Abstract

Office is one of the core sectors within the buildings sector, attracting tens of billions of dollars in global real estate investment flows. Most of these are achieved through non-listed investments, where office real estate represents one of the major sectoral investment exposures for many global institutional real estate investors and investment managers. The rising interest rates in recent years have been a significant concern, impacting the global real estate markets significantly. Based on these premises and by using quarterly total returns of non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia from June 2008 to June 2024, this research assesses the risk-adjusted performance and portfolio diversification benefits of non-listed office real estate across the five markets over both interest rate cut and interest rate hike cycles. The results empirically validate the added-value role of non-listed office real estate in institutional multi-asset portfolios across the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia during the interest rate hike cycle preceding the COVID recession. In the 10% capped real estate allocation, the average allocation was 0.7% in the UK, 0.4% in Germany, 0.7% in Canada, and 9.1% in Australia. Over the interest rate hike cycle after the COVID recession, Australian non-listed office real estate offered enhanced benefits as part of the multi-asset portfolio, constituting an average of 0.8% in the capped real estate allocation. In the global non-listed office real estate portfolio, the US dominated the portfolio across varying interest rate cycles, with an average allocation of approximately 65%. The average allocation to Australia was 24.2% over the interest rate hike cycles, while the average allocation to Germany was 32.0% over the interest rate cut cycles. These findings offer institutional real estate investors and investment managers critical and practical insights into how the investment performance and portfolio construction strategy of office assets—an essential component of the buildings sector and a major non-listed real estate investment exposure for global institutional real estate investors—respond to macro-financial and interest rate cycles. The investment implications of the findings are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Increases in interest rates have become a major issue for stakeholders in global real estate investment markets. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, the accumulation of government debt across global capital markets has contributed to a sustained inflationary environment since late 2021 [1,2,3]. Since the initial rate increases, major central banks worldwide have adopted a more restrictive monetary stance, implementing substantial hikes in policy rates. The Federal Reserve raised rates by 525 basis points, followed by the Bank of England (500 basis points), the European Central Bank (450 basis points), the Bank of Canada (475 basis points), and the Reserve Bank of Australia (425 basis points) [4]. Office real estate is a key sector within the built environment and buildings industry, and it has been substantially affected by the recent global interest rate hike cycle. This tightening cycle placed upward pressure on capitalization and discount rates, which in turn exerted downward pressure on office real estate asset values [5,6,7]. For example, between March 2022 and June 2024, office real estate asset values declined across the US (−29.2%), UK (−19.5%), Europe (−14.1%), Canada (−28.2%), and Australia (−26.8%) [8]. In 2024, institutional investors were under allocated to real estate, with allocations below target in the Americas (50 bps), EMEA (10 bps), and Asia-Pacific (160 bps) [3].

While a highly volatile investment context for commercial real estate investors has persisted due to major geopolitical uncertainties (e.g., the Russia-Ukraine war, Middle East conflicts, trade disputes, etc.), the post-pandemic inflationary climate stabilized by late 2024 [3]. In response, global key central banks implemented interest rate cuts. As global key central banks’ tightening monetary policy has turned a corner, office real estate quarterly returns moved into a positive territory in September 2024, including the US (1.7%), UK (0.5%), Germany (0.1%), Canada (1.6%), and Australia (4.3%) [8]. The ANREV 2025 industry survey shows that more than one-third of global institutional investors plan to increase real estate allocations in the next two years [9]. The year 2025 is expected to open a window for institutional investors to tactically rebalance their real estate allocations [3]. Overall, these trends highlight the substantial impacts of interest rates on office real estate investment, particularly for asset value growth and capital returns [2]. The ANREV/INREV/PREA 2025 industry survey highlights interest rate policy continuing as the most critical investment concern for global institutional real estate investors in 2025 [9].

In the real estate investment context, the IPE 2024 industry report shows prominent global real estate investors include Allianz (Germany), Government Investment Corporation (GIC, Singapore), China Investment Corporation (CIC, China), Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA, the United Arab Emirates), and Government Pension Fund Global (GPFN, Norway), as exhibited in Table 1. The INREV 2025 industry survey reports that non-listed real estate investment has become a significant investment conduit for institutional real estate investors, including pension funds (43% of total global non-listed real estate investment by capital in 2024), insurance companies (19%), sovereign wealth funds (7%), and government institutions (5%), to achieve their real estate allocations, accounting for USD 3.7 trillion in 2024 [10]. The Nuveen 2025 industry report documents that these institutional real estate investors typically allocate capital in real estate at rates of 10.5% in the Americas, 10.3% in EMEA, and 9.3% in the Asia-Pacific [3]. A variety of investment vehicles, such as non-listed real estate funds, separate accounts, joint ventures, club deals, and funds of funds, further support non-listed real estate investment. In the non-listed real estate investment space, office real estate is listed as one of the main sector exposures for global non-listed real estate investment [9,11,12,13]. Table 2 shows prominent non-listed office real estate investment managers across the regions in the IPE 2024 industry report. American-focused major office real estate investment managers include Brookfield Asset Management (USD 46.9 billion in 2024), Hines (USD 32.7 billion), Nuveen Real Estate (USD 23.4 billion), JP Morgan Asset Management (USD 19.2 billion), and New York Life Real Estate Investors (USD 16.3 billion). European-focused major office real estate investment managers are named Deka Immobilien Investment, PIMCO Real Estate, Swiss Life Asset Management, AXA Investment Managers, and DWS Asset Management. Asia-Pacific-focused major office real estate investment managers are ESR Group (USD 17.3 billion), Charter Hall (USD 15.1 billion), Mapletree Investments (USD 11.8 billion), CapitaLand Investment (USD 11.4 billion), and Gaw Capital Partners (USD 10.8 billion).

Table 1.

Major global real estate investors: 2024.

Table 2.

Major global non-listed office real estate investment managers: 2024.

Despite significant investments from institutional investors in real estate, the limited availability of robust data for non-listed real estate has led to a scarcity of studies discussing the investment performance of composite non-listed real estate [15,16,17]. Limited studies focused on investment performance comparisons (e.g., annual total returns) between non-listed office real estate and other non-listed real estate subsectors at a single market/region level [13,18,19]. However, prior research on non-listed real estate has yet to be devoted to investment opportunities and tactical portfolio construction rebalancing strategies for non-listed office real estate across global markets and various interest rate cycles. This is despite the acknowledgment of differential real estate investment performance across global markets [20,21], as well as interest rate risk being identified as a crucial factor in real estate investment [22,23,24]. Hence, it is necessary to offer an empirical analysis of the investment performance and portfolio construction strategy for non-listed office real estate across global markets and varying interest rate cycles, using the mean-downside risk portfolio framework to address the highly turbulent investment risk associated with interest rate cycles.

This study extends existing literature to examine the impacts of interest rate cycles on portfolio construction strategies for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia, given that these five major markets accounted for more than 45% of the global commercial real estate markets by market capitalization in 2024 [25]. Therefore, three research questions (RQ) have been formulated to satisfy the aims of this paper, as follows:

RQ 1. How does global non-listed office real estate performance vary across different interest rate cycles?

RQ 2. What role does global non-listed office real estate play in multi-asset portfolio construction when accounting for shifts in interest rate regimes?

RQ 3. How do allocation strategies within global non-listed office real estate portfolios adjust across interest rate cycles, particularly during the most recent tightening phase after 2022?

This study makes a significant contribution to the literature in several ways. First, it provides a comprehensive and evidence-based analysis of the investment characteristics and portfolio construction strategies for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia under different interest rate cycles. Unlike previous research (e.g., [13,18,19]), which primarily examined return performance over limited timeframes, this study extends these studies by systematically assessing how non-listed office real estate behaves and contributes to portfolio strategies across multiple interest rate regimes. Second, this paper explicitly incorporates the dynamics of the most recent tightening cycle post-2022, which has not yet been captured in existing studies. This allows for timely insights into how rapidly rising interest rates influence the risk–return profiles and portfolio roles of non-listed office real estate. Third, by applying portfolio theory in both multi-asset and global non-listed office real estate portfolios, this study extends the literature beyond simple performance measurement. It evaluates the strategic and tactical implications of allocating to non-listed office real estate under varying macro-financial conditions, thereby offering a richer understanding of its role for institutional real estate investors. Lastly, this study employs a downside risk framework, rather than relying solely on mean–variance analysis, to evaluate the investment performance of the non-listed office funds. This approach is particularly relevant in the current environment of heightened macroeconomic and financial uncertainty, as it provides a more realistic assessment of risk exposure and hedging potential. Essentially, this paper offers both theoretical and practical insights into investment implications. The following section reviews relevant literature to establish the conceptual foundations for this study.

2. Literature Review

As an opening note, there is a paucity of research on non-listed office real estate investment, as the sector operates within an illiquid, thinly traded, and opaque market, making performance data difficult to obtain. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that comprehensive performance tracking of non-listed office real estate only began in recent years, with limited historical data available for comprehensive analysis. Compared to listed real estate investments, researchers have had to rely on fragmented datasets, limited industry benchmarks, and proprietary indices, many of which lack transparency and consistency. Consequently, this has hindered the development of robust models capable of accurately assessing the performance characteristics of non-listed office real estate in comparison to other asset classes. The following sections highlight some relevant research in two areas: (1) non-listed office real estate investment performance and (2) the impacts of interest rates on non-listed office real estate investment performance.

2.1. Non-Listed Office Real Estate Investment Performance

In a private real estate investment performance context, many studies have focused on the composite non-listed real estate funds based on their investment style/strategy. In the US, higher-levered value-add and opportunity real estate funds provided slightly compelling performance compared to core funds [26,27,28,29]. In Europe, a similar market trend between core and value-add non-listed real estate funds was observed by [30]. In Japan, non-listed value-add real estate funds delivered compelling results as part of multi-asset portfolio strategies [15]. In China, non-listed opportunity real estate funds were observed to underperform the mainstream asset classes [17]. However, neither of these studies includes core non-listed real estate funds for comparisons because of limited data availability for indexing purposes.

In addition to the style/strategy of investment, non-listed real estate funds differ in terms of portfolio value, gearing ratio, and, importantly, country and sectoral exposure. Previous research has discovered that non-listed real estate fund characteristics possessed significant explanatory power in predicting performance. [16] estimate a positive impact of the fund size on European non-listed real estate funds’ performance, while fees were a negative explanatory variable. Also, the leverage level was positively associated with the returns of core funds, but not with those of value-add funds. These results generally align with the results of [31,32]. Also, [33] found that both market and economic factors acted as performance determinants. One key limitation is that the non-listed real estate fund samples utilized in previously cited research were mostly sector-agnostic. These studies do not differentiate non-listed composite funds based on the underlying real estate sectors in their portfolios, particularly with a focus on the underlying office real estate held by non-listed funds. This is despite the sectoral effect implying the fact that office real estate and other real estate subsectors feature distinct risk-return characteristics [34,35]. This has been one of the key limitations in the current body of knowledge.

The literature on the sectoral effect has primarily focused on listed office real estate due to the availability of in-depth data on Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and Real Estate Operating Companies (REOCs) [36]. At a sector level, previous research mainly examines the investment performance of listed office real estate compared with other listed real estate subsectors across the US [37], Australia [38], Japan [20], Asia [39], Europe [24], and the Globe [21].

Literature on non-listed office real estate is sparse, although this investment pathway is gaining traction among sophisticated institutional investors from a portfolio rebalancing strategy perspective [40]. As noted previously, the limited number of non-listed real estate data series presents a major obstacle to conducting comprehensive empirical analyses, as it restricts the availability of robust data necessary to assess the investment attributes of non-listed real estate effectively. To the best of our knowledge, the following studies are among the most relevant and closest to date. The US non-listed real estate vehicles specializing in the office sector were found to underperform due to their high development exposure [12,18]. European non-listed sector specialization real estate funds did not guarantee outperformance [11,19]. Ref. [13] explains that European non-listed sector specialization real estate funds lacked the mandate to diversify into other real estate sectors and therefore may implement alternative strategies, such as increasing geographical diversification, optimizing tenant mix, and deleveraging. However, no study focus on an added-value role played by non-listed office sector in institutional investors’ portfolios across global markets to highlight the investment distinctions across various markets in the Globe, and a global non-listed office real estate portfolio to echo that international institutional investors practically and tactically implement a mandate to construct cross-market real estate portfolios to gain geographical diversification effectiveness from various investment jurisdictions [3].

2.2. Impacts of Interest Rates on Non-Listed Office Real Estate Investment Performance

After the Federal Reserve’s first rate increase in March 2022, global non-listed office real estate values fell markedly, with MSCI recording a 22.2% drop between March 2022 and June 2024 [8]. A vast body of evidence shows that higher interest rates raise borrowing costs for real estate fund managers, push up required yields, capitalization rates, and discount rates on future cash flows, and thus reduce capital values. These repricings also affect lease structures and occupier demand, occasionally leading to excess supply in particular sub-markets [5,6,7,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Although several studies investigate the impacts of interest rate movements on both private and listed real estate, few drill down to the sector level despite the recognised importance of sectoral distinctions [23,34,35,36,38,44,48,49,50]. No study has yet focused exclusively on non-listed office portfolios; the nearest parallels concern listed office vehicles, as seen in [24,51].

The core focus of this study is to examine portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate in both global multi-asset portfolios and global non-listed office real estate portfolios across different interest rate cycles. This is despite the fact that prior studies, such as [12,19], analyzing US non-listed office real estate performance by using relatively short samples (December 2008–December 2012 and December 2009–December 2013, respectively, each with 17 quarterly observations), did not empirically investigate the influence of interest rate cycles on portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate. In contrast, this study leverages a global dataset that extends beyond US markets and provides sector-specific analysis focused on office real estate. By explicitly examining how interest rate cycles affect portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate, this study offers a combination of global scope, sector specificity, and cycle-based insight, representing a meaningful contribution to the literature.

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

This study draws on portfolio theory [52] and sectoral real estate risk-return theory [34,35] to examine investment attributes and portfolio allocation strategy for global non-listed office real estate.

From a portfolio perspective, institutional investors allocate capital to assets to maximize risk-adjusted returns for a given level of risk. Non-listed office real estate exhibits distinct characteristics due to illiquidity, limited transparency, and infrequent valuation. Interest rate cycles influence these characteristics through multiple channels: borrowing costs, discount rates on future cash flows, and broader economic conditions, all of which affect property values and expected returns [41,42]. Higher interest rates increase the cost of capital and reduce expected returns, leading to lower portfolio allocations, whilst lower rates increase dry powder volumes and stimulate higher portfolio allocations.

2.3.1. Hypothesis 1 (H1—Research Question 1)

Portfolio allocations to global non-listed office real estate are sensitive to interest rate cycles, with higher rates reducing portfolio allocation weights and lower rates increasing them, reflecting changing investment attributes under varying macroeconomic conditions.

From a sectoral perspective, office real estate differs from other subsectors in lease structures, tenant stability, and sensitivity to economic cycles [34,35]. Non-listed office real estate also carries idiosyncratic risks not captured by composite or sector-agnostic indices [32,33]. Sector-specific risk-return attributes, together with market-specific conditions, determine the optimal allocation within institutional portfolios, enabling investors to optimize risk-adjusted returns by rebalancing allocations across sectors, markets, and interest rate cycles.

2.3.2. Hypothesis 2 (H2—Research Question 2)

Within global multi-asset portfolios, institutional real estate investors rebalance portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate across interest rate cycles to optimize risk-adjusted returns, reflecting tactical portfolio rebalancing strategies.

Non-listed office real estate markets differ substantially across markets due to variations in market liquidity, regulatory frameworks, economic conditions, and sectoral compositions. These cross-country differences suggest that global institutional real estate investors must consider market-specific characteristics when constructing multi-asset portfolios that include non-listed office real estate.

2.3.3. Hypothesis 3 (H3—Research Question 3)

Within global non-listed office real estate portfolios, portfolio allocation weights vary across interest rate cycles due to sector-specific risk-return attributes and differing market conditions across major markets (the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia), enabling institutional real estate investors to optimize risk-adjusted returns within the sector.

This theoretical framework positions non-listed office real estate portfolio allocation as a function of interest rate cycles, sector-specific risk-return characteristics, and portfolio optimization strategies, providing a foundation for the empirical analysis of global portfolio allocation to non-listed office real estate in this study.

Overall, this study extends the literature in numerous ways. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to empirically examine portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate across various markets and interest rate cycles. This is despite the existing literature having primarily focused on portfolio allocations to private and public real estate within multi-asset portfolios across various investment timeframes. Secondly, an empirical analysis of portfolio allocation within non-listed office real estate in the aftermath of the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic is examined for the first time. In particular, this study’s analysis captures the interest rate cut cycle during the COVID-19 recession stimulus package and the interest rate hike cycle after the COVID-19 recession stimulus package, in which the US fund rate hike cycle is the sharpest rise in the past 35 years, with an increase of 5% over just 14 months [4]. Thirdly, this paper is the first to assess portfolio construction strategies for global non-listed office real estate portfolios, reflecting that global real estate investors have a mandate to build cross-market real estate portfolios from a practical perspective. Lastly, a key innovation of this research is the estimation of portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate for the first time, utilizing the mean-downside risk portfolio analysis in highly volatile investment environments. The mean-downside risk portfolio analyses of non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia are discussed in the following sections.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Description

Table 3 provides descriptions of the data series used for the analysis. Quarterly total returns were assessed for non-listed office real estate, other non-listed real estate subsectors (including retail, industrial, and residential), stocks, and bonds across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia from June 2008 to June 2024. The use of non-listed office real estate index series across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia was the MSCI/PREA US All Funds—Open-end (AFOE) index, MSCI Global Property Fund Index (PFI) UK Funds Property Index, MSCI Germany Spezialfonds index (SFIX) Property Fund Index, MSCI/REALPAC Canada PFI Funds Property Index, and Property Council of Australia (PCA)/MSCI Australia Core Wholesale Property Index, respectively. Over the interest rate cut cycle from June 2008 to September 2015, the residential index was only available for the MSCI Global PFI UK Funds Property Index since Dec-11. Retail, industrial, and residential indices were only available for the MSCI Germany SFIX Property Fund Index since March 2009, September 2012, and September 2009, respectively. Therefore, the UK residential and German retail, industrial, and residential sectors were excluded from the sub-period analysis over the period to harmonize the five market subsector datasets to a common availability window. In addition, over the interest rate hike cycle from March 2022 to June 2024, the industrial index had incomplete data points on March 2022 and June 2023 for the MSCI Germany SFIX Property Fund Index. Hence, the German industrial sector was excluded from the sub-period analysis over the period to harmonize the five market subsector datasets to a common availability window. The residential index was unavailable for the PCA/MSCI Australia Core Wholesale Property Index over the whole study period. Hence, the Australian residential sector was excluded from the entire sub-period analyses. The non-listed office real estate total return series are underlying office real estate held by core and value-add non-listed real estate funds, in open- and closed-end channels, across all five markets. These asset-level index series are unlevered and unaffected by fund-level issues, such as cash holdings and performance fees. The MSCI stock market index, ten-year government bond yield, and three-month treasury bills represented the stock, bond, and cash asset classes across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia, respectively. The total returns for each asset were measured every quarter. The analysis did not account for the rebalancing frequency and rolling/expanding of the data samples.

3.1.1. MSCI Non-Listed Office Real Estate Index Series

The MSCI non-listed office real estate index series is a valuation-based total return index that measures valuation-based net asset value (NAV) on the underlying assets of individual non-listed funds that constitute the index. This causes MSCI valuation-based non-listed office real estate indices to have structures that are valuation-smoothed and lagged, resulting from discrepancies between appraised/estimated values and actual transaction prices.

Table 3.

Data description.

Table 3.

Data description.

| Market | Asset | Data Series |

|---|---|---|

| US | Non-listed office real estate | MSCI/PREA US All Funds—Open-end (AFOE) total return index |

| Stocks | MSCI US total return index | |

| Bonds | US Benchmark 10-year government bond yield total return index | |

| Cash | 3-month interbank rate total return index | |

| UK | Non-listed office real estate | MSCI Global PFI UK Funds Property total return index |

| Stocks | MSCI UK total return index | |

| Bonds | UK Benchmark 10-year government bond yield total return index | |

| Cash | 3-month interbank rate total return index | |

| Germany | Non-listed office real estate | MSCI Germany SFIX Property Fund total return index |

| Stocks | MSCI Germany total return index | |

| Bonds | Germany Benchmark 10-year government bond yield total return index | |

| Cash | 3-month interbank rate index | |

| Canada | Non-listed office real estate | MSCI/REALPAC Canada PFI Funds Property total return index |

| Stocks | MSCI Canada total return index | |

| Bonds | Canada Benchmark 10-year government bond yield total return index | |

| Cash | 3-month interbank rate total return index | |

| Australia | Non-listed office real estate | PCA/MSCI Australia Core Wholesale Property total return index |

| Stocks | MSCI Australia total return index | |

| Bonds | Australia Benchmark 10-year government bond yield total return index | |

| Cash | 3-month interbank rate total return index |

Source: Authors’ compilation from [8] and Thomson Reuters DataStream. Note: For brevity, the data series codes were not reported; however, they are available upon request from the authors.

3.1.2. De-Smoothing Method

The statistical discrepancies between appraised/estimated values and actual transaction prices for the MSCI valuation-based indices can lead to unrealistically high return-risk relationships and diversification benefits. Particularly, smoothed real estate returns lead to the actual real estate risk being underestimated [53,54]. To address these statistical issues, in private real estate research, the de-smoothing method and parameter of α = 0.5 have been extensively used, as seen in studies such as [17,55], which incorporated valuation-derived non-listed real estate data series into their analyses. Based on the statistical de-smoothing filtering technique of [56], the de-smoothing parameter, α = 0.5, was assumed to represent a quarter lag in information transmission within non-listed real estate, seeking to balance the correction for lagged valuations with the risk of amplifying noise.

The selection of the de-smoothing parameter α = 0.5 is empirically validated by model diagnostics. The AIC results across the five markets indicated that an autoregressive lag of one quarter was preferred in most cases, thereby justifying the adoption of a one-lag adjustment. Accordingly, α = 0.5 was chosen to reflect this quarter-lag correction, which is also consistent with established practice in the literature. Furthermore, the de-smoothed series with α = 0.5 was validated using the Breusch–Godfrey LM test, which revealed no significant residual autocorrelation across the five markets. These results collectively support the robustness of using α = 0.5 as the de-smoothing parameter in this study.

Therefore, this research employed [56] statistical de-smoothing filtering technique to reconstitute non-listed real estate total return indices in a higher resolution format, with the deployment of a de-smoothing parameter of α = 0.5. This calibration procedure resulted in one-quarter of the total return data being consumed in the construction of the de-smoothed non-listed office real estate total return series across all five markets, spanning from June 2008 to June 2024, which constitutes the 16-year analysis timeframe. However, the de-smoothing procedure was not applied to stocks, bonds, and cash across all five markets, as they are transaction-based index series.

3.2. Monetary Policy Rates

Table 4 summarizes the interest rate cycles for the US, UK, Eurozone, Canada, and Australia, based on policy rates from the Federal Reserve, Bank of England (BOE), European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Canada (BOC), and Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), respectively.

Table 4.

Interest rate cycles: the US, UK, Eurozone, Canada, and Australia.

To identify the turning points in each country’s interest rate cycle, this study uses the Bry–Boschan algorithm developed by [57], which detects the expansion (rate hike) and contraction (rate cut) phases. Rate hike cycles are defined as trough-to-peak (TP) periods, while rate cut cycles are defined as peak-to-trough (PT) periods.

The results show that the US, Canada, and Australia experienced relatively longer TP cycles, averaging 12.0, 11.0, and 13.3 quarters, respectively. In contrast, the UK and Eurozone had shorter expansion phases, averaging 7.0 and 6.7 quarters, respectively. For contraction phases (PTs), the US (18.7 quarters), UK (23.7), Eurozone (15.3), and Australia (17.3) had comparatively extended interest rate cut cycles. Canada, however, recorded a noticeably shorter contraction period, averaging just 7.4 quarters.

The US interest rate cut cycles occurred from June 2007 to September 2015, and from June 2019 to December 2021. In contrast, the US interest rate hike cycles occurred over December 2015–March 2019, and over March 2022–June 2024. Notably, these rate cut phases closely coincided with major global disruptions—namely, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (September 2007 to September 2009) and the COVID-19-induced recession (around April 2020)—indicating the US Federal Reserve’s reactive policy stance during the times of structural and cyclical economic stress.

The timing of interest rate turning points in the UK, Eurozone, Canada, and Australia largely mirrored those of the US, although these regions generally lagged behind. This suggests a degree of monetary policy transmission, where structural shifts in the US economy may have influenced policy responses in other advanced economies. As a result, central banks such as the BOE, ECB, BOC, and RBA may have adjusted their policy cycles in response to earlier shifts by the US Federal Reserve.

Overall, this study uses US interest rate turning points—identified through the Bry-Boschan dating algorithm by [57]—as a statistical foundation to define the expansion (rate hike) and contraction (rate cut) phases that frame the global interest rate phases.

3.3. Performance Analysis—Total Return Measurements

To assess performance for non-listed office real estate, other non-listed real estate subsectors (including retail, industrial, and residential), stocks, and bonds across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia, quarterly total returns are measured based on changes in the quarterly total return index of each asset across seven interest rate cycles. The method signals the performance of an asset over the measurement timeframe.

where,

- = the quarterly total returns percentage at time t;

- = the value of the total return index at time t.

3.4. Risk Analysis—Downside Risk

To evaluate portfolio allocation weights to non-listed office real estate in the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia across four distinct interest rate cycles, this study utilized a downside risk portfolio analysis. Unlike standard deviation—which accounts for both upward and downward volatility—downside risk specifically measures negative deviations from the mean, making it a more accurate indicator of risk in most investment contexts [58,59]. This is especially relevant in periods of heightened uncertainty, such as during interest rate tightening phases, when downside volatility poses a greater threat to investment performance [24,38,60].

where,

- = the downside deviation of asset i;.

- = the annual returns percentage of asset i at time t;

- = the average annual returns percentage of asset i;

- = the number of samples in which is below .

3.5. Risk-Adjusted Return Analysis—Sortino Ratios

The correlation coefficient analysis was employed to statistically assess the relationship between the annual returns of non-listed office real estate, mainstream asset classes, and other non-listed real estate subsectors, to evaluate the effectiveness of portfolio diversifications. The correlation analysis results are shown in an inter-asset correlation matrix format for ease of comparison.

where,

- = the Sortino ratio of asset i;

- = the average annual returns percentage of asset i;

- = the average annual returns percentage of the risk-free rate;

- = the downside deviation percentage of asset i.

3.6. Portfolio Diversification Analysis—Downside Correlation Coefficient

The analysis of downside risk was extended to explore the role of non-listed office real estate within broader multi-asset portfolio strategies across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia. This involved constructing diversified portfolios using a mean–downside risk optimization framework, based on index-level quarterly return data over multiple interest rate cycle periods. The methodological approach aligns with prior research on portfolio allocation involving both composite real estate assets (e.g., [61,62]) and sector-specific listed real estate investments (e.g., [20,24,38]), offering a consistent basis for assessing asset performance and allocation decisions across different market contexts. For each sub-period within the interest rate cycles, this study separately calculated the annualized average returns, downside risk measures, and Sortino ratios (risk-adjusted returns) for non-listed office real estate, conventional asset classes, and other non-listed real estate sectors across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia.

where,

- r = the value of the downside correlation coefficient between asset i and asset j;

- and = quarterly total returns of assets i and j at time t;

- and = average quarterly total returns of assets i and j;

- and = quarterly downside deviation of assets i and j.

3.7. Portfolio Allocation Analysis—Downside Risk Portfolio Allocation

Given that the study period covers the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine war, which have both contributed to unusually high volatility in financial and real estate markets, these events are a key reason for the use of downside-risk optimization, which allows this study to capture the adverse impacts of extreme market movements more effectively than traditional mean-variance approaches. The traditional mean-variance framework has several limitations in such volatile environments. It treats upside and downside volatility symmetrically, underestimates downside risk, and may not fully reflect the effects of tail events or non-normal return distributions [63,64]. By contrast, downside-risk optimization focuses on the potential losses and provides a more realistic assessment of risk for portfolio allocations under extreme market conditions, making it a more accurate indicator of risk in most investment contexts [58,59,65].

Two mean-downside risk portfolio allocation analyses were performed: (1) The domestic multi-asset portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate and other non-listed real estate subsectors (Scenario 1) were each capped at 10% in each of the five markets. This aligns more closely with the actual real estate allocations of approximately 10%, reflecting actual implementation by large-scale global institutional investors, according to the ANREV 2024 industry survey [3,9,14]. The analysis aims to assess the added-value role of non-listed office real estate in a multi-asset portfolio comprising mainstream asset classes and other non-listed real estate subsectors across various investment contexts and interest rate cycles. (2) The optimized global non-listed office real estate portfolio (Scenario 2) analysis was designed to reflect actual investment scenarios of global institutional investors implementing tactical rebalancing real estate asset allocation strategies from the perspective of geographically diversifying real estate portfolios across various investment jurisdictions and interest rate cycles, with the use of quarterly total returns in US dollars. The portfolio allocations to non-listed office real estate across the portfolio risk-return scale were estimated and reported in diagrams of asset allocations. Within both multi-asset and global non-listed office real estate portfolios, short sales for stocks and bonds are prohibited.

where,

- = expected average annual total returns of multi-asset portfolio p;

- = quarterly total returns of asset i;

- = weight of asset i;

- N = number of assets.

- = expected portfolio risk (downside deviation);

- and = weight of assets i and j in the multi-asset portfolio (, );

- = downside correlation coefficient between assets i and j;

- and = downside deviations of assets i and j.

4. Investment Performance Analysis

4.1. Interest Rate Cut Cycles

Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 (Panel A) present average annual returns, annual downside risk and Sortino ratios of non-listed office real estate and other non-listed real estate subsectors (retail, industrial and residential) and asset classes (stocks and bonds) across the US, UK, Germany, Canada and Australia over two interest rate cut cycles: June (Jun) 2008–September (Sep) 2015 and Jun 2019–December (Dec) 2021.

4.1.1. Performance Analysis

In the two interest rate cut cycles, non-listed office real estate consistently outperformed in terms of average annual returns relative to bonds and non-listed retail real estate, but had lower average annual returns than stocks and non-listed industrial and residential real estate in each of the five markets. However, the exceptions are Canada (7.41%) and Australian non-listed office real estate (6.54%), delivering stronger average annual returns than stocks (Canada 2.77%, Australia 4.03%) and bonds (Canada 3.03%, Australia 4.31%) over Jun-2008 and Sep 2015. In addition, the UK non-listed office real estate (6.66%, 4.37%) outperformed stocks (4.52%, 3.72%) and bonds (2.82%, 0.60%) in terms of average annual returns over the two interest rate cut cycles.

4.1.2. Risk Analysis–Downside Risk

In terms of annual downside risk, non-listed office real estate was lower than stocks but was higher than bonds in each of the five jurisdictions over the two interest rate cut cycles. Compared with other non-listed real estate subsectors, the non-listed office sector generally registered higher annual downside risk across the US, UK, Canada, and Australia over June 2008–September 2015. In contrast, non-listed office real estate generally posted lower annual downside risk than other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the five markets from June 2019 to December 2021.

4.1.3. Risk-Adjusted Return Analysis—Sortino Ratios

On a risk-adjusted performance basis, measured by Sortino ratios, non-listed office real estate (Germany: 1.95, Australia: 0.55) outperformed stocks (0.28, 0.01) and bonds (1.14, 0.25) in Germany and Australia from June 2008 to September 2015. Meanwhile, non-listed office real estate (the UK 0.67, Canada 1.09) outperformed stocks (0.33, 0.15) but underperformed bonds (1.68, 2.23) in the UK and Canada. In the US, non-listed office real estate (0.48) underperformed stocks (0.53) and bonds (2.65). Between June 2019 and December 2021, non-listed office real estate outperformed stocks and bonds across the US, UK, Germany, and Australia, primarily due to their lower annual downside risk levels. The only exceptions are non-listed office real estate in Canada (0.75), underperforming stocks (0.86), and bonds (1.66).

In the two interest rate cut cycles, non-listed office real estate generally underperformed other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US, UK, Canada, and Australia when evaluated on a risk-adjusted basis, attributed to the comparatively low average annual returns and high annual downside risk for non-listed office real estate in each of the four markets. Nonetheless, German (4.76) and Australian non-listed office real estate (2.80) generally outperformed other non-listed real estate subsectors from June 2019 to December 2021. The other exception was Canada non-listed office real estate (1.09), which outperformed other non-listed real estate subsectors from June 2008 to September 2015, except for Canada non-listed residential real estate (1.60).

4.2. Interest Rate Hike Cycles

Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 (Panel B) depict average yearly returns and downside risk measured annually and Sortino ratios of non-listed office real estate and other non-listed real estate subsectors (retail, industrial and residential) and asset classes (stocks and bonds) across the US, UK, Germany, Canada and Australia over two interest rate cut cycles: December 2015–March (Mar) 2019 and March 2022–June 2024.

4.2.1. Performance Analysis

Between December 2015 and March 2019, non-listed office real estate outperformed bonds in terms of average annual returns; however, it generally had lower average annual returns than stocks and other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US, UK, Germany, and Canada. However, Australian non-listed office real estate offered (12.01%) the strongest average annual returns among all asset classes. Meanwhile, German non-listed office real estate (6.97%) provided greater average annual returns as opposed to bonds (0.28%) and stocks (5.19%). Following the COVID-19 stimulus package from March 2022 to June 2024, non-listed office real estate had the lowest average annual returns among asset classes in each of the five investment contexts.

4.2.2. Risk Analysis—Downside Risk

In terms of annual downside risk, non-listed office real estate offered higher volatility than bonds but generally lower volatility than stocks and other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the five markets over December 2015–March 2019. Notably, the US non-listed office real estate (0.46%) exhibited the lowest volatility among asset classes. Conversely, the UK non-listed office real estate (4.94%) had higher volatility than other non-listed real estate subsectors. Over March 2022–June 2024, non-listed office real estate posted lower volatility than stocks but generally higher volatility than bonds and other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the five markets. The only exception was the UK non-listed office real estate (12.05%), with higher volatility than stocks (5.20%) and bonds (1.56%).

4.2.3. Risk-Adjusted Return Analysis—Sortino Ratios

In terms of risk-adjusted performance estimated by Sortino ratios, over December 2015–March 2019, non-listed office real estate generally outperformed stocks, bonds, and other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US, Germany, and Australia. These were due to their superior average annual returns, coupled with decreased annual downside risk compared to other asset classes. In contrast, the UK non-listed office real estate (1.02) generally underperformed asset classes, except for non-listed retail real estate (0.48). Meanwhile, Canada’s non-listed office real estate (4.37) outperformed stocks (0.92), non-listed retail real estate (2.36), and bonds (2.75), but underperformed non-listed industrial real estate (5.90) and residential real estate (5.09). After the COVID recession stimulus package from March 2022 to June 2024, non-listed office real estate was the worst asset in each of the five cases, caused by their lowest average annual returns in each of the five markets.

In short, non-listed office real estate generally posted superior risk-adjusted returns than stocks, bonds, and other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US, Germany, Canada, and Australia over the interest rate hike cycle before the COVID recession, driven by their high average annual returns and lower annual downside risk. The momentum of risk-adjusted returns for non-listed office real estate continued into the interest rate cut cycle after the COVID recession from June 2019 to December 2021, where non-listed office real estate generally had greater risk-adjusted returns than stocks, bonds, and non-listed retail real estate in each of the five cases. Particularly, Australian non-listed office real estate delivered the strongest performance based on risk-adjusted returns among all asset classes. This may be attributed to the Federal funds rate reaching its lowest quarterly level of 0.75% in the last 25 years [66].

However, non-listed office real estate posted inferior risk-adjusted returns compared to different asset classes across the five markets during the period of rising interest rates after the COVID recession. The inferior risk-adjusted performance of non-listed office real estate may be attributed to the fact that hybrid working strategies have significantly increased office vacancy rates since the COVID pandemic. Hybrid working trends have resulted in structural changes in the global office space [67,68]. As of March 2025, the office vacancy rate was recorded at 15% in the Asia-Pacific region, 9% in Europe, 22% in North America, and 22% globally, the highest level after the GFC [69]. Likewise, over the interest rate cut cycles preceding the COVID recession, non-listed office real estate generally registered higher risk-adjusted returns compared to stocks and non-listed retail real estate, but less risk-adjusted returns compared to bonds and other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the five markets. More importantly, the differential total returns of non-listed office real estate across various interest rate cycles were significantly validated in each of the five markets, highlighting the distinct investment characteristics of non-listed office real estate affected by various interest rate cycles across the five markets.

Table 5.

Global non-listed office real estate average annual returns across interest rate cycles.

Table 5.

Global non-listed office real estate average annual returns across interest rate cycles.

| US | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 7.49% | 2.66% | 4.44% | 6.36% | 6.53% | 6.33% |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 23.35% | 1.34% | 4.02% | −2.01% | 25.26% | 10.45% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 13.98% | 2.34% | 6.83% | 5.27% | 12.31% | 5.57% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 6.70% | 3.72% | −14.28% | 1.13% | −0.73% | −3.40% |

| UK | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 4.52% | 2.82% | 6.66% | 3.61% | 7.22% | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 3.72% | 0.60% | 4.37% | 4.33% | 22.97% | 8.43% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015-March 2019 | 9.57% | 1.26% | 5.48% | 2.28% | 12.87% | 7.10% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 9.13% | 3.55% | −10.29% | −5.87% | −11.05% | 1.89% |

| Germany | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 5.06% | 2.14% | 3.04% | |||

| June 2019-December 2021 | 11.09% | −0.36% | 8.21% | 2.77% | 11.49% | 11.66% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 5.19% | 0.28% | 6.97% | 5.89% | 9.19% | 9.67% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 3.75% | 2.09% | −1.05% | 2.42% | 2.77% | |

| Canada | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 2.77% | 3.03% | 7.41% | 6.54% | 6.07% | 8.21% |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 13.49% | 1.51% | 3.07% | 0.54% | 22.48% | 7.15% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 8.74% | 2.05% | 5.34% | 5.69% | 9.79% | 9.30% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 5.07% | 3.19% | −5.34% | 0.83% | 4.41% | 4.14% |

| Australia | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 4.03% | 4.31% | 6.54% | 7.34% | 7.73% | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 9.64% | 1.22% | 8.48% | −2.48% | 22.81% | |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 10.85% | 2.54% | 12.01% | 7.67% | 10.46% | |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 8.14% | 3.69% | −7.27% | 0.83% | −1.35% | |

Source: Authors’ compilation/analysis. Note: Local currency.

Table 6.

Global non-listed office real estate annual downside risk across interest rate cycles.

Table 6.

Global non-listed office real estate annual downside risk across interest rate cycles.

| US | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 13.89% | 0.94% | 8.86% | 7.10% | 7.48% | 8.20% |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 16.34% | 0.77% | 2.12% | 5.10% | 5.64% | 3.81% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 9.78% | 0.70% | 0.46% | 0.97% | 0.60% | 0.70% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 14.11% | 1.07% | 5.58% | 2.98% | 5.99% | 6.11% |

| UK | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 11.07% | 1.19% | 8.75% | 8.92% | 1.19% | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 16.10% | 0.48% | 2.49% | 5.06% | 6.91% | 2.27% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 8.77% | 0.39% | 4.94% | 3.87% | 4.09% | 2.72% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 5.20% | 1.56% | 12.05% | 13.55% | 22.87% | 6.58% |

| Germany | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 16.48% | 1.48% | 1.33% | |||

| June 2019–December 2021 | 17.98% | 0.23% | 1.86% | 1.14% | 6.45% | 1.63% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 10.70% | 0.38% | 1.42% | 1.21% | 2.43% | 2.33% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 13.42% | 1.13% | 3.32% | 1.21% | 1.39% | |

| Canada | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 13.22% | 0.98% | 6.00% | 5.41% | 6.66% | 4.60% |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 15.03% | 0.56% | 3.32% | 8.41% | 6.20% | 1.82% |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 8.50% | 0.41% | 1.01% | 2.02% | 1.50% | 1.65% |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 9.89% | 0.53% | 3.52% | 3.38% | 4.75% | 0.49% |

| Australia | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 11.64% | 1.48% | 4.75% | 2.66% | 3.47% | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 16.46% | 0.40% | 2.87% | 9.30% | 8.15% | |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 8.12% | 0.42% | 1.77% | 1.42% | 2.71% | |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 8.82% | 1.05% | 5.42% | 3.23% | 5.83% | |

Source: Authors’ compilation/analysis. Note: Local currency.

Table 7.

Global non-listed office real estate Sortino ratios across interest rate cycles.

Table 7.

Global non-listed office real estate Sortino ratios across interest rate cycles.

| US | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 0.53 | 2.65 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 1.40 | 1.02 | 1.64 | −0.50 | 4.38 | 2.60 |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 1.31 | 1.70 | 12.27 | 4.22 | 18.70 | 6.30 |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 0.18 | −0.38 | −3.30 | −1.01 | −0.81 | −1.23 |

| UK | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 0.33 | 1.68 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 5.39 | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 1.65 | 0.80 | 3.28 | 3.60 |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 1.04 | 2.10 | 1.02 | 0.48 | 3.04 | 2.45 |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 1.02 | −0.19 | −1.17 | −0.72 | −0.65 | −0.30 |

| Germany | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 0.28 | 1.14 | 1.95 | |||

| June 2019–December 2021 | 0.65 | 1.24 | 4.76 | 3.01 | 1.88 | 7.53 |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 0.55 | 2.64 | 5.39 | 5.44 | 4.07 | 4.47 |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 0.12 | −0.09 | −0.98 | 0.19 | 0.41 | |

| Canada | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 0.15 | 2.23 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.79 | 1.60 |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 0.86 | 1.66 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 3.53 | 3.61 |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 0.92 | 2.75 | 4.37 | 2.36 | 5.90 | 5.09 |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 0.12 | −1.36 | −2.63 | −0.91 | 0.10 | 0.47 |

| Australia | Stocks | Bonds | Office | Retail | Industrial | Residential |

| Panel A: Interest rate cut cycles | ||||||

| June 2008–September 2015 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 1.28 | 1.09 | |

| June 2019–December 2021 | 0.56 | 1.98 | 2.80 | −0.31 | 2.75 | |

| Panel B: Interest rate hike cycles | ||||||

| December 2015–March 2019 | 1.07 | 0.81 | 5.53 | 3.85 | 3.05 | |

| March 2022–June 2024 | 0.51 | 0.07 | −2.01 | −0.86 | −0.85 | |

Source: Authors’ compilation/analysis. Note: Local currency.

5. Portfolio Diversification Analysis

5.1. Interest Rate Cut Cycles

Appendix A Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5 (Panel A) present the downside correlation analysis results for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over the two interest rate cut cycles: June 2008–September 2015 and June 2019–December 2021. Across the two interest rate cut cycles, non-listed office real estate generally provided institutional investors with significantly stronger portfolio diversification benefits with stocks compared with other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US (average r = 0.05), UK (r = 0.35), Germany (r = 0.06), Canada (r = −0.02), and Australia (r = 0.16). These findings suggest that non-listed office real estate offered institutional investors notable effectiveness in diversifying multi-asset portfolios across various jurisdictions during the interest rate cut cycles. Meanwhile, non-listed office real estate generally offered institutional investors great portfolio diversification benefits alongside bonds across the US (average r = 0.29), UK (r = 0.28), Germany (r = 0.23), Canada (r = 0.16), and Australia (r = 0.17). The US (r = 0.62) and UK non-listed office real estate (r = 0.73) were the exceptions, with significantly high correlations with bonds in each of the two cases from June 2019 to December 2021.

In the context of an inter-real estate investment strategy, non-listed office real estate generally delivered significantly less portfolio diversification benefits compared to other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US (average r = 0.80), the UK (r = 0.77), Canada (r = 0.72), and Australia (r = 0.72) over the two interest rate cut cycles.

5.2. Interest Rate Hike Cycles

In Appendix A, Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5 (Panel B) present the results of the correlation analysis for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over the two interest rate hike cycles: December 2015–March 2019 and March 2022–June 2024. Across the two interest rate hike cycles, non-listed office real estate generally provided institutional investors with stronger portfolio diversification benefits than stocks in other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US (average r = −0.50), UK (r = −0.20), Germany (r = −0.48), and Australia (r = −0.02). Particularly, significantly negative correlations with stocks were observed for the US non-listed office real estate (r = −0.72) over March 2022–June 2024 and German non-listed office real estate (r = −0.70) over December 2015–March 2019. These imply that non-listed office real estate provided high portfolio diversification effectiveness in each of the fixed-income investment contexts over the interest rate hike cycles. In contrast, non-listed office real estate generally offered lesser portfolio diversification benefits with bond compared with other non-listed real estate subsectors across the US (average r = 0.01), UK (r = 0.09), Germany (r = −0.05), and Australia (r = −0.08).

In summary, non-listed office real estate delivered compelling portfolio diversification benefits alongside stocks and bonds across the US, UK, Germany, and Australia over interest rate hike cycles than interest rate cut cycles. These are aligned with the listed real estate results of [23], where the US, UK, and European sector-specific listed real estate had stronger portfolio diversification benefits in interest rate hike cycles than interest rate cut cycles. The only exception was Canada’s non-listed office real estate, which showed stronger portfolio diversification benefits with stocks over interest rate cut cycles than interest rate hike cycles. In the context of inter-real estate investment strategies, diversification benefits between non-listed office real estate and other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the five markets were more effective over interest rate hike cycles than interest rate cut cycles.

6. Downside Risk Portfolio Analysis

6.1. Global Multi-Asset Portfolios

The convincing risk-adjusted performance characteristics observed in non-listed office real estate indicate the possibility of a strategic deployment within institutional investors’ multi-asset portfolios across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia (in local currency). To assess this hypothesis and address RQ2, a constrained asset allocation analysis (Scenario 1) was conducted, in which allocation to each non-listed real estate subsector was capped at 10%. Scenario 1 reflects the actual real estate allocations of institutional investors, typically accounting for 10% of their multi-asset portfolios [9].

6.1.1. Interest Rate Cut Cycles

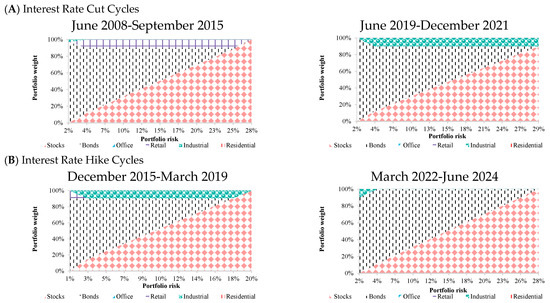

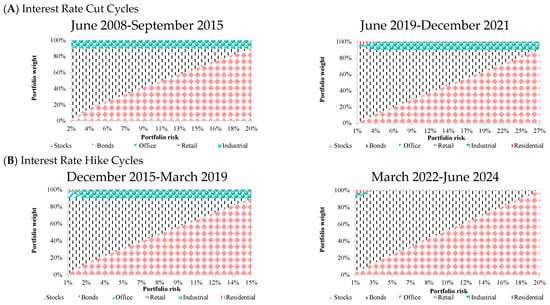

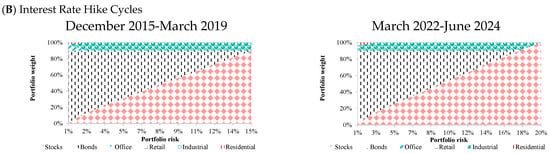

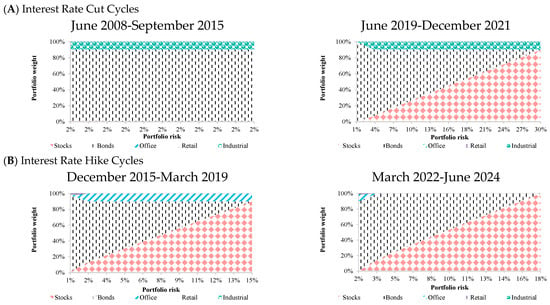

Figure 1A, Figure 2A, Figure 3A, Figure 4A and Figure 5A illustrate the results of the constrained portfolio analysis for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over the two interest rate cut cycles: June 2008–September 2015 and June 2019–December 2021. Non-listed office real estate found no role across the full portfolio risk-return range in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia over the two interest rate cut cycles. This may be attributed to the inferior risk-adjusted returns of non-listed office real estate compared to bonds and other non-listed real estate subsectors in each of the four markets during interest rate cut cycles. However, non-listed office real estate generally posted stronger risk-adjusted returns than stocks and non-listed retail real estate. However, German non-listed office real estate (an allocation of 9.0%) strongly dominated the capped 10% of total real estate allocations across the portfolio’s risk-return scale from June 2008 to September 2015. This shift can be attributed to German non-listed office real estate providing the strongest risk-adjusted returns among asset classes (Sortino ratio = 1.95) and attractive diversification effectiveness alongside bonds (r = 0.04) and stocks (r = 0.32).

6.1.2. Interest Rate Hike Cycles

Figure 1B, Figure 2B, Figure 3B, Figure 4B and Figure 5B present the results of the constrained portfolio analysis for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over two interest rate hike cycles: December 2015–March 2019 and March 2022–June 2024. Compared to the previous interest rate cut cycles, the incremental average allocations to non-listed office real estate within the lower segment of the portfolio risk-return range were observed across the UK (average allocation increased to 0.7% over December 2015–March 2019 from 0.1% over June 2008–September 2015), Canada (0.7% from 0.0%) and Australia (9.1% from 0.0%) over December 2015–March 2019, reflecting superior risk-adjusted performance of non-listed office real estate relative to stocks, bonds and other non-listed real estate subsectors in Canada and Australia over the interest rate hike cycle before the COVID recession. Particularly, the UK non-listed office real estate had the best diversification effectiveness (r = −0.12) with stocks amongst non-listed real estate subsectors, resulting in its role in the multi-asset portfolio in the UK during this period. This suggests the co-existence potential of non-listed office real estate with the overall stock market in each of the three markets due to their portfolio diversification efficiency.

After the COVID-19 recession stimulus package (March 2022–June 2024), Australian non-listed office real estate (with an average allocation of 0.8%) was within the lower segment of the portfolio risk–return scale. In contrast, other non-listed real estate subsectors had no allocation during this period. This may be attributed to Australian non-listed office real estate exhibiting compelling diversification effectiveness alongside stocks (r = −0.24) and bonds (r = −0.42) during this period. This also aligns with [23], who highlighted that Australian listed office real estate was largely unaffected by 3-month interest rates and 10-year government bond yields. Nonetheless, non-listed office real estate had non-existent allocations across the US, UK, Germany, and Canada, aligning with the prices and asset values of global office markets were severely affected by the pandemic as a result of structural and cyclical shifts, including hybrid working practices since the COVID-19 pandemic [67,68] and the accelerated global interest rate hike cycle since March 2022 [8]. Particularly, [67] reports that office real estate prices were empirically estimated to decline due to the hybrid work trends in the post-COVID context. Additionally, this aligns with the empirical results of [24], which show that the US, UK, and European office real estate sectors are acting negatively in response to the rising possibility of economic recession risk forecasted by yield curve inversions. The yield curve inversion occurred across the US, UK, and Germany after the respective central banks deployed the COVID-19 recession stimulus package (March 2022–June 2024) [70].

Figure 1.

US multi-asset portfolio asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: Local currency; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

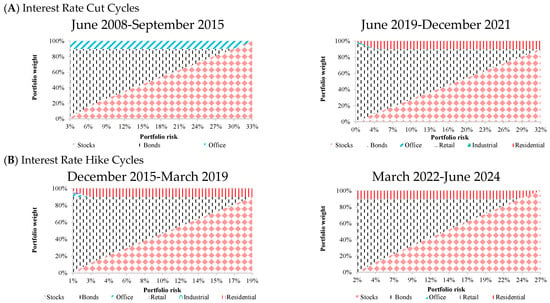

6.2. Global Non-Listed Office Real Estate Portfolios

To assess this hypothesis and address RQ3, the aim of scenario 2 is to provide institutional real estate investors with tactically rebalanced portfolio allocation strategies for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia (in US dollars) over various interest rate cycles.

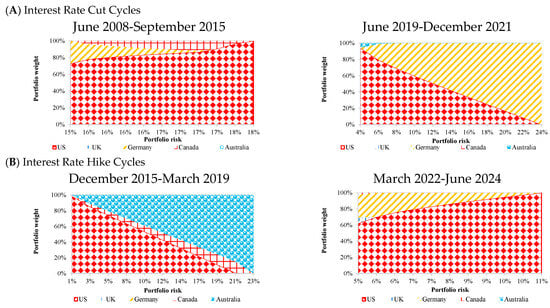

6.2.1. Interest Rate Cut Cycles

Figure 6A shows the results of the optimized global non-listed office real estate portfolio analysis for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over the two interest rate cut cycles: June 2008–September 2015 and June 2019–December 2021. The US non-listed office real estate played a dominant role (average allocation = 64.5%) within the range of portfolio risk and return across both interest rate reduction periods, followed by Germany (32.0%), Canada (3.2%), and Australia (0.3%). Specifically, the US non-listed office real estate took up a significant proportion (85.5%) of the optimized global non-listed office real estate portfolio over June 2008–September 2015, with the footprints of Germany (8.1%) and Canada (6.4%). Nevertheless, the German non-listed office real estate constitutes a significant portion (55.8%) of the downside-risk optimized portfolio over June 2019–December 2021, especially in the higher segment of the portfolio risk-return scale. Meanwhile, the US non-listed office real estate (43.6%) was situated in the lower segment of the portfolio risk-return range, co-existing with Australia (0.6%).

6.2.2. Interest Rate Hike Cycles

Figure 6B depicts the results of the optimized global non-listed office real estate portfolio analysis for non-listed office real estate across the US, UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia over two interest rate hike cycles: December 2015–March 2019 and March 2022–June 2024. Compared to interest rate cut cycles, Australian non-listed office real estate (average allocation increased to 24.2% in interest rate hike cycles from 0.3% in interest rate cut cycles) played a more significant role in optimizing global non-listed office real estate portfolios over two interest rate cycles. Meanwhile, the US non-listed office real estate sector featured the largest proportion (64.3%) of the optimized portfolio. In comparison, Canada’s non-listed office real estate sector had a limited portion (3.8%) of the portfolio allocations. In contrast, German office real estate’s portion in the optimized portfolio decreased (average allocation dropped to 7.3% in interest rate hike cycles from 32.0% in interest rate cut cycles).

Figure 2.

UK multi-asset portfolio asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: Local currency; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

Figure 3.

German multi-asset portfolio asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: Local currency; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

Specifically, Australian non-listed office real estate (average allocation = 48.4%) had significant allocations in the higher segment of the portfolio risk-return range over December 2015–March 2019, while the US non-listed office real estate (44.2%) appeared in the lower segment of the portfolio risk-return scale, with a limited portion of Canadian non-listed office real estate (7.4%). However, the US non-listed office real estate dominated allocation proportions (84.5%) within the entire portfolio risk-return range after the COVID recession stimulus package (March 2022–June 2024), with small roles of German (14.7%), the UK (0.7%) and Canada non-listed office real estate (0.2%) in the lower segment of the portfolio risk-return scale. These portfolio allocation patterns align with [23,24], who empirically found that the US office real estate was immune to domestic 3-month and 10-year government bond yields. However, global office real estate markets were significantly sensitive to the US 3-month and 10-year government bond yields. This is particularly notable as the speed of the Federal Reserve’s fund rate rise since March 2022 was the sharpest in the last 35 years, up by 500 bps in 14 months [71].

Figure 4.

Canada multi-asset portfolio asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: Local currency; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

Figure 5.

Australian multi-asset portfolio asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: Local currency; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

7. Robustness Checks

To validate the stability and reliability of the baseline findings, a series of robustness checks was conducted across multiple dimensions. These include sensitivity analyses of (1) the de-smoothing parameters applied to non-listed real estate returns, (2) alternative specifications of the minimum acceptable return (MAR), (3) different portfolio allocation constraints for non-listed real estate, (4) the incremental contribution of non-listed office real estate to benchmark stock–bond portfolios, (5) the impacts of COVID-19 as an alternative global phase intersection, and (6) country-specific interest rate turning points for major markets (UK, Eurozone, Canada, and Australia). The robustness check results were not reported, for brevity, but are available upon request from the authors.

7.1. De-Smoothing Parameters Sensitivity Analysis

Given that smoothed real estate returns can lead to an underestimation of actual real estate risk [53,54], the non-listed real estate returns in this study were de-smoothed using [56] de-smoothing approach with a parameter of 0.5. Nevertheless, the robustness of the baseline results should be further examined under alternative parameter specifications. To strengthen the robustness of the baseline results, this study incorporated sensitivity analyses by using alternative de-smoothing parameters, α = 0.2, α = 0.3, and α = 0.7. As echoed by [72], building on [73] and [74], in global private real estate markets, a one-year lag (equivalent to four quarters) implies a smoothing parameter of α, with an approximate value of 0.2. In addition, the sensitivity of the parameters is also assessed, using α = 0.3 and α = 0.7. These results are generally consistent with the baseline results, where non-listed office real estate played a more significant role in multi-asset portfolios across the five markets in interest rate hike cycles than in interest rate cut cycles. These imply the baseline results are robust to variations in the de-smoothing parameters.

7.2. Minimum Acceptable Return (MAR) Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the reliability of the baseline estimates, this study also deployed an alternative MAR value = 0 over the study sub-periods. The results are fairly robust and did not alter the conclusion. These indicate that the baseline results are robust to variations in the MAR values.

7.3. Non-Listed Real Estate Fixed at 10%

In addition to the real estate portfolio allocation capped at 10%, this study examined the alternative scenario of the real estate portfolio allocation fixed at 10%. The results are fairly in line with the baseline results. This implies the alternative real estate portfolio allocation scenario did not alter the conclusion of this study.

Figure 6.

Global non-listed office real estate asset allocation diagram across interest rate cycles. Note: The US dollars; The portfolio allocation summary table was not reported for brevity but is available upon request from the authors.

7.4. Addition of Non-Listed Office Real Estate to the Benchmark Portfolio

This study estimated a portfolio alpha for the addition of non-listed office real estate to the market benchmark portfolio, which consists of stocks and bonds only, reflecting the classical 60-40 portfolio allocation strategy for institutional investors. The results showed that the addition of non-listed office real estate significantly outperformed the market benchmark portfolios across the five markets in both interest rate cut and hike cycles. However, the addition of non-listed office real estate marked a slight difference from the market benchmark portfolio across the five jurisdictions in the interest rate hike cycle after the COVID recession stimulus package. These highlight the added value of non-listed office real estate in global multi-asset portfolios for institutional real estate investors.

7.5. Hybrid Working Trends and Alternative Global Intersection Phases—The Impacts of COVID

As echoed by [67,68], the hybrid working trend, as a structural change in the global office space, has been observed in the post-COVID context. This study measured the impacts of COVID as a structural change in the global office space, as well as the alternative global phase, which is the intersection/union of local phases. The analysis estimated model parameters on the pre-COVID period (from December 2012–December 2019), evaluated performance during COVID (from March 2020-December 2020), and post-COVID (from March 2021–June 2024). The pre-COVID period broadly aligned with the empirically selected interest rate hike cycle (from December 2015–March 2019), while the COVID period is broadly consistent with the empirically selected interest rate cut cycle (from June 2019–December 2021). Also, the post-COVID period is broadly in line with the empirically selected interest rate hike cycle (from March 2022–June 2024). The results broadly aligned with the main baseline results, where non-listed office real estate played a more significant role in the multi-asset portfolios in interest rate hike cycles than in interest rate cut cycles. In addition, this study examined the out-of-sample period—the recent interest rate cut cycle between September 2024 and December 2024. The results aligned with the baseline results of this study.

7.6. Country-Specific Interest Rate Turning Points in the UK, Europe, Canada, and Australia

To ensure that the results are not sensitive to the empirical choice of global interest rate cycle dating, this study performed robustness checks using country-specific interest rate turning points for the UK, the Eurozone, Canada, and Australia. In the UK, interest rate cycles include June 2008–September 2017 (interest rate cut), December 2017-December 2019 (interest rate hike), March 2020-September 2021 (interest rate cut), and December 2021-June 2024 (interest rate hike). In Germany, interest rate cycles include December 2012–June 2022 (interest rate cut), September 2022-June 2024 (interest rate hike). In Canada, interest rate cycles include June 2008-June 2017 (interest rate cut), September 2017-December 2019 (interest rate hike), March 2020-December 2021 (interest rate cut), and March 2022–June 2024 (interest rate hike). In Australia, interest rate cycles include June 2008-March 2022 (interest rate cut) and June 2022-June 2024 (interest rate hike). While these countries exhibit broadly similar patterns to the US, defining cycles based on local policy rates produces results consistent with our main baseline findings, where non-listed office real estate played a more significant role in the multi-asset portfolios across the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia in interest rate hike cycles than in interest rate cut cycles.

Collectively, these checks confirm that the main conclusions—particularly the role of non-listed office real estate as a more significant contributor to multi-asset portfolios during interest rate hike cycles—remain consistent across alternative assumptions and specifications.

8. Conclusions