Framing Participatory Regeneration in Communal Space Governance: A Case Study of Work-Unit Compound Neighborhoods in Shanghai, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

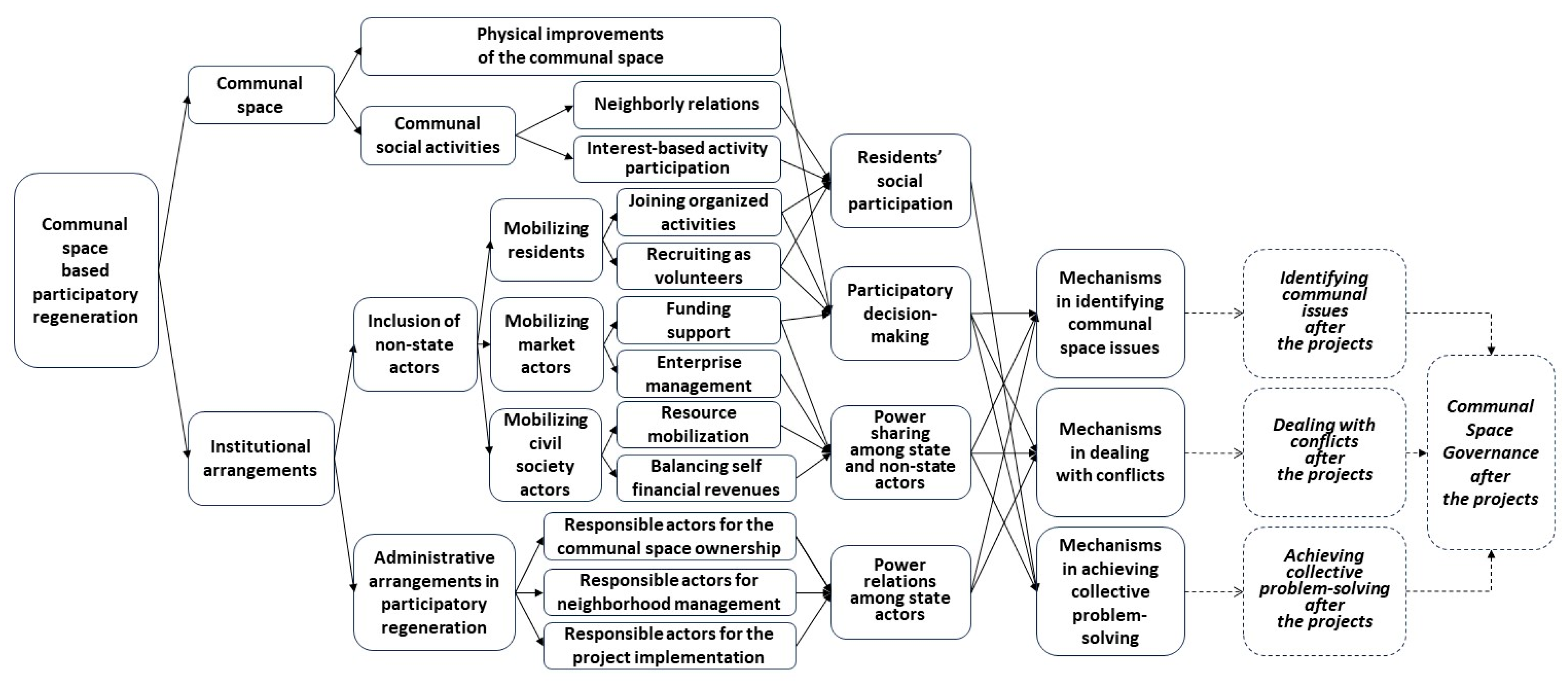

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Case A: Regenerating the Poorly Managed Greening into a Vivifying Community Garden

3.1.1. Mechanisms in Identifying Communal Space Issues: Participatory Workshops

3.1.2. Mechanisms in Dealing with Conflicts: Leadership

3.1.3. Mechanisms in Achieving Collective Solutions: Participatory Interest-Based Activities and External Social Networking

3.2. Case B: Regenerating a Vacant Underground Air-Raid Shelter into a Community Center

3.2.1. Mechanisms in Identifying Local Needs: Interviews, Questionnaires, Participatory Workshops, Co-Governance Committee Meetings

3.2.2. Mechanisms in Dealing with Conflicts: Consultant Meetings and Co-Governance Committee

3.2.3. Mechanisms in Achieving Collective Solutions: Socio-Economic Approaches and External Social Networking (the Establishment of XXL Cooperative Association)

4. Discussion

4.1. Nuanced Path Dependence of Relying on State Actors in Communal Space Governance

4.2. Enhancing Effectiveness of Communal Space Governance via Adopting Digital Participation Technologies and Building Supportive Networks

4.3. Cultivating a New Political Acceptance of Autonomously Organized Communal Space Governance Based on Socio-Economic Participatory Means

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions for Stakeholders

- (1)

- What kinds of participatory strategies have been adopted in this project, what kinds of participatory activities have you been involved in and how?

- (2)

- Did you participate in the identification of communal space issues during and after the regeneration projects, and how?

- (3)

- Did you participate in dealing with conflicts during and after the regeneration projects, and how?

- (4)

- Did you participate in achieving collective problem-solving during and after the regeneration projects, and how?

- (5)

- What are differences in communal space governance during and after the regeneration project, and why?

References

- Brade, I.; Herfert, G.; Wiest, K. Recent trends and future prospects of socio-spatial differentiation in urban regions of Central and Eastern Europe: A lull before the storm? Cities 2009, 26, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawoy, M. The end of sovietoloy and the renaissance of modernization theory. Contemp. Sociol. 1992, 21, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Changes in the structure of public housing provision in urban China. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, M.K.; Parish, W.L. Urban Life in Contemporary China; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Murie, A. Commercial housing development in urban China. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 1475–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pow, C.P. Neoliberalism and the aestheticization of new middle-class landscapes. Antipode 2009, 41, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, E.M. The danwei: Socio-spatial characteristics of work units in China’s urban society. Econ. Geogr. 1986, 62, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Wu, F. Socio-spatial impacts of property-led redevelopment on China’s urban neighborhoods. Cities 2007, 24, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. Urban land reform in China. Land Use Policy 1997, 14, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P. Housing reform and its impacts on the urban poor in China. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Rediscovering the ‘Gate’ under market transition: From work-unit compounds to commodity housing enclaves. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Lin, Z. From traditional and socialist work-unit communities to commercial housing: The association between neighborhood types and adult health in urban China. Chin. Socio. Rev. 2021, 53, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Breitung, W.; Li, S. The changing meaning of neighborhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estate: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, T. Enhancing neighborly relations through participatory regeneration: A case study of Shanghai. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 05023024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelzet, A.; Wissink, B. Neighborhoods, social networks, and trust in post-reform China: The case of Guangzhou. Urban Geogr. 2012, 33, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Lin, N. The weaknesses of civic territorial organizations: Civic engagement and homeowners associations in urban China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 38, 2309–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, F. Property-led redevelopment in post-reform China: A case study of Xintiandi redevelopment project in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. Three waves of state-led gentrification in China. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2018, 110, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Fu, Q. Deciphering the civic virtue of communal space: Neighborhood attachment, social capital, and neighborhood participation in urban China. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D.; Chen, H.; Ye, C. Progress of China’s new-type urbanization construction since 2014: A preliminary assessment. Cities 2018, 78, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, J. A regional categorization for “New-Type Urbanization” in China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, D. Challenges and the way forward in China’s new-type urbanization. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, B.; Barach, R. Collaborative governance for urban sustainability: Implementing solar cities. Asia Pac. J. Public Adm. 2021, 43, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, J.M. A Framework for assessing power in collaborative governance processes. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Nasi, G.; Rivenbark, W.C. Implementing collaborative governance: Models, experiences, and challenges. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. What is governance? Governance 2013, 26, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Recio, R.B. Engaging the ‘ungovernable’: Urban informality issues and insights for planning. J. Urban Reg. Plan. 2015, 2, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel, S.; Buchecker, M.; Schulz, T. Forming social capital: Does participatory planning foster trust in institutions? J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 131, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ran, B.; Li, Y. Street-level collaborative governance for urban regeneration: How were conflicts resolved at grassroot level? J. Urban Aff. 2022, 46, 1723–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, E.C.-M.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmark, A. The functional differentiation of governance: Public governance beyond hierarchy, market and networks. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, R. Formulating the success of citizen participation in urban regeneration: Insights and perplexities from Lisbon. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Cai, Q.; Huang, Y.; Lang, W. System building and multistakeholder involvement in public participatory community planning through both collaborative and micro-regeneration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Qian, Y. Collaborative governance for participatory regeneration practices in old residential communities within the Chinese context: Cases from Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Achieving Neighborhood-Level Collaborative Governance through Participatory Regeneration: Cases of Three Residential Heritage Neighborhoods in Shanghai. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hui, C.M.; Chen, T.T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y.L. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the ‘three old renewals’ in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M.; Imrie, R. Governmentality and rights and responsibilities in urban policy. Environ. Plan. A 2000, 32, 2187–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B. Collaborating: Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problem; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström, E.; Ekman, A.-K.; Lindholm, K.-J. Commoning in the periphery—The role of the commons for understanding rural continuities and change. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosol, M. Public participation in post-fordist urban green space governance: The case of community gardens in Berlin. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, G.; Konijnendijk, C.C. Communication between science, policy and citizens in public participation in urban forestry—Experiences from the Neighbourwoods project. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E. Actually existing commons: Three moments of space of community gardens in New York City. Antipode 2012, 44, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, M.H. Reaching a consensus. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1974, 69, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.; Dzur, A. Citizens’ governance spaces: Democratic action through disruptive collective problem-solving. Political Stud. 2021, 70, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; He, S.; Webster, C. Path dependency and the neighborhood effect: Urban poverty in impoverished neighborhoods in Chinese cities. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Falanga, R.; Nunes, M. Tackling urban disparities through participatory culture-led urban regeneration: Insights from Lisbon. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baist, T.N. Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educ. Res. 2003, 45, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Babaei, E. A Critical Review of Grounded Theory Research in Urban Planning and Design. Plan. Pract. Res. 2020, 36, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist method. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison AJohn, L.; Breckon, J. Grounded theory based research within exercise psychology: A critical review. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2011, 8, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Toward community engagement: Can the built environment help? Grassroots participation and communal space in Chinese urban communities. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; He, S. Reshuffling informal governance configurations: Active agency and collective actions in three regenerated neighborhoods in China. Habitat Int. 2025, 156, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, D. Space, politics and Labour: Towards a spatial genealogy of the Chinese work-unit. Asian Stud. Rev. 1997, 20, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, A.; Zhu, J. Boundaries and Belonging in Guangzhou: Changing the Nature of Residential Space in Urban China. In The Politics of Civic Space in Asia; Daniere, A., Douglass, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kashwan, P. Inequality, democracy, and the environment: A cross-national analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, Q.; Ao, J.; Lin, H.; Ji, S.; Yang, M.; Sun, J. Systematic review: A scientometric analysis of the status, trends and challenges in the application of digital technology to cultural heritage conservation (2019–2024). Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, P.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, J.; Schnabel, M.A. Leveraging augmented reality for historic streetscape regeneration decision-making: A big and small data approach with social media and stakeholder participation integration. Cities 2025, 166, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F. Unraveling the renewal priority of urban heritage communities via macro-micro dimensional assessment—A case study of Nanjing City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 124, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, M.; Chan, E.H.W.; Wong, M.S.; Irekponor, V.E.; AbdulRahman, M.O. A framework to simplify pre-processing location-based social media big data for sustainable urban planning and management. Cities 2021, 109, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, K.D.; Joshi, J. Geographical information system (GIS) as a planning support system (PSS) in urban planning: Theoretical review and its practice in urban renewal process in Hong Kong. J. Eng. Technol. Plan. 2022, 3, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ren, K.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Zhou, P. Toward effective urban regeneration post-COVID-19: Urban vitality assessment to evaluate people preferences and place settings integrating LBSNs and POI. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y. Cultivating an alternative subjectivity beyond neoliberalism: Community gardens in urban China. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2023, 113, 1348–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, B.; Qi, H. Contingencies of power sharing in collaborative governance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnihan, P.; Byrne, M. Escape into the city: Everyday practices of commoning and the production of urban space in Dublin. Antipode 2015, 47, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, H.M. The significance and meanings of public space improvement in low-income neighborhoods ‘colonias populares’ in Xalapa-Mexico. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, P.; Yan, J.; Wang, H. Systematic Review of Socially Sustainable and Community Regeneration: Research Traits, Focal Points, and Future Trajectories. Buildings 2024, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. Uncommon ground: The “poverty of history” in common property discourse. Dev. Change 2004, 35, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R. Collective action and the urban commons. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2011, 87, 57. [Google Scholar]

| Types | Number | Interviewees |

|---|---|---|

| Local Officials (8 people) | No. 1 | Staff member from the Street Office |

| No. 2 | Staff member from the Self-Governance Office of Street Office | |

| No. 3 | Staff member from the Business Operation Office of Street Office | |

| Nos. 4–5 | Staff members from the Planning and Natural Resource Bureau | |

| No. 6 | Staff from Public Space Promotion Center, affiliated with the Planning & Natural Resource Bureau | |

| No. 7 | Staff member from the Housing Management Bureau | |

| No. 8 | Staff member from the Civil Air Defense Office of Street Office | |

| Planners (2 people) | No. 9 | The community planner in Case A |

| No. 10 | The community planner in Case B | |

| Operators (4 people) | Nos. 11–12 | Responsible operators in Case A |

| Nos. 13–14 | Responsible operators in Case B | |

| Community groups leaders (6 people) | Nos. 15–16 | Leaders of Residents’ Committees in two case studies |

| Nos. 17–18 | Staff from Property Management Companies in two case studies | |

| Nos. 19–20 | Members of community interest groups | |

| Residents (42) | Nos. 21–42 | Residents from Case A neighborhood |

| Nos. 43–62 | Residents from Case B neighborhood | |

| Professionals (11 people) | Nos. 63–68 | Professors focusing on participatory planning |

| Nos. 69–70 | Professors focusing on social governance | |

| Nos. 71–73 | Professors focusing on neighborhoods regeneration | |

| Experts (3 people) | Nos. 74–76 | Practitioners engaged in participatory regeneration projects |

| First-Order Categories | Participatory Strategies | Physical Improvements | Resident Social Participation | Institutional Arrangements | Stakeholders Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second- order categories in Case A | Planning (mobilizing meetings, guided community tour, consultant meetings) Designing (co-designing, normalizing) Construction (land treatment, planting, and building facilities) Management (CNSNGO organized activities, local group organized activities, pupil joined activities) | Spatial arrangements (spatial layouts) Functional re-organizations (original functions, implanted new functions) Boundaries (entrance and enclosure) | State agencies intervened participation (nomination, activities organization and retired cadre recruitment) NGO organized participation (training, educational, parent–child interaction) | Formal arrangements (agreement, contract) Informal arrangements (reputation, resource mobilization capacities, public praise, media exposure, propaganda, non-monetary incentives) | Administrative Relations (superior and subordinate, same levels of different departments) Financial Relations (funding provision, sharing and flows) Like-Minded Social Relations (supportive forwarding, participation) |

| Second- order categories in Case B | Planning (identifying local needs, identifying local talents, recruiting partners) Decorating (wall painting, ornamental hand-making, second-hand furniture donating) Management (bulletin board wall stickers and consultant meetings with partners) | Spatial arrangements (spatial separations and layouts) Functional re-organizations (original functions, implanted social service functions and commercial functions) Boundaries (entrance and enclosure) | State agencies intervened participation (nomination) BFCD organized participation (identifying local needs, encouraging community engagement) Spontaneous participation (volunteering in service provision and becoming managers) | Formal arrangements (agreement, contract) Informal arrangements (collaboration, public praise, media exposure, propaganda, both non-monetary and commercial incentives) | Administrative Relations (superior and subordinate, same levels of different departments) Financial Relations (funding provision, sharing and flows, profit-making services) Like-Minded Social Relations (supportive forwarding, participation, cooperation) |

| Aspects of Communal Space Governance | Case A | Case B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the Project | After the Project | During the Project | After the Project | |

| Mechanisms in reaching consensus in identifying issues |

|

|

|

|

| Mechanisms in dealing with conflicts |

|

|

|

|

| Mechanisms in achieving collective solutions |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xia, B. Framing Participatory Regeneration in Communal Space Governance: A Case Study of Work-Unit Compound Neighborhoods in Shanghai, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 3384. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183384

Xu Y, Wang H, Xia B. Framing Participatory Regeneration in Communal Space Governance: A Case Study of Work-Unit Compound Neighborhoods in Shanghai, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(18):3384. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183384

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yueli, Han Wang, and Bing Xia. 2025. "Framing Participatory Regeneration in Communal Space Governance: A Case Study of Work-Unit Compound Neighborhoods in Shanghai, China" Buildings 15, no. 18: 3384. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183384

APA StyleXu, Y., Wang, H., & Xia, B. (2025). Framing Participatory Regeneration in Communal Space Governance: A Case Study of Work-Unit Compound Neighborhoods in Shanghai, China. Buildings, 15(18), 3384. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15183384