Research on Strategies for Creating an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment in Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

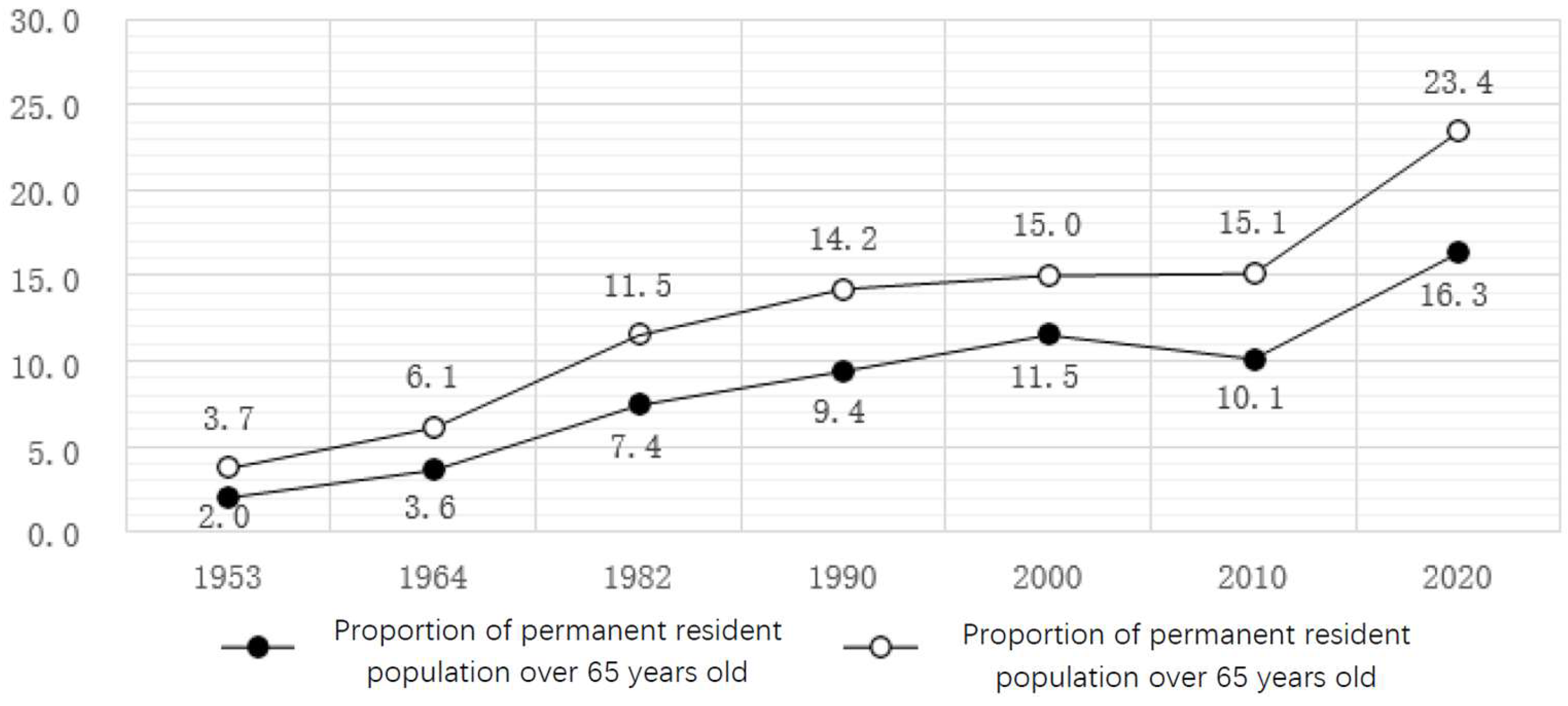

1.1. China’s Aging Population Is Becoming Increasingly Severe

1.2. Age-Friendly Communities

1.3. Community Commercial Restructuring and Transformation

2. Preview Literature on the Topic

2.1. Related Theoretical Research

2.1.1. Research on the Behavioral Activities of the Elderly

2.1.2. Consumer Behavior Space Theory

2.2. Community Commercial Complexes and Age-Friendly Development

3. Study Area and Methods

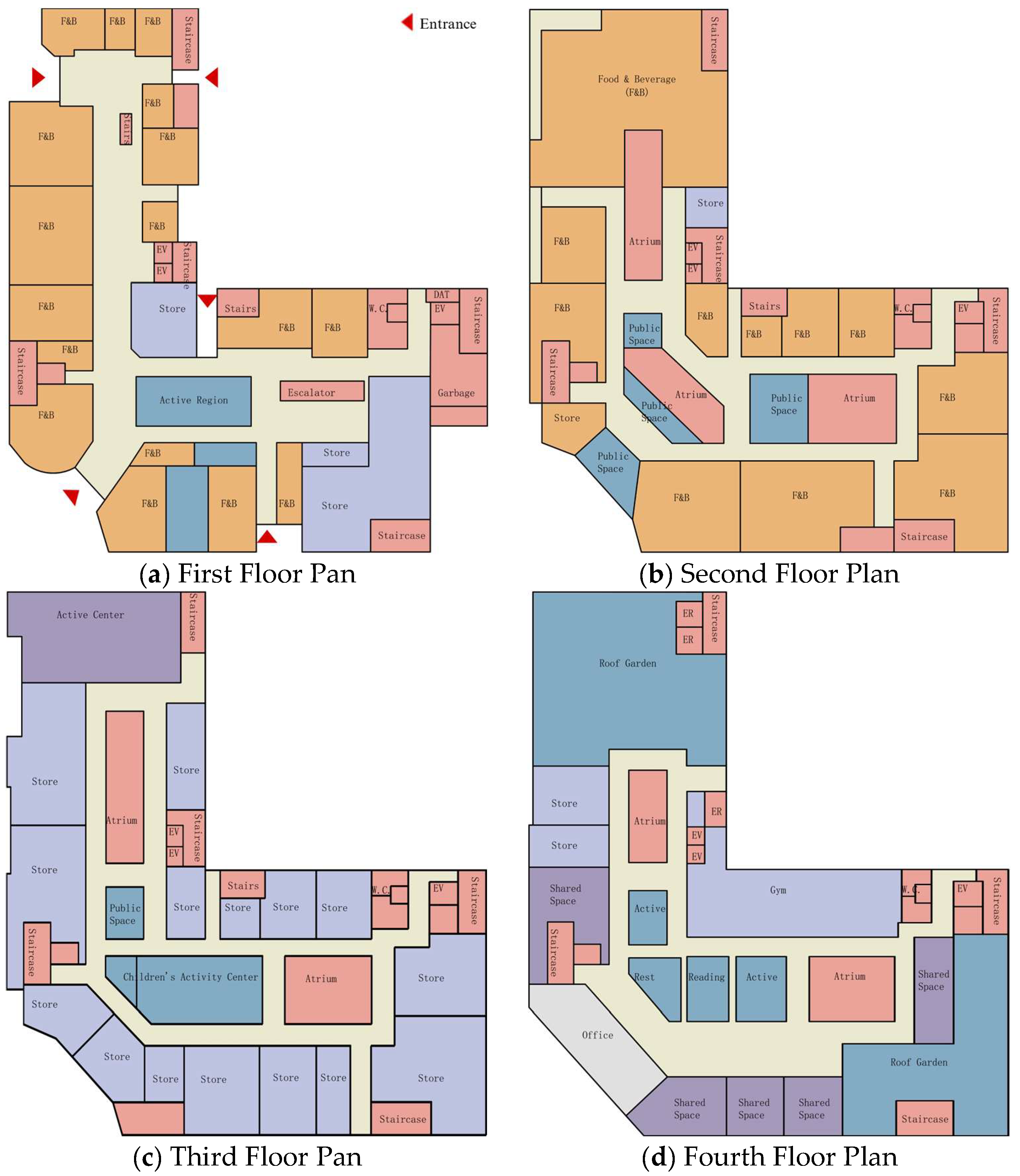

3.1. Site Selection for the Study

3.1.1. Shanghai Exhibits Pronounced Aging Characteristics

3.1.2. Overview of the Development of Community Commercial Complexes

3.2. Research Design and Data Sources

3.3. Research Methods and Analytical Framework

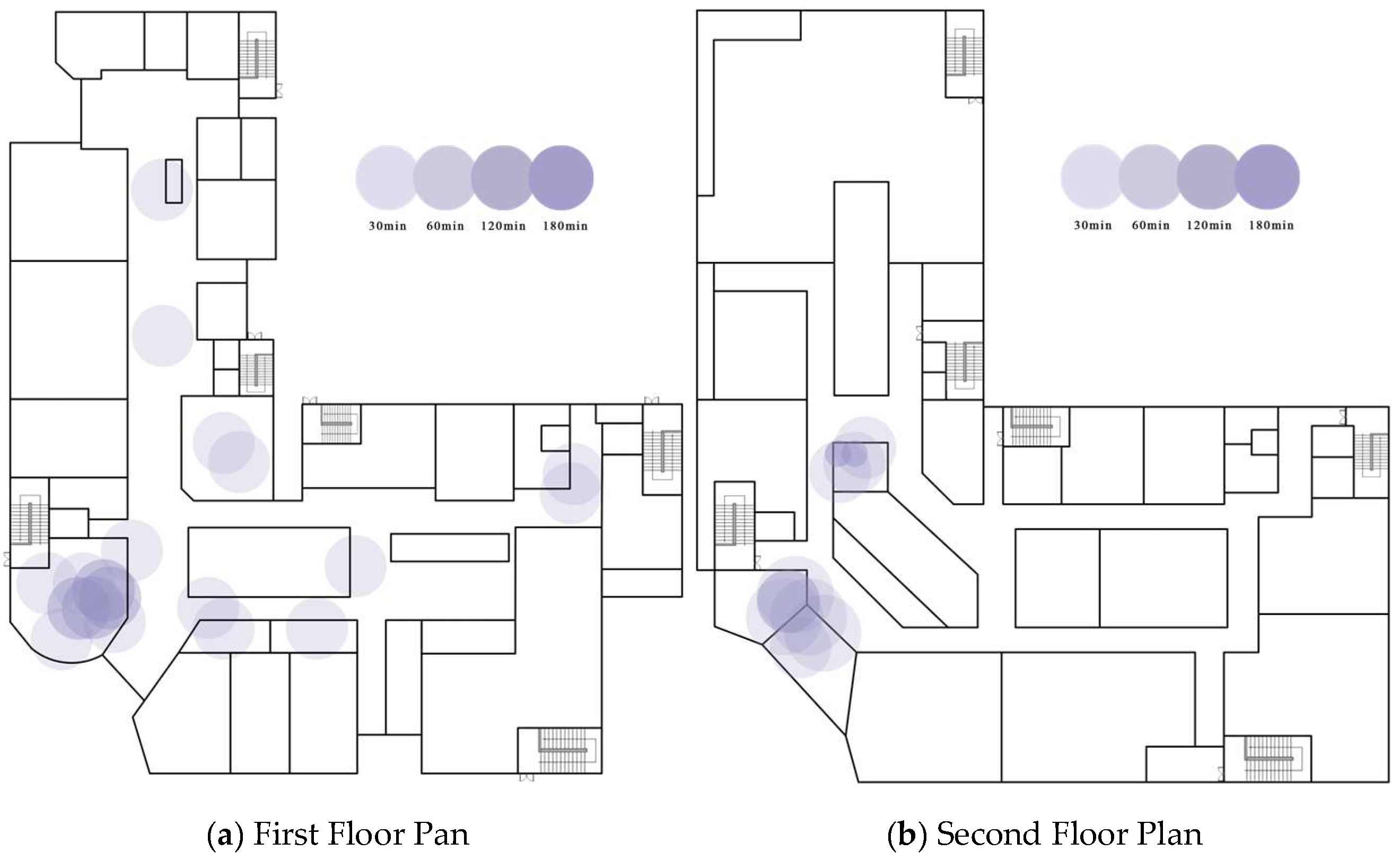

3.3.1. Field Survey and Mapping

3.3.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of Spatiotemporal Behavior

4. Analysis and Results

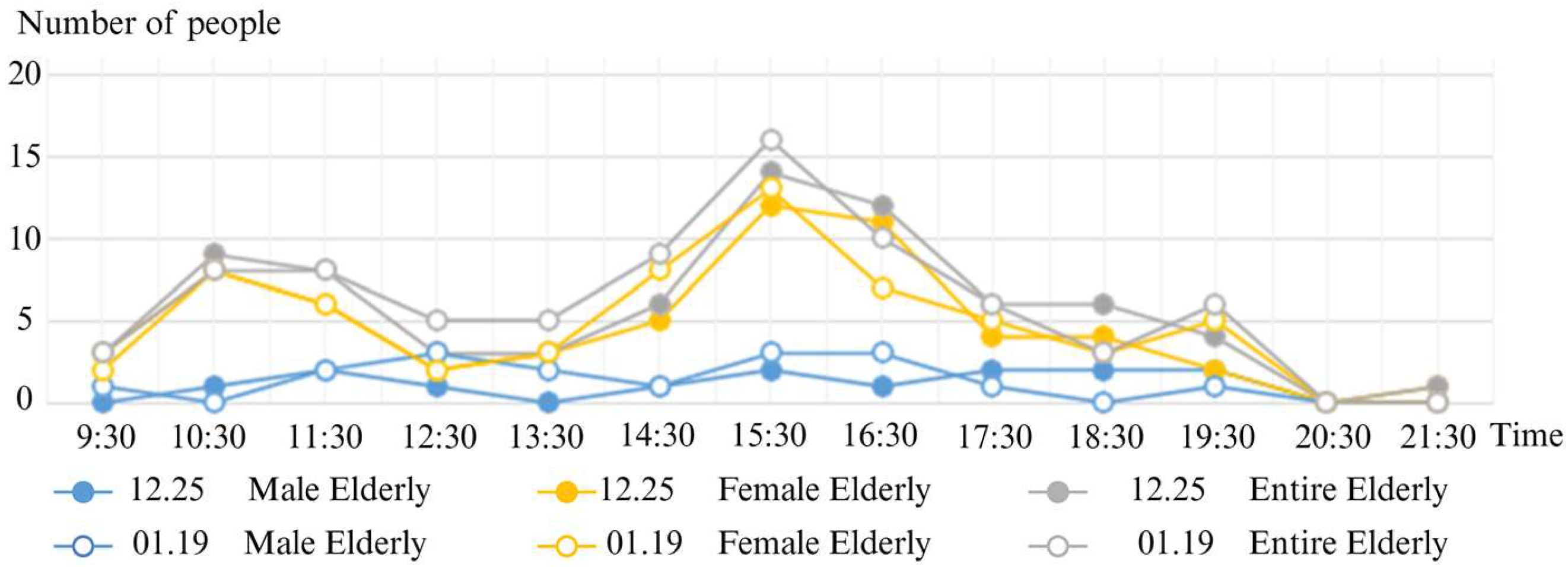

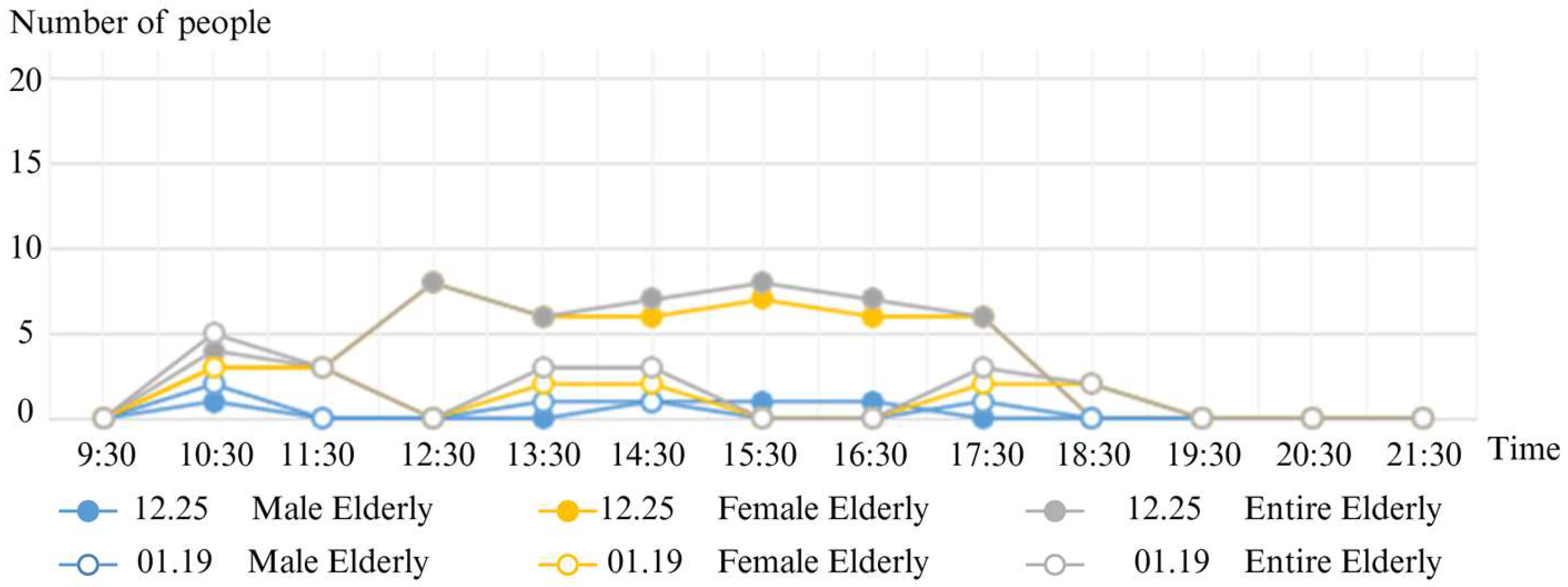

4.1. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Elderly People’s Behavior Patterns

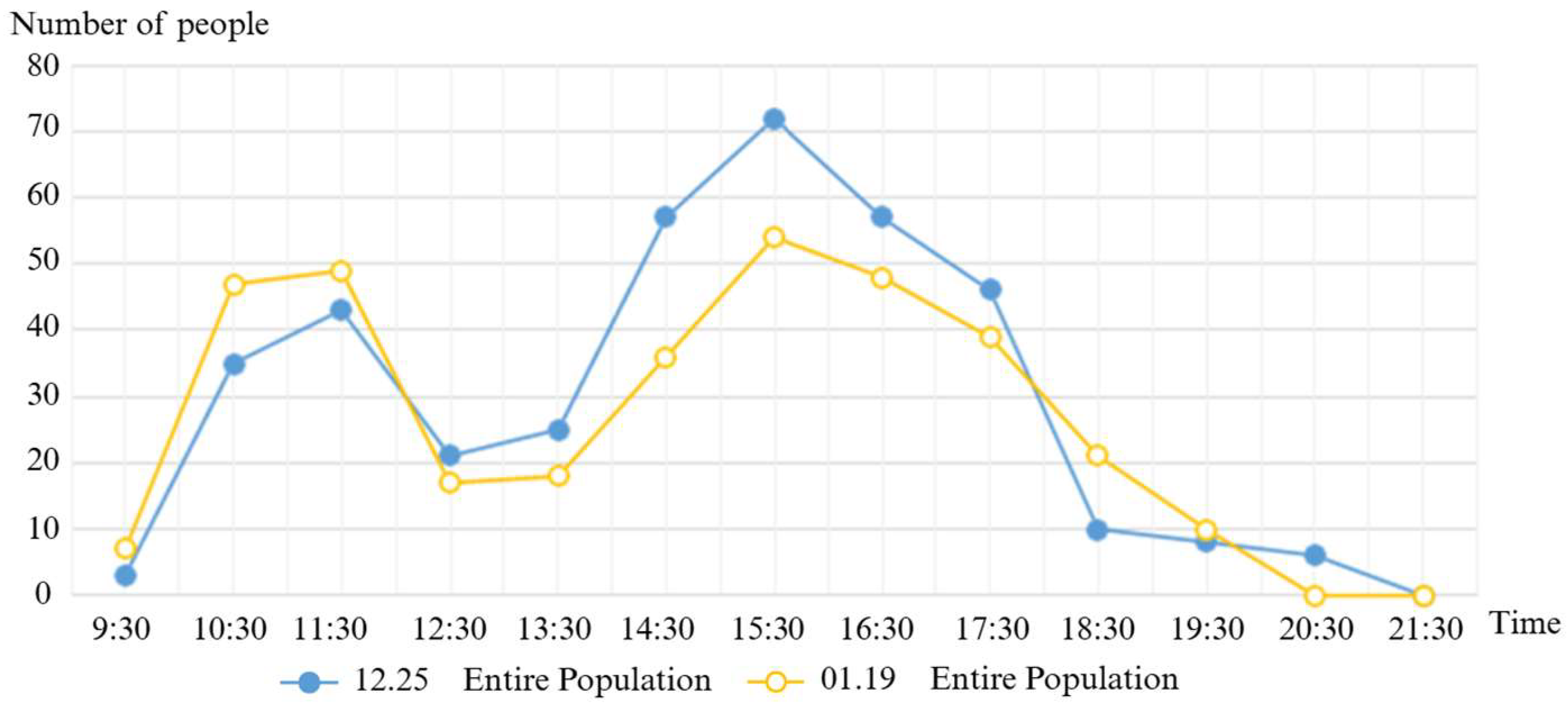

4.1.1. Venue Usage Time Slots

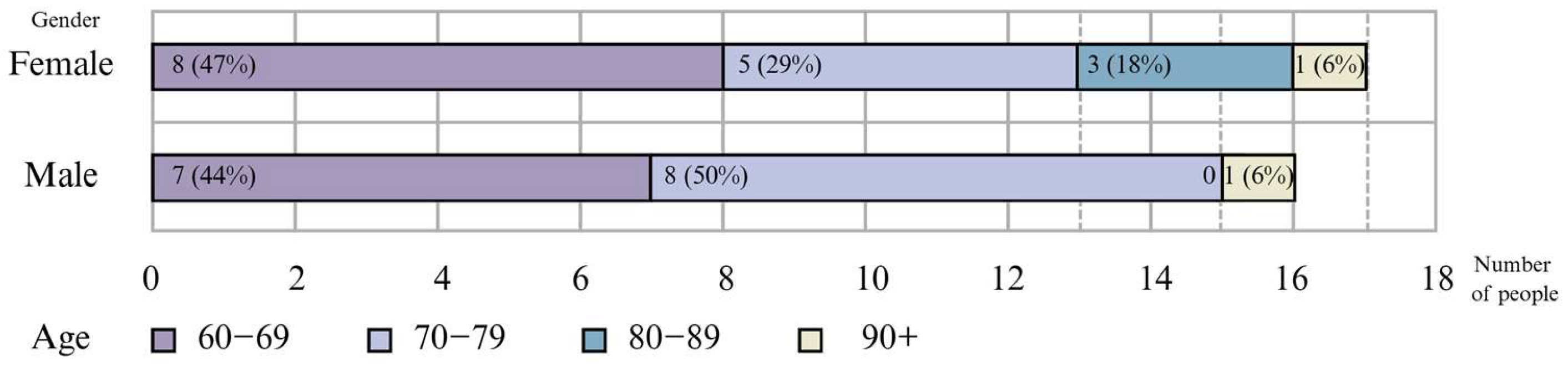

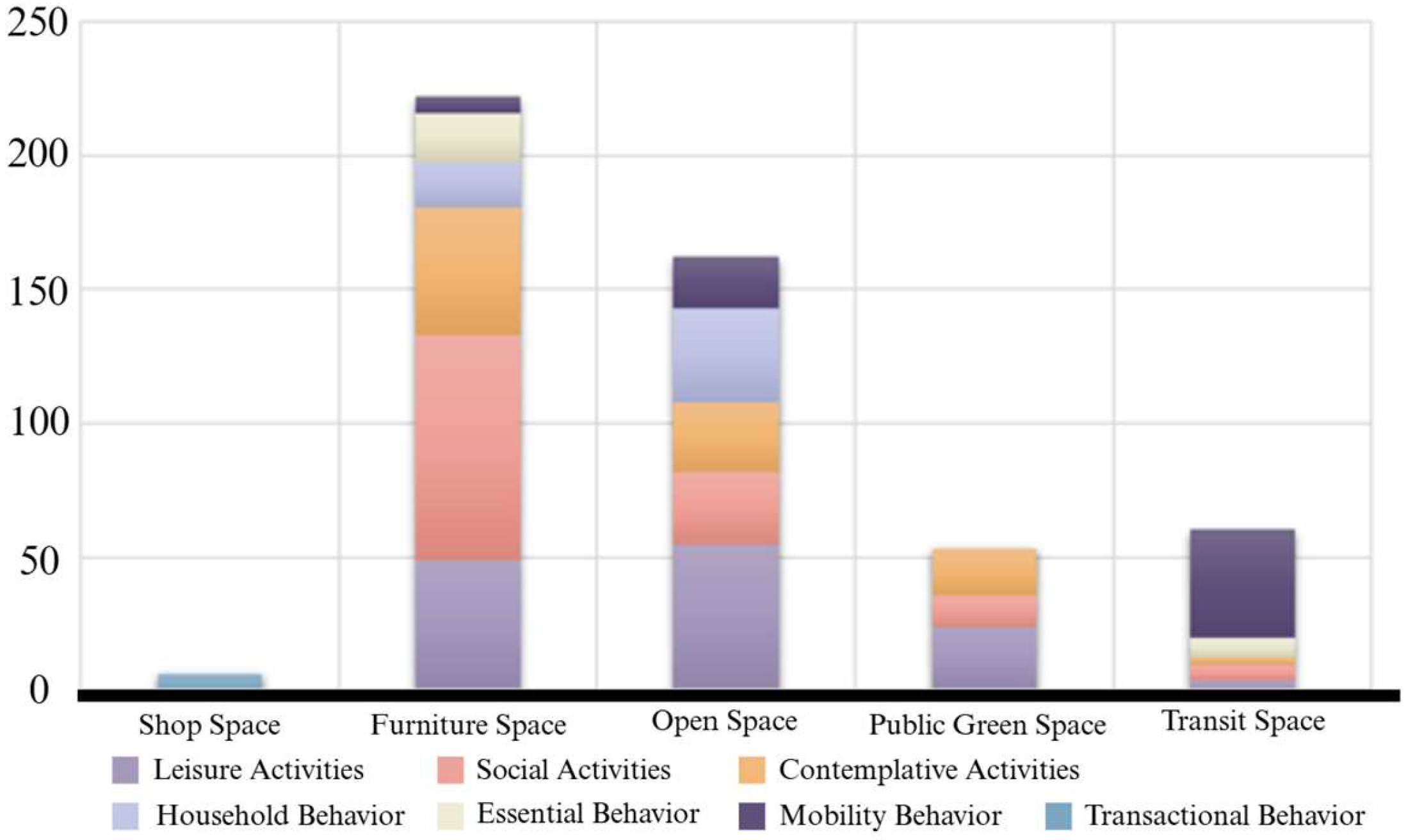

4.1.2. Behavioral Categories of Older Adults

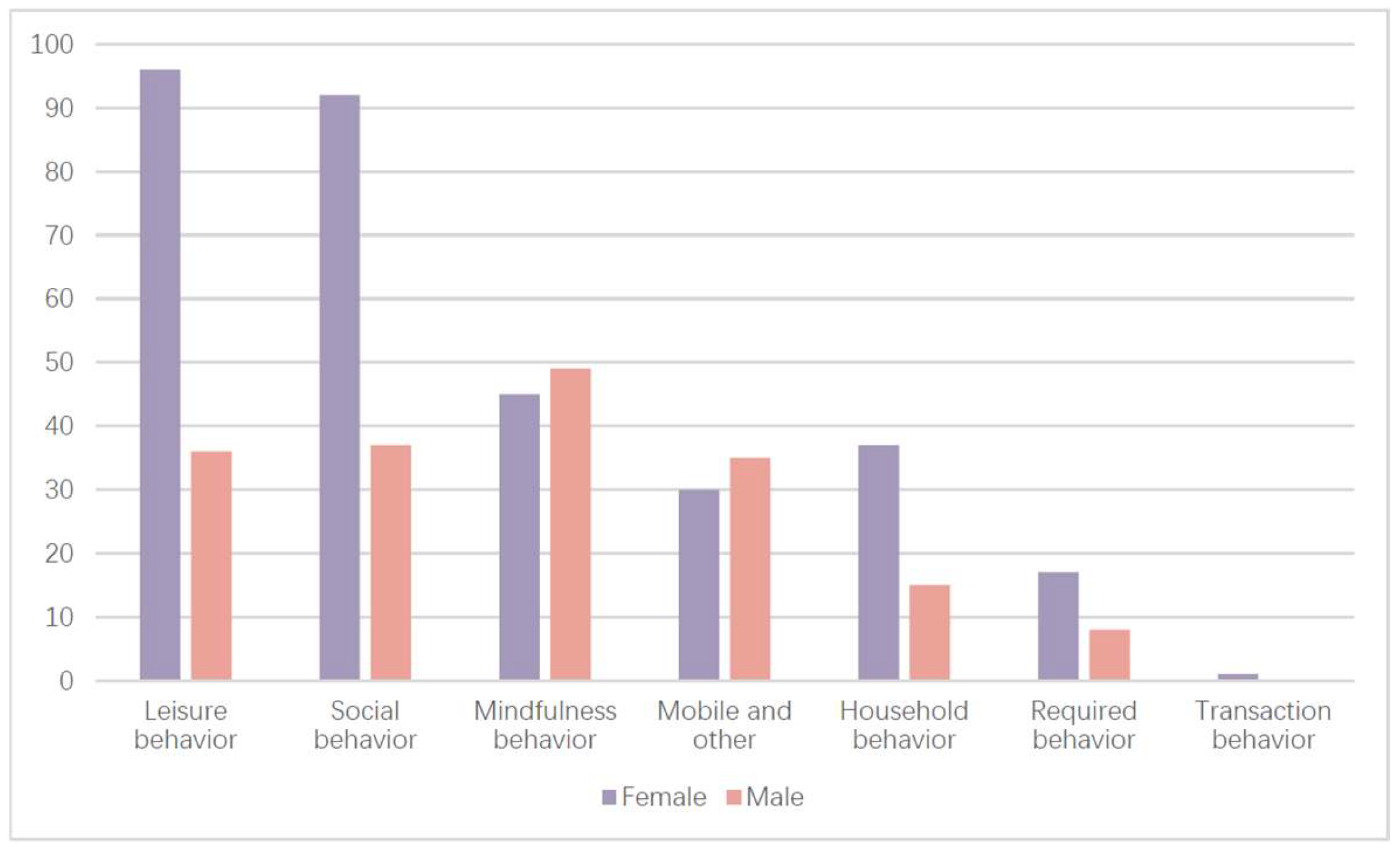

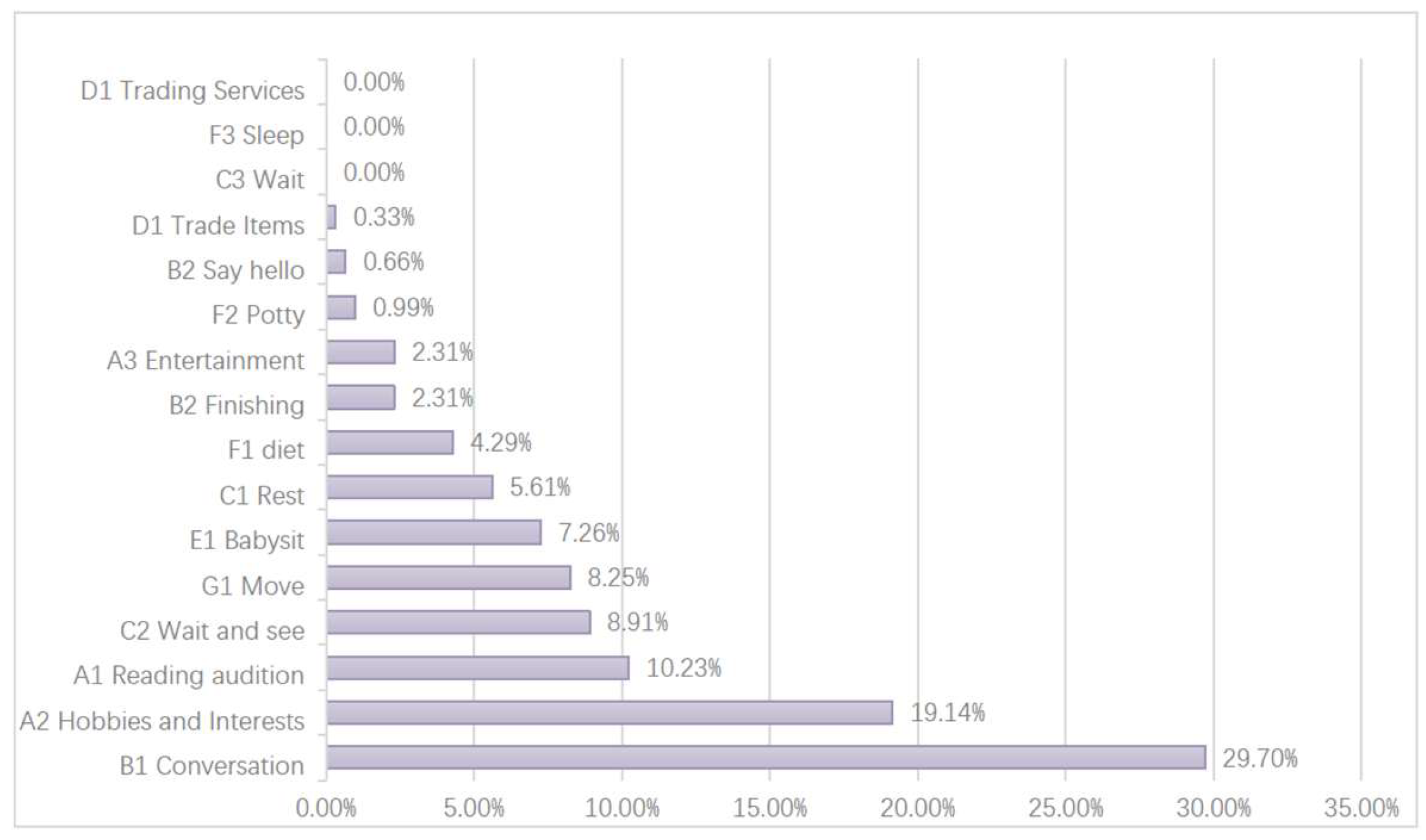

4.1.3. Comparative Analysis of Behavioral Content

4.2. Spatial Choice and Environmental Interaction Analysis of Elderly Behavior

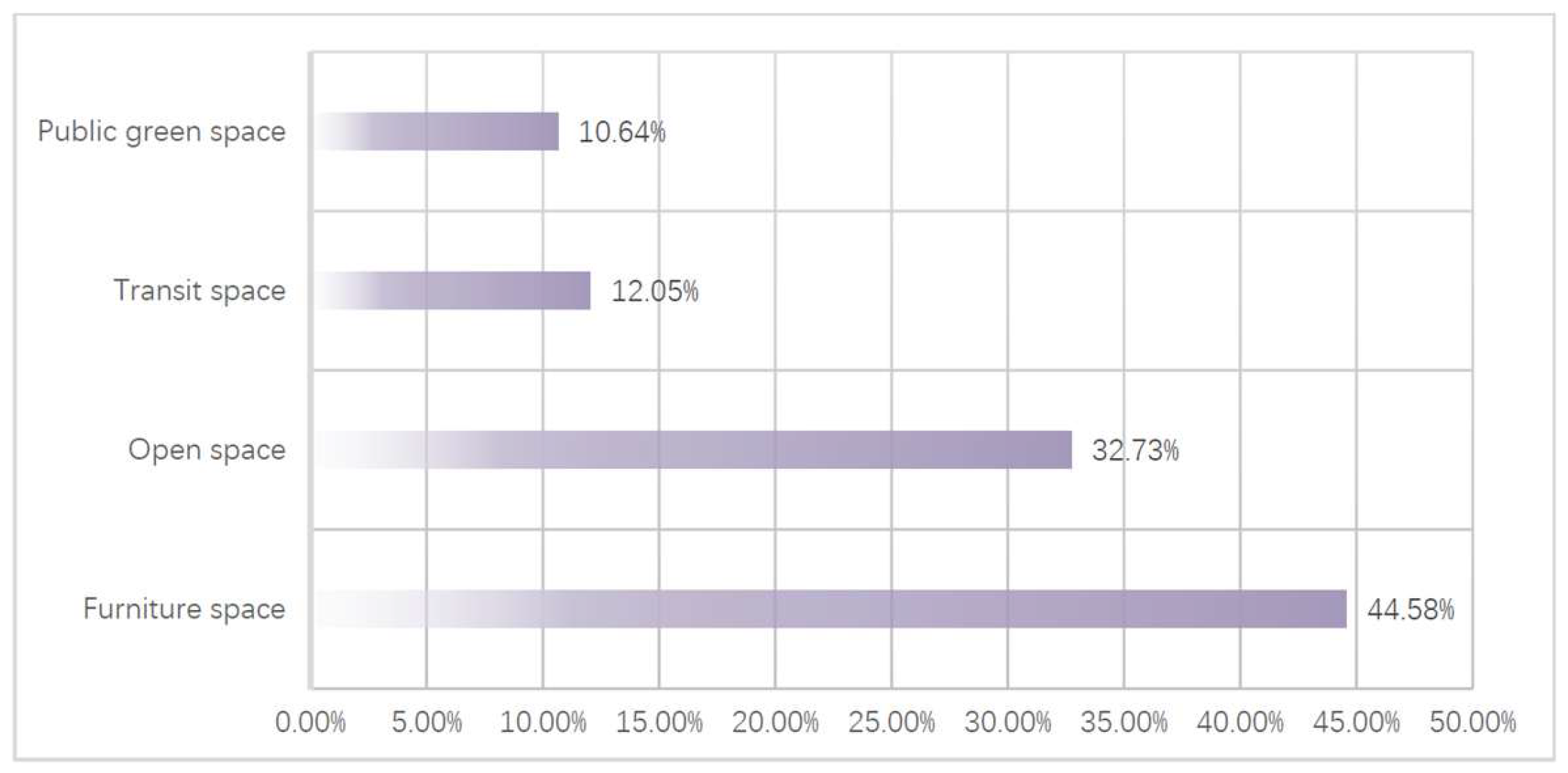

Survey of Spatial Distribution of Elderly Behavior

- (1)

- Publicness

- (2)

- Accessibility

- (3)

- Comfort

4.3. Social Groups and Space Utilization

4.3.1. Types of Social Interaction Among the Elderly

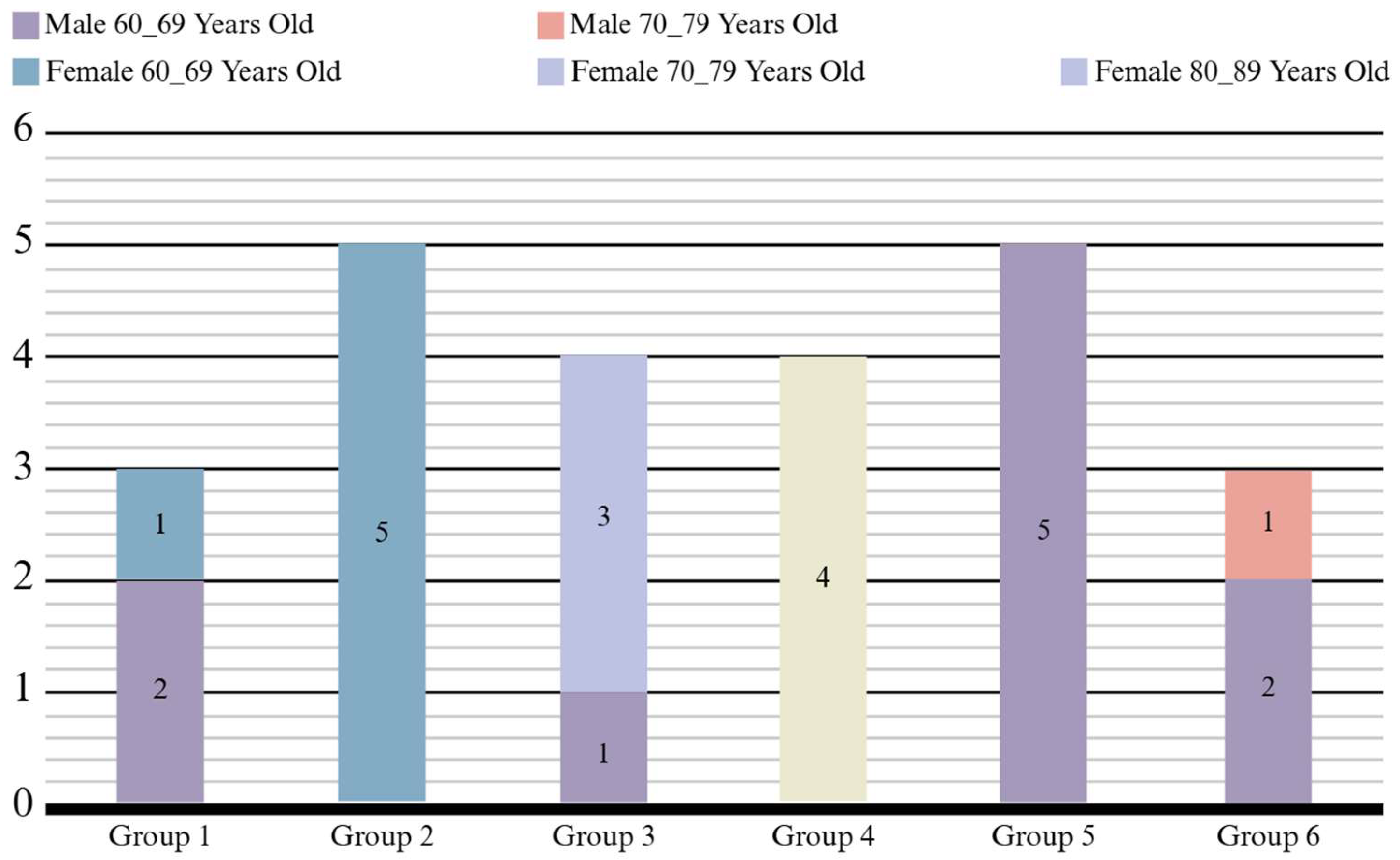

4.3.2. Composition of Social Groups

4.3.3. Implications in the Context of Commercial Complexes

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Issues with the Current Environment

5.2. Recommendations for the Development of an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment

5.2.1. Commercial Business Format Planning for the Elderly

5.2.2. Improving Age-Friendly Supporting Facilities

5.2.3. Creating Communicative Public Spaces

5.2.4. Creating a ‘Family Atmosphere’ in Operations Management

5.3. Research Summary, Contributions, and Outlook

- (1)

- Research Summary

- (2)

- Research Contributions

- (3)

- Research Limitations and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, L. China’s aging population: A review of living arrangement, intergenerational support, and wellbeing. Health Care Sci. 2023, 2, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 5); National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- China Development Research Foundation. China Development Report 2020: Trends and Policies in China’s Population Ageing; China Development Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission & National Working Commission on Aging. Notice on Implementing the Demonstration Creation of National Exemplary Elderly-Friendly Communities; People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-12/14/content_5569385.htm (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Teramoto, S.; Ohga, E.; Ishii, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Mastsuse, T. Reference value of six-minute walking distance in healthy middle-aged and older subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 2000, 15, 1132–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, H. Directions in environmental gerontology: A multidisciplinary field. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Weisman, G.D. Environmental gerontology at the beginning of the new millennium: Reflections on its historical, empirical, and theoretical development. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Christensen, K. (Eds.) Environment and Behavior Studies: Emergence of Intellectual Traditions; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles, G.D. Environmental Gerontology: Making Meaningful Places in Old Age; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Science, explanatory theory and environment-behavior studies. In Theoretical Perspectives in Environment-Behavior Research: Underlying Assumptions, Research Problems, and Methodologies; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 107–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hoh, J.W.T.; Lu, S.; Yin, Y.; Feng, Q.; Dupre, M.E.; Gu, D. Environmental gerontology. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging; Gu, D., Dupre, M.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, S.; Ohmori, N.; Harata, N. Effects of Household Structure on Elderly Grocery Shopping Behavior in Korea. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 92nd Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 January 2013; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hedhli, K.E.; Chebat, J.C.; Sirgy, M.J. Shopping well-being: A study with the elderly in shopping malls. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Teller, C.; Alexander, A.; Floh, A. The attractiveness of a city center shopping environment: Elderly consumers’ perspective. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Y.L.; McGregor, E.M.; Allen, J.; Clarke, P. Safe, affordable, convenient: Environmental features of malls and other public spaces used by older adults for walking. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E102. [Google Scholar]

- Louail, T.; Lenormand, M.; Cantu Ros, O.G.; Picornell, M.; Herranz, R.; Frias-Martinez, E.; Ramasco, J.J.; Barthelemy, M. Shopping mall attraction and social mixing at a city scale. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170717. [Google Scholar]

- Too, L.S.; Lau, S.S.Y. Community participation of community dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, J.; Merrilees, B.; Birch, D. Entertainment-seeking shopping center patrons: The missing segments. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Reutterer, T. The evolving concept of retail attractiveness: What makes retail agglomerations attractive when customers shop at them? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, G. Analysis of Spatial Behavior by Revealed Space Preference. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1969, 59, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, N.; Ganapathi, M. Influence of consumers’ socio-economic characteristics and attitude on purchase intention of green products. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.D.; Chaudhury, H. Home and Identity in Late Life: International Perspectives; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Bower, E.; Lutz, J.; Silva, C.; Gallegos, A.M.; Podgorski, C.A.; Santos, E.J.; Conwell, Y. Strategies to promote social connections among older adults during “social distancing” restrictions. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glei, D.A.; Landau, D.A.; Goldman, N.; Chuang, Y.L.; Rodríguez, G.; Weinstein, M. Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: An analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.D. Prisoners of Space? Exploring the Geographical Experience of Older People; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermans, A.; Van Cleempoel, K. Designing a retail store environment for the mature market: A European perspective. J. Inter. Des. 2010, 35, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Common spaces of multi-commercial complexes from urban sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, E.S.; Rietveld, P. Spatial consumer behavior in small and medium-sized towns. Reg. Stud. 2010, 45, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, T.C.; Shah, B. Impact of store layout on behavior intention: A pilot study in a retail store. NIU Int. J. Hum. Rights 2024, 10, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Community resilience evaluation and construction strategies in the perspective of public health emergencies: A case study of six communities in Nanjing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wang, C.; Li, R. Research on behavioral characteristics of the elderly in suburban villages and strategies for age-friendly adaptation of building spaces based on new time–geography. Buildings 2025, 15, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolrych, R.; Duvurru, J.; Portella, A.; Sixsmith, J.; Menezes, D.; Fisher, J.; Lawthom, R.; Reddy, S.; Datta, A.; Chakravarty, I.; et al. Aging in urban neighborhoods: Exploring place insideness amongst older adults in India, Brazil and the United Kingdom. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 55, 100892. [Google Scholar]

- Clitheroe, H.C.; Stokols, D.; Zmuidzinas, M. Conceptualizing the context of environment and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The role of ICT use in reducing social isolation among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from frail and healthy older adults in Sakai City, Japan. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2284. [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, K.; Kurumatani, N.; Hosoi, H. Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: A community-based longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. B 2018, 73, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H. Modeling consumer perception of public space in shopping centers. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-Y.; Chen, M.-S.; Hibino, H.; Koyama, S.; Zheng, M.-C. Rest facilities at commercial plazas through user behavior perspective. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2009, 8, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarutach, T.; Lerddamrongchai, P.; Lertpradit, N. Behaviors of the elderly at shopping malls and facility management to address their needs. J. Archit. Plan. Res. Stud. (JARS) 2023, 21, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook; Shanghai Statistics Press: Shanghai, China, 2021. Available online: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/tjnj2021e.htm (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Market Analyzer. Shanghai Commercial Complex Report; Market Research Press: Shanghai, China, 2023; Available online: https://www.market-analyzer.com/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Adams, K.B.; Leibbrandt, S.; Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Operating Area | Operating Area Share | Sales Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2.24 | 53.59% | 31.41% |

| 2018 | 3.35 | 56.88% | 32.87% |

| 2011 | 4.19 | 57.32% | 37.71% |

| 2014 | 5.18 | 57.56% | 38.89% |

| 2017 | 6.60 | 59.95% | 40.16% |

| 2022 | 7.72 | 63.07% | 43.16% |

| Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Cluster Type | It forms a fixed group with specific elderly people that has a strong group and spatial domain, and is often difficult to join. |

| Glass Group Type | Due to repeated exchanges and constant familiarity with one another, there is a tendency to form a group; however, the relationship between members remains relatively weak, yet still exhibits a strong sense of openness and inclusiveness. |

| Extensive Type | Actively interact with various elderly individuals in the venue who possess strong communication and social skills. |

| Selective Type | According to personal interests or purposes, choose the same or similar behavior of the elderly to interact, but due to the lack of continuous and stable communication, there is no trend towards the formation of groups. |

| Personal Type | There was little or no interaction with other elderly people during activities in the venue, and there was no tendency to form groups, just acting alone or watching others. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, J.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y. Research on Strategies for Creating an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment in Shanghai. Buildings 2025, 15, 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213831

Pan J, Lu X, Hu Y. Research on Strategies for Creating an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment in Shanghai. Buildings. 2025; 15(21):3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213831

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Junyu, Xinyao Lu, and Yanzhe Hu. 2025. "Research on Strategies for Creating an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment in Shanghai" Buildings 15, no. 21: 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213831

APA StylePan, J., Lu, X., & Hu, Y. (2025). Research on Strategies for Creating an Age-Friendly Community Commercial Complex Environment in Shanghai. Buildings, 15(21), 3831. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15213831