Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes Based on the Analysis of Historical Events—A Case Study of Gubeikou, Beijing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

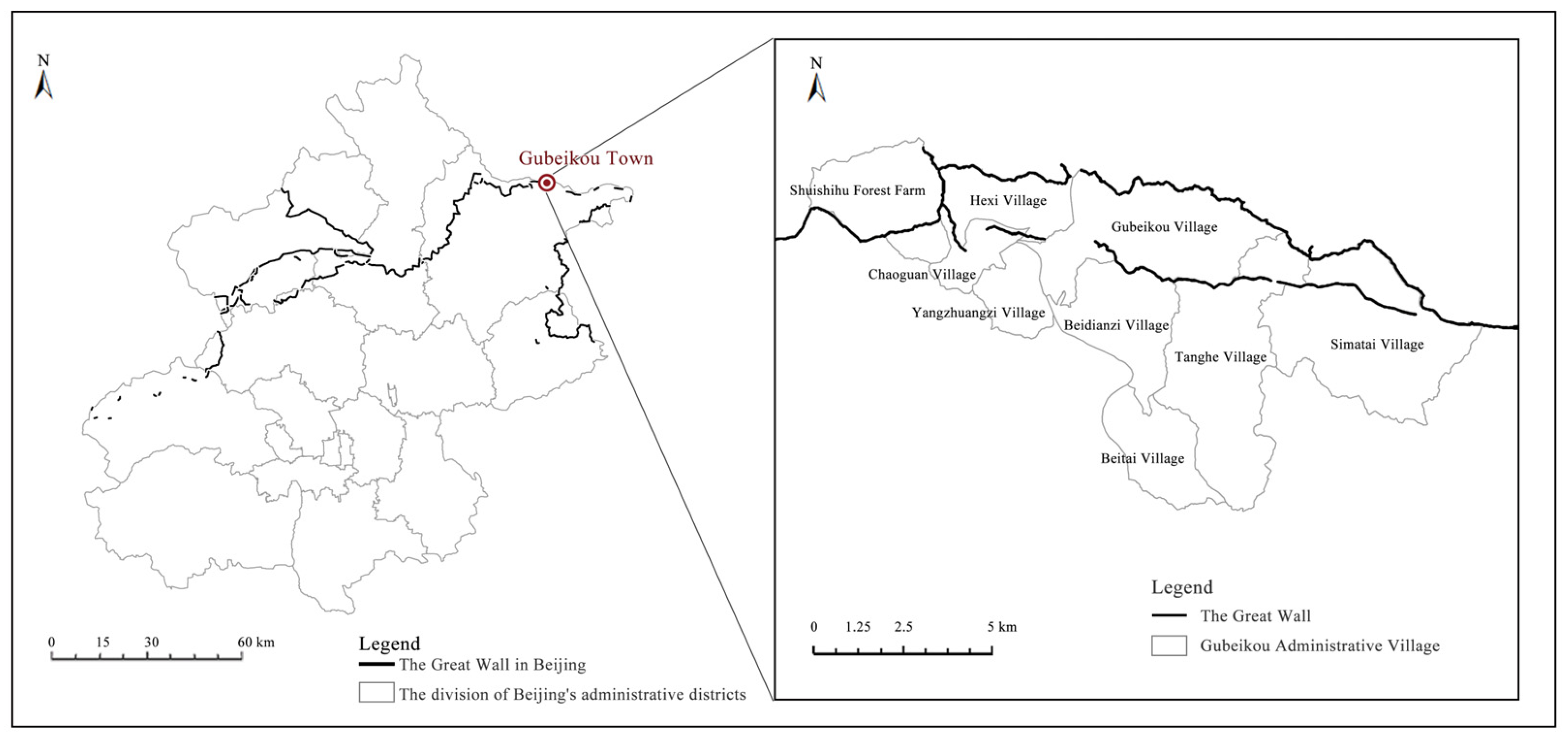

2.1. Research Scope

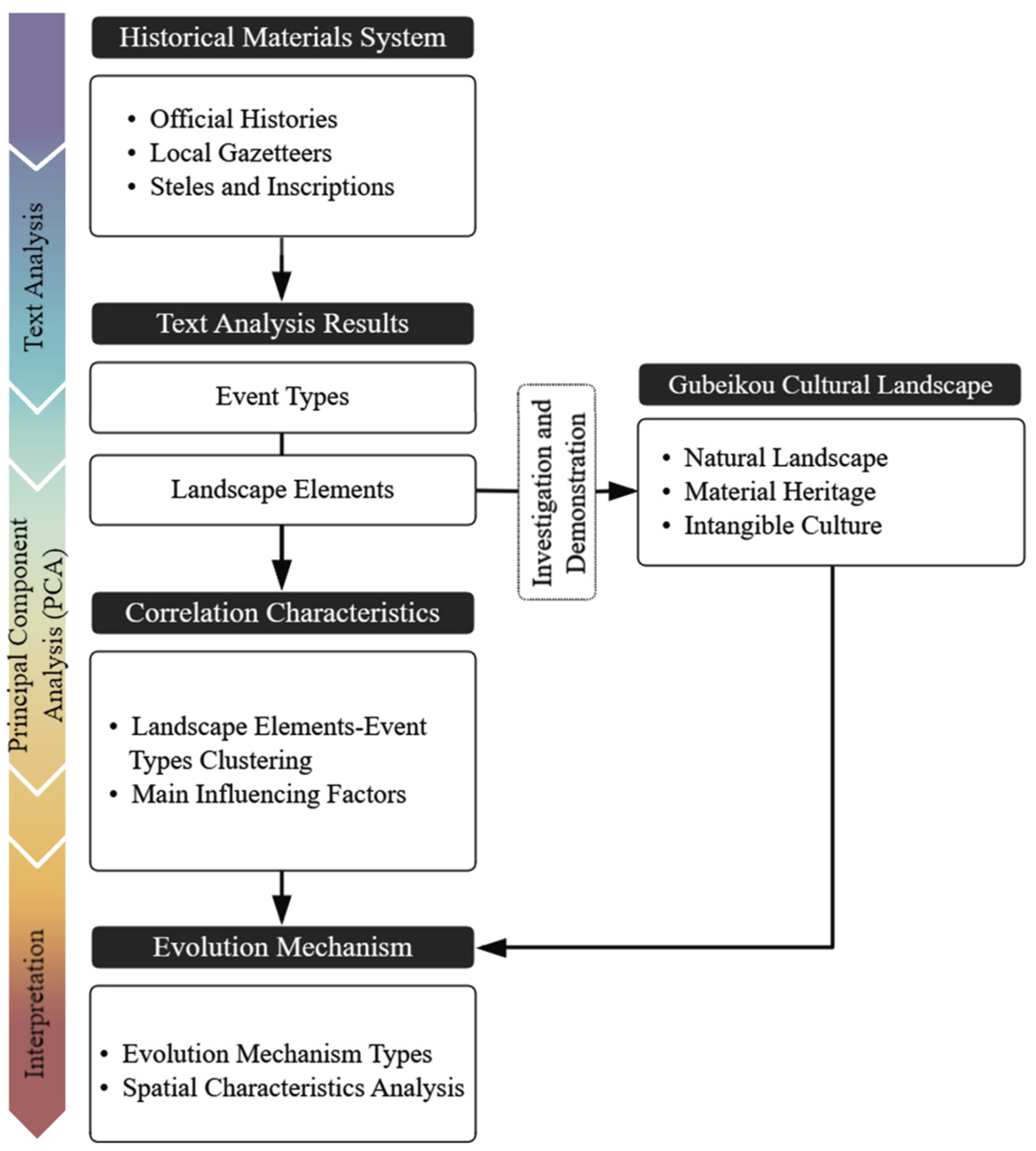

2.2. Research Methods

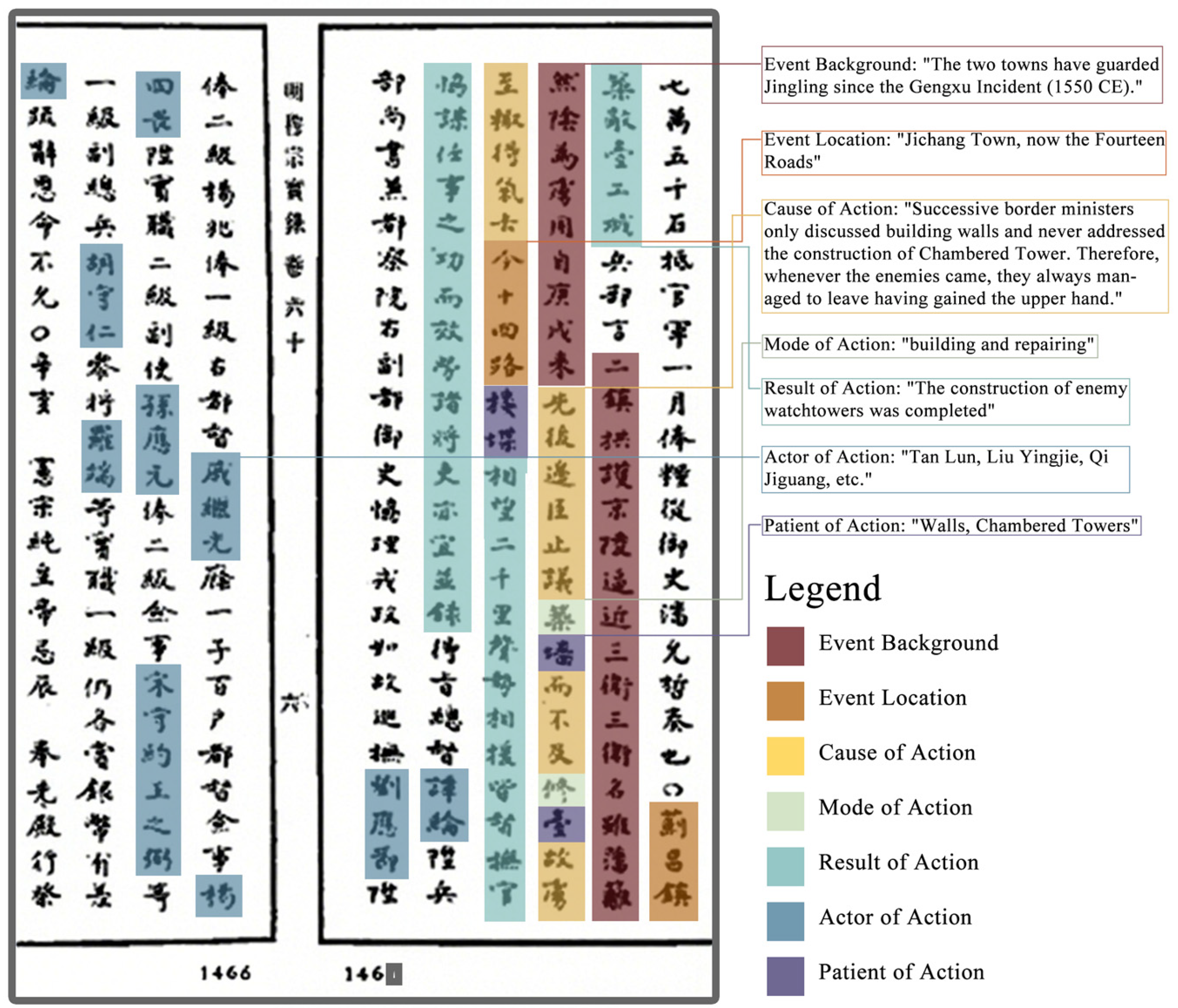

2.2.1. Text Analysis Method

2.2.2. Principal Component Analysis

2.2.3. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering

2.3. Data Processing for Text Analysis

2.4. Research Path

3. Results

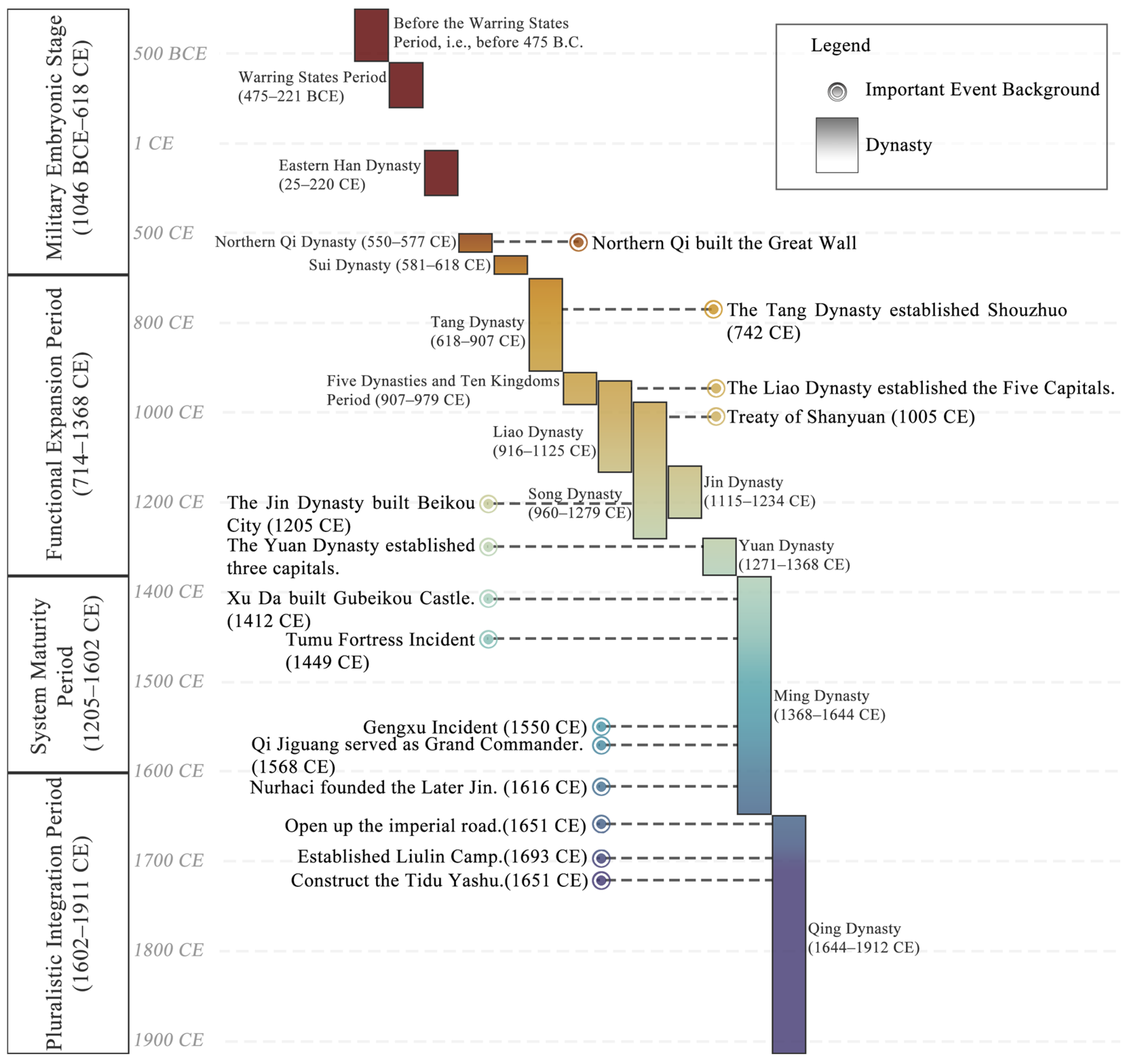

3.1. Study on the Historical Context of the Gubeikou Area and Influencing Factors in Periods

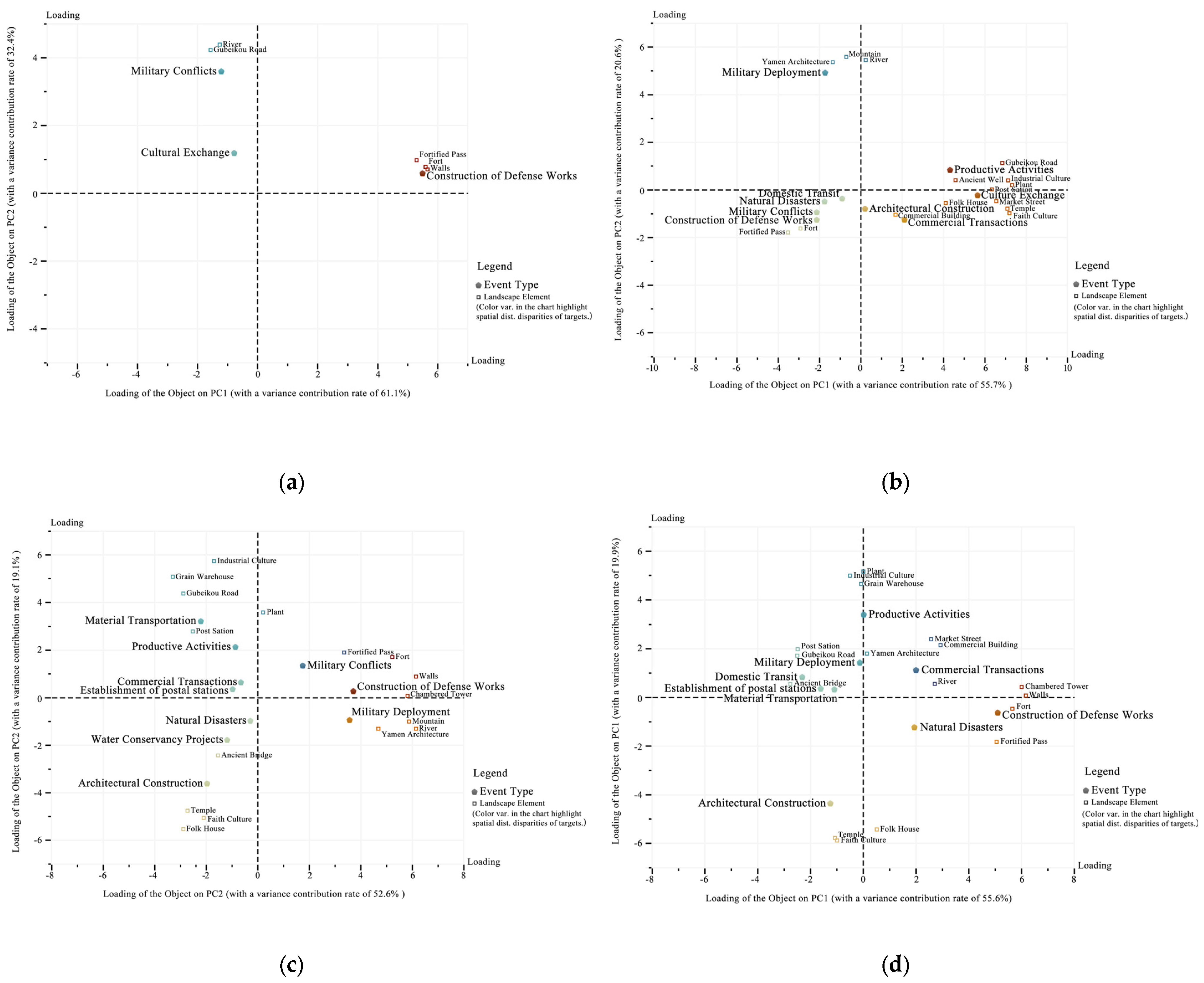

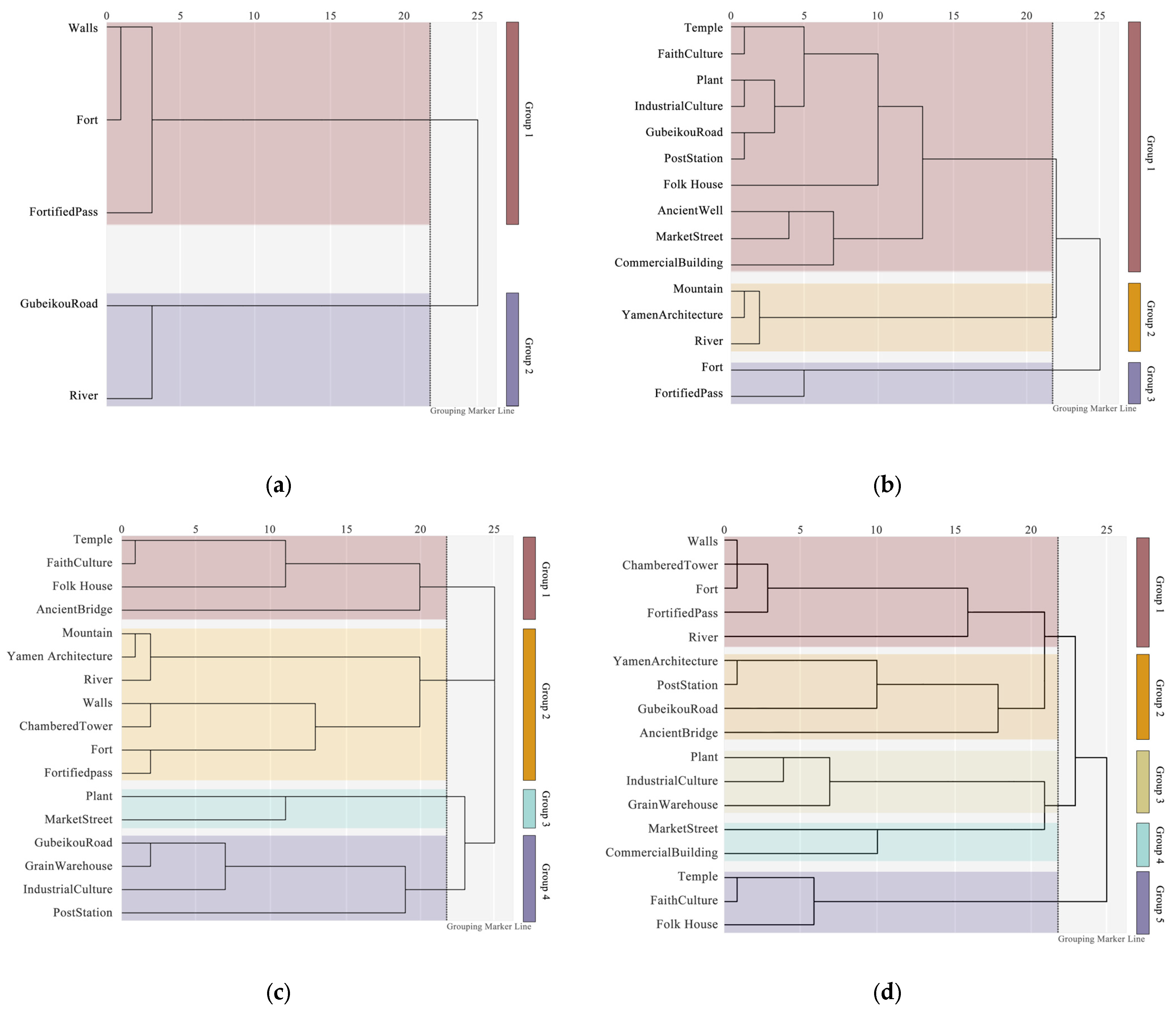

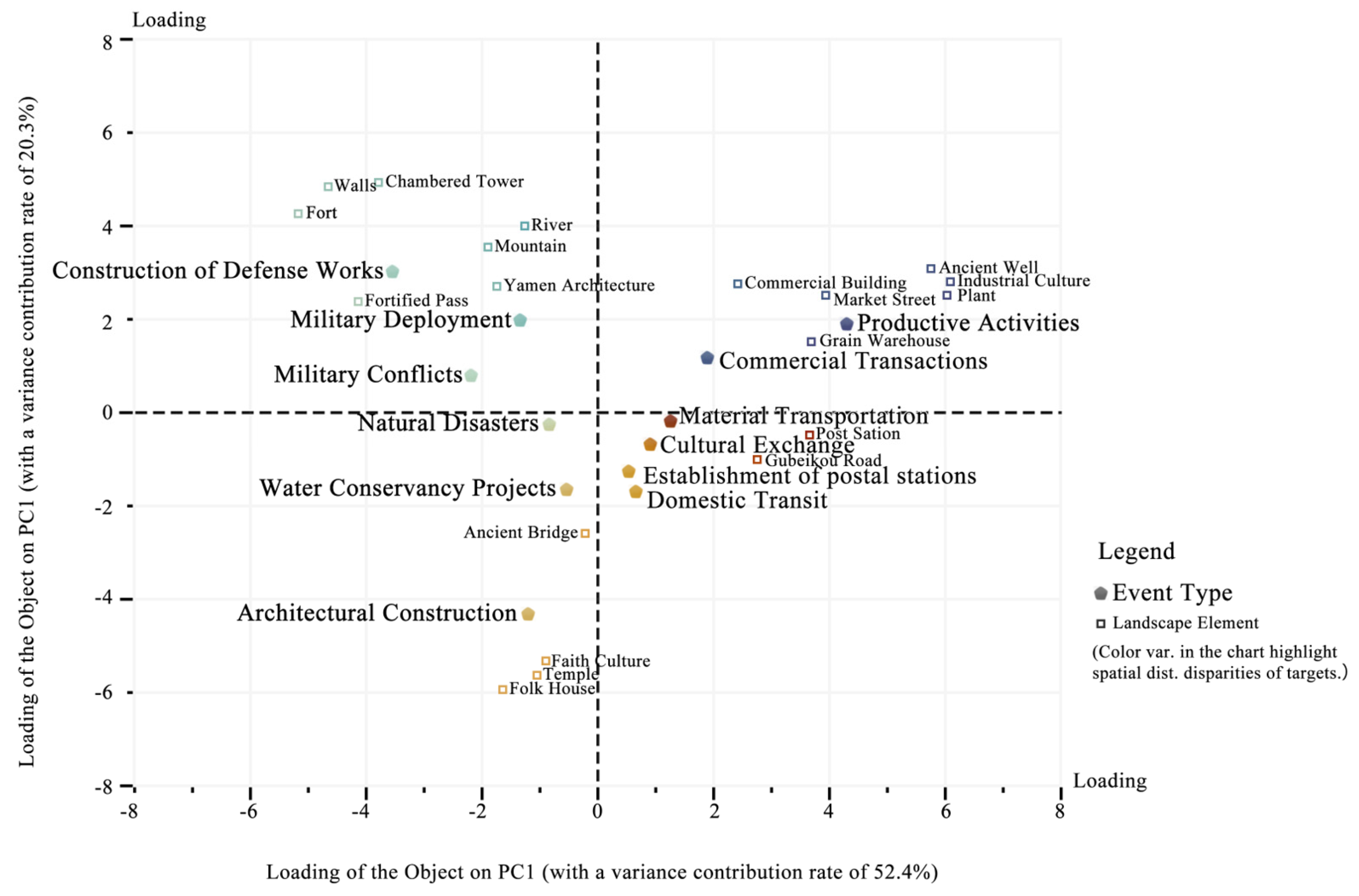

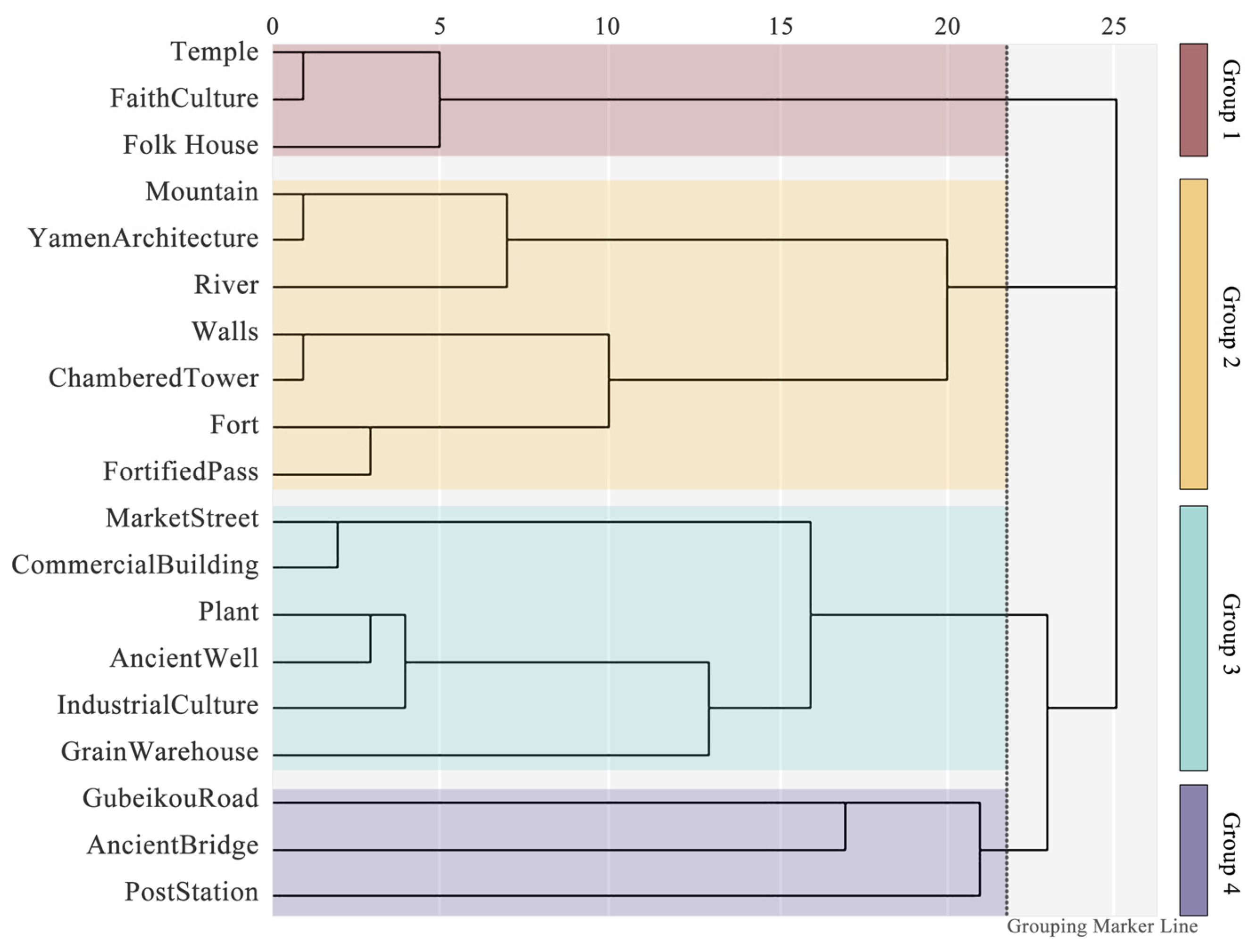

3.2. Clustering Analysis of Event Types and Landscape Elements Based on PCA

- Cluster 1 involves event types such as “Construction of Defense Works”, “Military Deployment”, and “Military Conflicts”, corresponding to landscape elements including “Fort”, “Walls”, “Chambered Tower”, “Yamen Architecture”, “Mountain”, and “River”. It is mainly affected by the role of military and political decisions based on the regional landscape pattern of mountains and rivers in shaping the landscape;

- Cluster 2 includes event types such as “Material Transportation”, “Cultural Exchange”, “Establishment of postal stations”, and “Domestic Transit”, with landscape elements being “Post Station” and “Gubeikou Road”. It is mainly influenced by the regional transportation function;

- Cluster 3 covers event types including “Commercial Transactions” and “Productive Activities”, with landscape elements such as “Commercial Building”, “Ancient Well”, “Market Street”, “Plant”, and “Industrial Culture”. It is mainly affected by industrial development activities;

- Cluster 4 involves event types such as “Natural Disasters”, “Water Conservancy Projects”, and “Construction of ancestral temples”, corresponding to landscape elements including “Ancient Bridge”, “Faith Culture”, “Temple”, and “Residential Houses”. It is mainly influenced by local folk customs and construction activities.

3.3. Analysis of Types of Evolutionary Mechanisms of Landscape Patterns Driven by Historical Events

3.3.1. Type 1: Evolution of the Military Cultural Landscape Pattern Dominated by Military and Political Activities

3.3.2. Type 2: Evolution of Post Road Cultural Landscape Pattern Driven by Transportation Activities

3.3.3. Type 3: Evolution of Economic Cultural Landscape Pattern Influenced by Productive and Trade Activities

3.3.4. Type 4: Evolution of Folk Cultural Landscape Patterns Shaped by Construction Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the Evolutionary Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes in Military Settlements: A Case Study of Gubeikou

| Settlement Name | Settlement Type | Core Driving Factors | Settlement Development Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dongxi Ancient Town [3] | Commerce; Transportation | Salt trade, land-water transportation | The functional orientation shifted from being “military-dominated” in the early stage to “commerce-dominated” later. |

| Juuku/Kizil Suu Valleys [87] | Agropastoralism; Ecological Adaptation | Agropastoral development, ethnic migration | The “agropastoral” function persisted throughout the settlement’s history, and immigration led to multi-ethnic cultural integration. |

| Settlements along the Ancient Tea Horse Road [88] | Trade; Transportation | Commercial trade, post road transportation | The development of the post road network, with “commerce” as its core function, persisted throughout; this network promoted cultural exchanges among different regimes. |

| Jiuguan Village (Shanxi) [89] | Military; Commerce | Military defense, commercial trade | The dominant influencing factors underwent a transformation sequence of “military → commerce → military”. |

| Tibetan Traditional Villages in Western Sichuan [90] | Religion; Ecological Adaptation | Tibetan Buddhism, plateau ecology | Religious culture persisted throughout the settlement’s development, and the plateau climate shaped the settlement’s morphology. |

| Gubeikou | Pure Military Defense | Geostrategy, military policies | The natural strategic pass established the settlement’s military status; military and political factors served as the main drivers, promoting the coordinated development of transportation, commerce, and folk customs. |

4.2. Implications for Heritage Landscape Conservation and Adaptive Reuse Approaches Based on Historical Scenarios and Event Interpretation

4.2.1. Construct a Landscape System Conservation Framework

4.2.2. Conservation Strategy Based on the Integrity of Historical Scenarios

4.2.3. Community-Participatory Heritage Reuse Model Based on Scenario Planning

4.2.4. Digital Display of Heritage Based on Historical Narrative

4.3. Heritage Challenge Response Approaches Based on Landscape Evolution Mechanisms

4.3.1. Implications for Addressing Climate Disaster Threats to Heritage

4.3.2. Guide the Establishment of a Crowdsourced Heritage Management Model in the Gubeikou Region

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.P.; Xiao, J. Analysis on the types and composing of cultural landscapes of China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 25, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P.; Xiao, J.; Cao, K.; Xing, X.L. Exploration of the historical towns’ living protection method through the co-evolution of “landscape-culture”. Chin. Gard. 2015, 31, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Sun, J. A study of historic urban landscape change management based on layered interpretation: A case study of dongxi ancient town. Land 2024, 13, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Research on the changes in cultural landscape of tourist-type traditional Chinese villages from the perspective of cultural memory: Taking Anzhen village in Chongqing as an example. Land 2023, 12, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Jin, Y.P. Linear cultural concept: The practice and structural transformation of urban cultural heritage protection and utilization—Focusing on Beijing’s “three cultural zones”. J. Beijing Union Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 19, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.H.; Li, X.F. The formation and development of settlements along the great wall in the Beijing area. In Proceedings of the Great Wall International Academic Symposium, Beijing, China, 22–24 September 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huizi, Z.; Sicheng, H.; Chengzhi, R.; Yunlu, Z. Construction of the great wall cultural heritage landscape system from the perspective of regional synergy. J. Chin. Urban For. 2020, 18, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Research on the Military Fortresses and Settlements of the Great Wall in Yulin Region. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 1 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.X. “The key to the north of Beijing”—The historical evolution of gubeikou. J. Beijing Union Univ. 1998, 3, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. The roads in the capital of the qing dynasty and the imperial roads for the emperor’s inspection tours. North. Cult. 1991, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.P. The function of the ancient beikou during the liao dynasty. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2016, 18, 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. The ancient beikou during the liao and jin dynasties. J. Liaoning Tech. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2000, 4, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, R. An Historical Geography of Peiping; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (WHC.25/01); UNESCO: Paris, France, 16 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, T.; Brown, S.; Bagnall, K.; Lydon, J.; Sherratt, T.; Veale, S. Engaging the everyday: The concept and practice of ‘everyday heritage’. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 31, 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintér, M.H. When immovable heritage goes ambulatory: The sheep dyke of north ronaldsay (orkney) as an ‘organically evolving monument’. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 31, 1138–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlikoglu, S. Inheritance without the heritage: Fig trees and the ecological effects of imaginative attachments to fetih (conquest). Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 31, 1207–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Qiu, T.; Li, Y. Heritage perspectives on cultural memory and spatial identity in yuan river basin, Hunan, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fei, X.; Luo, L.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J. Social network analysis of heterogeneous subjects driving spatial commercialization of traditional villages: A case study of tanka fishing village in lingshui li autonomous county, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y. Traditional village clustered protection and utilization methods based on network science. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mišić, S.; Obradović, M. Geometry of bastion fortifications magistral line: Influences and development. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. Exploration of the landscape gene characteristics of traditional villages along the jinzhong section of the wanli tea road from the perspective of the village temple system. Land 2024, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiao, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Study on the distribution characteristics and formation mechanism of traditional village names in southeast Guizhou. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shao, L. Interpretation of historic urban landscape genes: A case study of Harbin, China. Land 2024, 13, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Genovese, P.V.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y. Analyzing spatiotemporal features of Suzhou’s old canal city: An optimized composite space syntax model based on multifaceted historical-modern data. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Y. Human-land relationship in the construction of historical settlements based on complex adaptive system (CAS) theory: Evidence from Shawan in Guangfu region, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Li, J. Genotype extraction of traditional dwellings using space syntax: A case study of Tibetan rural houses in Ganzi county, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S. MGWR reveals scale heterogeneity shaping intangible cultural heritage distribution in China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 367. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Yu, C. Interactions between the ming yansui great wall heritage and geographical environment via monte carlo simulation. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, T. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the Qiantang river basin based on historical geographic information. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, D.; Xie, K. Portraying heritage corridor dynamics and cultivating conservation strategies based on environment spatial model: An integration of multi-source data and image semantic segmentation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Tian, Y. Construction and characteristic analysis of landscape gene maps of traditional villages along ancient qin-shu roads, western China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, A.M.W.; Yeh, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hung, C.; Huan, T. Exploring the influence of historical storytelling on cultural heritage tourists’ value co-creation using tour guide interaction and authentic place as mediators. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Hernández, R. Towards other-heritagisation: Negativity in heritage beyond appropriation, maintenance, and transmission. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horský, J.; Ovčáčková, L. Symbolic centres: Cultural transfer in the forcibly abandoned czech borderlands. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristiawan, R.R.; Sushartami, W. Political reconciliation and emancipatory reinterpretations of jakarta’s pancasila sakti monument through heritage tourism: An exploratory study. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, I. It’s not just a game: Playing selected modern board games as a decolonising tool in museums through participatory action research. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Huang, J.; Song, L. Enhancing intangible cultural heritage dissemination through digital experience: An affective events theory approach. Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 438. [Google Scholar]

- Vuoto, A.; Funari, M.F.; Karimzadeh, S.; Lourenço, P.B. Generative modelling of monopteros and tholos temples using existing data: The case study of vesta temple in tivoli. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 71, 334–345. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xu, T.; Gu, X.; Lin, J.; Li, M.; Tao, P.; Dong, X.; Yao, P.; Shao, M. Scene clusters, causes, spatial patterns and strategies in the cultural landscape heritage of tang poetry road in eastern Zhejiang based on text mining. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, L.; Shao, L.; Tang, Y. Using natural language processing to identify and evaluate heritage value for buffer zone delineation in Hengdaohezi town. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cantera, T.; Bonacchi, C. Chatgpt’s interpretation of contested memoryscapes favours the voice of current governments, capitalism and the far-right. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Colace, F.; Gaeta, R.; Lorusso, A.; Pellegrino, M.; Santaniello, D. New ai challenges for cultural heritage protection: A general overview. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 75, 168–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Chen, K.; Qin, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, P.; Zheng, W. Historical geographical information system (HGIS): Social trajectories of two Chinese historical figures Su Shi and Zuo Zongtang in spatial context. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Ceng, R.; Cheng, Y.H. Research on spatial narrative construction of industrial heritage from the perspective of urban renewal—A case study of Tongguanshan 1978 cultural and creative park. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2024, 44, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Hu, Y. Scenery deconstruction: A new approach to understanding the historical characteristics of Nanjing cultural landscape. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; An, X.; Zhang, G.; Liang, S. Spatial patterns, causes and characteristics of the cultural landscape of the road of tang poetry based on text mining: Take the road of tang poetry in eastern Zhejiang as an example. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Yao, S.; Wu, J. A network analytical framework for modeling the global transmission of classics through translation. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragutinovic, A.; Kost, S. (Dis-)continuation of territoriality: A framework for analysis of the role of social practices in (re-)production of space. Land 2025, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Davies, S.N.G.; Leung, N.T.H.; Lau, P.L.K.; Kee, T. Remembering walls by map naming and planned attempts to eradicate and salvage a wall-less “walled city”: Kowloon city. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Song, P.; Tao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, F. Construction of urban collective memory maps based on social media data: A case study of Nanjing, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z. Identifying the authenticity of plantscapes through classics: A case study of Beijing suburbs in the qing dynasty. Land 2024, 13, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, S.; Cui, Y.; Lin, H.; Lv, H.; Ao, J. Academy, private school, confucius institute: Analyzing heritage art of educational architectural paintings via event coding. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, Q.; Shi, W.; Lin, H.; He, J.; Ao, J. Cultural rituality and heritage revitalization values of ancestral temple architecture painting art from the perspective of relational sociology theory. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.K.; Li, Z. Research on the defense system and military settlements of the ming great wall. Archit. J. 2018, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Efficient space and resource planning strategies: Treelike fractal traffic networks of the ming great wall military defence system. Ann. GIS 2018, 24, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y. Spatial structure and corridor construction of intangible cultural heritage: A case study of the ming great wall. Land 2022, 11, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, D.; Gao, C. Identifying landscape character for large linear heritage: A case study of the ming great wall in ji-town, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J. Integrating heritage and environment: Characterization of cultural landscape in Beijing great wall heritage area. Land 2024, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, X. Belt or network? The spatial structure and shaping mechanism of the great wall cultural belt in Beijing. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 2027–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G. Global–local relationships and governance issues at the great wall world heritage site, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of the ming great wall. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y.; He, D.; Zhang, J. Study on the Scale and Morphological Types of Great Wall Castle Settlements in Miyun, Beijing. Des. Community 2021, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.L. Landscape Pattern and Spatial Analysis of Military Settlements Below the Great Wall—Taking the Great Wall at Gubeikou as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 30 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Ma, W.R. Multidisciplinary integration of ming great wall resources and the construction of great wall studies. Res. Great Wall Stud. 2022, 56, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.P.; Zhou, Z.N.; Zheng, Y.Y. The Study on the Historic and Cultural Town of Gubeikou in Miyun County, Beijing. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2014, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lang, Q.; Jin, L.; Qi, H. HUNet: Hierarchical universal network for multi-type ancient Chinese character recognition. Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.; Lee, J.; Machado, J.; Kim, G. Big-data-based text mining and social network analysis of landscape response to future environmental change. Land 2022, 11, 2183. [Google Scholar]

- Huda, I.A.I.S.; Utaya, S.; Bachri, S.; Sumarmi, S.; Sagala, I. Local customary law: The contribution of cuci kampung tradition as counterforce to territorial stigmatization in Jambi, Indonesia. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, D.; Jiang, C.; Wang, D. HsscBERT: Pre-training domain model for the full text of Chinese humanity and social science. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxqda. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Jolliffe, I. Principal component analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1094–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, F.; Contreras, P. Algorithms for hierarchical clustering: An overview. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2012, 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, Q.; Ban, G.; Chen, S.; Ouyang, X.; Fang, X.; Fan, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, Z.; Wei, S.; et al. Twenty-Four Histories; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.S. Historical Records of the Great Wall in the Ming Dynasty Veritable Records; Beijing Yanshan Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.J. The Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonghua Book Company, The Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1985.

- Zong, Q.X. The Chronicles of Miyun County in the Republic of China; The Chronicles of Miyun County in the Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- China Bookstore, Revised Edition of Miyun County Annals in the Guangxu Reign; China Bookstore: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Xiao, J.; Cao, K. Research on historical town preservation methods based on the “narrative grammar” and “accumulation mechanism” of landscapes. Zhong Guo Yuan Lin 2016, 32, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zoran, G. Towards a theory of space in narrative. Poet. Today 1984, 5, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, L.; Chen, M.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Microscale fluvial landscape evolution and its impacts on early human settlement at the shangshan cultural site in the upper Qiantang region, eastern China. Geomorphology 2025, 473, 109630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Research on the cultural landscape features and regional variations of traditional villages and dwellings in multicultural blending areas: A case study of the jiangxi-anhui junction region. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, J.; Liang, C.; Zhong, H. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and causative analysis of toponymic cultural landscapes in traditional villages in northern Guangdong, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bian, J.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, S.; Mu, N.; Xiao, T. Resource supply and demand model of military settlements in the cold weapon era: Case of Zhenbao town, ming great wall. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 318–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Ivanov, S.S.; Tourtellotte, P.A.; Spengler, R.N.; Mir-Makhamad, B.; Kramar, D. Ancient agricultural and pastoral landscapes on the south side of lake issyk-kul: Long-term diachronic analysis of changing patterns of land use, climate change, and ritual use in the juuku and kizil suu valleys. Land 2022, 11, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Shen, C.; Xu, M. Historical insights into sustainable development: Analyzing the spatiotemporal dynamics of ancient trade and settlements. Land 2024, 13, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X. Study on spatial form evolution of traditional villages in jiuguan under the influence of historic transportation network. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Maliki, N.Z.B.; He, C.; Bi, Y.; Yu, S. Cultural gene characterization and mapping of traditional tibetan village landscapes in western Sichuan, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Greenop, K.; Keys, C.; Landorf, C. Digital reconstruction and representation of the sino-korean tribute routes using geographic information systems. Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J. Assessment of sustainable development suitability in linear cultural heritage—A case of Beijing great wall cultural belt. Land 2023, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, S. Value evaluation model (VEM) of ancient Chinese military settlement heritage: A case study of liaoxi corridor in the ming dynasty. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 15–97. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, K.L.; Gough, M.Z.; Cameron, H.M. “Why are we asking for a seat at the table that our ancestors created for us?” the importance of cultural landscapes and power in urban planning. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, J.; Li, P. Decoding the cultural heritage tourism landscape and visitor crowding behavior from the multidimensional embodied perspective: Insights from Chinese classical gardens. Tour. Manag. 2025, 110, 105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Nesting landscape character and personality assessment to intensify rural landscape regionality and uniqueness. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107705. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnet, I.C.; Bryce, R.; Måren, I.E.; Barraclough, A.D.; Malcolm, Z.; Külm, S.; Kokovkin, T.; Taylor, S.; Cudlinova, E.; Sepp, K. Co-creating cultural narratives for sustainable rural development: A transdisciplinary learning framework for guiding place-based social-ecological research. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 73, 101506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Huang, A.; Huang, Z. Virtual tourism attributes in cultural heritage: Benefits and values. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, S.; Jones, T.; Marshall, M.; Wesley, D.; Rangers, N.; Nayinggul, A. Contextualising digital cultural heritage: Bininj GIS and 3D modelling for conservation at ubirr rock art complex, kakadu national park, Australia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R.; Bell, J.; Book, A.; Fear, C.; Hinkin, O.; Hobbs, S.; Matravers, J.; Meggitt, J.; Phillips, N.; Ruhlig, V. Immersive sacred heritage: Enchantment through authenticity at glastonbury abbey. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 31, 857–877. [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf, L.; Napolitano, R. Community agency and heritage recovery in climate-vulnerable historic districts: Lessons from riverine montpelier, vermont. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 31, 683–707. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, M.; Liang, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Law, A. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, A.; Jennings, A. Living on the edge?—Shetland and the HerInDep project: An initial survey. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murin, I.; Hanko, J.; Aláč, J. Lived heritage and local cultures: Depopulation in slovakia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. IJHS 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Formula | Remarks | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score standardization | is the original variable value, is the variable mean, and is the standard deviation. | Standardize the original data to eliminate differences in dimensions. | |

| Covariance matrix of standardized data | is the sample size, is the standardized data, and is the mean vector of standardized data | The covariance matrix of standardized data reflects the correlation between variables | |

| Variance contribution rate | Where is the eigenvalue of the k-th component, and is the total number of original variables | Larger values mean stronger explanatory power of the principal component for original data. |

| Type | Names of Historical Books | Characteristics | Recorded Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| General History in Biographical Style | Records of the Grand Historian (≪史记≫), History of the Southern Dynasties (≪南史≫), History of the Northern Dynasties (≪北史≫) | Spanning multiple dynasties, integrating content through the biographical style (including Basic Annals (本纪), Biographies (列传), Treatises (志), and Tables (表)), breaking the boundaries between dynasties | Cross-dynastic political, economic, and cultural contexts, highlighting the continuity of families and ethnic groups, including the imperial court and all social strata |

| Biographical Dynastic Histories | Book of Han (≪汉书≫), Records of the Three Kingdoms (≪三国志≫), History of the Jin Dynasty (≪晋书≫), History of Song of the Southern Dynasties (≪宋书≫), Book of Southern Qi (≪南齐书≫), Book of Liang (≪梁书≫), Book of Chen (≪陈书≫), History of Wei of the Northern Dynasties (≪魏书≫), Book of Northern Qi (≪北齐书≫), History of Northern Zhou Dynasty (≪周书≫), History of the Sui Dynasty (≪隋书≫), Old History of Tang Dynasty (≪旧唐书≫), New History of Tang Dynasty (≪新唐书≫), Old History of the Five Dynasties (≪旧五代史≫), New History of the Five Dynasties (≪新五代史》), History of Song (≪宋史≫), History of the Liao Dynasty (≪辽史≫), History of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty (≪金史≫), History of the Yuan Dynasty (≪元史≫), History of the Ming Dynasty (≪明史≫) | Focusing on a single dynasty, concentrating on recording historical events of the dynasty itself in biographical style, and strengthening the integrity of “the history of one dynasty” | Political and military affairs of the dynasty; institutional systems; deeds of important figures |

| Annals-Style Veritable Records | Veritable Records of the Ming Dynasty (≪明实录≫), Veritable Records of the Qing Dynasty (≪清实录≫) | Centered on the emperor, recorded chronologically by “year, month, day”, reflecting the official imperial power narrative | Emperor’s words and deeds, central government decisions; national ceremonies, wars, personnel appointments and removals; avoiding records of ruling crises and details of civil society |

| Local Chronicles | Miyun Gazetteer (≪密云县志≫) | Covering a specific region, focusing on grassroots affairs, highlighting local practical value | Local geography, administration, economy, culture, historic sites, etc. |

| Inscriptions on Steles | - | Detailed records of single events in the region | Mainly recording the construction of temples and military facilities, and the commendation of meritorious persons |

| Event Type | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Construction of Defense Works | Records events of resisting foreign enemies and consolidating defense, involving building or repairing forts, passes, and fortresses to construct or maintain defense facilities. |

| Military Deployment | Records military deployment events, including garrisoning, training, expeditions, and officer appointments/removals, with two patterns: deploying troops to Gubeikou and dispatching troops from Gubeikou. |

| Military Conflicts | Records territory contests and resistance against invasions, involving battles, sieges, and surprise attacks, possibly accompanied by regime changes, territorial shifts, population migration, or resource transfers. |

| Material Transportation | Records events of ensuring military supplies and allocating resources, involving canal/land transportation and transfer stations, acting on grain, armaments, and warehouses to meet material needs. |

| Cultural Exchange | Records events of reaching other regimes’ territories, including diplomatic visits, religious spread, and journey observations/anecdotes. |

| Domestic Transit | Records internal transportation events to reach destinations, possibly with road construction, river dredging, or transfer point setup. |

| Post Station Establishment | Records establishment or abolition of post stations as needed, aimed at document delivery and postal transportation. |

| Productive Activities | Records events of obtaining materials and sustaining livelihoods, involving farming, animal husbandry, and handicrafts, acting on land, crops, and livestock for material multiplication. |

| Commercial Transactions | Records commodity exchange and financial supplementation events, involving transactions, trafficking, and mutual trade to realize regional circulation or government subsidies. |

| Natural Disasters | Records historical disasters (mainly floods, droughts) causing casualties, crop failures, building collapses, or social unrest. |

| Water Conservancy Projects | Records events of digging wells, building bridges, constructing dikes/canals, aimed at flood control, disaster reduction, and farmland irrigation. |

| Architectural Construction | Records construction, expansion, or renovation of ancestral temples, buildings, and official residences, aimed at strengthening feudal ethics, expressing beliefs, or meeting military/civilian needs. |

| Types of Landscape Elements | Specific Landscape Names in Gubeikou | Explanations of Landscape Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Yamen Architecture | Customs House (Ancient Site), Miyun Houwei Yashu, Yanwu Hall, Canjiang Yamen, Tidu Yashu, Xunjian Yamen, Tongzhi Yashu | Yamen buildings refer to the buildings of ancient official administrative institutions, and also serve as places for officials to live and work. |

| Temple | Erlang Temple, Confucius Temple (Ancient Site), Yanglinggong Temple, Yuhuang Temple, Lvzu Temple, Thousand-Layer Tower (Ancient Site), Mosque, Wenshen Temple, Niangniang Temple, Nantianmen (Ancient Site), Guandi Temple, Dragon King Temple, Medicine King Temple, Guanyin Pavilion | Places for offering sacrifices to and worshipping gods, Buddhas, ancient sages, or objects of religious belief. |

| Post Station | Gubeikou Courier Station (Qing Dynasty), Gubeikou Pavilion (Liao Dynasty) (Ancient Site) | Ancient institutions and auxiliary buildings for couriers delivering official documents, traveling officials, as well as merchants and travelers to lodge and change horses on the way. |

| Commercial Building | Yixinchang Cloth Store, Juyuahao Variety Store, Gubeikou Sericulture and Weaving Bureau | Buildings serving as places for production and commercial activities, such as shops, commercial firms, workshops, factories, etc. |

| Folk House | Meng Family Compound, Duan Family Compound, Zhu Yonghai’s Folk House, Daokou Compound, Bai Family Compound, Hao Family Compound, Houzhuang Village Primary School, Zhou Shufen’s Folk House | Residential buildings refer to dwellings for common people. |

| Ancient Well | Three-Eyed Well | Time-honored wells are an important source of domestic water for ancient residents. |

| Ancient Bridge | Gubeikou Stone Bridge | Ancient bridges, mostly built to cross natural or man-made obstacles such as rivers, canyons, and depressions, have both transportation functions and architectural artistic value. |

| Grain Warehouse | Gubeikou Granary (Ancient Site) | Warehouses for storing grain. |

| Walls | The Great Wall of the Northern Qi Dynasty, Great Wall of the Ming Dynasty | Man-made Great Wall walls. |

| Fort | Chaoheguan Fortress, Beikou Fortress (Ancient Site), Simatai Fortress, Gubeikou Fortress, Shangying Fortress, Shalinggou Fort, Zhuanduozi Fort, Hexi Fort, Gubeikou Barbican, Shipogu Fort, Liulin Camp, Five Battalions of the Trained Army | Enclosed wall facilities mainly for defense and garrison, some of which also serve as places for military and civilian production, living, and administrative activities. They are distributed on flat land or connected to the Great Wall walls. |

| Fortified Pass | Huangyugou Pass, Gezidong Pass, Gubeikou Pass, Shipogu Pass, Wuliduo Pass, Longwangyu Pass, Taochun Pass, Zhuanduozi Pass, Shaling Pass, Yajishan Pass, Simatai Pass, Hongmengou Pass, Yinziyu Pass, Tanghekou Pass, Huai’gucheng Pass | Passes refer to passable defense facilities set at natural mountain passes, some of which are connected to walls and mainly distributed in valleys and river valleys. |

| Chambered Tower | Miyun Towers No. 257–384, No. 1–3 Defence Towers of the Northern Qi Dynasty in Chaoguan Village | Defensive beacon towers built on the Great Wall walls, which can be used for watching, garrisoning, or beacon communication. |

| Market Street | Gubeikou Market Street | Streets with commercial transactions as their core function, gathering various shops and stalls, serving as places for daily folk trade and communication. |

| Gubeikou Road | Gubeikou Road (Pre-Yuan Dynasty), Gubeikou Road (Ming and Qing Dynasty) | Ancient post roads verified by historical research. |

| River | Chao River, Xiaotang River | Naturally formed surface water channels are an important part of natural landscapes. |

| Mountain | Wohu Mountain, Panlong Mountain, Fufeng Mountain, Yaji Mountain, Huanghua Mountain | Naturally formed highland terrain, which can form a reliable defense line when combined with military defense facilities. |

| Plant (Ancient Tree) | Agricultural Landscape, Ancient Trees (Grade I and II) | Plants dominated by crops, farmland landscapes, and existing ancient trees are all regarded as such landscape elements. |

| Industrial Culture | Agriculture, Handicraft Industry, Animal Husbandry, Mining Industry, Industry | Mainly referring to several industrial types that once appeared in the Gubeikou area, reflecting the development of production methods. |

| Faith Culture | Taoism, Islam, Confucianism, Buddhism, Folk hero belief | Culture related to religion and folk beliefs, including local belief concepts, folk stories, etc. |

| Major Periods | Involved Dynasties and Years | Period Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Military Embryonic Period | Zhou to Sui Dynasties (1046 BCE–618 CE) | Military and cultural collisions between regimes formed the cultural keynote of this stage, with the Northern Qi Dynasty constructing the earliest military landscapes. |

| Functional Expansion Period | Tang to Yuan Dynasties (714–1368 CE) | The Tang Dynasty established shouzhuo (military garrisons) to balance border defense and production management. The Treaty of Chanyuan strengthened cross-regime exchanges, while incessant military conflicts among the Song, Liao, Jin, and Yuan regimes continued the military cultural thread. This period saw multifaceted development marked by agricultural germination, economic and cultural prosperity, and foreshadowing ethnic integration in border regions. |

| Systemic Maturity Period | Ming Dynasty (1368–1602 CE) | During this period, the military function of Gubeikou continued to strengthen. The Ming Dynasty perfected its defense system, with postal routes and ritual architectures all serving military purposes, forming a highly systematized landscape pattern of “controlling the border through a military network.” |

| Multiethnic Integration Period | Late Ming to Qing Dynasty (1602–1911 CE) | During this period, Gubeikou witnessed intensified ethnic integration and the rise of border trade. In the late Ming Dynasty, Nurhaci unified northern tribes and established the Later Jin regime, triggering continuous instability along the Ming frontier. In the Qing Dynasty, the opening of the Imperial Road and the establishment of the Tidu Office (Regional Military Command) drove functional transformation, creating a thriving landscape of military, economic, and cultural activities and positioning Gubeikou as a comprehensive borderland hub. |

| Major Periods | Correlation Clustering of Event Types and Landscape Elements | Core Driving Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Military Embryonic Period |

|

|

| Functional Expansion Period |

|

|

| Systemic Maturity Period |

|

|

| Multiethnic Integration Period |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, D.; Dong, H.; Li, S.; Fang, M. Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes Based on the Analysis of Historical Events—A Case Study of Gubeikou, Beijing. Buildings 2025, 15, 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193495

He D, Dong H, Li S, Fang M. Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes Based on the Analysis of Historical Events—A Case Study of Gubeikou, Beijing. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193495

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Ding, Hanghui Dong, Shihao Li, and Minmin Fang. 2025. "Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes Based on the Analysis of Historical Events—A Case Study of Gubeikou, Beijing" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193495

APA StyleHe, D., Dong, H., Li, S., & Fang, M. (2025). Study on the Evolution Mechanism of Cultural Landscapes Based on the Analysis of Historical Events—A Case Study of Gubeikou, Beijing. Buildings, 15(19), 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193495