Abstract

With the rapid development of urbanization and tourism in China, increasing attention has been paid to the protection and utilization of historical and cultural heritage, while tourists’ demands for travel experiences have gradually shifted towards in-depth cultural perception. This paper selects Beijing Fayuan Temple Historic and Cultural District as the research case, and adopts methods such as the LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) topic model, collection and analysis of online text data, and field research to explore the current situation of pedestrian space in Fayuan Temple District and its optimization strategies from the perspective of tourists’ perception. The study found that the dimensions of tourists’ perception of the pedestrian space in Fayuan Temple District mainly include six aspects: historical buildings and relics, tour modes and transportation, natural landscapes and environment, historical figures and culture, residents’ life and activities, and tourists’ experiences and visits. By integrating online text data, questionnaire surveys, and on-site behavioral observations, the study constructed a “physical environment-cultural experience-behavioral network” three-dimensional IPA (Importance–Possession Analysis) evaluation model, and analyzed and evaluated the high-frequency perception elements in tourists’ spontaneous evaluations. Based on the current situation evaluation of the pedestrian space in Fayuan Temple District, this paper puts forward optimization strategies for the perception of pedestrian space from the aspects of block space, transportation usage, landscape ecology, digital technology, and cultural symbol translation. It aims to promote the high-quality development of historical blocks by improving and optimizing the pedestrian space, and achieve the dual goals of cultural inheritance and utilization of tourism resources.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Against the backdrop of global cultural dialogue and China’s cultural rejuvenation, the protection of historical and cultural blocks has become a national cultural strategy. The 14th Five-Year Plan for Cultural Development [1] puts forward requirements for systematic protection and utilization, while the construction of the Grand Canal/Great Wall National Cultural Parks has explored paths for functional activation.

Beijing has transformed historical blocks into perceptible symbols of civilization through projects such as the application for World Heritage status of its central axis. Pedestrian traffic plays a crucial role in protecting the texture of streets and lanes. Cases such as Qinghefang in Hangzhou and Jingshan District in Beijing have verified the effectiveness of pedestrian spaces in maintaining the integrity of historical structures. The Guidelines for the Protection and Renewal of Historical and Cultural Blocks in Beijing [2] clearly stipulates the establishment of a slow traffic system. Cases such as Qinghefang in Hangzhou and Jingshan District in Beijing have verified the effectiveness of pedestrian spaces in maintaining the integrity of historical structures.

As China’s urbanization rate exceeds 65% [3] and the scale of the culture and tourism industry reaches 6.5 trillion yuan [4], the protection and utilization of historical and cultural heritage has entered a new phase. As carriers of “living heritage”, historical and cultural blocks hold dual values in sustaining urban cultural context [5] and promoting the integration of culture and tourism [6]. As a spatial carrier of Xuannan culture, Beijing’s Fayuan Temple Block preserves 52 cultural relics protection units including the Tang-dynasty Fayuan Temple and the clusters of guildhalls from the Ming and Qing dynasties [7], and boasts favorable advantages in pedestrian space. The pedestrian space system in the historical block of Fayuan Temple serves as a composite site for displaying cultural symbols. It activates the spatial significance through visitors’ physical practices, thereby achieving the integration of perceptions of material and non-material elements.

1.2. Research Significance and Problems

Historical pedestrian streets suffer from excessive commercialization that erodes their cultural essence. For example, the organic renewal of Ju’er Hutong (Figure 1c) stands in contrast to the “fake antique” phenomenon in some other blocks. In the context of the protection and renewal of historical blocks, the “fake antique” phenomenon specifically refers to a short-sighted practice that disregards historical authenticity and cultural continuity. It focuses on pursuing short-term commercial interests or superficial visual effects, while blindly constructing imitation ancient buildings or man-made historical landscapes.

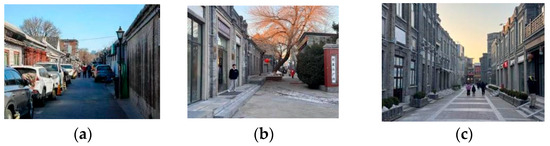

Figure 1.

Case Studies of Historic District Renewal. Figure Source: Taken by the author. (a) Current Status of Ju’er Hutong. (b) RenovationAuxiliary Street of Qianmen Street. (c) Qianmen Street Main Street.

There is a shift from sightseeing to deep immersion; however, issues such as insufficient digital facilities and imbalanced vitality between main and auxiliary streets persist (exemplified by Qianmen Street, Figure 1a,b). A review of relevant previous studies indicates that enhancing the vitality of historical blocks is crucial to the protection of old urban areas. This study thus focuses on optimizing pedestrian spaces for visitors within historical blocks [8].

Preliminary surveys show that 78% of respondents expect to have in-depth cultural experiences in historical blocks. However, the Fayuan Temple Block faces three major contradictions: (1) Insufficient accessibility of historical buildings (only 37% of cultural relic protection units are open to the public); (2) Monotonous cultural display methods (86% are static exhibition boards); (3) Lack of authentic living scenes (the resident replacement rate has reached 42% in the past decade).

This study employs online data text analysis and semantic network analysis to examine the public’s perceptions when in the historical and cultural space of Fayuan Temple. Using an IPA (Importance–Performance Analysis) quadrant chart, this study establishes connections between cognitive and emotional images, reveals the actual manifestations of visitors’ perceptions of pedestrian spaces in the block, and identifies the priority factors for improving visitors’ perceptions in Beijing’s historical and cultural blocks. Based on this, optimization strategies for pedestrian space perception are proposed to respond to the public’s perceptual demands regarding pedestrian spaces in historical blocks.

Through the analysis of pedestrian spaces in historical blocks, this study aims to provide way finding guidance, optimize tourist routes, offer comfortable environments, and create cultural atmospheres. This can thus provide methodological support for the reshaping of place spirit and the optimization of pedestrian spaces in the renewal of similar historical blocks. By decoding urban memories and designing paths for contextual perception experiences, the public can achieve the transmission of heritage value cognition during spatial wandering, fostering place attachment.

1.3. Literature Review

In China, research in recent years has focused on technological innovation and collaboration among multiple stakeholders, covering the renewal of protection concepts, the integration of technical methods, innovation in governance models, among other aspects.

In terms of the innovation of protection concepts and methods, relevant scholars focus on the collaborative protection of culture and the small-scale renovation of blocks, among other aspects. Li Rui et al. introduced UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) and proposed the methods of “dynamic layering” and “holistic connection” in the planning of Fengyuan Street-Liwan Lake Block in Guangzhou, emphasizing the continuity of historical layers and the coordinated protection of natural environments, built environments, and intangible culture [9]. The following year, Wang Jianguo proposed a path of “adaptive protection” for the ancient South Street in Dingshu, Yixing. He advocated small-scale and incremental renewal, stimulating the independent vitality of the community through acupuncture-like renovations, balancing heritage preservation with people’s livelihood needs, and forming a model of “living regeneration” [10].

In terms of the application of analytical technologies and tools, scholars focus on the innovative application of analytical methods. Jiang Xin et al. conducted a perception evaluation of “authenticity” for historical blocks along the Grand Canal using multi-source data (POI, images, online reviews). They distinguished four models: “authentic preservation”, “reconstruction and transformation”, “functional replacement”, and “intervention and renewal”, emphasizing that authenticity should balance the truthfulness of material remains and the continuity of cultural experience [11]. Song Zhehao conducted a morphological typological analysis of Nanjing’s Hehuatang Historical Block using a multi-scale hierarchical analysis model and digital tools (such as GIS and Grasshopper). Through data-driven analysis of the demands of multiple stakeholders, he optimized the efficiency of spatial decision-making [12], thereby achieving intelligent reconstruction of the street texture and courtyard relationships.

In terms of comprehensive governance and public participation, scholars emphasize the collective participatory protection of historical and cultural blocks. Wu Yun summarized the practical experience of Huzhou and proposed a trinity theory of “cultural identity, heritage protection, and urban renewal”, emphasizing the key role of public participation and institutional guarantees in sustainable protection [13].

In terms of analytical methods, tools such as IPA (Importance–Performance Analysis), GIS spatial analysis, and structural equation models have also been widely applied to visitor perception evaluation and spatial quality optimization [14,15]. For instance, Nanjing’s Yihe Road Block identified shortcomings in the pedestrian environment through IPA analysis and proposed optimization paths for landscape nodes and traffic organization [16]. In addition, emerging technologies such as fire risk assessment, soundscape perception, and online review text analysis are gradually being integrated into the dynamic monitoring system of historical blocks [17].

Globally, scholars began researching the protection and renewal of historical blocks relatively early, forming a diverse theoretical system centered on the protection of cultural values while considering social functions and spatial activation (Table 1). Since the 1960s, European countries have taken the lead in incorporating the concept of “integral protection” into urban renewal frameworks, emphasizing the coordinated preservation of the physical space and intangible culture of historical blocks. For example, Italy’s Venice Charter put forward the “principle of minimal intervention”, advocating the continuation of block texture through micro-renewal measures. This idea has influenced small-scale incremental renovation practices in many Asian countries [18].

Table 1.

International Dimensions of Historic District Conservation.

Since the 21st century, Western scholars have further focused on the social dimension of block renewal. For instance, British scholar Carmona proposed a “public space quality assessment model”, incorporating indicators such as pedestrian accessibility and visual continuity into the vitality evaluation system of historical blocks, which provides a methodological basis for research on visitor perception [19].

Western scholars generally emphasize the symbiotic relationship between “walk ability” [20] and historical blocks in urban space. For example, historic urban areas in Europe have built continuous and comfortable pedestrian networks by optimizing sidewalk dimensions, adding recreational facilities, and creating landscape nodes. In the renovation of shopping streets, Japan focuses on the organic integration of traditional businesses and modern commerce. Through regulating the density of business types and innovating operational strategies, it not only maintains the lively atmosphere of the blocks but also enhances their cultural and tourism appeal. Its experience provides important insights for the renovation of arcade blocks in China.

Experience from the development of block systems in Western countries shows that public participation can effectively enhance the sustainability of renewal projects. For instance, the UK has adopted a “community planning permission” system, incorporating residents’ demands into the decision-making process of urban renewal. Foreign scholars attach great importance to pedestrian crossing safety. The Carlos team [21] developed a pedestrian-participatory design model and created the Safe Walking system, which is based on visual recognition technology for mobile devices. This system enables a danger prediction mechanism by monitoring pedestrians’ gait characteristics.

In the dimension of minor safety, Mahboobeh [22] and Ferenchak [23] used behavioral geography methods to analyze children’s travel patterns, accurately identified the restrictive mechanisms of street space forms and built environment elements on pedestrian safety, and ultimately developed a people-oriented spatial intervention paradigm. The study also pointed out that excessive commercialization may weaken the authenticity of local culture; therefore, it is necessary to establish a business type access mechanism to balance the protection of cultural heritage and the intensity of commercial development.

A review of the literature reveals that existing studies have the following limitations: most current research focuses on business regulation, with insufficient attention to the positioning of pedestrian spaces as carriers of cultural exhibitions; the perceptual dimension is singular, and no emotional experience evaluation system has been established; conservation and renewal efforts mostly focus on the transformation of physical spaces, with inadequate exploration of the synergistic mechanisms of non-physical elements such as behavioral interactions and cultural perceptions between tourists and residents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Objects

This study takes the pedestrian spaces in Beijing Fayuan Temple Historic and Cultural District as the core research object, focusing on the interaction between material and non-material elements, and explores their composite value in the inheritance of urban context and the improvement of spatial quality. The Fayuan Temple Historic and Cultural District is located in the southwest of Beijing’s old city, covering an area of approximately 32 hectares. This area completely preserves the street texture of the Liao Dynasty (Figure 2), with existing historical buildings accounting for 41%, among which 12 are national-level cultural relics protection units. According to the “Regulatory Detailed Plan for the Core Area of the Capital’s Functions” (2018) [7], its functional positioning is “a core node of cultural exploration routes”.

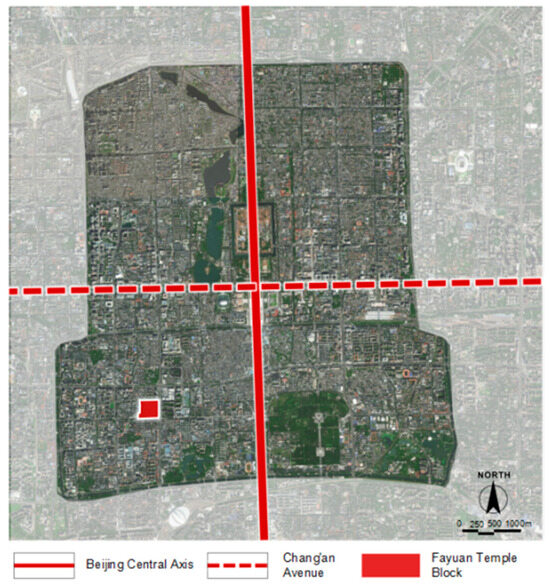

Figure 2.

Fayuan Temple District Location. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

The Fayuan Temple Historical and Cultural Block is located in Beijing, specifically bounded on the north by Fayuan Temple Back Street, on the east by Caishikou Street, on the south by Nanheng West Street, and on the west by Jiaozi Hutong and the Islamic Seminary. It covers a total area of approximately 16 to 21 hectares.

With a long history, the block is an important witness to Yuzhou City of the Tang Dynasty and Nanjing City of the Liao Dynasty, and has preserved the “Shu Hutong” (vertical hutong) street texture formed during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Currently, there are 191 courtyards in the block, including 41 protected courtyards and 5 cultural heritage sites at or above the district level (such as Fayuan Temple, Hunan Guild Hall, and Liuyang Guild Hall), along with 10 ancient and famous trees, boasting rich cultural resources. According to the 2010 national census, the block has a registered population of approximately 8664 people and a permanent floating population of around 1500 people.

Currently, the block is still dominated by residential functions and retains a strong sense of daily life, but it also faces typical issues such as aging infrastructure, some courtyards having turned into mixed-occupation yards, and a living environment in need of improvement.

The research objects of this paper include the public pedestrian network centered on hutongs, lanes and squares in the Fayuan Temple District, as well as related material elements such as landscape corridors, building interfaces and street facilities. It also includes non-material cultural forms such as folk activities, commercial formats and community interactions. The material and non-material elements of the district together form a three-dimensional dimension of tourists’ perception.

2.2. Data Collection

The online text analysis paradigm and collects online review data based on the evaluation index system for tourists’ perceptual assessment of the district. It then uses social semantic network analysis to reveal the relational structure of elements, and through statistics on the frequency of high-frequency words and measurement of attention levels, deconstructs the attention dimensions and cognitive characteristics of tourists regarding the image elements of Fayuan Temple District. Finally, based on field survey data, the IPA (Importance–Performance Analysis) method is used to determine tourists’ satisfaction with each attention factor, and the importance of each element and the causes of satisfaction are analyzed according to the results.

2.2.1. Collection of Online Text Data

Against the backdrop of digital technology empowerment, tourism UGC (User-Generated Content) platforms have established a new mechanism for recording tourist behaviors. Based on the theoretical framework of tourists’ spatio-temporal behavior [24], this study systematically collected multi-source heterogeneous data from mainstream tourism platforms and social media platforms for the case of Fayuan Temple District. Since the data integrates both objective behavior records and subjective perception expressions in terms of content, it has high ecological validity. In terms of technical implementation paths, this study adopts a hybrid collection strategy to ensure the completeness and timeliness of data acquisition. During the research process, the ROST CM6.0 social computing analysis platform was used for text cleaning, semantic network construction, and feature word extraction. A technical closed-loop of “data collection—corpus cleaning—feature extraction” was established to deconstruct the explicit representations and implicit characteristics of tourists’ perceptions.

2.2.2. Data Collection from Field Research

Based on case studies and multi-dimensional field observations of historical and cultural districts such as Qianmen Street, Ju’er Hutong, and Zhongshan Road, the authors conducted a preliminary investigation into the tourist perception factors of the pedestrian space within the Fayuan Temple historic area (Figure 3). The aim was to filter perception-related factors collected from UGC data and identify key perceptual elements of the pedestrian space. Through extensive data collection, case studies, and investigations spanning time and space, this research lays the foundation for interpreting the distribution of factors influencing tourists’ perceptions of pedestrian spaces in Fayuan Temple District.

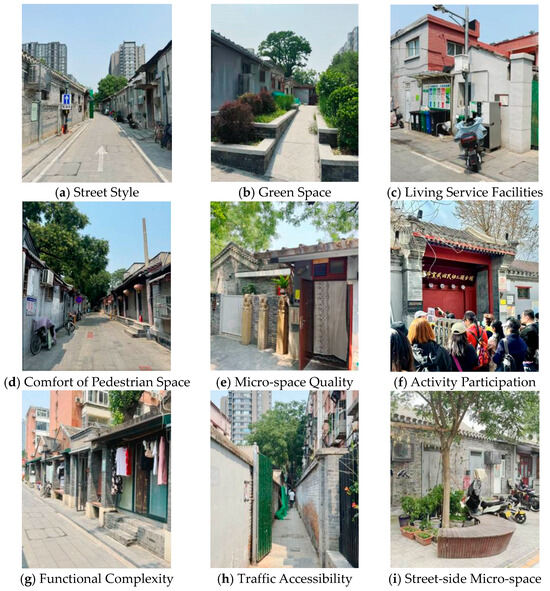

Figure 3.

Preliminary Study of Pedestrian Space Components. Figure Source: Taken by the author.

Based on preliminary research and investigations of historical and cultural districts, courtyard dwellings (siheyuan), and hutong alleys, this study has refined a list of perceptual factors for pedestrian spaces (Table 2). Among these, physical elements refer to the objectively existing, directly perceivable tangible entities within the pedestrian environment, which serve as the physical carriers of the walking experience; non-physical elements, although not existing in tangible form, profoundly influence people’s perception, utilization, and emotional connection to the space.

Table 2.

Table Strategy Categorization from Studies.

Among the perceptual factors of physical elements, spatial form and layout constitute the macro-level structure and framework of pedestrian spaces; environmental landscape and greening influence the comfort, ecological value, and aesthetic quality of the environment; mixed functions and usage refer to the diversity of activities at ground-floor buildings and public spaces along the street, attracting people to walk and linger; creative design and optimization represent a “quality enhancement and functional upgrade” beyond basic utility, addressing specific issues and improving spatial quality through innovative design.

Among the perceptual factors of non-physical elements, cultural heritage and cultivation represent the “historical memory” and “unique identity” of a space; spatial quality and experience refer to the comprehensive subjective perception people gain within the space; functional support and services encompass the soft support and management safeguards provided to users; “transport accessibility and connectivity” is defined by the ease of seamless integration and convenient transfer between the pedestrian space and various transportation modes—particularly green mobility—as well as the locational advantage of the block within the broader urban transport network. It addresses the fundamental issue of whether people can easily access the pedestrian space and how this space connects to the broader urban network.

Through field pre-investigation and expert interviews, the questionnaire content was determined, and tourist satisfaction levels regarding various factors of interest were collected via the survey (Figure 4).

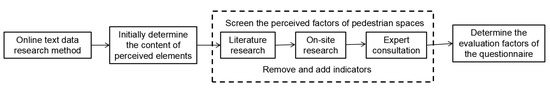

Figure 4.

Questionnaire Development Process. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

The questionnaire in this study combines unstructured questions and structured scales, and is divided into two main parts (Table 3). Relevant surveys show that the satisfaction evaluation of respondents is restricted by multiple factors. Therefore, during the survey, it is necessary to clarify the social characteristics of the respondents and explore related influencing factors, and conduct a multi-dimensional evaluation by integrating the identifiability, perception intensity and satisfaction of the perception factors of the district’s pedestrian spaces.

Table 3.

Questionnaire Design Rationale.

For the classification of respondents’ demographic information, respondents were not only classified by their traditional occupational categories, but also their origin in the Fayuan Temple Block was divided into two major categories: local residents and tourists. Meanwhile, information on respondents’ purposes and frequency of visiting the Fayuan Temple Block was collected to assess their preference for the block. The age groups of the survey subjects were divided into the following categories: under 18, 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, and 56 and above.

During the field research, questionnaires were randomly distributed to tourists visiting the block. Efforts were made to adjust the composition of respondents to ensure they represented complete demographic characteristics. Questionnaires were distributed and collected on-site: a total of 258 questionnaires were distributed, among which 240 were valid, resulting in a valid response rate of 93%. After the questionnaires were completed, on–site interviews were conducted in conjunction to enhance the authenticity and validity of the questionnaires.

Among these, the meaning of perceptual factors of pedestrian spaces refers to the internal influencing factors that form a comprehensive subjective evaluation of a space’s safety, comfort, pleasure, and attractiveness—factors derived when pedestrians receive and process environmental information through channels such as visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, and social perception in a walking environment. This part involves rating the 30 perception elements (extracted from the two dimensions of the walking space perception element composition summarized above, namely material elements and intangible elements) on a Likert scale. Tourist satisfaction for each dimension is obtained from these ratings.

2.3. Analysis Method

2.3.1. LDA Topic Modeling

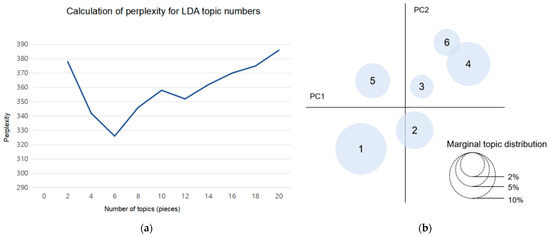

Machine learning has significant advantages in topic recognition and semantic mining, and can handle large amounts of data. Therefore, the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model [25] is introduced. LDA is an unsupervised generative statistical model used to discover latent topics in a corpus. Each document is represented as a mixture of multiple topics, with each topic being a probability distribution over words. This method can be applied to classify themes in tourist reviews in the internet-dominated era, thereby capturing the predominant sentiments among visitors. The figures show that when the number of topics is 6, the perplexity is the smallest, and this classification has the strongest generality. The distribution of each dimension in the topic distance map is relatively scattered, and the semantics of keywords are relatively consistent, which can clearly reflect the characteristics of various topics (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Perplexity Distribution Across Themes. Figure Source: Drawn by the author. (a) Line Chart of Perplexity under Different Numbers of Topics. (b) Output Diagram of Topic Model Results.

2.3.2. Social Network Semantic Analysis

Social semantic network generation tools [26] can extract core high-frequency words closely related to Fayuan Temple District from tourists’ reviews, generate visual graphs based on online texts, and then be used to study the relationships between tourists’ high-frequency words and the connections among various types of words. The results of social semantic network analysis show that the core words of Fayuan Temple District center on tourist destination information such as “Beijing”, “Fayuan Temple”, “Hutong” and “Huiguan (Guild Hall)”, as well as cultural elements such as “lilac”, “Lu Xun” and “culture”. These words express the deepest-level impressions of tourists on Fayuan Temple District, which are consistent with the theme of Fayuan Temple District, so the research on text data is of value.

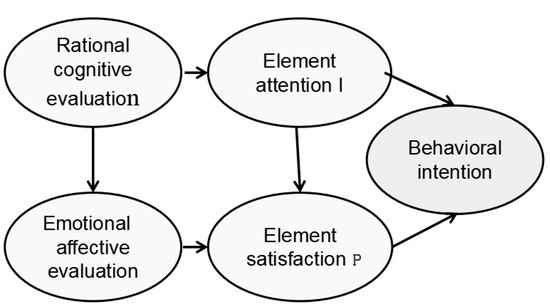

2.3.3. Importance–Satisfaction (IPA) Analysis Method

The IPA (Importance–Performance Analysis) two-dimensional evaluation model [27], a classic tool in tourism geography research, has a technical core focused on deconstructing the cognitive mechanisms of tourist destinations. Drawing on the tourists’ “cognition-emotion-intention” psychological model (Figure 6). The direction of arrows in the diagram typically represents the paths of influence within the model. An arrow pointing from “Rational Cognitive Evaluation” to “Emotional Affective Evaluation” indicates that rational, logical analysis directly influences and shapes emotional responses. An arrow from “Rational Cognitive Evaluation” to “Element Attention I” signifies that during decision-making, rational cognition acts as a filter, evaluating the value of various attributes and thereby determining which aspects individuals should prioritize. An arrow from “Emotional Affective Evaluation” to “Element Satisfaction P” denotes that an individual’s emotional state influences their satisfaction judgment regarding the performance of specific elements. Finally, arrows from both “Element Attention I” and “Element Satisfaction P” pointing to “Behavioral Intention” demonstrate that behavioral intention is jointly determined by “what individuals consider important” and “their satisfaction with the performance of these important aspects”. The study uses the frequency of elements in review data as tourists’ attention and the element satisfaction derived from Likert scale scoring as tourists’ satisfaction. To further explore suggestions for optimizing the perceived elements of pedestrian spaces in the district, IPA (Importance–Performance Analysis) is introduced to evaluate and prioritize elements in the renovation of historic districts.

Figure 6.

Psychological Model of Cognition–Affect–Intention. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

In the IPA matrix, the horizontal axis represents “performance” scores and the vertical axis represents “importance” scores. This study constructs a coordinate matrix with attention as the horizontal axis and satisfaction as the vertical axis, and derives the current status of tourists’ perceptions of various elements in the pedestrian spaces of historic districts based on the distribution of these elements [28].

3. Results

3.1. Screening of Perceptual Elements

In this study, a “pedestrian space element database” is first constructed. Specifically, based on field observations and interviews, the perceived elements of pedestrian space are obtained by drawing on academic resources, and these perceived elements need to undergo parsing across temporal and spatial dimensions. Through the network text data analysis method, in-depth mining and analysis are conducted on a large amount of user-generated content (UGC) data related to blocks to identify tourists’ feelings and experiences, which are spontaneously expressed by tourists in the process of interaction.

Furthermore, the “block perception factors” are extracted, and the “pedestrian space element database” is combined with the “block perception factors” to find their intersection. Through the interaction of multiple methods and a multi-stage verification process, a relatively comprehensive and practically significant list of tourists’ perception factors regarding the pedestrian space in Fayuan Temple Block has been constructed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of Perceptual Factors in Pedestrian Spaces.

3.2. Construction of the Perception Dimension System

3.2.1. Analysis of Perception on Material Elements

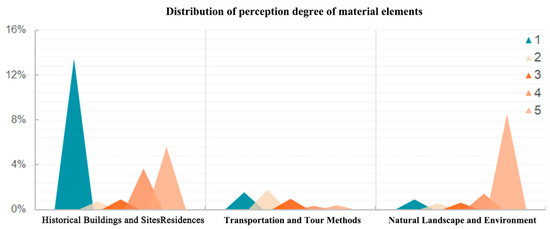

This study extracts and analyzes the practically significant tourists’ perception factors regarding the pedestrian space in Fayuan Temple Block through the interaction of multiple methods and a multi-stage verification process. Among them, in the overall perception dimension of material elements, the material elements of the pedestrian space in the block mainly include three major aspects: historical buildings and sites, transportation and tourist modes, and natural landscape and environment (Figure 7 and Table 4).

Figure 7.

Perceptual Intensity of Material Elements. Source of the chart: drawn by the author.

The attention degree of historical buildings and sites reaches 24.32%, making it the most concerned part among material elements. Tourists show significant attention to elements such as hutongs, history, former residences, and ancient buildings in the Fayuan Temple Block, which is specifically reflected in terms like “hutong”, “former residence”, “ancient temple”, and “yard”. This indicates that tourists attach relatively high importance to the traditional buildings in the block and their historical backgrounds, and can form a strong perception and cognition of such elements.

In terms of transportation and visiting methods, the degree of attention stands at 5.00%. Among these, the main concerns of tourists include “routes”, “cycling”, “subway stations” and so on, which reflects their attention to the transportation convenience of the block. In terms of natural landscapes and environment, the degree of attention reaches 11.99%.

Tourists’ attention to the environment is reflected not only in the selection of plant landscapes, such as “lilac” and “crabapple”, but also in the details of environmental creation, such as “tranquility” and “fragrance of flowers”. This indicates that the greening and landscape design of the block play an important role in enhancing tourists’ overall experience, reflects tourists’ preference for floral landscapes and natural atmosphere, and underscores the important position of the block’s environmental landscape among material elements.

In summary, among the material elements of the pedestrian spaces in Fayuan Temple Block, historical buildings and sites, transportation facilities, and environmental greening are all important factors affecting tourists’ perception. They, respectively, influence tourists’ overall experience in terms of historical and cultural perception, convenience, and environmental atmosphere.

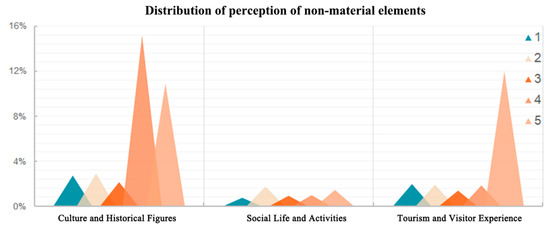

3.2.2. Analysis of Perception of Intangible Elements

In the dimension of intangible element perception, it includes the content of concern and degree of attention in three aspects: culture and historical figures, social life and activities, as well as tourism and tourist experience (Figure 8 and Table 4).

Figure 8.

Perceptual Intensity of Intangible Elements. Source of the chart: drawn by the author.

The theme of culture and historical figures, with an absolute advantage of 33.79%, dominates the perception of intangible elements, revealing the core value of historical and cultural resources. The theme of social life and activities, with an overall perception degree of 5.78%, highlights the fundamental role of public life. Terms such as recreational facilities and quality of living environment focus on the appeal for functional optimization, feeding back into the demand for spatial livability. Community activities and the vibe of old urban life maintain the spirit of place through marketplace scenes, confirming the cohesive value of social interaction in cultural continuity [29].

A perception degree of 19.12% regarding tourism and tourist experience confirms the strategic position of tourism experience. “In-depth experience of old Beijing culture” has become the core appeal, reflecting tourists’ yearning for cultural identity. Sensory experience and psychological experience reveal the influence threshold of scene details on emotional reach; it is necessary to optimize the design of soundscapes, catalysts, etc., to enhance the sense of immersion [30]. The sense of gain from historical culture and the experience of cultural atmosphere highlight the effectiveness of scene narration in value transmission.

In summary, intangible elements exhibit a hierarchical structure of “cultural anchoring-life weaving-experience deepening”, that is, historical narratives construct the cognitive foundation [31], public activities maintain social networks [32], and tourist experiences catalyze value spillover [33].

3.3. Results of IPA Analysis

Based on the results of on-site surveys, this study deduces tourists’ cognitive and emotional characteristics of Fayuan Temple Block through analyzing the degree of attention to and satisfaction with the block’s perceptual elements, and further identifies issues related to tourists’ perception of the block’s pedestrian spaces. The study establishes an IPA model based on the degree of attention and satisfaction to conduct discussions, thereby exploring the existing issues concerning tourists’ perception of the block [34].

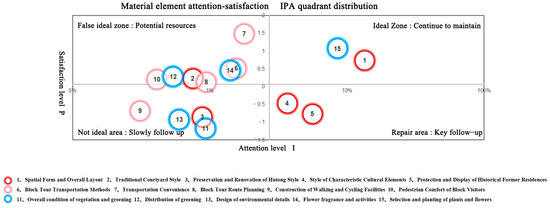

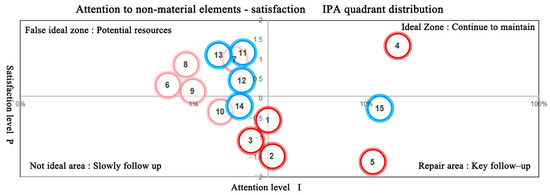

3.3.1. Distribution Characteristics and Analysis of Perceptual Elements

Using the Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) framework, an IPA model was constructed with the Importance (I) values of each indicator plotted along the horizontal axis and the Performance (P) values (Satisfaction) plotted along the vertical axis. The truncated mean values for Importance (2.72%) and Satisfaction (P) (0.0615) served as the reference points for the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively. The distribution of perceived elements across the resulting quadrants is detailed in Table 5 and Table 6. Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the IPA quadrant distributions depicting the Importance–Satisfaction relationship for non-material elements and material elements, respectively.

Table 5.

Perception Patterns of Material Elements.

Table 6.

Perception Patterns of Intangible Elements.

Figure 9.

IPA Quadrant Analysis: Material Elements. Source of the chart: drawn by the author.

Figure 10.

IPA Quadrant Analysis: Intangible Elements. Source of the chart: drawn by the author.

This translation maintains the technical precision of the original description regarding the IPA analysis results, uses standard academic terminology for IPA and the specific elements, and presents the data clearly. The focus is on accurately conveying the performance of elements within the designated IPA quadrant. This reflects the excellent performance in the integration of historical buildings and natural landscapes, and tourists’ positive feedback confirms that such elements play an important role in enhancing the tourist experience and its quality. At the intangible level, “the display of Fayuan Temple’s historical background and cultural atmosphere”—with a satisfaction degree of 1.36 and a perception degree of 15.17%—demonstrates the profound influence of historical and cultural factors on tourists.

Elements in the “False Ideal Zone”, though failing to fully arouse tourists’ attention, have their satisfaction reaching or approaching the overall average level, indicating that the resources in this zone have not been fully tapped. For example, in terms of material elements, although “style and features of characteristic cultural elements” (−0.47) and “protection and display of historical former residence buildings” (−0.76) have relatively low satisfaction degrees, their cultural value is still partially recognized as evidenced by a satisfaction degree of 3.66% and a perception degree of 5.58%. In the intangible domain, the satisfaction degrees of elements related to “protection of cultural heritage” (−0.54) and “display and inheritance” (−1.46) reflect the profound significance of cultural protection and display.

In the “Unfavorable Zone”, both material and intangible perceptual elements are characterized by low levels of satisfaction and attention, thus facing significant pressure for improvement. For material elements, such as “preservation and renovation of hutong styles” and “construction of walking and cycling facilities”, their satisfaction degrees stand at −0.85 and −0.68, respectively, reflecting the inadequacy in the promotion and maintenance of public facilities and infrastructure. Additionally, for intangible elements like “cultural immersive experience activities”, with a satisfaction degree of −1.07, it reveals the lack of innovation in existing cultural experience activities.

The Remedial Zone focuses on perceptual elements with high attention but low satisfaction. Although the elements within this quadrant receive high attention, their actual performance is unsatisfactory. For instance, among material elements, the satisfaction degrees of “transportation modes for block tours” and “styles of traditional courtyards” are 0.52 and 0.23, respectively, indicating that these elements fail to achieve the expected value. Additionally, for some intangible elements, such as “distribution and experience of recreational facilities” and “experience of community activities”, their satisfaction degrees are 0.35 and 0.19, which reveals great potential for improvement.

3.3.2. Existing Core Issues of Elements

Based on IPA quadrant analysis and multi-channel surveys, it is concluded that the material elements of the current pedestrian spaces still have contradictions in three aspects, which are concentratedly reflected in the three dimensions of the integrity of the block texture, the adaptability of the transportation system, and the narrativity of the landscape environment (Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of Key Issues.

The specific analysis of the existing problem dimensions of various material elements is as follows:

- (1)

- Temporal–Spatial Mismatch between Block Texture Protection and Functional Activation

There are more than 20 remaining guildhall relics in the block, which confirm the characteristics of cultural aggregation of the historical “Southern City Scholar Town”. However, data show that the satisfaction degree for “protection and display of historical former residence buildings” is only −0.76, and the deep-seated contradiction lies in the disconnection between the protection mode and the activation mechanism. On one hand, nearly half of the one-story courtyard houses in the core area have illegal constructions and extensions, and the layout of traditional quadrangle courtyards has been fragmented and damaged. On the other hand, most guildhall buildings remain in the stage of listed protection. For example, the former residence of Tan Sitong in Liuyang Guildhall has only undergone structural reinforcement, lacking scene-based exhibition design. Such “frozen protection” [35] results in tourists’ perception degree of “style and features of characteristic cultural elements” being only 3.66%, and the cultural readability of historical spaces is seriously weakened.

- (2)

- Dynamic Imbalance between Transportation System Transformation and Tourist Demand

Most hutongs are less than 5 m in width, yet the rate of motor vehicles occupying road space remains high, leading to a persistent decline in satisfaction with “the construction of walking and cycling facilities” (−0.68). Launched projects such as symbiotic courtyard renovations have added pocket parks; however, there is a stark mismatch between the quantity of recreational facilities and tourist density, and outdoor resting spaces in major streets and alleys still need to be increased.

- (3)

- Insufficient Narration in Landscape Environment Creation and Historical Context

Although the block retains a complete lilac community (satisfaction with “plants and flowers” stands at 1.07), the overall landscape system exhibits fragmented characteristics [36]: the satisfaction with “greening distribution” around historical buildings is only 0.28, revealing the problem of disconnection between plant configuration and spatial narration.

As the core carrier of Xuannan Culture, the Fayuan Temple Historical and Cultural Block boasts an intangible heritage system encompassing multiple cultural layers such as Buddhist propagation, scholarly exchanges, and urban folk life [37]. However, based on IPA quadrant analysis and field research, the intangible elements in current pedestrian spaces are confronted with systematic challenges including the deconstruction of cultural memory, the alienation of community ecology, and the suspension of emotional identity (Table 8), which are undermining the living inheritance of the block’s cultural genes.

Table 8.

Core Challenges Identified.

The specific analysis of the dimensions of existing problems concerning each non-material element is as follows:

- (1)

- The plight of superficialization in the transmission of cultural memory

The existing guild hall ruins in the neighborhood carry the collective memory of scholars in the Ming and Qing dynasties gathering through literary exchanges to make friends. However, IPA data shows that the satisfaction degree with “the display and inheritance of cultural heritage” is as low as −1.46, revealing flaws in the cultural interpretation system. Surveys indicate that tourists stay at the guild hall for a relatively short time, which suggests that the spirit of the scholars has not been effectively transformed into experiential cultural capital. In the dimension of cultural experience, Fayuan Temple, as the location of the China Buddhist Academy, continues the traditional scripture-chanting mode in its “Lilac Poetry Gathering” activities. However, it has not incorporated experiential modules such as scripture debate and meditation into the tourist participation system, resulting in a relatively low satisfaction level with “cultural immersive experience”.

- (2)

- The crisis of spectacularization in community interaction networks

The authentic living scenes in the neighborhood are being rapidly eroded by tourism commercialization [38]. Research shows that community businesses such as barbershops and grocery stores along Nanhong West Street have witnessed a substantial turnover rate in the past five years; in their place, the daily customer flow of cafes and cultural and creative stores has risen significantly. Such changes have resulted in the satisfaction rate with “residents’ living environment quality” dropping to −0.33, and have triggered multiple cultural inadequacies.

- (3)

- The dilemma of symbolization in the construction of emotional identity

Although the vast majority of tourists recognize the historical value of Fayuan Temple Block, the establishment of deep emotional connections still faces multiple barriers. The satisfaction rate regarding “Tourist Psychological Experience Identity” is only 0.4, exposing the intergenerational discontinuity in the carriers of cultural identity. Such phenomena stem from the mismatch of cultural decoding systems: the existing interpretation systems in the neighborhood still rely on text on display boards, while the coverage rate of digital experience projects such as AR and VR remains relatively low. Meanwhile, the physical loss of memory carriers has also exacerbated the identity crisis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Research Summary

4.1.1. Main Research Conclusions

This study, through the establishment of the LDA model, social network semantic analysis, and IPA analysis, confirms that tourists’ perception of Fayuan Temple Block presents a “core-periphery” hierarchical structure. Among which, historical buildings and ruins (with an attention rate of 25.39%) and historical figures and culture (32.72%) constitute the core elements of perception. However, the satisfaction with these two types of factors is significantly lower than the average level (P = −1.64/−3.32), exposing the issue of imbalance between “material preservation and cultural activation” in the current protection model.

Among the identified system of 6 perceptual dimensions, the dimension of residents’ life and activities exhibits a unique characteristic of “low attention—high satisfaction” (I = 5.78%, P = 2.09), indicating that authentic living scenarios have potential value in enhancing tourists’ cultural identity, yet their display method needs to break through the limitations of the current “landscaped performance” [39]. In the analysis and summary of this study, tourists’ satisfaction with material carriers (P = −1.64) is significantly lower than expected, revealing the structural contradiction between the current “static protection” model and the demand for “dynamic inheritance” [40].

The dimension of residents’ life exhibits the characteristic of “low attention—high satisfaction” (I = 5.78%, P = 2.09), which stands in contrast to the “high attention—low satisfaction” model in Xiong Anna’s [28] study on ancient towns. The IPA analysis shows that relevant elements in terms of natural landscapes fall into the “unsatisfactory zone”. In accordance with Article 24 of the Regulations on the Protection of Beijing as a Famous Historical and Cultural City [41], it is suggested that natural landscapes be incorporated into the auxiliary module of the “cultural exhibition system”. Therefore, the Fayuan Temple Historic District should attach greater importance to the protection and optimization of the natural landscape system.

4.1.2. Reflection and Summary

The physical space of historic districts is not a passive container but an active medium that shapes cultural perception and emotional experiences; conversely, non-material elements also define the function and value of the physical space. This study finds that in the Fayuan Temple Historic District, the physical space can provide people with rich emotional experiences.

For example, although the narrow scale of the hutongs may cause transportation inconveniences, it enhances the sense of community intimacy—a unique experience that broad streets cannot offer. However, such limitations of the physical space may also inhibit the development of contemporary non-material elements. For instance, the confined public spaces are not conducive to hosting activities, thereby creating an intrinsic tension between preservation and development.

Tourists’ and residents’ perceptions of space sometimes conflict. Field visits have revealed that residents attach greater importance to functional dimensions such as transportation and facilities, while tourists prioritize emotional dimensions like natural landscapes and cultural experiences. Therefore, optimization strategies need to strike a balance between the two.

For instance, in the IPA analysis, the element of “transport accessibility” has high importance but low satisfaction, which highlights the urgency of addressing this functional demand. However, over-satisfying this need—such as widening all roads—may damage the block’s historical texture, thereby undermining its unique emotional appeal as a tourist destination. Thus, optimization strategies should not rely on a single engineering mindset; instead, they must be the result of systematic consideration.

4.1.3. Similarities and Differences and Theoretical Extension

This study exhibits significant convergences and divergences with existing domestic and international research in terms of methodology, findings, and practical strategies. These similarities and differences provide critical perspectives for understanding both the uniqueness and universal applicability of the Fayuan Temple Historic District.

Methodologically, while this study aligns with most related research in adopting multi-source data fusion analysis and LDA topic modeling, it further constructs a three-dimensional “Physical-Cultural-Behavioral” IPA model, thereby expanding the traditional two-dimensional IPA framework. In terms of findings, this study highlights the critical impact of transportation system adaptability and landscape narrativity on tourist satisfaction—an aspect seldom systematically explored in previous research. Regarding non-material aspects, the study aligns with Wu Yun’s trinity theory of “culture-heritage-renewal.” However, Fayuan Temple exhibits a sharp contradiction of “high attention yet extremely low satisfaction,” contrasting with the “high attention-low satisfaction” pattern identified by Xiong Anna in ancient town studies, underscoring the urgency of cultural revitalization efforts [25].

Theoretically, this study quantifies “stratification” through perceptual data, providing empirical support for the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) theory. Ref. [42] proposed strategies such as “time-sharing shared streets” and “memory weaving” respond to the inclusivity and sustainability goals of SDG 11 [43]. Simultaneously, the study critically notes that digital revitalization must avoid disrupting historical authenticity, serving as a cautionary insight for current practices overly reliant on AR and VR.

Furthermore, as a core carrier of Xuan Nan culture, Fayuan Temple’s cultural stratification possesses distinct regional specificity, contrasting with commercially or aesthetically dominated districts such as Hangzhou’s Qinghefang and Nanjing’s Yihe Road. Consequently, this study emphasizes cultural depth and narrative continuity rather than mere spatial beautification or commercial intervention.

4.2. Pedestrian Space Optimization Strategy

Based on the previous analysis, the optimization of material elements in the neighborhood pedestrian space should take “preservation of historical genes, dynamic functional adaptation, and reconstruction of spatial resilience” as its core concepts. Focusing on the synergistic effects of spatial form restoration, transportation function iteration, and landscape system reconstruction, it provides a systematic solution for the optimization of material elements in the neighborhood pedestrian space. For the intangible elements of neighborhood pedestrian spaces, it is necessary to combine static preservation with dynamic production, so as to inherit historical genes, living scenarios, and cultural identity. While reconciling traditional texture with modern travel needs, it realizes the symbiosis of ecological restoration and cultural narration [44].

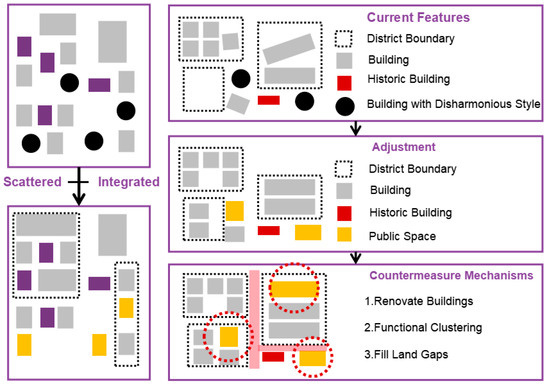

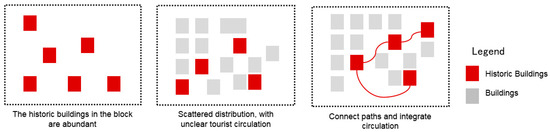

4.2.1. Protection of Neighborhood Spatial Form and Layout

In response to the issue of insufficient stratification of historical relics in the neighborhood, a multi-dimensional protection system should be established. During the optimization process, large-scale renovations that damage the overall texture of the historical neighborhood should be avoided, so as to ensure the continuity of historical memory and the preservation of cultural characteristics (Figure 11). Through micro-adjustments rather than macro-transformations, street functions are effectively updated to meet the transportation and living needs of modern society. By integrating building age databases with 3D laser scanning technology, precise surveying, mapping and classification of buildings from different periods within the neighborhood are conducted, and differentiated style control zones are demarcated.

Figure 11.

Restoration of Neighborhood Texture. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

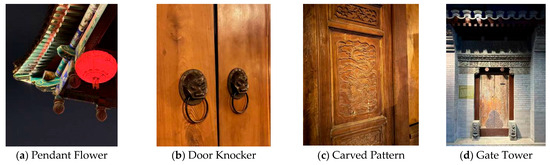

The neighborhood can establish “one courtyard, one policy” guidelines: for intact siheyuan (quadrangle courtyards), their original layout shall be retained, with customized components provided to restore chuihua men (pendent-flower gates) and chaoshou corridors (winding verandas); for mixed courtyards, flexible partitions such as folding screens and mobile green walls shall be adopted to reshape the spatial sequence (Figure 12). In the protection process, efforts should be made to maintain the original scale, proportion and interrelationships of buildings as much as possible, so as to ensure the harmonious unity between the internal buildings of the neighborhood and the external environment. Explore the needs of diverse groups and simultaneously implement the “Memory Weaving Project”: set up story collection stations in the renovation area, generate digital archives of residents’ oral histories through speech recognition technology, and convert them into the content source of the neighborhood’s QR code navigation system.

Figure 12.

Components of Siheyuan Courtyard. Figure Source: Taken by the author.

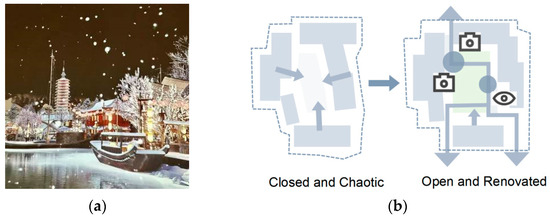

4.2.2. Composite Functions and Usage Optimization of Transportation

In the protection process, efforts should be made to maintain the original scale, proportion and interrelationships of buildings as much as possible, so as to ensure the harmonious unity between the internal buildings of the neighborhood and the external environment (Figure 13). Explore the needs of diverse groups and simultaneously implement the “Memory Weaving Project”: set up story collection stations in the renovation area, generate digital archives of residents’ oral histories through speech recognition technology, and convert them into the content source of the neighborhood’s QR code navigation system. Isolation facilities adopt a multifunctional design: for example, during restricted traffic hours, they can flip out to display exhibition boards of historical chronologies, and reset as cast-iron seats during regular hours. By utilizing modular facilities, flexible switching can be achieved between neighborhood leisure, sports, or cultural activities.

Figure 13.

Cultural Resource Identification and Spatial Connectivity. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

4.2.3. Symbiosis Between Landscape Ecology and Narrative Experience

The optimization of plant landscapes adheres to the principle of organic renewal in historical neighborhoods [45], integrating temporal sequence, cultural significance, and participatory elements into space creation. Based on the original spatial pattern, a cultural narrative system centered on native plants is constructed. The core area continues the landscape characteristics of Fayuan Temple’s historical axis, preserving the classic configuration of Tang Dynasty ginkgoes and Qing Dynasty lilacs.

Drawing on the conservation techniques recorded in Records of Fayuan Temple, traditional horticultural methods are employed to shape the texture. The buffer zone can supplementarily plant Chinese flowering crabapples in accordance with such documents as Qiu Haitang Fu (Ode to Chinese Flowering Crabapple). Through community horticultural workshops, poetry-themed tree pits will be jointly built, integrating ecological facilities like permeable pavements and rain gardens. The transition zone adopts modular planting units to assemble landscape patterns featuring “Xuannan Culture”. Combined with reversible pavement materials, dynamic adjustment of the patterns can be achieved, which reduces maintenance costs and enhances public participation.

Meanwhile, a plant community construction system guided by narrative space theory should be established. In accordance with the protection requirements for historical environmental elements specified in the Regulations on the Protection of Beijing as a Famous Historical and Cultural City, emphasis should be placed on extracting cultural symbols bearing collective memories such as “ancient Chinese scholar trees” and “Lilac Poetry Society”.

Through plant configuration, the historical landscape characteristics of “flowers and trees in Zen forests” are reproduced. Native and adaptable plants are adopted to construct a complex community structure, with Chinese scholar trees and lilacs as the mainstay, supplemented by traditional ornamental varieties such as wisteria and Chinese roses, thus forming a three-dimensional landscape interface with temporal variations (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Plant Species Distribution in Lanman Hutong. Figure Source: Drawn by the author.

4.2.4. Constructing “Time-Space Narrative—Digital Activation”

In response to the structural contradiction of “high perception degree (10.90%) and low satisfaction degree (−1.61)” in the neighborhood’s guild hall site group, and aiming at the imbalance between cultural perception degree and experience satisfaction degree presented by the guild hall site group, the cultural narrative network [46] can be reconstructed through a smart navigation system. IoT sensing devices are deployed at key nodes such as Liuyang Guild Hall and Shaoxing Guild Hall to establish a dynamic cultural communication matrix (Figure 15a).

Figure 15.

Digital Technology Integration. Figure Source: Taken and drawn by the author. (a) Augmented Reality Technology Demonstrating the Urban Vigor along Yangzhou Canal. (b) Sensing Facilities Promoting Tourist Activities.

When visitors enter the sensing range, it triggers the immersive restoration of historical scenes based on augmented reality (AR) technology. Visitors collect six virtual cultural markers along the movement trajectory of historical figures (such as digital archives like fragments of the manuscript of Ren Xue (On Benevolence) and copies of the Wuxu Secret Edict). After collecting all of them, they can activate the holographic image narrative theater at the site of Fuzhou Guild Hall, realizing the situational reproduction of historical events (Figure 16). They can build a community co-creation platform and construct a cultural memory database that includes modules such as dynamic maps of old photos restored by AI and audio-scene archives of oral histories (Figure 15b). By curating temporary cultural installations and creating a festive atmosphere, it can effectively enhance the cultural identity and sense of belonging among residents and tourists.

Figure 16.

Ground Memory Pegs. Figure Source: Taken by the author. (a) Industrial Elements of Shaanxi Old Steel Factory. (b) Ground Building Information of Zhongshan Road in Qingdao.

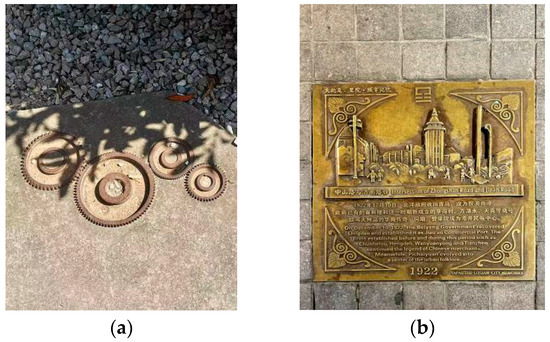

4.2.5. Translating the Symbol System of “Cultural Genes”

Construct a historical memory activation system based on tactile perception, and guide micro-renewal practices through catalyst theory [47]. Adopt “stratified tactile coding” technology to embed memory stakes in the ground. By setting up inscriptions of historical stories or information points, the neighborhood’s past is effectively recorded and displayed (Figure 16). Using old photos to show the changes in the neighborhood is an intuitive way to visualize history, which profoundly evokes residents’ imagination and memories. Through the oral history of neighborhood residents, emotional bonds between different generations are strengthened, providing experience for future development and continuity of a sense of belonging.

Streets and squares are utilized to provide residents with spaces for activities such as sports and fitness, further enhancing community residents’ health awareness and quality of life. Furthermore, community public spaces are used to carry out artist-in-residence programs, encouraging artistic creation and exhibition, and creating dynamic cultural communities [48].

4.3. Theoretical Implications Based on the Global Framework

In the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (2011) released by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the HUL (Historic Urban Landscape) approach emphasizes integrating the protection and management of cultural heritage into broader urban sustainable development goals, while attaching importance to stratification and community participation.

The multi-dimensional perception system constructed in this study is highly aligned with the holistic approach advocated by HUL. The research practice on Fayuan Temple Block in this study provides a specific and operable assessment tool for the HUL theory—one that quantifies the value and contradictions of “historical stratification” through public perception data. Furthermore, the results of the IPA analysis clearly identify which elements are “priority areas” for protection and development, such as the maintenance of community vitality. This provides an empirical basis for the “management transformation” in the HUL concept and holds reference value for other historical urban areas worldwide facing similar development pressures.

The UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), aim to make cities and human settlements more inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. The optimization strategies proposed in this study directly contribute to the achievement of SDG 11: “Transportation and Functional Optimization” is intended to enhance the block’s safety and inclusivity for residents, tourists, and people with disabilities; “Landscape-Ecological Symbiosis” is tied to environmental sustainability and resilience; “Cultural Gene Translation” strengthens the community’s cultural identity and inclusivity.

Therefore, the optimization of Fayuan Temple Block is not just a local project, but more significantly, a microcosm and practical case of how China’s historical cities are advancing toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

5. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the evaluation of the material and intangible pedestrian space systems in Fayuan Temple Block. Through the extraction of online review data, the distribution of on-site questionnaires, and the collection of data and reviews, it conducts sentiment network analysis, as well as analysis of connections and evaluations between word meanings. By means of LDA model, social network semantic analysis, and IPA analysis, it obtains the degree of attention and satisfaction of tourists towards the material and intangible elements of Fayuan Temple Block. Based on the analysis results, further material improvement strategies are proposed: protection of the block’s spatial form and layout, optimization of transportation’s composite functions and utilization, and symbiosis of landscape ecology and narrative experience.

Meanwhile, intangible improvement strategies are put forward: constructing “time-space narrative—digital activation” immersive scenes, and translating the symbol system of “cultural genes”. By integrating the material and intangible aspects, it aims to comprehensively enhance tourists’ spatial perception experience in Fayuan Temple Historical Pedestrian Block.

5.1. Research Content and Limitations

In the research, constrained by economic factors and the limitations of new methods, there are also the following issues:

- (1)

- Constraints on the timeliness of data

Constrained by the data storage policies of social media platforms, the retention period for historical posts on channels such as Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin is generally only 1–3 years, with significant attenuation in both the call frequency and field completeness of early data. Although the research team attempted to supplement samples from before 2015 through web crawlers and third-party data providers, it could only obtain fragmented information accounting for less than 5% of the total volume, resulting in obvious gaps in the time series before 2018.

- (2)

- Lack of segmentation of tourist types

This study did not distinguish between subcategories of tourists (e.g., cultural tourists and daily visitors). Its methodological limitations stem from the fact that online data can only provide anonymized texts and geotags, failing to offer demographic information such as gender, age, educational background, and consumption level contained in user profiles. Due to the lack of fine-grained tags like POI dwell time, model of photography equipment, and text sentiment polarity, it is difficult to analyze the micro-mechanisms underlying the perceptual differences among different groups [49].

- (3)

- Limitations of spatial scale and theoretical framework

The analysis of spatial dimensions is limited to the street and alley scale, mainly focusing on microscopic elements such as block squares, facades, and installations, while lacking coupling with community/urban-level data. The study only collected perceptual data from the interior of Fayuan Temple and its adjacent streets, failing to introduce macro variables such as nearby population density, distribution of colleges and universities, and bus routes. Thus, it is unable to reveal the multi-scale spatial interaction effects of “park—community—city”.

5.2. Future Outlook

Regarding issues such as insufficient data timeliness, lack of segmentation of tourist types, and limitations in spatial scale theories, future efforts need to deepen research on the collaborative mechanisms of “policy, technology, and society” [50], explore innovative tools such as “micro-renewal funds” and “cultural property rights transactions”, formulate standards for dynamic monitoring and flexible management and control, and promote the transformation of strategies from conceptual innovation to operational institutional design. Subsequent studies need to select multiple types of relevant cases for comparison, refine classified optimization paradigms for different dominant functions such as “residence, cultural tourism, and commerce”, and enhance the adaptability and guiding value of the strategies. Future studies also need to introduce cultural geography [51] and spatial narrative theory [52], establish a standardized framework for the perception evaluation of historical blocks, and strengthen the explanatory power of theories for complex practical scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. (Qin Li); methodology, Y.L. (Yanwei Li); software, Q.L. (Qiuyu Li); formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, Y.L. (Yijun Liu); resources, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing Social Science Foundation Project: No. 24JCC077, the Subject of Beijing Association of Higher Education: No. MS2022276, the Research Project of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture: No. ZF16047 and the BUCEA Post Graduate Innovation Project: No. PG2025009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Committee of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture (2108510023049) on 5 August 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shaomin Peng was employed by the company Beijing Jinyu Jiaye Real Estate Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- The General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued the “Cultural Development Plan for the 14th Five—Year Plan Period”. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-08/16/content_5705612.htm (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Design Guidelines for the Conservation and Renewal of Historical and Cultural Blocks in Beijing. Available online: https://ghzrzyw.beijing.gov.cn/biaozhunguanli/bzxg/201912/P020191213652324033184.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Solid Progress in New-Type Urbanization and Steady Improvement in Urban Development Quality—Series Report on Economic and Social Development Achievements Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China: No. 12. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/jd/sjjd2020/202209/t20220929_1888803.html (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Statistical Communiqué on Cultural and Tourism Development 2023 by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/tjxx/202408/t20240830_954981.html (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Tan, Z.N.; Tang, B.; Yi, S.Y.; Wang, Z.G. Planning and Design of Hezhou Garden Expo Park from the Perspective of Contextual Continuity. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2021, 49, 124–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Y. The Role of Tourism in Urban Renewal from the Perspective of Cultural and Tourism Integration. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 8–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detailed Regulatory Plan for the Core Functional Area of the Capital (at the Block Level) (2018–2035). Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/202008/t20200828_1992592.html (accessed on 2 August 2020).

- Choi, S.; Walter, R.J.; Chalana, M.J.C. Untangling our checkered past: Investigating the link between local historic district designation and spatial segregation history. Cities 2025, 158, 105621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, C.X.; Rui, G.Y. Study on the Formulation Method of Conservation Planning for Historical and Cultural Blocks from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)—A Case Study of Fengyuan Street-Liwan Lake Historical and Cultural Block in Guangzhou. Planners 2020, 36, 66–72+85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.G. Exploration on Adaptive Conservation, Renovation and Vitality Regeneration Paths of Historical and Cultural Blocks—A Case Study of Gunan Street in Dingshu, Yixing. Archit. J. 2021, 05, 1–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Qian, X.J.; Lin, Q.; Wang, X.R. Study on “Authenticity” Perception Evaluation and Renewal Strategies of Canal Historical and Cultural Blocks (Famous Towns) Based on Multi-Source Data. Mod. Urban Res. 2021, 7, 20–27+37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.H.; Tang, P.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.C. Construction and Application of a Multi-Scale Hierarchical Structure Analysis Model for Historic Districts—A Case Study of Hehuatang Historical and Cultural Block in Nanjing. Archit. J. 2023, 10, 55–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chi, F.A. “Conservation and Renewal of Historical and Cultural Blocks: Theoretical Exploration and Huzhou Practice”: Summary of Theories and Practical Application in Conservation of Historical and Cultural Blocks. Archit. J. 2024, 03, 127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Z. Study on Optimization of Walking Environment in Living Streets Based on Landscape Preference Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. PEST Analysis of Historical and Cultural Block Research and Suggestions on Renewal Strategies. China Anc. City 2024, 38, 67–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Reference of Paris’ Historical Style Conservation for Beijing’s Urban Construction. Master’s Thesis, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China, 2005. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. Study on the Internal Mechanism and Methods of Urban Design Control Based on Digital Platforms. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Qi, K.; Wang, C.K. Insights from Japan’s Arcade Shopping Streets for the Renovation of Traditional Blocks in China. Mod. Urban Res. 2011, 26, 49–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Re-theorising contemporary public space: A new narrative and a new normative. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 8, 373–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppa, M.; Bawazir, K.; Alawadi, K. Walking the superblocks: Street layout efficiency and the sikkak system in Abu Dhabi. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-González, C.; Ekambaram, K.; Rey-Galindo, J.; Rizo-Corona, L. The role of perceived pedestrian safety on designing safer built environments. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2020, 21, S84–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi Juzdani, M.; Morgan, C.H.; Schwebel, D.C.; Tabibi, Z. Children’s Road-Crossing Behavior: Emotional Decision Making and Emotion-Based Temperamental Fear and Anger. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenchak, N.N.; Marshall, W.E. Quantifying suppressed child pedestrian and bicycle trips. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 20, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Yu, L.; Ziran, D.; Shun, S. Behavior pattern mining based on spatiotemporal trajectory multidimensional information fusion. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.R.; Kundroo, M.A.; Tarray, T.A.; Agarwal, B. Deep LDA: A new way to topic model. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2020, 41, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Machado, W.; Torres-Salinas, D.; Robinson-Garcia, N. Identifying and characterizing social media communities: A socio-semantic network approach to altmetrics. Scientometrics 2021, 126, s11192-s021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimbs, B.P.; Boley, B.B.; Bowker, J.; Woosnam, K.M.; Green, G.T. Tourism. Importance-performance analysis of residents’ and tourists’ preferences for water-based recreation in the Southeastern United States. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.N. Study on Evaluation and Optimization of Landscape Image of Famous Historical and Cultural Towns from the Perspective of Tourist Perception. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Fu, J.; Shao, G.F.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Yang, P.P. Insights into citizens’ experiences of cultural ecosystem services in urban green spaces based on social media analytics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 244, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Tan, L. Evaluation of Landscapes and Soundscapes in Traditional Villages in the Hakka Region of Guangdong Province Based on Audio-Visual Interactions. Buildings 2025, 15, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Hu, L.; Wu, J.; Shan, Q.; Li, W.; Shen, K. Investigating the Influencing Factors of the Perception Experience of Historical Commercial Streets: A Case Study of Guangzhou’s Beijing Road Pedestrian Street. Buildings 2024, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączkiewicz-Wronka, A.; Wronka-Pośpiech, M. How Practices of Managing Partnerships Contributes to the Value Creation—Public–Social Partnership Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X. Uneven development and tourism gentrification in the metropolitan fringe: A case study of Wuzhen Xizha in Zhejiang Province, China. Cities 2022, 121, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H. Research on Tourist Demand Identification Method Based on LDA and Kano-IPA Model. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Jilin, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.X. Discussion on the Physical and Functional Protection of Historical Districts: A Case Study of the Renovation of Chengdu’s Kuanzhai Alle. Intell. Build. Smart City 2020, 07, 123–124+131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.R.; Chen, K.Y.; Jiao, K.; Li, Z.X. Spatio-temporal characteristics of traditional village landscape pattern and its influencing factors from the perspective of tourism development: A case study of Huangcheng Village, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.C.; Liu, R.Q. Research on the working methods of responsible planners in Beijing’s historical and cultural districts—taking the Xuanan historical and cultural district in Beijing as an example. Urban Archit. Space 2024, 4, 71–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, S. Social conflicts and their resolution paths in the commercialized renewal of old urban communities in China under the perspective of public value. J. Urban Manag. 2025, 14, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.L.; Huang, C.H.; Wei, H.B. Recreating historical contexts: Methods and strategies for the restoration of the ‘spatio-temporal landscape’ of Ao Garden in Xiamen, Fujian Province, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 4103–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.H.; Zhang, R.C. From static to dynamic: The protection of vernacular architectural heritage from the perspective of eco-museums. Archit. Cult. 2020, 10, 205–207. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]