag-fly ash concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 934-2:2009+A1:2012; Admixtures for Concrete, Mortar and Grout—Concrete Admixtures. Definitions, Requirements, Conformity, Marking and Labelling. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2012.

- GB/T 4209-2022; Sodium Silicate for Industrial Use. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 6283-1986; Chemical Products--Determination of Water—Karl Fischer Method (General Method). National Technical Committee 63 on Chemistry: Tianjin, China, 1986. (In Chinese)

- Tang, X. Experiences in Implementing the GB/T50081-2002 Standard. Phys. Chem. Phys. Test. 2003, 39, 544–545. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, W.; Jing, H.; Ou, Z. Multicomponent cementitious materials optimization, characteristics investigation, and reinforcement mechanism analysis of high-performance concrete with full aeolian sand. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.L.; Zhao, B.C.; Xin, J.; Sun, J.P.; Xu, B.W.; Tian, C.; Ning, J.B.; Li, L.Q.; Shao, X.P.; Ren, W.A. Multisolid waste collaborative production of aeolian sand-red mud-fly ash cemented paste backfill. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, J.; Hang, M.; Qu, S. Research on printing parameters and salt frost resistance of 3D printing concrete with ferrochrome slag and aeolian sand. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; An, F.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, T. Effects of cropping patterns on the distribution, carbon contents, and nitrogen contents of aeolian sand soil aggregates in Northwest China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. Aeolian sand stabilized by using fiber- and silt-reinforced cement: Mechanical properties, microstructure evolution, and reinforcement mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, B.; Shen, X.; Zhu, C.; Fang, H. Study on microporosity, mechanics and service life prediction model of aeolian sand powder concrete. JOM 2023, 75, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q. Study on the preparation and mechanical and fatigue properties of alkali excited recycled concrete. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 015027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna Torres, C.A.; González-López, J.R.; Guerra-Cossío, M.Á.; Guerrero-Baca, L.F.; Chávez-Guerrero, L.; Figueroa-Torres, M.Z.; Zaldívar-Cadena, A.A. Effect of physical, chemical, and mineralogical properties for selection of soils stabilized by alkaline activation of a natural pozzolan for earth construction techniques such as compressed earth blocks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Pan, D.; Dan, J.M.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Calcium carbide residue and Glauber’s salt as composite activators for fly ash-based geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 140, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, H.; He, X.; Zeng, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Mao, C. Performances and microstructure of one-part fly ash geopolymer activated by calcium carbide slag and sodium metasilicate powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.W.; Sheng, S.Q.; Guo, J.X. Effect of composite activators on mechanical properties, hydration activity, and microstructure of red mud-based geopolymer. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 8077–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, G.; Sang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Development and characterization of a new multi-strength level binder system using soda residue-carbide slag as composite activator. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 291, 123367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shi, J.; Liang, H.; Jiang, J.; He, Z. Synergistic enhancement of mechanical property of the high replacement low-calcium ultrafine fly ash blended cement paste by multiple chemical activators. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Zhou, H.L.; Ge, C.L.; Chen, Y. Effect of stone powder on the workability and mechanical properties of high-strength manufactured sand concrete. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2021, 39, 804–810. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.H.; Zhang, J.C.; Li, Y.Q.; Du, G.F.; Yang, X. Performance degradation and microstructure of reactive powder concrete after high temperatures. J. Build. Mater. 2022, 1, 1–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.J.; Zheng, J.T.; Zou, C.X.; Li, H. Effect of aeolian sand on the strength and pore structure of aerated concrete. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 52, 112–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Luan, X.; Guan, X.; Niu, G. Study on the deterioration characteristics and mechanisms of recycled brick-concrete aggregate concrete under load-freeze-thaw coupling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 413, 134817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.M.; Hu, X.; Zeng, W.S. Effect of nano-calcium carbonate on the performance of self-compacting recycled concrete. Ind. Constr. 2023, 53, 608–611. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, G.J.; Jiang, H.; Chen, L.Q.; Xie, H.C. Study on the improvement of microstructural interface transition zone between new and old concrete for repair. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 30, 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Yao, Y. Numerical investigations on the influence of ITZ and its width on the carbonation depth of concrete with stress damage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 132, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Li, L. Study on the modification mechanism of recycled brick-concrete aggregate concrete based on water glass solution immersion method. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Luo, D.; Niu, D. Durability evaluation of concrete structure under freeze-thaw environment based on pore evolution derived from deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 467, 140422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition (%) | Physical–Mechanical Properties | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | MgO | SO3 | Other | Setting Time (min) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | |||

| Initial | Final | 3 d | 28 d | 3 d | 28 d | |||||||

| 21.42 | 5.43 | 63.64 | 3.04 | 2.82 | 2.17 | 1.69 | 180 | 395 | 24.8 | 48.9 | 5.0 | 8.1 |

| Chemical Components | SiO2 (%) | Al2O3 (%) | CaO (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | K2O (%) | Na2O (%) | C (%) | MgO (%) | Others (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP | 43.5 | 9.0 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| Physical Properties | Bulk Density (Kg/m3) | Tight Density (Kg/m3) | Apparent Density (Kg/m3) | Void Rate (%) | Water Content (%) | Mud Content (%) | Fineness Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 1370 | 1580 | 2610 | 48 | -- | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| RS | 1730 | 1740 | 2620 | 34 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 3.01 |

| Chemical Components | Na2O (%) | SiO2 (%) | H2O (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na2SiO3 | 32 | 14.5 | 53.5 |

| Sample | Cement | Aeolian Sand Powder (ASP) | River Sand | Aeolian Sand | Coarse Aggregate | Water | NaOH (The Optimal Dosage Is 4%) | Sodium Silicate Solution (The Optimal Dosage Is 6%) | Polycarboxylic Acid Water Reducer (Additives) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | (kg/m3) | |

| OC | 489.8 | 0.0 | 761.9 | 0 | 1777.7 | 210.6 | 3.3 | ||

| ASPC | 244.9 | 244.9 | 380.95 | 380.95 | 1777.7 | 210.6 | 3.3 | ||

| ASPC-4-0 | 244.9 | 244.9 | 380.95 | 380.95 | 1777.7 | 210.6 | 9.80 | 3.3 | |

| ASPC-4-6 | 244.9 | 244.9 | 380.95 | 380.95 | 1777.7 | 210.6 | 9.80 | 14.69 | 3.3 |

| ASPC-0-6 | 244.9 | 244.9 | 380.95 | 380.95 | 1777.7 | 210.6 | 14.69 | 3.3 |

| Sample | Aggregate | ITZ | Mortar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulus | Hardness | Modulus | Hardness | Modulus | Hardness | |

| GPa | GPa | GPa | GPa | GPa | GPa | |

| OC | 82.3509 | 2.5661 | 35.2561 | 1.5798 | 43.2451 | 2.8712 |

| ASPC | 83.4463 | 2.4189 | 24.2109 | 0.8923 | 35.2312 | 1.5045 |

| ASPC-4-0 | 80.3681 | 2.6577 | 30.4457 | 1.0132 | 40.2536 | 1.8024 |

| ASPC-4-6 | 82.2445 | 3.4881 | 34.9664 | 1.5496 | 43.0503 | 2.3562 |

| ASPC-0-6 | 81.6743 | 2.9231 | 30.0561 | 0.9926 | 39.8703 | 1.7901 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Composite Alkali Activator on the Mechanical Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms in Aeolian Sand Powder–Aeolian Sand Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234213

Liu H, Wang Y. The Impact of Composite Alkali Activator on the Mechanical Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms in Aeolian Sand Powder–Aeolian Sand Concrete. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234213

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Haijun, and Yaohong Wang. 2025. "The Impact of Composite Alkali Activator on the Mechanical Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms in Aeolian Sand Powder–Aeolian Sand Concrete" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234213

APA StyleLiu, H., & Wang, Y. (2025). The Impact of Composite Alkali Activator on the Mechanical Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms in Aeolian Sand Powder–Aeolian Sand Concrete. Buildings, 15(23), 4213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234213