Abstract

Historic urban public parks have evolved into multifunctional spaces that integrate cultural heritage and contemporary urban life. Understanding public perception of their heritage value is crucial for sustainable management. This study proposes a novel method combining grounded theory with Python-based analysis of textual and visual social media data to evaluate public perception of cultural heritage value in 12 historic urban public parks in Shanghai. The constructed system includes four dimensions, eleven criteria, and thirty-five indicators. Results show significant differences in perceived values: social and ecological values gain the highest recognition, while historical and spiritual values are underappreciated due to limited narrative continuity and static displays. Parks such as Luxun, Changfeng, and Zhongshan demonstrate outstanding comprehensive value, whereas Nanyuan and Jing’an show weaker performance. Based on perception indices, the parks were classified into four hierarchical management tiers, guiding targeted conservation and renewal strategies. The findings highlight the potential of social media data for revealing public attitudes toward cultural heritage and offer a replicable framework for adaptive management of historic urban parks in Shanghai and other metropolitan contexts.

1. Research Background and Theoretical Basis

1.1. Research Background

In 2017, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) jointly issued the “Document on Historic Urban Public Parks”, proposing the heritage concept of “historic urban public parks” [1]. Since then, historic urban public parks have been treated as a distinct type for protection. In the United Kingdom, gardens with a history of over 30 years are considered to possess historical value, leading to the establishment of the Registered Historic Parks and Gardens system in the 1980s, categorized into three protection levels [2]. In China, scholars define historic parks as public gardens with historical significance and commemorative value, containing historical remnants and significant connections to important historical backgrounds, figures, and events [3].

Amid rapid urbanization, historic parks face the dual challenge of protecting cultural heritage while meeting modern public demands. They must not only fulfill cultural and educational functions but also accommodate contemporary needs for leisure, recreation, and health. Moreover, they need to adapt to changes in urban land use and mobility systems. Consequently, historic parks require continuous renewal and adaptation, and the mechanisms of value perception and transformation urgently need deeper exploration.

However, existing research has several limitations. First, most studies focus on the conservation of physical relics and landscape authenticity, with insufficient attention to how intangible cultural values are perceived and transmitted through visitor experiences. Second, while numerous studies have analyzed Shanghai’s parks, few have systematically examined the perceptual mechanisms linking physical space, cultural activation, and public cognition of heritage value. Third, most quantitative studies rely on static survey data, lacking dynamic and multidimensional evaluation frameworks that can capture real-time public perceptions.

This study addresses these research gaps by focusing on two core questions: (1) How can the cultural heritage value embedded in historic urban public parks be transformed into visitors’ perceptual experiences through environmental design and cultural activities? (2) What guiding significance does the perception-based evaluation of heritage value have for optimizing park design and hierarchical protection strategies? Taking 12 historic parks in Shanghai as cases, this paper systematically evaluates heritage protection and display, heritage activation and utilization, and environmental construction from a public perspective, revealing the intrinsic link between spatial intervention and cultural value transmission.

1.2. Theoretical Basis

The theoretical basis for the perception and evaluation of cultural heritage value in historic urban public parks revolves around three core aspects: (1) the multidimensional framework of cultural heritage value; (2) the evolution of perception evaluation theory; and (3) methodological approaches. The classification of cultural heritage values has been a longstanding focus of international heritage discourse. As shown in Table 1, the Athens Charter (1931) [4] and subsequent ICOMOS documents established the foundational triad of historical, artistic, and scientific values. Later frameworks, such as the Nara Document on Authenticity (1994) [5] and The Burra Charter (1999, revised) [6], expanded the conceptual boundaries to include social, aesthetic, and spiritual dimensions, highlighting the importance of authenticity and community meaning. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (2019) [7] further integrated emotional, cultural, and landscape values, reflecting the growing recognition of non-material dimensions. In China, corresponding policy frameworks, including the Law on Intangible Cultural Heritage (2011) and Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Relics (2015) [8], have enriched this classification system with social and natural elements.

This paper synthesizes these theoretical sources and adopts a four-category framework—natural, historical, social, and spiritual values—as the conceptual basis for constructing the evaluation system. This framework reflects the international consensus on the multidimensional nature of heritage while aligning with China’s current protection standards. Cultural heritage value, in this sense, is understood as a social relationship in which the heritage object meets the evolving needs of people [9,10].

Since the late 1970s, landscape perception evaluation research abroad has made limited methodological progress [11]. Two primary paradigms—expert-based and public-based assessment—remain mainstream [12]. Existing research explores both the process of perception psychology (e.g., audiovisual, emotional, or physiological responses) and the outcomes of perception (e.g., satisfaction and value feedback). With the advent of big data, emotional computing has evolved toward recognition, monitoring, and prediction [13], while social media analysis has introduced dynamic, real-time perspectives into landscape evaluation.

Table 1.

Dimensions of cultural heritage value at home and abroad.

Table 1.

Dimensions of cultural heritage value at home and abroad.

| Policy Documents | Dimensions of Cultural Heritage Value |

|---|---|

| ICOMOS, 1931 [4] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific (archaeological) value |

| “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage” [14] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value |

| “Nara Document on Authenticity” (1994) [5] | Artistic value, historical value, social value, scientific value |

| “The Burra Charter” (1999 revised edition) [6] | Aesthetic value, historical value, scientific value, social value, spiritual value |

| “Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention” (2019 revised edition) [7] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value, emotional value, aesthetic value, cultural value, landscape value |

| “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Intangible Cultural Heritage” (2011) | Historical value, literary value, artistic value, scientific value |

| “Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Relics in China” (2015) [8] | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value, social value, cultural value, natural element value |

| “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics” (2017 revised edition) | Historical value, artistic value, scientific value |

Recent studies have explored perception-based heritage evaluation using digital tools. Bazac Titu developed a semantic algorithm based on Google data to analyze Romanian user behavior in historic parks [15]; Aikaterini G et al. integrated landscape assessment, stakeholder surveys, and SWOT analysis to construct management guidelines [16]; Dai Daixin et al. employed sentiment analysis of online texts from Shanghai’s parks to establish cultural service indicators [17]. Despite these advances, a comprehensive perception evaluation framework addressing the cultural heritage value of historic parks remains underdeveloped.

Social media-based analysis, with its efficiency in capturing multi-stakeholder preferences, provides a new methodological path. This study identifies elements of cultural heritage value perception through dual-channel coding of online text and images, constructs a quantitative evaluation system, and proposes hierarchical protection strategies—establishing a closed-loop mechanism between value cognition and protection practice to support adaptive heritage management.

2. Research Design

2.1. Study Area

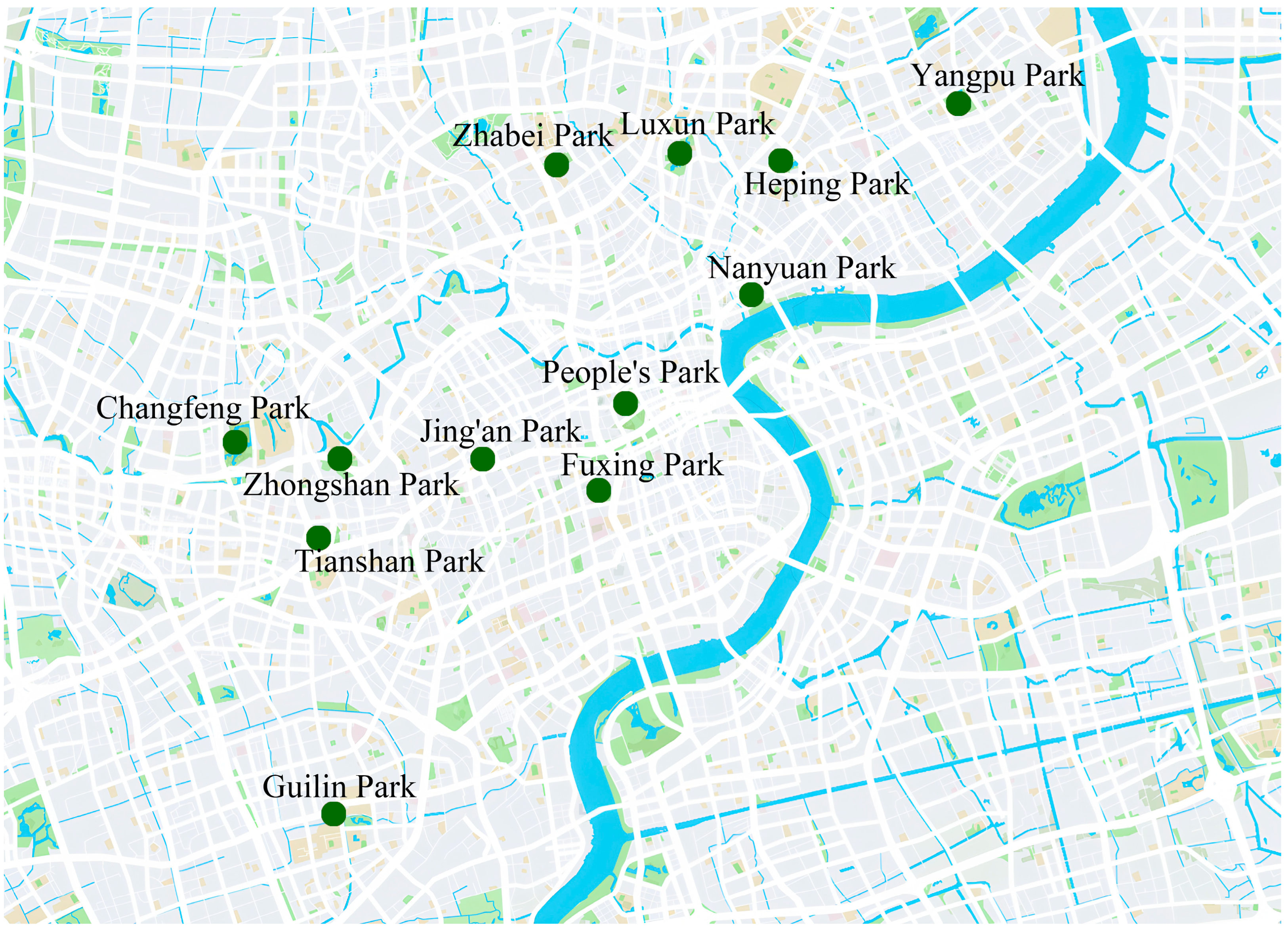

Shanghai’s historic parks integrate the artistic features of traditional Chinese gardens with modern landscape design, reflecting the city’s layered history and diverse cultural influences [18]. According to one classification of historic urban parks—“urban parks built in modern or contemporary times and existing for more than 50 years” [3]—and drawing on the Shanghai Urban Park Directory (2025 Edition) and the Shanghai Master Plan (2017–2035), this study selected 12 representative parks as research cases (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location distribution map of the twelve historic urban public parks in Shanghai.

These parks (presented in Table 2) were chosen because they (1) cover different historical periods from the late Qing dynasty to the 1950s, (2) represent varied spatial patterns and cultural backgrounds across different districts, and (3) embody the transformation of Shanghai’s urban public park system from traditional commemorative gardens to modern urban parks. This diversity ensures that the selected cases are representative of Shanghai’s broader park typology and historical evolution.

Table 2.

Summary table of Shanghai historic urban public parks.

2.2. Data Sources and Screening

Considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism and public activity, this study focused on data from the three years prior to the pandemic (1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019). Using Python (v3.8.10) for web scraping, a total of 20,156 textual and visual comments were initially collected from Ctrip and Dianping (Meituan-Dianping) platforms.

Data collection was conducted using the Requests, BeautifulSoup, and Selenium libraries for scraping, and the Pandas, Jieba, and re (regular expression) libraries for text cleaning and analysis. Word frequency analysis was used to remove meaningless words, resulting in 16,307 valid comments and more than 72,400 images. The Jieba library was applied for word segmentation and frequency statistics, integrating four mainstream Chinese stop word lists (Chinese, Harbin Institute of Technology, Baidu, and Sichuan University) and adding custom stop words such as “Lu Xun’s Tomb”, “Lu Xun Memorial Hall”, and “British Concession”.

Given the large data volume, random sampling using the random module was conducted multiple times until the top 30 keywords from the sample data were consistent with those from the full dataset, ensuring representativeness. Finally, 3060 comments and 6800 images were used for subsequent coding analysis.

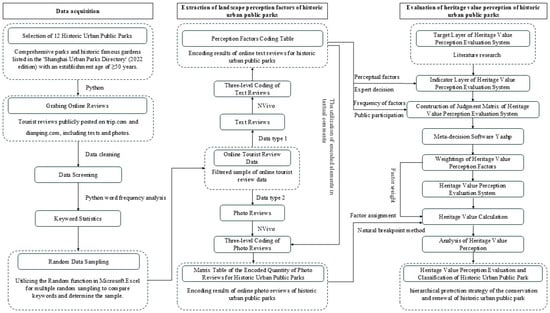

2.3. Technical Route (Figure 2)

Based on grounded theory, NVivo 12.0 was used to perform “open-axial-selective” three-level coding on the textual and visual comments of 12 historic parks in Shanghai, constructing a heritage value perception evaluation system. Specifically, the heritage value perception elements extracted from text analysis were used as the criterion layer, and a judgment matrix was constructed to determine weights based on coding frequencies; the quantity matrix of visual elements from image comments was used to assign scores to perception factors. The perception index for each park was calculated by combining weights and scores, providing a quantitative basis for hierarchical protection.

Figure 2.

Technical route.

Figure 2.

Technical route.

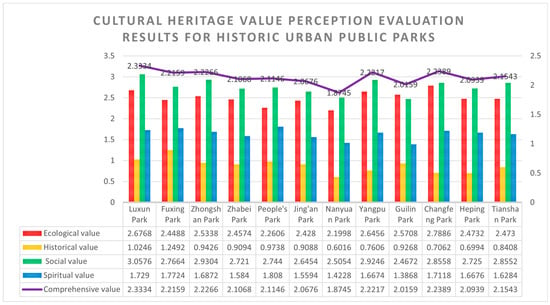

3. Construction of the Heritage Value Perception Evaluation System for Historic Urban Public Parks

3.1. Extraction of Cultural Heritage Value Perception Elements Through Online Text Coding

This study adopts grounded theory as the core analytical framework and uses NVivo 12 qualitative analysis software to process online comments from twelve historic urban public parks in Shanghai. NVivo enables the systematic parsing and organization of unstructured data such as user comments, allowing the extraction of conceptual categories and their interrelationships.

Following the grounded theory procedure, the research process included three progressive stages—open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. In the open coding stage, original comments were carefully read and segmented into meaningful textual units, each conceptualized according to frequently used words and context-specific expressions. Through this process, 158 initial concepts (third-level codes) were identified, generating a total of 11,598 reference points.

Subsequently, axial coding was conducted to integrate related concepts and establish hierarchical relationships among them. The 158 initial concepts were refined and grouped into 38 categories (second-level codes). Finally, selective coding synthesized these categories into 11 core themes (first-level codes), forming a complete three-level coding structure that reflects the cultural heritage perception dimensions of visitors.

To ensure the scientific rigor of the coding process, a secondary sampling test (40 comments per park) was conducted, confirming data saturation and theoretical validity. Based on grounded theory, this study examines the process of public perception formation from a participant perspective and reveals the dynamic correlation between visitor behavior, spatial experience, and cultural value interpretation. The resulting multi-level coding framework provides a systematic foundation for subsequent quantitative evaluation and practical design strategies (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of cultural heritage value perception element coding for historic urban public parks.

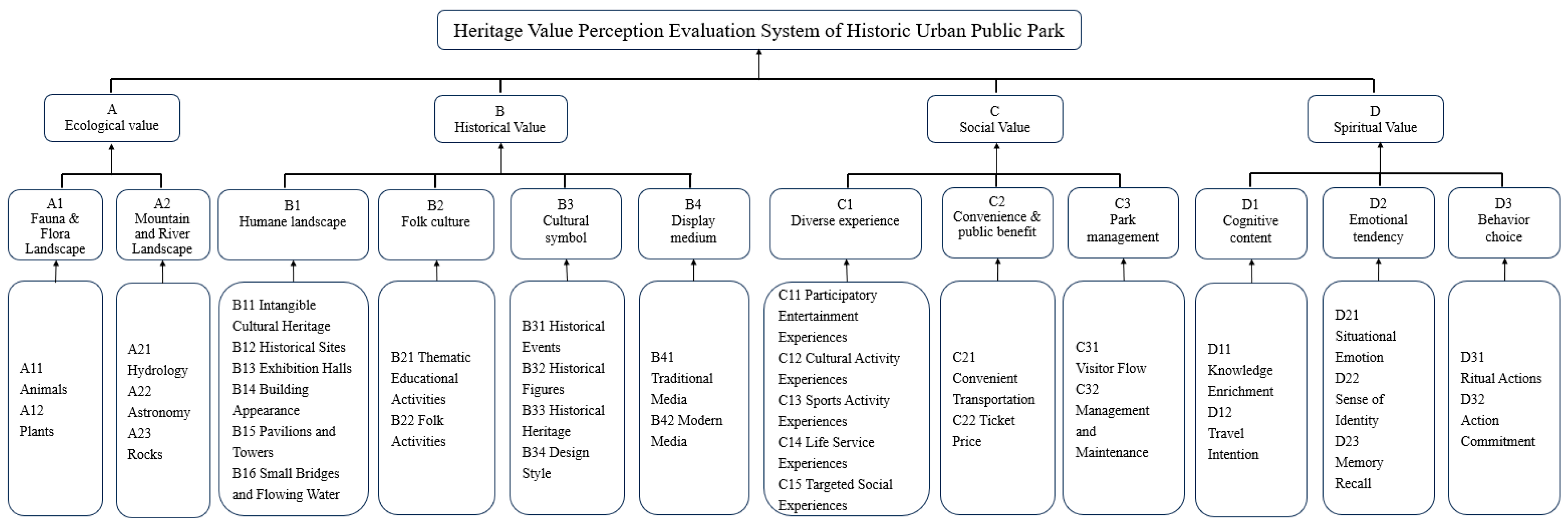

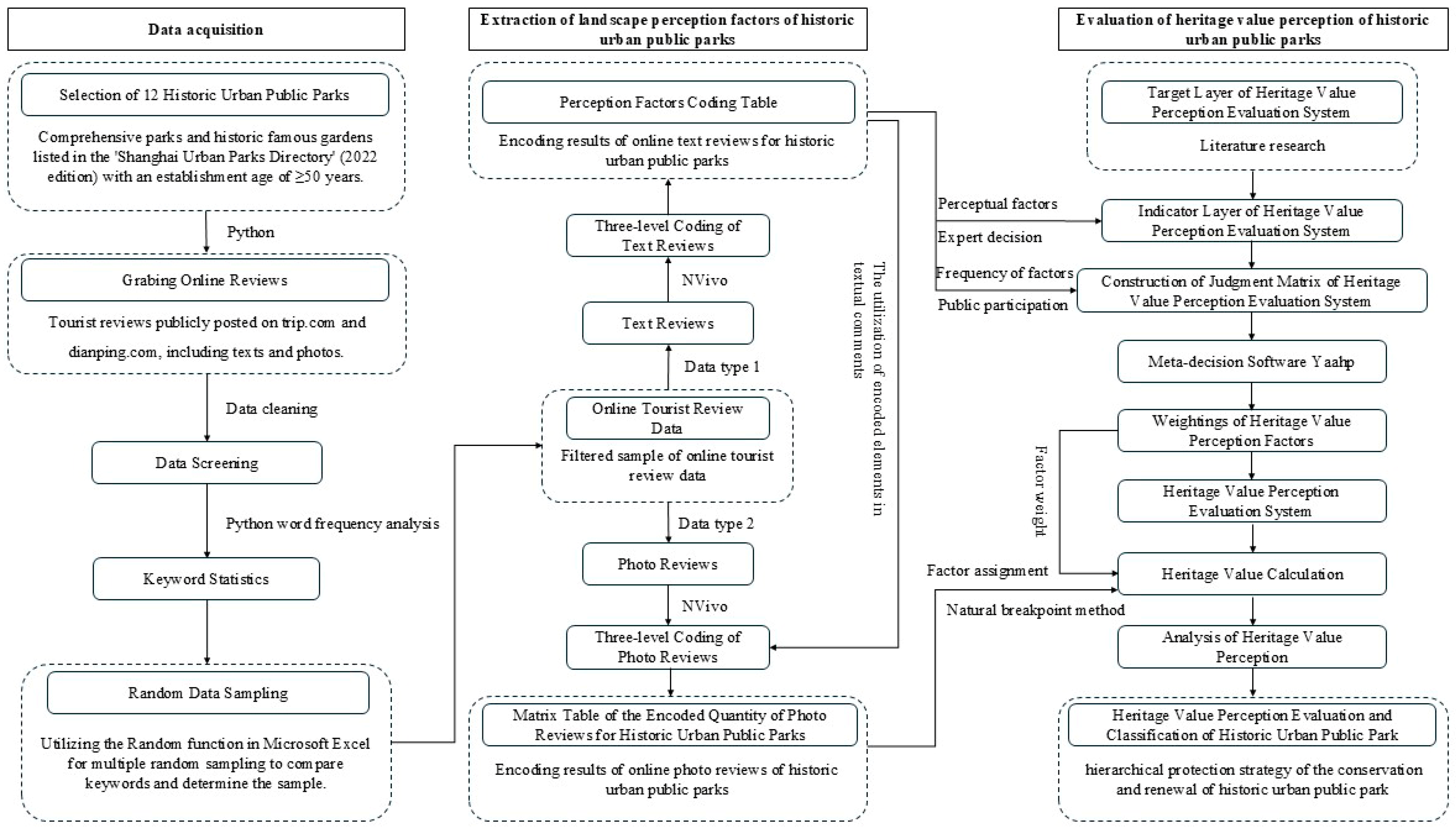

3.2. Determination of Criterion Layer and Indicator Layer for the Evaluation System

Based on a comprehensive review of the literature (Table 1) and expert consultations, a criterion layer comprising four dimensions—ecological, historical, social, and spiritual values—was constructed. This aligns with the definition of heritage value in the “Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Relics in China”.

The indicator layer of the evaluation system was constructed based on Table 3. To enhance the authority of the evaluation system, this study employed the Delphi method to solicit opinions from 5 landscape experts, leading to three rounds of revision and optimization of the evaluation factors. Experts suggested classifying “Traditional Culture” under “Historical Heritage”, “Activity Venues” under “Participatory Entertainment Experiences”, and “Public Welfare Activities” under “Cultural Activity Experiences”.

Finally, the correspondence between 11 criterion-level factors and 35 indicator-level factors was determined, and the structural model of the historic urban public park heritage value perception evaluation system was built using the meta-decision software Yaahp (v10.3) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The structural model of heritage value perception evaluation system of historic urban public park.

4. Calculation of Heritage Value Perception in Historic Urban Public Parks

4.1. Calculation of Online Text Coding Frequency

Based on the evaluation system in Figure 3, the coding frequency for each perception element was calculated using NVivo 12.0. Specifically, the coding frequency represents the proportion of references assigned to each element in relation to the total number of coded references. It was computed using the following formula:

where denotes the coding frequency (%) of perception element i, and represents the number of coded references for element i.

This quantitative approach allows for a comparative assessment of the relative prominence of different perception elements in public discourse.

As shown in Table 4, perception elements related to natural landscape and diverse experiences exhibit the highest coding frequencies, indicating that these categories are most salient in public perception of historic urban parks. In contrast, intangible cultural heritage and traditional media show relatively lower frequencies, suggesting that cultural communication and interpretation still need to be strengthened.

Table 4.

Overview of coding frequencies for cultural heritage value perception elements in historic urban public parks.

4.2. Calculation of Weights for Online Text Coding Perception Elements ()

To quantitatively determine the relative importance of each perception element, this study employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). The AHP is a structured technique for organizing and analyzing complex decisions, widely used to derive ratio-scale weights from qualitative or empirical comparisons [19,20].

In line with the research objective—to evaluate public perception of heritage value in historic urban parks—this study integrates AHP with text-based coding frequency analysis. Traditional expert-based AHP often introduces subjectivity and may not fully reflect collective perceptions. Therefore, the coding frequencies () calculated in Section 4.1 using NVivo 12.0 were adopted as an objective data source to construct the pairwise comparison matrices.

Specifically, the relative importance between any two elements was determined based on their normalized coding frequencies. For example, when comparing B11 (Intangible cultural heritage) with B12 (Historical relic), the coding frequency for “Intangible cultural heritage” in Table 4 is 0.23, and that for “Historical relic” is 1.06. The ratio 0.23/1.06 ≈ 1/5, indicating that B12 is about five times more prominent in online perception. Thus, in the pairwise judgment matrix, B11/B12 = 1/5. This process was repeated for all perception elements to construct judgment matrices for each category.

- (1)

- Determination of Calculation Steps

This study employs the square root method to calculate the weightings () of evaluation factors at each level. Taking the judgment matrix as an example, the specific calculation steps are as follows:

- ①

- Multiply the factors in each row of the judgment matrix continuously and then take the nth root to obtain the geometric mean Mi for each row:

- ②

- Normalize the geometric mean Mi and calculate the weight coefficients Wi for each factor:

- ③

- Calculate the maximum eigenvalue λmax of the corresponding judgment matrix:

- ④

- Calculate the consistency index :

- ⑤

- Calculate the consistency ratio :

Consistency Ratio . When < 0.1, it indicates that the judgment matrix passes the consistency test, and evaluation indicator weightings can be calculated. Otherwise, it is necessary to reconstruct the judgment matrix.

is the average value of the consistency index obtained by inputting random values from 1 to 9 and their reciprocals into the judgment matrix. Saaty and his colleagues derived the indices for judgment matrices of different orders after thousands of calculations (Table 5).

Table 5.

Average random consistency index (RI).

- (2)

- The consistency test of the judgment matrices of the evaluation factors

To ensure analytical rigor, the square root method was employed to calculate the weights () of evaluation factors at each level, following the standard AHP procedure. Consistency tests were performed using Yaahp 10.3 software. The consistency ratio () values for all matrices were below 0.1, indicating satisfactory consistency.

- (3)

- The weightings of perception factors of text coding

As a result, the final weighting structure demonstrates that among the heritage values of the 12 historic urban public parks in Shanghai, ecological value accounts for 28.65%, historical value 17.03%, social value 34.07%, and spiritual value 20.26% (Table 6). This quantitative outcome reflects both the hierarchical structure of perception elements and the actual prominence of these elements in public discourse, providing a robust basis for subsequent evaluation and discussion.

Table 6.

Overview of weights for cultural heritage value perception elements in historic urban public parks.

4.3. Construction of Online Image Coding Quantity Matrix and Calculation of Perception Element Scores (Xi)

To improve the reliability and validity of the evaluation of cultural heritage value perception, this study adopts a dual-coding approach integrating both text and image data. Tourist photographs can directly reflect visitors’ visual attention and emotional preferences, as the depicted landscape elements represent the parts of the park that visitors actually experience and consider valuable during their trips.

- (1)

- Image Coding Procedures

Based on the perception elements summarized in Table 4, a total of 6800 tourist photos were analyzed using NVivo 12.0, and three-level hierarchical coding was conducted. Given the complexity and interrelatedness of the landscape elements, a rigorous coding rule was established: each photograph was limited to a maximum of three second-level codes to ensure accuracy and efficiency. Following this rule, 10,266 coding points were ultimately obtained.

The image coding process in NVivo followed the same logic as text coding, involving classification, comparison, and aggregation of perception elements, and therefore the detailed coding steps are not repeated here.

- (2)

- Construction of the Image Coding Matrix

After coding all the photos, the “Matrix Coding Query” function in NVivo 12.0 was used to establish the Image Coding Quantity Matrix. Specifically, 35 s-level factors were set as the rows, and the 12 historic urban parks as the columns. This process resulted in a 35 × 12 “Park–Perception Element” matrix, where each cell represents the number of times a given perception element appeared in the photos of a specific park (see Table 7 for an excerpt). This matrix provides a clear quantitative representation of the relationship between landscape features and perceived cultural heritage value.

Table 7.

Excerpt of the image comment coding quantity matrix for 12 urban historic parks.

- (3)

- Scoring Criteria and Value Assignment

Based on the coding results, a total of 420 unique codes were obtained from the 12 parks. To translate these numerical frequencies into meaningful perceptual value levels, the Natural Breakpoint Method (Jenks optimization) was applied to divide the data into five intervals according to the distribution of code frequencies. This method minimizes within-group variance and maximizes between-group variance, ensuring a scientifically sound categorization of perception intensity.

The five resulting levels correspond to “Low”, “Relatively Low”, “Moderate”, “Relatively High”, and “High” value perception, as shown in Table 8. Each level was assigned a corresponding relative score to establish a standardized evaluation framework.

Table 8.

Assignment criteria for image coding perception elements.

Following this scoring system, the 35 × 12 Image Coding Quantity Matrix was re-scored, and the data were reorganized by heritage value category. This resulted in the Image Coding Perception Element Scores (), as presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Scores of image coding perception elements (Xi).

In this framework, low-value perception corresponds to elements rarely represented in tourists’ photos (e.g., neglected or less recognizable heritage features), while high-value perception indicates elements that appear frequently and attract strong visual or emotional attention (e.g., iconic scenery, symbolic structures, or interactive spaces). A comparative analysis illustrates the contrast between low-value and high-value images, showing that high-value images typically feature recognizable landmarks, rich vegetation, and active public engagement, whereas low-value images generally lack cultural distinctiveness or environmental quality.

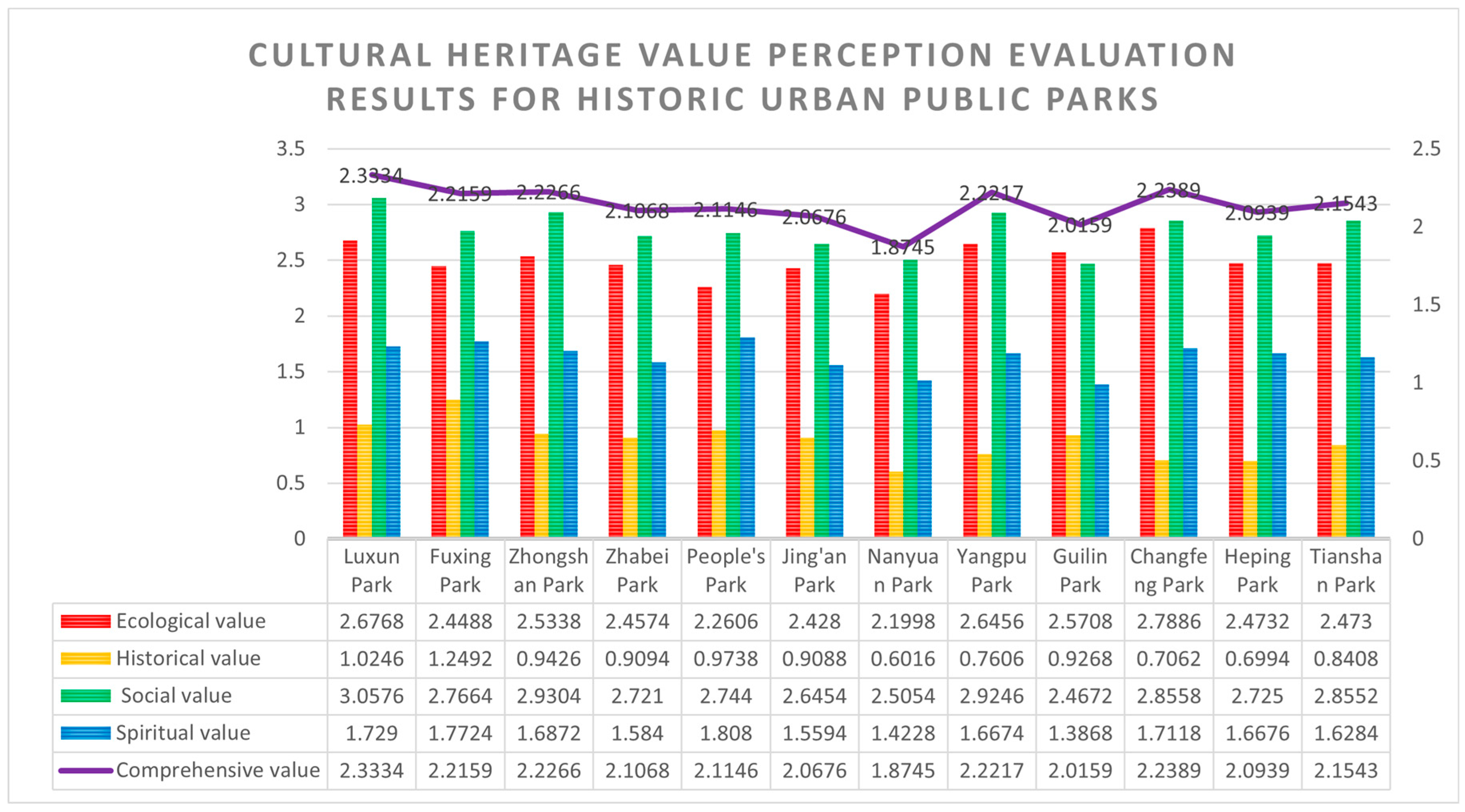

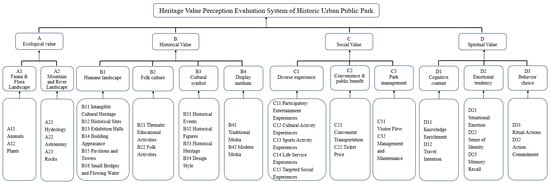

4.4. Calculation Results of Heritage Value Perception in Historic Urban Public Parks

The perception element weights Wi obtained from online text coding in Table 6, and the perception element scores obtained from online image coding in Table 9, are substituted into the additive model to calculate various cultural heritage values [21]:

Furthermore, by combining the ecological value, historical value, social value, and spiritual value of each of the 12 parks with the previously derived weights for cultural heritage value perception (i.e., ecological value weight of 0.2865, historical value weight of 0.1703, social value weight of 0.3407, and spiritual value weight of 0.2026), the comprehensive heritage value V for each park is obtained:

Finally, by substituting the perception element values of the 12 historic urban public parks in Shanghai one by one, the perception results of cultural heritage value for each historic urban public park are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of cultural heritage value perception evaluation results for historic urban public parks.

5. Results

5.1. Perception Analysis of Cultural Heritage Value in Urban Historic Parks

According to the ecological value ranking, Changfeng Park ranks first in perceived ecological value, followed by Luxun, Yangpu, and Guilin Parks. However, a comparison with actual greening data reveals a partial mismatch between public perception and objective conditions. While high-perception parks such as Changfeng and Luxun show vegetation coverage rates around 80%, some parks with similar or even higher greening ratios—such as People’s Park (76%)—receive lower ecological perception scores. This indicates that perceived ecological quality depends not only on physical greenery but also on the visibility, accessibility, and interpretive communication of natural features. Enhancing ecological interpretation, optimizing vegetation design, and expanding environmental education can help bridge this gap between perception and reality.

Based on the historical value ranking, Fuxing Park firmly holds the top position due to its unique status as a blend of modern Chinese and Western garden art. Its predecessor was Gu Family Garden, which was transformed by the French designer Papot, integrating the essence of French classical gardens to form a multi-layered cultural space. In contrast, parks such as Heping, Changfeng, and Nanyuan have weak value perception due to incomplete preservation of historical elements or narrative discontinuities. Although historical value ranks third among the four dimensions, public attention is relatively low, mainly due to single traditional display methods, insufficient digital application, and lack of activation means. As carriers of urban memory, historic parks are recommended to deepen cultural connotations, innovate digital restoration technologies, design thematic narrative activities, and leverage new media to build interactive communication mechanisms, promoting a shift from static display to dynamic inheritance.

According to the social value ranking, Luxun Park (Hongkou Park) ranks first, relying on its advantageous location and composite functions. Located in the core area of Hongkou, it boasts convenient transportation. As China’s first sports-themed park, it is equipped with badminton courts, children’s playgrounds, and other facilities for all ages, and forms a cultural tourism linkage with Hongkou Football Stadium, becoming a landmark for citizens’ leisure. In contrast, although Guilin Park is known for its osmanthus landscape, its fitness space is limited; Nanyuan and Jing’an Parks have low social value recognition due to similar problems. As core carriers of urban public life, the overall social value of the 12 historic parks ranks highest, but there are shortcomings such as functional singularity and insufficient space utilization. In the future, it is necessary to promote innovation in the “park+” model, strengthen multi-stakeholder collaboration and spatial optimization, and transform parks into urban vitality nodes integrating ecology, culture, and social interaction by implanting cultural IPs, expanding fitness scenarios, and improving service facilities, thereby achieving a dynamic balance between historical protection and contemporary needs.

Based on the spiritual value ranking, People’s Park and Zhongshan Park rank among the top, relying on their century-old history and diverse functions. As landmarks of urban change, their historical relics and natural landscapes form public education spaces, contributing to patriotism education and ecological cognition for adolescents, while also alleviating citizens’ mental stress as urban oases. Special activities such as People’s Park’s matchmaking corner trigger discussions on traditional and modern values through social and cultural phenomena. In contrast, Jing’an, Nanyuan, and Guilin Parks have weaker spiritual value perception due to limited area, narrative discontinuities, and fragmented activities, leading to superficial cultural experiences for tourists. Data show that although the spiritual value dimension accounts for a high proportion, public perception of historical connotations still has shortcomings, and participation needs to be enhanced through a series of thematic activities and contemporary interpretations. In the future, it is necessary to strengthen cultural communication, build parks into a two-way carrier of collective memory and urban spirit, and achieve deep integration of living heritage and public emotional resonance.

According to the comprehensive value ranking, Luxun Park, as Shanghai’s first sports-themed park and a historical and cultural carrier, ranks first with its profound heritage and landscape layout. Changfeng Park (landscape pattern), Zhongshan Park (century-old culture), and Yangpu Park (industrial heritage) rank second to fourth, respectively, forming differentiated competitiveness with their ecological and humanistic characteristics. Jing’an, Nanyuan, and Guilin Parks rank lower due to ecological monotony, weak historical narratives, and management shortcomings, exposing common challenges in urban parks regarding ecological experience, cultural excavation, and public participation. The study found that park value perception is influenced by ecological diversity, depth of historical interpretation, functional complexity, and refinement of management. It is necessary to strengthen the habitat function of organisms through ecological restoration, excavate historical contexts to build immersive narrative scenarios, add interactive devices and smart guidance to enhance participation, and optimize spatial operations to achieve the integration of “culture + ecology + service”, thereby reshaping the comprehensive value of parks as carriers of urban memory and core nodes of public life.

5.2. Hierarchical Management and Distinctive Conservation Strategies for Historic Urban Public Parks

Based on the calculation results from the previous section (Figure 3), the 12 historic urban public parks are classified according to the geometric mean values of their ecological, historical, social, and spiritual values as qualification standards (i.e., ecological value ≥ 2.4964, historical value ≥ 0.8787, social value ≥ 2.7665, spiritual value ≥ 1.6354), resulting in the Hierarchical Classification Table for Cultural Heritage Value Perception of Historic Urban Public Parks (Table 10).

Table 10.

Hierarchical classification table for cultural heritage value perception of historic urban public parks.

The historic urban public park value assessment system, based on three core dimensions—protection, sustainable development, and cultural perception—establishes a four-level classified management mechanism. First-level value points must meet all three standards, indicating complete protection mechanisms, effective ecological maintenance, and prominent cultural experiences, with a focus on strengthening innovative practices such as smart perception platforms and low-carbon facility renewal. Second-level value points meet two standards, consolidating advantages and specifically improving shortcomings, such as optimizing ecological restoration technologies or expanding cultural dissemination channels through interactive digital tools. Third-level value points meet only one indicator, focusing on capital injection, management optimization, or public participation to achieve breakthroughs. Fourth-level value points do not meet the standards and require systematic diagnosis, cross-departmental collaboration to integrate resources, and systematic transformation.

This hierarchical system emphasizes dynamic monitoring and precise policies, allowing for differentiated management based on value levels, and constructing a systematic plan of “protection-activation-enhancement” to provide scientific decision-making basis for the balance between park protection and development. To implement the hierarchical framework more effectively, a series of distinctive conservation and renewal strategies are proposed:

- (1)

- First-level value parks: Collaborative protection and intelligent perception.

Establish a “historical layering + community co-governance” model, supported by smart perception platforms (mobile apps or WeChat (v8.0.55) mini programs) that collect visitor feedback (text, photos, emotion tags) to visualize real-time public sentiment. Digital twin technology is used to monitor both ecological and cultural indicators, forming a closed loop of “living protection–value dissemination–community benefit” that enhances cultural belonging and shared stewardship.

- (2)

- Second- and third-level value parks: Targeted restoration and experiential enhancement.

Develop a “value anchor + functional adaptation” mechanism that integrates historical preservation with cultural innovation. Differentiated management is applied—cultural-type parks emphasize narrative storytelling and digital interaction, while ecological-type parks enhance habitat connectivity. Introduce Three-Dimensional Engagement Models (Community + Narrative + Digital Interaction) such as AR-based storytelling routes connecting historic figures, architecture, and ecological nodes, thereby transforming passive sightseeing into participatory learning.

- (3)

- Fourth-level value parks: Regeneration and digital transformation.

Implement a “problem list + dynamic evaluation” system with structural safety assessments, cultural gene mapping, and modular upgrading. Behavioral data and big-data platforms for visitor experience inform layout optimization, while dedicated restoration funds and EPC+O operation models promote efficient management.

Through these adaptive and data-driven strategies, the “3E” management framework (Ecology + Experience + Engagement) integrates ecological restoration, immersive visitor experience, and participatory governance. This approach transforms historic urban parks from static conservation zones into living cultural spaces, enabling sustainable heritage revitalization aligned with contemporary urban lifestyles.

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparison with Other Locations

The results indicate that in Shanghai’s twelve historic urban public parks, social value—including elements such as participation in recreation, public service, and social activities—ranks highest among perceived heritage dimensions. This aligns with international findings emphasizing the growing importance of social interaction and everyday experience in urban park perception.

For example, a social media-based study of the Twin Cities in the United States revealed that accessibility, landscape diversity, and recreational amenities were key determinants of park visitation frequency and user satisfaction [22]. Similarly, an analysis of user-generated content from New York City’s Bryant Park demonstrated that “public events”, “comfort”, and “community atmosphere” were among the most frequently mentioned themes reflecting positive emotional experiences [23].

In contrast, research in Europe and Japan has traditionally emphasized material authenticity and historical continuity as the primary dimensions of heritage value [24,25]. The findings of this study, however, underscore how digital participation and social engagement reshape heritage perception in contemporary urban contexts. Rather than focusing solely on object-based preservation, Shanghai’s historic parks illustrate how public memory and informal everyday use sustain living heritage—reflecting a conceptual shift toward experience-based perception.

6.2. Specific Contributions and Implications

This research contributes both methodologically and practically to the field of cultural heritage management.

- (1)

- Methodological contribution:

The study integrates online text coding, image-based content analysis, and AHP-derived weighting into a hybrid quantitative framework. This approach is consistent with emerging research in data-driven cultural analytics, which employs social media data to evaluate public perceptions of urban heritage and landscape [22,26].

- (2)

- Practical contribution:

Based on the derived value hierarchy, the research proposes a graded management mechanism that differentiates protection priorities across ecological, historical, social, and spiritual dimensions. This system enables decision-makers to design targeted conservation and interpretation strategies rather than applying a uniform model.

Furthermore, by integrating digital participatory data—including user-generated images and comments—this study resonates with global research trends that use large-scale participatory datasets to evaluate heritage landscapes [23,26]. It thus expands the analytical toolkit for cross-cultural comparison of heritage perception and offers new insights into the intersection between heritage value and digital engagement.

6.3. Research Limitations

Despite the study’s comprehensive methodological integration, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the research focuses exclusively on twelve historic urban parks in Shanghai, without including classical gardens or other heritage landscapes, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings across different regional or typological contexts. Second, the use of social media and online comment data inherently introduces sampling bias, as such platforms primarily reflect the voices of digitally active users—while groups such as the elderly, children, or infrequent park visitors may be underrepresented. Third, the temporal coverage of the dataset—approximately three years—limits the capacity to observe long-term or seasonal shifts in public perception. Finally, although NVivo-assisted text analysis and frequency-weighted coding were employed to enhance reliability, qualitative interpretation inevitably involves elements of subjectivity.

Future studies should extend the comparative framework to multiple cities and park types, integrate traditional survey methods with AI-based image recognition, and apply time-series analysis to capture the dynamic evolution of public perception toward cultural heritage over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T. and Y.Z.; methodology, Z.T. and Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Z.T. and Y.Z.; investigation, Z.T. and Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.T. and Y.Z.; visualization, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Planning Youth Project, grant number 2019ECK010, and the Ministry of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Fund, grant number 22YJC760011.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to everyone who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. There are no relevant financial or non-financial relationships to be disclosed.

References

- International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS. Document on Historic Urban Public Parks; International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.M. Contemporary British Architectural Heritage Protection; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.P.; Chen, L.P. Historical Park Renewal Strategies Based on Heritage Value Assessment. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 28, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS. The Athens Charter; International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1931; Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/1931-the-athens-charter/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Daniel, N.; Yang, R. Heritage Protection: Cultural Landscape and the American Landscape Architecture Industry. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 25, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Australia International Council on Monuments and Sites—Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter; Australia International Council on Monuments and Sites—Australia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 1999; Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/BURRA-CHARTER-1999_charter-only.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Anonymous. New Edition of “Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Relics in China” Released. Urban Plan. Forum 2015, 4, 121–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, G.Q. Value Construction and Interpretation. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wu, C. Analysis of the Value System of Chinese Cultural Heritage—Based on the Characteristics, Relationships and Local Context of Value. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2019, 1, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, E.; Legwaila, I. Visual Landscape Research—Overview and Outlook. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Boster, R.S. Measuring Landscape Esthetics: The Scenic Beauty Estimation Method; Research Paper RM-167; USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y. Towards Landscape Perception: Inheritance and Development of Landscape Perception and Visual Evaluation. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Bazac, T.; Marin, S.; Olteanu, C.; Hotoi, A. Sustainable Management Decisions for Historic Urban Public Parks: A Case Study Based on Online Referential Values of Carol I Park in Bucharest, Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikaterini, G.; Angeliki, P. Landscape Character Assessment, Perception Surveys of Stakeholders and SWOT Analysis: A Holistic Approach to Historical Public Park Management. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.X.; Chen, Y.X. Cultural Service Perception Evaluation of Urban Historic Park Renewal Based on Affective Computing—Taking Luxun Park Renewal as an Example. J. Tongji Univ. (Soc. Sci. Sect.) 2022, 33, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Local Records Office, Shanghai Greenery Administration Bureau. Shanghai Famous Gardens; Shanghai Pictorial Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2007; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, R.W. The analytic hierarchy process—What it is and how it is used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Labib, A. Selection of new production facilities with the group analytic hierarchy process ordering method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 7317–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Huq, S.; Puthuvayi, B. Assessing the performance of urban heritage conservation projects–influencing factors, aspects and priority weights. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, M.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Wood, S.A.; Fisher, D.M.; Hamstead, Z.A.; McPhearson, T. Using social media to understand drivers of urban park visitation in the Twin Cities, MN. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Fernandez, J.; Wang, T. Understanding perceived site qualities and experiences of urban public spaces: A case study of social media reviews in Bryant Park, New York City. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS. The Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values; International Council on Monuments and Sites—ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.L.; Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.S.; McMillen, H.L. Mapping urban park cultural ecosystem services: A comparison of twitter and semi-structured interview methods. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).