How Should Property Investors Make Decisions Amid Heightened Uncertainty: Developing an Adaptive Behavioural Model Based on Expert Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

2.2. Analysis Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Underlying Reasons Why Uncertainty Impacts Property Investment Decisions

You still get one in ten enquiries that talk about a recession coming. But be mindful, people have always said that—they always say the bubble is going to burst. (PE1)

The difference with experienced investors [is that] they know how to assess their worst-case scenario and the risk a little better than a novice. A novice [will worry about] what happens if this property goes vacant for three years, whereas an experienced one [has been] through vacancies and knows it’s usually three to six months. They (experienced investors) can put a buffer in place and keep buying. (PE1)

There are two aspects of it—optimism of picking out a bargain and [buying] at the bottom of the market. When interest rates were going up, they [would say], I’ll wait for them to come down, then I’ll jump in… [They] can have zero macro data to show [a trend] and still, human sentiment is going to change the outcome. It’s a weird human nature of trying to pick a bargain. (PE1)

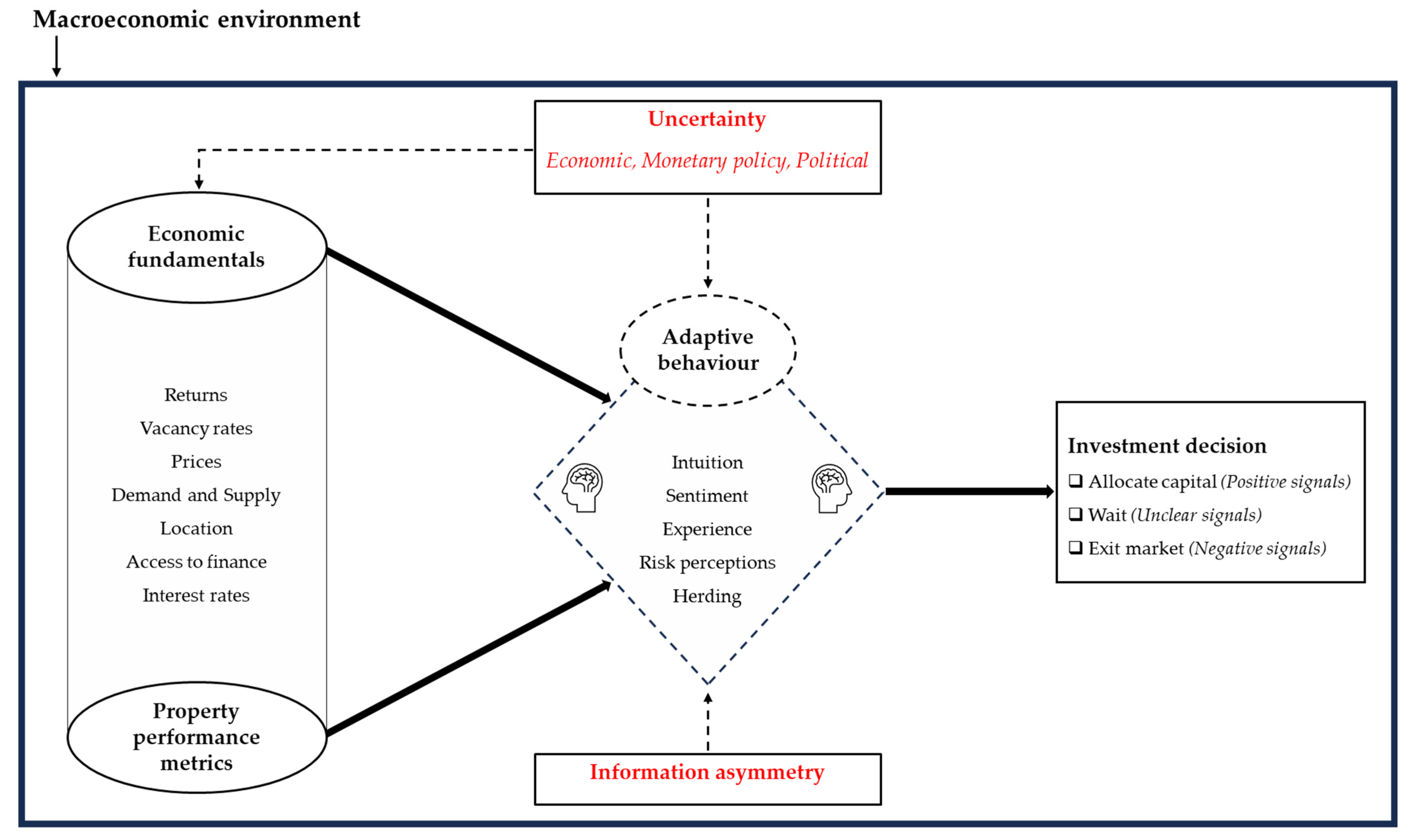

3.2. Developing an Adaptive Model for Property Investment Decision-Making Amid Heightened Economic Uncertainty

3.2.1. The Constant Drivers: Economic and Property Fundamentals

The underlying economic fundamentals are still responsible for market movements, regardless of what else is happening in the market. Cost of money definitely has an effect. Yields jumped up to allow for [higher] interest rates at the time. Instead of traditional assets which would have sold for 6% yields, they probably jumped to 7% yields to allow that wiggle room. (PE5)

3.2.2. Human Element: Investor Behaviour, Profile and Perceptions

Novice investors rarely use big data, and by that, I mean reports from Savills, CBRE, and Knight Frank, vacancy rates, and the economy. It’s always just clickbait headlines—interest rates, what inflation is doing, what unemployment is doing, what their friend told them at a barbecue and they kind of mash [all those opinions together]. [For instance], almost everyone says [they won’t invest] in office spaces because of work-from-home trends, but they have no idea what the actual vacancy rates are. (PE1)

Experienced investors perceive the market as much more profitable, whereas first-time investors perceive it as a negative and or second-guess themselves—is this a bad decision, or when is a recession going to happen? [For] someone who’s been in the market and got lots of properties, you’ve seen how much money you’ve made in the last five years, and you’re going, this is going to be OK long term, if I have that long-term approach. Novice investors have way more uncertainty in their decision-making approach. (PE1)

3.2.3. Volatile Externalities: Market Disruptions, Uncertainty, and Information Asymmetry

The awareness of growth and what a commercial property sold for is actually a bit less, so there’s more readily available information for residential. [Investors] know exactly what properties sold for. For commercial properties, you basically can’t get that information. It’s always almost blank. (PE1)

Industrial [attracted more investors] because it got so much media [coverage] about how well it was performing, especially with the really tight vacancy rates, A lot of people [who saw] it as a bit of a dirty asset at the time jumped on because everyone started talking about it, started doing a little bit more research and then realized that industrial has been around for 100 years, it’s not going anywhere, especially with e-commerce. (PE5)

A lot of people want to get in and buy, there’s a bit of fear of missing out before the rates go down… A lot of people now think it’s a good time to buy before the rates go down because if they wait until the rates go down, there will be a rush of everyone going in. (PE3)

3.3. Implementing the Model to Improve Decision-Making Amid Heightened Uncertainty

3.3.1. Expert Perspectives on Navigating Uncertainty Through Adaptive Decision-Making

[Investors] try to intuitively pick interest rates, even though none of them have an economics degree. A client will [say], we’ll probably see two or three interest rate cuts this year—and you’re like, how do you know? They’ve obviously heard it from somewhere. So, that’s a blend of investor behaviour and intuition, where they [are sure] something is going to happen without any metric or data. (PE1)

If you’re getting a lot of marketing, then you’re getting swayed by people [and] certain decisions. [Even experienced investors are susceptible] because of the herd. It’s the people that aren’t sophisticated, buying in places which changes the data metrics. And then, people who are sophisticated understand that, and then they may invest in there to take advantage of those data metrics. (PE2)

There’s way more education in the commercial space now—books in stores and four or five podcast series that didn’t exist [before]. It’s more mainstream now. Commercial wasn’t even spoken about [by private investors] five years ago. The experience and education have changed the behaviour… It removes [unfounded] fear and risks—they had no knowledge five years ago, but now they’re slightly [more] understanding… Knowledge is power. People feel more empowered with a certain amount of education… People default to negative when they don’t know something. (PE1)

Initially, it (COVID-19) started with a lot of uncertainty [and] people not knowing what would happen to the market. But as soon as the government brought in the Jobkeeper platform and a substantial amount of other stimulus to small business entities, what that did along with a substantial amount of interest rate cuts, was significantly increased liquidity in the market. With increased liquidity, meaning more cash that people had available to them together with lower interest rates, the ability to borrow money, we saw a substantial increase in property transactions. (PE2)

Regardless of what’s going on [in the economy], [successful investors] will buy in the market that they are in—if it’s on the market, they will pay market price, if it’s a cool market, they will pick up a bargain… [Those] who cross-check every number don’t end up buying lots of properties, whereas the blasé investor [usually does] better than the person who over-analysed and only bought one property… It should be a mix between adequate due diligence using the numbers and perception in the industry. (PE1)

So, the best investors that I’ve seen do very well and adapt to [uncertainty] were the ones that did capitalise on a lot of the lower socioeconomic properties that they bought and did very well. And they then moved that money into more performing long-term assets on a little bit lower leverages because they were using the profit after tax to act as a deposit of their new properties. So, the more sophisticated investors saw a good time to exit those lower, more susceptible to market movement properties. And then put that money into more longer-term [properties which are] less susceptible to market economy movements. (PE2)

3.3.2. Emerging Considerations: Sustainable Investment and Technology Integration

The conversation is coming up, but people aren’t willing to put their money where their mouth is—it still comes down to greed and numbers. You get a lot of people asking about solar panels—how do you pay for it, and what returns will it give? It’s never “I want to put solar panels to help the environment”. I’ve not once had that conversation. Every single time, [the focus] is what return on investment and government subsidies they can get. It’s never like I’m just feeling charitable, I want to help out the human race… But it is getting talked about more. I think it’s coming, but the driver is going to be legislation and incentives. (PE1)

I would say no, I can’t say I’ve ever had a client ask anything about that. I would say most [investors] are money-driven. If you presented two similar properties and one was eco-friendly and one was not, I don’t think they would [necessarily] choose the green option, definitely not something I ever get asked. (PE4)

Not in the lower-level space. I know a lot of the big players when they’re buying the big warehouse, it has to be AI-integrated. But the club sub-15 million aren’t thinking about it because the [properties] they are buying still is concrete tilt up panels on a roller door. They’re not buying anything significant enough to warrant changing their decision. [The institutional investors], they’re all looking at it knowing there’s going to be some restrictions put in by the government. (PE1)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMH | Adaptive Markets Hypothesis |

| EMH | Efficient Markets Hypothesis |

| RBA | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| PE | Property Expert |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

Appendix A. Interview Guide (Core Prompts)

Section 1: Uncertainty and Property Investment Decision-making

|

Section 2: Validating the Conceptual Model

|

References

- Ahiadu, A.A.; Abidoye, R.B.; Yiu, T.W. Commercial Property Investment in Australia: How Market Fundamentals and Investor Behaviour Shape Decisions amid Heightened Uncertainty. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2025, 43, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargitay, S.E.; Yu, S. Property Investment Decisions: A Quantitative Approach, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F. Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. J. Financ. 1970, 25, 383–417. [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore, P.; Gray, A. The Role of Investor Sentiment in Property Investment Decisions. J. Prop. Res. 2002, 19, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Orr, A. Investment Decision-Making under Economic Policy Uncertainty. J. Prop. Res. 2019, 36, 153–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruin, A.; Flint-Hartle, S. A Bounded Rationality Framework for Property Investment Behaviour. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2003, 21, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, A.S.; Berry, J.N.; Mcgreal, W.S. Investment Decision Making: A Behavioural Perspective. J. Prop. Financ. 1994, 5, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Goyal, N. Evidence on Rationality and Behavioural Biases in Investment Decision Making. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2016, 8, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Jessica, V.M. Sub-Optimal Behavioural Biases and Decision Theory in Real Estate: The Role of Investment Satisfaction and Evolutionary Psychology. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2019, 12, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A. Commercial Real Estate Investment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, V.; Gallimore, P.; Clements, J.S. Experience and Real Estate Investment Decision-Making: A Process-Tracing Investigation. J. Prop. Res. 2010, 27, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Maitland, E.; Sammartino, A. Decision Making and Uncertainty: The Role of Heuristics and Experience in Assessing a Politically Hazardous Environment. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1554–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiadu, A.A.; Abidoye, R.B. Economic Uncertainty and Direct Property Performance: A Systematic Review Using the SPAR-4-SLR Protocol. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2024, 42, 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, L.; Kunreuther, H. Organizational Decision Making Under Uncertainty Shocks; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; (No. w24924). [Google Scholar]

- Ling, D.C.; Wang, C.; Zhou, T.; Thank, W.; Archer, W.R.; Ben-Shahar, D.; Duca, J.; Eriksen, M.; Gatzlaff, D.; Ghent, A.; et al. A First Look at the Impact of COVID-19 on Commercial Real Estate Prices: Asset-Level Evidence. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 669–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.; Liusman, E.; Lu, T.; Tsang, D. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Commercial Property Rent Dynamics. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

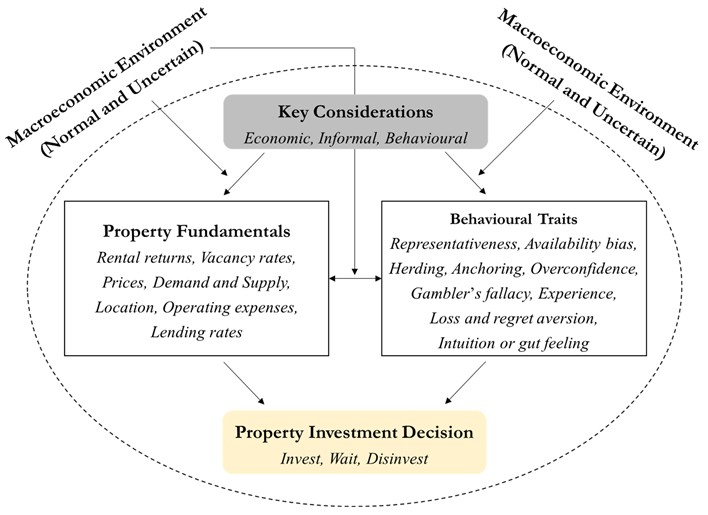

- Ahiadu, A.A.; Abidoye, R.B.; Yiu, T.W. Decision-Making Amid Economic Uncertainty: Exploring the Key Considerations of Commercial Property Investors. Buildings 2024, 14, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.; Yeung, D. How Do Investors React under Uncertainty? Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2012, 20, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. Emotion, Cognition, and Decision Making. Cogn. Emot. 2000, 14, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, D.J. Valuation Paradigm: A Rationality and (Un)Certainty Spectrum. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2017, 35, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; Ling, G.H.T.; Sipan, I.; Omar, M.; Achu, K. Effects of Behavioural Uncertainties In Property Valuation. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2020, 7, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.; Ali, H.; Jasmin, T. Valuer’s Behavioural Uncertainties in Property Valuation Decision Making. Plan. Malays. 2018, 16, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Cypher, M.; Price, S.M.; Robinson, S.; Seiler, M.J. Price Signals and Uncertainty in Commercial Real Estate Transactions. J. Real. Estate Financ. Econ. 2018, 57, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcheva, S. Volatility and the Cross-Section of Real Estate Equity Returns during COVID-19. J. Real. Estate Financ. Econ. 2022, 65, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahiadu, A.A.; Abidoye, R.B.; Yiu, T.W. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Commercial Property Performance: An In-Depth Analysis of Rents and Capital Values. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, H.F.; Tajaddini, R.; Farzanegan, M.R.; Yam, S. Responses of REITs Index and Commercial Property Prices to Economic Uncertainties: A VAR Analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 58, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausberg, C.; Krieger, P. Decision Support Systems in Real Estate: History, Types and Applications; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A. The Adaptive Markets Hypothesis. J. Portf. Manag. 2004, 30, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lee, J.M. Adaptive Market Hypothesis: Evidence from the REIT Market. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2013, 23, 1649–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Jessica, V.M. Evolution of the Housing Market under the Framework of Adaptive Market Hypothesis and Martingale Difference Hypothesis: A Case of India. Prop. Manag. 2022, 40, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmila, D.R.; Perumandla, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.S. Integrating Rational and Irrational Factors towards Explicating Investment Satisfaction and Reinvestment Intentions: A Study in the Context of Direct Residential Real Estate. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2024, 18, 938–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.R.; Silva, E.A. Mapping the Landscape of Behavioral Theories: Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.A.; Morris, Z.A.; Costello, S. The Application of Adaptive Behaviour Models: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, H.A. Rational Choice and the Structure of the Environment. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N.C. Thirty Years of Prospect Theory in Economics: A Review and Assessment. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, G.; Marengo, L.; Bassanini, A.; Valente, M. Norms as Emergent Properties of Adaptive Learning: The Case of Economic Routines. J. Evol. Econ. 1999, 9, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Pindyck, R. Investment Under Uncertainty; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kinatta, M.M.; Kaawaase, T.K.; Munene, J.C.; Nkote, I.; Nkundabanyanga, S.K. Cognitive Bias, Intuitive Attributes and Investment Decision Quality in Commercial Real Estate in Uganda. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2022, 40, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowies, G.A.; Hall, J.H.; Cloete, C.E. Anchoring and Adjustment and Herding Behaviour as Heuristic-Driven Bias in Property Investment Decision-Making in South Africa. Res. Pap. Econ. 2016, 34, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolomope, M.T. Disruption-Driven Investment Decision-Making of Listed Property Trusts in New Zealand. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Freybote, J.; Seagraves, P.A. Heterogeneous Investor Sentiment and Institutional Real Estate Investments. Real. Estate Econ. 2017, 45, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Rhee, G.; Wang, S.S. Differences in Herding: Individual vs. Institutional Investors. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2017, 45, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RBA Cash Rate Target|Reserve Bank of Australia. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/cash-rate/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ahir, H.; Bloom, N.; Furceri, D. The World Uncertainty Index. Available online: https://www.policyuncertainty.com/wui_quarterly.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kumar, R. Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners, 3rd ed.; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 0273701487. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Qualitative Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches, 4th ed.; Thousand Oaks, C., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D. REIT Property Investment Decision Making: Theory and Practice; University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.; Schuck, E. The Influence of Clients on Valuations. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 1999, 17, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, E.; Gustafsson, V. Entrepreneurs’ Decision Making under Different Levels of Uncertainty: The Role of Emotions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 568–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastamos, D.; Matysiak, G.; Stevenson, S. A Comparative Analysis of the Accuracy and Uncertainty in Real Estate and Macroeconomic Forecasts. J. Real. Estate Res. 2018, 40, 309–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Khaskheli, A.; Raza, S.A.; Shah, N. The Role of Economic Policy Uncertainty in Forecasting Housing Prices Volatility in Developed Economies: Evidence from a GARCH-MIDAS Approach. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2022, 16, 776–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, K.; Ludvigson, S.C.; Ng, S. Measuring Uncertainty. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 1177–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulan, L.; Mayer, C.; Somerville, C.T. Irreversible Investment, Real Options, and Competition: Evidence from Real Estate Development. J. Urban. Econ. 2009, 65, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfatia, H.A.; André, C.; Gupta, R. Predicting Housing Market Sentiment: The Role of Financial, Macroeconomic and Real Estate Uncertainties. J. Behav. Financ. 2022, 23, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W.; Wong, S.K. Information Asymmetry and the Rent and Vacancy Rate Dynamics in the Office Market. J. Real. Estate Financ. Econ. 2016, 53, 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.C.; Ooi, T.L.; Le, T.T. Explaining House Price Dynamics: Isolating the Role of Non-Fundamentals. J. Money Credit. Bank. 2013, 47, 87–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J. The First Decade of Behavioral Research in the Discipline of Property. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 1999, 17, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.; Ling, D.C.; Naranjo, A. Commercial Real Estate Valuation: Fundamentals versus Investor Sentiment. J. Real. Estate Financ. Econ. 2009, 38, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowies, G.A.; Hall, J.H.; Cloete, C.E. The Role of Market Fundamentals versus Market Sentiment in Property Investment Decision-Making in South Africa. J. Real. Estate Lit. 2015, 23, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Henneberry, J. Exploring Office Investment Decision-Making in Different European Contexts. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2007, 25, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaustia, M.; Perttula, M. Overconfidence and Debiasing in the Financial Industry. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2012, 4, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushinada, V.N.C. Are Individual Investors Irrational or Adaptive to Market Dynamics? J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2020, 25, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvitigala, D.; Reed, R.G. Identifying Adaptive Strategies Employed by Office Building Investors. Prop. Manag. 2015, 33, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, R.J. Irrational Exuberance; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, L.G.; Schneider, M. Ambiguity, Information Quality, and Asset Pricing. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, J.S. On the Impossibility of Rational Choice under Incomplete Information. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1996, 29, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Nazir, M.S.; Farooqi, R.; Ishfaq, M. Moderating Role of Information Asymmetry Between Cognitive Biases and Investment Decisions: A Mediating Effect of Risk Perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 828956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.C.; Naranjo, A.; Scheick, B. Investor Sentiment, Limits to Arbitrage and Private Market Returns. Real. Estate Econ. 2014, 42, 531–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funashima, Y. Media-Created Economic Uncertainty. TGU-ECON Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, C.K. Quantifying Animal Spirits: News Media and Sentiment in the Housing Market; Ross School of Business Paper. 2015, No. 1200. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2330392 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Tiwari, P. Effect of Media on the Behaviour of Investors and Stocks. Turk. Online J. Qual. Inq. 2021, 12, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, M.; Weißenberger, B.E. Information Overload Effects in Sequential Information Acquisition for Investment Decision-Making. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3722450 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bernales, A.; Valenzuela, M.; Zer, I. Effects of Information Overload on Financial Markets: How Much Is Too Much? Int. Financ. Discuss. Pap. 2023, 1372, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hansz, J.A.; Prombutr, W. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Real Estate Market: Evidence from U.S. REITs. Int. Real. Estate Rev. 2022, 25, 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, W.; Kahn, M.E. Investor Confidence as a Determinant of China’s Urban Housing Market Dynamics. Real. Estate Econ. 2016, 44, 814–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Orr, A. Changing Priorities in Investor Decision-Making: The Sustainability Agenda. In Proceedings of the European Real Estate Society Conference, Regensburg, Germany, 11 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, M.; Biel, A. Motives to Engage in Sustainable Investment: A Comparison between Institutional and Private Investors. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, F.; McAllister, P. Green Noise or Green Value? Measuring the Effects of Environmental Certification on Office Values. Real. Estate Econ. 2011, 39, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Orr, A. The Embeddedness of Sustainability in Real Estate Investment Decision-Making. J. Eur. Real. Estate Res. 2021, 14, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, G.; Reed, R.; Robinson, J. Investor Perception of the Business Case for Sustainable Office Buildings: Evidence from New Zealand. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of the Pacific Rim Real Estate Society, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23 January 2008; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, A. PropTech 2020: The Future of Real Estate. University of Oxford Research. 2020. Available online: https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-02/proptech2020.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Siniak, N.; Kauko, T.; Shavrov, S.; Marina, N. The Impact of Proptech on Real Estate Industry Growth. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 869, 062041. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/869/6/062041 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Starr, C.W.; Saginor, J.; Worzala, E. The Rise of PropTech: Emerging Industrial Technologies and Their Impact on Real Estate. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2021, 39, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Role | Experience |

|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Director (Property Investment Consultancy) | 13 years |

| PE2 | Managing Partner (Property Finance Advisory) | 18 years |

| PE3 | Director (Property Finance Brokerage) | 16 years |

| PE4 | Settlement Manager (Property Investment Consultancy) | 3 years |

| PE5 | Sales and Leasing Consultant (Property Agency and Advisory) | 20 years |

| PE6 | Director (Full-service Commercial Property Agency) | 9 years |

| PE7 | Sales and Leasing Consultant (Property Agency and Advisory) | 23 years |

| Theme | Codes (Examples) | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Economic fundamentals | Interest rates, Monetary policy | “The underlying economic fundamentals remain responsible for market movements, regardless of other market factors.” “As interest rates came down, we saw a huge [number] of people buying property.” |

| Property performance | Returns, Yields, Vacancy rates | “They can charge whatever rate they want, but an investor is buying for a return on investment.” “A lot of people were able to hold their commercial properties through the interest rate rises because they were they bought on really good yields.” |

| External market conditions | Uncertainty, Information | “A lot of people want to get in and buy; there’s a bit of fear of missing out before the rates go down.” “Initially, it (COVID-19) started with a lot of uncertainty [and] people not knowing what would happen to the market.” |

| Adaptive behaviour | Intuition, Sentiment, Experience, Herding | “The difference with experienced investors [is that] they know how to assess their worst-case scenario and the risk a little better than a novice.” “[Investors] try to intuitively pick interest rates, even though none of them have an economics degree.” |

| Investment decision | “There was definitely some sitting on hands for a time until people had an understanding as to what the future held.” “More sophisticated investors saw a good time to exit out of those lower, more susceptible to market movement properties.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahiadu, A.A.; Abidoye, R.B.; Yiu, T.W. How Should Property Investors Make Decisions Amid Heightened Uncertainty: Developing an Adaptive Behavioural Model Based on Expert Perspectives. Buildings 2025, 15, 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203648

Ahiadu AA, Abidoye RB, Yiu TW. How Should Property Investors Make Decisions Amid Heightened Uncertainty: Developing an Adaptive Behavioural Model Based on Expert Perspectives. Buildings. 2025; 15(20):3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203648

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhiadu, Albert Agbeko, Rotimi Boluwatife Abidoye, and Tak Wing Yiu. 2025. "How Should Property Investors Make Decisions Amid Heightened Uncertainty: Developing an Adaptive Behavioural Model Based on Expert Perspectives" Buildings 15, no. 20: 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203648

APA StyleAhiadu, A. A., Abidoye, R. B., & Yiu, T. W. (2025). How Should Property Investors Make Decisions Amid Heightened Uncertainty: Developing an Adaptive Behavioural Model Based on Expert Perspectives. Buildings, 15(20), 3648. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15203648