Carbonation Depth, Corrosion Assessment, Repairing, and Strengthening of 49-Year-Old Marine Reinforced Concrete Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

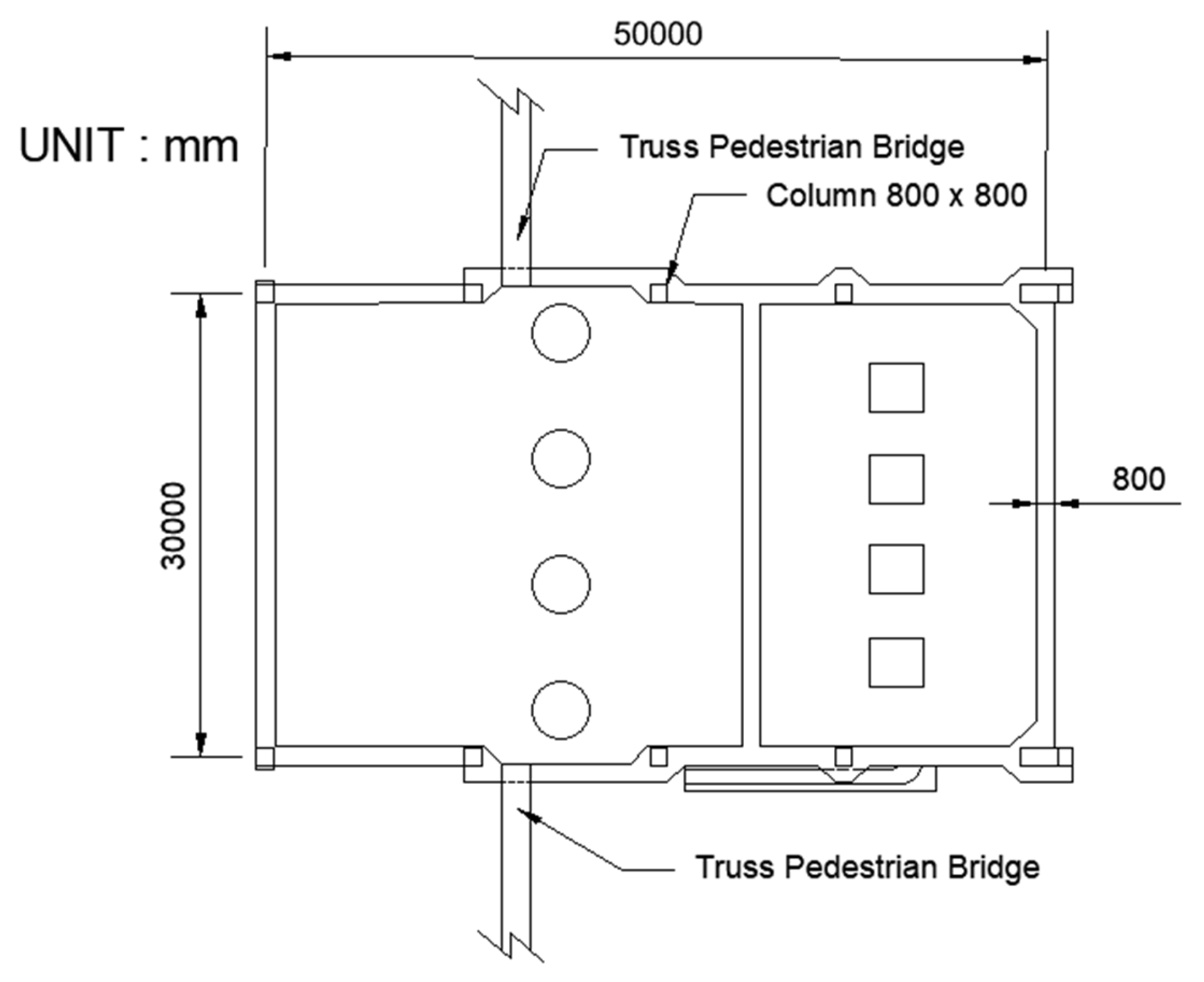

2. Description of the Structures

3. Methods

3.1. Visual Assessment

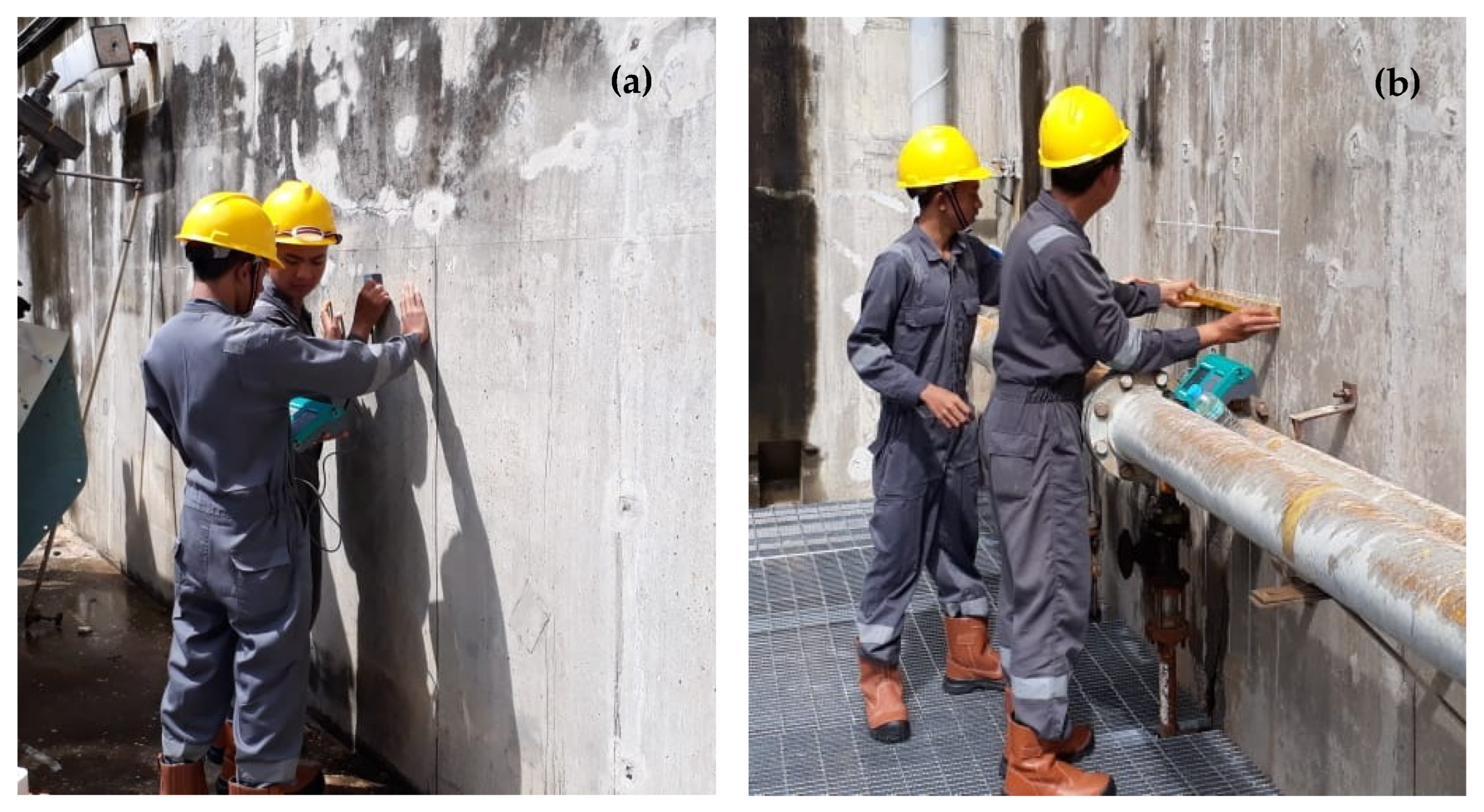

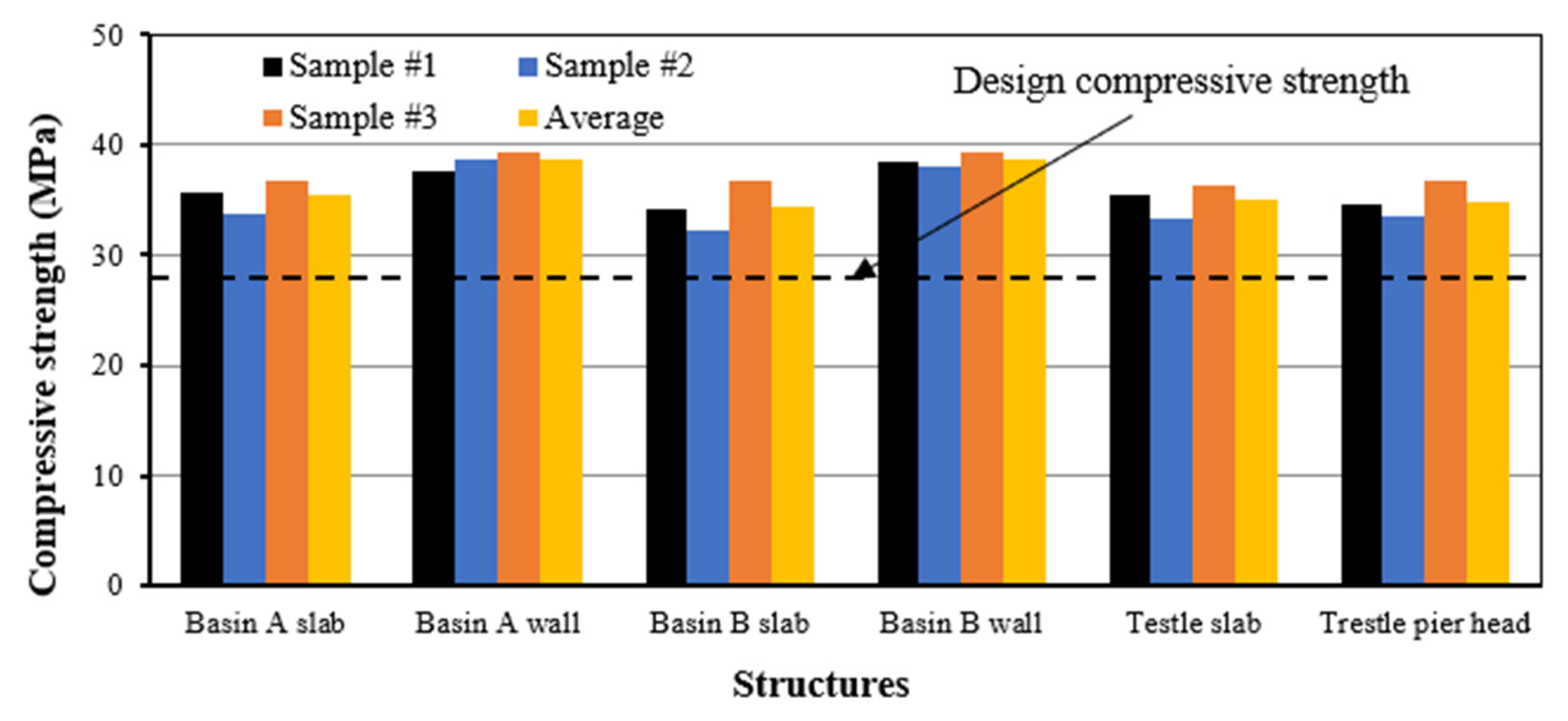

3.2. Concrete Compressive Strength Assessment

3.3. Carbonation Depth Assessment

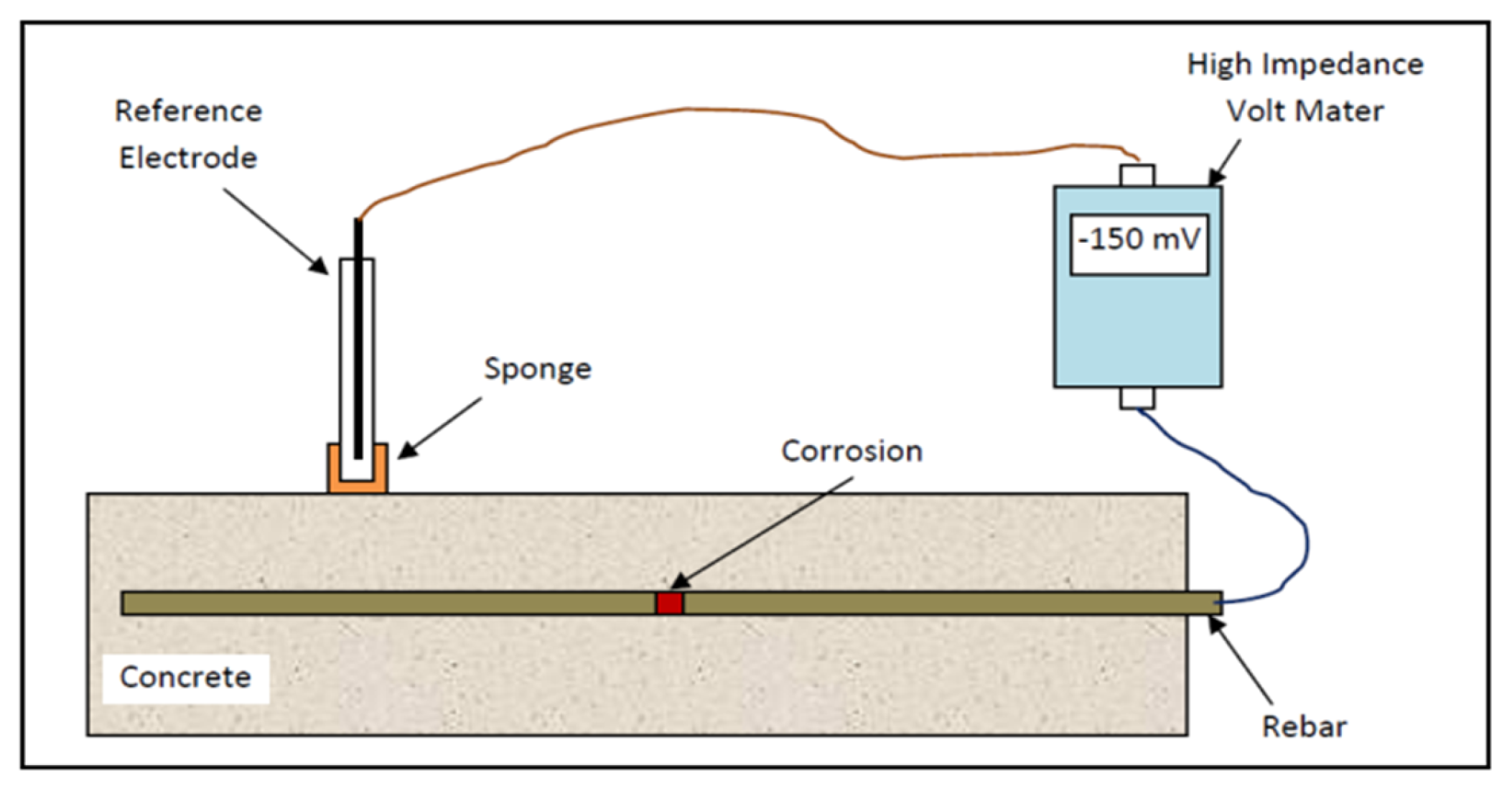

3.4. Corrosion Assessment

4. Assessment Results

4.1. Visual Assessment Results

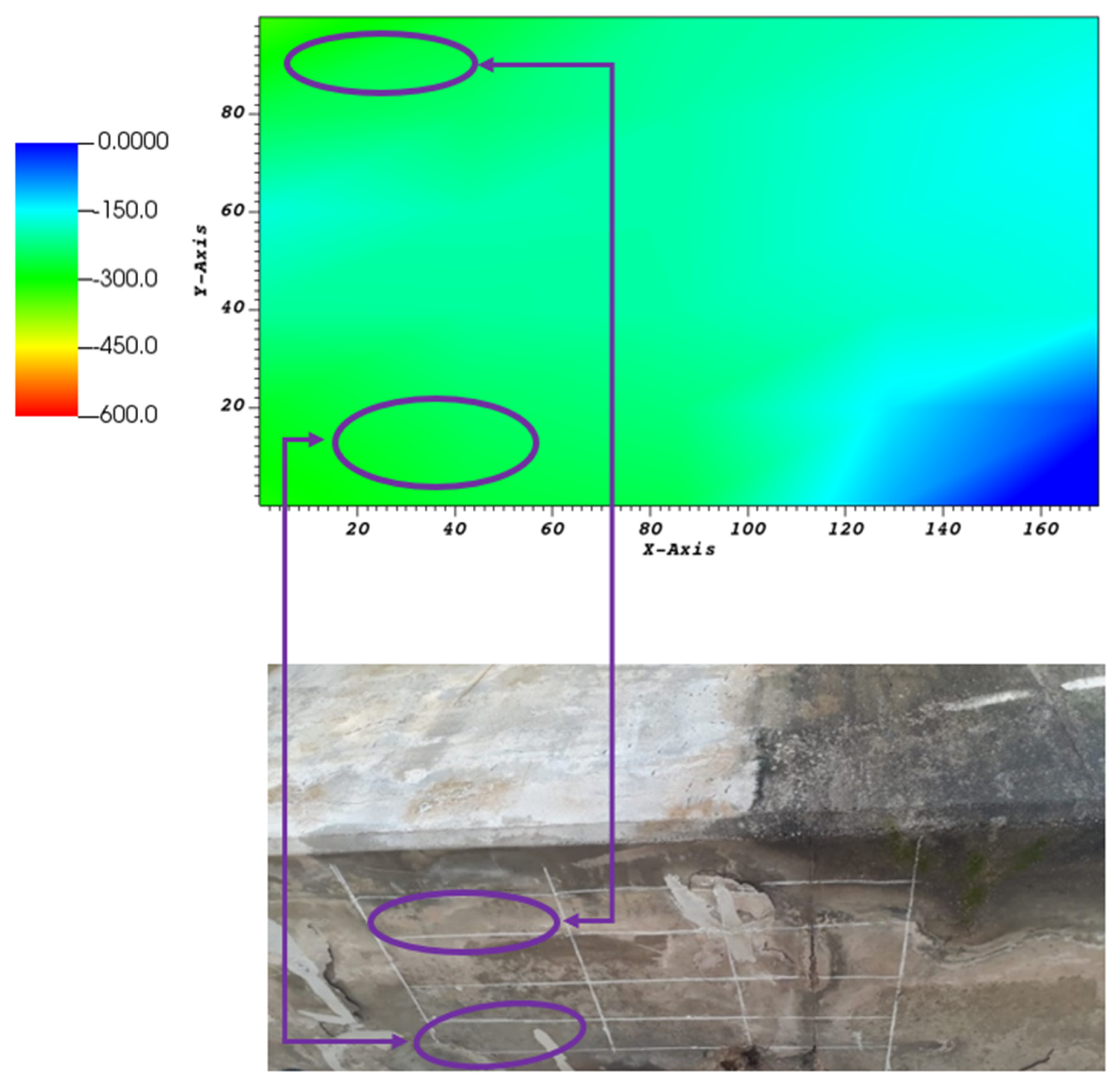

4.1.1. Structure of the Basins

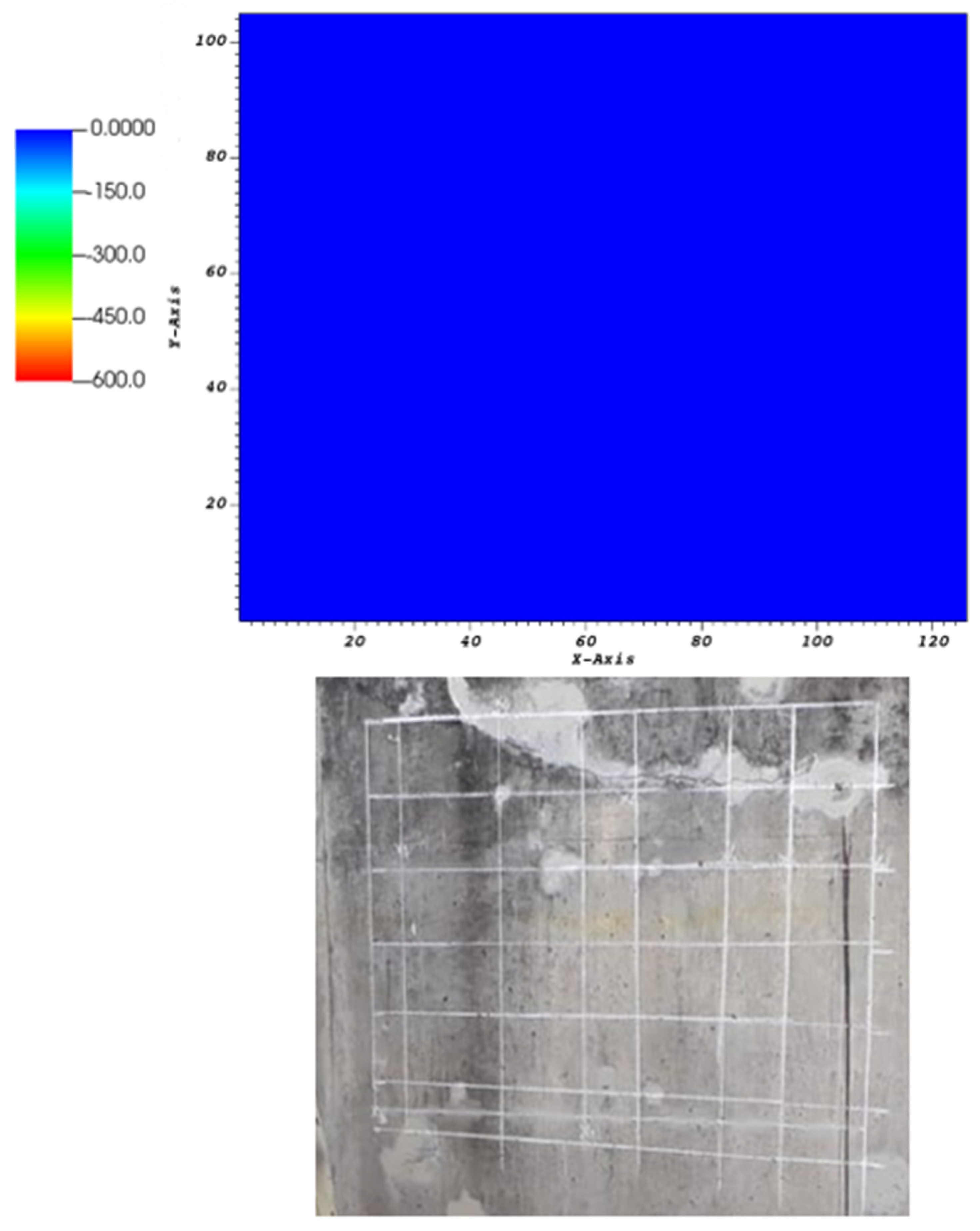

4.1.2. Trestle Slab

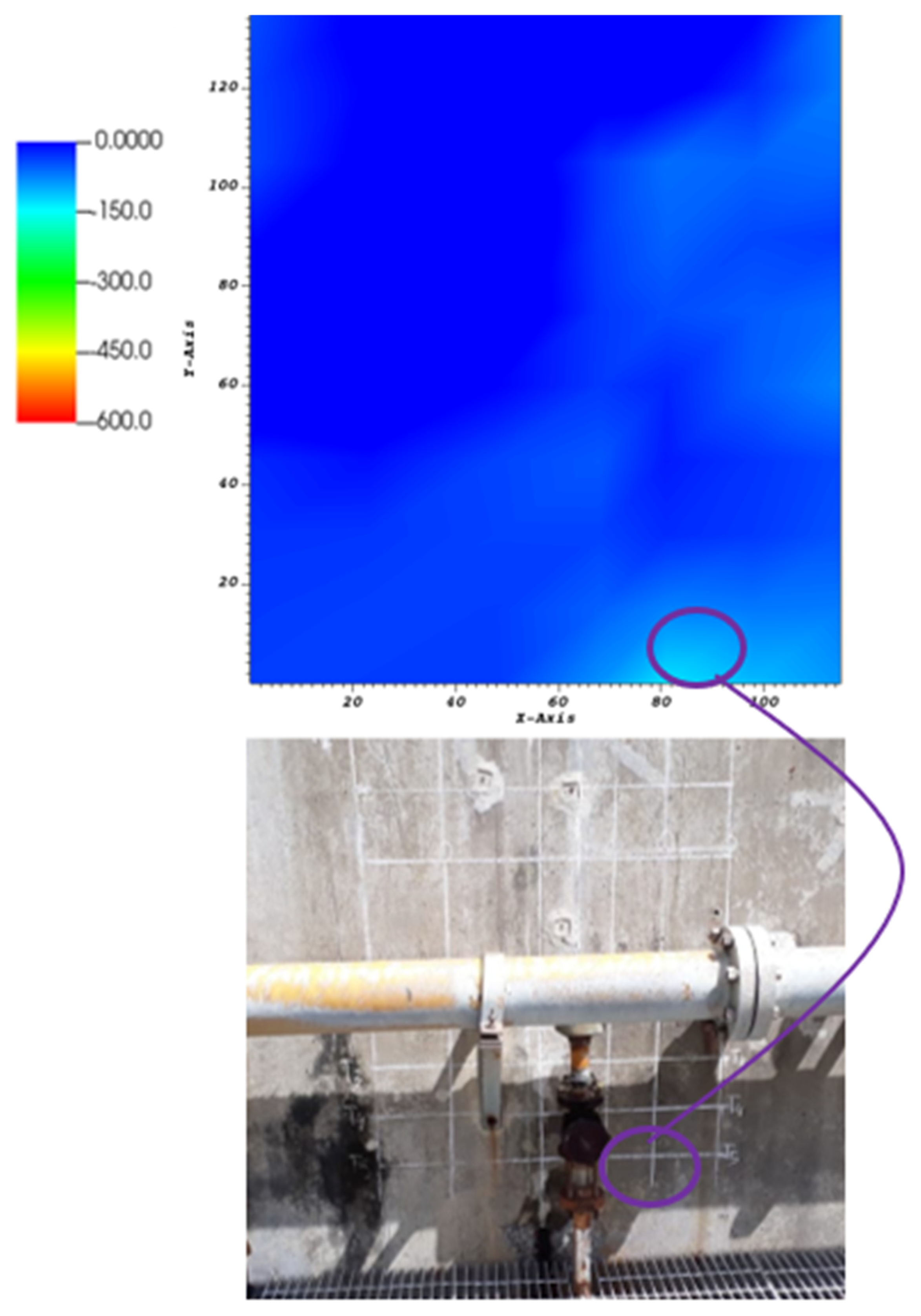

4.1.3. Trestle Pier Head

4.2. Concrete Compressive Strength

4.3. Carbonation Depth

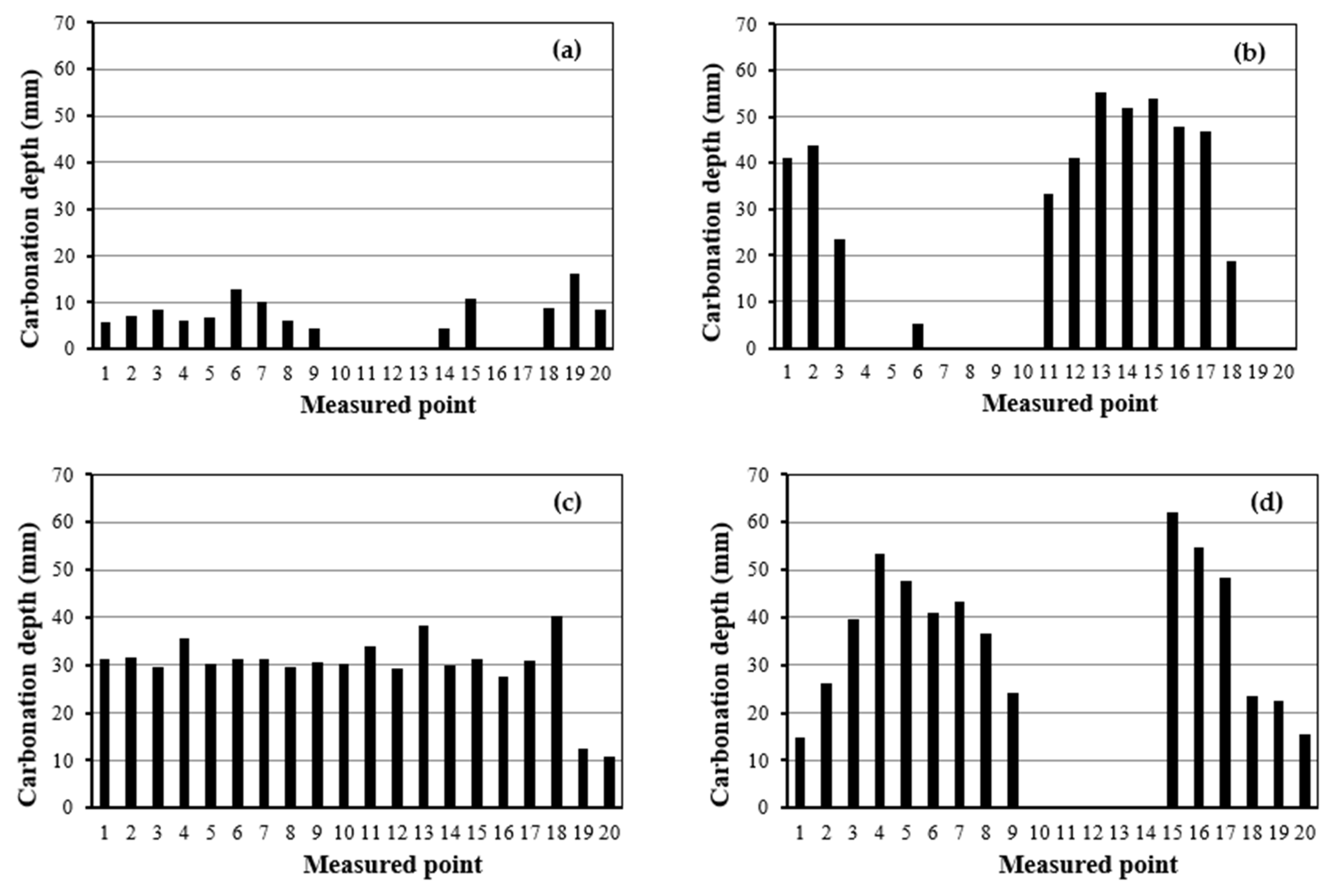

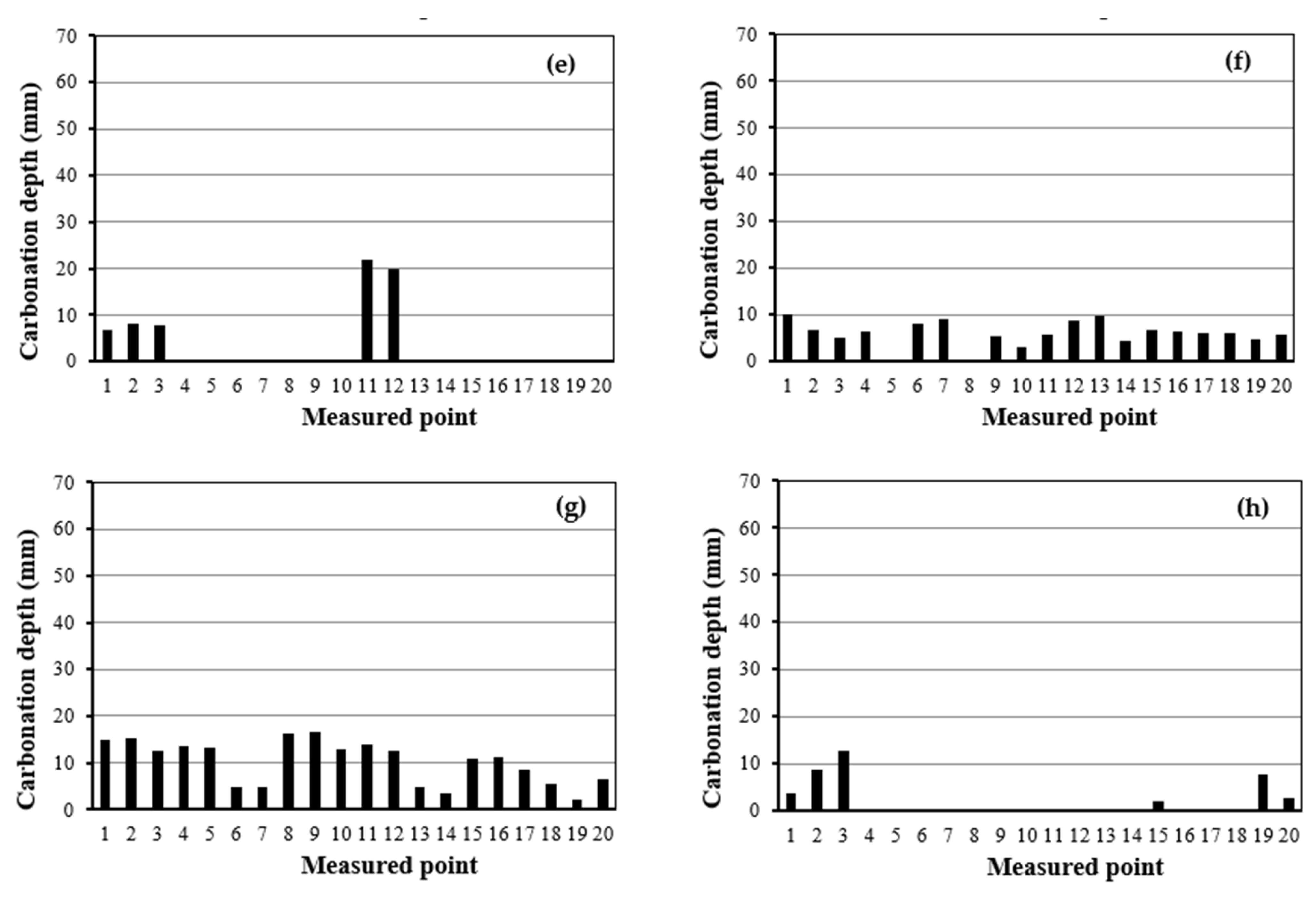

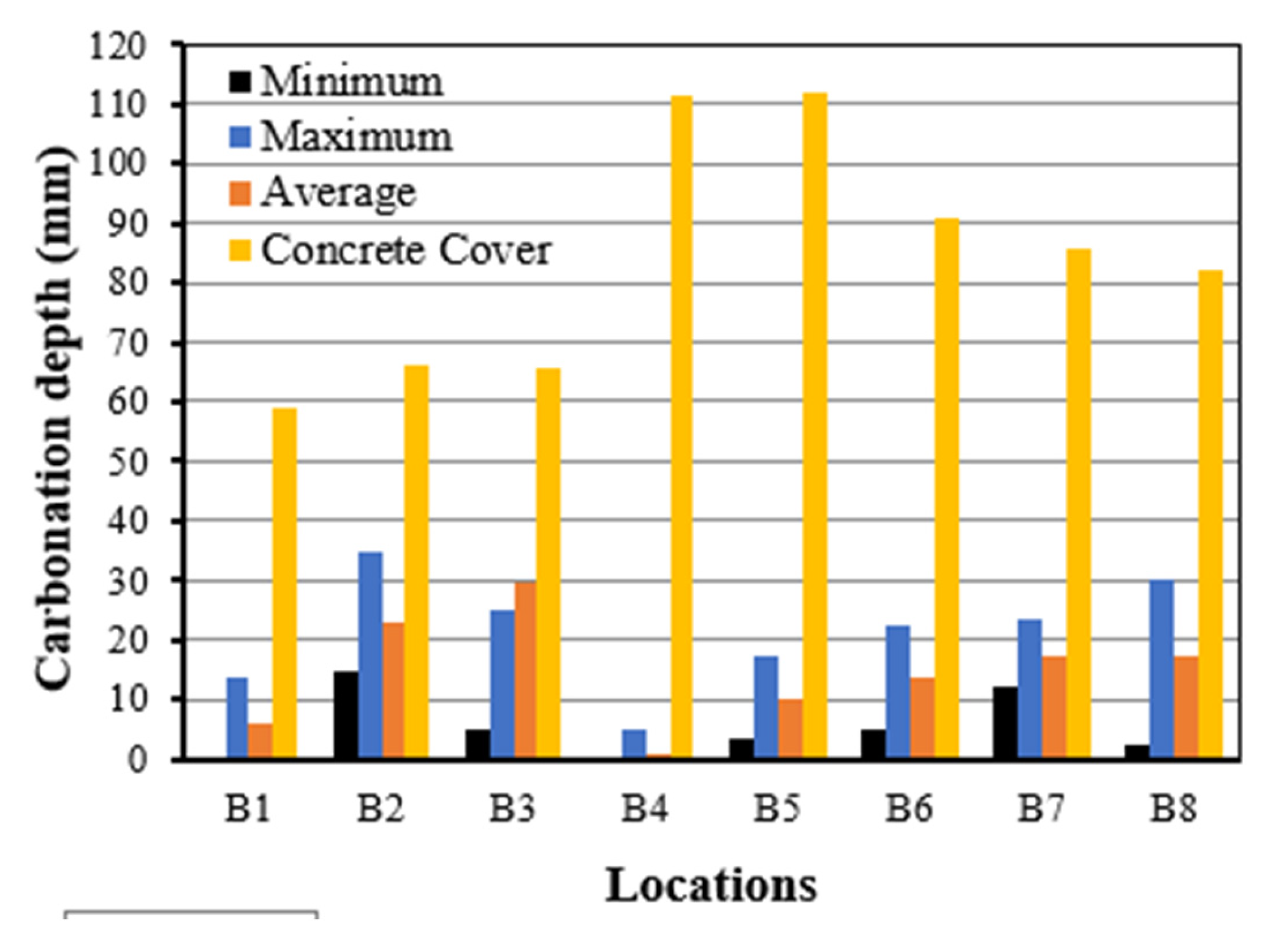

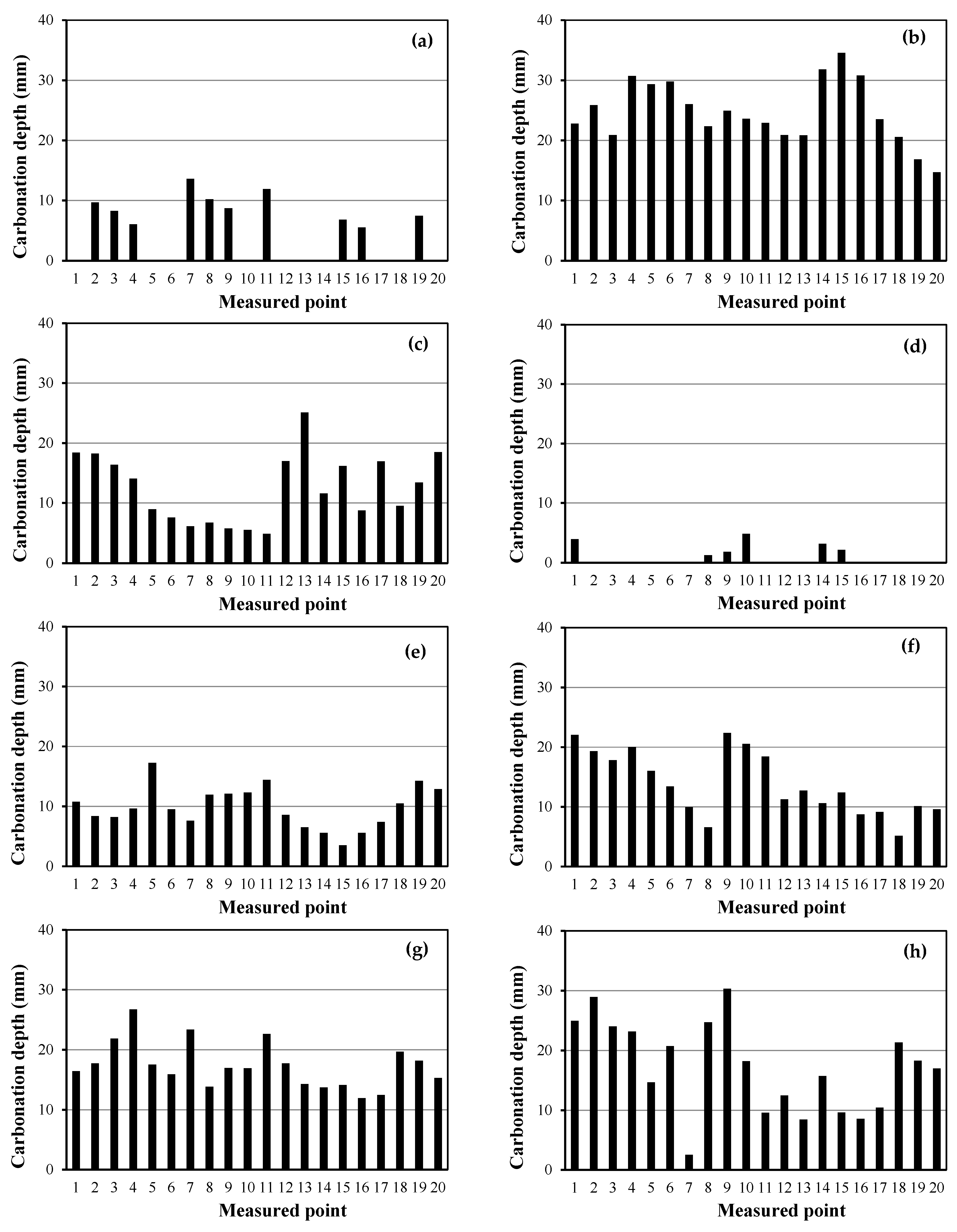

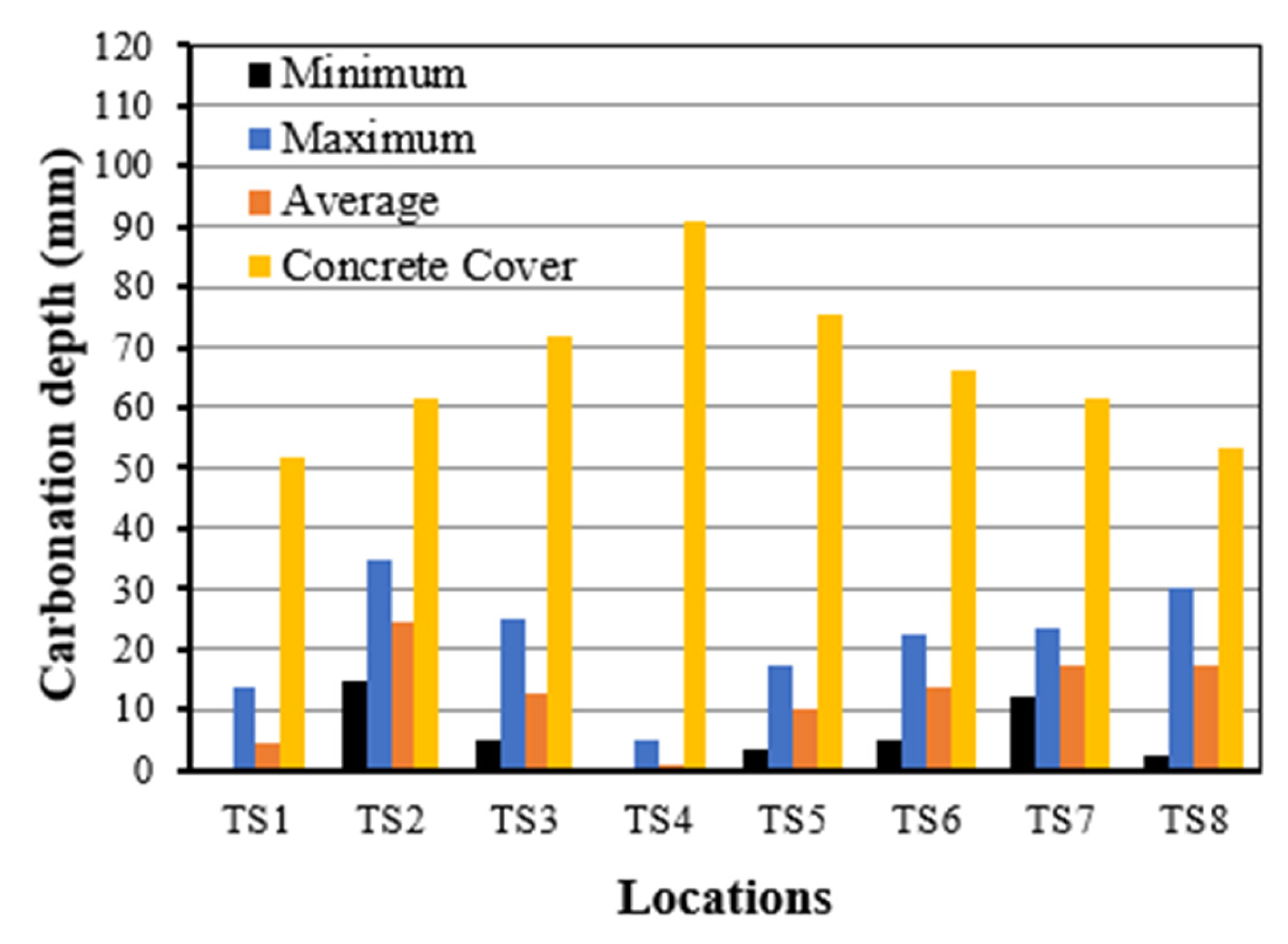

4.3.1. Basin Structures

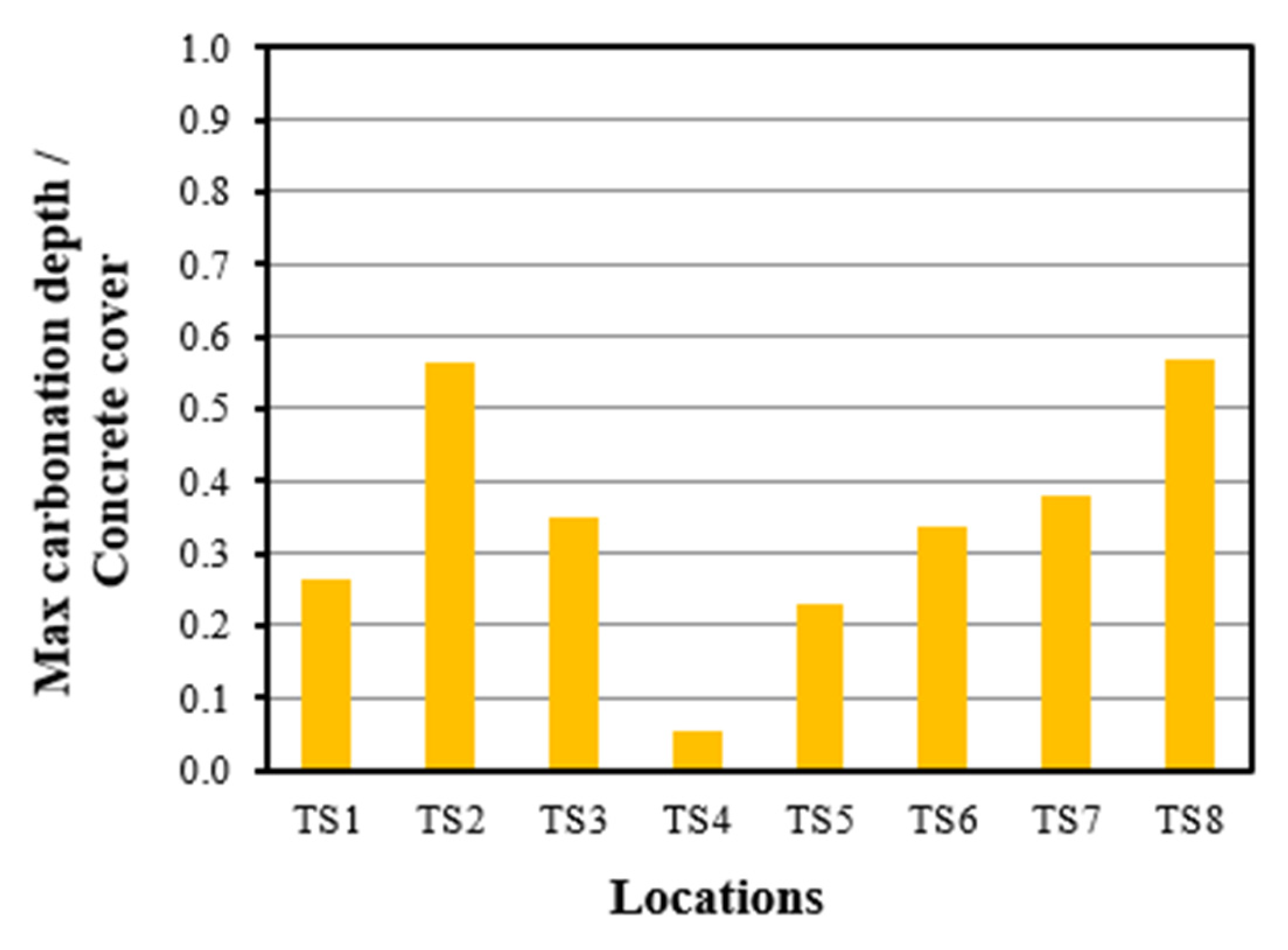

4.3.2. Trestle Slab

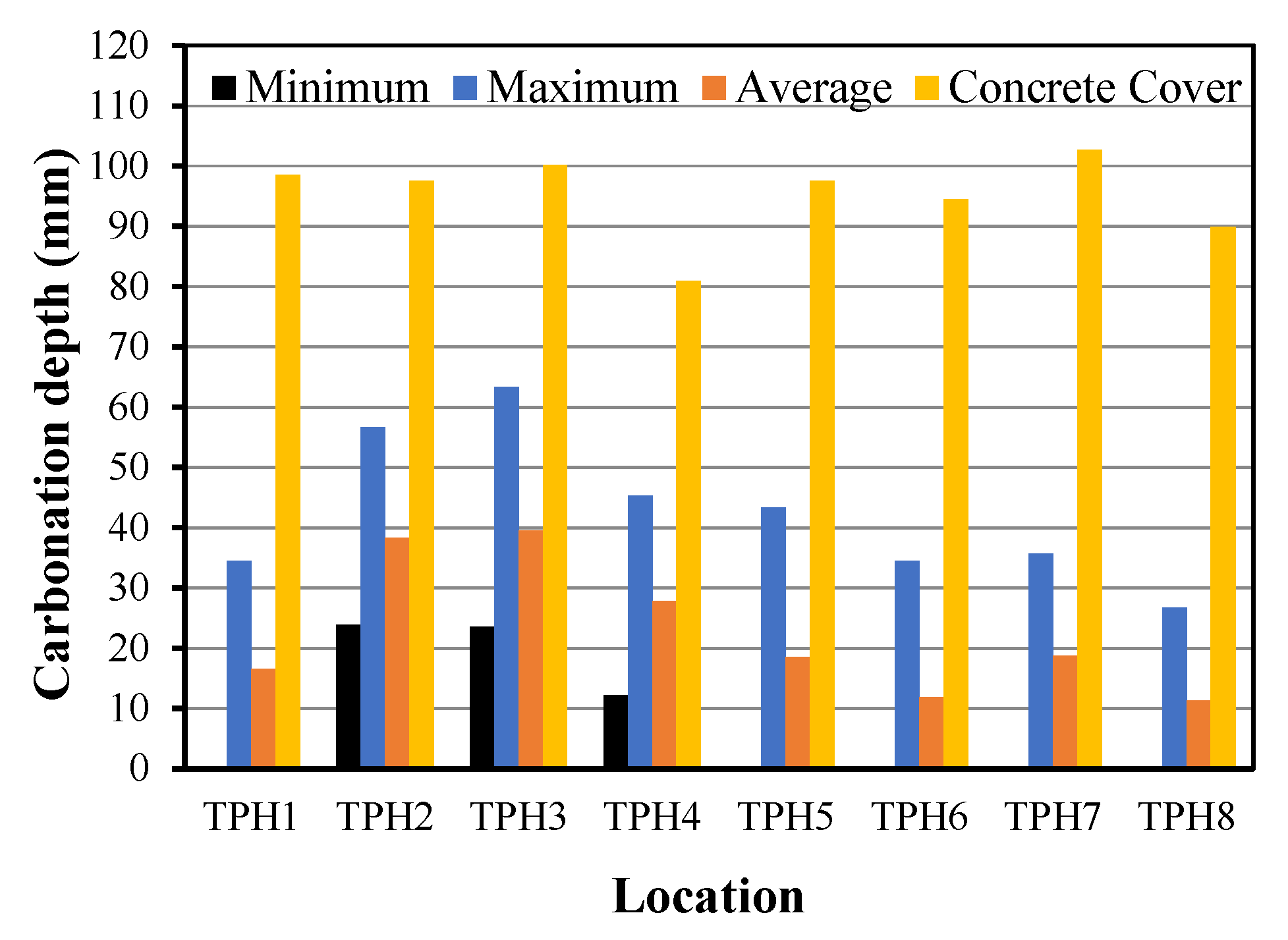

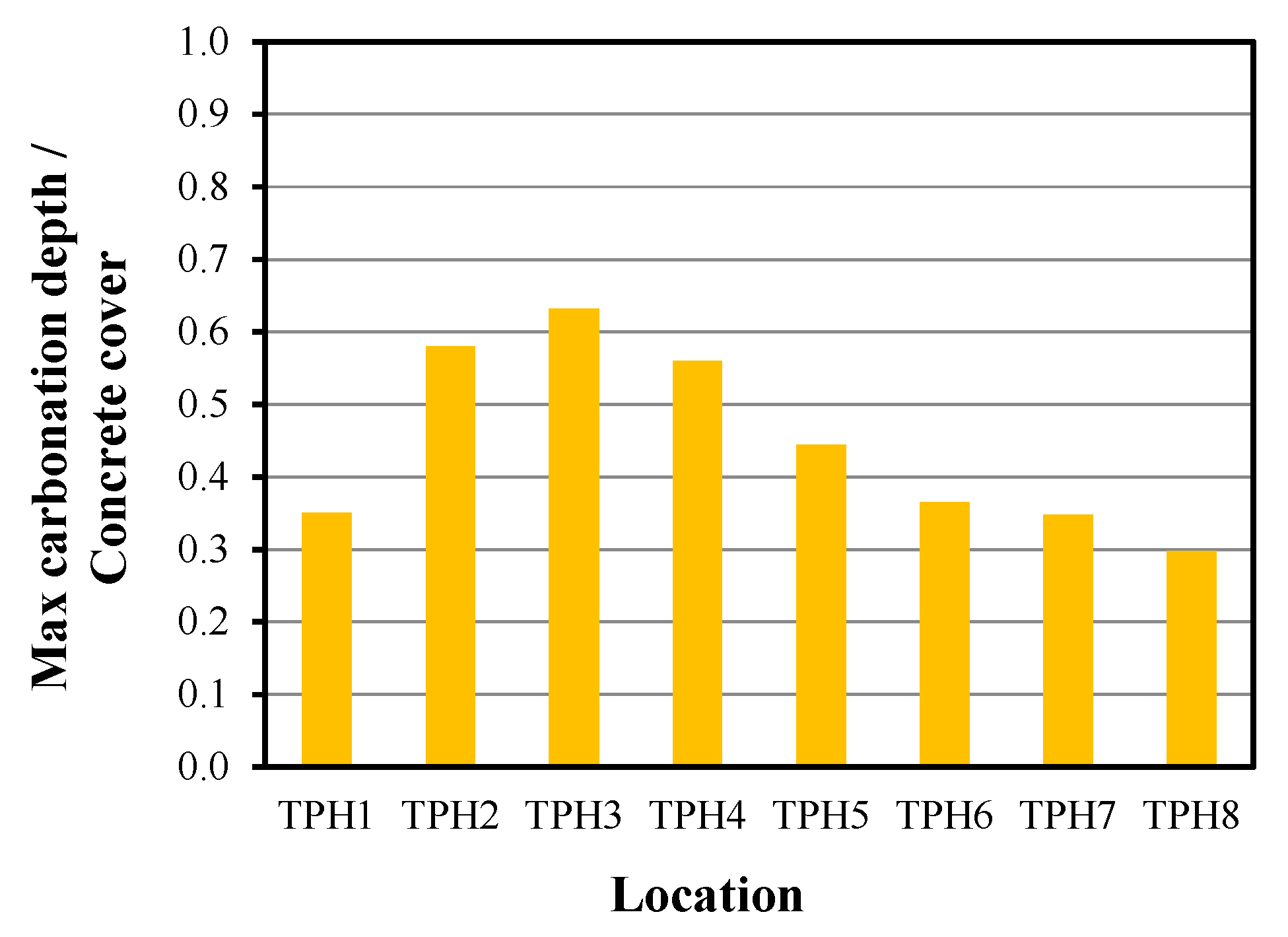

4.3.3. Trestle Pier Head

4.4. Potential Corrosion

5. Repairing and Strengthening Proposal

5.1. Basin Structures

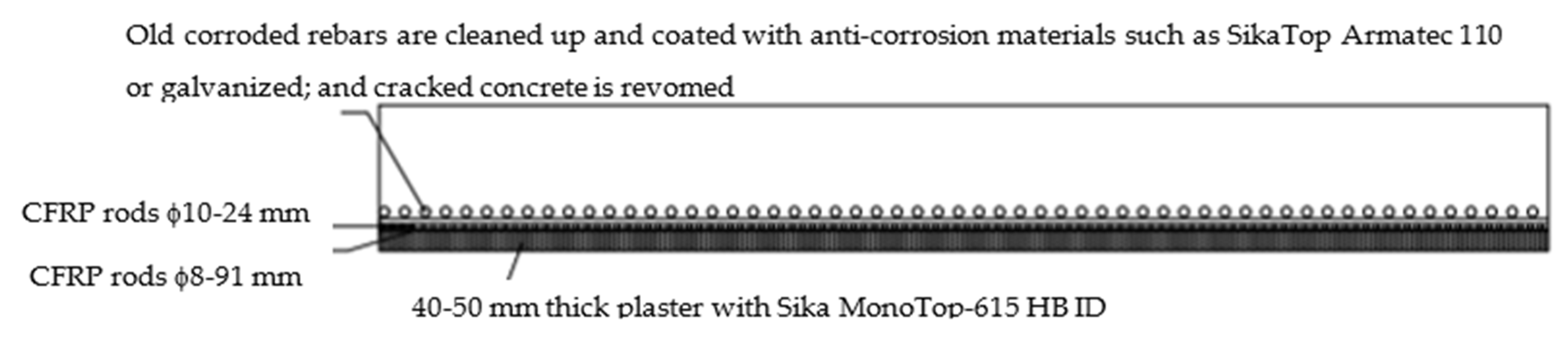

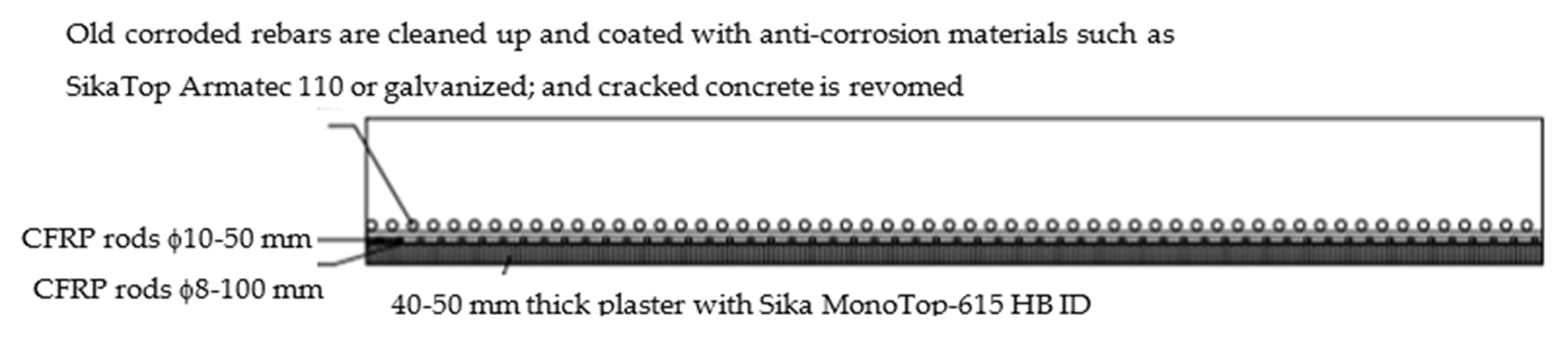

5.2. Trestle Slab

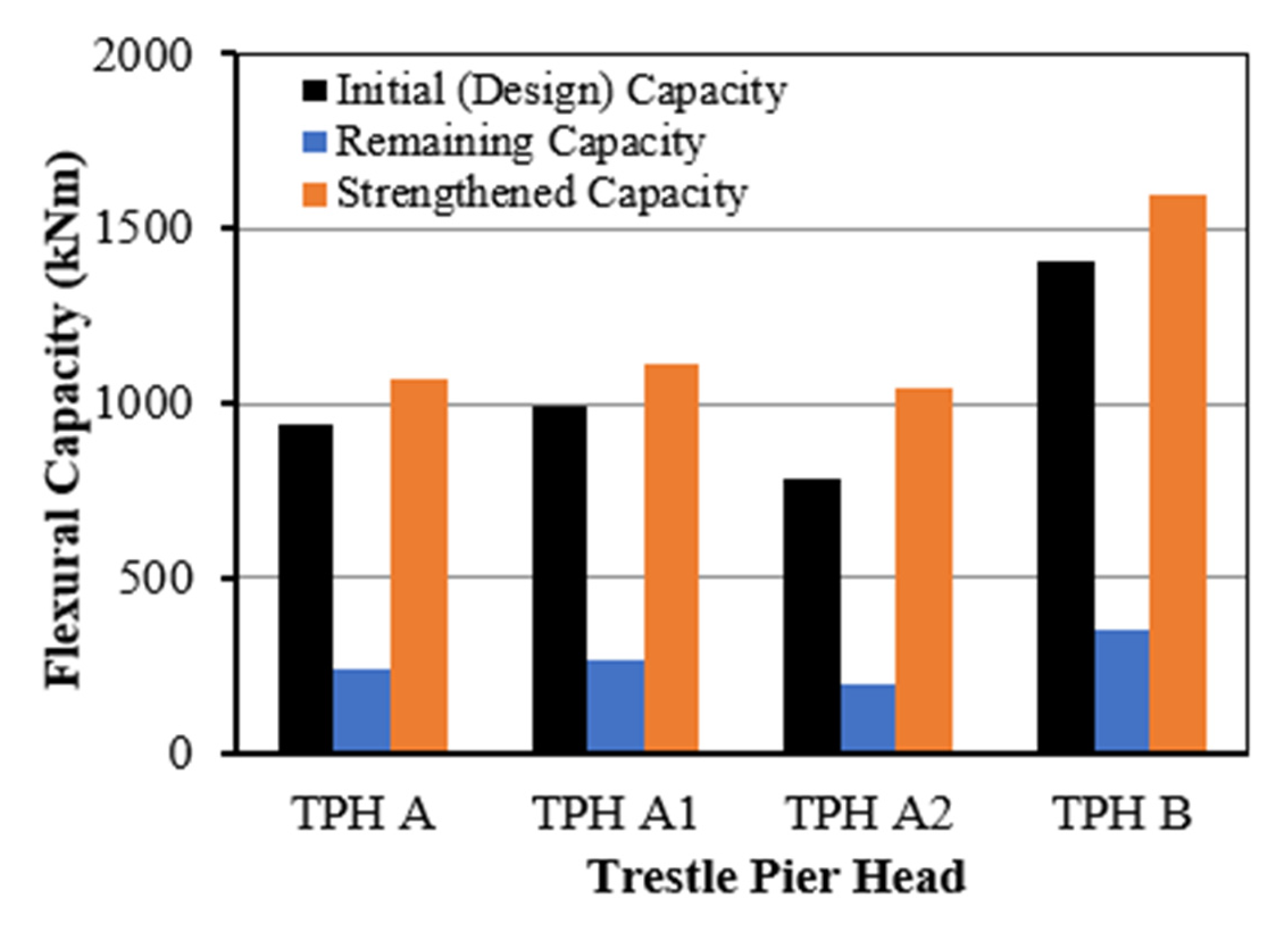

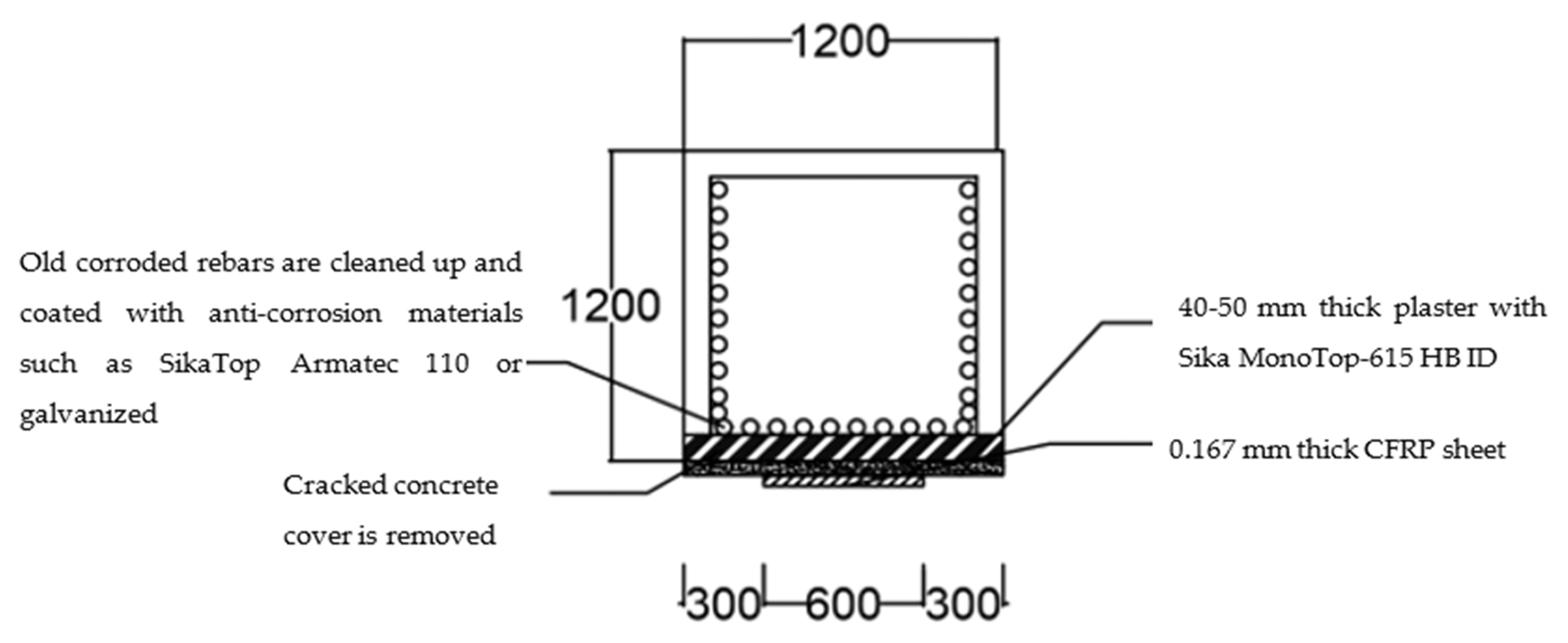

5.3. Trestle Pier Head

6. Conclusions

- Carbonation depth was only measured in areas where reinforcing steel bars had not corroded. The results for the slab and columns of the basin structures showed that the range was from 0 to 52% of the concrete cover. Meanwhile, the trestle slab recorded 0 to 57% of the concrete cover and 0 to 63% for the top and sides of trestle pier head. This showed that a sufficient passive layer existed to protect reinforcing steel from corrosion and ensure a very good condition was maintained.

- Corrosion of reinforcing steel occurred locally and was observed specifically on the outside of the basin walls in areas where tidal activity was present to cause wet and dry cycles. For the trestle building, corrosion only occurred on the bottom of the trestle pier head where seawater was present in some cases and absent due to the tides in other cases. Corrosion was very severe as observed in the cracks and spalling of the concrete cover and the significant reduction in the diameter of reinforcing bars.

- There was no significant corrosion on the inside of the basin walls, but a very small area was observed in Basin A without a reduction in the diameter of reinforcing steel bars. Fine cracks were also observed in some areas inside the Basin B wall. Corrosion potential test conducted showed a low level in both basin walls and a low to medium level on the bottom side of the trestle pier head.

- Rebound hammer, ultrasonic pulse velocity, and compression tests applied to the samples showed that the actual compressive strength of the structures was above the design value.

- The effort to restore the load-bearing capacity of the structures to the design condition led to the strengthening of the outside of the corroded Basin A wall by installing CFRP rods with a diameter of 10 mm at every 24 mm in the vertical direction and 8 mm diameter at every 91 mm. On the outside of the corroded Basin B wall, reinforcement is conducted using CFRP rods with a diameter of 10 mm installed every 50 mm in the vertical direction and 8 mm every 100 mm in the horizontal direction. A similar process is conducted at the bottom of the corroded trestle pier head using a CFRP wrapping system which consisted of CFRP sheets with a thickness of 0.167 mm installed over a width of 600 mm in a single layer. The method required removing all cracked concrete cover, cleaning corrosion on reinforcing steel bars, and galvanizing the remaining part using the hot dip method or coating with epoxy resin with corrosion inhibitor. Reinforcing steel bars are subsequently covered with cementitious, polymer-modified repair mortar containing reactive micro-silica before applying CFRP rods or sheet.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, W.K. Steel reinforcement corrosion in concrete—An overview of some fundamentals. Corr. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DorMohammadi, H.; Pang, Q.; Murkute, P.; Árnadóttir, L.; Isgor, B. Investigation of iron passivity in highly alkaline media using reactive-force field molecular dynamics. Corr. Sci. 2019, 157, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.V.; Meena, T. A review on carbonation study in concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 263, 032011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Lee, H.S.; Min, S.H.; Lim, S.M.; Singh, J.K. Carbonation-induced corrosion initiation probability of rebars in concrete with/without finishing materials. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimshin, V.; Truntov, P. Determination of carbonation degree of existing reinforced concrete structures and their restoration. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 135, 03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, M.; Poyet, S.; L’Hostis, V.; Bjegović, D. Carbonation of low-alkalinity mortars: Influence on corrosion of steel and on mortar microstructure. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 101, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Scrivener, K.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Bishnoi, S. Changes in microstructure characteristics of cement paste on carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 109, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, J.B.; Júnior, C. Carbonation of surface protected concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 49, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyciechowski, P.; Wolinski, P.; Adamczewski, G. Prediction of carbonation progress in concrete containing calcareous fly ash co-binder. Materials 2009, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atis, C.D. Accelerated carbonation and testing of concrete made with fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, W. Carbonation of cement-based materials: Challenges and opportunities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Rea, S.P.; Corral-Higuera, R.; Gómez-Soberón, J.M.; Castorena-González, J.H.; Orozco-Carmona, V.; Almaral-Sánchez, J.L. Carbonation rate and reinforcing steel corrosion of concretes with recycled concrete aggregates and supplementary cementing materials. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georget, F.; Soja, W.; Scrivener, K.L. Characteristic lengths of the carbonation front in naturally carbonated cement pastes: Implications for reactive transport models. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 134, 106080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPC-18 Measurement of hardened concrete carbonation depth. Mater. Struct. 1988, 21, 453–455. [CrossRef]

- Weerdt, K.D.; Plusquellec, G.; Revert, A.B.; Geiker, M.; Lothenbach, B. Effect of carbonation on the pore solution of mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 118, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangni-Foli, E.; Poyet, S.; Le Bescop, P.; Charpentier, T.; Bernachy-Barbe, F.; Dauzeres, A.; L’Hopital, E.; d’Espinose de Lacaillerie, J.B. Carbonation of model cement pastes: The mineralogical origin of microstructural changes and shrinkage. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 144, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Han, T.; Liao, W.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Kumar, A.; Ma, H. Prediction of surface chloride concentration of marine concrete using ensemble machine learning. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 136, 106164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Jędrzejewska, A.; Varughese, A.E.; James, J. Influence of pore structure on corrosion resistance of high performance concrete containing metakaolin. Cem. Wapno Beton 2022, 27, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.; Gonthier, J.N.; Georget, F.; Scrivener, K.L. Insights on chemical and physical chloride binding in blended cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 156, 106747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, V.; Muralidharan, S.; Thangavel, K.; Srinivasan, S. Influence of activated fly ash on corrosion-resistance and strength of concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, B. Influence of fly ash on corrosion resistance and chloride ion permeability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, V.G. Effect of supplementary cementing materials on concrete resistance against carbonation and chloride ingress. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Heede, P.; De Keersmaecker, M.; Elia, A.; Adriaens, A.; De Belie, N. Service life and global warming potential of chloride exposed concrete with high volumes of fly ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 80, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, C.; Sheils, E. Probability-based assessment of the durability characteristics of concretes manufactured using CEM II and GGBS binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.D.A.; Hooton, R.D.; Scott, A.; Zibara, H. The effect of supplementary cementitious materials on chloride binding in hardened cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.T.E.; Sarker, P.K.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Hosan, A. Chloride permeability and chloride-induced corrosion of concrete containing lithium slag as a supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 471, 140629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousidis, N.; Ioannou, I.; Rakanta, E.; Koutsodontis, C.; Batis, G. Effect of fly ash chemical composition on the reinforcement corrosion, thermal diffusion and strength of blended cement concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, C.E.T.; Reichert, T.A.; Savaris, G. Contribution for durability studies based on chloride profiles analysis of real marine structures in different marine aggressive zones. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 206, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidari, O.; Singh, B.K.; Maheshwari, R. Effect of corrosion on bond between reinforcement and concrete-an experimental study. Discover Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffesea, W.Z.; Sistonen, E. Service life prediction of repaired structures using concrete recasting method: State-of-the-art. Proc. Eng. 2013, 57, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, P.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X. Chloride diffusion and corrosion assessment in cracked marine concrete bridged using extracted crack morphologies. Buildings 2025, 15, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabarak, A.; Hasan, M.; Saidi, T.; Fonna, S. Assessment and strengthening of cement plant clinker silo structure due to corrosion of reinforcing bars. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Experimental and Computational Mechanics in Engineering. ICECME 2022, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 15 September 2022; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Mubarak, A.; Fikri, R.; Mahlil. Crack and strength assessment of reinforced concrete cement plant blending silo structure. Mater Today Proc. 2022, 58, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, Z.; Di Carlo, F.; Spagnuolo, S.; Meda, A. Influence of localised corrosion on the cyclic response of reinforced concrete columns. Eng. Struct. 2022, 256, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.Q.; Gu, X.L.; Zeng, Y.H.; Zhang, W.P. Flexural behavior of corrosion-damaged prestress concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 2022, 272, 114985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Frangopol, D.M. Fatigue reliability analysis considering corrosion effects and integrating SHM information. Eng. Struct. 2022, 272, 114967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.S.; Anadh, K.; Kuntal, V.S.; Jiradilok, P.; Nagai, K. Investigating the effect of rebar corrosion order and arrangement on cracking behaviour of RC panels using 3D discrete analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tian, Y.; Fang, D.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H.; Jin, X.; Fu, C.; He, R. The influence of longitudinal rebar type and stirrup ratio on the bond performance of reinforced concrete with corrosion. Constr. Build Mater. 2023, 409, 133943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syll, A.S.; Kanakubo, T. Residual bond strength in reinforced concrete cracked by expansion agent filled pipe simulating rebar corrosion. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, H.; Hao, Y. Damage prediction of RC columns with various levels of corrosion deteriorations subjected to blast loading. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangat, P.S.; Elgarf, M.S. Flexural strength of concrete beams with corroding reinforcement. ACI Struct. J. 1999, 96, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbela, G.; Alexander, M.; Moyo, P. Variation of steel loss and its effect on the ultimate flexural capacity of RC beams corroded and repaired under load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngunyen, T.; Truong, T.T.; Thoi, T.N.; Bui, L.V.H.; Ngunyen, T.H. Evaluation of residual flexural strength of corroded reinforced concrete beams using convolutional long short-term memory neural networks. Structures 2022, 46, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, S. Exploring the shear performance and predictive shear capacity of corroded RC columns utilizing the modified compression-field theory: An investigative study. Eng. Struct. 2024, 302, 117390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ding, H.; Gu, X.L.; Zhang, W.P. Calibration analysis of calculation formulas for shear capacities of corroded RC beams. Eng. Struct. 2023, 286, 116090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, N.H.; Gu, X.L.; Wei, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z. Study of the confinement performance and stress-strain response of RC columns with corroded stirrups. Eng. Struct. 2022, 266, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalee, W.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Effects of W/B ratios and fly ash finenesses on chloride diffusion coefficient of concrete in marine environment. Mater. Struct. 2009, 42, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslakovic, I.S.; Bjegovic, D.; Mikulic, D. Evaluation of service life design models on concrete structures exposed to marine environment. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Shams, M.A.; Bheel, N.; Almaliki, A.H.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Dodo, Y.A.; Benjeddou, O. A review on chloride induced corrosion in reinforced concrete structures: Lab and in situ investigation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 37252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Feng, H.; Jin, N.; Jin, X.; Wu, H.; Shao, Y.; Yan, D.; et al. Comparison of detection methods for carbonation depth of concrete. Scient. Rep. 2023, 13, 19980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 562-19; Code Requirements for Assessment, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Existing Concrete Structures. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019.

- ASTM C805/C805-M-18; Standard Test Method for Rebound Number of Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM C597-22; Standard Test Method for Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM C876-15; Standard Test Method for Corrosion Potentials of Uncoated Reinforcing Steel in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Papadakis, V.G.; Vayenas, C.G.; Fardis, M.N. Fundamental modeling and experimental investigation of concrete carbonation. Mater. J. 1991, 88, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Q.; Peng, X.; Qin, F. A Review of Concrete Carbonation Depth Evaluation Models. Coatings 2024, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yio, M.; Wong, H.; Buenfeld, N. Development of more accurate methods for determining carbonation depth in cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 175, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Cai, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Yuan, M.; Qu, F. Time-dependent model for in-situ concrete carbonation depth under combined effects of temperature and relative humidity. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, Z. Effects of Environmental Factors on Concrete Carbonation Depth and Compressive Strength. Materials 2018, 11, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 440.2R-17; Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019.

- ASTM A123/A123M-15; Standard Specification for Zinc (Hot-Dip Galvanized) Coating on Iron and Steel Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM A153/A153M-16a; Standard Specification for Zinc Coating (Hot-Dip) on Iron and Steel Hardware. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

| Buildings | Members | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|

| Basin A | Slab | 3 |

| Wall | 3 | |

| Basin B | Slab | 3 |

| Wall | 3 | |

| Trestle | Slab | 3 |

| Pier head | 3 |

| Buildings | Members | Number of Tested Locations |

|---|---|---|

| Basin A | Slab | 20 |

| Wall | 20 | |

| Column | 10 | |

| Basin B | Slab | 20 |

| Wall | 20 | |

| Column | 10 | |

| Trestle | Slab | 20 |

| Pier head | 20 |

| Locations | Pulse Velocity (m/s) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basin A wall | 3583 | 27.76 | 34.90 |

| Basin A slab | 3487 | 26.30 | 31.30 |

| Basin A coumn | 3627 | 28.45 | 36.64 |

| Basin B wall | 3592 | 27.90 | 35.25 |

| Basin B slab | 3564 | 27.47 | 34.16 |

| Basin B column | 3589 | 27.86 | 35.13 |

| Trestle slab | 3592 | 27.90 | 35.25 |

| Trestle pier head | 3654 | 28.88 | 37.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasan, M.; Fonna, S.; Saidi, T.; Hasibuan, P.; Bukhary, F.; Dawood, R.; Mahlil; Mubarak, A. Carbonation Depth, Corrosion Assessment, Repairing, and Strengthening of 49-Year-Old Marine Reinforced Concrete Structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 4088. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224088

Hasan M, Fonna S, Saidi T, Hasibuan P, Bukhary F, Dawood R, Mahlil, Mubarak A. Carbonation Depth, Corrosion Assessment, Repairing, and Strengthening of 49-Year-Old Marine Reinforced Concrete Structures. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4088. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224088

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasan, Muttaqin, Syarizal Fonna, Taufiq Saidi, Purwandy Hasibuan, Fachrurrazi Bukhary, Rahmad Dawood, Mahlil, and Azzaki Mubarak. 2025. "Carbonation Depth, Corrosion Assessment, Repairing, and Strengthening of 49-Year-Old Marine Reinforced Concrete Structures" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4088. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224088

APA StyleHasan, M., Fonna, S., Saidi, T., Hasibuan, P., Bukhary, F., Dawood, R., Mahlil, & Mubarak, A. (2025). Carbonation Depth, Corrosion Assessment, Repairing, and Strengthening of 49-Year-Old Marine Reinforced Concrete Structures. Buildings, 15(22), 4088. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224088